Abstract

The utilisation of carbon fibre–reinforced polymers (CFRPs) has emerged as a promising method for enhancing the flexural performance of reinforced-concrete (RC) bridges. While extensive research has been conducted on CFRP systems implemented on flat soffit RC beams, further work is required to assess their effectiveness when applied to concavely curved soffit RC members. This paper uses finite element simulations to extend an experimental database on RC beams with curved soffits ranging from 5, 10, 15 and 20 mm/m strengthened using externally bonded FRP. Parametric studies into four different concrete strengths ranging from 25, 35, 48, 57 MPa and additional degrees of soffit curvature up to 50 mm/m were used to generate a total of 88 data points. Further, gene expression programming (GEP) was used to develop an empirical model correlating a capacity reduction factor applied to the maximum FRP strain required to produce intermediate-span crack-induced (IC) debonding for concavely curved soffit RC beams externally strengthened with CFRP. The results of the GEP model demonstrated that the model can be employed as an efficient tool for the prediction of the reduction in the flexural capacity of concavely curved soffit RC beams strengthened externally with NSM CFRP.

1. Introduction

The application of advanced composite materials, particularly fibre-reinforced polymers (FRP), for the strengthening of existing bridge structures has become increasingly widespread in response to escalating load demands and progressive structural deterioration. Over recent decades, FRP-based strengthening systems have gained significant interest among structural engineers due to their high strength-to-weight ratio, ease of installation, resistance to corrosion, and low maintenance requirements. While extensive research has been conducted on the failure mechanisms of flat-soffit reinforced concrete (RC) girders strengthened with FRP, comparatively limited attention has been devoted to curved-soffit RC members, despite their common use in bridge construction [1,2]. Documented cases of curved soffit bridges include the Swan Street Bridge (Melbourne, Australia), the West Seattle Bridge (Washington, USA), the Clearwater Memorial Bridge (Florida, USA), and the Ponte di Albiano Magra Bridge (Tuscany, Italy), all of which incorporate variable-depth or curved soffit girder configurations that give rise to concave soffit geometries. The curvature of the soffit introduces transverse tensile stresses at the concrete–adhesive interface, which can exceed the tensile capacity of the concrete substrate. When this occurs, premature debonding of the externally bonded CFRP initiates at flexural or flexural–shear crack locations. The debonding subsequently propagates toward the CFRP terminations, resulting in complete delamination at strain levels significantly below the rupture strain of the CFRP, thereby limiting the effective utilisation of the strengthening system.

It is important to note that the available studies regarding the strengthening of curved-soffit-reinforced concrete girders with FRP are severely limited [3,4,5]. As discussed by Al-Ghrery et al. [6,7], design guidelines such as ACI440.2R [8] drew upon the fundamental findings of the study conducted by Aiello et al. [5] to propose a concavity limit of 5 mm per metre when using externally bonded CFRP. However, the specimens tested by Aiello et al. [5] consisted solely of concrete without the inclusion of internal steel reinforcement. Moreover, these specimens were half-beams, and the attachment of FRP composites was limited to only a portion of the curvature’s chord. Further, the absence of load–displacement measurements in the results hindered a comprehensive understanding of the behaviour of curved soffit beams. Results obtained from plain concrete half-beams are fundamentally unsuitable for predicting the behaviour of reinforced concrete (RC) beams strengthened with CFRP because the governing load transfer mechanisms, cracking behaviour, and debonding triggers differ substantially once internal steel reinforcement is present. In plain concrete specimens, cracking localises rapidly and leads directly to brittle tensile failure, with no post-cracking stress redistribution or tension stiffening. Consequently, CFRP debonding in such specimens is governed primarily by the tensile capacity of the concrete substrate rather than by crack-induced stress concentrations. In contrast, RC beams exhibit multiple flexural cracking, tension stiffening, and significant stress redistribution between concrete, steel reinforcement, and CFRP after cracking. The presence of longitudinal steel reinforcement fundamentally alters crack spacing, crack-width evolution, and interfacial stress gradients along the CFRP. These mechanisms are critical in governing intermediate-span crack-induced (IC) debonding, which is the dominant failure mode in flexurally strengthened RC beams. Plain concrete half-beams are therefore unable to reproduce the crack-controlled bond–slip behaviour, CFRP strain development, or failure propagation observed in reinforced members.

More recently, Al-Ghrery et al. [9] conducted an extensive experimental programme into the behaviour of flexurally strengthened RC beams with different levels of soffit curvature ranging from 5, 10, 15 and 20 mm/m. The study tested 24 beams in three-point bending, each of which spanned 2.3 m, had a midspan depth of 260 mm and were 140 mm wide. All beams possessed an average concrete compressive strength of 56.5 MPa at the time of testing and were strengthened using two configurations: (1) one 50 mm wide × 1.4 mm thick CFRP laminate with a modulus of elasticity of 165 GPa and (2) a single 50 mm wide × 0.337 mm thick wet lay-up CFRP sheet with a modulus of elasticity of 240 GPa. Beams featuring curvatures of 5, 10, 15, and 20 mm/m, reinforced with CFRP sheets, exhibited a decrease in load-carrying capacity compared to flat soffit beams strengthened with a similar CFRP system. The reductions were 2%, 5%, 6%, and 12%, respectively. In contrast, when these beams were reinforced with CFRP laminate, the reductions in load-carrying capacity compared to flat soffit beams were recorded as (+4%), (−8%), (−4%), and (−15%), respectively. However, these results were based on a single concrete strength, and further studies are required to determine the reductions in strength and CFRP strain utilisation which would be expected for beams of different concrete strengths which also possess concave curvatures greater than 5 mm/m. More recent research by Saud et al. [10] investigated the flexural behaviour of lightweight reinforced concrete beams with concavely curved soffits strengthened with externally bonded CFRP, expanding the experimental database on curved-soffit strengthening to include lightweight concrete systems. While this study provides valuable insights into load–displacement response and ultimate capacity for such members, it did not report CFRP strain levels prior to debonding, limiting its use for validating predictive strain-based models.

Numerical analysis techniques, particularly the finite element method (FEM), are well-established tools for investigating the structural behaviour of real engineering systems. A substantial body of FEM-based research has been carried out to model different Fibre-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) de-bonding mechanisms, as demonstrated in the studies by [11,12,13,14,15]. Such numerical simulations provide a predictive framework for structural failure, extend the applicability of experimental datasets, and offer valuable insight into critical behavioural mechanisms in cases where experimental evidence is limited or unavailable, as noted by Abouelleil and Rasheed [16]. Investigations by Godat et al. [17] and Teng et al. [18] have shown that finite element modelling can accurately capture the full structural response of FRP-strengthened reinforced concrete (RC) members. Within these simulation environments, concrete elements are capable of representing both tensile cracking and compressive crushing, while reinforcing steel bars are typically modelled with elasto-plastic constitutive behaviour. The numerical outcomes reported in the literature show strong agreement with corresponding experimental observations, including load–displacement relationships, the responses of steel and FRP reinforcements, and crack development patterns [19]. In addition, the stiffness characteristics adopted in the numerical simulations are consistent with average stiffness values measured experimentally. The simulated failure modes generally reproduce those observed in physical tests, and such numerical approaches continue to be employed in ongoing research to extend experimental databases.

In the current investigation, a two-dimensional nonlinear finite element (FE) modelling framework was developed using ATENA 2D to simulate simply supported reinforced concrete beams with curved soffits that were externally strengthened using either CFRP laminates or CFRP sheets. The geometric configurations and material properties of the simulated beams were adopted from the experimental programme reported by Al-Ghrery et al. [9]. The numerical analyses were performed to determine the first cracking load, pre- and post-cracking stiffness, load–mid-span deflection response, ultimate (failure) load, governing failure mode, and crack pattern, with the aim of evaluating the influence of soffit concavity on the structural performance and load-carrying capacity of this class of members. The results obtained from the FE simulations, together with data from previously reported experimental studies, were subsequently used to develop an empirical model for predicting the intermediate-span crack-induced failure load of curved soffit RC beams strengthened externally with CFRP in flexure. Gene expression programming (GEP) was adopted as the modelling framework to derive this empirical predictive equation.

Strengthening of concavely curved soffits in flexure using FRP generate curvature-induced peeling stresses that lead to premature debonding at CFRP strain levels well below those assumed in existing design models. This altered stress state fundamentally changes CFRP strain utilisation, failure initiation, and capacity prediction. Al-Ghrery et al. [9] experimentally demonstrated that concave soffit curvature causes premature intermediate-span crack-induced (IC) debonding in CFRP-strengthened RC beams compared to flat soffits; however, the study was limited to a single concrete strength and soffit curvatures up to 20 mm/m, and did not provide a predictive framework for quantifying the associated reduction in CFRP strain capacity. The present study addresses these limitations by (i) explicitly isolating and quantifying curvature-induced effects on FRP-to-concrete IC debonding strain using validated nonlinear FE simulations, (ii) extending the experimental data to a wide range of soffit curvatures (up to 50 mm/m) and concrete strengths (25–57 MPa), and (iii) proposing, for the first time, an empirical reduction factor for CFRP strain capacity that explicitly accounts for soffit curvature as an independent design parameter.

2. Research Significance

This research is significant because it addresses a critical gap in the understanding of how concavely curved soffit reinforced-concrete (RC) beams behave when strengthened with carbon-fibre-reinforced polymers (CFRP). Unlike flat soffit beams whose strengthening mechanisms have been extensively studied, the performance and failure modes of curved soffit beams remain underexplored despite their common use in bridge structures. By integrating extensive finite element simulations with a comprehensive experimental database, the study investigates a wide range of parameters, including various degrees of curvature (from 5 mm/m up to 50 mm/m) and multiple concrete strengths. Further, the innovative application of gene expression programming (GEP) to develop an empirical model provides a practical tool for predicting the reduction in flexural capacity due to intermediate-span crack-induced debonding. The findings offer valuable insights that can lead to improved design guidelines and more efficient, safe, and cost-effective strengthening techniques for existing infrastructure, ultimately contributing to enhanced durability and performance of RC bridges under increasing loads and deteriorating conditions.

3. Finite Element Modelling of Curved Soffit RC Beams Strengthened Using CFRP

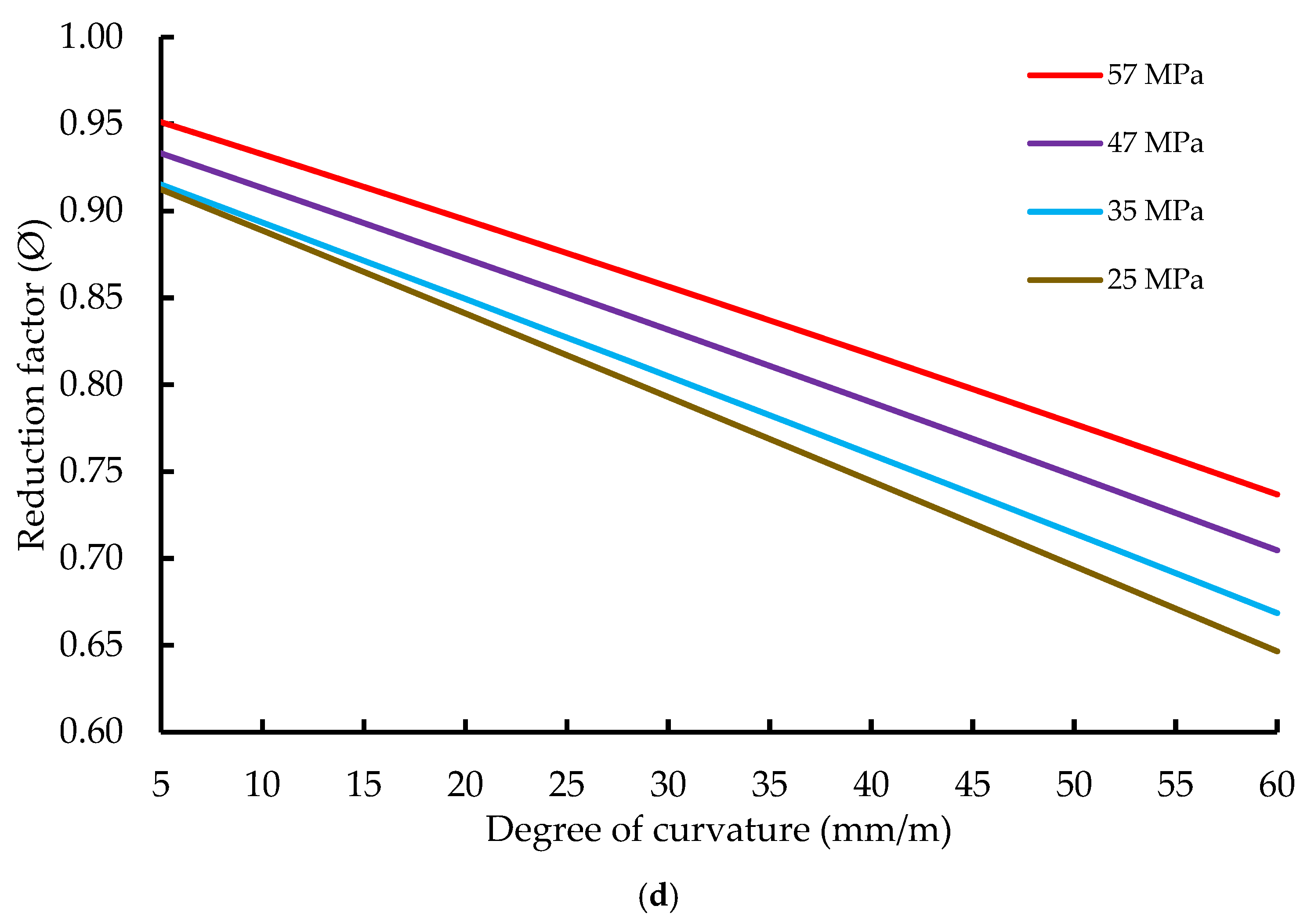

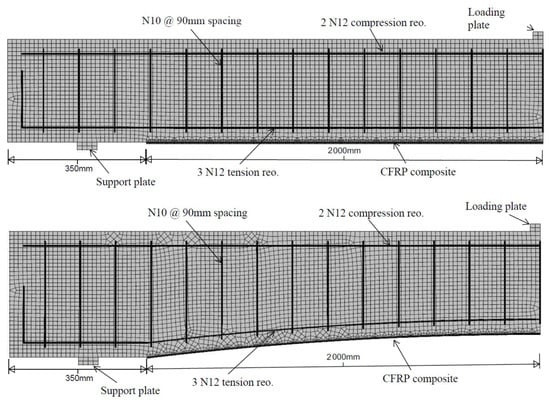

The finite element modelling described in this section was undertaken to supplement and extend the experimental findings reported by Al-Ghrery et al. [9] based in the specimens depicted in Figure 1. The modelling strategy initially involved simulating all strengthened and unstrengthened beams with both flat and curved soffit geometries in order to validate the numerical approach against the experimental results. This was subsequently followed by a series of parametric investigations examining the influence of concrete compressive strength and soffit curvature. The specimen geometry and experimental configuration adopted by Al-Ghrery et al. [9], which formed the basis for the numerical simulations, are illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Representative finite element models for both curved- and flat-soffit reinforced concrete (RC) beams are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 1.

(a) Flat soffit beam, (b) Typical curved soffit beam, and (c) Mid-span section and end-span section with varied depth, where d* denotes the beam depth at the supports which varies with soffit curvature [all dimensions are in mm]. Reproduced with permission from Al-Ghrery et al. [7].

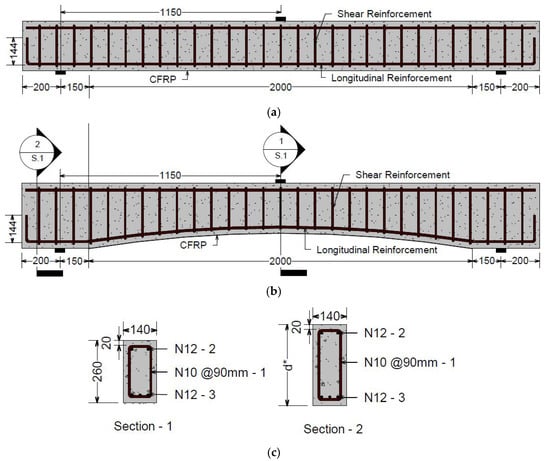

Figure 2.

A typical view of a beam during testing.

Figure 3.

FE model of flat and curved soffit beams.

Owing to symmetry in geometry, loading, and boundary conditions about the beam centreline, only half of each flat- and curved-soffit beam was modelled. All beams had an overall length of 2700 mm, a constant width of 140 mm, and a mid-span depth of 260 mm, irrespective of soffit curvature. For the curved-soffit specimens, the beam depth at the supports ranged from 280 mm to 340 mm, depending on the degree of curvature. Curved geometries were defined using curvature values of 5, 10, 15, and 20 mm/m over a chord length of 2000 mm located at the central region of the beam. The degree of curvature is defined as the maximum perpendicular offset between a curved surface and a straight reference edge of 1 m length placed against it. For instance, a curvature of 15 mm/m corresponds to a maximum normal deviation of 15 mm measured between the curved surface and the 1 m straight edge.

The externally bonded CFRP reinforcement was modelled over a length of 2000 mm in the central span and was terminated 350 mm from each beam end. The adhesive layer between the CFRP plate and the concrete substrate was assigned a uniform thickness of 1.5 mm. The assumption of a uniform adhesive thickness of 1.5 mm was adopted to reflect typical installation practice for externally bonded CFRP laminate systems and to ensure consistency across the numerical models. Manufacturer guidelines and design recommendations commonly specify adhesive thicknesses in the range of approximately 1–2 mm for CFRP laminate-to-concrete bonded systems in order to achieve effective stress transfer and avoid voids or incomplete wetting. The CFRP laminate and sheet thicknesses were taken as 1.4 mm and 0.337 mm, respectively. Longitudinal steel reinforcement was represented using three discrete 12 mm diameter bars in the tension zone and two 12 mm diameter bars in the compression zone. Shear reinforcement consisted of discrete two-legged stirrups formed from 10 mm diameter bars at a spacing of 90 mm along the beam length. A summary of the finite element models corresponding to the tested specimens is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of developed models.

The test specimens were divided into two primary categories. Category C comprised eight reinforced concrete beams with curved soffits strengthened using either FRP sheets or laminates, while Category F included two flat-soffit beams serving as reference specimens. The flat-soffit category incorporated three configurations based on the strengthening system employed: FRP sheet (S), FRP laminate (L), and an unstrengthened control specimen (C). The curved-soffit category adopted the same strengthening configurations as Category F, with each configuration further subdivided into four groups according to the soffit curvature, namely 5, 10, 15, and 20 mm per metre. The designation “FE” was used to differentiate numerical model results from the corresponding experimental observations.

In the finite element modelling, a relatively coarse mesh with an element size of 12 × 12 mm was employed for the concrete body, loading plate, and support plates. To accurately represent the CFRP laminate and adhesive layers, two refined mesh layers with an element size of 2 × 2 mm were adopted, while the CFRP sheet was modelled using a single macro-element layer with a mesh size of 0.5 × 0.5 mm. Previous mesh sensitivity studies on FRP-to-concrete bonded joints, reported by Kalfat et al. [20] and referenced in ACI 447.1 [19], demonstrated that a concrete element thickness of approximately 5 mm beneath the FRP laminate is required to reliably capture bond–slip behaviour. Accordingly, the concrete elements directly bonded to the FRP in the present model were assigned a thickness of 5 mm using a local mesh refinement. Consistent with this established guidance, the adopted mesh refinement of 5 mm was verified during modelling to ensure numerical stability and mesh independence. No deviation in results were observed with further mesh refinement,

The concrete, loading plates, support plates, and CFRP materials were modelled using plane quadrilateral elements. These isoparametric elements, incorporating either four or nine integration points, employ Gauss integration and were found to be well suited for two-dimensional numerical simulations of the structural components considered in this study.

The steel reinforcement bars were modelled using 2-D truss elements. The 2-D truss elements were isoparametric elements with one or two integration points integrated by Gauss integration for elements with two or three element nodes. These elements consisted of two nodes with two degrees of freedom in translation and one in rotation. The steel reinforcement nodes were superimposed over the concrete nodes and connected to the concrete elements through a structural interface. The slip was disabled at the bar beginning and end for the compression and tension reinforcement bars. It should be noted that the reinforcement bar elements available in the ATENA v5.9 were axial truss elements, which neglect bending and dowel stiffness. Since the governing response in our study is flexural, and the contribution of reinforcement bending and dowel action to the global flexural capacity is minimal, neglecting these effects is not expected to materially affect the results.

3.1. Material Models

3.1.1. Concrete

Concrete is known to be a quasi-brittle material for which failure is caused by fracture rather than plastic yielding. Concrete failure is represented by both crushing behaviour due to compressive stress and cracking due to tensile stress. Non-linear plasticity models were used to describe non-linear compressive behaviour, whereas a concrete smeared crack approach and strain softening law were used to capture the tension behaviour of concrete. Recent studies have also investigated advanced numerical approaches for modelling concrete fracture and cracking processes at the mesoscale. For example, Yu et al. [21] proposed an improved meshless method capable of capturing crack initiation and propagation in concrete containing random aggregates and initial defects. While such mesoscale approaches provide valuable insight into fundamental cracking mechanisms, their computational cost and modelling complexity make them impractical for large-scale parametric studies of FRP-strengthened RC members, such as those undertaken in the present work.

In this study, concrete was modelled using the 3D Non-Linear Cementitious 2 model in ATENA 2D [22]. This model was developed based on the smeared crack approach and refined crack band theory. Two crack models are available for simulating crack orientation: rotating and fixed crack model. The rotating crack model updates the crack orientation during the computational process depending on the principal stress directions in a given load step. In contrast, the fixed crack model fixes the crack orientation during all steps in the analysis based on the crack initiation orientation. Thus, rotating crack model is used in this study to avoid stress-locking problems.

The FE models of the tested RC beams explored two concrete grades, as shown in Table 1. The input parameters of the concrete model were as follows: modulus of elasticity (), cylinder compressive strength (), tensile strength (), Poisson’s ratio () and mode 1 specific fracture energy (). These mechanical properties were obtained from the experimental results reported by Al-Ghrery et al. [9], with the exception of the specific fracture energy. Mode 1 specific fracture energy is calculated in accordance with VOS [23], as shown in Equation (1) below:

(MN/m)

The input parameters of the two concrete grades are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of concrete.

Although interfacial stresses are predominantly shear-driven, FRP debonding initiation in flexurally strengthened RC members is governed primarily by Mode I tensile fracture of the concrete substrate; accordingly, Mode I fracture energy was adopted in line with established numerical modelling practice and ACI 447.1 [19] recommendations.

3.1.2. CFRP Composite and Adhesive

Two CFRP strengthening systems were simulated as part of this study: a CFRP laminate system and a wet lay-up CFRP system. The CFRP laminate system was modelled using one macro-element layer for the adhesive and one layer for the laminate. The laminate was modelled using a plane stress elastic isotropic material with a macro-element thickness of 1.4 mm thick layer. The laminate adhesive was modelled between the laminate and the concrete using the Von Mises plasticity model applied to the 1.5 mm thick adhesive layer. The CFRP wet lay-up system was modelled using a single microelement with a thickness of 0.337 mm which corresponded to the dry fibre thickness of the CFRP sheet. Like the laminate plate, a plane stress elastic isotropic material model was used to model the CFRP sheet. The mechanical properties of the CFRP composite and adhesive were based on the properties reported by Al-Ghrery et al. [9].

3.1.3. Concrete–CFRP Interface

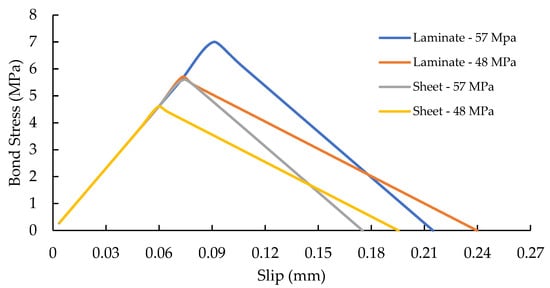

The concrete–CFRP interface is a crucial element, as it captures the bond between the CFRP and concrete. An interface material model was used to simulate the contact between the FRP and the concrete. The interface was based on Mohr–Columb criterion [22] and was represented using the following parameters: maximum bond stress (MPa), friction coefficient, concrete tensile strength (MPa), normal stiffness (MN/m3) and tangential stiffness (MN/m3). In this study the bond–slip model developed by Lu et al. [24] was used to determine the interface properties for beams strengthened with either CFRP laminate or CFRP sheet. Table 3 summarises the maximum bond stress, normal and tangential stiffnesses for each concrete grade used in the models. A friction of coefficient of 0.01 was assigned for all models regardless of the concrete strength and the CFRP system. Figure 4 summarises the bond–slip curves for CFRP laminate and sheet for each concrete strength respectively.

Table 3.

Mechanical properties of concrete–FRP interface.

Figure 4.

Bond–slip model of the CFRP laminate/sheet.

The tensile strength of the interface was assumed to be equivalent to the weakest of the materials being connected through it and was governed by the tensile strength of the concrete.

3.1.4. Steel Reinforcement

The steel shear stirrups were modelled using a bi-linear stress–strain law (elastic perfectly plastic), based on the results of the experimental testing reported by Al-Ghrery et al. [9]. The longitudinal compression and tension steel reinforcement material was modelled using the multi-linear stress–strain law, which has four distinct stages of steel behaviour: elastic, yield plateau, hardening and fracture. The five points defining the stress–strain diagram of the multi-linear stress–strain law were obtained from uniaxial testing of the bars, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Steel reinforcement multi-linear stress–strain input parameters.

3.1.5. Concrete–Steel Interface

Since the bond between the concrete and the longitudinal compression and tension steel reinforcement is influenced by concrete cracking, a bond model was introduced between the concrete elements and the longitudinal reinforcement elements to capture the behaviour of the reinforcement-to-concrete bond. The model developed by Bigaj [25] was implemented to represent the bond–slip relationship between the longitudinal compression and tension steel reinforcements and concrete. The bond–slip relationship of the model depends on the concrete cubic compressive strength, the reinforcement bar diameter and the bond quality (very good, good, or poor). The bond between the concrete and the shear stirrups was assumed to be a perfect connection as it did not influence the results.

3.1.6. Loading and Supporting Plates

Elastic isotropic plane stress material was used for both the loading and supporting plates. Both plates had a steel modulus of elasticity of 200,000 MPa and a Poisson’s ration of 0.3.

3.2. Loading Protocol and Boundary Conditions

All beams were simulated as simply supported and subjected to three-point loading configuration as per the experimental setup depicted in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Prior to application of loading, a shrinkage varying between 400-μɛ and 450-μɛ (depending on the concrete strength and curing period) was applied to the concrete elements to capture the loss in the tensile strength of concrete during the curing period. The internal restraint provided by the steel reinforcement prevented volumetric changes in concrete due to shrinkage, leading to shrinkage cracking and reduction in the concrete tensile strength. This shrinkage was applied gradually over the initial 10 steps with 10% of the total shrinkage applied in each step. The total amount of concrete shrinkage was calculated using the prediction model provided by ACI 209R-92 [26]. A vertical displacement control loading was then applied to the loading plate at a rate of 0.1 mm per step. The specimen was supported horizontally along the line of symmetry and vertically at the supporting plate, as depicted in Figure 3.

3.3. Solution Procedure

An iterative Newton–Raphson solution method was used at each loading step to bring the internal displacement and forces into equilibrium. A maximum number of 40 iterations was set for each load step. Convergence criteria and error tolerances were set for the solution method as follows: displacement error tolerance 0.01, residual error tolerance 0.01, absolute error tolerance 0.01 and energy error tolerance 0.0001.

3.4. Verification of Models

A comparative study was carried out between the simulated models and the experimental results from Al-Ghrery et al. [9] in order to validate the 2-D models. The load vs. mid-span displacement, the crack patterns and failure mode, and the CFRP strain were used for comparison and validation.

3.4.1. Load vs. Mid-Span Displacement

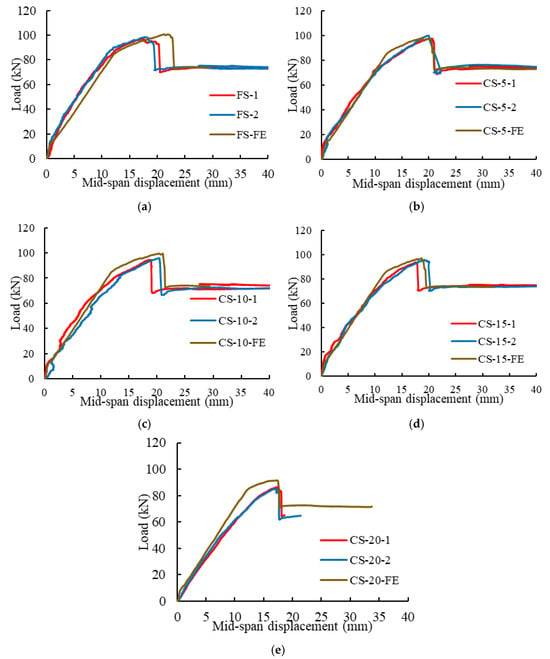

In this section, a comparison between the load vs. mid-span displacement between the numerical and experimental results is established. The behaviour of the flat and curved soffit beams strengthened with CFRP sheet/laminate can be described by three slope-change stages on the response curve, the first change being attributed to concrete cracking in the tension zone at early stage of loading, the second change occurs at the point of yielding of the tensile reinforcement and the last stage is related to CFRP composite de-bonding where the strength of the specimen reverts back to the unstrengthened capacity.

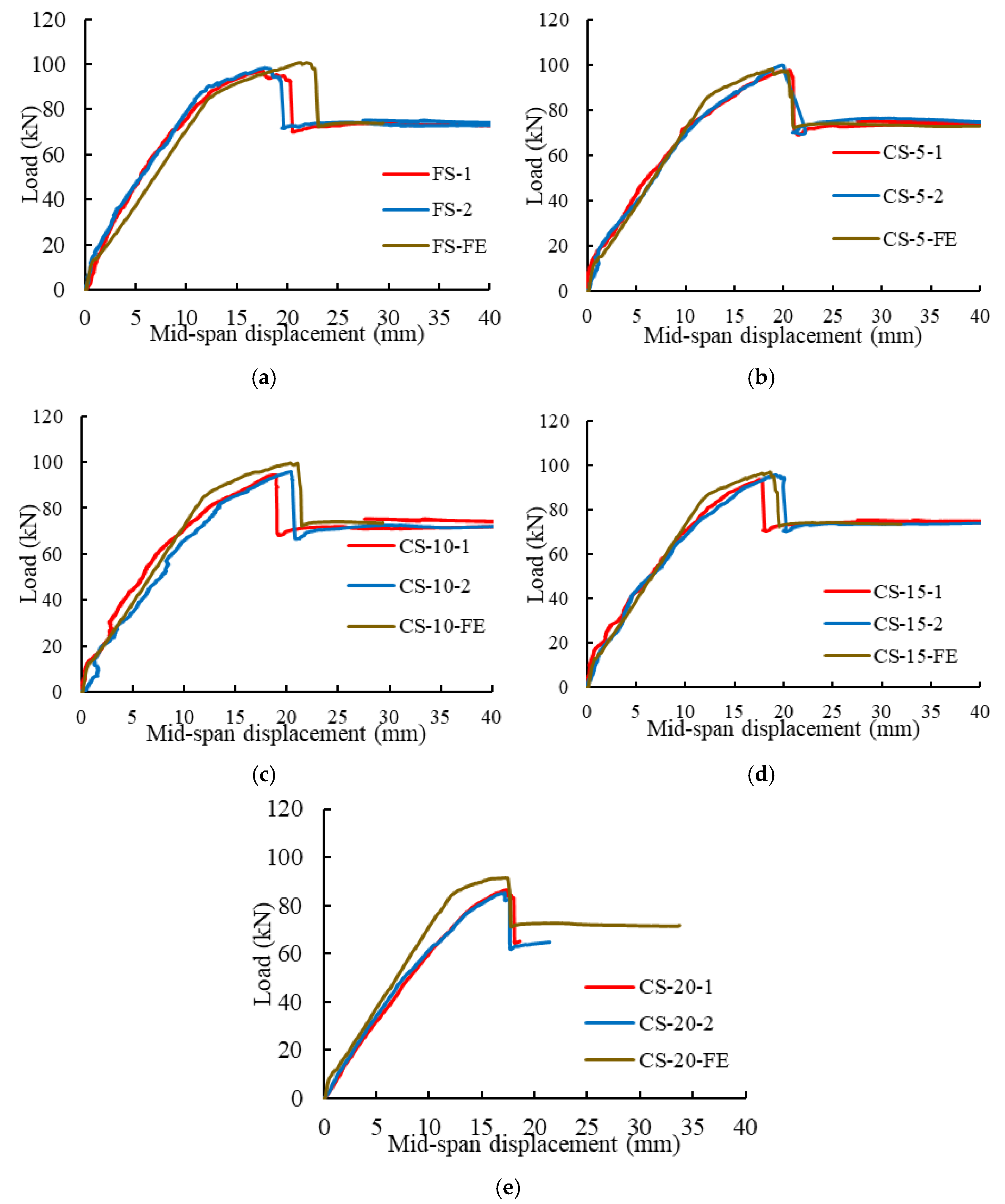

Figure 5 depicts the load displacement curves including experimental and finite element (FE) results for beams strengthened with CFRP sheet for different levels of curvature ranging from flat to 5–20 mm/m. The load-carrying capacity attained by the models for the flat soffit beams and 5 mm/m, 10 mm/m, 15 mm/m and 20 mm/m curved beams were 101 kN, 98.2 kN, 99.6 kN, 96.9 kN, and 91.5 kN, respectively. These peak loads were within 10% of the experimental peak loads. In fact, the difference between the experimental peak loads and the loads obtained from the 2-D models for flat soffit beams and 5 mm/m, 10 mm/m, 15 mm/m and 20 mm/m curved beams were −3.6%, −0.7%, −2.2%, 0.5%, and 6.2%, respectively, as summarised in Table 5. Further, the stiffness and displacement at peak load obtained from the 2-D models were in good agreement with the results of the experimental testing.

Figure 5.

Comparison of load vs. mid-span displacement behaviour for beams strengthened with CFRP sheet (a) Flat soffit beams, (b) 5 mm/m, (c) 10 mm/m, (d) 15 mm/m and (e) 20 mm/m curved soffit beams.

Table 5.

Summary of the load-carrying capacity obtained from the 2D models compared to the experimental testing.

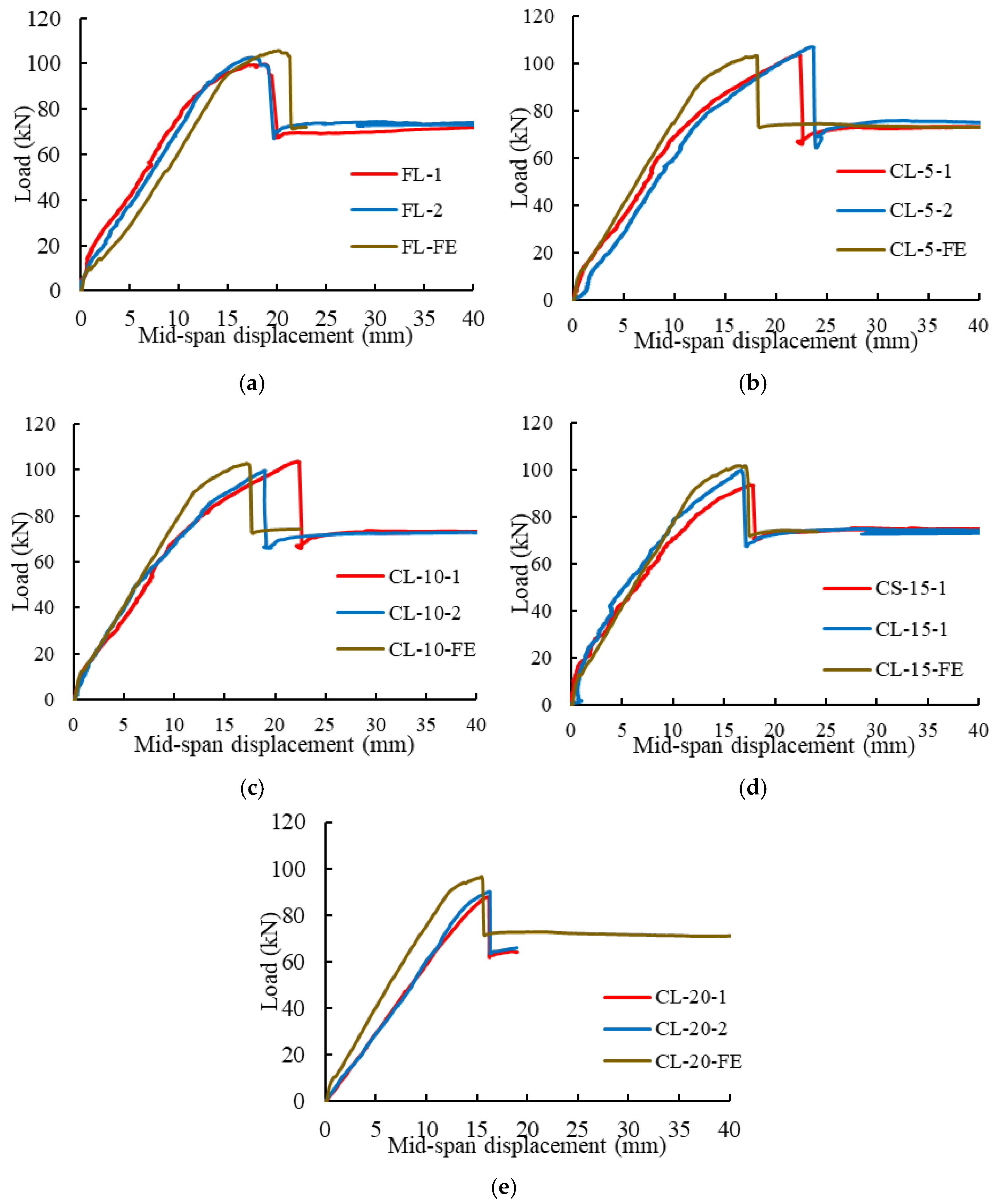

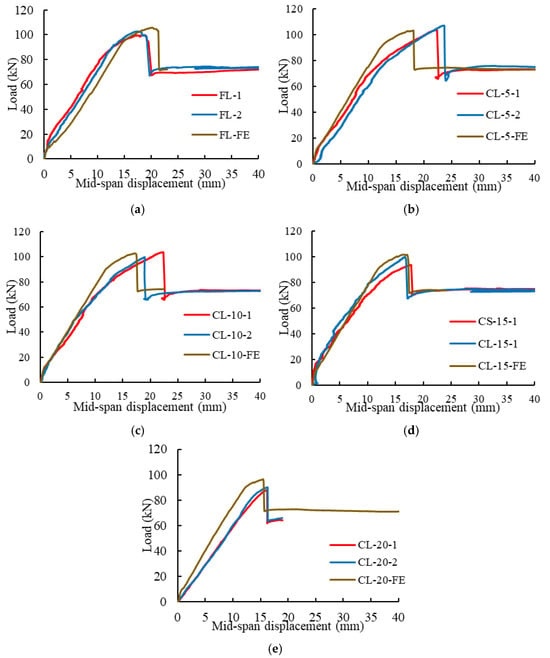

Figure 6 shows a comparison of beams strengthened with CFRP laminate and simulated models of flat and curved soffit beams. The load-carrying capacity attained by the 2-D model for the flat soffit beams and 5 mm/m, 10 mm/m, 15 mm/m and 20 mm/m curved beams is 105.8 kN, 103.1 kN, 102.8 kN, 101.7 kN, and 96.5 kN, respectively. These peak loads are within less than 10% of the experimental peak loads. In fact, the difference between the experimental peak loads and the loads obtained by the 2-D models for flat soffit beams and 5 mm/m, 10 mm/m, 15 mm/m and 20 mm/m curved beams is −8.5%, −5.7%, −5.4%, −4.3%, and 1.0%, respectively, as summarised in Table 5. Furthermore, the stiffness and displacement at peak load obtained from the 2-D models are in good agreement with the results of the experimental testing.

Figure 6.

Comparison of load vs. mid-span displacement behaviour for beams strengthened with CFRP laminate (a) Flat soffit beams, (b) 5 mm/m, (c) 10 mm/m, (d) 15 mm/m and (e) 20 mm/m curved soffit beams.

Overall, the 2-D FE models presented satisfactory results and captured the load vs. mid-span displacement behaviour accurately. Therefore, the models were considered successfully validated and could be used for the next stage of parametric studies to investigate additional degrees of curvature and the impact of concrete compressive strength on the capacity of curved soffit beams strengthened with FRP.

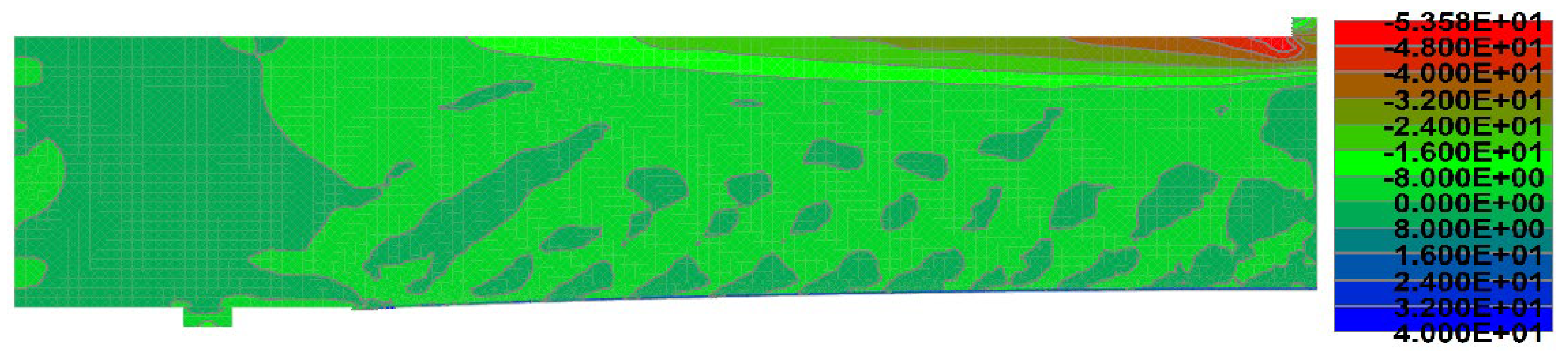

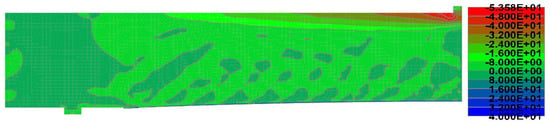

The steel reinforcement stresses at the peak load reported in Table 5 were indicative that reinforcement yielded prior to failure in all cases. Failure followed by CFRP IC de-bonding. Figure 7 shows a typical concrete compressive stress at the peak load.

Figure 7.

Concrete compression stress distribution in a 5 mm/m beams.

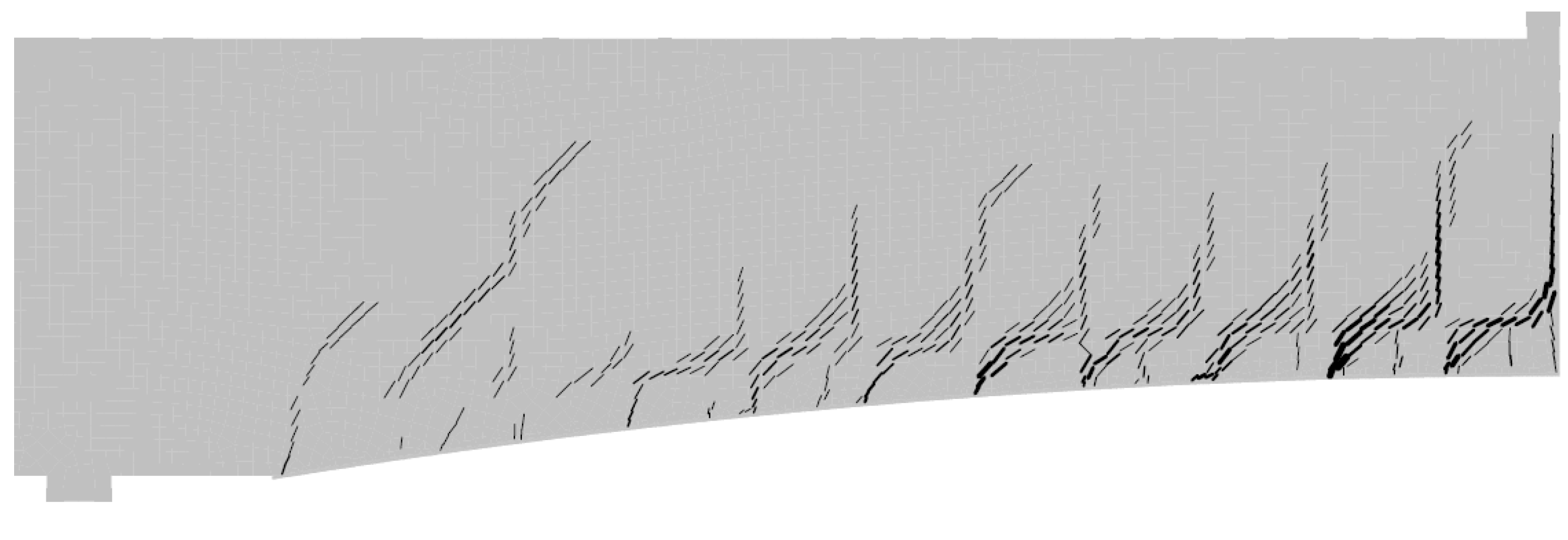

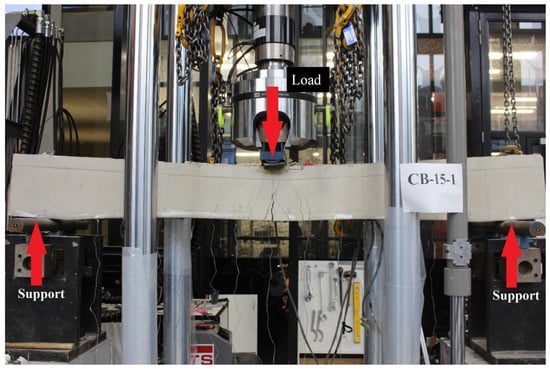

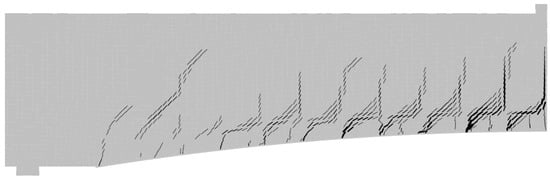

3.4.2. Crack Patterns and Failure Mode

Figure 8 presents representative crack patterns at peak load for curved soffit beams externally strengthened with CFRP. The numerical finite-element simulations showed that, for beams strengthened using either CFRP sheets or CFRP laminates, the dominant cracking mode consisted primarily of vertical flexural cracks concentrated at the mid-span region. This cracking behaviour suggests that CFRP de-bonding was likely initiated at mid-span, which is consistent with the experimental observations reported by Al-Ghrery et al. [9].

Figure 8.

Crack patterns of beams strengthened with CFRP laminate with 20 mm/m curved soffit depicting maximum crack width of 0.9 mm.

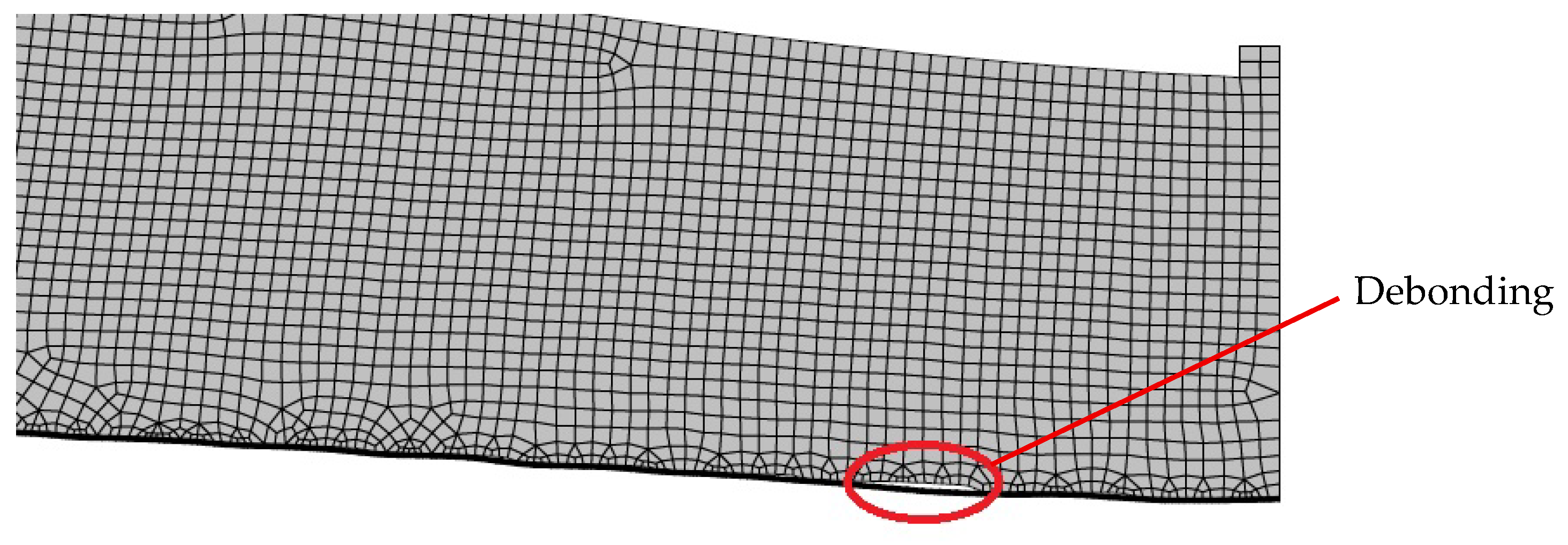

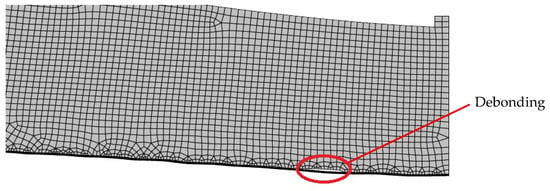

Figure 9 illustrates the deformed configurations of curved soffit beams strengthened with CFRP sheets and CFRP laminates, respectively, at load levels close to the peak capacity. The deformation profiles shown in this figure further confirm that de-bonding originated in the mid-span region, in agreement with the findings from the experimental tests. The observed failure mechanism corresponds to intermediate-span crack-induced (IC) de-bonding, which was triggered by the development of flexural and flexure-shear cracks within the intermediate portions of the beam span. In this mechanism, de-bonding initiated at the crack tip and subsequently propagated toward the end of the FRP reinforcement. For IC de-bonding, the progression of the failure surface typically occurred along the adhesive–concrete interface.

Figure 9.

Deformed shape of beams strengthened with CFRP laminate with curved soffit of 20 mm/m.

3.4.3. CFRP Composite Strain

Strains in the CFRP were observed to be highest in the experiments at locations where the CFRP bridged major flexural cracks. As a result, strain variations were observed along the length of the CFRP where the peak strains corresponded to the major flexural crack locations and lower strains were observed in between cracks. This can be clearly observed in the results reported by Al-Ghrery et al. [9]. In contrast, the smeared crack model implementation in the FE model resulted in a more uniform crack pattern and consequently, smaller spacings between major cracks when compared to the experimental results. Hence, the FE was unable to accurately capture the strains in the FRP and showed high sensitivity to crack spacing and distribution. The maximum strain values reported in Table 6 for each respective FE model were derived based the peak load achieved and assuming perfect strain compatibility between the concrete and CFRP.

Table 6.

Summary of CFRP strain at mid-span obtained from the 2D models compared to the experimental testing.

Table 6 summarises the maximum CFRP strains recorded from the experimental results and compares them with those obtained from the finite element predictions. The calculated CFRP laminate strain values at mid-span for flat, 5 mm/m, 10 mm/m, 15 mm/m and 20 mm/m are −3.3% to 12.9%, 7.7% to 21.6%, 4.2%, −1.1 to 7.7% and −6.2% to −10.4% from the experimental results, respectively. The CFRP sheet calculated strain values at mid-span for flat, 5 mm/m, 10 mm/m, 15 mm/m and 20 mm/m are −30.8% to −8.5%, −9.4% to −2.2%, −14.4% to −7.4%, −20.8% to −13.4% and −8.9% to −12.9% from the experimental results, respectively.

The significant difference observed in the beams strengthened with CFRP sheet is due to the nature of smeared crack model as the CFRP strains are sensitive to cracks along the width of the CFRP sheet. Moreover, wider CFRP sheet, 100 mm, leads to more cracks being distributed evenly compared to the CFRP laminate width of 50 mm.

3.5. Parametric Study into Concrete Compressive Strength and Degree of Soffit Curvature

In this section, parametric studies were carried out to investigate the effect of different concrete compressive strengths and degrees of soffit curvatures greater than 20 mm/m on the performance of CFRP-strengthened beams.

3.5.1. Parametric Study on the Degrees of Soffit Curvature

The influence of the degree of soffit curvature beyond 20 mm/m was investigated to examine any further reductions in efficacy of FRP strengthened RC beams and supply the required data for design guideline development. To achieve this objective, FE models were created for an additional six degrees of curvature beyond 20 mm/m, including 25 mm/m, 30 mm/m, 35 mm/m, 40 mm/m, 45 mm/m, and 50 mm/m, while keeping all other parameters including concrete strength properties, FRP-to-concrete bond slip models, reinforcement bond slip model, reinforcement properties, mesh size, element type, loading arrangement and solution parameters set as per previous FE models with soffit curvatures less than 20 mm/m, presented in previous sections.

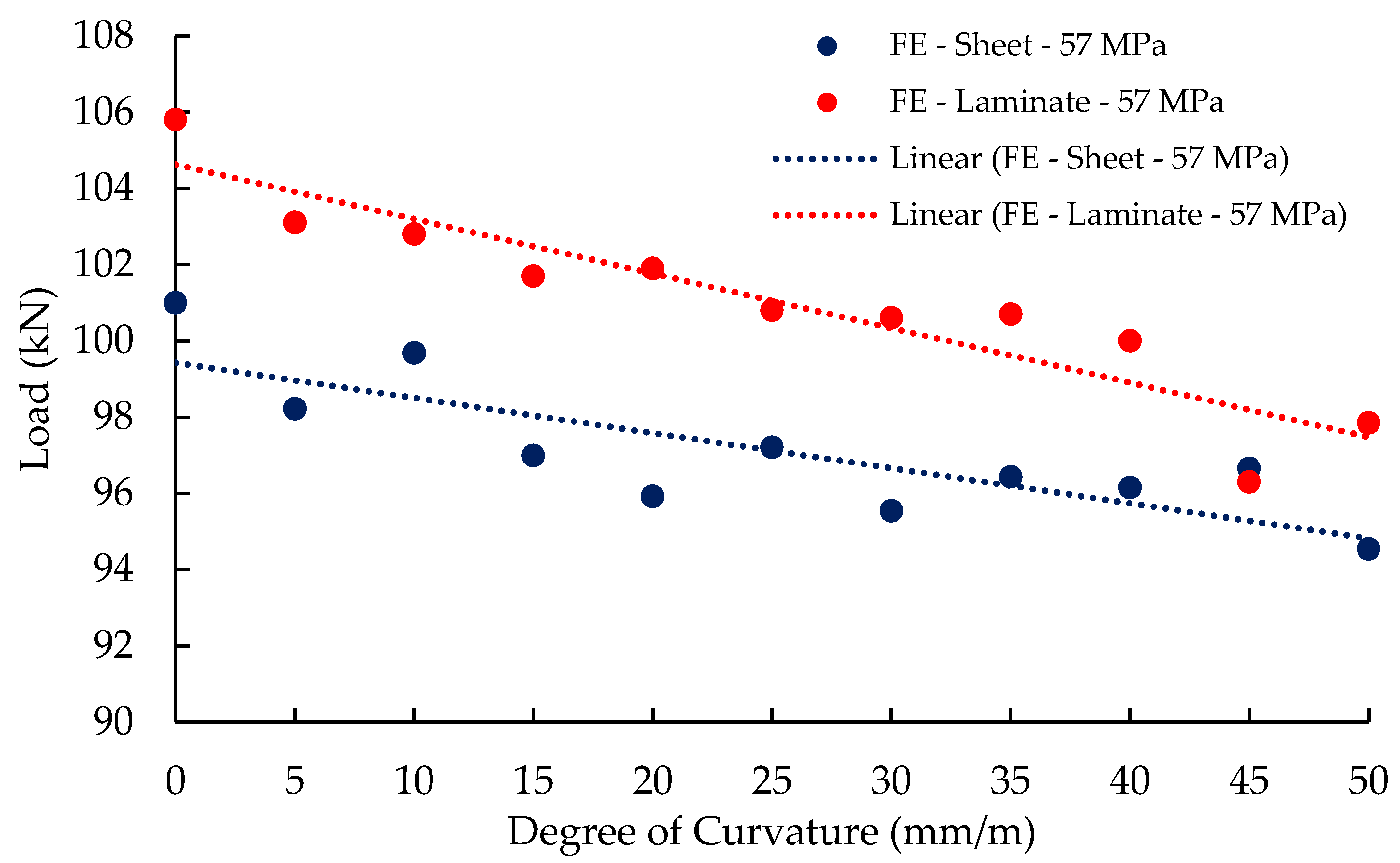

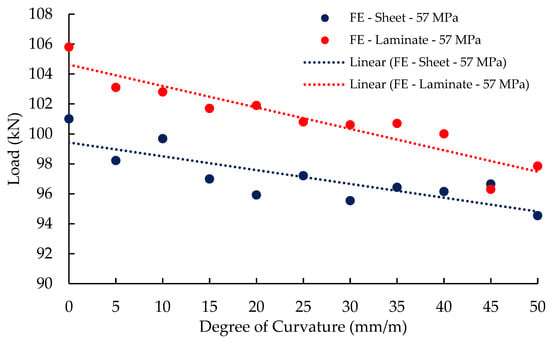

Figure 10 summarises the peak loads attained from the FE models at the various degrees of curvatures explored. The descending trend observed in the figure for beams strengthened with either CFRP sheet or CFRP laminate confirm the findings of the experimental testing. The load-carrying capacity decreases with the increase in the degree of curvature.

Figure 10.

Summary of peak loads at mid-span section for the parametric study.

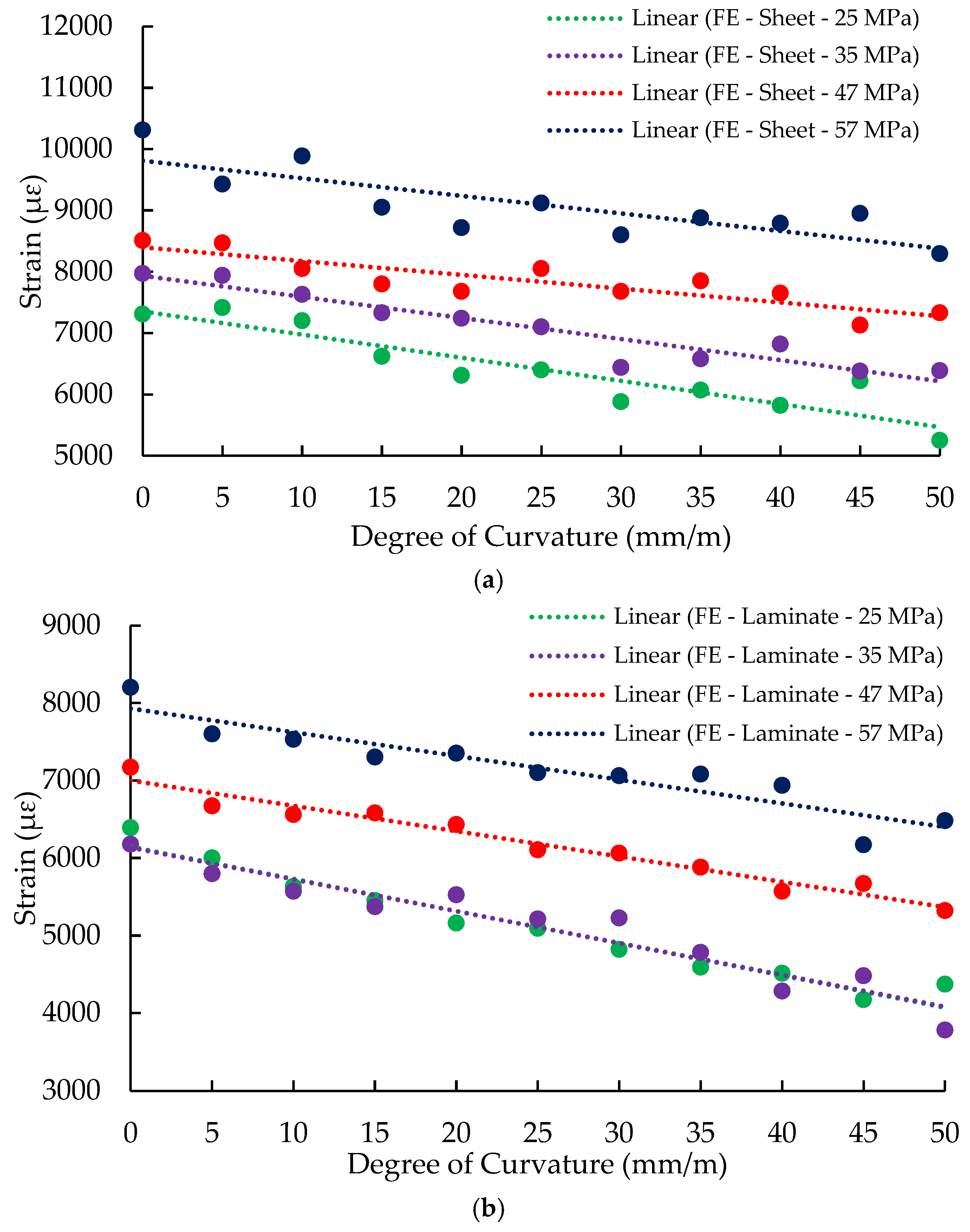

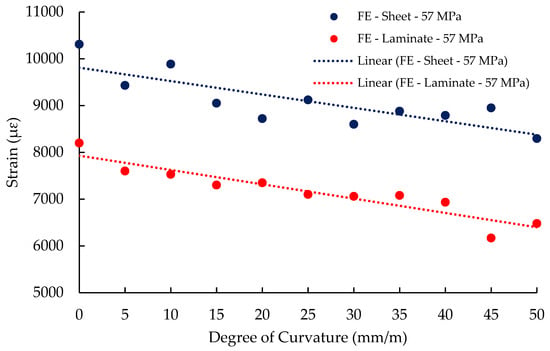

An equivalent procedure was adopted to determine the maximum strain developed in the CFRP composites at the corresponding peak load for each curvature level, based on the peak load data. Figure 11 presents a summary of the maximum mid-span CFRP strains computed for beams with flat soffits as well as for beams with curved soffits exhibiting curvatures of up to 50 mm/m. The decreasing trend evident in the figure for beams strengthened using either CFRP sheets or CFRP laminates corroborates the outcomes of the experimental investigations. Specifically, the CFRP strain magnitude was found to reduce as the degree of soffit curvature increased.

Figure 11.

Summary of maximum CFRP strain at mid-span section for the parametric study.

Further, the crack patterns observed in the parametric study models were similar to those in the previous models. Vertical flexural cracks were observed near the mid-span. In addition, the deformed shape showed intermediate-span crack-induced de-bonding initiation at the peak loads of these models.

3.5.2. Parametric Study on Concrete Compressive Strength

In order to investigate the interaction of concrete compressive strength when combined with soffit curvature, four concrete grades were investigated—57 MPa, 48 MPa, 35 MPa and 25 MPa—for beams with curvatures of 5 mm/m, 10 mm/m, 15 mm/m, 20 mm/m, 25 mm/m, 30 mm/m, 35 mm/m, 40 mm/m, 45 mm/m and 50 mm/m, resulting in a total of 88 models. In each model, the concrete grade and the parameters related to concrete compressive strength were changed and all other parameters kept constant for each degree of curvature. Table 7 summarises the mechanical properties of the different concrete grades.

Table 7.

Mechanical properties of different concrete grades.

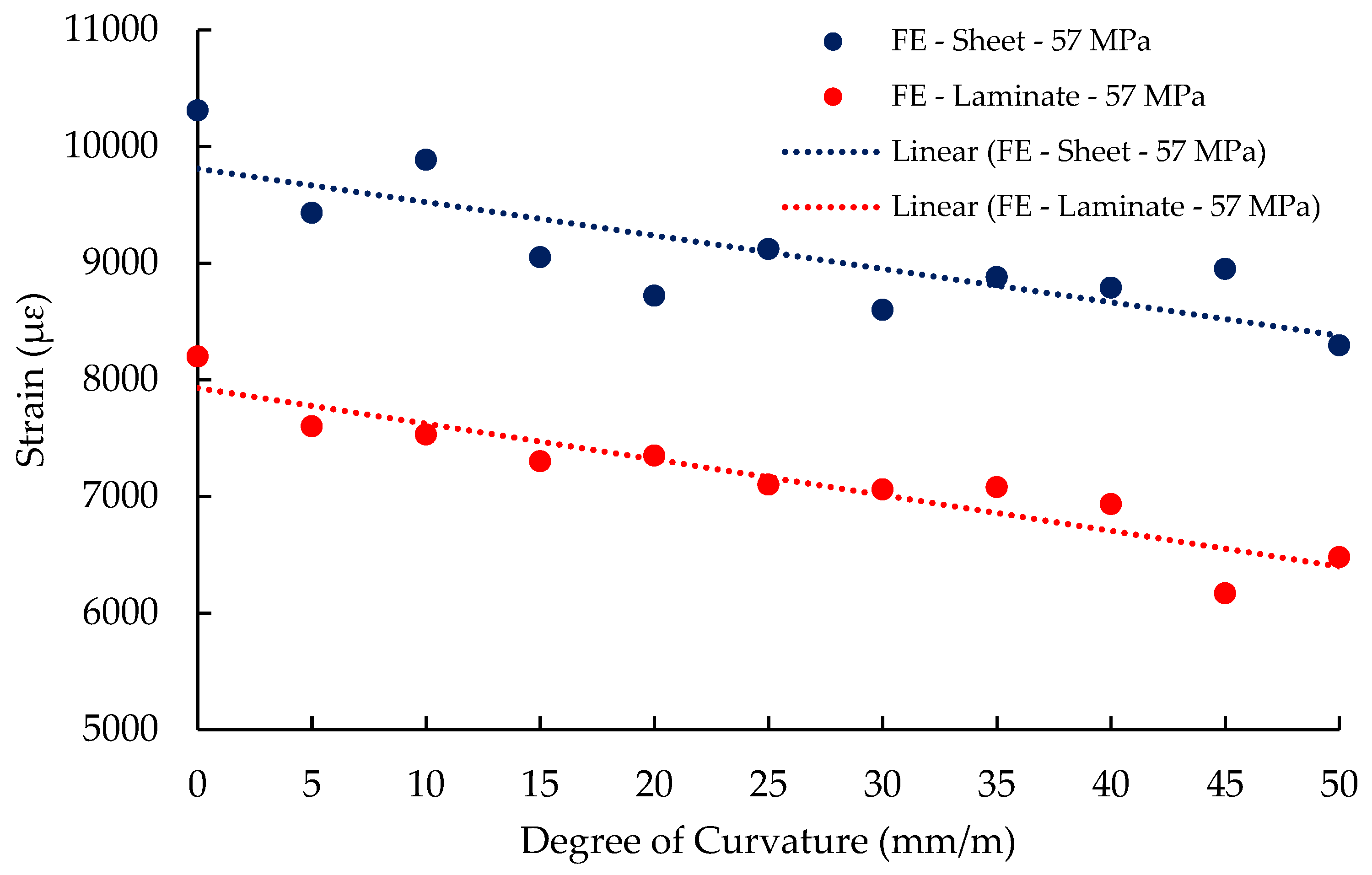

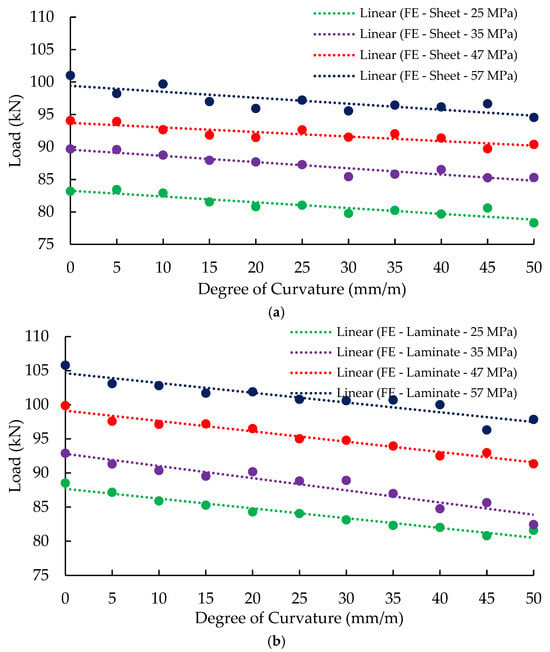

Figure 12 below summarises the maximum load attained for the four investigated concrete strengths for all degrees of curvature ranging from flat up to 50 mm/m. Four descending trend lines are observed for beams strengthened with either CFRP laminate or CFRP sheet. The observations in this figure confirm the findings of the experimental programme that the load-carrying capacity reduces with the increase in the degree of curvature. Moreover, the four parallel trend lines proves that concrete strength has a major impact on the load-carrying capacity. In fact, the load-carrying capacity reduces linearly with the reduction in the concrete compressive strength.

Figure 12.

Summary of maximum load at mid-span section (a) Beams strengthened with CFRP sheet, and (b) beams strengthened with CFRP laminate.

The reduction in the load capacity due to the reduction in the concrete compressive strength is attributed mainly to the tensile strength of the concrete. As lower concrete tensile strength leads to earlier FRP de-bonding due to weakness of the bond strength between the FRP and concrete.

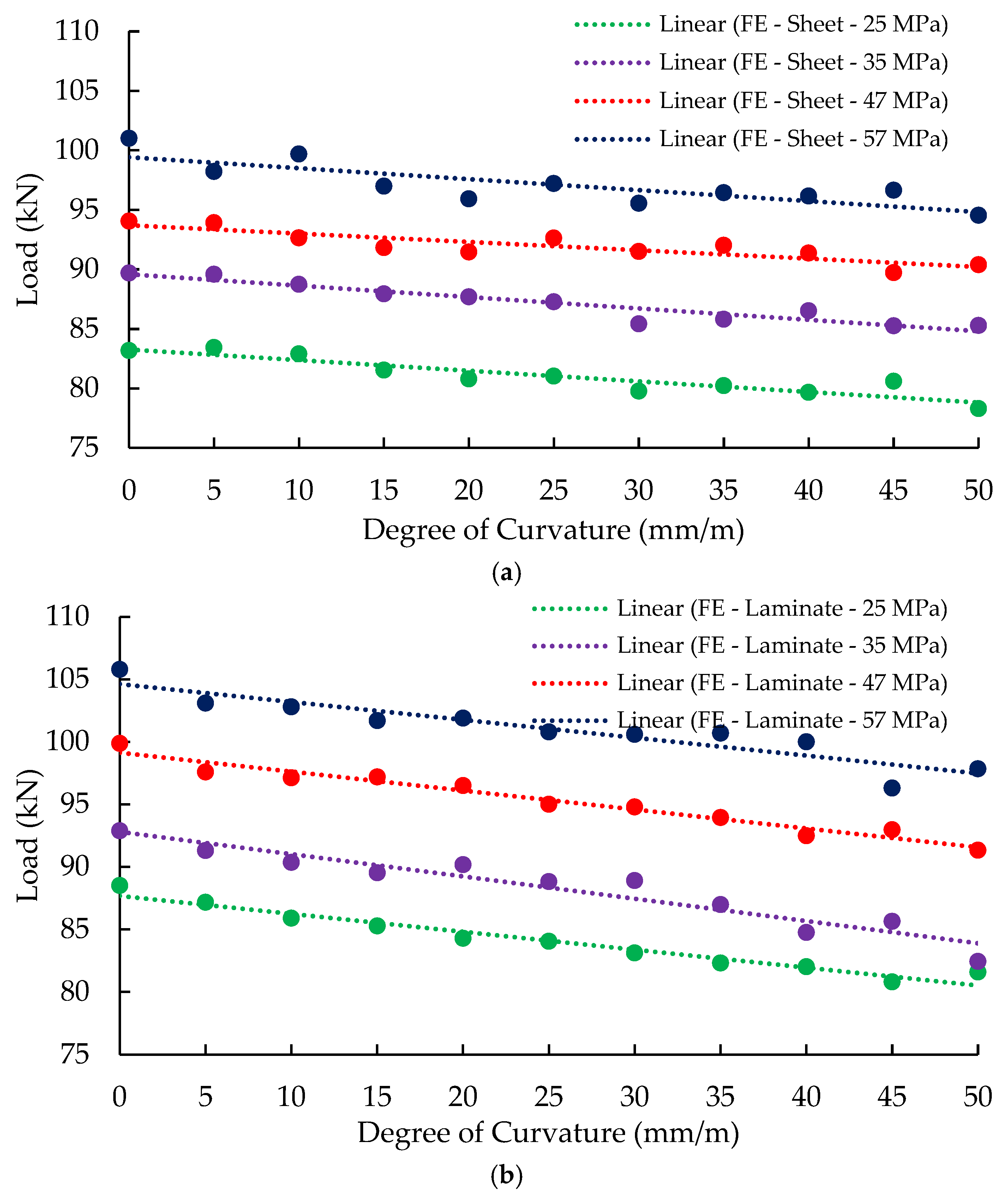

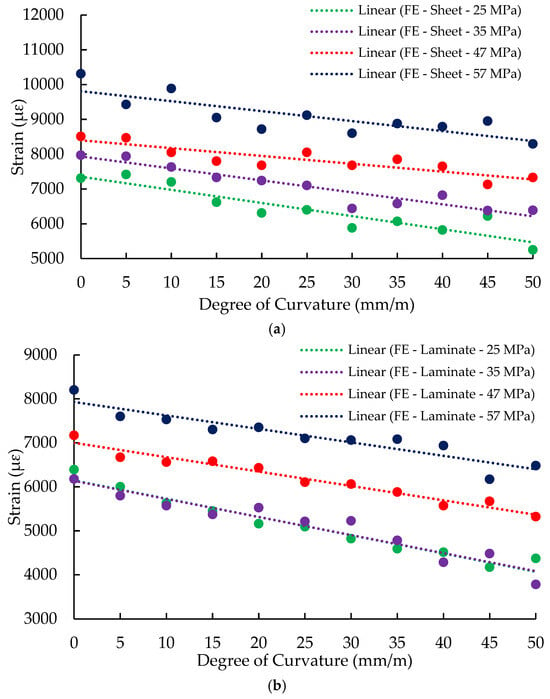

Figure 13 below summarises the maximum CFRP strain at mid-span for the four investigated concrete strengths and degrees of curvature from flat to 50 mm/m. Four descending trend lines are observed for beams strengthened with either CFRP laminate or CFRP sheet. These observations confirm the finding of the experimental programme that the CFRP strain at mid-span reduces with the increase in the degree of curvature. Moreover, the four parallel trend lines show that concrete strength has a major impact on the IC de-bonding CFRP strain. The trend lines of the 25 MPa and 35 MPa for beams strengthened with CFRP laminate coincide, showing that the influence of concrete strength fades away with lower concrete strength.

Figure 13.

Summary of maximum CFRP strain at mid-span section (a) Beams strengthened with CFRP sheet, and (b) beams strengthened with CFRP laminate.

The reduction in CFRP strain due to the reduction in the concrete compressive strength is attributed mainly to the tensile strength of the concrete, as lower concrete tensile strength leads to earlier FRP de-bonding due to the weakness of the bond strength between the FRP and concrete. Table A1 summarises the peak loads and CFRP strain values obtained from the 88 models.

4. Gene Expression Programming

4.1. Overview of Genetic Programming

Genetic expression programming (GEP) is an evolutionary, algorithm-driven technique introduced by Ferreira et al. [27] as an extension of genetic programming (GP) and genetic algorithms (GAs). It employs search-based optimisation to identify functional relationships between variables in order to model physical behaviour. Genetic programming, originally proposed by Koza [28], represents candidate solutions as nonlinear structures with varying forms and dimensions, commonly expressed as parse trees. In contrast, genetic algorithms encode mathematical expressions as fixed-length linear strings. GEP combines features of both approaches by representing solutions as fixed-length linear chromosomes (genomes) that are subsequently decoded into nonlinear expression trees of varying size and structure. A GEP-based model may consist of multiple expression trees (ETs), which are mathematically linked using operators such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, or division. Over the past decade, GEP has been successfully applied to a wide range of engineering problems, as demonstrated in several studies (Al-Mosawe et al. [29]; Murad et al. [30]; Emamgolizadeh et al. [31]; Ozbek et al. [32]).

4.2. Data Collection

In total, 95 data points were collected from both experimental results by Al-Ghrery et al. [9] and FE results. These data points relate to curved soffit RC beams with different degrees of curvature ranging from 5 mm/m to 50 mm/m. The database was split into two main groups for use in the GEP software which included training and validation data sets. The training data set included 80 data points extracted from the FE results while the validation dataset included 15 data points from the experimental results. Table A2 summarises the database used in the GEP. All specimens were split into two main categories. The beams consisted of two categories based on the type of strengthening composite as follows: sheet ‘S’ and laminate ‘L’. The numbering of the beams ID refers to the degree of curvature from 5 mm/m to 50 mm/m. FE designation is used to distinguish the models results from the XP designation of the experimental results. The input parameters adopted in the GEP model were the same parameters used to predict intermediate crack-induced FRP de-bonding by the design standards, which are FRP modulus of elasticity (), FRP thickness (), and concrete compressive strength (). Further, the degree of soffit curvature () was considered as a parameter in addition to the above parameters. The target parameter was the reduction in the FRP IC debonding strain of curved soffit beams compared to the flat soffit beams (). Table 8 illustrates the statistical values for all input parameters and output results.

Table 8.

Statistical values for all input and target parameters.

4.3. Genetic Programming Parameters

The proposed gene expression programming (GEP) model was developed and executed using the GeneXproTools 5.0 software package, which enables the explicit specification of the mathematical operator set available during the model construction process. In the present study, the defined operator pool included the four basic arithmetic operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division), as well as a suite of nonlinear operators. These nonlinear functions comprised polynomial expressions (x2, x3, and x4), root-based operators (√x, ∛x, and ∜x), exponential and logarithmic functions (exp, ln, log10, and 10x), in addition to the inverse function.

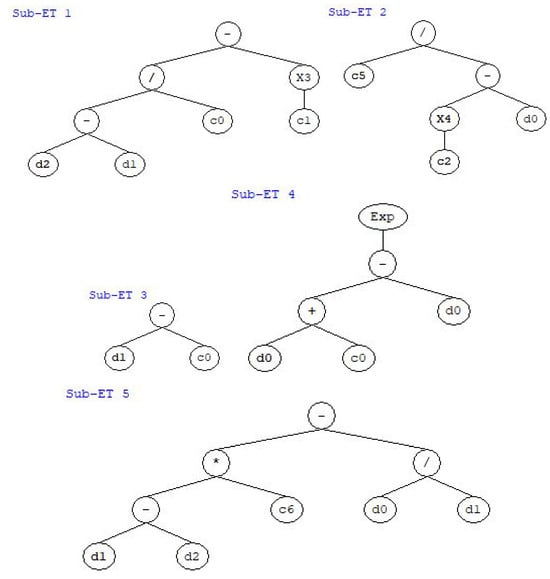

For each run, the genetic programming algorithm systematically assessed a large population of potential candidate expressions and selected the optimal combination of operators and functional forms that maximised the coefficient of determination (R2) while simultaneously minimising prediction error measures. The primary parameters governing the performance of the derived GEP model were identified as the number of genes (i.e., sub-expression trees), the head size, the total number of chromosomes, and the chosen set of mathematical operators. Overall, increases in the number of genes, head size, and chromosome count resulted in enhanced predictive accuracy, although these improvements were accompanied by a corresponding increase in the complexity of the resulting model. Of the linking functions evaluated, multiplication was found to be the most effective operator for connecting individual sub-expression trees.

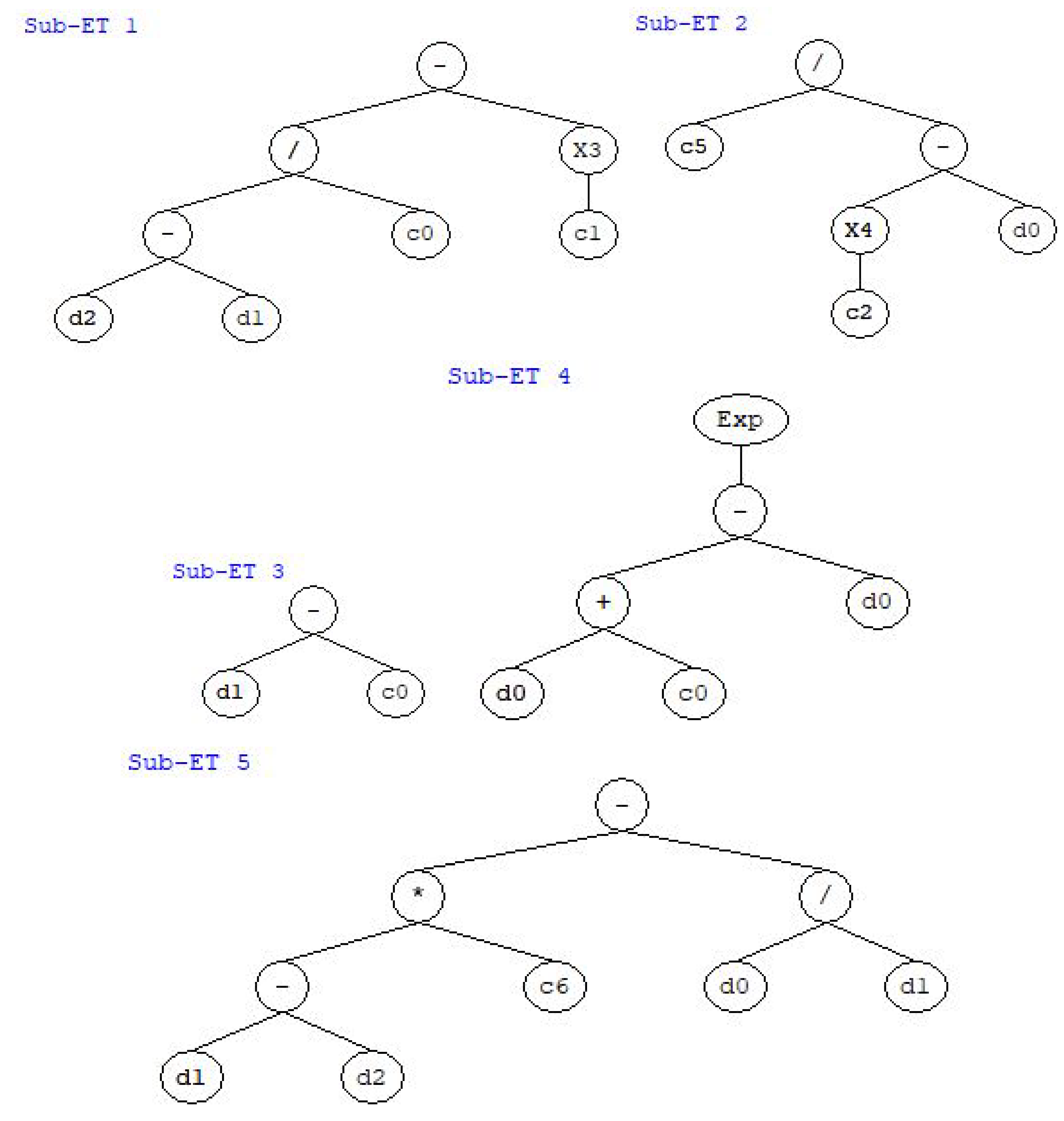

Model performance was assessed based on both predictive accuracy quantified by the R2 value, and structural complexity. The final model adopted in this study represents an optimal balance between simplicity and accuracy. The parameter settings used to derive the GP expression presented in Equation (2) are summarised in Table 9, while the corresponding expression trees are illustrated in Figure 14.

Table 9.

GEP model-setting parameters.

Figure 14.

Expression tree (ET) of proposed GEP model.

4.4. Genetic Programming Results

The proposed model extracted from the expression trees and simplified is expressed in Equation (2) below:

where denotes the soffit curvature gradient (mm/m), represents the concrete cylinder compressive strength (MPa), is the thickness of the FRP layer (mm), is the elastic modulus of the FRP (MPa), and is the corresponding capacity reduction factor associated with the specified curvature and combination of input parameters. The empirical coefficients used in the proposed model are summarised in Table 10.

Table 10.

Summary of empirical constants of GEP model.

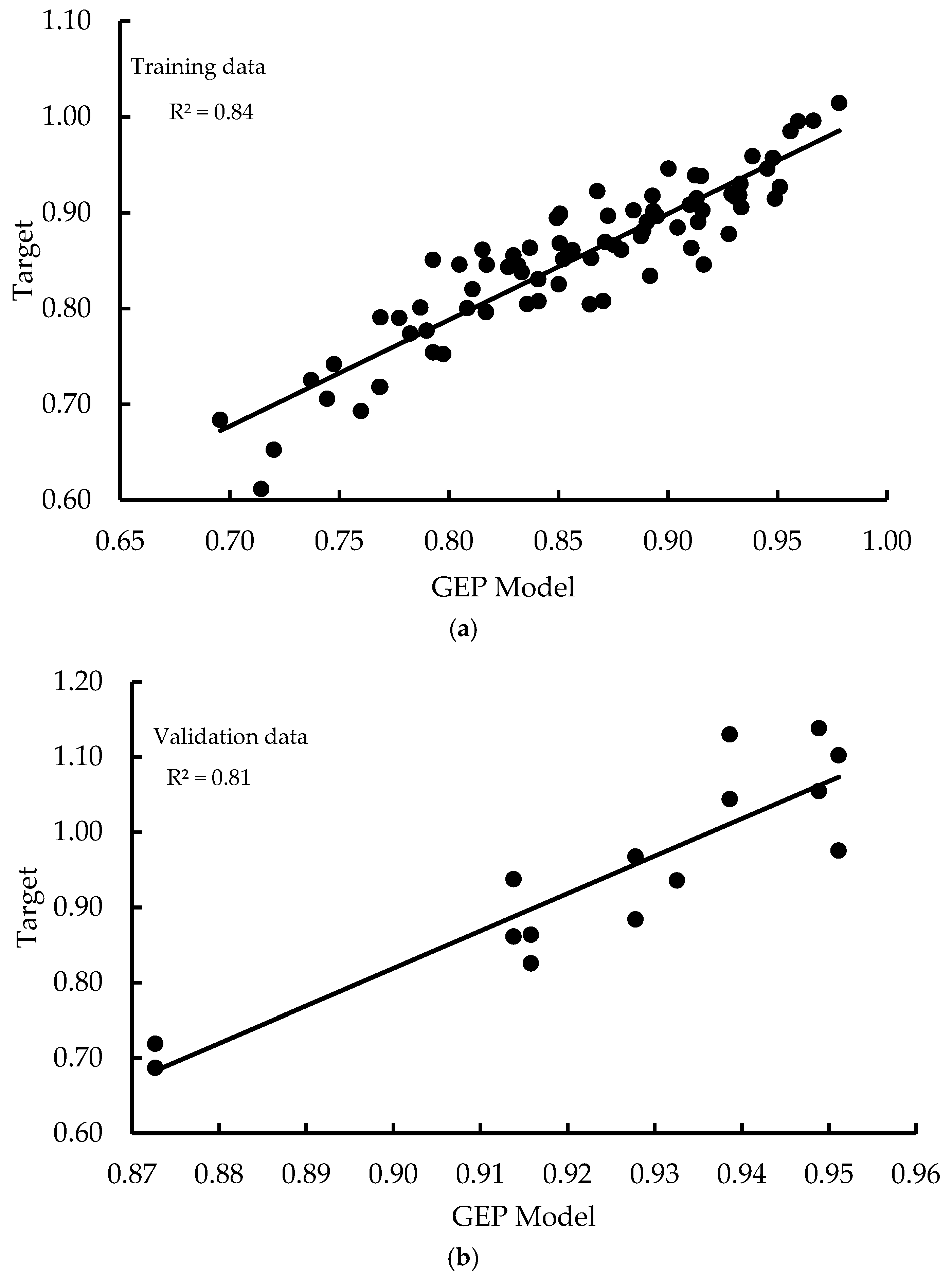

The prediction performance and generalisation ability of the developed GEP model were evaluated quantitatively through a range of statistical performance measures, namely the coefficient of determination (R2), mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), relative absolute error (RAE), and root relative squared error (RRSE). Each of these indicators was calculated using the formulations presented below:

where denotes the target value, is the mean of the target dataset, represents the total number of data points, is the corresponding model output, and is the mean of the predicted outputs. The minimum coefficient of determination (R2) and the maximum error metrics were obtained from the evaluation using the training dataset, whereas the highest R2 values and lowest prediction errors were achieved during validation.

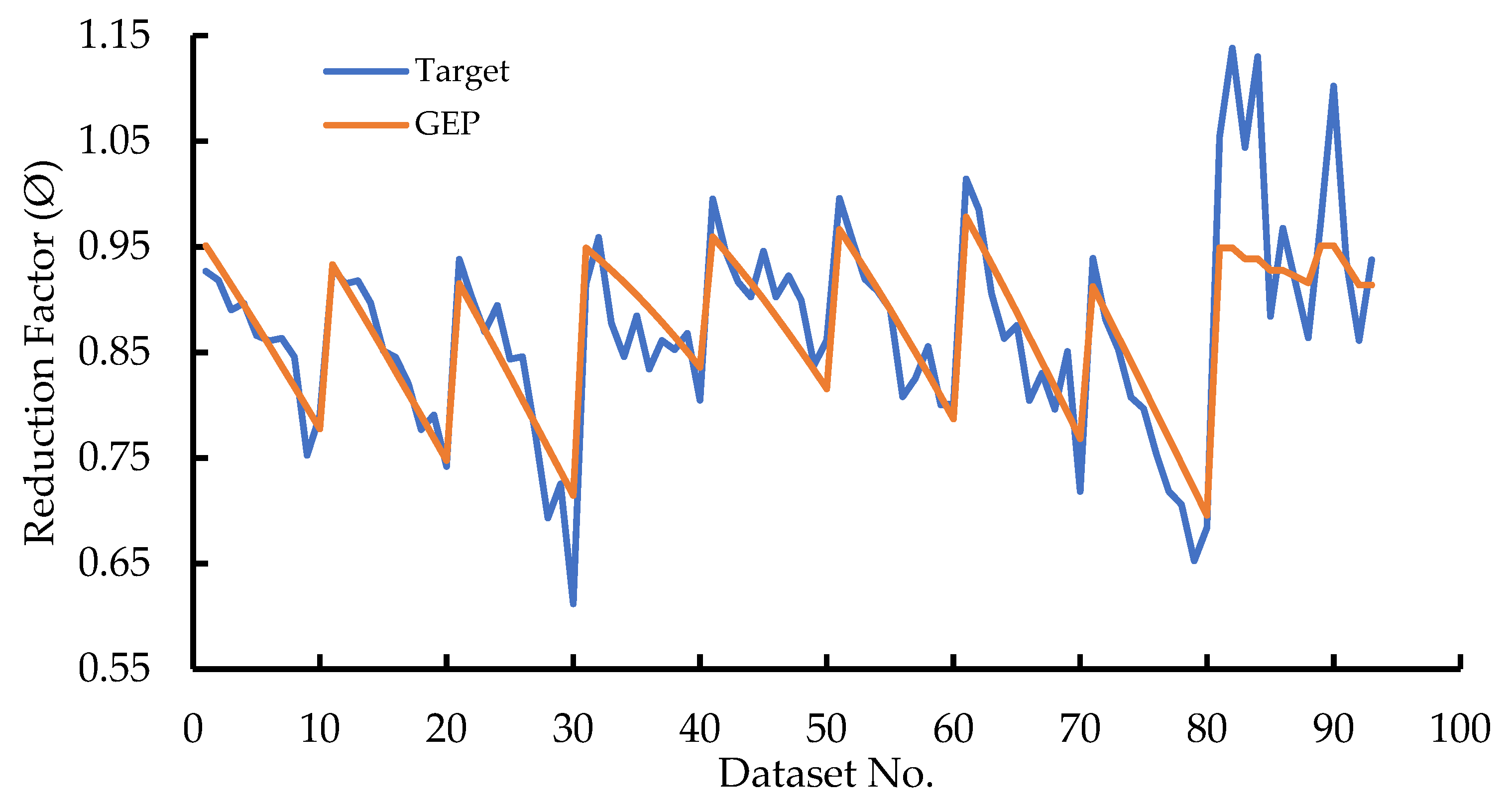

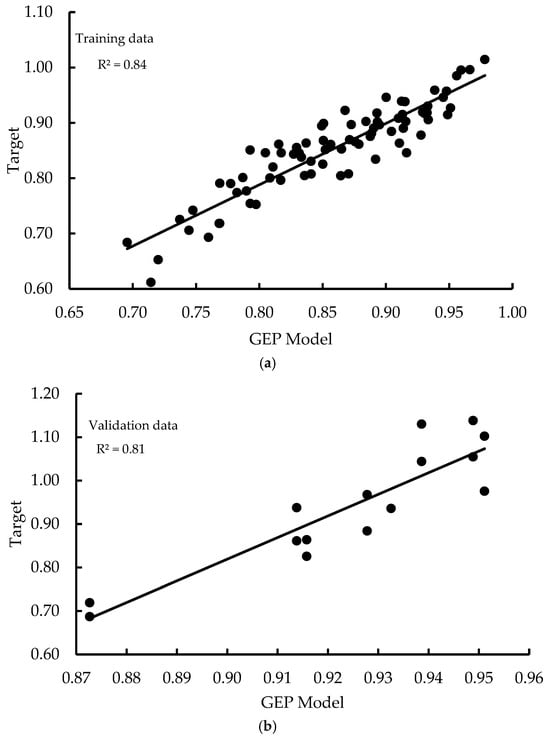

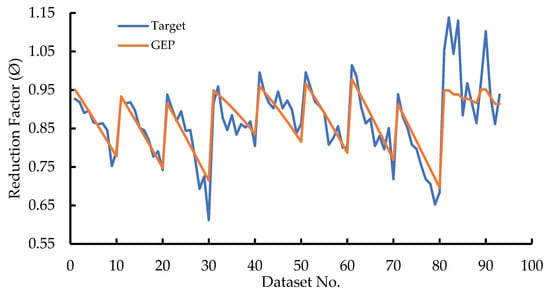

The proposed GEP model demonstrated strong agreement between experimental observations and predicted responses. Specifically, R2 values (Equation (3)) ranged from 0.81 to 0.84, while the MAE (Equation (4)) varied between 0.03 and 0.09. The RMSE (Equation (5)) was found to lie between 0.03 and 0.11, with RAE (Equation (6)) and RRSE (Equation (7)) values ranging from 0.42 to 0.86 and 0.42 to 0.85, respectively. These results indicate that the developed model possesses satisfactory predictive accuracy and generalisation capability. A summary of the statistical performance indicators for both the training and validation datasets is provided in Table 11. The relationships between predicted and experimental CCS failure loads for the training and validation datasets are illustrated in Figure 15 and Figure 16, respectively, demonstrating strong correlations and limited scatter. The corresponding reduction factors derived from the GEP model are presented in Table A3.

Table 11.

R2 and errors of training and validation of proposed model.

Figure 15.

Scatter plot for model in (a) training and (b) validation phase.

Figure 16.

Curve fitting of all data in model.

4.5. Parametric Study

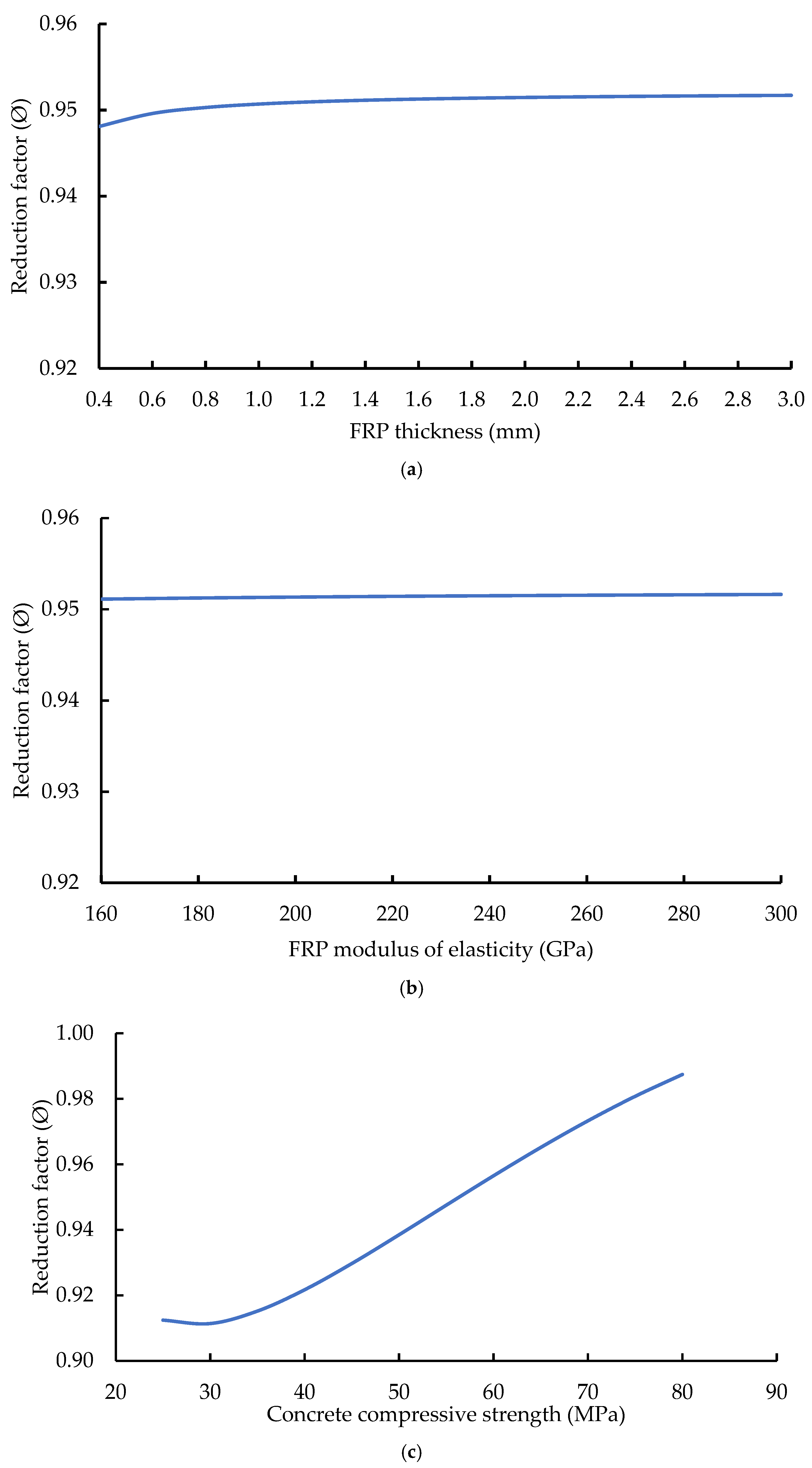

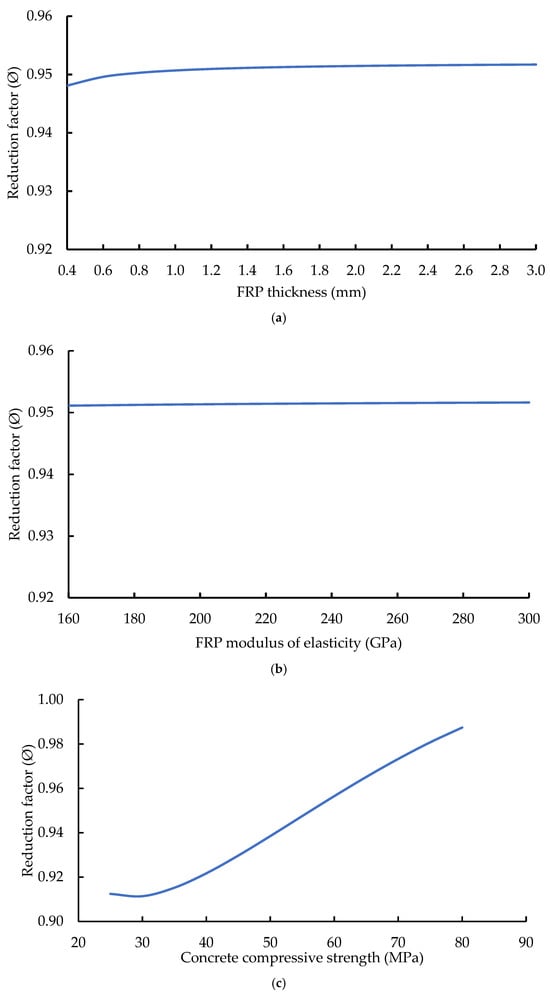

To facilitate interpretation of the proposed model, the effect of each input parameter on the predicted reduction factor was examined individually. Accordingly, a parametric analysis was conducted in which one input variable was varied at a time, while all remaining parameters were held constant. For each variable under consideration, an appropriate range was investigated to evaluate its influence on the predicted reduction factor.

A set of reference input values was adopted for the parametric evaluation of the GEP model. These reference values were selected as follows: FRP elastic modulus MPa, FRP thickness mm, concrete cylinder compressive strength MPa, and degree of curvature mm/m. The GEP model was originally calibrated using a dataset spanning the parameter limits summarised in Table 10, where varied between 165,000 and 235,000 MPa, between 0.337 and 1.4 mm, between 25 and 57 MPa, and between 5 and 50 mm/m.

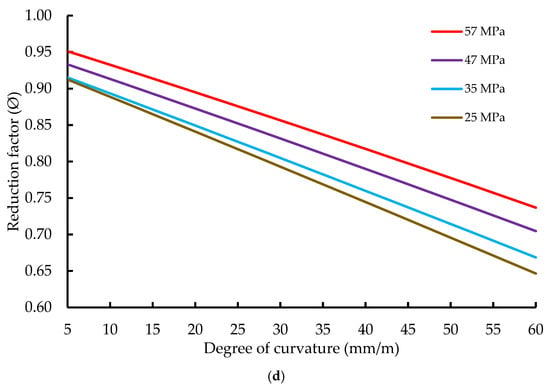

The parametric analysis indicated that the relationships between the input variables and the reduction factor exhibit consistent and predictable linear or nonlinear trends, as illustrated in Figure 17. This behaviour suggests that the proposed model may remain applicable for parameter values extending beyond those used during calibration. Consequently, the parametric study ranges were expanded to include values between 160,000 and 300,000 MPa, between 0.4 and 3.0 mm, between 25 and 80 MPa, and between 4 and 60 mm/m.

Figure 17.

Parametric study; (a) FRP thickness tf, (b) FRP modulus of elasticity Ef, (c) Concrete cylinder compressive strength f’c, (d) Degree of curvature Cd.

The results demonstrate that both FRP thickness and elastic modulus exhibit nonlinear relationships with the reduction factor, as shown in Figure 17a,b. In particular, a modest nonlinear increase in the reduction factor is observed as the FRP thickness increases from 0.4 to 0.6 mm. In contrast, the reduction factor remains relatively constant and exceeds 0.95 across the investigated range of FRP elastic modulus from 160,000 to 300,000 MPa. The influence of concrete compressive strength on the reduction factor, shown in Figure 17c, reveals an overall increasing trend, with slight nonlinearity evident between 25 and 30 MPa, followed by an approximately linear increase at higher strength levels.

The relationship between degree of curvature and reduction factor is identified as linear and inversely proportional, with the reduction factor decreasing as curvature increases, as illustrated in Figure 17d. In addition, parallel trend lines corresponding to different concrete strength levels are observed, indicating that lower concrete strengths are associated with reduced reduction factor values across the examined curvature range.

4.6. Worked Example

The example presented below is included to illustrate the procedure for applying the proposed model to evaluate the reduction factor used in estimating the flexural capacity of reinforced concrete beams with curved soffits that are externally strengthened using CFRP. Consider a rectangular reinforced concrete beam intended for flexural strengthening with CFRP, possessing the following characteristics: concrete compressive strength MPa, FRP thickness mm, FRP modulus of elasticity MPa and soffit degree of curvature mm/m.

Solution for determination of reduction factor:

5. Conclusions

This study has presented the outcomes of a two-dimensional, non-linear finite element investigation of reinforced concrete (RC) beams with curved soffits that were externally strengthened using CFRP laminates and CFRP sheets. The numerical models were first calibrated using available experimental data, and the accuracy of the calibrated simulations was subsequently validated against experimental results with respect to peak load capacity, governing failure mode, and the maximum CFRP strain attained at failure. Furthermore, two parametric investigations were performed to examine the effects of (i) the degree of soffit curvature over a range of 0–50 mm/m and (ii) four levels of concrete compressive strength, namely 25 MPa, 35 MPa, 48 MPa, and 57 MPa.

In addition, a genetic expression programming (GEP)-based predictive model was developed and evaluated to estimate the reduction in flexural capacity of concavely curved soffit RC beams strengthened externally with CFRP. A comprehensive experimental and analytical database was assembled for the purposes of model development and validation. The input dataset comprised four variables that were identified as the primary factors governing flexural capacity reduction in curved soffit RC beams, namely the concrete cylinder compressive strength, FRP thickness, FRP modulus of elasticity, and the degree of soffit curvature. The findings indicate that the proposed GEP formulation can be effectively applied as an efficient predictive tool for assessing the reduction in flexural capacity of concavely curved soffit RC beams strengthened externally with CFRP. The key outcomes of this investigation are summarised as follows:

The two-dimensional, non-linear finite-element (FE) models were capable of reproducing the experimentally measured load–mid-span-displacement response of the tested beams, capturing the response in terms of stiffness, the peak (maximum) load, and the post-peak loss of load down to the original concrete capacity. For the calibrated FE simulations, the maximum loads were predicted to within less than 10% of the corresponding experimental maximum loads. In addition, the crack patterns and the deformed shapes produced by the 2D models pointed to intermediate-span, crack-triggered CFRP de-bonding as the governing failure mechanism; notably, this matched the failure mode observed in the experiments.

A parametric study focusing on the degree of curvature showed that both the load-carrying capacity and the associated maximum CFRP strain exhibited a linear reduction with linear increases in the degree of soffit curvature, and this linear decrease occurred regardless of the strengthening configuration (i.e., FRP laminate or FRP sheet). Comparable trends/correspondences were also evident in the experimental results. A database was then assembled containing 95 experimental tests together with FEA models for concavely curved reinforced-concrete beams strengthened externally with FRP in flexure. This dataset was used for training and validating a gene expression programming (GEP) model, which produced R2 values spanning 0.63–0.84 and also delivered the lowest mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), relative absolute error (RAE), and root relative squared error (RRSE).

To obtain the final GEP formulation, more than 1000 GEP runs were executed while varying combinations of the number of genes (3–9 sub-ETs), head sizes (3–9), the number of chromosomes (20–35), and the linking functions (multiplication, addition, division, and subtraction). Moreover, for each parameter set, more than 10 iterations were investigated. Parametric studies were subsequently undertaken, and the effect of each input parameter within the proposed expression on the reduction factor was reported and discussed.

Overall, increasing FRP thickness and increasing the FRP modulus of elasticity led to a linear rise in the reduction factor up to 0.95, whereas any further increase beyond that point maintained the reduction factor at a constant value of 0.95. Increasing the concrete compressive strength likewise produced a linear increase in the reduction factor for concrete strengths exceeding 30 MPa. By contrast, increasing the degree of curvature from 4 mm/m to 60 mm/m (0.5–2%) resulted in a linear downward trend in the capacity reduction factor.

Author Contributions

K.A.-G.: Writing, experiment and data curation; R.K.: Conceptualization, supervision, writing and editing; R.A.-M.: Conceptualization, supervision, reviewing/editing; N.O.: supervision, reviewing/editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation for the joint scholarship funding provided by the Iraqi Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research and Swinburne University of Technology. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the technical support provided by the staff of the Smart Structures Laboratory at Swinburne University of Technology. Furthermore, the authors extend their appreciation to Master Builders for supplying the FRP systems and epoxy materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary of peak loads and CFRP strain values at mid-span section.

Table A1.

Summary of peak loads and CFRP strain values at mid-span section.

| Beam ID | Concrete Strength (MPa) | CFRP form | Degree of Curvature (mm/m) | (mm) | (mm) | Peak Load (kN) | Maximum CFRP Strain (μɛ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FE-0-S-57 | 57 | Sheet | 0 | 0.337 | 100 | 101.00 | 10,310 |

| FE-5-S-57 | 57 | Sheet | 5 | 0.337 | 100 | 98.22 | 9430 |

| FE-10-S-57 | 57 | Sheet | 10 | 0.337 | 100 | 99.68 | 9886 |

| FE-15-S-57 | 57 | Sheet | 15 | 0.337 | 100 | 96.99 | 9050 |

| FE-20-S-57 | 57 | Sheet | 20 | 0.337 | 100 | 95.92 | 8720 |

| FE-25-S-57 | 57 | Sheet | 25 | 0.337 | 100 | 97.21 | 9120 |

| FE-30-S-57 | 57 | Sheet | 30 | 0.337 | 100 | 95.54 | 8600 |

| FE-35-S-57 | 57 | Sheet | 35 | 0.337 | 100 | 96.43 | 8879 |

| FE-40-S-57 | 57 | Sheet | 40 | 0.337 | 100 | 96.15 | 8790 |

| FE-45-S-57 | 57 | Sheet | 45 | 0.337 | 100 | 96.65 | 8950 |

| FE-50-S-57 | 57 | Sheet | 50 | 0.337 | 100 | 94.54 | 8295 |

| FE-0-S-48 | 48 | Sheet | 0 | 0.337 | 100 | 94.05 | 8510 |

| FE-5-S-48 | 48 | Sheet | 5 | 0.337 | 100 | 93.92 | 8470 |

| FE-10-S-48 | 48 | Sheet | 10 | 0.337 | 100 | 92.64 | 8050 |

| FE-15-S-48 | 48 | Sheet | 15 | 0.337 | 100 | 91.83 | 7800 |

| FE-20-S-48 | 48 | Sheet | 20 | 0.337 | 100 | 91.46 | 7680 |

| FE-25-S-48 | 48 | Sheet | 25 | 0.337 | 100 | 92.63 | 8050 |

| FE-30-S-48 | 48 | Sheet | 30 | 0.337 | 100 | 91.50 | 7680 |

| FE-35-S-48 | 48 | Sheet | 35 | 0.337 | 100 | 92.01 | 7850 |

| FE-40-S-48 | 48 | Sheet | 40 | 0.337 | 100 | 91.37 | 7650 |

| FE-45-S-48 | 48 | Sheet | 45 | 0.337 | 100 | 89.72 | 7130 |

| FE-50-S-48 | 48 | Sheet | 50 | 0.337 | 100 | 90.39 | 7330 |

| FE-0-S-35 | 35 | Sheet | 0 | 0.337 | 100 | 89.69 | 7972 |

| FE-5-S-35 | 35 | Sheet | 5 | 0.337 | 100 | 89.59 | 7940 |

| FE-10-S-35 | 35 | Sheet | 10 | 0.337 | 100 | 88.74 | 7630 |

| FE-15-S-35 | 35 | Sheet | 15 | 0.337 | 100 | 87.93 | 7330 |

| FE-20-S-35 | 35 | Sheet | 20 | 0.337 | 100 | 87.68 | 7240 |

| FE-25-S-35 | 35 | Sheet | 25 | 0.337 | 100 | 87.27 | 7100 |

| FE-30-S-35 | 35 | Sheet | 30 | 0.337 | 100 | 85.42 | 6440 |

| FE-35-S-35 | 35 | Sheet | 35 | 0.337 | 100 | 85.80 | 6580 |

| FE-40-S-35 | 35 | Sheet | 40 | 0.337 | 100 | 86.51 | 6820 |

| FE-45-S-35 | 35 | Sheet | 45 | 0.337 | 100 | 85.25 | 6380 |

| FE-50-S-35 | 35 | Sheet | 50 | 0.337 | 100 | 85.28 | 6386 |

| FE-0-S-25 | 25 | Sheet | 0 | 0.337 | 100 | 83.18 | 7310 |

| FE-5-S-25 | 25 | Sheet | 5 | 0.337 | 100 | 83.43 | 7415 |

| FE-10-S-25 | 25 | Sheet | 10 | 0.337 | 100 | 82.89 | 7200 |

| FE-15-S-25 | 25 | Sheet | 15 | 0.337 | 100 | 81.53 | 6620 |

| FE-20-S-25 | 25 | Sheet | 20 | 0.337 | 100 | 80.79 | 6310 |

| FE-25-S-25 | 25 | Sheet | 25 | 0.337 | 100 | 81.02 | 6400 |

| FE-30-S-25 | 25 | Sheet | 30 | 0.337 | 100 | 79.77 | 5880 |

| FE-35-S-25 | 25 | Sheet | 35 | 0.337 | 100 | 80.23 | 6070 |

| FE-40-S-25 | 25 | Sheet | 40 | 0.337 | 100 | 79.66 | 5820 |

| FE-45-S-25 | 25 | Sheet | 45 | 0.337 | 100 | 80.60 | 6220 |

| FE-50-S-25 | 25 | Sheet | 50 | 0.337 | 100 | 78.30 | 5250 |

| FE-0-L-57 | 57 | Laminate | 0 | 1.4 | 50 | 105.80 | 8200 |

| FE-5-L-57 | 57 | Laminate | 5 | 1.4 | 50 | 103.10 | 7600 |

| FE-10-L-57 | 57 | Laminate | 10 | 1.4 | 50 | 102.80 | 7530 |

| FE-15-L-57 | 57 | Laminate | 15 | 1.4 | 50 | 101.70 | 7300 |

| FE-20-L-57 | 57 | Laminate | 20 | 1.4 | 50 | 101.90 | 7350 |

| FE-25-L-57 | 57 | Laminate | 25 | 1.4 | 50 | 100.80 | 7100 |

| FE-30-L-57 | 57 | Laminate | 30 | 1.4 | 50 | 100.60 | 7060 |

| FE-35-L-57 | 57 | Laminate | 35 | 1.4 | 50 | 100.70 | 7080 |

| FE-40-L-57 | 57 | Laminate | 40 | 1.4 | 50 | 100.00 | 6935 |

| FE-45-L-57 | 57 | Laminate | 45 | 1.4 | 50 | 96.30 | 6170 |

| FE-50-L-57 | 57 | Laminate | 50 | 1.4 | 50 | 97.85 | 6480 |

| FE-0-L-48 | 48 | Laminate | 0 | 1.4 | 50 | 99.88 | 7170 |

| FE-5-L-48 | 48 | Laminate | 5 | 1.4 | 50 | 97.59 | 6670 |

| FE-10-L-48 | 48 | Laminate | 10 | 1.4 | 50 | 97.12 | 6560 |

| FE-15-L-48 | 48 | Laminate | 15 | 1.4 | 50 | 97.20 | 6580 |

| FE-20-L-48 | 48 | Laminate | 20 | 1.4 | 50 | 96.50 | 6430 |

| FE-25-L-48 | 48 | Laminate | 25 | 1.4 | 50 | 95.00 | 6105 |

| FE-30-L-48 | 48 | Laminate | 30 | 1.4 | 50 | 94.79 | 6060 |

| FE-35-L-48 | 48 | Laminate | 35 | 1.4 | 50 | 93.95 | 5880 |

| FE-40-L-48 | 48 | Laminate | 40 | 1.4 | 50 | 92.49 | 5570 |

| FE-45-L-48 | 48 | Laminate | 45 | 1.4 | 50 | 92.97 | 5670 |

| FE-50-L-48 | 48 | Laminate | 50 | 1.4 | 50 | 91.33 | 5320 |

| FE-0-L-35 | 35 | Laminate | 0 | 1.4 | 50 | 92.89 | 6177 |

| FE-5-L-35 | 35 | Laminate | 5 | 1.4 | 50 | 91.31 | 5795 |

| FE-10-L-35 | 35 | Laminate | 10 | 1.4 | 50 | 90.36 | 5570 |

| FE-15-L-35 | 35 | Laminate | 15 | 1.4 | 50 | 89.52 | 5370 |

| FE-20-L-35 | 35 | Laminate | 20 | 1.4 | 50 | 90.17 | 5525 |

| FE-25-L-35 | 35 | Laminate | 25 | 1.4 | 50 | 88.82 | 5210 |

| FE-30-L-35 | 35 | Laminate | 30 | 1.4 | 50 | 88.90 | 5225 |

| FE-35-L-35 | 35 | Laminate | 35 | 1.4 | 50 | 86.98 | 4780 |

| FE-40-L-35 | 35 | Laminate | 40 | 1.4 | 50 | 84.75 | 4281 |

| FE-45-L-35 | 35 | Laminate | 45 | 1.4 | 50 | 85.64 | 4480 |

| FE-50-L-35 | 35 | Laminate | 50 | 1.4 | 50 | 82.44 | 3779 |

| FE-0-L-25 | 25 | Laminate | 0 | 1.4 | 50 | 88.51 | 6390 |

| FE-5-L-25 | 25 | Laminate | 5 | 1.4 | 50 | 87.17 | 6000 |

| FE-10-L-25 | 25 | Laminate | 10 | 1.4 | 50 | 85.90 | 5630 |

| FE-15-L-25 | 25 | Laminate | 15 | 1.4 | 50 | 85.27 | 5450 |

| FE-20-L-25 | 25 | Laminate | 20 | 1.4 | 50 | 84.28 | 5160 |

| FE-25-L-25 | 25 | Laminate | 25 | 1.4 | 50 | 84.04 | 5090 |

| FE-30-L-25 | 25 | Laminate | 30 | 1.4 | 50 | 83.11 | 4820 |

| FE-35-L-25 | 25 | Laminate | 35 | 1.4 | 50 | 82.31 | 4590 |

| FE-40-L-25 | 25 | Laminate | 40 | 1.4 | 50 | 82.01 | 4510 |

| FE-45-L-25 | 25 | Laminate | 45 | 1.4 | 50 | 80.79 | 4170 |

| FE-50-L-25 | 25 | Laminate | 50 | 1.4 | 50 | 81.59 | 4370 |

Table A2.

Database of curved soffit RC beams externally strengthened with FRP.

Table A2.

Database of curved soffit RC beams externally strengthened with FRP.

| Beam ID | (mm) | (MPa) | f′c (MPa) | (mm/m) | ∅ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FE-5L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 5 | 0.927 |

| FE-10L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 10 | 0.918 |

| FE-15L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 15 | 0.890 |

| FE-20L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 20 | 0.896 |

| FE-25L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 25 | 0.866 |

| FE-30L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 30 | 0.861 |

| FE-35L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 35 | 0.863 |

| FE-40L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 40 | 0.846 |

| FE-45L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 45 | 0.752 |

| FE-50L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 50 | 0.790 |

| FE-5L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 5 | 0.930 |

| FE-10L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 10 | 0.915 |

| FE-15L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 15 | 0.918 |

| FE-20L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 20 | 0.897 |

| FE-25L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 25 | 0.851 |

| FE-30L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 30 | 0.845 |

| FE-35L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 35 | 0.820 |

| FE-40L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 40 | 0.777 |

| FE-45L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 45 | 0.791 |

| FE-50L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 50 | 0.742 |

| FE-5L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 5 | 0.938 |

| FE-10L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 10 | 0.902 |

| FE-15L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 15 | 0.869 |

| FE-20L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 20 | 0.894 |

| FE-25L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 25 | 0.843 |

| FE-30L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 30 | 0.846 |

| FE-35L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 35 | 0.774 |

| FE-40L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 40 | 0.693 |

| FE-45L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 45 | 0.725 |

| FE-50L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 50 | 0.612 |

| FE-5S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 5 | 0.915 |

| FE-10S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 10 | 0.959 |

| FE-15S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 15 | 0.878 |

| FE-20S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 20 | 0.846 |

| FE-25S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 25 | 0.885 |

| FE-30S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 30 | 0.834 |

| FE-35S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 35 | 0.861 |

| FE-40S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 40 | 0.853 |

| FE-45S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 45 | 0.868 |

| FE-50S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 50 | 0.805 |

| FE-5S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 5 | 0.995 |

| FE-10S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 10 | 0.946 |

| FE-15S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 15 | 0.917 |

| FE-20S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 20 | 0.902 |

| FE-25S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 25 | 0.946 |

| FE-30S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 30 | 0.902 |

| FE-35S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 35 | 0.922 |

| FE-40S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 40 | 0.899 |

| FE-45S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 45 | 0.838 |

| FE-50S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 50 | 0.861 |

| FE-5S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 5 | 0.996 |

| FE-10S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 10 | 0.957 |

| FE-15S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 15 | 0.919 |

| FE-20S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 20 | 0.908 |

| FE-25S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 25 | 0.891 |

| FE-30S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 30 | 0.808 |

| FE-35S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 35 | 0.825 |

| FE-40S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 40 | 0.855 |

| FE-45S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 45 | 0.800 |

| FE-50S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 50 | 0.801 |

| FE-5S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 5 | 1.014 |

| FE-10S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 10 | 0.985 |

| FE-15S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 15 | 0.906 |

| FE-20S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 20 | 0.863 |

| FE-25S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 25 | 0.876 |

| FE-30S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 30 | 0.804 |

| FE-35S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 35 | 0.830 |

| FE-40S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 40 | 0.796 |

| FE-45S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 45 | 0.851 |

| FE-50S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 50 | 0.718 |

| FE-5L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 5 | 0.939 |

| FE-10L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 10 | 0.881 |

| FE-15L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 15 | 0.853 |

| FE-20L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 20 | 0.808 |

| FE-25L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 25 | 0.797 |

| FE-30L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 30 | 0.754 |

| FE-35L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 35 | 0.718 |

| FE-40L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 40 | 0.706 |

| FE-45L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 45 | 0.653 |

| FE-50L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 50 | 0.684 |

| * XP-5S-57-1 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 5 | 1.055 |

| * XP-5S-57-2 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 5 | 1.138 |

| * XP-10S-57-1 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 10 | 1.044 |

| * XP-10S-57-2 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 10 | 1.130 |

| * XP-15S-57-1 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 15 | 0.884 |

| *XP-15S-57-2 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 15 | 0.968 |

| * XP-20S-47-1 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 20 | 0.864 |

| * XP-20S-47-2 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 20 | 0.826 |

| * XP-5L-57-1 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 5 | 0.976 |

| * XP-5L-57-2 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 5 | 1.102 |

| * XP-10L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 10 | 0.936 |

| * XP-15L-57-1 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 15 | 0.861 |

| * XP-15L-57-2 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 15 | 0.938 |

| * XP-20L-47-1 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 20 | 0.687 |

| * XP-20L-47-2 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 20 | 0.719 |

* Results reported by Al-Ghrery et al. (2022) [9].

Table A3.

Summary of predicted vs. experimental reduction factors.

Table A3.

Summary of predicted vs. experimental reduction factors.

| Beam ID | (mm) | (MPa) | f′c (MPa) | (mm/m) | ∅ | ∅ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FE-5L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 5 | 0.93 | 0.95 |

| FE-10L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 10 | 0.92 | 0.93 |

| FE-15L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 15 | 0.89 | 0.91 |

| FE-20L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 20 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| FE-25L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 25 | 0.87 | 0.88 |

| FE-30L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 30 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| FE-35L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 35 | 0.86 | 0.84 |

| FE-40L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 40 | 0.85 | 0.82 |

| FE-45L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 45 | 0.75 | 0.80 |

| FE-50L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 50 | 0.79 | 0.78 |

| FE-5L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 5 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| FE-10L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 10 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| FE-15L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 15 | 0.92 | 0.89 |

| FE-20L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 20 | 0.90 | 0.87 |

| FE-25L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 25 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| FE-30L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 30 | 0.85 | 0.83 |

| FE-35L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 35 | 0.82 | 0.81 |

| FE-40L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 40 | 0.78 | 0.79 |

| FE-45L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 45 | 0.79 | 0.77 |

| FE-50L-47 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 50 | 0.74 | 0.75 |

| FE-5L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 5 | 0.94 | 0.92 |

| FE-10L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 10 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| FE-15L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 15 | 0.87 | 0.87 |

| FE-20L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 20 | 0.89 | 0.85 |

| FE-25L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 25 | 0.84 | 0.83 |

| FE-30L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 30 | 0.85 | 0.80 |

| FE-35L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 35 | 0.77 | 0.78 |

| FE-40L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 40 | 0.69 | 0.76 |

| FE-45L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 45 | 0.73 | 0.74 |

| FE-50L-35 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 35 | 50 | 0.61 | 0.71 |

| FE-5S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 5 | 0.91 | 0.95 |

| FE-10S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 10 | 0.96 | 0.94 |

| FE-15S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 15 | 0.88 | 0.93 |

| FE-20S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 20 | 0.85 | 0.92 |

| FE-25S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 25 | 0.88 | 0.90 |

| FE-30S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 30 | 0.83 | 0.89 |

| FE-35S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 35 | 0.86 | 0.88 |

| FE-40S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 40 | 0.85 | 0.86 |

| FE-45S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 45 | 0.87 | 0.85 |

| FE-50S-57 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 50 | 0.80 | 0.84 |

| FE-5S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 5 | 1.00 | 0.96 |

| FE-10S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 10 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| FE-15S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 15 | 0.92 | 0.93 |

| FE-20S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 20 | 0.90 | 0.92 |

| FE-25S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 25 | 0.95 | 0.90 |

| FE-30S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 30 | 0.90 | 0.88 |

| FE-35S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 35 | 0.92 | 0.87 |

| FE-40S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 40 | 0.90 | 0.85 |

| FE-45S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 45 | 0.84 | 0.83 |

| FE-50S-47 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 50 | 0.86 | 0.82 |

| FE-5S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 5 | 1.00 | 0.97 |

| FE-10S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 10 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| FE-15S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 15 | 0.92 | 0.93 |

| FE-20S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 20 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| FE-25S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 25 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| FE-30S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 30 | 0.81 | 0.87 |

| FE-35S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 35 | 0.83 | 0.85 |

| FE-40S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 40 | 0.86 | 0.83 |

| FE-45S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 45 | 0.80 | 0.81 |

| FE-50S-35 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 35 | 50 | 0.80 | 0.79 |

| FE-5S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 5 | 1.01 | 0.98 |

| FE-10S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 10 | 0.98 | 0.96 |

| FE-15S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 15 | 0.91 | 0.93 |

| FE-20S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 20 | 0.86 | 0.91 |

| FE-25S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 25 | 0.88 | 0.89 |

| FE-30S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 30 | 0.80 | 0.86 |

| FE-35S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 35 | 0.83 | 0.84 |

| FE-40S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 40 | 0.80 | 0.82 |

| FE-45S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 45 | 0.85 | 0.79 |

| FE-50S-25 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 25 | 50 | 0.72 | 0.77 |

| FE-5L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 5 | 0.94 | 0.91 |

| FE-10L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 10 | 0.88 | 0.89 |

| FE-15L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 15 | 0.85 | 0.86 |

| FE-20L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 20 | 0.81 | 0.84 |

| FE-25L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 25 | 0.80 | 0.82 |

| FE-30L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 30 | 0.75 | 0.79 |

| FE-35L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 35 | 0.72 | 0.77 |

| FE-40L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 40 | 0.71 | 0.74 |

| FE-45L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 45 | 0.65 | 0.72 |

| FE-50L-25 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 25 | 50 | 0.68 | 0.70 |

| XP-5S-57-1 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 5 | 1.06 | 0.95 |

| XP-5S-57-2 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 5 | 1.14 | 0.95 |

| XP-10S-57-1 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 10 | 1.04 | 0.94 |

| XP-10S-57-2 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 10 | 1.13 | 0.94 |

| XP-15S-57-1 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 15 | 0.88 | 0.93 |

| XP-15S-57-2 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 57 | 15 | 0.97 | 0.93 |

| XP-20S-47-1 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 20 | 0.86 | 0.92 |

| XP-20S-47-2 | 0.337 | 235,000 | 47 | 20 | 0.83 | 0.92 |

| XP-5L-57-1 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 5 | 0.98 | 0.95 |

| XP-5L-57-2 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 5 | 1.10 | 0.95 |

| XP-10L-57 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 10 | 0.94 | 0.93 |

| XP-15L-57-1 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 15 | 0.86 | 0.91 |

| XP-15L-57-2 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 57 | 15 | 0.94 | 0.91 |

| XP-15L-47-1 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 20 | 0.69 | 0.87 |

| XP-15L-47-2 | 1.4 | 165,000 | 47 | 20 | 0.72 | 0.87 |

References

- AS 5100.8; Rehabilitation and Strengthening of Existing Bridges. Standards Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2017.

- Concrete Society Working Party. Design Guidance for Structures Using Fibre Reinforced Polymers; (Technical Report No. 55); The Concrete Society: Surrey, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Eshwar, N.; Ibell, T.; Nanni, A. Effectiveness of CFRP strengthening on curved soffit RC beams. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2005, 8, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, D.; Denton, S.; Nanni, A.; Ibell, T. Effectiveness of FRP plate strengthening on curved soffits. In Proceedings of the FRPRCS-6: Fibre-Reinforced Polymer Reinforcement for Concrete Structures, Singapore, 8–10 July 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello, M.; Galati, N.; La Tegola, A. Bond analysis of curved structural concrete elements strengthened using FRP materials. In Proceedings of the FRPRCS-5: Fibre-Reinforced Plastics for Reinforced Concrete Structures, Cambridge, UK, 16–18 July 2001; Volume 1, pp. 399–408. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghrery, K.; Kalfat, R.; Al-Mahaidi, R.; Oukaili, N.; Al-Mosawe, A. Prediction of concrete cover separation in reinforced concrete beams strengthened with FRP. J. Compos. Constr. 2021, 25, 04021022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghrery, K.; Al-Mahaidi, R.; Kalfat, R.; Oukaili, N.; Al-Mosawe, A. Experimental investigation of curved-soffit RC bridge girders strengthened in flexure using CFRP composites. J. Bridge Eng. 2021, 26, 04021009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI Committee 440. Design and Construction of Externally Bonded Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) Systems for Strengthening Concrete Structures—Guide; ACI 440.2; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghrery, K.; Al-Mahaidi, R.; Kalfat, R.; Oukaili, N.; Al-Mosawe, A. Externally bonded CFRP for flexural strengthening of RC beams with different levels of soffit curvature. J. Compos. Constr. 2022, 26, 04021062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saud, D.I.; Habra, I.S.I. Behavior of lightweight reinforced concrete concavely-curved soffit beams strengthened with CFRP. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2025, 21, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukozturk, O. Nonlinear analysis of reinforced concrete structures. Comput. Struct. 1977, 7, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camata, G.; Spacone, E.; Zarnic, R. Experimental and nonlinear finite element studies of RC beams strengthened with FRP plates. Compos. Part B Eng. 2007, 38, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Teng, J.G.; Chen, J.F. Finite-element modeling of intermediate crack debonding in FRP-plated RC beams. J. Compos. Constr. 2011, 15, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godat, A.; Neale, K.; Labossière, P. Numerical modeling of FRP shear-strengthened reinforced concrete beams. J. Compos. Constr. 2007, 11, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, F.; Bucci, F. Analysis of repaired reinforced concrete structures. J. Struct. Eng. 1999, 125, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouelleil, A.; Rasheed, H.A. Calibrating a new constitutive tension model to extract a simplified nonlinear sectional analysis of reinforced concrete beams. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godat, A.; Labossière, P.; Neale, K.W.; Chaallal, O. Behavior of RC members strengthened in shear with externally bonded FRP: Assessment of models and finite element simulation approaches. Comput. Struct. 2012, 92–93, 269–282. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, J.G.; Zhang, S.S.; Dai, J.G.; Chen, J.F. Three-dimensional meso-scale finite element modeling of bonded joints between a near-surface mounted FRP strip and concrete. Comput. Struct. 2013, 117, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI–ASCE Committee 447. Report on the Modeling Techniques Used in Finite Element Simulations of Concrete Structures Strengthened Using Fiber-Reinforced Polymers; ACI 447.1; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]