Abstract

This study systematically investigates the effects of varying Cl−/ concentration ratios in saline solutions on the drying shrinkage, mechanical properties, and microstructure evolution of a cementitious system under simulated saline–alkali conditions. The underlying influence mechanism is elucidated via TG-DTG, XRD, and SEM analyses. Experimental results indicate that increasing the Cl−/ concentration ratio of the mixing water from 0.2 to 2.5 leads to a significant rise in early-age drying shrinkage, with an increase of approximately 19%, while it simultaneously enhances the early-age compressive strength of the cementitious matrix, achieving increases of approximately 13% at 1 d, 14% at 3 d, 14% at 7 d, and stabilizing at about 7% by 28 d. Microscopic characterizations reveal that as the Cl−/ concentration ratio increases, the ettringite content decreases, the contents of Friedel’s salt and calcium hydroxide increase, and the cementitious microstructure accordingly becomes denser. This work aims to provide theoretical and experimental references for the durability design and performance optimization of cement-based materials in saline–alkali regions.

1. Introduction

The Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region is located in the hinterland of the Eurasian continent and is endowed with abundant mineral and energy resources, forming a highly favorable natural resource base. As a core strategic hub of the Silk Road Economic Belt, Xinjiang occupies an irreplaceable and pivotal position in China’s Western Development strategy and regional economic integration. However, the region is characterized by an extremely arid climate and a severe shortage of freshwater resources. In most areas, the annual precipitation is less than 200 mm [1], whereas annual evaporation far exceeds precipitation, reaching several to dozens of times higher in certain regions [2]. This pronounced hydrothermal imbalance not only accelerates soil salinization but also leads to the formation of a highly saline and strongly corrosive environment dominated by Cl− and ions [3]. Under such harsh conditions, cement-based materials are subjected to severe chemical corrosion, thereby imposing stringent durability requirements on modern cementitious structures used in infrastructure construction [4,5]. Meanwhile, concrete production typically requires large quantities of water for mixing [6]. Owing to the combined constraints of a saline–alkaline environment and acute freshwater scarcity, local infrastructure projects are often compelled to use saline–alkaline water rich in deleterious ions as mixing water. The use of such water significantly disrupts the normal early-age hydration processes of cementitious systems, further increasing the risk of performance degradation in cement-based materials. Consequently, this poses a serious threat to the long-term stability and service performance of regional infrastructure and restricts the sustainable development of the core area of the Silk Road Economic Belt. Therefore, systematically elucidating the intrinsic mechanisms governing the performance deterioration of cement-based materials under the specific saline–alkaline conditions of southern Xin-jiang, and establishing a scientifically robust durability assurance framework, have become critical technical challenges that must be urgently addressed in contemporary civil engineering. This research is characterized by strong engineering urgency and significant practical relevance.

The durability deterioration mechanisms of cementitious materials have long been a major research focus in the global civil engineering community. Among these mechanisms, shrinkage-induced cracking is widely recognized as the primary triggering factor [7,8,9]. Mehta reported that the degradation of durability in cement-based materials is mainly driven by the initiation and propagation of internal microcracks, approximately 80% of which are non-load-induced and are primarily activated by the combined effects of thermal shrinkage and drying shrinkage [10]. To identify the key factors governing shrinkage and cracking behavior, Burrows [11] conducted a systematic analysis of extensive experimental data and demonstrated that alkali content—mainly present in the form of saline–alkaline ions—is the dominant factor influencing shrinkage and cracking in cementitious systems, while the content of tricalcium aluminate (C3A) represents the third most influential parameter. Focusing on the specific effects of saline–alkaline components in mixing water, previous studies have shown that the incorporation of saline–alkaline constituents significantly increase shrinkage deformation and early-age cracking susceptibility of cement-based materials [12]. Consequently, strict control of salt content in mixing water is required to mitigate the risk of early-age cracking. Li et al. [7,13] further confirmed that saline–alkaline constituents are key contributors to both autogenous and drying shrinkage in various cement-based materials and are critical factors inducing material cracking. Consistent with these findings, He et al. [12] observed, using an elliptical ring cracking test, that increasing alkali content simultaneously elevates the shrinkage rate and cracking sensitivity of cement-based materials.

From a mechanistic perspective, salt-ion-induced early-age shrinkage is closely related to cement mineral composition, particularly the hydration behavior of the C3A phase. Alkalis can markedly accelerate C3A hydration by promoting the dissolution of aluminum-bearing phases [14,15], leading to the formation of U-phase (C3A·CaSO4·2H2O incorporating Na2SO4) and ettringite (AFt) [16,17]. This process facilitates the development and refinement of pore structure. As ions are progressively consumed, OH− ions substitute for to maintain charge balance in the pore solution, resulting in a rapid increase in solution pH. Elevated alkalinity further enhances the dissolution of silicate phases, thereby accelerating the overall hydration process of cement.

A systematic review of existing domestic and international studies indicates that, although the effects of salt ions on the performance of cement-based materials have been widely investigated, several critical gaps and limitations remain, particularly with respect to the specific engineering demands of inland saline–alkaline regions. First, most existing studies focus on seawater systems characterized by relatively stable salt composition and concentration [18,19,20]. In contrast, inland regions such as Xinjiang exhibit pronounced spatial heterogeneity in the chemical composition of saline lake water and groundwater. Based on the relative concentration ratios of the two dominant corrosive ions (Cl− and ), these environments can be classified into four typical saline–alkaline types (Table 1) [3]. Compared with seawater, inland saline–alkaline water is characterized by highly variable ionic composition, concentration levels, and coupled corrosive effects, which are strongly influenced by geographic setting, climatic conditions, and hydrological regimes. Consequently, the interaction mechanisms between inland saline–alkaline water and cement-based materials are substantially more complex than those in marine environments, rendering conclusions derived from seawater-based studies difficult to directly apply to inland saline–alkaline regions. Second, previous research has confirmed that alkali content is the primary factor governing shrinkage and cracking behavior in cementitious systems [11], and that salt-ion-induced early-age shrinkage is closely associated with the hydration behavior of the cement C3A phase [14,15,16,17]. However, most existing studies are limited to the effects of single ions on cement shrinkage performance. Systematic investigations into the coupled effects of saline–alkaline water with varying salt compositions and concentration ratios on the shrinkage behavior of cement-based materials remain scarce, and a unified under-standing of the underlying mechanisms has yet to be established. This knowledge gap significantly constrains the accurate characterization of material performance evolution under complex saline–alkaline environments. Third, existing studies predominantly examine the influence of saline–alkaline environments on cement shrinkage behavior in isolation [7,13], with relatively few investigations addressing the coupling relationship between shrinkage characteristics and mechanical properties. These limitations do not adequately meet the urgent engineering construction demands in southern Xinjiang, underscoring the pressing need for targeted and systematic re-search.

Table 1.

Classification criteria for salt composition.

Based on the above research background and identified limitations, the core motivation of this study is to fill the existing research gap regarding the early-age performance of cement-based materials under specific inland saline–alkaline environments, and to provide theoretical foundations and data support for the rational utilization of saline–alkaline water in infrastructure construction in Southern Xinjiang. Accordingly, the main research objectives of this work are defined as follows: (1) To systematically elucidate the effects of saline–alkaline water with different salt compositions on the drying shrinkage behavior and early-age mechanical properties of cement-based mate-rials; (2) To clarify the intrinsic mechanisms by which saline–alkaline water regulates the early-age performance of cement-based materials, and to establish a correlation framework linking “saline–alkaline water characteristics–microstructural evolution–macroscopic early-age performance.”

To achieve these objectives, a technical route integrating “macroscopic performance characterization–micro-mechanism analysis–engineering-oriented application” is adopted. Typical saline–alkaline water from Southern Xinjiang is selected as the re-search object, and experimental variables are designed to represent different salt compositions. Macroscopic performance tests, including drying shrinkage (1–180 d) and early-age compressive strength (1–28 d), are conducted on cement-based materials. These results are combined with X-ray diffraction (XRD) for hydration phase identification and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for microstructural observation. Through this integrated approach, the effects of saline–alkaline water on early-age performance are systematically analyzed from the perspectives of hydration product composition and microstructural evolution, thereby elucidating the intrinsic mechanisms by which salt ions regulate cement hydration processes and hydration product formation.

The outcomes of this study are expected to provide scientific evidence and technical support for the rational utilization of saline–alkaline water and the assurance of early-age performance of cement-based materials in Southern Xinjiang and other similar inland saline–alkaline regions. Ultimately, this work aims to support the safe, efficient, and sustainable advancement of major infrastructure projects in the core area of the Silk Road Economic Belt, in alignment with regional strategic development goals and the quality enhancement of engineering construction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The cement employed in this study was P·O 42.5 ordinary Portland cement (OPC) manufactured by Xinjiang Tianye Cement Co., Ltd. (Shihezi, China) and its detailed chemical composition is listed in Table 2. Sodium chloride (NaCl) and sodium sulfate (Na2SO4) used as saline–alkali sources were analytical reagent (AR) grade products supplied by Tianjin Zhiyuan Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China) with a minimum purity of 99.0% for each reagent. The reference mixing water adopted in the experiments was filtered purified water to eliminate the interference of impurity ions on the test results.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of cement.

2.2. Mix Proportion Design

The water-to-cement ratio (w/c) of the cement paste was fixed at 0.4. For the preparation of saline–alkali water, a baseline concentration of 8000 mg/L was fixed, and the Cl−/ molar concentration ratios (abbreviated as C/S hereinafter) were designed as 2.5, 1.5, 0.5, and 0.2 to simulate typical saline–alkali water environments with varying salt compositions (characterized by different Cl−/ ratios) in southern Xinjiang. Detailed mix proportions of all cement paste specimens are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mix proportion of paste.

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.3.1. Drying Shrinkage Rate

Shrinkage is a critical aspect of volume deformation in cementitious materials and may induce the initiation of cracks. It is generally classified into chemical shrinkage, autogenous shrinkage, and drying shrinkage, with drying shrinkage being the primary focus of this study. As specified in Table 3, three cement paste specimens were prepared for each mix proportion and cast into molds with dimensions of 25 mm × 25 mm × 280 mm. All specimen preparations were conducted in a controlled environment with 90% relative humidity (RH) and a temperature of 20 ± 1 °C. After the surface of the cement paste specimens had hardened, they were covered with plastic wrap to minimize moisture evaporation. Following 24 h of curing, the specimens were demolded, and their initial lengths were accurately measured using a length comparator. Subsequently, the demolded specimens were transferred to a regulated environment (50 ± 4% RH, 20 ± 3 °C) for drying shrinkage testing, with continuous monitoring and data recording performed over a period of up to 180 days.

2.3.2. Compressive Strength Test

For the compressive strength test, cubic cement paste specimens with dimensions of 20 mm × 20 mm × 20 mm were adopted. All specimens were fabricated in a controlled environment with 90% relative humidity (RH) and a temperature of 20 ± 1 °C. After molding, the specimens were transferred to a standard curing regime, where the ambient temperature was maintained at 20 ± 2 °C and RH ≥ 95%, and cured to the designated ages of 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 28 d, respectively. After reaching the preset curing ages, the specimens were retrieved and their compressive strength was immediately evaluated using a 300 kN universal testing machine. For each mix proportion and at every testing age, three replicate specimens were tested, and the reported strength value represents the average of these three measurements.

2.3.3. Microscopic Property Testing

Samples for microstructural characterization were harvested from 20 mm × 20 mm × 20 mm cubic specimens subjected to standard curing for 1 day (d). The cubic specimens were fractured, and fragments from the central region were selected and immersed in absolute ethanol to immediately terminate the hydration process.

Specifically, fragments with flat and defect-free surfaces were selected for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observation using a Zeiss EVO MA15 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), aiming to characterize the micromorphological characteristics. The remaining fragments were thoroughly ground in an agate mortar and subsequently sieved through a 75 μm standard sieve. The obtained powder samples were divided into two aliquots: one aliquot was subjected to X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis using a Bruker D8 diffractometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) for phase composition identification, with the scanning range set as 5–40° 2θ and a step size of 0.02°; the other aliquot was subjected to thermogravimetric-derivative thermogravimetric (TG-DTG) analysis to evaluate the phase compositions and thermal stability of hydration products, with the temperature range programmed from 50 °C to 1000 °C at a heating rate of 20 °C/min.

3. Results and Discussion

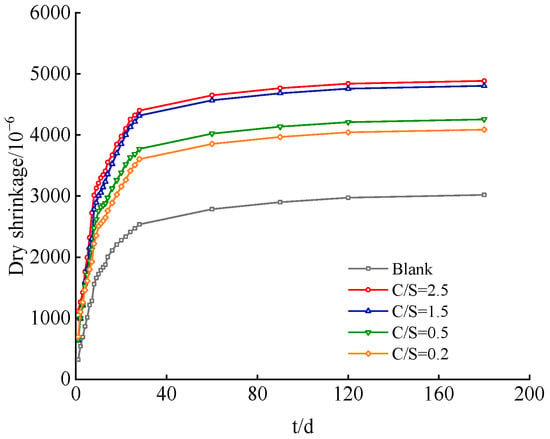

3.1. Effect of Different Salt Compositions on the Drying Shrinkage of Cement Paste

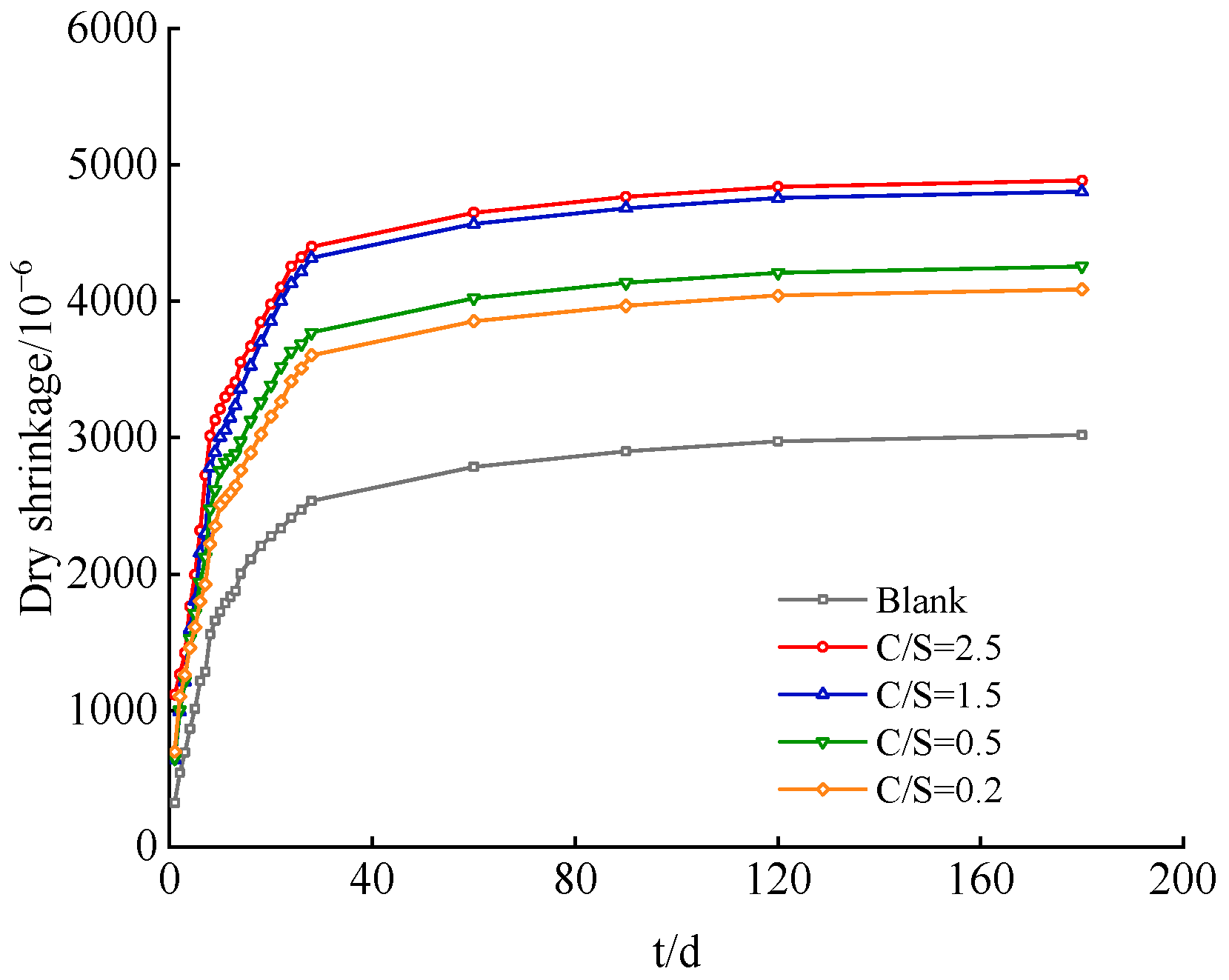

Figure 1 presents the dynamic evolution profiles of drying shrinkage for cement paste specimens under the conditions of a blank group and varied C/S ratios (i.e., Cl−/ molar ratios). The drying shrinkage behavior of all specimens follows a three-stage evolutionary pattern: rapid growth–rate deceleration–stabilization. The initial 28-day curing period corresponds to the rapid shrinkage stage, during which capillary negative pressure induced by the rapid dissipation of free water within capillary pores serves as the primary driving force for significant matrix shrinkage [21]. From day 40 to day 120, the process transitions to the shrinkage rate deceleration stage; as hydration products continuously fill the pore structure, the system porosity decreases, pore size is refined, moisture migration resistance is enhanced, and the shrinkage rate slows accordingly. After day 120, shrinkage development tends to stabilize. At this stage, the matrix microstructure is fully densified, and moisture evaporation is further reduced, thereby stabilizing the final shrinkage value [22]. Fundamentally, this evolutionary pattern reflects the coupling mechanism governing hydration–pore structure–shrinkage in cement-based materials.

Figure 1.

Drying shrinkage curves of cement paste under different salt composition groups.

From the perspective of the regulatory effect of saline–alkali water on the drying shrinkage of cement-based materials, saline–alkali water with different C/S ratios (Cl−/) significantly enhances the drying shrinkage of cement-based materials. Moreover, the experimental results clearly demonstrate a stable positive correlation between the C/S ratio and the final drying shrinkage rate, indicating that as the relative content of Cl− increases, the exacerbating effect of salt ions on the drying shrinkage rate becomes more pronounced.

The specific data are as follows: For the blank group (where no additional Cl− or was introduced into the mixing water, and only standard fresh water was used for mixing), the cement hydration process proceeded smoothly and orderly, with the pore structure gradually optimizing and evolving moderately. The final drying shrinkage rate was only 3020.71 × 10−6, which can serve as a baseline reference value reflecting the shrinkage characteristics of the material under conventional water mixing conditions.

In contrast, for the saline–alkali water mixing environments with different C/S ratios, as the C/S ratio increased gradually from 0.2 to 2.5, the final drying shrinkage rates of the specimens in each experimental group exhibited a clear increasing trend. Furthermore, the final drying shrinkage rates of all saline–alkali water mixing groups were significantly higher than that of the blank group, demonstrating a distinct intensifying effect on drying shrinkage.

Specifically, the final drying shrinkage rate of the C/S = 0.2 group was 4088.57 × 10−6, an increase of 35.35% compared to the blank group; the final value of the C/S = 0.5 group was 4256.43 × 10−6, representing a 40.91% increase relative to the blank group and a further 5.56 percentage points increase in shrinkage increment compared to the C/S = 0.2 group. The final value of the C/S = 1.5 group reached 4802.85 × 10−6, a substantial 58.99% increase compared to the blank group, with the increment expanding significantly by 18.08 percentage points compared to the previous group. The final drying shrinkage rate of the C/S = 2.5 group reached 4885.54 × 10−6, a 61.74% increase compared to the blank group. Although the increasing trend persisted, the increment was only 2.75 percentage points higher than that of the C/S = 1.5 group.

A comparison of the drying shrinkage characteristics between the Chloride–Sulfate system (C/S = 0.5) and the Sulfate–Chloride system (C/S = 1.5) shows that the final drying shrinkage rate of the C/S = 1.5 group is approximately 18.08% higher than that of the C/S = 0.5 group. In contrast, for other ratio groups, the increment of the C/S = 0.5 group compared to the C/S = 0.2 group is only 5.56%, and the increment of the C/S = 2.5 group compared to the C/S = 1.5 group is even as low as 2.75%. The above data indicate that in the mixing water environment dominated by chloride salts (C/S > 1), the drying shrinkage of cement-based materials is significantly higher than that in the mixing water environment dominated by sulfate salts.

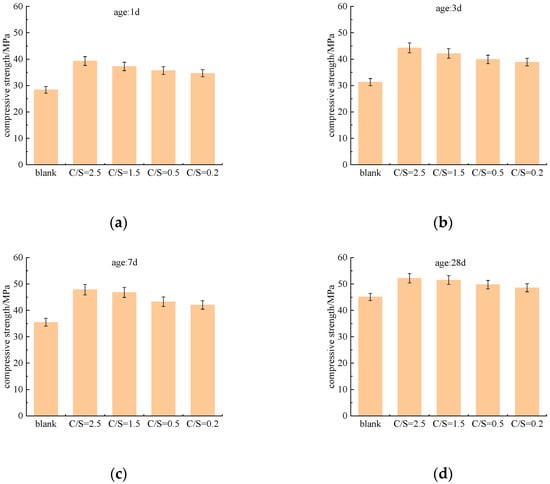

3.2. Effect of Different Salt Compositions on the Early Strength of Cement Paste

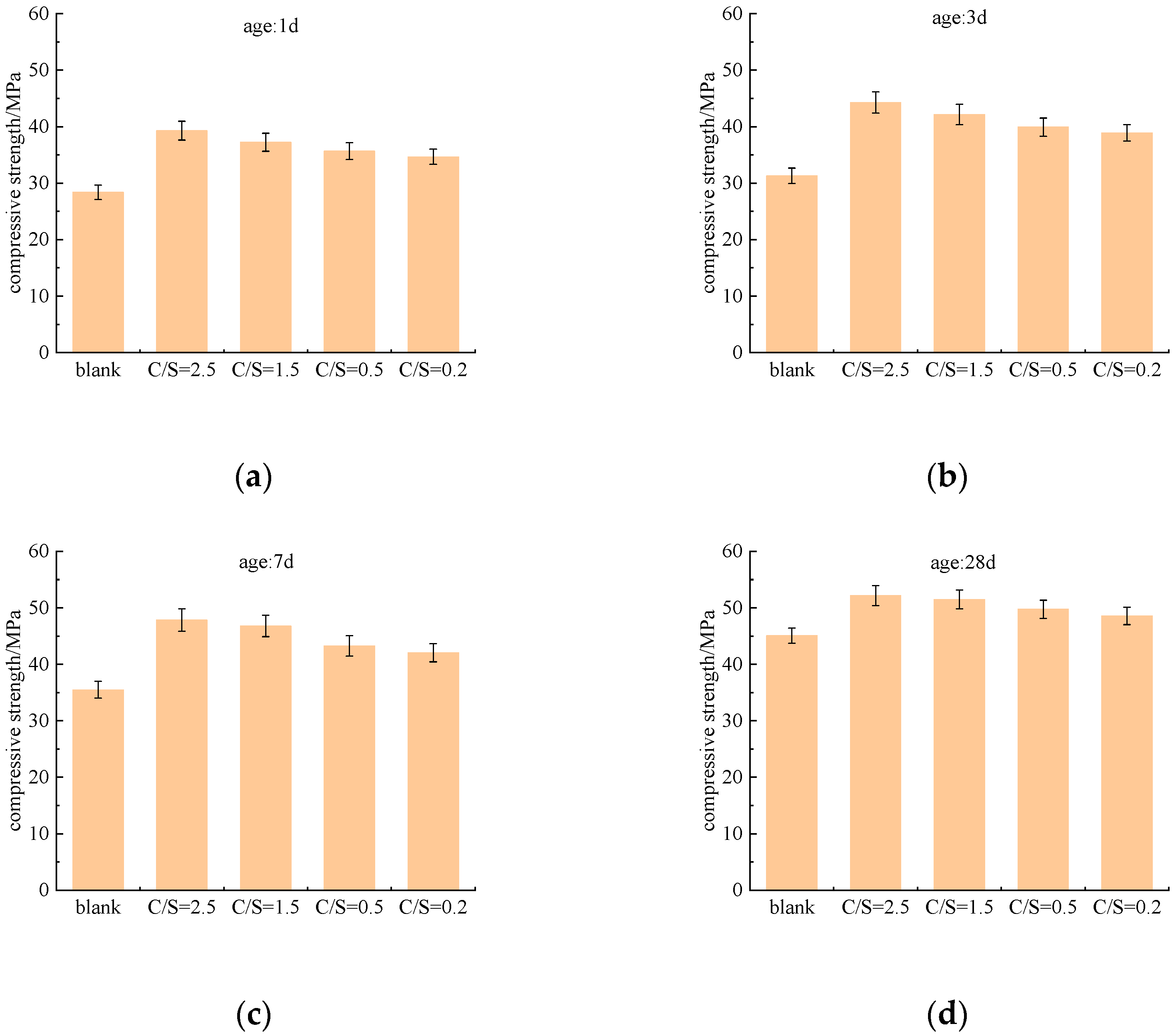

Figure 2 illustrates the influence of the C/S ratio (Cl−/ molar ratio) on the compressive strength of cement paste at different curing ages (1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 28 d). Compared with the blank group, all tested C/S ratios enhanced the early compressive strength of cement paste. The experimental results demonstrate that the utilization of saline–alkali water as mixing water can effectively promote the development of early strength of cement paste.

Figure 2.

Compressive strength of cement paste under different salt composition groups. (a) Curing at 1 d, (b) Curing at 3 d, (c) Curing at 7 d, (d) Curing at 28 d.

At the 1 d curing age, saline–alkali water had already exerted a significant enhancing effect on early strength. The compressive strength of the blank group (mixed with fresh water) was 28.36 MPa, while that of the C/S = 0.2 group reached 34.65 MPa, an increase of approximately 22%. As the C/S ratio increased, the 1 d strength continued to rise, with the highest value observed at C/S = 2.5 (39.27 MPa), representing a 38.5% improvement compared with the blank group. This indicates that a higher C/S ratio can more effectively accelerate early hydration, thereby enhancing early strength.

At the 3 d curing age, all groups showed continued strength growth, and the salt-added groups maintained a clear advantage over the blank group. The strength of the blank group increased by 2.92 MPa from 1 d to 3 d, whereas the saline–alkali water groups exhibited larger increments, ranging from 3.24 MPa to 5.01 MPa. The 3 d strength of the C/S = 2.5 group reached 44.28 MPa, confirming that the promoting effect of the C/S ratio on early strength was sustained and even intensified with increasing C/S ratio.

By the 7 d curing age, the strength-promoting effect of the C/S ratio became less pronounced than at earlier ages but remained significant. The blank group reached 35.49 MPa, while the C/S = 0.2 group was 18.5% higher. With increasing C/S ratio, strength continued to improve, and the C/S = 2.5 group remained the strongest at 47.83 MPa, 34.4% above the blank group. Although the overall trend was consistent with earlier ages, the magnitude of strength enhancement was noticeably reduced.

At the 28 d curing age, strength growth in all groups slowed further, and the influence of saline–alkali water ions continued to diminish. The blank group reached 45.08 MPa, and the C/S = 0.2 group was only 7.7% higher. Even the highest C/S ratio (2.5) resulted in a strength increase of 15.7%, which was substantially lower than the enhancements observed at 1 d and 3 d.

In summary, the compressive strength of the cement paste increases with the C/S ratio at all curing ages, but this effect attenuates significantly with the extension of curing age: it is most pronounced in the early stages (1 d, 3 d), begins to weaken in the middle stage (7 d), and has diminished substantially in the long term (28 d).

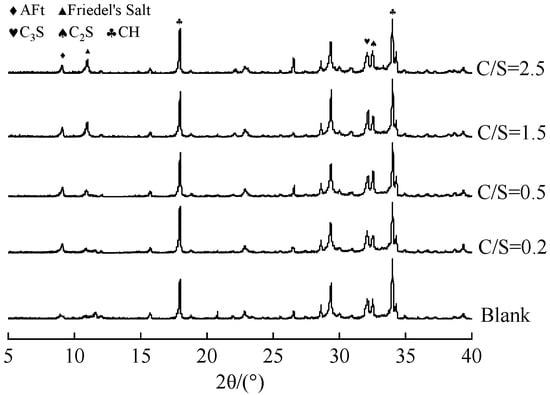

3.3. Phase Analysis of Cement Paste

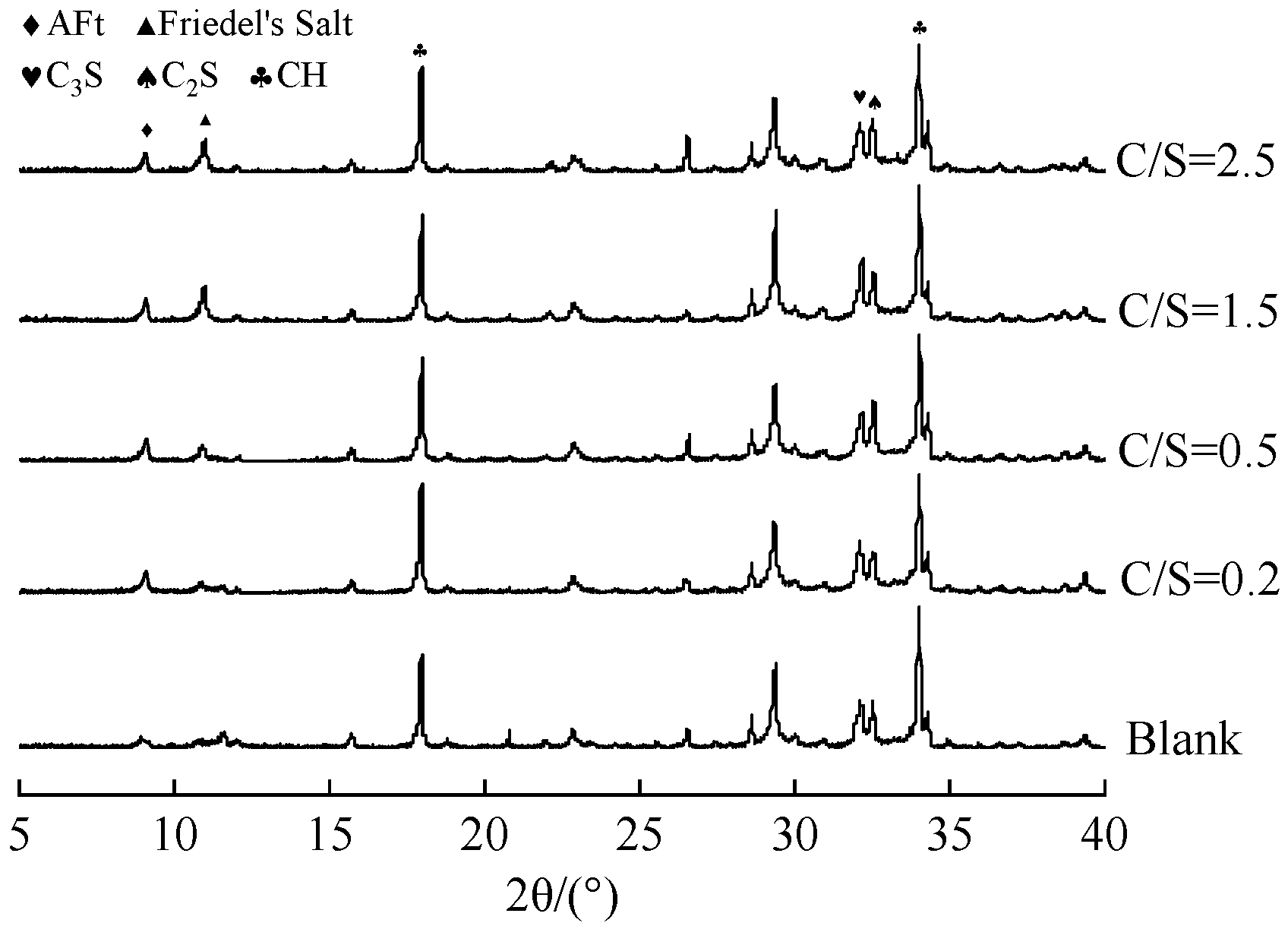

The XRD patterns of 1 d cement paste prepared with mixing water at different C/S ratios are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of cement paste prepared with mixing water of different salt compositions at 1 day of age.

As illustrated in Figure 3, the main hydration products in the pastes mixed with saline–alkali water include ettringite (AFt), Friedel’s salt, and calcium hydroxide (CH). It should be noted that the following analysis is based on qualitative observations of relative peak intensities, as quantitative phase analysis (e.g., Rietveld refinement) was not performed. Compared with the fresh-water group (blank group), both Friedel’s salt and AFt were detected in the saline–alkali water-mixed systems at 1 d. This can be attributed to the fact that in saline–alkali water reacts with CH released during cement hydration to form highly dispersed gypsum with fine particle size, which then reacts with Al phases to produce low-solubility AFt with columnar or acicular morphology [23]. Meanwhile, Cl− in saline–alkali water reacts with tricalcium aluminate (C3A) in cement to form Friedel’s salt [24].

As the C/S ratio increases, the diffraction peak intensity of AFt slightly decreases, while that of Friedel’s salt increases significantly. This phenomenon can be explained by two factors. First, Cl− directly reacts with C3A in the cement system to form Friedel’s salt, thereby consuming Al phases that would otherwise participate in AFt formation and consequently inhibiting AFt formation [25]. Second, after 1 d of hydration, the concentration of in the system decreases, and part of the AFt may convert to monosulfate aluminate hydrate (SO4-AFm). As shown in Equation (1), where 3CaO·Al2O3·CaSO4 corresponds to AFm and 3CaO·Al2O3·CaCl2 corresponds to Friedel’s salt, Cl− in the mixing water further reacts with SO4-Afm to form Friedel’s salt. Although this reaction releases some —which increases the concentration and enhances the structural stability of AFt to a certain extent—the reacted SO4-Afm loses its ability to bind for AFt formation. As a result, the AFt content decreases, and the proportion of Friedel’s salt increases accordingly [26]. These results indicate that increasing the C/S ratio in saline–alkali water promotes Friedel’s salt formation while reducing the AFt content in cement paste. AFt acts as a skeletal framework in cement paste, filling pores and optimizing the pore structure. In addition, the insoluble Friedel’s salt increases the solid phase ratio in the paste, contributing to the formation of a dense skeleton and thus enhancing the early strength of cement paste.

Figure 3 also shows that, compared with the fresh-water blank group, the diffraction peak intensity of CH in the saline–alkali-water-mixed pastes increased significantly and gradually rose with the C/S ratio. This is because Cl− in saline–alkali water reacts with CH in the paste (Equation (2)). Although this reaction may reduce the free CH content, it simultaneously increases the OH− concentration in the pore solution—thereby accelerating the hydration of tricalcium silicate (C3S) and dicalcium silicate (C2S) in cement, promoting more CH formation, and accelerating the overall hydration process of the cement paste. The enhanced degree of hydration refines the pore structure of the hardened paste and intensifies volumetric shrinkage, which ultimately leads to a significant increase in the drying shrinkage rate of the specimens [13,27].

CH + 2NaCl → CaCl2 + 2Na+ + 2OH−.

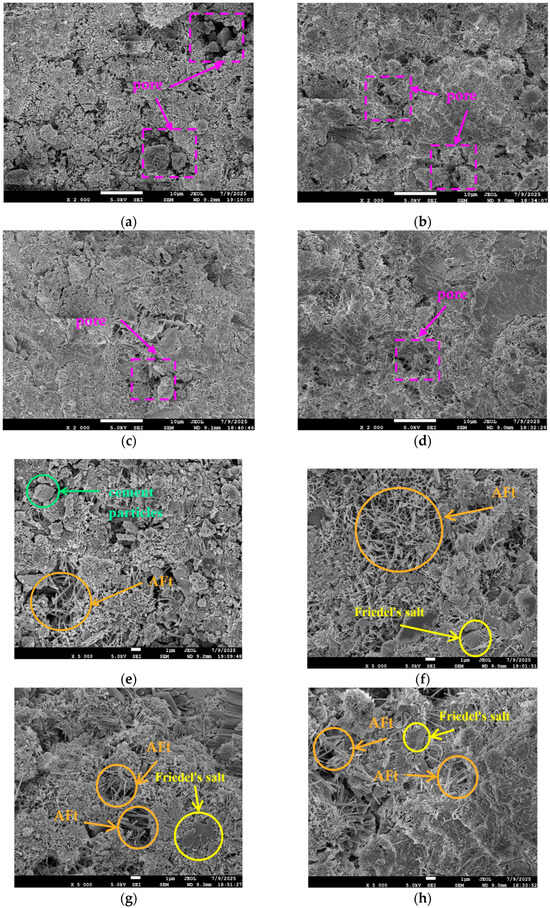

3.4. Microstructural Analysis of Cement Paste

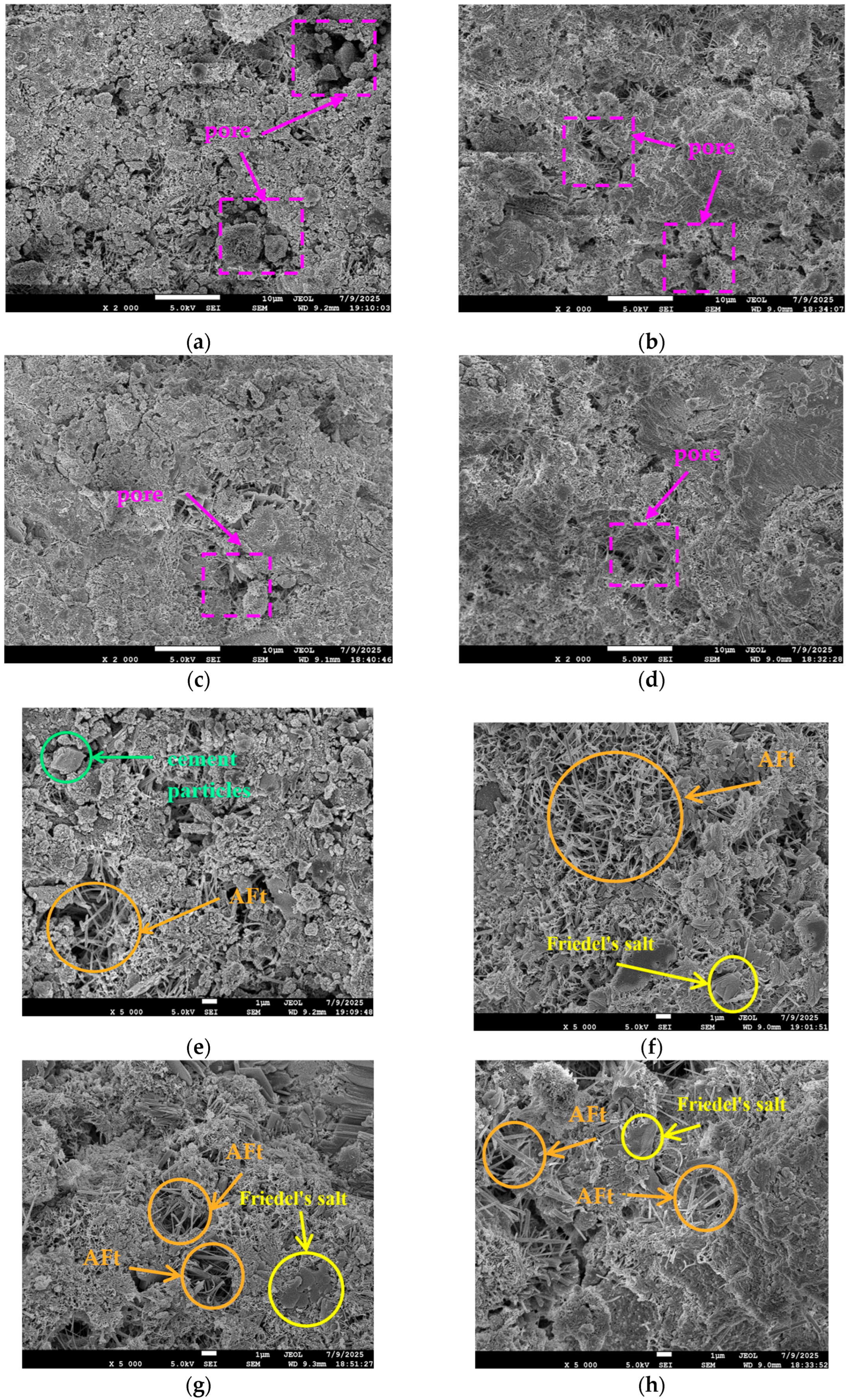

Figure 4 presents the SEM images of 1-day (1 d) cement paste under different salt compositions. As shown in Figure 4a–h, the main hydration products in the cement paste include C-S-H gel, calcium hydroxide (CH), ettringite (AFt), and Friedel’s salt. From Figure 4a–d, it can be observed that within the same curing period, as the C/S ratio (Cl−/) of the mixing water increases, the porosity between hydration products decreases and the compactness of the specimens improves. The blank group cement paste (Figure 4a) exhibits a low degree of hydration at 1 d, with loosely interconnected hydration products, high porosity, and significant pore connectivity—factors that may contribute to its lower compressive strength.

Figure 4.

SEM images of cement paste at 1-day age under different salt compositions. (a) Blank (×2000). (b) C/S = 0.2 (×2000). (c) C/S = 1.5 (×2000). (d) C/S = 2.5 (×2000). (e) Blank (×5000). (f) C/S = 0.2 (×5000). (g) C/S = 1.5 (×5000). (h) C/S = 2.5 (×5000).

In contrast, the paste mixed with saline–alkali water at C/S = 0.2 (Figure 4b) shows a significantly higher degree of hydration and improved structural compactness. Its microstructure contains a large amount of columnar AFt within the pores; these products interweave to form a three-dimensional network structure, enhancing the material’s stability and compactness through both skeletal support and pore-filling effects [28]. As the C/S ratio further increases (Figure 4c,d), the degree of hydration continues to improve, with hydration products becoming more densely interconnected. The pores are effectively filled with AFt, and pore connectivity is further reduced.

Figure 4e–h display the microstructures of hydration products in the cement paste at 1 d for the blank group and various C/S ratio groups. As observed in the blank group (Figure 4e), the hydration reaction is limited, with a small total amount of hydration products and residual unreacted cement particles in the microstructure. The content of AFt—which plays a key role in early strength development—is minimal, and no Friedel’s salt is detected.

In contrast, the cement paste mixed with saline–alkali water at C/S = 0.2 (Figure 4f) contains a large amount of AFt, a small amount of Friedel’s salt, and a significant increase in C-S-H gel, with no unhydrated cement particles remaining. When the C/S ratio increases to 1.5 (Figure 4g), the amount of AFt slightly decreases while the proportion of Friedel’s salt increases; the quantity of C-S-H gel further increases, and the gel exhibits denser interconnection compared to the C/S = 0.2 group. When the C/S ratio increases to 2.5 (Figure 4h), the types and amounts of hydration products are similar to those in the C/S = 1.5 group, but the interconnection between products is even denser.

In summary, increasing the C/S ratio of the mixing water effectively promotes the formation of AFt, Friedel’s salt, and the development of C-S-H gel in cement paste, accelerating the hydration process and facilitating the densification of the early microstructure. This microstructural evolution corresponds to the macroscopic performance changes observed previously—specifically, the increase in early compressive strength and drying shrinkage of the specimens.

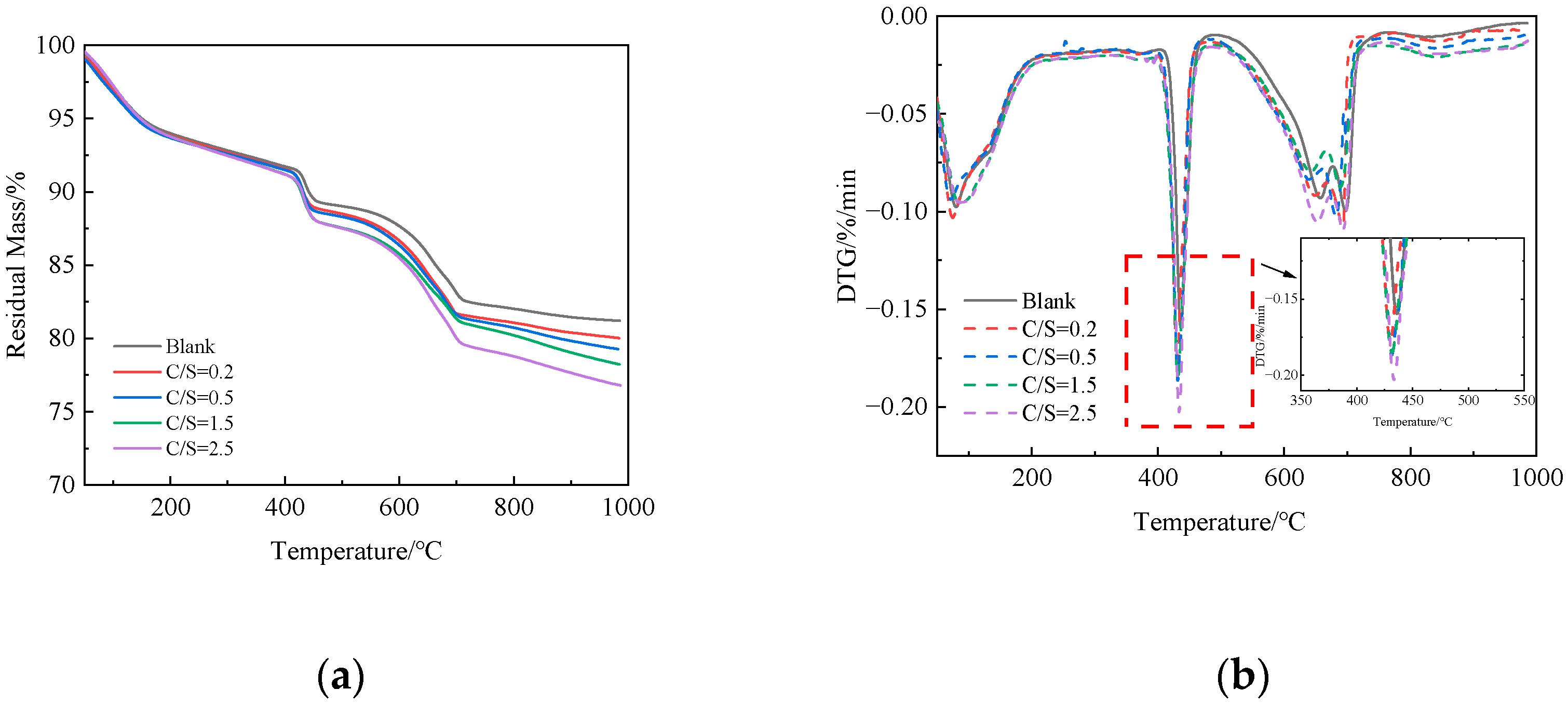

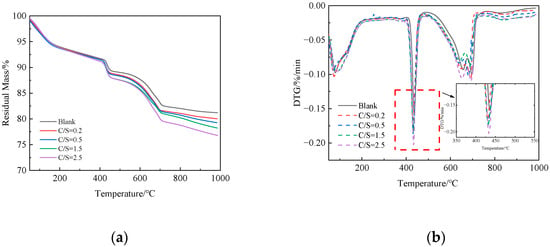

3.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis of Cement Paste

Figure 5 presents the TG-DTG curves of 1 d cement paste under different salt compositions. As shown in Figure 5b, all specimens exhibit endothermic peaks in the ranges of 60–200 °C, 400–500 °C, and 600–700 °C: the mass loss in the 60–200 °C range is attributed to the dehydration of ettringite (AFt) and calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel [29]; the 400–500 °C range corresponds to the decomposition of calcium hydroxide (CH) [30]; and the 600–700 °C range is due to the decomposition of calcium carbonate [31].

Figure 5.

TG-DTG curves of cement paste at 1-day age under different salt compositions: (a) TG; (b) DTG.

Figure 5a shows that, compared to the fresh-water mixed blank group, the cement paste mixed with saline–alkali water exhibits a higher total weight loss in the 50–1000 °C range, which increases continuously with the rise in the C/S ratio. Total weight loss directly reflects the overall hydration degree of cement paste [32], indicating that Cl− and in saline–alkali water accelerate the hydration of clinker minerals (e.g., C3S and C2S) by altering the pore solution chemistry and promoting the formation of hydration products, thereby increasing the total content of hydration products [33]. The accelerated hydration process, on one hand, enhances the formation of hydration products such as AFt and C-S-H gel, improves the microstructural compactness of cement paste, and thus enhances early compressive strength; on the other hand, the rapid hydration reaction induces more significant volumetric shrinkage within cement paste [34]. Consequently, the cement paste mixed with saline–alkali water exhibits a higher drying shrinkage rate.

As seen in Figure 5b, a prominent endothermic peak around 440 °C corresponds to the decomposition of CH, with the temperature range of 400–550 °C being characteristic of CH thermal decomposition. The peak intensity directly reflects the relative content of CH in the system. Compared to the fresh-water mixed blank group, the cement paste mixed with saline–alkali water shows a higher peak intensity, indicating a greater amount of CH formed. This supports the conclusion that Cl− and in saline–alkali water accelerate the hydration of C3S and C2S, leading to increased CH formation. This thermogravimetric result is consistent with the increased CH diffraction peak intensity observed in the XRD patterns with the increase in the C/S ratio, further confirming the promoting effect of saline–alkali water on CH formation in cement paste.

4. Conclusions

This study investigates the effects of saline–alkali water with different C/S (Cl−/ molar ratio) on the drying shrinkage, mechanical properties, phase evolution, and microstructure of cement paste. The main conclusions are drawn as follows:

- Saline–alkali water significantly increases the drying shrinkage of cement paste, and the shrinkage degree continuously increases with the rise in the C/S ratio. This is because Cl− and in saline–alkali water accelerate the hydration of C3S and C2S, promoting the formation of calcium hydroxide (CH) and accelerating the overall hydration process of cement. As the C/S ratio increases, the content of formed CH further increases, which intensifies the volumetric shrinkage effect and thus leads to a sustained increase in drying shrinkage.

- Saline–alkali water effectively enhances the early strength (1–7 d) of cement paste, but this enhancing effect diminishes significantly at the 28 d curing age. The improvement in early strength is attributed to the synergistic effect of two aspects: first, Cl− and in saline–alkali water react with C3A in cement to form ettringite (AFt) and Friedel’s salt, which rapidly fill pores and form a stable structural framework, thereby contributing to the development of early strength; second, Cl− and promote the hydration of C2S and C3S, increasing the formation of CH, which further accelerates the early hydration rate and enhances early strength.

- The C/S ratio significantly affects the hydration products and microstructure of cement paste in a saline–alkali environment. With the increase in the C/S ratio, the content of AFt in cement paste slightly decreases, while the proportion of Friedel’s salt and the content of CH increase. This evolutionary law of hydration products promotes the densification of the early microstructure of cement paste and improves the overall hydration degree of the hardened paste.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Y.C. (Yuxian Chen); validation, Y.C. (Yuxian Chen); formal analysis, Y.C. (Yongyan Chu); investigation, S.Z. (Shiyu Zhang); data curation, P.S. and S.Z. (Shubin Zhou); writing—original draft, Y.C. (Yuxian Chen); writing—review and editing, Y.C. (Yuxian Chen); supervision, S.Z. (Shubin Zhou) and Y.Z.; project administration, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.C. (Yuxian Chen) All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Major Science and Technology Projects of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (No. 2024AA007).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yang Zhou was employed by the company Xinjiang Corps Hydraulic Research Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ge, Z.; Cao, L.; Xue, M.; Song, Y.; Cao, K. Influence of climate change in Southern Xinjiang over last 50 years on available precipitation. J. Hohai Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2010, 38, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, X.; Bai, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, B. Infiltration Characteristics of Soil Moisture in The Stratified Soil of Heavily Sa-line-Alkaline Land in Southern Xinjiang. Agric. Res. Arid Areas 2025, 43, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Bai, J.; Zhao, H.; Liang, N. Distribution Characteristics and Migration Mechanism of Soil Salt in The Aeration Zone of Zrid Oasis Areas—A case study of Yanqi Basin in Xinjiang. Geol. Rev. 2024, 70, 1857–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, R.; Chinnaraju, K. Durability of Ambient Cured Alumina Silicate Concrete Based on Slag/Fly Ash Blends against Sulfate Environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 204, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Goyal, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Reddy, M.S. Protection of Concrete Structures under Sulfate Environments by Using Calcifying Bacteria. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 209, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.A.; Horvath, A.; Monteiro, P.J.M. Impacts of Booming Concrete Production on Water Resources Worldwide. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Fang, H.; Yuan, J.; Tang, S. The Early-Age Cracking Sensitivity, Shrinkage, Hydration Process, Pore Structure and Micromechanics of Cement-Based Materials Containing Alkalis with Different Metal Ions. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 18, 100454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jin, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, S. Hydration, Shrinkage, Pore Structure and Fractal Dimension of Silica Fume Modified Low Heat Portland Cement-Based Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 272, 121952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, J.; Peng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tang, S.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L. Thermodynamics-Based Simulations of the Hydration of Low-Heat Portland Cement and the Compensatory Effect of Magnesium Oxide Admixtures. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 2025, 26, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.K. Concrete Technology at the Crossroads—Problems and Opportunities; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 1994; Volume 144, pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Burrows, R.W. The Visible & Invisible Cracking of Concrete; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-87031-047-8. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Li, Z. Influence of Alkali on Restrained Shrinkage Behavior of Cement-Based Materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, M.; Yin, H.; Jiang, K.; Xiao, K.; Tang, S. Influence of Different Alkali Sulfates on the Shrinkage, Hydration, Pore Structure, Fractal Dimension and Microstructure of Low-Heat Portland Cement, Medium-Heat Portland Cement and Ordinary Portland Cement. Fractal Fract. 2021, 5, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wang, K.; Shi, J.; Wang, Y. Influence of Sodium Aluminate on Cement Hydration and Concrete Properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 64, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, B.; Matschei, T.; Scrivener, K. The Influence of Sodium Salts and Gypsum on Alite Hydration. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 75, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghtalab, A.; Badizad, M.H. Solubility of Gypsum in Aqueous NaCl + K2SO4 Solution Using Calcium Ion Selective Electrode-Investigation of Ionic Interactions. Fluid Ph. Equilib. 2016, 409, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Guo, L.; Xue, X. Effects of Sodium Chloride and Sodium Sulfate on Hydration Process. J. Southeast Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 49, 712–719. [Google Scholar]

- Montanari, L.; Suraneni, P.; Tsui-Chang, M.; Khatibmasjedi, M.; Ebead, U.; Weiss, J.; Nanni, A. Hydration, Pore Solution, and Porosity of Cementitious Pastes Made with Seawater. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2019, 31, 04019154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, A.; Ebead, U.; Suraneni, P.; Nanni, A. Fresh and Hardened Properties of Seawater-Mixed Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 190, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, W.; Yu, T.; Qu, F.; Tam, V.W.Y. Investigation on Early-Age Hydration, Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of Seawater Sea Sand Cement Mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 249, 118776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hou, D.; Gao, Y. Uniform Driving Force for Autogenous and Drying Shrinkage of Concrete. J. Tsinghua Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2010, 50, 1321–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, W. Tests and Simulations of Interior Humidity and Shrinkage of Concrete under Sealed Condition. J. Build. Mater. 2013, 16, 203–209, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Feng, P.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Bullard, J.W. Dissolution and Early Hydration of Tricalcium Aluminate in Aqueous Sulfate Solutions. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 137, 106191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, W.; Sun, Z.; Shen, L.; Sheng, D. Development of Sustainable Concrete Incorporating Seawater: A Critical Review on Cement Hydration, Microstructure and Mechanical Strength. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 121, 104100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, M.; Cai, Y.; Chen, B.; Li, Z. Chloride Binding Behaviors and Early Age Hydration of Tricalcium Aluminate in Chloride-Containing Solutions. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 137, 104928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekolu, S.; Solomon, F.; Rakgosi, G. Chloride—Induced Delayed Ettringite Formation in Portland Cement Mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 340, 127654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebead, U.; Lau, D.; Lollini, F.; Nanni, A.; Suraneni, P.; Yu, T. A Review of Recent Advances in the Science and Technology of Seawater-Mixed Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 152, 106666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z. Cementitious Material Science; Wuhan University of Technoligy Press: Wuhan, China, 2014; ISBN 978-7-5629-4684-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, Z.; Ansari, W.S.; Akbar, M.; Azam, A.; Lin, Z.; M Yosri, A.; Shaaban, W.M. Microstructural and Mechanical Assessment of Sulfate-Resisting Cement Concrete over Portland Cement Incorporating Sea Water and Sea Sand. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, H.; Chen, R.; Wang, M.; Chen, R.; Weng, L.; Wang, D. Effects of Seawater Concentration on the Drying Shrinkage of Seawater Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 457, 139437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Zaheer, M.H.; Jang, I.; Park, G.-J.; Park, J.-J.; Hong, S.; Lee, N. Utilizing Carbonated Reclaimed Water as Concrete Mixing Water: Improved CO2 Uptake and Compressive Strength. Materials 2025, 19, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, E.; Li, L. Multiscale Investigations on Hydration Mechanisms in Seawater OPC Paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 191, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, P.; Hanif, A.; Li, Z. Early-Age Properties of Cementitious Pastes Made with Seawater. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 65, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, M. Influence of Different Alkali Sulfates on Shrinkage Properties of Cement based Materials with Different Mineral Composition. J. Yangtze River Sci. Res. Inst. 2022, 39, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.