Abstract

To enhance the damage resistance of protective engineering materials under extreme loads such as explosions and impacts, this study, building upon the improvement in impact resistance of concrete achieved by rubber modification, further incorporates steel fibers and glass fibers to synergistically enhance impact resistance and to investigate the underlying mechanisms. Using split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) testing, a comparative investigation was conducted on the dynamic mechanical responses of four specimen groups, namely plain rubberized concrete, single steel fiber-reinforced, single glass fiber-reinforced, and hybrid steel–glass fiber-reinforced rubberized concrete, over a strain-rate range of 30–185 s−1. The results demonstrate that the incorporation of hybrid fibers significantly enhances the dynamic compressive performance of plain rubber concrete. Specifically, the dynamic compressive strength increases from 40.73–61.29 MPa to 60.25–101.86 MPa, accompanied by a 59.5% increase in strain-rate sensitivity. Meanwhile, the fragment fineness modulus after failure rises from 3.20–3.33 to 3.73–4.20, indicating improved post-impact integrity. In addition, the hybrid fiber-reinforced specimens exhibit the highest energy dissipation capacity at identical strain rates. Their dynamic stress–strain responses are characterized by higher stiffness, improved ductility, and more pronounced progressive failure behavior. These findings provide experimental evidence for the design of high-impact-resistant protective engineering materials.

1. Introduction

In modern national defense and critical infrastructure protection, structures are often exposed to extreme dynamic threats, including blast loading and projectile penetration [1]. These loads are distinguished by exceptionally high loading rates, generating intense compressive stresses within milliseconds or even microseconds, with damage effects far more severe than those induced by conventional static loading [1,2,3]. As the most extensively utilized construction material, the mechanical behavior of concrete under high-strain-rate compressive loads plays a decisive role in the survivability and damage resistance of protective engineering systems. Nevertheless, numerous studies and practical failures indicate that the intrinsic brittleness and limited toughness of conventional concrete cause catastrophic fragmentation under dynamic impact, accompanied by inadequate energy absorption, making it difficult to satisfy the growing requirements for impact-resistant protection [4]. Consequently, advancing the understanding and improvement of concrete’s dynamic impact resistance has emerged as a pressing and essential research focus in the domain of protective engineering materials.

Rubber is a viscoelastic organic polymer characterized by a relatively low elastic modulus and excellent deformation resistance [2]. Existing research indicates that the inclusion of rubber particles as fine aggregates enhances the energy dissipation capability of concrete under dynamic loading due to their deformation-resistant nature, consequently improving impact resistance [2,5]. It has been reported that rubber aggregate incorporation markedly increases the number of impact blows concrete can withstand before failure, with impact energy absorption enhanced by about 260% and 660% at rubber contents of 20% and 50%, respectively [6]. These findings have been further corroborated by Aly et al. [7] and Abdelmonem et al. [8]. In addition, rubberized concrete shows a markedly slower crack propagation rate than conventional concrete [9]. Atahan and Yücel [10] demonstrated that at rubber contents of 20–40%, concrete not only effectively resists impact-induced cracking but also substantially restrains crack growth and ultimate structural damage. Furthermore, incorporating rubber into concrete offers an effective route for the valorization of waste tires. This practice contributes to resource conservation and reduced landfilling, while mitigating fire hazards associated with tire stockpiles and preventing the leakage of toxic substances, including nitrogen dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, and heavy metals, into the subsurface environment [11,12]. However, it is well recognized that the incorporation of rubber aggregates adversely affects the compressive strength of concrete [13]. This detrimental effect is commonly ascribed to the inherently low mechanical stiffness of rubber aggregates and the weak interfacial transition zone formed between rubber particles and the cementitious matrix [14]. Accordingly, from a holistic performance perspective, excessive rubber incorporation is not recommended, and Li et al. proposed that a 10% fine aggregate replacement ratio is optimal [15]. The constraint on rubber replacement levels has therefore driven ongoing research into additional strategies for improving the impact resistance of concrete.

Fiber-reinforced concrete has emerged as one of the key research focuses in the field of high-performance construction materials [16]. The critical factors influencing the effectiveness of fiber-reinforced concrete are the fiber volume fraction, tensile strength, aspect ratio, and the anchorage mechanism at the fiber-matrix interface [17,18]. As demonstrated in the research of Mirzaaghabeik et al., a systematic evaluation was conducted on the shear-strengthening efficacy of hooked-end steel fibers (HE, 2% vol.), SD steel fibers (0.76% vol.), and Forta-Ferro (FF) synthetic fibers (0.11% vol.) in UHPC beams [17]. It was shown that hooked-end steel fibers performed most notably in enhancing ductility, owing to their greater volume fraction, higher tensile strength, and distinctive anchorage effect. Notably, the FF synthetic fibers employed, although possessing inferior tensile strength relative to the other two fibers, enabled beams with a mere 0.11% fiber volume fraction to achieve approximately 80% of the mechanical load-bearing capacity of beams containing 0.76% SD steel fibers. This is attributed to their higher aspect ratio (~68) and characteristic flexibility, which facilitate greater deformation and energy dissipation via fiber pull-out during crack propagation. Incorporating fibers into rubberized concrete is expected to provide additional overall improvements in impact resistance [19,20,21]. Owing to its outstanding tensile strength and crack-arresting capability, steel fiber is currently the most commonly employed fiber reinforcement in concrete. Previous research has demonstrated that steel fiber incorporation significantly improves the dynamic compressive strength and toughness of concrete, especially under impact and high strain-rate conditions [22,23]. This enhancement is attributed to the crack-bridging action of steel fibers, which strengthens matrix bonding, restrains crack development during failure, and increases the energy dissipation capacity of the composite [24,25]. From an engineering standpoint, the severity of impact hazards faced by protective structures—such as high-speed collisions and terrorist attacks—is expected to increase with technological advances, underscoring the importance of exploring additional strategies beyond steel fiber reinforcement to further improve concrete’s impact resistance. Accordingly, hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete systems aimed at enhancing impact resistance have drawn considerable interest in the research community. These hybrid systems demonstrate synergistic performance under dynamic loading that surpasses that of single-fiber-reinforced concretes [26]. Zhao et al. reported that a hybrid system composed of steel fibers and synthetic plastic fibers at a 1:3 volume ratio markedly improved the dynamic compressive strength of concrete and substantially enhanced post-failure specimen integrity [20]. Li et al. demonstrated that steel–polyethylene hybrid fibers synergistically improved both the dynamic compressive strength and deformation capacity of concrete under combined static–dynamic loading conditions [26]. Alwesabi et al. [27,28] found that combining steel fibers (0.9%) and polypropylene fibers (0.1%) in rubberized concrete containing 20% rubber significantly improves its dynamic impact resistance. This behavior arises from the ability of fibers with different length scales to restrain crack growth at both macro- and micro-scales, resulting in complementary synergistic reinforcement. Moreover, combining fibers with different elastic moduli creates a reinforcement network with a gradual modulus transition, improving stress transmission and energy dissipation mechanisms under dynamic loading [29]. Compared to the fibers discussed above, glass fibers offer greater stability, tensile strength and improved compatibility with cement-based matrices [30]. Moreover, glass fibers possess a density comparable to that of concrete, thereby avoiding excessive structural weight, and they also offer notable cost advantages [31]. Accordingly, glass fibers demonstrate considerable potential for enhancing the dynamic impact resistance of concrete. Nevertheless, studies on the application of glass fibers in rubberized concrete are still relatively scarce. The effects of glass fibers, as well as their hybridization with steel fibers, on improving the dynamic compressive performance of rubberized concrete need to be more quantitatively evaluated to provide reliable guidance for engineering practice.

Using a split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) system, this study systematically evaluated the dynamic compressive behavior of four concrete mixtures—plain rubberized concrete, single steel fiber-reinforced, single glass fiber-reinforced, and hybrid fiber-reinforced rubberized concrete—over a strain-rate range of 30–185 s−1. Through comprehensive evaluation of dynamic compressive strength, dynamic increase factor (DIF), failure characteristics, fragment distribution, dynamic stress–strain responses, and energy absorption capacity, this work elucidates the synergistic reinforcement mechanisms and strain-rate effects of steel and glass fibers under impact loading, examines their interaction with rubber, and ultimately provides experimental and theoretical support for the design and application of concrete materials in high-impact-resistant protective engineering.

2. Experimental Methodology

2.1. Experimental Materials and Specimen Preparation

2.1.1. Raw Materials

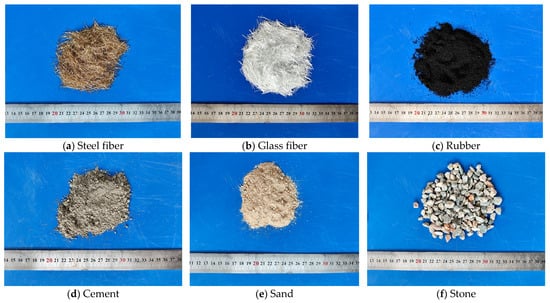

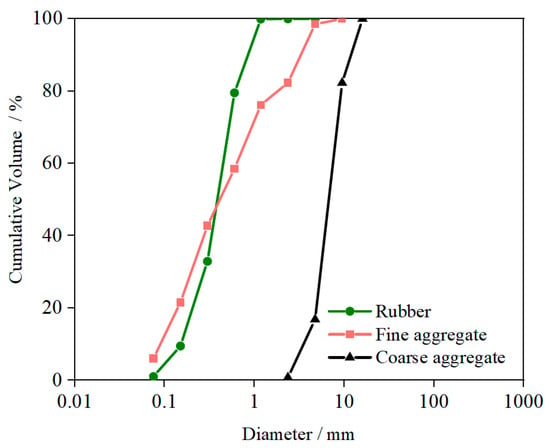

Figure 1 shows the various raw materials used in this study. P·O 42.5R ordinary Portland cement was employed in the present study. Natural river sand served as the fine aggregate, exhibiting a fineness modulus of 3.02, an apparent density of 2518 kg/m3, and a water absorption rate of 0.61%. Granite crushed stone with particle sizes between 4.65 and 10 mm was used as the coarse aggregate (Figure 2), having an apparent density of 2641 kg/m3 and a water absorption of 2.1%. The rubber particles used corresponded to a 20-mesh size (Figure 2), with an average diameter of approximately 0.38 mm. Copper-coated hooked-end steel fibers and glass fibers were selected as reinforcements, with their key physical and mechanical properties summarized in Table 1. Furthermore, a polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer was incorporated in specimen preparation, featuring a specific gravity of 1.02 and a solid content of 9%.

Figure 1.

Raw materials.

Figure 2.

Particle size distribution of materials.

Table 1.

Parameters of fibers.

2.1.2. Mix Proportion Design for Specimens

Drawing on previous studies and preliminary mix trials, four concrete mix designs were developed in this study, as presented in Table 2. The concrete matrix was proportioned with a cement: water: fine aggregate: coarse aggregate: superplasticizer ratio of 1:0.396:1.345:1.536:0.005. The rubber and fiber contents were determined on a volumetric basis. The rubber replacement level was fixed at 10% of the total fine aggregate volume to maintain balanced overall performance of the concrete [15]. Prior work by the authors’ research group demonstrated that optimal enhancements in static compressive strength of rubberized concrete are achieved with steel and glass fiber contents of 1.2% and 0.4% (volume fraction), respectively [15]. Accordingly, steel fiber contents of 0 and 1.2% and glass fiber contents of 0 and 0.4% were selected to systematically examine the synergistic potential of the two fibers in improving the dynamic compressive behavior of rubberized concrete.

Table 2.

Mix proportions of rubber concrete (kg/m3).

2.1.3. Specimen Preparation and Curing

For static compression tests, cylindrical specimens measuring 100 mm in diameter and 200 mm in height were prepared, whereas dynamic compression tests employed short cylinders with a diameter of 100 mm and a height of 50 mm. Specimen preparation was carried out according to the following procedure: (1) Cement, sand, rubber particles, and fibers were first introduced into a mixer and dry-mixed for 60 s; (2) Water was premixed with a high-range water-reducing admixture, after which about 70% of the solution was added and mixed for 60 s; (3) Coarse aggregates were subsequently introduced along with the remaining 30% of the liquid admixture, and mixing proceeded for 180 s until uniformity was achieved; (4) The fresh concrete was poured into SBS plastic molds, fully vibrated, and then covered with a white waterproof film to minimize moisture loss; (5) Specimens were kept at room temperature (20 ± 2) °C for 24 h before demolding, followed by standard water curing for 28 d. Overall, 12 specimens were fabricated for static testing (three replicates for each mix). For dynamic testing, a total of 24 specimens (6 for each mix) were prepared to be tested at six targeted strain-rate levels to characterize the strain-rate sensitivity.

2.2. Test Equipment

2.2.1. Static Compressive Test

In this study, the results of static compressive tests were mainly used to calculate the dynamic increase factor (DIF) of the specimens and to analyze its relationship with strain rate. The tests were conducted in accordance with ASTM C39 [32]. Static compression tests were performed using an electro-hydraulic servo testing system (MATEST) with displacement control at a loading rate of 0.12 mm/min. To minimize the effect of end friction on the measured strength, the specimen ends were capped with gypsum, ensuring uniform contact between the loading surfaces and the loading platens. For each mix group, three replicate specimens were tested, and the reported strength represents the average value.

2.2.2. Dynamic Compression Test

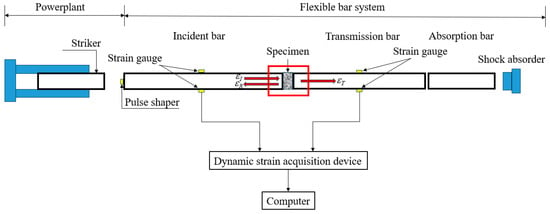

A split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) system was employed for the experiments (Figure 3). The SHPB setup consisted of a 1000 mm striker bar, a 5500 mm incident bar, and a 3500 mm transmission bar, all with a diameter of 100 mm, an elastic modulus (Eb) of 206 GPa, and a density (ρb) of 7710 kg/m3. According to Equation (1), the elastic wave velocity of the bars (Cb) was determined to be 5169 m/s. To improve waveform quality and realize near-constant strain-rate loading, a T2 copper pulse shaper with a diameter of 20 mm and a thickness of 2 mm was mounted at the center of the incident bar impact face to attenuate high-frequency oscillations in the incident pulse. Dynamic mechanical responses were measured using electrical resistance strain gauges attached to the bars (BE120-3AA-P200, resistance 120.0 ± 0.1 Ω, gauge factor 2.22 ± 1%). The strain gauges sense the minute surface strains induced by propagating stress waves and convert them into electrical signals, providing the basis for reconstructing the specimen’s dynamic stress–strain relationship based on one-dimensional stress wave theory [33]. Strain signals were acquired using a multichannel high-precision dynamic data acquisition system (DH5960) at a sampling rate of 1 MHz, enabling accurate digitization and faithful capture of transient dynamic processes.

Figure 3.

Setup of Split Hopkinson Pressure Bar.

The specimen placement is shown in Figure 4. Before testing, both ends of the specimens were ground using a MY250 high-precision grinder to ensure flat and smooth surfaces, with end-to-end parallelism deviations limited to within 0.02 mm. The grinder provides a machining accuracy characterized by a surface roughness of Ra ≤ 0.1 μm and a parallelism tolerance of 0.01 mm over 300 mm.

Figure 4.

Specimen placement.

In the dynamic compressive test, the striker impacts the incident bar at a prescribed velocity, generating an incident strain wave (t). When the incident wave reaches the specimen, the mismatch in wave impedance between the elastic bars and the specimen causes part of the incident wave to be reflected back into the incident bar, forming the reflected wave (t), while the remaining portion is transmitted through the specimen into the transmission bar as the transmitted wave (t). The incident, reflected, and transmitted strain signals are recorded using strain gauges mounted on the bars. The one-dimensional stress wave assumption states that stress waves propagate strictly along the axial direction of the slender elastic bars, whereas the stress uniformity assumption implies that wave attenuation during propagation within the specimen and bars can be neglected. These two assumptions form the theoretical foundation of the SHPB technique [32]. After verifying their validity, the stress, strain, and strain rate of the specimen were derived according to one-dimensional stress wave theory, as expressed in Equation (2). By further applying the stress equilibrium condition given in Equation (3), the governing relations can be simplified to Equation (4).

where Ab is the cross-sectional area of the SHPB bars, A0 is the initial cross-sectional area of the specimen, l0 is the specimen thickness, and εt(t) and εr(t) are the transmitted and reflected strain signals recorded by the data acquisition system, respectively.

In dynamic impact tests, inertial effects and end friction are two major factors that can compromise data accuracy. Both effects tend to overestimate the dynamic compressive strength by introducing additional confinement stresses, thereby altering the intrinsic stress state of the specimen. To minimize inertial effects, specimens with a length-to-diameter ratio of 0.5 were employed in this study [34]. This geometry shortens the stress-wave propagation and stress equilibrium time, allowing the inertial contribution during loading to manifest as a relatively stable and theoretically tractable additional confining pressure, which enhances the reliability and interpretability of the dynamic test results. To reduce end friction effects, petroleum jelly was applied to both loading faces of the specimens prior to testing, ensuring a more realistic evaluation of the material strength [35].

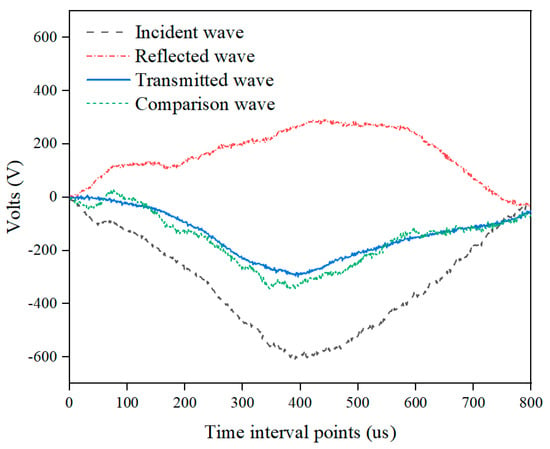

2.3. Experimental Validity Verification

To satisfy the assumptions of one-dimensional stress wave propagation and stress uniformity, achieving stress equilibrium within the specimen is a fundamental prerequisite for SHPB testing. Figure 5 illustrates the time histories of the incident stress wave σi(t), reflected stress wave σr(t), and transmitted stress wave σt(t) for the S1.2G0.4 specimen tested at a strain rate of 36.28 s−1. As shown, the superposition of the incident and reflected stress waves agrees well with the transmitted stress wave (σi(t) + σr(t) ≈ σt(t)), indicating that stress equilibrium was successfully established during the main loading stage. Moreover, wave dispersion effects are negligible throughout the test, suggesting that the stress within the specimen can be considered uniformly distributed. These observations confirm that the specimen reached a stable stress equilibrium state, thereby ensuring the reliability and validity of the experimental results obtained in this study.

Figure 5.

Validity verification for test study.

3. Test Results

3.1. Static/Dynamic Compressive Strength

In this study, the static compressive strength test was mainly conducted to calculate the Dynamic Increase Factor (DIF). The test results are presented in Table 3. The average compressive strength of the S0G0 samples was 38.07 MPa. The addition of steel and glass fibers enhanced the compressive strength to different extents. The compressive strengths of the S1.2G0 and S0G0.4 samples were 45.67 MPa and 39.53 MPa, respectively, indicating increases of 20.0% and 3.8% compared to the baseline group. The S1.2G0.4 group exhibited the best static compressive strength performance (47.82 MPa), showing a 25.6% improvement over the baseline group.

Table 3.

Static compression test results—fc (MPa).

The dynamic compressive strength results derived from the split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) tests are summarized in Table 4. The experiments encompassed a strain-rate range from approximately 30 s−1 to 185 s−1.

Table 4.

Dynamic compression test results.

All mixtures demonstrated a significant strain-rate sensitivity, with dynamic compressive strength increasing monotonically as the strain rate rose. Fiber addition markedly influenced both the dynamic compressive strength and strain-rate sensitivity of the concrete. At similar strain rates, the plain rubberized concrete (S0G0) showed the lowest dynamic compressive strength, ranging between 40.73 and 61.29 MPa. Addition of a single fiber type improved strength: the glass fiber-reinforced mixture (S0G0.4) attained 44.27–73.53 MPa, whereas the steel fiber-reinforced mixture (S1.2G0) reached 51.15–90.43 MPa. In contrast, the hybrid steel–glass fiber mixture (S1.2G0.4) demonstrated the superior dynamic compressive performance, with strength ranging from 60.25 to 101.86 MPa, markedly surpassing all other groups.

3.2. Fragments Modes

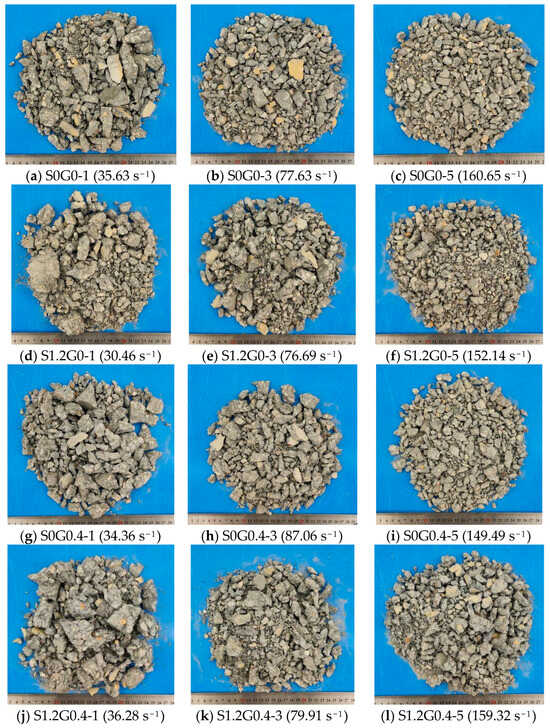

Figure 6 illustrates the typical fragment patterns of the four specimen groups subjected to impact loading at various strain rates. In general, higher strain rates led to more severe fragmentation in all specimens. At comparable strain rates, it is evident that fiber addition altered the failure patterns. Visually, the hybrid steel–glass fiber specimen (S1.2G0.4) retained the highest post-failure integrity. Under comparable strain rates, the hybrid specimen produced fewer yet larger primary fragments, maintaining its overall shape more effectively than the other groups.

Figure 6.

Post-impact fragments at various strain rates.

To further investigate the fragmentation behaviour at different strain rates, the fineness modulus of the fragments was determined following the sand fineness modulus testing procedure outlined in GB/T 14684-2022 [36]. The fragments from Figure 4 were sieved using six sieves with geometrically decreasing apertures of 20 mm, 10 mm, 5 mm, 2.5 mm, 1.25 mm, and 0.625 mm (Figure 7). The fineness modulus of the fragments in this study was computed using Equation (5):

Figure 7.

Sieving test.

In the equation, Mx is the fineness modulus, A1–A6 are the cumulative percentages retained on the 20 mm, 10 mm, 5 mm, 2.5 mm, 1.25 mm, and 0.625 mm sieves, respectively.

Table 5 summarizes the cumulative percent retained and fineness modulus of the specimens shown in Figure 4. In general, the fineness modulus decreases as the strain rate increases, indicating that higher impact energy leads to more severe fragmentation. Among the mixtures, the plain rubberized concrete (S0G0) exhibited the lowest fineness modulus (3.20–3.33), suggesting the most severe fragmentation, the smallest fragment sizes, and the poorest post-failure integrity under impact. Incorporation of fibers led to a marked increase in the fineness modulus of the specimens. The glass fiber-reinforced mixture (S0G0.4) displayed a slightly higher fineness modulus (3.45–3.65) than the plain mixture, whereas the steel fiber-reinforced mixture (S1.2G0) showed a more significant enhancement (3.59–3.84). The hybrid steel–glass fiber mixture (S1.2G0.4) consistently exhibited the highest fineness modulus (3.73–4.20) across all strain rates, visually indicating the largest post-failure fragment size and the best structural integrity.

Table 5.

Cumulative sieve residue percentage (%) and fineness modulus.

3.3. Strain Rate Effect

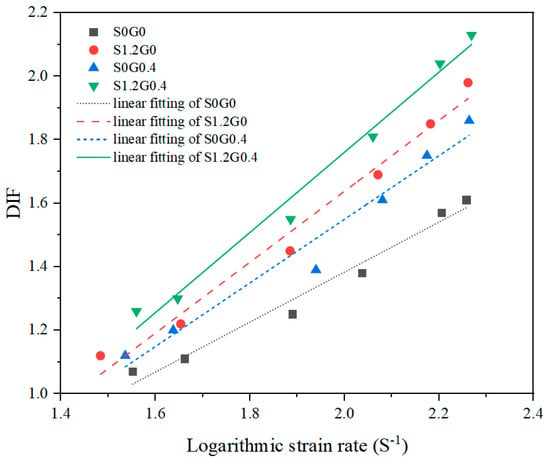

The dynamic increase factor (DIF) is a key parameter for quantifying the strain-rate sensitivity of material strength. In this study, DIF is defined as the ratio of the dynamic compressive strength to the corresponding static compressive strength, as listed in Table 3. Figure 8 presents the fitted relationships between DIF and the logarithm of strain rate [37]. The correlation between DIF and the logarithmic strain rate can be described by Equation (6):

where a is the slope of the fitted line, representing the degree of strain-rate sensitivity. The fitted equations for the four mix proportions are summarized in Table 6. As shown in Figure 9, a clear linear relationship is observed between the dynamic increase factor (DIF) and the logarithm of strain rate for all mixes. The coefficients of determination (R2) are all close to unity (Table 6), demonstrating that the adopted linear model provides an accurate description of the strain-rate dependence of DIF.

Figure 8.

Relationship between DIF and logarithmic strain rate.

Table 6.

Fitting results for DIF against log strain rate.

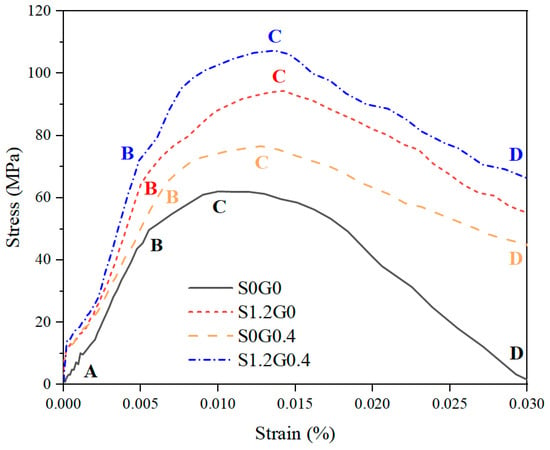

Figure 9.

Dynamic stress–strain relationship.

For all groups, DIF increased markedly with strain rate, and the hybrid steel–glass fiber mixture (S1.2G0.4) consistently exhibited higher DIF values than the other three mixtures throughout the tested range (~30–185 s−1). Fiber addition led to a significantly increased slope of the fitted curves relative to the plain rubberized concrete (S0G0). The descending order of the slopes for the four mixtures is as follows: S1.2G0.4 (1.26) > S1.2G0 (1.12) > S0G0.4 (1.00) > S0G0 (0.79). Compared with S0G0, S1.2G0.4 exhibits an increase of 59.5%. These findings suggest that the hybrid incorporation of steel and glass fibers significantly amplifies the strain-rate sensitivity of rubberized concrete, making this mixture’s strength most responsive to variations in strain rate. This further confirms that the combined incorporation of 1.2% steel fibers and 0.4% glass fibers in this study yields a positive synergistic effect.

3.4. Dynamic Stress–Strain Relationship

Figure 9 presents the dynamic compressive stress–strain relationships for the four concrete mixtures under different strain rates. Given the similarity of stress–strain curves across different strain rates, the analysis focuses on the maximum strain rate (~180 s−1) for illustration. The figure identifies distinct failure stages: (a) Elastic stage (A–B), representing the initial phase of dynamic loading, during which stress rises linearly with strain, reflecting minimal specimen damage and the initiation of microcracks. At this stage, the load is jointly borne by the rubberized concrete matrix and the fibers. (b) Crack propagation stage (B–C), where ongoing stress increase causes the microcracks formed during the elastic stage to propagate, leading to a growing number of internal cracks. The stress–strain curve slope gradually diminishes, and the stress attains its peak value. During this stage, fibers serve a critical function in bridging the cracks. (c) Failure stage (C–D), during which, after peak stress is reached, internal cracks propagate and merge to form primary cracks. Crack widths further widen, with fibers being pulled out or fractured, ultimately leading to specimen failure and complete loss of load-bearing capacity.

Compared to plain rubberized concrete (S0G0), the fiber-reinforced mixtures (S1.2G0, S0G0.4, S1.2G0.4) showed greater dispersion in both the elastic (A–B) and failure (C–D) stages, indicating that fibers regulate internal stress distribution and damage progression within the material. During the elastic rising stage, the addition of fibers increased the initial slope of the stress–strain curve, representing an enhanced dynamic elastic modulus, with steel fibers providing the most pronounced effect. During the subsequent stage of crack stabilization and propagation (B–C), the hybrid fiber group (S1.2G0.4) shows the steepest slope, indicating that the combined steel and glass fibers provide more effective confinement within the matrix. This delays the damage accumulation rate, allowing the material to maintain optimal load-bearing capacity even under damage conditions. With increasing load, the fiber-reinforced curves exhibited a gentler nonlinear hardening region near the peak stress, likely due to fibers bridging microcracks and thereby delaying macroscopic failure.

During the post-peak failure stage, the stress–strain curve of plain rubberized concrete (S0G0) descends sharply, showing the hallmark of brittle fracture. In contrast, the fiber-reinforced mixtures, particularly the hybrid steel–glass fiber combination (S1.2G0.4), exhibit a considerably longer and more gradual post-peak descending segment. This suggests that beyond peak stress, the steel and glass fibers jointly carry part of the load through combined tensile and bridging mechanisms, mitigating rapid crack propagation and overall specimen collapse, thus improving material toughness and post-failure integrity.

3.5. Energy Dissipation

To quantitatively evaluate the energy absorption capability of the material under impact loads, the impact toughness Rp was adopted as the key metric. Rp is defined as the area enclosed between the dynamic stress–strain curve and the strain axis from the onset of loading up to the peak stress, corresponding to the energy absorbed per unit volume before failure. This metric emphasizes the material’s energy dissipation before macroscopic failure, providing an effective measure of its resistance to impact damage during the damage accumulation phase. The calculation of Rp is performed by numerically integrating the stress–strain curve up to the peak stress, and it is expressed as:

In the equation, σ(ε) represents the dynamic stress–strain function, and ε_“peak” is the strain corresponding to the peak stress.

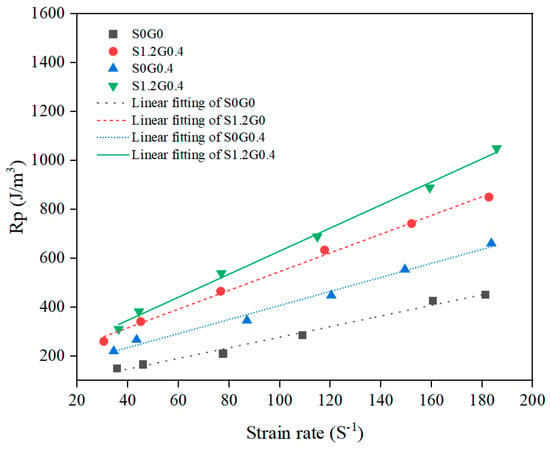

Figure 10 illustrates the relationship between the impact toughness (Rp) and strain rate for the four mix proportions. The corresponding fitted relationship is given by Equation (8).

Figure 10.

Relationship between peak toughness and strain rate.

Similar to Equation (6), a represents the slope of the fitted curve, indicating the sensitivity of energy absorption to the strain rate. The fitted equations for each mix proportion are summarized in Table 7. The plain rubberized concrete (S0G0) exhibits the lowest slope (2.17) in the fitted Rp–strain rate line, suggesting a relatively limited increase in energy absorption with strain rate. With the addition of fibers, not only did Rp increase at the same strain rate, but the slope of its growth also rose substantially. The slopes of single glass fiber (S0G0.4) and single steel fiber (S1.2G0) mixtures increased to 2.87 and 3.83, respectively, showing that fiber incorporation strengthens the material’s ongoing energy dissipation under dynamic loading, with steel fibers providing a more significant enhancement owing to their higher elastic modulus and tensile strength. In the hybrid steel–glass fiber mixture (S1.2G0.4), the slope further increased to 4.71, with Rp consistently being the highest at all tested strain rates. This may indicate that the two fibers create a complementary energy dissipation system during dynamic compression: steel fibers suppress macrocrack development via high-strength bridging, whereas glass fibers, leveraging their excellent dispersion and matrix adhesion, retard damage accumulation at the microcrack scale. Their synergistic interaction extends the time to reach peak stress, substantially improving the material’s total energy dissipation under impact loads.

Table 7.

Fitting results for peak toughness against strain rate.

4. Discussion

Based on the experimental results of this study, the synergistic enhancement mechanism of steel fibers and glass fibers in rubberized concrete is hypothesized to be explained by their multiscale effects and the sequential division of roles during the failure process. Initially, the two fibers form a reinforcing network with complementary physical scales and functions. Steel fibers, with a larger diameter (200 μm) and anchorage at the ends, mainly act at the macroscopic scale to provide bridging, suppressing the formation and propagation of major cracks. Glass fibers, characterized by their fine diameter (14 μm) and high aspect ratio (approximately 857), exhibit these geometric features that result in a large specific surface area, ensuring excellent bonding with the matrix. This allows them to penetrate microregions where steel fibers cannot fully reach and efficiently bridge microcracks at the mesoscopic scale, thus delaying damage initiation. This functional differentiation based on geometric scales also lays the foundation for a complementary mechanical response during the failure process. During the initial loading and stable microcrack propagation stages, glass fibers effectively share stress and dissipate energy due to their strong bonding with the matrix, extensive fiber-matrix interfaces, and relatively high tensile strength (1700 MPa). As the load increases to a critical level, and macroscopic cracks begin to dominate the failure process, steel fibers with higher tensile strength (3000 MPa) become crucial for resisting crack propagation and providing residual bearing capacity. Their bridging and pull-out processes absorb significant amounts of impact energy. This precise division of roles based on scale and failure stages collaboratively enhances the material’s dynamic strength, toughness, and energy dissipation capacity. Furthermore, this hybrid system significantly enhances the material’s sensitivity to strain rate, as demonstrated by the mixed-fiber group exhibiting the highest dynamic strength growth factor.

Regarding the role of fiber hybridization and rubber synergy in further enhancing the dynamic compressive performance of concrete, previous studies allow the following inference: Rubber, acting as a flexible phase, absorbs energy via elastic deformation during the early stage of dynamic compression and improves stress transmission and distribution within the concrete, thereby creating a more uniform load-bearing environment for the fiber network [38]. Fibers effectively offset the strength reduction caused by the incorporation of rubber and sustain energy dissipation during the mid-to-late damage stages via multi-scale bridging and pull-out mechanisms. Together, they establish a time-sequenced complementary energy dissipation, thereby further improving the concrete’s resistance to impact-induced failure. Additionally, incorporating fibers permits simultaneous toughening and strengthening at a suitable rubber content (e.g., 10% in this study), preventing the substantial strength loss associated with excessive rubber addition.

5. Conclusions

Based on the specified mix designs and materials, this study systematically examined, through Split Hopkinson Pressure Bar (SHPB) testing, the dynamic compressive behavior of four rubberized concrete groups—plain (S0G0), steel fiber-reinforced (S1.2G0), glass fiber-reinforced (S0G0.4), and hybrid steel–glass fiber-reinforced (S1.2G0.4)—over a strain rate range of 30–185 s−1. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The incorporation of fibers improves both the dynamic compressive strength and the post-failure fineness modulus of rubber concrete. The steel–glass hybrid fiber group (S1.2G0.4) consistently demonstrates the best dynamic compressive performance across all strain rates (60.25–101.86 MPa), accompanied by a substantially higher post-failure fineness modulus than the other mixtures.

- (2)

- The addition of fibers results in a more pronounced strain-rate sensitivity, as evidenced by the clear increase in the slope of the fitted DIF–log (strain rate) relationship. This trend indicates an accelerated growth rate of DIF with respect to the logarithmic strain rate. Among all mixtures, S1.2G0.4 exhibits the highest DIF growth slope (1.26), demonstrating that the hybrid incorporation of steel and glass fibers is most effective in enhancing strain-rate sensitivity.

- (3)

- The dynamic stress–strain responses reveal that fiber incorporation enhances the initial stiffness, postpones the occurrence of peak stress, and significantly smooths the post-peak softening branch, with the effect being most pronounced for the hybrid fiber-reinforced mixture.

- (4)

- The energy absorption analysis indicates that S1.2G0.4 consistently achieves the highest impact toughness (Rp) across all strain rates and shows the most rapid growth with increasing strain rate. These results confirm that the combined use of steel and glass fibers provides a superior enhancement of energy dissipation capacity in rubber concrete under dynamic compressive loading.

Based on the mix proportions and materials used in this study, the comprehensive analysis reveals that incorporating 1.2% steel fibers and 0.4% glass fibers can further enhance the impact resistance of concrete containing rubber aggregates. This study can serve as a case reference for the design of high-impact resistance materials for protective engineering applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.X. and X.L.; methodology, Z.X.; software, X.W.; validation, J.W. and W.L.; formal analysis, X.W.; investigation, W.L. and X.W.; resources, Z.X.; data curation, J.W. and W.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W.; writing—review and editing, J.W.; visualization, W.L.; supervision, Z.X.; project administration, Z.X. and X.L.; funding acquisition, Z.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the financial support provided by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province under Grant No. 2024B1515020028 (in China).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the School of Civil and Transportation Engineering, Guangdong University of Technology, for providing access to the experimental facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xianpeng Wu is employed by the China West Construction Group 4th (Guangdong) Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ren, G.; Guo, Y.; Shen, A.; Deng, S.; Wu, H.; Pan, H. Dynamic mechanical performance of cellulose fiber concrete under compressive impact loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 493, 143192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Y.; Deng, Y.J.; Liu, L.B.; Zhang, L.H.; Yao, Y. Dynamic mechanical properties and energy dissipation analysis of rubber-modified aggregate concrete based on SHPB tests. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 445, 137920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.; Demartino, C.; Xiao, Y. High-strain rate compressive behavior of Fiber-Reinforced Rubberized Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 319, 125739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moo, J.H.; Chirayath, S.S.; Cho, S.G. Physical protection system vulnerability assessment of a small nuclear research reactor due to TNT-shaped charge impact on its reinforced concrete wall. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2022, 54, 2135–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Feng, W.; Chen, Z.; Nong, Y.; Guan, S.; Sun, J. Fracture behavior of a sustainable material: Recycled concrete with waste crumb rubber subjected to elevated temperatures. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 318, 128553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehdezi, P.K.; Erdem, S.; Blankson, M.A. Physico-mechanical, microstructural and dynamic properties of newly developed artificial fly ash based lightweight aggregate–Rubber concrete composite. Compos. Part B Eng. 2015, 79, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.M.; El-Feky, M.S.; Kohail, M.; Nasr, E.-S.A.R. Performance of geopolymer concrete containing recycled rubber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 207, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmonem, A.; El-Feky, M.S.; Nasr, E.-S.A.R.; Kohail, M. Performance of high strength concrete containing recycled rubber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 227, 116660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.M.; Chen, W.; Khan, A.M.; Hao, H.; Elchalakani, M.; Tran, T.M. Dynamic compressive properties of lightweight rubberized concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 238, 117705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atahan, A.O.; Yücel, A.O. Crumb rubber in concrete: Static and dynamic evaluation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 36, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roychand, R.; Gravina, R.J.; Zhuge, Y.; Ma, X.; Youssf, O.; Mills, J.E. A comprehensive review on the mechanical properties of waste tire rubber concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 237, 117651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhou, S.; Chen, A.; Feng, L.; Ji, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, S.; Li, K.; Xia, X.; Zhang, Q. Analytical evaluation of stress–strain behavior of rubberized concrete incorporating waste tire crumb rubber. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 141963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, H.R.; Aliha, M.R.M.; Khedri, E.; Mousavi, A.; Salehi, S.M.; Haghighatpour, P.J.; Ebneabbasi, P. Strength and cracking resistance of concrete containing different percentages and sizes of recycled tire rubber granules. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 67, 106033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.J.; Huang, S.Q.; Kuang, Y.D.; Zou, Q.Q.; Wang, L.K.; Fu, B. Rubber concrete reinforced with macro fibers recycled from waste GFRP composites: Mechanical properties and environmental impact analysis. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, L.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, J.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, J.; Pan, Z.; Xiong, Z. A study of the compressive behavior of recycled rubber concrete reinforced with hybrid fibers. Materials 2023, 16, 4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Li, L.; Xu, L.; Huang, H.; Dai, W.; Li, S.; Mai, G. Bond durability of FRP bar-concrete interface under marine exposure: From a comprehensive review to an improved prediction method. Compos. Part B Eng. 2026, 312, 113320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaaghabeik, H.; Shukla, S.K.; Mashaan, N.S. Effects of vertical reinforcement on the shear performance of UHPC deep beams with synthetic and steel fibres. Structures 2025, 76, 109038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaaghabeik, H.; Mashaan, N.S.; Shukla, S.K. Impact of geometrical dimensions on the shear behaviour of UHPC deep beams reinforced with steel and synthetic fibres. Structures 2025, 78, 109260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, C.; Li, Q.; Song, G.; Hu, Y. The synergistic effect of recycled steel fibers and rubber aggregates from waste tires on the basic properties, drying shrinkage, and pore structures of cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 470, 140574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Gao, Y.; Wei, J.; Han, Y.; Chen, X.; Kou, X. Experimental study on mechanical properties and toughness of recycled steel fiber rubber concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Xu, R.; Pan, C.; Li, H. Dynamic stress–strain relationship of steel fiber-reinforced rubber self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 344, 128197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Liu, R.; Liu, J.; Yang, L. Comparative study on the effect of steel and plastic synthetic fibers on the dynamic compression properties and microstructure of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC). Compos. Struct. 2023, 324, 117570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Lin, C.; Ma, W. Mechanical behavior of steel fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete under dynamic triaxial compression. Compos. Struct. 2023, 320, 117161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Huang, L.; Weng, R.; Murong, Y.; Liu, L.; Zeng, H.; Jiang, H. Mechanism of chloride ion transport and associated damage in ultra-high-performance concrete subjected to hydrostatic pressure. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 112, 113700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Liu, L.; Zeng, H.; Zhai, K.; Fu, J.; Jiang, H.; Pang, L. Research on the bond performance between glass fiber reinforced polymer (GFRP) bars and Ultra-high performance concrete(UHPC). J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zong, M.; Li, F.; Wu, J.; Wang, D.; Du, X. Experimental study on the dynamic compression behaviors of steel-polyethylene hybrid fiber reinforced engineered cementitious composites under combined static-dynamic loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 477, 141234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwesabi, E.A.; Abu Bakar, B.; Alshaikh, I.M.; Zeyad, A.M.; Altheeb, A.; Alghamdi, H. Experimental investigation on fracture characteristics of plain and rubberized concrete containing hybrid steel-polypropylene fiber. Structures 2021, 33, 4421–4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwesabi, E.A.; Abu Bakar, B.; Alshaikh, I.M.; Akil, H.M. Experimental investigation on mechanical properties of plain and rubberized concretes with steel-polypropylene hybrid fibre. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 233, 117194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslani, F.; Nejadi, S. Self-compacting concrete incorporating steel and polypropylene fibers: Compressive and tensile strengths, moduli of elasticity and rupture, compressive stress–Strain curve, and energy dissipated under compression. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 53, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, W.; Zhou, K.; Wang, J.; Liu, F.; Li, L. Dynamic bending study of glass fiber reinforced seawater and sea-sand concrete incorporated with expansive agents. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 358, 129415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, H.; Xiong, Z.; Song, Y.; Li, L.; Qiu, Y.; Zou, X.; Chen, B.; Chen, D.; Liu, F.; Ji, Y. Early mechanical performance of glass fibre-reinforced manufactured sand concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 83, 108440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C39-2023; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. Astm-International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- Wang, L. Foundations of Stress Waves; Elsevier: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Khosrevani, M.R.; Weinberg, K. A review on split Hopkinson bar experiments on thedynamic characterisation of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 190, 1264–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Li, Y.; Lai, Z.; Zhou, H.; Qin, J.; Wen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, R. Size effect of concrete based on split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) test. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 441, 137499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T14684-2022; Sand for Construction. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Chen, X.; Wu, S.; Zhou, J. Experimental and modeling study of dynamic mechanical properties of cement paste, mortar and concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, S.; Liu, F.; Yang, F.; Li, H.; Chen, D.; Xu, K.; Zhang, H.; Kuang, J.; Fang, Z.; Feng, W. Dynamic compressive and splitting tensile characteristics of rubber-modified non-autoclaved concrete pipe piles. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 69, 106292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.