Binder-Free Earth-Based Building Material with the Compressive Strength of Concrete

Abstract

1. Introduction

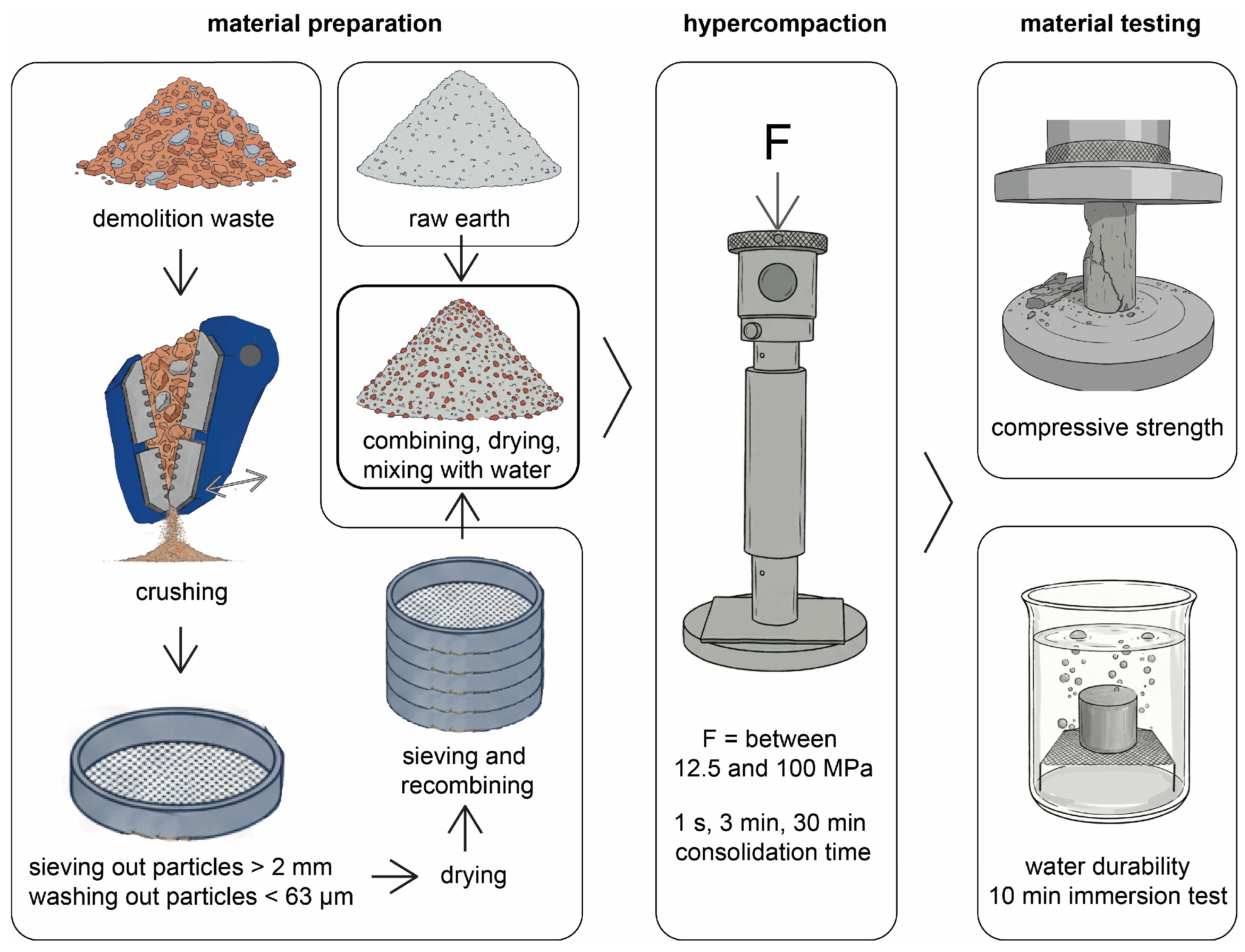

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

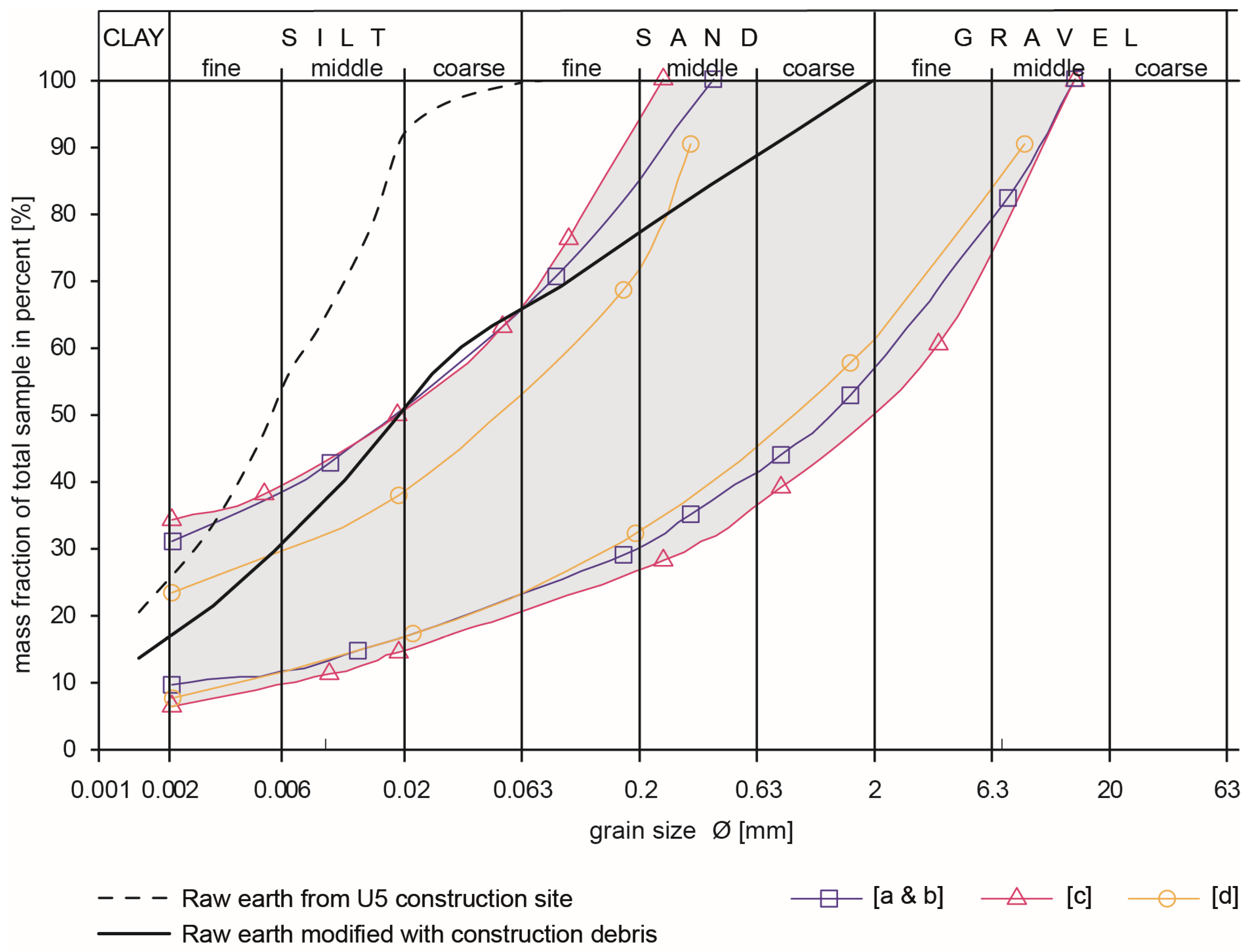

Raw Material Characterization and Modification

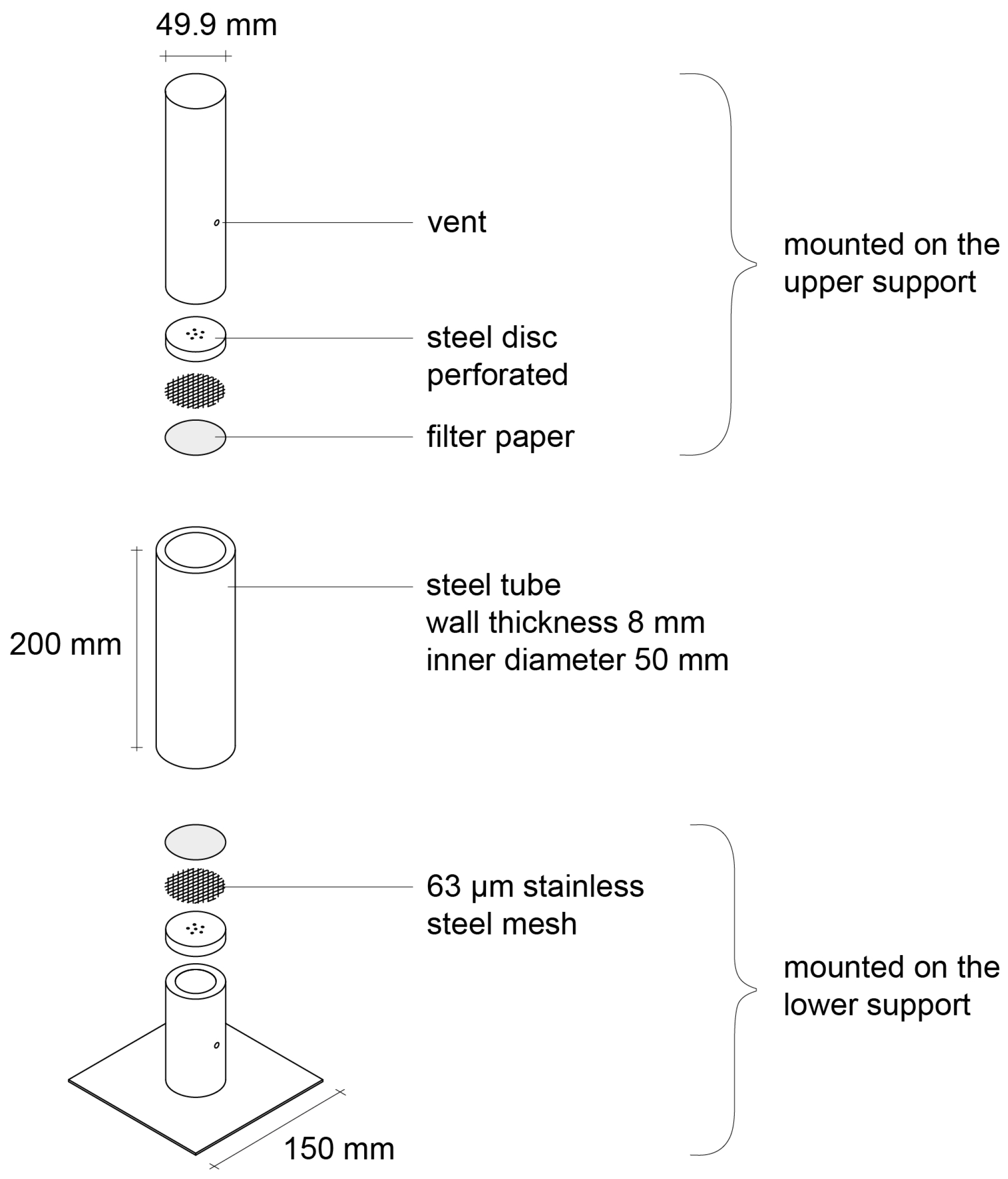

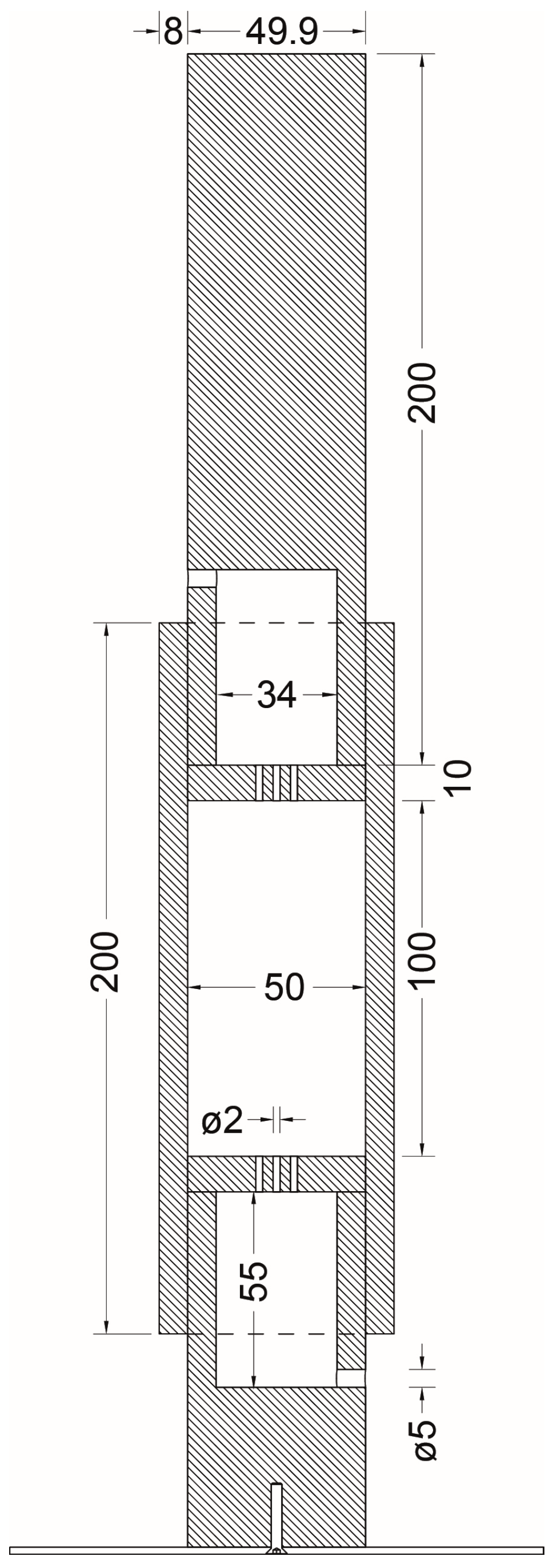

2.2. Methods

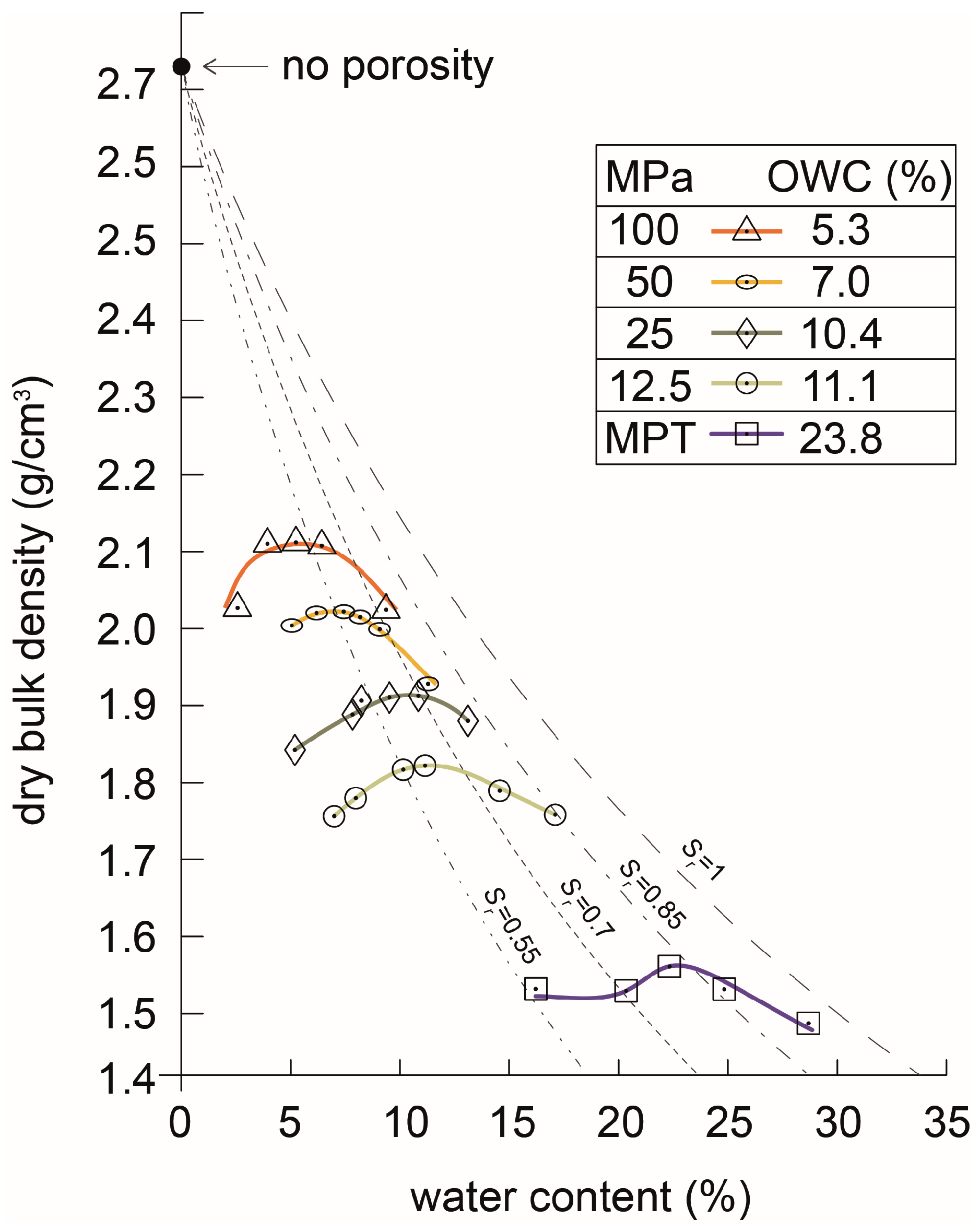

2.3. Determining the Optimum Water Content (OWC)

2.4. Determining the Compressive Strength

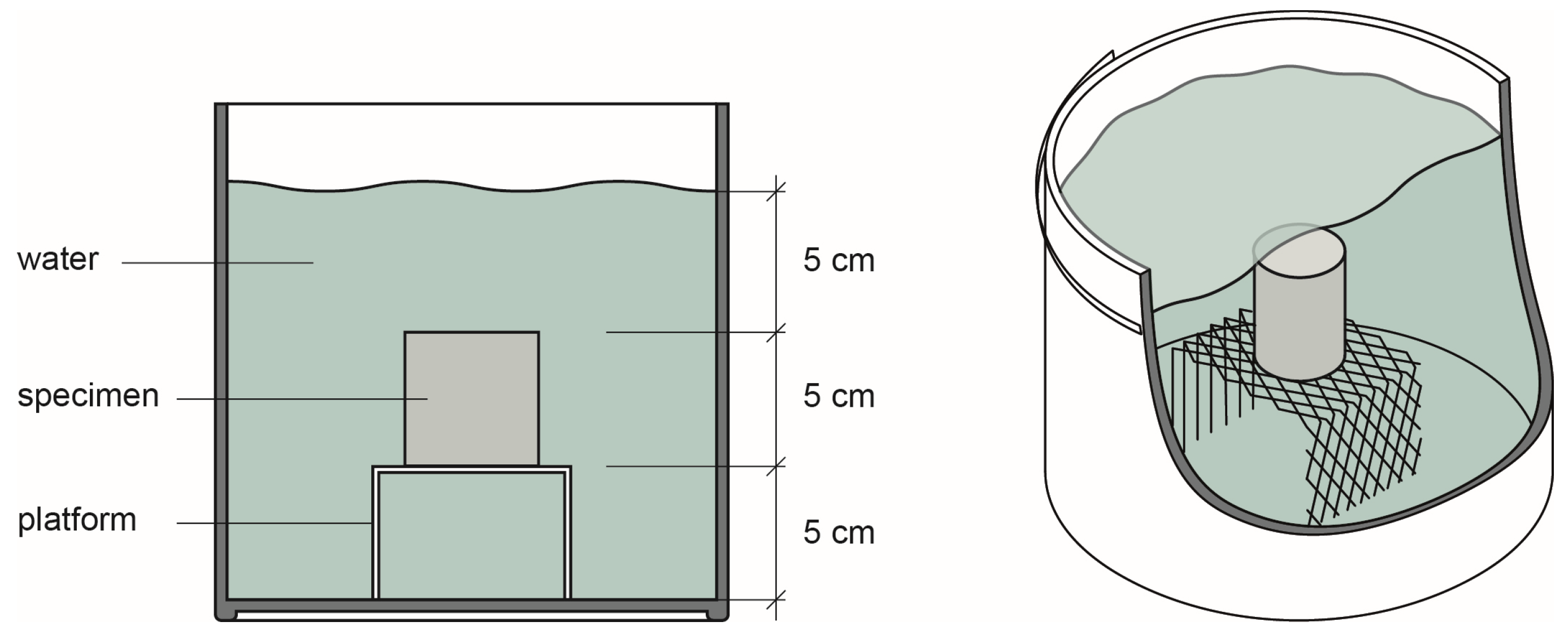

2.5. Determining the Water Durability

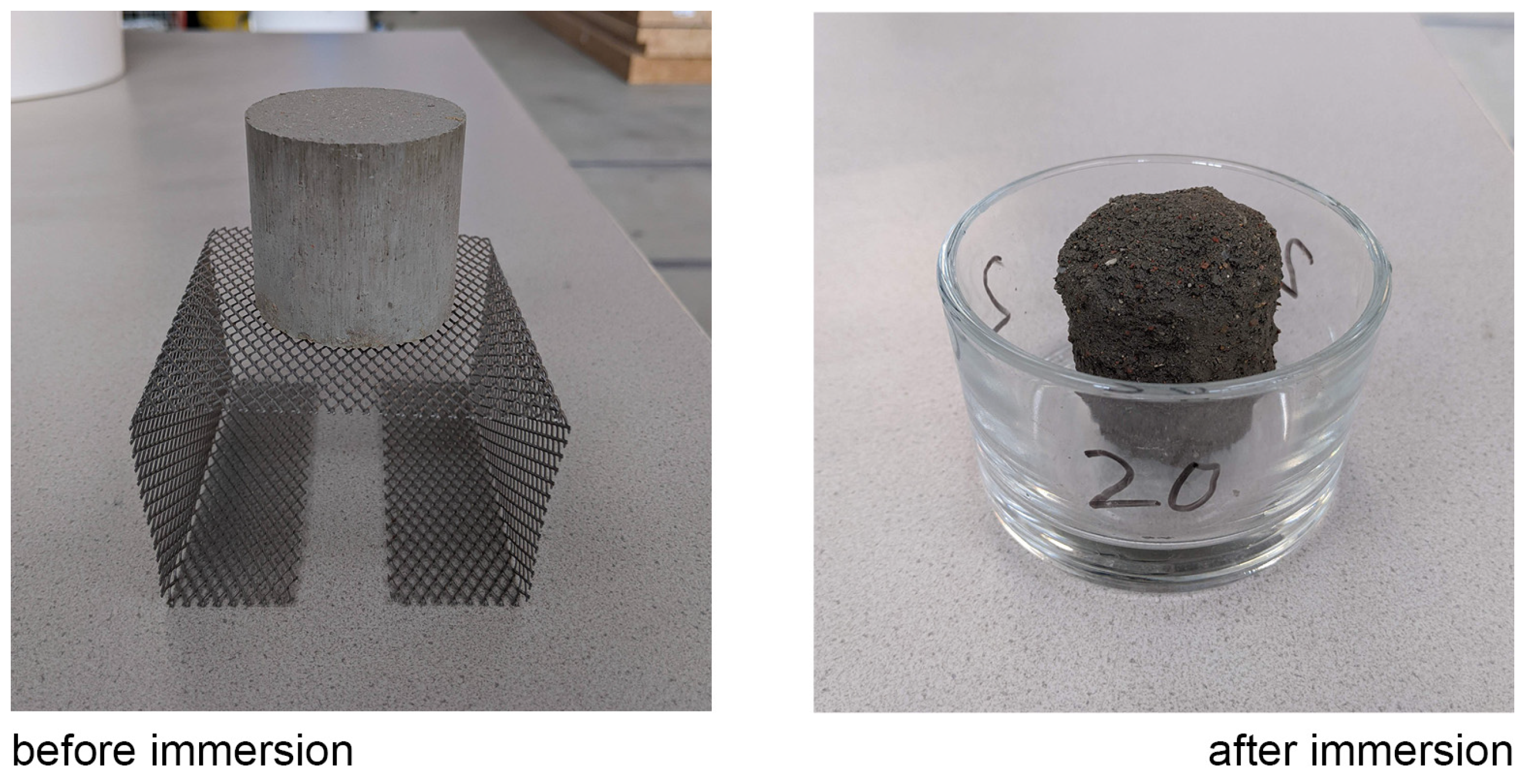

3. Results

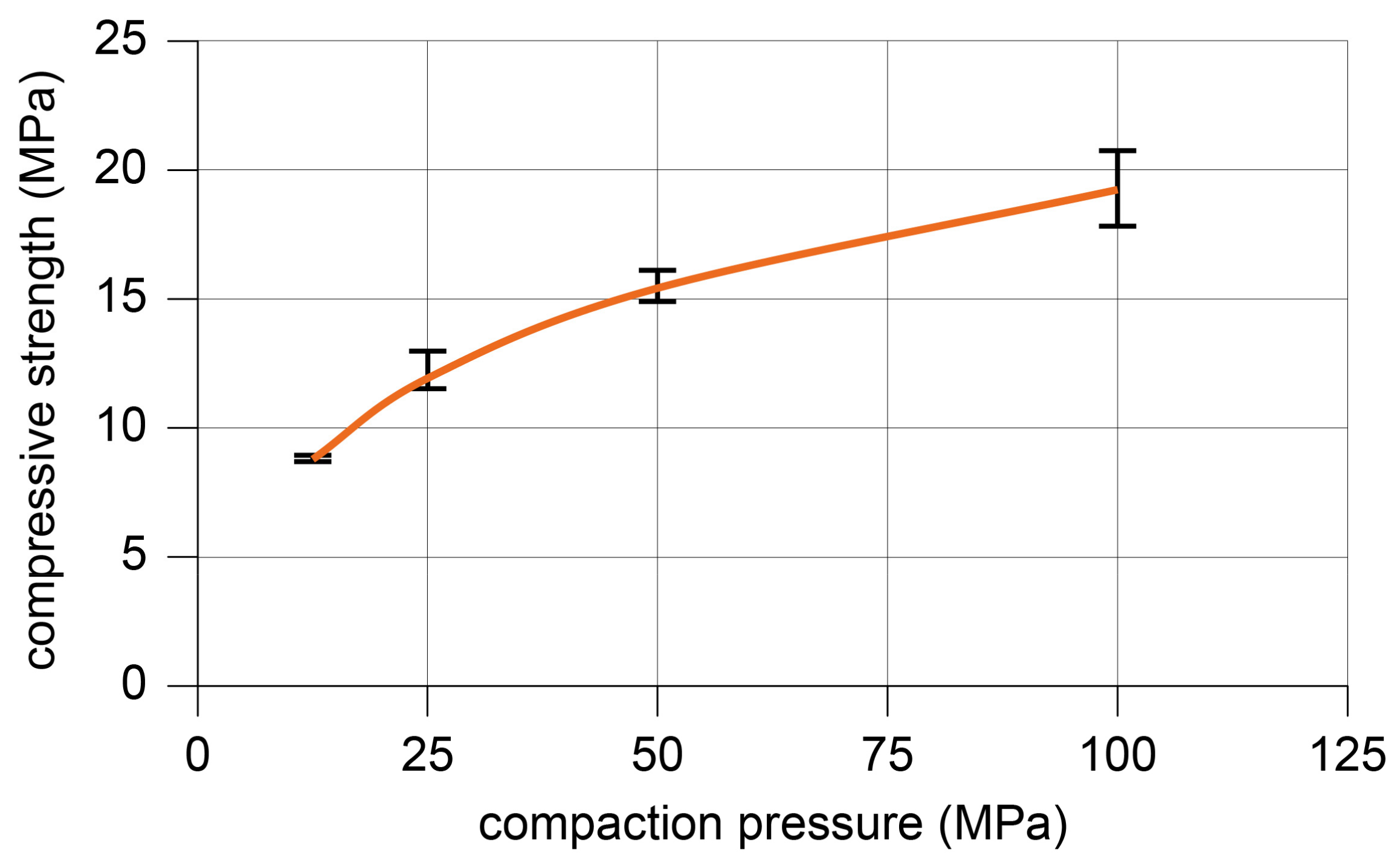

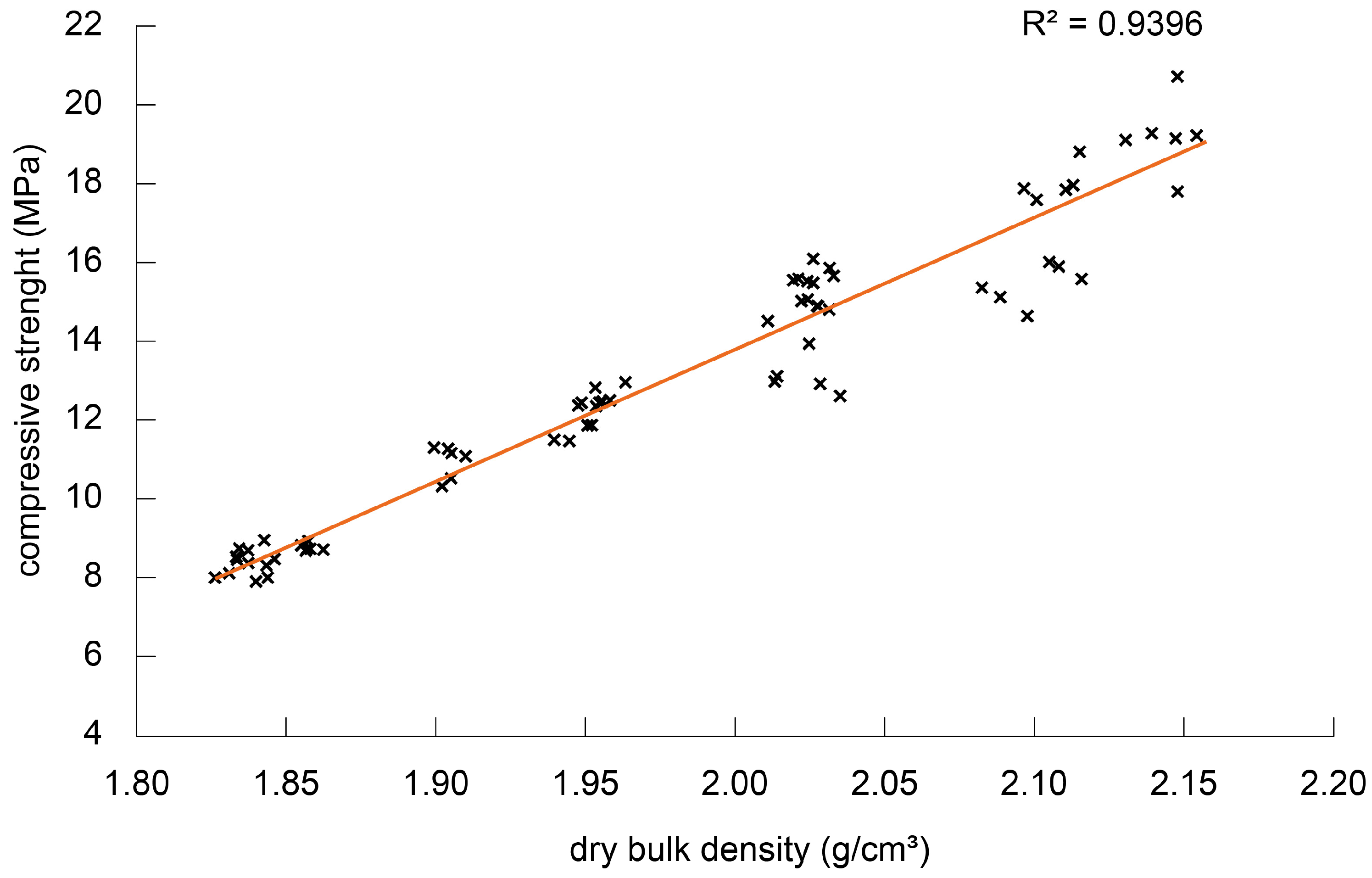

3.1. Effect of Pressure on Compressive Strength

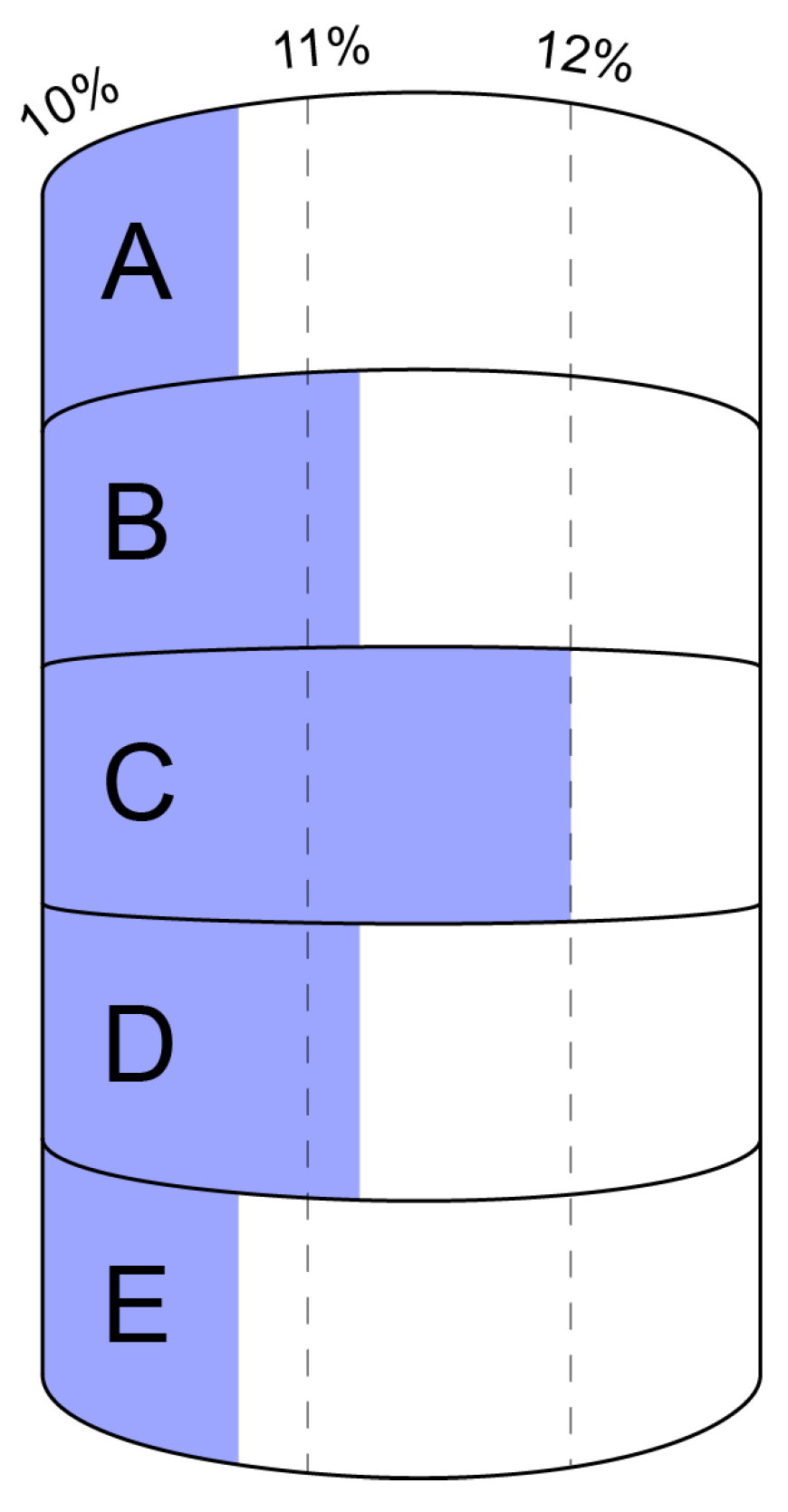

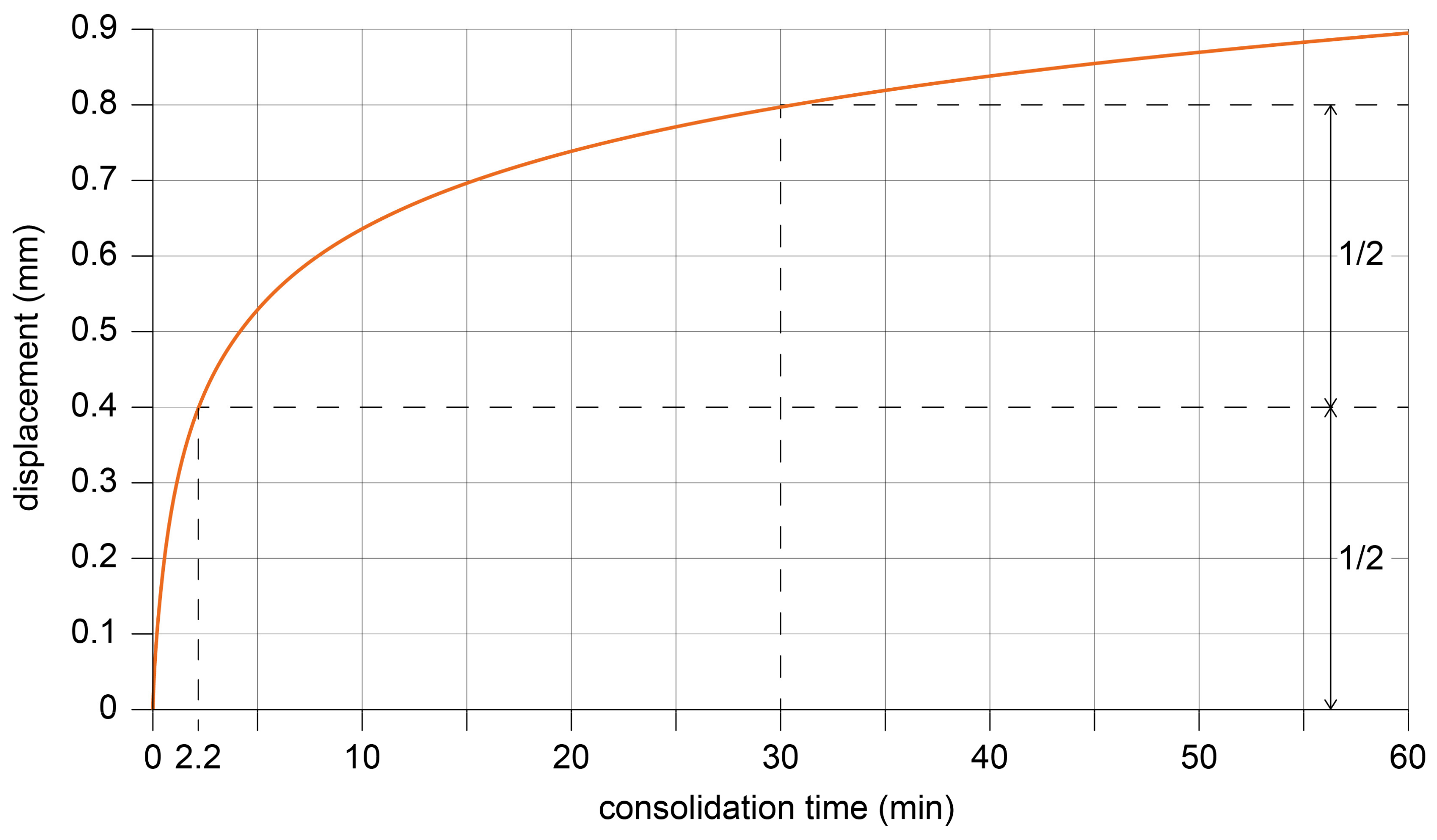

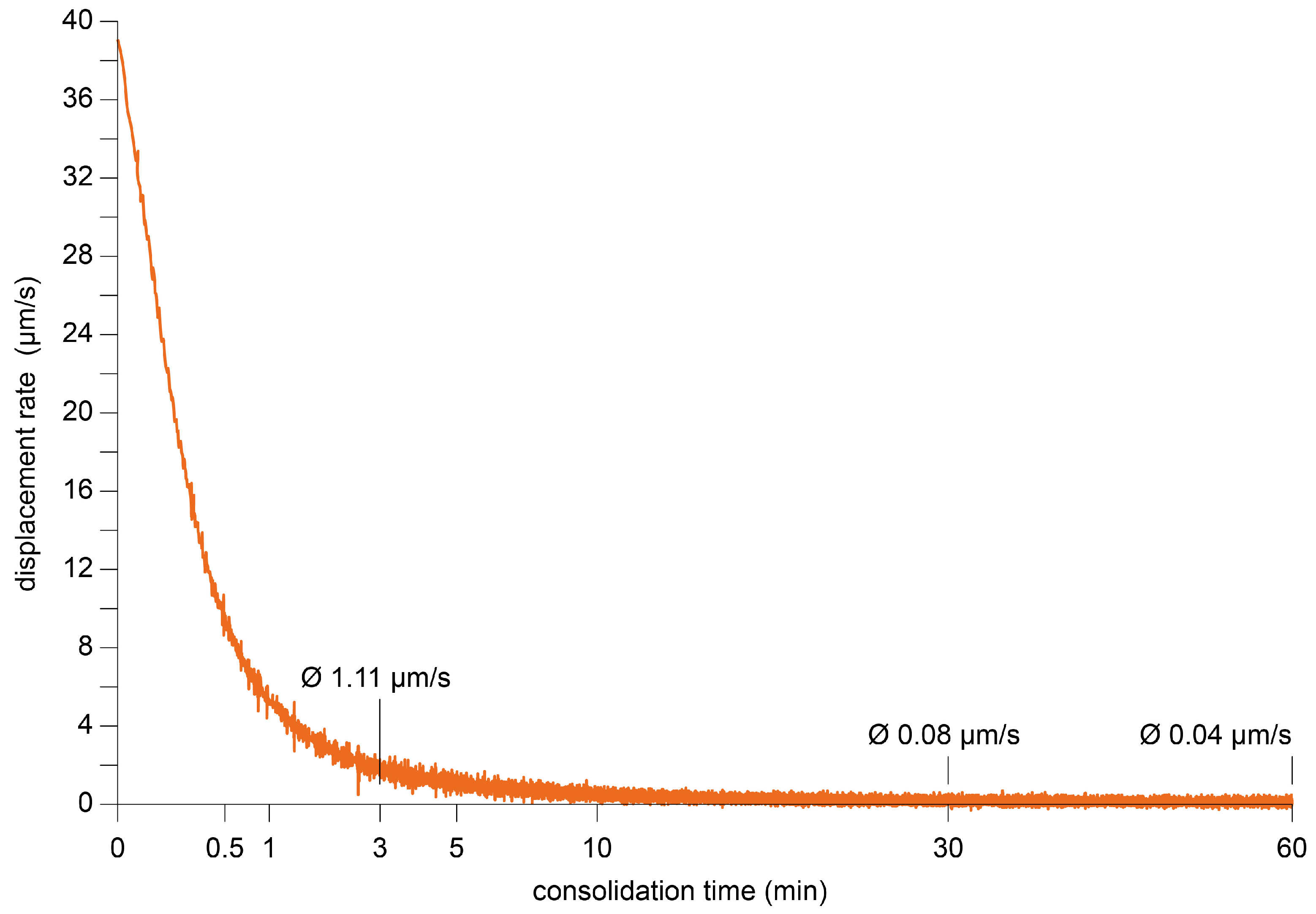

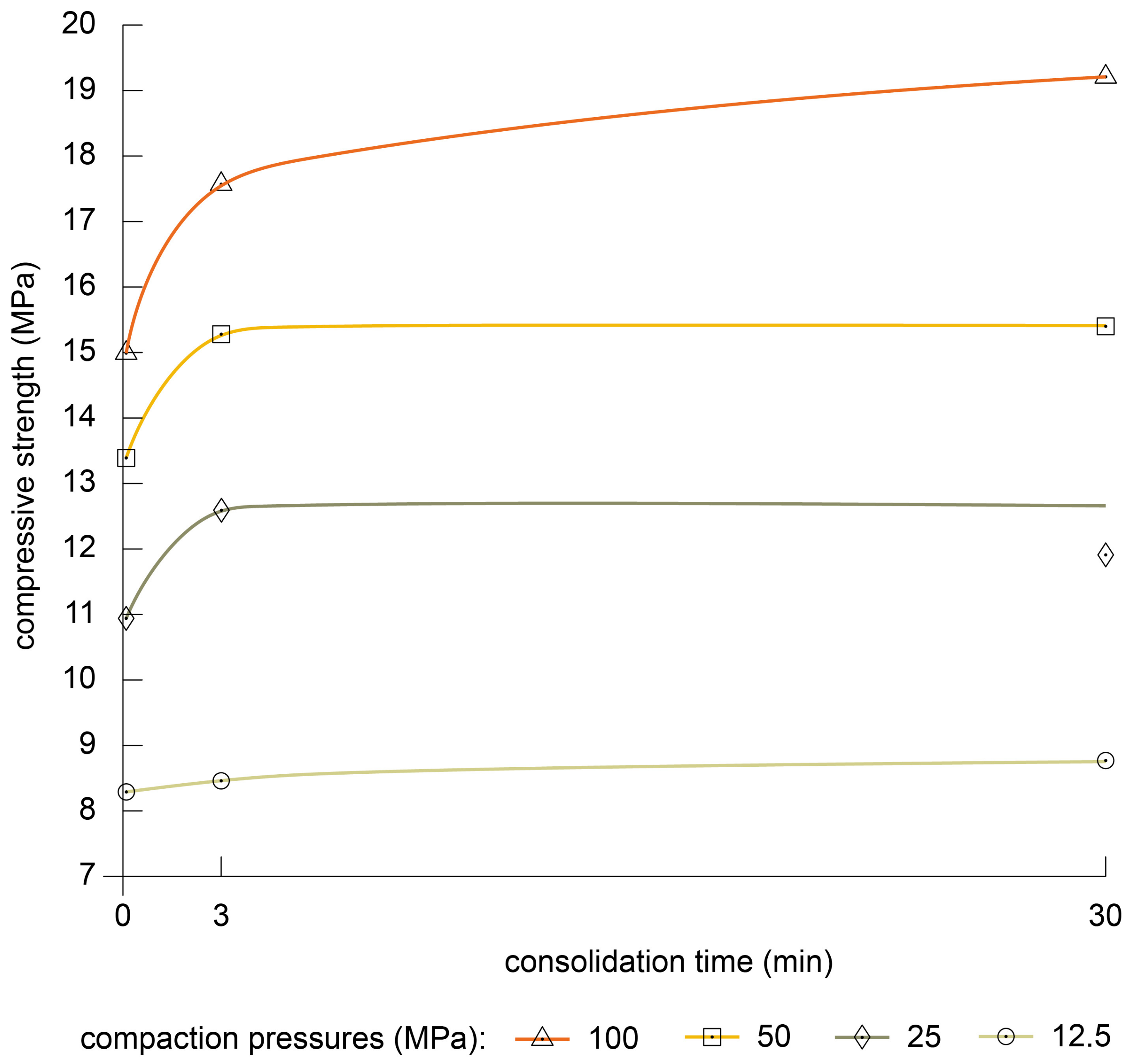

3.2. Effect of Consolidation Time on Compressive Strength

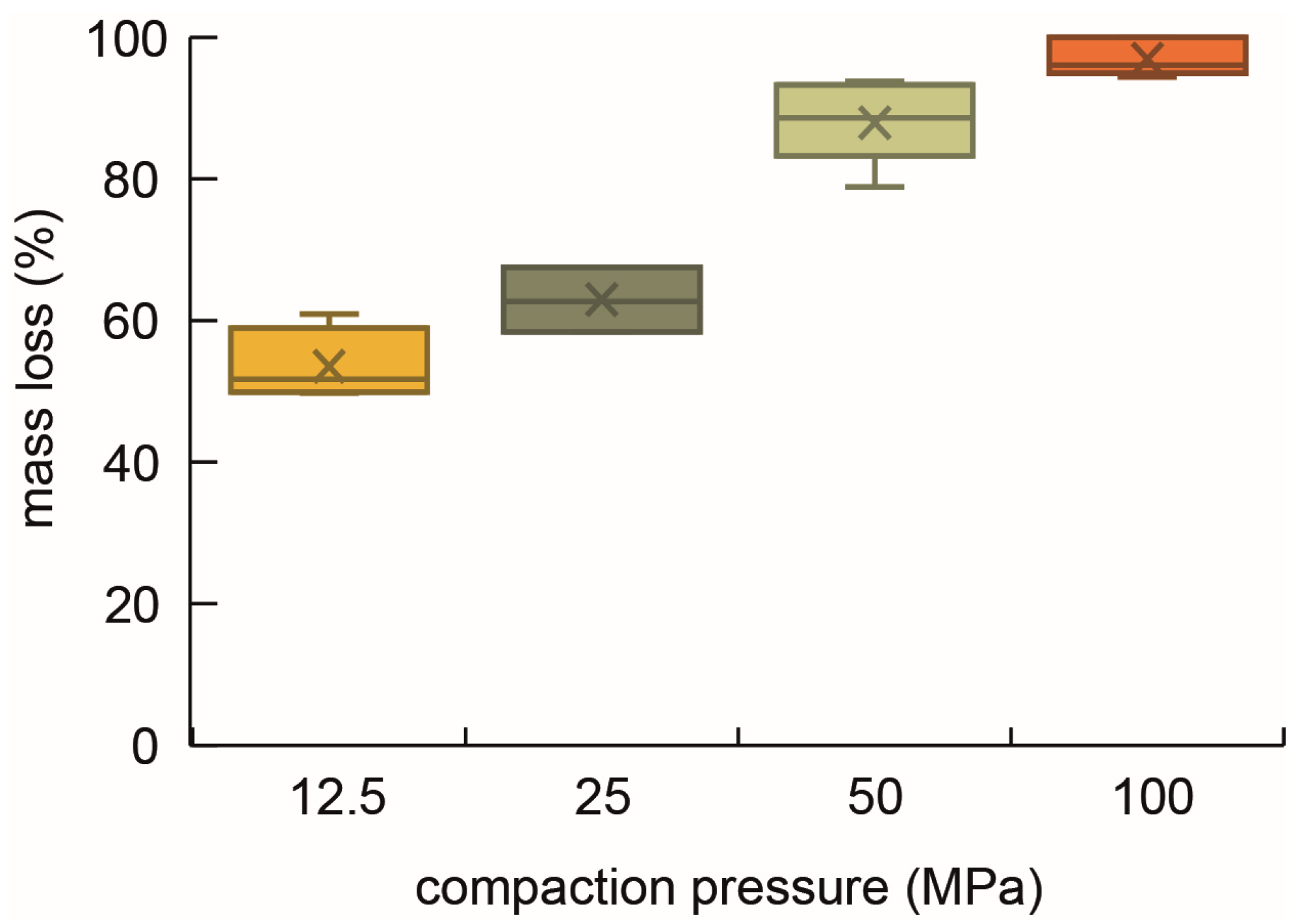

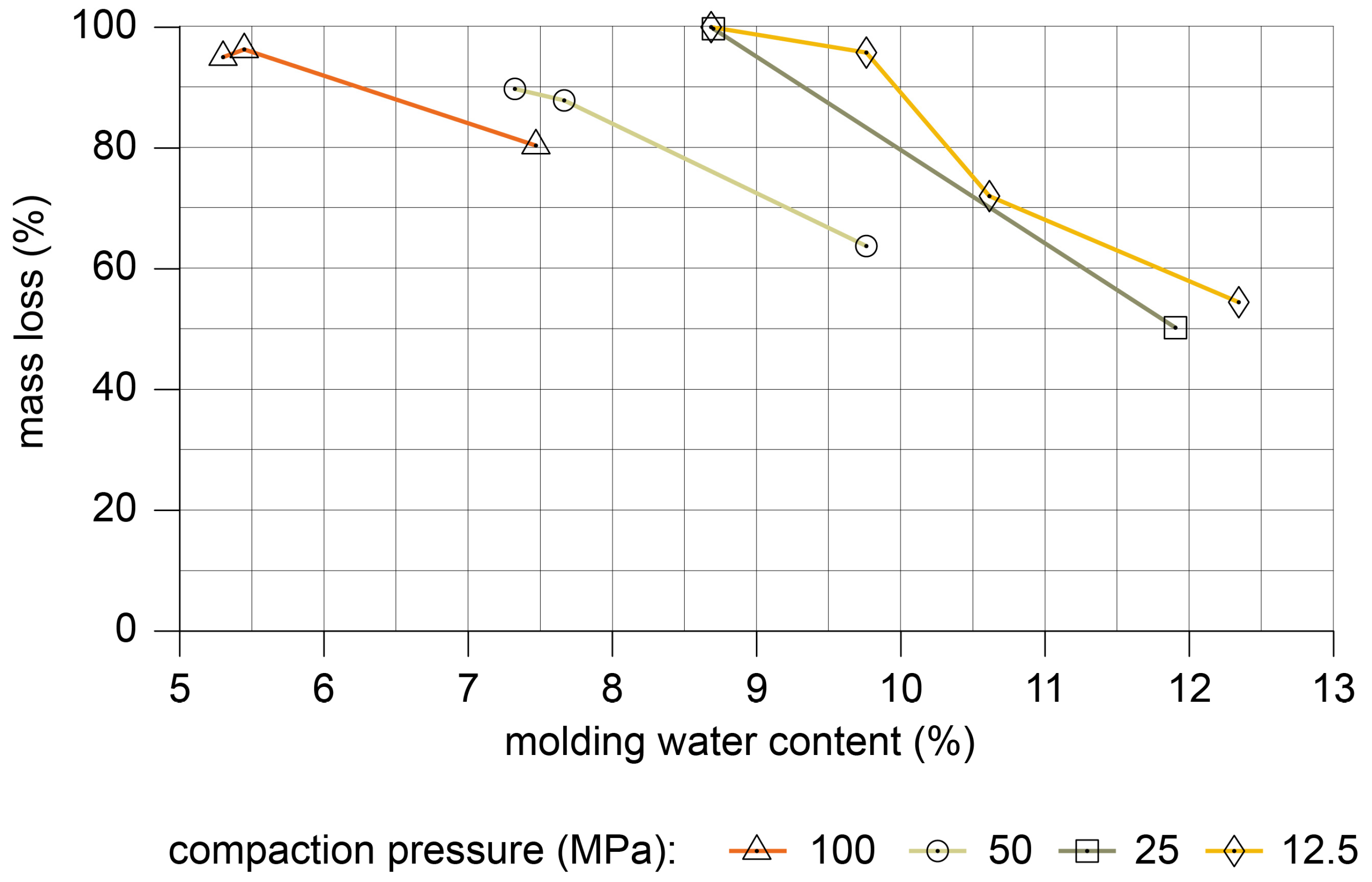

3.3. Effect of Compaction Pressure on Water Durability

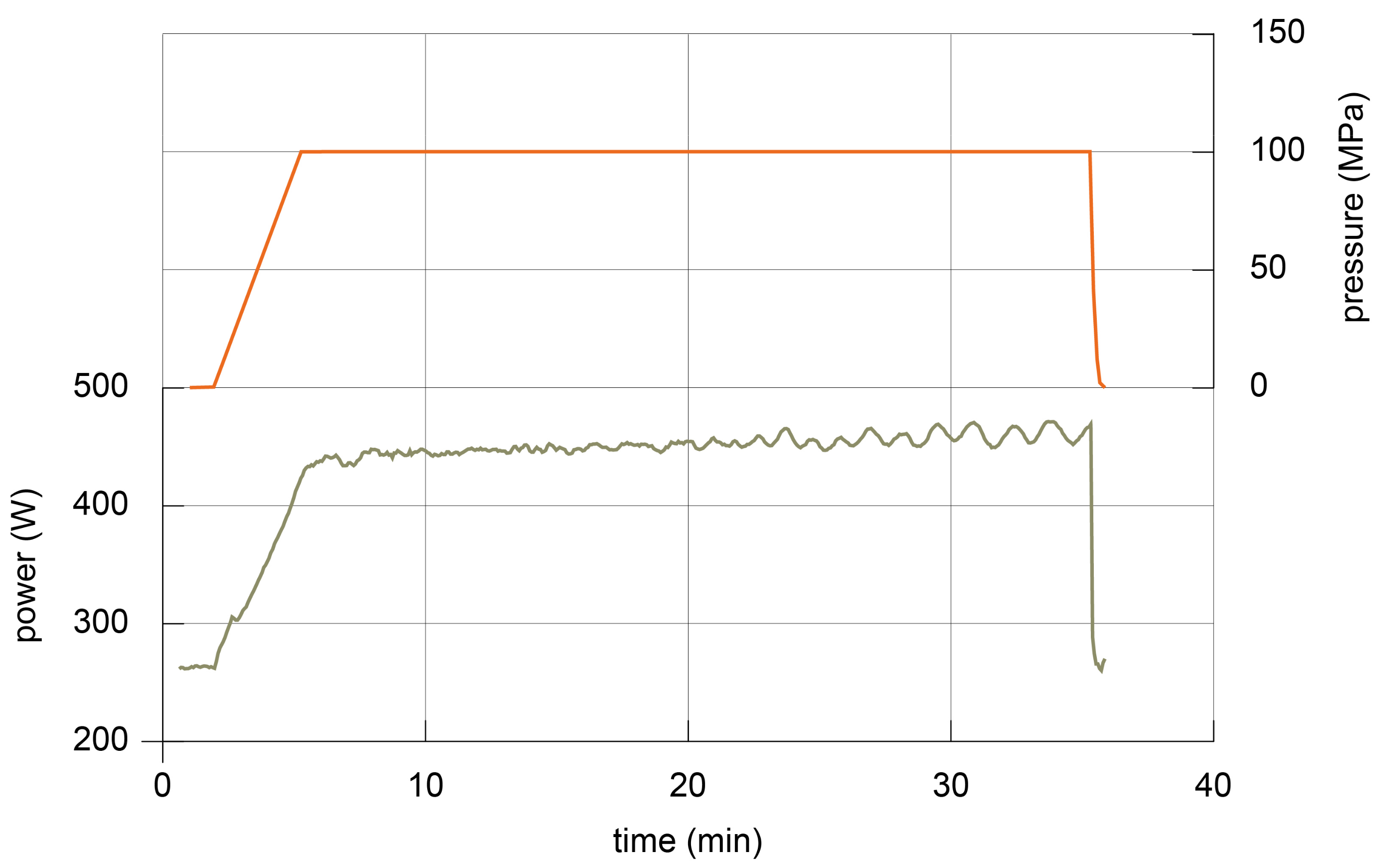

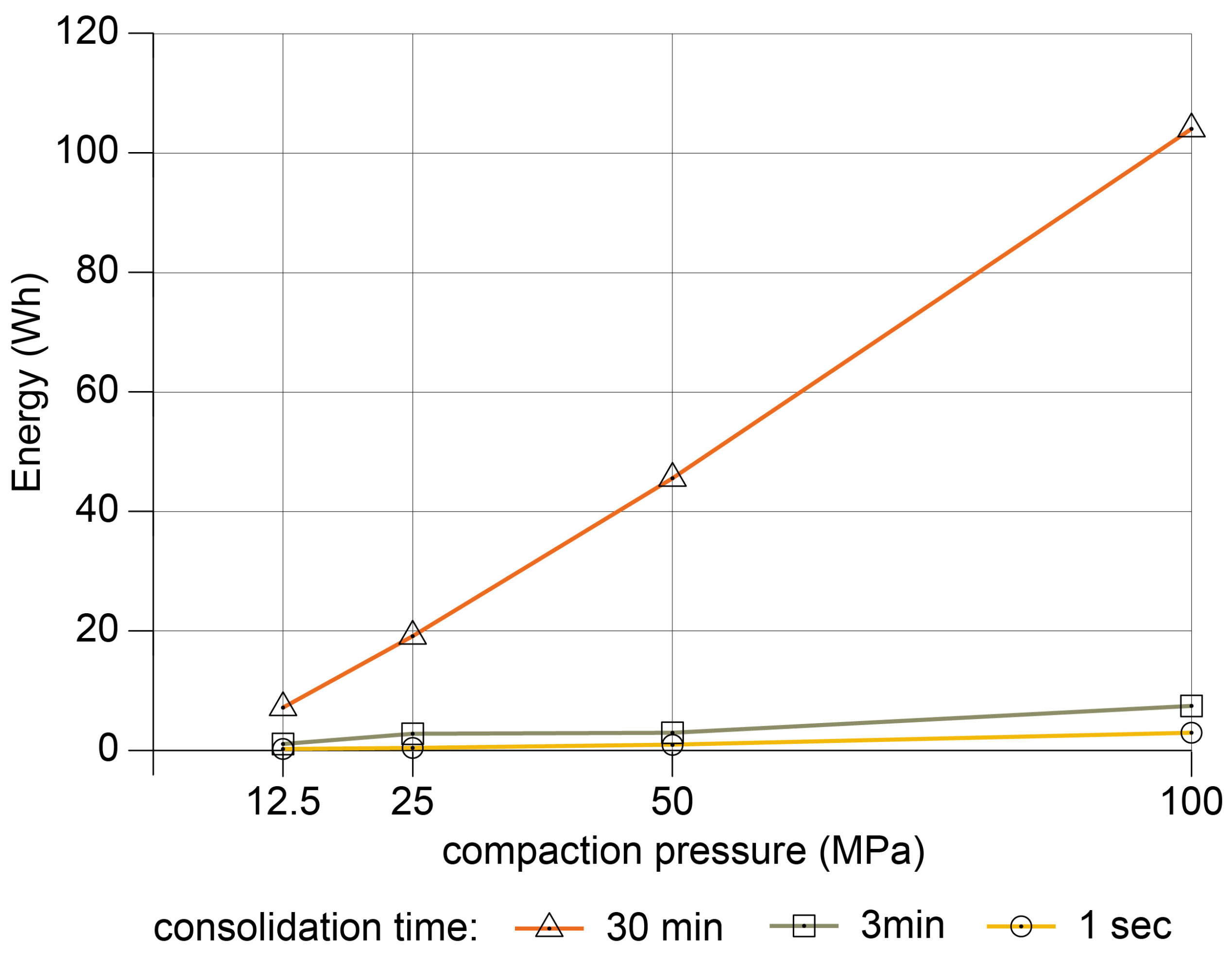

3.4. Influence of Consolidation Time and Compaction Pressure on Energy Consumption

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The results of this study suggest that the compressive strength of a recycled material could be greatly enhanced by compaction at elevated pressures of up to 100 MPa.

- The experiments showed that specimens compacted at 100 MPa for 30 min achieved a compressive strength of 19.2 MPa, which is significantly more than conventional CEB.

- Furthermore, longer consolidation times are beneficial for reaching greater strength, particularly at higher compaction pressures. However, long consolidation times may hinder industrial production, making the increase in the pressure more feasible.

- Moreover, the observed increase in density resulting from longer consolidation was accompanied by a significantly higher energy input. Energy consumption during long consolidation times is no longer proportional to the gained strength. Consequently, it seems more practical to enhance compaction pressure rather than extending consolidation time.

- Within the scope of this study, a consolidation time of 3 min was found to be most effective in terms of compressive strength, as a substantial part of the consolidation had already occurred by then. The specimens that were compacted for 3 min at 100 MPa achieved a compressive strength of 17.6 MPa.

- Despite the significant improvements in compressive strength, the water durability of the material with a smectite rich clay fraction remained limited. In fact, the water durability in an immersion test decreased with increasing compaction pressure.

- Nevertheless, a molding water content on the wet side of the optimum led to an improvement in water durability, which might be ascribed to the microstructure of the material and the organization of the clay platelets. These observations should be further investigated in future studies to better understand the mechanisms and optimize the properties of hypercompacted earth materials in relation to water.

- However, improved water durability has been associated with higher water content during compaction. At the same time, the higher MWC resulted in an uneven water distribution, potentially leading to a heterogeneous porosity within the compact. Future research should explore these relationships in greater depth, with emphasis on more efficient drainage during compaction.

- According to a classification based on DIN 18945 [36], the compacted earth material examined in this study is only suitable for interior walls or applications with rigorous structural weather protection due to its limited water resistance.

- All attempts to test mixtures with higher MWC than was used in this study were unsuccessful, mainly due to material entering between the pistons and mold, which resulted in numerous complications.

- From a sustainability perspective, the study highlights the great environmental and technical potential of this approach. Additionally, the exclusive use of recycled materials, excavation debris and processed demolition waste, supports the principles of a circular economy in construction.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Environment Programme. Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction 2024/2025: Not Just Another Brick in the Wall–The Solutions Exist; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya; Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roswag, E. Lehm und Naturbaustoffe. In Building the Future: Maßstäbe des Nachhaltigen Bauens; Drexler, H., Ed.; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 221–235. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, H. Sustainable Building with Earth, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing Imprint: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, R.; Benazzoug, M.; Kenai, S. Performance of compacted cement-stabilised soil. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2004, 26, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losini, A.; Grillet, A.; Bellotto, M.; Woloszyn, M.; Dotelli, G. Natural additives and biopolymers for raw earth construction stabilization—A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 304, 124507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B.; Latha, M.S. Influence of soil grading on the characteristics of cement stabilised soil compacts. Mater. Struct. 2014, 47, 1633–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, M.; Kapfinger, O.; Sauer, M. Refined Earth: Construction & Design with Rammed Earth, 3rd ed.; DETAIL: München, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Streit, E.; Liberto, T.; Kirchengast, I.; Korjenic, A. Mechanische Aktivierung von Lehm. Bauphysik 2023, 45, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, A.R.; Azelee, N.I.W.; Zaidel, D.N.A.; Chuah, L.F.; Bokhari, A.; El Enshasy, H.A.; Dailin, D.J. Unleashing the potential of xanthan: A comprehensive exploration of biosynthesis, production, and diverse applications. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 46, 771–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, B.V.V. Compressed Earth Block and Rammed Earth Structures. In Springer Transactions in Civil and Environmental Engineering, 1st ed.; Springer Singapore Pte. Limited: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, A.W.; Gallipoli, D.; Perlot, C.; Mendes, J. Mechanical behaviour of hypercompacted earth for building construction. Mater. Struct. 2017, 50, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muguda, S.; Lucas, G.; Hughes, P.; Augarde, C.; Cuccurullo, A.; Bruno, A.W.; Perlot, C. Advances in the Use of Biological Stabilisers and Hyper-compaction for Sustainable Earthen Construction Materials, in Earthen Dwellings and Structures. In Springer Transactions in Civil and Environmental Engineering; Walker, P., Reddy, B.V.V., Mani, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuccurullo, A.; Gallipoli, D.; Bruno, A.W.; Augarde, C.; Hughes, P.; La Borderie, C. Influence of particle grading on the hygromechanical properties of hypercompacted earth. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 2019, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabalar, A.F.; Abdulnafaa, M.D.; Karabash, Z. Influences of various construction and demolition materials on the behavior of a clay. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, R.; Gaupp, R. Diagenese Klastischer Sedimente, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minke, G. Building with Earth: Design and Technology of a Sustainable Architecture Fourth and Revised Edition, 4th ed.; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigert, M.; Melnyk, O.; Winkler, L.; Raab, J. Carbon Emissions of Construction Processes on Urban Construction Sites. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiglstorfer, H. Earth Construction & Tradition: Vol 2; IVA-Verlag: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier, S.; Paris, J.-C. Dossier de Presse Cycle Terre. Sevran. September 2018. Available online: https://www.cycle-terre.eu/files/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/dossier-presse-ct-2018_oklight.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Weleda Ges.m.b.H. Europas größte Lehmbaustelle: Der Weleda Logistik-Campus. Schwäbisch Gmünd. 5 March 2024. Available online: https://www.weleda.at/footer/dialog/presseartikel/europas-groesste-lehmbaustelle (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Harzhauser, M.; Hofmann, T. Wien am Sand: Von Prinz Eugen und der Seekuh in Ottakring: Eine Zeitreise Durch die Geologische Vergangenheit Wiens; Naturhistorisches Museum Wien: Wien, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Maniatidis, V.; Walker, P. A review of rammed earth construction. In Innovation Project “Developing Rammed Earth for UK Housing”; Natural Building Technology Group, Department of Architecture & Civil Engineering, University of Bath: Bath, UK, 2003; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- AFNOR XP P13-901; Compressed Earth Blocks for Walls and Partitions: Definitions—Specifications—Test Methods—Delivery Acceptance Conditions. AFNOR Association française de normalisation: Saint-Denis La Plaine Cedex, France, 2001.

- CRATerre-EAG; CDI. Compressed Earth Blocks: Standards–Technology Series No.11; Centre for the Development of Industry (CDI): Brussels, Belgium, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- MOPT. Bases Para el Diseño y Construcción con Tapial; MOPT: Madrid, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Houben, H.; Guillaud, H. Earth Construction: A Comprehensive Guide. In Earth Construction Series; ITDG, Intermediate Technology Development Group Publishing: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, J. Building with Earth: A Handbook; ITDG Limited: Rugby, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- DIN EN ISO 17892-4:2016; Geotechnical Investigation and Testing-Laboratory Testing of Soil-Part 4: Determination of Particle Size Distribution. DIN German Institute for Standardization: Berlin, Germany, 2017.

- Bui, Q.-B.; Morel, J.-C.; Hans, S.; Walker, P. Effect of moisture content on the mechanical characteristics of rammed earth. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 54, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermer, D.C.; Brehm, E. Mauerwerk-Kalender 2025: Aspekte der Nachhaltigkeit. In Mauerwerk-Kalender 50; Ernst & Sohn, a Wiley Brand: Berlin, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN EN ISO 17892-12:2022-08; Geotechnical Investigation and Testing-Laboratory Testing of Soil-Part 12: Determination of Liquid and Plastic Limits. DIN German Institute for Standardization: Berlin, Germany, 2022.

- DIN EN ISO 14688-2:2020-11; Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Identification and Classification of Soil—Part 2: Principles for a Classification. DIN German Institute for Standardization: Berlin, Germany, 2020.

- Filho, W.L.; Hunt, J.; Lingos, A.; Platje, J.; Vieira, L.W.; Will, M.; Gavriletea, M.D. The Unsustainable Use of Sand: Reporting on a Global Problem. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozzi, V.; Bruno, A.W.; Fabbri, A.; Barbucci, A.; Finocchio, E.; Lagazzo, A.; Brencich, A.; Gallipoli, D. Stabilising compressed earth materials with untreated and thermally treated recycled concrete: A multi-scale investigation. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 423, 138614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasinikota, P.; Tripura, D.D. Evaluation of compressed stabilized earth block properties using crushed brick waste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 280, 122520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN 18945:2024-03; Earth Blocks-Requirements, Test and Labelling. DIN German Institute for Standardization: Berlin, Germany, 2024.

- Bruno, A.W.; Perlot, C.; Mendes, J.; Gallipoli, D. A microstructural insight into the hygro-mechanical behaviour of a stabilised hypercompacted earth. Mater. Struct. 2018, 51, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.-F. Mechanical Properties of Clays and Clay Minerals. In Developments in Clay Science; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 5, pp. 347–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN 18124:2019-02; Soil, Investigation and Testing-Determination of Density of Solid Particles-Wide Mouth Pycnometer. DIN German Institute for Standardization: Berlin, Germany, 2019.

- Bruno, A.W. Hygro-Mechanical Characterisation of Hypercompacted Earth for Building Construction. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour, Pau, France, 2016. Available online: https://univ-pau.hal.science/tel-02366888v1 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Melo, C.; Moraes, A.; Rocco, F.; Montilha, F.; Canto, R. A validation procedure for numerical models of ceramic powder pressing. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 38, 2928–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B.V.V.; Jagadish, K.S. The static compaction of soils. Geotechnique 1993, 43, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Abdelaal, A.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, A.; Fu, Y.; Xie, Y.M. Ultra-compressed earth block stabilized by bio-binder for sustainable building construction. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Pan, Z.; Xiao, T.; Wang, J. Effects of molding water content and compaction degree on the microstructure and permeability of compacted loess. Acta Geotech. 2022, 18, 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, C.H.; Trast, J.M. Hydraulic conductivity of thirteen compacted clays. Clays Clay Miner. 1995, 43, 669–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, Y.B.; Olivieri, I. Pore fluid effects on the fabric and hydraulic conductivity of laboratory-compacted clay. Transp. Res. Rec. 1989, 1219, 144–159. Available online: https://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/trr/1989/1219/1219-014.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2026).

| Grain Size Distribution | ||

| Sand | 0.063–2 mm | <1% |

| Silt | 0.002–0.063 mm | 73.9% |

| Clay | <0.002 mm | 25.8% |

| Plasticity properties | ||

| Liquid limit, wL | 32% | |

| Plastic limit, wP | 22% | |

| Plasticity index, Ip | 10% | |

| Activity index, IA (–) | 0.39 | |

| Density of solid particles | ||

| Gs | 2.73 g/cm3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Amort, S.; Korjenic, A.; Streit, E. Binder-Free Earth-Based Building Material with the Compressive Strength of Concrete. Buildings 2026, 16, 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020340

Amort S, Korjenic A, Streit E. Binder-Free Earth-Based Building Material with the Compressive Strength of Concrete. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):340. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020340

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmort, Simon, Azra Korjenic, and Erich Streit. 2026. "Binder-Free Earth-Based Building Material with the Compressive Strength of Concrete" Buildings 16, no. 2: 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020340

APA StyleAmort, S., Korjenic, A., & Streit, E. (2026). Binder-Free Earth-Based Building Material with the Compressive Strength of Concrete. Buildings, 16(2), 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020340