Lean Framework for Minimizing Construction and Demolition Waste in Zimbabwe

Abstract

1. Introduction

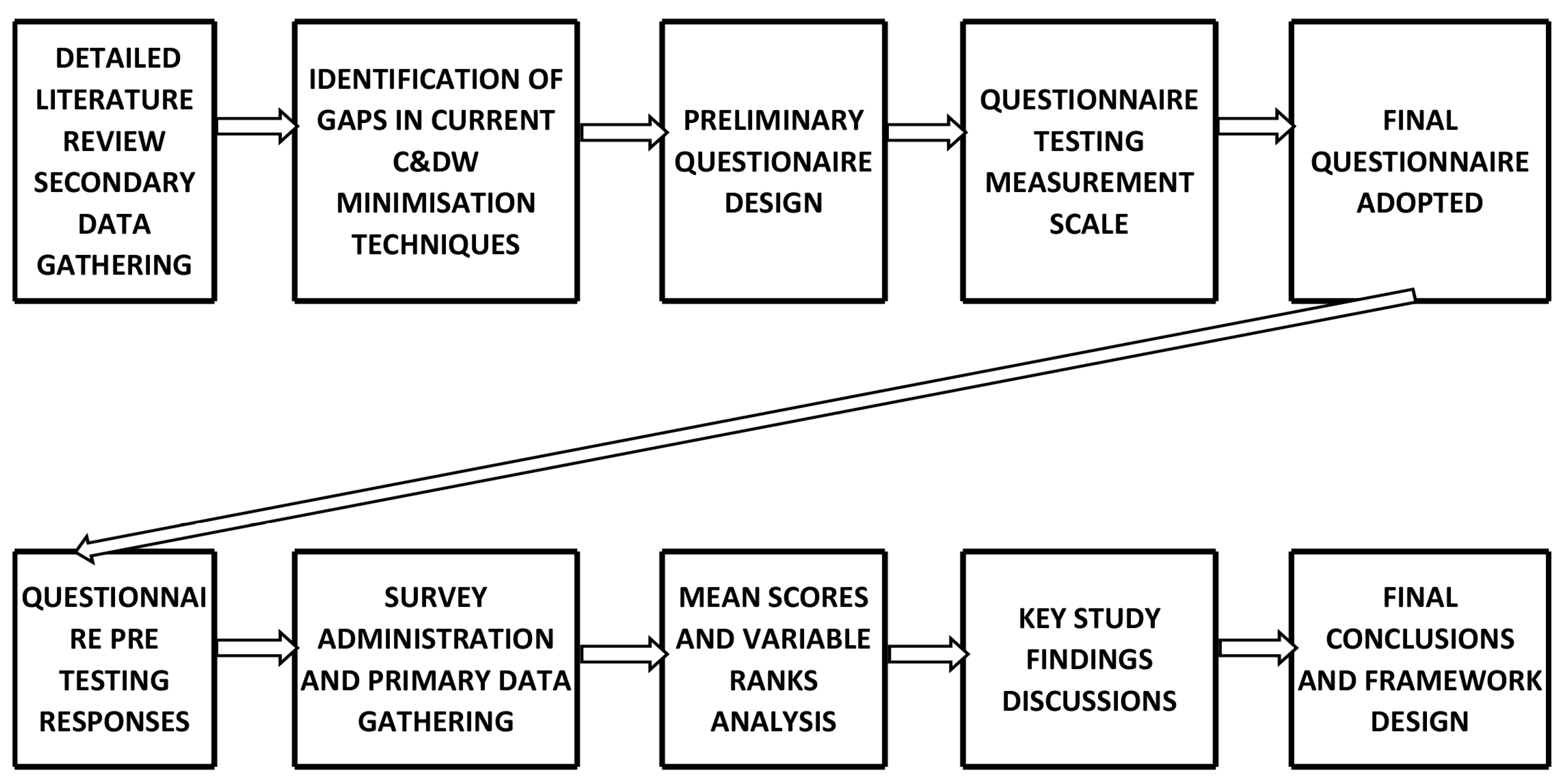

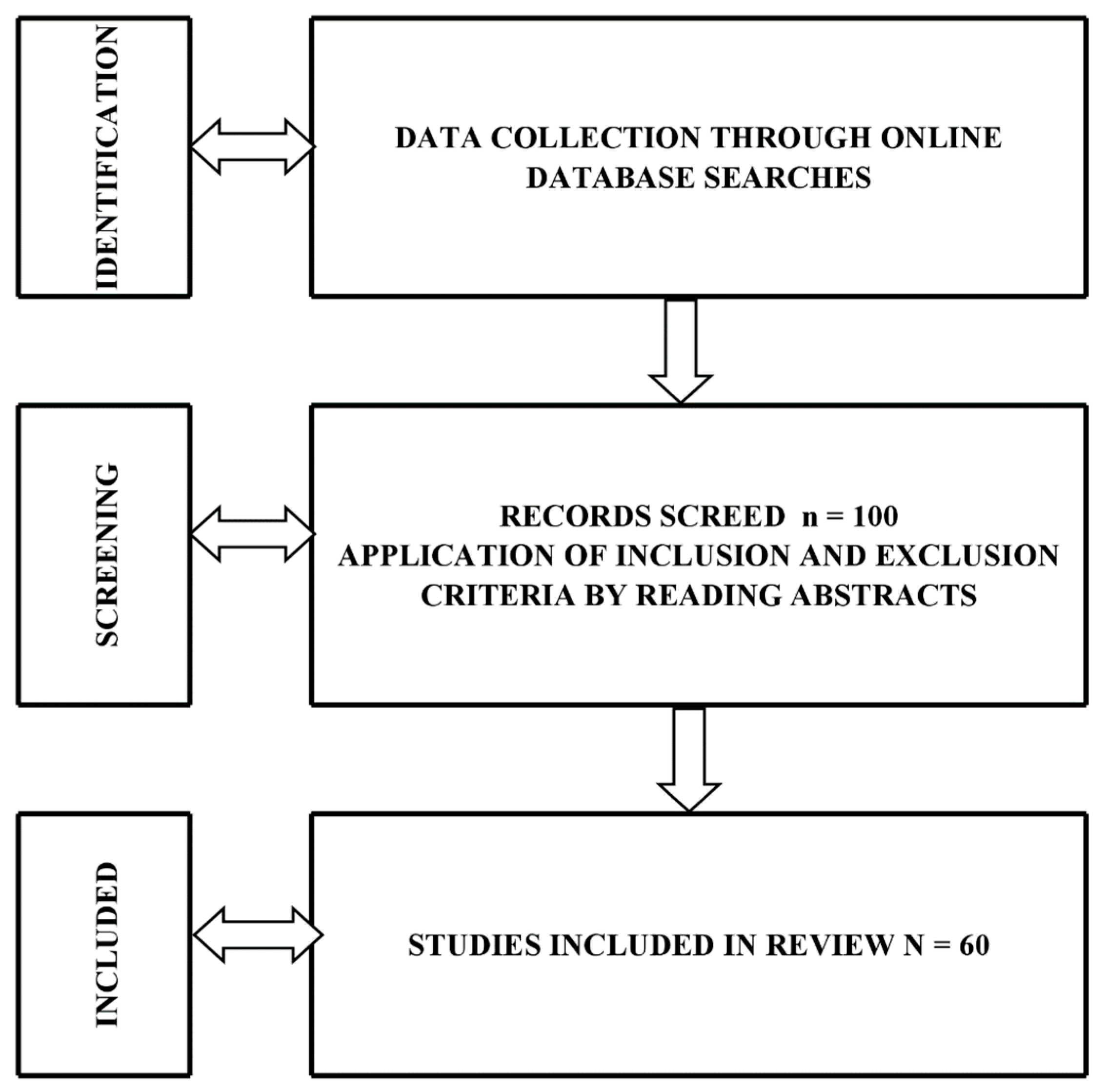

2. Materials and Methods

3. Prior Literature Review

3.1. Gaps in the Current CDW Minimisation Techniques

3.2. Lean Tools and Techniques

4. Survey Design and Administration

4.1. Sampling

4.2. Data Analysis Procedures

5. Results

5.1. Survey Response

5.2. Gaps in CDW Minimisation Practices

5.3. Lean Tools and Techniques

5.3.1. Mean Analysis and Ranking of Lean Techniques

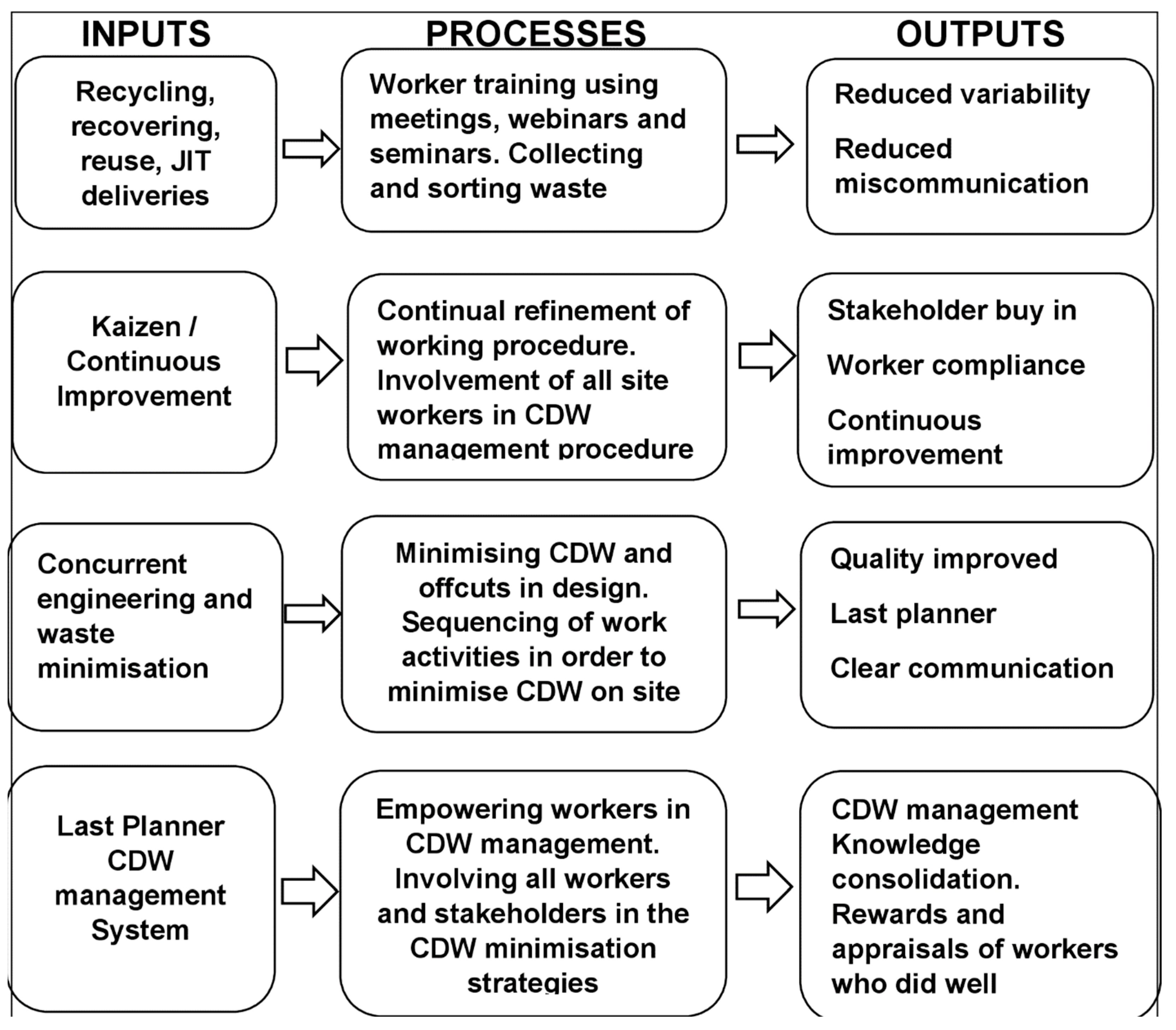

5.3.2. Proposed Lean Framework for Minimising Construction and Demolition Waste in Zimbabwe

6. Discussion

6.1. Step 1: Recycle, Reuse, and Reduce (3Rs)

- Reduce: Reducing CDW from the earliest phases of design may be helpful in the construction sector. The process aims to reduce the environmental impacts of CDW and construction costs. Reducing the materials used minimises resource usage from project inception and reduces transportation work [40,41,42].

- Recycle: Construction material recycling plays an important role in CDW management plans. Recycling is the reprocessing of CDW into usable raw materials or usable products. Recycling extends material life, in addition to reducing construction resource consumption and avoiding CDW disposal costs [43,44].

6.2. Step 2: Continuous Improvement (CI)

- Learning and worker training

- Waste reduction and elimination

- Employee engagement

- Increased productivity

- Continuous improvement in any working environments

- Transparent communication

- Focus on areas of greatest need

- Focus on process improvement

- Prioritising employee improvement

6.3. Step 3: Concurrent Engineering (CE)

- Reduce waste and prepare for change

- Promote re-use, creating a team environment

- Reduce re-works

- Reduce project durations sustaining CE

6.4. Step 4: Last Planner Systems (LPS)

- Phase Scheduling (Pull Planning)

- Weekly Schedule Plans

- Daily Huddle Meetings

- Milestone Planning

- Percent Plan Complete

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shaqour, E.N. The impact of adopting lean construction in Egypt: Level of knowledge, application, and benefits. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, A.H.; Akhund, M.A.; Laghari, A.A.N.; Imad, H.U.; Bhangwar, S.N. Adaptability of lean construction techniques in Pakistan’s construction industry. Civ. Eng. J. 2018, 4, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Hao, J.L.; Qian, L.; Tam, V.W.; Sikora, K.S. Implementing lean construction techniques and management methods in Chinese projects: A case study in Suzhou, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 286, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajjou, M.S.; Chafi, A. Lean construction implementation in the Moroccan industry: Awareness, benefits and barriers. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2018, 16, 533–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaz, M.; Teixeira, J.C.; Rahla, K.M. Construction and demolition waste—A Shift toward lean construction and building information models. In Sustainability and Automation in Intelligent Constructions, Proceedings of the International Conference on Automation Innovation in Construction (CIAC-2019), Leiria, Portugal, 7–8 November 2019; Rodrigues, H., Gaspar, F., Fernandes, P., Mateus, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzeh, F.; Albanna, R. Developing a tool to assess workers’ understanding of lean concepts in construction. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC), Dublin, Ireland, 3–5 July 2019; pp. 179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Erazo-Rondinel, A.A.; Huaman-Orosco, C. Exploratory study of the leading lean tools in construction projects in Peru. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC29), Lima, Peru, 13 July 2021; pp. 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, S.; Ballard, G.; Naderpajouh, N.; Ruiz, S. Integrated Project Delivery for Infrastructure Projects in Perú. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference of the International 87 Group for Lean Construction, Chennai, India, 16–22 July 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, F.M. Influence of Integrated Teams and Co-Location to Achieve the Target Cost in Building Projects. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction, Berkeley, CA, USA, 6–12 July 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orihuela, P.; Noel, M.; Pacheco, S.; Orihuela, J.; Yaya, C.; Aguilar, R. Aguilar, Application of virtual and augmented reality techniques during the design and construction process of building projects. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction, Dublin, Ireland, 1–7 July 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erazo, A.; Guzman, G.; Espinoza, S. Applying BIM Tools in IPD Project in Perú. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction, Berkeley, CA, USA, 6–12 July 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, J.C.; Zapata, J.; Brioso, X. Using 5D Models and CBA for Planning the Foundations and Concrete Structure Stages of a Complex Office Building. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction, Berkeley, CA, USA, 6–12 July 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Sustainable Management of Construction and Demolition Materials; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://cfpub.epa.gov/si/si_public_file_download.cfm?p_download_id=537438&Lab=NRMRL (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Moyo, C.; Emuze, F. Building a lean house with the theory of constraints for construction operations in Zimbabwe: A conceptual framework. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC31), Lille, France, 26 June–2 July 2023; pp. 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiko, S.; Togarepi, S. A situational analysis of waste management in Harare, Zimbabwe. J. Am. Sci. 2012, 5, 692–706. [Google Scholar]

- Jerie, S. The role of informal sector solid waste management practices to climate change abatement: A focus on Harare and Mutate, Zimbabwe. J. Environ. Waste Manag. Recycl. 2018, 1, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 8th ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Madebwe, V.; Madebwe, C. Demolition waste management in the aftermath of Zimbabwe’s Operation Restore Order (Murambatsvina): The case of Gweru, Zimbabwe. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2006, 2, 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Mansour, M.S. Solid waste issue: Sources, composition, disposal, recycling, and valorization. Egypt. J. Petroleum. 2018, 27, 1275–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magadzire, F.R.; Maseva, C. Policy and legislative environment governing waste management in Zimbabwe. Am. J. Sci. 2006, 8, 692–706. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalp, G.G.; Anaç, M. A comprehensive analysis of the barriers to effective construction and demolition waste management: A bibliometric approach. Clean. Waste Syst. 2024, 8, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez-Martos, J.L.; Istrate, I.R. Construction and demolition waste management. In Advances in Construction and Demolition Waste Recycling; Pacheco-Torgal, F., Ding, Y., Colangelo, F., Tuladhar, R., Koutamanis, A., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, L.H.; Ahmed, S.M. Morden Construction: Lean Project Delivery and Integrated Practices, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Waheed, W.; Khodeir, L.; Fathy, F. Integrating lean and sustainability for waste reduction in construction from the early design phase. HBRC J. 2024, 20, 337–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, G.; Tommelein, I. Current Process Benchmark for the Last Planner System. 2016. Available online: https://p2sl.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Ballard_Tommelein-2016-Current-Process-Benchmark-for-the-Last-Planner-System.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Bajjou, M.S.; Chafi, A.; Ennadi, A. Development of a Conceptual Framework of Lean Construction Principles: An Input–Output Model. J. Adv. Manuf. Syst. 2019, 18, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedo, B.; Tezel, A.; Koskela, L.; Whitelock-Wainwright, A.; Lenagan, D.; Nguyen, Q.A. Lean Contributions to BIM Processes: The Case of Clash Management in Highways Design. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC29), Lima, Peru, 14–17 July 2021; pp. 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farell, P.; Sherratt, F.; Richardson, A. Writing Built Environment Dissertations and Projects: Practical Guidance and Examples, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: West Sussex, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, T.; Owens, L. Survey response rate reporting in the professional literature. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Conference of the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR), Nashville, TN, USA, 15–18 May 2003; pp. 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H. Designing a Questionnaire for a Research Paper: A Comprehensive Guide to Design and Develop an Effective Questionnaire. Asian J. Manag. Sci. 2022, 11, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanayake, U.H. Application of Lean Construction Principles and Practices to Enhance the Construction Performance and Flow. In Proceedings of the 4th World Construction Symposium 2015: Sustainable Development in the Built Environment: Green Growth and Innovative Directions, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 12–14 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bosnich, T. Applying Lean Construction Principles to Waste Management and Identifying Minimisation Opportunities to Inform the Industry. 2019. Available online: https://www.toiohomai.ac.nz/sites/default/files/inline-files/Applying%20lean%20construction%20principles%20to%20waste%20management%20and%20identifying%20minimisation%20opportunities%20to%20inform%20the%20industry_0.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Abo-Zaid, M.A.; Othman, A.A.E. Lean construction for reducing construction waste in the Egyptian construction industry. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Sustainable Construction and Project Management-Sustainable Infrastructure and Transport for Future Cities, Aswan, Egypt, 16–18 December 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Maponga, K.; Emuze, F. A Case for Lean-Based Guidelines for Construction and Demolition Waste Minimization in Zimbabwe. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC 32), Auckland, New Zealand, 1–7 July 2024; pp. 930–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, M.S. Assessment of different construction and demolition waste management approaches. HBRC J. 2014, 10, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmaraghy, A.; Voordijk, H.; Marzouk, M. An Exploration of BIM and Lean Interaction in Optimizing Demolition Projects. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC), Chennai, India, 16–22 July 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshara, I.A.R. Accreditation system for construction and demolition waste recycling facilities in Egypt. HBRC J. 2023, 19, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoyera, P.O.; Ndambuki, J.M.; Akinmusuru, J.O.; Omole, D.O. Characterization of ceramic waste aggregate concrete. HBRC J. 2018, 14, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzy, Y.A. Impact of recycled gravel obtained from low or medium concrete grade on concrete properties. HBRC J. 2018, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wagih, A.M.; El-Karmoty, H.Z.; Ebid, M.; Okba, S.H. Recycled construction and demolition concrete waste as aggregate for structural concrete. HBRC J. 2013, 9, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweis, G.; Hiyassat, A. Understanding the causes of material wastage in the construction industry. Jordan J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 15, 180–192. [Google Scholar]

- Aristizábal-Monsalve, P.; Vásquez-Hernández, A.; Botero, L.F.B. Perceptions on the processes of sustainable rating systems and their combined application with Lean construction. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 46, 103627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.S.; Huang, B.; Cui, L. Review of construction and demolition waste management in China and USA. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, J.; Drogemuller, R.; Toth, B. Model interoperability in building information modelling. Softw. Syst. Model. 2012, 11, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotayo, T.S.; Kulatunga, U.; Awuzie, B. Continuous Cost Improvement in Construction: Theory and Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Meshref, A.N.; Elkasaby, E.A.A.; Ibrahim, A. Selecting Key Drivers for a Successful Lean Construction Implementation Using Simos’ and WSM: The Case of Egypt. Buildings 2022, 12, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, M. Kaizen: The Key to Japan’s Competitive Success; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kapur, A.; Adair, N.; O’Brien, M.; Naparstek, N.; Cangelosi, T.; Jancasz, J.; Zuvic, P.; Joseph, S.; Meier, J.; Bloom, B.; et al. Improving efficiency and safety in external beam radiation therapy treatment delivery using a Kaizen approach. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2016, 96, S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashar, A. Process improvement in farm equipment sector (FES): A case on Six Sigma adoption. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2014, 5, 62–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Barraza, M.F.; Ramis-Pujol, J.; Llabrés, X.T. Continuous process improvement in Spanish local government: Conclusions and recommendations. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2009, 1, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shaboury, N.; Abdelhamid, M.; Marzouk, M. Framework for economic assessment of concrete waste management strategies. Waste Manag. Res. 2018, 37, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.W.; Doolen, T.L. A comparison of Korean and US continuous improvement projects. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2014, 63, 384–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Barraza, M.F.; Ramis-Pujol, J.; Kerbache, L. Thoughts on Kaizen and its evolution: Three different perspectives and guiding principles. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2011, 2, 288–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brajer-Marczak, R. Employee engagement in continuous improvement of processes. Management 2015, 18, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotayo, T.; Awuzie, B.; Egbelakin, T.; Obi, L.; Ogunnusi, M. AHP-systems thinking analyses for Kaizen costing implementation in the construction industry. Buildings 2020, 10, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotayo, T.; Kulatunga, U. A continuous improvement framework using IDEF0 for post-contract cost control. J. Constr. Proj. Manag. Innov. 2017, 7, 1807–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, G.; Pheng, L.S. Barriers to lean implementation in the construction industry in China. J. Technol. Manag. China 2014, 9, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.; Ruikar, K. Technology implementation strategies for construction organisations. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2010, 17, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.H. ICT implementation and evolution: Case studies of intranets and extranets in UK construction enterprises. Constr. Innov. 2007, 7, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yisa, S.B.; Ndekugri, I.; Ambrose, B. A review of changes in the UK construction industry: Their implications for the marketing of construction services. Eur. J. Mark. 1996, 30, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, A.; De Stefano, F.; Paolino, C. Safety Reloaded: Lean Operations and High Involvement Work Practices for Sustainable Workplaces. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 143, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. Does Formal Daily Huddle Meetings Improve Safety Awareness? Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res. 2014, 10, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bibany, H.; Abulhassan, H. Constraint-based collaborative knowledge integration systems for the AEC industry. In Proceedings of the Conference on Concurrent Engineering in Construction, Institute of Structural Engineers, London, UK, 3–4 July 1997; pp. 216–226. [Google Scholar]

- Simukonda, W.; Emuze, F. A Perception Survey of Lean Management Practices for Safer Off-Site Construction. Buildings 2024, 14, 2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zheng, A.; Hou, Y. Study on Impact Resistance of All-Lightweight Concrete Columns Based on Reinforcement Ratio and Stirrup Ratio. Buildings 2025, 15, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gaps | Effects | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| No management expertise | No expertise and technologies for recycling. | [16,20] |

| No financial resources | CDW continues to increase more than the available financial and technological resources. | [18] |

| Poor CDW policies | There are no laws and regulations to foster lean CDW minimisation. | [21] |

| No CDW tax reductions | No tax reductions on recycled construction materials. | [21] |

| Designers not involved in CDW minimisation. | Designers do not understand waste streams and are not involved in CDW management. | [22] |

| No waste management approvals. | Local authorities do not approve CDW management plans. | [21,22] |

| Production of CDW continues to increase. | CDW increases at a rate that is higher than available financial resources | [9,18] |

| Environmental problems. | Negative environmental effects. | [18] |

| Lean Tools | Application Techniques | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Uses flow charts to depict every work process. Identify and monitor CDW-generating work areas. Sorting and creating order on work sites. | [27,28,29] |

| Setting a standard working procedure. Using signs on site | [30,31] |

| Uses flow charts to depict every work process. Identify and monitor CDW-generating work areas. | [27,32] |

| Digital representation of the building. Models could be utilised. Supply of materials when they are needed. | [2,5] |

| Documenting and constantly checking back work for improvement. | [30] |

| Short everyday meetings focus on CDW-specific issues. | [2] |

| Attribute | Sub-Attribute | Responses | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional roles | Bricklayers, class one to class four | 20 | 7.7 |

| Semi-skilled bricklayers | 80 | 30.8 | |

| Carpenters, class one to class four | 20 | 7.7 | |

| Semi-skilled carpenters | 50 | 19.2 | |

| Painters | 20 | 7.7 | |

| Professionals | 43 | 16.5 | |

| Contractors | 27 | 10.4 | |

| General experience in construction | 1–5 years | 107 | 41.2 |

| 6–10 Years | 68 | 26.2 | |

| 11–15 Years | 41 | 15.8 | |

| More than 15 Years | 44 | 16.9 | |

| Experience of contractors | 1–5 Years | 5 | 18.5 |

| 6–10 Years | 4 | 14.8 | |

| 11–15 Years | 15 | 55.6 | |

| More than 15 Years | 3 | 11.1 | |

| Education levels of professionals | Ordinary level | 0 | 0 |

| National Certificate | 0 | 0 | |

| National Diploma | 13 | 30.2 | |

| Degree | 30 | 60.8 | |

| Education levels of Skilled workers | Ordinary level | 0 | 0 |

| National Certificate | 33 | 82.5 | |

| National Diploma | 7 | 17.5 | |

| Degree | 0 | 0 | |

| Education levels of Semi-Skilled workers | Ordinary level | 138 | 92 |

| National Certificate | 12 | 8 | |

| National Diploma | 0 | 0 | |

| Degree | 0 | 0 | |

| Education levels of contractors | Ordinary level | 5 | 18.5 |

| National Certificate | 10 | 37 | |

| National Diploma | 5 | 18.5 | |

| Degree | 7 | 26 |

| Code | Gaps in Practices | MS | STD DEV | Variance | RII | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAP1 | Production of CDW keeps on increasing | 4.54 | 0.64 | 0.404 | 0.91 | 1 |

| GAP2 | No expertise and technologies to recycle CDW | 4.23 | 0.93 | 0.873 | 0.85 | 2 |

| GAP3 | Dumping of CDW will cause environmental challenges | 3.92 | 1.47 | 2.156 | 0.78 | 3 |

| GAP4 | No CDW management plans | 3.77 | 1.43 | 2.031 | 0.75 | 4 |

| GAP5 | Designers do not understand waste streams | 3.62 | 1.33 | 1.782 | 0.72 | 5 |

| GAP6 | No laws and regulations to foster the embrace of lean | 2.96 | 1.46 | 2.122 | 0.59 | 6 |

| GAP7 | Tax reductions could be embraced to encourage | 2.77 | 1.34 | 1.800 | 0.55 | 7 |

| Code | Lean Techniques | MS | STD DEV | Variance | RII | Rank |

| LT1 | Recycling, recovering, and reuse | 4.62 | 0.63 | 0.39 | 0.92 | 1 |

| LT2 | Kaizen/continuous improvement | 4.52 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.90 | 2 |

| LT3 | Concurrent engineering | 4.27 | 1.06 | 1.12 | 0.85 | 3 |

| LT4 | Last Planner System | 4.15 | 1.29 | 1.68 | 0.83 | 4 |

| LT5 | Just-In-Time (JIT) | 4.08 | 1.30 | 1.69 | 0.82 | 5 |

| LT6 | Increased visualisation | 4.08 | 1.11 | 1.23 | 0.82 | 6 |

| LT7 | Standardisation | 3.92 | 1.41 | 2.00 | 0.78 | 7 |

| LT8 | Building Information Modelling (BIM) | 3.92 | 1.39 | 1.93 | 0.78 | 8 |

| LT9 | Daily huddle meetings | 3.79 | 1.37 | 1.87 | 0.76 | 9 |

| LT10 | Quality | 3.69 | 1.41 | 1.99 | 0.73 | 10 |

| LT11 | Waste (Muda) | 3.65 | 1.42 | 2.00 | 0.69 | 11 |

| LT12 | The five s’s (5S) | 3.46 | 1.31 | 1.72 | 0.69 | 12 |

| LT13 | Pull production | 3.46 | 1.63 | 2.64 | 0.63 | 13 |

| LT14 | Site organisation | 3.15 | 1.54 | 2.37 | 0.63 | 14 |

| LT15 | Value stream mapping (VSM) | 3.15 | 1.46 | 2.14 | 0.57 | 15 |

| LT16 | Kanban | 2.85 | 1.73 | 2.99 | 0.54 | 16 |

| LT17 | Six sigma | 1.92 | 1.36 | 1.85 | 0.38 | 17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Maponga, K.; Emuze, F.A.; Smallwood, J. Lean Framework for Minimizing Construction and Demolition Waste in Zimbabwe. Buildings 2026, 16, 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020337

Maponga K, Emuze FA, Smallwood J. Lean Framework for Minimizing Construction and Demolition Waste in Zimbabwe. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):337. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020337

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaponga, Kurauwone, Fidelis A. Emuze, and John Smallwood. 2026. "Lean Framework for Minimizing Construction and Demolition Waste in Zimbabwe" Buildings 16, no. 2: 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020337

APA StyleMaponga, K., Emuze, F. A., & Smallwood, J. (2026). Lean Framework for Minimizing Construction and Demolition Waste in Zimbabwe. Buildings, 16(2), 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020337