Abstract

Modern construction projects face persistent challenges with cost overruns and fragmented management across disconnected service phases. Whole-Process Engineering Consulting (WPEC) addresses these issues by integrating investment decision-making, design, supervision, and cost management into a unified delivery framework. Therefore, this study aims to develop a WPEC competitiveness influencing factor system to identify the key influencing factors and the impact pathways. Firstly, a WPEC competitiveness framework comprising five dimensions and 28 factors is developed. Secondly, the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is applied to calculate factor weights based on 225 questionnaires. Then, the multi-level structural model is constructed based on Interpretative Structural Modeling (ISM) to identify the critical impact pathways. Finally, BZ Consulting Enterprise was selected as a case study to verify the rationality and practical value. The results show that the Corporate Full-Service Consulting Capability and Corporate Foundational Resources are identified as the core pillars, in addition to highlighting three key pathways—resource-integration drive, legacy-capability transfer, and service-awareness transformation—all of which link foundational drivers to market performance. Theoretically, this study introduces a systematic analytical framework for WEPC by mapping its competitiveness factors into the multi-level structural model. Practically, it enables enterprises to assess their transition readiness and formulate targeted strategies to secure a sustainable competitive advantage in the integrated consulting market.

1. Introduction

Construction projects worldwide face escalating complexity driven by conflicting stakeholder interests, rapid technological advancements, and intensifying sustainability mandates [1,2]. These pressures generate systemic challenges, including resource inefficiencies, schedule slippage, and cost overruns, which threaten project viability [3,4]. The construction sector of China exemplifies these struggles acutely. Data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China indicate that in 2023, construction projects experienced average cost overruns of 15.6% and delay rates of 20.3% [5], which also reflect suboptimal capital allocation and a degradation of industry-wide productivity, necessitating structural reform. In response, the Chinese government formally promoted Whole-Process Engineering Consulting (WPEC) in 2017, initiating pilot programs in major hubs such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou [6]. By integrating investment decision-making, surveying, design, construction supervision, and cost management, WPEC provides a holistic framework to streamline workflows, enhance information transparency, and enable systematic risk mitigation across the project lifecycle [7,8].

Traditional phase-segregated models of engineering consulting operate through fragmented, single-service delivery, where design, supervision, and cost control function as segmented organizational silos with minimal cross-phase coordination [9,10]. This fragmentation generates information asymmetries and duplicative workflows that impede the interdisciplinary integration required for contemporary project delivery. The mechanisms through which firms achieve sustainable competitive transformation within the WPEC paradigm remain inadequately defined. Consulting enterprises frequently face challenges in reconfiguring internal resources or restructuring organizational processes to exploit the strategic opportunities presented by WPEC. Consequently, while the industry transitions toward integrated delivery, the influencing factors and impact pathways for establishing a firm-level competitive advantage remain undefined.

Despite the rapid adoption of WPEC across the Chinese construction sector, systematic research examining firm-level competitiveness remains scarce [6]. Extant literature predominantly addresses isolated service segments, such as independent design, standalone supervision, and analyzes industry trends without investigating the foundations of competitive advantage [11].The empirical drivers of WPEC competitiveness, including resource reconfiguration strategies and organizational transformation processes, remain underexplored. This theoretical gap leaves practitioners without reasonable guidance for navigating the transition to integrated project delivery [12].

Therefore, this study aims to develop an influencing factor system explaining WPEC competitiveness, to identify the influencing factors that during the transformation process, and to uncover the hierarchical interrelationships and impact pathways. This study addresses three research questions:

- RQ1: What are the factors influencing the WPEC competitiveness of Chinese engineering consulting enterprises?

- RQ2: Which factors are critical to achieving WPEC competitiveness for Chinese engineering consulting enterprises?

- RQ3: What are the critical impact pathways among influencing factors of WPEC competitiveness for Chinese engineering consulting enterprises?

This study constructs the WPEC competitiveness influencing factor system to identify the key influencing factors and the impact pathways for enterprises transitioning from traditional, fragmented services. It is conducted through four steps: factor identification through expert interviews, factor prioritization based on the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), hierarchical decomposition using Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM), and empirical validation through a case study of BZ Consulting Enterprise. Theoretically, this research provides a new perspective on WPEC by mapping the hierarchical transmission pathways between organizational resources and market performance. Practically, the WPEC competitiveness influencing factor system factors system enables enterprises to quantify the gap between technical reserves accumulated in traditional fragmented models and the integrated service capabilities required for WPEC. By analyzing the key factors and impact pathways, this study helps to guide the reallocation of corporate resources and ensure a sustainable competitive advantage in the emerging integrated consulting market.

2. Related Works

2.1. WPEC Development and Influencing Factors

The structural deficiencies of traditional segmented consulting models have been increasingly exposed by the escalating demands for efficiency, sustainability, and lifecycle management within the construction industry [13]. Early phase-segregated consulting delivered disciplinary depth but caused systemic incoherence and interface rework via isolated consortia, while segmented management introduced inter-phase delays and information distortions, undermining project efficiency [14,15,16,17,18]. The emergent Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) model integrated design and construction yet excluded front-end strategic briefing and back-end performance optimization, leading to misalignment between initial objectives and outcomes and a lifecycle value gap [19]. Collaborative design consulting synchronized multi-disciplinary efforts via Building Information Modeling but terminated coordination at handover, leaving design data disconnected from operational metrics and hindering long-term optimization [20]. However, extant studies has highlighted shortcomings in these models regarding resource integration, information flow, and collaborative efficiency, which collectively impede the capacity to address the interdisciplinary and cross-phase demands of modern projects [21,22]. Though sustainability-oriented consulting embedded lifecycle assessment in early design in some studies, it was constrained by partial scope and client-side technical deficits, with sustainability targets often altered during construction and carbon reduction goals unmet [23].

WPEC serves as a strategic response to these fragmented paradigms by integrating services across the entire project lifecycle, including investment decision-making, surveying, design, supervision, and operation and maintenance [24]. This integration facilitates a single consulting entity to maintain project objectives from inception to completion, addressing the functional gaps inherent in segmented models. Empirical evidence supports the efficacy of this approach in complex scenarios. For instance, the transformation of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention demonstrates how WPEC facilitates systematic project management under high spatial constraints and technical requirements in areas such as biosecurity and air purification [25]. Furthermore, research regarding refined management indicates that WPEC enhances project controllability by exercising precise oversight over project details [7]. Leveraging these strengths, identifying the influencing factors of WPEC competitiveness has become essential. Preliminary efforts to identify the drivers of WPEC competitiveness have been advanced by various scholars using diverse research methods. Huang et al. (2024) [6] qualitatively delineated the problems and shortcomings encountered in developing and promoting WPEC through policy analysis and multi-project statistics. Other researchers have adopted configuration analysis to explore how specific combinations of governance and cooperation benefits enhance project management performance [26,27]. To analyze adoption barriers to WPEC application and competitiveness, Ni (2022) [28] identified five critical dimensions of core competitiveness in WPEC firms: basic conditions, organizational management, teamwork, information technology application, and marketing, while emphasizing the decisive role of digital transformation in enhancing service capacity. Regarding the micro-level path of quality generation, Cui et al. (2025) [10] constructed the TEOK theoretical model, which categorizes technical, environmental, organizational, and knowledge management factors as the core determinants of service quality. Knowledge management capability is validated as the primary incentive for value creation. Furthermore, Huang et al. (2024) [6] employed complex network theory to identify 38 sub-indicators encompassing policy regulations, market recognition, and composite talent costs, thereby revealing the transmission mechanism between institutional environments and stakeholder behaviors. Wang (2020) [29] and Gao (2023) [30] further refined organizational forms centered on the chief consultant system and diversified implementation paths led by design or investment, providing theoretical support for management innovation. Research on the competitiveness of engineering consulting firms highlights that information technology levels and standardized organizational management are key factors in determining service capacity. And knowledge management capability and institutional environment optimization constitute essential drivers for successful implementation and sustained competitive advantage [10]. However, existing research lacks a systematic investigation into the quantitative weights of influencing factors of WPEC competitiveness and the identification of multi-layer impact pathways, which limits the formulation of targeted enhancement strategies.

2.2. Applications of AHP and ISM

The existing research employed a diverse array of decision-making and statistical methods such as AHP [31,32,33] ISM [34,35,36] the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) [37,38] Decision making trial and evaluation laboratory (DEMATEL) [39,40] Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) [41], to construct a hierarchical structure, revealing fundamental factors and their transmission levels within complex systems. Among these methods, the AHP-ISM framework elucidates the hierarchical structures and interdependencies essential for exploring the impact pathways of competitiveness influencing factors [42,43]. AHP offers capacity for multi-criteria evaluation by decomposing complex systems into target, criterion, and factor levels, thereby facilitating precise pairwise comparisons. Complementarily, ISM reconfigures qualitative correlations into explicit hierarchies to distinguish fundamental drivers from secondary effects. Regarding the integration of these methodologies for indicator analysis, Sharma et al. (2023) [44] identify and classify significant enablers within lean supply chains, utilizing AHP for enabler prioritization and ISM to define the structural logic of the system. Similarly, Cherkos and Kerenso (2025) [45] evaluate housing performance indicators, where Fuzzy-AHP established the relative importance of various criteria and ISM mapped the complex interrelationships to facilitate quadrant analysis.

The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) has proven effective for tackling complex decision problems. Jin (2015) [31], utilized AHP to prioritize tasks and optimize resource allocation, resulting in significantly enhanced decision-making efficiency. Further methodological refinements by Zhang et al. (2023) [32] integrated AHP with genetic algorithms to rectify judgment matrix inconsistencies, representing a critical advancement for WPEC projects that necessitate balanced multi-criteria evaluations. Complementarily, Lee et al. (2025) [33] demonstrated that AHP-based preference elicitation improves stakeholder coordination and user acceptance in multi-criteria decision support systems. Beyond these specific applications, AHP is extensively documented as a versatile tool for evaluating project alternatives and is frequently integrated with diverse decision techniques to bolster robustness in complex scenarios [46,47,48]. Consequently, the present study employs AHP to quantify the weights of influencing factors and identify key competitiveness influencing factor. However, AHP-focused investigations have concentrated on isolated factors, such as resource allocation or stakeholder weighting, without embedding multiple influences within a comprehensive system model of competitiveness.

As for ISM, Dang [34] employed ISM to explore the interrelationships among barriers impeding China’s shift to prefabricated construction, further utilizing the MIC-MAC model to classify these barriers and identify the key ones. This integrated framework offers insight into mutual barriers influence, with the potential for future research to quantify these interrelationships on a larger scale. Similarly, Li [35] employed ISM to dissect implementation barriers for Building Information Modeling (BIM) within the prefabricated construction sector in China, clarifying factor interdependencies. Maseko and Rotimi [36] likewise utilized ISM to map out risk-interdependencies in green-building projects, offering a structured approach to risk identification and management. These studies demonstrate that ISM is well-suited for dissecting complex interdependencies among project factors and delivering structured solutions for WPEC project. Consequently, the present study employs ISM to elucidate the hierarchical structure and impact pathways among the factors influencing WPEC competitiveness. However, ISM-based contributions have mapped hierarchical relationships among factors but remain incapable of quantifying the specific weights of critical influencing factors or their multi-layer impact intensities within a dynamic.

In summary, the convergence of these methods addresses the limitations associated with isolated applications because AHP establishes a robust weight distribution while ISM delineates the structural dependencies required to decipher WPEC competitiveness mechanisms. Consequently, the present study adopts this integrated AHP-ISM methodology to identify critical influencing factors and reveal the fundamental impact pathways within the WPEC competitive framework.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Approach and Strategy

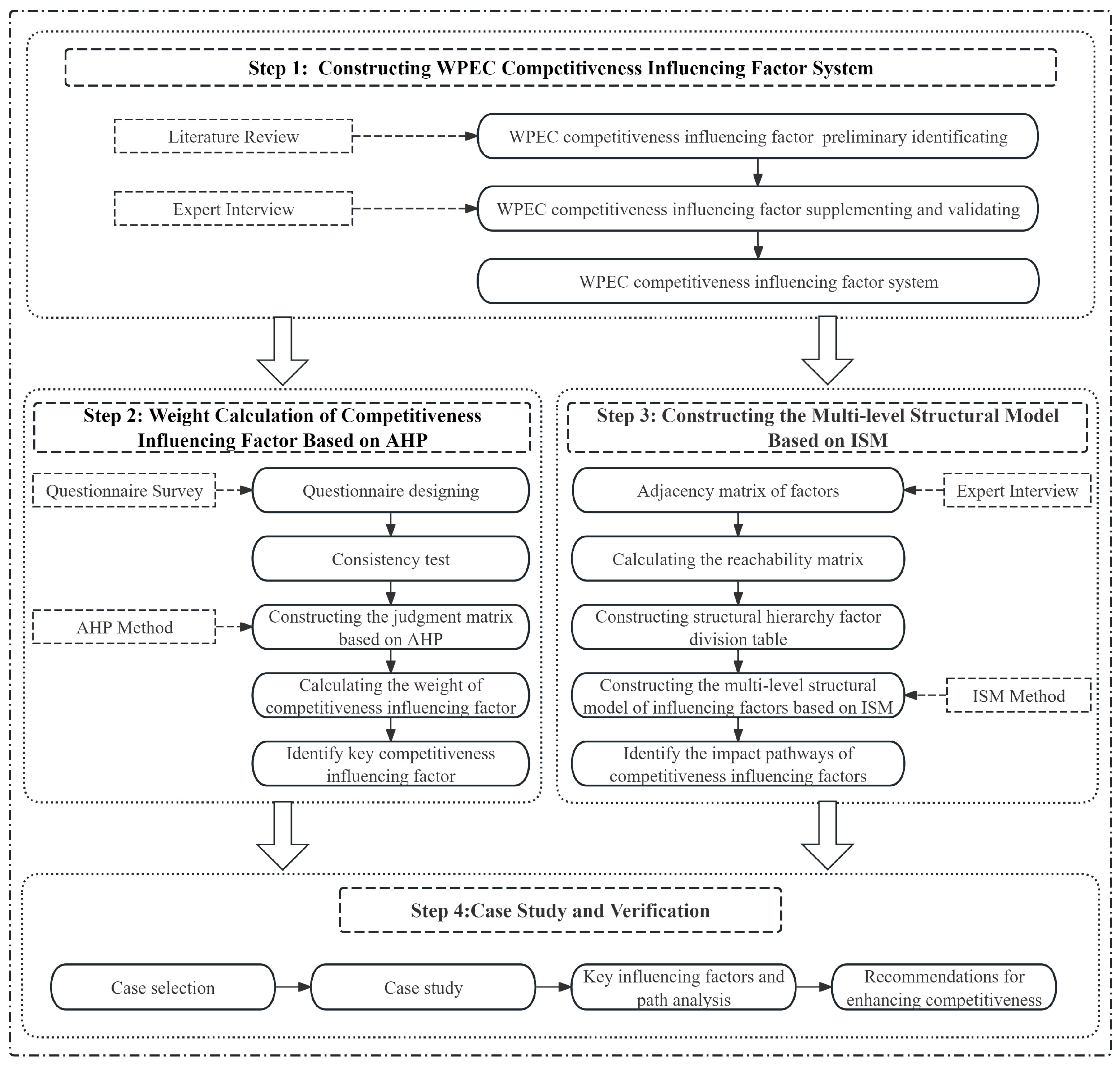

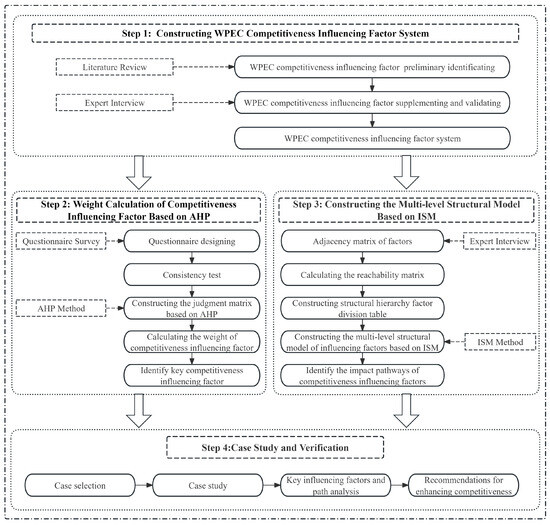

The research methodology consists of four steps, as illustrated in Figure 1. In step 1, a WPEC competitiveness influencing factor system is established through a literature review and expert interviews, resulting in a framework comprising five criterion layers and twenty-eight influencing factors. Step 2 involves applying the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to construct judgment matrices, which facilitates the calculation of relative weights and the execution of consistency tests to quantify the weight of each factor in competitiveness and identify key factors influencing competitiveness. Subsequently, step 3 utilizes Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) to analyze the logical relationships among factors by constructing adjacency and reachability matrices, which decompose complex interactions into a Multi-level Hierarchical Structural Model to reveal the impact pathways of competitiveness influencing factors. Finally, step 4 integrates the results from AHP and ISM through Influencing factor analysis and Impact Pathway Analysis, combined with case selection and a case study, to identify the core drivers of whole-process engineering consulting competitiveness and formulate targeted enhancement strategies.

Figure 1.

Research Framework. Notes: Abbreviations: WPEC refers to Whole-Process Engineering Consulting Competitiveness, AHP = Analytic Hierarchy Process; ISM = Interpretive Structural Modeling. Visual elements: Dashed boxes represent modular research step divisions; dashed arrows indicate information/method input relationships between links.

3.2. Research Design

3.2.1. Constructing WPEC Competitiveness Influencing Factor System

- (1)

- Factor preliminary identification based on literature review

This study conducts a literature review on Whole-Process Engineering Consulting (WPEC) and enterprise competitiveness, identifying relevant influencing factors. The search encompassed core databases including CNKI, Wanfang, Web of Science Core Collection, and Scopus to ensure comprehensive coverage of Chinese and international scholarly works. The temporal scope was designated as 2017–2025, marking the period from the official launch of WPEC policy initiatives in China.

- (2)

- Supplementation and validation based on expert interviews

Building upon the factors derived from the literature review, expert interviews were conducted to supplement and validate the influencing factors. To refine the influencing factors for determining the weight in the Analytic Hierarchy Process, the target population consisted of professionals with at least eight years of specialized experience in the management or research of Whole-Process Engineering Consulting projects.

A purposive, maximum variation sampling strategy was employed to recruit ten experts, including 7 managers from diverse consulting enterprises, 2 client-side project management specialists from the government and private sectors, and 1 academic researcher. This sample size was predicated on the principle of data saturation, as methodological standards in construction management research indicate that six to twelve interviews are sufficient for focused factor identification [49]. These expert interviews facilitated the refinement of the initial factor system, leading to the critical inclusion of variables such as External Resource Integration, Corporate Nature and Scale and client preference for Whole-Process Engineering Consulting.

3.2.2. Calculating the Weight of Competitiveness Influencing Factor

- (1)

- Questionnaire designing and consistency test

Based on WPEC Competitiveness Influencing Factor system, a questionnaire was distributed to practitioners from construction units, consulting institutes, and contracting firms to collect importance ratings for quantitative analysis. For the subsequent questionnaire survey, the target population encompassed practitioners from construction units, consulting institutes, and contracting firms. The geographical focus was restricted to Beijing and its contiguous regions, which serve as the strategic core for WPEC pilot initiatives in China. From 500 administered questionnaires, 357 surveys were returned, representing a response rate of 71.4%. After excluding 132 invalid responses due to incomplete data or failed attention-check items, 225 valid questionnaires remained for final analysis, resulting in an effective response rate of 63.03%. To uphold research integrity, strict ethical standards were maintained throughout all data collection procedures. Because this study employed anonymized survey methodologies and did not involve personally identifiable data or sensitive medical information, it did not require formal institutional review. Nevertheless, this research obtained formal informed consent from all participants and enforced anonymity during the data processing phase to ensure that findings remain aggregated and non-attributable. Figure 1 illustrates the complete research framework.

The sample size was validated using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 SPSS. For an AHP framework involving a pairwise comparison matrix of 28 factors, a post hoc power analysis indicated that 225 participants exceed the minimum requirement of 200 necessary to achieve a statistical power of 0.95 at an alpha level of 0.05. This confirms the statistical sufficiency of the data for weight calculation and structural modeling. The questionnaire instrument comprised four modules, including an introductory statement on research objectives and confidentiality, a respondent demographic profile, a factor evaluation section utilizing a 100-point scale, and a formal acknowledgment.

- (2)

- Constructing the judgment matrix based on AHP

The Analytic Hierarchy Process facilitates the decomposition of complex systems into a hierarchical structure consisting of a target layer, criterion layers, and influencing factors. To quantify the relative importance of the 28 factors, pairwise comparison matrices A = are constructed. In these matrices, the element represents the relative importance of factor i compared to factor j through the application of the Saaty nine-point scale, where 1 signifies equal importance, and 9 signifies extreme importance.

Consistency tests are required to ensure the logical rigor of the subjective evaluations. The Consistency Ratio CR is calculated using the following formula:

In this equation, CI = represents the Consistency Index, is the maximum eigenvalue, and RI is the average Random Consistency Index derived from standard tables based on the matrix order n. A matrix is considered logically consistent if the CR value remains below the threshold of 0.1 [50].

- (3)

- Calculating the weight of competitiveness influencing factor

The sum-product method is applied to the pairwise comparison matrices to derive eigenvectors and weight vectors. The specific weight for each indicator is calculated as follows.

Key competitiveness influencing factors are identified based on the magnitude of their global weights, which are the product of the influencing factors weight and the corresponding criterion layer weight.

3.2.3. Constructing the Multi-Level Structural Model Based on ISM

- (1)

- Adjacency matrix

The Interpretive Structural Modeling phase begins with the construction of an adjacency matrix F to represent direct relationships between the 28 factors. 11 experts evaluated the interrelationships using symbols A, V, and O to denote the direction of influence. These qualitative assessments are converted into a binary adjacency matrix based on the following logic:

- (2)

- Reachability matrix

The reachability matrix M is computed to illustrate both direct and indirect relationships through transitive logic. This matrix is derived using Boolean algebraic operations based on the power-set convergence formula:

In this formula, represents the identity matrix and is the smallest integer satisfying the condition = . The resulting matrix provides a map of the reachability set , antecedent set , and intersection set for each factor.

- (3)

- Constructing the multi-level structural model

The multi-level structure is established through iterative partitioning of the reachability matrix. Factors satisfying the condition = are extracted layer by layer, starting from top-level outcomes down to fundamental drivers. This process results in a Multi-level Hierarchical Structural Model. This model reveals the impact pathways of competitiveness influencing factors.

3.2.4. Case Study and Verification

To verify the practical applicability and empirical validity of the established factors system and the AHP-ISM model, a representative case study was conducted on BZ Consulting Enterprise. This enterprise was selected as the research object due to its status as a large-scale comprehensive engineering consulting firm in China that is currently undergoing a strategic transition from traditional fragmented services to the whole-process engineering consulting (WPEC) model. The case study analysis was executed through three systematic steps. First, an internal diagnostic evaluation was performed by collecting longitudinal data regarding the performance of BZ Consulting Enterprise in WPEC project delivery and its resource allocation strategies. Second, the performance metrics of the enterprise were mapped against influencing factors identified in this study to determine the specific capability gaps. Third, the results derived from the AHP-ISM model, including the high-weight dimensions and the hierarchical transmission pathways, were utilized to analyze the operational practices and transformation bottlenecks of the enterprise.

4. Results

4.1. WPEC Competitiveness Influencing Factor System

This section identifies the multi-dimensional factor system influencing the competitiveness of Chinese engineering consulting enterprises during WPEC transformation. The final framework comprises 5 key dimensions and 28 specific indicators, comprehensively capturing internal resources, service capabilities, and external adaptation requirements. Synthesized through a literature review and subsequent expert consultations, the system is organized into a hierarchical structure consisting of one target layer, five criterion layers, and 28 influencing factors. The identified dimensions include the Legacy Industry Transition Foundation (B1), Corporate Foundational Resources (B2), Whole-Process Consulting Business Cultivation (B3), Marketing Capability (B4), and Corporate Full-Service Consulting Capability (B5).

Expert interviews facilitated the optimization of this system by refining criterion terminology and incorporating critical variables such as ethical risk mitigation management and client preference for full-service consulting. These adjustments ensured that the framework reflects the current business environment and practical transformation requirements. Consequently, this multi-dimensional structure provides the theoretical breadth necessary to capture the complex nature of enterprise competitiveness during the transition to the WPEC model.

Expert interviews subsequently optimized the system for validity and applicability as presented in Table 1. Criterion layer wording was adjusted per expert recommendations. “Enterprise soft power” was relabeled “Whole-Process Consulting Business Cultivation” to reflect WPEC practice. Three factors, namely C5 Corporate Nature and Scale, C16 Ethical Risk Mitigation Management, and C20 Client Preference for Full-Service Consulting, were added. Analogous indicators were merged. C24 Investment Evaluation and Control and C25 Planning and Technical Solution Optimization were classified under the B5 Corporate Full-Service Consulting Capability dimension. The final system comprises one target layer, five criterion layers, and twenty-eight influencing factors.

Table 1.

Factors and Indicators of Consulting Firm’s Comprehensive Engineering Consulting Competitiveness After Expert.

B1 Legacy Industry Transition Foundation stresses the accumulation of traditional business as the springboard for WPEC transformation. B2 Corporate Foundational Resources covers the core assets required for integrated service delivery. B3 Whole-Process Consulting Business Cultivation captures the capability to build new service lines. B4 Marketing Capability reflects market acceptance and expansion potential. B5 Corporate Full-Service Consulting Capability targets the core performance of WPEC. The inclusion of C16 Ethical Risk Mitigation Management and C20 Client Preference for Full-Service Consulting responds to practical pain points ethical risk in integrated projects and client demand orientation that are often neglected in traditional consulting research yet critical for long term WPEC development. This system closes the gap between theory and industrial practice and provides a comprehensive basis for evaluating enterprise competitiveness.

4.2. Weight Analysis of Influencing Factors

As shown in Table 2, AHP was applied to 225 valid questionnaires to compute factor weights. To verify the scientific validity of the model, this research performed consistency tests on all judgment matrices. As detailed in Table 3, all consistency ratios (CR) for the pairwise comparison matrices remained strictly below the 0.1 threshold. This includes the matrices constructed for the target layer relative to the criterion layers as well as those for each criterion layer relative to its respective influencing factors. This statistical outcome confirms that the expert judgments utilized for weight calculation across all hierarchical levels are reliable and logically consistent.

Table 2.

AHP Hierarchy Analysis Factors Influencing the Enhancement of Consulting Firm’s Comprehensive Consulting Competitiveness Weight Table.

Table 3.

AHP Consistency Test Results.

The weight distribution provides three primary insights regarding enterprise competitiveness. First, the combined weight of Corporate Full-Service Consulting Capability (B5) and Corporate Foundational Resources (B2) totals 80.96%, indicating that competitiveness depends primarily on core service offerings and the underlying resource base. This pattern aligns with Competitive Strategy Theory by emphasizing the synchronization of internal capabilities with external market demand. Second, On-site Quality and Safety Supervision (C27) carries the highest individual weight at 12.86%, suggesting that direct operational control remains the foremost client concern and a fundamental weakness in traditional fragmented consulting models. Strengthening this specific capability is therefore essential for establishing a competitive advantage. Third, Information Technology Level (C10) represents the dominant factor within the foundational resource block at 10.08%, underscoring digital infrastructure as a critical enabler for integrated management. Enterprises lacking advanced information systems cannot execute efficient data sharing or lifecycle control, which adversely affects their competitive standing. Indicators within Whole-Process Consulting Business Cultivation (B3) and Marketing Capability (B4) receive lower weights, implying that business cultivation and marketing are secondary to core capacity and resource endowment during the current transition phase in China. Consequently, firms should prioritize the development of internal capabilities over external market expansion.

4.3. Impact Pathway Analysis of Competitiveness Influencing Factor

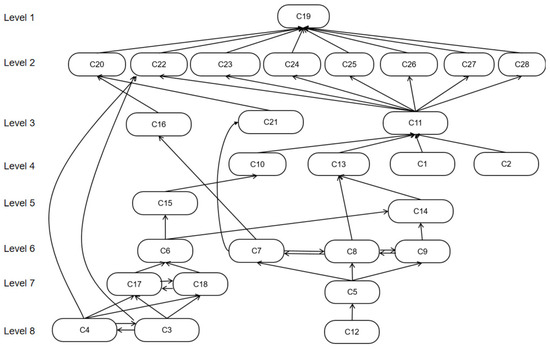

To investigate the internal interrelationships among these influencing factors and reveal the core pathways for improving WPEC competitiveness through a multi-level structural model, the Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) method was employed to construct hierarchical interrelationships among the 28 factors. The resulting model organizes these factors into an eight-level structure ranging from fundamental drivers to surface outcomes. Through the application of Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM), the hierarchical influence pathways affecting competitiveness were effectively delineated.

4.3.1. Structural Hierarchy Factor Division

Reachability Set, Antecedent Set and Intersection Sets

The reachability matrix was calculated based on the adjacency matrix derived from expert interviews, from which the reachability set, antecedent set, and intersection set were obtained, as presented in Table 4. A structure-priority extraction method was employed to perform hierarchical iteration calculations. Following seven rounds of extraction, the 28 factors were classified into eight levels, the final results were determined as shown in Table 5.

Table 4.

Reachability, Antecedent, and Intersection Sets.

Table 5.

Structural Hierarchy Factor Division Table.

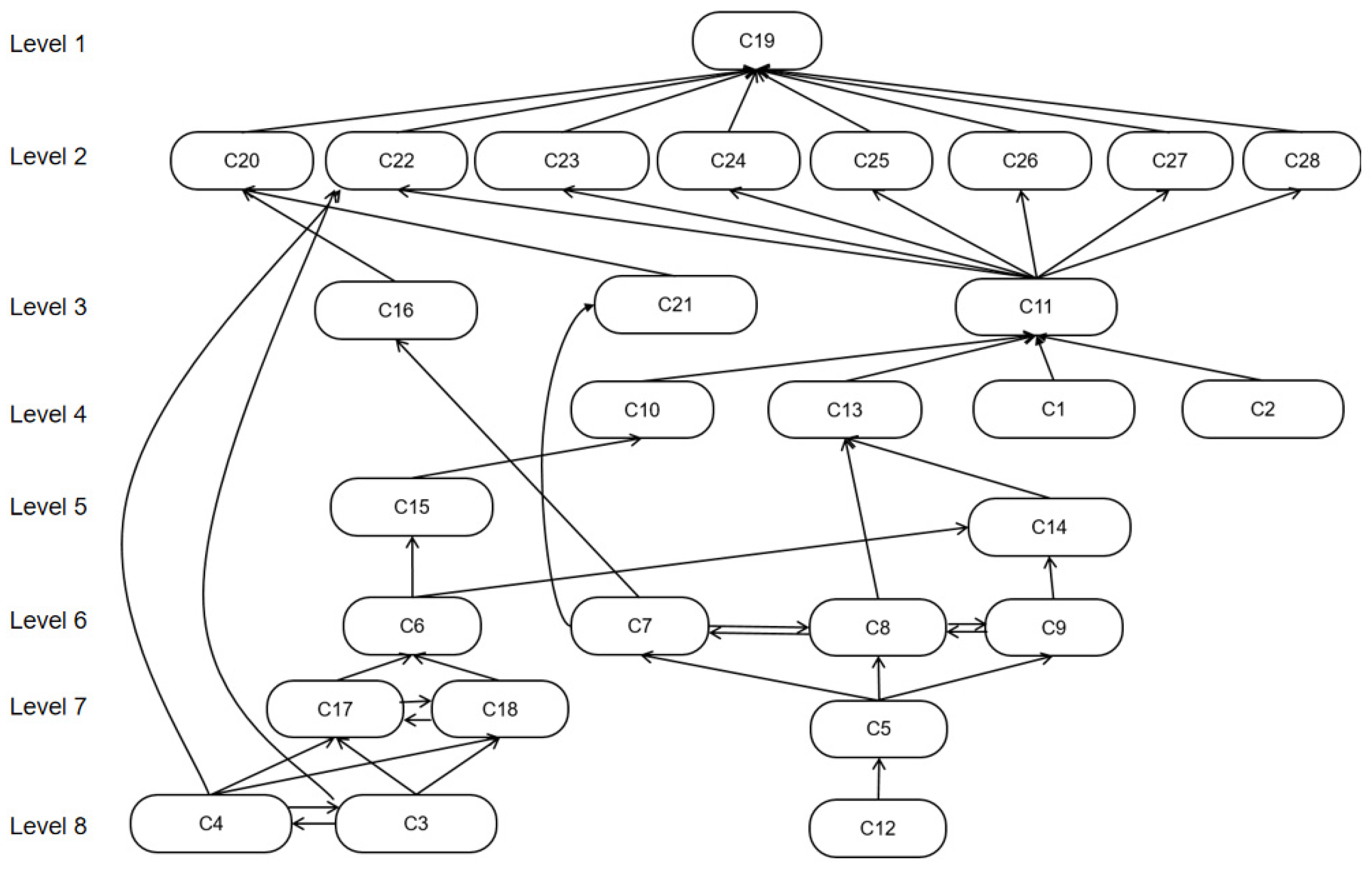

4.3.2. Analysis of Multi-Level Structural Model and Impact Pathways

Level 8 drivers, namely C3 Level of Participation in Original Business Processes, C4 Degree of Communication and Coordination with Upstream/Downstream in Original Business, C12 External Resource Integration, reside at the base. As the base-level factors, they fundamentally drive all upper-level elements.

The intermediate levels from Level 2 to Level 7 transmit effects through mediating factors like C8 Organizational Management Status, C11 Industry Knowledge System Reserve, and C13 Full-Service Consulting Team Development. They served as a bridge between deep-seated driving factors and surface result factors and were key intermediate links in the influence path.

Surface outcome Level 1 is C19 Full-Service Consulting Implementation Status. It encapsulates the combined influence of all underlying factors and mirrors enterprise competitiveness.

An explanatory structural model, based on the seven-level hierarchy, is thereby constructed to illustrate the interrelationships among these factors. The model yields the hierarchical topology shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Hierarchical Topology Diagram. Note: Arrows represent directional influence relationships between factors (C1–C28) across levels: the starting end of an arrow corresponds to the influencing factor, while the terminal end refers to the factor being affected.

Figure 2 identifies L8 drivers: C3, C4, and C12. They drive C16, C21, and C11 via C6–C9. Ultimately, they elevate C20 and C22–C28 capabilities. Three core influence paths are distilled from the topology.

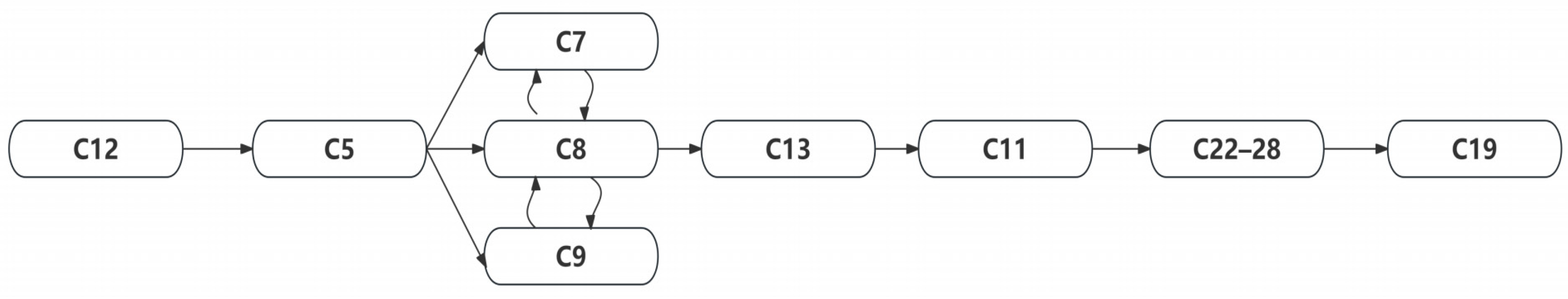

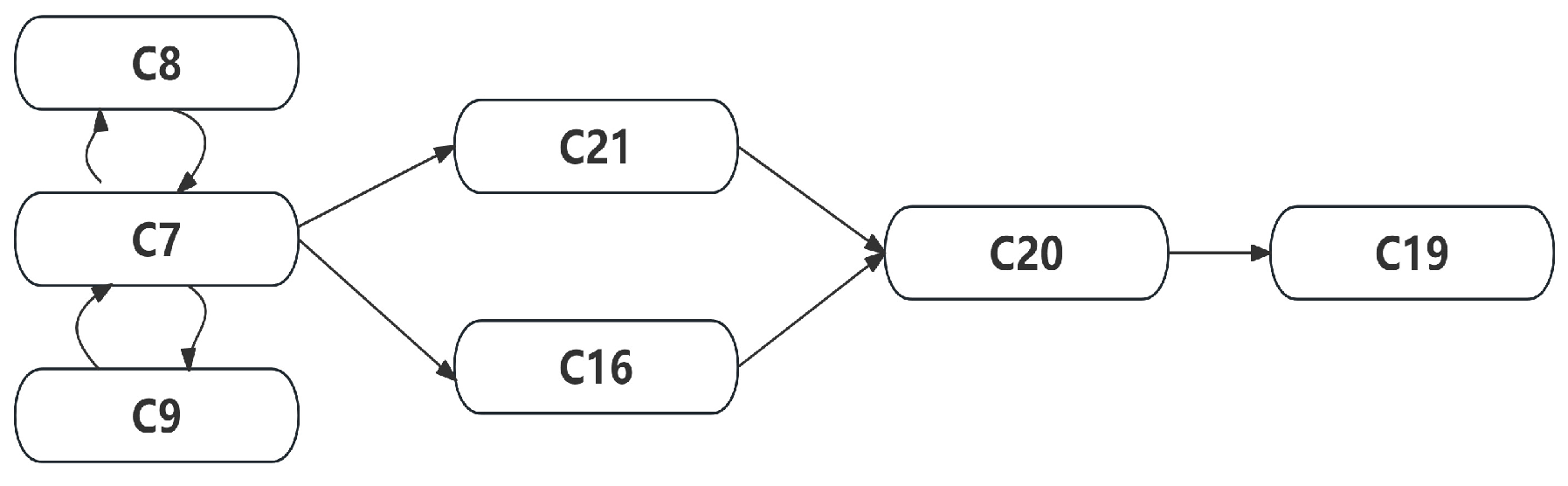

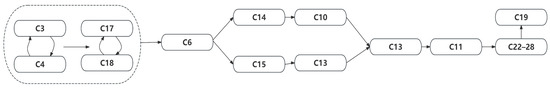

Pathway 1 initiates with resource integration, where scaled enterprise initiatives allocate operational, organizational, and human resources. This integration has been shown to enhance the capabilities of the full-service consulting team, thereby augmenting the depth and breadth of their professional service knowledge. Consequently, this integration comprehensively strengthens full-service consulting capabilities and advances the market. The corresponding key path appears in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Impact Pathway 1.

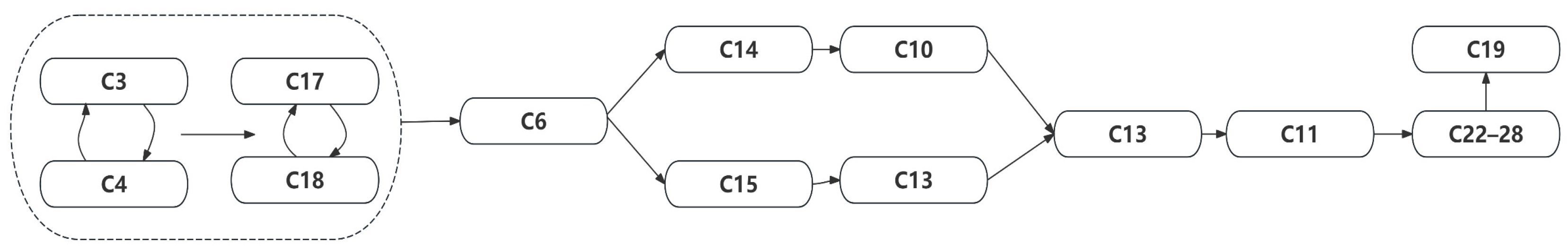

Pathway 2 is driven by legacy-business foundations that expand corporate capital strength to remedy personnel and knowledge shortfalls. Meanwhile, it takes information/details and digitalization as a corner to comprehensively strengthen various full-service consulting capabilities, and finally realizes the improvement of the full-service consulting market. The corresponding key path is given in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Impact Pathway 2.

Expanding business formats requires enterprises to maintain legacy capabilities and a robust market. Consulting enterprises rely on legacy market capital, experience, and technology. Full-service consulting capabilities are achieved by allocating capital, human resources, and teams to legacy operations. Externally, former clients and collaborators from legacy markets are leveraged to enter new segments. This approach builds on legacy market resources and business foundations. It provides financial and technical support for gradual transformation into full-service consulting.

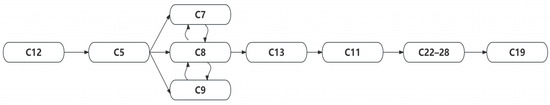

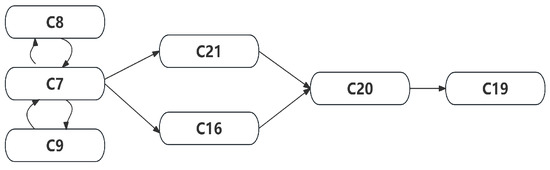

Pathway 3 is driven by service concept transformation. Service awareness transformation initiates the path, followed by ethical risk mitigation. Deep pain-point resolution then creates unique competitive edges. The corresponding key path is illustrated in Figure 5. Unlike prior paths, this methodology emphasizes service awareness transformation and ethical risk mitigation, factors that are topologically peripheral yet often overlooked in practice.

Figure 5.

Critical Path 3.

This path centers on enterprise service paradigm shifts and risk governance construction. By optimizing the service supply system and improving the risk prevention and control mechanism, it enhances the service satisfaction and trust of clients, thereby promoting the market penetration of whole-process engineering consulting services. In a market environment characterized by rapid industry growth and intensified homogeneous competition among enterprises, those that can establish a systematic service framework and implement full-cycle ethical risk management are more likely to form a differential competitive advantage, obtaining priority in cooperation with construction units, and achieve effective expansion of market shares.

The eight-level hierarchy uncovers a bottom-up genesis of WPEC competitiveness. L8 contains the prime movers, namely enterprise involvement in original business flows, upstream downstream coordination, and external resource integration. These elements underpin every subsequent capability advance. Lacking deep participation in original processes, a firm cannot amass the experiential knowledge demanded by a full cycle WPEC delivery. Layers L3 through L7 act as conduits that relay the impetus of the drivers to the outcome tier. L6 embodies organizational and talent competences forged from foundational resources, thereby enabling L4 to cultivate digital infrastructure and high-performance teams. The uppermost L1 L2 cluster constitutes the outcome stratum, where the realized state of full-service consulting signals overall competitiveness, and the indicators grouped in L2 denote the specific service capabilities that shape that final state.

5. Discussion

5.1. Case Study

To verify the rationality and practical value of the results, BZ Consulting Enterprise was selected as a case study. In this section, the theoretical framework is integrated with the enterprise’s development background, business status, transformation practice, and existing pain-points. This corroborates the practical adaptability of the conclusions to provide targeted directions for BZ Enterprise to optimize its WPEC business, and offers empirical references for the transformation of similar traditional engineering consulting firms.

5.1.1. Introduction of BZ Enterprise

BZ Enterprise was founded in 1986 as a municipal first-grade engineering consulting institution and was transformed into a state-owned enterprise under municipal state-owned management in 2020. Over 40 years, a traditional consulting service system covering the whole project cycle was established, and more than 20,000 projects with a total investment of CNY 1 trillion. In 2023, the enterprise employed 1532 staff, among whom 397 held master’s degrees and 301 held senior titles; annual revenue reached CNY 682 million. In response to policy requirements, a WPEC business division was established in 2017; the division currently employs approximately 300 staff and operates under a model that integrates the PMO and the project manager responsibility system. Although the business covers the whole process, the division remains in a critical transformation stage, thereby supplying a practical basis for system verification.

5.1.2. Adaptability and Discussion on BZ Enterprise

From the perspective of the criterion layer “Legacy-Industry Transition Foundation”, the traditional business of BZ Enterprise is primarily concentrated in pre-project consulting, whereas involvement in mid- and late-stage engineering supervision and on-site management remains limited. Consequently, experience in communication and coordination with upstream and downstream construction units is insufficient. These conditions align with the study of Shen [14], who report synergy barriers for firms transitioning to whole-process consulting because of fragmented service coverage. AHP analysis indicates that both factors are weighted at 22.22%, confirming that insufficient whole-process coverage of the legacy industry and weak coordination ability constitute bottlenecks that restrict WPEC competitiveness [51]. This finding aligns with Mazzetto (2024) [12], who identified fragmented service coverage as a key barrier to WPEC promotion using complex network analysis, and Hu et al. (2024) [52], who emphasized that upstream-downstream coordination deficiencies hinder integrated service delivery in WPEC transformation. Our results further quantify the importance of these barriers accounting for 44.44% of B1’s weight, providing empirical support for prior qualitative observations with AHP-derived data.” Moreover, internal review findings by BZ regarding information gaps and reduced delivery efficiency are consistent with the results of Fang [7] on information flow in project collaboration, which demonstrate that limited stakeholder participation during execution creates information-asymmetry nodes and reduces efficiency. The service framework further validates that non-participation in the construction stage breaks the data closed-loop and leads to disjointed decision-making and efficiency losses.

In the criterion layer “Corporate Foundational Resources”, BZ Enterprise has scale and capital advantages, with 12 wholly owned subsidiaries and 14 branches. Revenue increased from CNY 488 million to CNY 682 million between 2018 and 2023, thereby supplying financial support for the WPEC business; this trend is consistent with the capital-strength factor, which is weighted at 8.96%. This aligns with studies showing that financial resources are a key determinant of competitiveness in complex project [53,54]. Shortcomings remain, however, in information-system construction and talent reserves. The independently developed project-management information system merely enables online management of core business, whereas application depth remains insufficient in on-site quality-and-safety early warning and in dynamic risk management and control; thus, improvement of the informatization level, weighted at 10.08%, is urgently required. Within the WPEC team of 281 employees, 56 are Hu et al. (2024) [52] emphasized that deficiencies in upstream-downstream coordination significantly hinder integrated service delivery during the transformation of cost consulting enterprises. The results of this study further quantify the significance of these barriers, which account for 44.44% of the weight within the Legacy Industry Transition Foundation (B1). This finding provides robust empirical support for prior qualitative observations by incorporating objective data derived from the Analytic Hierarchy Process. First-class registered constructors and 28 are first-class cost engineers, yet interdisciplinary talents combining technical management and economic capabilities remain scarce; only 26 employees hold IPMP or PMP certificates. This scarcity aligns with the talent-reserve factor, weighted at 8.96%, as a key restrictive element. Li [55] similarly stress the importance of comprehensive information-system integration for effective management and quality control in construction projects.

The criterion layer “Corporate Full-Service Consulting Capability” holds the highest weight in the system at 42.86%. Conventional business activities of BZ Enterprise have been concentrated in pre-project consultancy, resulting in deficiencies in key WPEC domains such as on-site quality and safety management and construction process control. AHP analysis indicates that on-site quality-and-safety supervision is weighted at 12.86%, the highest value among all influencing factors. In practice, on-site management of WPEC projects is delegated to external supervision teams, leading to increased project costs and delayed problem response because of poor internal–external collaboration. Similarly, research on construction-process improvement emphasizes the necessity of an integrated regulatory system to ensure safety and efficiency [56]. This finding reinforces the pivotal role of on-site quality-and-safety supervision and underscores the precision with which the core service-capability bottlenecks of transforming enterprises are identified.

5.2. Influencing Factors on WPEC Competitive Advantage

A system consisting of one target layer, five criterion layers, and twenty-eight influencing factors that influence WPEC competitiveness was established. Compared with the previous research, Cui et al. (2025) [10] employed the TEOK model to categorize consulting quality into four dimensions: technical, environmental, organizational, and knowledge factors, emphasizing that technical and organizational elements constitute the core determinants of service quality. Similarly, Ni (2022) [28] identified five critical dimensions influencing corporate competitiveness, including foundational conditions, organizational management, teamwork, information technology application, and marketing. Within these dimensions, foundational conditions and teamwork are regarded as the structural cornerstones of firm capacity. Therefore, the indicators identified in this study align precisely with the technical and organizational dimensions as well as the foundational conditions reported in the aforementioned literature, validating the universal role of these elements in evaluating the competitiveness of engineering consulting.

The prioritization of key factors identified to achieving WPEC competitiveness for Chinese consulting enterprises offers significant implications for resource management. The results indicate that the aggregate weight of the two criterion layers: Corporate Full-Service Consulting Capability and Corporate Foundational Resources, reaches 80.96%. This strategic approach is consistent with several published findings. For instance, a study on the sustainability evaluation of renewable energy incubators using AHP identified that service capability, including on-site management and supervision, as a critical success factor [57]. Similarly, research on the improvement of the construction process emphasizes the necessity of an integrated system for regulatory standards to ensure safety and efficiency. These findings underscore the precision with which the core service capability bottlenecks of transforming enterprises have been identified [45]. This has necessitated a reallocation of resources away from areas such as the enterprise marketing level criterion layer, which has been assigned a weight of only 4.76%. Meanwhile, Technical Resource Integration and Cross-phase Collaborative Management emerge as the most vital drivers. Compared to the policy and market dimensions proposed by Huang et al. (2024) [6], the Technical Resource Integration factor in the present study describes competitiveness from the perspective of lifecycle data continuity and multi-disciplinary synergistic effects. In practical engineering contexts, this factor is fundamental for eliminating information silos inherent in traditional fragmented models, as WPEC requires objective consistency from the decision-making stage through to operation and maintenance. This indicator aligns with the diversified implementation paths led by design or investment discussed by Wang (2020) [29], which highlights the supportive role of technical depth in management innovation.

Furthermore, the Standardized Organizational Management factor identified in this study reinforces the stability of competitiveness from the perspective of system structural logic and procedural compliance. This finding is highly consistent with the research of Sharma et al. (2023) [44] regarding the definition of system efficiency through structural logic in lean supply chains. Sharma argue that resource allocation should focus on the structural enablers of the system rather than isolated functional strengths, providing theoretical support for the negligible weight assigned to the marketing level in this study. During the nascent transformation stage, BZ Enterprise sought to expand WPEC operations by leveraging established market share in engineering consulting. However, capability mismatches between traditional consulting and WPEC led to an insufficient conversion of new projects and a failure to meet expected targets. This practical outcome corroborates the conclusion that internal service integration exerts a more decisive impact on overall performance than external marketing efforts. During the nascent transformation stage, BZ Enterprise sought to expand WPEC operations by leveraging established market share in engineering consulting. However, capability mismatches between traditional consulting and WPEC resulted in insufficient conversion of new projects and failure to meet expected targets. This practical outcome corroborates the conclusion that the marketing level exerts negligible impact on the o performance [57].

5.3. Interrelationships Among Factors in Impact Pathways

The multi-level structural model of WPEC Competitiveness facilitates the decomposition of the hierarchical transmission pathways among influencing factors, enabling the identification of the structural logic between fundamental drivers and target outcomes. The resource integration and organizational management links in the model are verified by the measures implement of BZ Enterprise. Following the interviews, BZ Enterprise underwent a corporate restructuring that amalgamated the original project-management department with its supervision-specialized subsidiary in 2020. This strategic decision aimed to integrate internal technical and managerial resources. A model integrating the PMO and project-manager responsibility system was established, resulting in optimized organizational management. Concurrently, collaborative agreements with external legal institutions were established, augmenting the scope of project legal services. However, limited progress was demonstrated in constructing the WPEC service team. Professional coverage across investment, construction, and law is deemed inadequate within the team. Moreover, interdepartmental collaboration is suboptimal. This deficiency directly restricts improvements in WPEC capabilities such as schedule control and investment management. The WPEC service-team construction link is located at the fourth layer of the eight-layer ISM hierarchy, constituting a pivotal intermediate node.

The case study of BZ Consulting Enterprise illustrates how the resource-integration path functions through corporate restructuring and the establishment of a PMO-based management model. However, the analysis also reveals potential obstacles, such as the inadequacy of the WPEC service team that acts as a pivotal intermediate node in the ISM hierarchy. This result is consistent with the research conducted by Dang et al. (2024) [34] and Li et al. (2021) [35], who demonstrated the effectiveness of the ISM approach in dissecting complex factor interdependencies within the domain of construction management. By mapping these interdependencies, the study demonstrates that improvements in schedule control and investment management are contingent upon the successful development of multi-skilled talent pools and interdepartmental collaboration. These insights allow firms to move beyond isolated factor improvement toward systemic transformation.

5.4. Research Limitations and Future Works

This study contributes to the theoretical framework and empirical analysis of WPEC competitiveness, but several limitations should be acknowledged, which also point to avenues for further refinement. First, sample representativeness and data limitations constrain the generalizability of the findings. The factor identification and AHP weight determination relied on expert interviews, predominantly from large-scale engineering consulting firms in eastern China. This sample bias may overlook the distinctive challenges faced by small and medium-sized enterprises or firms in underdeveloped regions, where resource constraints and policy adaptation barriers differ significantly. Second, the integrated AHP-ISM framework effectively quantifies factor importance and hierarchical relationships but fails to capture dynamic interactions over time. Third, the study centered on internal organizational factors while neglecting the moderating role of external contextual variables, such as regional policy incentives, industry competition intensity, and technological disruption.

To further enhance generalizability, future studies should broaden the expert sample to include small and medium-sized enterprises, firms from midwestern regions, and international practitioners to capture cross-contextual variations in WPEC competitiveness drivers, integrate mixed data sources by combining qualitative expert insights with quantitative data such as financial reports, project completion records, and client feedback to reduce subjective bias in factor weighting, and conduct comparative analyses between different project types to identify scenario-specific critical factors. Regarding methodological advancements, future research should focus on enhancing the AHP-ISM framework with fuzzy logic to better handle the ambiguity of expert judgments and coupling it with the MIC-MAC model to classify factors by driving power and dependence, thereby refining path identification; it should also integrate system dynamics (SD) or dynamic factor models to simulate how factor interactions evolve over the project lifecycle, enabling prediction of long-term competitiveness trends under different policy or market scenarios.

6. Conclusions

As engineering consulting enterprises undergo a strategic transition from traditional, fragmented services to integrated whole-process engineering consulting (WPEC) business models, this study establishes a WPEC competitiveness Influencing factor system to identify the factors influencing and interrelationships that affect competitiveness. By integrating the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM), the research identifies key competitiveness influencing factors and their impact pathways on competitiveness for engineering consulting enterprises to enhance WPEC Competitiveness. The primary research findings are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- This study identifies the WPEC competitiveness influencing factor System comprising 5 primary dimensions and 28 influencing factors. The dimensions include the Legacy-Industry Transition Foundation, Corporate Foundational Resources, Whole-Process Consulting Business Cultivation, Marketing Capability, and Corporate Full-Service Consulting Capability. This multi-dimensional structure provides a robust theoretical framework for understanding the essential requirements for Chinese engineering consulting enterprises during the transition from fragmented services to integrated consulting models.

- (2)

- The results base on AHP prioritize the identified factors, revealing that Corporate Full-Service Consulting Capability and Corporate Foundational Resources are the most critical pillars of competitiveness. These two dimensions collectively account for 80.96% of the total influence. Specifically, on-site quality and safety supervision and the information technology level are identified as the significant influencing factors. These findings provide a prioritized roadmap for enterprises to allocate their strategic resources effectively toward high-impact areas that yield the greatest competitive advantage.

- (3)

- The analysis of ISM delineates the hierarchical interrelationships and influence mechanisms among the competitiveness factors. The model organizes the factors into an eight-level structure and identifies three core action pathways including the resource-integration drive, the transfer of original industry capabilities, and service-awareness transformation. These pathways demonstrate that competitive advantage originates from fundamental drivers such as external resource integration and original business experience, which subsequently enhance intermediate service capabilities and ultimately manifest as superior market performance.

- (4)

- Finally, the case study involving BZ Consulting Enterprise demonstrates that the established system accurately matches the transformation pain points experienced during the shift to WPEC. The WPEC Competitiveness Influencing Factor System and the Multi-level Hierarchical Structural Model based on the AHP-ISM method effectively explain the practices of BZ Consulting Enterprise by identifying its core limitations and critical pathways.

Theoretically, this study provides a new perspective for whole-process engineering consulting by identifying the factors influencing the competitiveness of engineering consulting enterprises and their inherent interrelationships. By constructing the Multi-level Hierarchical Structural Model, this research delineates the critical pathways affecting the competitiveness of whole-process engineering consulting through three distinct dimensions, namely the resource-integration drive pathway, the original industry capability transfer pathway, and the service-awareness transformation pathway. These findings establish a systematic analytical framework for the comprehensive evaluation of whole-process engineering consulting performance. Practically, the indicator system established in this research provides a reliable reference for the development of whole-process engineering consulting business sectors. By analyzing critical dimensions such as the foundation of the legacy industry transition, corporate foundational resources, and whole-process consulting business cultivation, enterprises can identify the fundamental factors influencing the strategic transition toward integrated consulting services. This framework enables organizations to identify their internal strengths and weaknesses during the transformation process, allowing them to develop targeted enhancement strategies that ensure a sustainable competitive advantage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L., Q.Y. and P.L.; Methodology, M.L., J.Y., Q.Y. and J.W.; Software, J.Y. and Q.Y.; Validation, M.L., J.Y., Q.Y. and J.W.; Formal analysis, M.L., J.Y. and Q.Y.; Investigation, M.L., J.Y., J.W. and P.L.; Resources, M.L., J.Y., J.W. and Y.W.; Data curation, M.L., J.Y., Q.Y. and Y.W.; Writing—original draft, M.L., J.Y. and Q.Y.; Writing—review and editing, M.L., J.Y., J.W. and Y.W.; Visualization, J.Y., Q.Y. and Y.W.; Supervision, M.L., J.W. and P.L.; Project administration, M.L. and P.L.; Funding acquisition, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [72301018].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to the reason that survey research methodology was used and datasets were all anonymized and do not contain personal, identifiable data. The project raises no significant ethical issues.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are sincerely grateful to all the respondents who participated in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, S.; Su, H.; Hou, Q. Evolutionary game study on multi-agent value co-creation of service-oriented digital transformation in the construction industry. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Sun, H.; Lu, K.; Lyu, S.; Skitmore, M. Using evolutionary game theory to study construction safety supervisory mechanism in China. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 514–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bygballe, L.E.; Endresen, M.; Fålun, S. The role of formal and informal mechanisms in implementing lean principles in construction projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2018, 25, 1322–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanusi, B.O. The Role of Data-Driven Decision-Making in Reducing Project Delays and Cost Overruns in Civil Engineering Projects. SAMRIDDHI J. Phys. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 16, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsugair, A.M.; Al-Gahtani, K.S.; Alsanabani, N.M.; Hommadi, G.M.; Alawshan, M.I. An integrated DEMATEL and system dynamic model for project cost prediction. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Hu, Q.; Zhou, W.; Yang, P.; Liu, F.; Zhou, W. Transmission Mechanism of Influencing Factors in the Promotion and Application of Whole-Process Engineering Consulting. Buildings 2024, 14, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H. Research on Refined Management and Project Risk Control Strategies in Whole Process Engineering Consultation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Educational Information Technology, Chengdu, China, 22–24 March 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Xiong, Y. Analysis and related suggestions on the whole process engineering consulting service mode at home and abroad. Front. Res. Archit. Eng. 2021, 4, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, S.; Liang, B.; Wang, C.; Zhang, T. Analysis of Social Capital and the Whole-Process Engineering Consulting Company’s Behavior Choices and Government Incentive Mechanisms—Based on Replication Dynamic Evolutionary Game Theory. Buildings 2023, 13, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, H.; Hu, X.; Wang, G. Understanding Factors Influencing Whole-Process Consulting Service Quality: Based on a Mixed Research Method. Buildings 2025, 15, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanegas-Merchán, N.; Quintero-Mejorano, M.C.; Alzate-Ibanez, A.M. Improving service quality by strengthening culture: Implications for project management in an engineering consulting firm. DYNA 2025, 92, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, S. Interdisciplinary perspectives on agent-based modeling in the architecture, engineering, and construction industry: A comprehensive review. Buildings 2024, 14, 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujahed, L.; Feng, G.; Wang, J. Platform Approaches in the AEC Industry: Stakeholder Perspectives and Case Study. Buildings 2025, 15, 2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Zhao, J.; Guo, M. Evaluating the engineering-procurement-construction approach and whole process engineering consulting mode in construction projects. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2023, 47, 2533–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B.A. Optimizing Project Management Methodologies to Enhance Efficiency and Success in New Product Development. Ph.D. Thesis, Politecnico di Torino, Turin, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ayeni, O. Advanced Multi-Phase Project Management Frameworks: Optimizing AI-Driven Decision-Making, Risk Control, and Efficiency. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2025, 6, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Abbas, A. Reliability Assessment in Project Management: Integrating Life Cycle Approaches in Industrial Material Processing. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2025, 6, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Whole Process Engineering Consulting; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, N.; Takano, Y.; Muraki, M. An order acceptance strategy under limited engineering man-hours for cost estimation in Engineering–Procurement–Construction projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnajjar, O.; Atencio, E.; Turmo, J. Framework for optimizing the construction process: The integration of Lean Construction, Building Information Modeling (BIM), and emerging technologies. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wogan, M.; Mohan, N.; Wolf, G.; Nejat, N.; Menzel, K.; Gross, R. Synergising Lifecycle Project Management for Sustainability: Towards a Streamlined Approach through different Project Phases. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Civil Structural and Transportation Engineering, Toronto, ON, Canada, 13–15 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Ab Rahman, M.N.; Khamis, N.K. Quantifying the Impact of Lean Construction Practices on Sustainability Performance in Chinese EPC Projects: A PLS-SEM Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, M.A.; Uda, S.A.K. Reducing carbon emission in construction base on project life cycle (PLC). Proc. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 195, 06002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Cui, N.; Xue, S.; Du, Q. The impacts of whole life cycle project management on the sustainable development goals. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zeng, Y. Research on LID Technique Based on TFN-AHP Analysis Method. In Proceedings of the 2024 Asia-Pacific Conference on Software Engineering, Social Network Analysis and Intelligent Computing (SSAIC), Virtual, 10–12 January 2024; pp. 796–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Wang, Y.; Ning, Y. Configuring Governance Mechanisms to Improve the Engineering Consulting Project Performance. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2025, 151, 04025070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, K.; Wu, J.; Cao, Y. Study on the impact of trust and contract governance on project management performance in the whole process consulting project—Based on the SEM and fsQCA methods. Buildings 2023, 13, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S. Whole-Process Engineering Consulting Services-Research on Evaluation of Competence-Nantong Jianchen Engineering Consulting Co., Ltd. Master’s Thesis, Siam University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. Research on Development Model of Whole Process Engineering Consulting under New Situation. Twp Ser. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2020, 1, 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, K. Comprehensive Engineering Consulting Company to Carry out Whole-process Consulting Research. J. Civ. Eng. Urban Plan. 2023, 5, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin Lin, S.C.; Ali, A.S.; Alias, A.B. Analytic hierarchy process decision-making framework for procurement strategy selection in building maintenance work. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2015, 29, 04014050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Gao, C.; Chen, X.; Li, F.; Yi, D.; Wu, Y. Genetic algorithm optimised Hadamard product method for inconsistency judgement matrix adjustment in AHP and automatic analysis system development. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 211, 118689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-W.; Sohn, D.-G.; Sang, M.-G.; Lee, C. Empirical Analysis of Barriers to Collaborative Information Sharing in Maritime Logistics Using Fuzzy AHP Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, P.; Geng, L.; Niu, Z.; Jiang, S.; Sun, C. Network-Based Modeling of Lean Implementation Strategies and Planning in Prefabricated Construction. Buildings 2024, 14, 3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Meng, Q. Modeling adoption behavior of prefabricated building with multiagent interaction: System dynamics analysis based on data of Jiangsu Province. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2021, 2021, 3652706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maseko, L.; Rotimi, J. Collaborative Risk Management and Dependency Structure Matrix in Green Building Designs: A Synthesis. In Creating Capacity and Capability: Embracing Advanced Technologies and Innovations for Sustainable Future in Building Education and Practice: Innovations and Technologies in Building and Construction, Volume III; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; Volume 564, pp. 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.-G.; Wei, H. A comprehensive evaluation of China’s TCM medical service system: An empirical research by integrated factor analysis and TOPSIS. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 532420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, H.M.; Alotaibi, S.S.; Ansari, M.T.J.; Asiri, M.M.; Agrawal, A.; Khan, R.A.; Mohsen, H.; Hilal, A.M. Analysis and ranking of IT risk factors using fuzzy TOPSIS-based approach. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsadini, K.; Askari Shahamabad, M.; Askari Shahamabad, F. Analysis of factors affecting environmental audit (EA) implementation with DEMATEL method. Soc. Responsib. J. 2023, 19, 777–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, X. Analysis of factors affecting economic operation of electric vehicle charging station based on DEMATEL-ISM. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 163, 107818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yi, Y.; Wang, X. Exploring factors influencing construction waste reduction: A structural equation modeling approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 123185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K.; Kumar, H.; Gupta, M.P.; Madaan, J. Competitiveness of Electronics manufacturing industry in India: An ISM–fuzzy MICMAC and AHP approach. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2018, 22, 88–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Li, Q.; List, G.F.; Deng, Y.; Lu, P. Using an AHP-ISM based method to study the vulnerability factors of urban rail transit system. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Sohani, N.; Yadav, A. Structural modeling of lean supply chain enablers: A hybrid AHP and ISM-MICMAC based approach. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2023, 21, 1658–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkos, F.D.; Kerenso, P.G. Integrating interdependencies of housing performance indicators using fuzzy-AHP, ISM, and quadrant analysis. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 30, 100354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akmaludin, A.; Suriyanto, A.D.; Iriadi, N.; Santoso, B.; Wahid, B.A. Application of the AHP-ELECTRE Method for Selection OOP Based Apps Programs. Sink. J. Dan Penelit. Tek. Inform. 2022, 6, 2231–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.K.; Goswami, S.S. A comprehensive review of multiple criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods: Advancements, applications, and future directions. Decis. Mak. Adv. 2023, 1, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugingo, E.; Ndimubenshi, E.L. Application of AHP in Decision-Making: Case Studies. In The Art of Decision Making-Applying AHP in Practice Applying AHP in Practice; BoD—Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2025; p. 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Marconi, V.C. Code Saturation Versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough? Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.-C.; Ri, J.-B.; Yang, J.-Y.; Kim, J.-S. Materials selection criteria weighting method using analytic hierarchy process (AHP) with simplest questionnaire and modifying method of inconsistent pairwise comparison matrix. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2022, 236, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-N.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Dang, T.-T.; Nguyen, N.-A.-T. A hybrid OPA and fuzzy MARCOS methodology for sustainable supplier selection with technology 4.0 evaluation. Processes 2022, 10, 2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Tian, X.; He, Z. Analysis of influencing factors consulting mode in promotion of whole-process engineering based on DEMATEL-ISM. J. Changsha Univ. Sci. Technol 2021, 18, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, F.; Wu, J.; Li, Y. Configurational Pathways for Fintech-Empowered Sustainable Innovation in SRDIEs Under Financing Constraints. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Chen, Y.; Cao, T. Integrated construction consulting project performance improvement in China using network structure and team boundary-spanning behavior: A configurational analysis. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 31, 4462–4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jin, Y.; Meng, Q.; Chong, H.-Y. Evolutionary Game Analysis of the Opportunistic Behaviors in PPP Projects Using Whole-Process Engineering Consulting. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2024, 30, 04024021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Taumaturgo, A.C.; de Alencar, D.B.; Júnior, J.d.A.B.; da Silva, W.Í.M.; de Oliveira, S.R.C. Improvement of the Construction Process with Implementation of Regulatory Standard No. 35 (Nr-35). ITEGAM-JETIA 2019, 5, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-H.; Sun, L.; Ger, T.-B. An analysis of enterprise resource planning systems and key determinants using the Delphi method and an analytic hierarchy process. Data Sci. Financ. Econ. 2023, 3, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.