Abstract

The large-scale generation and disposal of fly ash pose significant environmental concerns, highlighting the need for its sustainable reuse in geotechnical applications. This study investigates the performance of fly ash blended with polypropylene fiber as an infill material in geocell-reinforced sand beds to enhance bearing capacity and reduce settlement. Plate load tests were conducted in the laboratory by varying geocell mattress height, cement content, fiber content, and curing period. The results showed that polypropylene fibers improved the shear strength of the fly ash mix. Increasing the geocell mattress height from 0.5B to 1B enhanced the ultimate bearing pressure of a sand bed by 3.4×. At a mattress height of 1B, an improvement factor of 13.18 was achieved at a settlement (s/B) of 12.5%, and this improvement is attributed to confinement provided by the geocell because of enhanced load distribution. Fly ash mix with 6% polypropylene fiber and 5% cement yielded an ultimate bearing pressure of 460 kPa after 3 days of curing, which was 6.9× higher than that of an unreinforced sand bed. These findings demonstrate that fiber-reinforced fly ash is a sustainable and efficient infill material for geocell mattresses, offering both environmental benefits and improved geotechnical performance.

1. Introduction

Ground improvement techniques are employed to modify the engineering behavior of foundation soils that are weak, highly compressible, or susceptible to excessive settlement and liquefaction. In the past decade, geosynthetics have become an integral component of ground improvement practice because they enhance soil performance through mechanisms such as reinforcement, stabilization, filtration, drainage, and containment [1,2,3]. The geosynthetic family includes geotextiles, geogrids, geonets, geomembranes, and geocells. Among these, geocells offer distinct advantages owing to their three-dimensional cellular configuration.

Geocells are typically fabricated from high-density polyethylene strips bonded through high-strength thermal welding techniques, such as ultrasonic welding, to form a honeycomb-like network. Unlike planar reinforcement systems, geocells act as a three-dimensional confinement medium, providing superior lateral restraint to the infilled material. This confinement mechanism makes geocells effective in enhancing the performance of foundations, pavements, railways, and embankments under static and cyclic loading conditions [4,5,6,7].

The improvement achieved through geocell reinforcement depends on several factors, including the geometry of the geocell, its depth of placement, and the mechanical properties of the infill material [8,9]. Cellular confinement restricts the lateral displacement of soil particles and facilitates load distribution over a wider influence area [10]. The geocell system increases bearing capacity primarily by mobilizing apparent cohesion within the infill, which is attributed to hoop tension and lateral strain within the cell walls [11]. Maximum hoop stresses typically develop in the central cells of a mattress and reduce towards the edges; these stresses also increase with greater tensile stiffness of the cell walls [12]. Fundamentally, geocells mitigate imposed stresses on weak subgrades without substantial alteration of the underlying soil structure.

Chevron-patterned geocells exhibit enhanced structural rigidity because they contain a greater number of welded joints per unit area. In addition to providing passive resistance against lateral shear displacement, the cell walls intersect potential failure planes, thereby modifying the stress transfer mechanism. The improvement imparted by geocell layers is mainly associated with three mechanisms: lateral confinement, vertical stress dispersion, and the membrane effect [13,14,15]. Studies have shown substantial increases in the bearing capacity and stiffness of fly ash beds reinforced using geocell mattresses, along with noticeable reductions in permanent deformation [16,17]. Geocell reinforcement has also been found to reduce surface heaving, and the load-carrying capacity generally increases with the number of geocell layers, independent of the settlement ratio [18,19,20].

When a jute geotextile separator was introduced below an unreinforced fly ash bed, the bearing pressure approximately doubled. However, when the fly ash was reinforced with a geocell mattress in combination with a basal bamboo geogrid and jute separator, the bearing capacity increased nearly sevenfold [21]. Reducing the opening size of geocell cells has also been shown to improve performance, as smaller cells offer stronger confinement and more effectively restrict lateral deformation of the infill material [8,22].

Fiber-reinforced fly ash exhibits behavior that transitions from brittle to ductile as the fiber length increases. Incorporation of discrete fibers enhances the deviator stress at failure and improves shear strength parameters. Increases in fiber content and fiber length both contribute to higher peak strength and improved post-peak response. Randomly distributed fibers act as frictional and tensile elements that interact with fly ash particles, improving load–deformation characteristics and contributing to a more ductile failure mode [23,24].

Application of finite element methods (FEM) to model geocell-reinforced and geosynthetic-supported ground systems allows detailed analysis of stress distribution, confinement effects, and load–settlement behavior under various loading conditions. Numerical investigation using ABAQUS demonstrated that optimized combinations of geocell geometry and infill properties can enhance the load-carrying capacity of footings on weak soils several times over unreinforced cases [25]. Similarly, 3-D FEM studies of geocell-reinforced embankments and pavement bases have shown how reinforcement depth, interface friction, and infill stiffness influence settlement reduction and bearing capacity improvement [26,27].

In recent years, research on geocell-reinforced systems has shifted towards performance-based optimization, establishing that geocell behavior is highly sensitive to geometric and material parameters [28]. Optimized geocell configurations provide superior lateral restraint and improved stress dispersion mechanisms when compared with conventional designs. These advancements have enabled geocell systems to evolve from simple confinement devices into highly engineered structural elements capable of tailoring soil performance for specific applications. Experimental and FEM-based studies have shown that increasing cell height, refining pocket geometry, and improving weld density enhance lateral confinement, minimize shear distortion, and promote more uniform stress distribution [29,30]. Parallel developments in fiber-geocomposites have introduced engineered synthetic fibers with optimized aspect ratios, surface texturing, and hybrid configurations, which improve soil-fiber bonding, delay shear band formation, and enhance ductility and energy absorption [31]. Simultaneously, the growing emphasis on sustainable geotechnical materials has encouraged the use of high-volume fly ash as an environmentally responsible infill alternative [13,32].

The proposed study provides new insights into the combined action of polypropylene fibers, cement, and geocell confinement when used together as an infill system. While past studies have examined geocells with either sand, fly ash, or fiber-reinforced soils individually, the present work quantifies how the synergistic interaction of tensile bridging by fibers, pozzolanic bonding by cement, and three-dimensional confinement by geocells significantly enhances the bearing pressure–settlement performance. The research also identifies the influence of mattress height, fiber content, cement content, and short-term curing on improvement factor, offering a new understanding of how composite infill behavior changes under geocell confinement.

2. Materials

2.1. Sand

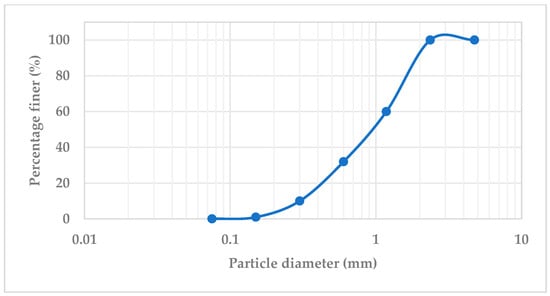

Sand was collected from Shanthi Materials Suppliers, Kovilampakkam, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. The properties of the collected sand were evaluated and are presented in Table 1. Grain size distribution analysis was carried out in accordance with IS 2720(part 4)-1985 [33] which is presented in Figure 1. The maximum and minimum density of sand were determined by conducting relative density testing as per IS 2720 (part 14)-1983 [34]. Specific gravity testing for sand was carried out by the density bottle method in accordance with IS 2720 (part 3/sec 1)-1980 [35]. The internal friction of sand was found to be 36.23° through the direct shear test conducted for a relative density of 60%.

Table 1.

Properties of sand.

Figure 1.

Particle size distribution curve of sand.

2.2. Cement

Ordinary Portland cement of grade 53 used was procured from A6 Enterprises, Kotturpuram, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. The cement consists of crystalline compounds of calcium combined with silica, alumina, iron oxide, and sulfate. The initial setting time and consistency of the ordinary Portland cement of grade 53 were determined as per IS 4031 (parts 4 and 5)-1988 [36]. The initial setting time and the consistency of the cement were found to be 46 min and 37%, respectively.

2.3. Fly Ash

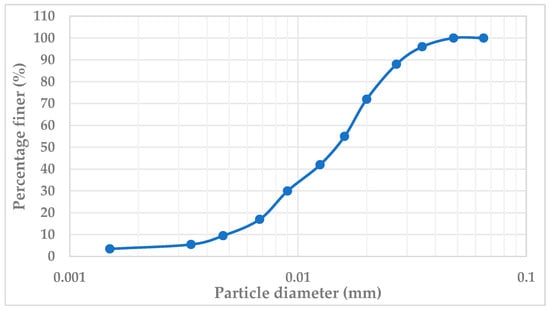

Class F fly ash, collected from Ennore Thermal Power Station, Ennore, Tamil Nadu, India was used as the foundation medium (Figure 2). The properties of the fly ash as listed in Table 2 were determined in the laboratory. Grain size distribution analysis and specific gravity testing were carried out for class F fly ash. The particle size distribution curve of fly ash is presented in Figure 3. The shear strength parameters of the fly ash were determined by Direct shear test as per IS 2720 (part13)-1986 [37]. The compaction characteristics of the class F fly ash were determined using the standard proctor compaction method specified in IS 2720 (part 7)-1980 [38]. From the compaction curve obtained, the optimum moisture content and the maximum dry density of the fly ash were found to be 25.25% and 1.226 g/cc, respectively.

Figure 2.

Class F fly ash.

Table 2.

Properties of fly ash.

Figure 3.

Particle size distribution curve of fly ash.

2.4. Polypropylene Fiber

Polypropylene fibers with a nominal length of 12 mm (Figure 4) were obtained from Fiber Region Company, Valasaravakkam, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. These fibers were blended with fly ash to produce a uniform fiber–fly ash mixture, which served as the foundation material for the plate load experiments. The key physical and mechanical properties of the fibers are presented in Table 3. Fiber inclusion levels of 2%, 4%, and 6% (by dry weight of fly ash) were adopted to evaluate the influence of fiber dosage on the composite behavior.

Figure 4.

Polypropylene fibers.

Table 3.

Properties of polypropylene fiber.

2.5. Geocell

Geocells are three-dimensional geosynthetic systems designed to confine and stabilize the infill material through a honeycomb-like cellular arrangement. In this investigation, high-density polyethylene (HDPE) geocells were used as the reinforcement layer. The geocell mattresses were sourced from Taian Road Engineering Materials, Taian City, China. The tensile modulus and strength of the geocell strips were determined through wide-width tensile tests conducted in the laboratory. The geometric and mechanical characteristics of the geocell are summarized in Table 4. Three geocell heights, corresponding to 63.5 mm (0.5 B), 5.25 mm (0.75 B), and 127 mm (1.0 B) were adopted to study the influence of mattress depth on the system’s performance.

Table 4.

Properties of Geocell.

3. Methods

3.1. Direct Shear Test

The shear strength parameters of fly ash blended with different fiber proportions (2%, 4%, and 6%) and cement contents (5% and 10%) were evaluated through a series of direct shear tests. A standard direct shear apparatus equipped with a 60 mm × 60 mm shear box was used for the testing program [37]. To examine how variations in fiber dosage and cement content affect the shear strength behavior of the fly ash, the tests were conducted under normal stresses of 50 kPa, 100 kPa, and 150 kPa.

3.2. Plate Load Test

3.2.1. Experimental Setup

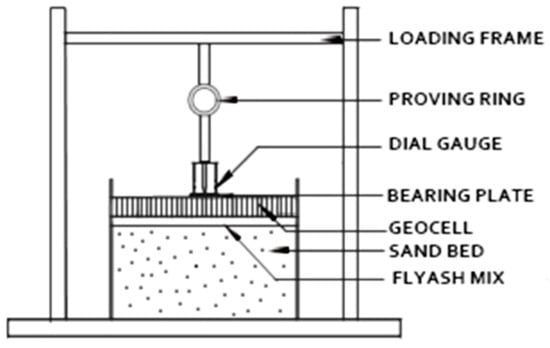

A plate load test was carried out in accordance with IS 1888:1982 [39] to evaluate the bearing pressure–settlement behavior of the different foundation beds. The experiments were performed in a mild steel model tank with internal dimensions of 730 mm × 600 mm × 600 mm. A 12 mm-thick square steel plate measuring 127 mm × 127 mm was used to simulate the footing. Figure 5 illustrates the schematic arrangement of the test setup.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of load test setup.

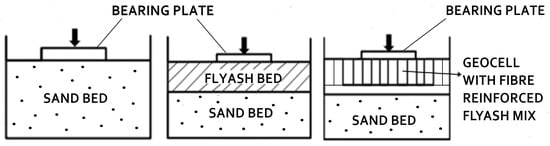

The vertical load was applied through a 20 kN capacity hydraulic jack supported against a rigid steel reaction frame. The applied load was monitored using a proving ring, while the settlement of the footing plate was measured using dial gauges. Compaction of the foundation medium was carried out using a 150 mm × 150 mm steel base plate, a 500 mm long guide rod (10 mm diameter), and a 23.6 N cylindrical drop hammer. Three foundation bed configurations were examined: sand bed alone; fly ash bed overlying sand bed; and fiber–fly ash–cement mix used as geocell infill placed above an underlying sand bed (Figure 6). The geocell mattress was positioned at an optimum depth of 0.1 B as recommended by earlier studies [40].

Figure 6.

Schematic view of model tank illustrating the test configuration.

3.2.2. Sample Preparation

The infill material for the geocell mattress consisted of fly ash blended with polypropylene fibers and OPC. A two-stage mixing procedure was adopted to ensure uniform fiber dispersion. First, the fibers were gradually sprinkled over the fly ash while continuously dry-mixing by hand to avoid clumping. This was followed by mechanical mixing for approximately 5 min to achieve a uniform distribution of fibers throughout the matrix. This procedure, commonly recommended in fiber-reinforced soil studies, effectively prevents fiber balling and ensures consistent composite response [41]. The required quantity of water was calculated as [OMC × Weight of fly ash] + [Cement consistency × Weight of cement].

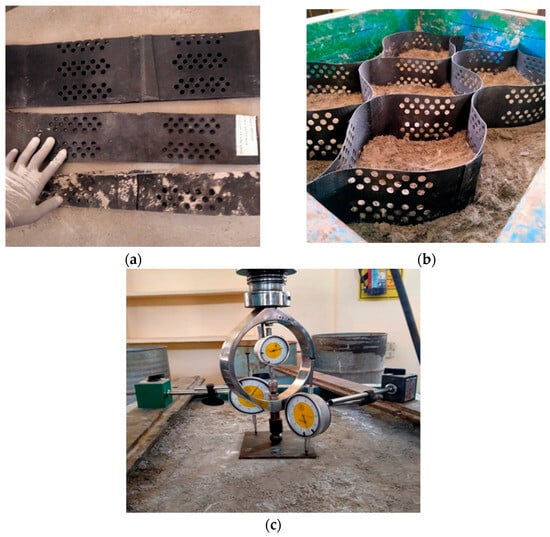

3.2.3. Geocell Mattress Preparation

The infill material was placed in layers of 50 mm thickness and lightly compacted to achieve the maximum dry density of 1.226 g/cc at an OMC of 25.25%. After compaction of each layer, dry density was verified at three locations using the bulk density measurement method to ensure that variations remained within ±3% of the target value. Only after confirming uniform density across the layer was the next layer placed. This procedure ensured uniform density throughout the geocell mattress. The preparation and placement of the geocell mattress used in the plate load tests are illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

(a) Geocell mattress of H = 0.5 B, 0.75 B, and 1 B, (b) Placement of geocell mattress with underlying sand bed, and (c) Experimental setup of geocell-reinforced sand bed with fiber reinforced fly ash mix as infill material for plate load test.

3.2.4. Test Program

The plate load test was carried out with varying parameters such as polypropylene fiber content, height of HDPE geocell mattress, cement content, and curing period. The test configurations are presented in Table 5. Parameters that were kept as constant for all tests were width of geocell (b = 4.4 B), placement depth of geocell (U = 0.1 B), diameter of geocell pockets (d = 2.21 B), embedment depth (Df / B = 0), and number geocell layers (N = 1). Each configuration was tested once due to the time and material requirements of specimen preparation and curing. Consequently, statistical metrics, such as standard deviation or range, could not be reported. Nevertheless, strict control of density, meticulous mixing, and a uniform loading rate were implemented to minimize variability and improve test repeatability.

Table 5.

Test variables and study parameters.

Improvement factor (If) was used to quantify performance enhancement. It is defined as the ratio of the bearing pressure of the geocell-reinforced fly ash composite bed (overlying sand) to that of the unreinforced sand bed for the same settlement level. Footing settlement values are expressed in the non-dimensional form s/B (%).

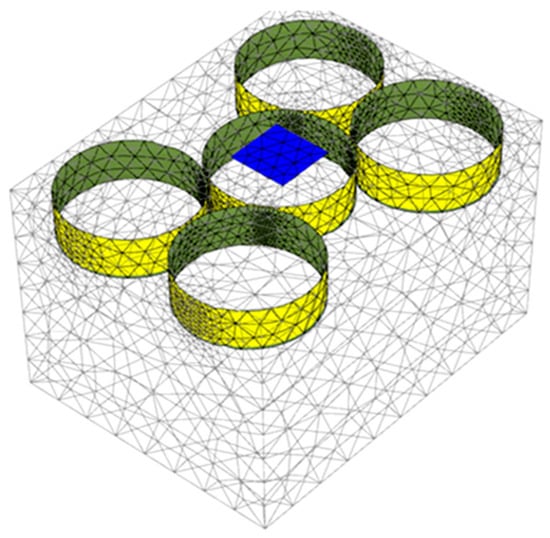

3.3. Numerical Analysis

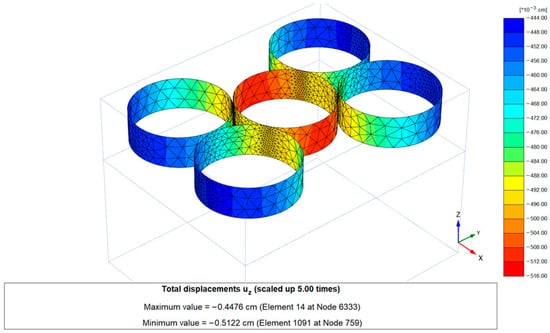

A three-dimensional finite element model as shown in Figure 8 was developed in PLAXIS 3D to simulate the behavior of geocell-reinforced fly ash beds with varying mattress heights. Geocells were generated using polycurves and extruded to the required height, with node-to-node anchor elements assigned to represent seam stiffness. A linear-elastic geogrid material combined with interface elements was used to capture soil–geocell interaction. The footing was modeled as a 127 mm × 127 mm linear-elastic plate at the center of the bed, and settlement was obtained from the computed deformation patterns [12,42].

Figure 8.

Mesh distribution in 3D finite element model of geocell-reinforced fly ash mix bed.

The composite infill was represented using the Mohr-Coulomb model, which has been widely adopted for granular and lightly cemented materials due to its ability to capture the dominant shear failure mechanism with minimal computational demand [43,44]. The fly ash-fiber-cement infill was represented as a homogenized composite material, as direct modeling of discrete polypropylene fibers is not computationally practical. The equivalent material properties were obtained from laboratory tests. Model parameters were calibrated by matching numerical and experimental stress–strain and load–settlement responses. This calibration approach has been widely adopted for composite infill materials whose properties cannot be directly defined due to heterogeneity. The input parameters adopted in the FEM analysis are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Numerical model parameters.

For computational efficiency, the geocell was idealized as a circular connected-ring system rather than a honeycomb geometry; previous studies have shown that this simplification preserves confinement behavior and global load response while reducing meshing complexity [19,28]. Therefore, the circular representation used in this study captures the macro-scale behavior of geocell-reinforced foundations. Interface strength between soil and geocell was assigned using an Rinter value of 0.9, consistent with a typical HDPE–granular interaction.

Boundary conditions were defined by fixing the base in all directions and restraining lateral movement at the tank sides. Sensitivity checks confirmed negligible influence of boundary distance and base fixity on peak load response. Increasing the tank boundary distance by 50% resulted in less than 3% variation in peak bearing capacity, confirming that the selected boundaries were sufficiently far to prevent confinement effects. Mesh refinement studies were also performed, and a medium mesh was adopted after convergence was achieved with less than 5% variation in results. A mesh convergence analysis was conducted by progressively refining the element size until further refinement resulted in less than 5% change in the peak load and settlement response. The medium mesh was earmarked for further investigation, which ensured numerical stability and accurate capture of stress distribution within the geocell mattress.

4. Results and Discussions

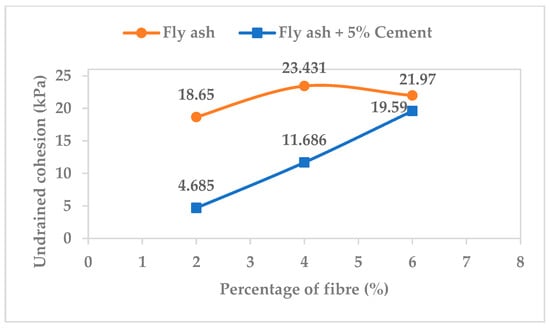

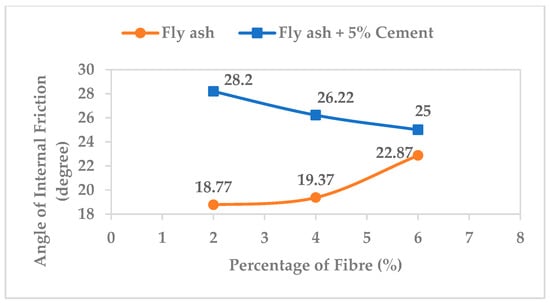

4.1. Shear Strength Parameters of Fiber Reinforced Fly Ash Mix

The influence of polypropylene fiber content on the shear strength of fiber-reinforced fly ash was evaluated through direct shear tests at 2%, 4%, and 6% fiber dosages. Figure 9 shows a marginal increase in undrained cohesion with fiber addition. When 5% cement was included, cohesion increased significantly with higher fiber content. Figure 10 indicates that while fiber alone slightly increased the internal friction angle, the addition of cement reduced it. Increasing the cement content enhanced the soil’s shear strength by raising the undrained cohesion while slightly reducing the internal friction angle [45]. At a normal stress of 150 kPa, the shear strength of fly ash with 2% fiber increased by 22% with 5% cement compared to fiber-only fly ash, whereas further increasing cement to 10% showed negligible additional improvement (85.0 kPa vs. 86.13 kPa).

Figure 9.

Effect of fiber content on undrained cohesion of fly ash mix.

Figure 10.

Effect of fiber content on angle of internal friction of fly ash mix.

The improvement in shear behavior arises from micro-interactions between fibers, fly ash particles, and the cementitious matrix. Polypropylene fibers disrupt the development of a continuous shear plane by bridging emerging cracks and mobilizing tensile resistance as deformation progresses [46]. At small displacements, fiber–matrix friction provides confinement, while at larger strains, fiber pull-out contributes to energy dissipation. Concurrently, cement hydration forms C-S-H gels that bond neighboring particles and enhance fiber anchorage [47]. Together, these mechanisms increase peak shear strength and improve ductility under shearing.

4.2. Effect of Geocell Mattress Height on Bearing Pressure—Settlement Response of Footing

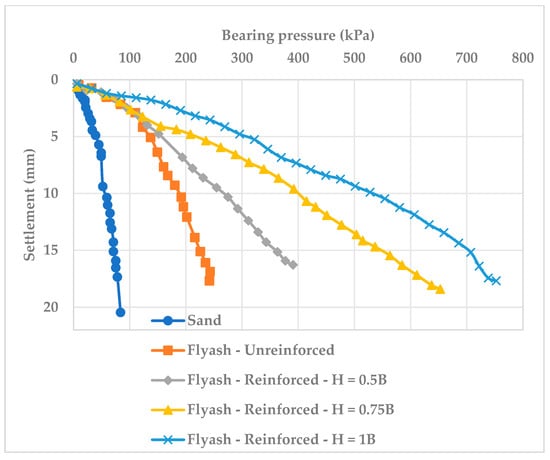

Bearing pressure—settlement response was studied for a geocell mattress of height H = 0.5 B, 0.75 B, and 1 B. The geocell-reinforced sand bed was prepared with fly ash mix as infill material blended with 2% polypropylene fiber and 5% cement. From the bearing pressure–settlement curve shown in Figure 11, it was observed that ultimate bearing pressure of 575 kPa was achieved at a settlement of 6 mm when H = 1 B. The ultimate bearing pressure of the foundation bed increased 3.4× when H increased from 0.5 B to 1 B. From the bearing pressure–settlement response, it is evident that increase in the height of geocell mattress improved the bearing pressure value due to better confinement to the infill fiber reinforced fly ash mix [48].

Figure 11.

Bearing pressure versus settlement curves of sand bed; unreinforced fly ash mix and geocell-reinforced fly ash mix (fly ash + 2% fiber + 5% cement) with underlying sand bed for varying height of geocell mattress.

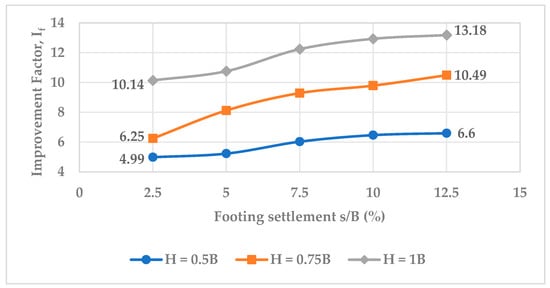

Maximum bearing pressure improvement factor of 13.18 was obtained for s/B = 12.5% for the geocell mattress of height H = 1 B (Figure 12). This was achieved due to the higher lateral confinement of the geocell mattress to the infilled fiber reinforced fly ash material and higher frictional resistance mobilized along the vertical surface of the geocell.

Figure 12.

Improvement factor corresponding to footing settlement for varying height of geocell mattress.

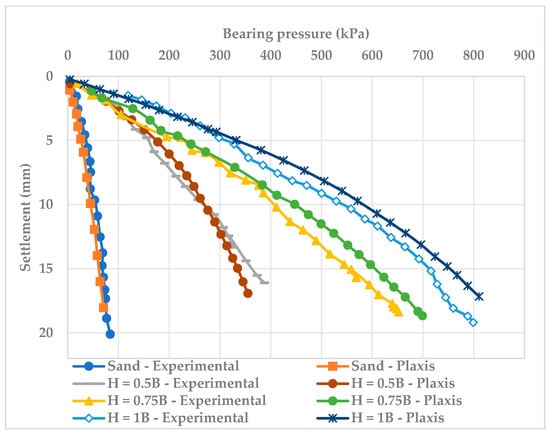

Numerical results were validated with the obtained experimental results of geocell-reinforced sand bed for varying geocell mattress height as H = 0.5 B, 0.75 B and 1 B. The bearing pressure–settlement response for different heights of the geocell mattress, illustrated in Figure 13, proves that both the experimental and numerical method curves follow the same trend.

Figure 13.

Comparison of experimental and numerical bearing pressure–settlement curve of sand bed and geocell-reinforced fly ash mix (Fly ash + 2% fiber + 5% cement) with underlying sand bed for varying height of geocell mattress.

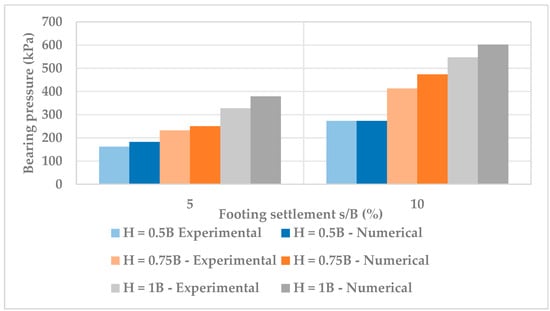

From Figure 14, it is evident that the bearing pressure values obtained by the experimental and numerical methods showed a deviation of less than 16%. It is observed that the geocell mattress of height H = 1 B gave the maximum value of bearing pressure, which indicates a better footing response for increased height of the mattress. For both s/B of 5% and 10%, same pattern of improvement was seen in the bearing pressure values. When the height of the geocell mattress was H = 1 B, the bearing pressure values were obtained as 546.84 kPa and 601.78 kPa from experimental and numerical analyses, respectively, for the footing settlement of s/B = 10%.

Figure 14.

Comparison of experimental and numerical bearing pressure corresponding to footing settlement for varying height of geocell mattress.

The displacement contour of the geocell mattress of H = 0.75 B after the application of load is shown in Figure 15. From the displacement pattern, it is evident that the cells that are away from the footing have undergone minimum deformation when compared with the cell at the center [49]. The cells which were under the footing plate underwent maximum settlement of 3.634 mm, 5.122 mm, and 6.163 mm for the geocell mattress of height H = 0.5 B, 0.75 B and 1 B, respectively.

Figure 15.

Displacement pattern of the geocell mattress for H = 0.75 B from Plaxis 3D.

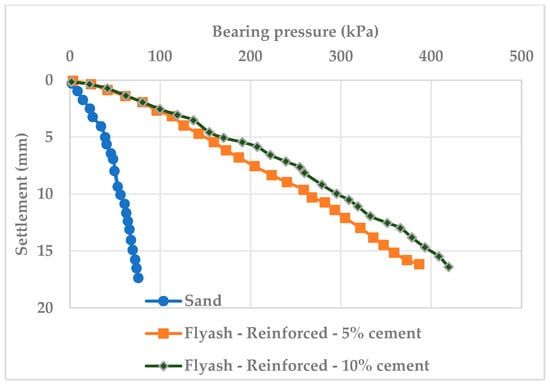

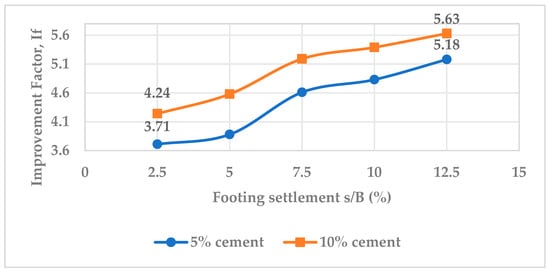

4.3. Effect of Cement Content on Bearing Pressure—Settlement Response of Footing

To investigate the effect of cement content (5% and 10%) on the behavior of geocell-reinforced fly ash mix over a sand bed, the polypropylene fiber content was kept constant at 2% and the geocell mattress height at 0.5 B. As shown in Figure 16, the ultimate bearing pressure increased with higher cement content, reaching a maximum of 183 kPa at a settlement of 3.2 mm for 10% cement. This value is 2.7× greater than the ultimate bearing pressure of unreinforced sand. An improvement factor of 5.63 was observed at s/B = 12.5% for the fly ash mix with 2% fiber and 10% cement infill (Figure 17).

Figure 16.

Bearing pressure versus settlement curves of sand bed, and geocell (H = 0.5 B) reinforced fly ash mix (Fly ash + 2% fiber) with underlying sand bed for varying cement content.

Figure 17.

Improvement factor corresponding to footing settlement for varying cement content.

The improvement in bearing capacity with increasing cement content is due to the progressive cementation of the fly ash matrix. Hydration and pozzolanic reactions generate C-S-H gels that bond particles, fill microvoids, and restrict particle sliding and compressive deformation. Together with geocell confinement, the cement-stabilized infill behaves as a stronger, more rigid block, resulting in improved load distribution and reduced settlement [50,51].

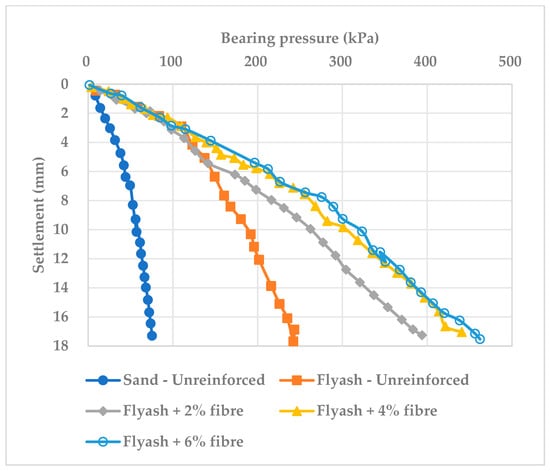

4.4. Effect of Fiber Content on Bearing Pressure—Settlement Response of Footing

The bearing pressure–settlement behavior for the geocell-reinforced sand bed was analyzed with varying polypropylene fiber contents of 2%, 4%, and 6% in the fly ash infill, as shown in Figure 18. The geocell mattress height was maintained constant at H = 0.5 B. The results indicate that increasing the fiber content enhances the bearing pressure response of the footing. For the fly ash mix with 6% polypropylene fiber, the ultimate bearing pressure reached 249 kPa. The corresponding ultimate settlements for 2%, 4%, and 6% fiber content were 5.1 mm, 5 mm, and 5.2 mm, respectively, suggesting that the fiber content has minimal effect on the ultimate settlement of the foundation.

Figure 18.

Bearing pressure versus settlement curves of sand bed; unreinforced fly ash mix and geocell (H = 0.5 B) reinforced fly ash mix with underlying sand bed for varying fiber content.

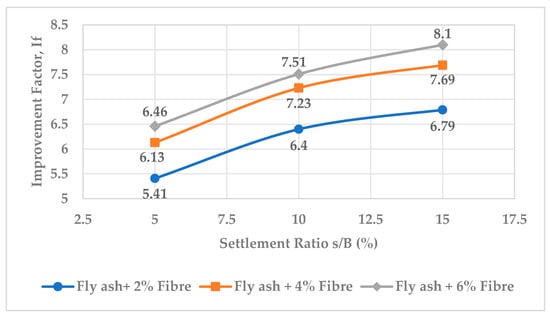

From Figure 19, it was observed that the improvement factor was 6.79 for s/B = 15% for a mix of fly ash with 2% fiber, as infill material in a geocell mattress of height 0.5 B. The improvement factor for the same settlement level was found to increase by 19% for the mix of fly ash with 6% fiber content as infill material. This proves that the increase in the percentage of polypropelene fiber enhanced the bearing pressure of the fly ash mix with an underlying sand bed, resulting in a better bearing pressure—settlement response [52,53].

Figure 19.

Improvement factor corresponding to footing settlement for varying fiber content.

The increase in bearing capacity with higher fiber content results from improved stress transfer within the confined infill. Fibers act as tensile bridges that intersect potential shear zones and provide lateral restraint inside each geocell pocket. Their frictional and mechanical interaction with fly ash particles increases resistance to shear deformation and limits lateral spreading. This bridging effect enhances ductility and enables the more effective mobilization of geocell confinement under load.

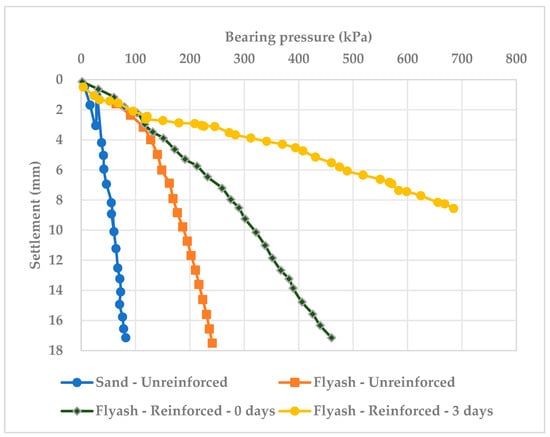

4.5. Effect of Curing Period on Bearing Pressure—Settlement Response of Footing

The effect of curing period on the bearing capacity of the fly ash mix used as infill for the geocell-reinforced sand bed was evaluated for 0-day and 3-day curing periods. The infill comprised 6% polypropylene fiber and 5% cement, with the geocell mattress height maintained at H = 0.5 B. The bearing pressure–settlement curves, shown in Figure 20, indicate ultimate bearing pressures of 225 kPa and 460 kPa for 0-day and 3-day curing, respectively. This represents a 104% increase in ultimate bearing pressure after 3 days, attributed to the progressive pozzolanic reactions that enhanced the stiffness of the fly ash mix.

Figure 20.

Bearing pressure versus settlement curves of sand bed; unreinforced fly ash mix and geocell (H = 0.5 B) reinforced fly ash mix (fly ash + 6% fiber + 5% cement) with underlying sand bed for varying curing periods.

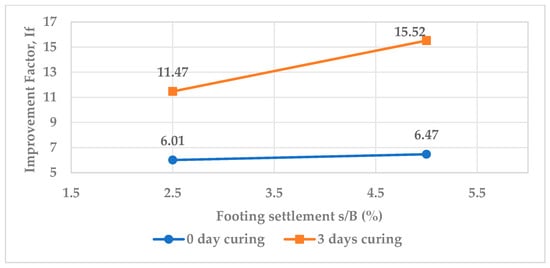

The improvement factor of 15.52 for the 3-day cured mix is illustrated in Figure 21. The strength gain over time results from cementitious compounds formed through hydration and pozzolanic reactions, including calcium silicate hydrates, calcium aluminate hydrates, and calcium aluminum silicate hydrates. This densifies the microstructure, reduces pore connectivity, and enhances particle bonding, thereby increasing the stiffness and load-carrying capacity of the infill [54].

Figure 21.

Improvement factor corresponding to footing settlement for varying curing periods.

5. Conclusions

- This study demonstrates that the combined effects of fiber inclusion, cement stabilization, and geocell confinement substantially enhance the mechanical behavior of fly-ash-based foundation beds. Increasing fiber content produced higher shear strength and improved ductility by promoting tensile bridging and delaying shear localization within the mix. The addition of cement further strengthened the composite by forming C–S–H gels that bonded fly ash particles and contributed to a stiffer load-bearing skeleton. In the plate load tests, geocell height emerged as a key design variable, with taller mattresses (H = 1 B) providing superior lateral confinement and yielding the highest improvement factors. Similarly, higher fiber dosages and cement contents increased bearing capacity by modifying stress transfer mechanisms and improving the integrity of the infill under repeated loading. The influence of curing time was also evident, as short-term (3-day) hydration significantly increased stiffness and reduced settlement.

- The results demonstrate the combined reinforcement mechanism of tensile resistance from fibers, cementitious bonding from cement, and lateral confinement from the geocell. This composite produces improvement factors significantly higher than those achieved by any component when used individually. The enhancement in bearing capacity and the reduction in settlement is governed primarily by geocell height, fiber dosage, cement content, and curing period. The study provides experimentally validated design insights for selecting geocell dimensions and infill compositions when using high-volume fly ash as a sustainable replacement for conventional aggregates. The FEM analysis further confirms the experimental trends and offers a practical modeling framework for future parametric optimization.

- Overall, the findings advance the design of sustainable, mechanically enhanced geocell-reinforced foundations and support the broader adoption of industrial by-products in geotechnical engineering. While the findings offer clear guidance for sustainable geocell-reinforced foundation design, the study is limited by the use of small-scale laboratory models, a single fiber type, and short curing durations. Future work should incorporate long-term durability assessments, field-scale validation, and advanced constitutive modeling to further generalize the results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.T. and V.K.S.; methodology, V.K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.T.; writing—review and editing, V.K.S.; project administration, V.K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering Division, Anna University, Chennai, for providing necessary facilities and support during the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FEM | Finite element method |

| SP | Poorly graded sand |

| RD | Relative density |

| HDPE | High-density polyethylene |

| H | Height of geocell mattress |

| B | Width of bearing plate |

| OMC | Optimum moisture content |

| DST | Direct shear test |

References

- Markiewicz, A.; Koda, E.; Kawalec, J. Geosynthetics for Filtration and Stabilization: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.R.; Huang, M.S.; He, S.Q.; Song, G.F.; Shen, R.Z.; Huang, P.Z.; Zhang, G.F. Erosion Control Treatment using Geocell and Wheat Straw for Slope Protection. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5553221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuelho, E.V.; Perkins, S.W. Geosynthetic subgrade stabilization—Field testing and design method calibration. Transp. Geotech. 2017, 10, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Zhang, M. Performance and Application of Geocell Reinforced Sand Embankment under Static and Cyclic Loading. Coatings 2022, 12, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astaraki, F.; Esmaeili, M.; Reza, R.M. Influence of geocell on bearing capacity and settlement of railway embankments: An experimental study. J. Geomech. Geoengin. 2022, 17, 630–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingle, J.S.; Jersey, S.R. Cyclic plate load testing of geosynthetic-reinforced unbound aggregate roads. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board. 2005, 1936, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Puppala, A.J. Sustainable pavement with geocell reinforced reclaimed-asphalt-pavement (RAP) base layer. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 387, 135802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherin, K.S.; Chandrakaran, S.; Sankar, N. Effect of Geocell Geometry and Multi-layer System on the Performance of Geocell Reinforced Sand Under a Square Footing. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2017, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, E.C.; Kang, H.H.; Park, J.J. Reinforcement efficiency of bearing capacity with geocell shape and filling materials. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2017, 21, 1648–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshchinsky, B.; Ling, H. Effect of geocell confinement on strength and deformation behaviour of gravel. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2013, 13, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, M.; Shi, C.; Zhao, H. Bearing capacity of geocell reinforcement in embankment engineering. Geotext. Geomembr. 2010, 28, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Mandal, J.N. Numerical Analyses on Cellular Mattress-Reinforced Fly Ash Beds Overlying Soft Clay. Int. J. Geomech. 2016, 17, 04016095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A.; Latha, G.M. Evolution of Geocells as Sustainable Support to Transportation Infrastructure. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Zhang, M. Performance of Geocell-Reinforced Embankment under Long-Term Cyclic Loading. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2025, 2679, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedela, R.; Karpurapu, R. Influence of pocket shape on numerical response of geocell reinforced foundation systems. Geosynth. Int. 2021, 28, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, N.K.; Tiwari, S.K. Bearing capacity of square footing on geocell reinforced fly ash beds. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 10570–10580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.W.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, J.B.; Yao, H.L. Study on performance of geocel-reinforced red clay subgrade. Geosynth. Int. 2024, 31, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davarifard, S.; Tafreshi, S.N.M. Plate Load Tests of Multi-Layered Geocell Reinforced Bed considering Embedment Depth of Footing. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2015, 15, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyanthi, S.; Venkatakrishnaiah, R.; Raju, K.V.B. Multilayer geocell-reinforced soils using mayfly optimisation predicts circular foundation load settlement. Int. J. Hydromechatron. 2024, 7, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafreshi, S.N.M.; Shaghaghi, T.; Mehrjardi, G.T.; Dawson, A.R.; Ghadrdan, M. A simplified method for predicting the settlement of circular footings on multi-layered geocell-reinforced non-cohesive soils. Geotext. Geomembr. 2015, 43, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Mandal, J.N. Model Studies on Geocell-Reinforced Fly Ash Bed Overlying Soft Clay. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2015, 28, 04015091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabiri Kouchaksaraei, M.; Bagherzadeh Khalkhali, A. The effect of geocell dimensions and layout on the strength properties of reinforced soil. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, H.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Z. Experimental Investigation of Mechanical Behaviours of Fiber-Reinforced Fly Ash-Soil Mixture. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 1050536. [Google Scholar]

- Kudva, L.P.; Nayak, G.; Shetty, K.K.; Sugandhini, H.K. Mechanical Properties of Fiber-Reinforced High-Volume Fly-Ash-Based Cement Composite—A Long-Term Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneja, G.; Sharma, R. Numerical Investigation of Square Footing Positioned on Geocell Reinforced Sand by Using Abaqus Software. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 2022, 32, 154–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.A.; Dias, D. 3D numerical study of the performance of geosynthetic-reinforced and pile-supported embankments. Soils Found. 2021, 61, 1319–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, S.; Deb, P. Finite Element Analysis of Geogrid-Incorporated Flexible Pavement with Soft Subgrade. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Manna, B.; Shahu, J.T. Experimental investigation of geometry of geocell on the performance of flexible pavement under repeated loading. Geotext. Geomembr. 2024, 52, 654–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naaman, M.F.; Haq, M.; Khan, M.A.; Ali, K.; Kamyab, H. Geotechnical and microstructural analysis of high-volume fly ash stabilized clayey soil and machine learning application. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, M.F.; Keskin, S.N. Experimental Investigation of the Mechanical Properties of Polypropylene Fiber-Reinforced Clay Soil and Development of Predictive Models: Effects of Fiber Length and Fiber Content. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 13593–13611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, T.; Ansari, M.A.; Hussain, A. Soil stabilization by reinforcing natural and synthetic fibers—A state of the art review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqawasmeh, H.M. Enhancing the sustainability of geotechnical engineering with utilization of fly Ash. Discov. Mater. 2025, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IS 2720 (Part 4); Methods of Test for Soils: Grain Size Analysis. Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 1985.

- IS 2720 (Part 14); Methods of Test for Soils: Determination of Density Index of Cohesionless Soils. Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 1983.

- IS 2720 (Part 3/Sec. 1); Methods of Test for Soils: Determination of Specific Gravity. Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 1980.

- IS 4031 (Part 4 & 5); Methods of Physical Tests for Hydraulic Cement. Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 1988.

- IS 2720 (Part 13); Methods of Test for Soils: Direct Shear Test. Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 1986.

- IS 2720 (Part 7); Methods of Test for Soils: Determination of Water Content—Dry Density Relation using Light Compaction. Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 1980.

- IS 1888; Methods Load Test on Soils. Indian Standards Institution: New Delhi, India, 1982.

- Biswas, A.; Krishna, A.M. Geocell-Reinforced Foundation Systems: A Critical Review. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2017, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zong, Z.; Cen, H.; Jiang, P. Analysis of Mechanical Properties of Fiber-Reinforced Soil Cement Based on Kaolin. Materials 2024, 17, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanadham, B.V.S.; Konig, D. Studies on scaling and instrumentation of a geogrid. Geotext. Geomembr. 2004, 22, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evirgen, B.; Kara, H.O.; Ucun, M.S.; Gultekin, A.A.; Tos, M.; Ozturk, V. The effect of the geometrical properties of geocell reinforcements between a two layered road structure under overload conditions. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjei, C.; De Silva, L.I.N. Numerical modelling of the behaviour of model shallow foundations on geocell reinforced sand. In Proceedings of the Moratuwa Engineering Research Conference, Moratuwa, Sri Lanka, 5–6 April 2016; pp. 216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Aydogmus, T.; Alexiew, D.; Klapperich, H. Investigation of Interaction Behaviour of Cement-Stabilized Cohesive soil and PVA Geogrids. In Proceedings of the 3rd European Geosynthetics Conference, Munich, Germany, 1–3 March 2004; pp. 559–564. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.S.; Wang, D.Y.; Cui, Y.J.; Shi, B.; Lin, J. Tensile Strength of Fiber Reinforced Soil. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2016, 28, 04016031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.; Chi, M.; Huang, R. Effect of Fineness and Replacement Ratio of Ground Fly Ash on Properties of Blended Cement Mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 176, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, D.M.; Pinho-Lopes, M.; Lopes, M.L. Effect of Geocell Reinforcement Inclusion on the Strength Parameters and Bearing Ratio of a Fine Soil. Procedia Eng. 2016, 143, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, A.; Sitharam, T.G. 3-Dimensional numerical modelling of geocell reinforced sand beds. Geotext. Geomembr. 2015, 43, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chore, H.S.; Vaidya, M.K. Strength Characterization of Fiber Reinforced Cement–Fly Ash Mixes. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2015, 1, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shooshpasha, I.; Shirvani, R.A. Effect of cement stabilization on geotechnical properties of sandy soil. Geomech. Eng. 2015, 8, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiloglu, H.A.; Kuruchu, K.; Akbas, D. Investigating the Effect of Polypropylene Fiber on Mechanical Features of a Geopolymer-Stabilized Silty Soil. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 28, 628–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniraj, S.R.; Gayathri, V. Geotechnical behaviour of fly ash mixed with randomly oriented fiber inclusions. Geotext. Geomembr. 2003, 21, 123–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiyaput, S.; Arwaedo, N.; Kingnoi, N.; Nghia-Nguyen, T.; Ayawanna, J. Effect of curing conditions on the strength of soil cement. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e01082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.