Study on Construction Mechanical Characteristics and Offset Optimization of Double Side Drift Method for Large-Span Tunnels in Argillaceous Soft Rock

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Project Background

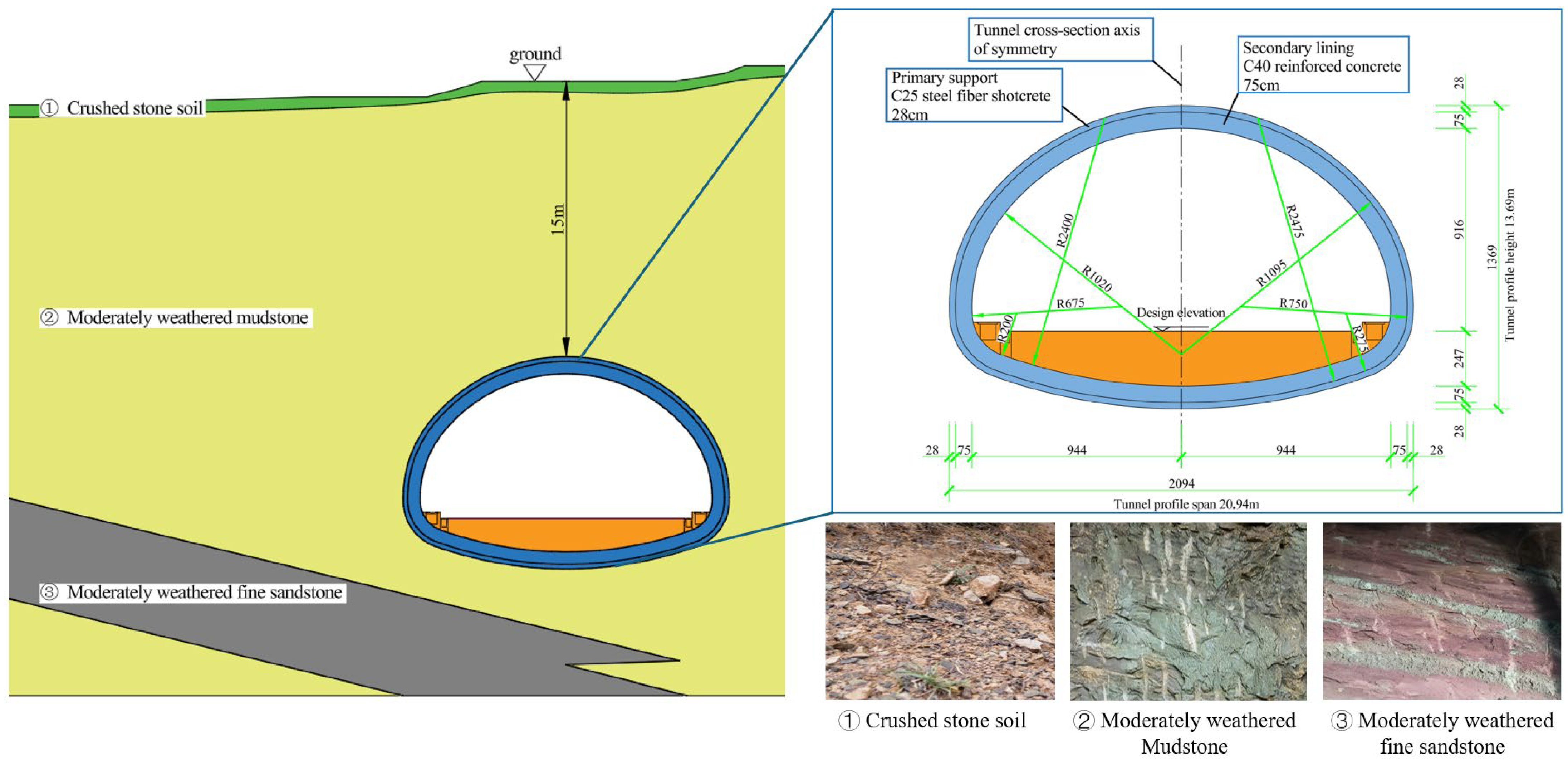

2.1. Project Overview

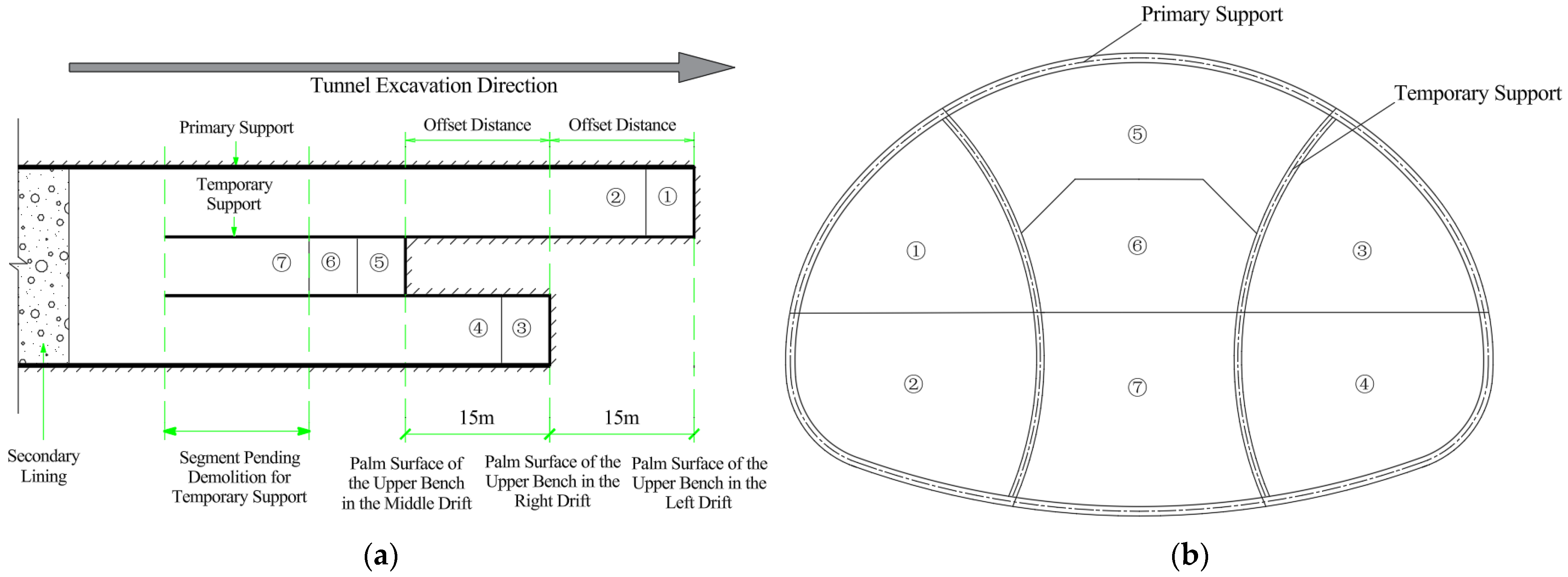

2.2. Construction Method and Sequence for Large-Span Tunnel in Argillaceous Soft Rock

2.2.1. Construction Parameters of Each Structure

2.2.2. Tunnel Construction Methods and Sequences

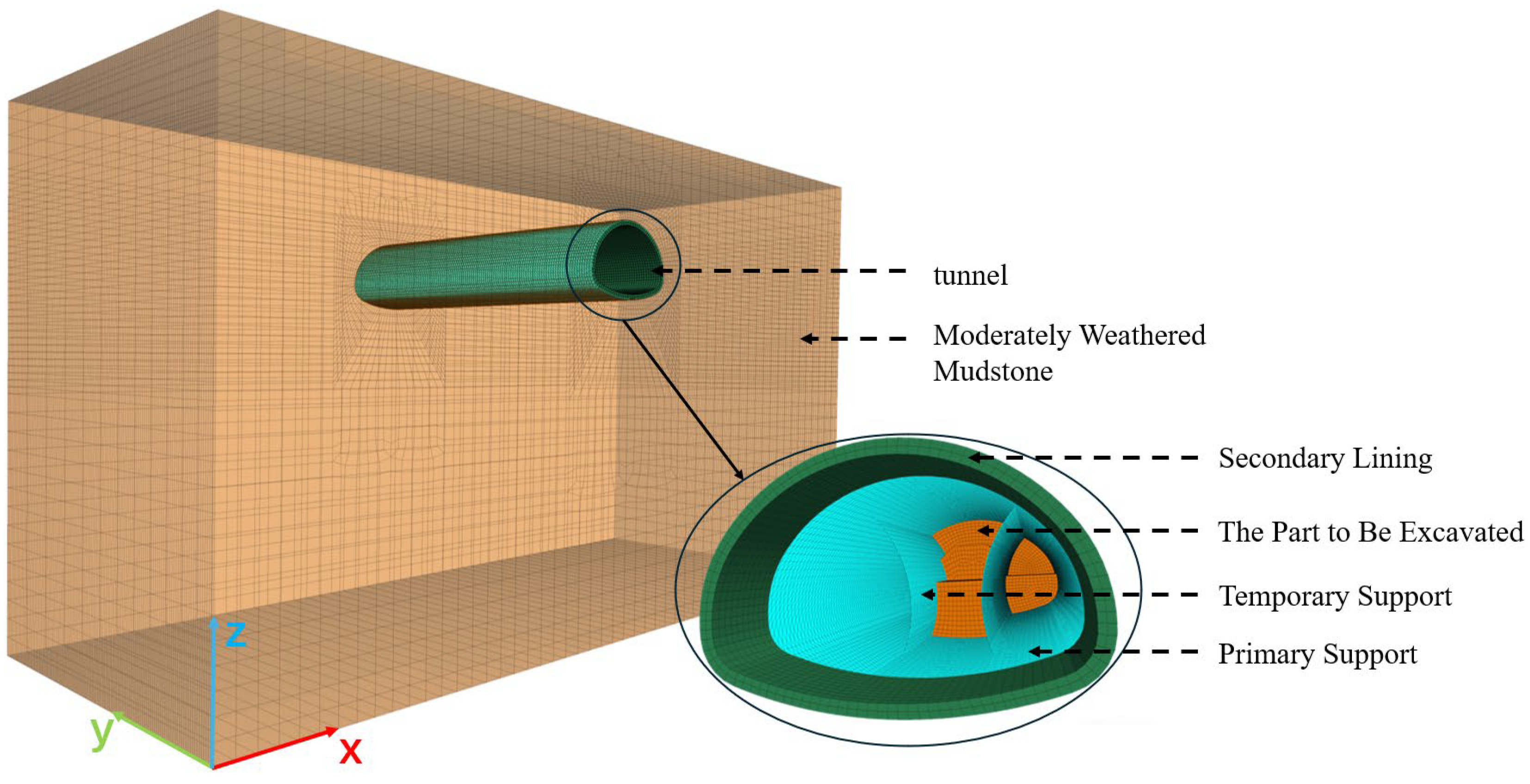

3. Numerical Model

3.1. Establishment of the Numerical Model

3.2. Model Assumptions and Parameter Settings

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Mechanical Characteristics of DSDM Construction for Large-Span Tunnels in Argillaceous Soft Rock

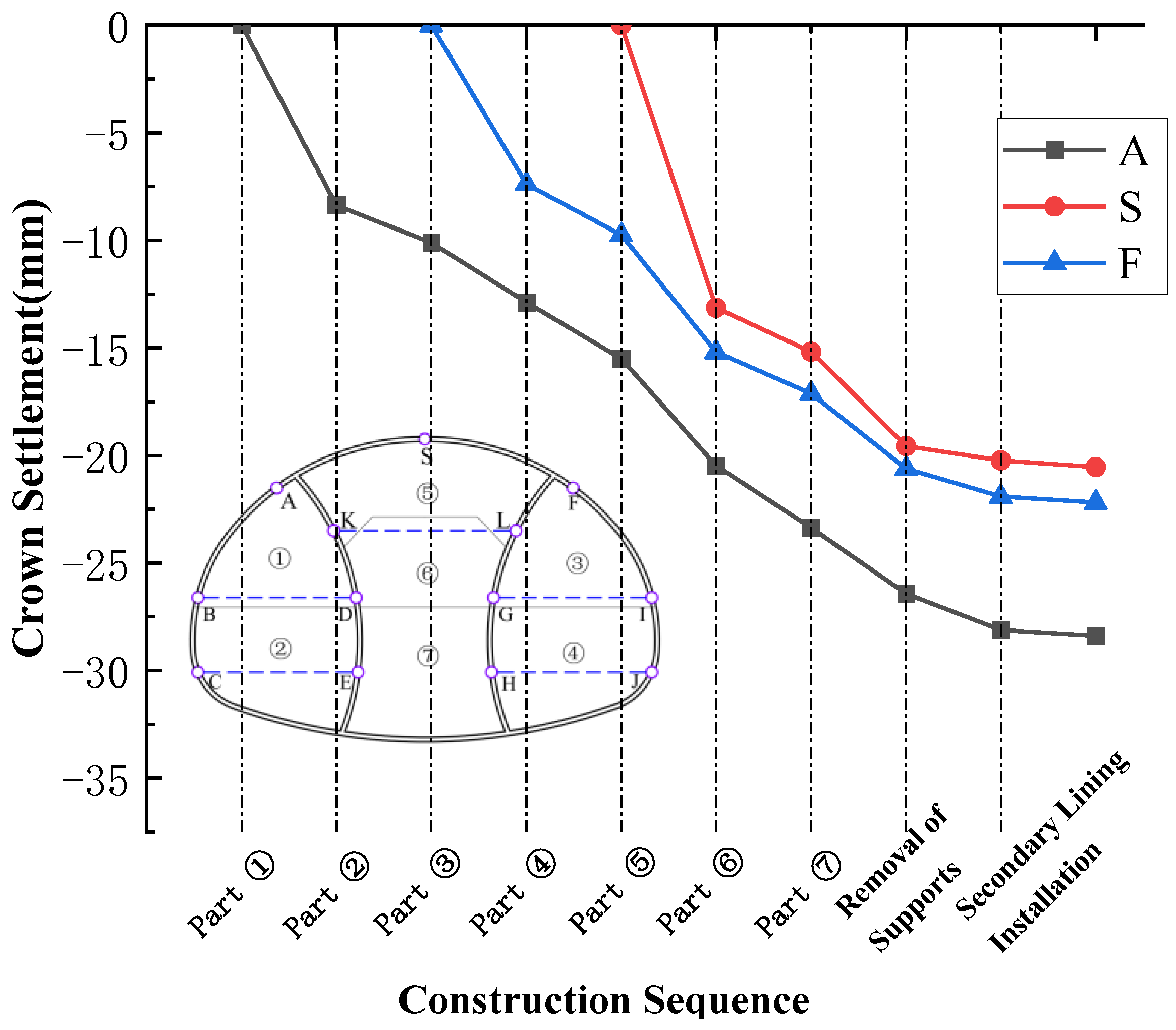

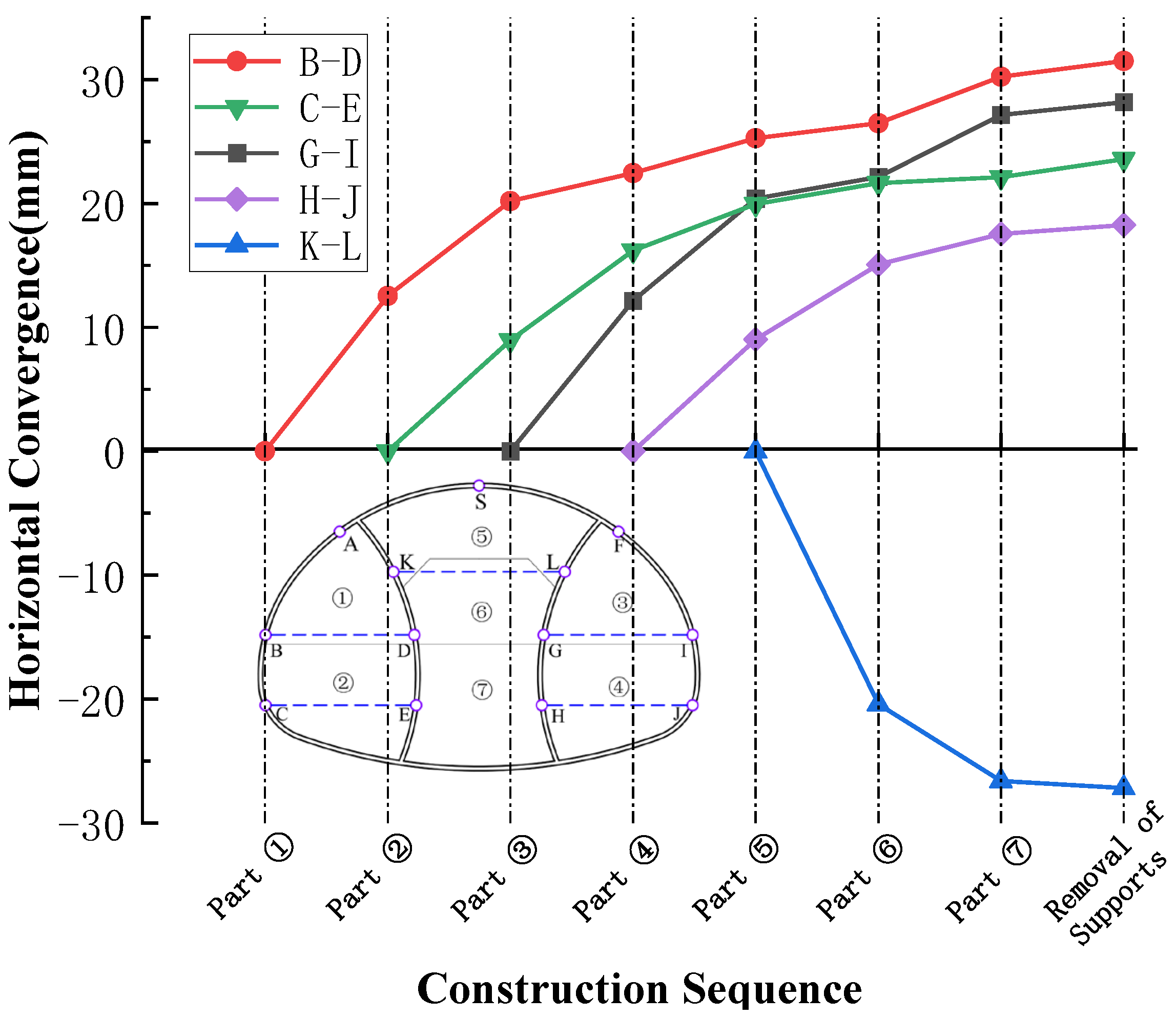

4.1.1. Analysis of Primary Support Deformation

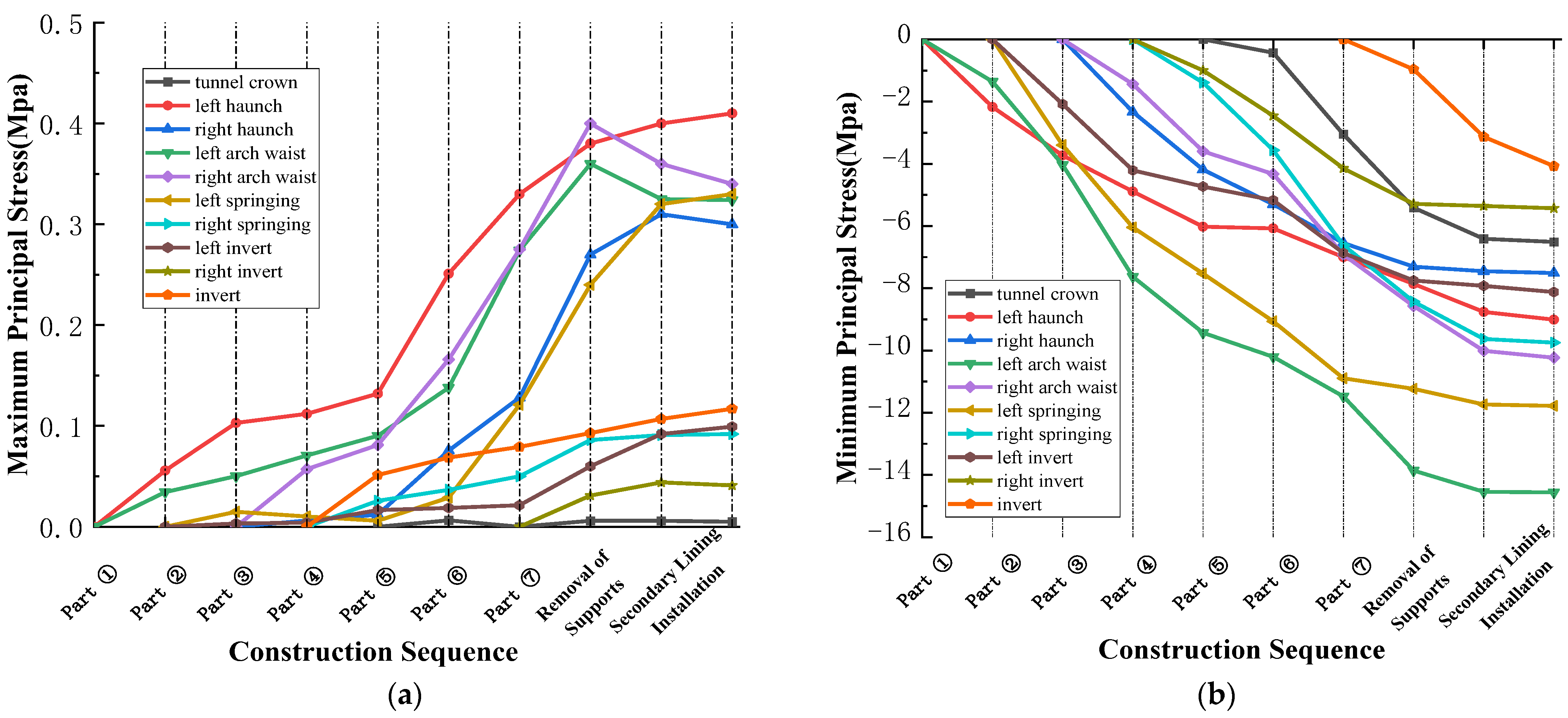

4.1.2. Analysis of Primary Support Force

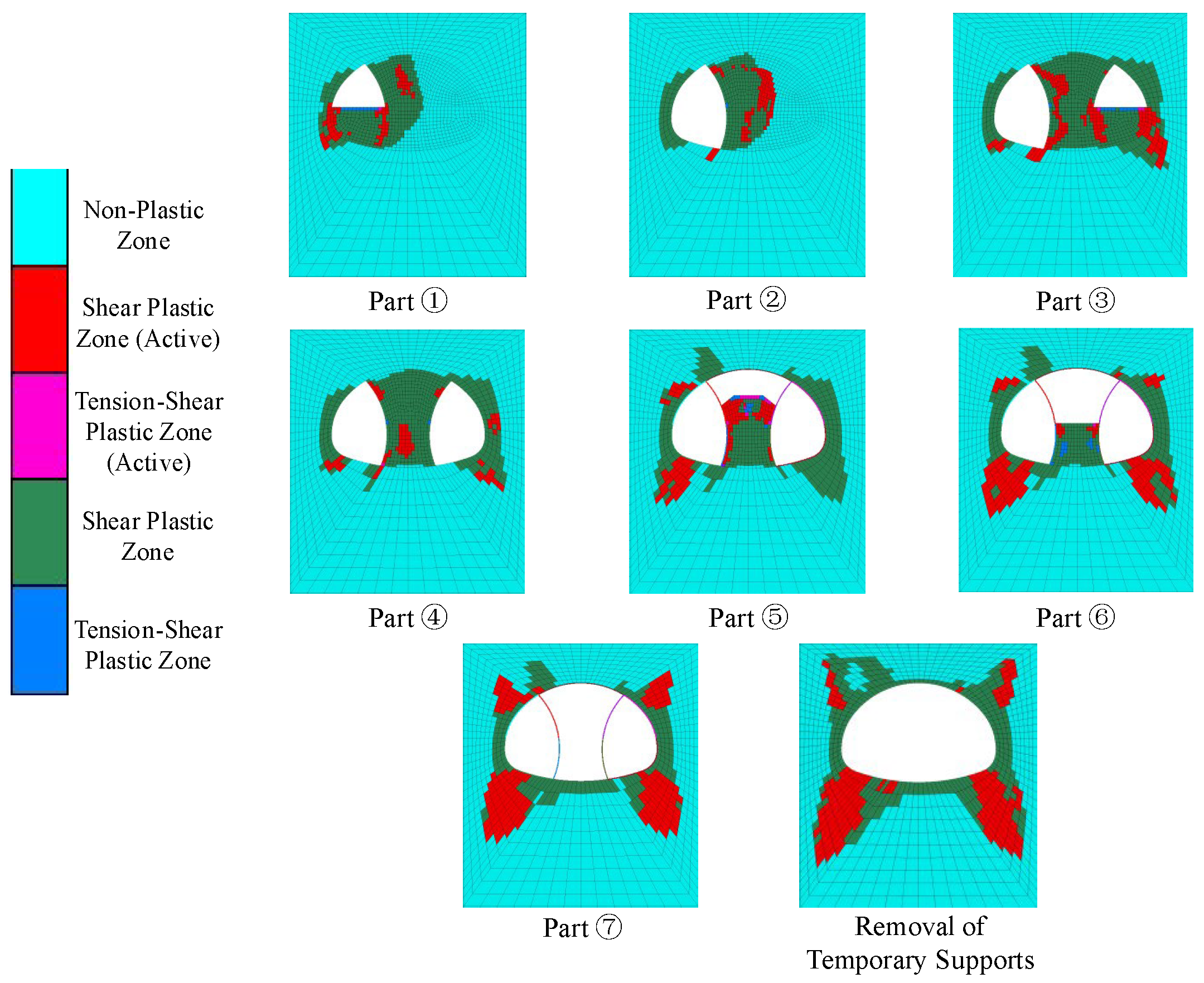

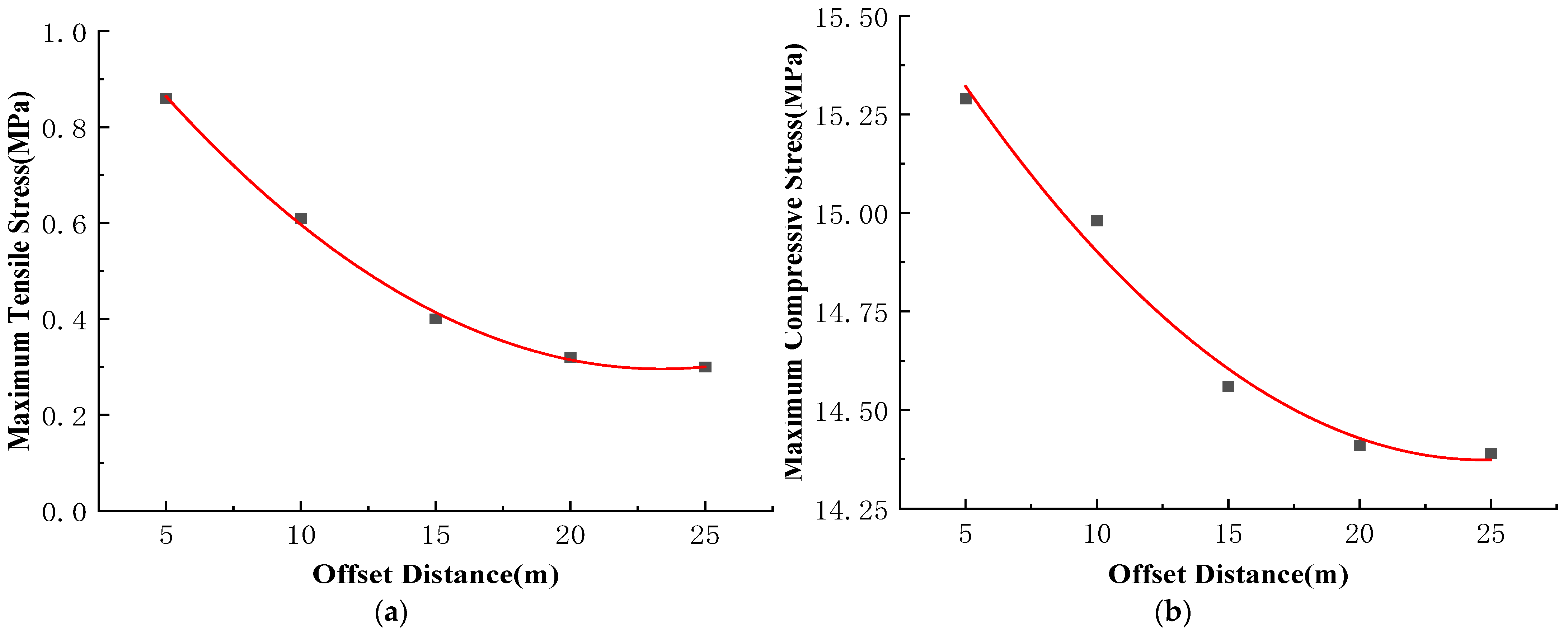

4.1.3. Development Law of Plastic Zone

4.2. Influence of Face Offset Between Drifts on DSDM Excavation

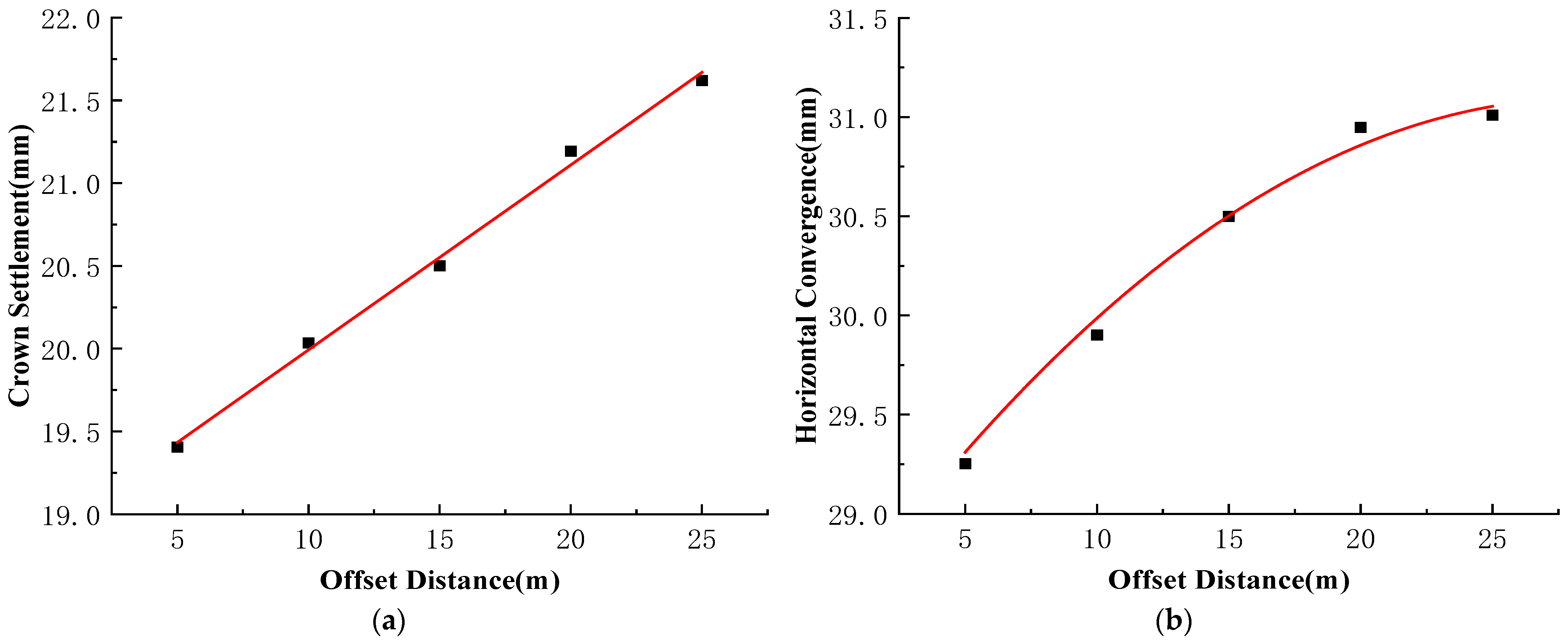

4.2.1. Deformation Analysis of the Primary Support

4.2.2. Stress Analysis of the Primary Support

4.2.3. Development of Plastic Zone

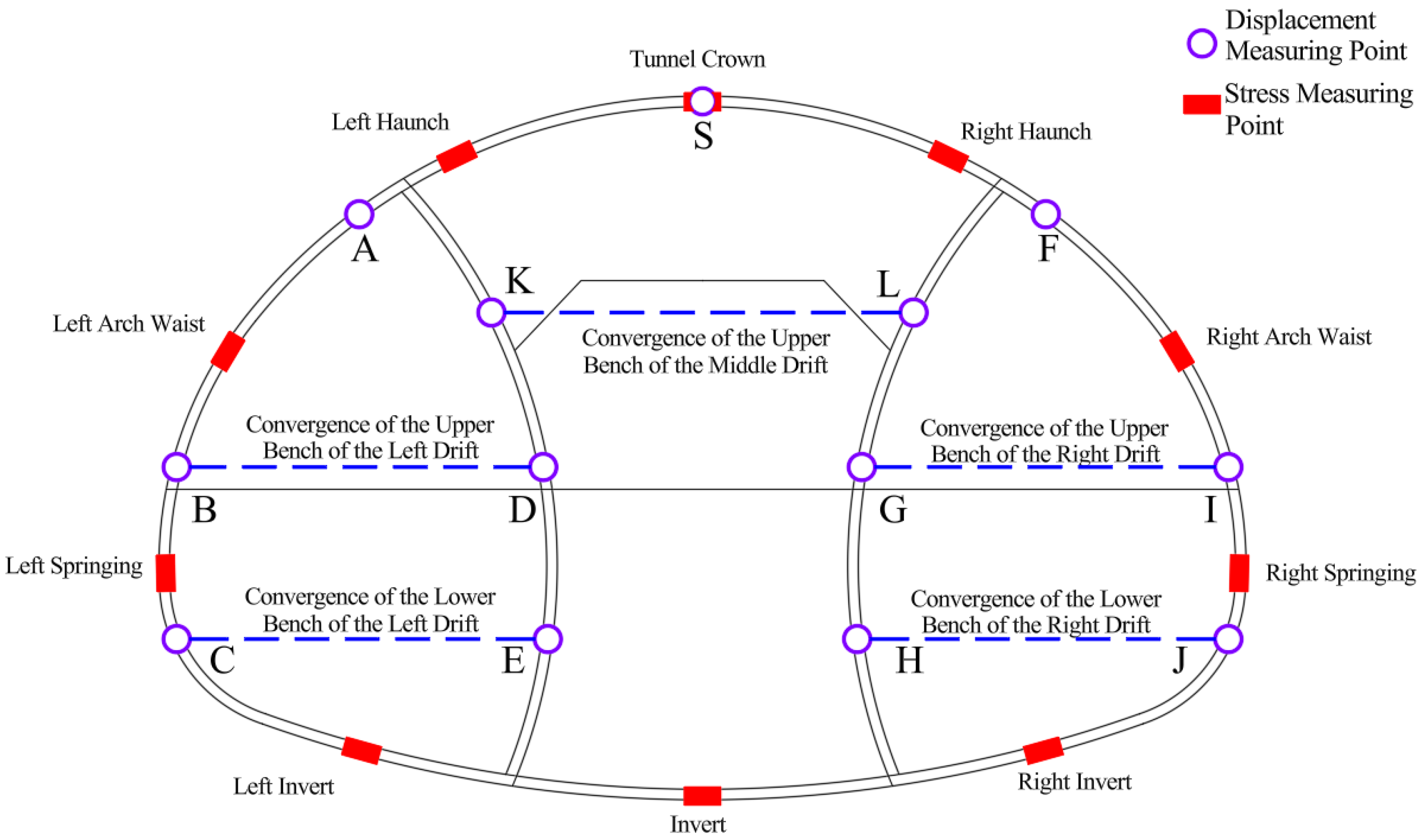

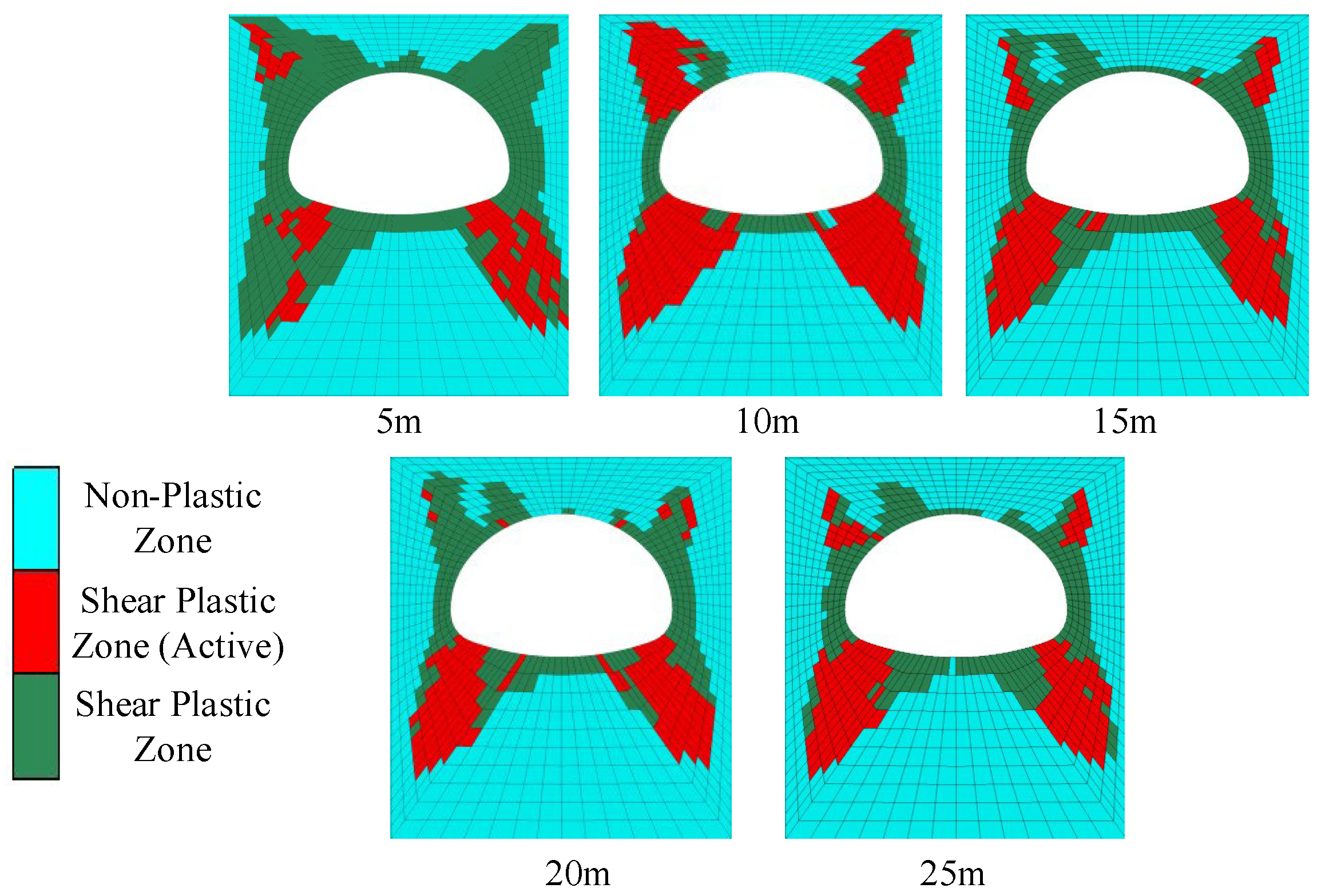

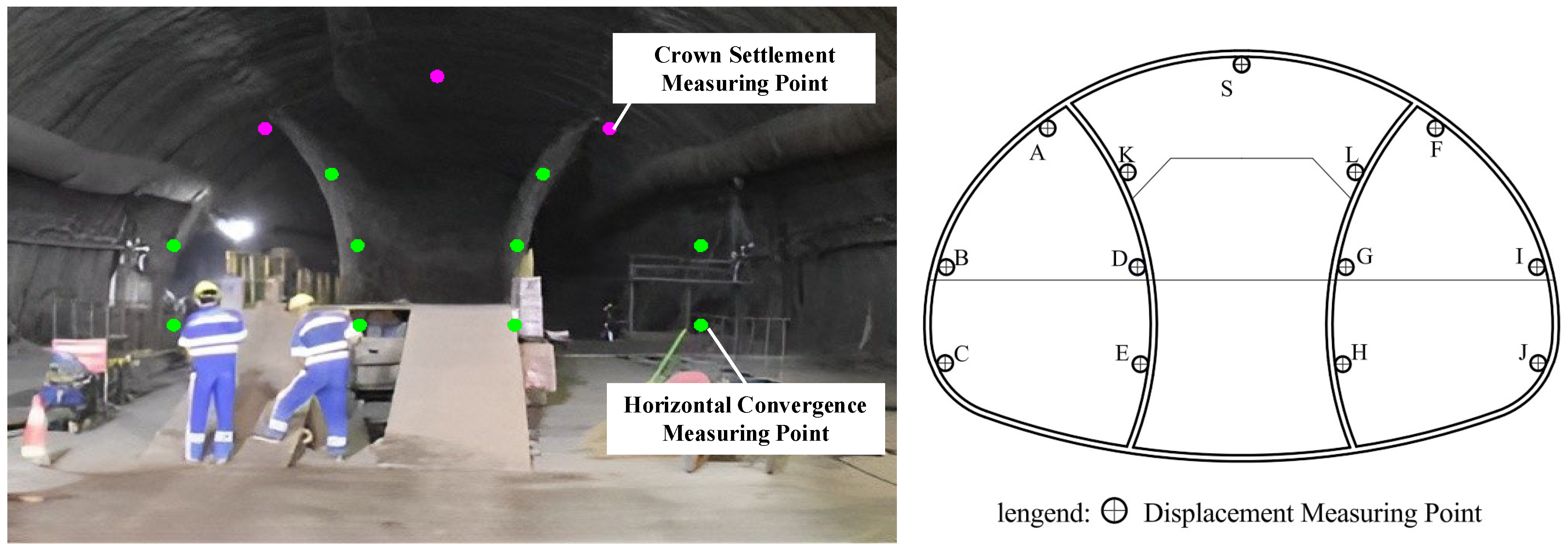

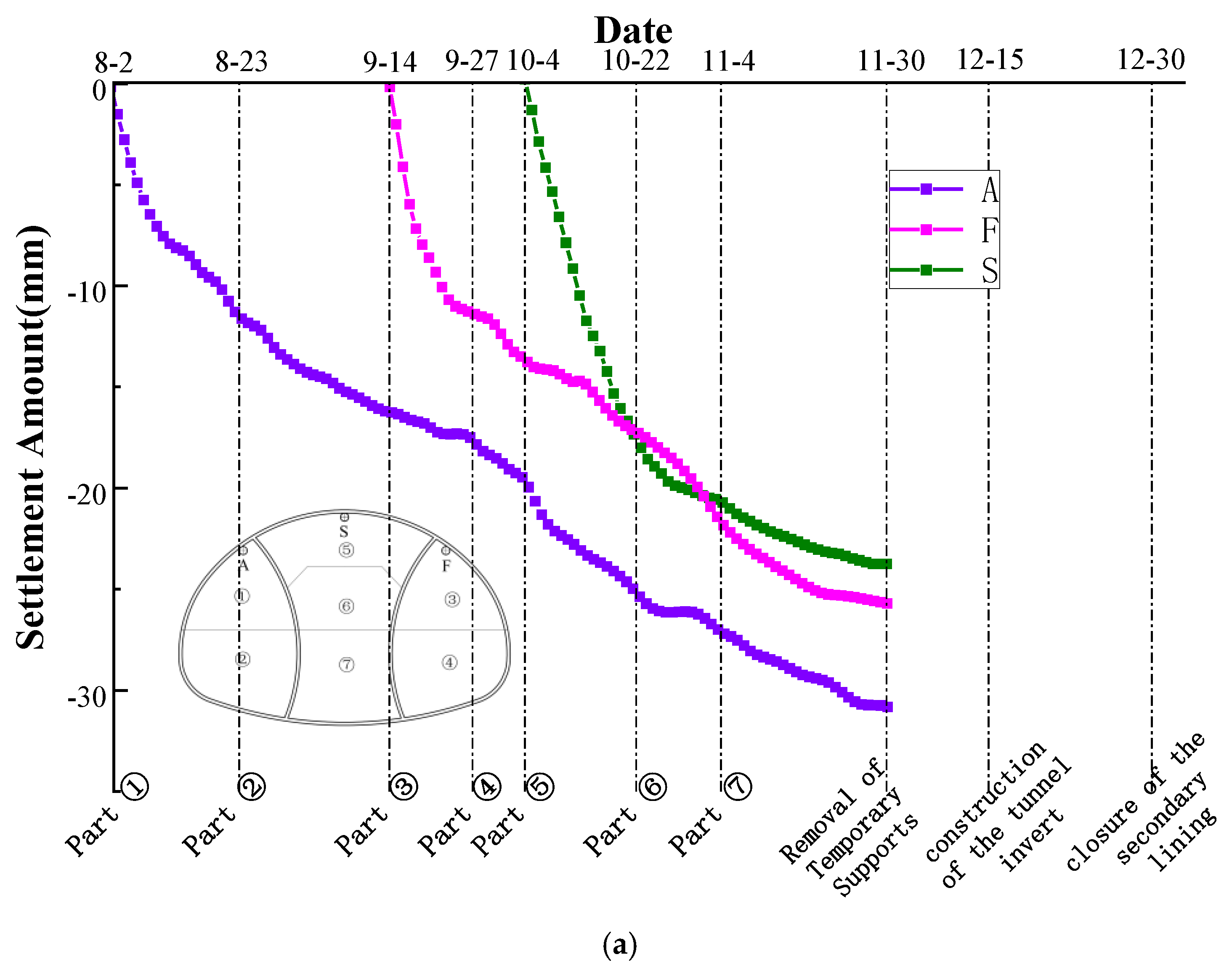

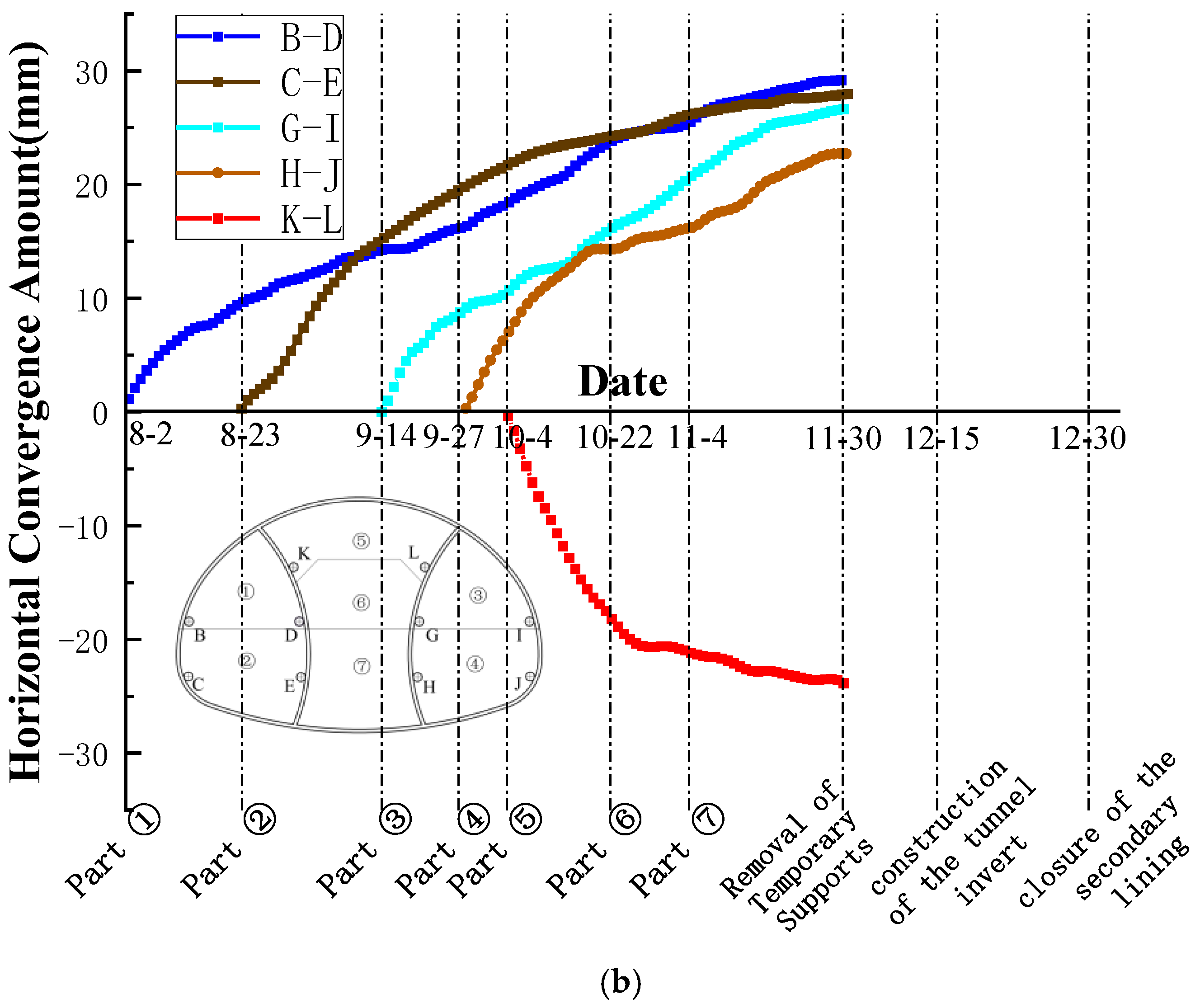

5. Analysis of On-Site Monitoring and Measurement

5.1. Monitoring Plan/Monitoring Scheme

5.2. Data Analysis of Primary Support Deformation Monitoring

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Deformation behavior of the primary support: During DSDM construction, crown settlements of the primary support increase rapidly after excavation of the upper benches and then gradually stabilize. The left drift exhibits the largest settlement, while the central drift shows the smallest. Horizontal convergence follows a similar trend, with the left and right drifts converging inward and the central drift expanding outward. Upper bench excavation induces slightly larger convergence than lower benches, with the left drift upper bench showing the maximum inward convergence.

- (2)

- Stress evolution of the primary support and development of the plastic zone in the surrounding rock: Primary support stresses increase sharply after excavation of each segment and then tend to stabilize. The maximum tensile stress occurs at the left haunch (0.41 MPa), and the maximum compressive stress at the left arch waist (14.56 MPa). After overall excavation, the left side experiences significantly higher stress, resulting in an eccentric stress state. The surrounding rock plastic zones exhibit a butterfly-shaped distribution, concentrated mainly at the haunches and arch springings.

- (3)

- As the drift face offset distance decreases, primary support deformation reduces, while both stress and plastic zone area increase. When the offset distance is less than 15 m, these increases become pronounced, indicating that the drift face offset distance should not be less than 15 m in practice.

- (4)

- Field monitoring confirms that upper bench excavation of each drift has the most significant impact on crown settlement and horizontal convergence. Subsequent excavation induces slow growth in deformation, which eventually stabilizes. The maximum cumulative crown settlement and horizontal convergence at the monitored section are 30.2 mm and 35.6 mm, respectively, both below the reserved deformation allowance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, M.N.; Guan, B.S.; He, C. Study on mechanical behaviour of three-lane road tunnel under tectonic stresses. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 1998, 20, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, B.X.; Cheng, C.G. Review on the Research Status of Three-Lane Large-Section Highway Tunnels. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2002, 22, 360–366, 373. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T. Analysis of mechanical response of four-lane small clear spacing highway tunnel with super-large cross-section. China Civ. Eng. J. 2015, 48 (Suppl. 1), 302–305. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, J.; Shi, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, W. Mechanical Characteristics of Primary Support of Large Span Loess Highway Tunnel: A Case Study in Shaanxi Province, Loess Plateau, NW China Primary. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 104, 103532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Shi, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, H. Study of Deformation Behaviors and Mechanical Properties of Central Diaphragm in a Large-Span Loess Tunnel by the Upper Bench CD Method. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8887040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhao, J.; Tan, Z.; Zhou, X. Mechanical Responses in the Construction Process of Super-Large Cross-Section Tunnel: A Case Study of Gongbei Tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 115, 104044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.B.; Yang, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.W. Spatio-temporal Effect of Long-span Loess Tunnel Surrounding Rock Deformation. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. 2024, 41, 190–197. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y.F.; Shi, C.H. Study on deformation control technology of shallow and large cross-section tunnel beneath expressway in soft rock. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2018, 15, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Tan, Z.S.; Yu, Y.; Ni, L.S. Research on construction procedure for shallow large-span tunnel undercrossing highway. Rock Soil Mech. 2011, 32, 2803–2809. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, C.; Chen, J.; Luo, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Gao, B.; Li, J. Ground Movement Induced by Tunnelling in Shallow Loess Strata. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2026, 168, 107156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; He, H.; Li, P. Key Techniques for the Construction of High-Speed Railway Large-Section Loess Tunnels. Engineering 2018, 4, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Dai, J.; Wang, B.; Mo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tian, C. Structural Analysis of Large-Span Tunnel Excavated by Upper Bench Center Diaphragm Method: An Analytical Model and Its Application. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2026, 167, 107053. [Google Scholar]

- An, Z.; Ma, W.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, Z. Stability Analysis of Extra-Large-Span Tunnels During Construction: A Case Study. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2024, 42, 3107–3121.3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, J.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, L. Performance of Super-Large-Span Tunnel Portal Excavated by Upper Bench CD Method Based on Field Monitoring and Numerical Modeling. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8824618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shang, C.; Chu, K.; Zhou, Z.; Song, S.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y. Large-Scale Geo-Mechanical Model Tests for Stability Assessment of Super-Large Cross-Section Tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 109, 103756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; He, S.; Liu, X.; Ma, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, B. Investigating the Mechanical Responses and Construction Optimization for Shallow Super-Large Span Tunnels in Weathered Tuff Stratum Based on Field Monitoring and Flac3D Modeling. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 22, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.; Zhou, H.; Qiao, C.; Gao, Y. Excavation and Kinematic Analysis of a Shallow Large-Span Tunnel in an up-Soft/Low-Hard Rock Stratum. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 97, 103245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Cao, L.; Ma, Y.; Fang, S.; Wang, K. Research on construction behaviors of support system in four-lane ultra large-span tunnel with super-large cross-section. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2010, 29, 140–148. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Zhou, X. Construction mechanics of tunnel with super-large cross-section and its dynamic stability. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. 2015, 49, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Li, S.C.; Zhou, Z.Q.; Li, L.P.; Wang, K.; Hou, F.J.; Qin, C.S.; Gao, C.L. Model test on mechanical characteristics of surrounding rock during construction process of super-large section tunnel in complex strata. Rock Soil Mech. 2018, 39, 3495–3504. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.D.; Liu, J.; Duan, Y.F.; Xie, H.W. Excavation Scheme of the Large-span Flat and Super-large Section Tunnel of Lianhuo High-speed Xinghua Village No. 1. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2023, 23, 12258–12264. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, J.Q.; Yang, Y.F.; Gao, H.C.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Wang, F. Study on Construction Method Optimization and Mechanical Characteristics of Super-large Section Soft Rock Tunnel. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2023, 19 (Suppl. 2), 819–827. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F.; Tao, J.Q.; Gao, H.C.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Pan, Y.D.; Wang, F. Analysis of Construction Mechanical Characteristics and Construction Method Adaptability of Shallow Super-large Section Tunnel in Argillaceous Soft Rock. Highway 2022, 67, 388–396. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Q.; Hu, B.; Liu, L.; Cheng, Y.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Nie, M.; Zhang, T.; Guo, W.; Cheng, L. Comparative Analysis of Creep Mechanical Characteristics of Yellow Mudstone Tunnel in Natural and Saturated Conditions: Insights from Experiments and Numerical Modeling. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 182, 110121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.L. Construction Parameters Optimization for Double-sidewalls Guiding-hole Method of Shallow Buried Urban Subway Tunnel in Loess Formation. Railw. Eng. 2022, 62, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.B. Construction Parameter Optimization of Both Side Heading Method for Super Shallow embedded Tunnel with Large Cross-section Fujian. Fujian Constr. Sci. Technol. 2012, 6, 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Tao, J.Q.; Gao, H.C. Research on Construction Parameters of Half-Step CD Method with Side Wall Slotting for Large-Span Soft Rock Tunnels. Hailw. Stand. Des. 2025, 69, 133–141. [Google Scholar]

- JTG 3370.1; Specifications for Design of Highway Tunnels Section 1 Civil Engineering. Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Deshpande, S.; Hedaoo, N. Evaluation of Face Stability for Mega Tunnel Under Varying Ground Strength Parameters. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2024, 20, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; Zhou, B.; Jiang, D. Mechanical Response and Stability Optimization of Shallow-Buried Tunnel Excavation Method Conversion Process Based on Numerical Investigation. Buildings 2024, 14, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Zhao, C.; Jia, C.; Shi, C. Study on the Geological Adaptability of the Arch Cover Method for Shallow-Buried Large-Span Metro Stations. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 132, 104897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.Z.; Dai, F.C.; Wei, Y.Q.; Min, H.; Xu, C.; Tu, X.B.; Wang, M.L. Cracking Mechanism of Secondary Lining for a Shallow and Asymmetrically-Loaded Tunnel in Loose Deposits. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2014, 43, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Structure | Material | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| primary support | steel arch frame | HW200 × 200 steel frame, with a spacing of 50 cm between each frame |

| shotcrete | Strength grade C25, thickness 0.28 m | |

| temporary support | steel arch frame | I20b I-steel, with a spacing of 50 cm |

| shotcrete | Strength Grade C25, Thickness 22 cm | |

| secondary lining | reinforced concrete | Strength Grade C40, Thickness 75 cm |

| Construction Steps | Construction Operations * |

|---|---|

| 1 | Excavate Part ①, and construct the primary support and temporary support for the upper bench of the left drift |

| 2 | Excavate Part ②, and construct the primary support and temporary support for the lower bench of the left drift |

| 3 | Excavate Part ③, and construct the primary support and temporary support for the upper bench of the right drift |

| 4 | Excavate Part ④, and construct the primary support and temporary support for the lower bench of the right drift |

| 5 | Excavate Part ⑤, and construct the primary support |

| 6 | Excavate Part ⑥ |

| 7 | Excavate Part ⑦, and enclose the primary support to form a ring |

| 8 | Remove the Temporary Support |

| 9 | Construct the Tunnel Secondary Lining |

| Material Type | Density /(kg m−3) | Elastic Modulus /GPa | Poisson’s Ratio | Cohesion /MPa | Internal Friction Angle /° | Thickness /m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderately Weathered Mudstone | 2300 | 1.1 | 0.34 | 0.2 | 23 | / |

| Secondary Lining | 2400 | 34.2 | 0.2 | / | / | 0.75 |

| Primary Support | 2300 | 32 | 0.2 | / | / | 0.28 |

| Temporary Support | 2300 | 30 | 0.2 | / | / | 0.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

He, W.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F. Study on Construction Mechanical Characteristics and Offset Optimization of Double Side Drift Method for Large-Span Tunnels in Argillaceous Soft Rock. Buildings 2026, 16, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010023

He W, Wang T, Zhang Y, Wang F. Study on Construction Mechanical Characteristics and Offset Optimization of Double Side Drift Method for Large-Span Tunnels in Argillaceous Soft Rock. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Wei, Tengyu Wang, Yangyu Zhang, and Feng Wang. 2026. "Study on Construction Mechanical Characteristics and Offset Optimization of Double Side Drift Method for Large-Span Tunnels in Argillaceous Soft Rock" Buildings 16, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010023

APA StyleHe, W., Wang, T., Zhang, Y., & Wang, F. (2026). Study on Construction Mechanical Characteristics and Offset Optimization of Double Side Drift Method for Large-Span Tunnels in Argillaceous Soft Rock. Buildings, 16(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010023