Abstract

Structural deterioration inevitably leads to defects in buildings. It is primarily caused by environmental exposure, material ageing, and long-term service conditions, whereas defects such as poor soil compaction arise from improper construction practices rather than deterioration mechanisms. Major concrete defects include missing portions such as cracking, corrosion, dents, blemishes, and spalling. Failure to identify minor issues can lead to serious problems, which become more expensive and difficult to repair, as well as poorer overall building performance. Traditional structural assessment methods, such as visual inspections and non-destructive testing are typically used for periodic condition evaluation, whereas SHM involves continuous or long-term monitoring using sensor-based systems. However, such approaches can be manual, costly, dangerous, and biased. In order to overcome these limitations, contemporary SHM systems combine traditional approaches with building information modelling (BIM) and artificial intelligence (AI). Different AI algorithms are used, including SVM, random forest, regression, and KNN for machine learning and decision trees; random forest, K-means clustering, CNN, U-Net, ResNet, FCN, VGG16, and DeepLabv3+ for deep learning. This review will survey both the traditional and novel approaches in the field of SHM and the recent advancements.

1. Introduction

Structural failures are an ongoing issue in India, and 13,000 people have died over 5 years owing to infrastructure collapses. These incidents emphasize serious problems in the quality of building, maintenance, and regulatory scrutiny. Structural performance may be greatly affected due to the presence of defects or faults that cause potential damage to the structure. Nonetheless, it is an inevitable fact that buildings will experience wear and tear over time, and these flaws are unavoidable. It is critical to comprehend the various faults that can affect a building’s general condition [1]. Structural defects are major or minor types. Major defects typically affect the superstructure and substructure, leading to total structural failure. Minor defects are predominantly aesthetic and do not constitute a structural breach of any kind.

Several aspects contribute to the formation of these defects in the structural elements, leading to its failure or deterioration over a period of time. Construction materials can decay over time as a result of exposure to moisture, chemicals, fire [2], and UV radiation. Freeze–thaw cycles, reinforcement bar corrosion [3], alkali–silica interactions, and sulfate assault also induce cracking and spalling in concrete. Additionally, metals can corrode, losing their strength and integrity over time. Environmental influences, poor construction methods, or design defects can all lead to structural issues. Lack of analysis, wrong materials, or construction can compromise structures, leaving them open to moisture, temperature changes, and biological growth. Defects are exacerbated by natural disasters and overloading; the structure in time will be gradually cracking, deforming, or collapsing. Fatigue from repeated loading and unloading can cause the initiation of micro-cracks and may result in its spread and expansion, leading to the eventual failure of the structures [4]. Further, structures can deteriorate more quickly and have pre-existing flaws exacerbated by inadequate or postponed maintenance [5]. Ignoring minor problems can lead to their criticality over time, resulting in higher repair costs or even structural collapses.

The buildings may be subjected to age and chemical reactions, all of which would lower their structural performance and serviceability [6,7]. Frequent building condition assessments can prevent early building degradation [8]. To restore the health of structures, improve service life, and eventually raise the standard of public safety, it is imperative to comprehend structural issues in a timely manner [9,10]. Assessing safety using visual inspection techniques is a crucial step in preserving the structure’s integrity and identifying any irregularities, signs of deterioration, or potential harm. Traditionally, visual inspection methods are used to either directly or indirectly examine the buildings. Portable instruments, such as mirrors, flashlights, magnifying glasses, cameras, drones, and binoculars, may be used as aids in visual inspection to get into hard-to-reach places and take in-depth pictures. It assists in locating possible problems that could jeopardize the durability, functionality, or safety of the structure. However, even for skilled inspectors, visual examination could be a laborious, costly, risky, and subjective process [11,12].

Visual inspections require the presence of trained inspectors who can quickly evaluate the infrastructure’s condition based on preset standards. This traditional approach is frequently expensive, time-consuming, and exacting. In addition, it may jeopardize the safety of experts, especially in circumstances where accessibility is limited [13,14]. Further, visual inspection also hinders real-time tracking of changes. Civil engineers created structural health monitoring (SHM) systems to address this issue, and they are gaining popularity in the field [15,16]. It focuses on the continuous or intermittent monitoring of the structural condition of engineering structures, such as buildings, bridges, dams, pipelines, etc. By continuously or sporadically assessing the condition of structures, SHM helps to ensure their safety. It makes it possible to identify damage, degradation, or structural irregularities early on, which could compromise the integrity of the building and put residents and the public in danger. SHM enables proactive maintenance methods by delivering real-time or near real-time data on structural conditions [17,18]. Early detection of problems enables prompt repairs or interventions, preventing small concerns from worsening into catastrophic structural failures, lowering the danger of costly repairs or replacements. SHM provides useful information about the performance and behavior of structures over time. However, anomalous data can greatly impact the evaluation of engineering structures’ performance. To prevent misjudging structural performance in SHM, anomalous data from measurements must be identified and eliminated [19]. For effective observation, SHM employs various sensing and inspection techniques based on physical principles, including vibration monitoring [20], radiography [21], eddy current testing [22], acoustic and ultrasonic emission-based monitoring [23,24], sensor-based monitoring, non-destructive testing [25,26], visual inspection, and remote sensing. AI and BIM-based methods are not physical monitoring techniques but serve as data-driven and integrative frameworks that enhance the interpretation, management, and utilization of information obtained from these sensing approaches [27,28]. Permanent sensors are installed on the structures of SHM systems to allow for numerous, regular measurements while the system is in operation [29,30,31,32]. Analyzing and comparing monitored data allows for timely detection of aberrant structural situations, initiating warnings and maintenance recommendations effectively [33,34,35,36,37,38].

Hamdan et al. [39], in their studies about various SHM techniques, affirm the fact that SHM is ideal for several applications due to its increased ability to monitor structural damages, improving the reliability and life cycle of structures. Del Grosso [40] identified economic degradation of materials and the availability of low cost sensing technologies as key drivers for SHM adoption. Similar concerns regarding reliability, uncertainty, and false alarm reduction in SHM systems have also been widely reported in the literature. For instance, Kamali et al. [41] investigated statistical pattern recognition and novelty detection approaches to mitigate false alarms caused by environmental and operational variability. More recent studies have further emphasized robust damage detection strategies, uncertainty quantification, and data normalization techniques to enhance SHM reliability under real world conditions.

Previous reviews on SHM have only explored traditional approaches, including visual inspections and some NDT methods. They highlighted the effectiveness in the detection of structural anomalies and further emphasized these techniques’ limits, including labor intensiveness and subjectivity; their accuracy for real-time monitoring is also severely restricted. The latest research in SHM has concentrated on the integration of AI, BIM, and machine learning algorithms to address these challenges. Such integration is supposed to improve data analytics, predictive maintenance, and real-time tracking. This review paper, therefore, relies on the works that have been previously reported and makes a comprehensive comparison of both conventional and advanced SHM approaches. It systematically assesses emerging AI-driven and BIM-integrated techniques to ascertain their effectiveness while analyzing their potential to enhance structural safety, reliability, and defect detection efficiency.

Studies from the earlier literature indicate that current methods involving UAVs and robotics are useful only for surface defects but fail to address the internal structural problems or anomalies attributed to environmental changes. Moreover, the subjectivity and scalability issues associated with documenting results prompt the consideration of hybrid advanced approaches that combine AI-based tools to monitor structural health holistically and with high reliability. While NDT methods like acoustic emission, infrared thermography, and ultrasonic testing have shown considerable utility for surface and internal defects in structures, there is still a limited attempt to merge the techniques with AI and machine learning algorithms to increase the real-time defect detection capability along with predictive analytics. There is also inadequate work on scalability with respect to widespread applications like infrastructure at a larger scale or even historical structures exposed to more complex environmental conditions.

A clear research gap is evident in the state-of-the-art exploration of seamless connections between BIM and other cutting-edge technologies, such as the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence, and machine learning for structural health monitoring. Furthermore, the studies are limited to visual and non-invasive inspections while neglecting the more profound structural analysis as well as optimizing real-time data collating from various sources. Future research should develop more BIM integration capabilities that enable holistic structural diagnosis and frameworks that enable the handling of multi-source volumetric and complex datasets to address the gaps identified. This would improve the accuracy of prediction and help in managing lifecycles in different types of structures.

Although techniques driven by AI have automated defect detection and enhanced real-time monitoring in SHM, there are several limitations. First of all, existing methods are highly dependent on poorly representative datasets, which negatively affects the training of both machine and deep learning algorithms in practice. While approaches such as CNNs, U-Net, and ResNet have demonstrated certain capabilities, there are still issues with the incorporation of these tools with traditional forms of SHM approaches, such as non-destructive testing, to provide a complete evaluation. The scalability of AI models needs to be assessed alongside real-time data fusion and the processing of noise and data outliers. The development of BIM and AI-based models that can ensure integration on various platforms is yet another issue that requires deep understanding and development, as such models have the potential for improving predictive maintenance. In this study structural health monitoring (SHM) refers to the systematic and continuous or periodic acquisition, processing and interpretation of data from sensing systems installed on civil structures for the purpose of damage detection, condition assessment, and performance evaluation. The term structural health monitoring is not used as an independent concept in this work, and all references are aligned with the established definition of SHM.

2. Materials and Methods

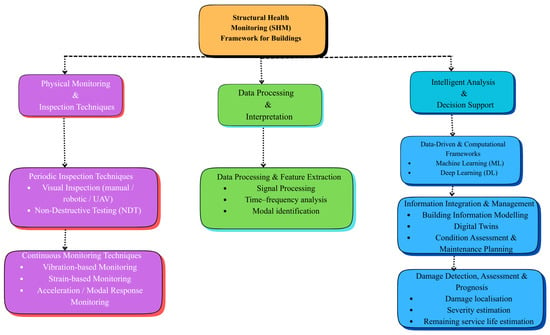

SHM (structural health monitoring) encompasses various modes of detecting the flaw in engineering structures like buildings, dams, and bridges. It primarily aims to detect, localize, and assess damage in structures and to evaluate their performance deterioration over time. A fundamental outcome of SHM is the estimation of the remaining service life or residual capacity of the structure based on measured responses. While SHM supports maintenance decision making, it is not itself a maintenance strategy; rather, it serves as an essential diagnostic component within broader lifecycle management and maintenance frameworks. The review encompasses both traditional and advanced techniques employed in the field of SHM and more recent developments. Divided into sections that analyze the state of current defect detection methods, it discusses the benefits of new technologies and considers possible future trends. It offers a compelling synopsis of modern approaches to defect detection and prognosis. The overall flowchart depicting the approaches reviewed in this paper is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of structural health monitoring approaches and methodologies.

Literature Survey Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted to identify relevant studies on conventional SHM techniques, NDT methods, AI-based damage detection, and advanced monitoring technologies. The databases consulted included Scopus, Web of Science, IEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar. The primary keywords used in various Boolean combinations were as follows: “structural health monitoring”, “SHM”, “non-destructive testing”, “NDT”, “crack detection”, “infrared thermography”, “acoustic emission”, “ultrasonic testing”,” vibration based monitoring”, “computer vision”, “deep learning”, “UAV inspection”, and “BIM-based SHM”.

The search encompassed publications from 2010 to 2024, covering journal articles, conference proceedings, and review papers. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) studies focused on SHM of civil structures; (ii) methods providing quantifiable or interpretable structural assessment; and (iii) papers reporting experimental, numerical, or real-world applications. Exclusion criteria included the following: (i) studies not related to structural monitoring; (ii) purely theoretical works without validation; and (iii) duplicated papers across databases. After initial screening, approximately 310 papers were shortlisted, and 217 studies meeting all criteria were included in this review. To provide a quantitative overview of research activity, a year-wise analysis of the selected publications was conducted. The results indicate a gradual increase in SHM-related publications from 2010 to 2025, followed by a significant growth after 2016. Notably, a sharp rise in publications related to AI-, vision-, and BIM-assisted SHM methods is observed after 2019, reflecting a clear methodological shift from traditional inspection and NDT-based approaches toward data-driven and intelligent monitoring frameworks.

3. State of the Art on Traditional Approaches

3.1. Non-Destructive Testing (NDT): Visual Inspection

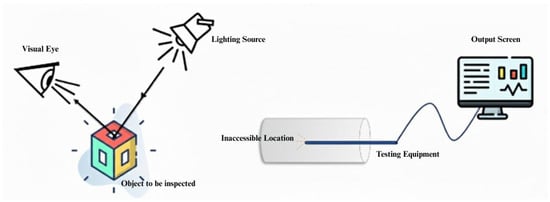

Visual inspection is a fundamental non-destructive testing (NDT) technique used to identify surface level defects such as cracks, spalling, corrosion, and material degradation. It may be conducted manually by trained inspectors or through image based systems employing cameras, unmanned aerial vehicles, or robotic platforms. Visual inspection techniques have historically been used to assess the condition of civil structures and remain the most fundamental form of structural evaluation. In the context of SHM, however, visual inspection is considered as an indirect method because it captures observable surface conditions rather than the physical response of the structure. Indirect visual inspection may be performed manually or using imaging tools, drones, or robotic platforms equipped with cameras (Figure 2). These systems improve accessibility in hazardous or hard to reach locations, enhance documentation quality, and reduce the subjectivity and inconsistency associated with manual inspection. Despite their usefulness, visual inspections can be time-consuming and are often limited in detecting internal defects, thereby motivating the integration of UAVs and robotic systems for more effective coverage and data acquisition [42,43].

Figure 2.

Direct and remote visual testing.

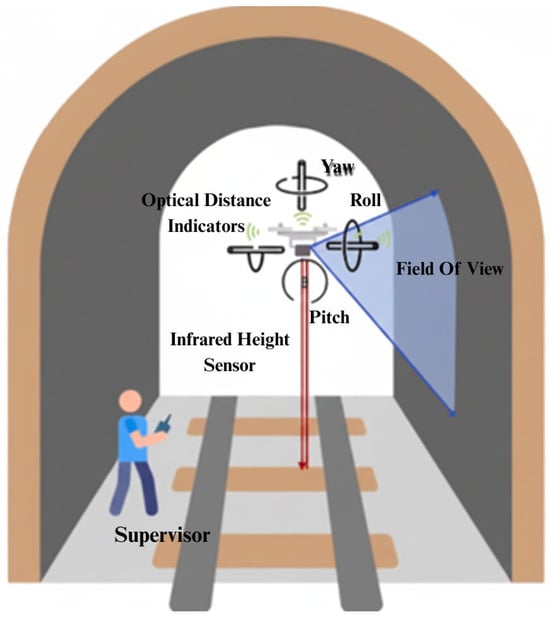

Ivić et al. [44], in their work about visual inspection of complex structures like bridges and wind turbines, suggest a multi-UAV trajectory planning for 3D visual inspection. This would save time, be safer, and save money. They also say that the method could be used for motion control if it could be made more computationally efficient. Ottaviano et al. [45] propose the use of a robotic rover for visual inspection of damages in dangerous and limited-access areas, utilizing inbuilt sensors that enhance accuracy and reliability. Lee et al. [46] carry out a complete survey on the various types of robots employed in the visual inspection of structures and categorize the robots used. He suggests unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) as the best choice for robot-based visual inspection considering the advantages they offer in reliable results. Zhang et al. [47] have proposed a method called PMPP-SD, which involves using UAVs to collect images in a grid pattern from various views and angles for defect detection in the tunnel surface, as illustrated in Figure 3. Researchers have tested the method’s effectiveness in an environment akin to a railway tunnel.

Figure 3.

UAV examination of a tunnel surface [47].

Rožanec et al. [48], however, highlight the fact that visual inspection is highly subjective and limited in scalability and requires repeated observations for better results. Even though there have been a number of studies on visual inspection using UAVs and robotics, their limitations—such as their inability to detect internal structural events or cracks, anomalies brought on by environmental impacts, and the difficulties associated with documentation—have made it necessary to use newer and more effective technologies for the effective detection of structural damages. Documenting the findings requires the use of videography, as it provides an enhanced visual dimension [49]. Several studies have integrated visual inspection using drones and robots with other SHM approaches, such as AI, to enhance accuracy [50]. Belloni et al. [51] in their work investigate the potential of crack monitoring using mobile cameras that automatically detect and measure the crack width using a combination of CNN and photogrammetry and concluded that it has better accuracy in crack width determination when compared to that of sensor-measured value. Integration with AI has significantly enhanced the efficiency and accuracy of damage detection, paving the way for more proactive and data-driven SHM practices.

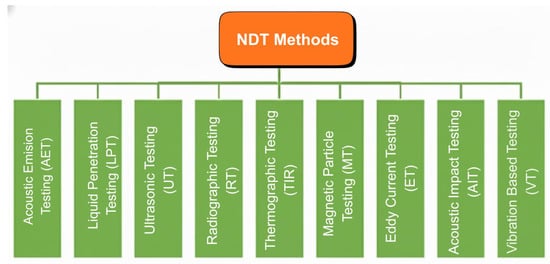

Non-destructive testing has a wide range of applications in areas like manufacturing and fabrication industries, the oil and gas industry, power generation plants, aerospace and aviation, rail and transportation, civil engineering, and infrastructure. When inspecting and evaluating civil infrastructures, non-destructive testing (NDT) is an essential tool. NDT is used to identify damage and improve the utility period of reinforced concrete buildings. It can also be used for restoration to preserve aesthetic and historic value [52]. Cracks, corrosion, delamination, voids, weld discontinuities, and material deterioration are a few flaws that can be detected using NDT. NDT covers methods including acoustic emission testing (AET), liquid penetrant testing (LPT), ground penetrating radar (GPR), thermographic testing (TT), and ultrasonic testing [53,54,55], as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

NDT methods.

NDT methods are used by engineers to monitor structural changes over time. Through periodic inspections using NDT techniques, engineers can identify areas that are prone to degradation, predict future failure locations, and assess how structural conditions change. It is simpler to trace the emergence of defects and assess the effectiveness of maintenance and repair methods when continuous monitoring is conducted using NDT. Katunin et al. [56] state that NDT testing is a cost-effective method that ensures structural integrity and safety. It is a valuable tool for extracting information from buildings and assisting researchers and building scientists in conducting inspections for various purposes [57].

From the systematic review conducted by Boccacci et al. [25], it was validated that the integrated approach of using the NDT technique with other mechanical methods is a comparatively effective approach in damage detection. For better efficiency, NDT methods are usually integrated with AI-based approaches to achieve better accuracy and reliability. NDT and non-NDT, including UPV, rebound hammer, and infrared thermography testing approaches, are also used in the evaluation of historical masonry structures like Malatya Tashoran Church [58]. Monazami et al. [59] used visual surveillance using a thermal camera for the evaluation of carbon fiber-reinforced pavement and deployed other NDT tests such as rebound hammer, electrical resistivity (ER), and UPV on the bus pads. Further NDT tests are also used in the evaluation of carbon fiber-reinforced polymers [60], lime stabilized rammed-earth walls [61], self-compacting concrete [62,63], wooden structures [64], and glass fiber-reinforced polymer [65]. The section below discusses some NDT techniques used in SHM and their recent advancements.

3.1.1. Acoustic Emission (AE) Testing

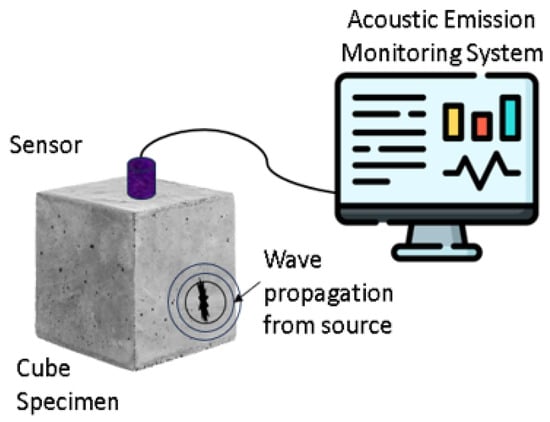

AE is one of the most extensively used NDT tests across the globe. When materials are under stress, AE detects the release of stress waves, also known as acoustic emissions. It is frequently used to monitor the integrity of buildings under stress or to detect the beginning of material deterioration. Figure 5 shows the overall process of AE.

Figure 5.

Acoustic emission overview.

According to the AE testing principle, mechanical stress causes a material to undergo microstructural changes, such as the beginning and spread of fractures as well as displacement and dislocation. The presence and position of faults or structural variations in the material can be determined by detecting and analyzing the stress waves that are released by these changes. It employs two distinct approaches, specifically the transient and continuous methods. It can be used in various applications, namely, weld inspection, thickness measurement, defect detection, rail inspection, material characterization, and corrosion integrity. Several other researchers have discussed and reviewed the uses and application of AE [66,67].

Peng et al. [68] tested the AE method’s ability to record mechanical faults in masonry buildings using a series of small-scale and large-scale samples and tried and failed at each size. An AE-based approach has been applied to the behavior analysis of fiber-reinforced asphalt concrete by integration with digital image correlation, taking various parameters into consideration [69]. Researchers have also used this combination to quantify fatigue cracks in brittle cementitious materials [70]. It is also applied in fluid pipeline leak detection [71], vertical storage tanks [72], and wedge splitting test monitoring in beams [73]. According to Barile et al. [74], despite the benefits of the AE approach, its application is constantly questioned. To address this, a unique procedure for extracting the time of arrival of AE signals is provided. This method employs a modified version of the Akaike information criterion (AIC), which is also applicable to signals with low signal-to-noise ratios.

Van De et al. [75] applied an integrated approach deploying vibration-based monitoring and AE of a corroded reinforced beam and compared the output among the specimens. Various structural components, including beams and plates, have successfully applied vibration-based techniques, utilizing damage indices such as modal flexibility and modal strain energy to detect and locate damage [76]. Several methods have been widely used in the field of SHM, like fundamental modal examination, local diagnostic methods, non-probabilistic methodologies, time series methods, and empirical mode decomposition [77,78]. In the field of vibration-based SHM, signal processing occupies an integral part, focusing on the extraction of the subtle changes in signals for effective damage detection and quantification. Recent developments aim at efficient handling of noisy data in order to ensure efficiency in real-time applications [79]. In bridges and other critical infrastructure, vibration-based structural health monitoring (SHM) systems employ non-destructive sensing techniques to analyze and detect changes that may indicate damage, thereby adopting a proactive approach to infrastructure management [80,81]. For foundations and dams, vibration-based SHM checks the vibration characteristics, especially the frequency components, which are responsive to changes in the underlying media’s properties. This makes them useful for figuring out the condition of structures [82]. The application of 1D CNN in vibration-based damage detection depicts a novel approach allowing for real-time damage detection and localization by automatically extracting optimal damage-sensitive features from raw acceleration signals, demonstrating high performance and computational efficiency [83]. While the theoretical potential of vibration-based damage detection is significant, there are still practical challenges to overcome. Many algorithms face difficulties in real-world scenarios because of issues such as environmental noise and the absence of reference state data. The focus of current researchers is on developing reference-free techniques and improving the reliability of these methods [84,85].

3.1.2. Infrared Thermography Testing

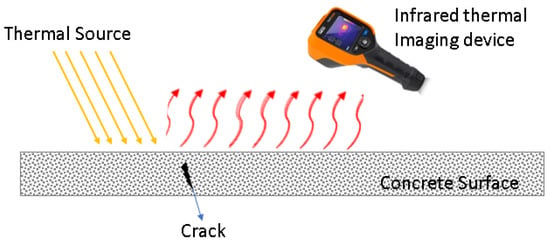

Detecting and characterizing flaws like fractures and delamination is crucial for preventing mechanical failures since they impact the strength of various structural and industrial components [86,87,88]. In this picture, infrared thermography (IRT) has been considered a non-invasive and safe way to identify quasisuperficial flaws [89,90,91,92]. The IRT strategy offers the advantage of being distant. It can be used from a distance ranging from a few millimeters to several kilometers and can distinguish 1-D heat flux sensing and emissivity [93]. This process involves using a light source to elevate the surface temperature of a sample, which leads to heat diffusion. An aberrant temperature distribution in infrared radiation photographs captured using a thermographic camera, known as a thermogram, reveals any internal defects [94]. Figure 6 depicts the use of infrared thermography on FRP composites. Infrared thermography testing is used in the characterization of high-temperature paints [95], investigation of environmental impact on historical buildings [96], and moisture content examination [97].

Figure 6.

Working of infrared thermography.

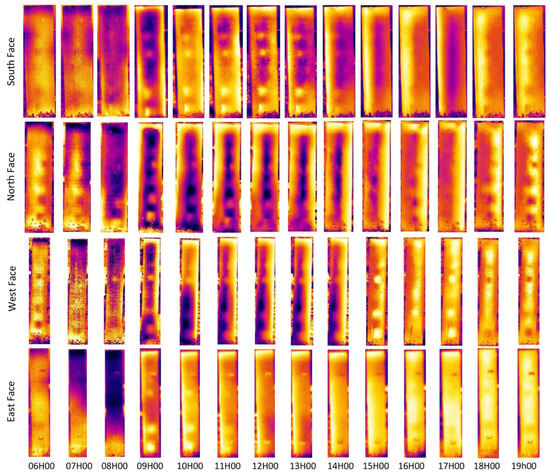

Sagarduy-Marcos et al. [98] used a dimensionless approach for the exploration of minute cracks and solved the resulting equation numerically. Pozzer et al. [99] suggest passive IRT as a quick, secure, and unbound method of NDT and summarize the capabilities of passive IT in subsurface damage detection, taking the limitations also into consideration. Figure 7 shows the raw thermogram images of a concrete column. Integration with AI may enhance the accuracy and reliability of IRT. The images captured using infrared thermal cameras may be used as the input for an AI-based approach, and this helps in the health monitoring of structures to a great extent.

Figure 7.

Thermogram of concrete columns [99].

Liu et al. [100], in their study on the damage detection in asphalt concrete pavement using images obtained from infrared thermography, deployed four CNN object detection models, including five image categories (visible, infrared, and fusion images with varying infrared ratios) and five distress classifications (longitudinal cracking, transverse cracking, fatigue cracking, edge cracking, and potholes), and found that YOLOv5 offered explicit visual explanations (Eigen-CAM) for all image kinds. In addition, fusion images provided an accurate, efficient, and dependable alternate option for detecting pavement deterioration. In this situation, neural networks have shown promise in identifying subtle thermal abnormalities that conventional image processing techniques would normally miss. When compared to traditional techniques, AI-powered systems have shown previously unheard-of precision in differentiating between possible structural flaws and harmless temperature fluctuations, lowering the false positive rate by as much as 40%. Infrared cameras’ increased sensitivity and miniaturization have further transformed this industry. Multi-modal and multi-sensory techniques have become another prominent trend. In order to prevent catastrophic failures and prolong the lifespan of infrastructure assets, infrared thermography may become a more crucial tool for structural health monitoring due to the synergies among artificial intelligence, sophisticated data processing techniques, and advanced sensor technology.

3.1.3. Ultrasonic Testing (UT)

UT deploys high-frequency ultrasonic waves for detecting faults in structures. Fissures, cavities, and the variation in the thickness of elements can be found easily by analyzing the sound waves transmission pattern through the medium and their reflection pattern within the interior of the element. Both high-frequency as well as low-frequency waves may be used for the UT inspection technique. Due to the benefits, they offer with reference to safety, versatility, reliability, and accuracy, UT has occupied its own space of relevance in the field of structural health surveillance, especially when it comes to bulk inspection [101,102]. Figure 8 shows a depiction of UT.

Figure 8.

Ultrasonic testing setup.

Before testing, couplants couple the transducers used in UT with the target material. These couplants enable proper sound wave propagation. The pulse waves transmit through the material and interact with the potential structure. In case of any encounter with anomalies in the internal structure of the material, the pluses get reflected back to the transducer or tend to get dispersed, which is then recorded and further analyzed. An advancement over conventional ultrasonic testing procedures is phased array ultrasonic testing (PAUT), which allows for the use of sophisticated electronic beamforming features like beam steering and linear scanning in addition to sophisticated imaging techniques like the complete focusing approach [103,104,105]. Digital light optical microscopy was used by Premanand et al. [106] to characterize fatigue behavior and analyze the damages that result from fatigue in composite elements. Just like any other NDT method, UT is also used after integration with other AI models [107]. For the automated depth identification of CFRC, Cheng et al. employed three different types of neural networks, including CNN, LSTM, and CNN-LSTM coupled with UT, and found that compared to the other two structures, the CNN-LSTM model provides a more thorough categorization of LVI faults in CFRP based on A-scan data [108].

Ground-penetrating radar [109,110,111,112,113], Schmidt hammer [114], liquid penetrant testing, radiographic testing, and eddy current testing are some other primary NDT techniques, each with unique benefits, constraints, and uses. The material being examined, the kind of fault being sought, accessibility, and the necessary degree of sensitivity all influence the procedure selected.

A common misconception in damage identification is the assumed need for a perfectly pristine, undamaged baseline state for comparison. In real-world scenarios, such a condition is often unavailable, particularly for aging or continuously operational structures. Modern SHM practices instead rely on historical monitoring data, where periodic measurements provide a progressively updated reference. Even if earlier assessments do not represent a fully undamaged state, the comparative analysis of successive monitoring cycles allows detection of damage evaluation, trend deviations, and performance degradation. This approach reduces reliance on an idealized baseline and enhances the practicality and robustness of long-term SHM implementations.

Across the NDT techniques discussed, it is important to highlight the practical limitations and selection criteria associated with each method. Acoustic emission is highly sensitive to micro-cracking activity but is affected by ambient noise and requires complex signal interpretation, making it suitable for continuous monitoring of active damage but less effective for surface level defect mapping. Infrared thermography enables rapid, non-contact detection of shallow subsurface defects but is strongly influenced by environmental temperature variations and emissivity differences, limiting its use in uncontrolled outdoor environments. Ultrasonic testing provides high accuracy in defecting internal defects but requires surface accessibility and coupling materials, making it less suitable for large-scale field inspections. Ground-penetrating radar is effective for detecting embedded elements and voids but exhibits reduced performance in conductive or high moisture materials. Therefore, method selection should consider structure type, defect characteristics, environmental conditions, accessibility, data availability, and the required level of diagnostic accuracy to ensure reliable and cost effective SHM outcomes.

3.2. Summary of Key Insights, Trends, and Research Gap

An examination of the NDT and traditional SHM methods reviewed reveals several significant trends and insights. First, there is a noticeable shift from isolated, method specific inspection practices toward hybrid and multi-sensor frameworks that leverage the complementary strengths of different techniques. Second, recent studies increasingly emphasize automation, particularly through UAVs, robotics, and AI-assisted interpretation, reflecting a broader movement toward minimizing human subjectivity and enhancing inspection efficiency. Despite these advancements, notable research gaps persist. Traditional NDT methods continue to exhibit limitations related to environmental sensitivity, signal noise, penetration depth, and material dependency. Comparative studies also reveal inconsistencies in performance metrics and evaluation protocols, making cross-method generalization difficult. Moreover, SHM datasets commonly lack diversity, long-term monitoring records, and standardized annotations, which restricts the real-world applicability of many proposed techniques. Addressing these gap will require more comprehensive benchmarking studies, standardized evaluation frameworks and greater integration of historical monitoring data to improve the reliability, reproducibility, and comparability of SHM technologies.

3.3. Sensors Based Structural Health Monitoring Using Integrated Multi-Physical Sensors

Modern structural health monitoring systems for buildings are fundamentally based on permanently installed sensors that measure structural responses across multiple physical fields. Commonly deployed sensing modalities include vibration and acceleration sensors for dynamic response monitoring, strain gauges and fiber optic sensors for deformation measurement, acoustic emission sensors for crack initiation detection, and environmental sensors for temperature and humidity tracking. These sensors enable continuous data acquisition, forming the primary information source for condition assessment and damage evaluation analysis in buildings [115,116,117].

Multi-sensor integration enhances damage detectability by capturing complementary structural responses and mitigating uncertainties associated with individual sensing techniques. In particular, vibration-based monitoring is effective for identifying global stiffness changes, while strain and acoustic emission provide higher sensitivity to localized damage mechanisms. Environmental sensing further supports compensation for temperature induced variability, thereby reducing false alarms [118,119,120,121]. Recent studies have demonstrated that combining vibration based monitoring with strain, acoustic emission, and environmental sensing significantly improves reliability, robustness, and diagnostic confidence in building-scale SHM applications operating under real environmental and operational conditions [122,123,124].

4. State of the Art on Novel Approaches

Unlike traditional inspection and non-destructive testing methods that rely primarily on direct physical measurements, novel SHM approaches such as BIM and AI focus on data integration, automated interpretation and long-term decision support. These approaches enhance the analysis and utilization of data obtained from conventional sensors rather than replacing physics-based sensing, in line with established SHM frameworks [125].

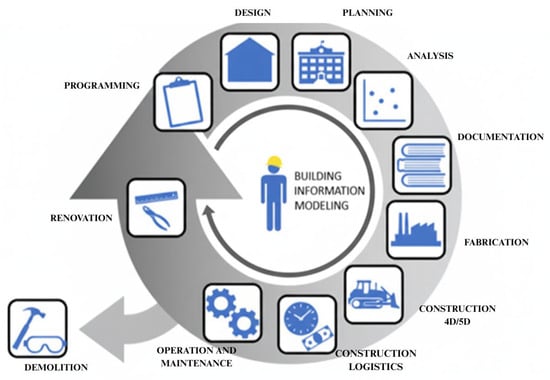

4.1. Building Information Modelling (BIM)-Based Approach

The digital depiction of a structure’s functional and physical attributes during the course of its lifespan is made possible by building information modelling (BIM), which is crucial to structural health surveillance. With the use of geometric, geographical, and behavioral data, BIM generates an extensive digital model of the building. The basis for keeping an eye on the building’s condition and functionality is provided by this model, which faithfully depicts the building’s systems, connections, materials, and parts. By incorporating a variety of SHM-related data types, including design, construction, sensor, and maintenance record data, BIM makes it easier to monitor and analyze the behavior of structures throughout time by combining all pertinent data onto one platform. It is used in construction and civil engineering for design, construction, and life cycle management of structures. Figure 9 shows the overall process of BIM.

Figure 9.

Process of BIM [126].

In their work, Castelli et al. [27] investigate the possibility of integration of the BIM framework in the SHM aspect of structures. It integrates sensor data into the BIM environment from a variety of sources, including IoT devices, remote sensing, and monitoring systems. Data on structural characteristics, including temperature, strain, vibration, displacement, and moisture content, can be obtained using sensors in real time or in the past. It creates algorithms in the BIM environment that use sensor data and BIM features to automatically identify and categorize structural damage. For improved functioning, BIM integrates with other methodologies. Although there are more joint uses of BIM and smart devices, compatibility and interoperability remain a key hurdle to efficient adoption [127,128,129]. Huang et al. [130] investigated the integration of BIM and drones by extracting and depicting data from BIM for drone path organizing during building exterior inspections. Integrating BIM with drones enables experts to make informed decisions based on current information, leading to improved building management and maintenance [131].

In his work, Tang [132] investigated the importance of BIM technology in infrastructure rehabilitation and fortification, highlighting its superiority. BIM is also deployed in association with other NDT techniques for structural assessment. For the effective maintenance of tunnel linings, Zhu et al. [133] developed the TunGPR framework, which uses BIM and blends synthetic data production, data-driven interpretations, and risk management techniques. BIM technology has improved the efficiency, quality, and sustainability of the construction sector while lowering costs and hazards. Further, Tan et al. [134] applied a combined approach using BIM alongside augmented reality and computer vision, deploying the ARDI application that uses YOLOv5 + DeepSORT algorithms for efficient fault tracking and detection from real-time video streams. The application exactly maps fault dimensions from 2D images to 3D coordinates and synchronizes these data with BIM for uploading to the DDM platform. In summary, building information modelling (BIM) improves structural health monitoring by offering a digital framework for data integration, performance analysis, behavior prediction, and maintenance strategy optimization during the structure’s lifetime.

4.2. AI Based Approach

In the recent past, the integration of AI approaches in structural health monitoring has greatly influenced and transformed the detection of anomalies, showing the shift in the process of defect detection to protect the integrity and dependability of important building structures [107]. Flaws in buildings, like the cracks in concrete structures or the corrosion of steel elements, greatly disrupt the safety, sustainability, and economic viability [135].

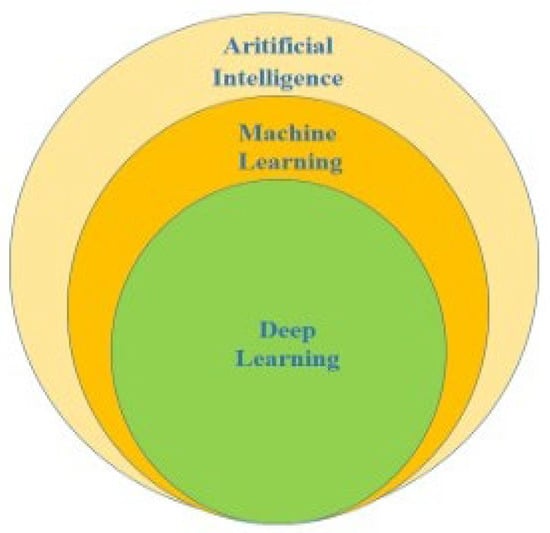

Although traditional inspection methods are proven to be useful in some cases, limitations such as cost efficiency, labor requirements, and inconsistencies lead to their reduced deployment [136]. In addition, more accurate and efficient defect detection methods are required due to the size and complexity of contemporary infrastructures. A new era of fault detection has been ushered in by the emergence of AI, which is driven by the exponential growth of data availability and computer power. The combination of deep learning (DL) and machine learning (ML) algorithms is known as artificial intelligence (AI) as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Subsets of AI.

ML algorithms have proven extremely effective in detecting abnormalities and irregularities within structural components, distinguished by their ability to study patterns and create data-driven predictions [137].

Some techniques utilized in defect detection, particularly fracture and corrosion utilizing machine learning, include support vector machines (SVM), random forests (RF), regression, KNN, decision trees (DT), and K-means clustering. Some of the DL algorithms that are used to find faults are recurrent neural networks (RNNs), CNNs, and generative pretrained transformers (GPTs) [138,139]. Additionally, a computer vision-based method for detecting structural deterioration employs image processing and machine learning techniques to analyze visual data from a variety of sources, including images, videos, and remote sensing imagery. Researchers are working hard to build unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), sometimes known as flying robots or drones, for a variety of uses. When evaluating the improvements in crack detection systems, image processing attracts early interest due to its cost and computational efficiency. [140].

In their study, Mohammad Khorasani et al. [141] evaluated the combination of a computer-based algorithm and AR in the fatigue detection of steel bridges that may not be visible during visual inspection and found that the results showed near real-time results. In order to recover the 2D building surface faults and the 3D information at the local and macro levels at a combined level, Wang et al. [142] suggest a system supported by computer vision in a more economical way to support the facility maintenance management with reasonable accuracy. It is commonly acknowledged that deep learning (DL) and computer vision (CV) approaches are essential technical elements of autonomous, effective, and dependable structural condition evaluations [10,143,144]. Certain strategies have been used to automate damage and structural component recognition in the visual inspection process [145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152]. Following those fruitful demonstrations, it is hoped that CV/DL techniques will eventually be extended to replace all of the labor-intensive and time-consuming manual visual inspection procedures [153].

4.2.1. Limitations and Practical Challenges of AI-Based SHM

Despite the strong performance of AI and deep learning models in controlled studies, their real-world applicability in SHM remains limited by several factors. Many datasets suffer from class imbalance, where defect samples are scarce, leading to inflated accuracy and reduced sensitivity to rare but critical damage. Deep learning models also tend to overfit when trained on small laboratory-generated datasets, making them vulnerable to variations in lighting, weather, ageing, noise, and sensor inconsistencies. A further challenge is domain shift: models trained on one type of structure or imaging condition often fail to generalize to different materials, textures, or field environments. Real-world SHM also lacks the large, annotated datasets needed for robust model training and reliance on augmentation on transfer learning introduces additional uncertainty. Environmental disturbances, occlusions, and sensor failures further degrade model reliability. Accordingly, AI-based SHM should be viewed as a complementary tool that enhances, rather than replaces, traditional sensing and inspection methods.

Beyond algorithmic limitations, several practical challenges hinder the deployment of AI-based SHM systems in real environments. Deep learning models often require substantial computational power, which restricts their use on UAVs, embedded sensors or on-site devices with limited processing capability. Field data are frequently affected by noise, occlusions, vibration and weather driven variations, making stable inference difficult without continuous recalibration. Sensor drift, intermittent sensor failures, and data loss further reduce system reliability during long-term monitoring. Moreover, acquiring large volumes of labelled defect images from operational structures remains costly and time-consuming, limiting the development of robust, generalizable models. These factors demonstrate that effective deployment of AI in SHM requires careful consideration of hardware capacity, environmental variability, and dependable sensing infrastructure.

4.2.2. Machine Learning Algorithms in Defect Detection

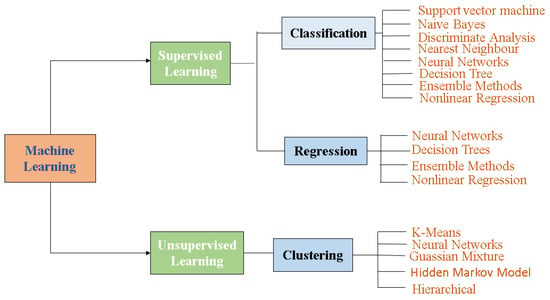

Machine learning (ML) is a subset of AI that attempts to develop mathematical paradigms that can be trained without completely comprehending all of the relevant external factors in order to aid intelligent decision making. It can evaluate complex data and offer precise results in real-time, enabling for smarter decisions without human intervention [154]. Over a decade, ML models have been effectively utilized in a multitude of study domains and areas [155,156,157,158,159], including computational biology [160,161], energy production [162,163], computational finance [164,165], hydrology [166,167], and image and audio processing [168,169]. Additionally, because of its enormous potential, machine learning is receiving a lot of attention in the field of SHM [170,171,172]. It has emerged as an impressive and efficient technology in the accurate detection of defects in structures. These methods are commonly used in the initial stages of data-driven damage identification in SHM [173]. Machine learning also has great potential in automated defect detection when done over a longer period of time [174]. Figure 11 depicts the different types of algorithms used in ML.

Figure 11.

Algorithms used in machine learning [154].

Alamri [27] clearly categorized ML into supervised and unsupervised learning and further classified the algorithms into neural networks, support vector machines, and decision trees deployed in stress corrosion cracking and investigated the cracking mechanism, analysis, and prediction of crack formation. In their study, Ruggieri et al. [175] investigated the potentiality of using machine learning in computerized damage detection on the elements of a bridge using CNN with an image dataset. On the other hand, Rodrigues et al. [176] compared a machine learning detection strategy (using linear regression, random forest, support vector machine, and neural networks) against a cointegration approach for early damage detection. This work adds to the field by testing damage detection systems on real data from a small-scale construction. Through the use of machine learning algorithm models, Spencer et al. [10] confirmed that RF and DT had high accuracy without the need for scaling or hyperparameter tuning. These models included KNN, LSVC, naïve Bayes (NB), DT, RF, and ANN. However, researchers found that scaling the models increased the accuracy of the KNN and ANN models [177].

Ahmadian et al. [178] used the stacking method as an efficient strategy for classifying structural faults, and XGBoost (XGB) may be used for damage identification. Nick et al. [179] in their study investigates the usage of SVM, naive Bayes (NB) classifiers, feedforward neural networks (FNNs), and two kinds of ensemble learning, random forests and AdaBoost. The researchers concluded SVM to be more efficient and AdaBoost exhibited comparatively poor performance. Kalita et al. [180] investigated the fatigue crack development rate of 17-4 PH SS alloy using KNN, DT, RF, and XGB algorithms and discovered that once the active parameters for these algorithms were optimized, the trained models were able to valuate visible data as well as unseen data. Furthermore, they discovered that XGB exhibited higher R2 scores and the least degree of error in its FCGR projections. RF and ANN approaches have been critically reviewed by Imran et al. [181] for the effective corrosion detection in maritime structures.

Shirazi et al. [182] deployed a trained 1D CNN model for the classification of damage labels of a fine element model of a fiber composite and found the model satisfactory in terms of feature extraction and damage prediction. Mirbod et al. [183] suggested an artificial neural network (ANN) model for evaluating critical buildings utilizing hardware and cameras for dependable evaluation. The model uses machine vision, pattern recognition, and an artificial neural network approach. The Utah State University picture dataset was used for the inspection. For the purpose of investigating the corrosion of bridge cables, proposed ML approaches deploying propagation neural networks, radial basis function neural networks, and least squares SVM and concluded that once real-time monitoring data are available, management may use the LS-SVM surrogate model to diagnose and evaluate faults in the cable more quickly and efficiently [184]. Ghiasi et al. [185] have channelized a relative study on the efficiency of ML algorithms like KNN classifiers and the radial basis function Gaussian kernel SVM in the detection of corrosion of steel bridges by developing a tested finite element model image dataset. Table 1 shows the various ML models deployed for defect detection [186].

Table 1.

ML algorithms for defect detection.

Machine learning approaches in structural health monitoring have demonstrated significant utility in both supervised and unsupervised methodologies (including neural networks, support vector machines, and decision trees), proving effective for detecting structural defects like cracks and corrosion while showing variable efficiency depending on the specific application context and defect type that is being analyzed. A comparative study between various ML approaches such as linear regression, random forest, SVM, and neural networks with conventional methods for early damage detection in structures of diverse scales has been carried out. It has been established that some algorithms such as random forest and decision tree had high accuracy without the need for extensive tuning, whereas others such as KNN and ANN models performed better when scaled appropriately. The effectiveness of these methods differs widely by application context, with some algorithms showing better predictive performance for certain defect types like fatigue crack growth, and others being more effective for overall structural fault classification.

4.2.3. Deep Learning Algorithms in Defect Detection

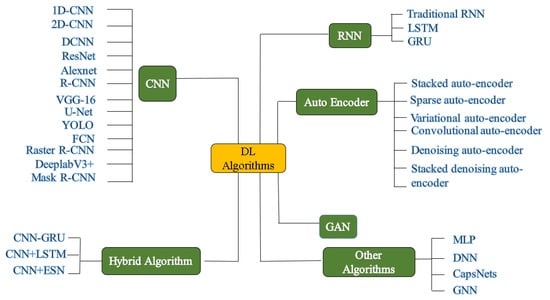

Deep learning (DL) is quickly becoming popular in SHM due to its ability to process large amounts of data and identify complex patterns. DL algorithms can evaluate a wide range of sensor inputs, such as vibration, strain, and temperature, and can automatically learn features from raw sensor data, removing the need for manual extraction. Furthermore, the identification of inconsistencies in the SHM data has greatly relied on DL in recent times [37,195,196,197]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are widely utilized for image-based damage detection, whereas recurrent neural networks (RNNs) or long short-term memory networks (LSTMs) are used for time-series data. Deep learning uses different algorithmic models such as CNN, U-Net, ResNet, FCN, SegNet, DeepLabv3+, Xception, VGG16, ResNet101, InceptionV3, InceptionResNetV2, MobileNetV2, DenseNet169, NASNetMobile, EfficientNetB6, LinkNet, and feature pyramid network (FPN) for SHM in integration with other conventional approaches [198,199]. Figure 12 shows the different algorithms used in deep learning.

Figure 12.

Algorithms used in deep learning [200].

Combinations of several types of DL algorithmic models may be deployed for effective and enhanced defect detection performance. Cha et al. [201] thoroughly investigated the application of deep learning in the field of SHM. Their study focuses on the various DL algorithms and assesses types of modes, operators, and networks; approaches for SHM using DL; and the evolution of DL in the field of SHM. The findings highlight the areas where there is still a scope for improvement and advancements.

Falchi et al. [202] proposed a sensitive and accurate methodology using the temporal fusion transformer network approach for the detection of dynamic properties of a brick-made tower located in Italy. The authors focused on predicting vibrational properties and identifying potential errors in the anticipated behavior based on the actual value. In their work, Yuan et al. [203] proposed an unconventional approach deploying CNN-based R-FPANet for crack identification in structures. The notion of modularization is based on the integration of ResNet 50, feature pyramid network, channel attention module, and position attention module for achieving better results at the field level. A potential integrated method for identifying the crack pattern in structures using DL has been developed by Chambon et al. [204] utilizing the ResNet50 and UNet framework. In this approach, pixel-wise extraction is used to quantify the length of the discovered fracture, and the prevailing usable life of the fractured surface was estimated using an ARMA time series. The aircraft fuselage SHM [204] further confirmed the efficacy of the methodology. To overcome the shortcomings of the prior strain reconstruction model, Chen et al. [205] suggested a strain remodeling approach that includes a nonlinear DL component with a linear autoregressive (AR) component using BiGRU and CNN to enhance the recording of both long- and short-term patterns of the SHM data. The results were evaluated, and it revealed that the hybridized DL and AR model can rebuild the missing data with greater accuracy under diverse conditions than their earlier versions, such as the CNN. A domain adaptation (DA) neural network was created by Lin et al. [206] for the purpose of detecting structural damage. The network was trained using data from both the real structure and the numerical model; input from the damaged real structure was not required. Hou et al. [207] have presented a validated, effective, and unique strategy that integrates DL with an augmentation framework for data imputation of both same and different types of sensors in bridges utilizing a long short-term memory (LSTM) network technique and a generative adversarial network (GAN). In their study, Mazni et al. [208] proposed a ResNet50 approach, utilizing CNN models such as MobileNetV2, EfficientNetV2, and InceptionV3, for the real-time classification and measurement of concrete surface cracks. They also deployed the Otsu method for crack segmentation, concluding that MobileNetV2 is the most accurate and precise approach. Xin et al. [209] propose a DL-based framework for the examination of corrosion in RC structures using the X-ray radiography method in association with CNN-based DL architectural models like FCN, U-Net, SegNet, and DeepLabv3+. They recommend the FCN model as an efficient model. They also recommend Mask R-CNN as a potential choice for segmenting X-ray images.

Using upgraded You Only Look Once version 5 (YOLOv5) and deep convolutional generative adversarial network (DCGAN) networks, Li et al. [210] offer a novel two-stage corrosion detection approach. This provides an ingenious method of bridge maintenance by enabling the prompt categorization of bridge bolts based on varying degrees of corrosion. To improve accuracy, YOLOv5 squeeze and excitation blocks are inserted after each residual block. Comparative experiments show that YOLOv5-SE performs better than YOLOv5 and other models, including Faster R-CNN and VGG16. Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) was utilized by Santos et al. [211] to evaluate the roof system and collect 330 photos in nine buildings. They evaluated six different deep learning techniques: FoveaBox (Fovea), adaptive training sample selection (ATSS), VarifocalNet (Vfnet), side-aware boundary localization (SABL), Retina-Net, and Faster R-CNN. Faster R-CNN, ATSS, and SABL outperformed the other approaches in terms of recognizing and logging equipment placed on big building rooftops. Dang et al. [212] used U-Net, DeepLabV3+, and FPN to automate crack segmentation and quantify the length of cracks in masonry walls.

Zang and Wang [213] proposed a U-Net model for the segmentation of X-ray tomography images for the recognition of corrosion-induced cracking and pores in concrete. An ensemble of hybrid self-designed CNN and transfer learning models is proposed by Mayya et al. [214] for the effective and precise intelligent fracture detection in bridges. Pretrained transfer learning models are used in the study to assess how well transfer learning detects fractures in bridge deck photos. These models include the VGG16, VGG19, ResNet50, MobileNetV3Small Model, InceptionResNetV2, EfficientNetV2B0, Xception, and InceptionV3. Forkan et al. [215] propose the CNN-based correlation detector method, which extracts corrosion features and identifies structural elements from drone-based photos using a unique ensemble deep learning technique. In their study, Mostafa et al. used transfer learning (TL) and deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) to detect cracks in concrete structures. Multiresolution image analysis based on the wavelet transform is also the primary step in the crack segmentation, and the outcomes showed that DCNN classifier models function well [216]. The work by Xu et al. [217] suggests a new approach based on the combination of an enhanced DeepLabv3+ algorithm, a fissure propagation benchmark approach, and an image processing strategy to monitor the whole crack development process, including real-time crack recognition and real-time monitoring of crack dynamic expansion.

Fang et al. [218] put forth a CNN methodology for the detection of fissures with a suitable signal noise ratio and deploy a Bayesian probability approach for the reduction of abnormalities in the detection. Using more than 7000 publicly accessible data points, Tabernik et al. [219] employed a unique architecture called SegDecnet++ to identify cracks in concrete and pavements and tested the effectiveness of the technique in real time. Several retraining techniques were adopted to train the existing models in the identification of cracks in pavements [220] and concrete using transfer learning and other similar techniques. Further, models were trained using images of RC elements in earthquake-prone areas for the identification of the reason for failure in structures using a deep transfer learning algorithm [221].

Using manually created features taken from photos, early research in the machine learning (ML) approach mostly focused on feature-based ML models such as SVM, decision trees, and random forest. In order to improve performance, recent studies employ hybrid ML-DL techniques or pre-trained CNNs for automatic feature extraction. Early research on the deep learning (DL) technique relied on shallow CNN architectures such as VGG16 and AlexNet. ResNet, EfficientNet, and transformers (ViTs) are used in contemporary research to improve accuracy and generalization. The accuracy of traditional machine learning models ranged from 75% to 85%, but they had trouble with real-world instances. By learning hierarchical features from raw photos, DL models are now able to attain greater accuracy (>90%). In contrast to the previous dependence on accuracy, the introduction of IoU, F1-score, and precision–recall curves allows for a more thorough examination. Real-time crack detection on IoT devices, drones, and lightweight mobile applications is made possible by recent developments in deep learning. combining data from sensors and images for more accurate detection. In order to illustrate crack detection decisions, recent research incorporates Explainable AI (XAI) approaches such as Grad-CAM, SHAP, and LIME.

Deep learning (DL) algorithms on the other hand have transformed structural health monitoring by facilitating processing of large sets of data and uncovering intricate patterns without feature extraction. Studies have proven the viability of combined methods involving different neural network geometries to identify crack patterns, utilizing pixel-wise extraction to measure crack sizes and time series analysis to predict remaining structural life. The versatility in DL model is witnessed in various research works suggesting diverse architectural strategies for real-time concrete surface defect measurement and classification. The comparative advantage is especially obvious in complicated applications wherein classical feature engineering would otherwise be extremely cumbersome or incomplete for reflecting intricate patterns in structural health data.

5. Comparative Study

There has been a significant shift in measuring and maintaining structural integrity using structure health monitoring (SHM), including both traditional and advanced SHM processing methods. Traditional procedures, such as visual inspections and non-destructive testing (NDT), have supported SHM for decades, but they have limitations, mostly due to their reliance on human labor, time constraints, and surface detection technologies. On the other hand, emerging methodologies based on technology such as AI, machine learning, and BIM deliver a more complete, faster, and accurate response. Table 2 shows a comparison of classic and new approaches, highlighting their uses, efficiency, and limitations.

Table 2.

Comparative study between traditional and novel approach.

AI-based and BIM integrated SHM approaches offer clean advantages in large-scale inspection, automated damage localization and continuous monitoring, particularly for surface-level defects captured using images and sensor networks. Deep learning models are effective in identifying subtle crack patterns and reduce subjectivity associated with manual inspection. However, traditional SHM techniques such as vibration-based monitoring, acoustic emission, and ultrasonic testing remain more reliable for internal defect detection, material characterization, and safety critical assessment due to their strong physical interpretability and robustness to environmental variations. AI-based methods are highly dependent on data quality, labelled datasets and computational resources and their performance may degrade under domain shifts and noisy field conditions. Therefore, AI approaches should be viewed as complementary rather than substitutive, with hybrid SHM frameworks combining physics-based sensing and data-driven analytics providing the most reliable and practical solution.

A successful SHM system should combine old and new approaches. This comprises visual inspections, non-destructive testing (NDT), sensor technologies, and AI-driven procedures. Environmental considerations, computational efficiency, cost efficiency, and sensor deployment accessibility must all be carefully considered in order to achieve scalability, reliability, and adaptability while ensuring structural safety, performance, and lifespan.

AI-based technologies, such as machine learning (ML) for feature-based predictions and deep learning (DL) for complicated, automated flaw detection, are particularly effective for real-time analysis and large-scale implementations. However, they require a large amount of computational power and high-quality datasets. To maximize SHM efficiency, users must align their chosen approach with the type of defect, the available data, and the desired precision. Table 3 depicts the method and the types of structures for which it can be used. Related approaches to SHM might be chosen based on the type of data collected and the application’s requirements. Visual inspection is the preferred choice for early evaluations and external damage overviews. However, it has subjectivity and scalability constraints; therefore, it is best used in conjunction with UAVs or AI for automation. NDT techniques are great tools for detecting internal and surface flaws, with each having distinct strengths—for example, AE is a real-time fault, IRT is a contactless subsurface examination, and UT is very accurate for interior faults. Furthermore, BIM contributes to a project’s holistic lifecycle management by integrating structural health monitoring data with maintenance records, as well as demanding a higher quality of setup and interoperability.

Table 3.

SHM Approaches applicable for various structures.

Over the last five years, the AI tools used in structural health monitoring for acoustic emission (AE) testing have undergone transformative changes fueled by major technology advancements. As AI and machine learning have become more common in the AE industry, results have gotten better and faster. This is because evolutionary pattern recognition can now track even the smallest changes in the underlying structural model at a deeply detailed level. Miniaturized, highly sensitive wireless sensors deliver real-time, continuous monitoring over critical infrastructure, from wind turbine blades to complex engineering structures. These developments have not only led to more accurate damage detection but have opened the road for smart, self-monitoring structures to autonomously identify and report possible failure, which is yet another step toward predictive maintenance.

Within the field of ML, DL focuses on algorithms inspired by the architecture and functionality of neural networks found in the human brain. While compared to the conventional machine learning techniques, deep learning has the capability to manage and analyze massive amounts of data, and further, the identification of intricate patterns becomes easier with DL. Both machine learning and deep learning create models that can automatically identify patterns and draw conclusions from data. However, the competence of deep learning systems to study the hierarchical data representations makes the difference. In order to capture complex patterns and characteristics, deep learning demands the requirement of multiplex layers of linked neurons or nodes to improve the abstract representations of the input data. In order to extract handmade characteristics from raw data, a technique called feature engineering is frequently necessary for traditional machine learning methods. Conversely, deep learning algorithms are able to automatically extract meaningful information through successive layers of neural networks. In order to extract handmade characteristics from raw data, a technique called feature engineering is frequently necessary for traditional machine learning methods. Conversely, through the successive layers of neural networks, DL algorithms are able to automatically extract meaningful characteristics from raw data. Deep learning models become more flexible for various tasks and datasets as a result of eliminating the necessity for human feature engineering. From civil infrastructure such as bridges and buildings to aerospace components and industrial gear, AI integration has the potential to change maintenance processes, reduce downtime, and maintain peak asset performance. Machine learning (ML) applications frequently use several algorithms to evaluate photographs or sensor data, identifying problems like corrosion and cracks.

In spite of extensive progress in ML and DL methodologies, several less explored areas continue to exist in the practice of structural health monitoring. Existing sensing technologies, such as ultrasonic, acoustic, and infrared testing, are still not sufficiently reliable, sensitive, and environment friendly. Studies further validated these constraints, particularly highlighting how environmental factors can substantially compromise the accuracy of the sensor. Additionally, former analysis attest that the fusion of heterogeneous data from diverse types of sensors poses great challenges in developing unified, actionable knowledge for structural evaluation. The previous literature emphasizes the fact that existing data used for AI model training are often not diverse and large enough to support stable real-time analysis and prediction in diversified real-world environments. Furthermore, there is still a lack of adequate investigation into structural response under extreme load conditions like earthquakes, high winds, or large loads, and studies highlighted how this knowledge gap constrains the development of monitoring systems that can accurately assess structures during critical incidents. It is suggested that future investigations must aim to create advanced frameworks for effective data fusion employing various complementary methods of testing for enhancing AI training, emphasizing the importance of simulation-based training data, and studying structural behavior at extreme conditions for next-generation SHM systems that can further advance safety monitoring functions.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the most commonly deployed traditional and novel structural health monitoring approaches. Damages are mainly due to cracking and corrosion in buildings, bridges, and pavements, and the proposed health monitoring approaches were collected from a literature survey of past papers. For each approach, their basic methodology and the recent advancements in the field are explained in detail. After careful analysis, it is clear that both classic and new approaches play critical roles in guaranteeing the integrity and safety of infrastructure. The study concludes with the following findings.

- Visual inspections and NDT approaches have long been used in SHM as they are dependable and easily understood techniques. Their ongoing evolution and integration with current technology ensure their relevance and efficacy.

- However, the introduction of innovative SHM approaches, particularly those that take advantage of the breakthrough in artificial intelligence, represents a substantial shift in the industry. The integration highlights the significance of a diverse strategy that incorporates both time-tested techniques and cutting-edge technologies.

- Hybrid systems, which incorporate the benefits of both techniques, can provide more dependable, comprehensive, and cost-effective monitoring options due to their efficiency and precision.

- It is evident that compared to the other SHM approaches, methodologies that involve deep learning algorithms have several advantages due to their accuracy, precision, and the ability to handle massive amounts of data. DL algorithms assess various sensor inputs, such as vibration, strain, and temperature, and automatically learn features from raw data, eliminating the need for manual extraction, identification, and categorizing the types of structural deterioration, including fractures, corrosion, and deformation.

- Various DL algorithmic models, such as CNN, U-Net, ResNet, FCN, SegNet, DeepLabv3+, VGG16, VGG19, ResNet50, MobileNetV3Small Model, InceptionResNetV2, EfficientNetV2B0, Xception, InceptionV3, and much more, are widely used for SHM in integration with other conventional approaches. This paves the way for effective and enhanced defect detection performance.

- However, there is still room for enhancement in the results achieved. Paradigms may be further trained with more varieties of datasets, and also combinations of models may be put to trial to accomplish improved results.

- In summary, this review highlights a clear shift in building-focused SHM from traditional, physics-based inspection techniques toward data-driven and integrated frameworks. While conventional methods such as visual inspection and non-destructive testing remain essential for reliable internal damage assessment and physical interpretability, AI-based and BIM integrated approaches provide improved scalability, automation and continuous monitoring capabilities. Nevertheless, current research reveals key gaps related to data dependency, limited generalization, computational demands and real-world deployment challenges. Addressing these limitations using hybrid SHM frameworks that combine physics-based sensing with data-driven analytics represents a critical direction for advancing reliable and practical SHM systems.

7. Future Recommendations

Structural health surveillance is very critical when it comes to maintaining and evaluating the integrity and performance of the structure. Although the field has undergone significant advancements in the past decade, there are still more areas with a scope for improvement. Future considerations in this field must mainly aim at the enhancement of the efficacy and reliability of the monitoring systems influencing technologies that are still emerging and also handling the limitations with the existing systems. Some of the areas of future scope in the field are as follows:

- Existing sensing technologies like ultrasonic, acoustic, and infrared testing have limitations in terms of their reliability, sensitivity, and applicability in different environments. Improvised sensing technology may be developed to address the same.

- Many sensor types, such as strain gauges, accelerometers, and fiber optic sensors, are used in SHM systems to give a variety of datasets. It is difficult to integrate and fuse this disparate data to obtain precise and useful insights. Hence, the creation of sophisticated frameworks and algorithms for efficient data fusion and integration to improve the resilience and dependability of SHM systems becomes needful.

- The collection of data from multiple NDT tests to train the AI phase would improve the accuracy and reliability of the system.

- Existing models make use of datasets that are limited and not diverse enough to train the AI models; however, the deployment of a large variety of datasets would help the model perform real-time analysis and prediction. Hence, FEM simulations may be used to create datasets to pretrain the existing models.

- Under extreme circumstances like earthquakes, strong winds, or heavy loads, structures may respond differently. In order to ensure safety, this conduct has to be observed and understood. Research into how structures behave in harsh environments and the creation of monitoring systems that can precisely track and forecast how structures would react in such situations can be modelled.

Author Contributions

M.K.S.—Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Validation; Writing—original draft. R.M.D.—Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. K.S.E.—Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Validation; Writing—review & editing. S.A.—Formal analysis; Validation; Visualization; Writing—review & editing. G.S.P.—Formal analysis; Validation; Writing—review & editing. S.S.—Formal analysis; Visualization. P.M.K.—Visualization; Funding acquisition; Supervision; Writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Faqih, F.; Zayed, T. Defect-based building condition assessment. Build. Environ. 2021, 191, 107575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knyziak, P.; Kowalski, R.; Krentowski, J.R. Fire damage of RC slab structure of a shopping center. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 97, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, P. (Ed.) Corrosion Mechanisms in Theory and Practice; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gagar, D.; Foote, P.; Irving, P.E. Effects of loading and sample geometry on acoustic emission generation during fatigue crack growth: Implications for structural health monitoring. Int. J. Fatigue 2015, 81, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Huang, M.; Zhang, W.; Guo, M.; Liu, B. Progressive collapse of multistory 3D reinforced concrete frame structures after the loss of an edge column. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2022, 18, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Ge, Z.; Wang, D.; Shang, N.; Shi, J. Self-sensing joints for in-situ structural health monitoring of composite pipes: A piezoresistive behavior-based method. Eng. Struct. 2024, 308, 118049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Xia, Y.; Weng, S. Review on field monitoring of high-rise structures. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2020, 27, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Iyela, P.M.; Su, Y.; Atlaw, M.M.; Kang, S. Numerical predictions of progressive collapse in reinforced concrete beam-column sub-assemblages: A focus on 3D multiscale modeling. Eng. Struct. 2024, 315, 118485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Xin, T.; Zhenggang, H.; Minghua, H. Measurement and analysis of deformation of underlying tunnel induced by foundation pit excavation. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2023, 2023, 8897139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, B.F.; Hoskere, V.; Narazaki, Y. Advances in computer vision-based civil infrastructure inspection and monitoring. Engineering 2019, 5, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]