Case Study of CO2 Cascade Air-Source Heat Pump in Public Building Renovation: Simulation, Field Measurement, and Performance Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

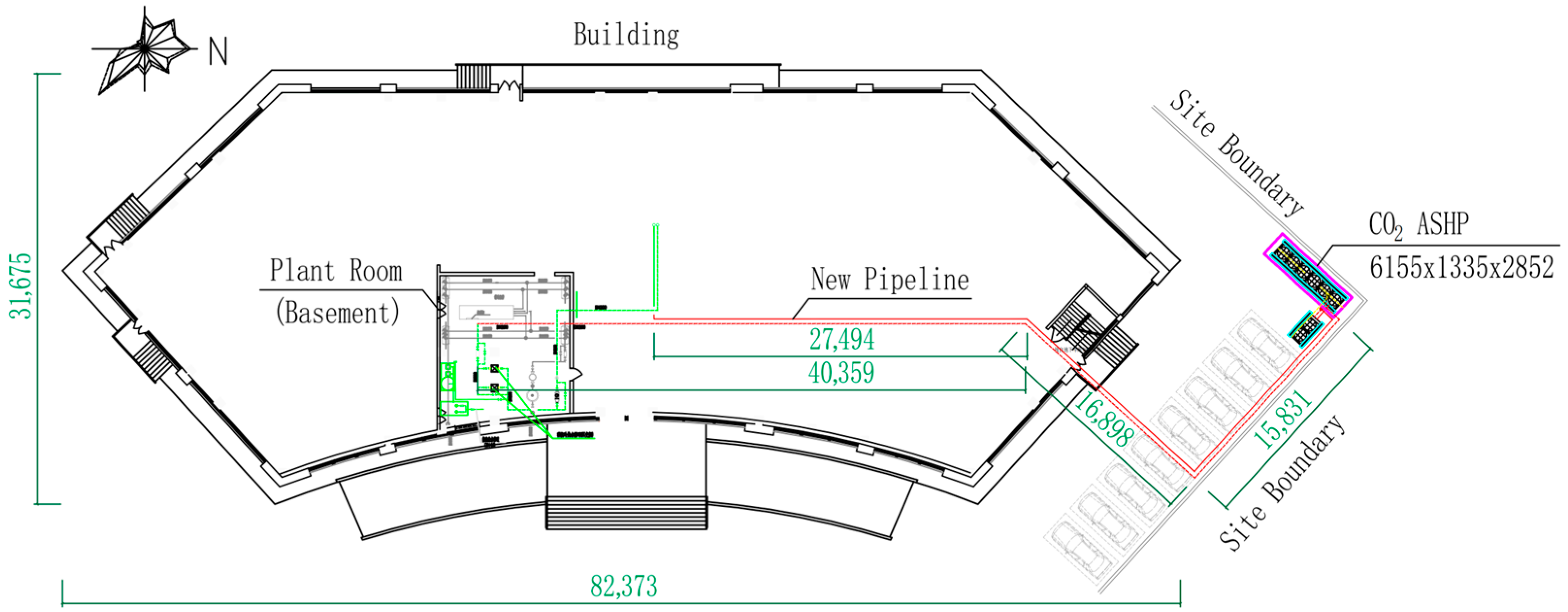

2. Project Description

2.1. Scheme Comparison

2.1.1. Water Source Heat Pump

2.1.2. Urban Central Heating System

2.1.3. CO2 Cascade Air-Source Heat Pump

2.2. Select Scheme Description

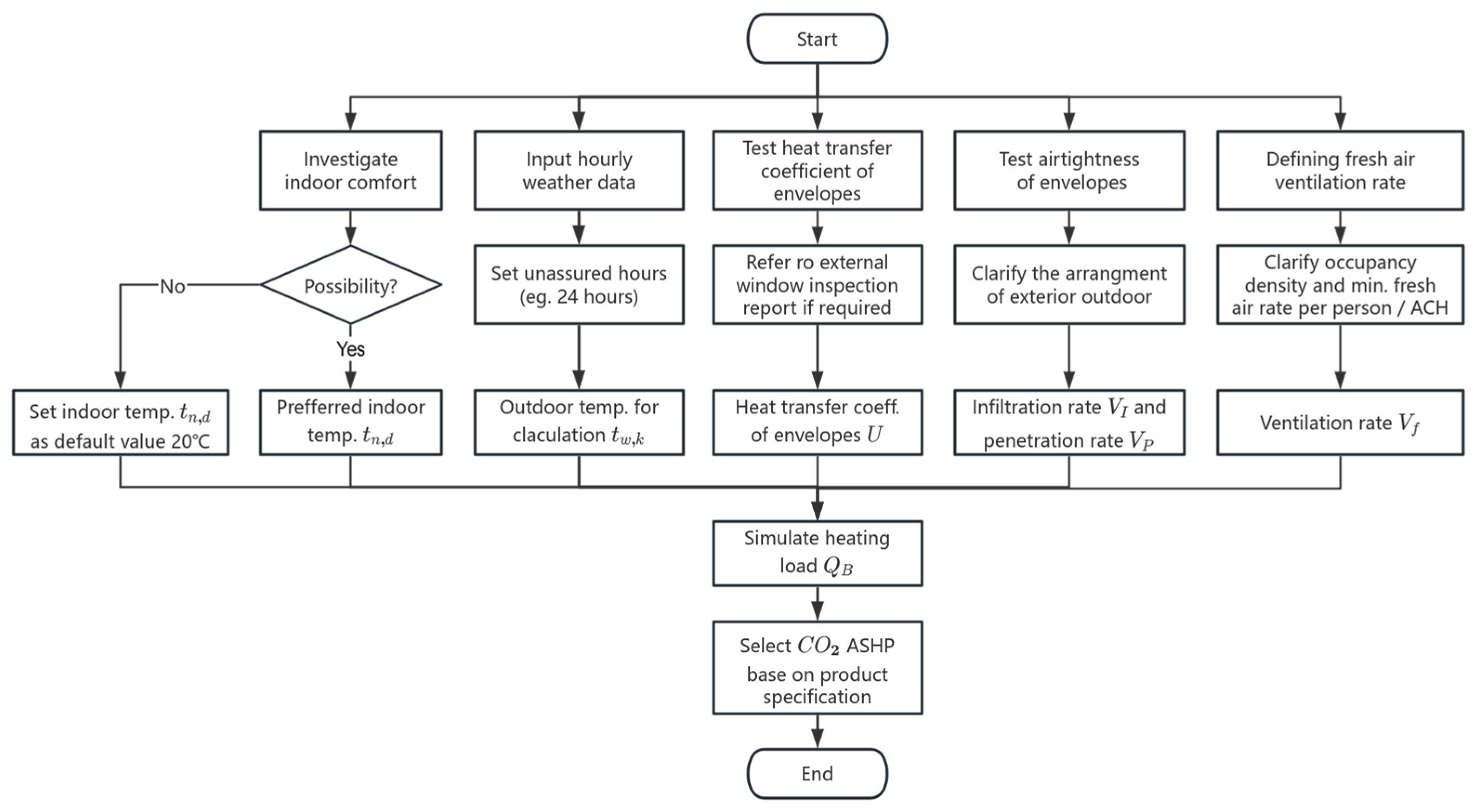

3. Optimal Design

- (1)

- Building envelope-related parameters: On-site testing of the heat transfer coefficient and airtightness of building envelopes is essential, especially for renovation projects. Envelope aging over time degrades its thermal performance, and on-site test data is far more reliable than theoretical values.

- (2)

- Outdoor design temperature: As previously noted, the unassured rate derived from hourly data is higher than the daily-based value specified in current standards [16]. For reference, standards from developed countries such as the ASHRAE Handbook adopt outdoor design temperatures based on hourly data with unassured rates of 0.4% and 1.0% [26]. Thus, local historical hourly data should be used to revise outdoor temperatures for heating load calculation where applicable. The unassured rate can be varied based on building function, with a 1-day (24 h) unassured rate recommended for most scenarios.

- (3)

- Indoor temperature: Indoor temperature should be optimized based on occupancy preferences. If no specific preference is provided, a setpoint of 20 °C is recommended, as studies confirm it as a widely accepted comfort temperature [27].

3.1. Thermal Performance Testing of Envelope

3.2. Indoor and Outdoor Design Temperature Discussion

3.2.1. Indoor Temperature for Design

3.2.2. Outdoor Temperature for Design

3.3. Heating Load Simulation

4. Data Measurement

5. Performance Analysis

5.1. Indoor Temperature Measurements

5.2. Heating Coefficient Measurements

5.3. Economic and Environment Benefit

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- To enhance indoor comfort reliability and derive more realistic heating loads, a flexible parameter-adjustment design approach combining on-site testing and simulation is proposed. First, testing the heat transfer coefficient and airtightness of building envelopes is strongly recommended. Second, the target indoor condition is defined based on occupant preferences, with a minimum of 20 °C. Third, for heating load simulation, the outdoor temperature should be determined by hourly temperature data rather than daily temperature data, with a recommended unassured rate of one day (24 h). Finally, the building total heating load is simulated using the parameters determined above. The ASHP is then selected based on the optimized heating load and its heating capacity at the refined outdoor temperature. In this paper, CO2 ASHP is adopted as a case study due to its excellent low-temperature adaptability and high efficiency. Other ASHPs that can also operate stably and efficiently at extremely low temperatures are equally suitable for this approach.

- (2)

- Using the optimally defined heating load simulation in Chengde, the CO2 cascade ASHP was selected for a renovated public building and ensured reliable indoor comfort even on the coldest days and operating at high efficiency. During the 2023–2024 heating season, the lowest hourly outdoor temperature reached −22.2 °C, at which the average indoor temperature remained 22.4 °C and the COP of the ASHP was 2.70.

- (3)

- Based on the above research and analysis, it is recommended to develop a new heating standard based on low-temperature ASHP technology. This standard should provide hourly meteorological parameters or optimized outdoor design parameters for major cities, as well as standardizing appropriate adjustment strategies. All these measures aim at ensuring indoor comfort while improving energy utilization efficiency.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASHP | Air-Source Heat Pump |

| CDD | Cooling Degree Days |

| COP | Coefficient of Performance |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| HDD | Heating Degree Days |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning |

| TMY | Typical Meteorological Year |

| WSHP | Water Source Heat Pump |

| Nomenclature | |

| expanded uncertainty of each instrument according to its calibration certificate | |

| heat transfer area of envelope (m2) | |

| average specific heat of supply and return water at constant pressure (kJ/(kg·°C)) | |

| specific heat of outdoor air at constant-pressure (kJ/(kg·°C)) | |

| actual heating performance coefficient of heat pump | |

| coverage factor | |

| number of independent measurements | |

| average input power of heat pump, kW | |

| building total heating load (W) | |

| heat loss through building envelopes (W) | |

| basic heat load of the rth room (W) | |

| heat loss due to cold air infiltration and penetration (W) | |

| total heat load of the rth room (W) | |

| heat loss for ventilation (W) | |

| heating capacity of heat pump (kW) | |

| indoor design temperature for winter (°C) | |

| temperature of return water (°C) | |

| temperature of supply water (°C) | |

| outdoor dry bulb temperature for calculating in winter (°C) | |

| heat transfer coefficient of the main part of the envelope (W/(m2·°C)) | |

| expanded uncertainty | |

| type A evaluation of measurement uncertainty | |

| type B evaluation of measurement uncertainty | |

| combined standard uncertainty | |

| flow rate of return water (m3/h) | |

| air flow rate of infiltration (m3/h) | |

| air flow rate of penetration (m3/h) | |

| air flow rate of ventilation (m3/h) | |

| average of the measured values | |

| measured value for each measurement | |

| modification rate for orientation (%) | |

| modification rate for exterior wind force (%) | |

| modification rate for ground floor exterior door infiltration (%) | |

| modification rate for extra high room height (%) | |

| Greek symbol | |

| correction factor for temperature difference | |

| heat recover rate (%) | |

| average density of supply and return water (kg/m3) | |

| density of outdoor air (kg/m3) | |

References

- Tsinghua University Building Energy Research Center. Annual Development Research Report on China’s Building Energy Efficiency 2025 (Urban Residential Special Topic); China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Clean Heating Industry Committee. China Clean Heating Industry Development Report 2024; China Economic Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- The State Council the People’s Republic of China. North China Winter Clean Heating Plan (2017–2021). Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-12/20/5248855/files/7ed7d7cda8984ae39a4e9620a4660c7f.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Heat Pump Committee of China Energy Conservation Association. China Heat Pump Industry Development Report 2023; Heat Pump Committee of China Energy Conservation Association: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Action Program to Promote High Quality Development of Heat Pump Industry. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202504/content_7016926.htm (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Heat Pump Committee of China Energy Conservation Association. White Paper on Heat Pumps Contributing to Carbon Neutrality (2021); Heat Pump Committee of China Energy Conservation Association: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). The Future of Heat Pumps in China; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Hao, J. Research Progress and Prospect of Air Source Heat Pump in Low Temperature Environment. J. Refrig. 2013, 34, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W. Research on Heating Performance Improvement of Quasi-two Stage Variable-frequency Air Source Heat Pump at Low Ambient Temperature. Ph.D. Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Shen, B.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Shirey, D. Heating performance of an air source heat pump with a portable thermoelectric subcooler. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 73, 106542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China. CO2 Air Source Heat Pump Heating Technology. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xwdt/gdzt/qgjnxcz/jnjsyy/jzjejs/202006/t20200626_1232105.html (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Song, Y.; Cui, C.; Yin, X.; Cao, F. Advanced development and application of transcritical CO2 refrigeration and heat pump technology—A review. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 7840–7869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. China National Program for the Implementation of the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (2025–2030). Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk03/202504/t20250423_1117396.html (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Wang, W.; Ni, L.; Ma, Z. Air-Source Heat Pump Technology and Application; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Ni, L. Capacity Selection of Air-source Heat Pump Based on Outdoor Design Temperature for Heating. Heat. Vent. Air Cond. 2023, 53, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Research on Climatic Design Information. Master’s Thesis, China Academy of Building Research, Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Xu, C.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Y. Optimal design strategy of selection and combination to multi-air source heat pump units for central heating. Int. J. Refrig. 2023, 145, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Xu, C.; Yang, Y. Optimizing the selection and combined operation of multiple air-source heat pumps for sustainable heating systems. Energy Build. 2024, 310, 114052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Wang, W.; Wei, W. An improved equivalent temperature drop method for evaluating the operating performances of ASHP units under frosting conditions considering their configuration and operation. Energy Build. 2025, 331, 115370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, L.; Shi, L.; Xu, W.; Wang, T. Field test of a CO2 cascade air-source heat pump. J. Refrig. 2023, 44, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Xu, W.; Li, X.; Shi, L.; Wang, T.; Li, L.; Yang, C.; Yuan, J.; Han, Y.; Liu, Z. Application and Test Analysis of CO2 Cascade Air Source Heat Pumps in Distributed Heating Systems for Cold Areas. Build. Sci. 2025, 41, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50176-2016; Code for Thermal Design of Civil Building. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Standing Committee of the Hebei Provincial People’s Congress. Hebei Province Groundwater Management Regulations. Available online: https://hbepb.hebei.gov.cn/hbhjt/zwgk/zc/101645876394089.html (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Zhang, J. High-quality to Promote Building Heating Development Through Energy-saving and Low-carbon Transformation. Energy China 2024, 46, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Heat Pump Professional Committee of the China Energy Conservation Association. Carbon Dioxide Heat Pump White Paper; Heat Pump Professional Committee of the China Energy Conservation Association: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- An, J.; Xu, W.; Pan, Y.; Yan, D. Study on Outdoor Design Conditions for Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning Design. Build. Sci. 2023, 39, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50736-2012; Explanatory Notes to the Design Code for Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning of Civil Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012; Volume 2.

- JGJ/T 177-2009; Standard for Energy Efficiency Test of Public Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Standing Committee of the Heilongjiang Provincial People’s Congress. Regulations on Urban Heat Supply in Heilongjiang Province. Available online: https://flk.npc.gov.cn/detail2.html?ZmY4MDgxODE3ZDBlYTdhNTAxN2QxMWIyMDQ4MTAzZTc (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- GB 50736-2012; Design Code for Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning of Civil Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012; Volume 1.

- ASHRAE. 2021 ASHRAE Handbook: Fundamentals; ASHRAE Publishing: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- JGJ/T 346-2014; Standard for Weather Data of Building Energy Efficiency. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2014.

- Ma, Z.; Yao, Y. Air Conditioning Design for Civil Buildings, 3rd ed.; Chemical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 50801-2013; Evaluation Standard for Application of Renewable Energy in Buildings. China Architecture & Building: Beijing, China, 2013.

- JJF 1059.1-2012; Evaluation and Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- GB/T 25127.1-2020; Low Ambient Temperature Air Source Heat Pump (Water Chilling) Packages—Part 1: Heat Pump (Water Chilling) Packages for Industrial & Commercial and Similar Application. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- GB 24500-2020; Minimum Allowable Values of Energy Efficiency and Energy Efficiency Grades of Industrial Boilers. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- GB/T 2589-2020; General Rules for Calculation of the Comprehensive Energy Consumption. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. 2024 National Electricity Carbon Footprint Factor. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk01/202510/W020251024569470952545.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- National Development and Reform Commission. Guidelines for Accounting and Reporting of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Public Building Operation Enterprises. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/tz/201511/W020190905506437983335.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2025).

| Envelope | Exterior Wall | Exterior Roof | Exterior Window |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat transfer coefficient (W/(m2·°C)) | 0.483 | 0.400 | 2.700 1 |

| Leakage (m3/(m·h)) | — | — | 2.0 |

| Name | Value | Name | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unit type | Integral unit | Overall dimensions/mm | 6155 × 1335 × 2852 |

| Nominal heating capacity (−12 °C)/kW | 585 | Heating capacity (−19 °C)/kW | 515 |

| Nominal input power (−12 °C)/kW | 202 | Input power (−19 °C)/kW | 200 |

| Nominal heating COP | 2.90 | heating COP (−19 °C) | 2.58 |

| Testing Instrument | Uncertainty (k = 2) |

|---|---|

| Thermo-hygrometer for indoor use | 0.2 °C |

| Thermo-hygrometer for outdoor use | 0.2 °C |

| Thermometer | 0.3 °C |

| Flow meter | 2 × 10−3 |

| Electrical parameter tester | 5 × 10−3 |

| Outdoor Temperature/°C | Average COP | Expanded Uncertainty (k = 2) | Relative Expanded Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|---|

| −20 | 2.83 | 0.027 | 0.96% |

| −15 | 3.00 | 0.025 | 0.84% |

| Type | Supplied Heat/kW·h | Efficient | Energy/tce | Cost/Yuan/m2 | Carbon Emission/tCO2/a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central heating | 1.10 × 106 | - | 134.6 | 32 | 434.0 |

| CO2 ASHP | 2.89 | 46.5 | 26 | 218.8 | |

| Electricity boiler | 0.97 [37] | 138.9 | 79 | 652.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ma, L.; Yuan, J.; Wang, T.; Shi, L.; Feng, A.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Li, D. Case Study of CO2 Cascade Air-Source Heat Pump in Public Building Renovation: Simulation, Field Measurement, and Performance Evaluation. Buildings 2026, 16, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010157

Ma L, Yuan J, Wang T, Shi L, Feng A, Zhang W, Li X, Li W, Li D. Case Study of CO2 Cascade Air-Source Heat Pump in Public Building Renovation: Simulation, Field Measurement, and Performance Evaluation. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010157

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Li, Jing Yuan, Tiansheng Wang, Lin Shi, Ashley Feng, Weipeng Zhang, Xiaoyu Li, Wei Li, and Dexin Li. 2026. "Case Study of CO2 Cascade Air-Source Heat Pump in Public Building Renovation: Simulation, Field Measurement, and Performance Evaluation" Buildings 16, no. 1: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010157

APA StyleMa, L., Yuan, J., Wang, T., Shi, L., Feng, A., Zhang, W., Li, X., Li, W., & Li, D. (2026). Case Study of CO2 Cascade Air-Source Heat Pump in Public Building Renovation: Simulation, Field Measurement, and Performance Evaluation. Buildings, 16(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010157