Abstract

The aim of this study is to investigate the potential use of rapidly increasing agricultural wastes in concrete production by substituting them for cement, thereby reducing their environmental impact and producing eco-friendly concrete. For this purpose, concrete samples were produced using a combination of almond shell biomass (ASB) and silica fume (SF). These samples were subjected to standard compressive strength tests as well as ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV), porosity (P), and maturity (M) tests. In addition, the microstructure of the samples containing ASB and SF was examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The test results show that the combined use of ASB and SF in concrete production significantly improves the strength properties, and the best results were obtained from the ASB6SF10 series. A significant increase of 37.7% was observed in the compressive strength values of the ASB6SF10 series from the early age between 3 and 28 days. UPV and P values were obtained as 4.46 m/s and 10%, respectively. The use of ASB and SF in concrete production has been found to be critically important in terms of the mechanical and physical properties of concrete and environmental benefits. The results of the study show that ASB and SF have potential for use in concrete production and can contribute to more sustainable concrete production, waste management, and the circular economy by reducing the negative environmental impacts arising from this production.

1. Introduction

The construction industry is a constantly and steadily growing sector, and in parallel, the dependence on supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) is also increasing. This situation leads to environmental challenges such as carbon emissions, resource consumption, and waste storage issues. Numerous studies are being conducted to combat these challenges. Most of these studies focus on integrating cement-based materials into concrete. The use of SCMs in concrete aims to reduce carbon emissions and produce more environmentally friendly and economical concrete [1]. The construction sector also plays an important role in reducing these carbon emissions. International climate agreements clearly demonstrate the importance of this issue. The Renovation Wave strategy, which came to the fore under the “European Green Deal” and prioritizes energy and resource efficiency, emphasizes this issue [2,3]. Again, within the same scope, according to a United Nations (UN) report, cement, which is the primary binding material in construction, accounts for approximately 3 billion tons of annual production, and this figure is expected to double to approximately 6 billion tons over the next 50 years. This situation also highlights the increasing demand for construction materials [4,5]. From another perspective, for example, the Paris Agreement encourages countries to set their own national climate plans with better targets. To this end, the necessary work and initiatives must be undertaken regarding the current trajectory of carbon emissions [6]. In this context, the use of industrial or agricultural waste as cement-based material is recommended by many researchers [7,8].

With growing global concerns about sustainability and resource conservation, the construction industry is increasingly focusing on reducing its carbon footprint. One of the best solutions for this is to replace cement in concrete production with various cement-based materials [9,10,11]. Industrial and agricultural wastes are commonly used in cement-based materials known as SCM. Numerous studies have been conducted on agricultural waste types. However, although agricultural wastes are widely used in concrete production, the effect of almond shell biochar (ASB) on concrete has not been fully evaluated. Reviewing the few studies conducted on ASB, it is reported that ASB has the potential to be used as a partial substitute for cement in concrete [12,13].

The development of environmentally friendly concrete stems from the need to reduce environmental problems by both minimizing pollution caused by cement production and recycling waste generated by industrial production. In this context, various types of agricultural waste have been evaluated for use in concrete [14,15]. Chen et al. have stated in their studies that biochar facilitates the cement hydration process and the formation of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel, thereby increasing the mechanical strength of concrete. Furthermore, in their life cycle analysis, they confirmed that the addition of biochar significantly reduced CO2 emissions with the addition of SCMs [16,17]. In another study, a sustainable method was developed by incorporating biochar derived from waste wood into concrete. The study found that the use of biochar supported the formation of additional cement hydrates due to its moisture-regulating effect, and that adding 1% biochar by weight increased compressive strength by 8.9%. On the other hand, they noted that using 5% biochar reduced compressive strength [18].

Although positive results have been achieved with the use of agricultural waste types in concrete, most studies have focused on mortars and remained limited in scale. Very few studies have examined the combined use of agricultural wastes and SCMs in concrete production and evaluated this combination. Nelson et al. investigated the effect of using alkoxy, metakaolin, and blast furnace slag as SCMs on the mechanical properties of concrete. Their work revealed that these SCMs improve compressive strength when used at optimal ratios, as presented in the literature [19]. The use of cement, partially ground almond shell ash, and recycled concrete aggregate in mortar production resulted in increased flexural strength but decreased compressive strength [20]. Similarly, in a study examining the effect of almond shells on self-leveling mortar, eight SCM series were prepared using textile dye-impregnated almond shells. Quantitative analyses were performed on the prepared series using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), X-ray Diffraction Analysis (XRD), Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS), and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) to determine their durability properties [21].

In recent times, efforts to dispose of and recycle environmentally harmful waste have come to the fore in the construction sector in building materials [22,23]. Contributing to sustainability and producing environmentally friendly concrete provides significant ecological benefits. A comprehensive review of the literature reveals that there are very few studies on the combined use of ASB and SF in concrete production. In this regard, researching the potential use of locally readily available ASB and SF in concrete will significantly reduce the storage problem of these materials and lessen their environmental impact, while also enabling the production of more environmentally friendly concrete by reducing the amount of cement used. For this, the potential use of ASB, which is locally available and produced in large quantities from agricultural waste, as a cement replacement in combination with SF has been examined. For this purpose, a total of 7 concrete series containing ASB at 3%, 6%, and 9% ratios and SF at 10% ratio were prepared, including 1 reference sample. Destructive and non-destructive tests were applied to the prepared series on the 3rd, 7th, and 28th days. As a result, it was observed that the use of ASB has a significant effect on the mechanical and physical properties of concrete. This study reports that ASB, a type of agricultural waste with pozzolanic properties, can be effectively used in certain proportions together with SF and has significant environmental benefits. Furthermore, the combined use of these two materials in concrete contributes significantly to the circular economy, sustainability, and the problem of agricultural waste storage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Properties of Materials

The cement used in the study is CEM I 42.5 R Portland cement type produced according to TS EN 197-1 standard [24]. This cement was supplied by the local Elazığ Birlik concrete company. Silica fume was supplied from Antalya Eti Metallurgy. The chemical and physical compositions of cement and silica fume are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Physical and chemical properties of the cement and SF (%).

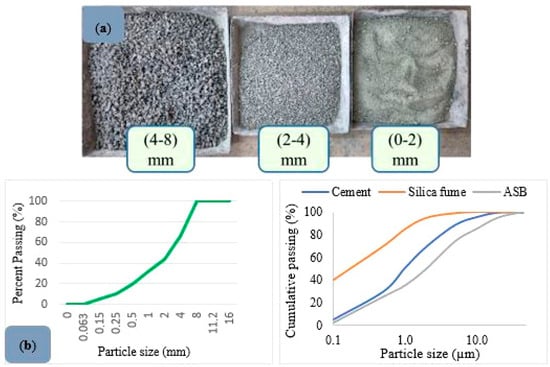

Andesite was used as fine aggregate, and basalt was used as coarse aggregate, and they were classified as (0–2) fine-1, (2–4) fine-2, and (4–8) coarse mm. The particle size distribution of the aggregate, cement, ASB, and SF materials used in the study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(a) Classified aggregates; (b) Particle size distribution of aggregates and other materials.

Almond Shell Biochar (ASB)

Almond shells are one of the lignocellulosic agricultural wastes. In terms of chemical composition, they are rich in cellulose (20–35%), hemicellulose (10–15%), and lignin (8–16%). They also contain approximately 7–8% ash [25]. This content is important in terms of the presence of oxides such as SiO2 and Al2O3, which may exhibit pozzolanic activity [12]. Almond shell ash has been evaluated in both energy production and chemical conversion processes due to its carbohydrate-rich structure. In addition, its richness in phenolic compounds with antioxidant properties raises the potential for chemical durability. However, its direct use in building materials has not yet been systematically researched. Although studies on the use of sustainable SCM-based materials are increasing, there is no significant research on the combined use of ASB and SF, particularly for strength and durability. The ASB used in this study was supplied by the Elazığ Biomass Energy Facility (BEF). Almond shells arrive at the facility in their shells and are subjected to pyrolysis, meaning they are held at 650–800 °C in an oxygen-free environment for a certain period of time. During this process, the volatile substances within the material are gasified, and the resulting gas is called syngas. Electricity is generated from this synthesized gas using specially manufactured gas generators. As a by-product of the gasification process, carbonized biochar is obtained from the system. The composition of biochar varies depending on the type of raw material used. ASB is one of the biochars with both high calorific value and high fixed carbon content [25,26].

The ASB obtained from BEF was ground into a fine powder using a grinding device at the Fırat University Building Materials Laboratory. As a result, organic waste is disposed of in a “zero waste” manner, electricity is generated from the gas released, and the biochar material obtained is reused in the industry [27]. The analysis results of the almond shell biochar used in the study are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Analysis data of almond shell biochar.

2.2. Mix Design

In the experiments, the cement dosage was selected as 350 kg/m3. A total of 7 concrete series were prepared, and the mix ratios for the series are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mix proportion of concrete (kg/m3).

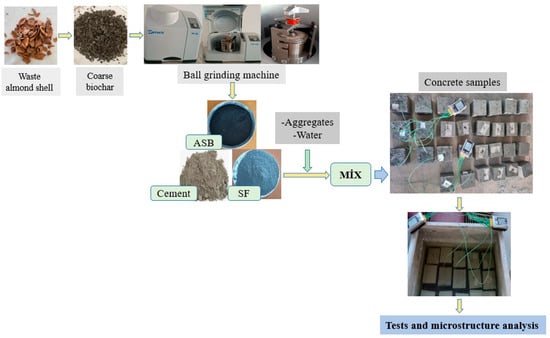

When producing concrete samples, in the first stage, the binding materials and aggregates were mixed as a dry mixture for approximately 2 min. Then, mixing water was added and the mixing process was continued for another 4 min. After this process, the mixture was poured into 100 × 100 × 100 mm3 molds and placed on a shaking table to ensure homogeneous settlement. From the very beginning, cables belonging to the temperature measurement device were placed inside the concrete to determine the temperature development. After 24 h, the samples that had set were placed in a curing tank. On days 3, 7, and 28, standard compressive strength tests were performed on the samples, along with ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV), porosity (P), and maturity (M) tests. The flow chart for the study is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart for the study.

Preparing the Temperature Datalogger and Placing the Thermocouples

Another test conducted as part of the study is the maturity test. This test estimates the compressive strength of concrete at an early age, allowing the formwork removal time to be determined [28,29]. This provides advantages in terms of time and cost during the project period [30,31]. Two methods were used to estimate strength using the maturity method. The first of these is the Nurse-Saul method given in Equation (1), in which compressive strength is estimated by looking at the temperature history of the concrete [32].

Here, M represents the maturity index (°C-hour or °C-day), T represents the average concrete temperature (°C), T0 represents the reference temperature, t represents the elapsed time (day or hour), and ∆t represents the time interval (day or hour).

The second method is the Arrhenius equation calculated based on the equivalent age concept proposed by Freisleben, Hansen, and Pedersen (Equation (2)). In 1960, Copeland et al. suggested that the effects of cement hydration on the rate of strength development in concrete could be described by the Arrhenius equation [33]. The standards related to the test are specified in ASTM C1074 [34].

Here, te is the equivalent age at the reference temperature, E is the apparent activation energy, R is the universal gas constant, T is the mean absolute temperature of the concrete, and Tr is the reference temperature.

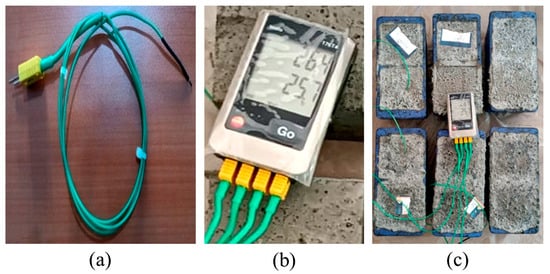

A four-channel Testo 176-T4 thermometer was used to determine concrete temperatures in the maturity calculations. The device was set up to take measurements every 5 min after the concrete was poured and placed in the mold and placed on the samples (Figure 3). As specified in ASTM C1074, the temperature results taken every 5 min at the end of the 1st, 3rd, 7th, 14th, and 28th days were transferred to the computer.

Figure 3.

(a) Maturix thermocouple, (b) Concrete temperature datalogger; (c) Placing the thermocouples into the sample.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results of Compressive Strength Tests

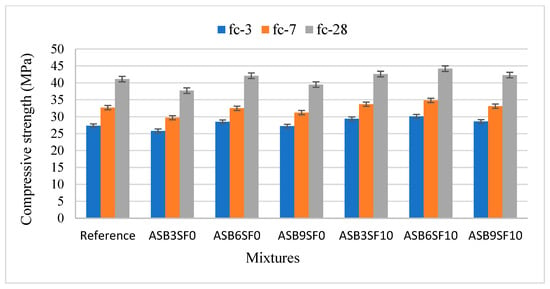

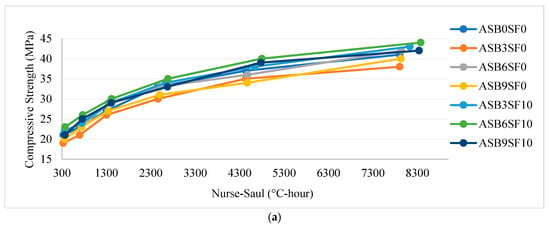

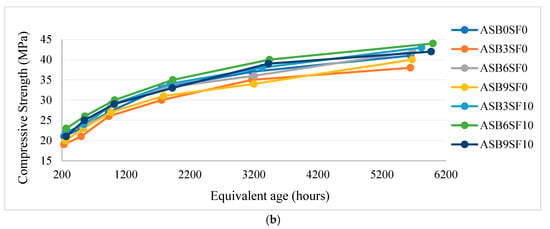

Figure 4 shows the strength development of eco-friendly concrete with ASB and SF additions at different curing ages. The specified curing ages are 3, 7, and 28 days, respectively. When examining the compressive strength graph, it is generally observed that at each curing age, there is a decrease in strength with a 3% ASB addition compared to the reference series, an increase in strength with a 6% ASB addition, and a decrease with a 9% ASB addition thereafter. In the series where SF was used together with ASB, the highest strength value was again in the ASB6SF10 series, with values of 30.1, 34.8, and 44.2 MPa on the 3rd, 7th, and 28th days, respectively. The highest strength value at each age was obtained from the series with 6% ASB content. In particular, a significant increase of 37.7% was observed between the 3-day and 28-day compressive strength values in the ASB6SF10 series with SF additive. On the other hand, ASB usage above 6% resulted in decreases of 4.8%, 4.9%, and 4.3% in the strength values on the 3rd, 7th, and 28th days, respectively. Substituting cement with ASB up to a certain ratio affects strength improvement. However, as other researchers have noted, ASB usage beyond a certain level has a negative effect on strength gain as the biochar dosage increases. This is thought to be due to a decrease in the amount of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) [35,36]. In general, significant increases in compressive strength have been observed with ASB usage ranging from 3% to 9% and SF usage at 10%. However, the most suitable increase was achieved with 6% ASB usage. This situation demonstrates that ASB has significant potential for reuse from agricultural waste.

Figure 4.

Compressive strength test results.

The results obtained from the compressive strength tests conducted on concrete samples produced by reducing the amount of cement and replacing it with ASB and SF clearly demonstrate that this study is effective and that the substitution of cement with waste materials has potential for use in concrete. When evaluated from an environmental perspective, the global cement consumption for 2023 is approximately 4114 million tons. Cement-related CO2 emissions account for approximately 7–8%. Considering that the construction sector is a continuous and growing industry, reducing CO2 emissions in the cement industry, which has high consumption and demand, is of high importance in the context of combating climate change and achieving net-zero targets [37]. Therefore, as an alternative to cement, reducing the amount of cement and using waste in certain proportions plays an important role in carbon emissions [36,37,38,39,40].

Environmental Assessment

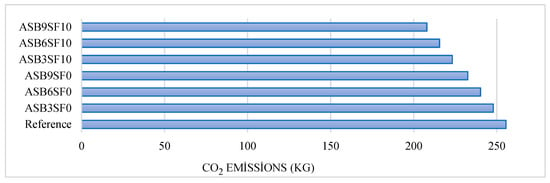

In the environmental impact assessment of the materials used in the study, CO2 emission values of 6.6 × 10−5 and 2.5 × 10−2 CO2/t were taken for ASB and SF, respectively [40,41]. Figure 5 was obtained as a result of the environmental impact assessment calculations. The comprehensive assessment in Figure 5 reveals that the use of ASB and SF in concrete production significantly reduces CO2 emission values. Furthermore, it is clearly seen that the amount of cement used has an effective impact on the carbon emission value.

Figure 5.

CO2 emission intensity.

3.2. Results of Porosity and UPV Tests

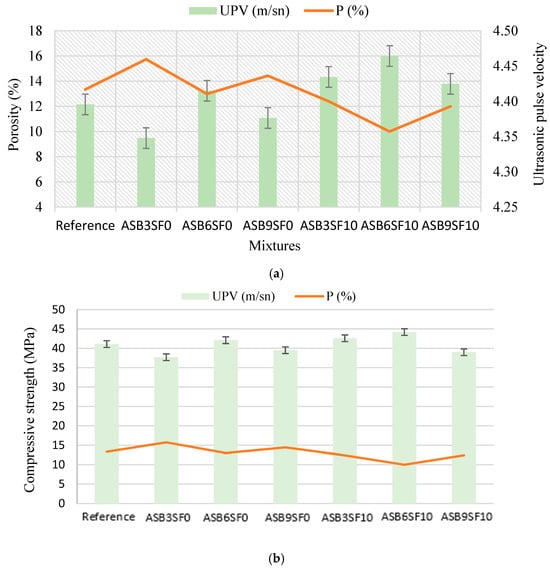

After a 28-day standard curing period, porosity and UPV tests were performed on the concrete specimens (Figure 6). Upon examining Figure 6a, a similar trend in compressive strength was observed in the ASB6SF10 series, which had the lowest porosity and highest UPV value. With the increase in ASB content and the addition of SF, the microstructure of the concrete reaches a higher compactness, which leads to a decrease in porosity. Due to their chemical structure, biochar reduces the formation of ettringite in concrete and ensures that the concrete has a denser structure [41,42,43].

Figure 6.

(a) Porosity and UPV test results (b) Comparison of compressive strength with porosity and UPV values.

When examining the UPV results for Figure 6a,b, it is clearly seen that UPV values increase as porosity decreases in parallel with porosity values. When comparing the UPV value of the reference sample with the concrete series produced with ASB, it was found to be higher than the ASB3SF0 and ASB9SF0 series and lower than the other series. When the concrete samples were evaluated according to Whitehurst’s definition, all series were found to be of “good” quality [44,45,46]. Therefore, replacing cement with waste material enables the production of high-quality concrete with fewer pores. This demonstrates that ASB-enhanced concrete series have a significant impact on the compressive strength of concrete.

3.3. Maturity Test

History of Concrete Temperature

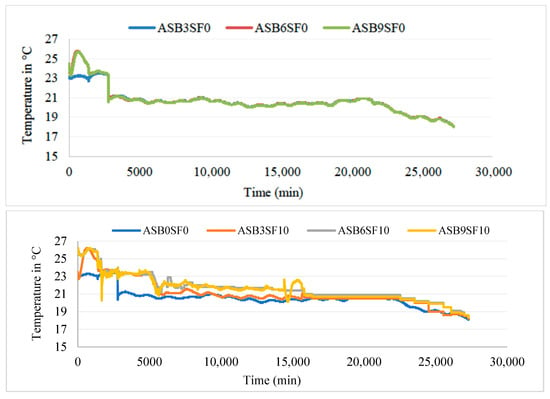

The maturity method in construction provides significant advantages in terms of the fast and safe execution of construction work. This technique converts the temperature history of concrete into real-time strength prediction [47,48,49]. One of the tests performed in this study is the maturity test. Figure 7 shows the temperature change of cured samples over 28 days.

Figure 7.

Time-dependent temperature change curves of concrete.

Figure 7 shows the 28-day temperature change of the concrete series. Upon examining the graph, we can observe that the heat release of the ASB-SF-added concrete series is higher than that of the other series. When comparing the series without SF addition to those with SF addition, it is evident that the hydration reactions have accelerated and heat release has increased due to the addition of silica fume. In parallel with the compressive strength results, it is clearly seen that the highest temperature value is in the ASB6SF10 series.

When examining Figure 8, it is observed that the maturity index depends on curing age and curing temperature and plays an important role in predicting early age strength. [28,50]. It has been observed that as the compressive strength value increases as specified in the C1074 standard, the maturity values also increase linearly. The lowest maturity value was observed in the ASB3SF0 series, where the temperature change value was also low. This indicates that hydration continues with increasing temperature, leading to greater C-S-H gel formation and consequently higher compressive strength values [51].

Figure 8.

Comparison of (a) Compressive strength-Nurse-Saul values; (b) Compressive strength-Arrhenius maturity values.

3.4. Analysis of Microstructure

The microstructure analyses conducted within the scope of the study consist of SEM-EDX and SEM–Mapping scans.

Analysis Results

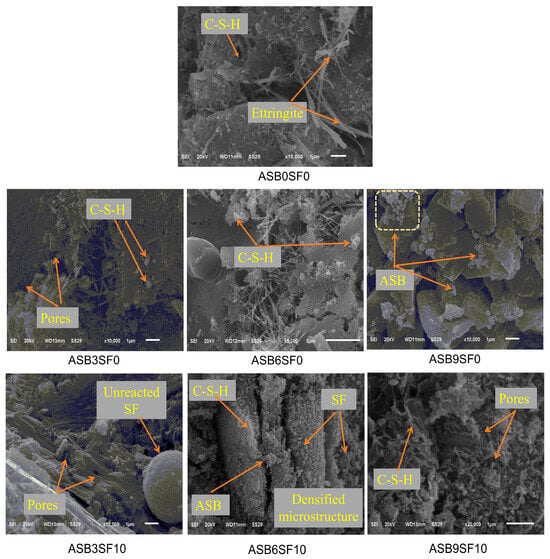

SEM-EDX results were obtained on seven concrete series, including the reference mixture, after 28 days. SEM-Mapping was performed on the reference mixture and the ASB6SF10 series, which was the optimal mixture. The analyses were conducted by the Bingöl University Central Laboratory Application and Research Center (BUMLAB) using small pieces taken from the samples after the standard compressive strength test.

Figure 9 shows the analysis of hydration products, which is an important aspect of microstructure studies. Pores, ettringite formations, and C-S-H were observed in the reference mixture. The addition of ASB and SF supported C-S-H formation and contributed to the filling of pores. As the ASB ratio increased in the series containing 0% SF, ridges and, some material accumulated in piles. Due to the pile-up formed with the increasing ASB ratio, hydration could not occur sufficiently, and after a certain ratio, this situation caused a decrease in strength [52,53]. When the reference series is examined, it is seen that there are pores and cracks, and the addition of ASB supported C-S-H gel formation and created a filling effect in the cracks.

Figure 9.

SEM-EDX test results.

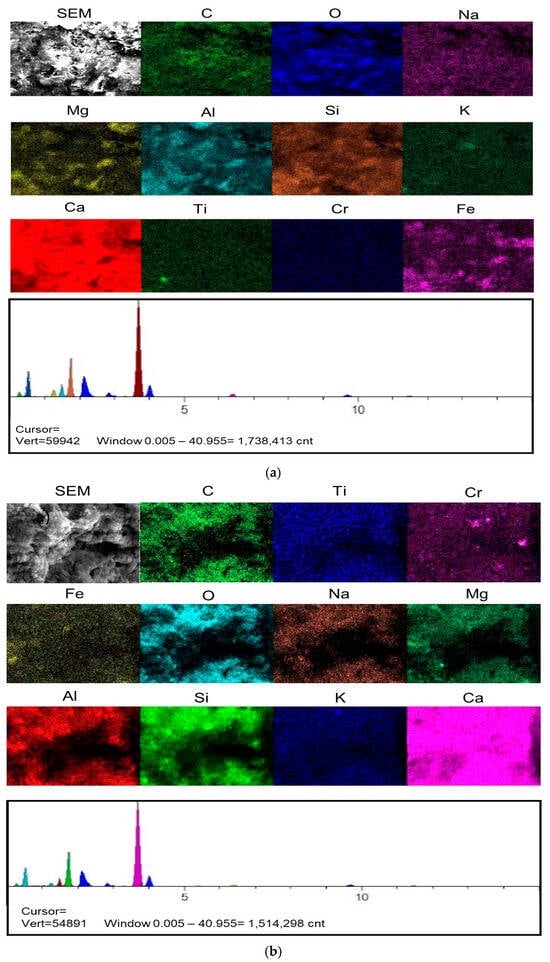

The analysis conducted based on the SEM-mapping scan results determined the element concentrations within the material (Figure 10). In the SEM mapping graph of the reference series, the weight percentages of elements such as Carbon (C), Oxygen (O), Sodium (Na), Magnesium (Mg), Aluminum (Al), Silicon (Si), Calcium (Ca), and Iron (Fe) are approximately 7.76%, 41.02%, 0.35%, 2.29%, 3.52%, 10.0%, 31.95%, and 2.61%, respectively. In the SEM-mapping graph of the ASB6SF10 series, the weight percentages of elements such as Carbon (C), Oxygen (O), Sodium (Na), Magnesium (Mg), Aluminum (Al), Silicon (Si), Calcium (Ca), and Iron (Fe) are approximately 6.24%, 39.20%, 0.96%, 1.52%, 2.97%, 11.28%, 35.09%, and 1.87%, respectively.

Figure 10.

SEM images and SEM-mapping analysis (a) ASB0SF0 reference series; (b) ASB6SF10 series.

When compared to the element patterns of the reference mixture, the element patterns of the ASB6SF10 series contain a significant amount of calcium. SEM–Mapping scans highlight the compositional difference between the reference concrete and the environmentally friendly concrete with ASB and SF additions. The cement with ASB and SF substitution changes the element distribution ratio in the concrete. The most significant element change ratio was in the calcium content, at 9.86%. This is because calcium is one of the most important components in the hydration process [54,55]. This situation contributes significantly to the strength development process of concrete. This increase in calcium content has resulted in higher mechanical properties compared to the reference concrete. This situation can affect the durability and performance of concrete in the long term.

4. Conclusions

In this research study, ASB and SF materials were used as SCM in environmentally friendly concretes, and the performance of sustainable concrete was evaluated. The effect of these materials on the mechanical and microstructural properties of concrete was investigated. Based on the experimental results and SEM analysis results, the following findings were reached.

- The experiments and analysis results obtained within the scope of this study will provide preliminary information on the use of agricultural waste in concrete production.

- Replacing approximately 6% of ASB with cement provides higher compressive strength at all curing ages. At the same time, the addition of a second mineral admixture, SF, further improves the strength value. The combined use of 6% ASB and 10% SF provided the best compressive strength result. Therefore, this ratio will guide researchers in the use of agricultural and industrial waste and prevent the need for numerous trial mixtures. This will result in significant savings in time, cost, and labor.

- The strength of concrete, in terms of porous structure, tended to decrease due to increased porosity when cement was replaced solely with ASB. This situation indicates that sufficient hydration cannot be achieved with an increase in the ASB ratio, resulting in the formation of a porous structure. An increase in compressive strength was observed with only 6% ASB. However, the combined use of ASB and SF successfully achieved the increased compressive strength trend.

- While the use of ASB and SF in concrete production is beneficial in terms of the concrete’s mechanical properties and performance, these materials also provide significant gains in terms of ecology and the circular economy.

- According to microstructure analysis results, the addition of ASB also created a filling effect, resulting in a denser concrete structure throughout the surface. On the other hand, the use of 9% ASB has caused localised segregation in some areas. This has negatively affected the hydration of the cement and led to a decrease in strength values. In light of the data obtained from the experimental results, it is recommended to use approximately 6% ASB and 10% SF in applications.

In conclusion, this study strongly suggests that reducing the amount of cement in normal-strength concrete plays a significant role in obtaining more environmentally friendly concrete by reducing CO2 emissions. Using almond shells for energy production and utilizing the ash produced as a by-product in the materials sector yields multiple benefits, including contributions to sustainability, ecological gains, and solutions to storage problems. As a recommendation for future studies, using biochar with a higher amorphous silica content will further improve concrete performance. The type of biomass material used in the pyrolysis process varies depending on its high silica content. Therefore, it is anticipated that studies on agricultural waste by-products can evaluate the performance of these materials in concrete using different materials.

Author Contributions

M.E.T.: Research, conducting experiments, data collection, writing. T.D.: Methodology, writing, review, editing, verification. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit of Fırat University (FÜBAP), grant number TEKF.25.25.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding this study.

References

- Yurt, Ü.; Bekar, F. Comparative study of hazelnut-shell biomass ash and metakaolin to improve the performance of alkali-activated concrete: A sustainable greener alternative. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 320, 126230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, F.; Mahpour, A.; Ahadi, M.R. Evaluation of energy consumption and CO2 emission reduction policies for urban transport with system dynamics approach. Environ. Model. Assess. 2020, 25, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Informal Conference of EU Ministers Responsible for Housing Declaration of the Ministers, Nice. 2022. Available online: https://www.iut.nu/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Informal-Housing-Ministers-meeting-2022-The-Nice-Declaration.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Simao, L.; Souza, M.T.; Ribeiro, M.J.; Montedo, O.R.K.; Hotza, D.; Novais, R.M.; Raupp-Pereira, F. Assessment of the recycling potential of stone processing plant wastes based on physicochemical features and market opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghane, N.; Mazinani, S.; Gharehaghaji, A.A. Comparing the performance of electrospun and cast nanocomposite film of polyamide-6 reinforced with multi-wall carbon nanotubes. J. Plast. Film Sheeting 2019, 35, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardoun, H.; Saliba, J.; Saiyouri, N. Evolution of acoustic emission activity throughout fine recycled aggregate earth concrete under compressive tests. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2022, 119, 103365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanbeigi, A.; Price, L.; Lin, E. Emerging energy-efficiency and CO2 emission-reduction technologies for cement and concrete production: A technical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 6220–6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samimi, K.; Estakhr, F.; Mahdikhani, M.; Moodi, F. Influence of Metakaolin and Cements Types on Compressive Strength and Transport Properties of Self-Consolidating Concrete. Int. J. Archit. Civ. Constr. Sci. 2018, 12, 243–249. [Google Scholar]

- Ashish, D.K. Concrete made with waste marble powder and supplementary cementitious material for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocelić, A.; Baričević, A.; Smrkić, M.F. Synergistic integration of waste fibres and supplementary cementitious materials to enhance sustainability of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC). Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, A.A.; Anaee, R.; Nasr, M.S. Enhancing the sustainability, mechanical and durability properties of recycled aggregate concrete using calcium-rich waste glass powder as a supplementary cementitious material: An experimental study and environmental assessment. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 44, 101985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado-Ramos, M.; Martí-Quijal, F.J.; Huertas-Alonso, A.J.; Sánchez-Verdú, M.P.; Barba, F.J.; Moreno, A. Almond hull biomass: Preliminary characterization and development of two alternative valorization routes by applying innovative and sustainable technologies. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 179, 114697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.; Dominici, F.; Luzi, F.; Jiménez, A.; Garrigós, M.C.; Torre, L.; Puglia, D. Effect of almond shell waste on physicochemical properties of polyester-based biocomposites. Polymers 2020, 12, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi, B.; Saidi, M.; Daoui, A.; Bellal, A.; Mechekak, A.; Toumi, K. The use of seashells as a fine aggregate (by sand substitution) in self-compacting mortar (SCM). Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 78, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arıcı, E.; Çelik, E.; Keleştemur, O. A performance evaluation of polypropylene fiber-reinforced mortars containing corn cob ash exposed to high temperature using the Taguchi and Taguchi-based Grey Relational Analysis methods. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 297, 123792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Ruan, S.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Yang, J.; Mechtcherine, V.; Tsang, D.C.W. Biochar-augmented carbon-negative concrete. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanyildizi, H.; Kina, C.; Acik, V. Macro-micro-nano and mechanical characteristics of cement clinker-gypsum-slag-based hybrid geopolymer mortars: A novel approach for reducing the cost and carbon footprint. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 112, 113933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Guo, B.; Yang, J.; Shen, Z.; Hou, D.; Ok, Y.S.; Poon, C.S. Biochar as green additives in cement-based composites with carbon dioxide curing. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, S. Investigation study data to develop sustainable concrete mix using waste materials as constituents. Data Br. 2024, 52, 109837. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, V.R.; Parthasarathy, K.; Kumar, D.P.; Dwivedi, Y.D.; Sathish, T. Evaluation of the mechanical strength of mortars with almond shell ash. Mater. Today Proc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cemalgil, S.; Onat, O.; Tanaydın, M.K.; Etli, S. Effect of waste textile dye adsorbed almond shell on self compacting mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 300, 123978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kina, C.; Tanyildizi, H.; Acik, V. Hybrid portland cement-slag-based geopolymer mortar: Strength, microstructural and environmental assessment. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 195, 106771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomatis, M.; Jeswani, H.K.; Stamford, L.; Azapagic, A. Assessing the environmental sustainability of an emerging energy technology: Solar thermal calcination for cement production. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 742, 140510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TS EN 197-1; Cement—Part 1: General Cements, Composition, Composition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria, Pervious Concrete Pavements. 2012. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/chapter/edited-volume/pii/B9780443217043000073 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- El Mashad, H.M.; Edalati, A.; Zhang, R.; Jenkins, B.M. Production and characterization of biochar from almond shells. Clean Technol. 2022, 4, 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.H.; Mo, K.H.; El-Hassan, H. Biochar waste biomass in pervious concrete. In Pervious Concrete Pavements; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 113–131. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, T. Evaluation of the Use of Waste Almond Shell Ash in Concrete: Mechanical and Environmental Properties. Buildings 2025, 15, 3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, T.; Alyamaç, K.E. Development of Numerical Models to Predict the Compressive Strength of High Strength Concretes Based on Maturity Method. Fırat Univ. Mühendislik Bilim. Derg. 2025, 37, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutsos, M.; Kanavaris, F.; Hatzitheodorou, A. Critical analysis of strength estimates from maturity functions. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2018, 9, e00183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Grazia, M.T.; Sanchez, L.F.M.; De Souza, D.J.; Ismail, L.; Noel, M.; Decarufel, S. Evaluation of electrical resistivity and maturity for estimating the early-age properties of pre-packaged concrete. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2022, 49, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belykh, I.; Sopov, V.; Butska, L.; Pershina, L.; Makarenko, O. Predicting the strength and maturity of hardening concrete. In Proceedings of the MATEC Web of Conferences, Chengdu, China, 13–15 April 2018; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2018; Volume 230, p. 3001. [Google Scholar]

- Soutsos, M.; Kanavaris, F. Applicability of the Modified Nurse-Saul (MNS) maturity function for estimating the effect of temperature on the compressive strength of GGBS concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 381, 131250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.-S.; Cho, Y.-H. Comparison between nurse-saul and arrhenius equations. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2009, 36, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C1074 1074-11; Standard Practice for Estimating Concrete Strength by the Maturity Method. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2011.

- Liu, W.; Li, K.; Xu, S. Utilizing bamboo biochar in cement mortar as a bio-modifier to improve the compressive strength and crack-resistance fracture ability. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 327, 126917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakeem, I.Y.; Alharthai, M.; Amin, M.; Zeyad, A.M.; Tayeh, B.A.; Agwa, I.S. Properties of sustainable high-strength concrete containing large quantities of industrial wastes, nanosilica and recycled aggregates. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 7444–7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uliasz-Bocheńczyk, A.; Mokrzycki, E. The use of waste in cement production in Poland–the move towards sustainable development. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. 2022, 38, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awachat, P.; Dakre, V.; Charkha, P.; Vundela, S.R. Robust Analysis of Various Measurement Uncertainty Parameters in Rebound Hammer Test. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 16, 2560–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkish cement and Cembureau. 2050 Targets and the Role of Secondary Materials; Turkish cement and Cembureau: Istanbul, Turkey, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, I.; Kumar, R. Effect of silica fume and PCE-HPMC on LC3 mortar: Microstructure, statistical optimization and life cycle Assessment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 403, 133073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Yeo, B.-L.; Markandeya, A.; Martínez, A.; Harvey, J.; Miller, S.A.; Nassiri, S. Transforming almond shell waste into high-value activators for low-carbon concrete: Life cycle assessment and technoeconomic analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 105, 112547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, W.; Guo, Y.; Dong, W.; Castel, A.; Wang, K. Biochar-cement concrete toward decarbonisation and sustainability for construction: Characteristic, performance and perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419, 138219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-S.; Wang, X.-Y. Multi-characterizations of the hydration, microstructure, and mechanical properties of a biochar–limestone calcined clay cement (LC3) mixture. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 3691–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakara, E.H.; Sevim, Ö.; Demir, İ.; Günel, G. Effect of waste concrete powder on slag-based sustainable geopolymer composite mortars. Chall. J. Concr. Res. Lett. 2022, 13, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owaid, H.M.; Hamid, R.B.; Taha, M.R. Variation of ultrasonic pulse velocity of multiple-blended binders concretes incorporating thermally activated alum sludge ash. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2017, 21, 1235–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematzadeh, M.; Poorhosein, R. Estimating properties of reactive powder concrete containing hybrid fibers using UPV. Comput. Concr 2017, 20, 491–502. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Nehdi, M.L. Prediction of concrete strength considering thermal damage using a modified strength-maturity model. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tareen, N.; Kim, J.; Kim, W.-K.; Park, S. Comparative analysis and strength estimation of fresh concrete based on ultrasonic wave propagation and maturity using smart temperature and PZT sensors. Micromachines 2019, 10, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekle, B.H.; Al-Deen, S.; Anwar-Us-Saadat, M.; Willans, N.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, C.K. Use of maturity method to estimate early age compressive strength of slab in cold weather. Struct. Concr. 2022, 23, 1176–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandhini, K.; Karthikeyan, J. The early-age prediction of concrete strength using maturity models: A review. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 2021, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, N.; Alcivar-Bastidas, S.; Irfan-ul-Hassan, M.; Petroche, D.M.; Qazi, A.U.; Ramirez, A.D. Concrete incorporating supplementary cementitious materials: Temporal evolution of compressive strength and environmental life cycle assessment. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleştemur, O.; Arıcı, E. Analysis of some engineering properties of mortars containing steel scale using Taguchi based grey method. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 29, 101015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, R.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Shui, Z. Evaluation and optimization of Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC) subjected to harsh ocean environment: Towards an application of Layered Double Hydroxides (LDHs). Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 177, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, M.; Alanazi, H.; Ibrahim, Y.E.; Abdellatief, M. Mechanical, microstructural characteristics and sustainability analysis of concrete incorporating date palm ash and eggshell powder as ternary blends cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.H.A.; Chileno, N.G.C.; Toledo Filho, R.D. Normal-and High-Strength Concretes with Eco-Efficient Cementitious Materials: Proportioning and Evaluation of Physical, Mechanical, and Durability Properties. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.