Abstract

As a museum constructed atop postwar ruins, Peter Zumthor’s Kolumba Museum in Cologne exemplifies a reconciliatory approach to integrating new architecture with historical remains. The current Kolumba Museum embodies multiple historical layers—those of medieval Gothic, wartime destruction, and the modern present—coexisting within a single architectural continuum. This study analyzes how the symbolic terms “inclusivity” and “temporal reconciliation,” directly articulated by Zumthor himself, are embodied in the physical design and in the way it is experienced. More specifically, the study explores how Zumthor’s design incorporates past structures, spatial sequences, and sensory experience to create continuity between historical memory and contemporary use. By examining form, sensation, and movement, this study offers a comprehensive analysis of how architectural design mediates between preservation and transformation. That is, architectural heritage is not merely confined to a fixed structure from the past but is substantively transformed into a medium of contemporary experience, thereby reinforcing its value as a sustainable cultural narrative. Accordingly, this study highlights the broad potential embedded in contemporary urban regeneration efforts, emphasizing the value and role of proactive design methodologies that go beyond static, unaltered preservation to incorporate architectural reinterpretation.

1. Introduction

The way architecture reveals the passage of time is complex and multifaceted. Notably, contemporary structures that utilize remnants of heritage directly encapsulate temporal traces. The determination of how to preserve and expose these traces, in terms of both scale and method, requires a meticulous process. The balance between the old and new is achieved by integrating historical material elements with newly introduced structures. Such integration operates across construction, spatial continuity, and experiential engagement, supporting the enduring reinterpretation of cultural heritage [1]. Transforming cultural heritage into a sustainable modern facility—defined here as a site that actively engages with the present through visual, spatial, and sensory interaction—rather than merely reproducing it, allows the value of cultural heritage to be meaningfully embedded in the everyday experiences of urban residents [2,3]. Consequently, careful observation and analysis of the interaction or integration process between the old and new are essential for enhancing the long-term relevance and value of heritage. A thorough examination of the architectural messages conveyed to individuals within an urban context contributes to the diverse utilization of the historical value of heritage [4]. Moreover, architectural works that present these messages not as a simple binary distinction but as a sophisticated composition of a diverse temporal spectrum contribute to strengthening the cultural longevity of heritage value [5]. This study focuses on the Kolumba Museum, which dramatically showcases the combination of such a diverse time spectrum, to derive its design methodology and broader implications [6]. Recent discourse increasingly situates such questions within evolving debates on how heritage and contemporary intervention can coexist, rather than oppose one another.

Recent research into historic building intervention has expanded significantly beyond conventional preservation-focused approaches, positioning adaptive reuse as a central framework in contemporary architectural discourse. Rather than treating heritage as a static artifact to be maintained unchanged, current scholarship emphasizes intervention as a negotiated process between past fabric and present needs, where architectural value emerges through the interaction of material, spatial, and experiential dimensions [7,8]. Systematic reviews in the field demonstrate that successful adaptive reuse projects require the integration of technical, functional, cultural, and sensory considerations—framing reuse as a multidimensional design methodology rather than a purely technical act of conservation [9,10]. This perspective aligns with expanding discussions on the potential of embodied experience and sensory perception to drive heritage appreciation, suggesting that architectural heritage should be understood not only through material authenticity but also through experiential authenticity, which links physical remnants with perceptual and emotional meaning [11,12]. Such research reflects a broader disciplinary shift that evaluates the relationship between old and new through phenomenological experience and user perception of layered time rather than through static preservation norms. Accordingly, positioning the present study within this developing trajectory provides the theoretical basis necessary to examine how contemporary architecture can integrate historical remains through spatial, sensory, and cognitive engagement.

Within this academic trajectory, international heritage doctrine has developed influential frameworks for classifying how historical structures may be engaged through contemporary intervention. Foundational documents such as the Venice Charter (1964) and the Nara Document on Authenticity (1994) articulate principles for safeguarding material integrity and cultural significance, distinguishing carefully between different degrees and types of intervention [13,14,15]. Building on these charters, conservation theorists and ICOMOS guidelines further clarify categories such as consolidation, restoration, reconstruction, anastylosis, and adaptive reuse, each defined by specific ethical obligations concerning authenticity, reversibility, and the legibility of new work [15,16,17]. Consolidation stabilizes existing fabric to prevent further decay; restoration seeks to reveal a prior state without conjectural addition; reconstruction permits the re-creation of lost elements only when supported by reliable evidence; and anastylosis involves reassembling displaced original fragments in their documented positions. By contrast, adaptive reuse extends beyond strict conservation to reinterpret and reprogram heritage structures for contemporary use, while maintaining critical respect for historical substance and context [18,19]. More recent discussions additionally highlight practical built precedents that demonstrate how contemporary architecture may integrate new structures with archeological remains. Examples such as David Chipperfield’s Neues Museum in Berlin, Rafael Moneo’s Murcia Town Hall, and Caruso St John’s interventions at Tate Britain illustrate differentiated approaches to layering contemporary interventions upon historic fabric without fictionalizing the past. These precedents clarify that integration requires rigorously articulated principles rather than intuitive esthetic gestures, and they contextualize the present study within established contemporary discourse. Together, these frameworks provide a normative basis for distinguishing between interventions that maintain the integrity of archeological remains and those that risk fictionalizing or aestheticizing the past, and they offer essential criteria for evaluating projects that integrate in situ ruins within new architectural configurations.

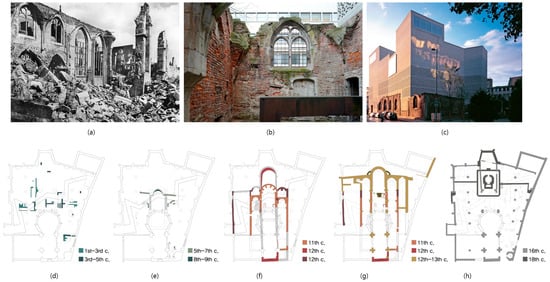

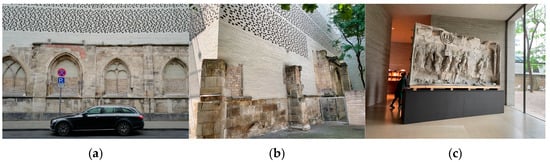

These doctrinal distinctions become clearer when considered alongside built precedents that negotiate preservation and transformation in different ways. Building on this, contemporary projects demonstrate that the architectural value of ruins can be extended in a variety of ways [20]. Architectural interventions that incorporate new spatial programs into existing remnants manifest diverse typologies. Representative examples include the Acropolis Museum in Athens [21] (Figure 1a), Castelvecchio in Verona (Figure 1b), and the Harvard Art Museum in Boston (Figure 1c), all of which have restructured exhibition facilities upon archeological remains that symbolize historical epochs. These cases share a common interest in negotiating between preservation and transformation; however, the strategies and attitudes through which this balance is achieved differ notably. The Acropolis Museum, for instance, adopts a method of preserving the remains in their most original and unaltered condition, with new structures layered horizontally above the excavated site. This approach maximizes the authenticity of the ruins, avoiding any selective modification or reinterpretation. It exemplifies a horizontally stratified and stacked composition, where historical periods remain clear and discrete. In contrast, Castelvecchio and the Harvard Art Museum preserve the original structural frames not only functionally but also formally, maintaining the historic façades in their visible integrity. These examples retain the vertical structures and skins of earlier times, while introducing selective modifications—such as variations in material textures within courtyards or subtle reinterpretations at points of architectural junction [5]. Such interventions represent localized and partial transformations within the broader preservation framework [22]. From a functional perspective, the Acropolis Museum treats archeological remains as objects of viewing rather than occupation, maintaining strict spatial detachment through controlled circulation systems and transparent flooring [23,24]. Castelvecchio and the Harvard Art Museum instead merge contemporary functional adaptability with historical envelopes, supporting programmatic flexibility and curatorial variation [25,26]. Esthetically, the Acropolis emphasizes a calm stratified reading of time, while Castelvecchio utilizes scenographic contrast and abrupt junctions, and Harvard foregrounds sensory immersion through controlled daylight mediation [27,28]. These distinctions demonstrate how heritage settings produce fundamentally different experiential atmospheres and establish analytical ground for interpreting the Kolumba Museum not as a variation within these approaches but as a phenomenological field that activates memory through layered temporality [29,30]. Accordingly, these precedents clarify what is at stake in contemporary heritage intervention and position the Kolumba Museum as a case that reconfigures this discourse through a unique mode of spatial, sensory, and cognitive synthesis.

Figure 1.

(a) The Acropolis Museum, Athens; (b) Castelvecchio Museum, Verona; (c) Harvard Art Museum, Boston (Figure credit: Author).

The Kolumba Museum, by contrast, was conceived in a context where the former Gothic structure had lost its functional capacity. As a result, both the fragments and the whole are reinterpreted through a new architectural language. Vertical and horizontal elements create rhythm through small and large void spaces at various points, forming a cohesive structure. What distinguishes the Kolumba Museum is its unique atmosphere, where old and new are neither clearly divided nor sequentially layered. Progression across historical moments is neither linear nor unidirectional [4]; rather, past and present reverse and interweave, generating a cyclical sense of historical recurrence that departs from conventional museological approaches [20]. The multiplicity and intermingling of time layers result in a blended experience that is distinct from more didactic or stratified presentations of heritage [5]. This study analyzes the compositional elements of such layered temporal experience from a chronological perspective, identifying how these differentiated chronological strata contribute to a broader architectural message. In doing so, it demonstrates that the value of heritage is not confined to a static condition of the past, but is actively integrated into contemporary architectural experience, thereby extending its relevance and sustainability in the present [5].

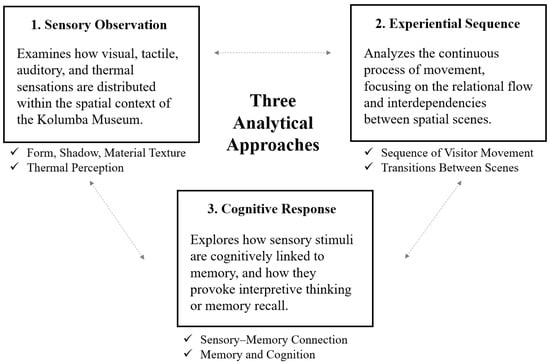

Peter Zumthor’s Kolumba Museum (Figure 2) overlays a contemporary art museum on the historical remnants of the Gothic cathedral in Cologne [29]. It preserves layers of time from the Middle Ages and Renaissance, along with remnants of World War II, upon which a modern structure is superimposed. It holds representative significance in analyzing time layers, and exemplifies heritage value by offering experiences that transcend the past and present. The 2002 international design competition by the Archdiocese of Cologne aimed to integrate a church and art museum. Since the building would be constructed atop historical ruins, the Archdiocese emphasized harmonious fusion of history and modern architecture [3,30]. This fusion presents a new approach for experiencing past architectural contexts. This study highlights Zumthor’s unique unfolding method, which surpasses conventional sequential exposure of ruins by offering a multilayered experience.

Figure 2.

(a) The war-damaged Kolumba Museum; (b) Remaining Gothic window; (c) Overall view of Kolumba Museum; (d–h) The architectural transformation of the Kolumba Museum through the Roman, Romanesque, and Gothic periods (Figure credit (a–c): [31], (d–h): redrawn by the author, based on the original source [32].

The museum covers multiple historical periods. As Zumthor quoted, “The combination of 2000 years of history, Roman excavations, Romanesque and Gothic churches, the heaps of rubble after World War II, and the chapel from the 1950s as the symbol of the new beginning” [30], highlight the complexity and richness of Kolumba. The design process for the new museum to be erected on these historical layers commenced in 2002 and was completed in 2007. An international competition was conducted with renowned architects worldwide that evaluated various criteria, such as artistic creativity, technical excellence, harmony with historical ruins, and consideration of user experience. Subsequently, Zumthor’s design was adopted and construction began in 2003, with the Kolumba Museum opening its doors in 2007. Serving as a connection between the past and the present, the Kolumba Museum, enriched by Zumthor’s architectural concepts, provides a sustainable solution for experiencing the value of heritage. This study examines the architectural strategies that contribute to balancing historical continuity and contemporary spatial intervention. Through analysis of the Kolumba Museum, it investigates how these strategies enhance the perceived value of heritage by fostering a sustained dialog between the past and present across physical, sensory, and cognitive dimensions [4,33]. While previous studies on sustainable heritage have largely focused on conservation techniques and methodologies for preserving historic fabric [3], fewer have explored the spatial and experiential mechanisms through which temporal heterogeneity is perceived and restructured in architectural design [34]. This study seeks to address this gap through an in-depth spatial analysis of the Kolumba Museum, positioning it as a case that exemplifies such integrative design approaches. This study proceeds from the premise that the interpretation of spatial experience necessarily entails phenomenological and perceptual dimensions, and therefore grounds its analysis in a direct engagement with primary sources. To avoid leaving concepts such as “inclusivity,” “temporal reconciliation,” and “harmonious coexistence” in the realm of abstract generalities, their scope and operational meaning are delineated through Zumthor’s own descriptions of the Kolumba project. As Zumthor states, “The new underlying building idea is conciliatory and integrative… It takes in the old, bearing it within” [35] (p. 139). This articulation provides the textual foundation for understanding inclusivity not as a metaphorical label, but as an architectural principle through which the new structure receives, absorbs, and safeguards the historical layers embedded in the site. Similarly, Zumthor’s material account deepens the definition of temporal reconciliation. His observation that “the presence of the building corpus growing out of the old foundations seems consistent and harmonious” [35] (p. 141) positions reconciliation as a spatial and material condition in which historical ruptures are neither concealed nor dramatized, but allowed to coexist within a unified architectural whole. Within this clarified framework, harmonious coexistence emerges as an experiential effect generated by tectonic continuity, material transitions, and circulation sequences that guide visitors through layered remnants without imposing a singular historical narrative. By situating the Kolumba Museum within this conceptual and methodological structure, the study offers a more precise account of how contemporary intervention can activate the cultural and temporal depth of a heritage environment. These direct references also distinguish Zumthor’s own conceptual vocabulary from the author’s interpretive extensions, thereby enhancing the methodological transparency required for an experiential analysis of architectural heritage.

2. Methodology

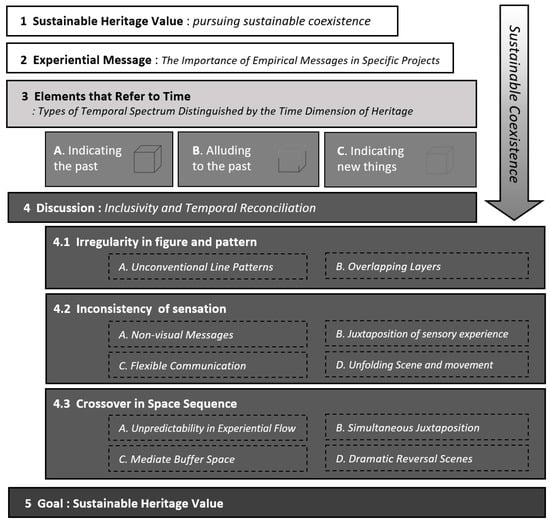

Building upon the conceptual and heritage-related discourse established in Section 1, this section clarifies the methodological framework through which the Kolumba Museum is examined. The research adopts a qualitative and interpretive methodological orientation, with the methodology structured around three analytical approaches, as illustrated in Figure 3 This framework—comprising Sensory Observation, Experiential Sequence, and Cognitive Response—is developed in alignment with established architectural research strategies [3]. It is a literature-based theoretical construct designed to analyze the distinct stratification of temporality embodied in the Kolumba Museum. As a theoretical and interpretive study, it does not incorporate direct empirical methods such as visitor group interviews, group-based discussions, or sensor-based tracking. Rather, it seeks to generate qualitative and conceptual insights by connecting Zumthor’s own design statements with relevant theoretical literature. Zumthor emphasizes that architectural experience is constructed through sensory perception rather than visual information alone, foregrounding the bodily, atmospheric, and emotional dimensions of spatial encounters [36]. In this sense, the study positions itself as a theoretically grounded interpretative inquiry that establishes the foundation for more empirically supported research in future phases, rather than claiming immediate empirical generalizability. During a research stay in Cologne in the summer of 2023, the author conducted multiple site visits to the Kolumba Museum to closely examine the spatial and sensory aspects of the architecture. All photographs credited to the author in this paper were taken during these visits as part of the academic investigation. This qualitative and interpretive orientation parallels methodological choices in recent adaptive reuse research, which similarly rely on precedent analysis and phenomenological reading of spatial experience to understand how heritage settings operate in use [7,8,9,10]. It also accords with established guidance on historic-preservation and architectural research methods, which emphasize close observation, iterative site visits, and theory-informed interpretation as valid means of investigating complex heritage environments [23,24,27].

Figure 3.

Three Analytical Approaches in the Study of Kolumba Museum (Figure credit: Author).

This analytical framework consists of three complementary approaches. The first is a primary, sensory-based approach that examines how bodily sensations are distributed throughout the Kolumba Museum. This includes visual perception of form, the experience of light and temperature, auditory stimuli, and tactile engagement with textures [37]. This initial mode of analysis is primarily grounded in direct observation of spatial configurations and discrete scenes [34]. The second approach shifts focus toward the experiential process of navigating the museum. Whereas the first approach addresses individual, scattered moments of sensory perception, this second perspective analyzes the continuity of experience—viewing the act of visiting as a sequential movement and examining the interdependent effects and feedback that arise throughout this progression [38]. The third and final approach engages with cognitive response. Here, the analysis turns to how specific sensory stimuli are cognitively translated into memory, and how such stimuli later elicit recollective or interpretive responses [4]. By delineating these memory-linked cognitive processes, this approach aims to reveal how the Kolumba Museum’s distinctive treatment of heritage operates as a holistic and generative mode of engagement [33,38].

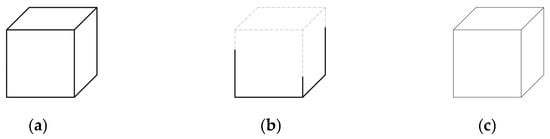

Taken together, these three approaches resonate with museum and visitor-studies literature that conceptualizes meaning-making as a dialog between sensory stimulus, spatial movement, and memory formation [25,26], thereby providing a phenomenological basis for the subsequent analysis. Figure 4 schematically organizes this methodological structure as a five-step research flow. Level 1, “Sustainable Heritage Value,” identifies the overarching goal of articulating how Kolumba contributes to sustainable coexistence between past and present. Level 2, “Experiential Message,” summarizes the empirical architectural messages that emerge from specific spatial situations as interpreted through the three analytical approaches. Level 3, “Elements that Refer to Time,” groups architectural indicators into three temporal types: A, indicating the past through directly exposed remnants; B, alluding to the past through partial, layered, or implicit references; and C, indicating new things through wholly contemporary insertions that nevertheless remain in dialog with the ruins. Level 4, “Discussion: Inclusivity and Temporal Reconciliation,” is subdivided into Section 4.1, Section 4.2 and Section 4.3, which, respectively, address irregularity in figure and pattern, inconsistency of sensation, and crossover in space sequence; within each, subcategories A–D specify how different spatial and sensory configurations are thematically interpreted. Level 5, “Goal: Sustainable Heritage Value,” synthesizes these thematic discussions into a conceptual model that frames Kolumba’s architectural strategies as contributing to sustainable coexistence.

Figure 4.

Research flow (Figure credit: Author).

To achieve this, the flow of research unfolds as follows. As shown in the flowchart in Figure 4, Section 1 and Section 2 articulate the foundational discourse of the study, clarifying both the overall objective and the analytical perspectives that guide the inquiry. This step is essential in establishing the intent of the research and outlining how the unique value of the Kolumba Museum will be examined in detail [1]. Section 3 analyzes how architectural structures, as physical constructs, serve as indicators of time by classifying them into three representational types. Certain architectural elements express the past by exposing remnants in their raw form, while others convey present-day materiality through entirely new insertions. A third category occupies a middle ground, indirectly suggesting a specific temporal layer without explicit exposure. For example, there is a direct method of exposing the Gothic cathedral’s window frames as they are. In contrast, there are indirect methods where the remnants are not directly displayed but stimulate visual imagination, or even engage multiple senses through complex connections. Differentiation based on the periods they indicate, along with the various ways in which they indicate time [39], whether through direct specification or indirect implications, can result in diverse subjects and methods. This typological framework in Section 3 constitutes an effort to identify the temporal elements embedded in the Kolumba Museum through systematic classification and sensory observation. Section 4 builds upon this by analyzing how these elements intersect and interact across spatial, perceptual, and cognitive dimensions. Together, these sections form the methodological progression through which the study develops its central argument [40]. It examines the patterns at the boundaries where these elements meet, delving into the visual and non-visual characteristics of these boundaries in a multilayered manner. The multilayered distribution of time deviates from the traditional dichotomous museum exhibition methods. For instance, the layers of time are unpredictably overturned, with sudden intersections of light and shadow or the strategic emergence of visual elements that evoke specific memories, leading to an experience where past events and the visitor’s present self engage in a real-time dialog and fusion. This convergence represents the intersection of the study’s threefold methodology—sensory observation, experiential sequence, and cognitive response—unfolding within the spatial context of the museum. Through this exploration, Section 4 aims to reveal how Kolumba’s architectural strategies, grounded in ancient ruins, articulate a new design methodology for sustainable heritage. This analysis provides a comprehensive reading of the architect’s core concepts of integration and reconciliation [33].

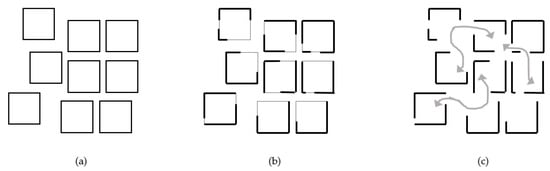

3. Results: Elements That Refer to Time

This section analyzes the elements dispersed throughout the Kolumba Museum, which serve as an indicator of historical continuity. For instance, architectural constituents, such as columns and walls employed in the construction of the edifice, symbolize the passage of time [41]. Furthermore, sporadic elements, such as specific materials, patterns, supplementary structures, statues, designated artifacts, and exhibition pieces, collectively epitomize individual historical periods [42]. Rather than classifying based on form and material, these elements are categorized into three types according to the time period in which they were constructed (Figure 5). The first type, depicted in Figure 5a with a bold, clear line, focuses solely on past structures in their entirety. The second type, shown in Figure 5b, represents situations where a combination of partially preserved past structures and supplementary surrounding structures stimulates new imaginative interpretations. This type is expressed through a combination of a bold line indicating the old, additional materials layered on top, and a faint dotted line representing the scope of imagination. The third and final type is a space composed entirely of new materials without the presence of any old structures, and is delineated by a thin solid line. The schematic in Figure 5 illustrates the temporal types that constitute the Kolumba Museum. This section examines the temporal devices intrinsic to Kolumba.

Figure 5.

Three elements indicating temporal status: (a) Original materials indicating the past; (b) Elements alluding to the past; (c) New elements indicating new materials (Figure credit: Author).

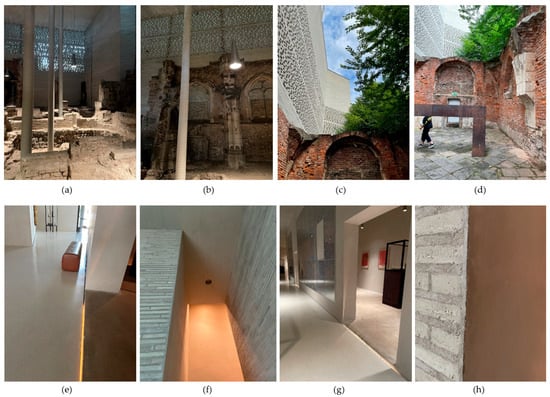

3.1. Elements Indicating the Past

The Kolumba Museum features devices dispersed both externally and internally that authentically reveal the past. For passersby near the museum, the remnants of the Romanesque and Gothic cathedral displayed on the museum’s exterior walls (Figure 6a,b) immediately convey a direct message about the past. Upon entering the museum, various sculptures and exhibits (Figure 6c) showcase the historical periods they encapsulate [43]. Furthermore, aged materials, such as bricks and stones within the museum, irrespective of their form and location, prompt observers to immediately contemplate the temporal dimensions of the past.

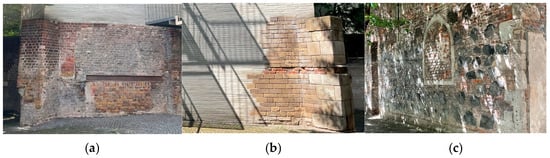

Figure 6.

Elements indicating the past in the Kolumba Museum: (a) Gothic pointed arches; (b) Remaining exterior wall; (c) Sculptures near the lobby area (Figure credit: Author).

In essence, the remnants within the museum serve as markers of elapsed time. These distinct indicators convey a message of time through the inherent nature of the materials used (Figure 7). The surfaces of weathered stone, cross sections of bricks, and worn wooden joints showcasing the erosion and decay of time all express the temporal dimensions of the past [41]. These indicators are clear without ambiguity, making them primary and direct indicators. While the internal composition of these direct indicators may harbor a detailed, layered chronological spectrum, they all unequivocally refer to things of antiquity, signifying the past [43]. Thus, the distinctiveness of these direct indicators from the categories discussed in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3 is evident in the explicit references to aged elements and the past.

Figure 7.

Materiality indicating the past: (a–c) Aging bricks and stones (Figure credit: Author).

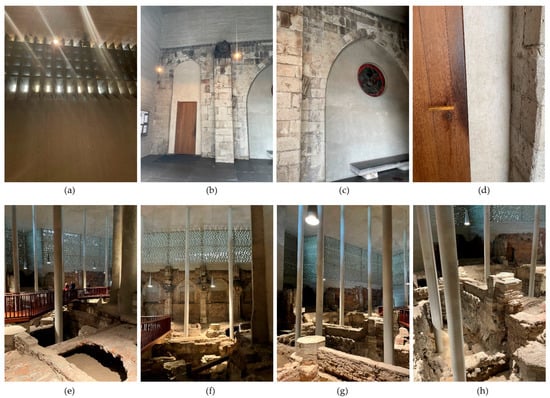

3.2. Elements Alluding to the Past

Implying the past does not mean that remnants of the past are preserved as they were; instead, they are replaced to enable interpretive perception of earlier spatial conditions through controlled exposure, a strategy consistent with recent discussions that emphasize non-reconstructive conservation and calibrated experiential engagement [7,10]. Such calibrated substitution avoids conjectural reconstruction while enabling visitors to infer the earlier spatial order without fictionalizing its material absence. Preservation in its unaltered state is not the objective; rather, an engaged relationship with past temporal epochs is sought through appropriate substitutions. For instance, Figure 8a, a window from 1952 that is not composed of the original material, fosters a more dynamic and interior-focused atmosphere [29]. Similarly, the entrance in Figure 8b,c, once a complete exterior entrance from the street, has been replaced with new materials and a new handle (Figure 8d), coexisting with transitional spaces characterized by a semi-external nature in terms of spatial relationships. Despite the addition of layers of semi-external spaces, the original memory [30], as a threshold for entering the sacred space, was staged dramatically.

Figure 8.

Elements alluding to the previous structure (a–h) (Figure credit: Author).

Even when entering the excavation room on the ground floor (Figure 8e–h), the functionality of such implications persists. Remnants of the past exposed in the lower part of the space indicate the previous structure, while the extended walls of new material above imply the former building’s presence through substitution rather than replication—employing entirely different surfaces and materials. Minimal spatial cues and material contrasts guide visitors to reconstruct the absent structure through individual spatial inference [4,33]. This represents a notable contrast with the approach described in Section 3.1, where the past is directly indicated through preserved remnants and original materials, leading to a more uniform experience among visitors. In contrast, the implicit cues in Section 3.2 invite diverse reconstructions by affording interpretive freedom to each visitor. The absence is thus reinterpreted differently by each visitor, enabling a broader experiential spectrum grounded in individual spatial inference. In the absence of most columns, the sporadically emerging vertical columns contribute to a newly created spatial experience with minimal presence.

3.3. Elements Indicating New Things

Along with the antiquities within Kolumba, clear instances of new elements were inserted into most museum spaces. Passing through Brückenstraße Street, where the remnants of the Gothic cathedral are prominent, and entering Kolumbastraße Street, one encounters gray walls (Figure 9a) constructed entirely of new materials. A sequence of entirely new elements follows, including doors, a lobby space, and foyer (corresponding to position one on the ground plan) facing a new courtyard (Figure 9b–d). This newly opened space features selected trees, specifically pruned branches, a newly crafted landscape, and various chairs that capture the surrounding urban scenery.

Figure 9.

Elements exhibiting novelty with new materials (a–h) (Figure credit: Author).

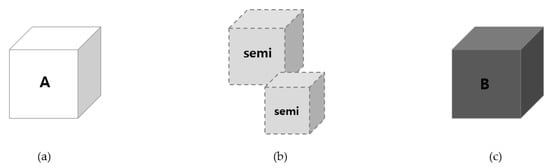

The various rooms scattered throughout the museum also exhibit novelty, each of which reflects a unique character. Most rooms are composed of a singular material, and the seams and furnishings are entirely unified with this newly chosen material, maximizing a sense of novelty (Figure 9e–g). This use of material uniformity reflects a strategy Zumthor frequently employs in his other museum projects, serving as an intuitive yet effective means of evoking spatial novelty. One such example is the Kunsthaus Bregenz (KUB) in Austria, where the restrained, square-shaped galleries (Figure 10a–c) are characterized by a heightened spatial coherence through the consistent use of a singular material palette (Figure 10d). This strong singular material characteristic commences from the locker room in front of the ticket booth and continues to encounter these strongly cohesive new rooms on each floor even after the start of the exhibition (e.g., the black room or mahogany room [30]). Additionally, the patterns newly created by Zumthor (Figure 9h) and the newly installed structures that did not exist previously contribute to this overt sense of newness. Such conspicuous novelty can create contextual contrasts of mere juxtaposition or concealment. Unlike examples where newness is composed in isolation—standing apart as its own esthetic (Figure 10a–d)—its juxtaposition with historical remnants in Kolumba accentuates the message of the new. In this regard, the museum demonstrates a distinctive design strategy that sets it apart from Zumthor’s other works. In Section 4, we closely examine how the heterogeneous elements in Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 3.3, as expressed by Zumthor, were arranged and deployed to create the reconciliatory atmosphere he envisioned.

Figure 10.

Kunsthaus Bregenz (KUB), Peter Zumthor, 1997 (a–d) [44].

4. Discussion: Inclusivity and Temporal Reconciliation

Before examining the interrelations among individual elements, it is necessary to clarify the analytical standpoint that supports the interpretations developed in this section. Recent discussions in adaptive reuse research emphasize that the experiential and cognitive dimensions of architectural settings play a decisive role in understanding how heritage environments operate in practice, particularly when historical layers intersect with contemporary spatial frameworks [7,9,25]. Within this context, the three methodological approaches outlined in Section 2—Sensory Observation, Experiential Sequence, and Cognitive Response—serve as complementary lenses for interpreting the layered spatial and perceptual situations encountered in Kolumba, a relationship schematically articulated in Figure 11 as the interpretive progression from categories A to B to C. Within this clarified analytical stance, the interpretive approach necessarily involves acknowledging the situated nature of architectural experience. The interpretations developed in this section, grounded in a phenomenological and interpretive perspective, do not seek absolute universality but offer a methodologically supported viewpoint shaped by the analytical framework of this study [7,9]. Variations in observer sensitivity, cultural background, and temporal conditions of encounter inevitably influence how architectural settings are perceived, and prior research on Kolumba similarly notes that changes in light, material atmosphere, and seasonal conditions contribute to the museum’s experiential character [45,46]. In this respect, the analyses that follow should be understood as one informed and analytically grounded reading, enabled by the methodological structure established earlier.

Against this background, Section 4 examines how temporal indicators identified in Section 3 converge at points of spatial intersection, and how these intersections generate moments of irregularity, incongruity, and crossover that influence sensory distribution, experiential continuity, and memory formation. Section 4 analyzes the relationships among individual elements, building upon Section 3’s separate examination of their situational status. As illustrated in Figure 11, Section 4 focuses on the characteristics of boundaries at points of intersection, where the elements of time distributed throughout Kolumba interact with surrounding elements. Here, the three methodological approaches outlined in Section 2 are actively applied [34]. As shown in Figure 11, Section 4.1 analyzes Physical Irregularity and Skin Perception, an investigation situated at the intersection of sensory and perceptual dimensions [33]. Section 4.2 highlights the incongruity between visual and non-visual elements that permeate the Kolumba Museum. This too engages both sensory and perceptual domains and serves as a key device in shaping the museum’s distinctive atmosphere, offering meaningful stimuli throughout the spatial experience [33]. Section 4.3 examines inconsistency in the flow of experience as revealed in the spatial sequence. This section explores a comprehensive cognitive perspective. The hierarchy of these subsections within Section 4 is equivalent, with each interacting cyclically with the others.

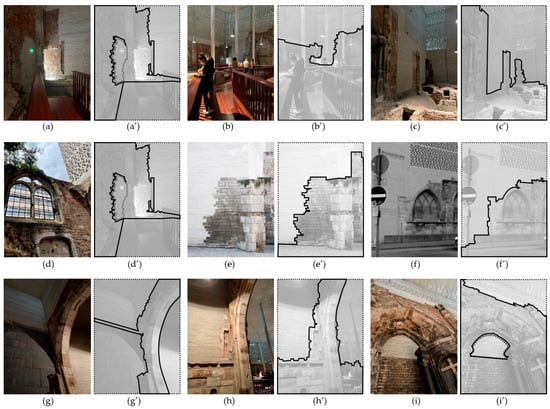

4.1. Irregularity in Figures and Patterns

Junctures at which temporally dispersed elements within the Kolumba physically converge display notable irregularities. Specifically, the point where the remnants of a medieval Gothic cathedral intersect with materials from a new 21st-century art museum stands out as the most direct site of encounter between the old and new. The treatment of this boundary serves as a vivid manifestation of the architectural standpoint of how a museum grapples with the dimension of time, thus becoming integral to its identity [30]. The characteristics of these points are shown in Figure 11. This approach retains the originality of historical traces without introducing artificial lines or joints when juxtaposed with new materials. This results in the organic emergence of diverse, irregular forms that seamlessly intertwine ancient and contemporary times. Such a pattern is consistently observed within the museum’s interior (Figure 12a–c,a′–c′ when observing its exterior from the city (Figure 12d–f,d′–f′) and at intersections between structures (Figure 12g–i,g′–i′), rather than solely on wall surfaces.

Figure 12.

The boundary point where past time (thick line) and new time (dots) meet: (a–c,a′–c′) Lines on the indoor walls; (d–f,d′–f′) Boundary lines on the exterior walls; (g–i,g′–i′) Lines on the structures. (Figure credit: Author).

These irregular boundary conditions are not incidental visual outcomes but constitute a primary mechanism through which Kolumba stages the encounter between temporal layers. At these sites, the viewer perceives the discontinuities between past and present not as abstract historical information but as embodied spatial experiences. Accordingly, the irregularities become interpretive cues that activate perceptual tension, making them central to the analytical category of “irregularity” within this study. The incongruity in these lines transcends the mere discussion of shapes; it significantly affects the perception of surfaces or skins adorned with such patterns. In instances of skin comprising irregular patterns, the tendency to generate arbitrary openings and converge midpoints of the skin introduces the form of a dissonant boundary [30]. As shown in the diagram below, the conventional boundary (Figure 13a) can exhibit irregular shapes and layouts. This is not simply a matter of pattern configuration, but rather, it has a powerful impact as it extends from the variables of the boundary surface’s opening and closing, which is perceived as a boundary rather than a pattern. Through the variables of this incongruity (Figure 13b,c), previously closed, distinct layers overlap, resulting in a new perception of boundaries. Such tendencies are further accentuated in the discussions on sensory irregularities in Section 4.2 and the irregularities intervening in the spatial sequence in Section 4.3.

Figure 13.

(a) Conventional and rigid division; (b,c) Boundary perceptions through overlapping layers. (Figure credit: Author).

4.2. Inconsistency of Sensation

Beyond visual messages, non-visual messages have also played a significant role in shaping the distinctiveness of the Kolumba Museum. Visitors encounter new situations in terms of auditory stimuli, changes in temperature, and perceptions of perspective, surpassing the conventional sensory experiences that follow visual devices. This dynamic experience enlivens the various temporal layers distributed throughout the museum, allowing for a more vivid and immediate understanding of the intersections of time. Rather than following a sequential or gradual unidirectional flow, the unpredictability introduced through sensory guidance sometimes generates diverse tensions in the direction of time perception during a museum visit.

The incongruity between visual and nonvisual elements stimulates novel cognitive interactions. For instance, at the ground level in the excavation room (Figure 14a,b), sunlight permeates through small openings in the outer walls, accompanied by ambient noise from the surrounding city. However, with the lower wall blocking the view toward the periphery, auditory interaction with the fully exposed external environment occurs exclusively, overlapping the auditory messages of the present with the visual messages of the past [33,47]. This juxtaposition of disparate sensory experiences across two distinct temporal layers enriches museum visits as flexible and communicative encounters. In other words, the traditional dichotomy between the distant past and the new present is sensorially broken and understood as a flexible interaction [48]. Visitors simultaneously perceive the unmistakably present sounds of the surrounding modern city and the clearly evident Gothic walls. Through this, they can fully grasp the museum’s unique identity as a Gothic cathedral adorned in the new attire of the 21st century, engaging with it through sight, sound, touch, and resonance. The rigidity of the traditional dichotomy is shattered, allowing visitors to vividly experience a sustainable message that resonates not only in the past, but also in the present. This phenomenon similarly extends to the Former Vestry exhibition space (Figure 14c,d) at the same level [49]. While enclosed walls obscure the peripheral view of the city, a fully open sky and ambient city sounds create a distinct sense of the present. Simultaneously, the focus on the central object, combined with the messages of the artwork, surrounding Gothic walls, and contemporary movement beyond, generate a novel sensory perception of this specific location. This transcends the conventional rigid sense of dichotomized separation [50], fostering a continuous sensory experience that maximizes sustainable contemporary values by appreciating heritage and art.

Figure 14.

The ground level in the excavation room (a,b), the Former Vestry exhibition space (c,d) and distinguished surfaces and structures (e–h) (Figure credit: Author).

The Kolumba Museum rejects rigidity and corpulence, aligning with the attitude demonstrated by Zumthor in various projects. In the case of Kolumba, amid scenes that transcend time, Zumthor’s characteristic fragmentation gestures depart from the typical pattern of recognizing structures, allowing for more individualized navigation and perception of each element. The conventional sense [51] of a consolidated entity perceived as a single volume is challenged by Zumthor’s method of distinguishing surfaces and structures (Figure 14e–h), which emphasizes individuality and encourages a renewed perception and stimulation of the unfolding scene. This additional sensory effect flexibly controls the intensity with which parts of the space are read as conglomerates, enhancing the three-dimensional quality [51].

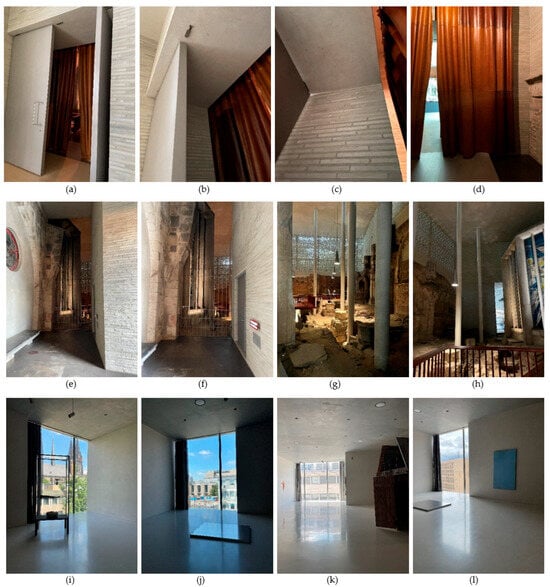

4.3. Crossover in Space Sequence: Unpredictability in Experiential Flow

The discussions in Section 4.1 and Section 4.2 centered around the viewers’ perspectives and the events unfolding in the surrounding context. Section 4.3 analyzes the rhythm occurring in the before-and-after relationships when viewed continuously from the initiation to conclusion of the visit. Through this, we can comprehend the unique design concept of fusion permeating the entirety of the museum, which Zumthor refers to as the space of reconciliation in Kolumba. This is a core aspect of understanding its distinctive identity.

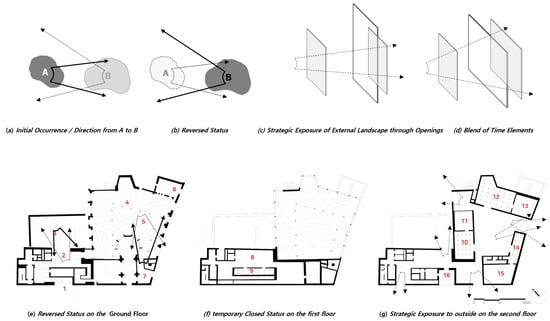

The Kolumba Museum does not provide a designated unidirectional chronological flow in the exhibition path; instead, it reveals a fluctuating time-related spectrum based on location and direction. Experiential messages that repeatedly traverse [52] the past and present, blurring the distinction between them, create a simultaneous and seamless juxtaposition without rigid boundaries. The direct and simple presentation of Gothic cathedral walls exposed using this approach represents a direct connection to the ancient past. Subsequently, the wooden elements in the ticket room and cloakroom provide the sensation of being entirely enveloped in the new materials. Following the wooden space, entirely new trees and landscapes are viewed through the courtyard alongside the adjacent Gothic walls.

The excavation approach presents an intriguing sequence. If the reversals and intersections mentioned above are attributes realized through changes in the sequence of two different properties (Figure 15a,c), the intervention of an intermediate element inserted within the Kolumba Museum (Figure 15b) makes this flow of reversal and intersection more rhythmic and subdivided, creating a much more layered spectrum. For instance, introducing a semi-exhibition space as a buffer zone between the hall and exhibition space (Figure 16a–d) serves as an intermediate layer where lighting and color gradually change. Heavy leather curtains mediate sudden shifts in temperature and auditory stimuli. The insertion of an ambiguous layer between past and present, which is both present and past, contributes to a more nuanced blending and merging of the two temporal layers.

Figure 15.

Relationship between a Semi-Space and Two Concurrent Properties. (a) Primary space (Property A); (b) Intermediate semi-space/buffer layer mediating A–B; (c) Primary space (Property B) (Figure credit: Author).

Figure 16.

Spatial transitions generating unpredictability in experiential flow. (a–d) Intermediate buffer spaces between hall and exhibition areas. (e–h) Visual–physical reversals at the excavation boundary. (i–l) Window openings articulating the sudden presence of the contemporary city. (Figure credit: Author).

In addition to the passage of time, the reversal of accessibility to heterogeneous messages during the visiting process becomes a captivating catalyst for perceiving museum spaces. An opening on the right side of the vestibule (Figure 16e–h) when entering the chapel space in the 1950s revealed a view of the excavation room. Although visible, they are inaccessible. The subsequent complete reversal of this relationship (Figure 17a,b,e) compels visitors to be present in the excavation room where they cannot go, creating a dramatic scene in which the intersection of the past and present is emphasized.

Figure 17.

Unpredictability in Experiential Flow (a,b) Directional shift and reversal between spatial conditions; (c,d) Strategic exposure through openings; (e–g) Floor plans of the Kolumba Museum; (Figure credit: (a–d) Author; (e–g) redrawn by the author based on [29]).

An intriguing aspect is that this reversal operates in tandem with the act of indicating time. From the present location, clearly framed by new materials, visitors gaze across at the ancient remains—but the path offers no access to the far side. However, as the sequence of the visit progresses, the visitor eventually finds themselves standing at the very center of the historical site. At that point, through an opening, the space previously passed—enclosed in modern materials—is now exposed in reverse from the other direction. This visual and spatial reversal strengthens the experience of temporal blending, as the visitor is repeatedly drawn across the boundary between past and present.

Throughout the visit, the sudden opening of large windows (Figure 16i–l) becomes a key element that vividly and distinctly draws attention to the present time. Although both openings serve similar functions, the opening on the right side of the vestibule (Figure 16e–h) acts as a boundary that accommodates the disparate temporal differences within the museum. In contrast, the windows that connect the interior and exterior function as interfaces between the temporal narrative unfolding inside the museum and the continuously evolving present outside. This creates both clear similarities and intriguing differences in their roles [52]. Especially in the windows on Levels 1 and 2, which are the points where the urban landscape of Cologne flows, this absorption dramatically unifies the adjacent joints, minimizing the subsidiary components. The elimination of these subsidiary elements positions the surrounding cityscape not as a separate panorama in the distance but as if it adheres to a portion of the museum, resembling an attached film. This tightly adherent sense of the present appears suddenly. When entering an exhibition room, one may see remnants indicating past times but suddenly senses the present through the large window opening (Figure 17c,d,f,g). Furthermore, an examination of the floor plan (Figure 17f,g) clarifies how this effect of suddenness is spatially articulated.

To situate the experiential interpretation within Kolumba’s architectural organization, the circulation sequence illustrated in Figure 17 clarifies how movement unfolds through a vertically layered system in which each floor presents a distinct spatial condition. The ground level maintains porous visual connections with controlled access, while the first floor introduces a temporary spatial enclosure with limited outward orientation. Upon ascending to the second floor, the circulation expands abruptly, reopening extensive visual exposure toward the city. These shifts in openness, directionality, and spatial hierarchy constitute a structural basis for the unpredictability discussed in this section, shaping the perceptual transitions that occur throughout the visit. The first floor—situated between the ground and second floors—features no opening (Figure 17f) toward the cityscape, resulting in a temporary closure in both external visibility and spatial orientation. As visitors ascend from this visually enclosed level to the second floor, they encounter a dramatic reintroduction of the city and directional awareness. Multiple urban vistas reappear, presented from diverse angles. As confirmed by the diagram (Figure 17g), the openings are irregularly distributed and oriented in varying directions, deliberately absorbing the surrounding cityscape from multiple perspectives. In this way, the large windows in Kolumba bestow light to announce the current time and engage in communication and dialog regarding the city’s direction. This unanticipated flow of space not only intertwines messages linking the past and present, but also continually unfolds a dialog with unforeseen surprises in the arrangement of rooms and even unexpected changes in room heights [51]. The unpredictability within modern cubes of anonymity serves as an element that weaves a continuous dialog.

5. Conclusions

The Kolumba Museum demonstrates how architecture can meaningfully engage with cultural heritage by balancing preservation with spatial transformation. Rather than isolating the past as a static relic, the project constructs a spatial dialog in which historical fragments, contemporary insertions, and sensory experiences interact to generate architectural meaning [33]. This study examines these processes through three complementary approaches: direct sensory observation of spatial and material qualities; analysis of the sequential experience of movement through the museum; and investigation into how sensory cues—particularly the shifts in openness, visibility, and temporal framing articulated in Section 4.2 and Section 4.3—activate situated cognitive responses and support memory formation [4] within the museum’s layered spatial context. Together, these approaches provide a comprehensive framework for understanding how layered architectural experiences can reinterpret heritage across perceptual and interpretive dimensions [3,34]. These conclusions are grounded in the methodological structure established in Section 2 and the analytical distinctions refined in Section 4, aligning the study with established standards of architectural research methodology [1,3] and ensuring that the final claims derive coherently from its conceptual and empirical framework.

In this respect, the Kolumba Museum serves as a concrete model for heritage engagement that extends beyond material conservation. It demonstrates how spatial thresholds, irregular junctions—and, by extension, circulation thresholds where temporal views and directional cues shift—foster modes of embodied engagement that support a more enduring connection to history [33]. By focusing on these architectural mechanisms, this study proposes a methodological framework that integrates phenomenological insight with spatial and analytical tools [40]. This perspective invites future research to consider heritage not merely as a technical challenge or a historical reconstruction, but as an evolving lived experience shaped through sensory and cognitive interaction within contemporary spatial environments [4].

Building on this methodological perspective, the study proceeds to identify and categorize temporal elements within the Kolumba Museum and to examine their interactions across spatial, perceptual, and experiential dimensions. Subsequently, the study analyzes the interconnecting characteristics of these categorized elements. It scrutinizes the features of the boundaries where two or more dissimilar elements converge. Zumthor’s endeavor to handle these encounters as naturally as possible is delineated comprehensively [30]. Nuanced treatments can be divided into formal, perceptual, and experiential solutions. Physically, a notably irregular line was formed at the thresholds at which different historical periods intersected. This amalgamation of arbitrary mismatched lines aspires to achieve the effect of layering, transcending various “bubbles” in spatial acceptance. Additionally, within the confines of the Kolumba Museum, diverse sensory stimuli interact mutually, creating a distinctive perceptual ambiance that transcends layered historical narratives [33]. Furthermore, in terms of experiential continuity, this study proposes an approach featuring multidirectional reversals and varied experiential pathways, deviating from unidirectional temporal flow, thereby stimulating a sustained discourse about time and space [4]. In this respect, architectural messages conveying heritage value [53] within the Kolumba Museum continue to hold profound relevance, even in the context of contemporary everyday life [34,54]. Moreover, this flexibility in the direction of various policies aimed at heritage preservation will provide users with more diverse experiential opportunities and flexible ways to engage with heritage. These findings suggest that, within the boundaries of established heritage preservation principles, a more diverse typology of preservation may be considered—particularly in cases where contextual analysis indicates that experiential connections with the surrounding urban structure can be introduced without compromising historical integrity. Through a specific analysis of this design methodology, this study substantiates the potential for nuanced design strategies in future investigations related to various cultural institutions endowed with historical heritage.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2022R1A2C1008201).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Aksamija, Z. Research Methods for the Architectural Profession; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Khaznadar, B.M.A.; Baper, S.Y. Sustainable continuity of cultural heritage: An approach for studying architectural identity using typo-morphology analysis and perception survey. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groat, L.N.; Wang, D. Architectural Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, P.; Mura, S.; Hamilton, S. (Eds.) New Sensory Approaches to the Past; UCL Press: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuśnierz-Krupa, D.; Krupa, M. New Life of Medieval Churches in Maastricht. Conserv. News 2008, 24, 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Sun, M.; Wang, D. Research frameworks, methodologies, and assessment methods concerning the adaptive reuse of architectural heritage: A review. Built Herit. 2021, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaie, F.; Alipour, M.; Hosseini, S.B. Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings: A systematic literature review. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 13, 66–83. [Google Scholar]

- Van Laar, M.; Schröder, J.; van Timmeren, A. What matters when? An integrative literature review on decision criteria in different stages of the adaptive reuse process. Cities 2024, 142, 104589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kim, Y.; Park, J. A holistic approach to adaptive reuse research focused on design strategy and its extended categories. J. Archit. Des. Res. 2025, 14, 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, A.; Ciritci, O. Adaptive reuse of historical buildings through cultural heritage conservation: The Warehouse of Sirkeci Train Station. Herit. Sci. Rev. 2025, 9, 112–130. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y. A model approach for post evaluation of adaptive reuse of historical buildings. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 11, 57. [Google Scholar]

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter); ICOMOS: Venice, Italy, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO; ICOMOS. The Nara Document on Authenticity; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Nara, Japan, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Australia ICOMOS. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance; Australia ICOMOS: Burwood, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jokilehto, J. A History of Architectural Conservation; Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Feilden, B.M. Conservation of Historic Buildings, 3rd ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Plevoets, B.; Van Cleempoel, K. Adaptive Reuse of the Built Heritage: Concepts and Cases of an Emerging Discipline; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, L. Adaptive Reuse: Extending the Lives of Buildings; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Goulding, C. The museum environment and the visitor experience. Eur. J. Mark. 2000, 34, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. Representational and authentic: Sustainable heritage message through architectural experience in the case of Bernard Tschumi’s acropolis museum, Athens. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Zhang, Y.; Han, W. Architectural heritage preservation for rural revitalization: Typical case of traditional village retrofitting in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.A. Historic Preservation Technology: A Primer; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, N.; Tyler, I.R.; Ligibel, T.J. Historic Preservation, Third Edition: An Introduction to Its History, Principles, and Practice; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. Learning from Museums: Visitor Experiences and the Making of Meaning; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mayes, T.M. Why Old Places Matter: How Historic Places Affect Our Identity and Well-Being; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, A.K.; Adair, J.G. (Eds.) Defining Memory: Local Museums and the Construction of History in America’s Changing Communities; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, L. Adaptive Reuse in Architecture: A Typological Index; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Duka, D. Kolumba, 2nd ed.; Archbishop’s Palace: Prague, Czech Republic, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mäckler, C.; Fietz, F.P.; Göke, S. Stadtbausteine. Elemente der Architektur. Texte; DOM Publishers: Berlin, Germany, 2018; ISBN 9783869226248. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.; Surmann, U.; Steinmann, M.; von Flüe, B. (Eds.) Kolumba Kapelle; Kolumba und Autoren: Köln, Germany, 2020; ISBN 978-3-9819975-2-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.; Surmann, U.; Steinmann, M.; von Flüe, B. (Eds.) Kolumba Ausgrabung; Kolumba—Werkhefte und Bücher, Band 56; Kolumba und Autoren: Köln, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3-9818008-9-0. [Google Scholar]

- Malnar, J.M.; Vodvarka, F. Sensory Design; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, R. Research Methods for Architecture; Laurence King Publishing: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, N.; Duka, D. (Eds.) Kolumba: A Special Edition in English Published by the Scholarly Czech Magazine SALVE; Krystal Publishers OP: Prague, Czech Republic, 2011; pp. 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Zumthor, P. Atmospheres: Architectural Environments—Surrounding Objects; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2006; ISBN 978-3-7643-7585-0. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J. Architectural heritage value dispersed on sensuous thresholds in Kim Swoo Geun’s Arario museum in space, Seoul. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnheim, R. Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye, Rev. ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- McManus, P.M. Memories as indicators of the impact of museum visits. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 1993, 12, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, G. Design in Architecture: Architecture and the Human Sciences; Wiley: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Zumthor, P. Peter Zumthor Thinking Architecture, 3rd ed.; Birkhäuser Verlag GmbH: Basel, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, W.M.C.; Ripman, C.H. Perception and Lighting as Formgivers for Architecture; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Zumthore, P. Atmosphären: Architektonische Umgebungen. Die Dinge Um Mich Herum; Birkhäuser Verlag GmbH: Basel, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zumthor, P. Kunsthaus Bregenz. El Croquis 1998, 88–89, 268–307. [Google Scholar]

- Weclawowicz-Gyurkovich, E. Odważna współczesna architektura w historycznym otoczeniu—Kolumba Museum w Kolonii. Czasopismo Techniczne. Architektura 2017, 2-A, 115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Savoie, J.; Tremblay, M.; Fortin, A. Key factors for revitalising heritage buildings through adaptive reuse. Build. Cities 2025, 6, 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.T.; Burnette, C.; Moleski, W.; Vachon, D. (Eds.) Designing for Human Behavior: Architecture and the Behavioral Science; Dowden, Hutchinson & Ross: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Kim, S. Heritage value through regeneration strategy in Mapo cultural oil depot, Seoul. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachten, J. Into the Expanse, 1st ed.; Kolumba-Taschenbuch: Köln, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Academy Editions: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Pallasmaa, J. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Intentions in Architecture; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillova, K.; Fu, X.; Lehto, X.; Cai, L. What makes a destination beautiful? Dimensions of tourist aesthetic judgment. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anholt, S. Places: Identity, Image and Reputation; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.