Abstract

The growing demand for concrete in tropical regions faces two unresolved challenges: the high carbon footprint of ordinary Portland cement (OPC) and limited understanding of how supplementary cementitious materials affect the mechanical performance of laterite rock aggregates concrete. Although metakaolin (MK) is a highly reactive pozzolan, its combined use with laterite rock aggregates concrete and its influence on strength development and microstructure have not been sufficiently clarified. This study investigates the mechanical behavior and sustainability potential of laterite rock aggregate concrete in which OPC is partially replaced by MK at 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% by weight. All mixes were prepared at a constant water–binder ratio of 0.50 and tested for workability, compressive strength, split-tensile strength, and flexural strength at 7, 14, and 28 days, with and without a polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer. The results show that MK significantly enhances the mechanical performance of laterite rock concrete, with an optimum at 10% replacement: the 28-day compressive strength increased from 35.6 MPa (control) to 53.9 MPa in the superplasticized mix, accompanied by corresponding gains in tensile and flexural strengths. SEM–EDS analyses revealed microstructural densification, reduced portlandite, and a refined interfacial transition zone, explaining the improved strength and cracking resistance. From an environmental perspective, a 10% MK replacement corresponds to an approximate 10% reduction in clinker-related CO2 emissions, while the use of locally available laterite rock reduces the dependence on quarried granite and transportation impacts. The findings demonstrate that MK-modified laterite rock concrete is a viable and eco-efficient option for structural applications in tropical regions. The study concludes that MK-enhanced laterite rock aggregate concrete can deliver higher structural performance and improved sustainability without altering conventional mix design and curing practices.

1. Introduction

Ordinary Portland cement (OPC)-based concrete remains the backbone of modern infrastructure; however, its environmental burden is increasingly incompatible with global decarbonization targets [1]. The cement industry is responsible for approximately 7–8% of global anthropogenic CO2 emissions, with current direct emissions intensities of approximately 0.55–0.60 t CO2 per tonne of cement and little improvement since 2018 [2,3]. These emissions arise predominantly from the calcination of limestone during clinker production, supplemented by energy-related emissions from high-temperature kilns [4,5]. Simultaneously, the projected growth in construction demand, especially across the Global South, implies that absolute cement consumption will remain high, reinforcing the need for strategies that reduce clinker content, incorporate locally available supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs), and utilize alternative aggregates without compromising structural performance [6,7,8].

Among SCMs, metakaolin (MK), a highly reactive calcined clay derived mainly from kaolinite, has emerged as a technically robust and relatively widely available option. Classical reviews by Sabir et al. [9] and Weise et al. [10] showed that MK, when produced under appropriate calcination conditions, exhibits high pozzolanic activity, reacts rapidly with portlandite, and leads to a refined pore structure and improved durability in cementitious systems. Recent work and position papers have argued that metakaolin is a promising next-generation SCM for aggressive environments and low-carbon concretes, particularly when other industrial by-product SCMs (such as fly ash and GGBS) are scarce or geographically constrained [6,11,12].

Metakaolin-blended concretes typically exhibit enhanced compressive strength, reduced permeability, chloride diffusivity, and improved resistance to chemical attack when MK replaces approximately 5–20% of OPC by mass, depending on the mixture design and performance targets [13,14]. Poon et al. [15] reported that 5–15% MK replacement in high-performance concrete significantly increased the early age strength and refined the pore-size distribution compared with plain OPC and other SCMs such as silica fume and fly ash. Khan 2020 [16] found that mixes containing approximately 10% metakaolin often achieved the highest compressive strengths across a range of curing ages, highlighting the importance of optimizing replacement levels rather than maximizing the SCM content. Life-cycle and environmental assessment studies have shown that partial replacement of OPC with MK can reduce embodied carbon and other environmental impacts, particularly when MK is sourced from locally available clays or industrial by-products, such as dealuminated kaolin [17,18].

In parallel with its use as a supplementary cementitious material in OPC systems, metakaolin has been extensively employed as the primary aluminosilicate precursor in geopolymer binders and concrete over the last decade. Recent state-of-the-art reviews have emphasized that metakaolin-based geopolymer concretes (MK-GPCs) are among the most promising low-carbon alternatives to Portland cement concrete because of their high early strength, dense microstructure and excellent durability in aggressive environments [19,20,21]. Amar et al. [22] reviewed MK-based geopolymer concrete and highlighted its superior water, thermal, and corrosion resistance compared to OPC systems, as well as its potential to reduce CO2 emissions by significantly reducing or eliminating clinkers. More focused reviews on MK-based alkali-activated materials and porous geopolymers also indicate that MK-geopolymers can deliver compressive strengths above 40–60 MPa with tailored pore structures and very low thermal conductivity, making them suitable for both structural and insulating applications [23,24,25,26].

At the structural scale, recent experimental studies have demonstrated that MK-GPCs can match or exceed the mechanical performance of conventional concrete in terms of compression, tension, and flexure. Borçato et al. [27] reported compressive strengths between approximately 45 and 60 MPa after 28 d of ambient curing for MK-based geopolymers incorporating quarry dust, confirming that high strength is achievable without heat curing when the mix design is optimized. Alsaif et al. [28] developed metakaolin-based rubberized geopolymer concrete and showed that, despite the inclusion of crumb rubber, an appropriate mixture design yields satisfactory compressive and flexural strengths together with improved impact resistance and energy absorption. The flexural behavior of MK-GPC elements has been explored in detail. For instance, recent investigations on reinforced geopolymer slabs incorporating metakaolin and nano-silica showed ductile flexural response and comparable or enhanced load capacity with respect to OPC reference slabs [29,30]. Complementary work on kaolin/metakaolin-based geopolymers containing small additions of Portland cement has shown that early-age strength limitations can be mitigated by hybrid binder strategies, especially under moderate heat curing and with proper use of superplasticizers [31,32]. The durability of MK-based geopolymer systems has been a major research focus. Hossain and Akhtar [33] investigated MK-based geopolymer concrete produced by 3D printing and reported a refined pore structure, reduced water absorption, and relatively low oxygen permeability, confirming the suitability of MK-GPCs for durable, digitally manufactured elements. Gao et al. [34] studied the degradation behavior of MK-geopolymer composites in real and simulated acidic media and found that although some mass and strength loss occurred, MK-based geopolymers generally exhibited better chemical resistance than conventional cementitious composites.

Other studies have considered high-temperature performance, indicating that although MK-geopolymers may lose some strength upon exposure to elevated temperatures, they often retain a higher residual strength than OPC systems at comparable thermal loads. Self-compacting MK-based geopolymer concretes incorporating steel fibers and recycled aggregates have been shown to achieve adequate flowability together with improved tensile capacity and satisfactory durability indices, underscoring the compatibility of MK-GPCs with recycled constituents and fiber reinforcement [35,36,37].

In addition to conventional specimen-based testing, optimization and predictive modelling approaches have recently been applied to MK-based geopolymers. Hawa et al. used a Taguchi design to quantify the influence of the activator-to-metakaolin ratio, sodium silicate-to-sodium hydroxide ratio, alkali molarity, and curing temperature on the fresh and hardened properties of MK-geopolymer mortars, identifying optimum combinations that maximize strength while maintaining workable rheology. Abbas et al. employed gradient-boosting machine learning models to accurately predict the compressive strength of MK-geopolymer concrete from mix-design parameters, illustrating the usefulness of data-driven tools for the rational proportioning of geopolymer systems [38,39]. Recent bibliometric analyses and hotspot studies further show that research on MK-based geopolymers is rapidly expanding, with particular emphasis on hybrid MK–slag systems, fiber reinforcement, and performance in severe environmental exposures [40]. Taken together, this body of work confirms that metakaolin is not only an effective SCM in OPC-based binders but also a key precursor for high-performance geopolymer concretes. MK-geopolymers can deliver high strength, excellent durability, and substantial reductions in embodied CO2 compared to OPC concrete, and optimization methodologies are increasingly available to refine their mix design. Nevertheless, most existing MK-geopolymer studies have been conducted with conventional siliceous aggregates (such as river sand, crushed granite, or quarry dust), while the integration of region-specific geomaterials, such as laterite rock, into MK-based binder systems is still relatively unexplored [13,41,42].

In many tropical and subtropical regions, the challenge of reducing the environmental footprint of concrete is coupled with pressure on natural sand and rock resources. Laterite, a ferruginous and aluminous soil/rock formed by prolonged weathering in hot and humid climates, is widely available in such regions and has long been used in earth construction. More recently, it has been investigated as a fine or coarse aggregate in “laterized concrete,” in which river sand and/or conventional aggregates are partially replaced by lateritic material [43,44]. Early studies by Muthusamy et al. [45] demonstrated that laterized concrete can attain structural-grade compressive strengths when properly proportioned, with recommended limits on laterite content and water–cement ratio to control strength and creep. Udoeyo et al. [46] reported that laterized concrete mixes could achieve strength performance comparable to that of conventional concrete at optimum laterite replacement levels, provided mix design considerations were carefully addressed.

Subsequent experimental and review studies have expanded our understanding of the mechanical properties and durability of laterized concrete. Reviews of laterite concrete properties and more recent studies have confirmed that laterite can serve as a sole fine aggregate or as a major replacement for sand in structural concrete, although with trade-offs in workability and shrinkage behavior [47]. For example, the higher water absorption and angular particle shape of laterite tend to reduce workability and increase water demand, necessitating appropriate adjustments to mix proportions and the possible use of chemical admixtures [48,49,50].

Nevertheless, recent investigations on strength, microstructure, and durability across various laterite contents have reaffirmed that laterized concrete can meet structural performance requirements when optimized, and they offer clear sustainability advantages by reducing reliance on river sand and enabling the use of locally abundant geomaterials [51]. At the same time, research on MK-enhanced systems has begun to intersect with work on lateritic materials. Studies on laterite-bearing mortars and concrete incorporating various SCMs, including volcanic ash, rice husk ash, and MK, indicate that synergistic combinations of local aggregates and pozzolanic binders can yield adequate or improved strength and durability while substantially lowering the OPC demand [52,53,54]. Hybrid mixtures in which laterite partially replaced sand and MK partially replaced cement have shown promising results. For example, a recent investigation into hybrid OPC–activated metakaolin concrete with partial sand replacement by laterite reported that an optimum combination of approximately 10% MK and 30% laterite (as fine aggregate) produced compressive strengths close to those of reference mixes while significantly reducing natural sand consumption and OPC content. Metakaolin has been successfully used to stabilize lateritic soils and develop laterite-based geopolymers with substantial improvements in unconfined compressive strength and stiffness [55].

Despite these advances, several important knowledge gaps remain in the literature. First, most studies involving laterite and metakaolin focus on lateritic sand or soil as a fine aggregate or geopolymeric precursor; comparatively few studies have addressed concrete in which laterite rock is used as a coarse aggregate in combination with metakaolin as a cement replacement. Laterite rock, which may differ from lateritic soils in grading, mineralogy, porosity, and strength, can significantly influence the interfacial transition zones, fracture behavior, and long-term durability of concrete, meaning that results from lateritic sand systems are not directly transferable. Second, although it is known that both the metakaolin content and laterite replacement level strongly affect workability and strength development, comprehensive optimization studies that jointly vary these parameters in laterite rock concrete are scarce. Many existing studies have reported a limited set of replacement levels or focused on single response variables (e.g., compressive strength at 28 days) without considering the broader performance envelope or environmental benefits. Third, the increasing availability of advanced optimization and predictive modelling tools has not yet been fully leveraged for metakaolin–laterite systems. Recent studies on metakaolin-based geopolymers and cementitious systems have shown that techniques such as response surface methodology (RSM) and machine learning models can effectively map the relationships between chemical composition, mix parameters, and compressive strength, enabling rational mix design and performance prediction. However, these approaches have been applied primarily to alkali-activated binders or conventional aggregate concrete rather than to laterite rock concrete, where the combined effects of reactive MK, porous laterite aggregates, and conventional OPC hydration create a more complex microstructural evolution.

In this context, MKN-enhanced laterite rock concrete represents a promising pathway for regionally adapted, lower-carbon structural materials. By partially replacing OPC with highly reactive calcined clay and substituting conventional coarse aggregates with locally available laterite rock, it may be possible to (i) maintain or enhance mechanical performance, (ii) reduce embodied CO2 by lowering clinker content and transportation-related impacts, and (iii) alleviate the pressure on natural river sand and rock quarries in tropical regions. However, realizing this potential requires a systematic understanding of how metakaolin dosage, laterite rock replacement level, and water-to-binder ratio jointly influence the fresh and hardened properties of concrete and where the optimum balance lies between strength performance and cement reduction.

Therefore, this study investigates the strength optimization and sustainable cement replacement potential of metakaolin-enhanced laterite rock concrete. Specifically, this study aimed to:

- Influence of metakaolin content (as a partial replacement of OPC) on the compressive, split tensile, and flexural strengths of laterite rock concrete at different curing ages.

- Evaluate the effect of laterite rock replacement level (as partial or full replacement of conventional coarse aggregate) on strength development and failure behavior, in combination with varying MK dosages.

- Identify optimal mix proportions that achieve the target strength classes while maximizing OPC replacement and laterite utilization using an appropriate optimization framework (e.g., statistically designed experiments and multi-criteria analysis).

- Assess the potential sustainability benefits of the optimized mixes in terms of reduced cement consumption and indicative reductions in embodied CO2 relative to conventional OPC concrete of similar strength.

By addressing these objectives, this study seeks to contribute to the broader agenda of sustainable concrete technology by providing a scientifically grounded mixed design framework for metakaolin-enhanced laterite rock concrete. The findings are expected to be particularly relevant for tropical developing countries, where laterite is abundant, high-quality industrial SCMs are limited, and the need for low-carbon yet structurally reliable construction materials is especially acute.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Research Program

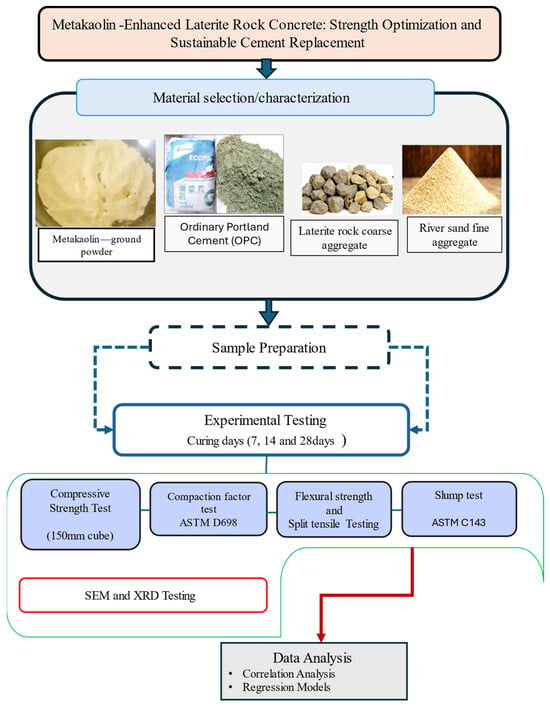

The experimental research program was designed in a sequence of integrated stages to link the material characterization, mix design, mechanical performance, and microstructural behavior of metakaolin-modified laterite rock concrete. First, all constituent materials (OPC, metakaolin, river sand, and laterite rock) characterized in terms of physical properties and, for metakaolin, chemical composition and mineralogical structure. The materials were sourced from Lagos state, Nigeria and taken to Yabatech laboratory in Lagos, Nigeria for experimental testing and analysis. Second, concrete mixtures were proportioned at a constant water–binder ratio of 0.50 with five metakaolin replacement levels (0–20% by mass of binder), while keeping the total binder content and aggregate volume fraction constant. Third, fresh concrete was produced in controlled laboratory batches, cast into standard cubes, cylinders, and beam specimens, and water-cured at 27 ± 2 °C for 7, 14, and 28 days. In the fourth stage, the experimental test program covered both fresh and hardened properties: workability (slump and compacting factor) was measured immediately after mixing, and compressive, split tensile, and flexural strengths were determined at each curing age for mixes with and without polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer. Finally, representative specimens from the control and optimum metakaolin mixes were subjected to SEM–EDS analysis to assess the microstructural development and interfacial transition zone refinement, and the results were used together with the strength data to derive empirical correlations and to estimate the CO2 reduction associated with partial cement replacement. The overall methodological sequence of the study is summarized in the flowchart in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow-chart showing the experimental testing procedure.

2.2. Material Descriptions

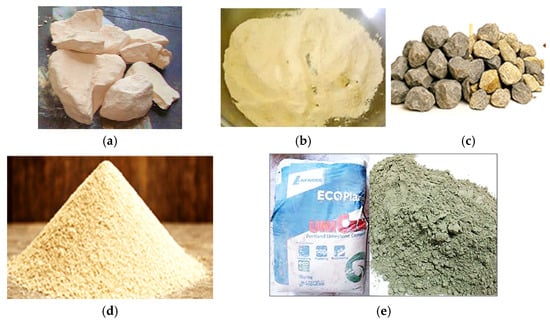

A key aspect in the design of cementitious systems is the packing density promoted by raw materials, which is strongly governed by their particle size distribution (PSD). In this study, the physical and chemical characteristics of the constituent materials, including specific gravity, chemical composition, and PSD, were determined to ensure adequate packing, workability, and strength development of metakaolin-modified laterite rock concrete. The main materials used in the research are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Materials used for the concrete mixes: (a) Metakaolin—raw (solid) form; (b) Metakaolin—ground powder; (c) Laterite rock coarse aggregate; (d) River sand fine aggregate; (e) Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC).

2.2.1. Coarse Aggregate (Laterite Rock)

Laterite rock, an iron-rich weathered material commonly found in tropical regions, was selected as the coarse aggregate (Figure 2c). The rock was mechanically crushed and sieved to achieve a nominal maximum particle size of 20 mm to ensure compatibility with conventional structural concrete applications. Testing revealed a specific gravity of 2.64 and a water absorption capacity of 2.74%, which are within the acceptable limits of ASTM C127 [56] for specific gravity and ASTM C136 [57] for particle-size distribution. Before incorporation into the mix, the aggregates were thoroughly washed to remove adhering fines, and subsequently pre-soaked and brought to saturated surface-dry (SSD) condition to maintain consistent moisture conditions and correctly account for absorbed water in the mix design. The grading curve satisfied the ASTM C33 limits for coarse aggregates, with a uniform distribution between 4.75 mm and 20 mm. This ensured adequate interlocking and mechanical stability while also providing sufficient void space for paste penetration and effective ITZ formation.

2.2.2. Fine Aggregate

Clean, well-graded natural river sand was employed as the fine aggregate, which met the requirements of ASTM C33 [58]. The sand had a maximum particle size of 4.75 mm, fineness modulus of 2.70, and specific gravity of 2.63, reflecting a well-balanced particle-size distribution suitable for producing workable concrete. The material was confirmed to be free from clay, silt, and organic impurities, which could negatively affect bonding and durability (Figure 2d). Prior to batching, the saturated and surface dry (SSD) sand was sieved to maintain uniformity across all the mix proportions. The PSD fell entirely within the recommended grading limits of ASTM C33 [58], indicating a well-graded fine aggregate with adequate proportions of coarse and fine fractions. This grading contributes to an improved packing density, reduced paste demand, and a lower risk of segregation in fresh concrete.

2.2.3. Water

Potable water meeting the ASTM C1602 [59] criteria was used for both the mixing and curing operations. The water was verified to be free from harmful contaminants, such as oils, acids, alkalis, and organic substances, all of which could interfere with cement hydration or compromise long-term concrete durability. Its quality ensures reliability and uniform hydration throughout the curing process.

2.2.4. Cement

Grade 43 ordinary Portland cement (OPC), conforming to the requirements of ASTM C150 [60], was utilized as the primary binding material in all concrete mixtures. The cement possessed a specific gravity of 3.15 and a standard consistency of 31%, indicating its suitability for achieving the desired workability. The measured initial and final setting times were 35 and 520 min, respectively, aligned well with standard specifications for structural applications. Prior to use, the cement was carefully inspected to ensure that it was free from lumps, an indication of undesirable pre-hydration, and stored in sealed moisture-proof containers to prevent exposure to humidity and maintain its reactivity (Figure 2e).

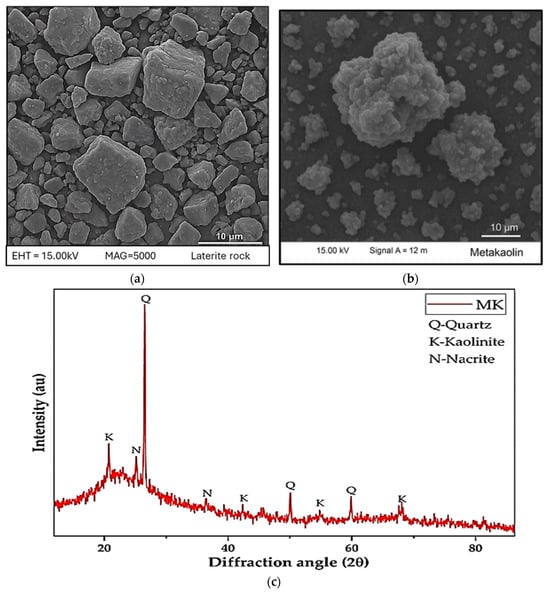

2.2.5. Metakaolin

The metakaolin (MK) used in this study was produced from locally sourced kaolinitic clays. The clay was calcined at a fixed temperature of 750 °C in a laboratory muffle furnace to obtain an amorphous aluminosilicate phase suitable for pozzolanic applications (Figure 2a,b). After calcination, the material was ground into a fine powder, achieving a measured specific surface area of 15,000 m2/kg. The metakaolin had a specific gravity of 2.52, which is lower than that of OPC (3.15). This difference in density was considered in the adjusted aggregate proportions to maintain a constant total volume of concrete in mixes with MK replacement. The processed MK met the chemical and physical requirements of ASTMC618 [58] Class N pozzolans. X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis was performed on the calcined and ground materials to determine the oxide composition. The results of the laboratory tests are presented in Table 1, and they confirm that MK possesses a high proportion of reactive silica and alumina, indicating a strong pozzolanic potential. Figure 3 shows microstructural evidence of metakaolin: (a) SEM showing laterite rock, (b) SEM of metakaolin, and (c) XRD pattern illustrating metakaolin. As expected for a high-reactivity pozzolan, MK is significantly finer than OPC, with a large fraction of particles in the sub-10 µm range. This fine PSD contributes to enhanced packing of the binder phase and provides a strong filler effect in addition to its pozzolanic reactivity, which is particularly beneficial for refining the pore structure and interfacial transition zone in laterite rock concrete.

Table 1.

Chemical Composition of Metakaolin.

Figure 3.

(a) SEM showing laterite rock; (b) SEM of metakaolin; (c) XRD pattern illustrating metakaolin.

2.3. Mix Proportioning

The mix proportioning was carried out in accordance with ASTM C938 [61] for normal-weight concrete, targeting a characteristic 28-day compressive strength of approximately 25 MPa. A constant water–binder ratio (w/b) of 0.50 and a total binder content of 400 kg/m3 were adopted for all mixtures to ensure direct comparability across different metakaolin (MK) replacement levels. In this study, MK replaced ordinary Portland cement (OPC) at 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% by mass of OPC, while keeping the total binder mass constant. The metakaolin replacement levels (0–20% by mass of binder) were selected based on previous studies [62,63] indicating that MK contents in the range of 5–15% generally optimize strength and durability, while higher dosages can lead to cement dilution and workability problems. Both the fine and coarse aggregates were used in saturated surface-dry (SSD) condition. The measured water absorption values (sand ≈ 1.2%; laterite rock ≈ 2.74%) were accounted for during pre-soaking to ensure that only the free water contributed to the w/b ratio. The free mixing water remained constant at 200 kg/m3 for all mixtures. The fine-to-coarse aggregate mass ratio was maintained at 40:60, corresponding to 720 kg/m3 of SSD river sand and 1080 kg/m3 of SSD laterite rock aggregate. These quantities remained unchanged across all mixes because MK replacement affects only the binder fraction, and the aggregates were proportioned based on SSD mass to maintain consistent concrete yield and aggregate volume. A polycarboxylate ether (PCE)–based high-range water-reducing admixture was used in mixes designated “with SP.” The dosage was fixed at 0.8% of the total binder mass, consistent with manufacturer recommendations for achieving adequate dispersion of ultrafine MK particles and improving workability. The resulting SSD-based mix proportions for all metakaolin replacement levels are presented in Table 2, including the binder distribution, aggregate contents, water dosage, and superplasticizer details.

Table 2.

Mix Proportion of Laterite Rock Concrete with Varying Metakaolin Content (kg/m3).

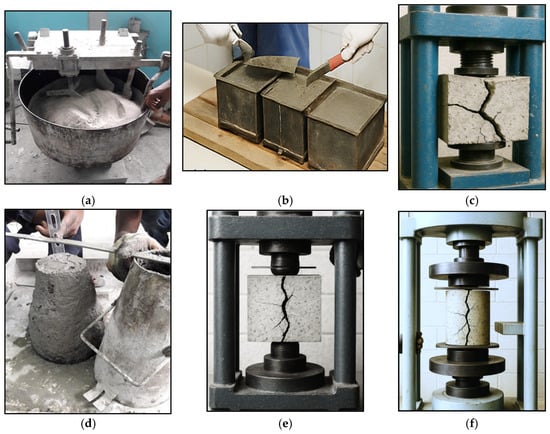

2.4. Sample Preparation

Concrete was prepared in controlled batches using a mechanical mixer. All dry constituents (cement, metakaolin, and both fine and coarse aggregates) were blended for two minutes to achieve a uniform mixture. Water was then introduced gradually to ensure proper hydration and consistency. Fresh concrete was placed into standard molds suited to the mechanical tests: 150 mm cubes for compressive strength, cylinders measuring 150 mm in diameter and 300 mm in height for split-tensile strength, and beams of 100 × 100 × 500 mm for flexural strength. Each mold was filled into three layers, compacted manually with a tamping rod, and leveled to eliminate entrapped air. After twenty-four hours, the specimens were removed from the molds and transferred to a curing tank maintained at 27 ± 2 °C. They remained in water until their respective testing ages were 7, 14, and 28 days. Figure 4 illustrates the materials testing methods used in the research.

Figure 4.

Material testing methods: (a) Mixing Process; (b) Moulding of cubes; (c) Compressive strength test; (d) Slump test; (e) Flexural strength test; (f) Splitting test.

2.5. Testing Methods

2.5.1. Slump Testing

To assess the workability of the freshly mixed concrete, a slump test was performed following the procedures outlined in ASTM C143 [64]. This test provides a quick and reliable indication of the concrete’s consistency and ease of placement by measuring the vertical settlement (slump) of a cone-shaped sample after the mold is lifted. In addition, a compacting factor test was conducted in accordance with ASTM D698 [65] to further evaluate the behavior of the concrete under compaction. Unlike the slump test, the compacting factor method is particularly suitable for mixtures with low workability because it quantifies the degree of compaction achieved under a standardized dropping procedure. Together, these two tests enabled a comprehensive evaluation of the effects of metakaolin (MK) and the superplasticizer on the flowability, cohesiveness, and overall workability of fresh concrete immediately after mixing.

2.5.2. Compressive Strength Test

The compressive strength of the hardened concrete was measured using a 2000 kN capacity compression testing machine in accordance with ASTM C39 [66]. This test is fundamental for assessing the load-bearing capacity of concrete because it determines the maximum compressive stress that the material can withstand before failure. For each concrete mix, three cube specimens were cast and tested at curing ages of 7, 14, and 28 days to capture the strength development over time. The early age results (7 and 14 days) provided insight into the rate of hydration and the influence of MK on early strength gain, whereas the 28-day testing represented the standard benchmark for evaluating the maturity and structural adequacy of the concrete.

2.5.3. Split Tensile Strength Test

The split tensile strength of the concrete was determined according to ASTM C496 [67], which specifies an indirect tensile testing method using cylindrical specimens. Each specimen was placed horizontally between the loading platens of the testing machine and subjected to diametral compression at a constant loading rate of 2.0 MPa/min. This setup induced tensile stresses perpendicular to the applied load, until the specimen split along its vertical diameter. The test results provided an estimation of the tensile capacity of the concrete, which is critical for understanding its cracking behavior, resistance to splitting, and overall durability.

2.5.4. Flexural Strength Test

The flexural strength and modulus of rupture were evaluated using a two-point loading method in accordance with ASTM C78 [68]. The beam specimens were tested over a span length of 400 mm, with the load applied symmetrically at two points to create a region of constant bending moment. This method is effective for determining the bending resistance of concrete, which is essential for structural elements, such as slabs, beams, and pavements. The modulus of rupture (fr) was calculated using Equation (1):

where P denotes the maximum applied load (N), L denotes the effective span length (mm), b denotes the width of the specimen (mm), and d denotes the depth of the specimen (mm).

2.6. SEM–EDS Microstructural Analysis

Microstructural characterization of selected concrete specimens was performed using scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM–EDS). A JEOL JSM-7600F emission scanning electron microscope (sourced in Yabatech Laboratory, Lagos, Nigeria) was used for imaging and elemental analysis. The SEM operated at an accelerating voltage between 15–20 kV, with a working distance of 10–12 mm, which provided adequate spatial resolution for observing matrix densification, pore morphology, and interfacial transition zone features.

2.6.1. Sample Preparation for SEM-EDS

Concrete fragments were obtained from the interior of 28-day cured specimens to avoid the influence of surface carbonation. Each specimen was cut into approximately 10–15 mm pieces using a diamond saw, after which the fragments were dried at 50 °C for 24 h to eliminate moisture that could disrupt the vacuum conditions during analysis. To preserve and stabilize the internal microstructure, the dried samples were impregnated with epoxy resin. They were then polished in successive stages, beginning with 400–1200 grit silicon carbide papers and followed by fine polishing with a 1 µm alumina suspension to expose the relevant microstructural features. Finally, the prepared surfaces were sputter-coated with a thin (~10 nm) layer of gold or gold–palladium using a metallization unit such as the Quorum SC7620, ensuring adequate electrical conductivity and reducing charging effects during imaging.

2.6.2. EDS Procedure

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) was employed to characterize the elemental composition of the polished concrete samples. Analyses were conducted in both spot-analysis mode, to obtain localized compositional information, and selected-area mapping mode, to visualize spatial variations in element distribution. For each measurement, a live time of 60–90 s was applied to optimize the signal-to-noise ratio and ensure adequate X-ray count statistics for reliable qualitative interpretation.

The acquired spectra were used to identify and compare the relative concentrations of the principal elements associated with cement hydration products—namely calcium (Ca), silicon (Si), aluminum (Al), and iron (Fe). Elemental maps generated from the selected-area scans enabled detailed examination of the microstructural features across the matrix, with particular attention to differences between the control mix and the metakaolin (MK)-modified formulations. These maps were further evaluated to discern trends in the densification of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ), providing insights into the influence of MK incorporation on the spatial distribution of hydration products and the overall refinement of the microstructure.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Aggregate Characterization

The physical properties of the aggregates were evaluated to determine their suitability for the production of structural concrete. The tests conducted included specific gravity, water absorption, abrasion resistance, and particle size distribution tests, following ASTM C127 [56], ASTM C136 [57], and ASTM C131 [69]. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Physical properties of fine and coarse aggregates.

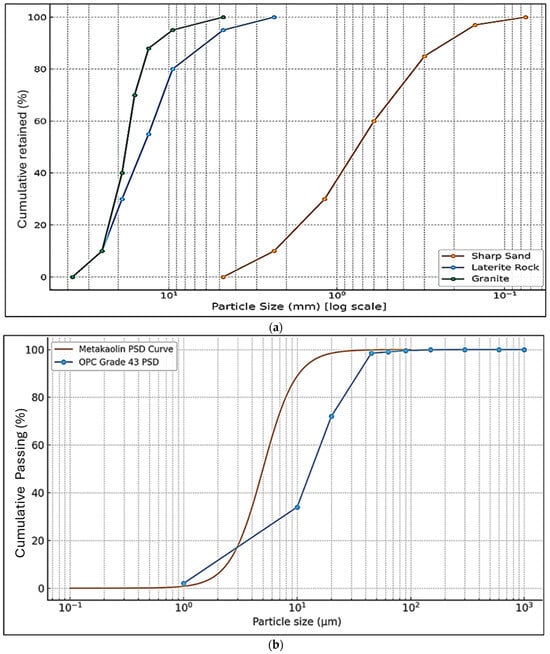

The specific gravity of the aggregates ranged from 2.63 for sand to 2.95 for granite, with the laterite rock exhibiting an intermediate value of 2.64. These values fall within the acceptable range (2.4–2.9) specified for normal-weight aggregates, indicating that laterite rock can serve as a viable coarse aggregate. The water absorption capacity of the laterite rock (2.74%) was higher than that of granite (0.86%), reflecting its more porous nature and iron-oxide-rich microstructure. The higher absorption tendency may influence the effective water–binder ratio and workability of the fresh mix, necessitating careful moisture control during batching. The Los Angeles abrasion value of laterite rock (35.84%) was higher than that of granite (24.56%), suggesting a relatively lower resistance to mechanical wear. Nevertheless, the value remained below the 40% limit specified for structural concrete aggregates, confirming its adequacy for moderate-strength concrete applications. The particle size distributions (Figure 5) of both the sand and laterite rocks satisfied ASTM C33 [70] grading requirements. The sand was well graded with a fineness modulus of 2.70, ensuring a good packing density and minimizing voids in the concrete matrix. The laterite rock, crushed to a nominal maximum size of 20 mm, provided acceptable gradation for coarse aggregates, promoting adequate interlocking and uniform stress transfer. Aggregate characterization confirmed that laterite rock possesses adequate density, grading, and mechanical integrity for use as a partial or complete substitute for conventional granite in structural concrete. However, its relatively high porosity and abrasion value highlight the need for matrix modification, such as metakaolin incorporation, to refine the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) and enhance the overall durability of lateritic rock concrete.

Figure 5.

Particle size distribution curve: (a) Sharp sand, laterite rock and granite; (b) Metakaolin (MK) and Ordinary Portland cement (OPC).

3.2. Workability

The workability of the fresh laterite rock concrete mixtures was assessed using the slump test and compacting factor test in accordance with ASTM C143 [64]. The results for mixes with and without superplasticizer (SP) are presented in Table 4. Overall, the incorporation of metakaolin (MK) led to a marked reduction in workability, particularly in the mixtures without SP, where slump values decreased from 118 mm in the control mix (M0) to zero slump at MK contents ≥10%. This trend is consistent with previous findings on MK-blended concretes, where the introduction of MK typically leads to lower workability because of its very high fineness, high specific surface area, and surface activity [71]. The increased surface area of MK particles requires more free water for lubrication, thereby reducing the effective water available to achieve flow at constant w/b ratios [72]). Several authors have similarly reported that partial replacement of OPC with MK causes rapid slump loss and stiffer mixes unless chemical admixtures are used to compensate for the elevated water demand [73,74]. The reduction in workability is further exacerbated by the characteristics of laterite rock aggregates, which possess higher water absorption and more angular particle shapes compared with conventional granite aggregates. Earlier studies on laterized concrete [45,46] have shown that these properties tend to decrease flowability and necessitate additional water or admixtures to maintain adequate workability. Therefore, the combined effect of MK fineness and laterite aggregate absorption explains the substantial slump reductions observed in the MK-modified mixes without SP. The addition of polycarboxylate-based SP significantly improved the workability of the mixes, restoring collapse slumps (≥200 mm) for MK contents up to 10%. This behavior agrees with reports by Ouldkhaoua et al. [63] who demonstrated that high-range water-reducing admixtures effectively disperse MK particles and release trapped water, thereby enhancing flowability. However, even with SP, workability decreased at higher MK contents (≥15%), indicating that excessive MK can adsorb SP molecules and reduce their dispersion efficiency—a phenomenon widely acknowledged in MK–admixture compatibility studies.

Table 4.

Workability of laterite rock concrete with varying MK contents.

The compacting factor results further support the slump observations. Mixes without SP showed reduced compaction efficiency with increasing MK content (0.974 for M0 decreasing to 0.665 for M20), while mixes with SP maintained acceptable compatibility. This suggests that at high MK replacement levels, adjustment of SP dosage or modification of w/b ratio may be required to achieve uniform compaction and minimize entrapped air.

In summary, the revised workability results confirm that MK reduces flowability due to increased water demand and particle packing effects, while the use of a polycarboxylate superplasticizer is essential to counteract these effects—especially in concretes containing lateritic aggregates, which are naturally more water-absorptive and angular than conventional aggregates. These findings align well with trends reported in the literature for both MK-blended and laterized concrete.

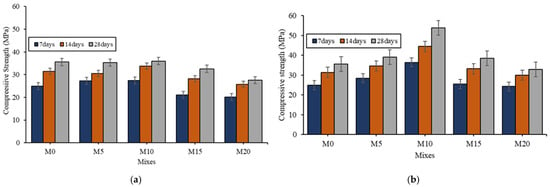

3.3. Compressive Strength Performance

The compressive strength results for all mixes at 7, 14, and 28 days, with and without superplasticizer (SP), are presented in Figure 6. As expected, strength increased with curing age across all mixtures; however, the incorporation of metakaolin (MK) produced notable improvements in both early-age and later-age strengths, with the optimum performance observed at approximately 10% MK replacement. The superplasticized M10 mix achieved a 28-day compressive strength of 53.9 MPa, representing a 51.7% improvement relative to the control (35.6 MPa). A key point requiring clarification is the increase in early-age (7-day) strength at 5% and 10% MK replacement. While pozzolanic reactions typically contribute more significantly after 28 days, the enhanced early-age performance observed in this study is attributable primarily to physical mechanisms associated with the characteristics of the metakaolin used. The MK employed in this research exhibited a very high specific surface area (15,000 m2/kg) and a highly amorphous structure. These properties promote two well-documented mechanisms:

Figure 6.

Compressive strength of mixes with varying MK content: (a) without SP; (b) with SP.

(i) Nucleation (seeding) effect: Ultrafine metakaolin particles provide additional nucleation sites for C–S–H formation, accelerating clinker hydration and resulting in higher early-age strength. Previous studies have demonstrated that highly reactive calcined clays and fine pozzolanic materials can significantly accelerate hydration kinetics through this mechanism, even before substantial pozzolanic activity develops [75,76].

(ii) Filler and packing effects: Due to their ultrafine particle size, MK particles fill microvoids within the cement paste and interfacial transition zone (ITZ), reducing early capillary porosity and improving particle packing. This densification enhances early mechanical strength independent of pozzolanic reactions. Similar effects have been reported for other supplementary cementitious materials—including agricultural ashes such as avocado peel ash—where improved packing and refined pore structure contribute to increased early-age strength [77,78].

These physical mechanisms explain why the 7-day strengths of the 5% and 10% MK mixes exceeded those of the control, even though pozzolanic contributions become more significant at later curing ages. At 14 and 28 days, both physical densification and pozzolanic reactions act synergistically, resulting in further strength enhancement. The pozzolanic reaction between MK’s amorphous silica/alumina and calcium hydroxide produces additional C–S–H and C–A–S–H gels, contributing to a denser matrix and improved ITZ, consistent with established literature [15,79]. Beyond the optimum 10% MK content, compressive strength declined for both early and later ages. This reduction is attributed to cement dilution, increased water demand, and reduced workability at higher MK dosages, which can lead to incomplete compaction and higher porosity—patterns widely reported in MK-blended concretes. Without corresponding adjustments to SP dosage or w/b ratio, the benefits of MK are offset by these negative effects when the replacement level exceeds 15%. Overall, the revised compressive strength results confirm that an MK replacement level of approximately 10% provides the most effective balance between early hydration acceleration, pore refinement, and pozzolanic strengthening, leading to substantial improvements in laterite rock concrete performance.

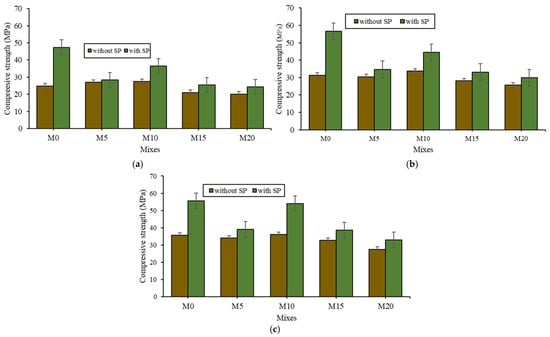

These mechanisms collectively explain why the early-age strengths for the 5% and 10% MK mixes were higher than the control and why this behavior, although seemingly inconsistent with some studies, aligns well with research involving highly reactive MK and well-optimized mixtures. In contrast, studies reporting delayed early strength typically involve coarser MK, lower amorphous content, or higher replacement levels that reduce available clinker. Beyond 10% MK, compressive strength declined at both early and later ages. This reduction is attributed to cement dilution, increased water demand, and incomplete compaction at higher MK contents—a trend widely documented in MK literature [16,80]. Without sufficient SP dosage adjustment, the higher fineness and surface activity of MK at ≥15% replacement lead to increased porosity and reduced hydration efficiency. Overall, the compressive strength results confirm that 10% MK provides an optimal balance of hydration acceleration, pore refinement, and pozzolanic contribution, resulting in enhanced early and later-age strength in laterite rock concrete. Figure 7 shows the compressive strength vs. MK content at fixed ages: (a) 7, (b) 14, and (c) 28 days.

Figure 7.

Compressive strength vs. MK content at fixed ages: (a) 7 days; (b) 14 days; (c) 28 days.

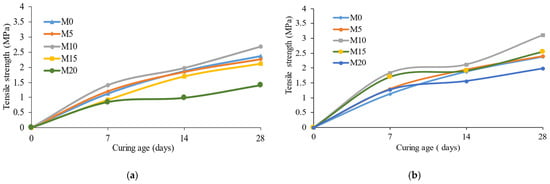

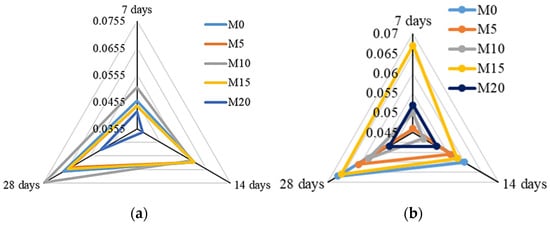

3.4. Tensile Strength of the Laterite Rock Concrete Mixes

The split tensile strength of the laterite rock concrete mixes was determined in accordance with ASTM C496 [67], using cylindrical specimens (150 mm × 300 mm). Tests were performed at curing ages of 7, 14, and 28 days, both with and without SP. The split tensile strength (Figure 8) exhibits a trend similar to that of the compressive strength. All the mixes gained strength with curing time, reflecting continued hydration and pozzolanic activity. The maximum tensile strength was achieved at a 10% MK replacement, recording 2.7 MPa (without SP) and 3.1 MPa (with SP) at 28 days—an increase of approximately 30.7% compared with the control mix (2.4 MPa). Beyond this level, the tensile strength gradually declined, particularly for the 20% MK mix. The improvement in the tensile performance can be attributed to the enhanced interfacial bonding between the laterite aggregate and cementitious matrix [81]. Fine MK particles fill the voids and refine the ITZ microstructure, which is typically the weakest zone in conventional concrete. This refinement effect is particularly beneficial in laterite rock concrete, where the aggregate surface is more porous and irregular. The pozzolanic reaction of MK consumes calcium hydroxide, producing an additional C–S–H gel that strengthens the bond between the paste and aggregate, thereby improving tensile resistance and crack propagation control. The ratios of ratios ranged between 0.038 and 0.075, which is consistent with typical values reported for normal-weight concrete (0.05–0.08). The highest ratio (0.075) was observed for the 10% MK mix at 28 days without SP, indicating a more balanced tensile and compressive performance. The addition of SP slightly modified these ratios because it affected the microstructural uniformity and curing efficiency. At higher MK contents (≥15%), the decline in tensile strength corresponds to increased porosity and potential microcracking caused by inadequate workability and incomplete compaction. This confirms that the overreplacement of cement with MK can compromise paste cohesiveness, especially when the water or admixture dosage is not adjusted accordingly. The results demonstrate that moderate MK incorporation (≈10%) enhances the tensile capacity and bonding efficiency of laterite rock concrete, thereby improving its resistance to cracking and extending its service life. This finding reinforces the role of MK as a high-reactivity pozzolan capable of compensating for a weaker ITZ that is typically associated with lateritic aggregates.

Figure 8.

Split tensile strength of laterite rock concrete: (a) Without SP; (b) With SP.

3.5. Flexural Strength Characteristics

The flexural strength is a crucial measure of concrete resistance to cracking under bending stress and serves as an indicator of its tensile performance and microstructural integrity. In this study, the flexural strength was determined using the three-point loading method on prism specimens measuring 100 mm × 100 mm × 500 mm, following the procedure outlined in ASTM C78 [68] Tests conducted at curing ages of 7, 14, and 28 d for all mixes, both with and without SP. Although the numerical results are not tabulated here for brevity, the flexural strength trends followed those observed in the compressive and split tensile strength tests. The control mix (M0) exhibited a 28-day flexural strength of approximately 4.7 MPa, whereas the incorporation of 10% MK (M10) produced the highest value of about 6.5 MPa in the superplasticized mix. This corresponds to an improvement of nearly 38% compared to the control. At higher replacement levels (≥15%), a gradual decrease in flexural performance was observed, consistent with the reduction in compressive and tensile strengths. The enhancement in flexural strength at moderate MK levels can be attributed to the combined effects of pozzolanic activity and microfilling action, which improve the matrix continuity and interfacial adhesion between the paste and the lateritic aggregate. The formation of an additional C–S–H gel densifies the matrix, reducing voids and microcracks, which typically initiates flexural failure. Furthermore, the improved ITZ contributed to improved stress transfer between the aggregate and cement paste, thereby enhancing the overall bending resistance of the composite.

Mixes containing SP consistently outperformed their non-superplasticized counterparts at all MK levels. This improvement stems from the improved dispersion of cement and metakaolin particles, reduced water demand, and more effective hydration, all of which contribute to a refined and homogeneous microstructure. Conversely, at higher MK contents, the excessive replacement of cement led to a deficiency in the available calcium hydroxide for the pozzolanic reaction, resulting in a reduction in the cohesive strength and explaining the observed decrease in the flexural capacity. The ratio of the flexural strength to the compressive strength for the optimized mix (M10 with SP) was approximately 0.12, which is consistent with the reported values for high-performance concrete incorporating MK. This ratio indicates an improved stress-transfer capability and enhanced ductility compared to conventional lateritic concrete, which typically exhibits ratios of 0.08–0.10. The results confirmed that the partial replacement of cement with approximately 10% MK significantly improved the flexural performance of laterite rock concrete. This improvement was mainly attributed to pore refinement, ITZ densification, and secondary C–S–H formation, which collectively enhanced the load-carrying capacity and crack resistance of the composites. Beyond this optimum level, the adverse effects of reduced cementitious content and workability limitations outweigh the benefits of additional pozzolanic materials.

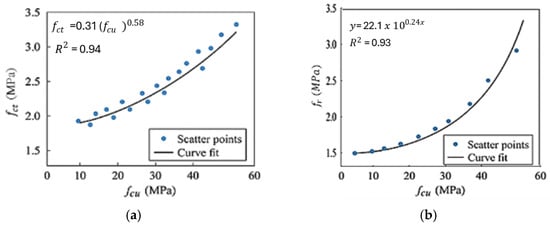

3.6. Correlation of Mechanical Properties and Microstructural

To establish the relationships among the key mechanical parameters of the metakaolin-blended laterite rock concrete, the experimental results of the compressive strength , split tensile strength and flexural strength were analyzed. The purpose was to evaluate how the inclusion of MK modifies strength interdependence and provides empirical correlations that are useful for mix design and predictive modeling.

3.6.1. Correlation Between Compressive and Tensile Strengths

A close relationship is observed between the compressive and split tensile strengths at all curing ages and replacement levels. The results exhibit an approximate power-law relationship for the form shown in Equation (2).

where k and n are empirical constants. Regression analysis yielded k ≈ 0.30 and n ≈ 0.60, values consistent with those reported for normal-weight concrete. The ratio ranged between 0.05 and 0.075, which is slightly higher than that of conventional concrete owing to the improved interfacial bonding and reduced porosity resulting from metakaolin addition. This indicates that MK not only enhances compressive strength, but also proportionally increases the tensile capacity of the material, which is an important characteristic for structural applications where cracking resistance is critical (Figure 9a).

Figure 9.

Determination of Correlation Regression coefficients (R): (a) Compressive and Tensile Strengths (b). Compressive and Flexural Strengths.

3.6.2. Correlation Between Compressive and Flexural Strengths

The relationship between compressive and flexural strengths also followed a nonlinear trend, as described in Equation (3).

with a ≈ 0.63 and b ≈ 0.53. The 10% MK mix (M10 with SP) displayed the best correlation, showing a consistent improvement in both parameters. The increase in relative to suggests enhanced stress transfer efficiency and improved ductility of the MK-modified matrix (Figure 9b).

The flexural-to-compressive strength ratio reached 0.12 at the optimum MK content, compared with 0.09 of the control mix, confirming that the pozzolanic and filler effects of MK refined the microstructure and strengthened the ITZ (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Ratio of split tensile to compressive strength : (a) against curing age for samples without SP; (b) against curing age for samples with SP.

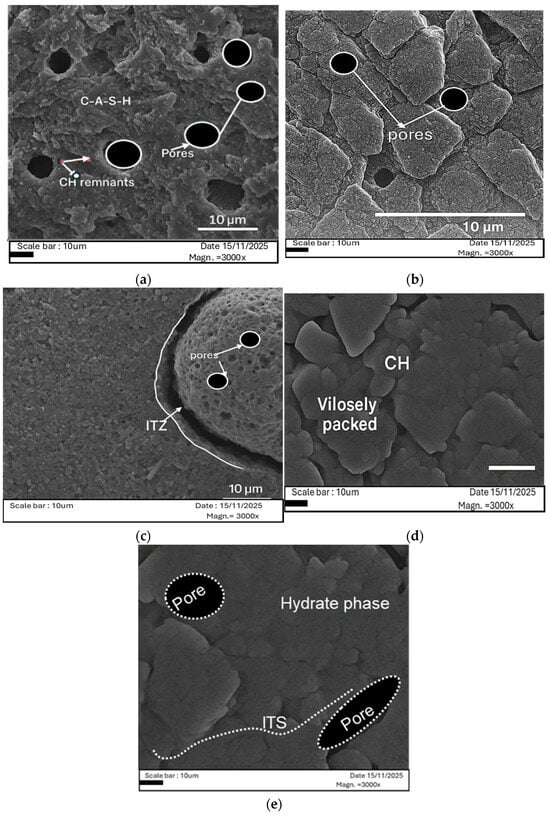

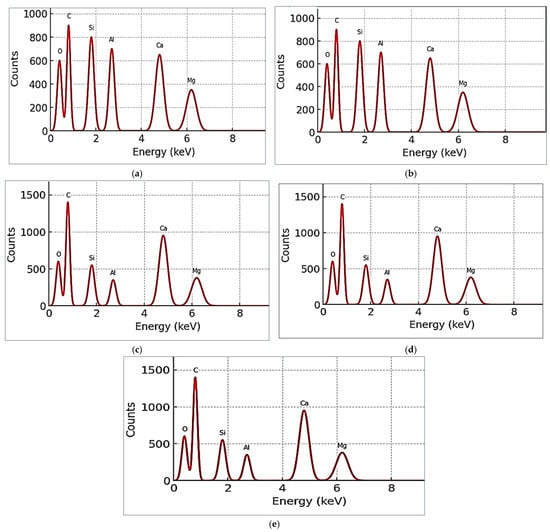

3.6.3. SEM–EDS Microstructural Analysis of Concrete Mix

SEM–EDS analysis was performed on fractured surfaces of selected specimens to elucidate the influence of metakaolin (MK) on the hydrated cement paste and the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between the paste and laterite rock aggregate. Representative samples from the control mix (M0) and optimum metakaolin mix (M10 with SP) were examined. These observations provide microstructural evidence that supports the mechanical performance trends (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Concrete mix of concrete mix; (a) SEM of concrete without superplasticizers at control mix 0% without superplasticizer; (b) SEM analysis of concrete mix with superplasticizers at concrete mix-5%; (c) SEM of concrete with superplasticizers at optimum concrete mix-10%; (d) SEM analysis of concrete mix with superplasticizers of concrete mix-15; (e) SEM analysis of concrete mix with superplasticizers of concrete mix-20%.

In the control mix, the bulk paste microstructure displayed a relatively heterogeneous morphology with distinct plate-like calcium hydroxide (CH) crystals embedded in a C–S–H matrix. Numerous capillary pores and microcracks were observed, particularly close to the aggregate surface. The ITZ around the laterite rock appeared as a relatively porous band, characterized by loosely packed hydration products and visible voids. This microstructural weakness was consistent with the moderate compressive and tensile strengths of the control concrete.

By contrast, the MK-blended paste (M10 with SP) exhibited a significantly denser and more homogeneous microstructure. The SEM images revealed a compact, gel-like C–S–H matrix with fewer visible microcracks and reduced capillary porosity. Distinct CH crystals were less prevalent, indicating that a substantial portion of portlandite was consumed by the pozzolanic reactions with MK. In some regions, fine MK-derived reaction products appeared as tightly packed, amorphous clusters intimately integrated into the surrounding C–S–H, suggesting the effective nucleation and growth of secondary hydration products. The ITZ in the M10 specimens showed marked refinement compared with that in the control. Instead of a wide porous boundary zone, the paste in direct contact with the laterite aggregate appeared more continuous and compact, with hydration products penetrating the surface irregularities and pores of the laterite. This resulted in a stronger mechanical interlock and reduced the contrast between the ITZ and the bulk matrix. The visual densification of the ITZ correlates well with the enhanced split tensile and flexural strengths, as improved paste–aggregate bonding delays the crack initiation and propagation under loading.

EDS point analyses and elemental mapping further clarified the effect of the MK on the chemical composition of the paste. In the control mix, the spectra obtained from the bulk paste and ITZ were dominated by Ca and Si, with a relatively high Ca/Si atomic ratio, typical of conventional OPC systems rich in portlandite (Figure 12). In the MK-modified paste, the Ca/Si ratio tended to be lower, reflecting the formation of a more silica-rich C–S–H gel and partial consumption of CH. In addition, elevated Al and Fe signals were detected locally in the MK-blended paste and ITZ. The increased Al content is associated with the formation of C–A–S–H-type phases derived from the reaction of MK’s aluminosilicate structure of MK with calcium hydroxide, while Fe is primarily linked to the lateritic aggregate and its interaction with the surrounding paste. Elemental maps around the laterite–paste interface in the M10 mix indicated a more uniform distribution of Si, Al, and Ca across the ITZ compared to the control, where sharp gradients and a more distinct CH-rich band were observed. This more homogeneous distribution of key elements in the MK-modified concrete supports the notion of a chemically and physically integrated ITZ in contrast to the relatively weak and discontinuous zones in the reference mix. The presence of Al-rich gels bridging the aggregate and paste likely contributed to the improved load transfer and enhanced ratios of and reported earlier.

Figure 12.

EDS results show the concrete mix: (a) EDS spectrum of the control mix (0% without superplasticizer); (b) EDS spectrum of the concrete mix (5% superplasticizer); (c) EDS spectrum of the optimum concrete mix (10% superplasticizer); (d) EDS spectrum of the concrete mix (15% superplasticizer); (e) EDS spectrum of the concrete mix (20% superplasticizer).

Overall, the SEM–EDS results confirm that metakaolin addition promotes microstructural densification of both the bulk paste and ITZ in laterite rock concrete. The refinement of the pore structure, reduction in free CH, and formation of additional C–S–H/C–A–S–H phases collectively explain the significant gains in the compressive, tensile, and flexural strengths at the optimum 10% replacement level. These microstructural findings provide a mechanistic basis for the observed macroscopic performance and reinforce the suitability of MK as a high-reactivity SCM for sustainable laterite-rock concrete.

3.6.4. Impact on Sustainability and CO2 Reduction

From a sustainability perspective, the partial replacement of OPC with MK reduces clinker content, thereby lowering the associated CO2 emissions. Considering that the production of one tonne of cement emits roughly one tonne of CO2, replacing 10% of the cement with MK in the present mix design translates to an estimated 10% reduction in embodied carbon for equivalent structural strength. Additionally, the use of locally available laterite rock as a coarse aggregate minimizes the need for quarried granite, reducing both the transportation energy and cost.

Thus, the combined use of metakaolin and laterite rock not only improves the mechanical performance of concrete but also offers a regionally adaptable and eco-efficient construction solution for tropical and developing regions. The established correlations among the strength parameters can serve as a foundation for optimizing the mixed proportions in future studies focusing on structural-grade sustainable concrete.

3.7. Comparative Discussion with Previous Studies on Lateritic Aggregates and Metakaolin and with Other SCMs

The mechanical performance trends observed in this study are consistent with, yet extend beyond, the findings of earlier research on both lateritic aggregates and metakaolin-blended concretes. Previous studies on laterized concrete [45,46] reported that lateritic aggregates tend to reduce workability and can moderately decrease compressive strength when used without binder modification. In those works, the reduction in strength was attributed to the porous microstructure and angularity of laterite, which typically results in a weaker interfacial transition zone (ITZ). The present study demonstrates that incorporating metakaolin at an optimal 10% replacement addresses this limitation by refining the ITZ and enhancing paste–aggregate bonding, resulting in significantly higher compressive, tensile, and flexural strengths than those reported for unmodified laterized concretes. Thus, the synergy between MK and laterite rock improves the mechanical performance beyond what is achievable with lateritic aggregates alone.

With respect to metakaolin, the strength improvements observed in this study are comparable to those reported in previous works on MK–OPC systems. Studies such as [9,63,82] consistently show that MK replacement levels between 5% and 15% produce the greatest strength enhancement. The optimal 10% MK level observed here aligns with these findings, further demonstrating that MK’s combination of filler, nucleation, and pozzolanic mechanisms operates effectively even in concrete containing lateritic coarse aggregates. Notably, earlier works have focused largely on concretes made with conventional siliceous aggregates (granite, basalt, river gravel). The present study extends this knowledge by showing that MK’s microstructural benefits are particularly impactful when the aggregate is porous and iron rich, as in laterite rock, where the ITZ is naturally weaker.

It is also relevant to compare the present results with studies involving other cement replacement materials such as ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) and fly ash (FA). Both GGBFS and FA are well-established supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) known to improve durability and long-term strength; however, they typically exhibit slower early-age strength development because their pozzolanic or latent hydraulic reactions are less reactive at ambient temperatures. For example, concretes incorporating 20–40% FA commonly show reduced 7-day strengths and only surpass control concretes at later curing ages. Similarly, GGBFS-blended concretes may require higher curing temperatures or activators to achieve rapid early strength. In contrast, the metakaolin used in this study produced substantial early-age strength gains (7 days), owing to its high fineness and highly amorphous aluminosilicate structure, which accelerate hydration through seeding and packing effects. This distinguishes MK from FA and GGBFS, whose early-age performance is typically inferior to that of the control mix.

Furthermore, the magnitude of strength enhancement observed here at 10% MK exceeds that typically reported for FA or GGBFS at similar replacement levels. While FA or GGBFS blends may show 10–25% increases in 28-day strength, the MK-enhanced laterite rock concrete in this study achieved a 51.7% increase. This suggests that MK is a more effective SCM for strength-critical applications in regions where lateritic aggregates are prevalent, particularly when early-age strength is required. The present study demonstrates that metakaolin not only mitigates the mechanical disadvantages associated with lateritic aggregates but also outperforms more traditional SCMs such as fly ash and GGBFS in early-age and later-age strength development. These findings support the adoption of MK-enhanced laterite rock concrete as a regionally adaptable, high-performance, and sustainable construction solution for tropical environments.

4. Conclusions

This study examined the mechanical and sustainability performance of laterite rock concrete in which ordinary Portland cement (OPC) was partially replaced with metakaolin (MK) at levels of 0–20% by mass of binder, using a constant water–binder ratio of 0.50. The results demonstrate that MK is an effective supplementary cementitious material for laterite rock concrete, provided that its dosage and the use of chemical admixtures are properly optimized. The incorporation of MK reduced the workability of fresh concrete because of its high fineness and specific surface area, leading to increased water demand and stiffer mixes. However, the use of a polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer successfully restored and, in some cases, enhanced workability, achieving collapse slumps for mixes containing up to 10% MK. This confirms that workability challenges associated with MK can be effectively mitigated through appropriate admixture selection and dosage. In terms of mechanical performance, all mixes showed strength gains with curing age, but the most significant improvements occurred at approximately 10% MK replacement. At this optimum level, the 28-day compressive strength increased from 35.6 MPa (control) to 53.9 MPa in the superplasticized mix, representing an enhancement of about 51.7%. The corresponding split tensile and flexural strengths also improved, reaching 3.11 MPa and 6.5 MPa, respectively. Although higher MK contents (≥15%) still produced strengths comparable to or slightly above the control, a gradual decline in performance was observed, mainly due to cement dilution and reduced workability, which can lead to incomplete compaction and increased porosity. Strong empirical correlations were established between compressive, tensile, and flexural strengths, with in the range of 0.05–0.075 and ≈ 0.12 at the optimum MK dosage. These ratios indicate a balanced improvement in tensile and flexural performance relative to compressive strength, which is essential for crack control and serviceability in structural elements. SEM–EDS analysis provided microstructural evidence supporting these trends: the MK-modified mixes exhibited a denser, more homogeneous matrix with reduced portlandite content, refined pore structure, and a significantly improved interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between the paste and laterite rock aggregate. From a sustainability standpoint, partial replacement of OPC with MK directly reduces clinker content and associated CO2 emissions. A 10% MK replacement corresponds to an approximate 10% reduction in clinker-related emissions for concretes of equivalent strength class. In addition, the use of locally available laterite rock as a coarse aggregate reduces dependence on quarried granite and lowers transportation impacts. Thus, MK-enhanced laterite rock concrete offers both performance and environmental benefits, making it a promising, regionally adaptable solution for structural applications in tropical developing regions. Overall, the findings show that metakaolin-modified laterite rock concrete can achieve higher strength, improved microstructural integrity, and enhanced eco-efficiency without requiring major changes to conventional mix design or curing practices. An MK replacement level of around 10%, combined with appropriate superplasticizer use, is recommended as an optimum for structural-grade laterite rock concrete.

5. Limitations and Future Work

Although this study demonstrates the mechanical, microstructural, and sustainability benefits of incorporating metakaolin (MK) in laterite rock concrete (LRC), several limitations should be acknowledged, and opportunities remain for further research.

5.1. Limitations

- Single Water–Binder Ratio and Curing Condition: The experiments were conducted using a fixed water–binder ratio of 0.50 and standard water curing at 27 ± 2 °C. Alternative curing environments—such as steam curing, accelerated curing, or variable tropical ambient conditions—and lower w/b ratios were not explored but could influence both early-age and long-term performance.

- Material Source Variability: The laterite rock and kaolinitic clay used to produce MK came from specific local sources. Because laterite materials vary widely in mineralogy, porosity, and iron/aluminum content across regions, the findings may not be universally generalizable without additional validation.

- Limited Evaluation of Chemical Admixtures: Only one type of polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer was used. MK interacts differently with various admixtures, and dosage optimization was not systematically studied. Air-entraining agents, retarders, or viscosity modifiers were also not evaluated.

- Scope of Durability Assessment The study focused primarily on mechanical properties and microstructure. Durability parameters—such as permeability, chloride ingress, sulfate resistance, shrinkage, carbonation depth, or freeze–thaw performance—were not assessed.

- Simplified CO2 Reduction Estimate The sustainability analysis relied on theoretical clinker-replacement calculations. A complete life-cycle assessment (LCA), including transportation energy, calcination energy for MK production, and potential long-term durability benefits, was not performed.

5.2. Future Work

- Broader Mix Design Optimization: Future studies should investigate different water–binder ratios, binder contents, and aggregate gradations. Optimization frameworks such as response surface methodology (RSM) or machine learning models may offer systematic mix proportioning strategies.

- Evaluation of Additional Durability Indicators: Long-term performance tests—such as drying shrinkage, creep, chloride penetration, sulfate attack, acid resistance, water absorption, and freeze–thaw cycling—are essential to establish the suitability of MK–LRC for infrastructure exposed to harsh environments.

- Regional Material Variability Studies: Since laterite deposits differ significantly across Africa, Asia, and South America, future research should examine MK-modified laterite rock concretes using materials from multiple geographical sources to develop more generalizable design recommendations.

- Admixture Compatibility and Optimization: The interaction of MK with other chemical admixtures and varying superplasticizer dosages should be studied. This includes rheology characterization and dispersion behavior to address workability challenges at higher MK levels.

- Hybrid Binder Systems and Multi-SCM Blends: Combining metakaolin with other SCMs—such as limestone powder, rice husk ash, volcanic ash, or ground granulated blast-furnace slag—may further enhance strength and sustainability, especially in regions with limited access to industrial SCMs.

- Comprehensive Life-Cycle and Cost Assessments (LCAs): Full LCAs and cost–benefit analyses are needed to quantify the environmental and economic feasibility of MK–LRC at scale, considering energy input, material sourcing, transport distance, and long-term durability impacts.

- Structural Element Testing: Beyond laboratory specimens, future work should investigate MK–LRC in reinforced beams, slabs, and columns to evaluate load-bearing behavior, cracking patterns, ductility, and long-term serviceability under real structural conditions.

Author Contributions

U.U.I., Writing–original draft, formal analysis, and investigation. M.H., Conceptualization, Formal analysis, and investigation. S.C.K., Methodology and Validation. A.J.B., Supervision, Review, and editing. R.H., Writing–original draft and formal analysis. M.M.R., Writing, review, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are included in the article. Further details are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this study.

Abbreviations

| OPC | Ordinary Portland Cement |

| MK | Metakaolin |

| SCM | Supplementary Cementitious Material |

| LRC | Laterite Rock Concrete |

| w/b | Water–Binder Ratio |

| SP | Superplasticizer |

| C–S–H | Calcium Silicate Hydrate |

| C–A–S–H | Calcium Aluminosilicate Hydrate |

| CH | Calcium Hydroxide (Portlandite) |

| ITZ | Interfacial Transition Zone |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy/Microscope |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| LCA | Life-Cycle Assessment |

| LOI | Loss on Ignition |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| MPa | Megapascal |

| PSD | Particle Size Distribution |

| FA | Fly Ash |

| GGBFS | Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag |

References

- Shaikh, S.A.; Rajpurohit, K.; Pandey, A.K.; Bagla, H.K. Engineering Portland Cement and Concrete with Agricultural-Origin Functional Additives: Valorization of Agro-Waste. Next Sustain. 2025, 6, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, P.; Gogineni, A.; Ahmed, M.; Chen, W. Evolution of Cementitious Binders: Overview of History, Environmental Impacts, and Emerging Low-Carbon Alternatives. Buildings 2025, 15, 3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippiatt, N.; Ling, T.-C.; Pan, S.-Y. Towards Carbon-Neutral Construction Materials: Carbonation of Cement-Based Materials and the Future Perspective. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 28, 101062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisciotta, M.; Pilorgé, H.; Davids, J.; Psarras, P. Opportunities for Cement Decarbonization. Clean Eng. Technol. 2023, 15, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ige, O.E.; Kabeya, M. Decarbonizing the Cement Industry: Technological, Economic, and Policy Barriers to CO2 Mitigation Adoption. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, Z.F.; Guler, S.; Yavuz, D.; Avcı, M.S. Toward Sustainable Construction: A Critical Review of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Properties and Future Opportunities. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ige, O.E.; Moloi, K.; Kabeya, M. Sustainability Assessment of Cement Types via Integrated Life Cycle Assessment and Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Methods. Sci 2025, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.A.; Habert, G.; Myers, R.J.; Harvey, J.T. Achieving Net Zero Greenhouse Gas Emissions in the Cement Industry via Value Chain Mitigation Strategies. One Earth 2021, 4, 1398–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, B.B.; Wild, S.; Bai, J. Metakaolin and Calcined Clays as Pozzolans for Concrete: A Review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2001, 23, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weise, K.; Ukrainczyk, N.; Koenders, E. Pozzolanic Reactions of Metakaolin with Calcium Hydroxide: Review on Hydrate Phase Formations and Effect of Alkali Hydroxides, Carbonates and Sulfates. Mater. Des. 2023, 231, 112062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Wang, H. Recent Progress of Utilization of Activated Kaolinitic Clay in Cementitious Construction Materials. Compos. B Eng. 2021, 211, 108636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marandi, N.; Shirzad, S. Sustainable Cement and Concrete Technologies: A Review of Materials and Processes for Carbon Reduction. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2025, 10, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.M.; Tayeh, B.A. Metakaolin in Ultra-High-Performance Concrete: A Critical Review of Its Effectiveness as a Green and Sustainable Admixture. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-Y. Analysis of Hydration-Mechanical-Durability Properties of Metakaolin Blended Concrete. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, C.-S.; Lam, L.; Kou, S.C.; Wong, Y.-L.; Wong, R. Rate of Pozzolanic Reaction of Metakaolin in High-Performance Cement Pastes. Cem. Concr. Res. 2001, 31, 1301–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. High performance concrete having silica fume and metakaolin as a limited replacement of cement. J. Mech. Contin. Math. Sci. 2020, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, W.O.; Adekunle, S.K.; Ahmad, S.; Amao, A.O.; Sajid, M. Compressive Strength Evolution of Concrete Incorporating Hyperalkaline Cement Waste-Derived Portlandite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 358, 129426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Abbas, Y.M.; Fares, G. Enhancing Cementitious Concrete Durability and Mechanical Properties through Silica Fume and Micro-Quartz. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsebaei, M.; Mavroulidou, M.; Micheal, A.; Centeno, M.A.; Shamass, R.; Rispoli, O. Dealuminated Metakaolin in Supplementary Cementitious Material and Alkali-Activated Systems: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madirisha, M.M.; Dada, O.R.; Ikotun, B.D. Chemical Fundamentals of Geopolymers in Sustainable Construction. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 27, 100842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, H.; Shoukry, H.; Abadel, A.A.; Khawaji, M. Performance Assessment of Limestone Calcined Clay Cement (LC3)-Based Lightweight Green Mortars Incorporating Recycled Waste Aggregate. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 2065–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, M.; Ladduri, B.; Alloul, A.; Benzerzour, M.; Abriak, N.-E. Geopolymer Synthesis and Performance Paving the Way for Greener Building Material: A Comprehensive Study. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taborda-Barraza, M.; Tambara, L.U.D.; Vieira, C.M.; de Azevedo, A.R.G.; Gleize, P.J.P. Parametrization of Geopolymer Compressive Strength Obtained from Metakaolin Properties. Minerals 2024, 14, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Zheng, K.; Sun, F.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, T.; Colombo, P.; Wang, B. A Review on Metakaolin-Based Porous Geopolymers. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024, 258, 107490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, H.; Salem, T.; Djerbi, A.; Dujardin, N.; Gautron, L. Durability and Hygrothermal Performance of Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer Composites Reinforced with Hemp Shiv and Miscanthus Fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 494, 143461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa Ribeiro, R.A.; Sa Ribeiro, M.G.; Samuel, D.M.; Ozer, A.; Numkiatsakul, P.; Kriven, W.M. Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer Matrix Formulations for Higher Strength and Thermal Stability. Mater. Struct. 2025, 58, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borçato, A.G.; Thiesen, M.; Medeiros-Junior, R.A. Mechanical Properties of Metakaolin-Based Geopolymers Modified with Different Contents of Quarry Dust Waste. Constr. Build. Mater 2023, 400, 132854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaif, A.; Albidah, A.; Abadel, A.; Abbas, H.; Al-Salloum, Y. Development of Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer Rubberized Concrete: Fresh and Hardened Properties. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2022, 22, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelin Lincy, G.; Velkennedy, R. Investigation on the Flexural Behavior of Reinforced Geopolymer Concrete Slabs Incorporating Metakaolin and Nano-silica Composite. Struct. Concr. 2025, 26, 3517–3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]