Abstract

The canyon hilly terrain of northwestern China significantly influences wind field characteristics within the grotto zone, consequently affecting the degree of wind erosion on grotto heritage. In the present study, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) numerical simulations were employed to investigate the effects of mountain length, slope, and spacing on the wind field characteristics of a typically canyon hilly terrain, with the Xumishan Grottoes as a case study. The results show a significant wind speed acceleration at canyon entrances and summits. Variations in mountain length and slope non-linearly affect wind field distribution, with wind speeds at the side and summit stabilizing when the mountain length exceeds three times the mountain height (L ≥ 3H). Based on the simulation results, an improved acceleration ratio formula incorporating mountain length, slope, and spacing was proposed, which demonstrated a discrepancy of only 9.05% compared with the field-validated CFD results for Cave 5 at Xumishan. This study elucidates the wind field formation mechanisms in canyon hilly terrain and provides a scientific basis for addressing the stone carving erosion of grotto heritage, contributing to the advancement of preventive conservation strategies for grottoes in complex terrains.

1. Introduction

Northwestern China is characterized by a typical continental climate, where frequent strong winds result in wind erosion as the predominant form of deterioration for stone carvings [1]. Grottoes in this region, often situated in canyon hilly terrain, are susceptible to accelerated wind speeds caused by airflow channeling effects [2]. Because the erosion process is governed primarily by the average wind speed [3,4,5], the rock mass of stone carvings undergoes continuous impact and abrasion under strong wind.

Numerous studies have investigated the impact of site-specific wind environments on ruins and heritage sites. Chen [6] investigated the optimization of urban ventilation in Zhao’an Old Town, Fujian, through the integration of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations and field measurements. Grau-Bové [7] reviewed the application of computational fluid dynamics in heritage interpretation and protection. Li [8] demonstrated that a windbreak forest can reduce the wind amplification coefficient in a grotto zone, thereby effectively mitigating the wind erosion of local grotto heritage. Through field wind tunnel experiments, Zhang [9] elucidated the dust emission process from the Gobi surface of the Mogao Caves, noting that variations in the external sand source supply alter the conversion between wind deposition and erosion on gravel beds. Tan [10] explored the deceleration efficacy of various gravel covers under differing wind speed, showing that the wind-reducing effect of each gravel layer intensified with increasing wind speed. Pineda [11] proposed a CFD method to analyze sand-induced erosion on heritage sites, which is particularly applicable in cases where a particulate flow is a dominant erosion factor. Although the existing research provides an effective analysis of the influence of site-specific wind environments on ruins and heritage sites, the formation mechanisms of wind fields within the canyon hilly terrain surrounding grotto heritage sites remain insufficiently explored.

Wind field characteristics within the atmospheric boundary layer are influenced by factors including surface type [12,13,14,15], vegetation distribution [16,17,18], and convective conditions [19,20]. For instance, Blocken [12] demonstrated, through CFD validations with field measurements, that complex terrain significantly alters local flow patterns, emphasizing the need for terrain-resolved simulations in wind environment studies. As reviewed by Buccolieri [17], vegetation not only affects aerodynamic roughness but also modifies turbulent structures. Furthermore, non-neutral atmospheric conditions driven by thermal effects, as investigated by Cheynet [19], can alter wind speed and direction profiles over complex terrain. Meanwhile, the flow within this layer is highly complex, particularly in areas of significant topographic relief like mountains, where the local wind environment differs markedly from that over flat terrain. This complexity result in phenomena such as local wind speed acceleration [21], alterations in the average wind speed [22] and turbulence intensity [23], and flow separation and reattachment [24]. Cao [25] conducted research on the turbulent boundary layer above a two-dimensional hill using a large eddy simulation, and the simulation showed that large-scale separation phenomena would form on the leeward side of the steep hill. Yu [26] explored how terrain and morphology influence incoming wind characteristics, with experimental results indicating that rough terrain leeward of a mountain yields a smaller recirculation zone and a closer reattachment point downstream. Chen [27] comprehensively evaluated hilly terrain wind characteristics, finding pronounced site-to-site variability. Uchida [28] performed numerical simulations for an isolated mountain under stable atmospheric conditions, demonstrating that flow patterns resembling potential flow emerge around the mountain irrespective of changes in its inclination angle. Unlike two-dimensional models, which assume infinite length and neglect lateral flow effects, the three-dimensional canyon model captures acceleration patterns with both longitudinal and lateral variation, particularly at canyon entrances and summits. This distinction is crucial for accurately predicting the local wind speed ratios of heritage structures situated in discrete terrain locations. Although wind flow over idealized terrain has been widely studied in wind engineering, heritage sites within complex, canyon-formed terrain present a unique combination of topographic parameters whose influence on local wind acceleration and erosion patterns is not fully captured by classical two-dimensional or isolated mountain models.

To quantitatively analyze the influence of canyon hilly terrain on wind fields, the acceleration ratio is commonly used [29]. Since the 1970s, numerous scholars have investigated mountain acceleration effects, proposing various algorithms. Among these, the model proposed by Jackson and Hunt [30] is the most widely applied. In contemporary research, terrain correction coefficients are typically introduced to account for the wind speed acceleration effects of canyon hilly terrain. Consequently, accurately calculating the terrain correction coefficient based on measurable terrain characteristics remains a central research challenge. Furthermore, Chinese standards, referencing codes from countries such as Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom, provide formulae for calculating the height variation correction coefficient of wind pressure at the summit for simple two-dimensional ridges and isolated three-dimensional mountains with negligible length [31]. Through a review of the existing literature and the provisions of the Chinese norms, it is found that the current research has the following problems: (1) although multiple terrain parameters influence wind speed, the existing methods consider only slope, neglecting the effects of mountain length and spacing; (2) the existing formulas and standards are limited to two-dimensional models of infinite length or isolated three-dimensional mountains with negligible length. These idealized conditions often mismatch actual terrain, casting doubt on the accuracy of the results.

The study of wind fields has garnered increasing research interest in recent years. The research mainly includes on-site measurements [32,33], wind tunnel testing [34,35,36], and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) numerical simulations [37,38]. On-site measurements yield highly reliable data and are often used to verify the accuracy of numerical simulation results [39]. Wind tunnel testing offers greater flexibility, enabling the collection of wind field parameters under various inflow conditions [40]. Over the past five decades, significant improvements in computational power and the development of commercial software have driven the rapid advancement of numerical simulation methods. Among these, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) has become the most prevalent numerical simulation approach [41]. Compared to on-site and wind tunnel methods, CFD simulations can provide data for any point within the wind field [42]. They also facilitate full-scale simulations without the extensive time investment required for physical model construction [43]. Consequently, numerical simulation, particularly CFD, has emerged as the predominant method for studying wind fields [44].

Mitigating the long-term, intermittent effects of wind erosion necessitates an understanding of the relationship between the grotto zone wind environment and stone carving erosion. Investigating the influence of canyon hilly terrain on the grotto wind environment is fundamental to revealing its formation mechanism. Therefore, to address these limitations and to advance the scientific basis for assessing wind erosion on heritage sites, this study aims to (1) systematically investigate the influence of canyon terrain parameters—specifically length, slope, and spacing—on spatial wind fields using three-dimensional CFD simulations; (2) develop an improved terrain acceleration formula that incorporates the effects of length, slope, and spacing, validated against the case study of the Xumishan Grottoes; (3) provide site-specific wind field data to inform the preventive protection of grotto heritage from wind-induced erosion. This research can explore preventive protection technologies for grotto heritage, thereby contributing to the advancement of scientific conservation research and practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Study Case

The Xumishan Grottoes are situated in Guoyuan, within the Ningxia Region. The site roughly extends from 105°58′46″ to 105°59′21″ E and 36°16′13″ to 36°17′18″ N. Initial excavation of the grottoes occurred during the Northern Wei Dynasty (477–499 CE). The complex presently comprises 162 primary grottoes and over 350 stone carvings. In 1982, the State Council designated the Xumishan Grottoes as a National Key Cultural Heritage Protection Unit, and the site is a candidate for UNESCO World Heritage status. Among these, Cave 5 (Figure 1), located in the Great Buddha Hall area, houses a seated Buddha statue from the Tang Dynasty. This statue is a representative of the Tang Dynasty carvings in the Xumishan Grottoes and one of the few existing large statues from the Tang Dynasty in China.

Figure 1.

Buddha statue in Cave 5.

The Xumishan Grottoes are situated in a typical canyon hilly terrain of northwestern China, a region characterized by complex topographical features—such as variable mountain slopes, lengths, and spacings—that significantly influence local wind fields (Figure 2). This terrain configuration represents a common yet understudied setting in heritage wind environment research, making it an ideal case study for examining how canyon topography affects wind flow and erosion patterns.

Figure 2.

Topographic map of Xumishan Grottoes.

The Xumishan grotto zone is located at the entrance of the canyon mountain. When the airflow moves from the open area into the narrower canyon area, it accelerates through the canyon region, resulting in a significant increase in wind speed within the grotto zone. Furthermore, as most of the grottoes in the Xumishan Grottoes are excavated at mountain summits or on slopes, they are subject to an increased average wind speed due to orographic effects. Consequently, the stone-carved Buddha statues and surrounding rock mass face severe wind erosion. For example, the mountain body and Buddha foot in Cave 5 display honeycomb-like weathering due to wind erosion (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The current wind erosion state of Xumishan Grottoes. (a) Mountain body; (b) Buddha foot.

2.2. Geometry Model

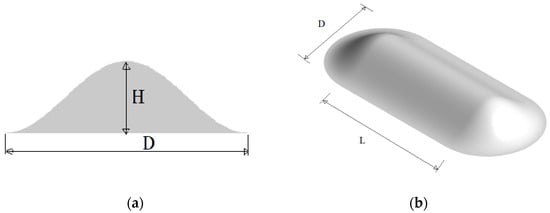

Geometric models are fundamental for accurate numerical simulation. While actual terrain is irregular, employing a parametric cosine-type model facilitates the systematic isolation and analysis of key geometric variables—length (L), slope (S), and spacing (W) [45]. This approach is consistent with established practices in terrain aerodynamics, where simplified geometries serve as a controlled basis for understanding fundamental flow behaviors before applying insights to more complex real-world sites. The cross-sectional function is given by Equation (1):

where H represents the height of the mountain; D represents the diameter of the bottom of the mountain; and the slope (S) of the mountain can be expressed as 2H/D. An isolated mountain with a certain length is composed of two half-cylindrical sections and a straight-line segment with a length of L for the cross-sectional stretching. The isolated mountain model is shown in Figure 4.

y = Hcos2πx/D, x ≤ D/2

Figure 4.

Diagram of isolated mountain model. (a) Cross-section; (b) 3D model.

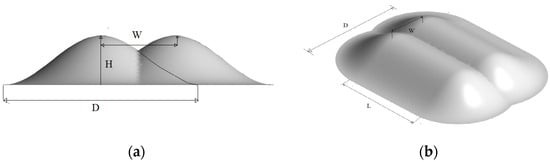

A canyon mountain is formed when the bases of two isolated mountains converge. In this configuration, the spacing (W) between the mountain summits is less than the base length (D). The Xumishan Grottoes are situated at the entrance of such a canyon terrain. Consequently, the wind environment at the site is significantly influenced by this canyon topography. The geometric model for a canyon mountain is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Diagram of canyon mountain model. (a) Cross-section; (b) 3D model.

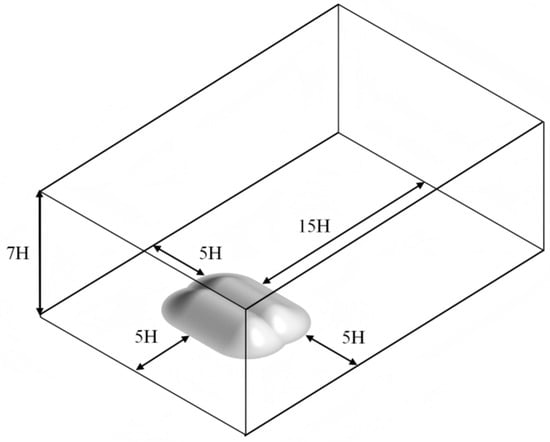

2.3. Calculation Domain and Grid

In this study, the mountain height (H) was uniformly set to 100 m. Different topographic conditions were simulated by varying the mountain length (L), width (D), and spacing (W). A sufficiently large computational domain is essential to allow for full fluid development and to avoid flow compression effects. Following established numerical simulation guidelines [46,47], the domain dimensions were defined relative to H: a height of 7H, with distances of 5H from the model to the inlet and side boundaries and 15H to the outlet boundary. The domain blockage ratio was maintained below 3%. The geometric model and computational domain are illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Computational domains of numerical simulation.

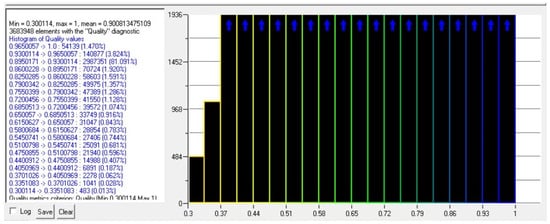

The meshing process was performed using the ANSYS Fluent 19.2 per-processor (ICEM). Prism layer grids were employed near the ground to accurately resolve boundary layer flow conditions. The remainder of the domain was discretized using unstructured tetrahedral cells. A mesh sensitivity analysis was conducted using three schemes (Table 1) to balance numerical accuracy with computational economy, since the medium and fine mesh schemes yielded similar average velocity profiles. Meanwhile, Grid Convergence Index (GCI) calculations confirm grid independence, with values for the medium grid (3.68 million cells) and fine grid (12.36 million cells) at 2.68% and 1.46%, respectively; both values are below the 3% threshold, thereby satisfying the standard GCI criterion [48]. Therefore, the medium scheme (Scheme 2) was deemed sufficient for achieving accurate results and was therefore selected for all subsequent simulations. In this scheme, the base grid size on the mountain surface was 5 m, with a growth factor of 1.05 applied radially outward. The maximum grid size in the domain was constrained to 40 m. In the vertical direction, the grid height of the first prism layer near the ground is set as 0.05 m in accordance with the standard wall function requirements, so the corresponding value of y+ is within the range of 30–300. The total mesh consisted of approximately 3,680,000 cells. The mesh quality was high, with an average value of 0.90 and over 94.74% of cells exceeding a quality threshold of 0.7 (Figure 7). This confirms that the mesh quality across the entire domain is satisfactory for FLUENT calculations.

Table 1.

Meshing schemes.

Figure 7.

Grid quality of the calculation domain.

2.4. Boundary Condition and Solver Settings

The exponential law wind profile was selected as the inlet boundary condition because the computational domain height is comparable to the atmospheric boundary layer height, a condition where the logarithmic law is less applicable [49]. The reference wind speed at a 10 m height was set to 10 m/s, and the wind profile index was specified as 0.26, following the approach of Li et al. [1]. The gradient wind height was defined as 500 m, with the profile calculated using Equation (2). The turbulent wind profile was defined by Equations (3)–(5).

Symmetry boundary conditions were applied to the sides and top of the computational domain, while a pressure outlet condition was specified at the outlet. Wall boundary conditions were assigned to the ground and mountain surfaces, with aerodynamic roughness lengths of 0.03 m and 1.0 m, respectively. The roughness value assigned to the ground surface corresponds to open, relatively smooth terrain, such as grassland, typical of the broader surroundings of the Xumishan Grottoes. The roughness value for mountain surfaces represents rough, irregular terrain, characterized by exposed rock, carved surfaces, and localized vegetation on grotto mountain faces [12]. These roughness lengths were converted into equivalent wall function parameters KS and Cs.

The governing equations were solved using the finite volume method, with an implicit solver suitable for incompressible, low-speed flows. Pressure–velocity coupling was achieved with the SIMPLE algorithm. Pressure was discretized using a second-order scheme, while the convection and viscous terms were discretized with the second-order QUICK scheme. Convergence was considered achieved when the mass residual fell below 10−3, the residuals of other variables fell below 10−5, and the wind speed at monitored locations stabilized.

According to atmospheric boundary layer theory, the strong wind conditions (wind speed greater than 7 m/s) responsible for the wind erosion of stone-carved grotto heritage fall within the neutral stratification regime [1]. Within a neutrally stratified boundary layer, turbulence is dominated by mechanical forcing, and thermal effects are negligible. Consequently, temperature variations were not considered in the present simulations.

2.5. Turbulence Model

This study focuses on the mean wind field characteristics of the Xumishan Grottoes and the spatial distribution of time-averaged wind speed as the primary driver of wind erosion under strong-wind conditions [50,51]. The flow within the atmospheric boundary layer (ABL) over complex terrain is inherently unsteady, which necessitates an unsteady simulation approach. Accurately representing unsteady wind events requires both an unsteady turbulence model and spatiotemporally varying inflow conditions. However, due to the limitations of the current computational hardware, simulating realistic, fully unsteady ABL flows on grids exceeding ten million cells remains impractical. The RANS method undeniably has limitations in capturing the turbulent kinetic energy and does not capture the fluctuating wind pressure on the surface of the object. However, this method offers a viable compromise between accuracy and computational demand. Consequently, RANS methods remain the primary tool in wind engineering for predicting mean wind speeds in critical high-speed flow regions. Although LES is fundamentally superior to the RANS approach [52], because the lack of BPGs, it can even yield results that are less accurate and less reliable that those of RANS; the RANS method remains widely used for simulating mean wind fields in outdoor environments [53]. While modern topography-resolving atmospheric models (e.g., PALM-4U [54], MITRAS [55], and WRF-LES [56]) can explicitly resolve microscale turbulent structures, valley and canyon circulations, and buoyancy-driven flows with high temporal and spatial fidelity, this study selected the steady RANS framework for its computational efficiency and well-established validation in predicting mean wind speed amplification over canyon hilly terrain under neutral conditions—the primary focus of this work. In terms of the selection of turbulence models, the Realizable k-ε turbulence model incorporates modified formulations for turbulent viscosity and dissipation rate, yielding superior performance for flows with separation and recirculation [57]. It is also well suited for high-Reynolds-number flows and demonstrates a high convergence efficiency on tetrahedral grids. Therefore, the steady-state RANS method was employed for numerical simulation, utilizing the Realizable k-ε turbulence model.

2.6. Validation of Numerical Method

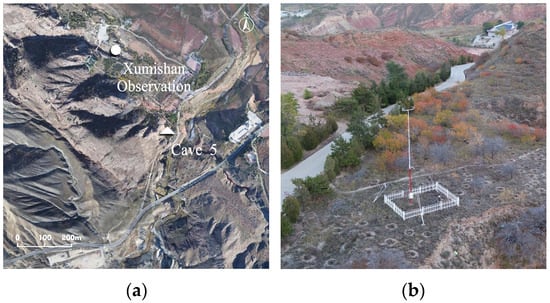

The study case in Li et al. [1] was recreated for this series of studies. The numerical results are compared with field measurement data for meteorological stations in order to validate the numerical method. The meteorological station of the Xumishan Grottoes, situated approximately 300 m from Cave 5, perfectly served as a reference site aimed to identify the wind speed and direction within the grotto zone (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Meteorological station of Xumishan Grottoes. (a) Location of meteorological stations; (b) anemometer in meteorological station.

The boundary conditions, solver settings, grid generation technique, and turbulence model employed in this simulation were identical to those validated in a previous related study [1]. Further details regarding the turbulence model selection and meteorological station configuration are available in this related study. The results demonstrate that the present 3D steady RANS-based numerical method can accurately simulate the spatial wind fields at heritage sites within hilly terrain.

2.7. Monitoring Points Settings

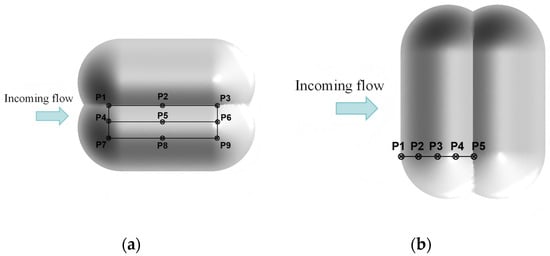

For the canyon mountain under parallel wind condition, nine measurement points (P1–P9) were established at a 10 m height. The points were positioned at the entrance, midpoint, and exit of the following regions: the foot (mid-canyon), the side (mid-slope), and the summit. This configuration was designed to study wind speed distributions parallel to the length of the mountain. Vertical profiles above points P1–P9 were used to analyze wind profile variations at each location, as illustrated in Figure 9a. For the canyon mountain under a vertical wind direction, the flow separation around the mountain results in minimal wind speed at the midpoints of the side, which is not the primary focus of this investigation. Therefore, the analysis was focused on the average wind speed at the entrance cross-section. Given the symmetry of the wind environment about the mountain’s center line, measurement points were deployed on only one side. Furthermore, under a vertical wind direction, the rear mountain is shielded by the front mountain, resulting in a reduced wind speed; this scenario was also not the primary focus of the study. Consequently, only five points (P1–P5) were placed on the front mountain at its windward foot, windward side, summit, leeward side, and leeward foot, as shown in Figure 9b.

Figure 9.

Layout of canyon mountain observation points. (a) Wind direction parallel to the mountain; (b) wind direction vertical to the mountain.

The wind speed ratio at each monitoring point was calculated and compared using the following definition:

where K is the wind speed ratio of the monitoring point, U is the wind speed of the monitoring point, and Uref is the wind speed at the inlet boundary.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Influence of Mountain Length on the Wind Field of Canyon Mountain

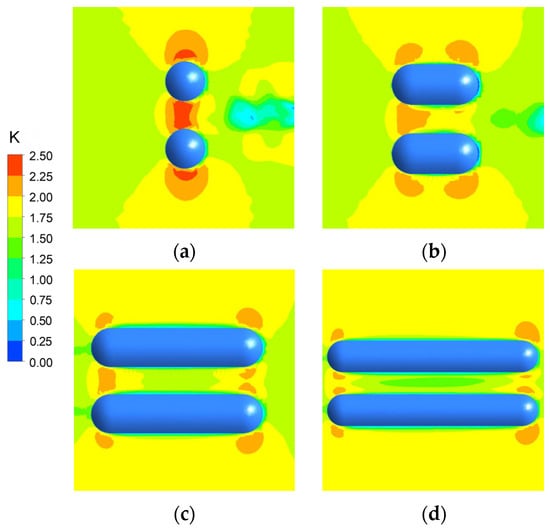

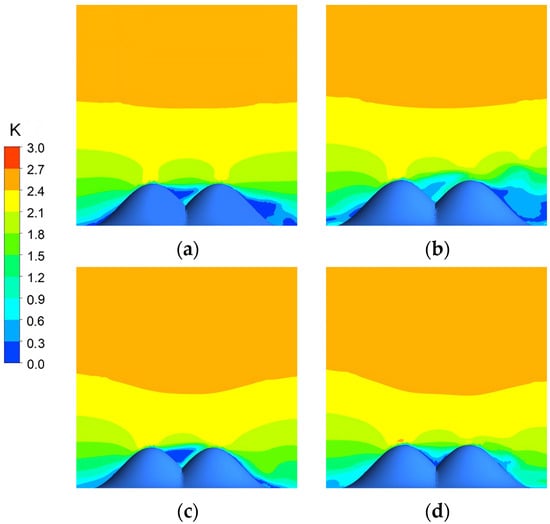

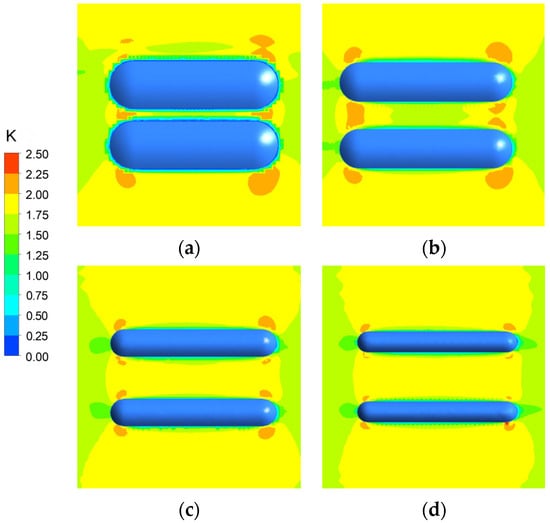

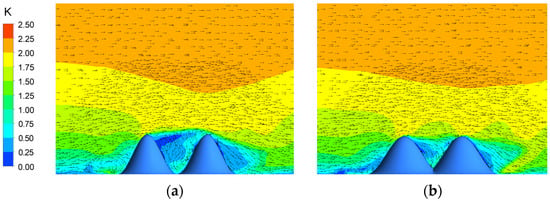

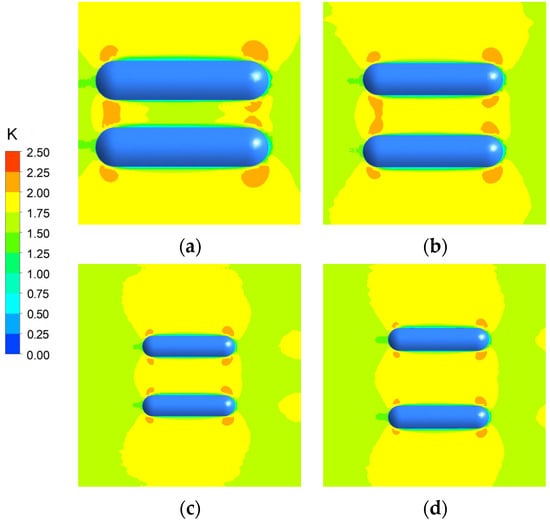

Figure 10 shows the color contours of the simulated wind speed at a height of 0.5H under a parallel wind direction. A distinct acceleration zone forms between the mountains, with the maximum effect occurring at the canyon entrance. Given that Cave 5 is situated at the entrance of a canyon mountain, it is subject to accelerating wind from the channeling effect. Higher wind speeds increase the impact force of sand-carrying wind, aggravating the risk of wind erosion on the windward side. Meanwhile, mountain length significantly influences the wind speed at the entrance; the acceleration effect at the entrance, midpoint, and exit gradually weakens as length increases.

Figure 10.

Color contours of the simulated wind speed at a height of 0.5H under parallel wind direction. (a) L = 0H; (b) L = 1H; (c) L = 3H; (d) L = 5H.

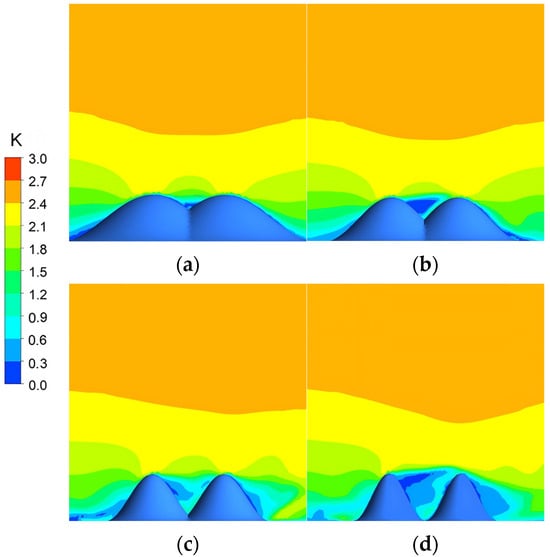

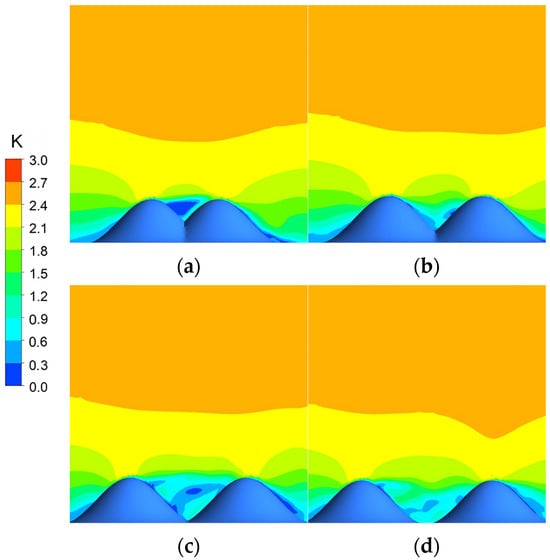

Figure 11 shows color contours of the simulated wind speed in a cross-section at the entrance under a vertical wind direction. The results indicate that the highest wind speed occurs at the summit of the mountain. Due to the windy ridge effect, the wind speeds on the windward side are secondary only to those at the summit, while the lowest speeds are found at the leeward foot. As the mountain length increases, the area of the quiet zone at the leeward foot and mid-canyon section decreases. When the mountain length (L) exceeds three times the height (L > 3H), the quiet zone in the mid-canyon section disappears.

Figure 11.

Color contours of the simulated wind speed in a cross-section at the entrance under vertical wind direction. (a) L = 0H; (b) L = 1H; (c) L = 3H; (d) L = 5H.

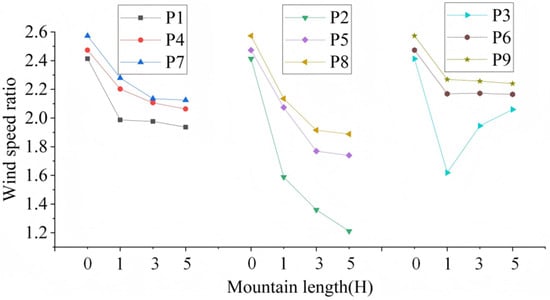

The wind speeds at various observation points under parallel wind directions are shown in Figure 12. An analysis of the figure reveals the following trends: (1) As the canyon length increases from 0H to 1H, the wind speed within the canyon decreases significantly, indicating that the channeling effect is most pronounced within this length range. This trend occurs because, for a mountain with negligible length, the incoming flow rapidly accelerates over the canyon, creating a strong wind acceleration effect. However, for a mountain of significant length, the airflow must traverse an extended surface after passing the canyon, and surface friction along this path decelerates the flow. (2) For canyon lengths up to 3H, wind speeds at the side and summit become stable and independent of further increases in length, while the speeds at the entrance and exit remain higher than at the midpoint. (3) The wind speed change trends for points P4–P6 and P7–P9 are similar, indicating that changes in the mountain length influence the average wind field at the side and summit in a comparable manner. (4) For a canyon length of 1H, as the length increases further, the wind speed at the entrance foot remains relatively constant, while it decreases at the midpoint foot and increases at the exit foot. This pattern arises because airflow decelerates upon entering the canyon due to surface roughness, while, at the exit foot, the wind speed increases due to flow acceleration out of the recirculation zone.

Figure 12.

Wind speeds at various observation points under parallel wind directions.

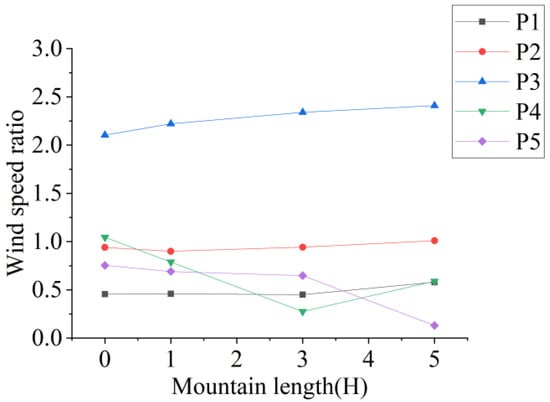

Figure 13 shows the wind speed at the entrance of the canyon mountain under a vertical wind direction. The result reveals that, as the mountain length increases, the wind speed at the windward foot, windward side, and summit increases. For L < 3H, the wind speed on the leeward side and leeward foot at the mid-canyon of the mountain decreases as the length increases. For L > 3H, this trend reverses on the leeward side. The wind speed on the windward side increases because the greater length induces airflow, which has difficulty flowing around the sides, forcing most of the flow over the summit. For 0 < L < 3H, a strong vortex forms in the mid-canyon (Figure 14a). The enhanced overflow from the summit intensifies this vortex, reducing the leeward canyon wind speed. For L = 5H (Figure 14b), the wind speed ratio of the summit reaches 2.41, and the mid-canyon vortex dissipates. This eliminates the vortex sheltering effect, allowing incoming flow to directly increase leeward speed. Meanwhile, flow separation creates a stagnation point at the leeward foot, preventing flow convergence and causing a low wind speed there.

Figure 13.

Wind speeds at the entrance of canyon mountain under vertical wind direction.

Figure 14.

Color contours of the simulated wind speed in a cross-section under vertical wind direction. (a) L = 3H; (b) L = 5H.

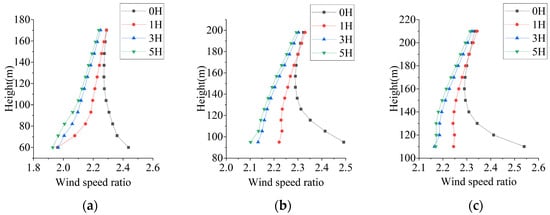

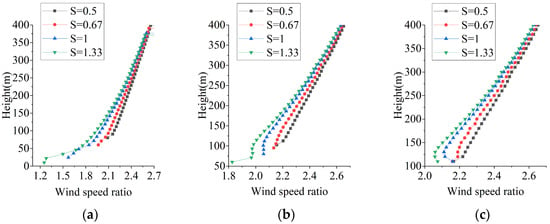

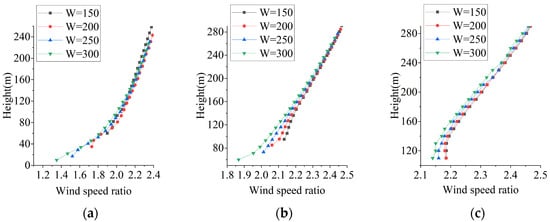

The acceleration effect is most pronounced at the mountain entrance and summit—a trend further intensified by the channeling effect in canyon terrain. Therefore, in the following part of this paper, we mainly conduct a detailed analysis of the wind profile at the entrance and the variation in wind speed at the side and summit under parallel wind directions. Figure 15 shows wind profiles at each measurement point at the entrance of the canyon mountain. The wind profiles are only influenced by mountain length changes within a specific height range. The most pronounced wind speed acceleration at the measurement point occurs when L = 0H. At this length, the wind speed ratio of the foot, side, and summit at a height of 1H reaches 2.3, 2.5, and 2.6, respectively. For L ≥ 3H, the wind profiles at the foot, side, and summit points are almost unaffected by the length of the mountain. The wind profiles at the side and summit are nearly identical and significantly higher than those at the foot. This pattern arises because, in shorter canyons, the accelerated flow diffusion at the outlet exerts a stronger influence on measurement points proximal to the entrance, leading to a marked enhancement of the acceleration effect. In contrast, the increased distance between the entrance and outlet in longer canyons attenuates this influence, resulting in a stabilization of the acceleration ratio.

Figure 15.

Wind profile at various observation points of canyon mountain under parallel wind direction. (a) Mountain foot; (b) mountain side; (c) mountain summit.

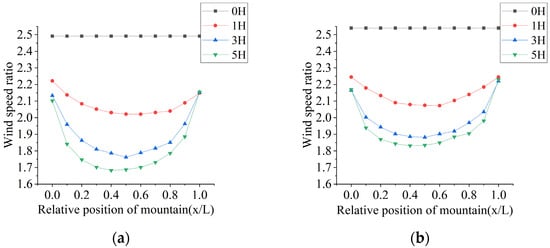

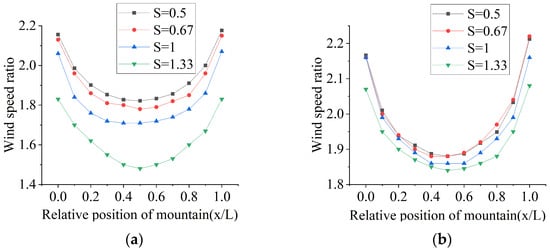

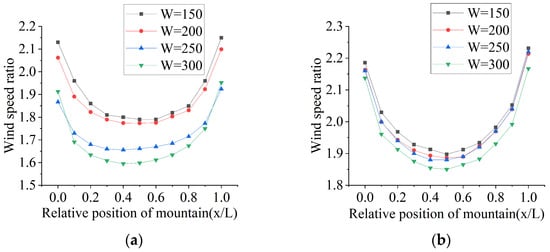

Figure 16 illustrates the wind speed along the length direction of the canyon mountains under a parallel wind direction. The following patterns can be observed: (1) For L ≥ 1H, the wind speed at the midpoint of the side and summit is minimized. Both the range and magnitude of the acceleration area within the canyon decrease as the mountain length increases. For L ≥ 3H, the wind speed for the canyon mountain configuration continues to decrease with increasing length, suggesting that the internal canyon wind speed is more susceptible to mountain length. (2) The trend of wind speed change is similar at the summit and the side. Although the wind speed is greater at the summit, the amplitude of its change across various mountain lengths is smaller than that at the side position. (3) As the mountain length increases, the location of the minimum wind speed at both the side and the summit gradually shifts toward the entrance. At L = 5H, the minimum wind speed occurs at the position of x = 0.4L.

Figure 16.

Wind speeds along the length direction of canyon mountains under parallel wind direction. (a) Mountain side; (b) mountain summit.

3.2. The Influence of Mountain Slope on the Wind Field of Canyon Mountain

Figure 17 shows the color contours of the simulated wind speed at a height of 0.8H under a parallel wind direction. A significant wind acceleration effect is observed at both the canyon entrance and canyon exit position for all slopes. The spatial extent of the acceleration zone on the side gradually contracts as the slope increases. Despite this, the acceleration phenomena around mountains of different slopes share common characteristics; a distinct deceleration zone forms within the canyon. The spatial extent of this low-wind-speed area gradually contracts as the slope increases.

Figure 17.

Color contours of the simulated wind speed at a height of 0.8H under parallel wind direction. (a) S = 0.5; (b) S = 0.67; (c) S = 1; (d) S = 1.33.

Figure 18 shows the color contours of the simulated wind speed in a cross-section at the entrance under a vertical wind direction. The contours reveal an acceleration effect present on the windward side, extending from approximately two-thirds of the mountain height to the summit. For a slope of 0.5, the wind environment exhibits an approximate symmetry between the windward and leeward side. Additionally, as can be seen from the figure, the wind speeds on the windward side of the mid-canyon exceed those on the leeward side. As the slope of the canyon affects the cross-sectional area of the canyon, for slopes greater than 0.67, a quiet zone forms in the mid-canyon, and its spatial extent expands with increasing slope.

Figure 18.

Color contours of the simulated wind speed in a cross-section at the entrance under vertical wind direction. (a) S = 0.5; (b) S = 0.67; (c) S = 1; (d) S = 1.33.

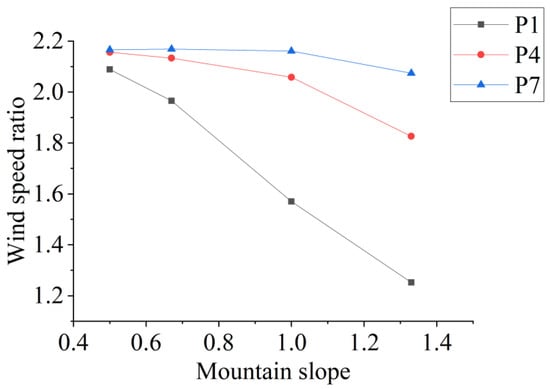

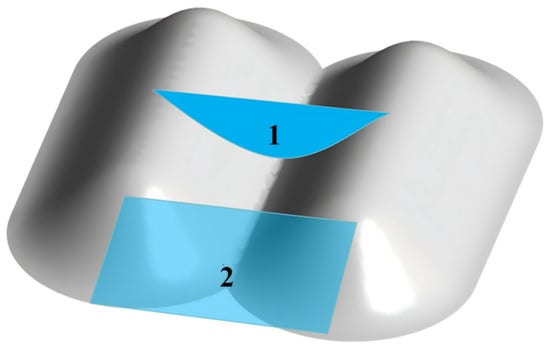

The wind speeds at various observation points under a parallel wind direction are shown in Figure 19. The result shows that the wind speed at the canyon entrance gradually decreases with increasing slope. The wind speed at the foot of the canyon is significantly more sensitive to slope changes than the speed at the summit. When the slope increases from 0.5 to 1.33, the wind speed at the windward foot decreases by 40.06%, compared to only 4.26% at the summit. This difference arises because the airflow acceleration within the canyon is governed by a compression effect, which is directly related to the cross-sectional area of canyon. As shown in Figure 20, a steeper slope increases the ratio of the internal cross-section (Area 1) to the upstream, uncompressed cross-section (Area 2). This reduced compression ratio diminishes the airflow acceleration effect. In contrast, the summit has a greater exposure to the external airflow, mitigating the influence of canyon slope changes on its wind acceleration.

Figure 19.

Wind speeds at various observation points under parallel wind direction.

Figure 20.

Schematic diagram of canyon cross-section area.

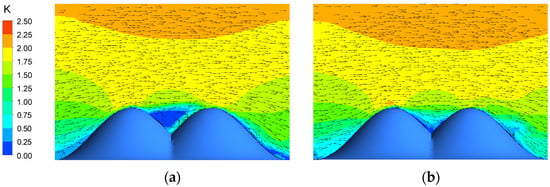

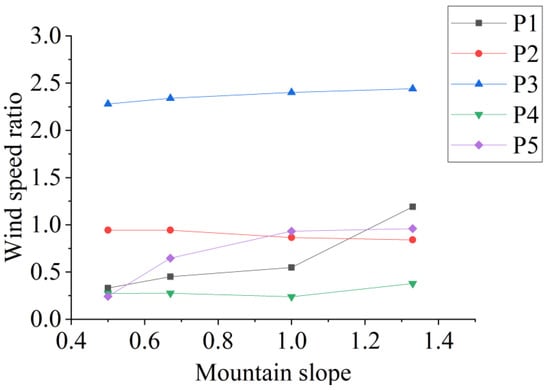

The wind speeds at the entrance of the canyon mountain under a vertical wind direction are shown in Figure 21. As the slope increases, the wind acceleration at both the summit and the windward foot becomes more pronounced; however, the magnitude of this increase differs significantly between the two locations. When the slope increases from 0.5 to 1.33, the wind speed increases by 7.06% at the summit, and approximately 200% at the windward foot. For slopes less than 1.0, the gentle incline prevents vortex formation at the windward foot. At a slope of 1.33, a distinct vortex forms, and the windward face behaves similarly to the windward wall of an urban street canyon (Figure 22).

Figure 21.

Wind speeds at the entrance of canyon mountain under vertical wind direction.

Figure 22.

Color contours of the simulated wind speed in a cross-section under vertical wind direction. (a) S = 1; (b) S = 1.33.

Because the mountain containing Cave 5 is adjacent to another mountain, forming a canyon with a slope of approximately 1.33, the local wind environment is influenced by this terrain. Consequently, a distinct vortex forms on the mid-canyon section, where the wind speed on the windward side is relatively high. Wind erosion by sand-carrying wind primarily involves two mechanisms: First, high-speed airflow transports sand, which impacts the mountain and causes frontal erosion. Simultaneously, sand grains within the vortex rotate at a high speed and also perform erosion on the mountain. When the eroded windward side of the mountain forms certain grooves, the sand-carrying wind forms a vortex within them, further accelerating erosion. In contrast, on the leeward side of the canyon, the reduced wind speed and the absence of a vortex mitigate wind erosion (Figure 23). Although the models are geometrically simplified, the observed parametric trends yield interpretable insights into site-specific wind behavior. Thus, even idealized models can capture the dominant flow mechanisms driving erosion in heritage settings, demonstrating the value of this parametric approach.

Figure 23.

Current wind erosion state of canyon mountain in Xumishan Grottoes.

Figure 24 shows the wind profile at various observation points of the canyon mountain under a parallel wind direction. The influence of the slope on the wind profiles is consistent across different locations within the canyon. Within a specific height range, the wind speed decreases as the slope increases. Above a height of 4H, the wind profiles become independent of the slope magnitude.

Figure 24.

Wind profile at various observation points of canyon mountain under parallel wind direction. (a) Mountain foot; (b) mountain side; (c) mountain summit.

The wind speeds along the length direction of the canyon mountains under a parallel wind direction are shown in Figure 25. The figure reveals two primary trends: (1) The wind speeds at the side and summit decrease with an increasing slope. (2) The lowest wind speeds occur at the midpoint of the side and summit. Furthermore, the wind speed at the summit is less sensitive to slope changes than the wind speed at the side. This behavior occurs because, for slopes greater than 0.67, the increased surface friction on the steeper slopes has a greater dampening effect on the near-ground airflow (measured at 10 m height), leading to lower wind speeds. In addition, unlike an isolated mountain influenced primarily by orographic effects, a canyon terrain is subject to both orographic acceleration and channeling effects. When the slope decreases, the channeling effect contribution to acceleration diminishes more significantly at the summit than at the side position.

Figure 25.

Wind speeds along the length direction of canyon mountains under parallel wind direction. (a) Mountain side; (b) mountain summit.

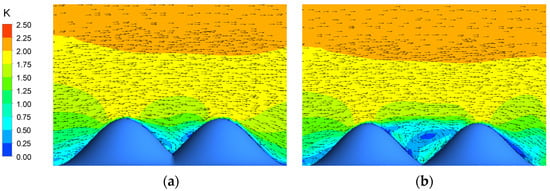

3.3. The Influence of Mountain Spacing on the Wind Field of Canyon Mountain

Figure 26 shows the color contours of the simulated wind speed at a height of 0.8H under a parallel wind direction. Due to the channeling effect, mountain spacing significantly influences the wind speed within the canyon. For a mountain spacing between 2/3D and D, the wind speed at the entrance decreases significantly as the spacing increases. However, at a spacing of 1/2D, a distinct deceleration zone forms between the mountains. This occurs because, at a very narrow spacing, the surface friction effect dominates over the channeling effect, leading to reduced wind speeds.

Figure 26.

Color contours of the simulated wind speed at a height of 0.8H under parallel wind direction. (a) W = 1/2D; (b) W = 2/3D; (c) W = 2/3D; (d) W = D.

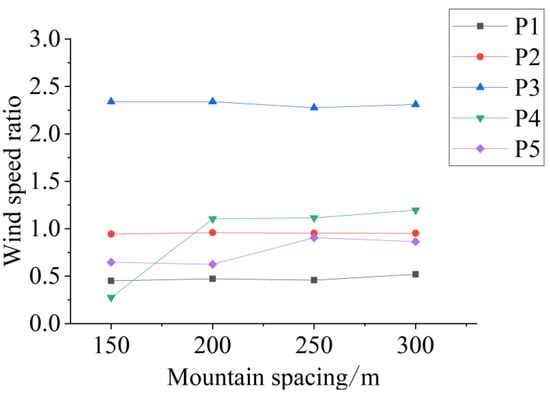

Figure 27 shows the color contours of the simulated wind speeds in a cross-section at the entrance under a vertical wind direction. The wind speeds at various positions on the windward side of the front mountain are largely unaffected by changes in mountain spacing. The mid-canyon region exhibits flow field characteristics analogous to a typical urban street canyon: the wind speed inside the canyon increases, and the quiet zone area decreases as the mountain spacing increases. When the mountain spacing equals the mountain diameter (W = D), the quiet zone within the canyon basically disappears.

Figure 27.

Color contours of the simulated wind speed in a cross-section at the entrance under vertical wind direction. (a) W = 1/2D; (b) W = 2/3D; (c) W = 2/3D; (d) W = D.

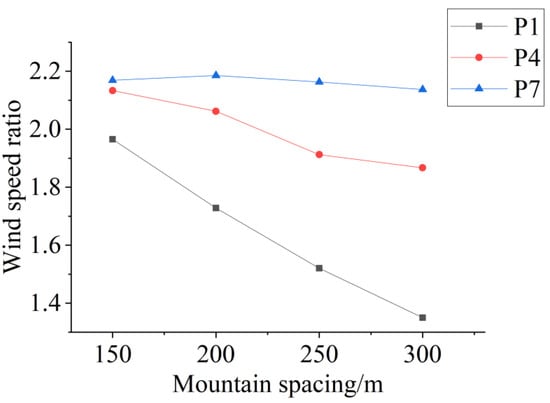

The wind speeds at various observation points under a parallel wind direction are shown in Figure 28. From the figure, the following three results can be obtained: (1) The wind speed at the mountain summit is minimally affected by spacing. For assessing the average summit wind speed, the canyon can be approximated as an isolated mountain. (2) The wind speed at the mountain side decreases gradually with increasing spacing. For a spacing greater than 5/6D, the sensitivity of the wind speed to spacing changes diminishes. This occurs because, as the spacing increases, the influence of the opposite mountain and the channeling effect weaken, resulting in a smaller amplitude of wind speed variations. (3) The wind speed at the mountain foot decreases significantly and approximately linearly as the spacing increases. This linear relationship arises because the increased spacing reduces the mountain foot relative to the base ground level, weakening the windy ridge effect. Consequently, the wind speed at the canyon foot can be estimated using a linear interpolation method.

Figure 28.

Wind speed at various observation points under parallel wind direction.

Figure 29 shows the wind speed at the entrance of the canyon mountain under a vertical wind direction. The wind speeds at the leeward side and foot reach their maximum values at a mountain spacing of 2/3D, respectively. Under a vertical wind direction, the presence of the rear mountain prevents the airflow from diverting around the sides, as it would with an isolated mountain. Consequently, most flow is forced over the summit, which stabilizes the wind speed on the windward side across different slopes. At a spacing of 2/3D, the narrow canyon inhibits vortex formation. Without the reverse airflow of a vortex, the leeward side experiences less flow disruption, allowing the wind speed to reach a maximum. At a wider spacing of 5/6D, a distinct vortex forms in the canyon (Figure 30). This vortex eliminates the stagnation point at the leeward foot position, leading to a significant increase in the wind speed there.

Figure 29.

Wind speeds at the entrance of canyon mountain under vertical wind direction.

Figure 30.

Color contours of the simulated wind speed in a cross-section under vertical wind direction. (a) W = 5/6 D; (b) W = D.

The wind profiles at various observation points of the canyon mountain under a parallel wind direction are shown in Figure 31. For all positions at the entrance, the wind speed acceleration effect diminishes with an increasing mountain spacing. At a height of 1H above the summit, the influence of different spacings on the wind speed becomes consistent, indicating that the effect of mountain spacing is confined to within 1H of the surface.

Figure 31.

Wind profile at various observation points of canyon mountain under parallel wind direction. (a) Mountain foot; (b) mountain side; (c) mountain summit.

Figure 32 shows the wind speeds along the length direction of the canyon mountains under a parallel wind direction. The lowest wind speeds occur at the midpoint between the side and summit of the canyon. This minimum occurs because the acceleration effect generated at the canyon entrance diminishes as airflow penetrates into the canyon interior. When the mountain spacing decreases, the reduced internal cross-sectional area enhances the channeling effect, thereby increasing the wind speed along the mountain surface.

Figure 32.

Wind speeds along the length direction of canyon mountains under parallel wind direction. (a) Mountain side; (b) mountain summit.

3.4. Modification of the Formula for Calculating the Acceleration Ratio of Hilly Terrain

Due to the eastward wind prevailing in the area of the Xumishan Grottoes, the wind speed ratio in front of the Cave 5 reaches its maximum value of 2.1 under this wind direction [1]. The wind erosion climate factor index C, one of the five variables of the equation, is used to represent the influence of climate conditions on the wind erosion degree. The wind erosion climate factor index is given by the following [58]:

where C is the wind erosion climatic factor index, is the monthly average wind speed (m/s) at 2 m, is the monthly precipitation (mm), ET is the monthly potential evaporation (mm), and d is the number of days in a month.

Therefore, it can be considered that the eastward incoming wind along the mountain is the primary-harm wind direction for the protection of stone carvings. In addition, according to the numerical simulation results of the wind environment in the previous content, the wind speed changes at the summit and side of the mountain have similar trends, and the wind speed at the side of the mountain is slightly lower than that at the summit of the mountain. Cave 5 of the Xumishan Grottoes, which is the focus of this study, is located at the side of the mountain. Therefore, this paper focuses on analyzing the influence of the length, slope, and spacing of the mountain on the acceleration effect of the canyon mountain side under the direction along the mountain. Finally, based on the analysis data, a modified formula for calculating the acceleration ratio is obtained.

In order to analyze the influence of different terrain parameters on the acceleration effect of the canyon mountains, the wind speed of the mountains under different conditions was calculated. The height of the mountains in each calculation condition was equal (H = 100 m). The acceleration ratio ∆S and parameter B at the mountain side position of the canyon mountain were calculated and are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The fitted values of ∆S and B for various canyon mountain parameters.

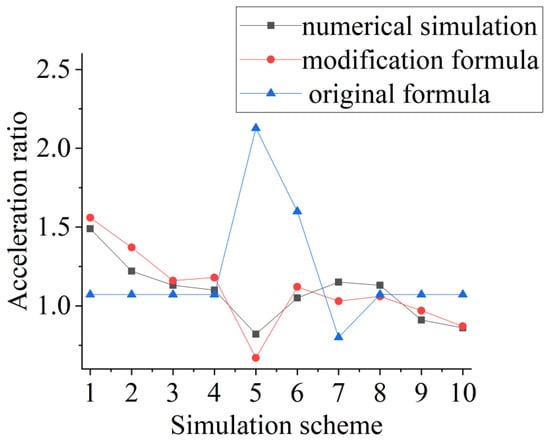

Table 2 indicates that the acceleration ratio on the mountain side of the canyon decreases with an increasing mountain length but increases with a greater slope and spacing. In addition, unlike the calculation method of Jackson and Hunt (referred to as the “original formula”), the calculated B value is not always equal to 1.6, but varies with the mountain length, slope, and spacing. The modified acceleration Equations (8)–(11) were derived through a regression analysis of ten simulation cases covering a representative range of canyon terrain parameters. Although derived from idealized terrain simulations, the parameter ranges were selected to encompass the typical topographic variations observed at canyon heritage sites like the Xumishan Grottoes.

where , , and represent the length of the mountain, the slope of the mountain, and the correction coefficient for the spacing of the mountain, respectively. The value of B is a constant, 5.67.

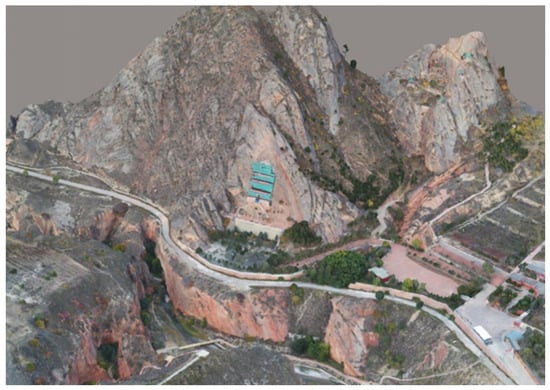

In order to verify the accuracy of the acceleration ratio calculation formula proposed in this paper, the acceleration ratio calculated using the above formula was compared with the numerical simulation and the original formula, as shown in Figure 33. From the figure, it can be seen that the original formula increases with the increase in the slope of the mountain and does not change with the length and spacing of the mountain. However, the acceleration ratio correction coefficient from this paper takes into account the factors of mountain length, slope, and spacing. The results calculated using the formula are in good agreement with the data simulation, and the accuracy is higher than that of the original algorithm formula.

Figure 33.

Comparison of modification of the formula, numerical simulation, and original formula calculation results.

Figure 34 shows the actual terrain of the mountain where Cave 5 of the Xumishan Grottoes is located. The wind speed in front of Cave 5 is relatively high, and the stone-carved grotto heritage is prone to erosion by strong winds. Analyzing the topographic features of the mountain, it is found that the mountain where Cave 5 is located is a typical canyon mountain terrain, and Cave 5 is located at the entrance of the mountain side. The extracted topographic parameters of the hilly terrain are as follows: the length of the mountain is 160 m, the height is 80 m, the diameter at the bottom of the mountain is 160 m, the corresponding slope is 1, and the spacing of the mountain is 100 m. By substituting these parameters into Equations (8)–(11), the acceleration ratio in front of Cave 5 is calculated to be 1.29, and the corresponding wind speed ratio value is 2.29. Through the numerical simulation mentioned earlier, when the wind direction is eastward, the wind speed ratio value in front of Cave 5 is 2.1. A discrepancy of only 9.05% between the formula and simulation results suggests that the formula can provide reasonable estimates for canyon-type heritage terrains with similar topographic characteristics. However, its applicability to highly irregular, non-cosine terrain or to canyons with pronounced three-dimensional flow features remains invalidated. In practice, the formula is best used as a terrain-sensitive screening tool to identify zones of potential wind acceleration, with findings subsequently verified by site-specific measurements or high-fidelity simulations.

Figure 34.

Cave 5 of the Xumishan Grottoes.

The mountain ridge area on the west side of the Xumishan Grottoes has a canyon terrain with a length close to 0H. Therefore, the airflow accelerates as it passes through the eastern–western-oriented canyon entrance. The Xumishan Grottoes are located at the entrance of this canyon terrain, so the background wind speed in the entire grotto area is relatively high. In addition, the Buddha statue in Cave 5 of the Xumishan Grottoes is located on the canyon mountain side at the upper part of the mountain. The acceleration effect of the wind provides sufficient wind conditions for the weathering and damage of the stone-carved grotto heritage, which also explains the severe weathering phenomenon of the Buddha statue and the mountain where it is located. Therefore, the acceleration effect at the upper part of the mountain side at the entrance of the mountain needs to be given special attention.

3.5. Study Limitations and Future Directions

Despite providing a detailed analysis of canyon–hilly wind fields and an improved acceleration ratio formula for grotto heritage sites, this study has limitations that suggest directions for future research.

Firstly, the simulations were conducted under a neutral atmospheric stratification, corresponding to the strong-wind conditions (wind speed > 7 m/s) most relevant to wind erosion. This simplification neglects radiative forcing and terrain-induced thermal circulations, which are known to significantly influence flow patterns in complex topography—particularly through buoyancy effects, slope winds, and diurnal heating/cooling cycles [59]. For instance, studies using radiation-aware models in complex terrain demonstrate that daytime heating can enhance upslope flows and weaken canyon recirculation [60], whereas nighttime cooling may strengthen downslope winds and stabilize the boundary layer. Collectively, these thermal processes can alter wind speed, turbulence structure, and recirculation within canyons, thereby affecting erosion dynamics at solar-exposed heritage sites. While the neutral assumption is standard in wind engineering studies of mean wind loads, future work aimed at holistic microclimate assessment should incorporate radiative and thermal boundary conditions.

Secondly, the validation in this study relies on wind speed data from a single meteorological station located approximately 300 m from the canyon entrance, along with comparisons to a previously published simulation by the authors. While this provides a reasonable point of reference for mean wind speeds under neutral conditions, it does not fully capture the spatial heterogeneity of wind acceleration, leeward recirculation zones, or localized speed-up at the canyon summit and side slopes. For more a robust validation of canyon-type terrain simulations, future studies should incorporate multi-point field measurements via anemometer arrays distributed across key topographic positions to resolve spatial flow patterns. Additionally, the wind tunnel testing of scaled canyon models under controlled inflow conditions could validate separation, recirculation, and acceleration effects.

Finally, the deterioration of stone heritage results from the synergistic effects of multiple environmental factors, including humidity, rainfall, freeze–thaw cycles, thermal stress, and chemical processes. Future studies should integrate thermal and moisture transport models to simulate non-neutral boundary layers and to assess coupled hydro-thermo-mechanical degradation processes. Ultimately, wind field data should be incorporated into a multi-hazard risk assessment framework that accounts for the interactions between wind, water, temperature, and chemical agents. Such an integrated approach would better support the design of preventive protection measures for vulnerable heritage sites such as the Xumishan Grottoes.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated wind field characteristics to inform the preventive protection of heritage sites. Using computational fluid dynamics (CFD), the effects of key terrain parameters—mountain length, slope, and spacing—on wind field characteristics were systematically analyzed. The principal conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- For a canyon mountain under parallel wind conditions, the channeling effect is most critical when the mountain length is zero (L = 0H). When the length increases to 3H, the wind speed at the side and summit stabilize and become independent of further length increases. The wind speed at the canyon entrance decreases gradually with an increasing slope. The wind speed at the side decreases with increasing mountain spacing. For a spacing greater than (5/6)D, the sensitivity of the wind speed to spacing changes diminishes.

- (2)

- For a canyon mountain under vertical conditions, the highest wind speeds occur at the summit, followed by the side and foot of the front mountain. The wind speeds at the windward side of the canyon exceed those at the leeward side. For slopes greater than 0.67, a distinct quiet zone forms in the mid-canyon, and its spatial extent expands with an increasing slope. The wind speed on the leeward side of the front mountain is largely unaffected by spacing. The mid-canyon quiet zone exhibits behavior analogous to a typical urban street canyon: the wind speed within the canyon increases and the quiet zone area decreases as the spacing increases. When the mountain spacing equals the mountain diameter (W = D), the quiet zone within the canyon disappears.

- (3)

- The calculation formula for the acceleration ratio, obtained by fitting the terrain parameters such as the mountain length, slope, and spacing, has a higher accuracy than the original formula. This was validated specifically using Cave 5 of the Xumishan Grottoes as a case study. The discrepancy between the formula prediction and the simulation results was only 9.05%. The refined formula thus provides a more accurate and reliable predictive tool for assessing the wind environment in grotto zones.

The study was based on CFD simulations to investigate the formation of wind fields over hilly terrain, and its impact on cave site protection is feasible. This research also provides a reference for studying the characteristics of a mountain urban wind environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. and G.X.; methodology, P.N.; software, H.L. and D.Z.; validation, Y.L., S.Y., and P.C.; formal analysis, Z.W.; investigation, C.L.; resources, Z.Y. and S.Z.; data curation, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L.; writing—review and editing, H.L.; visualization, P.N.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, H.L.; funding acquisition, Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number (51378412 and 51978554), and Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects, grant number (202501CF070061).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, H.; Yan, Z.; Dai, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Yao, S.; Wang, X. Numerical Simulation of Spatial Wind Fields in Xumishan Grottoes over Complex Terrain. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, X.-Y.; Deng, E.; Ni, Y.-Q.; Chan, P.-W.; Yang, W.-C.; Tan, Y.-K. Acceleration and Reynolds Effects of Crosswind Flow Fields in Gorge Terrains. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 085143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.S.; El-Shishiny, H. Influences of Wind Flow over Heritage Sites: A Case Study of the Wind Environment over the Giza Plateau in Egypt. Environ. Model. Softw. 2009, 24, 389–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, H.; Viles, H. A Controlled Field Experiment to Investigate the Deterioration of Earthen Heritage by Wind and Rain. Herit. Sci. 2019, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, E.; Yue, H.; Liu, X.-Y.; Ni, Y.-Q. Aerodynamic Impact of Wind-Sand Flow on Moving Trains in Tunnel-Embankment Transition Section: From Field Testing to CFD Modeling. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2023, 17, 2279993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhu, S.; Ye, T.; Miao, Y. Optimizing Urban Ventilation in Heritage Settings: A Computational Fluid Dynamics and Field Study in Zhao’an Old Town, Fujian. Buildings 2025, 15, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau-Bové, J.; Mazzei, L.; Strlic, M.; Cassar, M. Fluid Simulations in Heritage Science. Herit. Sci. 2019, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Lang, J.; Wang, X. A Numerical Study of the Effect of Vegetative Windbreak on Wind Erosion over Complex Terrain. Forests 2022, 13, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Tan, L.; Zhang, G.; Qiu, F.; Zhan, H. Aeolian Processes over Gravel Beds: Field Wind Tunnel Simulation and Its Application atop the Mogao Grottoes, China. Aeolian Res. 2014, 15, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, B.; An, Z.; Li, J. Simulation of Wind Velocity Reduction Effect of Gravel Beds in a Mobile Wind Tunnel atop the Mogao Grottoes of Dunhuang, China. Eng. Geol. 2013, 159, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, P.; Iranzo, A. Analysis of Sand-Loaded Air Flow Erosion in Heritage Sites by Computational Fluid Dynamics: Method and Damage Prediction. J. Cult. Herit. 2017, 25, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocken, B.; van der Hout, A.; Dekker, J.; Weiler, O. CFD Simulation of Wind Flow over Natural Complex Terrain: Case Study with Validation by Field Measurements for Ria de Ferrol, Galicia, Spain. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2015, 147, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, S.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, Q.; Li, L.; Chan, P.W. Effects of Inflow Conditions on Mountainous/Urban Wind Environment Simulation. Build. Simul. 2017, 10, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, M.; Yan, Z.; Ma, C.; Li, Z.; Yi, H.; Li, F.; Ni, P. Measurement and Inversion of Urban Multi-Area Ambient Temperature under the Protection Demand of Longmen Grottoes, China. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Luo, Y.; Song, C.; Jin, W.; Xiang, T.; Qiao, M.; Dang, J.; Bai, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, J. Effect of Calcium Stearate Hydrophobic Agent on the Performance of Mortar and Reinforcement Corrosion in Mortar with Cracks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 450, 138684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, A.; Keshmiri, A. Computational Simulation of Wind Microclimate in Complex Urban Models and Mitigation Using Trees. Build. 2021, 11, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccolieri, R.; Santiago, J.-L.; Rivas, E.; Sanchez, B. Review on Urban Tree Modelling in CFD Simulations: Aerodynamic, Deposition and Thermal Effects. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 31, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, C.J.; Watson, S.J.; Hancock, P.E. Modelling the Wind Energy Resource in Complex Terrain and Atmospheres. Numerical Simulation and Wind Tunnel Investigation of Non-Neutral Forest Canopy Flow. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2017, 166, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheynet, E.; Liu, S.; Ong, M.C.; Bogunović Jakobsen, J.; Snæbjörnsson, J.; Gatin, I. The Influence of Terrain on the Mean Wind Flow Characteristics in a Fjord. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2020, 205, 104331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, K.T.; Weerasuriya, A.U.; Hu, G. Integrating Topography-Modified Wind Flows into Structural and Environmental Wind Engineering Applications. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2020, 204, 104270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.-L.; Li, J.-W.; Flay, R.G.J. Field Measurements and Wind Tunnel Investigation of Wind Characteristics at a Bridge Site in a Y-Shaped Valley. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2020, 202, 104199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, P.; Wang, S.; Lu, X.; Jin, Y. Detection and Evaluation of a Ventilation Path in a Mountainous City for a Sea Breeze: The Case of Dalian. Build. Environ. 2018, 145, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Peng, H.; Chan, P.; Zeng, X. Wind Tunnel Testing of the Effect of Terrain on the Wind Characteristics of Airport Glide Paths. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2020, 203, 104253. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, X. Wind Field Simulation over Complex Terrain under Different Inflow Wind Directions. Wind Struct. 2019, 28, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Wang, T.; Ge, Y.; Tamura, Y. Numerical Study on Turbulent Boundary Layers over Two-Dimensional Hills—Effects of Surface Roughness and Slope. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2012, 104–106, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Tang, J.; Li, M.; Yang, G.; Shen, Z. Experimental Study of the Impact of Upstream Mountain Terrain and Urban Exposure on Approaching Wind Characteristics. Build. Environ. 2024, 248, 111071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wang, W.; Gu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Shu, Z. Investigation of Hilly Terrain Wind Characteristics Considering the Interference Effect. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2023, 241, 105543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, T.; Sugitani, K. Numerical and Experimental Study of Topographic Speed-Up Effects in Complex Terrain. Energies 2020, 13, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, S.; Xiao, Z.; Zhou, D. Detailed interpolation distribution of hilly wind topographic factor along hillside. J. Hunan Univ. Nat. Sci. 2016, 43, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P.S.; Hunt, J.C.R. Turbulent Wind Flow over a Low Hill. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1975, 101, 929–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB50009-2012; Load Code for the Design of Building Structures. The Standards of People’s Republic of China. China Architecture Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Cheynet, E.; Jakobsen, J.B.; Snæbjörnsson, J.; Angelou, N.; Mikkelsen, T.; Sjöholm, M.; Svardal, B. Full-Scale Observation of the Flow Downstream of a Suspension Bridge Deck. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2017, 171, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, J.; Chen, G. Experimental Study of Urban Microclimate on Scaled Street Canyons with Various Aspect Ratios. Urban Clim. 2022, 46, 101299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chew, L.W.; Fan, Y.; Gromke, C.; Hang, J.; Yu, Y.; Ricci, A.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Fellini, S.; et al. Fluid Tunnel Research for Challenges of Urban Climate. Urban Clim. 2023, 51, 101659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flay, R.G.J.; King, A.B.; Revell, M.; Carpenter, P.; Turner, R.; Cenek, P.; Pirooz, A.A.S. Wind Speed Measurements and Predictions over Belmont Hill, Wellington, New Zealand. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2019, 195, 104018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Deng, E.; Ni, Y.-Q.; He, X.-H.; Chan, P.-W.; Yang, W.-C.; Li, H.; Xie, Z.-Y. Mitigating Inflow Acceleration Effects in Twin Mountains Using Air Jets: Emphasis on Anti-Wind for High-Speed Railways. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 055128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potsis, T.; Stathopoulos, T. A Novel Computational Approach for an Improved Expression of the Spectral Content in the Lower Atmospheric Boundary Layer. Buildings 2022, 12, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, M.; Horna, D. A Numerical Investigation of the Relationship Between Air Quality, Topography, and Building Height in Populated Hills. Buildings 2025, 15, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, L.; Stathopoulos, T.; Marey, A.M. Urban Microclimate and Its Impact on Built Environment-A Review. Build. Environ. 2023, 283, 110334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubayer, C.M.; Hangan, H. A Hybrid Approach for Evaluating Wind Flow over a Complex Terrain. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2018, 175, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocken, B. 50 Years of Computational Wind Engineering: Past, Present and Future. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2014, 129, 69–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Hang, J.; Li, Y. Urban Heat Island Circulations of an Idealized Circular City as Affected by Background Wind Speed. Build. Environ. 2019, 148, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocken, B.; Stathopoulos, T.; van Beeck, J. Pedestrian-Level Wind Conditions around Buildings: Review of Wind-Tunnel and CFD Techniques and Their Accuracy for Wind Comfort Assessment. Build. Environ. 2016, 100, 50–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Jiang, N.; Liu, W.; Chen, Q. Evaluation of Fast Fluid Dynamics with Different Turbulence Models for Predicting Outdoor Airflow and Pollutant Dispersion. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 77, 103583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Shen, G.; Yao, D.; Xing, Y.; Lou, W. CFD-based numerical simulation of wind field characteristics on valley and col terrain. J. Harbin Inst. Technol. 2016, 48, 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, J.; Hellsten, A.; Schlunzen, K.H.; Carissimo, B. The COST 732 Best Practice Guideline for CFD Simulation of Flows in the Urban Environment: A Summary. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 44, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, Y.; Mochida, A.; Murakami, S.; Sawaki, S. Comparison of Various Revised k–ε Models and LES Applied to Flow around a High-Rise Building Model with 1:1:2 Shape Placed within the Surface Boundary Layer. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2008, 96, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roache, P.J. Quaptification Ofuncertainty Incomputational Fluid Dynamics. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1997, 29, 123–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, P. Appropriate Boundary Conditions for Computational Wind Engineering Models Using the K-ε Turbulence Model. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 1993, 46–47, 145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Jianjun, Q.; Weimin, Z.; Yuanping, W.; Fengnian, D.; Zuixiong, L.; Yuhua, S. Deflation mechanism of Mogao Grotto rock bodies and their protective strategies. J. Desert Res. 1994, 14, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, E.; Liu, X.-Y.; Yue, H.; Yang, W.-C.; Ouyang, D.-H.; Ni, Y.-Q. How Do Dunes along a Desert Urban Motorway Affect the Driving Safety of Sedans? Evidences from Long- and Short-Term Monitoring and IDDES. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2023, 243, 105595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, Y.; Deng, E.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Lei, M. Characteristics of Wind Field at Tunnel-Bridge Area in Steep Valley: Field Measurement and LES Study. Measurement 2022, 202, 111806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocken, B. LES over RANS in Building Simulation for Outdoor and Indoor Applications: A Foregone Conclusion? Build. Simul. 2018, 11, 821–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, J.; Schubert, S.; Sauter, T.; Tunn, S.; Schneider, C.; Salim, M. Modelling the Impact of an Urban Development Project on Microclimate and Outdoor Thermal Comfort in a Mid-Latitude City. Energy Build. 2023, 296, 113324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, M.H.; Schluenzen, K.H.; Grawe, D.; Boettcher, M.; Gierisch, A.M.U.; Fock, B.H. The Microscale Obstacle-Resolving Meteorological Model MITRAS v2.0: Model Theory. Geosci. Model Dev. 2018, 11, 3427–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Shen, L.; Xu, G.; Cai, C.S.; Hu, P.; Zhang, J. Multiscale Simulation of Wind Field on a Long-Span Bridge Site in Mountainous Area. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2018, 177, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, T.-H.; Liou, W.W.; Shabbir, A.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, J. A New K-ϵ Eddy Viscosity Model for High Reynolds Number Turbulent Flows. Comput. Fluids 1995, 24, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. A Provisional Methodology for Soil Degradation Assessment; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L.; Schubert, S.; Fenner, D.; Salim, M.H.; Schneider, C. Estimation of Mean Radiant Temperature in Cities Using an Urban Parameterization and Building Energy Model within a Mesoscale Atmospheric Model. Meteorol. Z. 2022, 31, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, M.H.; Schubert, S.; Resler, J.; Krč, P.; Maronga, B.; Kanani-Sühring, F.; Sühring, M.; Schneider, C. Importance of Radiative Transfer Processes in Urban Climate Models: A Study Based on the PALM 6.0 Model System. Geosci. Model Dev. 2022, 15, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).