Abstract

The proliferation of free-form architecture necessitates efficient detailing methods for complex spatially bending-torsion steel members. Current approaches suffer from low modeling efficiency, inaccurate surface fitting, and limited capabilities for variable-section generation and plate unfolding. This study presents a comprehensive parametric detailing module developed within the Grasshopper (GH) platform to overcome these challenges. The core innovations include (1) a data structure that integrally describes member axes, cross-sections, and unfolding information; (2) an algorithm that automatically generates interpolation points based on curvature variation to ensure axis smoothness; (3) the use of architectural surface normals as member torsion vectors, eliminating manual control point placement; and (4) integrated alignment and unfolding functions for fabrication-ready outputs. In an engineering case study, the module reduced modeling time by approximately 70% compared to conventional methods while achieving a root-mean-square deviation of less than 2 mm between the fitted and target surfaces. The system enables rapid generation of 3D models and 2D fabrication drawings for complex bending-torsion members, significantly enhancing detailing efficiency and precision.

1. Introduction

The advancement of modern architectural design has led to increasingly innovative and complex building forms. Contemporary structures often employ irregular, spatially curved surfaces to achieve rich artistic expression, utilizing numerous spatially bending-torsion members as seen in the Hangzhou Olympic Sports Center Stadium [1], Shenzhen Airport Terminal 3 [2], and the Shenzhen Binhua Pedestrian Bridge [3]. These members are subjected to complex loading conditions, resulting in combined internal forces of bending moments, torsional moments, and axial forces. Their design is constrained by architectural geometric requirements, connection details with adjacent members, and overall structural stability considerations.

Current research has begun addressing the challenges of 3D modeling and lofting for spatially bending-torsion members. Scandola, L. et al. [4] developed an algorithm for extracting bending-line centroids from mesh-based geometries and fitting NURBS curves, highlighting the challenge of adapting free-form bending processes by aligning parametric design targets with as-built geometries. Zhou, G.Q. et al. [5] conducted 3D lofting research using AutoCAD software, importing contour points into Tekla to generate bending-torsion plates. Chen, S.H. et al. [6] developed a method for batch extraction of 3D landscape bridge models—particularly complex curved surface geometry data—using Rhino and GH. Zhou, S.H. et al. [7] employed the spatial 3D modeling software Digital Project to establish precise 3D spatial geometric and computational models for steel structures by simulating curves with segmented straight lines. Scandola, L. et al. [8] introduced bending line reconstruction for free-form bent members using ray casting algorithms and NURBS fitting. Garba, U.H. et al. [8] generated 2D propeller curves using NURBS interpolation for smooth geometry machining.

Despite extensive research, significant limitations persist in current design workflows. For instance, general-purpose parametric platforms like Autodesk Dynamo lack specialized tools for handling complex spatial torsion, while dedicated structural software such as Tekla struggles with the accurate geometric representation of bending-torsion members [9]. The key unresolved challenges include:

- (1)

- Existing methods struggle with rapid 3D model generation for bending-torsion members on highly complex architectural surfaces, particularly regarding member alignment with building envelopes and between members with varying cross-sectional heights.

- (2)

- Limited research exists on generating variable-section members according to relevant standards, unable to realistically simulate positional changes within complex spatial structures.

- (3)

- Current approaches require manual addition of control points to enhance surface representation accuracy [10], as establishing functional expressions for twist angle variations remains challenging.

- (4)

- No systematic method exists for efficiently subdividing and unfolding plate surfaces of complex bending-torsion members for fabrication.

Traditional manual modeling approaches are inadequate to meet these demands, underscoring the urgent need for robust parametric modeling solutions. Current design practices indicate that Rhino and GH, along with their extensive plugins, are becoming indispensable tools for architects [11]. This paper develops a comprehensive spatial bending-torsion member detailing module based on GH that addresses these limitations. The main contributions include:

- (1)

- A novel data structure for integrated description of bending-torsion members.

- (2)

- Automated algorithms for axis smoothing, torsion control, and cross-section alignment.

- (3)

- Implementation of variable-section generation and plate unfolding functions.

- (4)

- Quantitative validation through engineering case studies.

2. Implementation Process

The construction process for complex curved structures determines the mesh division method based on different types of architectural surfaces. Structural engineers perform structural calculations and analysis to determine structural layout and member dimensions, completing the structural design. The detailed design phase for spatially bending-torsion members occurs after structural analysis is finalized, involving the design of bending-torsion members for manufacturing and fabrication [12,13,14].

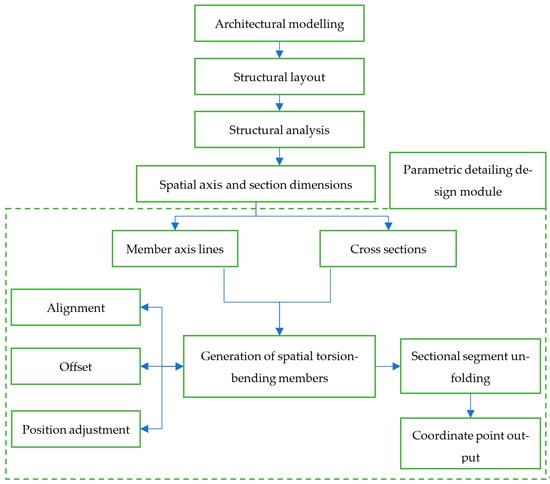

In practice, the detailed design process for spatial bending-torsion members is cumbersome, data integration is challenging, and design efficiency is low. This study proposes a parametric detailed design module for spatial bending-torsion members. Its workflow is illustrated in Figure 1. Users provide the spatial axis positions and the linear model of the architectural structure. The member generation module controls the torsion angle based on the architectural line model and creates a 3D model in Rhino. If the model meets user requirements, it can output a 3D model, 2D fabrication drawings, and a design results summary table. If the model outcome is unsatisfactory, the user can adjust structural parameters, such as section data, surface fitting accuracy, etc., to parametrically refine the model. Beyond these structural parameters, additional functionalities are available for selection. For instance, surface alignment and offset, along with section position adjustments, can all be modified through visual operations to refine the parametric model.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the parametric detailing design module.

3. Key Issues and Data Structures

3.1. Member Axis Lines

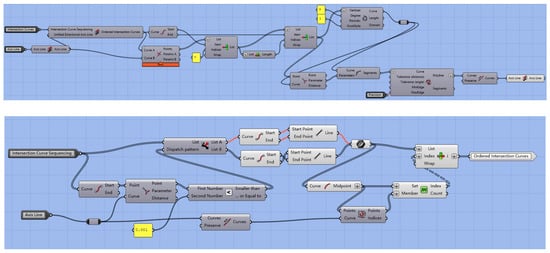

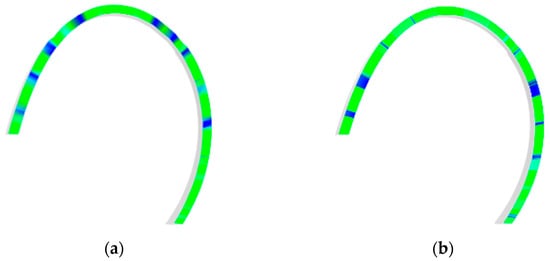

Curved members typically employ curve fitting using straight lines to approximate curves, substituting curves with straight lines between positioning control points. The precision of surface representation is influenced by the density of positioning control points—higher surface accuracy requires a greater number of positioning control points [6]. GH resolves the issue of replacing curves with straight lines between fitting curves and control points through its CurveToPolyline and Interpolate operators. Conventional data structures describe the curve, with axis data comprising segment IDs and vector directions, endpoint IDs, and their 3D coordinates. Positioning control points are selected based on structural requirements, such as the axes of intersecting members (referred to as intersecting lines), determining positioning control points. To prevent data confusion and facilitate subsequent parametric modeling, all line segments and positioning control points are sorted along the curve direction. The member axis fitting and positioning control point sorting program is shown in Figure 2. This method can enhance surface smoothness by adjusting precision, as demonstrated in Figure 3, which compares surface curvature at different precision levels in Rhino. Similar colors indicate similar curvature.

Figure 2.

Axis-fitting and control-point sorting program.

Figure 3.

Comparison diagram of surface curvature. (a) Surface curvature before precision control; (b) Surface curvature after precision control.

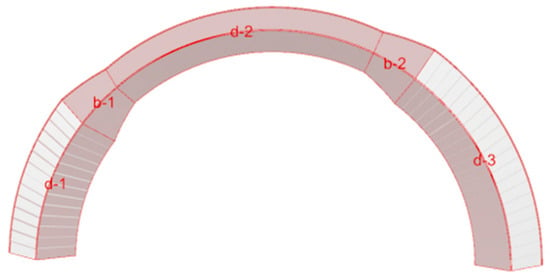

To better handle variable-section problems, variable-section members along a single axis are generated in one operation. However, the axis data requires classification processing, as shown in Figure 4. For constant-section members, the axis position is d-i; for variable-section members, the axis position is b-i. The axis position at variable-section ends relates to the constant-section dimensions at both ends. To avoid data duplication, the axes generating bending-torsion members are divided into two data structures: the variable-section end axis is merged with the subsequent constant-section axis segment along the axis direction into one data structure, as shown in Figure 4. The member axes b-1 and d-2 are defined as Group A1, while b-2 and d-3 form Group A2. The initial constant-section axis is designated as Group B, with d-1 defined as Group B1. For implementation, first select the axis segments requiring different cross-sectional dimensions in Rhino. After generating the bending-torsion member model, preview the results directly in Rhino and adjust parameters to modify the generation positions of models with varying cross-sectional dimensions. Regardless of the complexity of the bending-torsion member’s cross-sectional dimensions, the spatial positioning of the member’s cross-section can be achieved by defining the A and B data structures to adjust the cross-section and generate the variable cross-section.

Figure 4.

Data of the member axis.

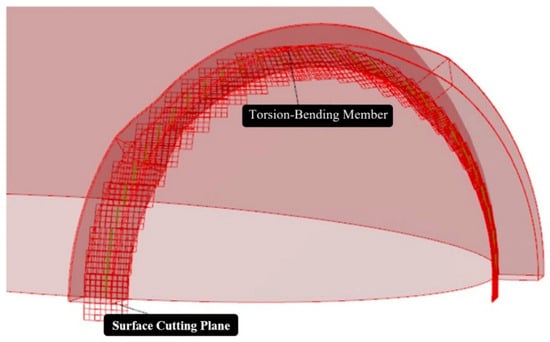

3.2. Bending-Torsion of Members

Generating bending-torsion plate assemblies requires controlling torsional angle errors. The current common approach involves using AutoCAD software to draw the edge lines of bending-torsion plates, then repeatedly dividing them to generate contour points for the plates. These points are imported into Tekla software, where the triangle generator is used to click along the outer contour points one by one, generating the plates of the bending-torsion members [15]. While AutoCAD offers high precision for detailing, it suffers from low efficiency and high error rates. Even when combined with Tekla software, the process remains labor-intensive, requiring individual generation and rotation of each bending-torsion member. Leveraging GH surface generation capabilities, surface-cutting planes can be obtained through the EvaluateSurface operator. As shown in Figure 5, this represents the architectural surface cutting plane data set at the axial interpolation points of the bending-torsion member. By using the architectural surface plane as the reference plane for the bending-torsion member and assuming the side of the bending-torsion member is parallel to the architectural surface plane, the bending-torsion member can be generated efficiently. This approach resolves issues such as eliminating angular discrepancies at member connections and insufficient surface fitting accuracy.

Figure 5.

The tangent plane of a surface.

3.3. Constant Cross-Section vs. Variable Cross-Section

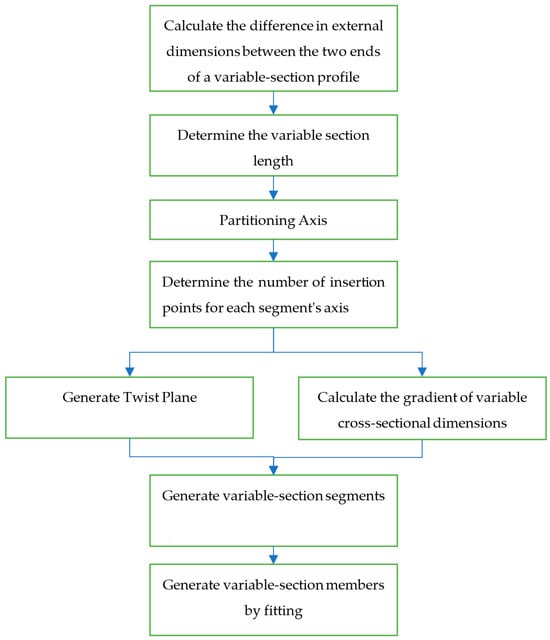

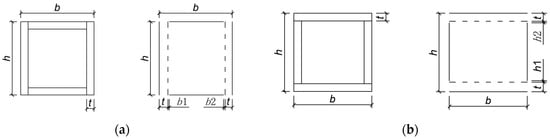

Considering plate thickness but disregarding its impact on processing deformation, the outer surface of the plate serves as the reference plane to replace the plate itself. Generating constant cross-sections is relatively straightforward. Figure 6 illustrates the process for generating variable cross-sections. Taking a rectangular cross-section as an example, a data structure is established to describe cross-sectional dimensions. Rectangular cross-section data includes cross-sectional height h, cross-sectional width b, and plate thickness t. Considering welding and the actual spatial placement of the member, two cutting and assembly methods exist for rectangular cross-sections [16]: Cross-section Type 1 (Figure 7a) and Cross-section Type 2 (Figure 7b). For Section type 1, the width b is determined by shortening the top and bottom plate widths while maintaining the original rectangular dimensions and plate thickness. Welding assembly gaps b1 and b2 are set between the side plates and top plate to simulate weld widths. Similarly, for Section type 2, welding assembly gaps h1 and h2 can be set for the section height. The selection between these types involves optimization based on welding complexity, architectural surface requirements, and the principal direction of sectional variation.

Figure 6.

Flowchart for generating variable-section profiles.

Figure 7.

Cross-section type. (a) Type 1; (b) Type 2.

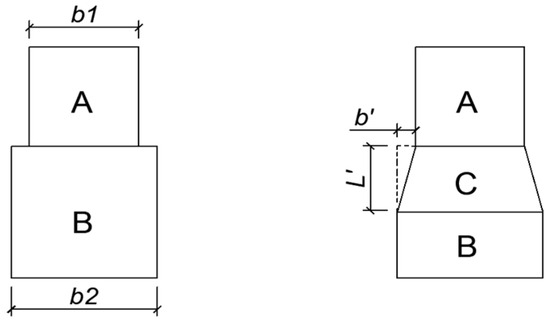

In structural design, the full-stress design method is often employed. Sections with higher internal forces are designed with larger cross-sections, while sections with lower internal forces use smaller cross-sections. Variable cross-sections are used to transition between the larger and smaller sections. As shown in Figure 8, this module generates the variable-section segment together with Section B of the member. Considering the maximum dimensional difference b, h, and t between the end sections, Figure 8 illustrates the dimensional difference b’ in the b-direction between Section A and Section B. The length L’ of the variable-section segment is determined by presetting the slope p = L’/b’, and the two members are connected using center alignment.

Figure 8.

Variable cross-sectional shape and size.

3.4. Partitioning Surfaces and Unfolding

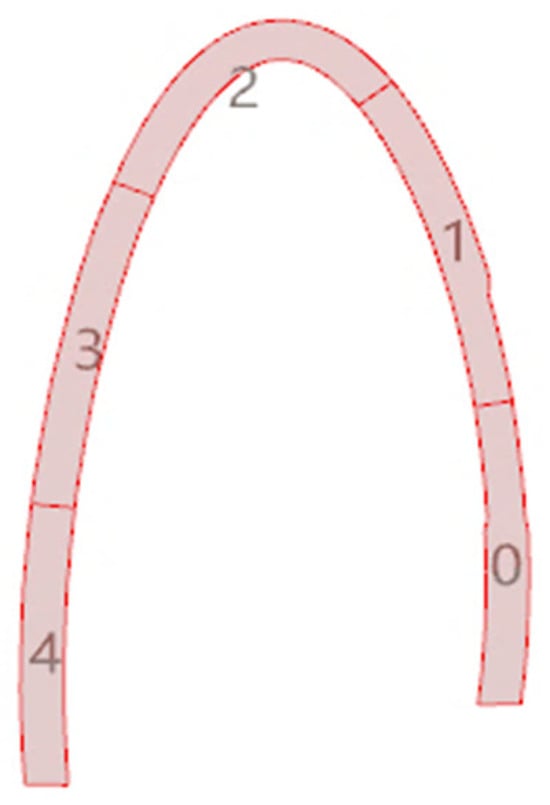

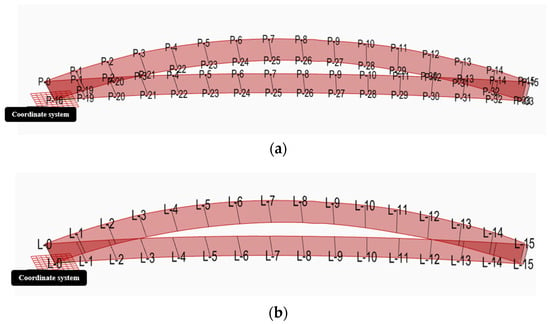

Bending-torsion members in architectural structures are typically steel members fabricated from flat steel plates and assembled into spatial bending-torsion forms. The process of unfolding a spatial surface into a plane and then lofting from the plane back to a spatial surface poses a significant challenge. Rhino inherently possesses robust planar unfolding capabilities, and through its GHPython Script functionality, batch unfolding of spatial surfaces can be achieved. Taking a rectangular-section bending-torsion member as an example, to prevent the four plate sections of the rectangular cross-section from meeting at the same position, it is necessary to achieve a reasonable segmentation of the four spatial surfaces. Figure 9 shows one side plate section of a rectangular-section spatial curved-twisted member. According to cutting requirements, it is divided into five equal parts, while the remaining sides are divided with staggered joints. This ensures that the four plate sections on different cross-sections can be assembled without meeting at the same position [17,18]. For feature lofting from planar to spatial curved surfaces, the lofting data must correlate the planar data of the feature’s unfolding pattern with the 3D data of its spatial curved surfaces. By forming a plane with the endpoints of each surface’s shortest edge and the midpoint of another short edge, and then placing this plane onto the corresponding unfolding pattern’s working plane using the Orient operator, precise spatial surface lofting is achieved, facilitating machining. Figure 10 shows the unfolding and lofting diagram for a side panel of a twisted member. The lofting data includes the spatial surface and corresponding measurement line numbers (L-i) and endpoint numbers (P-i) on the unfolding diagram, along with their spatial coordinates in the reference coordinate system.

Figure 9.

Surface segmentation.

Figure 10.

Segmentation surface and unfolding measurement. (a) Number of Measurement Line Endpoint; (b) Number of Measurement Line.

4. Key Algorithms

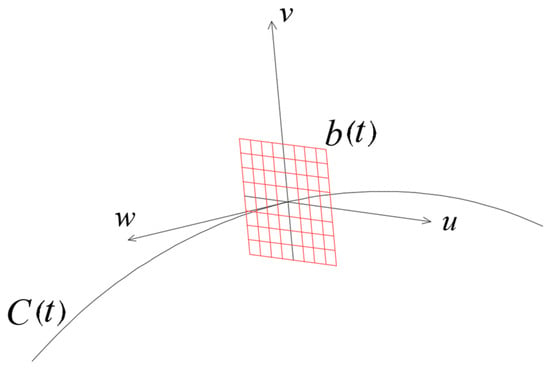

4.1. Determination of Section Method Planes at Interpolation Points Along Member Axes

The spatial axes of bending-torsion members are typically described by non-uniform rational B-spline (NURBS) curves defined through n given fitting points. Let its curve equation be C = C(t), where t (0 < t < 1) and i = 0, 1, 2, …, n, as shown in Equation (1). T = 0 and t = 1 correspond to the curve’s start and end points, respectively.

In the equation, Pi denotes the curve control point; Wi represents the weight corresponding to the control point; Ni,3(t) is the basis function of the cubic NURBS.

When fitting the curve using interpolation points Pi, the distances between interpolation points are often irregular. This leads to excessively large weights Wi for certain interpolation points Pi, resulting in a fitted member surface that lacks smoothness and naturalness. Artificially adding interpolation points can mitigate this issue, but it compromises efficiency and increases error. Therefore, this paper automatically increases interpolation points to

based on maximum spacing m, analyzing slope changes to ensure uniform, smooth spacing, as shown in Equation (2).

where , Li denotes the spacing between original fitted curve control points.

This approach preserves the original interpolation points while ensuring a smooth and natural transition of the generated member surface.

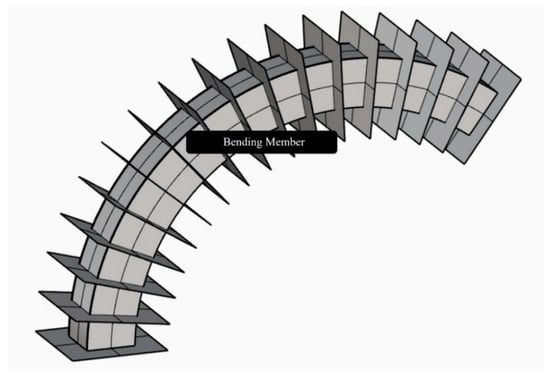

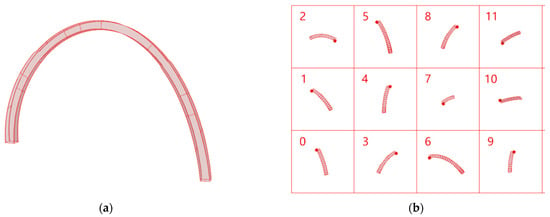

At any point Pi on the curve, a local coordinate system exists with Pi as its origin. Its u, v, and w vectors represent the tangential direction, principal normal direction, and secondary normal direction of the curve at that point, respectively. Using the PerpFrame operator in the GH, the normal plane at any point along the member axis can be obtained, i.e., the working plane b(t) defined by u and v, as shown in Figure 11. when curvature approaches zero, the algorithm adopts the normal vector from the previous interpolation point to avoid coordinate system failure. Place the cross-section on the normal plane at the interpolation point Pi of the fitting curve. As t varies from 0 to 1, the space swept by the cross-section fixed on the initial plane forms the spatial curved entity i. Multiple curved entities can be assembled to create the entire curved member, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 11.

Local coordinate system and normal plane of interpolation points.

Figure 12.

Bending member model.

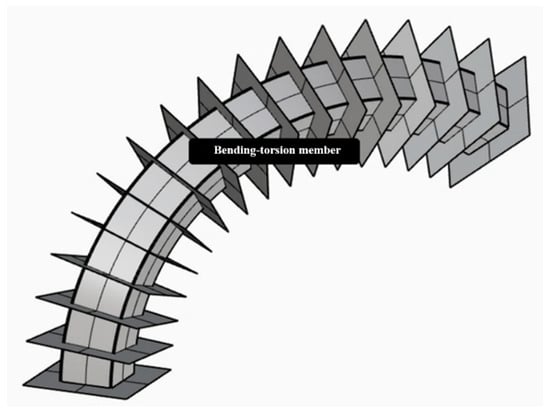

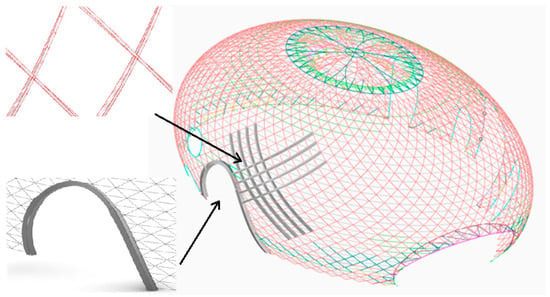

4.2. Determination of Principal Normal Vectors for Member Axis-Based Planes

As shown in Figure 11, a tangent plane to the surface at the member axis on an ellipsoid is obtained. The normal vector of this tangent plane is the principal normal vector vi(t) of the cross-section. For the curved member described above, if the principal normal vector in the plane coordinate system bi(t) is replaced with the calculated vi(t) (where 0 < t < 1), the cross-section rotates along the normal plane while sweeping along the member axis as vi(t) varies with the member axis parameter t. This configuration forms a spatially bending-torsion member, as illustrated in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Bending-torsion member model.

The transformation from surface normal ns to section rotation is shown in Equation (3).

where θ is the torsion angle of the cross-section.

4.3. Alignment and Offset of Cross-Sections

In practical engineering, bending-torsion members with different cross-sectional dimensions often require cross-sectional alignment. As shown in Figure 14b, when the centers of the two cross-sections are aligned, the right side of Section B in the b-direction aligns with the right side of Section A in the b-direction. Based on the geometric parameters of the member axis, the normal plane can be derived as a function of vi(t). By placing the cross-section on this normal plane, a spatial bending-torsion model of a multi-segment constant-section beam element can be established. The overall model offset is achieved by shifting the position of sections on the normal plane by the same distance along the u and v directions of the normal plane. The formation location of variable sections is determined based on engineering requirements, specifying both the variable section position and alignment method. Therefore, the start and end points of variable sections must account for scenarios where they do not coincide with curve interpolation points. In such cases, data for the start and end points of variable sections must be added to the existing curve interpolation points. Using the cross-sectional dimensions at both ends, the slope, and the spatial positions of interpolation points within the variable cross-section range, as shown in Equation (4), the variable cross-section dimensions at the plane positions of the interpolation points are obtained. Subsequently, the linearly varying variable cross-section surface portion is generated.

where Hi represents the cross-sectional data of interpolation points within the variable cross-section range, such as height h; H0 denotes the cross-sectional dimension data at the start of the variable cross-section; H1 denotes the cross-sectional dimension data at the end of the variable cross-section; ki/k represents the ratio of the distance from the start point to the interpolation point i to the total length of the variable cross-section curve.

Figure 14.

Section placement situation. (a) Center alignment of cross-section; (b) Alignment method.

This linear interpolation method assumes gradual curvature variation. For highly curved segments, additional interpolation points must be inserted to maintain accuracy. In actual structures, highly curved segments often experience significant stress concentrations, making them generally unsuitable for variable cross-sections from both a fabrication and structural performance perspective.

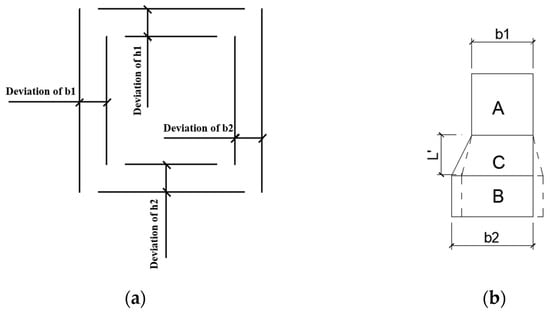

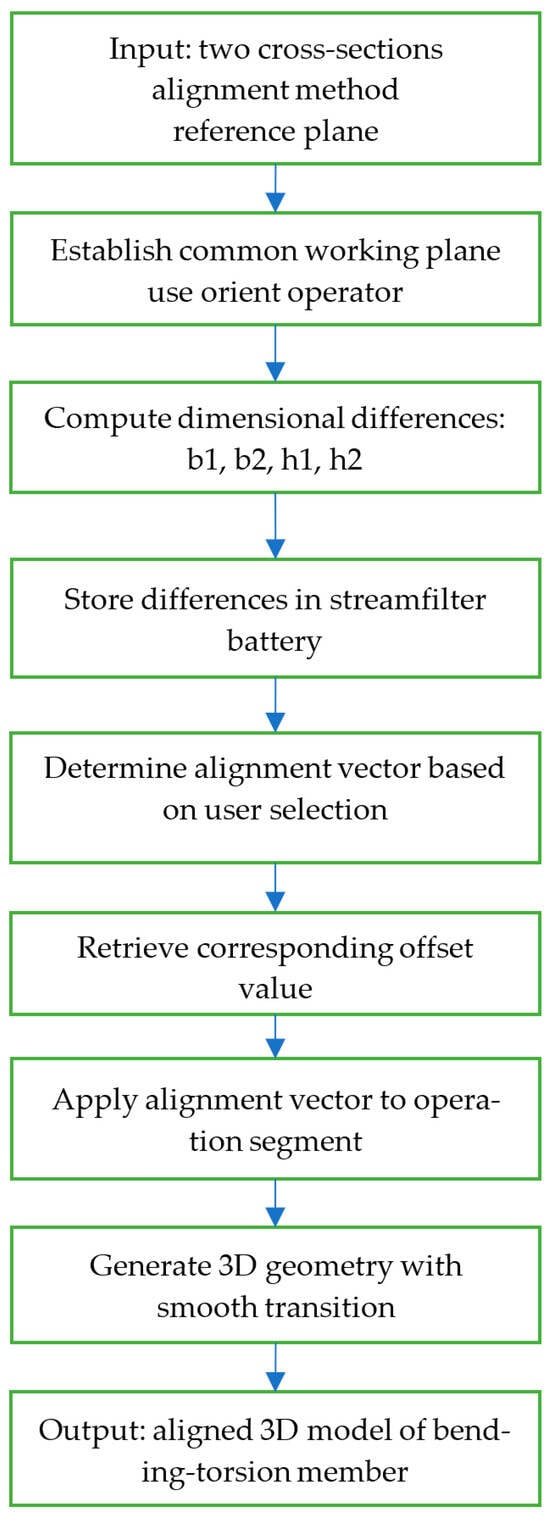

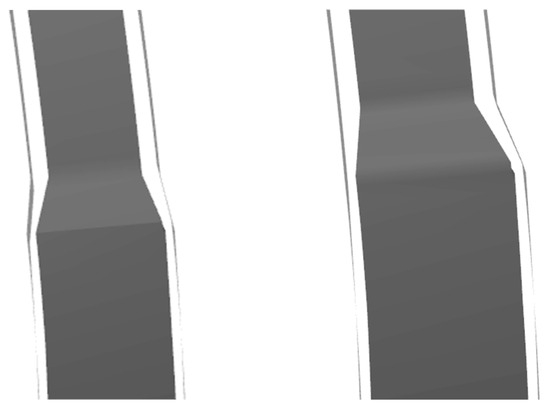

After generating the variable-section and constant-section segments as described above, the alignment function must further determine the operation segment and alignment vector. Determining the alignment vector requires defining both its direction and magnitude (offset distance). Calculate the cross-sectional dimensions before and after the variable section. Then, based on the cross-section type specified in the parameter information, determine the assignment of data in both directions.

For rectangular cross-sections, each direction (B and H) has two faces. After defining the alignment data for both B and H directions, the alignment vector and operation segment are identified through user-selected reference planes and parameter inputs. In engineering practice, multiple alignment reference planes often exist, enabling simultaneous alignment in both B and H directions.

To enhance the module’s robustness and expand alignment application scenarios, when calculating the difference between variable cross-section dimensions, the Orient operator in GH software is utilized. This places both cross-section dimensions on the same working plane to compute the cross-section dimension differences: b1, b2, h1, and h2, as shown in Figure 14a. These four-dimensional differences are stored in a StreamFilter battery block, which allows the module to dynamically retrieve the correct offset value based on the real-time spatial relationship between the sections. The implementation process is shown in Figure 15. Based on the proposed method, the comparison results after selecting different alignment approaches are shown in Figure 16.

Figure 15.

Flowchart of algorithm for cross-section alignment.

Figure 16.

Alignment effect of different cross-sections.

5. Engineering Applications and Validation

Figure 17 depicts a concert hall featuring an ellipsoidal grid shell structure. Both the entrance section and exterior members comprise spatially bending-torsion elements. The entire elements align with the architectural outer surface. Taking the generation of the entrance’s spatially bending-torsion steel members as an example for detailed design, these members consist of two cross-sectional dimensions: Section 1: 800 mm × 800 mm × 20 mm, Section 2: 600 mm × 600 mm × 16 mm.

Figure 17.

An ellipsoidal grid shell structure composed of bending-torsion members.

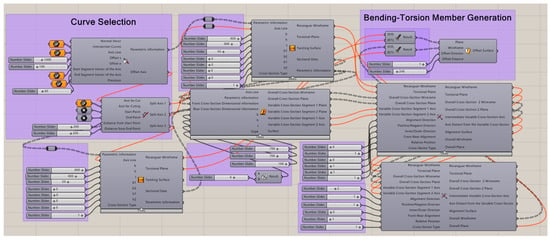

The detailed design module for battery packs developed based on GH is shown in Figure 18. The torsion angle of the bending-torsion member is determined by the input architectural surface plane. Spatial axes located on the architectural surface plane are selected to define the position of the bending-torsion member. Selecting the cutting points of the axes on the spatial axes will divide the original spatial axes into axes with different cross-sectional dimensions where the bending-torsion members are located, thereby determining the spatial position of the variable cross-section.

Figure 18.

Program batteries of the detailed design module.

The comparison between single-section members and multi-section members after determining variable-section spatial positions is shown in Figure 19a. The height of the spatial axis endpoints relative to the ground can be adjusted by altering the axis offset height. The position of variable sections can be fine-tuned by adjusting the offset distance of the cutting points. The comparison diagram after adjusting variable-section positions is shown in Figure 19b. The member’s cross-section dimensions, alignment data, and offset data form a one-to-one correspondence with the array of cut axes. By editing the Excel data into text that can be inserted into the Panel cell, all bending-torsion members can be generated at once within the GH software.

Figure 19.

Model generation detail. (a) Cross-section Comparison Diagram; (b) Variable Section Position Comparison Diagram.

Excessively long plate sections complicate machining, necessitating longitudinal segmentation. To prevent stress concentration and welding distortion from longitudinal butt welding at identical plane positions, different segmentation ratios may be applied to the four plate sections. For example, when proportionally dividing the four surfaces forming the model—front curved surface, rear curved surface, upper curved surface, and lower curved surface—the front curved surface is divided according to (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1), the rear curved surface according to (0.15, 0.35, 0.45, 0.75, 1), the upper curved surface according to (0.1, 0.3, 0.55, 0.7, 0.85, 1), and the rear surface at (0.25, 0.5, 0.65, 0.9, 1).

These ratios are determined based on welding specifications and finite element analysis. Measurement lines are applied based on the maximum dimension of 500 mm. Surface division and unfolding are shown in Figure 20.

Figure 20.

Surface segmentation and unfolding layout diagram. (a) Surface segmentation; (b) Unfolding layout diagram.

To quantify method precision, we compared the fitted member axis with the target architectural surface. The calculated root-mean-square deviation was less than 2.0 mm. Maximum torsion angle error was 0.5°, sufficient for architectural steel structure requirements. Compared to conventional workflows [15], our method reduced modeling time by approximately 70% for equivalent complexity members. Rhino’s unfolding tools introduced maximum flattening errors of 1.2 mm, within acceptable fabrication tolerances for steel structures.

The fabrication and construction of variable-section bending-torsion members entail significant practical challenges. Manufacturing complexity arises from the need to precisely cut and form steel plates with continuously varying dimensions. On-site assembly necessitates precise temporary support systems and advanced surveying to ensure the correct spatial alignment of each segment. Welding between variable sections demands highly skilled workers and strict quality control due to the intricate node geometries. Feedback from an industrial partner quantified substantial efficiency gains: approximately 70% faster drafting, 40% less design rework, and a 15% reduction in material waste. These metrics underscore the module’s immediate practical value.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a parametric detailed design methodology for spatially bending-torsion members on complex architectural surfaces, establishing key issues, data structures, and core algorithms. The main conclusions are:

- (1)

- The proposed data structure accurately describes member axis geometry, twist angle, cross-sectional shape, subdivision surfaces, and unfolding pattern positioning coordinates, enabling parametric generation of spatially bending-torsion members. Upon design completion, positioning point coordinates and unfolding layout information are automatically generated, facilitating fabrication drawing production.

- (2)

- Using architectural surface normal vectors as member torsion vectors, combined with automated interpolation point generation based on curvature variation, enhances surface smoothness of curved-torsional members. For rectangular sections, a multi-segment cross-section model replaces traditional plate-shell elements, improving representation accuracy.

- (3)

- The developed detailed design module enables integrated member model generation based on curve positions and cross-sectional dimensions. Models can be aligned, offset, or modified as needed, achieving rapid mass production of bending-torsion member models. Engineering validation confirms the module’s performance, achieving root-mean-square deviations under 2 mm and reducing modeling time by approximately 70% compared to conventional workflows.

The current method assumes linear cross-section variation, which may require additional interpolation points for highly complex curvature changes. Future research will explore adaptive interpolation strategies and integration with structural analysis for optimized cross-section design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W. and J.Z.; methodology, H.W. and J.W.; software, H.W. and J.W.; validation, J.W.; formal analysis, H.W.; investigation, J.W.; resources, J.Z. and J.L.; data curation, J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W. and J.W.; writing—review and editing, J.Z.; supervision, H.W.; project administration, J.Z.; funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Henan Provincial Key Research and Development (R&D) Plan Project—Research and Development of Integrated Industrial Technology for Steel Bridge Design and Intelligent Construction, grant number: 231111241500.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jingtao Wang is employed by the company Chery Automobile Co., Ltd. Author Jianquan Lin is employed by the company Zhengzhou Baoye Steel Structure Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Li, H.; Liu, J.P.; Li, J.; Wei, W.; Shan, W.C. Intelligent optimization method for complex steel structures based on internal force state. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2024, 218, 108732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbig, T.; Scheible, F.; Kamp, F.; Schieber, R. Engineering in a computational design environment—New Terminal 3 at Shenzhen Bao’an International Airport, China. Steel Constr. 2014, 7, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Chen, W.N. Study and application of Deepening of landscape bridge steel structure. In Proceedings of the 2022 Industrial Architecture Academic Exchange Conference, Beijing, China, 14 October 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Scandola, L.; Erber, M.; Hagenlocher, P.; Steinlehner, F.; Volk, W. Reconstruction of the bending line for free-form bent components extracting the centroids and exploiting NURBS curves. Graph. Models 2024, 135, 101227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.Q.; Zhou, J.H.; Li, K.J. Detailed design technology of steel structure for a large foreign airport terminal. Prog. Steel Build. Struct. 2018, 20, 103–108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.H.; Yu, Z.G.; Zhou, H.; Li, R.Q. Batch extraction of 3D model data of landscape bridge based on rhino Grasshopper. J. Chongqing Jiaotong Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 42, 1–7+28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.H.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Qi, W.H.; Shu, W.N.; Zhang, S.Z. Structural design on the project of phoenix international media center. Build. Struct. 2011, 41, 56–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Garba, U.H.; Wang, T.Y.; Dong, T.C.; Tian, Y.; Kang, J.; Tian, C. Enhancing propeller design with freeform contours through NURBS interpolation for 2D fabrication, CAD/CAM for 3D production, optimized with Taguchi method and artificial neural network. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 107069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.J.; Fan, L.; Guo, K.G.; Xi, R.; Wu, Y.; Pan, S. Application of detailed design technology in space bending steel structure in Meixi lake city island project, Changsha. J. Green Sci. Technol. 2016, 18, 126–128. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.M.; Dong, W.G.; Zhao, P.F.; Zhao, P.F.; Song, T.; Ye, C.J. Parametric modeling and analysis of steel roof structure of an exhibition center. Build. Sci. 2019, 35, 1–6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.; Wang, C.L. Applying of Rhinoceros software and Grasshopper plug-in for quick structural modeling of double-layer reticulated shells. Build. Struct. 2012, 42, 424–427. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.N.; Guo, X.N.; Ou, Y.H.; Zhu, S.J.; Luo, X.Q. Detailed design system and key algorithms of aluminum alloy shells with gusset joints based on Grasshopper platform. J. Build. Struct. 2023, 44, 246–254. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.H.; Coblence, T.; Zhu, S.J.; Luo, X.Q. Development of a design system of shells with aluminum alloy gusset joints based on multi-platforms. Prog. Steel Build. Struct. 2019, 21, 80–88. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Hu, Q.; Lu, J. Parametric design of Cuanjian pavilion based on dynamo programming. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. (Nat. Sci.) 2021, 53, 247–253. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhu, C.; Sui, X.D.; Song, S.Q. The detailed design technology of complex steel structure for the contemporary art museum and city planning exhibition in Shenzhen. Constr. Technol. 2016, 45, 21–25. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y.K.; Liu, C. The construction technology of freeform surface spatial bending-torsion steel structure. J. World Archit. 2022, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, H.; Lu, Z.H.; Wang, L.T.; Wang, S.Z. Research and application of manufacturing methods for small section rectangular bending and torsion components. Ind. Constr. 2023, 53, 246–249. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.Y.; Ge, X.L.; Shi, R.J. Prefabrication technology of bending-torsion box-shape member of steel ribbon in kunming new airport terminal. Archit. Technol. 2011, 40, 14–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).