Low-Temperature Synthesis of EPEG-Based Superplasticizers: Kinetic Optimization and Structure–Property Relationships

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Conventional synthesis typically relies on vinyl alcohol-based macromonomers which exhibit low reactivity, necessitating energy-intensive high-temperature processes (60–90 °C). Such conditions often induce side reactions that compromise molecular uniformity. Furthermore, there is a lack of systematic research elucidating how key process parameters regulate the microscopic structure and macroscopic performance of EPEG-based PCEs synthesized at low temperatures.

- Leveraging the high reactivity of the vinyloxy double bond in EPEG, this study establishes a robust low-temperature (20 °C) synthesis protocol that achieves high conversion (>95%) with significantly reduced energy consumption. By systematically varying five key process parameters, a clear “synthesis–structure–property” relationship is constructed. Crucially, the weight-average molecular weight (Mw) is identified as the central regulator that balances initial dispersion and slump retention, mediated by mechanisms involving adsorption behavior and pore solution surface tension.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Low-Temperature Synthesis of EPEG-PCEs

2.3. Molecular Structure Characterization

2.4. Performance and Mechanism Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

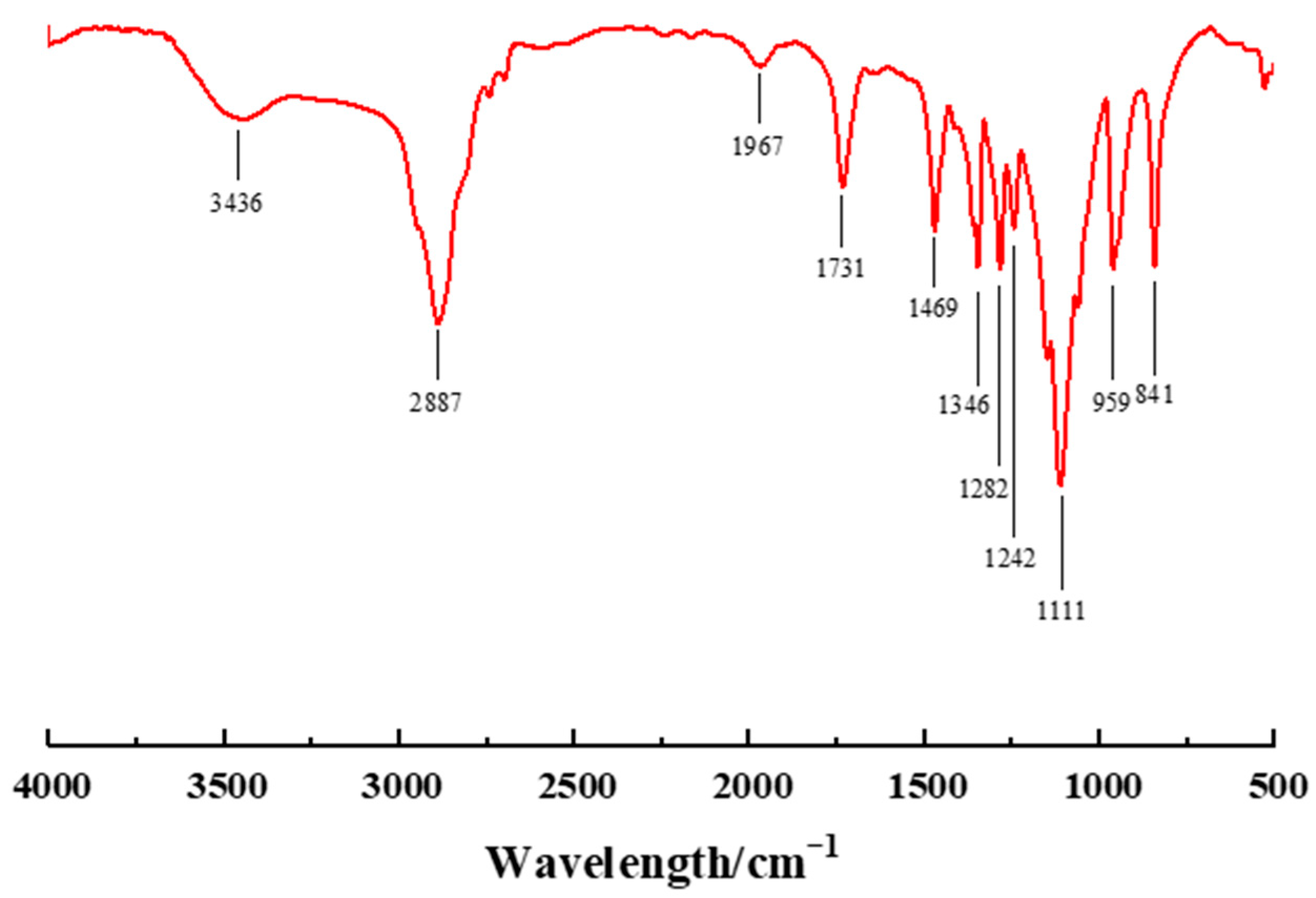

3.1. Structural Confirmation of PCE Copolymers via FTIR

3.2. Regulation of Molecular Structure and Dispersion Performance via Process Parameters

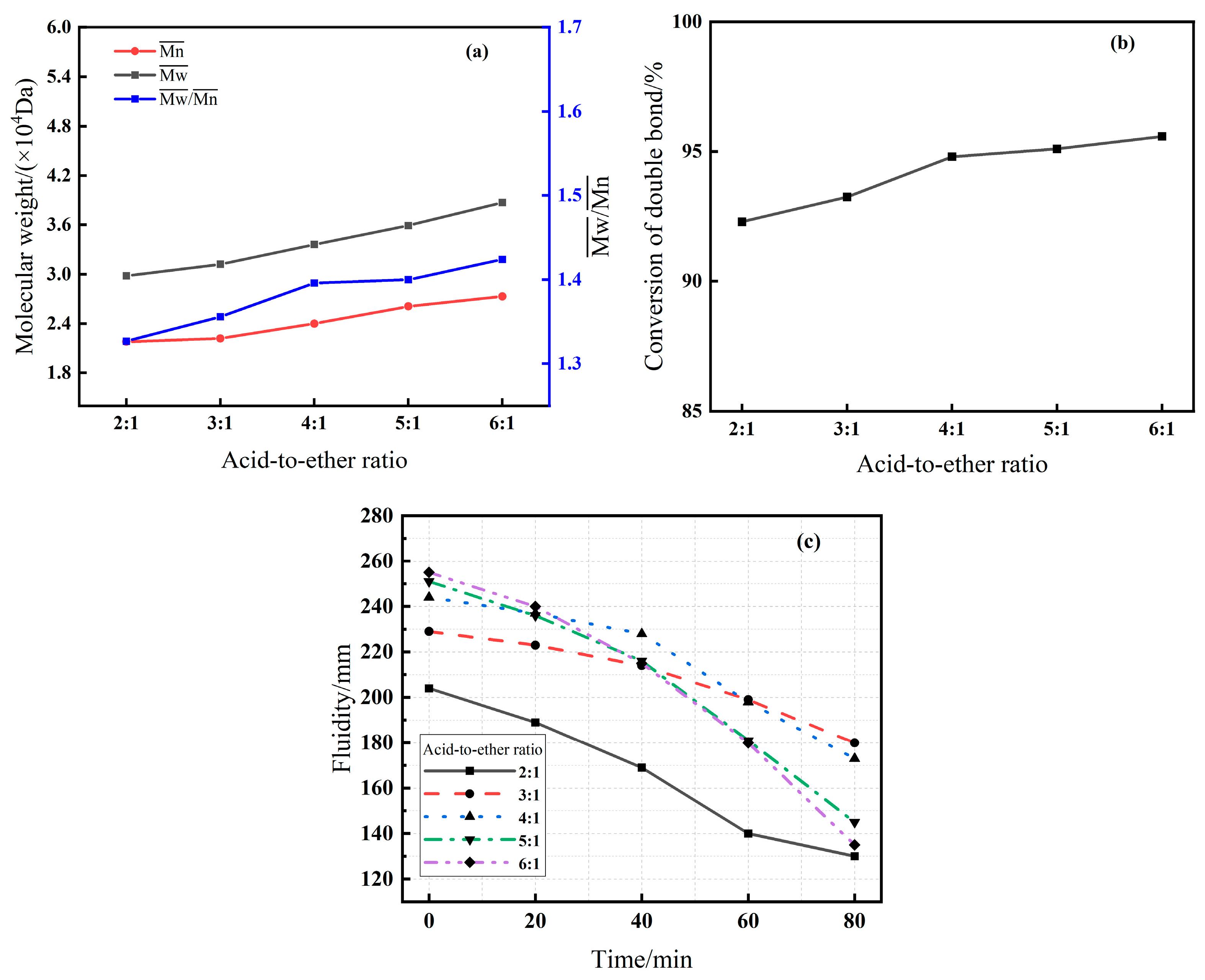

3.2.1. Effect of Acid-to-Ether Molar Ratio (Series A)

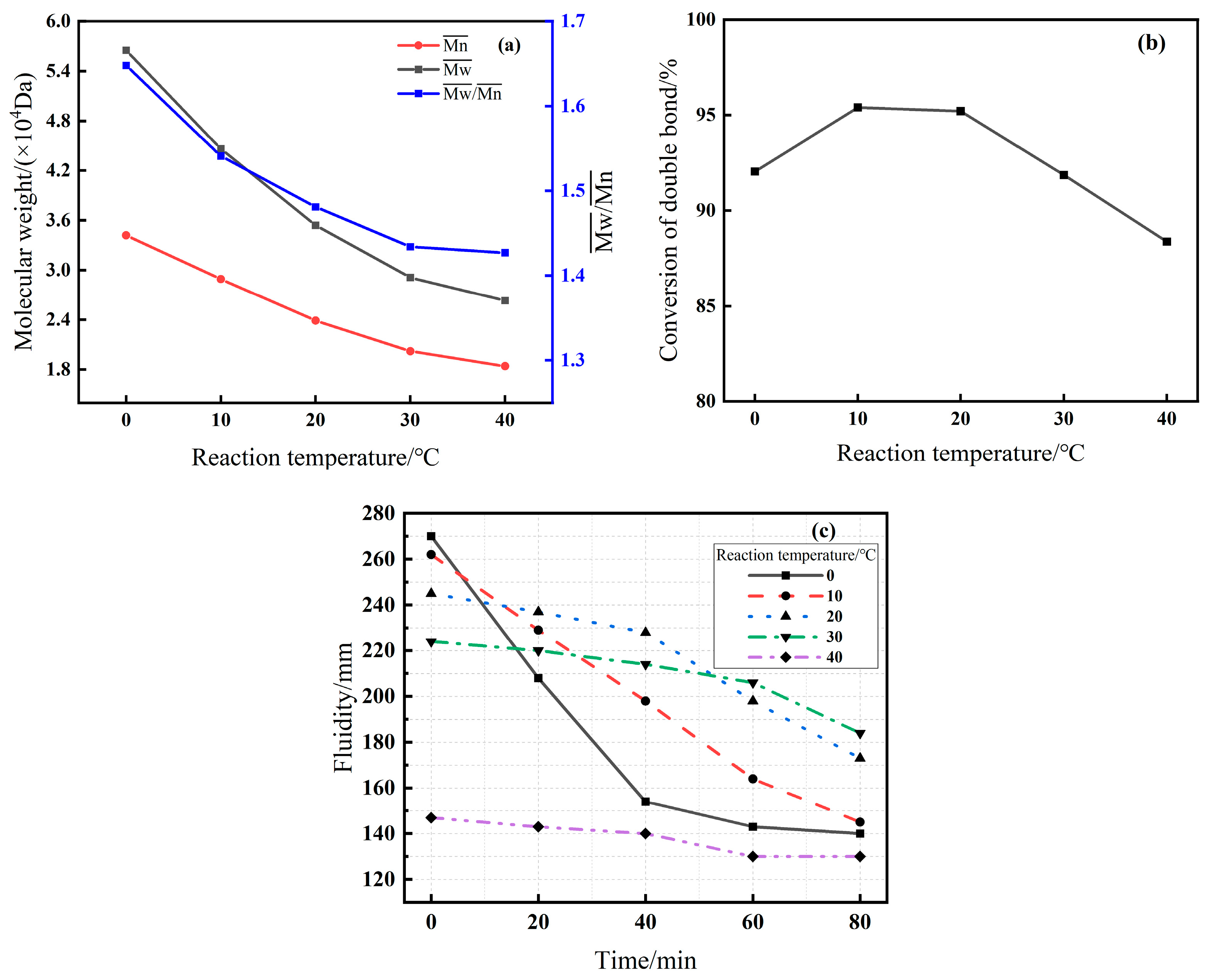

3.2.2. Effect of Reaction Temperature (Series B)

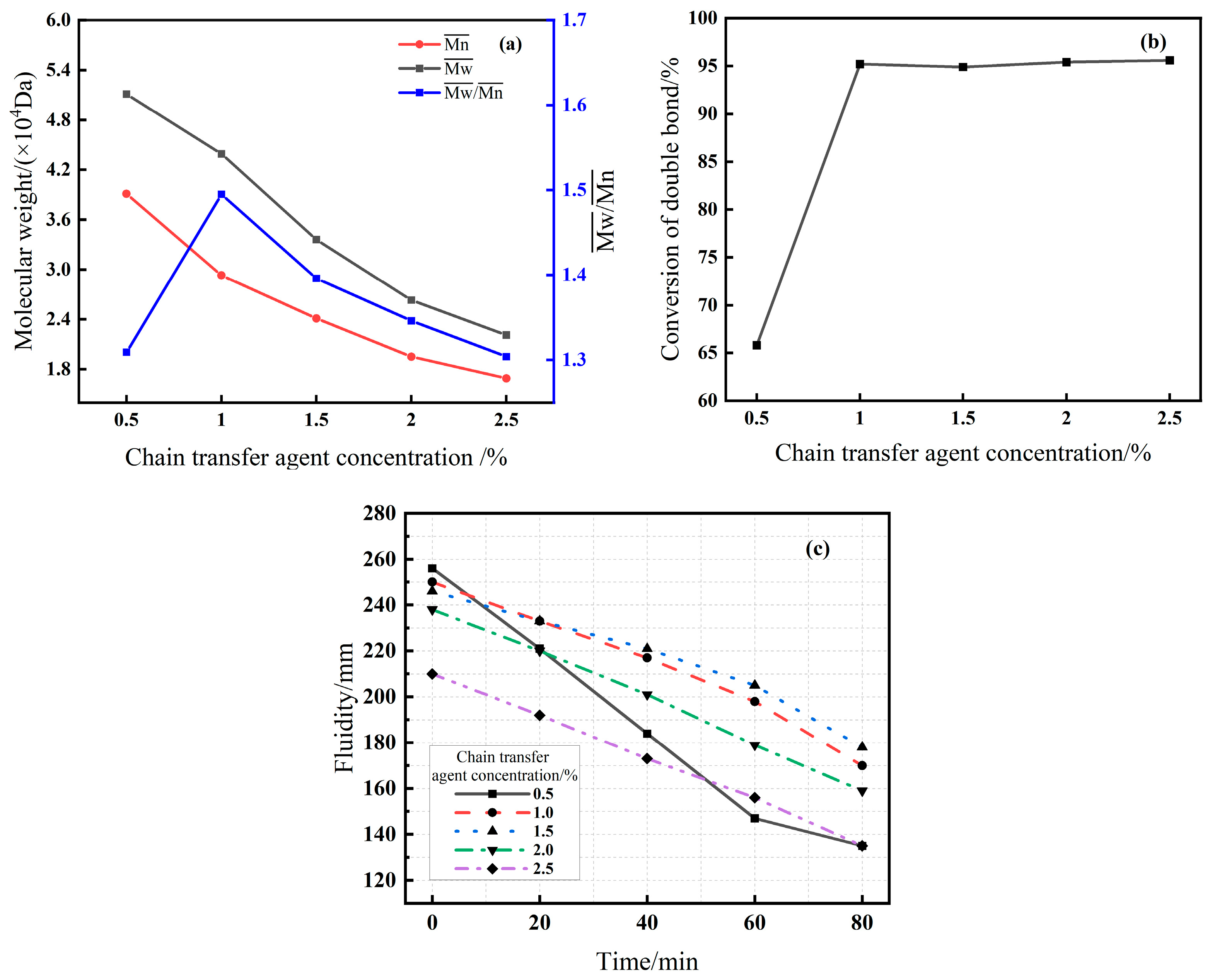

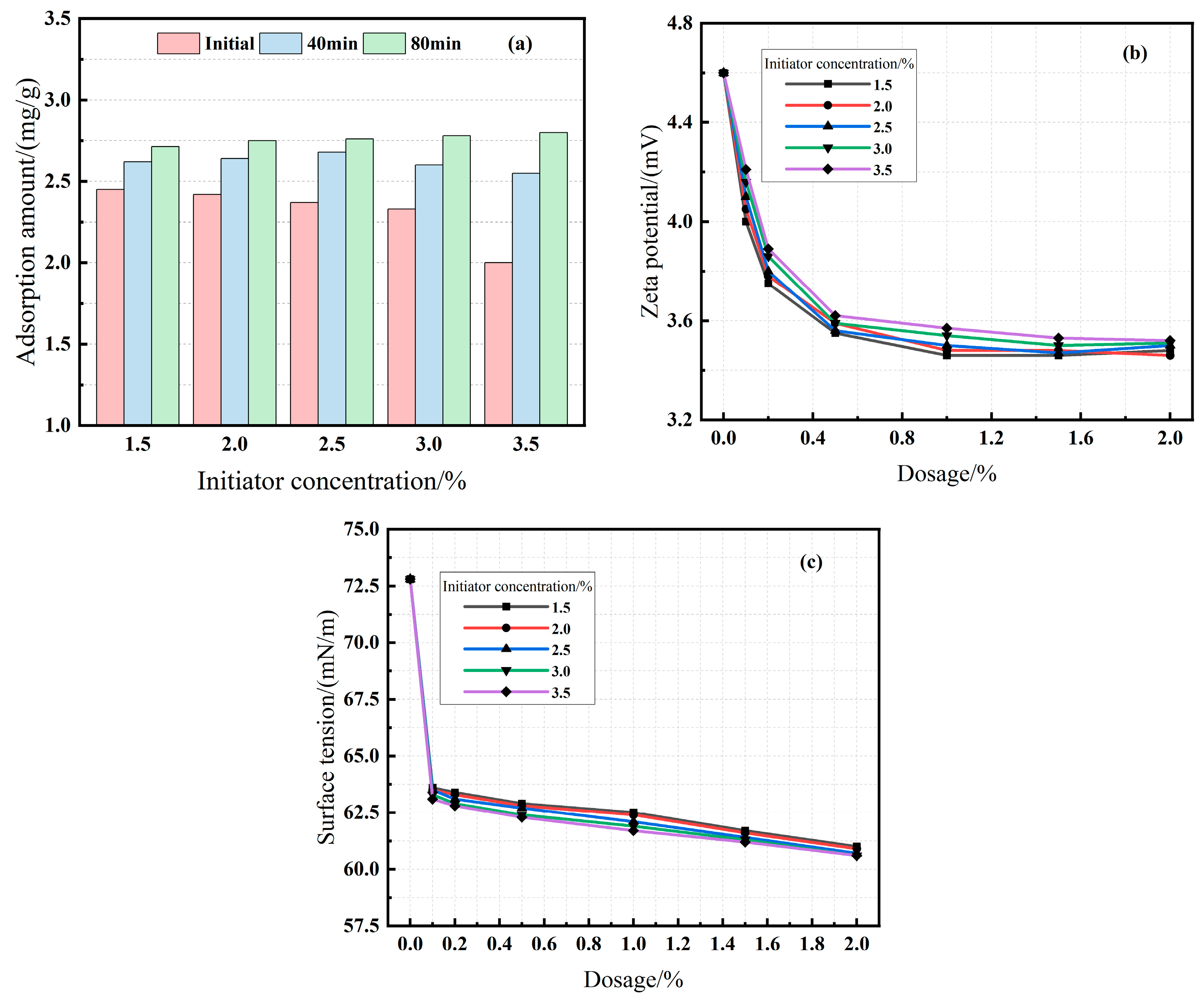

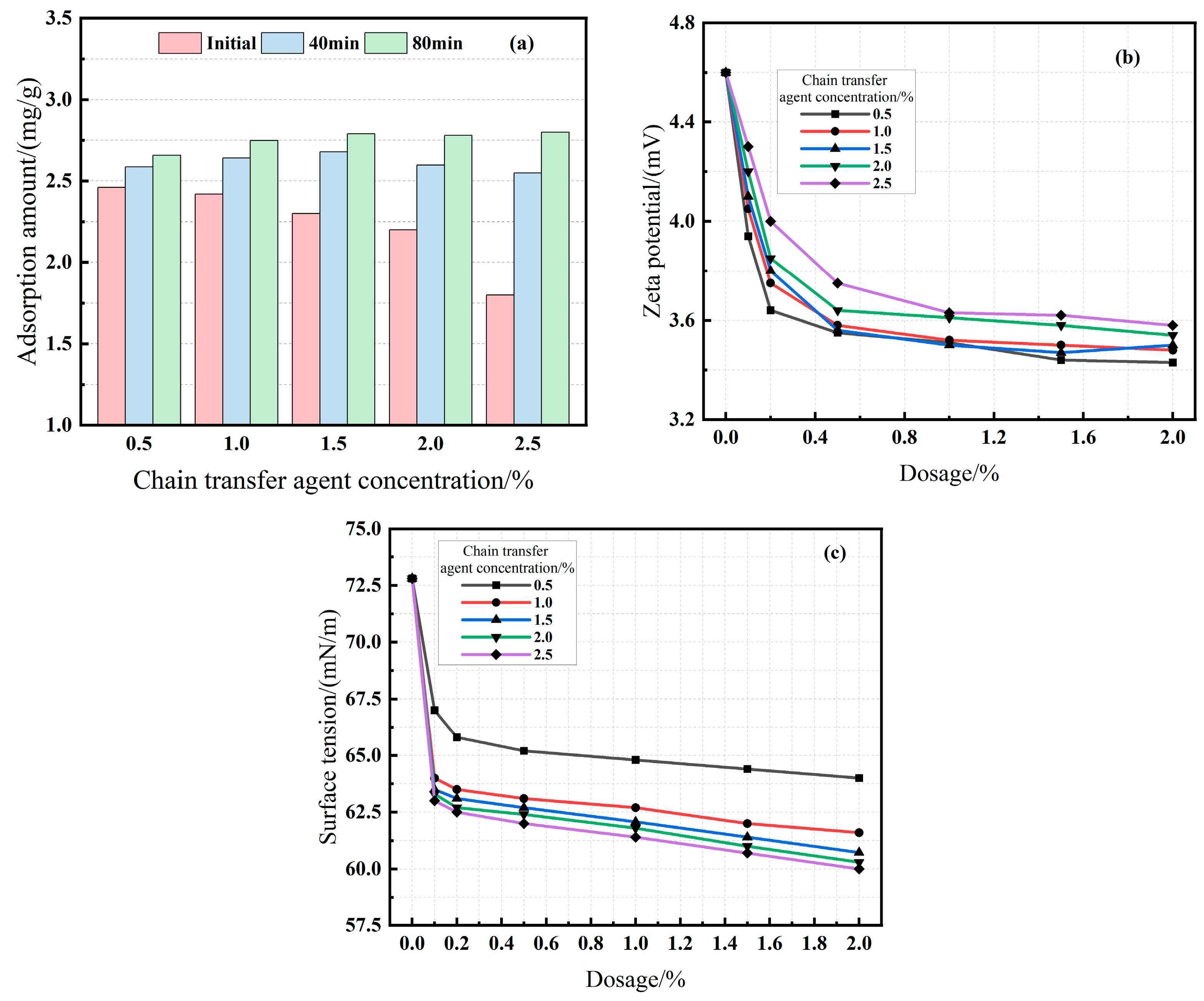

3.2.3. Effect of Initiator and Chain Transfer Agent Dosage (Series C & D)

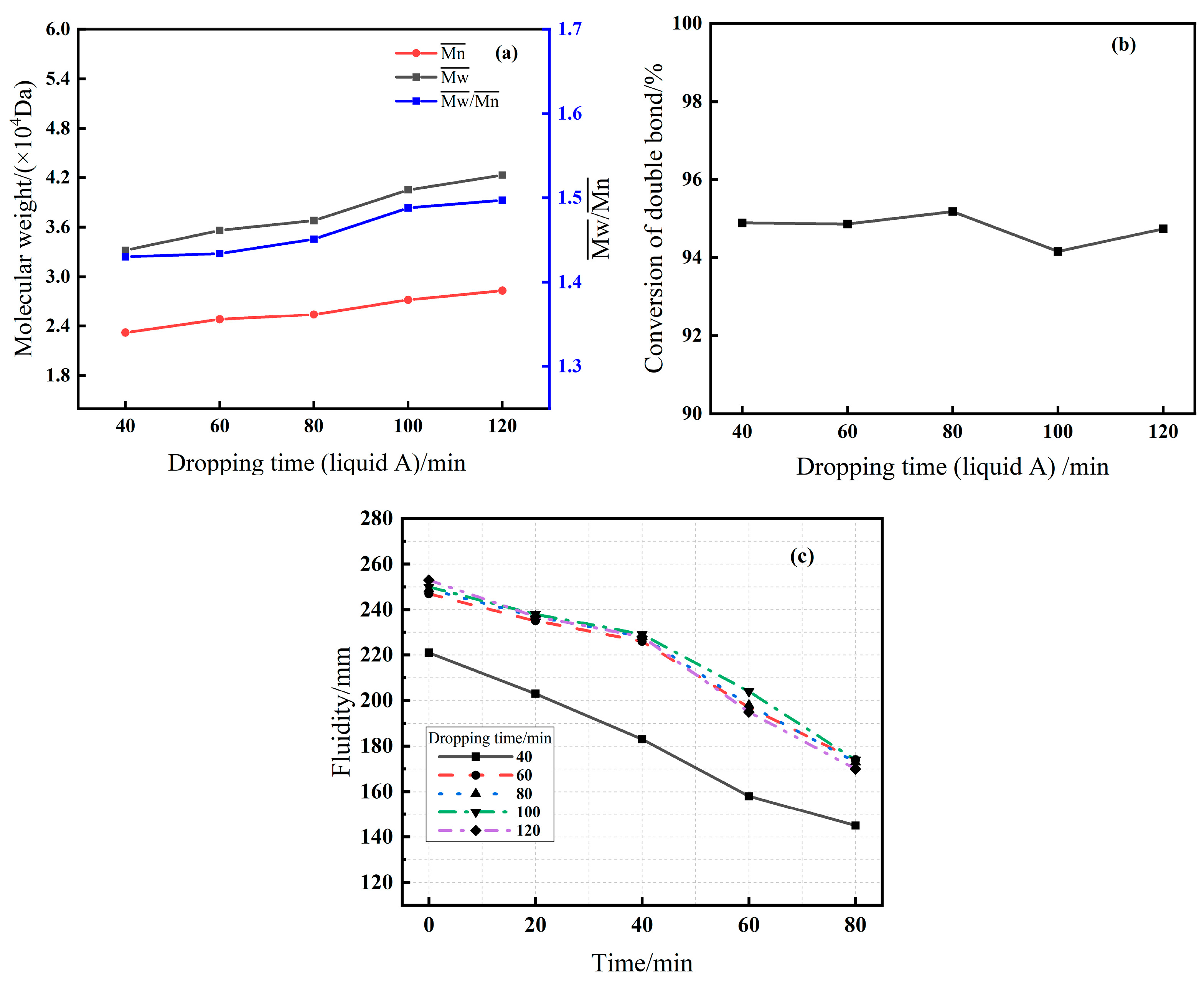

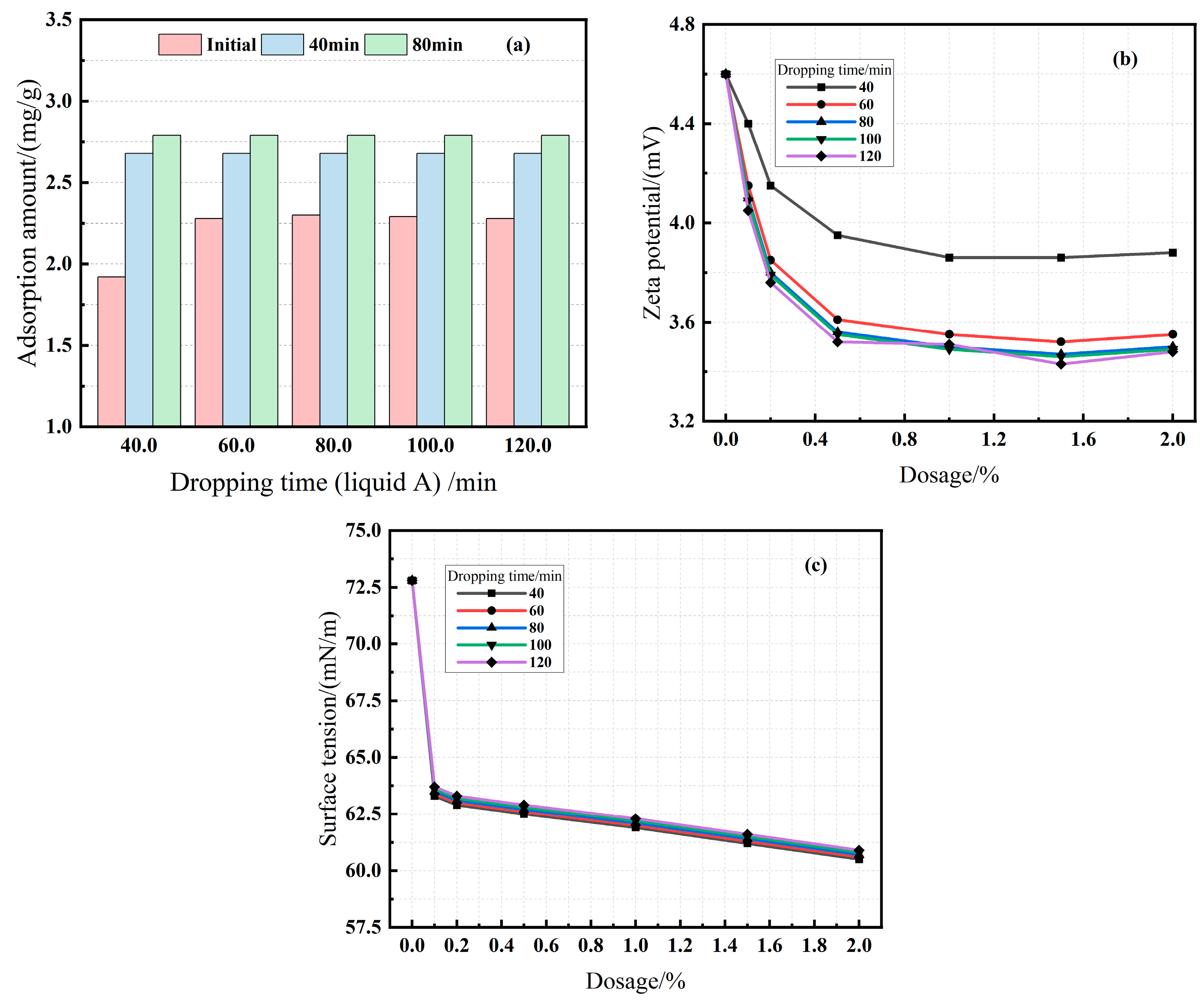

3.2.4. Effect of Dropping Time (Series E)

3.3. Effect of EPEG-PCEs on Cement Hydration and Gel Formation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chomyn, C.; Plank, J. Impact of different synthesis methods on the dispersing effectiveness of isoprenol ether-based zwitterionic and anionic polycarboxylate (PCE) superplasticizers. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 119, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, J.; Sakai, E.; Miao, C.; Yu, C.; Hong, J. Chemical admixtures—Chemistry, applications and their impact on concrete microstructure and durability. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 78, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Shi, W.; Xiang, S.; Yang, X.; Yuan, M.; Zhou, H.; Yu, H.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Z. Synthesis and modification of polycarboxylate superplasticizers—A review. Materials 2024, 17, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Su, J.; Wu, B. A hybrid Bayesian model updating and non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm framework for intelligent mix design of steel fiber reinforced concrete. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 161, 112071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchon, D.; Sulser, U.; Eberhardt, A.; Flatt, R.J. Molecular design of comb-shaped polycarboxylate dispersants for environmentally friendly concrete. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 10719–10728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnefeld, F.; Becker, S.; Pakusch, J.; Götz, T. Effects of the molecular architecture of comb-shaped superplasticizers on their performance in cementitious systems. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2007, 29, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobya, V.; Karakuzu, K.; Mardani, A.; Felekoğlu, B.; Ramyar, K.; Assaad, J.; El-Hassan, H. Compatibility of polycarboxylate ethers with cementitious systems containing fly ash: Effect of molecular weight and structure. Buildings 2025, 15, 3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalas, F.; Pourchet, S.; Nonat, A.; Rinaldi, D.; Sabio, S.; Mosquet, M. Fluidizing efficiency of comb-like superplasticizers: The effect of the anionic function, the side chain length and the grafting degree. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 71, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jarmouzi, R.; Sun, Z.; Yang, H.; Ji, Y. The Synergistic Effect of Water Reducer and Water-Repellent Admixture on the Properties of Cement-Based Material. Buildings 2024, 14, 2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, T.; Ye, J.; Branicio, P.; Zheng, J.; Lange, A.; Plank, J.; Sullivan, M. Adsorbed conformations of PCE superplasticizers in cement pore solution unraveled by molecular dynamics simulations. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Q.; Somasundaran, P.; Miao, C.; Liu, J.; Wu, S.; Shen, J. Effect of the length of the side chains of comb-like copolymer dispersants on dispersion and rheological properties of concentrated cement suspensions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 336, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchikawa, H.; Hanehara, S.; Sawaki, D. The role of steric repulsive force in the dispersion of cement particles in fresh paste prepared with organic admixture. Cem. Concr. Res. 1997, 27, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yan, D.; Lai, H.; Ma, X.; Lai, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, X. Study on rheological, adsorption and hydration properties of cement slurries incorporated with EPEG-based polycarboxylate superplasticizers. Front. Mater. 2024, 11, 1358630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, J.; Li, H.; Ilg, M.; Pickelmann, J.; Eisenreich, W.; Yao, Y.; Wang, Z. A microstructural analysis of isoprenol ether-based polycarboxylates and the impact of structural motifs on the dispersing effectiveness. Cem. Concr. Res. 2016, 84, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, J.; Pöllmann, K.; Zouaoui, N.; Andres, P.; Schaefer, C. Synthesis and performance of methacrylic ester based polycarboxylate superplasticizers possessing hydroxy terminated poly (ethylene glycol) side chains. Cem. Concr. Res. 2008, 38, 1210–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erzengin, S.G.; Kaya, K.; Özkorucuklu, S.P.; Özdemir, V.; Yıldırım, G. The properties of cement systems superplasticized with methacrylic ester-based polycarboxylates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 166, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, B. Effects of polymers on cement hydration and properties of concrete: A review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 2014–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Yao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cui, S.; Liu, X.; Jiang, H.; Guo, Z.; Lai, G.; Xu, Q.; Guan, J. Synthesis, characterization and working mechanism of a novel polycarboxylate superplasticizer for concrete possessing reduced viscosity. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 169, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 8076-2012; Concrete Admixtures. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Abile, R.; Russo, A.; Limone, C.; Montagnaro, F. Impact of the charge density on the behaviour of polycarboxylate ethers as cement dispersants. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 180, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Feng, Z.; Wang, W.; Deng, Z.; Zheng, B. Impact of polycarboxylate superplasticizers (PCEs) with novel molecular structures on fluidity, rheological behavior and adsorption properties of cement mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 292, 123285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odian, G. Principles of Polymerization; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kubisa, P. Kinetics of radical polymerization in ionic liquids. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 133, 109778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, J.; Sachsenhauser, B. Experimental determination of the effective anionic charge density of polycarboxylate superplasticizers in cement pore solution. Cem. Concr. Res. 2009, 39, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-R.; Kong, X.-M.; Lu, Z.-B.; Lu, Z.-C.; Hou, S.-S. Effects of the charge characteristics of polycarboxylate superplasticizers on the adsorption and the retardation in cement pastes. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 67, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, M.; Barron, A.R. Cement hydration inhibition with sucrose, tartaric acid, and lignosulfonate: Analytical and spectroscopic study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 7042–7049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.J.; Biernacki, J.J.; Bullard, J.W.; Bishnoi, S.; Dolado, J.S.; Scherer, G.W.; Luttge, A. Modeling and simulation of cement hydration kinetics and microstructure development. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 1257–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchon, D.; Juilland, P.; Gallucci, E.; Frunz, L.; Flatt, R.J. Molecular and submolecular scale effects of comb-copolymers on tri-calcium silicate reactivity: Toward molecular design. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 100, 817–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Composition wt.% | CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MgO | K2O | SO3 | LOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement | 61.34 | 20.82 | 6.34 | 3.07 | 1.03 | 0.85 | 2.3 | 4.26 |

| Sample ID | Acid-to-Ether Ratio (AA:EPEG) | Temperature (°C) | Initiator Dosage (%) | Chain Transfer Agent (%) | Dropping Time (Sol. A/Sol. B) (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 2:1 | 20 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 60/70 |

| A2 | 3:1 | 20 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 60/70 |

| A3 (B3/C3/D3/E2, Ref) | 4:1 | 20 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 60/70 |

| A4 | 5:1 | 20 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 60/70 |

| A5 | 6:1 | 20 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 60/70 |

| B1 | 4:1 | 0 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 60/70 |

| B2 | 4:1 | 10 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 60/70 |

| B4 | 4:1 | 30 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 60/70 |

| B5 | 4:1 | 40 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 60/70 |

| C1 | 4:1 | 20 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 60/70 |

| C2 | 4:1 | 20 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 60/70 |

| C4 | 4:1 | 20 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 60/70 |

| C5 | 4:1 | 20 | 3.5 | 1.5 | 60/70 |

| D1 | 4:1 | 20 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 60/70 |

| D2 | 4:1 | 20 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 60/70 |

| D4 | 4:1 | 20 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 60/70 |

| D5 | 4:1 | 20 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 60/70 |

| E1 | 4:1 | 20 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 40/50 |

| E3 | 4:1 | 20 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 80/90 |

| E4 | 4:1 | 20 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 100/110 |

| E5 | 4:1 | 20 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 120/130 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, J.; Zou, S.; Yang, H.; Sun, Z. Low-Temperature Synthesis of EPEG-Based Superplasticizers: Kinetic Optimization and Structure–Property Relationships. Buildings 2025, 15, 4551. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244551

Yang J, Zou S, Yang H, Sun Z. Low-Temperature Synthesis of EPEG-Based Superplasticizers: Kinetic Optimization and Structure–Property Relationships. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4551. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244551

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Jingbin, Shuang Zou, Haijing Yang, and Zhenping Sun. 2025. "Low-Temperature Synthesis of EPEG-Based Superplasticizers: Kinetic Optimization and Structure–Property Relationships" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4551. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244551

APA StyleYang, J., Zou, S., Yang, H., & Sun, Z. (2025). Low-Temperature Synthesis of EPEG-Based Superplasticizers: Kinetic Optimization and Structure–Property Relationships. Buildings, 15(24), 4551. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244551