Abstract

The end-of-life phase of a building, which includes demolition and waste disposal, represents a crucial aspect of sustainable construction. In Europe, construction and demolition (C&D) waste accounts for approximately 40% of the total waste generated in the EU, making its management a global challenge. The EU Construction & Demolition Waste Management Protocol (2024) emphasizes the importance of evaluating, before proceeding with the demolition of a building, whether renovation could be a more efficient solution, considering economic, environmental, and technical aspects. From an economic perspective, demolition costs vary depending on several factors, including project size, structural complexity, techniques employed (conventional or non-conventional), materials to be removed, and local regulations. In addition to the direct costs of the intervention, it is essential to consider indirect impacts, such as the management of construction and demolition (C&D) waste, the removal of hazardous substances, and potential environmental damage to be mitigated. This study analyzes a case located in Italy, in the municipality of Caivano (Metropolitan City of Naples, in Campania region), concerning a building that required energy efficiency improvements and seismic upgrades. The decision to demolish and rebuild proved to be economically more advantageous than renovation, while also allowing a 35% increase in volume, enabling the creation of a greater number of housing units. Through the analysis of this real case study, the aim is to highlight how investments in demolition, if properly planned, designed, assessed, and managed, can effectively contribute to building redevelopment, supporting the transition towards a sustainable construction model in line with the principles of the circular economy.

1. Introduction

In the current context of urban planning and the management of the existing building stock, the issue of urban “subtraction”—that is, demolition—is gaining increasing relevance and is often analyzed as the inverse process of construction [1]. It intersects with the challenges of urban regeneration, territorial adaptation, and the circular economy. The act of demolition, traditionally understood as a destructive or residual operation, is now being reinterpreted as a strategic phase in the life cycle of the built environment, aimed at the replacement, adaptation, or reconfiguration of urban space in response to new functional, environmental, and social needs. International literature identifies two main operational strategies in this regard. The first concerns traditional mechanical demolition, in which about 90% of the material is disposed of in landfills and the operation focuses solely on removing the building [2]. The second concerns deconstruction, through which a building is dismantled into its valuable structural components [3]. This practice is more common in Australia, the USA, and Northern Europe, where buildings are predominantly constructed using steel, wood, or prefabricated systems—unlike in Italy, where most buildings are made of masonry and reinforced concrete.

In this context, the international and national regulatory framework governing the service life of buildings and the management of end-of-life phases plays an increasingly significant role. At the international level, the ISO 15686 series (“Service Life Planning”) [4]. defines methodologies for predicting durability and planned maintenance, while ISO 20887 [5] introduces criteria for design for deconstruction and reuse of building components, in line with circular economy principles. At the European level, the Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC) mandates a 70% recycling rate for non-hazardous construction and demolition waste (CDW) and establishes objectives for prevention, reuse, and recovery [6]. The “Construction and Demolition Waste Protocol” strengthens these requirements by providing operational guidelines for pre-demolition audits, on-site material separation, traceability, and improved recycling rates [7]. In parallel, Regulation (EU) 2020/852 (EU Taxonomy) defines technical criteria for classifying a construction project as sustainable, requiring selective demolition, high material recovery rates, and controlled CDW management [8].

The relevance of these issues is further underscored by European data: the construction sector is responsible for 39% of global CO2 emissions and 35% of total landfill waste [9], while CDW accounts for roughly 40% of all waste generated in the European Union, with projections indicating substantial growth by 2050 [10]. In this context, improving the circularity of construction materials is considered essential for the transition toward more sustainable models. In Italy, these principles are reflected in several regulatory instruments: Legislative Decree 152/2006 (“Environmental Code”) [11], which transposes Directive 2008/98/EC, promotes selective demolition as a means to enhance material separation and recovery; the Minimum Environmental Criteria for buildings (CAM Edilizia 2022, Ministerial Decree 256/2022) make demolition planning based on recycling logic mandatory in public procurement and require the use of Life Cycle Assessment methodologies [12]. Furthermore, Ministerial Decree 127/2024 (“End of Waste”) establishes criteria for the end-of-waste status of recycled aggregates, expanding their potential use in construction works [13].

The European Circular Economy Action Plan [14], part of the Green Deal, also identifies the construction and demolition sector as a priority for reducing waste and improving resource efficiency, promoting more advanced recovery chains, mandatory audits, and quality standards for recycled materials.

The need for the regeneration of the existing building stock in Europe—and particularly in Italy—is becoming increasingly urgent. As highlighted by the Buildings Performance Institute Europe, a substantial portion of the European real estate stock consists of buildings constructed more than 50 years ago, while in Italy, the majority of buildings date back to before the 1970s [15]. The national building stock is largely composed of masonry or reinforced concrete structures built in periods when seismic design standards and energy efficiency requirements were not yet in place, resulting in significant issues in terms of safety, energy performance, and overall sustainability [16]. The issue of demolition therefore assumes particular significance, as it should not be regarded merely as an “enabling” operation for the transformation or regeneration of land—hence as a cost to be incurred and included in the estimation of the future construction project—but rather in relation to other crucial appraisal and evaluative aspects that affect the efficiency and sustainability of the intervention. These include:

- (i)

- the demolishing action, understood as the final stage in the life cycle of the built environment and thus capable of generating residual value when considering the recoverable worth of certain building components;

- (ii)

- the higher market value associated with the reconstruction of a building, compared to conservative interventions, proportional to both the formal and technological enhancement of the structure and the improvement of its energy performance;

- (iii)

- the reactivation of urban land rents previously “inhibited” by low-quality building fabrics, particularly in light of the increasing use by policymakers of measures related to the so-called “density bonus,” more commonly referred to as “building incentives” [17];

- (iv)

- the environmental impact of demolition itself, due to material disposal, which can be assessed in terms of the building product’s overall “footprint” through Life Cycle Assessment methodologies.

In light of these premises, this paper aims to analyze and evaluate, among the economic–appraisal and environmental aspects of demolition, the relationship between costs and sustainability. The objective is to explore how demolition and reconstruction, as opposed to simple refurbishment, can represent a design strategy that is advantageous not only from an economic standpoint but also in terms of energy performance, reduction in environmental impact, and enhancement of the building stock. Demolition, therefore, should not be seen merely as a technical alternative to building renovation but rather as a conscious and strategic design choice, grounded in a careful assessment of the economic, environmental, and structural factors that characterize the entire life cycle of a building.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Methodology

The research framework adopted in this study is articulated through a four-stage methodological pathway, allowing for a systematic analysis of demolition as a sustainable design choice. In the first phase, an in-depth review of the scientific literature and the international, European, and national regulatory framework was conducted, with particular attention to standards on building service life, policies for the management of construction and demolition waste (CDW), circular economy strategies, and regulations governing selective demolition and reconstruction (ISO 15686, ISO 20887, Directive 2008/98/EC, EU Taxonomy, CAM Edilizia, DM 127/2024). The second phase focused on examining appraisal aspects related to the end-of-life stage, analyzing demolition costs, waste disposal, material recovery, site preparation, and reconstruction. This phase also assessed the economic effects of building replacement, considering the residual value of the structure, the variation in market value after the intervention, and market differentials between new, regenerated, and existing buildings, as outlined in recent sector studies. The third phase was dedicated to analyzing the Caivano case study, through the collection of technical, operational, and economic data relating to the demolition and reconstruction project. Operational phases, employed techniques, specific costs (amounting to €455,000), the percentage incidence of each category of work, and the design motivations supporting demolition as the most effective solution compared to refurbishment were examined in detail. Finally, in the fourth phase, the results were discussed and compared with theoretical and regulatory evidence, in order to draw conclusions on the economic, environmental, and performance sustainability of demolition–reconstruction and to formulate recommendations useful for future urban regeneration initiatives.

2.2. Demolitions and Appraisal Aspects

The end-of-life phase of a building represents a critical stage in the life cycle of the built environment, as it involves significant economic, environmental, and technical decisions. Within this phase, demolition activities play a key role, constituting—within the perspective of territorial economics and planning—one of the main components of idoneizzazione (site preparation) costs [18]. As is well known, in the classical concept of settlement production, idoneizzazione costs refer to all preliminary activities required to make a site suitable to host a new development or future function. These generally include “demolition costs” of existing structures, estimated according to the extent and typology of the buildings to be demolished, and “remediation costs.”

Particularly today, in urban centers—often affected and transformed by development dynamics—and in peripheral areas, frequently characterized by disused industrial sites, unfinished buildings, or abandoned properties, the issue of making the existing building stock suitable for reuse has re-emerged. This process entails re-idoneizzazione costs, which are complex to assess and difficult to generalize. One may consider, for instance, the estimation of remediation costs [19]: several stages must be taken into account for such an evaluation (including site characterization plans, field and laboratory investigations, risk analysis, remediation design, and execution), as well as multiple variables that come into play, such as the quantity of material to be treated and the nature and concentration of contaminants to be removed.

With regard to demolition and its associated costs, it is first important to note that the demolition process generally consists of three main phases: pre-design, design, and operational. The pre-design phase involves data collection and analysis of the existing condition of the building and its context through surveys, audits, and structural assessments, with the aim of identifying constraints, interferences, and potential critical issues.

The design phase focuses on identifying and evaluating the most appropriate demolition techniques, taking into account factors such as safety, structural stability, scheduling, and intervention costs, as well as environmental and acoustic impacts. Finally, the operational phase concerns the implementation of the executive procedures, including the actual demolition, the management of materials and waste, remediation operations, and the preparation of the site for subsequent construction phases [20].

Among the most significant aspects of demolition processes is the assessment of costs, which must be preceded by an accurate analysis of the residual value of the building. This evaluation takes into account variables such as size, geographical location, state of conservation, construction materials, and the intrinsic value of the structure—all elements that directly affect operational complexity and, consequently, the economic estimation of the intervention. The preliminary cost assessment constitutes the starting point of any demolition project and requires the collection of essential technical and contextual data, including the type and size of the building, the materials used, site accessibility conditions, and structural stability. Various methodological approaches can be adopted for cost estimation, including unit-based estimates (e.g., per square meter or cubic meter of material removed), time- and labor-based estimates, complexity-based evaluations, and comparative estimates derived from previous contracts.

To support these methods, the use of automated estimation software enables the development of more accurate forecasts by integrating economic, technical, and regulatory parameters. A thorough cost analysis must also account for additional complexity factors such as the presence of hazardous materials (e.g., asbestos), the need for environmental remediation and site preparation, as well as the impact of environmental and safety regulations. These factors can significantly influence both operational procedures and the overall cost of the intervention. Finally, the variability of demolition costs is strongly influenced by external factors such as geographical location, the availability of specialized contractors, the demolition technique employed, and local regulatory requirements. An integrated understanding of these factors is therefore essential to develop reliable economic estimates and to plan demolition strategies that are sustainable and optimized from both technical and financial perspectives [21,22].

From an appraisal perspective—prior even to the evaluative stage—the choice between demolition and conservative intervention has a significant impact on the market value of a building once it has been reconstructed or transformed. Recently, in Italy, several studies have examined the differences in market values between newly built, renovated, and existing properties. According to the Rapporto sull’Abitare 2024 published by Scenari Immobiliari, the price gap between new and used properties in major Italian cities ranges between 30% and 40%. Moreover, Scenari Immobiliari has introduced into its Real Value database data concerning real estate development projects (including both new constructions and conservative regenerations), from which a difference in market value between “new” and “regenerated” properties can be observed, ranging from 10% to 20%.

This differential directly affects the choice of intervention, particularly if one considers—as already highlighted in the seminal studies of C. Forte [18], still highly relevant today—the relationship between urban renewal policies (in this case referring to the selective choice between demolition and reconstruction or other categories of building intervention) and the economic pattern of urban land values.

In this perspective, the paper aims to analyze, through the presentation of a case study concerning a building intervention in Caivano, within the Metropolitan City of Naples, the role of demolition as a sustainable design choice, demonstrating how, under certain conditions, it can prove more advantageous than the renovation or refurbishment of the existing building.

2.3. The Case Study

The case under analysis concerns a complex building project carried out in the Municipality of Caivano, located within the Metropolitan City of Naples, in the Campania Region. Caivano is a particularly degraded municipality in the Neapolitan hinterland which, since 2023, has been placed under government receivership and subjected to an Extraordinary Plan of Infrastructural and Functional Redevelopment Interventions aimed at territorial regeneration [23]. Within this broader urban regeneration framework lies the existing building that is the focus of the present study.

In particular, the assessment of demolition timeframes and costs represented a crucial step in determining the most appropriate intervention strategy when compared to a potential refurbishment of the existing structure. Specifically, the project involves the demolition and reconstruction of a residential building under the measures provided by the Superbonus 110%, introduced by the Relaunch Decree (Decreto-Law No. 34/2020) [24]. This fiscal incentive granted a 110% tax deduction on expenses incurred for specific energy efficiency and seismic improvement interventions, with the goal of promoting the sustainable redevelopment of the existing building stock, reducing pollutant emissions, and revitalizing the construction sector [25].

However, the sperimentation does not take into account the tax benefits deriving from the aforementioned 110% Superbonus measure; instead, it includes the benefits deriving from building incentives that fall within the concept of the so-called “density bonus”. In fact, the decision to proceed with the complete demolition of the existing building rather than opting for renovation was motivated by two main factors. First, the opportunity to benefit from the 35% volumetric increase allowed under the “Piano Casa”, a regional regulation aimed at revitalizing the construction industry and promoting the upgrading of the existing real estate stock while addressing housing needs. This measure permits, within specific limits and in compliance with urban planning, environmental, and landscape regulations, a volume increase of up to 35% in the case of demolition and reconstruction, thereby encouraging more efficient land use and an increase in available housing units [26].

Second, the greater economic and performance advantages associated with a new construction, capable of ensuring compliance with current seismic regulations (seismic zone S9) and achieving significantly higher energy performance standards compared to a mere refurbishment of the existing building.

The demolition operations were carefully planned and structured in multiple phases, calibrated to the building’s structural conditions and urban context. The process began with the manual removal of interior flooring, partition walls, and existing installations. Subsequently, a perimeter safety scaffolding was installed, and the upper floors were demolished using low-vibration tools (such as saws and pneumatic hammers) to minimize noise and vibration impacts. The lower portions of the building were removed using mechanical equipment, except for the masonry wall adjacent to the neighboring structure, which was dismantled manually to prevent structural damage to adjoining properties.

The new project involved the construction of a multi-level building, comprising a semi-basement housing technical rooms and storage spaces, and five above-ground floors designated for residential use. Additionally, the design included a communal staircase core with a double-access elevator and an equipped courtyard area featuring non-slip and permeable pavements, rainwater drainage systems, and outdoor lighting installations.

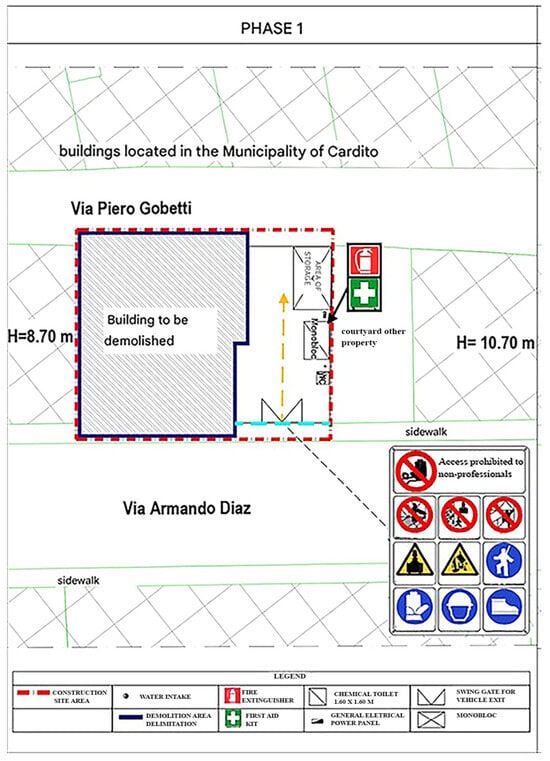

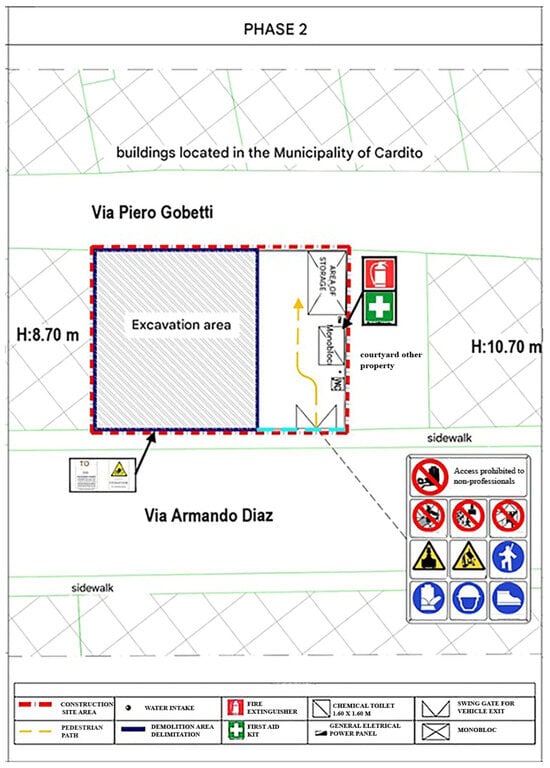

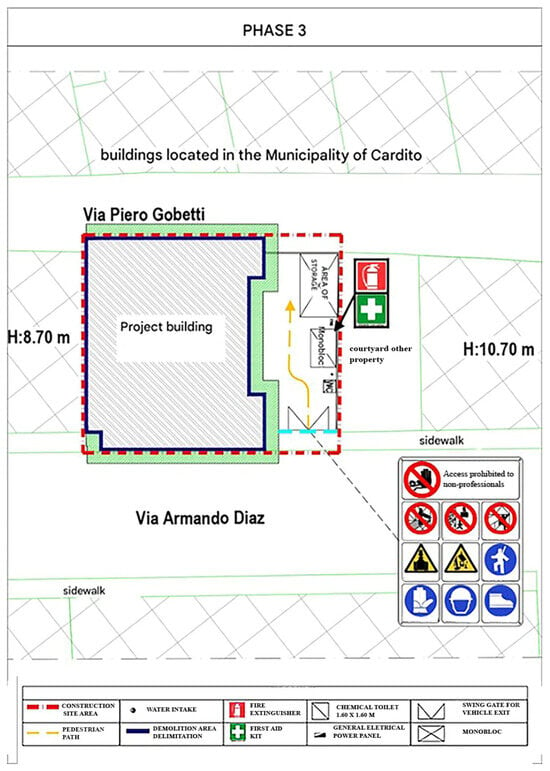

On the flat roof, a photovoltaic system was installed to supply electricity to the entire building, thereby contributing to the reduction of overall energy consumption and enhancing the project’s environmental sustainability. From Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3, the three phases of the project implementation can be observed.

Figure 1.

Plan of the first construction phase.

Figure 2.

Plan of the second construction phase.

Figure 3.

Plan of the third construction phase.

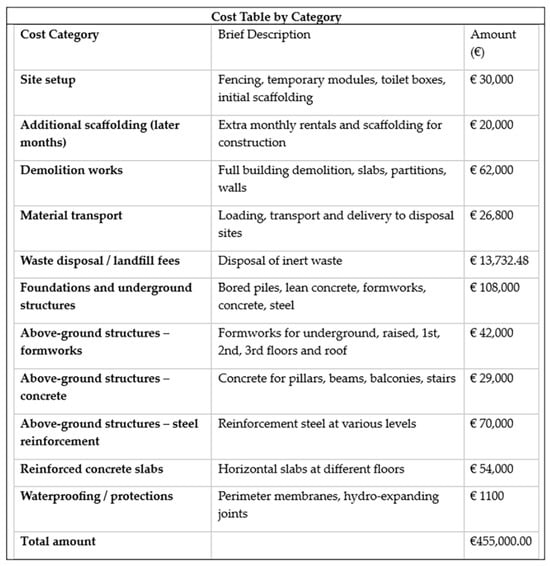

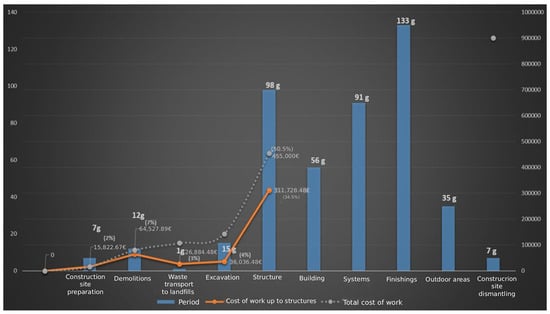

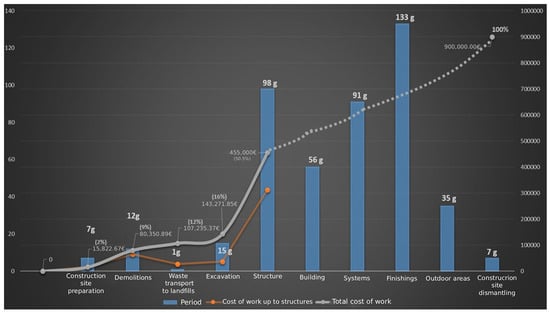

Based on estimates made, followed by careful checks, the total cost of the works amounted to €900,000, of which €455,000 (approximately 50.5%) was attributable solely to the demolition and reconstruction phases (Figure 4). In addition to meeting safety and sustainability requirements, the project represents a significant example of how planned demolition can serve as a strategic lever for urban regeneration and the optimization of the existing building stock.

Figure 4.

Demolition and reconstruction costs.

3. Results

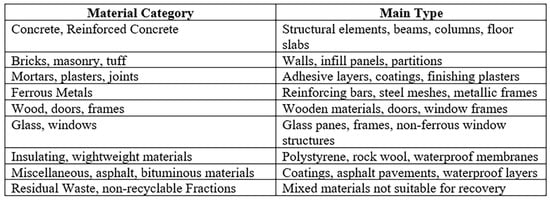

The economic analysis of the demolition and reconstruction of the residential building under study made it possible to highlight the distribution and impact of the main cost items, enabling an integrated assessment of the project’s operational and structural components. A classification of the main construction materials considered in the analysis is reported in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Main categories and types of materials used in the building.

The cost of the demolition and reconstruction works, amounting to €455,000, was broken down into several functional categories. Among these, the superstructure accounts for the largest share, representing 61.7% of the total, followed by demolition and waste disposal at 16.6%, foundation works at 9.5%, and expenses related to scaffolding and site setup at approximately 7%. This distribution is consistent with the average parameters observed in comparable demolition and reconstruction projects in urban contexts, where structural operations absorb the majority of financial resources, while demolition costs—though significant—remain contained within percentage values below 20% of the total.

The average unit cost of demolition, including disassembly, transport, and material disposal phases, was approximately €32/m3. This figure aligns with the reference values reported in technical literature for projects in high-density urban areas, which generally range between €25 and €45/m3, depending on operational complexity and distance from treatment facilities.

The following graphs illustrate (Figure 6 and Figure 7), according to the various phases of the demolition and construction process, the total project cost of €900,000 and the costs associated with each operational phase, amounting to a total of €455,000—equivalent to 50.5% of the overall expenditure.

Figure 6.

Graph Showing the Final Stage of Work Progress.

Figure 7.

Graph depicting the contract value of the works.

From a management perspective, the demolition phase represents a critical stage not only in economic terms but also from an environmental standpoint, as it involves the separation, recovery, and controlled disposal of construction and demolition waste (CDW). Compliance with these requirements helps to reduce environmental impact and optimize the flow of recoverable materials, thereby contributing to the overall sustainability of the project. The cost analysis thus confirms that careful planning of the demolition and reconstruction phases constitutes a fundamental tool for ensuring a balance between technical efficiency, environmental sustainability, and economic feasibility throughout the building’s life cycle. The operations began with the manual demolition of the slabs and walls of the uppermost floor, followed by the successive lower levels. The use of mixed manual and mechanical equipment (such as electric hammers, trucks, chutes, and telescopic props), together with the adoption of advanced safety measures (including wall wetting to minimize dust, restricted site access, and independent service platforms), influenced the overall costs of demolition and waste disposal.

The demolition phase required meticulous management of risks and potential interferences with the urban surroundings, with particular attention to adjacent structures and the residual stability of the building, monitored through shoring systems and movement indicators. Waste disposal activities involved the controlled transport of debris and the separation of recoverable fractions, in compliance with Ministerial Decree No. 127/2024 “End of Waste” and the Minimum Environmental Criteria for Construction (CAM Edilizia 2022) [12].

The analysis of the results provides several operational indications that can guide similar interventions. The breakdown of costs highlights the importance of accurate planning of the demolition phase, as it significantly affects the overall economic balance of the project. The case study also confirms that selective demolition and careful management of Construction & Demolition Waste (CDW) can reduce disposal costs and increase material recovery. Finally, the comparison between refurbishment and demolition–reconstruction shows that, in the presence of significant structural and energy deficiencies, building replacement represents a more efficient and sustainable solution over the entire life cycle.

From a management standpoint, demolition costs represent a strategic component not only from an economic perspective but also from an environmental one, as they directly affect the potential for the reuse and recycling of construction and demolition waste (CDW). In the present case, the combination of controlled demolition, partial material reuse, and high-performance structural reconstruction made it possible to contain costs while ensuring compliance with current regulations on safety, efficiency, and sustainability. The assessment of energy performance, carried out during both the design and implementation phases, confirmed consistency with the efficiency and sustainability requirements established by current legislation. The intervention complies with national regulations on energy consumption reduction, as set forth in Legislative Decrees No. 192/2005 and No. 311/2006, as well as Law No. 10/1991, and meets the obligations concerning the integration of renewable energy sources pursuant to Article 11 of Legislative Decree No. 28/2011.

4. Discussion

In the contemporary construction sector, there is a growing and urgent need to limit land consumption and regenerate the existing building stock, which is responsible for approximately 36% of global greenhouse gas emissions [27]. Building retrofitting represents a complex and multidimensional process that encompasses not only energy and structural aspects but also environmental, landscape, and architectural dimensions [28]. However, while the principles of the European ecological transition promote the extension of the life cycle of existing buildings, in the case of outdated, deteriorated, or non-compliant structures—particularly with regard to seismic and energy regulations—demolition and reconstruction may constitute a more sustainable strategy than deep refurbishment.

In light of the findings emerging from the scientific literature and the Caivano case study, the choice between restoration and demolition must be addressed through an integrated approach capable of simultaneously considering economic costs, environmental impacts, and long-term performance. Numerous international studies demonstrate that, within a building’s life cycle, the operational phase (use and energy consumption) accounts for the majority of total environmental impacts [29]. From this perspective, newly constructed buildings—realized using high-efficiency technologies and recycled materials—are able to offset the initial impacts associated with construction and demolition phases, while ensuring enhanced energy performance and greater durability.

Although structural and energy-efficiency improvements can extend the service life of existing buildings, they cannot achieve the overall durability of new constructions. At the same time, newly built structures are designed according to updated performance standards, employing high-strength, low-impact materials and advanced construction systems that ensure lower maintenance costs and higher efficiency throughout the entire life cycle. In this context, several studies have shown that construction and demolition waste can be effectively reused as recycled aggregates for concrete or as secondary building components, providing mechanical and functional performance equivalent to that of traditional materials, and significantly contributing to reducing the ecological footprint of the construction sector.

The demolition and reconstruction project in Caivano represents a concrete example of sustainable building regeneration, in which the design decision was guided by an integrated evaluation demonstrating that the complete demolition of the pre-existing structure was economically and technically more advantageous than refurbishment. This approach enabled the creation of an energy-efficient, seismically safe building consistent with the principles of the circular economy. Therefore, it emerges that consciously planned and managed demolition can serve as a strategic lever for ecological transition and sustainable urban regeneration, fully aligned with European objectives for decarbonization and the promotion of a circular economy within the construction sector.

5. Conclusions

Interventions on the existing building stock require careful consideration of the appropriate category of building intervention to be implemented (extraordinary maintenance or full-scale building renovation). This choice depends not only on cost factors but also on potential variations in market value that such a decision may generate, particularly where urban planning conditions and market dynamics allow for land valorization and sustainable densification [30,31]. The positive effects of this choice are more pronounced in metropolitan contexts or in areas characterized by active real estate markets, whereas they are more limited in smaller or low-demand residential areas. In the case of Caivano, the project demonstrated how the combination of regulatory incentives (such as the “Superbonus 110%” and the “Piano Casa”) [24,26] and strategic planning can produce significant effects in terms of urban regeneration and increased property value. This was achieved through the overall increase in building volume and the improvement of both energy and seismic performance, contributing to the mitigation of building decay and functional obsolescence.

Further analysis may include a more detailed assessment approach increasing the number of variables taken into consideration (cleanup costs, energy efficiency, seismic performance) which may significantly affect market value [17]. Even more, the assessment of the type of action of buildings that have been abandoned for a long time can be considered for further improvements; this case presents multiple options (which depend on the level and type of deterioration of the abandoned building, as well as any conservation restrictions) on which the financing of the initiative depends and which therefore require further improvements of the research topic addressed in this work.

From an environmental standpoint, the research highlights that the end-of-life phase of a building—including demolition, material management, and recovery—represents a crucial stage for the overall assessment of sustainability throughout the building life cycle. In this regard, the application of the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methodology could prove essential for integrating environmental evaluation with economic assessment throughout the entire process, from demolition to reconstruction. This methodology, which currently constitutes one of the most widely adopted tools for evaluating environmental impacts in the construction sector, enables the objective quantification of all resources used and emissions generated over a building’s entire life cycle—from the extraction of raw materials to its end of life. By analyzing input flows (raw materials, energy, water) and output flows (emissions, waste, effluents), LCA provides a comprehensive measure of the sustainability of building products, processes, and services [29].

Although, according to the scientific literature, the end-of-life phase does not represent the stage with the highest environmental impact over the entire life cycle—impacts that are often more significant during the production of materials and the use phase of the building—the end-of-life stage, which includes demolition, waste management and material recovery, nonetheless plays a strategic role in shaping the overall environmental footprint of the construction sector. It is in fact the moment when material circularity can be maximized and the environmental burdens associated with disposal can be reduced. This allows for an objective quantification of the impacts related to the management of Construction & Demolition Waste (CDW) and supports the identification of solutions capable of reducing emissions, improving material recovery, and optimizing the financial resources employed [32]. In addition to the economic and environmental aspects, the construction of a new building also generates significant social benefits, as a replacement intervention makes it possible to improve the quality of living through safer, more comfortable, and more accessible spaces, equipped with higher energy performance and compliant with seismic safety standards. Moreover, in areas affected by degradation or marginalization, such as the case of Caivano, such transformations represent an opportunity to rebuild social capital, enhance livability, and promote greater equity in access to housing.

In conclusion, the results confirm that consciously planned demolition, when supported by integrated analytical tools such as LCA, can serve as an effective lever for sustainable urban regeneration, contributing both to the economic enhancement of the built heritage and to the reduction in environmental impacts associated with end-of-life management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M., F.B., C.C., F.F. and G.F.; methodology, D.M., F.B., C.C., F.F. and G.F.; validation, D.M., F.B., C.C., F.F. and G.F.; formal analysis D.M., F.B., C.C., F.F. and G.F.; resources, D.M., F.B., C.C., F.F. and G.F.; data curation, D.M., F.B., C.C., F.F. and G.F.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M., F.B., C.C., F.F. and G.F.; visualization, D.M., F.B., C.C., F.F. and G.F.; supervision, D.M., F.B. and F.F.; project administration, D.M., F.B. and F.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rusci, S.; Perrone, M.A. The City to Be Demolished: A Case Study for the Analysis of Demolition and Urban Contraction Costs in Italy. Valori Valutazioni 2020, 26, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahir, S.Z.; Syal, M.G.M.; Lamore, R.; Berghorn, G. Approaches and Associated Costs for the Removal of Abandoned Buildings. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 31 May–2 June 2016; pp. 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lyle, B.; Langston, C. Estimating Demolition Costs for Single Residential Buildings. Aust. J. Constr. Econ. Build. 2012, 3, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 15686; Buildings and Constructed Assets: Service Life Planning. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- ISO 20887; Sustainability in Buildings and Civil Engineering Works: Design for Disassembly and Adaptability—Principles, Requirements and Guidance. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Directive 2008/98/EC; Waste and Repealing Certain Directives. European Parliament and Council of the European Union: Strasbourg, France, 2008.

- European Commission. EU Construction and Demolition Waste Management Protocol; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation (EU) 2020/852; On the Establishment of a Framework to Facilitate Sustainable Investment, and Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 (EU Taxonomy). European Parliament and Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Damgaard, A.; Lodato, C.; Butera, S.; Fruergaard, T.A.; Kamps, M.; Corbin, L.; Tonini, D.; Astrup, T.F. Background Data Collection and Life Cycle Assessment for Construction and Demolition Waste (CDW) Management; European Environment Agency (EEA): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Construction & Demolition Waste Management Protocol: Including Guidelines for Pre-Demolition and Pre-Renovation Audits of Construction Works, Updated Edition; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. Norme in Materia Ambientale (Codice dell’Ambiente); Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. Adozione dei Criteri Ambientali Minimi per l’Affidamento del Servizio di Progettazione e Lavori per gli Interventi Edilizi (CAM Edilizia 2022); Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. Regolamento Recante la Disciplina Della Cessazione Della Qualifica di Rifiuto (End of Waste) dei Rifiuti Inerti da Costruzione e Demolizione e di Altri Rifiuti Inerti di Origine Minerale; Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Circular Economy Action Plan: For a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Building Performance Institute Europe (BPIE). Europe’s Buildings Under the Microscope; BPIE: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. Available online: http://bpie.eu/publication/europes-buildings-under-the-microscope/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT). 15° Censimento Generale Della Popolazione e Delle Abitazioni; ISTAT: Rome, Italy, 2011. Available online: https://www.istat.it/statistiche-per-temi/censimenti/censimenti-storici/popolazione-e-abitazioni/popolazione-2011/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Battisti, F.; Campo, O. The Assessment of Density Bonus in Building Renovation Interventions. The Case of the City of Florence in Italy. Land 2021, 10, 1391, Correction in Land 2022, 11, 1778. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, C. Elementi di Estimo Urbano; Etas Kompass: Milano, Italy, 1968; p. 233. [Google Scholar]

- Rosasco, P.; Sdino, L.; Magoni, S. Reclamation Costs and Their Weight in the Economic Sustainability of a Project. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 223, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordà, N. Demolizioni Civili e Industriali: Tecniche, Statica, Rischi Specifici e Interferenti, Misure, Piano di Manutenzione, Gestione Rifiuti; EPC Libri: Milano, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, C.; De Rossi, B. Principi di Economia ed Estimo; Etas Kompass: Milano, Italy, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, P.; Donnarumma, G.; Sicignano, C. Refurbishment vs. Demolition and Reconstruction: Analysis and Evaluation in Order to Choose the Intervention. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Building Renovation and Regeneration, Fisciano, Italy, 3–8 September 2017; University of Salerno: Fisciano, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. Decreto-Legge 15 Settembre 2023, n. 123, Convertito, con Modificazioni, Dalla Legge 13 Novembre 2023, n. 159; Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. Misure Urgenti in Materia di Salute, Sostegno al Lavoro e all’Economia, Nonché di Politiche Sociali Connesse all’Emergenza Epidemiologica da COVID-19 (Decreto Rilancio); Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gotta, A. Riqualificazione di un Complesso Anni ’60 a Sampeyre come Nuovo Modello di Residenza—Study of Superbonus 110%. Master’s Thesis, Politecnico di Torino, Torino, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bollettino Ufficiale della Regione Campania. Misure Urgenti per il Rilancio Economico, per la Riqualificazione del Patrimonio Edilizio Esistente, per la Prevenzione del Rischio Sismico e per la Semplificazione Amministrativa (Piano Casa Campania); Bollettino Ufficiale della Regione Campania: Napoli, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Resource Efficiency and Climate Change; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoli, C.; Dragonetti, L.; Ferrante, A. Renovation or Demolition and Reconstruction? Analysis of Design Scenarios Developed According to a Circular Approach; University of Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mesa, J.A.; Fúquene-Retamoso, C.; Maury-Ramírez, A. Life Cycle Assessment on Construction and Demolition Waste: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, F.; De Paola, P. The “Future” of Urban Rent from the Perspective of the Metropolitan Territorial Plan of Naples. Valori Valutazioni 2020, 27, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangialardo, A.; Micelli, E. Reconstruction or Reuse? How Real Estate Values and Planning Choices Impact Urban Redevelopment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iodice, S.; Garbarino, E.; Cerreta, M.; Tonini, D. Sustainability assessment of Construction and Demolition Waste management applied to an Italian case. Waste Manag. 2021, 128, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).