Abstract

Achieving reliable interoperability between architectural and structural models remains one of the main challenges in BIM-based design workflows. Despite the widespread adoption of Building Information Modeling, the automatic transfer of information between modeling software and FEM analysis tools continues to generate inconsistencies, information loss, and the need for manual interventions. This study examines these issues through the case study of a reinforced-concrete residential building located in Palermo, used to evaluate BIM-to-FEM exchanges between Revit®, Robot Structural Analysis®, PRO_SAP®, and JASP®. The interoperability tests highlight significant limitations in both native and IFC-based workflows. The direct Revit–Robot link ensures good geometric consistency but still requires manual correction of analytical axes, connections, and boundary conditions. Indirect transfers via IFC exhibit greater instability: both IFC2x3 Coordination View 2.0 and IFC4 Reference View show difficulties in correctly interpreting structural elements and do not adequately preserve analytical relationships, resulting in unconnected slabs, disconnected nodes, and missing constraint information. In PRO_SAP®, several elements are also absent after IFC import. To address these issues, the study proposes a workflow based on the integration of Revit® and JASP® aimed at generating a reliable federated model. This model was further validated in Navisworks®, Solibri Anywhere®, BIM Vision®, and Enscape® to assess its correct interpretation across different software environments. This approach enhances interdisciplinary coordination, supports clash detection, facilitates immersive VR-based review, and centralizes architectural, structural, and MEP models into a unified environment. The results show that structured workflows and careful management of native and IFC transfers significantly improve model reliability and reduce design inconsistencies.

1. Introduction

Building Information Modeling (BIM) represents an ever-evolving approach that integrates design, construction, and management processes throughout the lifecycle of a project, creating a digital prototype that centralizes project information. Building Information Modeling (BIM) enhances stakeholder communication, mitigates conflicts, and reduces rework throughout the project lifecycle [1,2,3,4]. This methodology is highly adaptable to other design disciplines, such as architecture and complementary projects. Furthermore, BIM proves to be essential in facilitating the lifecycle management of engineering structures [1,2], while simultaneously enabling the implementation of sustainability and circular economy principles through more accessible and available resource tracking, efficient material management, waste reduction through precise planning and optimized decision-making processes [5,6]. Recent research highlights the importance of structured data models for material documentation and their integration with BIM environments, demonstrating how database and web-based approaches can reduce design errors and improve interoperability between architectural and technical information sources [7].

2. State of the Art

According to a McGraw Hill Construction report [8], the use of BIM presents a very low value/difficulty ratio for engineering analyses. For structural analysis, this ratio turns negative, often prompting engineers to create models from scratch rather than reuse architectural BIM models.

Studies such as those by Muller et al. [9] demonstrate the advantages of the BIM workflow over traditional CAD, reducing errors and increasing efficiency through the use of centralized repositories. Similarly, Sampaio et al. [10] emphasize the benefits of BIM in supporting multidisciplinary collaboration in structural design, while pointing out persistent issues of interoperability between authoring and analysis software. At the same time, research by Borrmann et al. [11] and Sibenik et al. [12] highlight challenges in interoperability, despite the advances made in the IFC and MVD (Model View Definitions) standards. The buildingSMART® International organization plays a crucial role in the development of standards for digital sharing, although limitations in standardization and data loss persist. The evolution of the IFC standard, driven by buildingSMART®, has brought significant improvements to BIM workflows, such as the integration of advanced dimensions (4D, 5D), GIS interoperability, and infrastructure simulations. The IFC4.3 version extends the schema to infrastructure domains, while IFC4.4 aims to support new functionalities for tunnels. MVDs, subsets of the IFC schema, optimize data exchange between software, enhancing standardization and interoperability. However, their implementation, related to the IFC2x3 and IFC4 versions, presents challenges such as high certification costs and a lack of consistency in software support.

Improving data exchange efficiency in BIM requires the development of standardized guidelines and software tools that promote the use of appropriate MVDs, fostering more consistent workflows. Aldegeily and Zhang [13] identify three data exchange modes in BIM–structural analysis workflows: direct links through native files or APIs and indirect links using independent formats such as IFC. These categories highlight the dynamics between software providers, whether unique, interoperable, or third party, contributing to the limited interoperability of MVDs. The efficiency of data exchange between architectural and structural BIM models is influenced by the correct implementation of the IFC and MVD standards. Sibenik and Kovacic [12] propose an extended concept of “data transmission flow,” which includes inter-organizational factors such as standardization and certification, essential for optimizing information flow and coordination between design and organizational levels.

Muller et al. [9] analyzed BIM-to-BIM and BIM-to-FEM interoperability (2011–2016), highlighting advances in the transfer of geometries, grids, and positioning through the IFC format, but showing limitations in the transmission of materials. Lai and Deng [14] reported in 2018 significant differences between IFC files in terms of size, entities, and properties, particularly after the export–import cycle between different software. The main issues emerge in IFC classification and the consistency of transferred data, indicating the need for improvements in interoperability between platforms.

Ren et al. [15] evaluated BIM-to-FEM data exchange for steel elements in 2018, using models created in Revit® 2018 and exported to IFC. During import into Robot Structural Analysis®, ETABS®, and SAP2000®, issues related to materials, loads, and boundary conditions arose, requiring accurate property mapping. Aldegeily and Zhang [13] analyzed three BIM-to-FEM interoperability modes: direct links via native files or APIs and indirect links using IFC, noting information loss on material properties and model instability despite the preservation of some geometric characteristics. Lai et al. [14] proposed in 2019 a method based on exchange requirements (ER) to improve the transfer of structural information. Using the IFC standard and an ER matrix, they optimized the extraction of relevant data and reduced file sizes, improving interoperability between architectural and structural models through a workflow based on the Information Delivery Manual (IDM).

Birkemo et al. [16] analyzed BIM-to-FEM data transfer for a mixed structure of prefabricated concrete and steel, modeled in Revit® and transferred to Focus Konstruksjon®, Robot Structural Analysis Pro®, and SOFiSTiK®. Tests with native files and APIs revealed errors at connection points, geometric overlaps, and loss of information regarding materials, loads, and constraints. Direct links with native files between Revit and Robot proved more reliable, but they require an accurate workflow to avoid errors. Sibenik and Kovacic [12] in 2020 explored BIM-to-FEM interoperability using IFC and analyzed software such as Archicad®, Revit®, Allplan®, SCIA®, and RFEM®. The tests highlighted inconsistencies in exported/imported data and difficulties in managing connections and geometries. Unpredictable results, such as omissions of structural elements or incorrect interpretations, confirmed that the BIM workflow based on IFC remains unsuitable for ensuring effective data transfer between architectural and structural domains. Sibenik and Kovacic [12] also analyzed software compliance with standards required by buildingSMART®, comparing the MVD Coordination View 2.0 (CV V2.0) “concepts” implemented in the software during the certification process. They pointed out that information transfer issues often stem from incorrect implementation of standards. The MVD CV V2.0, supporting multiple domains, serves as an integrated model for data exchange between the architectural and structural domains, while domain-specific models should reflect their own concepts to communicate with specialized tools. Parametric approaches have been proven effective in handling complex geometries.

The lack of adequate standards to properly define import-export relationships between domains leads to inconsistencies in IFC models across different software. The authors attribute these issues to insufficient standardization of import/export functionalities, demonstrating that this compromises the reliability of data transfer between tools. Direct transfer from Revit® to Robot® via native files allows many architectural model details to be transferred to the structural model, but it presents inconsistencies, such as non-orthogonal analytical axes, requiring manual corrections, reducing model productivity and safety [17]. Despite these limitations, the workflow has shown time optimization and potential for integrating additional BIM dimensions.

Architectural–structural BIM interoperability faces critical challenges in data transfers, influenced using software and IFC standards (IFC2x3 and IFC4). Incomplete implementations of MVD standards, such as the adoption of Coordination View 2.0 instead of the Structural Analysis View, compromise the quality of data exchange, causing difficulties in managing information and unsatisfactory results, even for geometric elements.

Many software tools fail to correctly process data such as constraints, loads, or materials, requiring continuous manual re-entry, resulting in inconsistencies between design versions. Gaps in standardization and omissions in details concerning IFC and MVD formats limit the repeatability of studies and exacerbate uncertainties in interoperability.

The proliferation of diverse MVDs has prompted software vendors to select only a few for import or export, favoring transfers with native files. To improve IFC data exchange, a reorganization of standards and better coordination among software implementations are necessary. Sampaio et al. [10] analyze an applied case of architectural–structural collaboration through the integrated use of Revit® and Robot Structural Analysis®. The study demonstrates the advantages of a bidirectional information flow based on native files and the effectiveness of BIM in improving coordination and control. However, the authors point out persistent limitations in the use of IFC files, confirming that semantic interoperability remains an open challenge for the full integration of BIM-to-FEM workflows.

Despite the numerous advantages offered using BIM tools for structural design, there remains a significant amount of additional work, particularly concerning reinforcement detailing. However, despite these advancements, interoperability remains one of the most critical challenges in BIM-based workflows, particularly in multidisciplinary contexts where architectural and structural models must interact through heterogeneous software environments [18]. When information exchanges are incomplete, inconsistent, or distorted, the resulting analytical models may suffer from geometric inaccuracies, loss of connectivity, or semantic discrepancies that directly affect structural reliability and require extensive manual adjustments [19].

International studies on complex-built assets and underground infrastructures confirm that fragmented workflows, non-homogeneous data structures, and limitations in current exchange standards can cause significant information loss, coordination issues, and inconsistencies in model interpretation, affecting both design verification and safety-related decision-making [20]. Additional research shows that structured information models and well-defined exchange protocols are essential for supporting complex processes such as model federation, multi-scale representation, and discipline coordination [21]. Furthermore, evidence from infrastructure modeling demonstrates that ensuring consistency between geometric and semantic information is crucial for maintaining reliable data flows, especially when models are exchanged across BIM authoring and FEM analysis platforms [19,22]. The most efficient workflow, ensuring the best results in bidirectional information transfer, is achieved through direct transfers using native Revit®–Robot® files. In contrast, the use of alternative software, such as STAAD Pro®, leads to more complex workflows and reduced accuracy in information transfer. Research in this field requires a thorough evaluation of transfers between different BIM authoring and structural analysis software, extending this evaluation to reinforcement detailing as well [15].

Singh et al. [23] proposed a BIM-enabled framework for the automated design of reinforced concrete slabs using Python scripting and IfcOpenShell, which achieved significant reductions in design time and errors, highlighting the potential of open-source integration for structural interoperability. In a related study, Khattra et al. [24] developed an IFC-based automated code-checking system for seismic design, using a rule engine in Python to ensure compliance and reduce manual duplication in structural validation processes.

BIM tools are integrated and employed in conjunction with IFC OpenShell and Python to extract structural models from architectural models, thereby eliminating the need for proprietary or commercial software. This OpenBIM approach offers several advantages; however, it still presents certain challenges, particularly in terms of information interpretation and the overall effectiveness of the methodology [25].

In recent years, the use of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning techniques has begun to significantly influence the information flows connecting architectural and structural models. These methods provide valuable tools for addressing several critical issues typical of BIM-to-FEM processes, particularly when large amounts of heterogeneous or unstructured data must be handled. Recent literature shows that deep neural networks and hybrid models applied to Structural Health Monitoring can identify response patterns, anomalies, and indicators useful for updating or validating analytical models with greater consistency compared to traditional approaches [26].

At the same time, advances in automated compliance checking indicate that AI can support not only the automatic verification of regulatory requirements, but also the modification of the model when non-compliances arise. The most recent frameworks integrate topological analysis, solution-space exploration algorithms, and rule-based constraints, enabling the identification of problematic elements and the proposal of design alternatives that remain coherent with the overall model [27]. This approach proves particularly effective in situations where geometric consistency, spatial relationships, and design constraints must be maintained across architectural and structural models.

Another significant development concerns semantic enrichment methods, which combine ML algorithms and rule-based systems to improve the quality of IFC models. These techniques make it possible to classify elements more accurately, reconstruct missing relationships, and reduce the information loss that often occurs during export/import operations between different software platforms. This leads to more consistent analytical models, especially when the initial architectural model contains gaps or inaccuracies [27].

In the structural domain, several studies demonstrate how predictive models, optimization algorithms, and inverse-learning techniques can simplify iterative phases of analysis by enabling rapid evaluation of alternative solutions and improving the stability of the FEM model. Research on data-driven optimization for structural systems, particularly for steel structures, confirms the potential of ML-based predictive models to reduce manual interventions and streamline analytical model preparation [28].

Furthermore, the development of Graph Neural Networks introduces new opportunities for the analysis of complex structures defined by nodes and relationships. These models support the detection of topological inconsistencies, the verification of connections, and the validation of federated models, helping maintain structural coherence even in early interdisciplinary coordination stages [29].

Finally, computer vision techniques applied to digital reconstruction from images and point clouds allow for the automatic generation of coherent parametric models through semantic segmentation, object recognition, and geometric fitting. Such methods enhance the quality of the initial BIM model and facilitate its use in structural analysis software, with positive implications for the robustness of BIM-to-FEM interoperability [30,31].

Overall, the evolution of AI techniques applied to BIM processes is shaping a rapidly expanding research area. From advanced structural data processing to automated regulatory verification, from semantic enrichment of IFC models to digital reconstruction through computer vision, the most recent AI/ML solutions show growing potential to improve the coherence, reliability, and scalability of BIM-to-FEM workflows. Although these tools are still in the process of consolidation, current developments suggest that the integration of BIM and AI represents one of the most promising directions for the future of structural design and engineering.

3. Scope and Objectives

In this context, analyzing interoperability within BIM-to-FEM architectural–structural workflows become essential to understand the sources of information loss, the reliability of different exchange methods, and the impact on subsequent modeling and analysis stages.

This study aims to examine interoperability within the BIM design process, with particular focus on information exchange in the architectural–structural workflow (BIM to FEM). The selected case study concerns a residential building located in the municipality of Palermo. To perform the data transfer tests and develop the federated model, a set of software tools was employed, whose versions were explicitly documented to ensure reproducibility and accuracy in the interoperability assessment. The BIM authoring phase was carried out using Autodesk Revit® 2021 and 2024, while the structural analysis was performed with PRO_SAP® v.22.5.2, JASP® v.7.5, and Autodesk Robot Structural Analysis® 2021 and 2024. Model coordination and geometric verification activities were conducted with Navisworks Manage® 2021 and 2024, whereas IFC inspection and checking were carried out using Solibri Anywhere® v.9.13.5 and BIM Vision® v.2.27.5. Additionally, Enscape® v.3.2 was used for VR-based visualization and rendering of the structural model.

Information transfers were tested using different methods, which are described in detail within each test presented in the following sections. In particular, for indirect exchanges carried out through the IFC (Industry Foundation Classes) format, the main IFC schema used in the study was IFC2x3, which ensured broad compatibility across most of the software platforms involved. For structural workflows including PRO_SAP®, additional tests were also performed using both IFC2x3 Coordination View 2.0 and IFC4 Reference View (structural subset). The transferred data were examined through graphical comparisons, checks of information consistency, and verification of the elements composing the federated model. Finally, the study proposes an alternative procedure for generating the federated model, applicable to any structural software capable of exporting physical or analytical models in IFC-compliant formats, in order to produce a reliable federated model.

4. Methodology

Interoperability objectives in the architectural–structural design workflow can be achieved through various approaches to information transfer between software. These approaches are classified based on the transfer path and the functionalities of the involved software.

A primary classification can be made considering the software functionalities:

- BIM to BIM, which involves the exchange of information between two BIM Authoring tools.

- BIM to FEM, referring to the data exchange between a BIM Authoring software and a structural analysis software.

- FEM to BIM, which concerns the exchange of information between a structural calculation software and a BIM Authoring software [12,32].

Another classification can be made based on the information transfer path:

- Unidirectional, implying the exchange of information from one software to another.

- Bidirectional, involving the simultaneous exchange of information between different software.

Additionally, transfer paths can be distinguished as:

- One-to-one, where information is transferred from one software to another.

- One-to-many, where information is transferred from one software to many others.

- Many-to-one, where information is converged from many software to one.

- Many-to-many, where data is shared among various software [12,32].

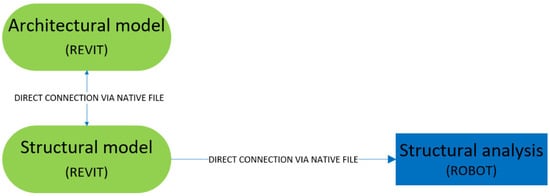

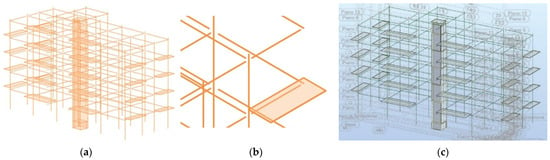

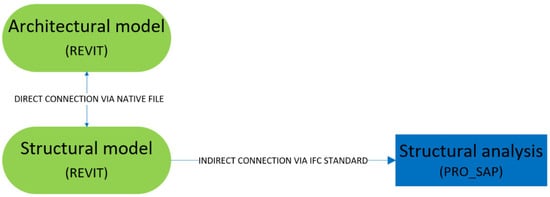

In the present study, various data transfer approaches were utilized. The architectural model was developed using the BIM Authoring software Revit®, one of the most widely used in scientific literature [9,13,14,15]. For two information transfer tests, structural Modeling was performed with Revit, allowing a bidirectional flow of information in the cyclic architectural–structural design workflow. The transfer of information from the Revit® structural model to FEM structural analysis software was executed using two software: Robot Structural Analysis®, utilizing a direct link with native file, and PRO_SAP®, using an indirect link via IFC format [11,12,33]. Both BIM to FEM transfers were one-to-one and unidirectional.

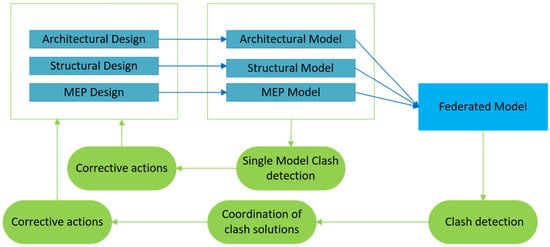

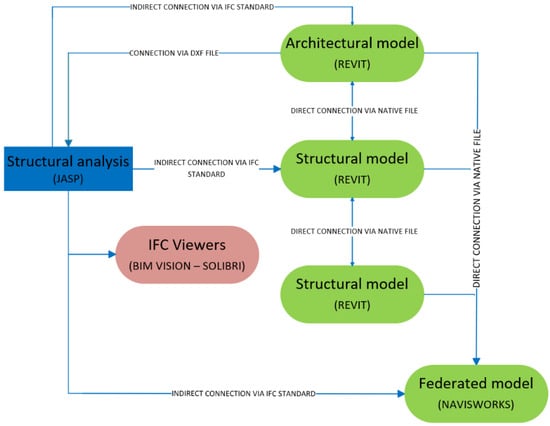

The FEM to BIM information exchange was tested with data transfer between the structural analysis software JASP 7.5® and Revit®, using the IFC standard. The models exported in IFC format were visually checked with IFC viewers BIM Vision® and Solibri Anywhere®, allowing the analysis of informational content. The many-to-one approach was used to generate the federated model, both with direct links with native file and indirect link via IFC format. The federated model was created on Revit® for comparisons and checks during architectural–structural and plant design. Each model created with Revit underwent interference analysis to correct design errors. The transfer of the structural model generated by FEM calculation software in IFC format to Revit® allowed testing the interpretation of information also with the visualization and rendering plug-in Enscape®. An additional federated model was created with Navisworks®, allowing testing of all imported models and performing interference analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Workflow for Model Construction and Interference Detection.

In this study, several data transfer workflows were examined with the aim of systematically assessing interoperability conditions and evaluating model behavior across heterogeneous scenarios. To support this analysis, a summary table was prepared (Table 1), consolidating the workflows considered and their corresponding verification objectives. The table provides an overview of the investigated cases and serves as a structured introduction to the detailed analyses presented in the subsequent sections.

Table 1.

Overview of the interoperability workflows tested in the architectural–structural design process.

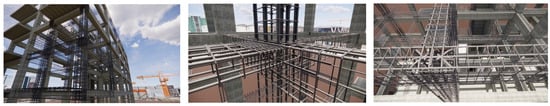

5. Case Study

The analysis model selected for this study is a residential building located in the municipality of Palermo. The structure is constructed using cast-in-place reinforced concrete, a technique that ensures high strength and durability. The building comprises five above-ground floors, with a rectangular plan measuring 27.90 m in length and 11.00 m in width. This geometric and structural configuration was chosen to represent a typical urban residential building. The choice of cast-in-place reinforced concrete is motivated by its widespread use and reliability in modern construction, providing a representative and relevant case study for advanced structural analysis.

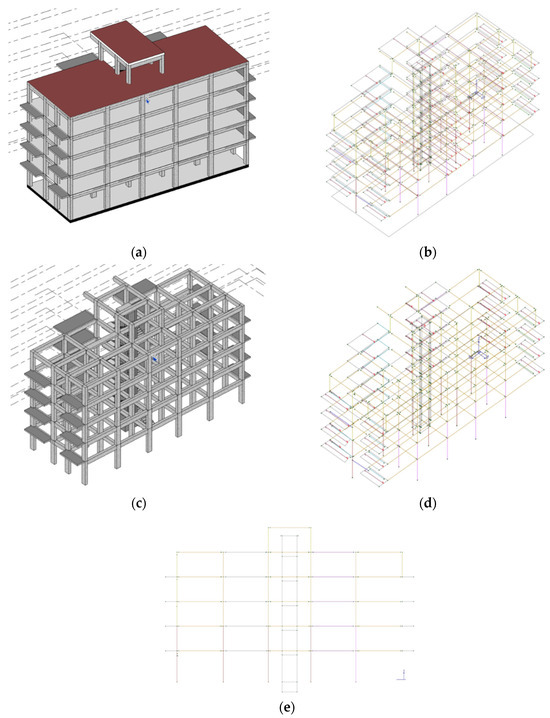

5.1. Structural Modeling

The architectural–structural design workflow of the building was characterized by a cyclic process, starting with the construction of a preliminary architectural model. In this model, grids were set up and infill walls and partitions were inserted, following the architectural concept guidelines. Subsequently, the architectural file was imported as a link into the structural file in Revit®, providing the initial references necessary for the construction of the structural model. For the structural Modeling, it was necessary to generate the insertion levels. Starting from the plan and elevation references, the first operation for constructing the structural model in Revit was the creation of column families and their insertion in a plan view. In the parameterization of the reinforced concrete column families, only the information strictly necessary for the analyses was included, namely the material (CLS C25/30) and the approximate dimensions obtained through preliminary sizing.

Parallel to the insertion of the columns, the structural beam families were created, in which all the necessary information was inserted, similarly to what was performed for the structural columns. In accordance with UNI 11337-4 [34], the structural elements used in this case study were modeled with an overall LOD C for columns and beams, incorporating a Level of Information (LOI) consistent with analytical requirements (material class, section dimensions, functional role, and structural typology). This choice reflects the project phase and ensures the amount of information necessary for FEM interpretation without introducing non-essential construction-level details. This Modeling methodology ensures a high degree of precision and consistency in the transfer of information between the architectural and structural models, facilitating the analysis and verification of design solutions. Moreover, the use of parametric families allows for easy adaptation of the structural elements’ characteristics to the specific project requirements, improving the design process efficiency and reducing the risk of errors.

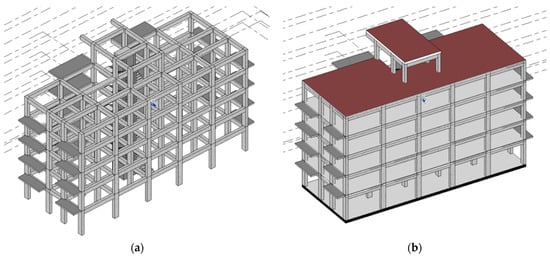

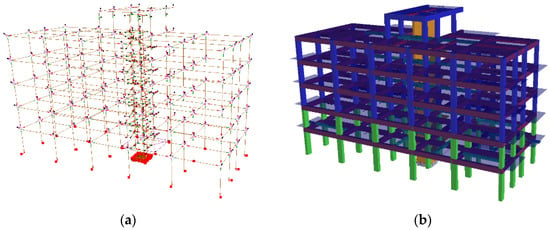

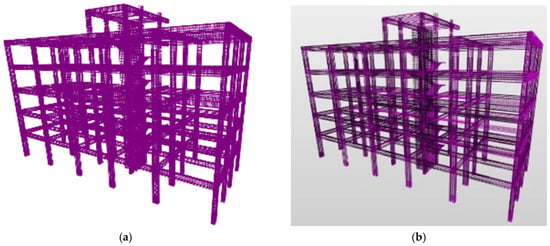

With the insertion of beams and columns for each level of the project, it was possible to obtain the building’s frame structure model (Figure 2a). The structural model in Revit® was completed with the insertion of the balcony slabs and stairs (Figure 2b). However, a significant limitation is encountered in the structural Modeling with Revit® in the representation of cast-in-place hollow core slabs, especially when an executive detail level LOD D is required, according to the Italian standard UNI 11337 [34].

Figure 2.

(a) Structural frame of the building; (b) Complete structural frame with cast-in-place hollow core slabs and stairs.

The cast-in-place slab is characterized by a variable configuration, composed of multiple elements, which can include solid and semi-solid bands, as well as break beams. Revit® has a command for generating the structural floor configured as a stratigraphic element, but it does not allow further characterization of the individual layers. Although it is possible to create a parametric family that also includes the hollow blocks, there are currently no demonstrations of the correct transfer of information to the structural calculation software. The hollow core slab in Revit® is represented as an architectural element comparable to an LOD B and LOD C, as it does not present a real representation of the hollow blocks, but only a stratigraphic indication [34]. Consequently, for the slab elements the level of development could not exceed LOD C, with a reduced LOI limited to the specification of material, thickness, and structural function, without including a detailed representation of hollow blocks or reinforcement layouts. This modeling resolution may affect the accuracy and stability of data transfer during IFC-based exchanges. This limitation may also influence the reliability of structural analyses, making a more detailed and specific modelling approach necessary for these components when advanced performance assessments are required.

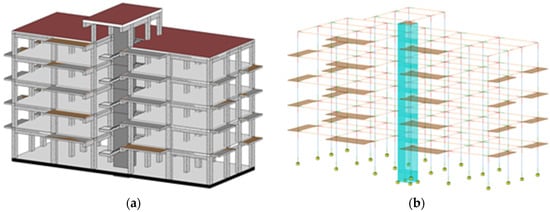

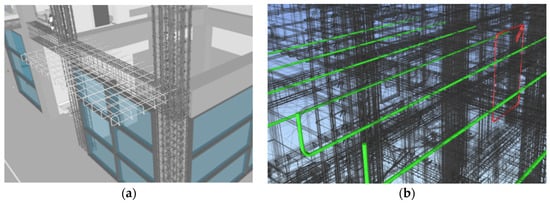

5.1.1. Information Transfer with Native Files

Starting from the same structural objects inserted in the model (Figure 3a), Revit® v.2021 software allows the automatic generation of the analytical model corresponding to the various modeled structural elements (Figure 3b). This functionality enables the insertion of constraints, loads, and load combinations, as well as the verification of the congruence of the generated model. However, the analytical model automatically generated by Revit® presents some significant limitations. It is important to note that the analytical instabilities and misinterpretations observed during the BIM-to-FEM transfer are partly attributable to the LOD/LOI adopted in the structural model. The use of LOD C elements, appropriate for design coordination, does not always provide sufficient analytical-specific attributes to support a fully automated conversion to FEM entities, particularly for elements requiring advanced connectivity rules or parametric discretization.

Figure 3.

(a) Complete structural frame with cast-in-place hollow core slabs and stairs; (b) Analytical model of the structural frame generated with Revit® v.2021.

One of the main limitations encountered is the absence of information regarding cast-in-place hollow core slabs and stairs, despite these elements being present in the structural model. As suggested by Gomes et al. [17], to include stairs in the analysis model, inclined solid concrete slabs could be inserted. This solution, however, would require subsequent manual insertion of the correct reinforcement, increasing the complexity and time required for modeling.

These limitations highlight the need to develop advanced methodologies and modeling tools that can overcome such deficiencies, ensuring a more accurate and complete representation of structural elements. The integration of detailed information on cast-in-place hollow core slabs and stairs in the analytical model is crucial to improve the precision of structural analyses and the consistency of information transferred between different design and calculation software.

For the first test of information transfer from the structural model to the calculation model, a direct link using native files was employed, utilizing Revit® v.2021 and Robot Structural Analysis® software, both developed by Autodesk® (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Workflow for architectural–structural information transfers with REVIT and ROBOT software.

During the information transfer between Revit® and Robot® software, inconsistencies regarding the non-orthogonality of the analytical model axes were detected (Figure 5), confirming the findings of Gomes et al. [17]. This interpretation issue is due to Revit® automatically recognizing the central points of structural elements as nodes in the calculation model. Such inconsistencies, occurring in complex design situations typical of BIM applications, can lead to the generation of erroneous analytical models which, if directly imported into the analysis software, can cause severe errors in the design of structural components. Among the main benefits of native Revit-Robot file exchange (2022 versions), the bidirectional transfer of information stands out, enabling efficient modifications without duplication. However, some limitations remain, such as the inability to transfer the reinforcement of slabs and certain foundations from Robot® to Revit® [4].

Figure 5.

(a) Structural frame on Revit® v.2021 with structural BIM elements; (b) Analysis model on Revit® v.2021—only with axes, nodes, and geometric planes; (c) Analysis model on Robot® v.2021 with axes, nodes, and geometric planes.

In the 2021 version of Revit®, some commands are available to make corrections to the analytical model before its transfer to the analysis software. However, the workflow of automatic generation and correction of the model, when working with complex models, might lead the designer to lose control of the analytical model. Additionally, any modification of the structural model elements requires further operations to modify or check the entire analytical model.

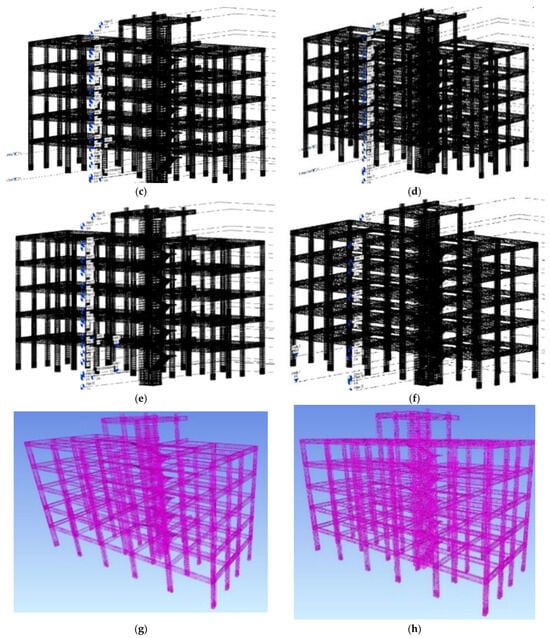

With the 2024 version of Revit®, several modifications have been made to the software to address these issues. The analytical model is no longer automatically generated with the insertion of the structural element; instead, a specific automation command has been introduced. This command allows the generation of an analytical model from the structural model and vice versa, enabling the insertion of interpretation inputs for information conversion. However, the tests of information transfer with this new functionality did not achieve satisfactory results (Figure 6a). The analytical model created with this procedure presented numerous node disconnections (Figure 6b,c), also detected in the information transfer to Robot®.

Figure 6.

(a) Analytical model in Revit® v.2024, only with axes, nodes, and geometric planes; (b) Detail of the disconnections in the analytical model in Revit® v.2024; (c) Analytical model in Robot® v.2024, only with axes, nodes, and geometric planes.

The issues related to the automatic conversion of data between the structural model and the structural analysis model are still present. The software developers have taken this aspect into consideration, introducing a command in the 2024 version of Revit® that allows the manual creation of the analytical model. This manual generation method offers many advantages, as the insertion always starts from the references of the individual structural elements, leaving the interpretation of the analytical model entirely to the designer. Despite the advantages offered by this type of information transfer, thorough validation of the structural analysis model by users remains essential, along with the partial remodeling of missing or incorrectly interpreted elements. A quantitative assessment was carried out based on the percentage of structural elements correctly imported after each transfer workflow (Table 2). The metric was defined as the ratio between correctly interpreted objects and the total number of modeled objects for each category (columns and beams), as well as for the geometric characteristics of the model (alignments and nodes). The results show that information related to columns and beams is transferred with complete reliability in both versions, whereas the geometric attributes associated with alignments exhibit noticeable precision losses. The 30% reduction in alignment accuracy observed in the Revit–Robot v.2021 workflow is attributable to nodes where beams with different cross-sectional dimensions intersect. Despite resolving these alignment issues, node connectivity emerges as the most critical parameter in the Revit–Robot v.2024 transfers. Even after testing multiple settings for the semi-automated generation of the analytical model, the new analytical model generation logic introduces significant instability, with correct import rates for this feature not exceeding 20%.

Table 2.

Import success rates for structural elements, alignments, and node connectivity via native file transfer.

5.1.2. Information Transfer with IFC Files

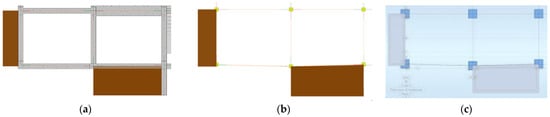

For an additional test of information transfer from the structural model to the calculation model, an indirect link using IFC format was employed, utilizing Revit® v.2021 and the calculation software PRO_SAP® v.22.5.2 (Figure 7). The first step of this process involved exporting the structural model from Revit in IFC format, using the preset configuration IFC2x3 Coordination View 2.0. The structural model was exported in IFC format in two variants: one with slabs (Figure 8a) and one without slabs (Figure 8c).

Figure 7.

Workflow for architectural–structural information transfers with REVIT and PRO-SAP software.

Figure 8.

(a) Structural model exported from Revit® v.2021 with slabs; (b) Analytical model imported into PRO_SAP®, with slabs; (c) Structural model exported from Revit® v.2021, without slabs; (d) Analytical model imported into PRO_SAP®, without slabs; (e) Analytical model imported into PRO_SAP®, highlighting the absence of some structural elements.

The IFC files exported from Revit® were subsequently imported into the FEM calculation software PRO_SAP®. During the import phase, the software identifies the elements of the IFC file and offers options for importing these elements into the calculation software. However, the elements imported into PRO_SAP® presented node disconnections and slabs detached from other elements of the structural frame (Figure 8b,d). To resolve these inconsistencies, the software provides semi-automatic commands that allow individual correction of various issues present in the calculation model imported as IFC. The correction of connections between structural elements can be performed in semi-automatic mode, by setting an influence radius within which the software should restore the connection, or in automatic mode. Despite the availability of these tools, satisfactory results in the analytical model were not achieved, as persistent disconnections in nodes and slabs were detected. Additionally, the issue of non-transfer of some structural elements was encountered (Figure 8e). The incorrect importation of some elements into PRO_SAP® was also verified in the “Log file” generated during the import, where problems related to the importation of elements are indicated. Furthermore, with this type of transfer, it was not possible to export information on constraints, loads, and stairs.

This import test highlights that the transfer of information from the structural model to the structural analysis model requires manual adjustments or reconstruction of the model to ensure the accuracy and reliability of structural analyses. Similar results were obtained when using the IFC4 Reference View (structural subset), which did not resolve the disconnections nor improve the completeness of the imported model.

The tests conducted, both with native file transfer and via open IFC format, highlight that the transfer of information from the structural model to the structural analysis model does not occur smoothly and is subject to various issues. Similarly to what was observed for the native Revit–Robot file transfer, a quantitative analysis based on the percentage of correctly imported structural elements was also conducted for the IFC-based transfer from Revit to PRO_SAP (Table 3). The results show that the geometric information of the model, specifically alignments and nodes, is transferred with complete reliability, whereas information related to columns and beams exhibits noticeable losses. The 65% accuracy obtained for columns is primarily attributable to the non-transfer of some elements and to incomplete information in others. The 80% value reported for beams, on the other hand, is solely due to missing information, such as material properties, despite all elements being geometrically present in the imported model.

Table 3.

Import success rates for structural elements, alignments, and node connectivity via IFC transfer.

The use of automation tools requires conscious modeling, which includes the application of a series of manual adjustments by the designer on the generated model. Manual adjustments may involve the modeling or reconstruction of missing structural members, the realignment of non-orthogonal elements, the reconnection of misaligned or fully disconnected nodes, as well as the insertion or correction of boundary conditions, the reassignment of material properties, and the application of loads that were not transferred or were incorrectly interpreted by the analysis software. These operations are often essential to restore geometric–structural consistency and ensure a reliable analytical model. After each information transfer, it is essential to perform a careful analysis of the errors and warnings generated, intervening where possible to resolve them. Additionally, a systematic check of the information transferred to the calculation software is necessary, considering parameters such as geometry, constraints, loads, and other relevant structural aspects. Even with this type of information transfer, a thorough validation of the structural analysis model by users is necessary, along with the possible re-modeling of missing or incorrectly interpreted elements.

5.1.3. Information Transfer with DXF Files and Partial Model Reconstruction

An additional verification of data transmission was conducted by developing the reverse flow of information through an indirect link based on the Industry IFC format. Specifically, the transfer was analyzed starting from the calculation software towards BIM Authoring tools.

A possible alternative to reorganizing the model after transfer involves the independent development of the structural calculation model, leveraging the capabilities of the IFC format for exporting executive information related to the structure into the architectural and federated model. Given the importance of structural calculation in the design process, a more rigorous control of input and output data of the model could compensate for the increased burden of constructing an additional calculation model. For structural modeling and analysis, the finite element software Jasp®, version 7.5, was used, which can generate output files in IFC format containing information on the structure and reinforcements. Jasp® is a commercial software for structural design, allowing verification and design at ultimate and service limit states for reinforced concrete, steel, and wood structures, in accordance with Italian NTC-2018 standards and Eurocodes.

However, Jasp® currently supports data import only through DXF files and does not allow IFC loading. Consequently, the transferred information is limited to geometric references, while semantic and structural data are lost, requiring additional manual reconstruction of the analytical model. Despite this limitation, it can currently be considered acceptable. In fact, even in structural analysis software that supports IFC data import, difficulties have been encountered in the correct exchange of architectural–structural information, still necessitating the reconstruction of the structural model from scratch for analysis. This approach is applicable to most of the commercially available software currently in use. Although the reconstruction of the analysis model may be required, it enables the generation of a comprehensive BIM model of the structure, ensuring that structural designers retain full control throughout the entire process.

The export of the structural model in IFC format allowed further tests of data interpretation and the development of a federated model of the building, including information on structural reinforcements. Figure 9 illustrates the conceptual workflow of data transfers between the software used in the analysis. This type of workflow is compatible with most structural analysis software currently available on the market. Thanks to its flexibility, it can easily adapt to different platforms, optimizing calculation and simulation processes. In this way, it is possible to achieve precise results and efficiently manage data, improving the overall effectiveness of the project.

Figure 9.

Workflow for architectural–structural information transfers using the software: Revit®, JASP®, Solibri Anywhere®, BIM Vision®, Navisworks®.

The definition of the structural model began with the export from Revit® of a DXF file containing architectural references, then imported into Jasp, a finite element analysis (FEM) software.

With regard to the DXF-based transfers, only the correspondence of nodes and grids was evaluated (Table 4). The correct transfer of this information was verified through the subsequent overlay of the elements modeled in JASP with those re-imported into Revit. Although the geometric references imported via DXF fully match, this condition still generates measurable impacts, as it requires additional time for the complete reconstruction of the structural model. This phase, although facilitated by the availability of correctly transferred alignments and nodes, results in increased modeling time and, consequently, higher rework costs.

Table 4.

Import success rates for alignments, and node connectivity via DXF transfer.

From the DXF references, fixed lines were generated for the construction of the calculation model. Subsequently, the floors, materials, and sections for beams, columns, walls, and slabs were defined. Beams and columns were inserted by floors, while walls were modeled to represent the elevator shaft, to which a ramp slab staircase with three flights is anchored. Finally, slabs, balconies, and infill walls were added, considering preliminary sizing considerations.

Upon completion of the modeling, the three-dimensional structure model was obtained (Figure 10). Nodes were left free, except those on the ground floor, which were constrained as fixed supports. Additionally, a foundation slab was inserted in the elevator shaft, although it was not subject to structural verification. The definition of the structural model began with the export from Revit® of a DXF file containing architectural references, then imported into Jasp, a finite element analysis (FEM) software. Upon completion of the geometric modeling, in which materials and constraints were defined, the definition of actions was carried out, assigning the intended use of the structure. Subsequently, verification and design criteria were set and assigned to each element, essential for reinforcement sizing, geometric verification of elements, and section verification.

Figure 10.

(a) Three-dimensional model of structural connections; (b) Front view of the three-dimensional calculation model.

After setting the actions and analysis criteria, the structural analysis was initiated, including options for seismic analysis and load combinations. The numerical analysis was conducted using the displacement method, assuming linear-elastic behavior of the elements. The finite element technique was adopted, with connections defined at discrete points called nodes. The design and analysis phase concluded only after verifying all criteria and regulatory conditions, obtaining stress diagrams and structure verification.

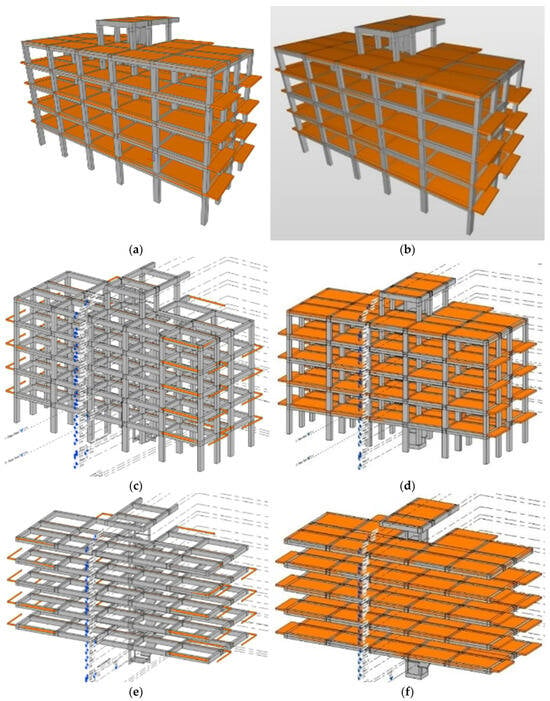

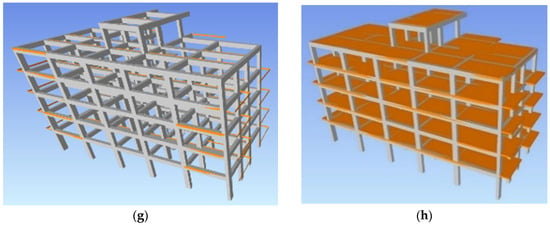

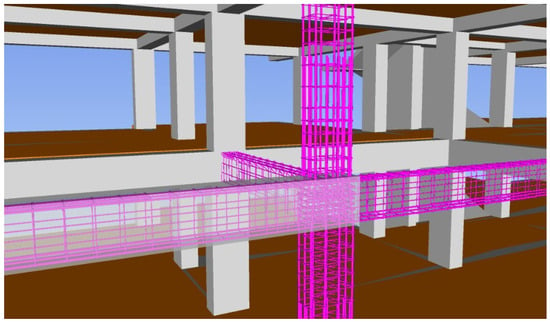

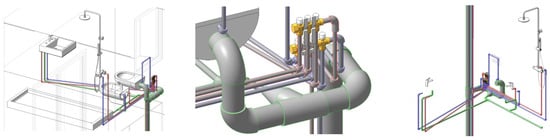

The structural model was subsequently exported from the FEM software Jasp in IFC2x3 format, with an unspecified MVD. An analysis of the buildingSMART® certified IFC software database confirmed the absence of IFC certification for Jasp®, making it impossible to determine the export requirements adopted. During the export, it was possible to filter the elements, generating two distinct IFC models: one containing only the reinforced concrete structural elements and slabs, and another containing only the reinforcements. An important limitation of the workflow concerns the use of structural analysis software that is not officially certified for IFC import or export, such as JASP®. The absence of IFC certification prevents verification of the actual implementation of the exchange schema and the supported entity set against the buildingSMART® requirements. As a result, the IFC output generated by such software may differ from standard-compliant formats in terms of property mapping, element classification, and geometric interpretation. This lack of standardization can lead to partial or inconsistent transfer of information, requiring additional checks and manual adjustments during the coordination process. Moreover, the non-certified nature of the software reduces the predictability and repeatability of interoperability results, limiting the generalizability of the workflow for industry applications where certified openBIM procedures are expected. Nevertheless, given that several widely used FEM tools in professional practice still lack IFC certification, the proposed workflow retains practical relevance by demonstrating how reliable coordination can still be achieved through systematic validation, selective filtering of IFC elements, and rigorous model checking across multiple platforms. Before use, both models were subjected to information transfer checks through visual and content analysis, performed by importing the IFC files into various software. The models were analyzed using IFC viewers BIMvision® and Solibri Anywhere®, as well as Revit® software (versions 2021 and 2024, in both structural and architectural domains) and Navisworks® (versions 2021 and 2024). The checks revealed significant discrepancies in data interpretation, particularly for the model containing the reinforced concrete structural elements and slabs (Figure 11a–h). Both IFC viewers correctly interpreted the model (Figure 11a–c). However, in the architectural domain of Revit® 2021, the slabs and balconies of the linked IFC model were incorrectly represented (Figure 11c), while no interpretation errors were found in Revit® 2024 (Figure 11d). In the structural domain of Revit® 2021, in addition to interpretation issues for slabs and balconies, there was a complete loss of information regarding the columns (Figure 11e). However, this information was still present in the side views of the model. In Revit® 2024, the interpretation of slabs, balconies, and beams was correct, but the information on columns was still absent (Figure 11f). The import of the IFC model into Navisworks Manage® showed results similar to those in the architectural domain of Revit® (Figure 11g,h). This could be due to the use of common exchange requirements between Revit® and Navisworks Manage® for data import. However, the lack of official IFC certification for Navisworks Manage® prevented verification of this hypothesis. In the buildingSMART® database, it was confirmed that Revit® uses the MVD Coordination View 2.0 for importing IFC2x3 files, both for the structural and architectural domains, but this did not explain the interpretation differences found between the different domains. The software version updates showed a general improvement in IFC information interpretation, suggesting a positive evolution in data interoperability between different platforms.

Figure 11.

Interpretation test of the structural model information exported from Jasp® software and imported into: (a) BIM Vision® v.2.27.5; (b) Solibri Anywhere® v.9.13.5; (c) Revit® v.2021 (architectural domain); (d) Revit® v.2024 (architectural domain); (e) Revit® v.2021 (structural domain); (f) Revit® v.2024 (structural domain); (g) Navisworks Manage® v.2021; (h) Navisworks Manage® v.2024.

The comparative analysis of the IFC model containing exclusively the reinforcements did not reveal any discrepancies in the interpretation of information among the different software used. Specifically, all the tools employed, including the IFC viewers BIM Vision® and Solibri Anywhere®, as well as the 2021 and 2024 versions of Revit® in the architectural and structural domains and Navisworks Manage®, correctly processed and represented the reinforcement information without import anomalies or data loss. This result indicates greater robustness and reliability in managing the IFC format for reinforcements compared to reinforced concrete structural elements and slabs, for which interpretative issues had been identified (Figure 12a–h).

Figure 12.

Interpretation test of reinforcement information exported from Jasp® software and imported into: (a) BIM Vision® v.2.27.5; (b) Solibri Anywhere® v.9.13.5; (c) Revit® v.2021 (architectural domain); (d) Revit® v.2024 (architectural domain); (e) Revit® v.2021 (structural domain); (f) Revit® v.2024 (structural domain); (g) Navisworks Manage® v.2021; (h) Navisworks Manage® v.2024.

The analysis of the information contained in the IFC files was conducted using the functionalities offered by the Solibri Anywhere® viewer. Within the IFC model related to reinforcements, in addition to geometric information, the material characteristics were also correctly transferred. The reinforcement bars were defined as IfcReinforcingBar entities within the IFC2x3 schema and classified under the architectural discipline. Additional information correctly imported into the IFC model includes the diameter, belonging plane, function, and positioning specifications of each reinforcement bar.

Similarly to the analysis of reinforcements, the information contained in the IFC file of the concrete components of the structure was examined. In this model, four categories of entities were generated: IfcColumn for columns, IfcBeam for beams, IfcWall for reinforced concrete walls, and IfcSlab for slabs, balconies, and plates. For the IFC model of the concrete structural components, the material information was also correctly transferred, except for slabs and balconies. The plate element, although classified with the same IfcSlab entity as slabs and balconies, retained the material information. This result could be attributed to the modeling methods adopted in the finite element software. Specifically, in the Jasp® software, the plate was generated as a Shell element and was not defined within the load section, unlike slabs and balconies.

A quantitative evaluation was also carried out for the BIM-to-FEM transfers from the JASP software using the IFC2x3 format, based on the percentage of structural elements correctly imported after each workflow (Table 5). The metric was again defined as the ratio between correctly interpreted objects and the total number of modeled objects for each category (columns and beams), as well as for the main geometric characteristics of the model (alignments and nodes). To verify correct importation, the results were compared with the imports performed in the BIMVision and Solibri viewers, where all elements were transferred completely and manually validated. The results show that information related to reinforcement elements and beams is transferred with full reliability across all tested versions, as are the geometric attributes associated with nodes. Information related to columns, however, was entirely absent after the transfer from JASP to Revit, when imported under the structural domain; this condition leads to a proportional loss of accuracy in alignments, which depend on the correct interpretation of column geometry. Information related to slabs was transferred correctly, except in imports performed with Revit 2021, where interpretation anomalies were observed. Finally, regarding the interpretation of information by the Enscape rendering software, the data were also processed correctly, as the transfer was carried out through Revit v.2024 configured in the structural domain.

Table 5.

Import success rates for structural elements, alignments, and node connectivity via IFC2x3 transfer.

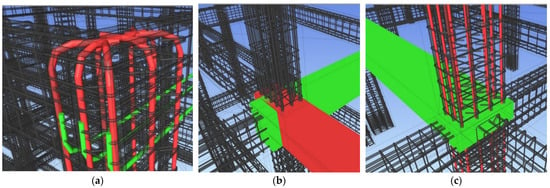

After verifying the correct transfer of information in the structural IFC models, further tests were conducted to evaluate their integration into coordination, clash detection, and analysis software. For this purpose, a geometric clash detection analysis was conducted on the structural IFC models using Navisworks Manage® v.2024 software. The analysis did not reveal any data interpretation errors in the generated structural IFC models. Structural IFC files were simultaneously imported into Navisworks®, allowing the creation of a federated structural model. The integration of the two models enabled the verification of the correct placement of the reinforcements within the concrete structure (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

View of the federated structural model on Navisworks Manage® v.2024.

The analysis carried out demonstrated the effectiveness of IFC models in identifying geometric clashes. However, many of the clashes detected by the software do not represent actual geometric conflicts but are instead the result of the IFC model generation algorithm used by the FEM software (Figure 14). In the examined case, “real” clashes refer exclusively to intersections between different elements, such as two reinforcement bars belonging to separate groups or interferences between unrelated structural components. These situations require design correction or model refinement. Conversely, several clashes reported as geometric conflicts should not be interpreted as errors, as they represent physiological intersections inherent to structural modeling. These include, for example, intersections between concrete components at structural nodes, or the apparent interference between the reinforcement of one beam and the concrete of another connected beam. These events arise from the natural overlapping of different structural node elements and do not constitute real design problems. The classification of real clashes is currently entrusted to BIM Coordinators or BIM Managers, who manage them through the functionalities available in Navisworks®. However, to further improve the accuracy of the verification process, a potential future development of coordination software could include the implementation of specialized algorithms capable of automatically filtering these non-critical geometric intersections, thereby distinguishing more effectively between permissible intersections and genuine design conflicts. An even more advanced evolution could involve the use of artificial intelligence algorithms for the automatic classification of clashes, capable of learning from recurring patterns in structural models and progressively improving the accuracy of clash identification.

Figure 14.

Geometric interferences detected with Navisworks software: (a) between reinforcing bars; (b) between concrete beams; (c) between reinforcing bars and concrete beams.

The tests conducted have demonstrated that the creation of a structural model in IFC format allows for the correct identification of potential construction interferences already in the design phase. Additionally, structural IFC models offer the possibility to visualize the model even on-site, proving particularly useful in complex situations where the interpretation of 2D executive drawings may generate doubts. This approach optimizes the computation of reinforcement and structural quantities, enhancing both time efficiency and accuracy. The quantities of structural elements and reinforcement requirements can be automatically extracted from the digital model, reducing manual intervention and minimizing the risk of errors. Furthermore, it facilitates more precise project planning and optimized resource management, contributing to greater efficiency and streamlining of construction processes [35].

The structural IFC model of reinforcements, generated with the FEM analysis software Jasp, is not completely accurate as it does not include the reinforcements of all types of structural elements, such as balconies. This situation is common in professional practice, where it may be necessary to perform structural analyses with different software and subsequently integrate the results into a complete structural model. To simulate this circumstance, the reinforcements of the balconies were modeled with Revit® software, in order to verify the model checking functionalities between reinforcement elements from different software (Figure 15). From the clash detection analysis performed on the federated model, which includes both the structural model created with Revit and the structural IFC model generated with Jasp, it emerges that the information from the two structural models is correctly combined and interpreted. This process allows for the identification of all possible interferences between the balcony reinforcement group and the beam reinforcements. The integration of structural models into a single federated model allows for a more precise evaluation of geometric interferences, improving project quality and reducing the risk of errors during the construction phase. The ability to detect geometric interferences between structural elements from different software is essential to ensure project consistency and reliability, facilitating collaboration among the various professionals involved. Furthermore, the use of advanced clash detection tools, such as those offered by Navisworks®, allows BIM Coordinators and Managers to effectively manage the detected interferences, optimizing the project review and approval process. This integrated approach helps improve communication between design and construction teams, ensuring that all issues are addressed promptly and accurately.

Figure 15.

(a) View of the federated model on Navisworks Manage® v.2024 with the detail of reinforcements modeled on two different structural software; (b) Detection of a clash using Navisworks® software, related to the reinforcement bars of two different structural models, coming from Revit® v.2024 and Jasp® v.7.5, respectively.

An additional test for the interpretation of information was conducted to verify whether the data from the structural IFC model, imported into Revit®, were correctly interpreted by the plug-ins installed on Revit®. In this case, the test was limited to the use of the Enscape plug-in, which allows for rendering and virtual reality (VR) visualizations of the models. From the tests conducted, it emerged that the information from the imported IFC model is perfectly combined and visualized together with the Revit model data. This allowed for the generation of photorealistic views of the structural IFC model and navigation within it in VR mode using appropriate headsets (Figure 16). The integration of IFC model information with Revit® model data, even using plug-ins like Enscape®, represents a significant advancement in the visualization and interpretation of structural data. This approach allows for greater precision in model representation and facilitates the understanding of complex structures, improving project quality and construction process efficiency.

Figure 16.

Photorealistic views obtained with the Enscape® plug-in for Revit®, based on the imported structural IFC model from the structural analysis software.

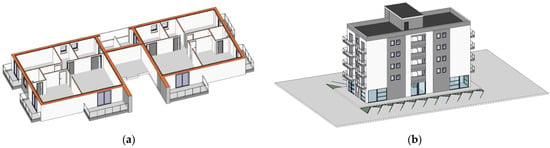

5.2. Architectural, MEP Modeling and Federate Model

The architectural design of the building was developed in parallel with the structural design. Using Revit® software, an architectural model file was created (Figure 17). The initial phase involved the layout of grids and the modeling of the typical floor plan, which was crucial for defining the corresponding structural model. During the iterative process of architectural and structural design, information transfers between the two disciplines were smooth, with no data loss. Information exchanges occurred both through direct linking of native files between the architectural and structural models created with Revit®, and through indirect linking using the IFC standard, between the structural model created with the FEM software Jasp® and the architectural model created with Revit® v.2024. The building design was executed at an executive level, with an object development level comparable to LOD D, according to UNI 11337-4 [34]. While the architectural model reached LOD D in accordance with the structural model was intentionally developed at different LODs depending on the element category. Columns and beams were defined at LOD C, slab systems at LOD C, and reinforcement was modeled at LOD C exclusively within the FEM environment. The corresponding LOI levels were aligned with analytical and coordination requirements, rather than with executive-level detailing. The ability to link the structural model to the architectural model was fundamental for the correct placement of certain elements. For example, it was possible to correctly position the architectural slabs, taking into account the actual thicknesses of the screed and flooring from the respective structural level of the slab. Similarly, for the insertion of infill walls, it was possible to refer to the actual size and positioning of the columns from the imported structural file. The architectural modeling of the building was completed with the insertion of all the constituent element families, such as doors, windows, railings, etc. Parametric models of various construction elements were sourced from online platforms, where models provided directly by manufacturers are available, while some were specifically created as parametric objects using Revit® functionalities. The modeling performed allowed for the creation of an architectural model containing exclusively elements pertinent to the architectural discipline. The structural elements linked in the architectural model belong exclusively to the structural discipline. Linking the different models promotes information sharing without the possibility of modifications to the linked files, thus avoiding potential errors during the design phase of the project. Additionally, data sharing through linking allows for the generation and management of files containing only disciplinary information, avoiding duplication and overlap of data between different models.

Figure 17.

(a) Architectural section of the typical floor plan; (b) Axonometric view of the architectural model created with Revit® v. 2024.

The use of BIM methodology for design offers multiple advantages. The BIM model, in addition to providing a representation of the project close to reality, is an information container that can be consulted and updated throughout the life of the project. From the BIM model, technical drawings can be extracted for various objectives and levels of detail, the model can be queried to extract various types of information, and customized and dynamic schedules can be created that automatically update with each modification made to the model.

The use of Revit® software for architectural modeling allowed for the identification of inconsistencies and design errors through clash analysis of the model itself. The identification of clashes proved particularly important, as it enabled the resolution of errors during the architectural modeling phase, before sharing the file with other disciplines. Starting from the same BIM model, it is possible to create photorealistic views and, with the aid of specific plug-ins and headsets, visualize the model in Virtual Reality (VR) mode. The model elements already contain all the graphical information related to materials, which are transferred to rendering software to generate photorealistic views. Information transfer tests were conducted, obtaining photorealistic views using the Enscape® v.3.3 plug-in (Figure 18). Through Enscape®, it was possible to integrate the building’s BIM model with furniture and vegetation elements, creating realistic external and internal environments of the completed work.

Figure 18.

Photorealistic external and internal views of the architectural model created with Revit.

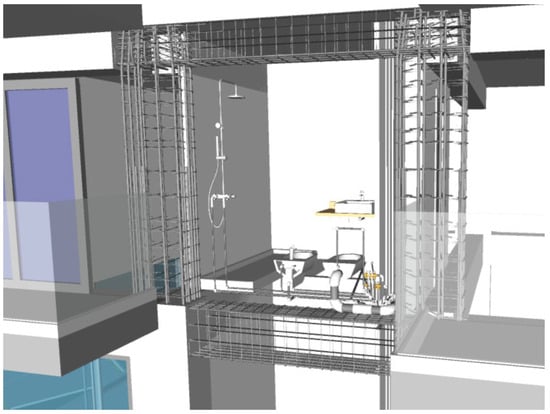

In building design, the transfer of architectural and structural information is crucial for MEP (Mechanical, Electrical, and Plumbing) design. To evaluate the correct interpretation of information between the structural and MEP models, a portion of the building’s plumbing system was modeled (Figure 19). This modeling was performed using Revit® BIM Authoring software, based on references from the linked architectural and structural models. Thanks to functionalities of Revit®, it was possible to verify the connection of all parts of the system and conduct clash analyses on the system components. However, clash detection performed with Revit® has the limitation of being able to execute clash analyses only on models created with Revit® and imported as direct links through native files. For clash analysis between models linked indirectly via the IFC standard, specific software such as Navisworks® is required.

Figure 19.

Views of the sanitary plumbing model.

The last application of information transfer was of the “many to one” type, with the aim of evaluating the interpretation of information for the construction of the federated BIM model (Figure 20). In the context of digital processes applied to structural design, federated models and analytical models fulfill distinct yet complementary roles, each grounded in informational and performance logics that are not mutually substitutable. The federated model functions as an integrated container of heterogeneous representations: architectural, structural, and MEP, while preserving their respective authoring environments. This configuration supports the consolidation of geometric and semantic consistency across disciplines, enabling coordinated oversight of the project as a whole, including the detection of geometric interferences and the verification of spatial compatibility conditions. The absence of data merging into a single editable file safeguards the integrity of the source models and facilitates a more transparent and verifiable multidisciplinary coordination process. Analytical models, conversely, must be managed as autonomous entities, as they rely on discretization procedures, load definitions, constitutive formulations, and boundary conditions that have no direct or unambiguous counterpart within BIM data structures. Numerical analysis requires a degree of detail and parametric control that cannot be ensured through automated BIM-to-FEM conversions or general-purpose openBIM workflows. Maintaining the analytical model independent grants the structural engineer full control over modeling decisions in accordance with technical standards and computational stability requirements, reducing the risk of distortions arising from geometric translations inconsistent with finite element analysis principles.

Figure 20.

View of the federated model on Navisworks® with the detail of elements from models imported from different modeling and structural analysis software.

Consequently, the federated model constitutes the reference environment for coordination activities, geometric validation, and interdisciplinary information exchange, whereas the analytical model remains essential for structural verification and computational analysis. The coexistence of these two approaches, each serving its specific purpose, represents the most robust and reliable methodological configuration within contemporary BIM–FEM interoperability workflows.

For the creation of the federated model, Navisworks Manage® v. 2024 software was used. The transfer of information from the architectural and MEP models occurred through direct linking with native files, while the information from the structural model was transferred through indirect linking using the IFC standard. It was possible to verify that all information was correctly transferred and, through clash analysis, the functionality of the different models after the transfer was evaluated. The federated model was analyzed in terms of graphical congruence and element positioning, comparing them with the individual imported models. Further checks were conducted regarding the correspondence and completeness of the information, analyzing a sufficient number of element samples and comparing their information with that present in the individual source models. The information verification was carried out using Navisworks®’ selection structure, which allowed tracing the information of all elements imported into the federated model. The creation of the federated model facilitated information sharing and coordination, as well as enabling interference control between models of different disciplines. This process allowed for the identification and management of issues, conflicts, and inconsistencies arising from the overlap of various models. The ability to perform correct model federation enabled effective coordination of the different disciplines involved, creating a common information base for all stakeholders. Starting from the federated model, it was possible to obtain customized views showing the distribution of different elements, providing additional information compared to that obtainable from consulting the individual disciplinary models. Furthermore, it was verified that, using Navisworks® software, it is possible to create a single federated model without information loss, both with direct and indirect links, integrating reinforcements modeled with two different software.

6. Results and Discussion

The tests conducted on the transfer of information from the structural model to the structural analysis model revealed an improvement in direct information exchange via native file, Revit® to Robot®, despite still encountering significant limitations that may not provide the necessary assurance of the correctness of the structural analysis model after the transfer. The Revit®–Robot® interoperability shows great potential, but the automatic generation of the analytical model does not yet allow for the development of a solution that is always correct and therefore still often requires manual checks. Despite the construction of the structural model implemented in Revit® offering full interoperability with the corresponding architectural model created with the same software, it is still evident that there is an information gap with the structural analysis software Robot®, belonging to the same software house. Based on these observations, interoperability in the BIM workflow can be distinguished into:

- Interoperability between the architectural model and the structural model, which already shows excellent results in information exchange.

- Interoperability between the structural model and the analysis model, which still presents limitations, mainly related to the automated geometric interpretation of the structural model for the generation of the corresponding analysis model.

The interoperability outcomes must also be interpreted in light of the LOD and LOI adopted in the structural modeling phase, since the level of geometric detail and the richness of non-graphical attributes directly affect the robustness of BIM-to-FEM mapping. The partial inconsistencies detected in analytical axes, connectivity, and slab interpretation are consistent with the information depth corresponding to LOD B and LOD C elements, confirming the strong dependency between modelling granularity and interoperability reliability. From the evaluation of the current state of the art in information exchange between the architectural and structural domains, it is evident that there are still some issues in data interpretation. In particular, many of the causes of these issues should be attributed to incorrect implementation of international exchange standards in the software, including IFC and MVD. A comparative analysis conducted based on the proposed case study already reveals a good interpretation of information in the transition between different domains and different software, both with direct exchange via native file and indirect use with the IFC format. The unresolved issue lies in the interpretation of the geometric-structural model information for the generation of the corresponding structural analysis model. Even in this aspect, there has been interest from software houses in seeking a possible solution. However, to date, no satisfactory solutions have been presented for the automation of this process. The tests conducted show that in recent years there has been a significant increase in interoperability between different software, noting some improvements regarding information transfer even through the IFC exchange format. It is still demonstrated that the BIM methodology can be effectively used in the development of a structural project using alternative solutions, with significant positive contributions. In the proposed work, some analyses of the interoperability limits related to the software used were addressed, and a proposal was made to achieve a federated BIM model that effectively includes the structural model. Among the limits related to the use of possible alternative solutions are certainly the decrease in productivity during the adaptation or re-modeling phase of the analysis model, which is linked to the higher probability of making design errors. Another issue encountered is the need to modify two models for each structural change made during the design phase. Although the proposed workflows improve reliability in both BIM to FEM and FEM to BIM exchanges, the study confirms that relevant limitations still constrain the overall efficiency of the process. Inconsistencies such as node disconnections, partial loss of element properties, or incomplete semantic transfer often require additional modelling time for manual corrections, and this effort increases in proportion to the number of elements affected. These corrective actions also raise rework costs, particularly when analytical nodes must be reconstructed or when geometric references need to be realigned before structural analysis. Moreover, inaccuracies that propagate across architectural, structural, and MEP domains heighten coordination risks, since errors introduced at the analytical stage may influence decisions in other disciplines and trigger additional revision cycles. These findings indicate that current BIM to FEM and FEM to BIM interoperability still relies heavily on expert supervision and detailed model checking, and they underline the need for more robust and standardized procedures that can better support the scalability of such workflows in larger or more complex projects.