Abstract

Steel frame structures have been increasingly widely used in high-rise and multi-story building design. However, traditional rigid welded beam–column joints exhibit poor ductility and high residual stress, which are key reasons for their susceptibility to brittle failure under strong earthquake actions. This study proposes a new type of beam–column joint for steel frames: the corrugated web beam–column joint. In this new joint, the web of the I-beam near the beam flange is partially replaced with a corrugated web that exhibits a folding effect—this modification weakens the plastic bending capacity of the I-beam and promotes the outward movement of plastic hinges. Low-cycle reciprocating loading tests were conducted to verify the performance of two specimens, namely one with the traditional beam–column joint and the other with the corrugated web beam–column joint. Through experimental comparison, it was found that plastic hinges in the new corrugated web joint are generated at the corrugated web, while no damage occurs at the beam-end welds. This indicates that the corrugated web beam–column joint can stably achieve the outward movement of plastic hinges and avoid the location of the beam-end welds, thereby providing theoretical and experimental foundations for the structural design of new ductile steel frames.

1. Introduction

The 1994 Northridge Earthquake (USA) and 1995 Kobe Earthquake (Japan) reshaped the engineering community’s understanding of traditional steel frame joint seismic performance. Previously, the strong column–weak beam, strong joint–weak member paradigm held that steel ductility would form stable plastic hinges at beam ends (for seismic energy dissipation) and protect joints. However, these earthquakes caused unexpected brittle failures: in the Northridge Earthquake, beam-end welds cracked before reaching full plasticity, with crack propagation leading to joint failure even though no steel buildings collapsed; in the Kobe Earthquake, beam-end welds also exhibited brittle cracking that triggered joint failure, while collapses of steel buildings were mostly attributed to column failures rather than brittle beam-end fractures [1,2]. Subsequent studies revealed a core issue: defects such as welding residual stress and incomplete weld penetration prevent material ductility from translating to joint ductility [3,4], which has driven global research on enhancing ductility, controlling failure modes, and adapting to complex scenarios—yet gaps remain in multi-performance coordination.

In traditional joint optimization, Tao Changfa et al. [5] verified via substructure tests that cover plates shift plastic hinges to beam ends, protect welds, and improve energy dissipation. Tong Genshu [6] corrected connection coefficients for short beams to resolve cover plate design conservatism. Ha M H et al. [7] emphasized the role of panel zone mechanical behavior in refining traditional joint design, while Kulkarni S A et al. [8] clarified the guiding effect of reduced beam sections (RBS) on plastic development. Corrugated web joints—key to this study’s new design—overcome flat web defects with superior out-of-plane stiffness. Yu Chenyang et al. [9] optimized stud arrangement to suppress flange instability in embedded corrugated web connectors, ensuring full shear performance. Nouri G et al. [10] systematically studied trapezoidal corrugated web RBS (TCW-RBS) joints and defined their cyclic loading energy dissipation and failure modes. Mansouri A et al. [11] proposed two new corrugated web RBS configurations to expand applications; Yang T et al. [12] filled fatigue design gaps by studying the fatigue performance of stud connectors under transverse bending. Pang R et al. [13] revealed the flexural behavior of steel beams with double corrugated webs, while Li Z et al. [14] established shear buckling guidelines for sinusoidal corrugated web beams and quantified the relationship between corrugation parameters and shear capacity. Wang Y et al. [15] further expanded the application of corrugated webs to anti-progressive collapse scenarios via external corrugated plate-strengthened joints, and this approach was verified by numerical simulation.

High-strength steel joint research addresses the trade-off between strength and ductility. Chen Xuesen et al. [16] used finite element analysis to show that panel zone stiffness regulates force distribution between beam flanges and cover plates; they also identified shear reversal in web connections under seismic cycles and proposed bidirectional weld shear checks. Al-Ansi et al. [3] optimized cover plates for medium-wide flange H-beams, breaking traditional thickness limits to reduce material usage while maintaining ductility. Shi Gang et al. [17] developed a cyclic loading protocol for thick steel plate joints and defined reasonable thickness ratios to balance strength and ductility. Chen X S et al. [18] verified the plastic development of high-strength steel flange plate joints via cyclic tests.

In addition to the above component-level and joint-level mechanical research, machine learning has emerged as an auxiliary tool for structural dynamic response prediction and seismic damage assessment in recent years. Li et al. [19] proposed a graph neural network (GNN)-based approach for full-field structural dynamics prediction, which can simulate spatiotemporal dynamic responses with higher efficiency than traditional numerical methods while ensuring prediction accuracy for displacement, strain, and stress fields. Lazaridis et al. [20] adopted interpretable machine learning techniques (e.g., SHAP and PDP) to assess cumulative seismic damage of reinforced concrete frames, identifying initial damage and subsequent earthquake intensity measures as core influencing factors for structural cumulative damage. These data-driven methods provide new paradigms for structural performance evaluation, though their combination with steel joint hysteretic behavior research is still in its infancy.

Recent studies on corrugated web components have laid a foundation for beam–column joint design but lack direct validation in joint-level seismic scenarios. Lee et al. [21] investigated partially corrugated web (PCW) beams and confirmed that their shear strength and deformation capacity are 15–20% higher than those of conventional flat web beams while maintaining equivalent bending capacity. The failure mode of PCW beams transitions from local buckling at corrugation boundaries to global buckling, which provides insights for designing corrugated web weakening zones in joints. Zirakian et al. [22] studied corrugated web steel coupling beams under cyclic loading and found that trapezoidal and curved corrugations improve rotation capacity by 20–30% compared to stiffened flat webs. However, this research focuses on coupling beams and ignores the coordination of plastic hinges between beams and columns in beam–column joints. Elamary et al. [23] analyzed trapezoidally corrugated web beams under different load positions and proposed a modified moment resistance formula for horizontal fold loading, which clarifies the interaction between flanges and webs but fails to extend this mechanism to joint-level ductility control. Mansouri et al. [11] developed curved and hexagonal cell corrugated web RBS joints and proved that these joints can guide plastic hinges away from column faces, yet they did not quantify the folding effect of corrugated webs on flexural capacity partitioning—a parameter that refers to the ratio of flange contribution to web contribution in bending resistance. Pang et al. [13] studied double corrugated web beams and identified the “accordion effect” of corrugated webs and shear lag in flanges, both of which are key factors affecting joint ductility, but the application of these findings to beam–column joint design remains unaddressed. Li Shen et al. [24] designed corrugated web replaceable shear links: the corrugated structure boosts energy dissipation by 35–40%, and post-earthquake function can be restored by simply replacing the links, which drastically shortens repair time. This research provides a reference for the energy-dissipating mechanism of corrugated webs in joint design. Although existing research covers multiple dimensions such as the mechanics of corrugated web beams, the ductility of high-strength steel joints, and energy dissipation components based on corrugated webs, it has only formed a preliminary “material-structure-performance” research chain for corrugated web-related steel structures. Three core gaps still remain: first, the synergy mechanism between the folding effect of corrugated webs and the outward movement of plastic hinges in beam–column joints is unclear, which makes it difficult to simultaneously achieve weld protection through reducing weld strain and stable energy dissipation; second, design criteria for corrugated web weakened beam–column joints lack quantification of the folding effect—for example, how to neglect the bending contribution of webs and fully rely on flanges for flexural resistance—which leads to disjointed logic between component-level research and joint-level application; third, the coupling of corrugated web’s out-of-plane stiffness and joint ductility is insufficiently studied, and this inadequacy fails to meet the anti-torsion and anti-buckling requirements of high-seismic-intensity areas. To address these gaps, this study proposes a new beam–column joint with locally weakened corrugated webs, integrates core achievements of corrugated web energy dissipation and plastic hinge position control, verifies the feasibility of plastic hinge outward movement through low-cycle reciprocating loading tests, and clarifies the synergistic energy dissipation mechanism between corrugated webs and flanges. This research provides a new joint design scheme for modern ductile steel frames.

2. Experimental Preparation

To investigate the failure mode, yield load, ultimate load, stress distribution law at key positions, ductility performance, and formation and development process of plastic hinges of corrugated web weakened beam–column joints under cyclic loading, and to provide valid verification data for subsequent finite element simulation calculations, two specimens—namely a locally corrugated web weakened beam–column joint specimen (SPA) and a traditional flat web joint specimen (SPF)—were designed, fabricated, and tested under low-cycle cyclic loading.

2.1. Material Property Tests

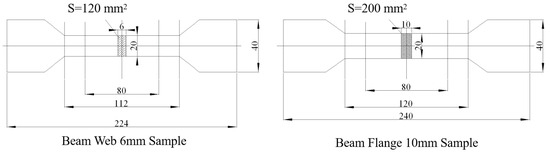

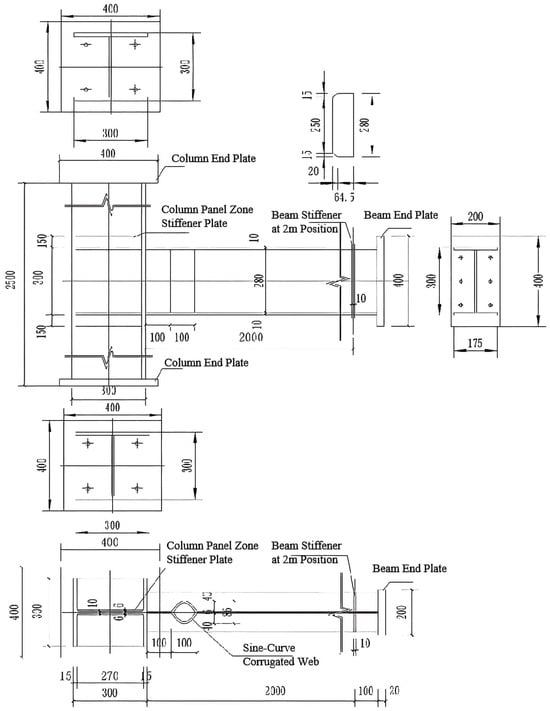

The material property tests for the steel plates were unidirectional tensile tests. The column of the specimens adopted HW300 mm × 300 mm × 10 mm × 15 mm from China’s steel section library; the beam flanges were 175 mm × 10 mm, and the beam webs were 280 mm × 6 mm. The steel grade used was Q235. Before the hysteretic tests, the material properties of the steel were obtained through tensile tests on standard specimens, whose geometric dimensions were determined in accordance with the National Standard of the People’s Republic of China Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing at Room Temperature [25].

The dimensions of the specimens for the mechanical property tests of the beam and column materials are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Samples were cut from the webs and flanges of the beam and column; one set of tensile specimens was prepared for each plate thickness, resulting in a total of four sets with two specimens per set. Figure 3 shows the test setup for the tensile specimens, and the obtained material properties are listed in Table 1—where the values represent the average of the test results from the two tensile specimens in each set. It can be seen from the data in the table that the ultimate tensile strength of the steel is much higher than its yield strength, which is mainly due to varying degrees of work hardening of the steel during the tensile process.

Figure 1.

Sampling for mechanical property test of beam specimens.

Figure 2.

Sampling for mechanical property test of column specimens.

Figure 3.

Test setup for tensile specimens.

Table 1.

Material properties of steel.

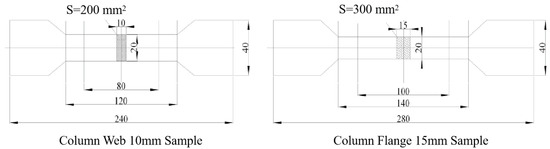

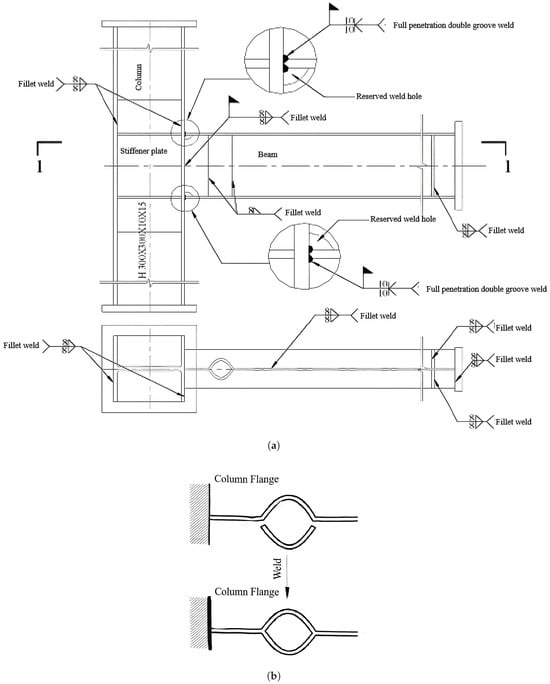

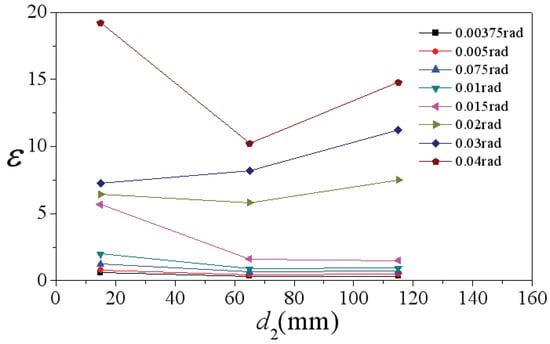

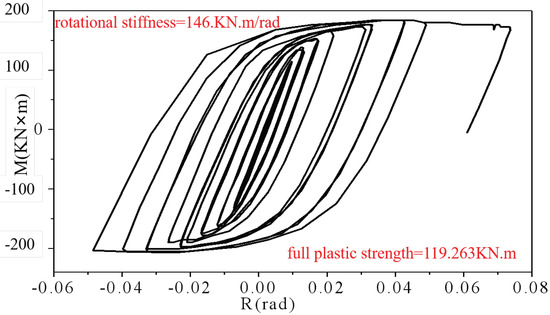

Specimen Design

The structural drawing and construction drawing of the I-beam beam–column joint with a locally weakened corrugated web are shown in Figure 4. Due to the folding effect, the corrugated web does not resist bending, so the bending moment in this region can be considered entirely borne by the flanges. As a result, a so-called weakened section is formed, and the corrugated web in the weakened region can provide sufficient shear capacity. In this new type of beam–column joint, the presence of the corrugated web provides the region with relatively high out-of-plane stiffness, preventing out-of-plane torsion after the formation of plastic hinges and improving the stability of the web.

Figure 4.

Corrugated web weakened joint. (a) Structural drawing; (b) web type; (c) joint construction drawing.

2.2. Specimen Tests

2.2.1. Specimen Design

To investigate the seismic performance of the corrugated web weakened beam–column joint shown in Figure 4 and compare it with that of the traditional beam–column joint, comparative low-cycle cyclic tests were conducted on two specimens of the same size: one with a locally corrugated web weakened beam–column joint (SPA) and the other with a traditional flat web beam–column joint (SPF).

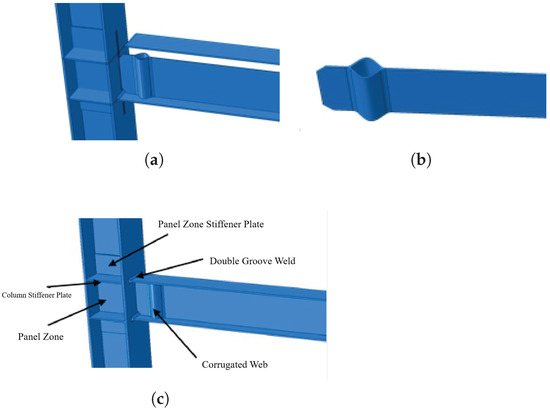

Figure 5 shows the schematic diagram of the geometric dimensions of the rigid beam–column joint formed by welding an I-beam with a local corrugated web and an I-section column used in the test. Both the beam and column in the test were made of Q235 steel. The column was a steel section with a height of 2.5 m and a cross-sectional dimension of HW300 mm × 300 mm × 10 mm × 15 mm; the beam was a composite beam with a length of 2 m, flanges of 175 mm × 10 mm, and a web of 280 mm × 6 mm. These dimensions meet the requirements for the width-thickness ratio of plates specified in the Code for Design of Steel Structures [26].

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the geometric dimensions of the joint specimen (SPA).

During specimen fabrication, the beam flanges and column flanges were connected using full-penetration double-groove welds, and all other connections used fillet welds. To prevent shear failure in the joint panel zone, additional welding plates were attached to the column panel zone; the dimensions of these plates were designed with reference to the Technical Specification for Steel Structures of Tall Buildings [27]. The detailed fabrication drawings of the specimens are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Detailed fabrication drawing of the joint specimen (SPA). (a) Detailed fabrication drawing of the specimen; (b) schematic diagram of corrugated web connection.

2.2.2. Loading Equipment and Loading Protocol

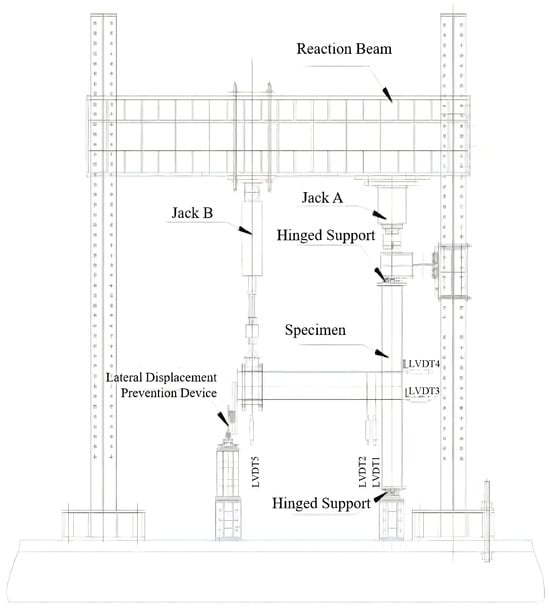

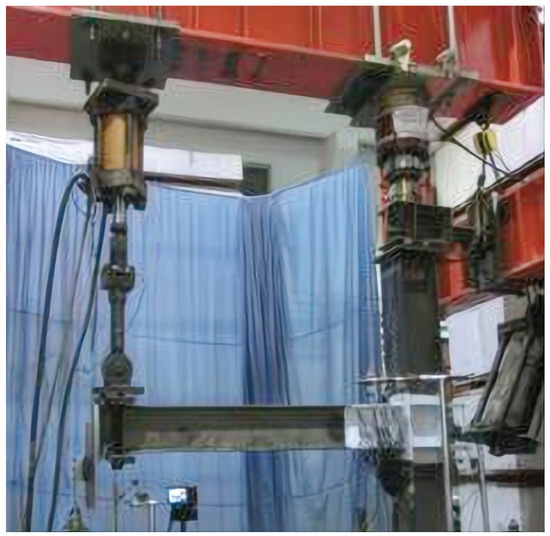

The test used the electro-hydraulic servo loading system of the Structural Laboratory of Yantai University to apply unidirectional axial load at the column end and cyclic load at the beam end.

During the test, the specimen was fixed on a reaction frame, and simply supported boundary conditions were set at both ends of the column to allow rotation but restrict horizontal displacement of the column ends. A hydraulic jack A with a range of 300 t was placed at the column top, applying an axial pressure of 764 kN to the column—equivalent to 30% of the full-section yield pressure of the column. At the position of the I-beam 2 m away from the column flange, the steel beam was connected to the actuator base plate of the double-ball hinge linkage loader (jack B) using bolts to apply cyclic load, with a load range of ±50 t and a stroke of ±200 mm. The test loading equipment is shown in Figure 7, and the beam-end guiding lateral displacement prevention device is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

Test equipment setup.

Figure 8.

Beam-end guiding lateral displacement prevention device.

To prevent out-of-plane torsion of the beam during the test, a gapless active guiding lateral displacement prevention device was installed at the beam end. An end plate was welded to the beam end of the specimen and connected to two sets of vertical guide-rail slider pairs via bolts—this retained the vertical degree of freedom of the beam end and allowed vertical movement while restricting out-of-plane lateral movement. The lower end of the guide-rail slider pairs was connected to a rotational pair bearing to retain the in-plane rotational degree of freedom of the beam end. Two sets of horizontal guide-rail slider pairs were connected below the bearing to retain the horizontal degree of freedom of the beam end and allow horizontal movement. In summary, the guiding lateral displacement prevention device retains three degrees of freedom of the beam end (horizontal, vertical, and rotational) while restricting the other three out-of-plane degrees of freedom, achieving a guiding effect and theoretically preventing lateral displacement.

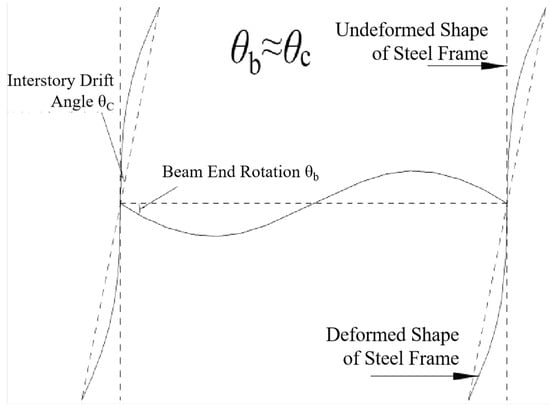

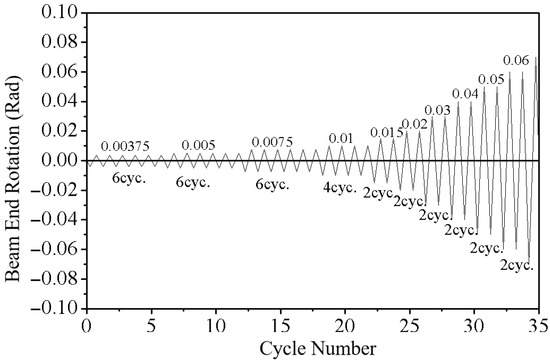

Currently, three types of quasi-static loading rules are commonly used in tests: displacement-controlled loading, force-controlled loading, and force–displacement hybrid-controlled loading. Referring to the AISC Seismic Provisions for Structural Steel Buildings [28], this test adopted a variable-amplitude displacement-controlled loading method, with the inter-story drift angle as the index to control loading. During the test, the rotation angle at the joint was used instead of the inter-story drift angle , as shown in Figure 9. The loading protocol is presented in Table 2 and Figure 10. To better monitor the deformation and response of the specimen during loading, the test loading rate was controlled at approximately one cycle step every 3 min, and each specimen took about 1.5 h from the start of loading to the end of the test. Photos of the test loading process are shown in Figure 11 and Figure 12.

Figure 9.

Inter-story drift angle schematic diagram.

Table 2.

Loading protocol parameters.

Figure 10.

Test loading protocol.

Figure 11.

Loading photo of the corrugated web weakened joint.

Figure 12.

Loading photo of the flat web joint.

During the test, displacement transducers and strain gauges were arranged on each specimen. A total of five displacement transducers were used in this test. Displacement Transducer 1 and Displacement Transducer 2 were used to measure the vertical displacements at the start and end positions of the corrugated web, and the obtained data could be used to calculate the rotation angle of the plastic hinge region. Displacement Transducer 3 and Displacement Transducer 4 were used to measure the horizontal displacements at the upper and lower stiffeners of the joint panel zone, and the obtained data could be used to calculate the rotation angle of the joint panel zone. Displacement Transducer 5 was arranged directly below the beam-end loader to record the vertical displacement of the beam end during the loading process, and the obtained data could be used to calculate the rotation angle of the entire beam. The arrangement of the displacement transducers is shown in Figure 7.

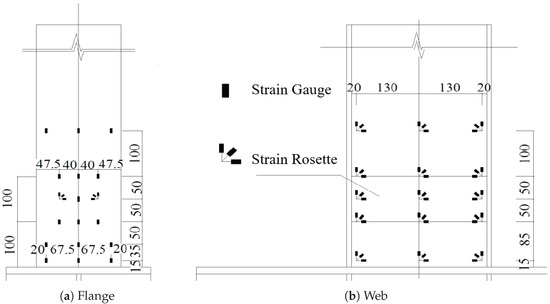

In this test, strain gauges were also arranged on the beam flanges, beam web, corrugated web, and column flanges to record the strain changes of the specimens during the test. The arrangement scheme of strain gauges and strain rosettes on the beam web and flanges is shown in Figure 13. Two strain gauges were arranged, respectively, at the upper and lower parts of the column flange near the end plate to monitor the vertical deformation of the column and ensure accurate loading control.

Figure 13.

Arrangement of strain gauges and strain rosettes on the I-beam (Unit: mm).

3. Test Results

3.1. Low-Cycle Reciprocating Loading

By observing test phenomena and analyzing the measured data obtained from the tests, the hysteretic performance and ductility performance of the two joint specimens in this test were investigated. Under low-cycle reciprocating loading, the locally corrugated web beam–column joint exhibited good ductility performance. It went through the elastic stage, the formation and development stage of plastic hinges in the corrugated web region of the beam, and after the joint specimen reached the ultimate bearing capacity, its ductility continued to develop until the local buckling failure of the component. The failure process and failure state of each joint are described separately below.

3.1.1. Specimen SPA

This is a fully welded joint with a locally corrugated web beam. At the initial stage of loading, the entire cross-section of the beam was in the elastic state, and the beam-end load increased approximately linearly in proportion to the beam-end rotation angle. When the beam-end rotation angle reached 0.015 rad, the flange of the beam end near the column root and the flange at the center of the corrugated web weakened region almost reached yielding simultaneously. The strain at the center of the corrugated web weakened region was slightly larger than that at the beam end, and fine micro-cracks appeared in the paint on the corrugated web weakened region of the beam flange.

With the increase in load amplitude, the strain growth rate at the center of the corrugated web weakened region was much higher than that at the beam end. When the beam-end rotation angle reached 0.02 rad, the paint cracks in the corrugated web weakened region of the beam flange expanded, and the yielding phenomenon became more obvious. When the beam-end rotation angle reached 0.03 rad, the entire corrugated web weakened region began to yield, but no obvious buckling phenomenon was observed in either the corrugated web weakened region or other regions.

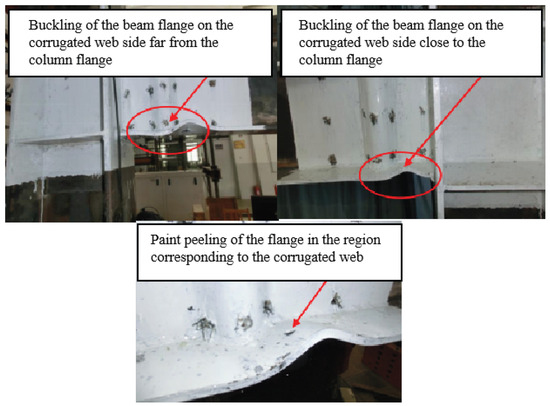

During the second cycle when the beam-end rotation angle reached 0.04 rad, the yielding of the beam flange began to expand from the corrugated web weakened region to both sides of this region. At this time, due to the buckling of the corrugated web, slight buckling occurred on both sides of the corrugated web on the beam. When the beam-end rotation angle reached 0.05 rad, the yielding at the wave crest of the sinusoidal corrugated web continued to expand along the depth and length directions of the beam, and the degree of buckling on both sides of the corrugated web on the beam increased. As the load decreased, the buckling disappeared accordingly, forming an obvious plastic hinge. Moreover, due to the supporting effect of the corrugated web after the flange buckled, no severe bulging phenomenon occurred. In addition, there was no outward bending or torsion of the beam at the corrugated web. This is shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Failure diagram of the corrugated web steel I-beam–column joint.

After the beam-end rotation angle reached 0.05 rad, the initial loading position of the double-ball hinge linkage loader at the beam end was not at the zero position—meaning it had reached the ultimate loading displacement in one direction—so the test was stopped after unidirectional loading to 160 mm.

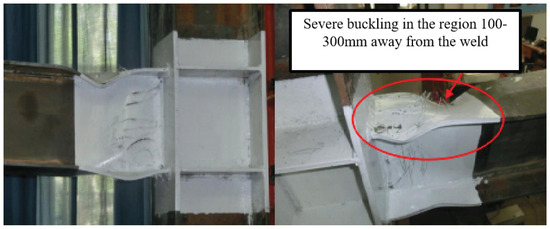

3.1.2. Specimen SPF

This is a conventional fully welded component. Due to the strengthening of the beam–column flange connection weld during processing, the joint weld did not fail during the test, but the plastic deformation was large, the plastic hinge region was excessively large, and the rotational capacity was poor, as shown in Figure 15. Furthermore, after the flange yielded, it bulged outward severely due to compression, resulting in a significant decrease in bearing capacity. In addition, the web bent, twisted, and bulged outward at the plastic hinge.

Figure 15.

Failure diagram of the flat web joint.

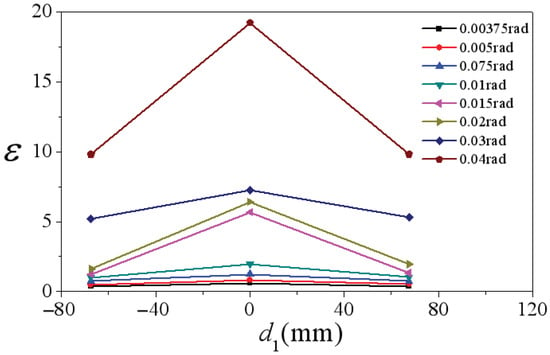

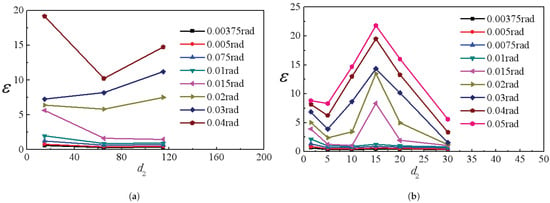

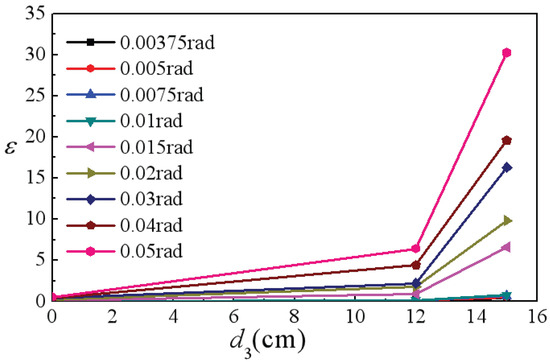

During the loading process, when the beam-end rotation angle reached 0.01 rad, slight peeling appeared in the paint at the center of the beam flange weld, indicating that yielding began at this position. From the strain values collected by the strain gauges, it can be found that before the beam-end rotation angle reached 0.02 rad, the strain value of the beam-end flange weld was always the largest, as shown in Figure 16 and Figure 17. In these figures, denotes normalized strain, denotes the distance measured from the beam center, and denotes the distance measured from the column flange. The design method of and is presented in Figure 18. After the beam-end rotation angle reached 0.02 rad, significant buckling occurred in the beam flange and web within the range of 100–300 mm from the beam–column flange weld on the beam, resulting in large plastic deformation. Therefore, the strain change no longer showed a trend of gradually decreasing from the weld to the beam end. With the increase in load, the buckling deformation became more obvious, and when the load decreased, the buckling could not completely disappear, forming permanent plastic deformation—meaning no obvious plastic hinge was formed. After the beam-end rotation angle reached 0.04 rad, the beam-end load decreased significantly, the flange buckled severely, and the web bulged seriously. At this point, the component can be considered to have lost its bearing capacity, and the test was stopped.

Figure 16.

Strain variation along the weld centerline of the SPF joint.

Figure 17.

Strain variation along the beam flange centerline.

Figure 18.

Three-dimensional diagram of and .

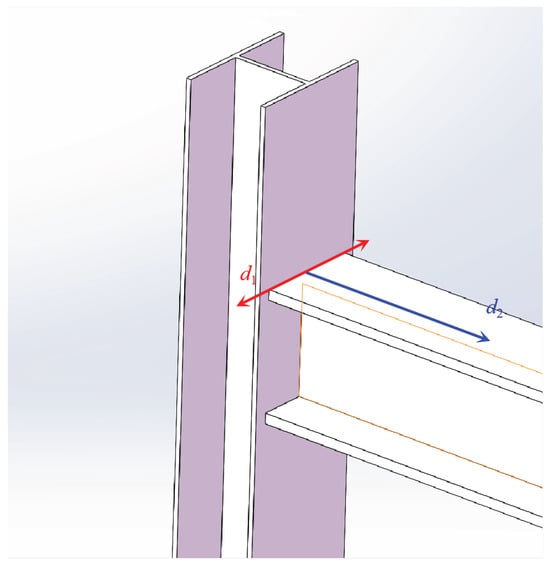

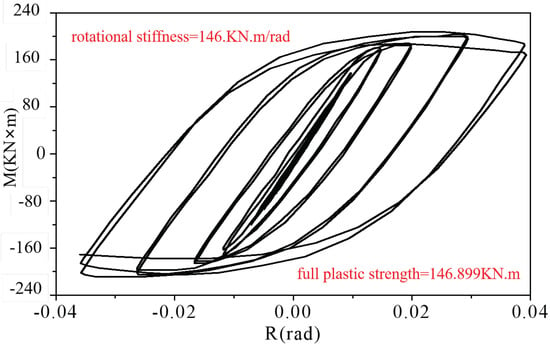

3.2. P- Hysteretic Curves

In this study, the relationship between the beam-end rotation angle R and the corresponding beam-end load P is defined as the hysteretic curve of the joint. Figure 19 and Figure 20 show the hysteretic curves of the locally corrugated web beam–column joint and the traditional flat web joint, respectively.

Figure 19.

Hysteretic curve of the locally corrugated web beam–column joint.

Figure 20.

Hysteretic curve of the conventional flat web joint.

As can be seen from Figure 19, for the locally corrugated web weakened beam–column joint, the hysteretic loops are stable and full when the inter-story drift angle is within 0.05 rad. No obvious load decrease was observed during the test. The maximum positive bending moment and maximum negative bending moment at the column flange at the beam root were 183.89 kN·m and 205.13 kN·m, respectively, and the strength reduction was very small compared with the flat web joint. When the inter-story drift angle reached 0.04 rad in the second cycle, slight buckling occurred on both sides of the corrugated web at the web of the beam, but this did not cause a significant decrease in load. With the further increase in loading displacement, the load decreased slightly, but the load decrease was much smaller than that of the flat web joint. From the above analysis, it can be concluded that the presence of the local corrugated web on the beam delays the local buckling of the beam and reduces the degree of beam buckling.

As can be seen from Figure 20, for the traditional flat web joint, the hysteretic loops of the joint are full and stable before the inter-story drift angle reaches 0.03 rad. The maximum bending moment at the column flange at the beam root was 208.98 kN·m. With the gradual increase in loading displacement, the beam-end load decreased gradually due to the severe buckling of the beam flange and web. Compared with the hysteretic curve of the locally corrugated web beam–column joint, this hysteretic curve is flatter and less full, with a smaller hysteretic loop area.

In summary, compared with the traditional beam–column joint, the corrugated web weakened joint can form a wider plastic region at the designed position away from the column flange, develop plastic deformation well, and form a plastic hinge with strong rotational capacity. This effectively protects the beam–column weld connection and avoids its premature failure. Moreover, the local stability of the flange and web at the plastic hinge is better. Therefore, in terms of failure mode, the corrugated web weakened beam–column joint has better seismic performance, which is conducive to realizing the concept of “strong joint and weak member” in seismic design.

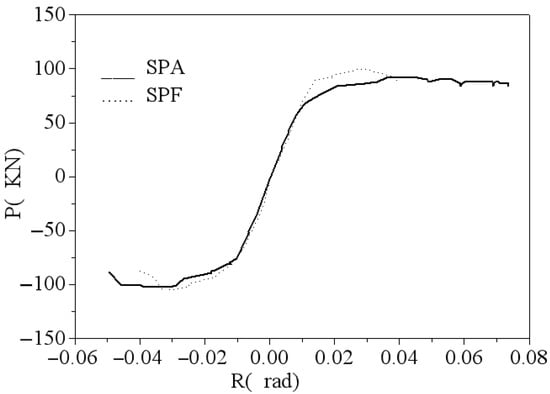

3.3. Skeleton Curves

In the hysteretic curve obtained from the cyclic loading test, the point with the maximum load and displacement values on each hysteretic loop is called the “peak point”. The curve connecting the peak points of each cyclic loading on the hysteretic curve is called the “skeleton curve”. The skeleton curves of the two rigid joints of the steel frame in this study are shown in Figure 21.

Figure 21.

Skeleton curves of each specimen.

As can be seen from the skeleton curves of the two joints in Figure 21, before yielding of the steel beam, the load changes linearly with displacement for both specimens, and the stiffness of the two specimens is basically the same. This indicates that the local use of corrugated web at the beam end designed in this study has little effect on reducing the beam stiffness. After the yielding stage, the load increment shows an obvious nonlinear relationship with the increase in beam-end displacement. It can also be seen from the figure that even though the beam–column joint weld was strengthened during the specimen fabrication in this test, and the flange was severely buckled and the web was severely twisted within the range of 100–300 mm near the column flange of the beam, the descending segment of the skeleton curve of the traditional flat web joint is still short after reaching the maximum bearing capacity.

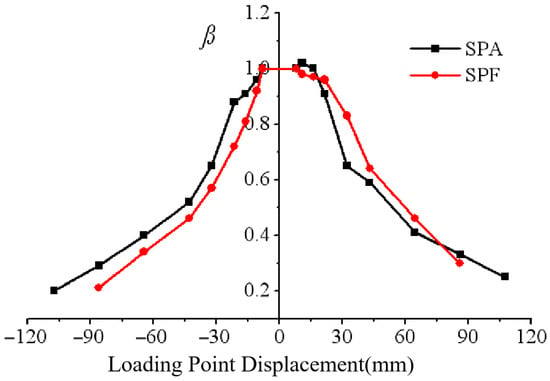

3.4. Stiffness Degradation

The slope of the line connecting each point on the skeleton curve to the origin represents the deformation degree of the component at each stage, which is called “secant stiffness”. Obviously, after entering the yielding stage, the secant stiffness of the specimen continuously decreases—meaning the component stiffness degrades as deformation increases. The degree of this degradation can be expressed by the stiffness degradation coefficient . The stiffness degradation coefficient is defined as the ratio of the secant stiffness at each deformation stage to the initial elastic stiffness. The secant stiffness of the components calculated from the test results is listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Various joint performances obtained from tests.

As shown in Figure 22, the stiffness degradation trends of the two specimens are generally consistent. Within the loading displacement of 20 mm, which corresponds to an inter-story drift angle of 0.01 rad, the stiffness of the specimens shows almost no change. When the displacement exceeds this value, the specimen stiffness degrades significantly, showing a trend of rapid degradation in the early stage and slowed degradation in the later stage. The degradation laws in the positive and negative directions are basically consistent.

Figure 22.

Stiffness degradation curves of each specimen.

The main reason for stiffness degradation is the reduction in cross-sectional flexural stiffness caused by the yielding to local buckling of the beam flange. The traditional flat web joint specimen exhibits faster stiffness degradation than the locally corrugated web beam–column joint. This is because the supporting effect of the corrugated web delays the local buckling of the beam and reduces the degree of beam local buckling, allowing the plastic deformation of the beam flange to be more fully developed. In contrast, the flat web joint suffers from severe local buckling and bending–torsional instability due to the small out-of-plane stiffness of the flat web, leading to greater stiffness degradation.

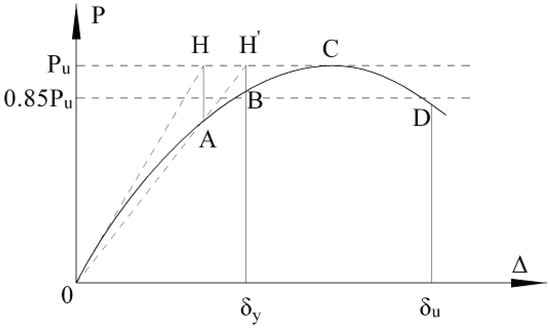

The yield displacement, yield load, ultimate displacement, and ultimate load of the specimens can be obtained from the skeleton curve shown in Figure 21. In this study, the peak load is used instead of the ultimate load for analysis. The yield displacement of the specimens can be determined using the “general yield moment method”, as illustrated in Figure 23. First, draw a tangent line to the elastic stage through the origin O; this line intersects the horizontal line passing through the ultimate load point C at point H. Then, draw a vertical line from H to intersect the skeleton curve at point A; connect points O and A, extend the line , and intersect it with line at point D. Finally, draw a vertical line from point D to intersect the skeleton curve at point B. Point B is the yield point of the specimen, and the corresponding displacement is the yield displacement of the specimen.

Figure 23.

Schematic diagram for calculating equivalent yield displacement.

Ductility is an important indicator for evaluating the seismic performance of structures or components. The greater the ductility of a structure, the stronger its ability to resist large deformations during major earthquakes. The ductility of a specimen can be measured by the ductility coefficient , and the calculation formula for is as follows:

where = ultimate displacement, referring to the displacement when the component fails or the displacement corresponding to the ultimate bearing capacity decreasing to 85% on the skeleton curve, and = yield displacement of the specimen.

3.5. Energy Dissipation and Equivalent Viscous Damping Coefficient

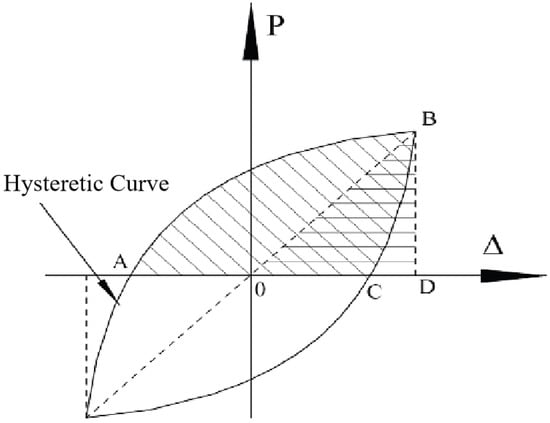

Energy dissipation capacity is an important indicator for evaluating the seismic performance of structures. The energy dissipation capacity of actual structures is generally represented by the equivalent viscous damping coefficient . As shown in Figure 24, can be calculated using the area enclosed by the measured structural hysteretic curve and the horizontal axis, and the area of . The specific formula is given in Equation (2), and the equivalent viscous damping coefficients of the specimens are listed in Table 4.

Figure 24.

Schematic diagram for calculating equivalent viscous damping coefficient.

Table 4.

Equivalent viscous damping coefficients.

3.6. Stress Transfer Analysis

Figure 25a,b show the strain distributions of the two specimens along the beam length direction, respectively. Comparison reveals the following: Theoretically, the stress at the weld of the flat web joint is the highest. As shown in Figure 25a, when the inter-story drift angle reaches 0.02 rad and 0.03 rad, significant buckling occurs in the beam flange and web within the range of 100–300 mm from the weld on the beam, resulting in large plastic deformation. Thus, the strain distribution no longer shows a trend of gradually decreasing from the weld to the beam end.

Figure 25.

Strain variation along the beam flange centerline. (a) Strain variation along the centerline of the flat web joint beam flange. (b) Strain variation along the centerline of the locally corrugated web beam–column joint beam flange.

As shown in Figure 25b, the maximum strain on the flange first appears near the weld and in the corrugated web region, then gradually expands toward the column flange and beam end. The strain growth rate in the corrugated web region of the beam flange is faster than that at the joint weld. During subsequent loading cycles, the strain in this region remains the highest, and it yields first. Subsequently, two buckling points are formed on each of the upper and lower flanges; as the load decreases, the buckling disappears, forming a stable and effective plastic hinge. This achieves a reliable energy dissipation mechanism and realizes the goal of outward movement of the plastic hinge.

The axial strain distribution along the beam cross-sectional height at the center of the corrugated web region is shown in Figure 26, where denotes normalized strain and denotes the distance measured from the center of the beam web. This figure only presents the strain distribution from the web center to the upper beam flange; the axial strain distribution from the corrugated web center to the lower flange can be considered symmetric to this figure.

Figure 26.

Axial strain distribution along the beam height in the corrugated web region.

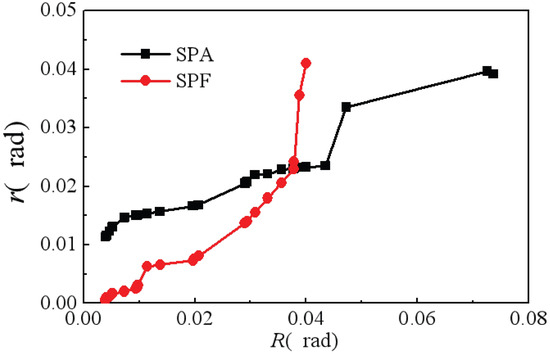

The comparison of the rotation angles of the corrugated segments between the flat web joint and the locally corrugated web beam–column joint is shown in Figure 27. Here, r denotes the rotation angle of the corrugated web region on the beam, R denotes the beam-end rotation angle, SPA refers to the locally corrugated web beam–column joint, and SPF refers to the flat web joint.

Figure 27.

Rotation angle comparison of corrugated segments between the two specimens.

4. Discussion

Low-cycle reciprocating loading tests were conducted on the traditional flat web joint and the new locally corrugated web weakened beam–column joint proposed in this study. A constant force applied at the top of the column simulated the vertical load of the frame structure, while vertical cyclic loading at the beam end simulated seismic action. With reference to the AISC Seismic Provisions, the test loading method used the beam-end rotation angle instead of the inter-story drift angle as the displacement control index, and a loading protocol was developed. The failure mode of the joint, formation and development of the plastic hinge, hysteretic curve, skeleton curve, stiffness degradation, ductility, equivalent viscous damping coefficient, and stress distribution at key positions were analyzed in detail. Based on the test results and analysis, the following conclusions are drawn:

- When designing the locally corrugated web weakened joint, three weakening parameters of the corrugated web should be reasonably selected according to the actual bending moment distribution—i.e., the distance a from the starting point of the corrugated web to the column flange, the wavelength b of the corrugated web, and the wave depth c of the corrugated web. Meanwhile, factors such as steel overstrength and strain hardening should be considered. The ratio of the column surface bending moment to the full-section plastic resistance moment of the beam should be within the range of 0.85–1.0.

- The new joint in this study can reduce the plastic strain near the welds and effectively concentrate the plastic strain in the corrugated web weakened region. Therefore, no brittle fracture occurred in areas other than the plastic hinge during the test.

- Analysis of the test results verifies the folding effect of the corrugated web in this new joint. Neglecting the contribution of the web to the beam’s flexural resistance, the flexural capacity of the plastic hinge region is borne solely by the flanges.

- The presence of the corrugated web delays flange buckling and reduces the degree of beam buckling, resulting in relatively stable and reliable energy dissipation performance and seismic performance. The hysteretic curve of the new joint is stable and full without pinching, and it has good ductility. During the plastic development stage, the load decreases slowly with the increase in loading displacement, showing no severe stiffness degradation. In contrast, the hysteretic curve of the traditional flat web joint is flatter and less full; during the plastic development stage, the load decreases significantly with the increase in loading displacement, accompanied by obvious stiffness degradation.

- Both beam and column members in the experiment were made of Q235 steel. According to the Code for Welding of Steel Structures (GB 50661-2011 [29]), the matching electrode model for Q235 steel should be E43. However, considering that welds of traditional joints are prone to premature brittle failure, this study intentionally used E50 electrodes (with a higher strength grade than the base metal matching requirement). The increased weld strength grade was to make up for potential brittle defects of welds, ensuring welds would not fail first when the beam undergoes plastic deformation.

For weld quality control, in addition to strictly following the welding processes of full-penetration double-groove welding (beam–column flange connections) and fillet welding (other secondary connections), quality inspection was conducted through visual inspection (checking weld formation and eliminating defects like pores, inclusions, or incomplete penetration) and weld dimension verification (ensuring groove depth and fillet height meet design drawings). Due to experimental conditions, ultrasonic flaw detection was not carried out; however, the high-strength matching design of E50 electrodes and strict welding process control were verified in subsequent low-cycle reciprocating loading experiments—no weld cracking or deformation failure occurred, and only the beam suffered strength failure in the corrugated web weakened area and formed a stable plastic hinge, conforming to the “strong weld-weak member” design expectation.

In this study, due to the strengthening of the beam–column connection welds, no cracks formed at the welds of the traditional flat web joint, and no brittle fracture occurred during the test. However, severe local buckling occurred within the range of 100–300 mm from the column flange, and the web suffered severe out-of-plane torsion. Although a plastic hinge formed on the beam, the buckling did not recover when the load decreased. For the new locally corrugated web joint proposed in this study, a stable and effective plastic hinge formed at the designed position on the beam—i.e., the corrugated web weakened region. When the load decreased, the flange buckling recovered. Owing to the supporting effect of the corrugated web, the width-thickness ratio of the beam flange in the corrugated web region is smaller, so the flange buckling is significantly less than that of the traditional flat web joint, and the position of the plastic hinge is clear. In addition, the corrugated web has high out-of-plane stiffness, which effectively controls the out-of-plane torsional failure of the beam.

5. Conclusions and Prospects

This study proposes a novel locally corrugated web weakened beam–column joint, which replaces the flat web in key energy-dissipating regions of traditional joints with trapezoidal corrugated webs. The core design concept is to utilize the superior out-of-plane stiffness and geometric characteristics of corrugated webs to optimize the plastic hinge distribution, enhance seismic performance, and simplify post-earthquake maintenance. To verify the mechanical behavior of the proposed joint, quasi-static tests were conducted on two fully welded T-shaped steel frame beam–column joints, and corresponding test data were obtained. One specimen was the new locally corrugated web weakened beam–column joint proposed in this study, and the other was a traditional flat web joint used as a reference. During the test, a constant load with an axial compression ratio of 0.3 was applied at the top of the column, and vertical cyclic loading was applied at the beam end. Based on the above tests and systematic analysis, the conclusions are drawn as follows:

- (1)

- The test shows that the new joint specimen exhibits buckling failure of the beam flanges on both sides of the corrugated web. The locally corrugated web joint effectively reduces the plastic strain at the beam–column connection welds—test results indicate that the maximum plastic strain at the welds of the new joint is only 38% of that of the traditional joint—and concentrates the plastic strain in the corrugated web weakened region. During the test, the plastic hinge stably formed in the corrugated web region, and no brittle fracture occurred at the beam–column connection welds, thereby effectively protecting the joint connection welds. For the traditional beam–column joint, the beam–column connection welds were strengthened during processing, so no failure occurred during the test. However, its plastic hinge was located within 150 mm of the beam end (close to the joint core), resulting in poor rotational capacity. Moreover, after the flange yielded, it bulged outward by up to 12 mm under compression, leading to a significant decrease in bearing capacity. In addition, the web bent and twisted outward at the plastic hinge, and the beam suffered bending–torsional buckling when the drift ratio reached 3.5%, resulting in test termination.

- (2)

- Test data processing and analysis show that the flexural capacity of the corrugated web region in the composite steel beam is mainly borne by the beam flanges. Due to the folding effect of the corrugated web, the contribution of the web to flexural resistance can be neglected.

- (3)

- The test indicates that the presence of the corrugated web delays flange buckling—the buckling of the new joint’s beam flanges occurs at a drift ratio of 4.2%, which is 37.5% higher than that of the traditional joint (3.0%)—and reduces the degree of beam buckling. This results in a relatively stable and reliable energy dissipation mechanism, ultimately improving the overall seismic performance of the joint.

- (4)

- Test data processing and analysis reveal that a stable and reliable plastic hinge first forms in the corrugated web region of the composite steel beam, 200–250 mm away from the joint core. The plastic rotation of the joint is mainly provided by this plastic hinge, while the plastic rotation of the joint panel zone accounts for less than 10% of the total rotation, achieving the goal of outward movement of the plastic hinge. This design effectively protects the joint panel zone (with poor ductility) and the beam–column connection welds, avoiding brittle failure of key load-bearing components. Due to the load-bearing capacity limitation of the test reaction frame, the test was stopped when the rotation angle of the new joint reached 5% rad—this value meets the rotation angle requirement (less than 4%) for steel frame joints in high-seismic-intensity areas (8 degrees and above) specified in GB 50011-2010 [30]. The stable mechanical performance before the test termination also confirms the new joint’s excellent ductility and deformation capacity.

- (5)

- The test shows that the hysteretic curve of the new joint is full and spindle-shaped, with no obvious pinching phenomenon. In contrast, the hysteretic curve of the traditional flat web joint is flatter and exhibits slight pinching after the drift ratio exceeds 2%. Energy dissipation and equivalent viscous damping coefficient were calculated based on the hysteretic curves. The results show that at a drift ratio of 4%, the cumulative energy dissipation of the new joint reaches 128.6 kN·m, which is 42.3% higher than that of the traditional joint (89.7 kN·m); the equivalent viscous damping coefficient of the new joint is 0.32, while that of the traditional joint is 0.21. The new joint has good energy dissipation capacity, and both its energy dissipation capacity and equivalent viscous damping coefficient are significantly higher than those of the traditional flat web joint (the reference specimen). Plastic deformation of the corrugated web region is the main energy dissipation mechanism of the new joint, which is more stable and reliable than the energy dissipation mechanism of the flat web joint (dominated by flange and web buckling). During the entire test process, the new joint did not experience severe out-of-plane instability in the plastic hinge region (i.e., severe bulging of the beam web) or severe stiffness degradation—its stiffness degradation rate at a drift ratio of 5% was only 28%, much lower than 45% of the traditional joint.

Through experimental testing of the T-shaped steel frame joint with a locally corrugated web, a preliminary study was conducted on the hysteretic performance of such joints under constant force at the column end and vertical cyclic loading at the beam end, and certain achievements were obtained. However, due to the limitations of the authors’ capabilities and time, only one type of joint was studied, which is far from sufficient. Therefore, further research can be carried out in the following aspects:

- (1)

- Study the hysteretic performance of different joint types, such as cruciform joints under in-plane or out-of-plane cyclic loading at the beam end or column end.

- (2)

- The beams in this study are all shallow beams, which may not be applicable to deep beams that are increasingly used nowadays. Therefore, future research should focus on the performance of joints with different beam–column cross-sectional shapes and the influence of different corrugated web forms on joint performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.; methodology, W.W.; software, W.A.; validation, W.W., A.S. and S.Z.; formal analysis, Y.S.; investigation, W.W. and W.A.; resources, A.S.; data curation, S.Z. and Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, W.W.; writing—review and editing, A.S.; visualization, W.A.; supervision, A.S.; project administration, A.S.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Central Government Guided Local Fund Project, Grant No. YDZX2025057. The APC was funded by the same project.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study, and thus no additional data are available for public release.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Renjie Liu for their valuable suggestions during the study.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Wei Ao and Yanan Sun were employed by the company China Construction Third Engineering Bureau Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Muguruma, H.; Nishiyama, M.; Watanabe, F. Lessons learned from the kobe earthquake–a japanese perspective. PCI J. 1995, 40, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahin, S.A. Lessons from damage to steel buildings during the northridge earthquake. Eng. Struct. 1998, 20, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansi, O.Z.Y.; Lu, L.F.; AL-Saeedi, S.M.A.A.; Liu, B.Y. Effects of cover-plate geometry on the mechanical behavior of steel frame joints with middle-flange and wide-flange h-beams. Buildings 2025, 15, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanpour, A.; Torabian, S.; Mirghaderi, S.R. Seismic design of the double-cell accordion-web reduced beam section connection. Eng. Struct. 2019, 191, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C.F.; Sun, G.H.; He, R.Q.; Tang, D.; Jiang, S. Seismic performance test of steel frame substructures with cover-plate strengthened joints. J. Build. Struct. 2015, 36, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, G.S. Calculation of cover-plate strengthened beam-column joints. Steel Constr. Chin. Engl. 2024, 39, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.H.; Vu, Q.V.; Truong, V.H. Optimization of nonlinear inelastic steel frames considering panel zones. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2020, 142, 102771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.S.; Vesmawala, G. Study of steel moment connection with and without reduced beam section. Case Stud. Struct. Eng. 2014, 1, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.Y.; Xu, X.D.; Li, S.; Wu, M.L.; Wang, M.Y. Optimization analysis of shear capacity of embedded corrugated steel web connectors. J. Heilongjiang Univ. Technol. Compr. Ed. 2025, 25, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, G.; Rayegani, A.; Lavasani, H.H.; Tavakoli, L.; Nasiri, M.; Soureshjani, O.K. Seismic performance of the rbs connection with trapezoidal corrugated web (tcw-rbs). Structures 2023, 56, 105003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, A.; Shakiba, M.R.; Fereshtehpour, E. Two novel corrugated web reduced beam section connections for steel moment frames. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 103187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Chen, M.Y.; Liu, Y.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.B.; Xu, X.Q. Fatigue performance of stud connectors in joints between top slabs and steel girders with corrugated webs subjected to transverse bending moments. Eng. Struct. 2024, 310, 118132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, R.; Yuan, R.R.; Liu, S.L.; Dang, L.J.; Lei, H.B.; Lu, Y. Flexural behavior of steel beams with double corrugated webs: Experimental and analytical investigations. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 218, 113929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pasternak, H.; Robra, J.; Wang, J. Shear buckling resistance of sinusoidal corrugated web girders with stiffened openings: Analysis, experiment, simulation and design guidance. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 215, 113368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yi, Y.X.; Tian, L.M. Numerical simulation of a novel welded steel-frame joint strengthened by outer corrugated plates to prevent progressive collapse. Buildings 2025, 15, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.S.; Zhang, Y.J.; Ye, Q.X. Finite element analysis and design method of high strength steel cover-plate beam-to-column joints. Structures 2025, 79, 109634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Zhang, N.Z.; Bao, L.J.; Chen, X.M.; Zhou, F.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, H.T. Experimental study on cruciform welded connections with thick steel plates in moment-resisting beam-to-column joints. Eng. Struct. 2025, 331, 119914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.S.; Shi, G. Cyclic tests on high strength steel flange-plate beam-to-column joints. Eng. Struct. 2019, 186, 564–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.L.; Wang, Z.T.; Li, L.; Hao, H.; Chen, W.S.; Shao, Y.D. Machine learning prediction of structural dynamic responses using graph neural networks. Comput. Struct. 2023, 289, 107188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridis, P.C.; Kavvadias, I.E.; Demertzis, K.; Iliadis, L.; Vasiliadis, L.K. Interpretable Machine Learning for Assessing the Cumulative Damage of a Reinforced Concrete Frame Induced by Seismic Sequences. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-D.; Lee, S.-H.; Shin, K.-J.; Lee, J.-S. Shear strength evaluation of steel beams with partially corrugated web. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2023, 211, 108179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirakian, T.; Hajsadeghi, M.; Lim, J.B.P.; Bahrebar, M. Structural performance of corrugated web steel coupling beams. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Struct. Build. 2016, 169, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamary, A.S.; Alharthi, Y.M.; Hassanein, M.F.; Sharaky, I.A. Trapezoidally corrugated web steel beams loaded over horizontal and inclined folds. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2022, 192, 107202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiang, C.X.; Du, N.J.; Lu, J.L. Experimental study on hysteretic behavior of replaceable shear link with corrugated web. Structures 2025, 71, 108139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 228.1-2010; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing at Room Temperature. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2010.

- GB 50017-2003; Code for Design of Steel Structures. Ministry of Construction of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2003.

- JGJ 99-98; Technical Specification for Steel Structures of Tall Buildings. China Academy of Building Research: Beijing, China, 1998.

- AISC 341-00; Seismic Provisions for Structural Steel Buildings. American Institute of Steel Construction: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000.

- GB 50661-2011; Code for Welding of Steel Structures. China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

- GB 50011-2010; Code for Seismic Design of Buildings. China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).