Spatial Evolution of Narrow-Courtyard Dwellings in Guanzhong Rural Areas of Shaanxi, China, from 1949 to the Present

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Status

1.2. Research Area and Sample Source

1.3. Stage Division and Method Path

2. The Typological Evolution of the Individual Spaces in Narrow Courtyard Houses

2.1. The Space of Courtyard

2.2. The Space of Main Room

2.3. The Annex Room and Gatehouse Space

3. The Typological Evolution of the Space in the Narrow Courtyard Residential Complex

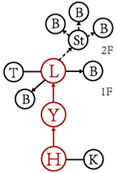

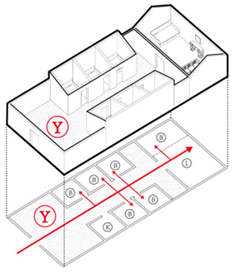

3.1. Daily Life Behavior

3.2. Cooking Behavior

3.3. Other Behavior

4. The Quantitative Research Results of Spatial Evolution Factors

4.1. The Hierarchical Structure Model of the Indicator System

4.2. The Analysis Results of the Weight Proportion

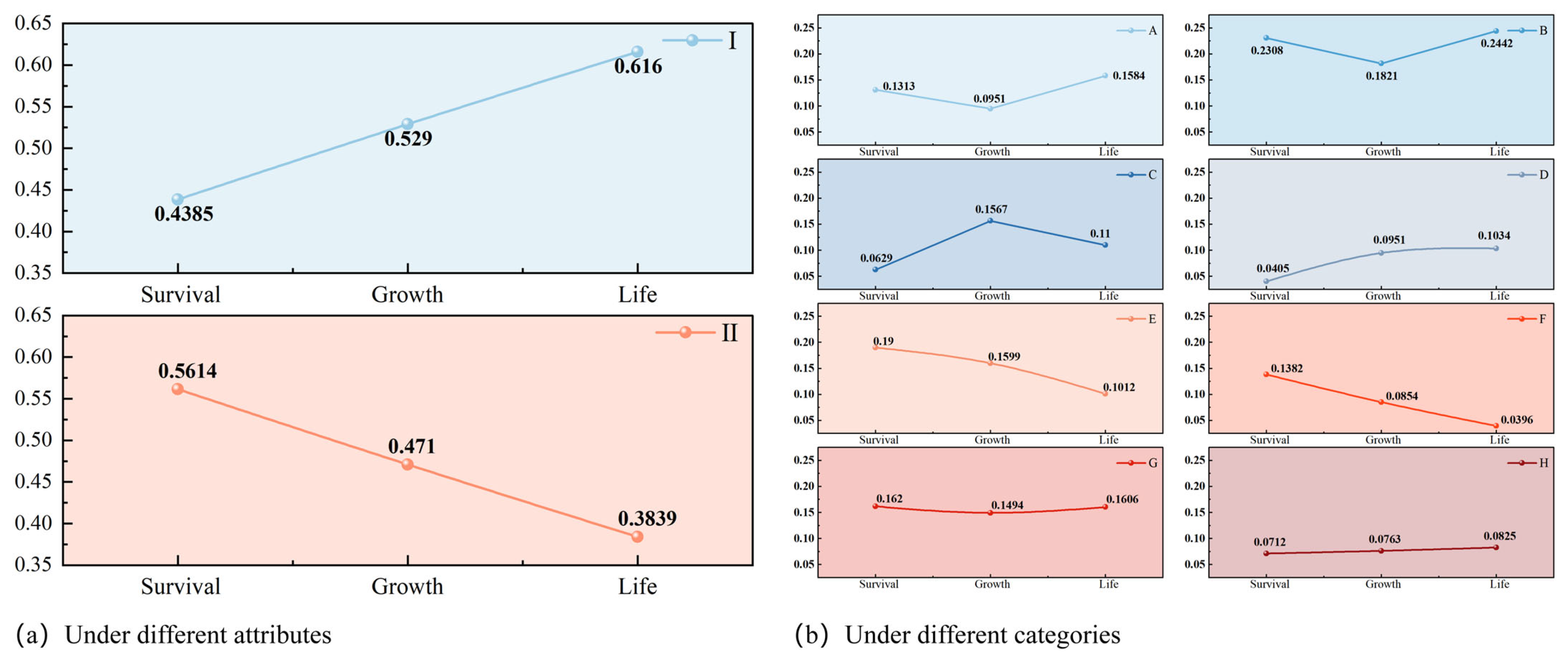

- (1)

- The weight distribution of the survival stage factors is shown in Figure 9: At the criterion layer, within the attribute dimension, the weight of internal factors is the highest (). In the category dimension, the weight of the living demand is the maximum (the highest) (); at the indicator layer, the weight that is the highest is “Land Reform System” (), which belongs to the “Policy-related” category within the internal factor dimension, followed by “Spatial Quantity” (), which belongs to the “Living Demand” category within the external factor dimension. This indicates that the evolution of the narrow courtyard residential space in rural areas of Shaanxi Guanzhong during the life stage exhibits a typical dual characteristic of “system-driven” and “survival-driven”. Specifically, land reform, as the core institutional variable, fundamentally sets the framework for the evolution of the residential space form and scale; while the absolute insufficiency of the living space quantity constitutes the most direct and urgent real motivation for residents to carry out space renovation.

- (2)

- The weight distribution of the growth stage factors is shown in Figure 10: At the criterion level, within the attribute dimension, the weight of external factors is the highest (). Within the category dimension, the weight of the living demand is still the largest (); at the indicator level, the category with the highest weight is “Family Income” under the “Economic Source” category (), followed by “Space Layout” under the “Living Demand” category (), both belonging to the external factor dimension. This indicates that in the growth stage, the evolution of the narrow courtyard residential space in rural areas of Shaanxi Guanzhong shows an evolutionary logic of “economic dominance” and “functional optimization” proceeding in parallel. With the economic development and the increase in income levels, residents’ renovation activities have shifted from meeting basic survival needs to pursuing the rationality of space function and layout optimization, reflecting the transformation trend of rural residential forms from solving basic living needs to improving quality of life.

- (3)

- The weight distribution of life stage factors is illustrated in Figure 11. At the criterion level, within the attribute dimension, external factors still hold the highest weight, while under the category dimension, residential needs remain the most dominant. At the indicator level, the highest weight is attributed to “Conservation and Ecological Development Policies” under the “Relevant Policies” category, which belongs to the internal factor dimension, followed by “Spatial Thermal Comfort” under the “Residential Needs” category. This indicates that during the life stage, the evolution of narrow-courtyard dwellings in rural Guanzhong, Shaanxi, is characterized by a synergistic driving force of “policy guidance” and “quality pursuit.” On one hand, policies related to conservation and ecological development have strengthened the regulation and guidance of construction practices. On the other hand, residents’ heightened focus on the quality of the physical environment, such as thermal comfort, signals a transition in rural housing transformation from merely meeting functional needs to addressing higher-level demands for comfort and sustainability.

4.3. The Analysis Results of the Grey Correlation Degree

- (1)

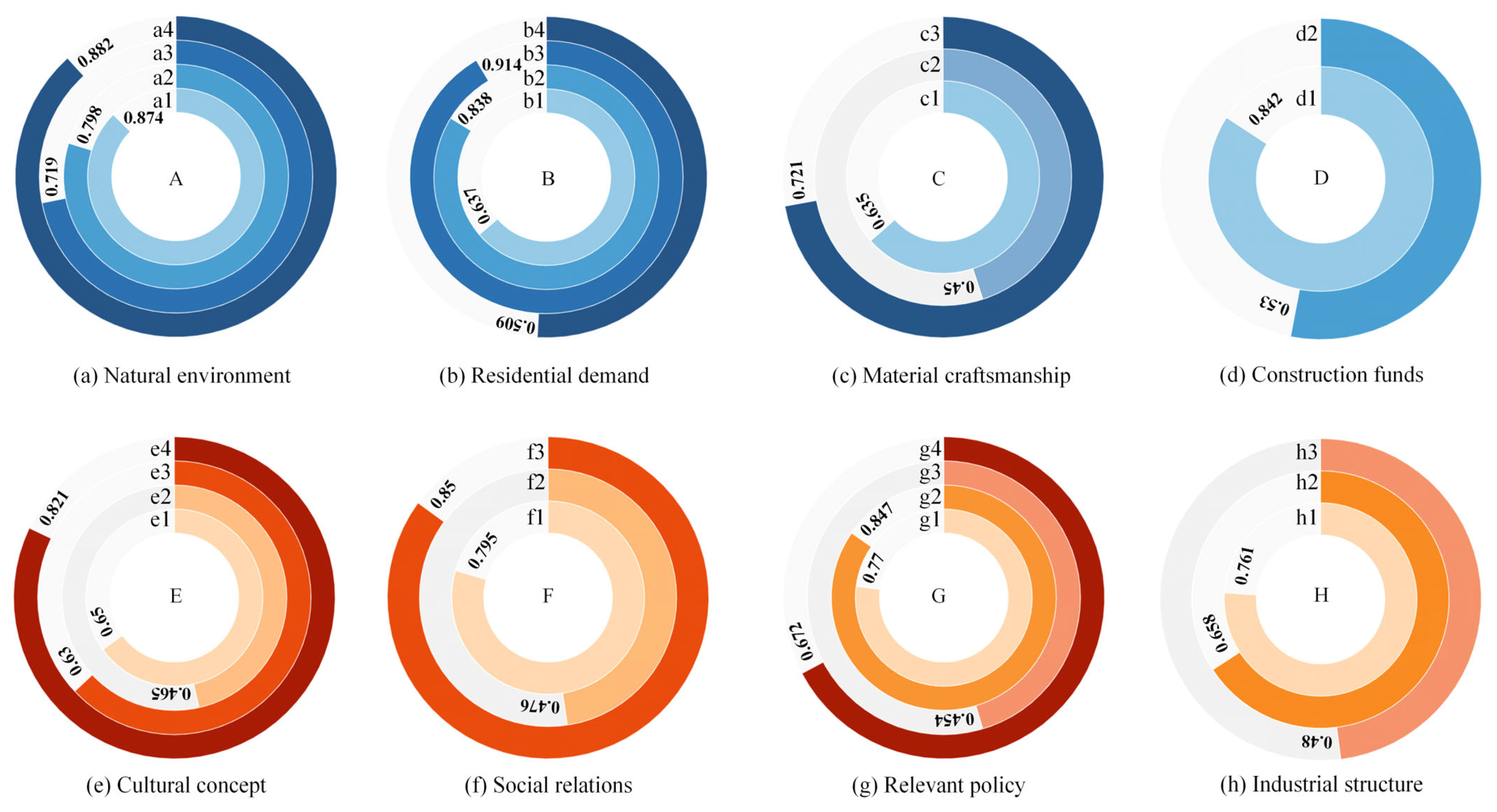

- The calculation results of the correlation degree of the criteria layer factors are shown in Figure 13: Under the attribute dimension, the correlation degree of external factors () is higher than that of internal factors. Under the category dimension, the correlation degrees of each factor from highest to lowest are: relevant policies (), industrial structure (), housing demand (), natural environment (), cultural concepts (), material techniques (), social relationships (), and economic sources ().

- (2)

- The calculation results of the correlation degree of the indicator layer factors are shown in Figure 14: By comparing the correlation degree between each specific factor and the overall category to which it belongs, the core factors that affect the natural environment, living needs, material techniques, economic sources, cultural concepts, social relationships, policies and industrial structure categories () are identified as the landform, spatial scale (), construction techniques (), family income (), folk culture (), bloodline organization (), homestead system () and agriculture (). The above results indicate that the evolution of the narrow courtyard residential space in the rural areas of Guanzhong region of Shaanxi Province at the micro level is mainly influenced by the in-depth regulation of specific elements, presenting a multi-level and refined driving characteristic. Among them, the geographical conditions and spatial scale, respectively, serve as the core of the natural environment and living demands, laying the background constraints and basic framework for the evolution of the spatial form; construction techniques, family income and folk culture, respectively, act on the functional layout and form expression of the residential space from the technical conditions, economic foundation and cultural identity three dimensions; while the bloodline organization, homestead system and agricultural structure deeply reflect the direct shaping of the spatial organization by the changes in social structure, policy management and production methods. At the same time, the results confirm and refine the macro-level judgments, further revealing that the macro driving forces such as policy regulation and industrial transformation act on the spatial evolution process through specific paths such as the homestead system and agricultural structure.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- (1)

- The evolution of the space in narrow courtyard houses is essentially a profound “de-ritualization” of space reconfiguration. This transformation is not only reflected at the morphological level, but more importantly, it is driven by the underlying mechanism: under the multiple modern forces of industrialization, urbanization, and the centralization of family structure, the ritual order and cultural symbols carried by traditional narrow courtyards have been gradually dismantled; and the logical basis of its spatial organization has shifted from following ethical hierarchical norms to a rational response to individual privacy, functional efficiency, and living comfort. This paradigm shift from “courtyard center” to “hall center” not only reflects the modern adaptation of living functions, but also echoes the theoretical discussions in international rural architecture research about the changes in spatial structure and daily life practices, providing empirical evidence for the spatial dimension of the core family-oriented lifestyle, and supplementing the applicability of the “space–society” interaction theory in non-Western contexts.

- (2)

- The evolution process simultaneously witnessed a re-evaluation of the value of the main and auxiliary spaces: In the narrow courtyard houses of the Guanzhong countryside, the functional complexity and dominance of the main living spaces (including the living room and bedrooms) continued to increase, while the previously neglected auxiliary functional spaces (including the kitchen, bathroom, and staircase) significantly improved in terms of comfort, configuration standards, and space proportion. This change reflects the modern transformation of the living concept from “priority given to etiquette” to “life quality-oriented”, and the overall spatial structure tends to be functionally balanced and human-centered optimized, which is consistent with the common trend of service space upgrading and life space specialization that occurs in the process of global rural architectural modernization.

- (3)

- The analysis of the impact factor weights objectively reveals its dynamic action pattern—from the “institutional traction” in the survival stage (such as land reform and rural housing policies), to the “economic dominance” in the growth stage (the improvement in family income drives functional optimization), and finally to the “policy guidance and quality pursuit” synergy in the life stage (ecological protection policies and thermal comfort and other quality demands); the grey correlation analysis further indicates that the relevant policies and industrial structure are the core macro factors driving the spatial evolution, clearly outlining how external systems and economic forces deeply reshape the rural residential space pattern layer by layer. This discovery has enriched the empirical research conducted internationally on the mechanism of the interrelationship between institutions, economy and the changes in the form of rural architecture.

- (4)

- The proportion of the weight given to cultural concepts has significantly decreased. The reason for this is that the core stability of these concepts has undergone a fundamental change. In the early stage, based on the ritual system and local knowledge system, it was relatively stable, and the form of residential space thus closely matched the lifestyle, presenting a unified form and clear prototype characteristics; in the middle and later stages, traditional concepts gradually disappeared, while the new cultural consensus had not yet matured and been fully formed, resulting in a conceptual “vacuum” and disorder; this lack of consensus directly reflects the diversified exploration and paradigm competition of spatial forms, indicating that the current residential form has not yet established a stable adaptation relationship with the lifestyle of the new era. This process reveals the complexity of the coexistence of cultural continuity and discontinuity during the transformation of traditional architecture.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hall, S. Rural & Urban House Typesin North America; Pamphlet Architecture: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shou, T. Elastic Enclosure: Diagramming the Spatial Construction Logic of Vernacular Architecture in Huizhou. Archit. J. 2024, 2, 1–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C. On the Origin of Species: With Additional Conjectures on the Top Ten Theories of Evolution; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2018. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Liu, J.P. Inheritance and Regeneration of Cave Dwellings in the Loess Plateau. Archit. Herit. 2021, 2, 22–31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.J.; Gao, B. The Prototype and Cultural Attributes of Traditional Courtyard Houses in Guanzhong Region from a Memetic Perspective. Archit. Creat. 2022, 6, 163–169. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.S.; Li, Z. Traditional Vernacular Dwellings in Guanzhong and Their Regional Architectural Design Models; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2016. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Xu, J.S. Adaptive Inheritance Design of Traditional Vernacular Dwellings in Guanzhong; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2016. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, B.; Yang, M.J.; Zhao, S.; Wang, X.Y. Investigation and Research on Green Construction of Vernacular Dwellings in Guanzhong, Shaanxi. Tradit. Chin. Archit. Gard. 2018, 3, 58–63+93. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=BbvBZ4vy5aSSV9rVotX3jowKA9baF31BscEayhRACFCJwhsLzHYjVeBGwCTpDGv2E_SubjFyKQgKrtHc3YO8yH7ZbZXuRj1VBvJ1pQT9EdhnWbpPg2pjUIIZXEPV4teSNBRqhMxy6QoEWTUKCOtCQvaopZlVThacpPUOGjTLPDCbW_Ac1lMHPw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 3 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Yu, Z.C.; Meng, Y.H. Green Construction of New Rural Dwellings in Guanzhong, Shaanxi. Build. Energy Effic. 2020, 48, 32–38. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=BbvBZ4vy5aQ66R0CPo-dM9J2bGBX9eaG6USjqfrw2_OzX4XDuR3SOO-2c8zN9nQ_9gvFXFMaA-OktuayNtBRJMNS9Bs9OfvLT3AP0D6-ggFAVIMy6j_p5QpiT6obK4d-Tt9qA0Qu0JHRJdWDarV0stfFw1YfXhlmYEFMNLg18lT8njvbyxzD5g==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 3 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Wang, N.Y.; Zhao, J.Y.; Wang, Q. Research on the Building Energy Efficiency System of Rural Dwellings in Guanzhong Region. Build. Energy Effic. 2021, 49, 14–20. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=BbvBZ4vy5aS-OrQSUglr282qCiT0TedDZsApyuiE2P2i7m013axvbZwc8WMkv8UMfaXzuxWYKqehKxxP9LtXveqGqcMbM6kD8hLKco9tHXWWyT_RJn6px_V2YC21PrxDnydvYRGz334mawKnokS1gwpDrfO1QhbCZ1SjAPzFJgFVt0qU_X5pfQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 3 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Cui, X.C.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, W.Q.; Liu, Y. Research on the Climatic Adaptability of Guanzhong Courtyards Based on Measured Thermal Environment Data. Build. Energy Effic. 2024, 52, 33–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D. Research on the Spatial Form Transformation of Rural Dwellings in Guanzhong Under the Influence of Land Institution; Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology: Xi’an, China, 2016. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.J.; Yang, D.; Li, Z.M. A Century of Spatial Form Changes in Rural Houses and Courtyards in Guanzhong: A Case Study of Xuelu Village in Qian County. Huazhong Archit. 2018, 36, 42–47. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, J.; Wu, T.; Li, J. A Co-Evolution Model of Planning Space and Self-Built Space for Compact Settlements in Rural China. Nexus Netw. J. 2017, 19, 473–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Wen, B.; Xu, F.; Yang, Q. From Poor Buildings to High Performance Buildings: The Spontaneous Green Evolution of Vernacular Architecture. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appeaning Addo, I.; Yakubu, I.; Gagnon, A.S.; Beckett, C.T.S.; Huang, Y.; Owusu-Nimo, F.; Brás, A.M.A. Examining change and permanence in traditional earthen construction in Ghana: A case study of Tamale and Wa. Built Herit. 2025, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, K. The Rise and Decline of Settlement Sites and Traditional Rural Architecture on Therasia Island and Their Reciprocal Interaction with the Environment. Heritage 2024, 7, 5660–5686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigiotti, S.; Santarsiero, M.L.; Del Monaco, A.I.; Marucci, A. A Typological Analysis Method for Rural Dwellings: Architectural Features, Historical Transformations, and Landscape Integration: The Case of “Capo Due Rami”, Italy. Land 2025, 14, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortenberry, B.R. Digital Documentation in Vernacular Architecture Studies. Build. Landsc. J. Vernac. Archit. Forum 2019, 26, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, T.; Saeli, M. The dammuso: Constructive characters of the traditional stone buildings of the isle of Pantelleria (Sicily). In Word, Heritage and Legacy, Culture Creativity Contamination; Gangemi Editore spa: Rome, Italy, 2019; pp. 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Cervelli, E.; Scotto di Perta, E.; Pindozzi, S. Diachronic Analyses on Land Use Changes and Vernacular Architecture Distribution, to Support Agricultural Landscape Development. J. Cult. Herit. 2025, 71, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petino, G.; Napoli, M.D.; Mattia, M. Landscape, Memory, and Adverse Shocks: The 1968 Earthquake in Belìce Valley (Sicily, Italy): A Case Study. Land 2022, 11, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Arari, K.; Amhani, Z.; Tribak, A.; El-Ommal, M.; Laaraj, M.; Azagouagh, K. Analysis of land use changes and soil erosion in the Wadi Larbâa Basin (Eastern Pre-Rif, Morocco): A spatial assessment from 1984 to 2024. Med. Geosc. Rev. 2025, 7, 1007–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat Nickayin, S.; Egidi, G.; Cudlin, P.; Salvati, L. Investigating metropolitan change through mathematical morphology and a dynamic factor analysis of structural and functional land-use indicators. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nes, A.; Yamu, C. Introduction to Space Syntax in Urban Studies; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Claramunt, C. Integration of Space Syntax into GIS: New Perspectives for Urban Morphology. Trans. GIS 2002, 6, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin Körmeçli, P. Analysis of Walkable Street Networks by Using the Space Syntax and GIS Techniques: A Case Study of Çankırı City. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case Scheer, B. The Evolution of Urban Form: Typology for Planners and Architects, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzaid, A.S.; Mazrou, Y.S.A.; El Baroudy, A.A.; Ding, Z.; Shokr, M.S. Multi-Indicator and Geospatial Based Approaches for Assessing Variation of Land Quality in Arid Agroecosystems. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, A.; Alshibani, S.M.; Ali, M.A. Smart City as an Ecosystem to Foster Entrepreneurship and Well-Being: Current State and Future Directions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, E.; Vural, D.; Canbulut, G. The most livable city selection in Turkey with the grey relational analysis. Grey Syst. Theory Appl. 2020, 10, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.J. Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tafti, F.F.; Rollo, J.; McGann, S. Conceptualising a model for understanding socio-cultural and spatial factors in housing: Insights from a systematic scoping review. Front. Archit. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, S. Architecture as Material Culture: Building Form and Materiality in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic of Anatolia and Levant. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2013, 32, 746–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Group of Shaanxi Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Synergistic Complementation to Identify Gaps: Renewed Efforts for Regional Development. Shaanxi Wang. Available online: https://www.ishaanxi.com/c/2024/0626/3179331.shtml (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- Shaanxi Provincial Bureau of Statistics; Survey Office of the National Bureau of Statistics in Shaanxi. Shaanxi Statistical Yearbook 2024; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2024. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.S.; Jiang, M. Spatial Self-Organization and Architectural Regionality; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2021. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, G.; Shi, G.; Zhang, R.; Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, J. Assessment of Intelligent Unmanned Maintenance Construction for Asphalt Pavement Based on Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation and Analytical Hierarchy Process. Buildings 2024, 14, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Ma, Y.; Wu, S. Fuzzy comprehensive evaluation on high-quality development of China’s rural economy based on entropy weight. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 38, 7531–7539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The SPSSAU Project. SPSSAU, Version 25.0; Online Application Software; The SPSSAU project: Beijing, China, 2025. Available online: https://www.spssau.com (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Zhou, J.; Ma, S.P. SPSSAU Scientific Research Data Analysis Methods and Applications, 1st ed.; Electronic Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2024. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.Y. Application of Grey Relational Analysis in Regional Competitiveness Evaluation. Stat. Decis. 2004, 11, 55–56. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Dai, S.L.; He, J.; Ji, Y.S.; Wang, S. Application of Grey Relational Analysis and Analytic Hierarchy Process in the Selection of Spray Pot Chrysanthemum Varieties. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2012, 45, 3653–3660. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=BbvBZ4vy5aS-Uvb1saKzCZndaT0pYo9GyE_y1eemm1syIPWzgJrKGNlL6m4rqoC_GbL033jdvmyYLrrcQqkp5F0r-pKt3UfBQxw7Q9CCexKML_x0uKaIw0XwAbnD1UM4jdvWive9I5H0u5mqW3MaApWIij3U5RPGbNwtd_opw8sqCwtqQQBDFQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 3 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Zhu, F. Research on the Evolution of Rural Settlement Spatial Structure in Central Zhejiang Region EB/OLEB/OL. Available online: http://www.vonarch.com/?p=16540 (accessed on 20 October 2025). (In Chinese).

- Mao, Y.L.; Ge, Y.P.; Guan, J.L.; Xie, H.X. Research on the Restructuring Evolution and Driving Factors of Rural Settlements and Farmhouses: A Case Study of Ordinary Villages in Western Henan. Dev. Small Cities Towns 2020, 38, 88–98. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Technique | Analysis Formula | Parameter Specification | Purpose or Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| qualitative | Qualitative analysis | / | / | Select the indicators that influence the evolution of residential space in narrow courtyards in the Guanzhong area of Shaanxi Province |

| Hierarchical structure model | / | / | Construct a hierarchical structure model for the evolution of residential space in the narrow courtyards of the Guanzhong region of Shaanxi Province | |

| quantify | Synthesis fuzzy appraisal | () | represents the normalized comprehensive membership degree of this evaluation index; represents the original comprehensive degree of the evaluation index; represents the sum of the original comprehensive membership degrees | The level of the normalized comprehensive membership degree can directly reflect the relative strength of this evaluation indicator in the overall spatial evolution of the narrow courtyards in the Guanzhong area of Shaanxi Province. |

| Grey correlation analysis | represents the grey correlation degree between the subsequence and the parent sequence; represents the sequence length; represents the correlation coefficient | The level of the grey correlation degree can directly reflect the consistency or similarity degree of the change trends between the sub-sequence and the parent sequence during the evolution process of the narrow courtyard residential space in the Guanzhong area of Shaanxi Province. | ||

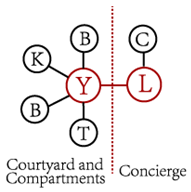

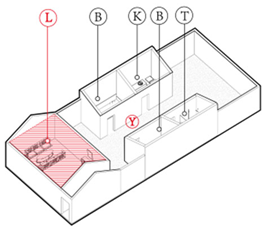

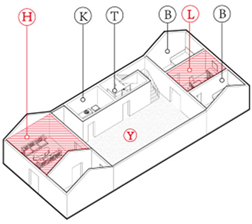

| Position Relation | Separation (Individual) | Close Proximity (Intensive) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Function Bubble Chart |  |  |  |

| Model illustration |  |  |  |

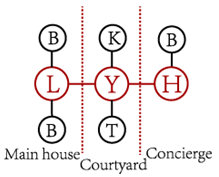

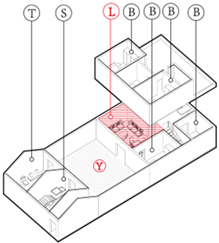

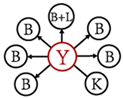

| Behavioral Path | Courtyard Direct Access | Concierge–Courtyard Entry | Concierge–Courtyard–Living Room Entry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Function Bubble Chart |  |  |  |

| Model illustration |  |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, M.; Gao, B.; Li, R. Spatial Evolution of Narrow-Courtyard Dwellings in Guanzhong Rural Areas of Shaanxi, China, from 1949 to the Present. Buildings 2025, 15, 4533. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244533

Yang M, Gao B, Li R. Spatial Evolution of Narrow-Courtyard Dwellings in Guanzhong Rural Areas of Shaanxi, China, from 1949 to the Present. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4533. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244533

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Mengjiao, Bo Gao, and Ruiwen Li. 2025. "Spatial Evolution of Narrow-Courtyard Dwellings in Guanzhong Rural Areas of Shaanxi, China, from 1949 to the Present" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4533. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244533

APA StyleYang, M., Gao, B., & Li, R. (2025). Spatial Evolution of Narrow-Courtyard Dwellings in Guanzhong Rural Areas of Shaanxi, China, from 1949 to the Present. Buildings, 15(24), 4533. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244533