Abstract

This study investigates the acoustic conditions of a design studio (Studio 130) in the Department of Interior Architecture and Environmental Design at Afyon Kocatepe University by integrating 14 weeks of continuous noise measurements with perception data collected from 192 students. Noise measurements were conducted in accordance with ISO 3382-3:2022 guidelines at three locations—window front, door side, and studio midpoint—during morning, noon, and evening periods, with 10 min recordings at each session. The results indicate that when students were present, the equivalent continuous noise level (Leq) reached an average of 65.5 dB(A), with peak levels rising to 72.3 dB(A) during jury sessions. These values substantially exceed the recommended 35 dB(A) classroom threshold by the World Health Organization and the 35–45 dB(A) limits specified in national regulations for indoor educational spaces. Survey findings reveal that 88% of students experienced loss of concentration, 72% reported decreased productivity, 60% had difficulty communicating, and 52% reported fatigue due to noise exposure. Pearson correlation analysis demonstrated a strong relationship between measured noise levels and reported negative effects (r = 0.966). Moreover, independent samples t-test results confirmed that student presence significantly increased studio noise levels (t = 4.98, p < 0.001). The novelty of this research lies in its combined use of longitudinal objective measurements and subjective perception data, addressing the unique open-plan, collaborative, and critique-based pedagogical structure of design studios. The findings highlight that acoustic comfort is a critical component of learning quality in studio-based education. Based on the results, the study proposes several design and material interventions—including spatial dividers, acoustic ceiling panels, fabric-wrapped absorbers, and impact-reducing flooring—to enhance auditory comfort. Overall, the study emphasizes the necessity of integrating acoustic design strategies into studio pedagogy to support concentration, communication, and learning performance.

1. Introduction

Room acoustics and noise control principles play a fundamental role in managing and mitigating unwanted sound in educational environments. While room acoustics—largely governed by reverberation time—regulates the behavior of sound within enclosed spaces, noise control focuses on maintaining acceptable sound levels through the design of the building envelope and internal partition elements. In Türkiye, the Regulation on the Protection of Buildings Against Noise (No. 30082), enacted on 31 May 2018, outlines the mandatory design, construction, and maintenance considerations required to minimize physiological and psychological harm and to ensure appropriate hearing conditions throughout building use [1,2]. However, research indicates that even environments intentionally designed for social interaction may suffer from acoustical inadequacies. Guo et al. [3] showed that although a moderate level of ambient noise can contribute to a pleasant atmosphere in informal learning spaces such as cafés, overall noise levels in such settings often exceed recommended standards, particularly in terms of maximum sound levels.

Recent studies also demonstrate that elevated background noise levels significantly reduce the transmission and perception of instructional speech. Li et al. [4] found that hybrid learning environments, characterized by extensive equipment use, often experience increased BNL values, while key acoustic parameters such as SNR and RT show strong negative correlations with speech intelligibility. These acoustic degradations pose heightened challenges in design studios, where intensive peer interaction, critique-based dialogue, and continuous verbal exchange form the core of pedagogy. Reduced intelligibility in such contexts directly impairs students’ capacity to follow critiques, process conceptual feedback, and sustain creative decision-making, underscoring the necessity of controlling noise levels and optimizing room-acoustic parameters to maintain effective communication in studio-based design education.

Recent findings further demonstrate that the physical conditions of educational buildings particularly ventilation, lighting, thermal comfort, and noise play a decisive role in shaping students’ psychological well-being and cognitive processing. Wen et al. [5] reported that noise conditions are a strong predictor of student anxiety (OR = 0.415) and that excessive noise levels reduce hearing and comprehension while increasing irritability and triggering anxiety-related responses. These results highlight the necessity of maintaining a conducive acoustic environment to safeguard speech intelligibility and cognitive performance. Given the prolonged working hours, interaction-intensive pedagogy and open-plan spatial configuration of design studios, students in such environments may be especially sensitive to adverse noise exposure.

Growing evidence from architecture and design education further reinforces the importance of acoustic comfort. Al-Jokhadar et al. [6] reported that noise is one of the most influential Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) parameters affecting concentration and academic performance in open-plan studios. Bilmez et al. [7] similarly observed that studio acoustics directly impact communication during critiques, spatial perception, and students’ emotional responses. European studies [8,9] confirm that noise levels above 60 dB(A) impair speech intelligibility and elevate cognitive load, particularly during collaborative tasks. Okoyeh et al. [10] further emphasized that design studios present unique acoustic challenges compared to traditional classrooms due to constant peer interaction, mobility, and equipment use. While these contributions offer valuable insights, most existing studies rely either on short-term measurements or solely on subjective surveys. There remains a notable gap in research combining long-term objective noise monitoring with student perception data. Addressing this gap, the present study integrates 14 weeks of continuous noise measurements with a large-scale perception survey to provide a comprehensive evaluation of acoustic comfort in interior architecture studios.

This study measures noise levels in the design studios of Afyon Kocatepe University’s Department of Interior Architecture and Environmental Design and evaluates their effects on students’ learning processes. It highlights why noise levels in design studios are problematic: conversations, discussions, and creative activities intensify background noise, making project-based learning processes distinct from traditional classrooms.

The novelty of this study lies in analyzing and supporting with data the relationship between noise levels in design studios and learning outcomes, filling a gap in the literature. The objectives are: (i) to measure and analyze noise levels, (ii) to evaluate students’ noise perceptions, and (iii) to propose acoustic interventions to improve learning conditions. Unlike classroom acoustics studies, this research evaluates noise effects within the unique pedagogical and spatial dynamics of design studios through 14 weeks of field measurements and perception surveys, revealing how noise control is critical in project-based and group-oriented learning.

Methodological Contribution: Systematic measurements were conducted over a 14-week period at three different points (window, door, center) and at various times of day (morning, noon, evening), following ISO 3382-3:2022 guidelines. A Class 1 sound level meter (IEC 61672-1: 2013 [11]) and a Class 1 calibrator (IEC 60942: 2017 [12]) were used, with ±0.3 dB accuracy and two-point calibration performed before and after each measurement session. This longitudinal, standards-compliant approach distinguishes the study from previous short-term research and provides a robust methodology that effectively controls temporal variability.

Contribution to Generalizability: While most studies focus on classrooms or laboratories, this research examines design studios—open-plan, project-based, and socially dynamic environments—making its findings widely applicable to architecture and interior architecture programs. The integration of objective acoustic data (dB levels) with subjective perceptions (survey responses) offers a dual perspective that is rarely combined in prior studies.

Contribution to Education: The results demonstrate how noise affects student motivation, concentration, collaboration, and learning within studio-based education. The recommendations extend beyond architectural solutions by emphasizing that noise control directly supports design pedagogy, positioning noise management as a pedagogical criterion in studio instruction. The study identifies key noise sources in the department’s design studios and proposes both design and managerial strategies (e.g., acoustic panels, noise-reducing dividers, sound-absorbing materials) to enhance overall acoustic quality.

The term noise, derived from the Latin nausea, is defined as “the wrong noise at the wrong place and time” or “unwanted sound” [13]. Physically, noise consists of high-level, complex sounds with irregular structures and incompatible tonal components [14]. Noise has always been a major urban problem; the main difference between modern and past societies is that today a far greater portion of the population is exposed to noise pollution [15].

Noise pollution is one of the major urban problems worldwide [13] and is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as unwanted or excessive noise that may harm human health and environmental quality [16]. It is an environmental problem caused by urbanization and significantly lowers the quality of life [13,17]. Noise negatively affects mental health and work performance, and over time may lead to high blood pressure and memory loss [18,19]. It is also associated with various negative emotional and physiological effects such as annoyance, sleep disturbance, cardiovascular and cognitive disorders, headaches, dizziness, fatigue, hearing loss, anger, unhappiness, anxiety, and depression [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

According to [28], the effects of different noise levels on humans are summarized as follows:

- 0–35 dB(A): No damage;

- 36–65 dB(A): Disturbing; may affect sleep and rest;

- 66–85 dB(A): Mentally harmful; may cause hearing problems;

- 86–115 dB(A): Causes mental and physical damage; may trigger psychosomatic diseases;

- 116–130 dB(A): Dangerous; can lead to deafness;

- 131–150 dB(A): Extremely dangerous; causes instant harm without protection.

2. Materials and Methods

Noise, especially in educational buildings, is a significant environmental factor that negatively affects learning processes. It reduces students’ concentration, motivation, and overall performance. Therefore, controlling both internal and external noise sources is critical for creating healthy and productive learning environments. Table 1 is adapted from the Regulation on the Protection of Buildings Against Noise [2] and presents the standard noise levels in dB(A) and building classes for educational facilities as stated in the regulation. The A–F symbols represent acoustic quality classes—where A indicates the best and F the lowest performance—determined by parameters such as background noise and reverberation time (RT).

Table 1.

Permissible Indoor Noise Levels (Class buildings) [2].

Maintaining noise levels within standards in educational structures—especially in design studios—is essential for educational quality and efficiency. The functioning of design courses in studio environments differs from theoretical classes held in traditional rooms; this creates notable differences in students’ perception and motivation.

The source, level, and impact of noise vary depending on building type (Table 2). In this context, investigating noise levels in educational buildings—the focus of this study—and taking preventive measures are essential for maintaining student motivation and well-being.

Table 2.

Noise sources and affected areas in educational buildings [14,29,30].

Noise in educational buildings arises from both internal and external sources such as vibrations, mechanical systems, and facility activities [31]. When noise levels exceed acceptable limits, educational quality declines—speech is masked, comprehension decreases, attention dissipates, learning is prolonged, students may misbehave, and teachers are forced to raise their voices [31,32]. These effects hinder students’ psychological, behavioral, and academic development, reduce communication efficiency, and lower overall instructional quality [31,33,34]. Therefore, noise reduction and prevention are critical in educational environments [8,35,36].

According to WHO guidelines, the recommended classroom noise limit is 35 dB(A), while Turkish regulations specify 35 dB(A) for closed windows and 45 dB(A) for open windows [37]. Other studies suggest thresholds of 35–47 dB(A) depending on room size and function [33,38], and 40–60 dB(A) for outdoor noise in design studios [33]. Because educational spaces are shaped by pedagogy, duration, and student profile, effective design—especially in applied disciplines such as architecture and interior architecture—requires flexible, adaptive solutions ensuring sustainable acoustic comfort [34,35].

Design studios differ fundamentally from traditional classrooms by integrating both individual and collaborative learning through formal (lectures, group work, juries) and informal (peer learning) activities [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. They foster critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving, yet their open, socially dynamic structure poses acoustic challenges: while openness supports collaboration, auditory privacy is necessary for concentration, making balanced acoustic design essential [41,44].

Research on Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) highlights noise—alongside ventilation, lighting, and temperature—as a key determinant of students’ performance and well-being [6]. Noise is one of the most frequent stressors in design studios, disrupting communication, focus, and creativity during long sessions [10,45]. Studies show that studio characteristics directly affect students’ perceptions and may cause physical issues (hearing problems, stress, sleep disorders) [10,46] and psychological effects such as reduced concentration and irritability [9].

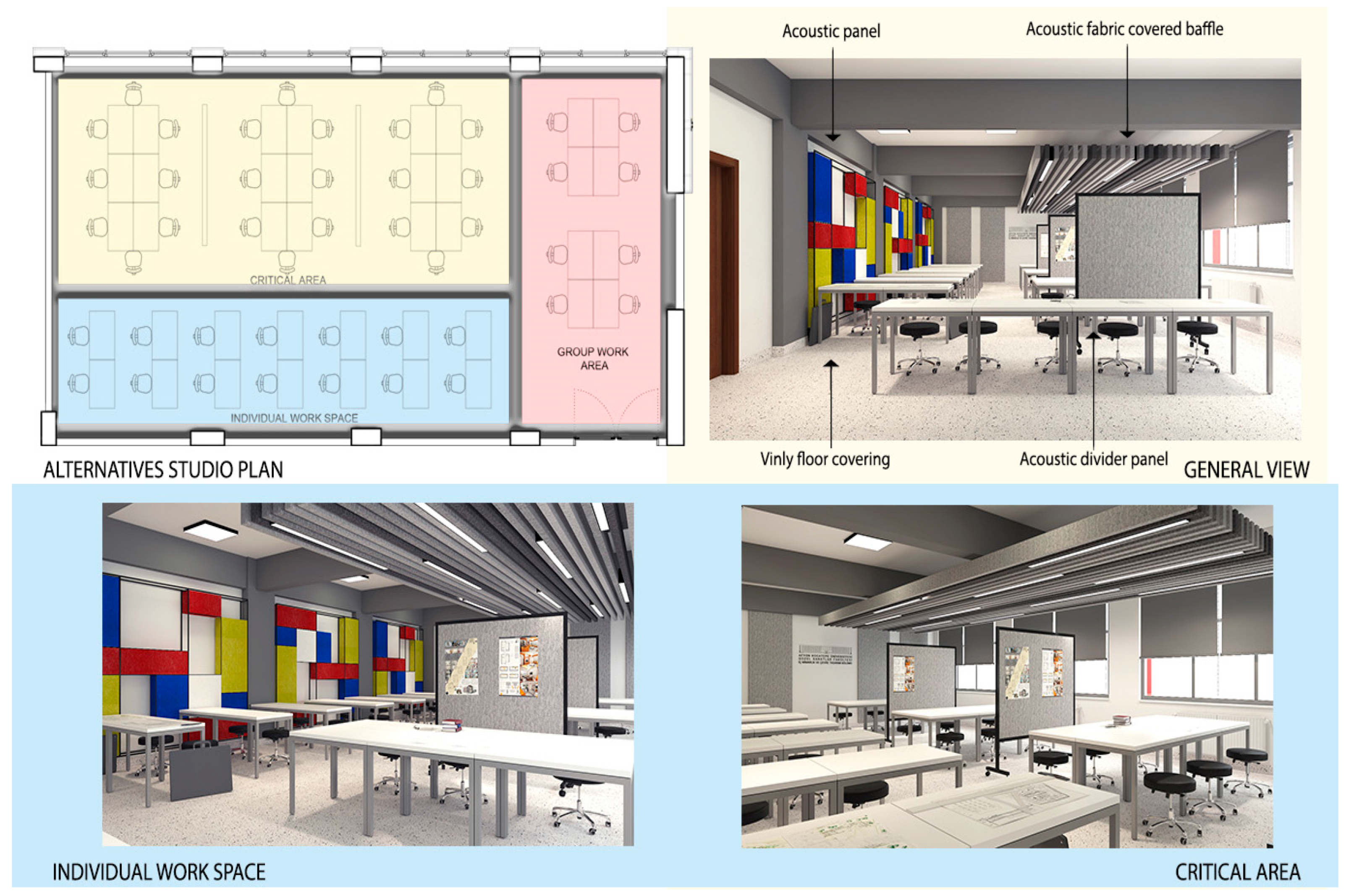

Architectural variables like furniture layout, surface materials, and sound reflection rates strongly influence acoustics. However, in open-plan studios where sound sources and listeners shift constantly, standardized classroom-based solutions are insufficient [40]. Hence, auditory comfort becomes a critical requirement for maintaining motivation, concentration, and productivity in design education [9,41]. Failure to achieve it can significantly reduce learning efficiency and academic motivation. The visuals presented in this table are not scaled architectural plans; rather, they are schematic representations illustrating the spatial layout characteristics of traditional classroom environments and design studios. These graphics serve an explanatory purpose by highlighting the organizational differences between the two learning settings and do not convey dimensional accuracy or technical plan information. Accordingly, the table functions as a comparative tool that visually summarizes distinctions in spatial configuration, furniture arrangement, interaction patterns, and acoustic considerations between classroom and studio environments. Table 3 summarizes the spatial differences between traditional classrooms and design studios.

Table 3.

Spatial differences between traditional classroom environments and design studios.

2.1. Materials

The study aims to determine the noise levels reaching the design studios in Interior Architecture departments from the environment and to examine the effect of this noise on students’ motivation in design courses. Within the scope of the study, the existing noise levels in the studios were measured and the data obtained were evaluated by comparing with the relevant acoustic standards. In line with the analyses, it is aimed to determine the necessary physical and design measures to increase the working efficiency of the students. In the study, answers to the following questions were sought:

- What are the current noise levels in the design studios in the Department of Interior Architecture and Environmental Design?

- Do these noise levels comply with national and international noise level standards?

- How do noise levels affect the working efficiency of Interior Architecture and Environmental Design students?

- What are the noise sources in the work area and how can the impact of these sources be reduced?

- What measures should be taken to improve the sound quality in Interior Architecture and Environmental Design studios?

Afyon Kocatepe University, which is the study area, was established in 1992 in Türkiye and has 31,520 students and approximately 2000 academic and administrative staff since its establishment. It continues its educational activities with 13 faculties, 3 institutes, 3 colleges, 1 state conservatory and 14 vocational schools [27]. The Faculty of Fine Arts, where the study was conducted (Figure 1), is located on the Ahmet Necdet Sezer Campus of Afyon Kocatepe University. The faculty comprises the Departments of Interior Architecture and Environmental Design, Cinema and Television, Ceramics, Painting, and Traditional Turkish Arts. Figure 1 illustrates the location of the faculty within the campus and its spatial relationship with the surrounding buildings.

Figure 1.

Location of the Faculty of Fine Arts marked on the site plan.

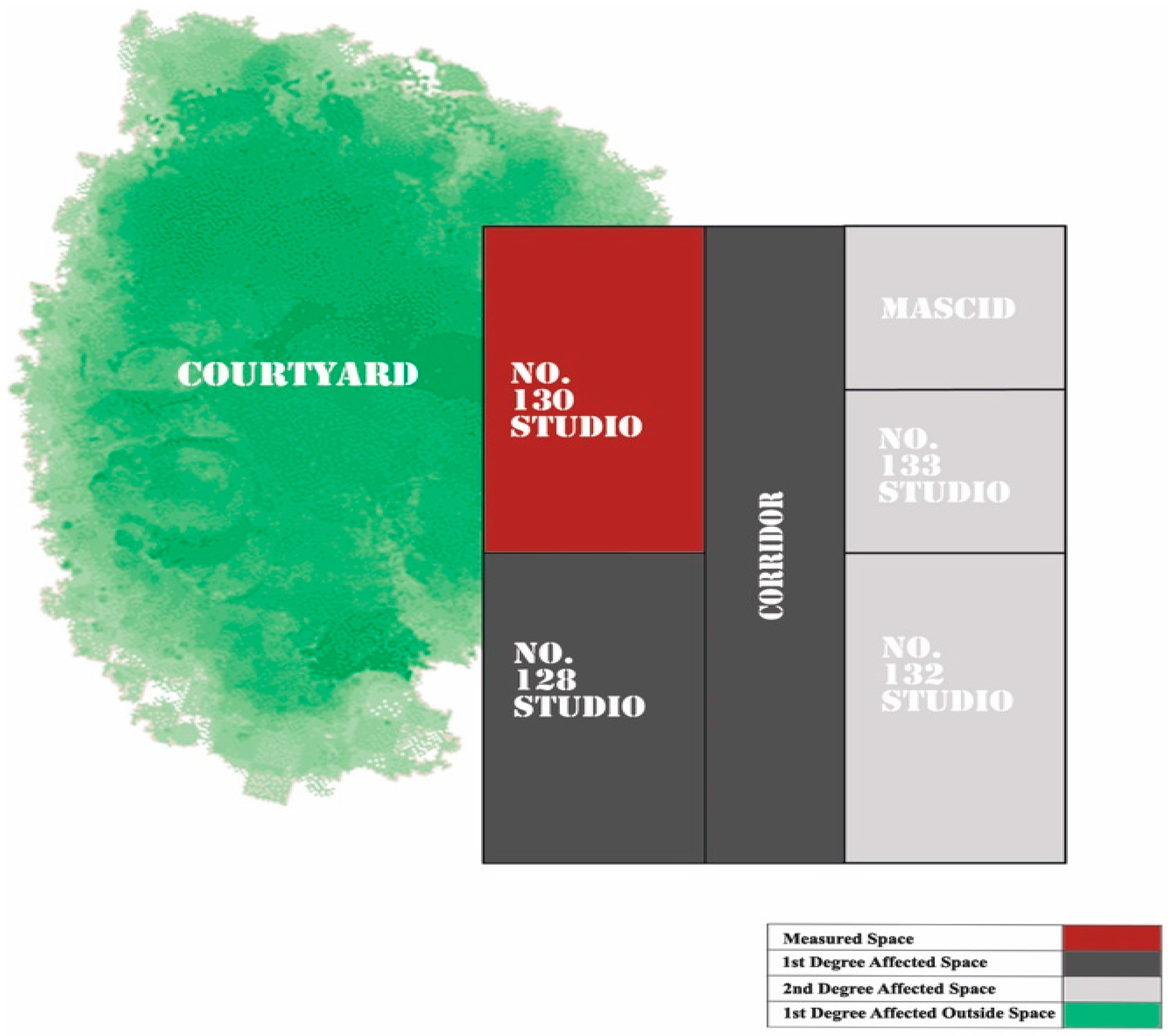

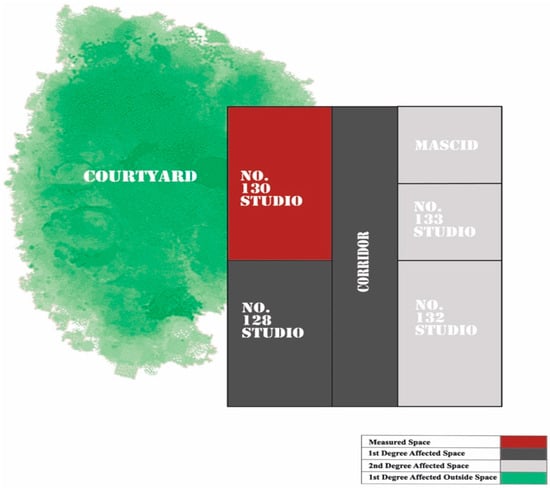

The Faculty of Fine Arts, with 1123 students and 55 staff, shares a common courtyard with the Faculty of Technology and the State Conservatory, bringing the total number of users in the area to 2811. The study was conducted in Studio 130, a space belonging to the Department of Interior Architecture and Environmental Design (Figure 2). This studio was selected as the study area because design studios are central to the department’s pedagogy and include courses related to acoustics. Studio 130 was specifically selected as the case study due to its direct exposure to courtyard noise, frequent use for group critiques and jury sessions, and significant external sound leakage from window joints despite its aluminum composite façade. The space lacks a dedicated ventilation system, features plaster-mounted lighting fixtures, and experiences additional noise from students’ computers during studio hours.

Figure 2.

Schematic plan, the location of studio no. 130 of the Department of Interior Architecture and Environmental Design within the faculty and its relationship with the physical environment.

2.2. Methods

The method of the study consists of noise measurements and questionnaire analyses with students using the studio where noise measurements were made. Within the scope of the study, noise measurements were made in the studio (studio no. 130), which has a façade to the courtyard that students use intensively between classes.

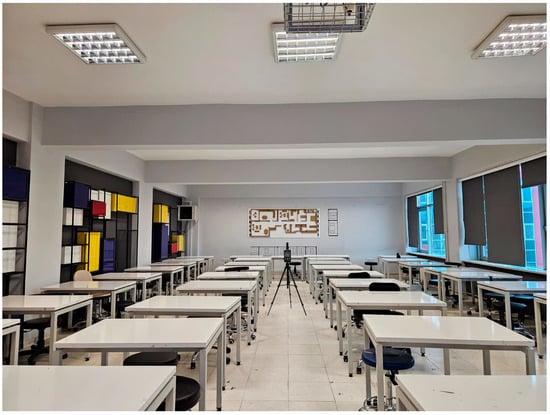

In interpreting the measurement results, internationally recognized thresholds were taken into account. Reference [8] recommend background noise levels not exceeding 35 dB(A) in classrooms and 55 dB(A) in outdoor educational spaces. In addition, the Turkish Regulation on the Protection of Buildings Against Noise [2] specifies permissible indoor levels between 35–45 dB(A) depending on building classification, while the Regulation on the Assessment and Management of Environmental Noise [37] sets the classroom limits at ≤35 dB(A) with closed windows and ≤45 dB(A) with open windows. Furthermore, the measurement methodology followed ISO 3382-3:2022, which defines descriptors for open-plan educational spaces. Although ISO 3382-3:2022 is primarily developed for open-plan offices, its use in this study is justified because Studio 130 functions as an open-plan educational workspace with similar acoustic conditions—continuous speech, group work, movement, and the absence of full-height partitions. Therefore, the measurement procedures of ISO 3382-3 (microphone height, distance from reflective surfaces, spatial averaging rules, and measurement duration) were directly adopted to obtain reliable and repeatable LAeq, Lmax, and Lmin values suited to hybrid studio environments. Office-specific parameters defined in the standard (e.g., distraction distance) were not used; only the measurement protocol was adapted for the studio context. According to the Regulation on the Assessment and Management of Environmental Noise dated 27 April 2011, measurements are planned to be carried out during the daytime hours from 07:00 to 19:00 in the morning (09:00)-afternoon (12:00)-evening (17:00). Noise measurements were taken weekly over a 14-week period, including morning, afternoon, and evening sessions. For each measurement day, data were collected for 10 min at three points (window, door, and studio center). Weekly variations were analyzed by calculating the average, minimum, and maximum values. Figure 3 shows the noise measurement conducted at the center point of the studio, which represents the overall acoustic condition of the space.

Figure 3.

An example of a measurement taken when the classroom is empty.

The measurements were conducted using the PCE-NDL 10 sound level meter, a Class 2 certified device (IEC 61672-1) with a frequency range of 31.5 Hz–8 kHz and an accuracy of ±1.4 dB. The instrument allows measurements in both A and C frequency weightings, with S (slow) and F (fast) response modes, and records sound pressure levels (SPL) and dose measurements in decibels (dB(A)). Data can be stored in the internal memory or on an SD card, ensuring reliable documentation. Prior to each measurement session, the sound level meter was calibrated with the PCE-SC 42 acoustic calibrator, a Class 1 (IEC 60942) certified instrument with an accuracy of ±0.3 dB, capable of performing two-stage calibration at 94 dB(A) and 114 dB(A) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Measurement Equipment.

It enables quick and accurate checking of sound level meters in routine laboratory or field calibrations. As a result of the measurements, Lmin, Lmax, Leq values were obtained. The obtained A-weighted parameters are defined below.

Lmax (the highest noise level): “The highest level at any moment of the changing noise according to time”.

Lmin (the lowest noise level): “The lowest level at any moment of the changing noise according to time”.

Leq (equivalent noise level): “The total noise energy which shows continuity regularly or irregularly between a certain T time or the noise scale in the dB(A) units obtained with the division of the measurement period of noise pressures [47]. Noise measurements were carried out in Studio no. 130 of the Department of Interior Architecture and Environmental Design, as well as in the corridor adjacent to the studio. The studio has interior dimensions of 7.70 × 14.60 × 3.35 m (width × length × height). Measurements were taken continuously for 10 min at each point, with the microphone height standardized at 1.5 m above the floor in accordance with ISO 3382-3:2022 recommendations for open-plan educational areas. For courtyard façade measurements, the device was positioned 1 m inside from the window, free of reflective surfaces. Corridor measurements were taken 1 m away from the corridor wall, also without reflective surfaces. At the studio centre, the device was positioned at the exact geometrical centre of the room, again at 1.5 m height. Measurements were repeated both during teaching hours (with students present, capturing speech and activity noise) and during empty conditions between or after classes (focusing on external noise sources such as traffic and building services). Prior to each measurement session, the sound level meter was calibrated using the PCE-SC 42 acoustic calibrator, a Class 1 (IEC 60942) certified instrument, performing a two-stage calibration at 94 and 114 dB(A). The measurement points, as well as the plan and sections of the studio, are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Layout of studio no. 130, plan diagram, sections, studio visuals and points measured in the studio.

Measurement Uncertainty and Reporting

Instrumentation and calibration: IEC 61672-1 Class 1 m; IEC 60942 Class 1 calibrator; manufacturer accuracy ±0.3 dB; two-point field calibration at 1 kHz (94/114 dB(A)) before/after each session.

Reported metrics: LAeq → mean + 95% CI; Lmax/Lmin → 5th–95th percentile ranges alongside instrument accuracy.

Decision rule: differences are meaningful only if Δ ≥ 3.0 dB and 95% CIs do not overlap; Δ < 1.0 dB is treated as within measurement uncertainty.

Rounding: all acoustic quantities (dB values, LAeq, Lmax, Lmin) are reported to one decimal place.

Octave bands: where available, the same rules apply to octave-band LAeq, Lmax, Lmin; otherwise stated as a limitation.

After the measurements, a questionnaire study was carried out to determine the students’ level of noise exposure and discomfort in the design studio The questionnaires were conducted with the 3rd and 4th year Interior Architecture and Environmental Design students due to the high number of applied courses carried out in design studios. There are 248 students studying in the 3rd and 4th year in the department.

The sample size was determined based on 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error; in this context, the number of subjects was calculated as 151. The following equation [27,48,49] was used to determine the sample size:

where

n = (Z2 × N × p × q)/(d2 × (N − 1) + Z2 × p × q)

n = Sample size;

Z = 1.96 = Confidence coefficient (%95);

P =0.50 = Assumed proportion (maximum variance);

Q = 1 − P = (0.50);

N = Main mass size (248);

d = 0.05 = margin of error.

According to the calculations, the required number of participants was found to be 151. However, in order to further increase the reliability of the study, the survey was conducted with 192 students. The questionnaires were administered between 17–21 May 2025. Although the minimum required sample size was calculated as 151 at a 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error, the survey was administered to 192 students to increase statistical power, enhance representativeness, and reduce sampling bias. Since participation was voluntary and the response rate was high among 3rd and 4th year students who actively use the design studios, including all valid responses strengthened the reliability of the findings.

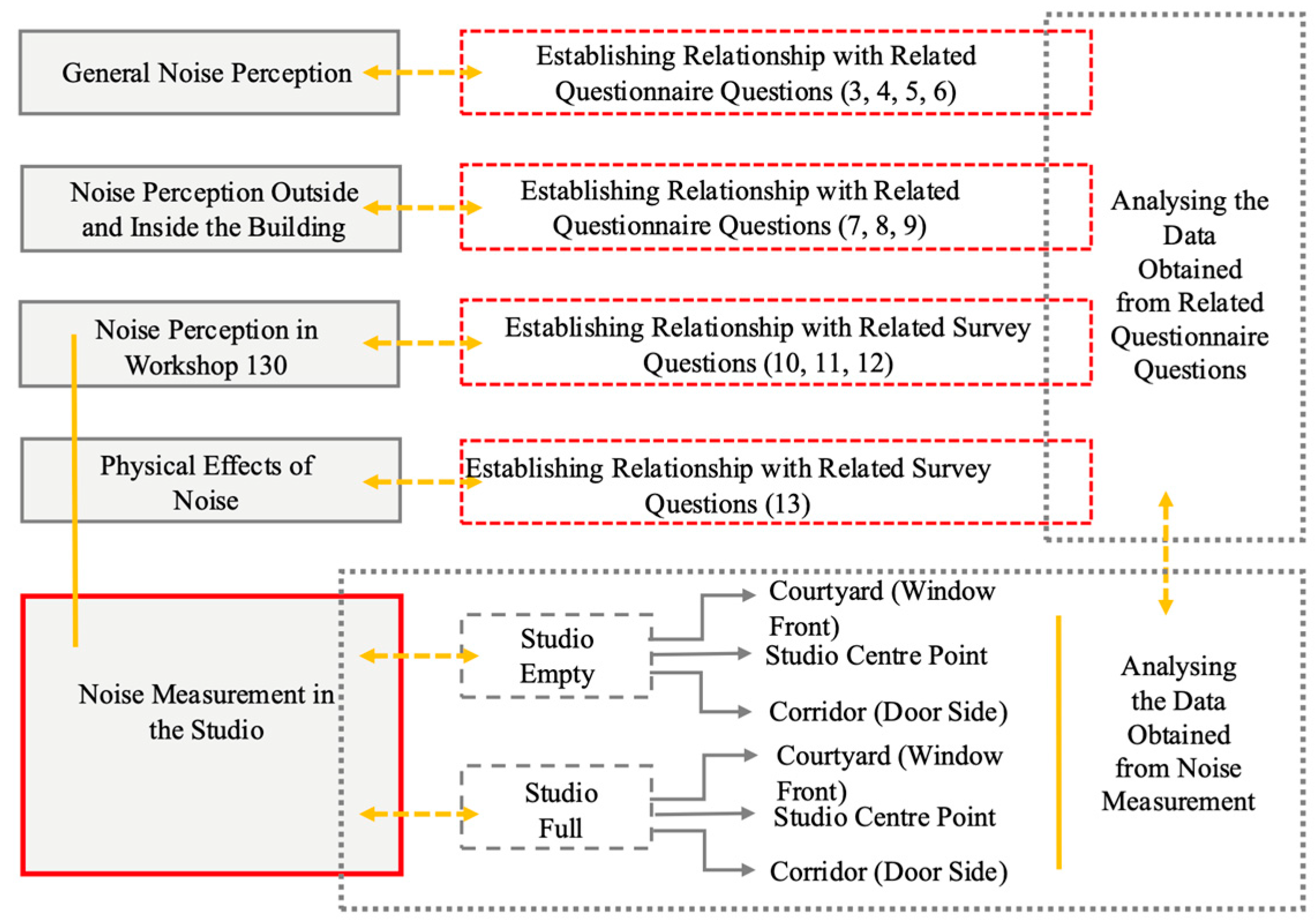

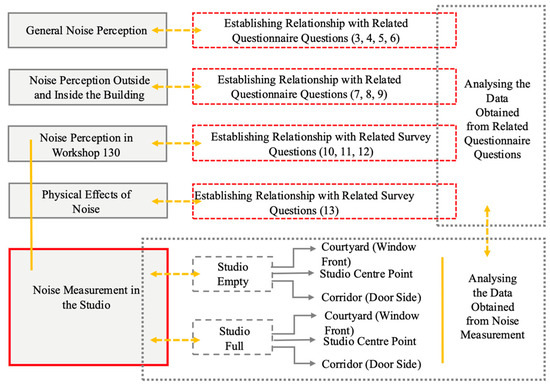

The questionnaire used in this study was developed based on previous research in the literature [39,50,51], and adapted to the design studio context. It consisted of 5 sections and 15 items in total. The first section included demographic questions (e.g., gender, year of study), while the second section assessed students’ discomfort due to noise. The third and fourth sections focused on the perception of noise within the building and its surroundings, and noise specifically within the design studio. The final section addressed the perceived disturbing effects of noise on learning. Example questions include: “To what extent do you find the studio environment noisy during classes?” and “Does noise negatively affect your ability to concentrate or participate in group critiques?”. The questionnaire employed a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The study protocol was approved by the Afyon Kocatepe University Social and Human Sciences Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee (Decision No. 2024/316). The survey results were then cross-analyzed with the noise measurements to establish correlations, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Methodology of the study.

It should be noted that the survey used in this study is a self-constructed instrument adapted from previous research to reflect the unique pedagogical and spatial characteristics of design studios. As such, it is not an internationally standardized scale with established validity across different educational contexts. Although the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (0.87) demonstrates strong internal consistency and indicates that the items reliably measure the intended construct, the tool has not undergone broader international validation. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with this limitation in mind. Future research should incorporate validation studies using larger and more diverse samples or employ internationally validated instruments to enhance cross-study comparability. Nevertheless, considering the specific context and distinctive features of the studio environment examined in this research, the questionnaire provides sufficient sensitivity and relevance to meet the aims of the study.

In the study, various statistical analyses were used to compare and interpret survey data and noise measurements. An independent samples t-Test was used to compare noise levels based on the presence or absence of students, a one-way ANOVA was used to examine the average differences between different locations and noise types, and a Post Hoc Tukey test was used to determine which groups had significant differences. The Chi-Square Test (χ2) was applied to evaluate the relationship between categorical data (noise types, location types, and complaint rates). The Paired t-test was used to compare measurements taken at the same location but under different conditions. Pearson Correlation Analysis was performed to determine the linear relationship between measured noise levels and the percentage of discomfort indicated in the survey results, and simple linear regression analysis was applied to evaluate the predictive power of noise level on the percentage of discomfort. Since there was no direct measurement data for noise levels according to work types, the relevant locations were logically matched, and a representative matching and descriptive comparison method was used.

3. Results

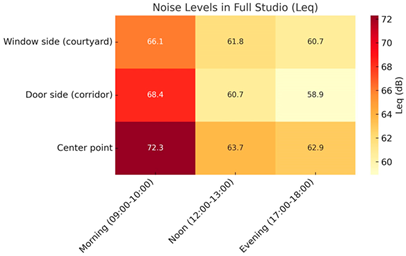

The data obtained as a result of the measurements of the noise level are given in Table 4 in dB(A) as Leq, Lmax and Lmin. Differences are interpreted within the predefined uncertainty framework: effects are deemed meaningful only when Δ ≥ 3.0 dB and 95% CIs do not overlap; Δ < 1.0 dB is treated as within measurement uncertainty. Where available, octave-band summaries follow the same rule set (Table 5).

Table 5.

Noise Level Measurement Results of Studio 130 of the Department of Interior Architecture and Environmental Design.

In the study, the weekly averages of LAeq, Lmax, and Lmin were calculated for each measurement point (window, door, midpoint, corridor) over a 14-week period. After verifying the assumptions (Shapiro–Wilk p > 0.05; Levene p = 0.21), a one-way ANOVA indicated no statistically significant differences across weeks (p > 0.05); effect sizes (η2) were within the small to medium range. Tukey post hoc comparisons also confirmed that week-to-week differences did not reach significance after multiple comparison adjustment. The findings demonstrate that the studio’s acoustic conditions remained relatively stable throughout the semester.

The data obtained as a result of the questionnaires and the analyses of the data obtained from the noise measurements made in the studios are presented in Table 5 in order to measure the effect of noise levels on the students in the study area, studio 130 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Analysis of noise measurements and survey results.

In the literature, in studies conducted by [52,53,54] it was stated that when the alpha confidence coefficients are above 0.60, it can be accepted as “reliable”. “Cronbach alpha” is 0.87 so scale reliability is provided for each dependent variable (Table 7).

Table 7.

Cronbach Alfa results.

Before applying ANOVA, the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were tested. Shapiro–Wilk tests confirmed that the distributions did not differ significantly from normal distribution (p > 0.05), and Levene’s test showed homogeneity of variances (p = 0.21). Therefore, one-way ANOVA was applied. These results validate the use of ANOVA and Tukey analyses in this study (Table 8). Shapiro–Wilk tests (p > 0.05) showed that the data were normally distributed, and Levene’s test (p = 0.21) indicated homogeneity of variances. Accordingly, the application of ANOVA and Tukey tests was deemed appropriate, and df, F, p, and η2 values were calculated for each measurement point in the analyses.

Table 8.

Statistical Assumptions Check for ANOVA and Tukey Analyses.

According to the data obtained; Relationship between questions 3 and 4; Chi-square test: χ2 (1, N = 192) = 48.09, p < 0.001

Since the p-value is much smaller than 0.05, there is a statistically significant relationship between being bothered by noise and having difficulty concentrating in non-classroom settings. This indicates that the vast majority of participants exposed to noise also experience concentration problems (Table 9).

Table 9.

Correlation analysis.

- The value r = 0.528 indicates a moderate positive relationship.

- Since p < 0.001, this relationship is statistically highly significant.

- In other words, as annoyance from noise increases, the likelihood of experiencing concentration problems in non-classroom settings also increases.

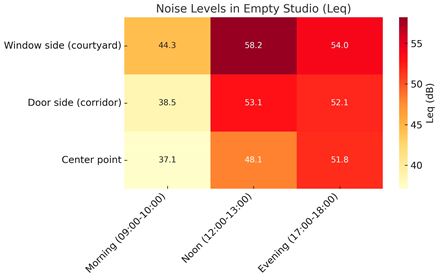

In the survey results, 92% of participants stated that the environmental factor that bothers them the most in their daily lives is “noise.” To confirm this finding, Leq values were compared according to student presence in measurements taken at all locations and times. The independent sample t-test showed that noise levels were significantly higher when students were present (t = 4.98, p = 0.00056). The average Leq value was measured as 65.50 dB(A) when students were present and 46.55 dB(A) when they were absent (Table 10).

Table 10.

Survey results (The average Leq value and Standart Deviation).

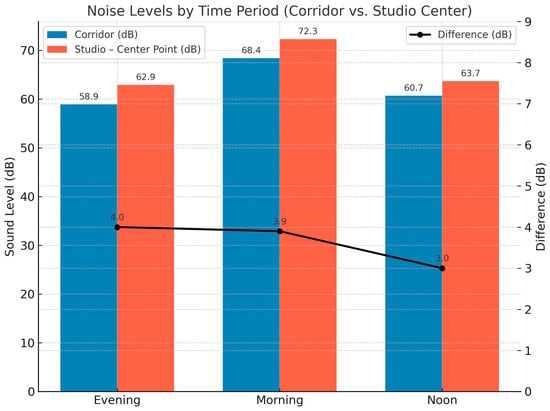

When comparing the presence/absence of students in the morning, noon, and evening measurements, it is observed that the presence of students increases noise levels in all time periods. The highest difference was observed in the morning hours (68.9 dB(A)—students present, 39.9 dB(A)—students absent; difference ≈ 29 dB(A)). The situation can be explained by the fact that in the morning hours, students enter and exit the premises intensively, engage in preparatory activities, and generally have a high level of activity.

In the afternoon hours, the difference is approximately 9 dB(A), indicating that the noise level remains high even when students are absent, likely due to meal and rest periods. In the evening, the difference is approximately 8 dB(A); this indicates that, despite the decrease in student activity as the day progresses, there are still some sources of noise (e.g., technical equipment, outdoor sounds) in the environment.

These findings clearly demonstrate the effect of student presence on noise levels and support the survey data indicating that “noise” is the most disturbing environmental factor.

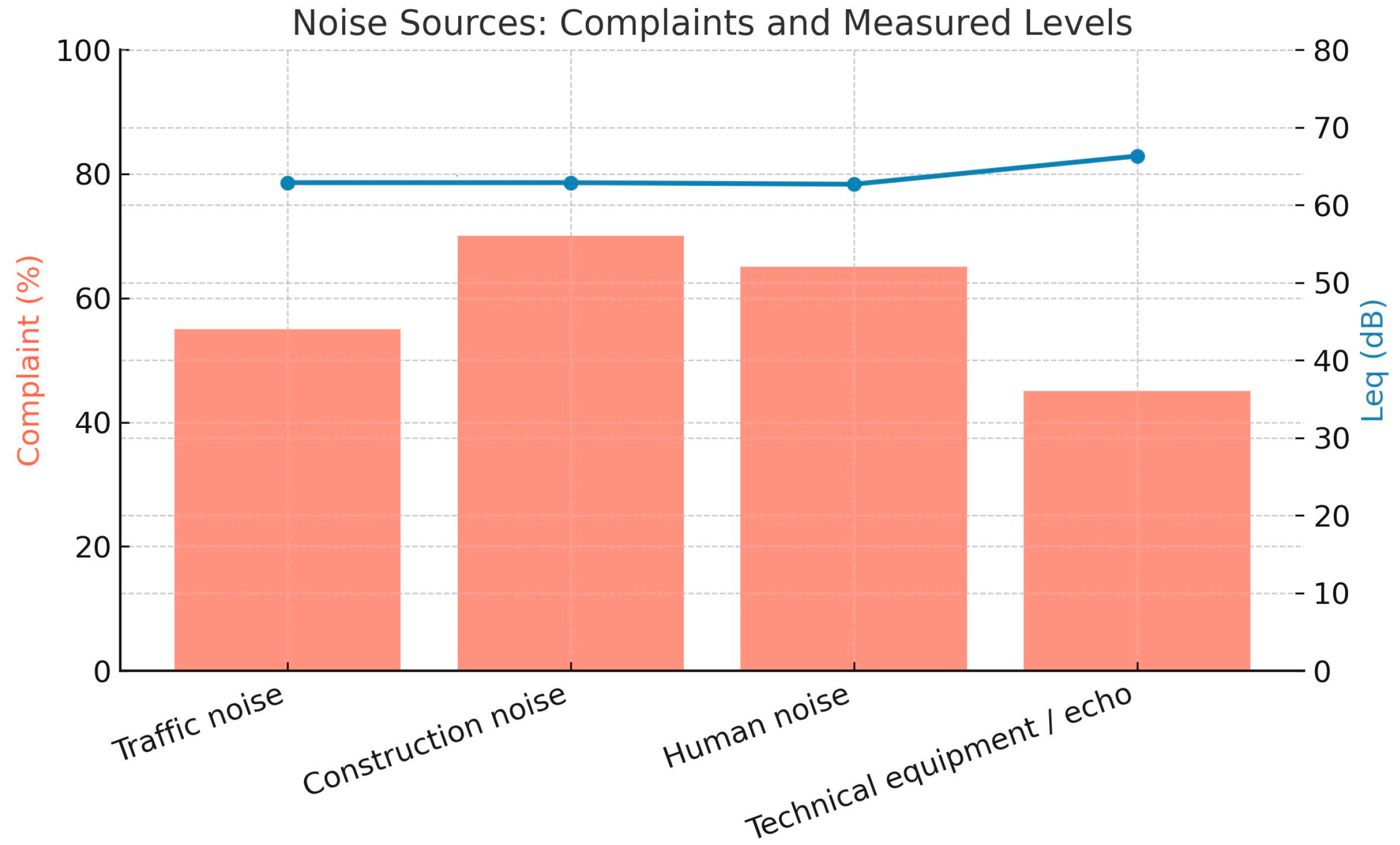

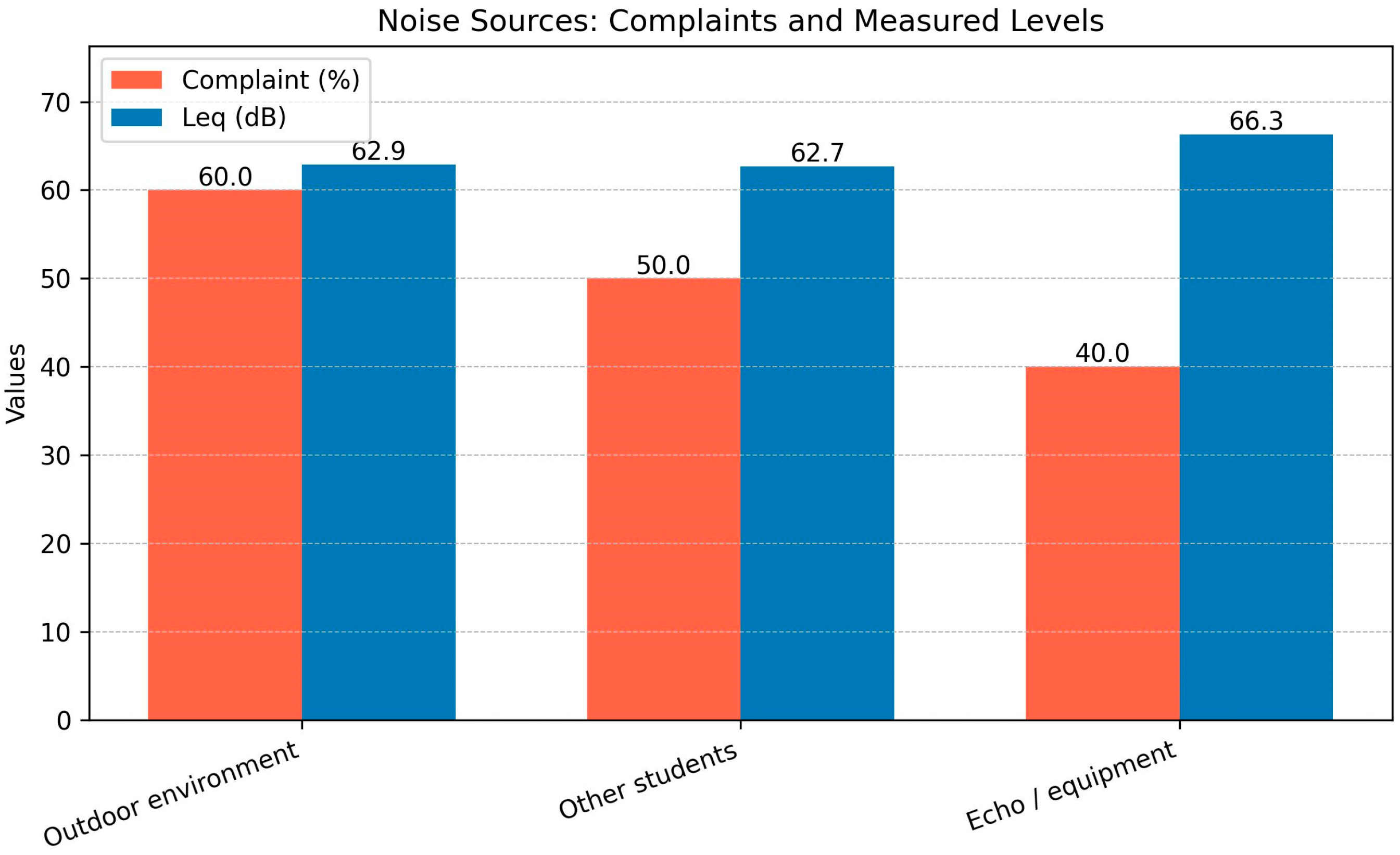

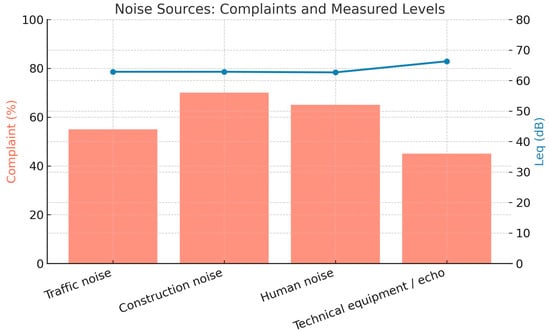

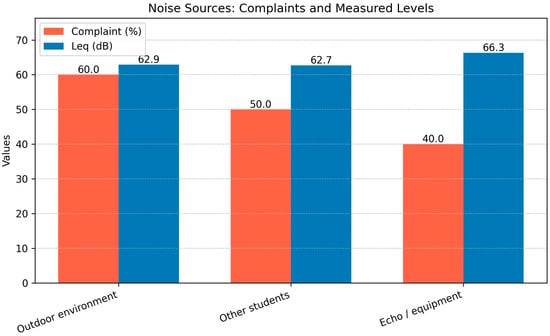

According to the survey results, the most disturbing types of noise for participants were, in order: construction noise (70%), human voices (65%), vehicle traffic (55%), and technical equipment/echo (45%) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Types of noise sources.

According to the survey results, participants reported being most bothered by construction noise (70%) and human voices (65%). Vehicle traffic was found to be disturbing at a rate of 55%, while technical equipment/echo was found to be disturbing at a rate of 45%. When the measurements were examined, the average Leq values corresponding to these noise types ranged between 62.6 and 66.3 dB(A).

Chi-square test: χ2 = 6.28, p = 0.099 → Not significant Correlation: r = −0.831 → Strong negative correlation (high dB(A) does not always cause high discomfort). The results of the chi-square test indicate that the differences in complaint rates between noise types are not statistically significant (χ2 = 6.28, p = 0.099). This suggests that the perceived annoyance levels between noise types are largely similar.

Correlation analysis revealed a strong negative relationship between the measured Leq values and complaint rates (r = −0.831). The result suggests that the level of discomfort depends not only on the intensity of the sound but also on the type of noise, its continuity, and individuals’ sensitivity to this sound.

In surveys, courtyards are one of the areas where noise is most intensely felt outdoors. Measurements (with/without students) were compared in the morning, afternoon, and evening. Paired t-test: t = 1.90, p = 0.197 → No statistically significant difference was found (p > 0.05).

The difference between student presence and noise level in the morning 21.8 dB (A) is quite high and can be explained by entry–exit traffic and outdoor interaction. The difference is lower in the afternoon and evening, and it is observed that outdoor noise is relatively high even when students are not present during these hours (Table 11).

Table 11.

Survey results.

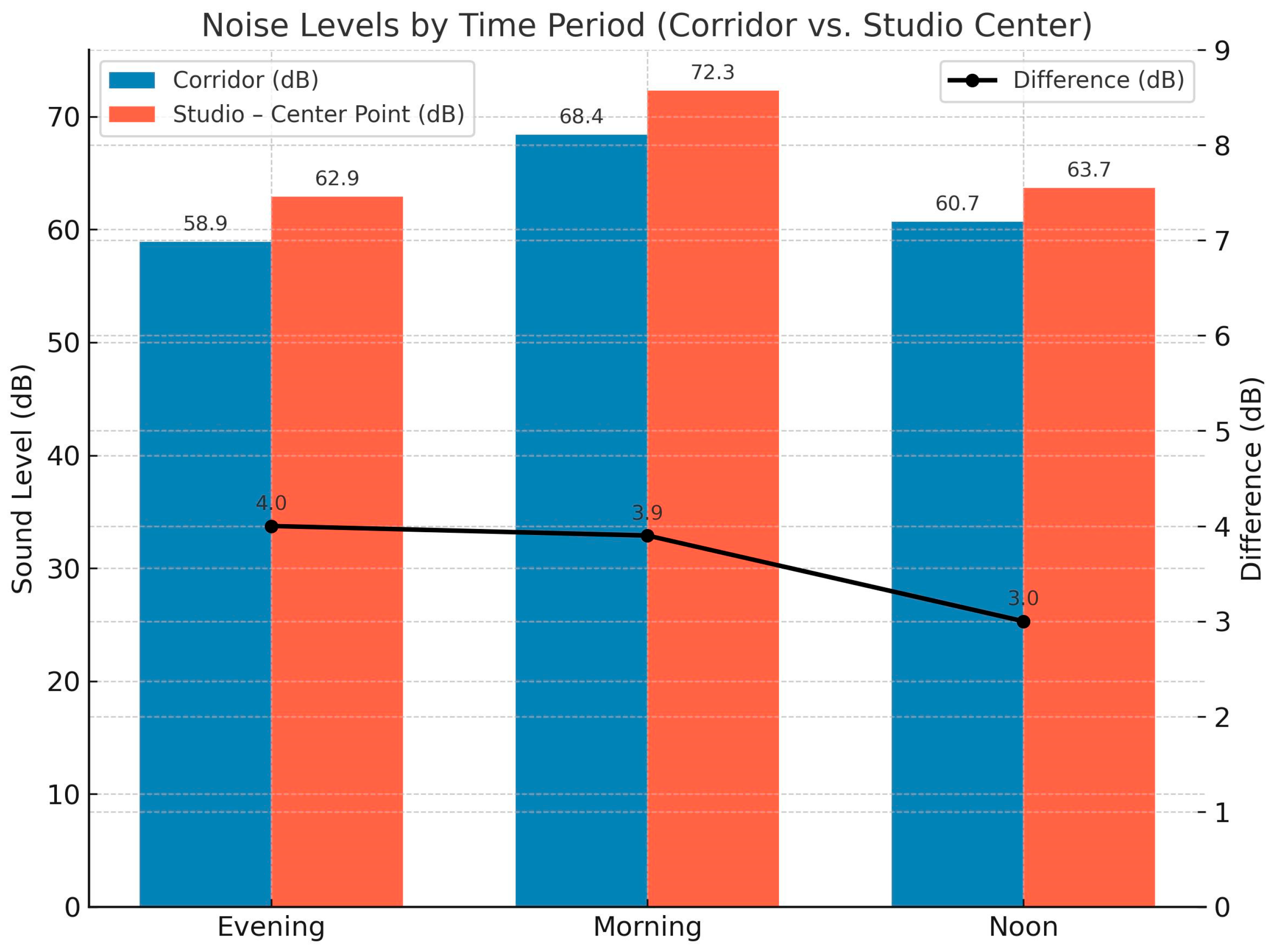

Studio (midpoint) and corridor measurements were compared. One-way ANOVA: F = 0.357, p = 0.611 → No statistically significant difference between the two locations. Post hoc Tukey test: No significant difference was found in the midpoint–corridor comparison; confidence intervals indicate that the difference may be zero.

Although studio (70%) and corridor (65%) emerged as spaces causing high levels of discomfort in the survey data, no significant difference was detected in terms of the measured average Leq values (Figure 7). This suggests that the perception of discomfort is related not only to sound intensity but also to factors such as the type of sound, its continuity, and the acoustic properties of the space.

Figure 7.

Number of students disturbed by noise in the venues.

R2 = 0.706 → The model explains 70% of the variation in the discomfort percentage.

Coefficient (Leq): −4.12 → When the measured sound level increases by 1 dB (A), the discomfort percentage decreases by approximately 4.1% (the finding is unexpected).

p-value = 0.365 → Not statistically significant.

According to the survey results, the most disturbing noise source in classrooms and studios is outdoor noise (60%), followed by other students’ conversations (50%) and echo/plumbing noises (40%). When these perceptions are compared with measurement data, it is observed that the average Leq values measured for the external environment (courtyard) and other students (corridor) are quite close to each other (62.8 dB and 62.6 dB(A). The studio midpoint measurements associated with echo/plumbing, on the other hand, have a relatively higher average noise level 66.3 dB(A) (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Noise sources complaints and noise levels.

Multiple regression analysis shows that the measured noise levels explain 70% of the variation in the discomfort percentage (R2 = 0.706). However, the fact that the obtained coefficient is negative (a decrease in the percentage of discomfort as Leq increases) and the p-value is not statistically significant (p = 0.365) indicates that noise perception cannot be explained solely by sound intensity. The situation indicates that participants have different sensitivities to certain types of noise and that noise perception may be influenced by acoustic parameters such as frequency content, continuity, and predictability, as well as the reverberation characteristics of the space.

For example, despite having high dB(A) values, echo/plumbing noise has a lower discomfort rate, suggesting that steady, continuous, and low-frequency sounds may be perceived as less annoying than fluctuating and sudden noise sources. Similarly, even if dB(A) levels are similar for outdoor and student-generated noise, speech sounds involving social interaction may have a more detrimental effect on psychological and cognitive attention.

Therefore, these findings highlight the need to formulate strategies that address not only the reduction in noise levels but also the enhancement of noise characteristics and acoustic comfort, from both architectural acoustic design and noise management perspectives.

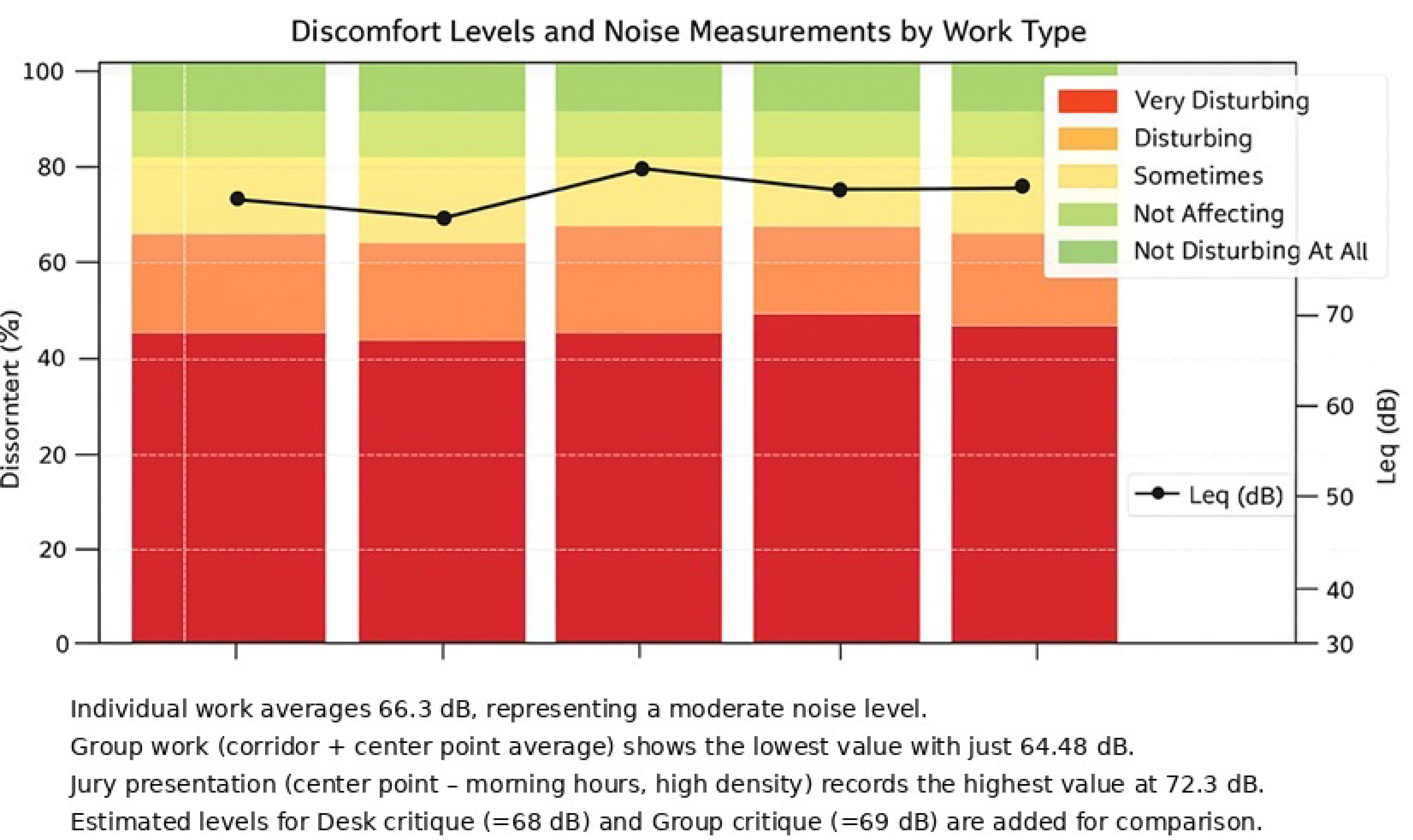

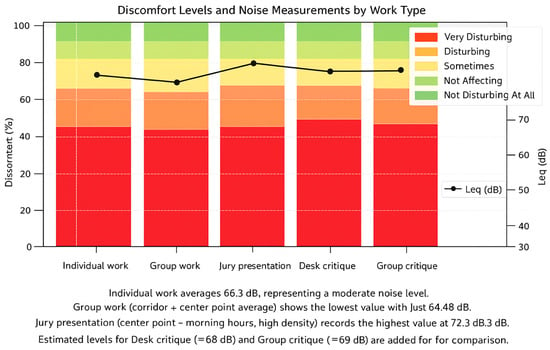

While 70% of the students stated that the most disturbing way of working in the studios in terms of noise was group work, 65% of them stated that the in-class humming disturbed them during group critiques and 60% of them stated that the in-class noise did not disturb them during table critiques (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Noise disturbance levels of students according to work types.

Individual work has a medium noise level of 66.3 dB(A) on average.

Group work (corridor + midpoint average) shows the lowest value at 64.4 dB(A).

The jury presentation (midpoint—morning hours, high density) shows the highest value at 72.3 dB(A).

These values suggest that noise levels increase significantly in events requiring high participation and high speech density, such as juries, while remaining more balanced in group work.

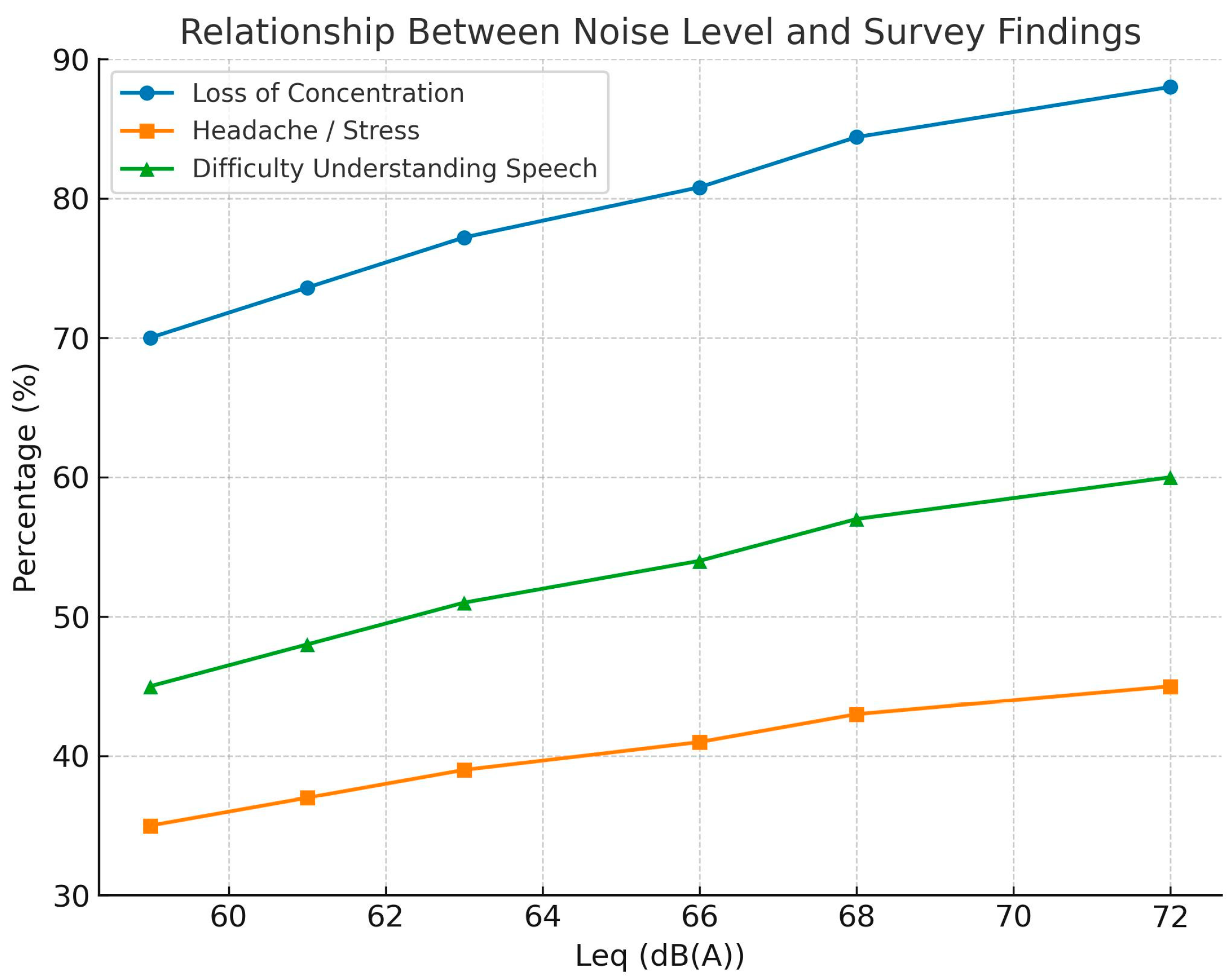

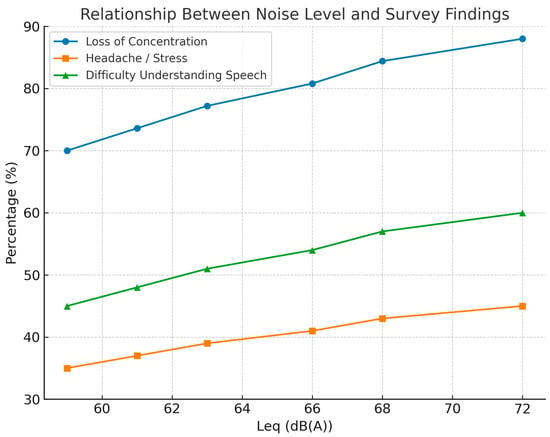

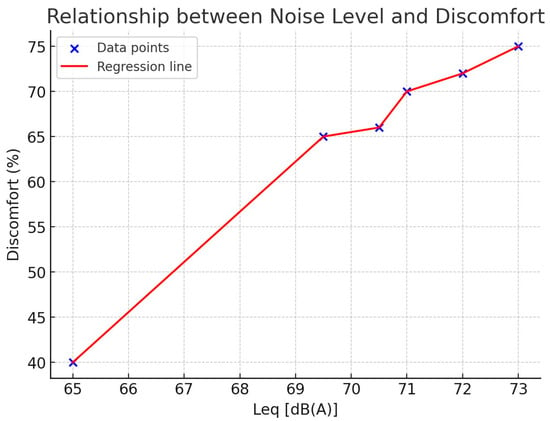

When the relationship between noise level and perceived negative effects was examined, concentration loss (88%), difficulty understanding conversations (60%), and fatigue (52%) emerged as the most frequently reported issues. A Pearson correlation analysis performed on the mean noise levels and corresponding discomfort percentages yielded a high correlation coefficient (r = 0.966), indicating a strong directional alignment between the two variables. However, this value should be interpreted cautiously, as it is based on a limited number of aggregated data points, which may inflate the apparent strength of the relationship. The determination coefficient (R2 = 0.933) suggests that noise level accounts for approximately 93% of the variance in the reported effects within this dataset, and the slope value (8.94) indicates that each 1 dB(A) increase in noise level is associated with an approximate 8.94% increase in the reported negative effect rate. Although the p-value (0.167) does not indicate statistical significance at conventional thresholds, the overall pattern highlights a consistent trend: as noise levels rise, reports of concentration loss, communication difficulties, and physiological discomfort also increase. These results reinforce the need to maintain Leq values below 60 dB(A) in design studios to support students’ cognitive performance and acoustic comfort (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The effect of noise on students.

The survey results revealed significant physical and cognitive impacts of noise exposure in design studios. The most frequently reported outcome was loss of concentration (88%), indicating that continuous background chatter and reverberation severely challenge selective attention and contribute to cumulative mental fatigue during long studio sessions. Such distraction is directly associated with design errors, flawed decision-making, and increased workload due to repeated tasks.

Difficulty in understanding speech (60%) was another major effect, highlighting the decline in verbal communication quality. Students reported that during desk or group critiques, information loss and misunderstandings were common, often leading to a cycle of repeated explanations, raised voices, and consequently higher overall noise levels.

Fatigue (52%) was reported as a physiological manifestation of prolonged exposure. Decreased performance and motivation were especially pronounced in afternoon sessions, while jury weeks amplified these negative outcomes.

In addition, headache and stress (45%) were identified by nearly half of the participants as a consequence of noise exposure. The finding emphasizes that noise not only affects cognitive performance but also undermines physical health and psychological resilience, potentially contributing to longer-term issues such as burnout, anxiety, and reduced learning efficiency.

Taken together, these results confirm that noise in design studios extends beyond an environmental nuisance, producing measurable physical, psychological, and academic consequences for students.

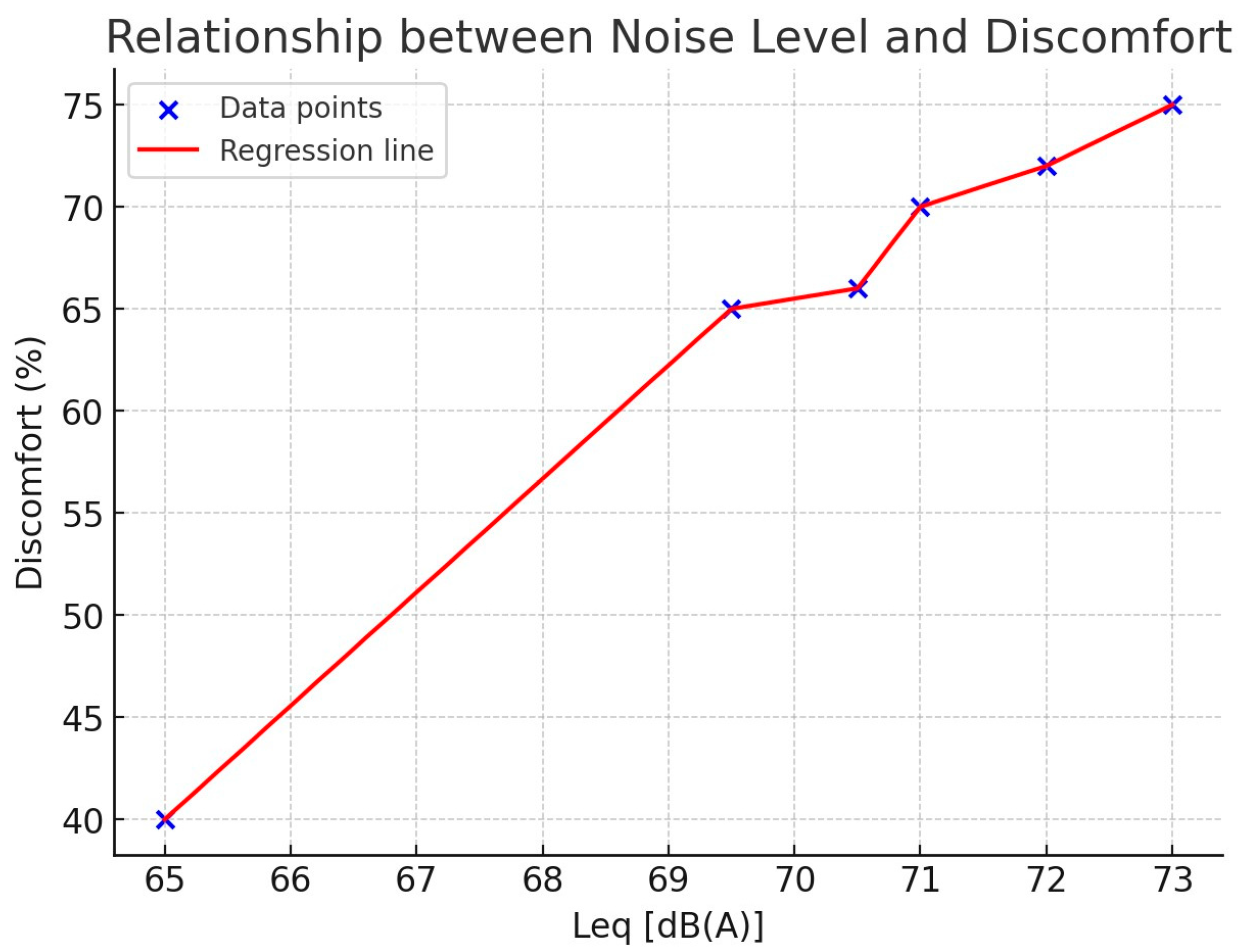

A strong and significant correlation was found between noise levels measured by survey results (r = 0.99, p < 0.001). According to simple linear regression analysis, each 1 dB(A) increase increases the rate of discomfort reported by students by approximately 4.5% (R2 = 0.986). The result confirms that levels measured during group critiques and jury sessions, specifically 70–73 dB(A), are found to be highly disturbing by students (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Relationship between noise level and discomfort.

4. Discussion

The statistical analyses showed that there were no significant week-to-week differences in LAeq values over the 14-week measurement period (p > 0.05). Although the effect sizes (η2) were within the small to medium range, indicating some variability in acoustic conditions, these differences did not reach statistical significance. The finding also brings an important methodological implication. Moreover, the absence of statistically significant fluctuations supports the conclusion that, despite perceptual differences reported by students in the survey responses, the noise levels observed in Studio 130 remained relatively stable throughout the semester.

The questionnaire used in this study was developed by drawing on similar studies in the literature [13,25], and content validity was ensured through expert feedback. Nevertheless, to enable cross-case comparability, future studies should employ internationally validated survey tools. In the study, in line with the data obtained from the questionnaires applied to 192 interior architecture students; it was determined that the noise level increased as the number of students in the studios increased. Students stated that they were negatively affected by these increased noise levels. Noise causes cognitive and psychological problems such as distraction, loss of concentration, stress, fatigue and decreased creativity, reducing overall satisfaction. Although some students reported that they were not bothered by higher noise levels, this did not appear to have a positive impact on overall satisfaction. These findings are in parallel with the results of the studies conducted by [55,56]. As stated in the research of [57], high noise levels in interior design studios can cause health problems such as restlessness, headaches, high blood pressure and stress. Auditory communication is a critical element for academic success and has direct effects on learning engagement and cognitive performance. In the context of interior architecture education, these negative effects of noise are particularly critical. Unlike traditional classrooms, design studios rely heavily on studio culture, collaborative projects, and critique-based pedagogy. Noise not only reduces auditory comfort but also directly undermines communication and interaction, which are essential for creativity, design thinking, and active participation in the studio environment.

The results of the noise measurements made in the courtyard, corridor and studio centre in the morning, noon and evening hours, both when the studio is full and when it is empty, and the results of the questionnaires applied to the students in the studio number 130 of Afyon Kocatepe University Department of Interior Architecture and Environmental Design were evaluated together. In the measurements made when the studio was empty; the intensity of the sounds coming from the courtyard, especially at noon, is due to the increase in student traffic during these hours. In the morning hours, the location where noise is measured at the lowest level is in the center of the studio, which is due to the low level of circulation inside the building during this time period and the relatively isolated location of the studio. In this context, the fact that the lowest noise level is measured in the studio during the morning hours and when students are not present indicates that the main cause of the increase in noise inside the building is the activities that occur during classes.

The measurements made during the hours when the students are in the studio show that the noise level is the highest in the morning and in the studio centre. The main reason for this is that design courses are mostly held in the morning and different interactive learning methods such as group work, table and general critique are preferred in these courses.

The measured noise levels in Studio 130 consistently exceeded the thresholds recommended by the World Health Organization, which are 35 dB(A) for classrooms and 55 dB(A) for outdoor environments. The fact that the measured values reached up to 72.3 dB(A) during jury presentations and 66.3 dB(A) during individual work highlights that the acoustic conditions in the design studio significantly surpass acceptable international standards, thereby posing potential risks for students’ cognitive performance and well-being.

According to [39], it was observed that the limits of 35 dB(A) recommended by the World Health Organization for classrooms and 55 dB(A) for outdoor spaces were exceeded. Prolonged exposure of students to loud noise negatively affects their auditory health, cognitive capacity and psychological well-being. Unfortunately, many interior architecture studios lack adequate acoustic solutions and this situation prevents students from adapting to the studio culture and actively participating in the design processes. Noise was found to reduce the quality of the activities carried out in the studio environment and to cause serious problems, especially in terms of speech intelligibility. For example, the inability to hear the information given by the trainers clearly reduces the efficiency of the training. The drawing sounds and conversations that occur during individual work cause buzzing in the environment, which makes it difficult to understand the conversations and creates effects such as fatigue, headache and distraction on users. The lack of auditory comfort is exacerbated by the fact that users have to raise their voices because they cannot hear each other.

Previous research confirms that annoyance depends not only on sound levels but also on noise type and individual sensitivity. Refs. [20,58] showed that similar LAeq values may produce different annoyance levels depending on the acoustic characteristics. Reference [59] highlights that intermittent and impulsive sounds are more disturbing than continuous background noise, while [23] emphasized that meaningful speech is perceived as more annoying than meaningless background murmurs. These findings align with the present study, where 60% of students reported difficulty in understanding speech. Furthermore, ref. [60] indicated that personal sensitivity influences annoyance levels, which corresponds with survey responses showing that some students were less disturbed by noise despite elevated levels. In this context, the measured values—72.3 dB(A) during jury presentations and 66.3 dB(A) during individual work—illustrate how similar sound levels can lead to varying annoyance depending on teaching mode and individual tolerance.

In comparison with the existing literature, our results show both overlaps and distinctions. In classrooms, background noise exceeding 35 dB(A) has been reported to reduce speech intelligibility and concentration [23], while in open-plan offices noise levels around 60–70 dB(A) has been associated with cognitive fatigue and reduced performance [61]. Our findings in the design studio context, with LAeq values ranging from 66 to 72 dB(A), align with these thresholds but also reveal studio-specific challenges such as impaired participation in critiques and reduced creativity. Unlike most previous studies, which were limited to short-term measurements or single-event observations, this research provides a longitudinal dataset over 14 weeks combined with survey evidence from 192 students. The dual methodology constitutes the study’s main originality, demonstrating how noise undermines the collaborative and critique-based pedagogy that defines interior architecture studios.

In order to strengthen the universality of the findings, the results of this study were also contextualized with international cases examining different teaching modes and their associated noise tolerance thresholds. For instance, research conducted in European architecture schools has shown that group-based critiques and collaborative studio activities often raise students’ tolerance thresholds compared to traditional classrooms, although this does not prevent cognitive fatigue [13,20]. Similarly, studies from Asian universities reveal that students engaged in socially interactive and applied design courses exhibit higher tolerance towards peer-generated noise, yet still report significant difficulties in sustaining concentration [16,17]. In contrast, Scandinavian case studies emphasize that in individual work sessions, exceeding the WHO’s recommended 35 dB(A) classroom threshold significantly reduces learning efficiency and leads to psychological stress [16]. When compared with our results—where noise levels reached 72.3 dB(A) during jury presentations and 66.3 dB(A) in individual work—the similarities and differences highlight that noise tolerance is strongly shaped by pedagogical modes of teaching. Therefore, linking our findings with these international cases underscores the global relevance of auditory comfort in design education and supports the argument that design studios require distinct acoustic strategies beyond those developed for conventional classrooms.

The findings of this study clearly demonstrate the adverse effects of noise on students’ experiences and learning outcomes in design studios. The average LAeq value of 65 dB(A) recorded when students were present exceeds the [58] recommended limit of 35 dB(A) for educational environments and does not comply with the acoustic comfort criteria set by [62]. This is consistent with the findings of [23,59], who reported that classroom noise levels above 60 dB(A) significantly impair attention and reading comprehension.

The survey results further reinforce this trend: 88% of students reported concentration problems, 72% reported decreased productivity, and 60% reported communication difficulties. These findings resonate with [58], who emphasized the role of individual noise sensitivity in determining cognitive performance. Moreover, the high prevalence of communication problems and physiological discomfort supports the observations of [16], who found that noise reduces speech intelligibility and induces stress responses in educational settings.

The results also align with the conclusions of [20,57], who highlighted that similar noise levels may produce different levels of annoyance depending on the nature of the noise and individual susceptibility. This suggests that while some students may display greater tolerance to noise, the overall impact on the learning environment remains predominantly negative. Therefore, the present study not only corroborates findings documented in the international literature on classroom acoustics but also contributes new empirical evidence by providing long-term measurements and perception data from the unique context of design studios.

The findings of this study reveal that interior design studios demand distinct approaches to auditory comfort in comparison with traditional classrooms. Following the recommendations of [15] strategies including the reorganization of layouts, reinforcement of sound insulation, and the introduction of noise barriers become essential. Furthermore, reducing noise requires not only careful material choices but also tailored spatial interventions, such as wooden coverings, operable window systems, and acoustic ceiling applications. Such acoustic interventions are known to contribute positively to students’ academic achievement.

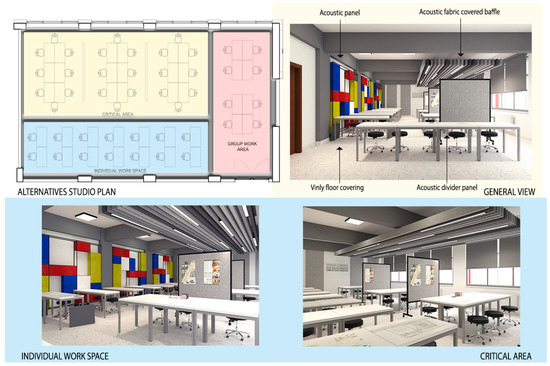

In this framework, some suggestions are presented to improve the auditory comfort of design studio 130. An organization that allows for collaborative work and at the same time ensures voice privacy can increase efficiency and user satisfaction. Revisions to construction materials can help to reduce noise levels while maintaining the visual and collaborative advantages of the open plan. An acoustically effective arrangement requires the covering of floor, ceiling and wall surfaces with suitable materials and the use of panels that prevent sound transmission between work groups. These boards facilitate noise control by providing acoustic shade and function as surfaces where students can exhibit their work. In this context, the design studio 130 has been redesigned with a new interior layout suitable for different working styles and supporting auditory comfort, and the proposed plan scheme is presented below (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Alternative studio plan and suggestions for space design.

The proposed design solutions for Studio 130 include vertical acoustic panels, fabric-wrapped ceiling baffles, resilient vinyl flooring, and acoustic ceiling treatments, each contributing to noise reduction through distinct acoustic mechanisms. Vertical panels with NRC values of 0.95–1.00 [63] act as high-performance absorbers, interrupting direct sound paths and providing localized absorption. The configuration improves the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and speech transmission index (STI), thereby reducing distraction between groups and enhancing speech privacy. Fabric-wrapped ceiling baffles, with NRC values of 0.80–0.85 [64], increase the effective absorption area of the ceiling. According to Sabine’s formula (RT60 = 0.161·V/A), this additional absorption capacity reduces reverberation time, leading to improved speech intelligibility and reduced auditory fatigue.

Resilient vinyl flooring with laboratory ΔLw values of 15–20 dB [65] effectively minimizes impact-borne noise transmission. By attenuating footfall and chair movement sounds, it reduces low-frequency disturbances that would otherwise propagate across the studio. Similar results have been reported for Tarkett products (ΔLw ≈ 20 dB) and Forbo Sarlon Acoustic vinyls (15–19 dB) [65,66,67,68]. Acoustic ceiling panels further contribute to overall absorption, lowering background noise levels by approximately 6–8 dB in open-plan conditions [64]. Collectively, these interventions directly address both airborne and structure-borne noise, improving overall auditory comfort.

In terms of feasibility, partition panels are relatively low-cost, modular, and easily reconfigurable, though their placement requires careful consideration of circulation patterns. Ceiling baffles and acoustic panels involve higher investment and require coordination with lighting and HVAC systems, while resilient vinyl flooring is durable and effective but necessitates the replacement of existing surfaces, which entails additional cost and temporary disruption.

Based on these principles, a conceptual redesign of Studio 130 was developed (Figure 11). Group work areas were organized with semi-enclosed acoustic panels, baffles were positioned above critique zones to maintain RT60 values below 0.8 s in the 500–2000 Hz octave bands, and resilient flooring was applied throughout the studio. The integrated scheme balances openness with voice privacy, ensuring both collaborative learning and speech clarity. While the present study refrains from claiming material performance without in situ validation, it outlines a framework for future measurement using standardized metrics such as STI/STIPA (IEC 60268-16: 2020 [62]), SNR, and octave-band reverberation time (ISO 3382-2; open-plan descriptors per ISO 3382-3) [69,70,71,72]. In this way, design implications remain aligned with measurable acoustic indicators and pedagogical requirements of interior architecture education.

5. Conclusions

The main contribution of this study is to demonstrate that noise levels in studio environments frequently exceed the 35 dB(A) limit recommended by the World Health Organization for classrooms, thereby negatively affecting speech intelligibility, concentration, and collaborative learning processes. Unlike shorter-term and classroom-oriented studies, this research highlights the specific conditions and challenges of critique-based studio education. A key novelty of the study lies in its dual-method approach, combining 14 weeks of continuous, standards-compliant noise measurements with student perceptions, and contextualizing these findings through comparisons with international data from classrooms, open-plan offices, and studio environments. This integrated approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of how noise impacts learning performance in design-based education. Furthermore, the proposed interventions (partition elements, ceiling treatments, flooring solutions) offer not only spatial adjustments but also practical guidelines aimed at enhancing learning efficiency and improving acoustic comfort.

Although the proposed interventions are primarily presented with reference to material specifications and theoretical NRC/ΔL_w values, they are deliberately framed as preliminary, adaptable, and context-sensitive design strategies rather than prescriptive solutions. Their practical feasibility can be supported through several considerations. First, modular partition panels and acoustic elements represent low-cost, reconfigurable solutions suitable for institutions with budget limitations. Second, interventions such as ceiling baffles or resilient flooring, while requiring a higher initial investment, provide durable improvements that enhance both acoustic comfort and overall indoor environmental quality. Third, phased or modular implementation allows institutions to adopt solutions incrementally in accordance with available resources. Therefore, the recommendations in this study should be interpreted as flexible and scalable design guidelines that can be adapted to diverse educational contexts. Future studies should include cost–benefit analyses and post-occupancy evaluations to empirically validate the effectiveness of these interventions in real studio environments.

Beyond the spatial interventions, the findings also offer theoretical principles that can be integrated into the pedagogical framework of interior architecture education. In studio-based pedagogy, noise should be considered not only an environmental comfort parameter but also a pedagogical variable directly influencing learning outcomes. As such, studio guidelines could define acoustic threshold values (e.g., ≤60 dB(A)) for different activity modes—individual work, group discussions, and jury sessions—providing instructors and students with clear reference criteria. Embedding curricular content related to acoustics and environmental comfort into studio teaching may further enhance students’ competencies in design practice and their awareness of indoor environmental quality.

In conclusion, this study contributes to the growing body of research on acoustic comfort in design studios by offering both empirical evidence and pedagogical implications. The findings emphasize the necessity of integrating acoustic considerations into interior architecture education and provide valuable guidelines for educators, designers, and policymakers aiming to create healthier and more efficient learning environments in studio-based settings.

6. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the research was conducted exclusively in Studio 130 at Afyon Kocatepe University, which shares similar physical characteristics (e.g., size, height, orientation) with other studios in the department. While this consistency supports the internal coherence of the field study, it also means that the findings should be regarded as a pilot case study rather than results that can be directly generalized to all design studios or universities. Nevertheless, because many design studios exhibit comparable spatial and pedagogical features—such as open-plan layouts, critique-based learning processes, tool use, and intensive peer interaction—the results remain informative for similar educational contexts.

Second, the measurements and surveys were carried out within a specific 14-week period and with a limited student sample, which constrains the temporal and demographic breadth of the dataset. Third, although the survey instrument was adapted from previous research, reviewed by experts for content validity, and demonstrated strong internal consistency (α = 0.87), it is not an internationally validated scale; therefore, the interpretation of the findings should take this methodological limitation into account. Additionally, certain external factors—such as fluctuations in outdoor noise associated with meteorological conditions—could not be fully controlled during the measurement period.

Future research should involve multi-institutional studies, larger and more diverse student samples, and internationally validated measurement tools to strengthen external validity, enhance cross-context comparability, and broaden the generalizability of the findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.O. and Ş.E.O.; methodology, B.O., Ş.E.O., S.M., F.M. and M.Ç.; validation, B.O., Ş.E.O., S.M., F.M. and M.Ç.; formal analysis, S.M. and F.M.; investigation, B.O. and M.Ç.; resources, B.O. and M.Ç.; data curation, Ş.E.O., B.O. and S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Ş.E.O., B.O., S.M., F.M. and M.Ç.; writing—review and editing, Ş.E.O., B.O. and S.M.; visualization, F.M.; supervision, Ş.E.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Şimşek, O. Noise control in classrooms: An examination through a case study. Eksen Dokuz Eylül Univ. Fac. Archit. J. 2021, 2, 34–51. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment and Urbanization. Regulation on the Protection of Buildings Against Noise. Official Gazette. 2017. Available online: https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=23616&MevzuatTur=7&MevzuatTertip=5 (accessed on 9 December 2025). (In Turkish)

- Guo, W.; Wang, L.; Caneparo, L. Research on the Factors That Influence and Improve the Quality of Informal Learning Spaces (ILS) in University Campus. Buildings 2024, 14, 3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Tian, M.; Zhang, Y. Assessing Acoustic Conditions in Hybrid Classrooms for Chinese Speech Intelligibility at the Remote End. Buildings 2025, 15, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Ye, H.; Guo, Q.; Shan, J.; Huang, Z. A Perceptual Assessment of the Physical Environment in Teaching Buildings and Its Influence on Students’ Mental Well-Being. Buildings 2024, 14, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jokhadar, A.; Alnusairat, S.; Abuhashem, Y.; Soudi, Y. The impact of indoor environmental quality (IEQ) in design studios on the comfort and academic performance of architecture students. Buildings 2023, 13, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilmez, D.H.; Çelik, K.; Diri, C.; Arpacıoğlu, Ü. Evaluation of architectural studios in terms of acoustic comfort conditions: The case of Çukurova University Architecture Department YADYO Studio. J. Archit. Sci. Appl. 2022, 7, 852–870. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, R.; Jennings, P.; Poxon, J. The development and application of the emotional dimensions of a soundscape. Appl. Acoust. 2013, 74, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wålinder, R.; Gunnarsson, K.; Runeson, R.; Smedje, G. Physiological and psychological stress reactions in relation to classroom noise. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2007, 33, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoyeh, I.I.; Ezezue, A.M.; Ezennia, S.I.; Irouke, V.M.; Aniegbuna, A.I. A review of the impact of noise pollution on students in architecture studios in universities. Int. J. Adv. Res. Innov. Ideas Educ. 2024, 10, 2060–2068. [Google Scholar]

- IEC 61672-1; Electroacoustics—Sound Level Meters—Part 1: Specifications. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- IEC 60942; Electroacoustics—Sound Calibrators. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Wen, S.; Gan, W.S.; Wang, M. Investigation on the performance of an active noise control window system mounted on the top-hung window of a residential room. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 206, 109323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurra, S. Environmental Noise and Its Management, Volumes I-III; Bahçeşehir University Publications: Istanbul, Türkiye, 2009. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, E.; King, E.A. Environmental Noise Pollution: Noise Mapping, Public Health, and Policy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; p. 283. [Google Scholar]

- Firdaus, S.; Anwar, A.I.; Khan, A.A.; Ahmed, Z.; Anjum, R. A comprehensive review of adverse effect of noise pollution on human health and its prevention. Eur. J. Biomed. 2020, 7, 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L.T.; Oliveira, I.S.; Silva, J.F. The impact of urban noise on primary schools: Perceptive evaluation and objective assessment. Appl. Acoust. 2016, 106, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansfeld, S.A.; Matheson, M.P. Noise pollution: Non-auditory effects on health. Br. Med. Bull. 2003, 68, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafavi, A.; Cha, Y.J. Deep learning-based active noise control on construction sites. Autom. Constr. 2023, 151, 104885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basner, M.; Baisch, W.; Davis, A.; Brink, M.; Clark, C.; Janssen, S.; Stansfeld, S. Auditory and non-auditory effects of noise on health. Lancet 2014, 383, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tang, B.; Liu, T.; Xiang, H.; Sheng, O.; Gong, H. Modeling traffic noise in a mountainous city using artificial neural networks and gradient correction. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 78, 102136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Yan, A.; Liu, K. What is noise-induced hearing loss? Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2019, 80, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shield, B.; Dockrell, J. The effects of noise on children at school: A review. Build. Acoust. 2003, 10, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halonen, J.I.; Dehbi, H.M.; Hansell, A.L.; Gulliver, J.; Fecht, D.; Blangiardo, M.; Kelly, F.J.; Chaturvedi, N.; Kivimäki, M.; Tonne, C. Associations of night-time road traffic noise with carotid intima-media thickness and blood pressure: The Whitehall II and SABRE study cohorts. Environ. Int. 2017, 98, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, E.F.; Morales, F.C. Construction and validation of questionnaire to assess recreational noise exposure in university students. Noise Health 2014, 16, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachokostas, C.; Achillas, C.; Michailidou, A.V.; Moussiopoulos, N. Measuring combined exposure to environmental pressures in urban areas: An air quality and noise pollution assessment approach. Environ. Int. 2012, 39, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onay, B.; Bayazıt Solak, E.; Sava, B.; Şahin, C. A study on the evaluation of noise in the central campus of Afyon Kocatepe University. TUBİD 2024, 5, 1–11. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Polat, S.; Buluş Kırıkkaya, E. Effects of noise on the educational environment. In Proceedings of the 13th National Educational Sciences Congress, Malatya, Türkiye, 6–9 July 2004. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Erol, H.B. Acoustic Performance Criteria in the Use of Materials in Interior Spaces. Master’s Thesis, Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, Institute of Science, Istanbul, Türkiye, 2006. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Demirarslan, D.; Demirarslan, K.O. An interdisciplinary approach in the design of interior spaces in the context of environmental awareness: The relationship between interior architecture and environmental engineering. J. Nat. Disasters Environ. 2017, 3, 112–128. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulunuz, M.; Orbak, A.Y.; Bulunuz, N. Noise Pollution in Schools: Causes, Effects and Control; Bursa Uludağ University Publications: Bursa, Türkiye, 2021. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Avşar, Y.; Gönüllü, M.T. Evaluation of indoor and outdoor noise in some schools in terms of educational quality: The case of Istanbul. In Proceedings of the GAP 2000 Symposium, Şanlıurfa, Türkiye, 16–18 November 2000; pp. 16–18. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Bulunuz, N.; Bulunuz, M.; Orbak, A.Y.; Mutlu, N.; Tavşanlı, Ö.F. An evaluation of primary school students’ views about noise levels in school. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2017, 9, 725–740. [Google Scholar]

- Long, M. Architectural Acoustics; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Onay, B.; Şahin, C. A study on the analysis of noise in educational institutions and their surroundings in the city center of Isparta. Turk. J. For. Sci. 2022, 6, 457–479. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güremen, L. A study on the evaluation of the effects of indoor and outdoor auditory comfort conditions in primary schools on users: The case of Amasya. E-J. New World Sci. Acad. 2012, 7, 580–604. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment and Forestry. Regulation on the Assessment and Management of Environmental Noise (2002/49/EC). Official Gazette. 2010. Available online: https://www.tummer.org.tr/turcevCMS_V2/files/%C3%87EVRESEL%20G%C3%9CRLT%C3%9CN%C3%9CN%20DE%C4%9EERLEND%C4%B0R%C4%B0LMES%C4%B0%20VE%20Y%C3%96NET%C4%B0M%C4%B0%20Y%C3%96NETMEL%C4%B0%C4%9E%C4%B0.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025). (In Turkish).

- Cavanaugh, W.J.; Wilkes, J.A. (Eds.) Architectural Acoustics: Principles and Practice; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Özçevik, A. Auditory Comfort Requirements in Architectural Design Studios and a Case Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Anadolu University, Eskişehir, Türkiye, 2005. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Egan, M.D. Architectural Acoustics, 2nd ed.; J. Ross Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Demirbaş, O.Ö. Design Studio as a Life Space in Architectural Education: Privacy Requirements. Master’s Thesis, Bilkent University, Institute of Science, Ankara, Türkiye, 1997. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Onur, D.; Zorlu, T. The Relation Between the Training Methods Applied in Design Studios and the Creativity. Turk. Online J. Des. Art Commun. 2017, 7, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D. The Design Studio: An Exploration of Its Traditions and Potential; RIBA Publications: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ketizmen, G. Investigation of Methodological and Spatial Effects on the Formation of the Architectural Design Studio. Master’s Thesis, Anadolu University, Institute of Science, Eskişehir, Türkiye, 2002. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Hassanain, M.A.; Sanni-Anibire, M.O.; Mahmoud, A.S. Design quality assessment of campus facilities through post-occupancy evaluation. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2023, 41, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağatay, K.; Sönmez, M.Ç.; Dinçbaş, G.K. The effects of design studios and the heating system used on students’ perceptual evaluations. In Proceedings of the International Academic Research Congress, Ankara, Türkiye, 16–18 September 2019. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Çalış, M. Highway Noise and Economic Analysis of Noise Barriers. Master’s Thesis, Istanbul Technical University, Institute of Science, Istanbul, Türkiye, 2007. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Akten, M. Determination of the Existing Potentials of Some Recreation Areas in Isparta Province. Süleyman Demirel Univ. J. For. Fac. 2003, 4, 115–132. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Kalıpsız, A. Statistical Methods; Istanbul University Faculty of Forestry Publications No: 2837: Istanbul, Türkiye, 1981. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Karaman, Ö.Y.; Berber Üçkaya, N. Eğitim mekânlarında akustik konfor: Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Mimarlık Fakültesi örneği. Megaron 2015, 10, 503–521. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezz, M.S.; Mahdy, M.A.F.; Baharetha, S.; Hassanain, M.A.; Gomaa, M.M. Post occupancy evaluation of architectural design studio facilities. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11, 1549313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayides, P. Coefficient alpha: Interpret with caution. Eur. J. Psychol. 2013, 9, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Saccuzzo, D.P. Psychological Testing: Principles, Applications, & Issues; Wadsworth, Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pheng, H.S.; Yean, T.S.; Lye, K.H.; Ismail, A.I.M.; Kassim, S. Modeling noise levels in USM Penang campus. In Proceedings of the 2nd IMT-GT Regional Conference on Mathematics, Statistics & Applications, Penang, Malaysia, 13–15 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, G.S. A study of noise around an educational institutional area. J. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2006, 48, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Doygun, H.; Kuşat Gurun, D. Analysing and mapping spatial and temporal dynamics of urban traffic noise pollution: A case study in Kahramanmaraş, Turkey. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2008, 142, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, T.J. Synthesis of social surveys on noise annoyance. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1978, 64, 377–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. Environmental Noise Guidelines for the European Region; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289053563 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Belojevic, G.; Jakovljevic, B.; Stojanov, V. Noise and mental performance: Personality attributes and noise sensitivity. Noise Health 2001, 4, 77–89. [Google Scholar]