Abstract

While incorporating constructional columns into masonry walls enhances structural integrity, their seismic bearing capacity remains relatively low. In contrast, composite structures formed through the integration of large-section concrete columns with masonry walls can significantly improve seismic performance. This study employed an integrated approach of model testing and numerical analysis to investigate the seismic behavior of composite structures consisting of large-section reinforced concrete columns and brick masonry walls. Specifically, three scaled model tests were carried out, and finite element analysis (FEA) was performed on six full-scale models, with the aim of elucidating the failure mechanism and mechanical properties of such composite structures. The results show that concrete columns effectively inhibit crack propagation in the walls, and the bearing capacity and ductility of the composite structures are significantly enhanced. Furthermore, a formula for the calculation of the horizontal bearing capacity of the composite structures was proposed based on the failure modes observed in the tests. The bearing capacity of four types of composite structures is calculated, and the differences between the calculated results and the FEA results do not exceed 10%, which provides a reference for the calculation of the lateral bearing capacity of composite structures.

1. Introduction

Brick masonry structures were once among the most widely used structural forms for multi-story buildings in China during the 20th century. Traditional masonry structures, composed of brittle blocks bonded by mortar to serve as load-bearing and lateral-force-resisting members, exhibit relatively low load-carrying capacity and poor integrity. Consequently, they often sustain severe damage or even collapse during earthquakes [1,2,3,4,5]. The provision of ring beams and structural columns is an effective measure to improve the seismic performance of masonry structures [6,7,8]; reinforced concrete ring beams and structural columns not only enhance the integrity of masonry structures but also improve their collapse resistance. For the strengthening and retrofitting of existing masonry structures, the measure of adding ring beams and structural columns is frequently adopted. However, merely adding ring beams and structural columns results in limited improvement in the shear capacity of masonry structures; thus, the number of stories and height of buildings constructed in high seismic intensity zones are greatly restricted.

If a composite structure—integrating large-cross-section RC columns with masonry walls—is employed, it not only boosts the structural load-bearing capacity but also improves ductility. This enables the construction of multi-story public buildings in high seismic intensity areas. Investigating the seismic behavior of composite structures consisting of large-cross-section concrete columns and masonry walls can serve as a design foundation for newly constructed composite buildings in these high-risk regions, and also provide valuable references for the reinforcement design of existing multi-story masonry buildings.

Frame-infilled wall structures are composite systems composed of concrete frames and masonry infills. Although masonry infills are not intended to act as load-bearing components, they still exert a non-negligible influence on the seismic performance of the overall structure. Numerous studies [9,10,11,12,13,14,15] have demonstrated that masonry infills are capable of carrying a portion of the seismic shear force. Such a load-bearing behavior not only enhances the horizontal bearing capacity of the supporting concrete frame, but also improves the structure’s lateral stiffness, ductility, and energy dissipation capacity.

Massumi et al. [16] compared static and dynamic analyses to explore the cooperative working behavior between reinforced masonry infill walls (RMIWs) and reinforced concrete (RC) frames. They confirmed that RMIWs with supplementary reinforcement not only significantly enhance the lateral stiffness and bearing capacity of the frame structure but also improve the overall seismic performance of the latter via an efficient energy dissipation mechanism.

Teguh [17] conducted quasi-static tests to explore the effects of infill walls on frame structures, revealing that walls equipped with structural columns are prone to shear failure. Subsequently, finite element (FE) simulation was carried out to investigate the failure mechanism of infill walls, and the simulation results were in good agreement with the experimental data. This study provides a reliable reference for the FE analysis of the seismic performance of infill wall-frame.

Yuan S. C. et al. [18] performed quasi-static tests on three 1:1 full-scale steel frame models to investigate the seismic performance of steel frame-masonry infill hybrid structures. The test results demonstrated that, compared with the bare steel frame, the masonry infills increased the lateral stiffness to 3 times its original value and doubled the cumulative energy dissipation capacity under the same displacement amplitude. Furthermore, the simplified model that idealizes the masonry infill wall as a diagonal compression strut could effectively simulate the skeleton curve obtained from the structural tests.

Guo X. Q. et al. [19] employed a numerical analysis approach to investigate the cooperative working mechanism of concrete frame-reinforced block masonry hybrid structures under vertical loads, and accordingly proposed a calculation formula for axial force distribution.

Jiang L. X. et al. [20] studied the enhancement of seismic performance of masonry structures via the addition of reinforced concrete walls. They found that connection measures, such as bonded reinforcing bars, dowels, and tie bars, could ensure the coordinated work between the added reinforced concrete walls and the original masonry. This, in turn, resulted in a significant improvement in the bearing capacity, deformation capacity, and energy dissipation capacity of the masonry walls.

In existing literature, two common approaches have been adopted to improve the seismic performance of masonry-related structures. One involves strengthening the masonry infill walls of frames, which enhances the overall structural seismic performance but still relies on the reinforced concrete frame to bear the main loads. The other is the addition of concrete wall panels to improve the bearing capacity of masonry walls; however, the effective collaborative work between these two components remains challenging to guarantee. To address these limitations, this study proposes a novel composite structure formed by adding concrete columns with large cross-sectional dimensions on both sides of masonry walls. In this composite system, the masonry serves as the primary component for bearing vertical loads, whereas the masonry and concrete columns work collaboratively to collectively resist horizontal loads. Quasi-static tests and finite element simulations were conducted to systematically analyze the seismic performance of the proposed composite structure.

2. Model Test

2.1. Specimen Fabrication

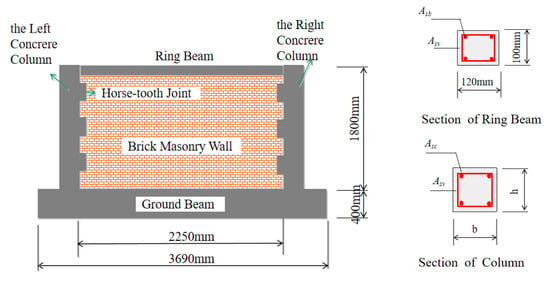

A multi-story masonry structure teaching building was taken as the prototype. For this prototype, the longitudinal wall axis spacing is 4.5 m, the transverse wall axis spacing is 6.6 m, the story height is 3.6 m, and the wall thickness is 0.24 m. The longitudinal wall between two adjacent axes on the ground floor was selected as the research object, and three test models (Fabricated in the Structural Laboratory of Shandong Jianzhu University) were designed and fabricated at a 1:2 scale ratio. The geometric parameters of the models are presented in Table 1. Specifically, CW1 is a masonry wall with ordinary construction columns on both sides, whereas CW2 and CW3 are masonry walls with structural columns on both sides, respectively (see Figure 1).

Table 1.

Specimen information.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the specimen.

For all specimens, the concrete strength grade of the bottom beams, ring beams, and structural columns was C30. The masonry was constructed using MU10 fired common bricks, with M5-grade mortar. The fabrication process for each specimen followed a specific sequence: first, the masonry walls were built with reserved interlocking joints; after which, the concrete columns were cast. Along the height of each masonry wall, two tie bars (diameter: 6 mm) were installed at 500 mm intervals, with each tie bar embedded 1000 mm into the masonry.

2.2. Test Setup

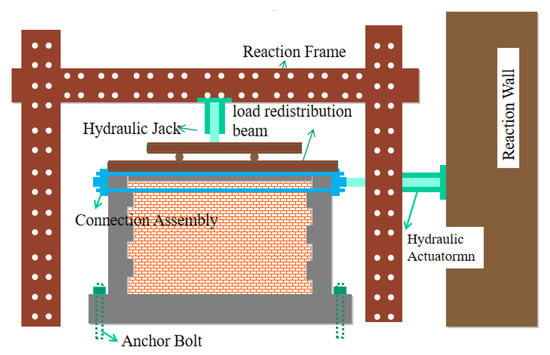

The specimen was anchored to the laboratory floor using anchor bolts. Hydraulic jacks were positioned on both sides of the bottom beam to ensure the specimen’s base remained in a fully constrained condition. A vertical load was applied to the top of the specimen via a hydraulic jack, which transferred the load through a loading steel beam to ensure uniform distribution of vertical pressure. Lateral supports were mounted on both sides of the specimen to prevent out-of-plane instability during loading. A horizontal cyclic load was applied to one side of the specimen’s top using a hydraulic servo actuator (manufactured by MTS Systems Corporation, Eden Prairie, MN, USA). To ensure the horizontal load was transmitted to the entire specimen, connectors were installed at both ends of the specimen’s top and fastened together with four rigid bolts. The test setup is schematically illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the test setup.

To monitor the stress state of the components, strain gauges were affixed along the longitudinal direction of the longitudinal reinforcement and transverse stirrups at the top, bottom, and mid-height positions of the concrete columns.

Based on calculations of the vertical loads transmitted from all upper floors of the prototype building, the vertical load sustained by the specimen was determined to be 160 kN. This load was applied at the top of the specimen using a 100-ton hydraulic jack and was maintained constant throughout the test. A 100-ton hydraulic servo actuator was mounted at the end of the top beam to impose a horizontal low-cycle reversed cyclic load. The test control system automatically recorded the applied loads and horizontal displacements, while the strain data acquisition system automatically recorded the strain values of the column reinforcement.

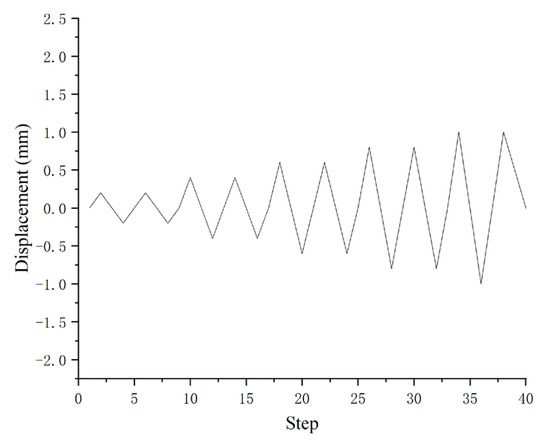

Prior to the formal test, a finite element simulation was performed to preliminarily determine the yield displacement. Preloading was conducted before the official test to ensure the proper functioning of the test system. Thereafter, horizontal cyclic loads were applied via a displacement-controlled protocol, with a step size of 0.2 mm and two cycles per step. Once the structure exhibited cracking, the step size was increased to 0.4 mm. Upon reaching the yield displacement, the step size was adjusted to the yield displacement. Loading was halted when the load carried by the specimen decreased to 85% of the ultimate load. The displacement-controlled loading protocol is illustrated in Figure 3. In the following text, the ratio of the clear span is used to represent the displacement at the top of the column [21].

Figure 3.

Loading System Diagram.

Prior to the experiment, material property tests were performed on the reserved concrete test blocks and clay bricks. The evaluated compressive strength values of the concrete and clay bricks were 27.5 MPa and 7.4 MPa, respectively. The mechanical property test results of the reinforcing steel bars from the same batch used in the specimens are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of steel materials.

2.3. Test Phenomena

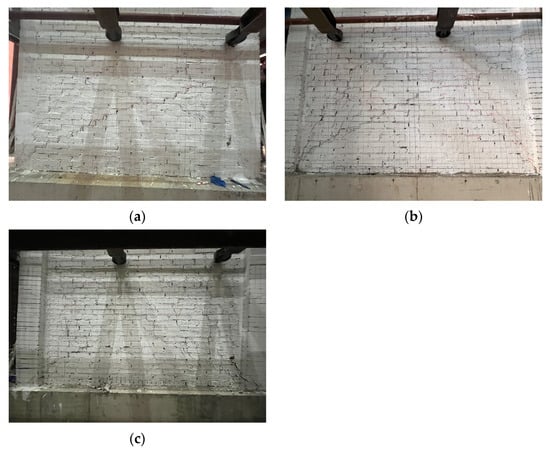

At the initial loading stage, the CW1 specimen showed no visible damage, and the load–displacement curve exhibited approximately linear behavior. The direction of the actuator’s extension (i.e., the leftward direction in Figure 2) is defined as the positive direction. When the drift ratio reached +0.03% (corresponding to a load of 51.6 kN), fine horizontal cracks emerged on the left structural column at a position 0.6 m from the top. As the loading displacement increased, the number of cracks at both the upper and lower ends of the left structural column progressively increased. In the case of the drift ratio of +0.21% (with a load of 127.3 kN), diagonal stair-step cracks developed in the middle of the wall, penetrating four courses of bricks. These main cracks were accompanied by multiple secondary stair-step cracks in the surrounding area, while cracks on the structural column side propagated toward the wall. At the drift ratio of +0.26% (load: 128.6 kN), the positive load attained its peak value, and the stair-step cracks extended along the full diagonal length of the wall surface and through the wall thickness (Figure 4a). When the drift ratio reached +0.56% (load: 117.6 kN), (load: 117.6 kN), mortar spalling was observed at multiple locations on the wall, particularly at the column-wall interface. At +0.83% drift ratio (load: 98.7 kN), the maximum crack width measured 18 mm, and significant relative displacement occurred between the upper and lower wall segments separated by the cracks. The test was terminated when the specimen’s bearing capacity dropped to 85% of its peak value.

Figure 4.

Crack distribution map of specimens: (a) Crack of CW1; (b) Crack of CW2; (c) Crack of CW3.

For CW2, initial cracking also occurred at the top of the structural column. When loaded to the drift ratio of +0.18% (corresponding to a load of 182.0 kN), multiple horizontal cracks emerged at the mid-height of the left column, accompanied by continuous diagonal stair-step cracks in the left half of the wall. The longest crack spanned four brick courses, aligning with the mortar joints. At +0.22% drift ratio (load: 179.7 kN), several stair-step cracks penetrated the wall thickness, marking the specimen’s yield state. Upon reaching −0.28% drift ratio (load: −222.1 kN), the stair-step cracks propagated from the 2/3 height of the left column to the wall’s midspan, indicating shear-dominated failure. Further loading to −0.5% (−219.9 kN) induced cracking on the inner face of the left column base, accompanied by localized brick crushing near the foundation interface. At +0.83% drift ratio (load: 202.3 kN), the positive load reached its peak, with densely distributed stair-step cracks on the right wall segment. Significant relative displacement occurred along the main cracks, causing visible dislocation (Figure 4b). Loading to −1.17% (−197.4 kN) triggered mortar spalling on the left wall, exposing underlying brick surfaces. at −1.67% drift ratio (−227.7 kN), multiple 6-mm-wide cracks developed at the base of the right column. Although the specimen’s bearing capacity did not continuously decline, extensive crushing of the wall and column interfaces indicated irreversible damage, prompting test termination.

For CW3, the failure process resembled CW1 and CW2 but exhibited delayed cracking. Initial horizontal cracks appeared 150 mm below the top of the right structural column at the drift ratio of +0.13% (load: 146.6 kN), spanning 100 mm along the mortar joint. Upon reaching +0.17% drift ratio, discontinuous stair-step cracks formed in the wall, indicating localized shear stress concentrations. At +0.32% drift ratio, (load: 198.6 kN), the specimen yielded under positive loading, marked by continuous stair-step cracks propagating through the wall thickness. Subsequent loading to −0.41% (−251.1 kN) triggered shear-dominated failure, with cracks extending from the wall to the tie beams and structural columns. Further loading to −0.78% (−261.3 kN) caused cracks to coalesce, compromising the column-beam connection integrity. At +0.89% drift ratio (load: 230.1 kN), the peak positive load was reached, accompanied by brittle crushing of bricks in the left wall segment and a 6-mm-wide crack at the base of the right column. Significant relative displacement along the main cracks led to visible wall dislocation (Figure 4c). Finally, at −1.94% drift ratio, (−220.9 kN), 6-mm-wide cracks developed at both column bases, indicating irreversible damage to the load-bearing framework. Despite stable load retention, extensive masonry crushing and column-root failures necessitated test termination.

2.4. Hysteretic and Skeleton Curves of Specimens

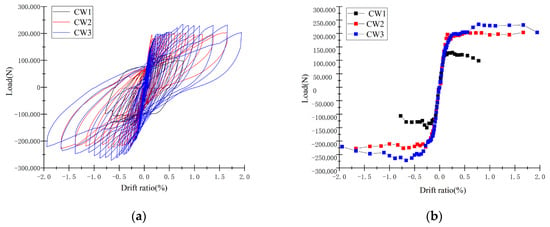

The horizontal load-lateral displacement hysteretic curves and skeleton curves of the three specimens are presented in Figure 5a,b.

Figure 5.

The loading–drift ratio hysteretic curves and the skeleton curves of the three specimens: (a) Hysteretic curves; (b) Skeleton curves.

From Figure 5a, the following observations can be made: At the initial loading stage, the relationship between load and lateral displacement of the specimens is approximately linear, indicating an elastic state where the loading and unloading curves overlap. As the load increases, cracks initiate, plastic deformation develops, and the area enclosed by the hysteretic loops gradually enlarges. The hysteretic curve of CW1 exhibits a spindle shape with no significant pinching effect, and it declines gently after attaining the peak load. In contrast, the hysteretic loops of CW2 and CW3 are inverse S-shaped, with fluctuations emerging in the descending branch after reaching the peak load.

This phenomenon is attributed to the following mechanisms: In the later loading stage, the construction columns of CW1 sustained damage, with no significant slip observed in the wall. In contrast, for CW2 and CW3, initial cracks propagated into continuous cracks, resulting in significant slip within the masonry walls. Nevertheless, the concrete columns of CW2 and CW3 exhibited no significant cracking, and their longitudinal reinforcement and stirrups remained unyielded. This allowed the columns to continue contributing to the horizontal bearing capacity of the specimens.

From Figure 5b, it is evident that the skeleton curves of the three specimens exhibit substantial overlap at the initial loading stage. However, the yield points of CW2 and CW3 are relatively close and both higher than that of CW1. In the elasto-plastic range (from yielding to peak load), the ranges of CW2 and CW3 are longer than that of CW1. After the peak load, the descending branches of CW2 and CW3 are gentler than those of CW1.

2.5. Mechanical Property Parameters of Specimens

The mechanical property parameters of the three specimens at each failure stage are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

The mechanical property parameters of specimens.

As summarized in Table 3, CW2 and CW3 exhibit a yield load approximately 60% higher than that of CW1, with their peak loads being 53.92% and 82.0% higher, respectively. Additionally, their ductility coefficients are roughly 30% higher than that of CW1. These results demonstrate that increasing the cross-sectional size of concrete columns not only enhances the bearing capacity of the composite structure but also improves its ductility.

2.6. Cumulative Energy Dissipation of Specimens

The calculated cumulative energy dissipation of the specimens at each failure stage is presented in Table 4. It can be found by comparison that from initial loading to the member cracking stage, the cumulative energy dissipation of CW2 is essentially comparable to that of CW1. However, at the structural yielding, peak bearing capacity, and ultimate displacement stages, the cumulative energy dissipation of CW2 is 5.3 times, 2.5 times, and that of CW1, respectively.

Table 4.

The cumulative energy dissipation of the specimens at each failure stage (kN·mm).

From initial loading to the member cracking stage, the cumulative energy dissipation of CW3 is 8 times that of CW1. At the structural yielding, peak bearing capacity, and ultimate displacement stages, its cumulative energy dissipation reaches 8.5 times, 14 times, and 3.6 times that of CW1, respectively. These findings confirm that increasing the cross-sectional size of concrete columns significantly enhances the energy dissipation capacity of the structure.

3. Numerical Simulation of Test Specimens

3.1. Model Establishment

Numerical simulations of specimens CW1, CW2, and CW3 were performed using ABAQUS (2020) software [22]. Modeling masonry walls as uniform integral components renders crack propagation simulation challenging; whereas separate modeling of blocks and mortar results in computational convergence issues [23]. Thus, a simplified discrete modeling approach was employed in this study: blocks and their surrounding mortar were not modeled as discrete elements; instead, each block, together with the mortar encapsulating it, was treated as a single masonry element.

The interfaces between the discrete masonry elements were simulated via contact properties [24]. For tangential behavior, the Penalty formulation was employed, and the friction coefficient was set to 0.7 with reference to the provisions of the Code for Design of Masonry Structures (GB50003-2011) [25]. Normal behavior was modeled using “Hard” contact to capture the compressive failure of mortar [22], whereas the bonding effect of mortar was captured using viscous behavior and damage models. Surface parameters were determined with reference to existing literature [26], as summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

The surface parameters between bulk elements.

Concrete and masonry were both modeled with C3D8 solid elements, while reinforcement was modeled with T3D2 truss elements [22]. The bond-slip behavior between reinforcement and concrete was neglected in the simulation. In the specimens, rabbet joints were present between the masonry and concrete columns, and tie bars were installed at these joints. Experimental results have demonstrated that the mechanical connection between masonry and columns is sufficiently robust; thus, the interface between masonry and concrete columns was defined as a “tied” connection in the model. The lower edge of each specimen was assigned a fully fixed boundary condition to simulate the constraining effect of the ground beam.

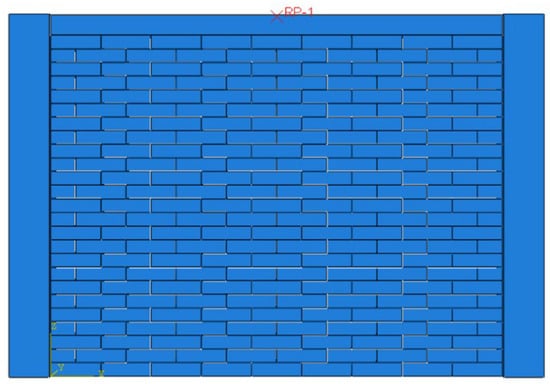

The finite element model of the composite structure is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The finite element model of the composite structure.

In the model, concrete columns and ring beams were meshed with cubic elements of 60 mm edge length, reinforcing bars were meshed with linear elements of 60 mm in length, and masonry was meshed with cuboid elements of 120 mm × 30 mm × 120 mm.

The concrete plastic damage (CPD) model was adopted for the constitutive relations of both concrete and masonry. For concrete, the stress–strain curves, elastic modulus, and Poisson’s ratio were determined in accordance with the Code for Design of Concrete Structures (GB50010-2010) [27]. The uniaxial compressive stress–strain curve of masonry was derived from Yang W Z’s model [28], while its uniaxial tensile stress–strain curve was defined based on the simplified constitutive equation from Reference [29]. Specific parameter values for the constitutive models are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

The material plastic parameters.

For the masonry elements, the mass density was set to 2000 kg/m3, the elastic modulus E was calculated in accordance with Equation (1) [30], and Poisson’s ratio was set to 0.15 [29].

where fm denotes the average ultimate strength of masonry, which is defined as the average axial compressive strength of masonry (fm,c) and calculated using Equation (2); whereas the average axial tensile strength of masonry (fm,t) is calculated using Equation (3).

where fm,c and fm,t denote the average axial compressive strength and average axial tensile strength of masonry, respectively. k1 is assigned a value of 0.78, f1 represents the strength grade value of masonry blocks; k2 is set to 1, and f2 refers the average compressive strength of mortar.

HPB300 and HRB400 grade reinforcing steel were both modeled using a bilinear elasto-plastic model with post-yield hardening. For these reinforcements, the elastic modulus Es was set to 200 GPa, and Poisson’s ratio was set to 0.3. To ensure the reliability of the simulation results, the yield srtength and ultimate strength are based on the test data in Section 2.2 [31,32].

For the boundary conditions and loading application: The top surface of the model was coupled to a reference point (RP-1). The out-of-plane degrees of freedom of RP-1 were constrained by limiting out-of-plane displacements in the boundary condition settings. Vertical loads and horizontal displacements identical to those applied in the experiment were imposed on RP-1.

The failure mode of each specimen was determined by analyzing the model’s damage contours. Consistent with the criteria in Reference [33], the specimen was considered failed when the tensile and compressive damage values in the contours reached 0.9.

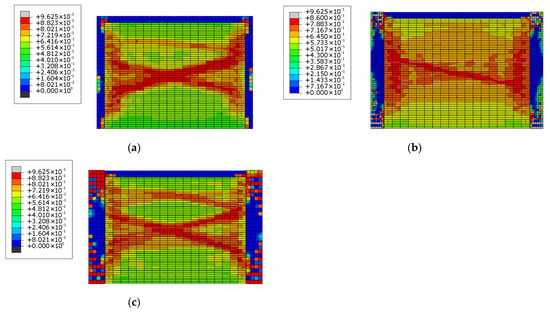

3.2. Comparison of Finite Element Simulation and Experimental Results

The tensile damage contour map of the finite element simulation at the specimens’ failure is presented in Figure 7. It can be observed that Specimen CW1 exhibits obvious tensile damage along the wall diagonal, with additional tensile damage detected on the outer side of the middle section of the constructional column. For Specimens CW2 and CW3, the tensile damage on the walls is more extensively distributed, and damage to the columns on both sides initiates at the column root and top regions. When compared with the experimental results presented in Figure 4, the finite element simulation results and experimental results exhibit good agreement.

Figure 7.

Tensile damage contour map of the specimen from finite element analysis: (a) Contour map of CW1; (b) Contour map of CW2; (c) Contour map of CW3.

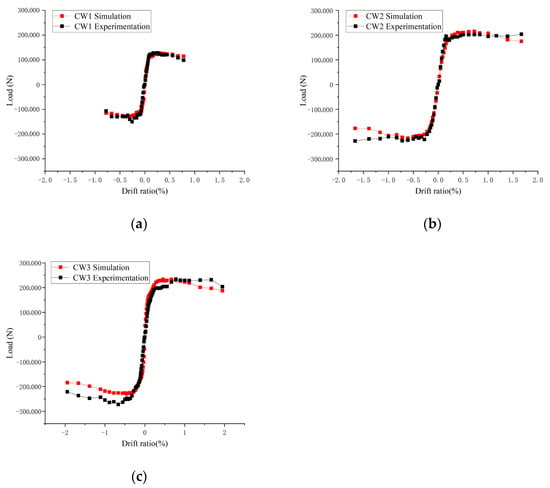

Comparisons of the load–displacement skeleton curves derived from finite element analysis (FEA) and experimental results are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Comparison of skeleton curves: (a) Skeleton curves of CW1; (b) Skeleton curves of CW2; (c) Skeleton curves of CW3.

The two sets of curves (i.e., those from FEA and experiments) exhibit good agreement, indicating that the finite element method (FEM) is feasible for analyzing the mechanical properties of the studied structures.

4. Seismic Performance Analysis of Composite Structures

4.1. Structural Failure Modes

Composite structures consisting of masonry walls and concrete columns with varying cross-sections were adopted in this study, and their mechanical behaviors were analyzed using ABAQUS (2020) software [22]. Detailed model information is summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Model Information.

Specifically: W1 and W7 (note: potential typo correction; original “W5” was duplicated) are masonry walls with constructional columns; W2, W3, W5, and W6 are composite structures; W4 and W8 are frame infill walls, which were used as reference groups for comparison.

All models feature a height of 3.6 m and a wall thickness of 240 mm. The concrete strength grade of beams and columns is specified as C30, the strength grade of brick units is MU10, and the mortar grade is M5. For W4 and W8, the bottom of the infill walls is unconstrained, whereas their two side edges are connected to frame columns through tie bars. The remaining models were established in accordance with the methodology outlined in Section 3.1.

For Models W4 and W8, vertical loads corresponding to the current floor were imposed on the frame beams, while vertical loads effectively transferred from the upper structure were applied to the top of the frame columns. For the remaining models, vertical loads acting on the upper surfaces of ring beams and columns were uniformly distributed and then imposed on the coupling nodes at the top of the models. Subsequently, horizontal cyclic loads were applied to these coupling nodes in a displacement-controlled manner, and the entire process—from the initiation of structural cracking to final failure—was systematically monitored. Tensile damage contour maps of each structural model at the moment of failure are presented in Figure 9.

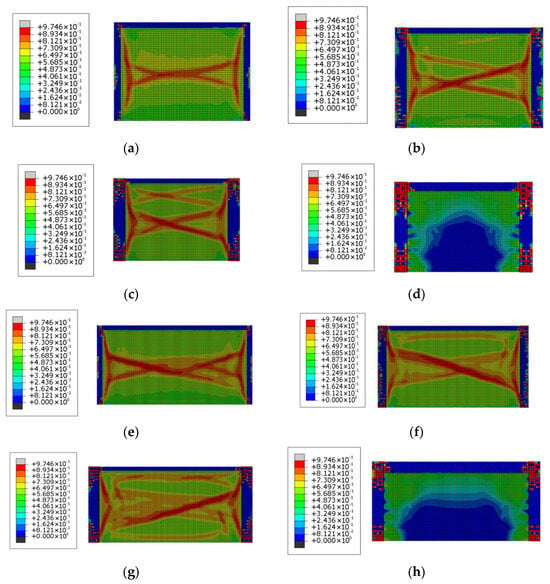

Figure 9.

Tensile contour maps of structural models: (a) Tensile contour maps of W1; (b) Tensile contour maps of W2; (c) Tensile contour maps of W3; (d) Tensile contour maps of; (e) Tensile contour maps of W5; (f) Tensile contour maps of W6; (g) Tensile contour maps of W7; (h) Tensile contour maps of W8.

During the loading process, the constructional columns of both Models W1 and W5 initiated cracking first; when the structures reached failure, concentrated main cracks were formed in the walls. For Models W2, W3, W6, and W7, a clear trend was observed: the larger the cross-section of the concrete columns, the later the walls initiated cracking, and the more extensive the crack distribution became. For Models W4 and W8, cracks first initiated in the frame beams and columns, followed by propagation until structural failure; notably, no significant tensile damage was observed in the walls throughout the process.

At the moment of structural failure, the reinforcing bars in the columns of Models W1, W2, W3, and W4 failed to reach the yield stress. In contrast, both longitudinal and transverse reinforcements in the columns of Model W5 yielded, whereas the longitudinal reinforcements in the columns of Models W6, W7, and W8 reached the yield stress. These results indicate that composite structures with wider walls equipped solely with constructional columns exhibit a risk of brittle failure, whereas the ductility of composite structures incorporating concrete columns with larger cross-sections is significantly enhanced.

4.2. Seismic Performance of Structural Models

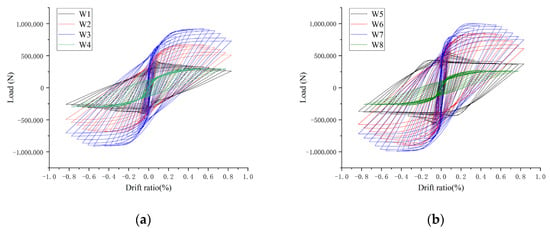

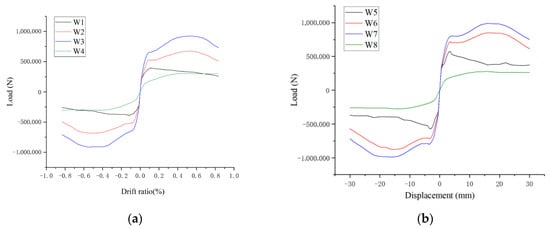

The horizontal loading-top lateral drift hysteretic curves and skeleton curves of the studied models (i.e., W1–W8) are presented in Figure 10 and Figure 11, respectively. These curves intuitively reflect the force-deformation responses, energy dissipation characteristics, and stiffness degradation behaviors of each model under horizontal cyclic loading, which serve as core basis for evaluating the seismic performance of the composite structures.

Figure 10.

Comparison of hysteretic curves of each model: (a) The hysteretic curves of structures with a wall width of 4500 mm; (b) The hysteretic curves of structures with a wall width of 6600 mm.

Figure 11.

Comparison of skeleton curves of each model: (a) The skeleton curves of structures with a wall width of 4500 mm; (b) The skeleton curves of structures with a wall width of 6600 mm.

The ductility coefficients of each model were calculated based on the average values of key characteristic points (e.g., yield point, ultimate point) obtained under positive and negative loading directions. All seismic performance parameters of the models are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Performance Parameters of Each Model.

Analysis of the data reveals that the ductility of the composite structures (i.e., W2, W3, W6, W7) is superior to that of the masonry walls with constructional columns (i.e., W1, W5), but inferior to that of the frame infill wall structures (i.e., W4, W8).

Specific observations from the performance parameters are as follows:

For structural models with a wall width of 4.5 m: compared with the masonry wall with constructional columns (W1), the composite structures (W2, W3) exhibit a 4-fold increase in peak displacement. Meanwhile, their peak bearing capacities are increased by 73% and 135%, respectively, and their ductilities are enhanced by 15% and 11%, respectively.

For structural models with a wall width of 6.6 m, compared with the masonry wall with constructional columns (W5), the composite structures (W6, W7) also show a 4-fold increase in peak displacement. Their peak bearing capacities are increased by 50% and 73%, respectively, and their ductilities are enhanced by 170% and 190%, respectively.

In contrast, when compared with the frame infill wall models (W4, W8), the composite structure models (W2, W3, W6, W7) exhibit significantly enhanced stiffness and bearing capacity, though their ductility is reduced to varying degrees.

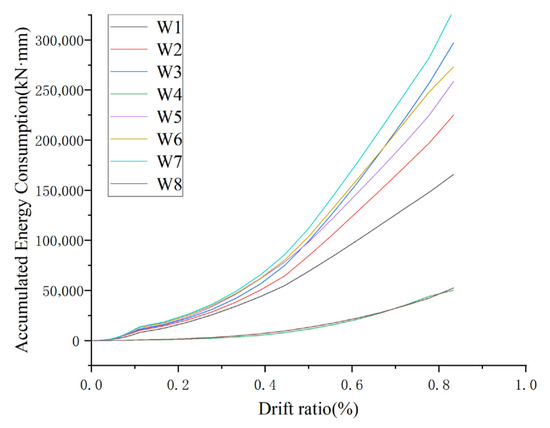

The cumulative energy dissipation of each structural model (i.e., W1–W8) is presented in Figure 12, with the data plotted as a function of top lateral drift. As a core indicator reflecting the energy absorption and dissipation capacity of structures under horizontal cyclic loading, the cumulative energy dissipation directly correlates with the seismic resilience of the composite structures studied.

Figure 12.

The cumulative energy dissipation of each structural model.

Analysis of Figure 12 reveals three key trends regarding cumulative energy dissipation:

Under the same top lateral drift, the cumulative energy dissipation of the composite structures (i.e., W2, W3, W6, W7) is greater than that of the frame infill wall structures (i.e., W4, W8); The cumulative energy dissipation of structures with a wall width of 6.6 m (including composite structures W6, W7 and masonry wall W5) is greater than that of structures with a wall width of 4.5 m (including composite structures W2, W3 and masonry wall W1); For composite structures with the same wall width (e.g., W2 vs. W3, W6 vs. W7), the larger the cross-sectional dimension of the concrete columns, the greater the cumulative energy dissipation.

5. The Shear Bearing Capacity of Composite Structure

When composite structures reach their ultimate bearing capacity, the masonry walls undergo shear slip deformation. Based on the shear-friction principle and considering the effects of compressive stress and tie bars, the calculation formula for the shear bearing capacity of the masonry wall-proposed in Reference [34] is as Equation (4).

wherein, all physical quantity symbols definitions are specified as follows:

Pw: Shear bearing capacity of the masonry wall;

γRE: Seismic adjustment factor, adopted as 0.9 in compliance with the Code for Design of Masonry Structures (GB 50003-2011) [25];

AW: Cross-sectional area of the masonry wall (calculated as the product of wall width and thickness);

ξW: Shear force non-uniformity factor, set to 0.37;

fvc,k: Characteristic value of the shear strength of masonry;

μ: Friction coefficient between masonry layers, adopted as 0.7;

: Compressive stress at the mid-height of the masonry wall (derived from vertical load FW and cross-sectional area AW);

ξs: Participation coefficient of tie bars in load-bearing, adopted as 0.125 in compliance with the Code for Design of Masonry Structures (GB 50003-2011) [25];

Fyh,k: Yield strength of tie bars;

Ash: Total cross-sectional area of tie bars.

The Code for Design of Concrete Structures (GB 50010-2010) [27] and Code for Design of Masonry Structures (GB 50003-2011) [25] specify the verification formula for the inclined section shear bearing capacity of reinforced concrete (RC) members (Formula (5)) and that of masonry walls with constructional columns (Formula (6)), respectively.

In Formula (6), “0.08” represents the contribution of longitudinal reinforcement.

Since composite structures exhibit failure modes similar to those of masonry walls with constructional columns, the calculation of the inclined section shear bearing capacity of concrete columns in composite structures should refer to Formula (6). Considering the contributions of concrete, stirrups, longitudinal reinforcement, and vertical forces, this calculation is expressed as Formula (7).

wherein, all physical quantity symbols are specified as follows:

Pc: Shear bearing capacity of the reinforced concrete column;

λ: Calculated shear-span ratio (1 ≤ λ ≤ 3);

ft,k: Characteristic value of tensile strength of concrete;

b: Cross-sectional width of the column;

h0: Effective cross-sectional height of the column;

fyv,k: Characteristic value of tensile strength of stirrups;

Asv: Total cross-sectional area of all legs of stirrups arranged in the same column cross-section;

s: Spacing of stirrups along the height of the concrete column;

fyc,k: Characteristic value of tensile strength of longitudinal reinforcement the in column;

As: Total cross-sectional area of longitudinal reinforcement in the column;

N: Axial pressure of the column (equal to the vertical load transmitted from the upper structure);

α, β, γ: Participation coefficients of concrete, stirrups, and longitudinal reinforcement in shear resistance, respectively (determined by regression analysis of the test data in this study).

Experimental results indicate that when Specimens CW2 and CW3 reached their ultimate bearing capacity, multiple cracks in the concrete had fully developed. This phenomenon suggests that approximately 80% of the concrete had reached its tensile strength, corresponding to a value of α = 0.80.

The shear contribution of longitudinal reinforcement and stirrups was calculated using test-measured strains. The participation coefficients of these two types of reinforcement derived from the above calculations are presented in Table 9 and Table 10, respectively. For consistency, the average values of the calculation results from the two specimens were adopted, leading to the determination of β = 0.175 and γ = 1.065.

Table 9.

Calculation of Stirrup Participation Coefficient.

Table 10.

Calculation of Longitudinal Reinforcement Participation Coefficient.

After substituting each shear-resisting participation coefficient into Equation (7) and combining the resulting expression with Equation (5), the formula for calculating the ultimate shear bearing capacity of the composite structure is derived as Equation (8):

The horizontal bearing capacities of Models W2, W3, W5, and W6 were calculated using Equation (8). These calculated values were then compared with the finite element simulation results (see Table 11), and a good agreement was observed between the two sets of results.

Table 11.

Comparison of Calculated and Simulated Values of Peak Load.

6. Conclusions

This study investigates the failure mechanisms and seismic performance of reinforced concrete (RC) column-masonry wall composite structures through quasi-static tests on three scaled-down models. Furthermore, it conducts numerical simulations and mechanical behavior analysis of composite structures with varying concrete column cross-sectional dimensions using six finite element (FE) models. The key conclusions drawn from this research are as follows:

- (1)

- Both masonry walls with constructional columns and those in composite structures form main X-shaped cracks at failure, characterized by shear failure. However, the constructional columns in the former (masonry walls with constructional columns) develop diagonal cracks and undergo shear failure in conjunction with the walls. In contrast, concrete columns with larger cross-sections constrain the propagation of wall cracks and significantly enhance the peak bearing capacity of the structure; moreover, the larger the cross-sectional dimension of the concrete column, the more pronounced the enhancement in bearing capacity.

- (2)

- Compared with masonry structures with constructional columns, composite structures exhibit a more extensive crack distribution, along with superior structural ductility and energy dissipation capacity. Specifically, the larger the column cross-section, the more notable the enhancement in the ductility performance of the composite structure.

- (3)

- The ABAQUS simulation results of the composite structure test models are in good agreement with the experimental results, demonstrating that the simplified separate modeling approach is applicable for analyzing the mechanical behavior of composite structures.

- (4)

- A horizontal bearing capacity formula, derived from the test results, is proposed for calculating the shear bearing capacity of composite structure models. The calculated values using this formula show good consistency with the numerical simulation results.

In the finite element analysis of this study, a simplified separated modeling approach was adopted for the masonry walls, which cannot accurately simulate the stepped failure mode of the masonry walls. In future research, a detailed separated modeling method can be employed to characterize the mechanical properties of mortar, thereby yielding more precise computational results. Additionally, for the retrofitting of existing masonry walls, concrete columns can be cast externally around the walls; alternatively, the cross-section of the columns can be designed as L-shaped or T-shaped. Research on such composite structures holds greater engineering application value.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, X.F.; validation and formal analysis, X.L., investigation, Y.Q. and Y.P.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L.; writing—review and editing, X.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xinru Lin was employed by Weifang Highway Development Center. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Civil Engineering Structure Expert Group of Tsinghua University; Civil Engineering Structure Expert Group of Southwest Jiaotong University; Civil Engineering Structure Expert Group of Beijing Jiaotong University. Analysis of building damage in the Wenchuan earthquake. J. Build. Struct. 2008, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Li, B.X.; Deng, J.H.; Wang, Q.Y. Seismic damage analysis of masonry structures in Lushan earthquake. Build. Struct. 2013, 43, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Işık, E.; Avcil, F.; Büyüksaraç, A.; İzol, R.; Arslan, M.H.; Aksoylu, C.; Harirchian, E.; Eyisüren, O.; Arkan, E.; Güngür, M.Ş.; et al. Structural damages in masonry buildings in Adıyaman during the Kahramanmaraş (Turkiye) earthquakes (Mw 7.7 and Mw 7.6) on 06 February 2023. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 151, 107405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık, E.; Avcil, F.; Hadzima-Nyarko, M.; Arslan, M.H.; Bulbul, M.A.; Harirchian, E. Seismic performance and failure mechanisms of reinforced concrete structures subject to the earthquakes in Türkiye. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.Z.; Liu, M.Y.; Cheng, X.W.; Li, Y. Comparative study on the collapse mechanisms of building structures induced by strong earthquakes: Cases of Wenchuan and Türkiye earthquakes. Build. Struct. 2025. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Preliminary Study on Seismic Damage Prediction Method for Masonry Structures Considering the Influence of Ring Beams and Structural Columns. Master’s Thesis, Institute of Engineering Mechanics, China Earthquake Administration, Harbin, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Z.W.; Yang, D.M.; Ma, D.L.; Qiao, Q.Y. Seismic collapse resistance analysis of typical rural masonry structures based on numerical simulation. J. Southeast Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 52, 506–515. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Z.W.; Chen, K.N.; Ma, D.L.; Yang, D.M.; Liu, Y.F. Seismic collapse fragility analysis of rural masonry structure dwellings. J. Southeast Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2014, 54, 1154–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabi, A.B.; Shing, P.B. Performance of masonry-infilled R/C frames under in-plane lateral loads: Analytical modeling. In Proceedings of the NCEER Workshop on Seismic Response of Masonry, San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–5 February 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabi, A.B.; Benson Shing, P.; Schuller, M.P.; Noland, J.L. Experimental evaluation of masonry-infilled RC frames. J. Struct. Eng. 1996, 122, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.X.; Guo, Z.X.; Zhu, Y.R.; Liu, Y. Experimental study on seismic behavior of RC frames infilled with concrete hollow blocks. J. Build. Struct. 2012, 33, 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Gu, S.; Lei, T.; Wen, N.; Chang, X.L. Research on the failure mechanisms and energy dissipation design of infilled walls frame. J. Southwest Univ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 33, 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.D. Evaluation of Seismic Behavior of Infilled Wall with Combined Tie-Columns. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, P.; Tang, X.R.; Pi, S.P. Experimental study on seismic behavior of reinforced concrete frames infilled with concrete blocks. Earthq. Resist. Eng. Retrofit. 2021, 43, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, C.H.; Wang, X.M.; Kong, J.C.; Wei, Y.L.; Jin, W.; Zhao, Y. Progress and Prospect of Seismic Performance of Masonry-infilled RC Frames. J. Harbin Inst. Technol. 2018, 50, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Massumi, A.; Mahboubi, B.; Ameri, M.R. Seismic response of RC frame structures strengthened by reinforced masonry infill panels. Earthq. Struct. 2015, 8, 1435–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teguh, M. Experimental evaluation of masonry infill walls of RC frame buildings subjected to cyclic loads. Procedia Eng. 2017, 171, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.C.; Lin, H.F.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Zou, Z.Y.; Liang, W. Study on the influence of cast-in-place constructional column on seismic performance of masonry infilled wall steel frame structure. China Civ. Eng. J. 2022, 55, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.Q.; Ma, J.Y.; Cheng, L.T. Study on the Cooperative Working Performance of Concrete Frame-Reinforced Block Masonry Hybrid Structure under Vertical Loads. Chin. J. Appl. Mech. 2013, 30, 550–556+647. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.X.; Zhang, F.W.; Li, X.M.; Zheng, S.J.; Zheng, Q.W. Experimental study on seismic behavior of masonry structure with post-installed reinforced concrete walls. China Civ. Eng. J. 2017, 10, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Pekgökgöz, R.K.; Avcil, F. Effect of steel fibres on reinforced concrete beam-column joints under reversed cyclic loading. Građevinar 2021, 73, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar]

- ABAQUS, Dassault Systemes SE: Vélizy-Villacoublay, France, 2020.

- Guo, Y.; YU, D.H.; LI, G. Efficient Nonlinear Analysis Method of Masonry Structures Based on Discrete Macro-element. Eng. Mech. 2022, 39, 185–199. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.P.; Dong, F.Y.; Jiang, F.M. Analysis of Diagonal Shear Behavior of Masonry Wall Strengthened with Engineered Cementitious Composites (ECC). Eng. Mech. 2024, 41, 201–214. [Google Scholar]

- GB 50003-2011; Code for design of masonry structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Wang, Z.K. Numerical Simulation of Masonry Walls Strengthened with MRPC Surface Layer. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Jianzhu University, Jinan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- GB 50010-2010; Code for design of concrete structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Yang, W.Z. Constitutive relationship model for masonry materials in compression. Build. Struct. 2008, 10, 80–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, N.N. Research on Seismic Behavior of Masonry Structures with Fabricated Tie-Columns. Ph.D. Thesis, Chognqing University, Chognqing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pařenica, P.; Krejsa, M.; Brožovský, J.; Lehner, P. Verification of Numerical Models of High Thin-Walled Cold-Formed Steel Purlins. Materials 2024, 17, 4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, H.; Lehner, P.; Eghbali, M.; Ahmadi, J.; Badarloo, B. Performance assessment of novel parallel double-stage yield buckling-restrained braces for seismic hazard mitigation. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2025, 227, 109389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.X. Theory and Design of Masonry Structure, 2nd ed.; Building Industry Publishing House of China: Beijing, China, 2003; pp. 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.S.; Jia, W.Q.; Zhang, Z.J. Study on seismic performance of prefabricated special-shaped column frame side. Build. Struct. 2023, 53, 25–32+24. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C. Seismic Performance and Interaction Mechanism of Infilled RC Frames Using New Masonry Blocks. Ph.D. Thesis, Huaqiao University, Xiamen, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).