Abstract

Recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) provides an effective approach for the large-scale reuse of construction and demolition waste. This study systematically investigates the performance degradation mechanism of RAC and proposes targeted suggestions for enhancing its performance. The key findings are summarized as follows: (1) The macroscopic performance of RAC is consistently inferior to that of natural aggregate concrete (NAC). Specifically, the compressive and tensile strengths of RAC decrease by 3–50% with the increase in recycled aggregate (RA) replacement rate. (2) At the macroscopic scale, the inherent defects of RA (e.g., cracks and attached mortar) are the primary drivers of RAC performance degradation. At the microscopic scale, early-stage deterioration is mainly attributed to the high porosity (20%~27%) of RAC and the weak interfacial transition zones (ITZ) between aggregates and paste. At the same time, later-stage degradation is induced by the formation of multiple weak transition zones within the matrix. (3) For practical engineering applications, the principle of “source strengthening, process optimization, and hierarchical application” should be adhered to, aiming to improve the performance and promote the utilization efficiency of RAC. These findings establish a cross-scale theoretical foundation for the performance enhancement of RAC, thereby contributing to the more efficient resource utilization of C&D waste and advancing the sustainability of the construction industry.

1. Introduction

Construction and demolition waste (CDW) accounts for at least 30% of global solid waste. For instance, the European Union (EU) generates 924 million tons annually, while China produces 2.36 billion tons [1]. In China, the resource utilization rate of CDW is less than 20%, which is significantly lower than the 80% achieved in developed countries [2,3]. Therefore, the recycling and reuse of RA have become a research hotspot in the construction field.

Many scholars [4,5] agree that the key difference between recycled aggregates (RA) and natural aggregates (NA) is the old mortar adherence to RA surfaces. This old mortar is loose and porous, which causes inferior properties in RA, such as low strength, low density, numerous surface pores, high water absorption, and poor adhesion to new mortar [6,7,8,9]. Additionally, Duan [10] found that the quality and content of old mortar in RA vary significantly depending on the strength of the original concrete, the crushing method, and the degree of crushing. During the production of RA, the aggregates are continuously subjected to collisions and compression, leading to the accumulation of internal damage and the formation of many micro-cracks. Seo et al. [11] discovered through experiments that when the amount of old mortar on the surface of recycled coarse aggregate exceeds a certain value, it significantly reduces the tensile bond strength at the aggregate–mortar interface. Due to the weaknesses of RA compared to NA, RAC exhibits declining mechanical properties, workability, and durability as RA replacement rates increase [12,13,14]. Studies show that RAs are characterized by a porous structure, low density, and weak interfacial zones [15], which lead to a reduction in compressive strength, split tensile strength, and elastic modulus at higher substitution rates [16,17]. Notably, RA content affects elastic modulus more severely than compressive strength [18,19]. Moreover, as the replacement rate of RA increases, the workability and durability of RAC will also decrease [20,21,22], accelerating carbonation depth over time [23]. Therefore, RA enables large-scale recycling of waste concrete; RAC’s performance degradation remains inevitable.

To explore the fundamental causes of performance degradation in RAC and to find effective reinforcement measures, many scholars have conducted extensive research on the microstructure and micro-mechanism of recycled concrete. Poon [24] found that RA’s high water absorption during the early hydration increases pores and porosity in new mortar. Du et al. [25] compared microhardness across recycled coarse aggregate (RCA), old interfacial transition zones (OITZs), and new interfacial transition zones (NITZs) between recycled coarse aggregate and fresh mortar matrix, revealing that the NITZ exhibits the lowest microhardness, a key factor in RAC’s performance decline. This conclusion is also supported by [15]. However, existing studies lack systematic investigation into RAC’s long-term performance and microstructural evolution, and time-dependent degradation mechanisms.

The above research on the performance degradation of RAC primarily focuses on the analysis of macroscopic performance and its influencing factors. However, most studies investigating the correlation between microstructure and macroscopic performance fail to consider the effect of curing age. Additionally, the recycled aggregate (RA) replacement rate adopted in the existing literature is generally below 50%, and the feasibility and performance mechanisms of high RA replacement rates (i.e., above 50%) have not been thoroughly explored. To address these research gaps, the present study conducted experimental investigations on the macroscopic performance and microstructure of RAC with low, medium, and high RA replacement rates at both early and later curing stages. Furthermore, the underlying mechanisms governing the macroscopic performance degradation of RAC at different ages were systematically explored. Finally, performance optimization measures were proposed.

Key contributions of this study include (1) Comprehensive Methodology: unlike prior studies that focus on single-age or macro-scale analysis of RAC, this work integrates multi-age, multi-replacement-rate experiments with macro- and micro-scale analysis, resulting in more systematic insights. (2) Stage-Specific Mechanisms: the proposed stage-specific degradation mechanisms and graded application strategies clarify distinct early- and late-stage deterioration processes, thereby facilitating performance optimization and enhancement at different phases. (3) Performance Optimization Measures: the RAC performance optimization principles and measures of “source strengthening, process optimization, and hierarchical application” are proposed to improve its utilization.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Materials

In this study, ordinary Portland cement (42.5 R) and natural river sand were used as fine aggregates. The natural river sand had a fineness modulus of 2.61 and an apparent density of 2400 kg/m3. RA was sourced from a building materials company in Nanjing. The RA had a density of 2380 kg/m3, a crushing value of 14.96%, and a water absorption rate of 5.9%. Its particle size ranged from 5 mm to 31.5 mm, which meets the requirements of the Chinese standard [26]. Tap water, which meets the standard requirements for concrete mixing and curing, was used throughout. The material properties of NA and RA are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Physical properties of coarse aggregates.

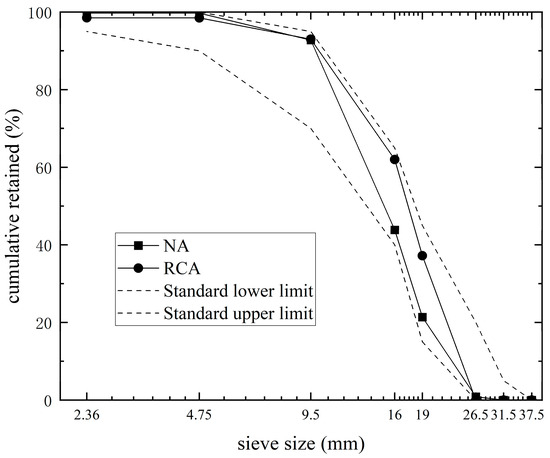

The particle size distributions of RAs and NAs are presented in Figure 1. While minor discrepancies exist in the particle size distribution between RAs and NAs, both aggregates comply with the upper and lower limits specified in the relevant standards. This finding demonstrates that RAs possess the necessary qualifications for practical engineering applications.

Figure 1.

Particle size distribution curves of recycled and natural coarse aggregates.

2.2. Mixing Ratios

In engineering applications, the substitution rate of recycled coarse aggregate is typically kept below 30% to ensure adequate mechanical performance [27,28]. However, in this study, substitution rates of 0%, 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100%, were used to investigate the performance degradation mechanisms of RAC and assess the feasibility of using high RA substitution levels. The NAC-0 with 0% recycled coarse aggregate content was used as the reference group. A 20% substitution rate (RCA-20) was used as the low substitution, which represents typical engineering practice. While the substitution rates of 40% (RCA-40) and 60% (RCA-60) were used to explore the possibility of higher replacement levels in real-world applications, 80% (RCA-80) and 100% (RCA-100) were used for the systematic study of the degradation behavior of RAC.

The mix proportions for each group are detailed below (Table 2). The reference mix (NAC) consisted of 190 parts water, 360 parts cement, 650 parts fine aggregate, and 1200 parts coarse aggregate, with a water–cement ratio of 0.54 and a target compressive strength of 35 MPa. The substitution rates (by weight) were denoted as NA-0, RCA-20, RCA-40, RCA-60, RCA-80, and RCA-100. We used concrete mix proportions for different levels of recycled aggregate substitution. A total of 144 cubic specimens (100 × 100 mm) and 72 prismatic specimens (100 × 300 mm) were prepared using plastic molds and compacting on a vibration table [29]. Recycled aggregate was not pre-wetted before casting [30,31]. After 24 h, all specimens were demolded and then cured at 20 ± 2 °C and 95% relative humidity for 3, 7, 14, and 56 days.

Table 2.

Concrete mix ratios for different levels of recycled aggregate substitution.

2.3. Test Method

The influence of different replacement rates of recycled coarse aggregates on the macro-mechanical properties of recycled concrete was investigated using concrete compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, and elastic modulus tests. The microstructure was observed using scanning electron microscopy to examine the microscopic morphology of RAC, while mercury intrusion porosimetry was used to determine the distribution of the micro-pore structure.

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of test data, three replicate specimens were prepared for each mix proportion. Specifically, 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm cubic specimens were cast for compressive strength tests, while 150 mm × 150 mm × 150 mm prismatic specimens were used for splitting tensile strength and elastic modulus measurements. The mechanical performance tests were conducted at curing ages of 3, 7, 14, and 56 days, respectively.

For microstructural characterization, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to observe the fracture surfaces of the tested specimens. The SEM was made form Tescan, Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. Representative samples with dimensions of approximately 10 mm × 10 mm × 5 mm were excised from either the fracture surface or cross-section of the specimens. These samples were first immersed in ethanol for 24 h to replace internal moisture and terminate hydration, then dried to a constant mass. Before SEM observation, a thin gold coating (approximately 10 nm in thickness) was sputtered onto the sample surfaces to enhance electrical conductivity. The SEM observations focused on the microstructural features, including micro-cracks, pore distribution, and the morphology of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ).

Mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) was utilized to analyze the micropore structure of RAC. Each MIP test sample (mass: approximately 2–3 g) was first subjected to ethanol replacement to halt the hydration process, followed by vacuum drying to a constant weight. The MIP tests were performed within a pressure range of 0–33,000 Psia, enabling the quantitative analysis of pore size distribution across a broad spectrum of micropore diameters.

3. Results

3.1. Mechanical Properties of RAC

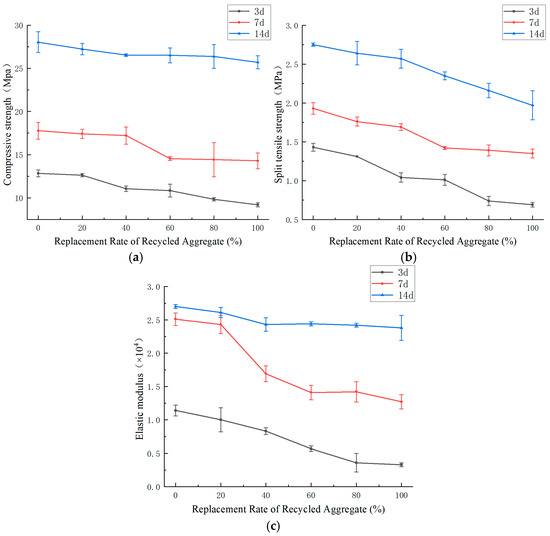

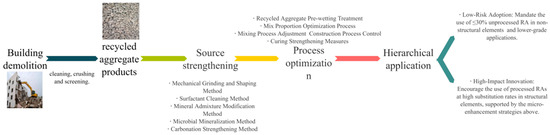

Figure 2 illustrates the mechanical properties of RAC at 3, 7, and 14 days for different replacement rates of RCA. The early-age mechanical properties of RAC are affected by both curing time age and RCA replacement rate.

Figure 2.

Early behavior of concrete (a) compressive strength, (b) split tensile strength, and (c) elastic modulus.

Compared with NCA, RCA has low strength (Table 3), reduced density, and higher porosity, so the early mechanical properties of RAC decline rapidly with the increase in the substitution rate of RCA. For RAC-100 (100% RCA), the 3-day compressive strength, tensile strength, and elastic modulus are 28%, 52%, and 71% lower, respectively, than those of NAC-0 (0% RCA). The substitution rate exerts the strongest effect on elastic modulus, followed by tensile strength, with compressive strength being the least affected. By 7 days of curing, the reductions in compressive strength, tensile strength, and elastic modulus for RAC-100 are 19%, 30%, and 49%, respectively, though the relative influence of RCA substitution rate remains consistent with the 3-day trend, but the degree of influence decreases.

Table 3.

Comparison of macro-mechanical properties between RAC and NAC.

Notably, the 14-day tensile strength becomes the most sensitive to RCA replacement, followed by elastic modulus, while compressive strength is the least affected—a reversal of the 3- and 7-day trends. After 14 days, the compressive strength approaches 75% of its final value, and the impact of RCA replacement on the performance is further reduced. The compressive strength, tensile strength, and elastic modulus of RAC-100 decrease by 8%, 28%, and 12%, respectively. In addition, the substitution rate of recycled aggregate has the greatest effect on tensile strength, followed by elastic modulus, and the lowest compressive strength, which shows a different law from 3 days to 7 days. The results suggest that the old mortar adhered to RCA, absorbed moisture during early hydration, slowing the reaction rate and reducing strength development. As the hydration reaction continues and internal humidity drops below 100%, the old mortar releases the absorbed water, which can mitigate self-shrinkage, promote the continuation of the hydration reaction, and thereby prevent the generation of micro-cracks [32]. Therefore, the early mechanical properties of RAC are not as good as those of NAC, but the effect of RA on concrete properties gradually weakens with the increasing age.

The effects of the early mechanical properties of RAC under different substitution rates are as follows: a 20% RCA substitution rate has little effect (<10% reduction) on early properties, except for a modest decline in the 3-day elastic modulus. When the substitution rate increases to 40%, significant reductions emerged for 3- and 7-day properties, while the compressive and tensile strength on the 7th day decreases significantly when the aggregate substitution rate reached 60%. After 14 days, the early mechanical properties of RAC were relatively less affected by the substitution rate of RCA. Therefore, the influence of RA substitution rate on early-age mechanical properties of concrete gradually weakens with curing time. For concrete structures requiring high early strength, RCA replacement rates must be strictly controlled, though these restrictions can be relaxed for long-term applications. Figure 3 presents the mechanical properties of RAC at 56 days. The later-stage performance decreases rapidly with the increase in the substitution rate of RCA. Compared to NAC-0, RAC-100 exhibits reductions of 35% in compressive strength, 15% in tensile strength, and 17% in elastic modulus. Here, compressive strength is the most sensitive to replacement rates, followed by elastic modulus, with tensile strength being the least affected.

Figure 3.

Later behavior of concrete (a) compressive strength, (b) split tensile strength, and (c) elastic modulus.

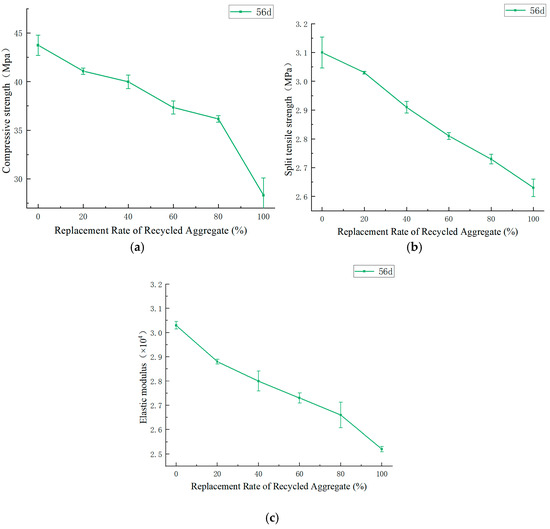

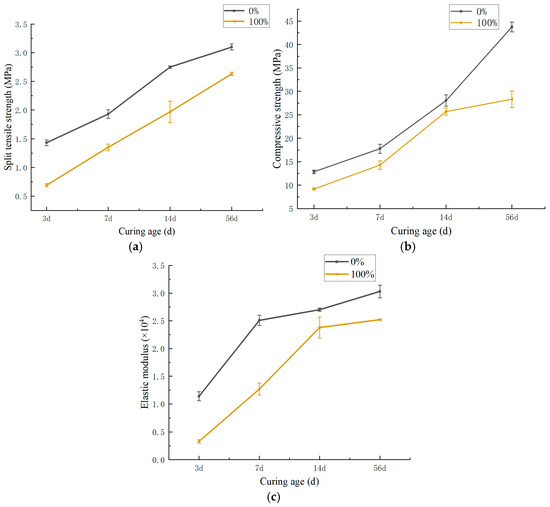

The effects of the later mechanical properties of RAC under different substitution rates are as follows (as shown in Figure 4): Mechanical properties grow rapidly in early stages but slow down after 14 days, which is in line with the strength development behavior of cement-based materials. Taking RAC-100 as an example, the 3-day, 7-day and 14-day compressive strengths are 32%, 50% and 91% of the 56 day compressive strength, while the 3-day, 7-day and 14-day tensile strengths are 26%, 51%, and 75% of the 56 day tensile strength, and the 3-d, 7-d, and 14 d elastic moduli are 13%, 50%, and 94% of the 56 day elastic modulus. In addition, the growth rate of mechanical properties of RAC in the early stage is basically the same as that of NAC, but after 14 days, the growth rate of mechanical properties of RAC is lower than that of NAC due to inherent defects of the RCA itself.

Figure 4.

Behavior of RAC-100 and NAC-0 (a) compressive strength, (b) split tensile strength, and (c) elastic modulus.

3.2. Microscopic Morphology of RAC

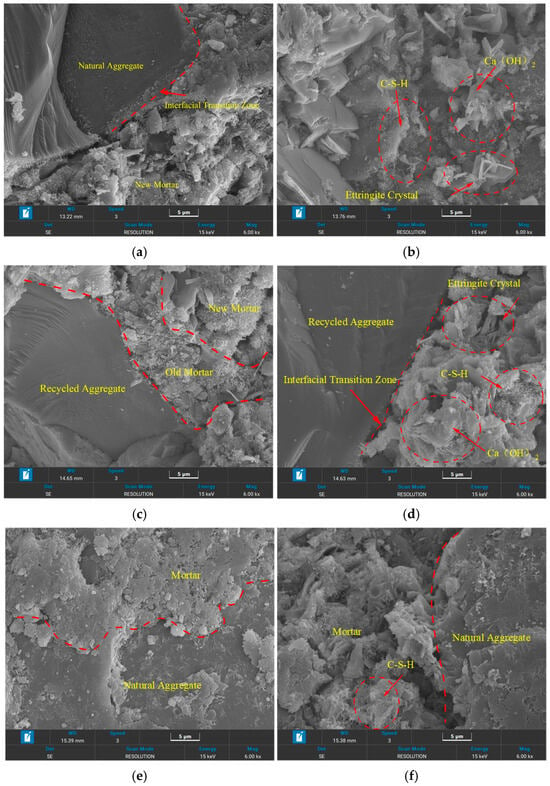

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to observe the microstructure of the aggregate–mortar interfacial transition zone (ITZ) in both NAC and RAC at early and later stages (as shown in Figure 5). SEM images were captured at 6000× magnification.

Figure 5.

Microscopic morphology of NAC-0 and RAC-100. (a,b) NAC-0 on the 3rd day, (c,d) RAC-100 on the 3rd day, (e,f) NAC-0 on the 56th day, and (g,h) RAC-100 on the 56th day.

The ITZ in RAC is more complex than that in NAC, consisting of natural aggregate, old mortar, new mortar, and interfaces between aggregate and old mortar, aggregate and new mortar, as well as between new and old mortar. Within these zones, granular calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H), acicular ettringite (aluminite), and tabular calcium hydroxide Ca(OH)2 crystals were observed. The ITZ in RAC is generally looser and more porous, with large porosity and low bond strength, which is the reason for the degradation of concrete performance. At 3 days of curing, concrete hydration is still in the accelerated stage, and hydration products such as C-S-H crystals are underdeveloped. As a result, the new mortar remains more porous and less compact than the old mortar (Figure 5a,b). In the RAC samples, the boundary between old and new mortar is not distinct, as the old mortar absorbs water and cement particles from the new mortar. This facilitates hydration and bonding, resulting in initial occlusion between the two phases (Figure 5c,d). Additionally, the surface of recycled aggregates absorbs water from the mix, effectively lowering the local water–cement ratio in the new mortar, which affects hydration.

At the aggregate–new mortar interface, hydration is insufficient, leading to a wider transition zone and reduced cohesiveness. Overall, early-stage hydration products are underdeveloped, and numerous internal pores form within the paste, resulting in lowering the early-age strength and elastic modulus of RAC. The presence of two weak interfaces in RAC, combined with the lower strength of recycled aggregate compared to natural aggregate, results in inferior early-age mechanical properties. With increasing curing age, the ITZ at the natural aggregate interface becomes denser. After 56 days of pouring, the cement matrix appears compact, and the ITZ is highly flocculated. However, the ITZ in RAC remains relatively porous and loose, with some unhydrated cement particles still present. Therefore, the combined effects of low-strength aggregate and a less robust ITZ contribute to the continued degradation of RAC’s mechanical properties at later stages.

3.3. Micro-Pore Structure

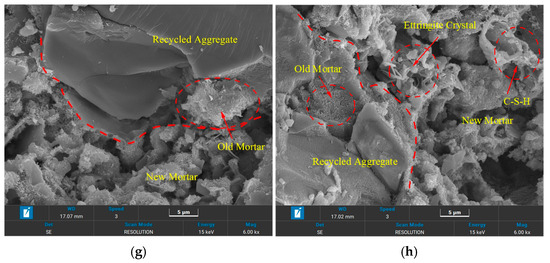

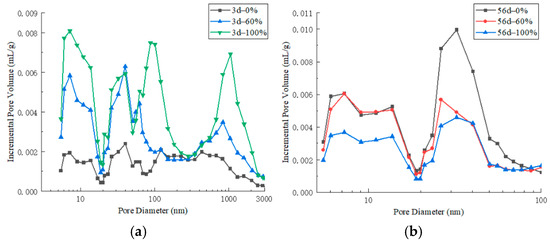

The pore structure of concrete plays a crucial role in determining its strength, water resistance, and durability, with key parameters (including pore size, porosity, and pore connectivity) exerting a significant influence on these macroscopic properties. In this study, mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) measurements were conducted using an AutoPore IV 9500 mercury porosimeter, covering a pore size testing range of 5 nm–200 μm (corresponding to a pressure range of 0–33,000 psia), and the contact angle was set at the porosimeter’s default value of 130°. The Mercury press instrument was made form Micromeritics Instrument Corporation, Norcross, GA, USA. The micropore structures of recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) cured for 3 and 56 days are presented in Table 4 and Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Table 4.

Early and later micro-pore structure characteristics of RAC.

Figure 6.

The pore size of RAC with different recycled aggregate substitution rates (a) on the 3rd day, and (b) on the 56th day.

Figure 7.

Cumulative pore size distribution of RAC with different recycled aggregate replacement rates (a) on the 3rd day, and (b) on the 56th day.

Table 4 presents the average pore size and porosity at early and later stages for various recycled aggregate substitution rates, with pore size distributions also shown in Figure 6. The findings indicate

(1) Early-stage microstructure: The microstructure of RAC varies significantly with different recycled aggregate substitution rates. As the substitution rate increases, the average pore size and apparent density decrease, while porosity increases. Specifically, for RAC-100, the average pore size and apparent density decrease by 19% and 13%, respectively, while porosity increases by 25%. This is attributed to the surface mortar of recycled aggregate absorbing water, thereby hindering early hydration reactions.

(2) Later-stage microstructure: As the hydration reaction progresses (at 56 days), the later microstructure of RAC with different replacement rates evolves significantly. With increasing RA content, the porosity of RAC decreases, while the average pore size and apparent density increase. In RAC, average pore size and apparent density increase by 15% and 3%, respectively, while porosity decreases by 24%. This suggests improved internal densification due to continued hydration over time. Pore sizes have a notable impact on concrete performance. Pores smaller than 100 μm are generally considered harmless, while those larger than 100 μm are harmful and can negatively affect the mechanical properties, durability, and permeability. The literature further categorizes pore sizes into four types: beneficial pores (0, 100 μm], low-harm pores (100, 1000 μm], medium-harm pores (1000, 10,000 μm], and high-harm pores (>10,000 μm) [33].

Figure 6a and Figure 7a show that early-age RAC contains a higher number of beneficial pores, low-harm, and medium-harm pores than NAC. As the recycled aggregate content increases, the number of harmful pores increases significantly. For instance, in RCA-100, mercury intrusion volumes at 100 μm and 1000 μm pores are approximately four times higher than those in RCA-0, which significantly impacts the macro-mechanical properties of the concrete. By 56 days (Figure 6b and Figure 7a), hydration reaction is nearly complete, and the number of harmful pores decreases. Many of the larger harmful pores transition into beneficial pores, indicating that pore size is no longer the dominant factor contributing to the performance degradation of RAC in the later stage.

The results of the mercury intrusion-expulsion tests are detailed in Table 5. The amount of residual mercury, calculated as the difference between mercury intrusion and expulsion, represents pore connectivity inside the concrete, which is a key indicator of permeability in cement-based materials. At early stages, residual mercury content in RAC increases with the substitution rate, indicating poorer pore connectivity and lower water resistance [34]. However, at 56 days, the residual mercury content in RAC decreases and becomes slightly lower than that of NAC, suggesting that the permeability of RAC is slightly better than that of NAC.

Table 5.

Residual mercury values of RAC at early and later stages.

These findings indicate that the micro-pore structure of RAC evolves significantly over time and with varying substitution rates, influencing its macroscopic behavior differently. To further elucidate the microscopic mechanisms behind performance degradation in RAC, subsequent sections will incorporate insights from the existing literature for comparative analysis and deeper discussion.

4. Discussion

The transition towards a circular economy in the construction sector is a global imperative, central to mitigating resource depletion and the environmental footprint of urbanization. This study systematically decouples the performance degradation of recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) through a multi-scale, two-stage lens, moving beyond descriptive property analysis to propose a mechanistic framework for deterioration. Our findings not only confirm the well-documented inferiority of RAC but also provide a temporal and spatial map of its degradation pathways, offering novel insights for targeted performance enhancement. The discussion that follows interprets these results within the broader context of international research and sustainable construction practices.

4.1. The Macro-Scale Imperative: Intrinsic Aggregate Deficits as the Primary Driver

The literature [6,7,8,9] reports that RAs generally exhibit lower strength and density, higher porosity, greater water absorption, higher clay content, and weaker bonding with new mortar compared to NAs. In this study, the crushing indices of RAs were 81% higher than that of NAs, and apparent density was 11.5% lower than that of NAs. These inherent weaknesses reduce the strength of the constituent materials and inevitably lead to a decrease in concrete strength. Moreover, the water absorption rate of RAs (5.9%) is significantly higher than NAs (1.3%). In the early stages of concrete pouring, the high-water absorption of RAs can cause a local water–cement ratio imbalance, further inhibiting the effective bonding of ITZ.

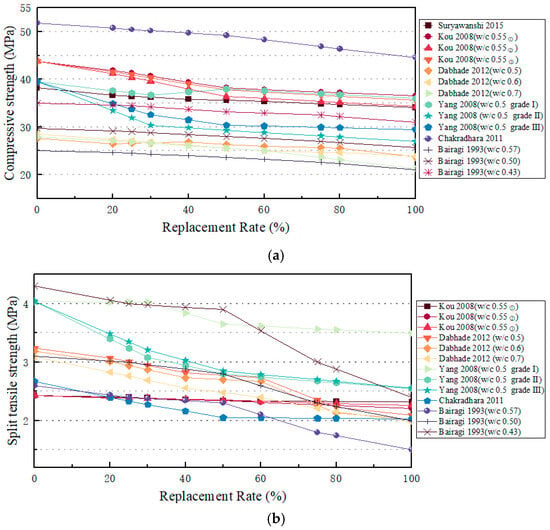

Under these adverse effects, the mechanical properties of RAs deteriorate with increasing RA substitution rates. At a constant water–cement (w/c) ratio, higher RA substitution significantly reduces the compressive strength of recycled concrete (Table A1, Figure 8). The compressive strength of fully recycled coarse aggregate concrete decreases by 12–40% [12,17,35], but when the substitution rate is not more than 30%, the decrease is negligible [18,36]. Splitting tensile and flexural strength of concrete depend on RA quality and surface characteristics. However, the roughness and water absorption capacity of the bonding mortar can enhance adhesion between aggregate and mortar [37,38]. Therefore, fully substituted RAC exhibits a 0–24% reduction in tensile strength [18,22,39]. The decrease in tensile strength is less severe than that of compressive strength. Furthermore, the splitting tensile strength of high-strength RAC is better than that of low-strength RAC [40]. The elastic modulus of concrete is heavily influenced by aggregate stiffness; it is disproportionately lower in RAC due to RAs’ low strength, high brittleness, and low elastic modulus [16,36,41], leading to a reduction in the elastic modulus of RAC compared to ordinary concrete, and this reduction escalating at higher substitution rates of RA [42]. Numerous studies have shown that the inherent defects of RAs are the primary cause of RAC’s deterioration in macroscopic properties, especially at high replacement rates. Therefore, in practical engineering applications, the substitution rate of RAs should be limited to no more than 30%. Additionally, it is recommended to adopt enhancement measures, e.g., mix design optimization, surface grinding/pre-wetting, and adding fly ash or fibers as external admixtures.

Figure 8.

Behavior of RAC from prior studies [8,13,14,17,18,38]: (a) compressive strength, (b) split tensile strength, and (c) elastic modulus. Note: ① Recycled aggregates are sourced from Tseung Kwan O, Hong Kong. ② Recycled aggregates are sourced from Tseung Kwan O and further crushed using hammers and hammer crushers. ③ Recycled aggregates are sourced from the old Kai Tak Airport in Hong Kong.

4.2. Microstructural Contribution to Performance Deterioration

4.2.1. Weak Interface Zones

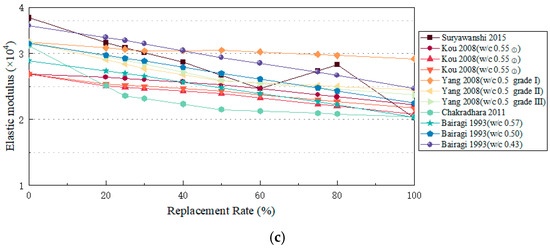

RAC is typically considered a five-phase composite material, consisting of natural aggregates, old ITZ, old mortar, new ITZ, and new mortar [22] (as shown in Figure 9). NAs are only present at the ITZ between mortar and aggregates. It is well known that the strength of concrete depends on the cement matrix and the bond strength between the aggregates and the matrix, which is the weakest link and a critical factor in determining the macroscopic mechanical properties of concrete [24]. In freshly mixed NAC, a water film forms around aggregates due to wetting and exudation effects. The w/c ratios at the interface can be twice the matrix average. As hydration progresses, the water fills these zones with denser hydrates.

Figure 9.

Composite material phases of concrete (a) NAC and (b) RAC.

In RAC, however, the high porosity and water absorption capacity of RAs lead to significant water absorption in the early stages of hydration, resulting in an open and loose ITZ in the hardened concrete. These findings are consistent with the research results presented in this paper, particularly in the later stages of hydration, where the looseness and low bond strength at the RA interface are more pronounced compared to the NA interface. The complex interface in RAC not only increases the number of weak interfaces but also reduces the density and bond strength of some bonded interfaces, which is a primary factor contributing to the deterioration of the macroscopic properties of recycled concrete. Therefore, the ITZ in RAC exhibits lower density and bond strength than NAC, exacerbating macroscopic degradation.

4.2.2. Micropore Structure

Porosity and pore size distribution critically influence RAC’s macro-mechanical properties and durability performance.

In the early stages of RAC, the water absorption of the old mortar on the surface of the RAs leads to an increase in early porosity (as shown in Table 1), which aligns with the findings of the existing research [24]. This study indicates that RAC exhibits a significant number of medium and large harmful pores early on, which can reduce the concrete’s strength, durability, and permeability. The high porosity and the presence of harmful pores hinder the hydration reaction, leading to a slow development of early strength. As the hydration reaction progresses, the free water absorbed by RAs during the initial stage of hydration is gradually released, maintaining the hydration reaction, and the newly formed hydrates gradually fill these areas. Consequently, in later stages of RAC, the number of cement pores smaller than 100 μm increases, while the number of harmful pores larger than 100 μm decreases, indicating that the continuation of the hydration reaction has improved the micro-pore structure of the concrete to some extent. However, despite the improvement in pore structure later on, the mechanical properties of RAC remain lower than those of NAC (Figure 2 and Figure 3), suggesting that the characteristics of RAs and their complex, fragile ITZ have a more significant impact on concrete performance.

Based on the research results of other scholars on the degradation mechanisms of recycled aggregate concrete, it can be seen that at the microscopic level, recycled aggregate concrete has a large number of weak interfacial zones and high porosity, which leads to a decline in macroscopic performance. However, the aforementioned studies did not consider the effect of age. The ‘two-stage deterioration mechanism’ proposed in this paper, for the first time, takes age as a core variable, dividing it into early and late stages: the early performance degradation of RAC is caused by the combined effect of high porosity and weak interfacial zones, while in the later stage, as the microscopic arch structure improves, the deterioration of macroscopic performance is mainly caused by multiple weak transition zones.

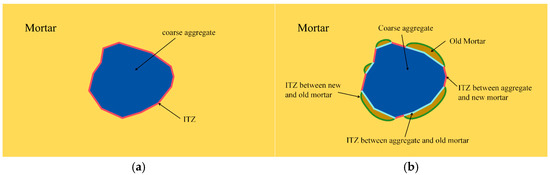

4.3. Suggestions for the Promotion of RAC

The compressive strength, tensile strength, and elastic modulus of RAC in the early and later stages were lower than those of NAC, and decreased with the increase in substitution rates. The recycled aggregate with low strength and low elastic modulus is the main macroscopic cause of RAC performance deterioration. Moreover, at the micro level, the early degradation of RAC is caused by the combination of high porosity and weak interface zone, while the performance deterioration is mainly caused by multiple weak transition zones in the later stage. Based on the performance deterioration mechanism of RAC, the performance and utilization of RAC can be improved by following the principle of “source strengthening, process optimization, and hierarchical application” in practical applications (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of improvement principles for RAC.

(1) Source strengthening: improve the quality of the recycled aggregate itself.

Defects of RA are the main cause of RAC performance deterioration. Therefore, the surface mortar can be physically removed before pouring concrete, or carbonation treatment can be used to generate CaCO3 to improve the compactness and strength of RA. The above aggregate strengthening measures can avoid water absorption of the old mortar in the early stage, and reduce the weak surface of the transition zone in the later stage.

(2) Process optimization: improve concrete mix ratio and microstructure.

The early deterioration of RAC is associated with high porosity, so the pre-wetting of RA and the use of superplasticizer can reduce the influence of water absorption of old mortar on the hydration reaction during pouring. The weak interfacial transition zone is the key to the deterioration of RAC performance in the early and late stages, so in addition to RA reinforcement, mineral admixtures, fibers, and other materials can be added to improve the transition zone. Fly ash and slag powder belong to industrial solid waste, while fibers can be used from waste plastics and waste rubber recycled fibers, which is more conducive to the recycling of urban solid waste.

(3) Hierarchical application: A Tiered Application Strategy: Global policy must promote a tiered approach:

- Low-Risk Adoption: Mandate the use of ≤30% unprocessed RA in non-structural elements (blocks and pavers) and lower-grade applications (road sub-bases). The recommended aggregate gradation shall comply with standards (e.g., 4.75–19 mm continuous gradation), with a water–cement ratio controlled at 0.50–0.55. Construction process optimization includes adopting medium-frequency vibration (30–50 Hz) for compaction to ensure workability, and extending curing duration to 7–14 days under standard conditions (20 ± 2 °C, RH ≥ 90%). This is a readily achievable goal that can massively divert C&D waste from landfills, as seen in European directives.

- High-Impact Innovation: Encourage the use of processed RAs (strengthened, low-absorption) at high substitution rates (>50%) in structural elements, supported by the micro-enhancement strategies above. The design parameters shall specify a RA water absorption rate ≤3% (after pre-treatment), aggregate crushing value ≤25%, and a water–cement ratio adjusted to 0.40–0.45 with the addition of 0.8–1.2% polycarboxylate superplasticizer. Construction processes require pre-wetting RA to a saturated surface-dry state (moisture content 5–8%) to avoid internal curing deficiency, adopting layered compaction (layer thickness ≤200 mm) with high-frequency vibration (50–80 Hz), and implementing steam curing (40–50 °C, 48 h) for early strength development. This represents the frontier of circular construction and should be supported by performance-based codes rather than prescriptive limits.

In addition, it is necessary to promote the revision of the current specification and add the technical terms and performance indicators for the application of medium- and high-replacement-rate RAC in non-load-bearing fields to provide a basis for design and construction.

4.4. Research Limitations and Future Research

Based on experimental investigations and findings from the existing literature, this study constructs a two-stage performance degradation mechanism for RAC and puts forward corresponding recommendations for its engineering applications. However, the current results primarily focus on the fundamental macroscopic properties of RAC (i.e., compressive strength and tensile strength), with shear and flexural performances remaining unexplored. In terms of microstructural analysis, the research mainly relies on pore structure distribution characteristics, and no in-depth quantitative analysis of the ITZ has been conducted via SEM. Additionally, although the proposed strategy of “source strengthening, process optimization, and hierarchical application” emphasizes the engineering practice of RAC, a comprehensive research framework integrating theory with practice for RAC has not been systematically established. Further refinement is therefore required to enhance the practical relevance and applicability of the research outcomes.

Future research will focus on three key aspects: (1) Clearly define the measurable criteria to determine the boundary between these two stages, and improve the RAC two-stage degradation mechanism. (2) Establish cross-scale correlation models between various macroscopic performances and microstructure of RAC using machine learning algorithms and other analytical systems, and conduct in-depth sensitivity analysis of various influencing factors. (3) Enhance the quantitative analysis of scanning electron microscopy with microstructural analysis, including ITZ thickness or microhardness. (4) Advance a comprehensive “RAC degradation mechanism-modification technology-engineering application-lifespan prediction” framework, with emphasis on the influence of RA micro-cracks on two-stage degradation and the development of multi-scale-based lifespan prediction models.

5. Conclusions

This study establishes a cross-scale, two-stage deterioration mechanism, which lays a solid scientific foundation for advancing recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) from a niche green material to a mainstream construction resource. The degradation process is initiated by the inherent macroscopic properties of recycled aggregates (RA) and regulated by the evolution of microporosity and the stability of multiphase interfaces. The two-stage degradation of RAC is characterized by a critical turning point: in the early stage, performance degradation is primarily induced by the synergistic effects of high initial porosity and weak interfacial transition zones (ITZ); in the later stage, cumulative damage to multiphase interfaces dominates, leading to accelerated performance deterioration. Building on the aforementioned research findings, the ultimately proposed utilization strategies for recycled concrete offer actionable engineering guidance encompassing three core dimensions: “source strengthening, process optimization, and hierarchical application.”

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.W. and X.Y.; data curation, B.C., A.H. and X.Y.; funding acquisition, P.W.; investigation, B.C.; methodology, P.W. and J.D.; project administration, P.W.; supervision, B.C.; validation, B.C., A.H. and J.D.; writing—original draft, B.C. and P.W.; writing—review and editing, P.W., B.C. and A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), grant number 52300233. The APC was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Literature comparisons.

Table A1.

Literature comparisons.

| Index | Replacement Rate | Remark | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 20% | 25% | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% | 75% | 80% | 100% | ||

| fc | 0 | 4.03 | 6.21 | 7.41 | 9.16 | 10.71 | [8] w/c 0.5 | ||||

| ft | 0 | 1.86 | 18.93 | 30.23 | 20.06 | 42.94 | |||||

| fc | 0 | 4.34 | 12.79 | 16.67 | [13] w/c 0.55 ① | ||||||

| ft | 0 | 1.86 | 5.95 | 17.47 | |||||||

| Et | 0 | 0.82 | 3.70 | 4.53 | |||||||

| fc | 0 | 5.94 | 16.89 | 21.69 | [13] w/c 0.55 ② | ||||||

| ft | 0 | 6.69 | 11.15 | 22.68 | |||||||

| Et | 0 | 1.65 | 3.70 | 9.05 | |||||||

| fc | 0 | 5.02 | 13.70 | 18.72 | [13] w/c 0.55 ③ | ||||||

| ft | 0 | 5.58 | 9.67 | 19.33 | |||||||

| Et | 0 | 1.23 | 3.29 | 7.00 | |||||||

| fc | 0 | 4.12 | 3.07 | 6.32 | 7.87 | 23.73 | [14] w/c 0.5 | ||||

| Et | 0 | 5.25 | 12.96 | 15.74 | 31.17 | 35.49 | |||||

| fc | 0 | 3.93 | 8.17 | 12.37 | 13.70 | 16.30 | [14] w/c 0.6 | ||||

| Et | 0 | 5.64 | 14.42 | 16.30 | 33.23 | 36.38 | |||||

| fc | 0 | 2.76 | 6.45 | 10.33 | 17.10 | 23.56 | [14] w/c 0.7 | ||||

| Et | 0 | 8.40 | 17.15 | 22.33 | 30.42 | 35.92 | |||||

| fc | 0 | 7.09 | 3.80 | 8.86 | [17] w/c 0.5 grade ① | ||||||

| ft | 0 | 4.10 | 3.79 | 7.89 | |||||||

| Et | 0 | 0.25 | 9.65 | 13.61 | |||||||

| fc | 0 | 23.04 | 25.82 | 31.65 | [17] w/c 0.5 grade ② | ||||||

| ft | 0 | 12.62 | 18.61 | 22.71 | |||||||

| Et | 0 | 23.76 | 30.69 | 36.88 | |||||||

| fc | 0 | 17.47 | 23.04 | 25.32 | [17] w/c 0.5 grade ③ | ||||||

| ft | 0 | 10.41 | 18.30 | 25.24 | |||||||

| Et | 0 | 20.54 | 29.46 | 36.63 | |||||||

| fc | 0 | 2.64 | 5.06 | 14.07 | [18] w/c 0.43 | ||||||

| ft | 0 | 24.36 | 31.09 | 34.62 | |||||||

| Et | 0 | 12.73 | 23.22 | 23.97 | |||||||

| fc | 0 | 2.39 | 5.98 | 9.96 | 16.33 | [38] w/c 0.57 | |||||

| ft | 0 | 6.57 | 14.19 | 21.45 | 29.76 | ||||||

| Et | 0 | 7.69 | 11.54 | 30.77 | 42.31 | ||||||

| fc | 0 | 2.36 | 5.72 | 9.09 | 13.47 | [38] w/c 0.50 | |||||

| ft | 0 | 6.98 | 14.29 | 21.27 | 28.57 | ||||||

| Et | 0 | 3.23 | 9.68 | 25.81 | 35.48 | ||||||

| fc | 0 | 1.43 | 5.14 | 7.14 | 11.43 | [38] w/c 0.43 | |||||

| ft | 0 | 6.43 | 14.04 | 20.47 | 27.78 | ||||||

| Et | 0 | 6.98 | 9.30 | 30.23 | 44.91 | ||||||

Note: ① Recycled aggregates are sourced from Tseung Kwan O, Hong Kong. ② Recycled aggregates are sourced from Tseung Kwan O and further crushed using hammers and hammer crushers. ③ Recycled aggregates are sourced from the old Kai Tak Airport in Hong Kong.

References

- Ginga, C.P.; Ongpeng, J.M.C.; Daly, M.K.M. Circular Economy on Construction and Demolition Waste: A Literature Review on Material Recovery and Production. Materials 2020, 13, 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villoria Sáez, P.; Osmani, M. A Diagnosis of Construction and Demolition Waste Generation and Recovery Practice in the European Union. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomer Mendoza, F.J.; Esteban Altabella, J.; Gallardo Izquierdo, A. Application of Inert Wastes in the Construction, Operation and Closure of Landfills: Calculation Tool. Waste Manag. 2017, 59, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Morales, M.; Zamorano, M.; Ruiz-Moyano, A.; Valverde-Espinosa, I. Characterization of Recycled Aggregates Construction and Demolition Waste for Concrete Production Following the Spanish Structural Concrete Code EHE-08. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; da Silva, P.R.; de Brito, J. Self-Compacting Concrete with Recycled Aggregates—A Literature Review. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 22, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, C.S.; Chan, D. Feasible Use of Recycled Concrete Aggregates and Crushed Clay Brick as Unbound Road Sub-Base. Constr. Build. Mater. 2006, 20, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chini, A.R.; Kuo, S.-S.; Armaghani, J.M.; Duxbury, J.P. Test of Recycled Concrete Aggregate in Accelerated Test Track. J. Transp. Eng. 2001, 127, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryawanshi, S.R.; Singh, B.; Bhargava, P. Characterization of Recycled Aggregate Concrete. In Advances in Structural Engineering; Matsagar, V., Ed.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 1813–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verian, K.P.; Ashraf, W.; Cao, Y. Properties of Recycled Concrete Aggregate and Their Influence in New Concrete Production. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 133, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.H.; Poon, C.S. Properties of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Made with Recycled Aggregates with Different Amounts of Old Adhered Mortars. Mater. Des. 2014, 58, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.S.; Choi, H.B. Effects of the Old Cement Mortar Attached to the Recycled Aggregate Surface on the Bond Characteristics between Aggregate and Cement Mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 59, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahal, K. Mechanical Properties of Concrete with Recycled Coarse Aggregate. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, S.-C.; Poon, C.-S. Mechanical Properties of 5-Year-Old Concrete Prepared with Recycled Aggregates Obtained from Three Different Sources. Mag. Concr. Res. 2008, 60, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabhade, A.N.; Choudhari, D.S.R.; Gajbhiye, D.A.R. Performance Evaluation of Recycled Aggregate Used in Concrete. Int. J. Eng. 2012, 2, 1387–1391. [Google Scholar]

- Etxeberria, M.; Vázquez, E.; Marí, A. Microstructure Analysis of Hardened Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Mag. Concr. Res. 2006, 58, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, W.; Fan, Y.; Huang, X. An Overview of Study on Recycled Aggregate Concrete in China (1996–2011). Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 31, 364–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.-H.; Chung, H.-S.; Ashour, A. Influence of Type and Replacement Level of Recycled Aggregates on Concrete Properties; University of Bradford: Bradford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chakradhara Rao, M.; Bhattacharyya, S.K.; Barai, S.V. Influence of Field Recycled Coarse Aggregate on Properties of Concrete. Mater. Struct. 2011, 44, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajdukiewicz, A.; Kliszczewicz, A. Influence of Recycled Aggregates on Mechanical Properties of HS/HPC. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2002, 24, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.V.; De Brito, J.; Dhir, R.K. Fresh-State Performance of Recycled Aggregate Concrete: A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 178, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Shi, C.; Guan, X.; Zhu, J.; Ding, Y.; Ling, T.-C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Durability of Recycled Aggregate Concrete—A Review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 89, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, G.; Savva, P.; Petrou, M.F. Enhancing Mechanical and Durability Properties of Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 158, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.V.; Neves, R.; De Brito, J.; Dhir, R.K. Carbonation Behaviour of Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 62, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, C.S.; Shui, Z.H.; Lam, L. Effect of Microstructure of ITZ on Compressive Strength of Concrete Prepared with Recycled Aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2004, 18, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Wang, W.H.; Lin, H.L.; Liu, Z.X.; Liu, J. Experimental Study on Interfacial Strength of the High Performance Recycled Aggregate Concrete. In Earth and Space 2010: Engineering, Science, Construction, and Operations in Challenging Environments; American Society of Civil Engineers: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2010; pp. 2821–2828. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Yao, Y.; Wang, X.; Wei, J.; Feng, Z. Preparation of Recycled and Multi-Recycled Coarse Aggregates Concrete with the Vibration Mixing Process. Buildings 2022, 12, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Li, X.; Song, J.; Fang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Bu, S. Experimental Study on Flexural Capacity of PVA Fiber-Reinforced Recycled Concrete Slabs. Archiv. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2021, 21, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lv, Z.; Zhu, C.; Bai, G.; Zhang, Y. Study on Calculation Method of Long-Term Deformation of RAC Beam Based on Creep Adjustment Coefficient. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 23, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wu, F.; Xia, D.; Li, Y.; Cui, K.; Wu, F.; Yu, J. Compressive and Flexural Behavior of Alkali-Activated Slag-Based Concrete: Effect of Recycled Aggregate Content. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 67, 105993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Li, X.; Wei, M.; Xie, Q. Experimental Study on Carbonization and Strengthening Performance of Recycled Aggregate. Buildings 2025, 15, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjari, M.; Marouf, H.; Dahou, Z.; Maherzi, W. Investigation of the Mechanical and Fracture Properties of Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Buildings 2025, 15, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestle, N.; Kühn, A.; Friedemann, K.; Horch, C.; Stallmach, F.; Herth, G. Water Balance and Pore Structure Development in Cementitious Materials in Internal Curing with Modified Superabsorbent Polymer Studied by NMR. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2009, 125, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Huo, G.; Xie, L.; Meng, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhuo, Y. Analysis of Pore Structure and Mechanical Properties of Recycled Concrete with Full Replacement of Coarse Aggregate. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 43, 3005–3016+3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, L.; West, J.S.; Tighe, S.L. The Effect of Recycled Concrete Aggregate Properties on the Bond Strength between RCA Concrete and Steel Reinforcement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 1037–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbachiya, M.; Meddah, M.S.; Ouchagour, Y. Use of Recycled Concrete Aggregate in Fly-Ash Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 27, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Bai, G.; Zhu, C. Study on the Effect of Chloride Ion Ingress on the Pore Structure of the Attached Mortar of Recycled Concrete Coarse Aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 263, 120123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxeberria, M.; Vázquez, E.; Marí, A.; Barra, M. Influence of Amount of Recycled Coarse Aggregates and Production Process on Properties of Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairagi, N.K.; Ravande, K.; Pareek, V.K. Behaviour of Concrete with Different Proportions of Natural and Recycled Aggregates. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 1993, 9, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Chong, L.; Xie, Z. Performance Enhancement of Recycled Concrete Aggregate—A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, D.; De Brito, J.; Rosa, A.; Pedro, D. Mechanical Properties of Concrete Produced with Recycled Coarse Aggregates—Influence of the Use of Superplasticizers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 44, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, W.; Poon, C. Recent Studies on Mechanical Properties of Recycled Aggregate Concrete in China—A Review. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2012, 55, 1463–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacintho, A.E.P.G.D.A.; Cavaliere, I.S.G.; Pimentel, L.L.; Forti, N.C.S. Modulus and Strength of Concretes with Alternative Materials. Materials 2020, 13, 4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).