Abstract

Based on the characteristics and distribution patterns of collapsed holes in cast-in-place bored pile foundations in the typical coastal area of Guangdong Petrochemical Company, the deformation and collapse behavior of pile walls in the project zone were systematically monitored and measured using a specialized pore diameter detection system for cast-in-place bored pile quality assessment. A collapse rate parameter is proposed and established as an evaluation index for pile wall stability and collapse. Using the basic principles of Quantification Theory I and considering the collapse characteristics of pile walls in a cast-in-place bored pile project in Guangdong, the influencing factors and mechanisms of pile wall collapse are comprehensively analyzed and evaluated. A quantitative theoretical evaluation model for the influencing factors of pile wall collapse is then established. Focusing on the construction technology of cast-in-place bored piles, the proposed quantitative theoretical evaluation model is applied to quantitatively analyze and assess the factors contributing to pile wall collapse in the project area. The relationships between pile wall collapse rate in the Guangdong Petrochemical Company cast-in-place bored pile project and influencing factors such as stratum structure, soil properties, sand layer thickness, drilling depth, and drilling methods are systematically determined. The primary collapse factors and secondary influencing factors in the pile wall collapse of the cast-in-place bored pile engineering zone are identified, providing a theoretical basis for determining optimal prevention and control measures against pile wall collapse during the drilling process of cast-in-place bored piles.

1. Introduction

Weak clayey soil layers deposited under marine, lacustrine, and fluvial environments are widely distributed in the coastal areas of southeastern China. These layers are typically characterized by high water content, low strength, high compressibility, poor permeability, and considerable thickness. Under loading, such soils undergo significant settlement, and their bearing capacity and stability often fail to meet engineering requirements. Cast-in-place bored piles are widely used in modern foundation engineering in coastal areas due to their high bearing capacity, non-squeezing of soil, vibration-free construction, low noise, and suitability for densely built urban environments. However, hole-wall instability in cast-in-place bored piles is a major engineering challenge commonly encountered during construction. Slight negligence during construction may easily cause quality problems such as diameter reduction and hole-wall collapse. Hole-wall stability strongly affects construction progress, increases construction cost, reduces the bearing capacity of pile foundations, and seriously restricts the application and development of cast-in-place bored piles. Hole-wall collapse of cast-in-place bored piles has long been a key factor affecting and determining the engineering quality and construction progress of such foundations, and it has gradually become a “bottleneck” for many large-diameter cast-in-place bored pile projects [1,2]. The development of hole-wall instability and eventual collapse is a nonlinear and complex system process closely related to regional engineering geological conditions and construction technology. It usually results from the combined action of multiple factors affecting hole-wall stability [3]. The effects and importance of the various collapse-inducing factors differ, and both the composition and mechanism of collapse are highly complex. Therefore, accurately analyzing and evaluating the influencing factors of hole-wall stability and determining the primary and secondary collapse factors for cast-in-place bored piles are of great practical significance for the scientific prevention and control of hole-wall collapse.

At present, many scholars have studied the evaluation and prevention of hole-wall collapse in cast-in-place bored piles. Gnirk (1972) [4] systematically analyzed hole-wall stability using finite deformation theory and established an elastic–plastic mechanical model of borehole shrinkage based on the Mohr–Coulomb criterion. Roegiers (2002) [5] simplified the formation as a porous elastic medium, incorporated multiple factors in the analysis of hole-wall stability, and concluded that the strength of the soil surrounding the hole and the specific weight of the fluid in the hole jointly determine the stability of the hole-wall. Hu (2007) [6] analyzed the stress at the pile hole edge of cast-in-place bored piles, derived an analytical expression for the edge stress, and pointed out that adjusting mud depth can effectively prevent hole-wall collapse. Papamichos (2010) [7], based on bifurcation theory, used a Mohr–Coulomb elastoplastic constitutive model to predict borehole failure under various axial and radial loads, and verified the accuracy of the predictions using experimental data. Wang (2011) [8] used finite element software combined with engineering practice to simulate and determine the relationship between soil properties, stabilizing fluid-specific gravity, hole depth, hole diameter, and hole-wall stability for cast-in-place bored piles. Alkroosh (2015) [9] used the least squares support vector machine (LSSVM) algorithm to predict the bearing capacity of cast-in-place bored piles. Compared with traditional methods, including the GEP model, this algorithm provided more accurate predictions of the bearing capacity and stability of cast-in-place bored piles. Gao and Wen (2018) [10] studied the concrete hydration model with temperature tracking and concluded that the applicability of cast-in-place bored piles in permafrost regions can be enhanced by increasing pile diameter and formation temperature. Lee (2018) [11] proposed a nondestructive method using electromagnetic waves to detect necking defects in cast-in-place bored piles. The defect locations experimentally obtained agreed well with actual positions, indicating that electromagnetic waves can effectively detect shrinkage defects at various positions in bored piles. Gao and Zhuang (2019) [12], based on engineering case studies, concluded that the Benoto cast-in-place bored pile construction method can effectively reduce lateral displacement and hole-wall collapse, thereby mitigating the impact of pile construction on adjacent tunnels. Ding (2019) [13] developed a new model based on poro-elasticity and comprehensively analyzed the influence of bedding permeability anisotropy on borehole stability. Gao (2020) [14] discussed the influence of a ventilation opening structure (VOS) on pile–soil interface temperature and the bearing capacity of cast-in-place bored piles. The results show that the VOS can enhance pile stability and significantly reduce the designed pile length. Lin et al. (2020) [15] used discrete element numerical simulations to study the effect of borehole fractures and their size on horizontal stress, while comprehensively considering the influence of temperature. Chen (2020) [16] considered factors such as sand internal friction angle, borehole diameter, groundwater level, and wall-protection mud, and studied their influence on hole-wall stability of cast-in-place bored piles through numerical simulations. A gray variable-weight comprehensive evaluation model and evaluation method for hole-wall stability were established. Cai (2022) [17] proposed injecting chemical grout into the influence zone of anchor holes in sand layers to improve impermeability and stability via cementation. Wang et al. (2022) [18] proposed a technical solution for synchronous data acquisition and concrete thickness detection, using ultrasonic methods based on inclined and vertical reflections of full pulse signals in bored piles. Yang et al. (2023) [19] established a borehole wall stability model through a combination of theoretical research and field tests. By analyzing the critical stress state of borehole wall soils and establishing the relationship between mud parameters and the critical borehole wall stress, they determined optimal mud densities for different strata, thereby providing a theoretical basis for borehole wall stability during construction. Wang (2024) [20] categorized the factors influencing borehole wall stability into pile hole design parameters, construction techniques, and soil properties. Among design parameters, aperture and depth are key factors. In construction techniques, mud density, casing depth, and drilling time are critical. Regarding soil properties, soil type and physical–mechanical characteristics are the primary controlling factors. Wang and Liu (2024) [21] proposed a method for detecting defects in underwater bored pile borehole walls by employing optical image acquisition technology tailored to the complex underwater environment of bored piles. Su (2024) [22] effectively mitigated hole collapse by implementing measures such as restricting nearby vibration operations, extending casing length, increasing mud viscosity, adopting slow-pressure and slow-lift drilling, reducing drilling speed, and shortening process times. Zhang (2025) [23] used gray relational analysis to calculate the correlation between different collapse-inducing factors and collapse rate and analyzed how these factors affect hole-wall stability.

In general, current representative methods for analyzing and evaluating influencing factors and stability of hole walls in cast-in-place bored piles can be divided into three categories.

1. Mechanical analysis models. These models deduce the relationship between hole-wall stability and influencing factors by analyzing stress distribution around the hole under various conditions and then propose corresponding anti-collapse measures. However, many assumptions are required, and it is difficult to account for qualitative factors.

2. Finite element simulations. Finite element software such as ABAQUS, ANSYS, and FLAC3D is used to simulate and analyze factors affecting hole-wall stability, qualitatively distinguish stability levels, and propose treatment measures. However, these analyses are usually project-specific and cannot provide a unified method, which limits their applicability and promotion.

3. Quantitative and semi-quantitative methods. These are based on statistics, operations research, systems science, and related disciplines. Models are established using statistical data, and collapse-inducing factors are analyzed quantitatively. However, these models generally only handle quantitative factors and cannot effectively address qualitative factors, resulting in discrepancies between quantitative indices and actual conditions.

This paper is based on the research project “Evaluation of Borehole Wall Stability and Reinforcement Methods for Collapsed Holes in Cast-in-Place Pile Construction for the Guangdong Petrochemical Project.” The Guangdong Petrochemical Project has a construction period exceeding four years and an investment of more than 50 billion yuan. The cost of foundation and ground treatment alone approaches 2 billion yuan, with a duration of more than one year. The construction site is located in a coastal and riverbank area with poor geological conditions, featuring soft soil and fill. The upper layers mainly consist of Quaternary aeolian–aqueous silty fine sand and mucky clay. The underlying mucky clay is in a soft-to-hard plastic state with unfavorable properties such as low strength, high void ratio, high organic content, high compressibility, and pronounced rheological behavior.

Due to these unique geological and hydrogeological conditions, approximately 2000 cast-in-place piles in the first to fourth joint facilities of the Guangdong Petrochemical Project experienced severe borehole collapse during drilling, particularly at depths of 4–10 m. Borehole wall instability not only compromises pile quality and poses significant safety risks but also causes serious construction delays and economic losses. Therefore, evaluating borehole wall stability and developing effective reinforcement methods for collapsed holes in cast-in-place pile construction are urgent issues.

In view of the limitations and shortcomings of existing evaluation methods for hole-wall collapse factors, this study adopts Quantification Theory I to quantitatively analyze and evaluate both qualitative and quantitative factors influencing hole-wall stability of cast-in-place bored piles. A correlation evaluation model for qualitative and quantitative collapse factors is established to determine primary and secondary collapse factors. On this basis, key collapse factors can be targeted for prevention and control in cast-in-place bored pile projects, increasing prevention efficiency, reducing construction costs, and ensuring safety and stability during cast-in-place bored pile construction.

2. Basic Principle of Quantification Theory I

Quantification Theory I shares methodological similarities with several statistical and machine learning approaches, including multiple linear regression, BP neural network regression, and fuzzy quantification theory [24]. However, it stands out for its superior handling of qualitative data, high interpretability, and broad applicability. These advantages make it particularly suitable for multivariate analyses involving relationships between qualitative and quantitative variables.

In this paper, Quantification Theory I is used to transform data that cannot be directly expressed quantitatively into numerical form, thereby enabling statistical evaluation and judgment. It provides a mathematical-statistical framework for quantifying qualitative problems and establishing corresponding mathematical models. This approach allows full use of qualitative and quantitative information about geological conditions and human factors and enables quantitative treatment of engineering problems that are otherwise difficult to analyze in detail. It is of great significance for comprehensively identifying and analyzing relationships and patterns among variables.

In the quantification process, Quantification Theory I converts binary qualitative judgments such as {Yes, No} into {1, 0}, assigns values to qualitative factors, and uses these to conduct prediction, classification, and ranking. This reduces subjective human bias and yields more accurate mathematical evaluation models. As a result, Quantification Theory I has been widely applied in sociology, engineering, medicine, forestry, and other fields.

2.1. Items, Categories, and Their Response Matrices in Quantification Theory I

In the quantitative theory I, the qualitative explanatory variables on which the quantitative reference variable depends are often called Item, while the values of different states of the project are called Category. Now consider m explanatory variables (projects) to predict the quantitative reference variable . Suppose the first project has categories, the second project has categories, , the project has categories, , there is category. Refer to as the reflection of category k of j project in the i sample, and determine it according to the following Equation (1):

If quantitative variables and qualitative variables are considered at the same time, assuming that the data of quantitative variables in the sample is , the response matrix with both qualitative and quantitative variables is as follows:

2.2. Establishment of Mathematical Evaluation Model

In Quantitative Theory I, it is assumed that the response between reference variable and qualitative variables (items, categories) satisfies the following linear model:

where is the measured value of the reference variable y in the i sample; bjk is the constant coefficient of item j, category k; and is the random error value.

The least square estimation of the coefficient is calculated according to the basic principle of the least square method, and the calculation process is as follows:

The value that can be obtained by making the partial derivative of the relation q to be equal to 0.

After solving for , the prediction equation containing only qualitative variables can be obtained.

Equation (5) is expressed in rectangular form: , where X is the sample response matrix, Y is the sample matrix, b is the coefficient matrix, and E is the random error matrix. Then the minimum estimated value of the coefficient of the normal prediction equation is as follows:

According to Equation (6), the expression of the estimated value of the dependent variable can be established as follows:

In the case of both qualitative and quantitative variables, the prediction model should satisfy the following linear equations:

According to the basic principle of the least square method, the linear unbiased estimates and of the minimum variance of bu and bjk can be deduced, and the final prediction equation is as follows:

After the establishment of the mathematical model, the prediction accuracy determines the applicability of the model. Based on the multiple linear regression analysis model, the multiple correlation coefficient is used to predict the accuracy of the model, and the partial correlation coefficient is used to measure the contribution of each project in the prediction model.

- Multiple correlation coefficient

The multiple correlation coefficient is measured by the proportion of the regression square sum SR in the total square sum ST, which can be used to predict the accuracy, which is calculated according to Equation (10):

where is the arithmetic average of each reference variable; is the sum of the total deviation square of the data, which is used to reflect the volatility of the data variable ; and is the sum of squares of residuals, which is used to reflect the fluctuation of data caused by factors other than the linear relationship between y and . If , multiple observations can be accurately fitted by linear relations. The larger the Se is, the larger the deviation between the observations and the linear fitting is. is the sum of regression squares, the larger the Se is, the greater the proportion of volatility of described by linear regression, that is, the more significant the linear relationship between y and . The closer that the multiple correlation coefficient is to 1, the higher the prediction accuracy of the model is.

- 2.

- Partial correlation coefficient

Partial correlation coefficient is an index used to evaluate the degree of correlation between two categories in quantitative theory. It is the correlation coefficient between two of several influence variables under the condition of eliminating the influence of other variables. The specific calculation method is as follows: first make the correlation matrix R0.

where the represents the correlation coefficient between the project and the reference variable ; indicates the correlation coefficient between the project and . When , the .

Then find out the inverse matrix of , and the elements in marked as . Then the partial correlation coefficient r is calculated according to Equation (12):

3. Division and Analysis of Influencing Factors of Hole-Wall Collapse of Cast-in-Place Bored Piles in Guangdong Petrochemical Project

3.1. Overview of the Project

The 20-million-ton/year heavy oil processing project site of Guangdong Petrochemical Company is located in Dananhai Industrial Park, Longjiang Town, Huilai County, Jieyang City, Guangdong Province, on the eastern coast of Guangdong near the South China Sea. The terrain is high in the north and low in the south, and the site is about 24 km from the Huilai County seat. The project is located approximately 1.6 km inland from the west coast of Longjiang Town. Before site formation, the original topography was generally higher in the east and lower in the west. In the eastern part of the site, the terrain is slightly undulating, with a maximum elevation of 14.24 m and a minimum elevation of 10.46 m, giving a maximum relief of 3.78 m. Figure 1 shows the location of the study area, and Figure 2 shows the original topography and geomorphology of each area as well as the construction site.

Figure 1.

Location map of the study area.

Figure 2.

The topographic and geomorphic conditions of the research region.

The project is located at the mouth of the Longjiang river in Jieyang City, Guangdong Province, the strata in the area are mainly composed of the quaternary artificial fill layer (Q4ml), the quaternary holocene aeolian-water deposit layer (Q4eol+m), the marsh deposit layer (Q4h), the marine-land interactive deposit layer (Q4mc), the quaternary upper pleistocene marine-land interactive deposit layer (Q3mc), the alluvial-diluvial deposit layer (Q3al+pl), the relict layer (Q3el), and the Yan Mountains granite (52−3). Because of the particularity of the stratum and the special requirement of the project equipment, the pile foundation is used in all the important equipment and in the pipe gallery in the field area. There are about 2000 cast-in-place bored piles and 20,000 CFG piles in the one-to-four combined installation. The cost is about 150 million. However, due to the special geological conditions of the loose stratum and the underground water dynamic and other factors, in the construction of the cast-in-place bored pile there is often a relatively large deformation of the hole-wall, and sometimes it will become a serious hole-wall collapse problem.

3.2. Division of Factors Affecting Hole-Wall Collapse and Analysis of Collapse Mechanism

- (1)

- Natural factors affecting hole-wall stability

① Thickness ratio of sand layer.

The ratio of sand layer thickness to the total design drilling depth reflects the overall soil profile at each borehole. Different boreholes have different sand layer proportions along their depth, leading to different overall hole-wall stability. In the study area, sand layers thicker than 10 m are classified as “thick sand layers” and are unfavorable to hole-wall stability.

② Structure of strata.

Stratum structure refers to the combination of layers with different properties along the borehole depth. In the study area, typical stratigraphic structures include uniform sand layers, uniform clay layers, interbedded mucky clay or organic fine sand, and alternations of sand and clay layers. Sandy soils are generally more prone to collapse than clayey soils. Due to the restraining effect of clay layers on sand layers, alternating sand and clay tends to be more stable than single sand layers. Mucky clay layers are easily disturbed by mechanical actions, which accelerates their rheological behavior and significantly affects the stability of cast-in-place bored piles.

③ Property of stratum.

For sandy soil, the most important index that affects its physical and mechanical properties is the compactness of sand. According to the Chinese code for investigation of geotechnical engineering (GB-50021-2009) [25], the compactness of sand can be described according to the standard penetration test hammering number of sand. When N > 15, the sand is medium or dense, when N < 15, the sand is slightly dense or loose, and the loose or slightly dense sand layer is more likely to lead to unstable hole-walls and collapse holes. There are also flow-plastic, soft-plastic, silt-fine sand, and a large amount of undecomposed humus in this area, and the organic matter content is generally 10–30%. The soft interlayer such as peat clay or organic sand soil with low dry strength is a threat to the stability of hole-wall of cast-in-place bored piles.

④ Groundwater factor.

The soils beneath the cast-in-place bored piles are basically saturated. The casing depth is about 1.5 m, and groundwater depth varies between 0.5 m and 1.0 m. Thus, changes in groundwater level have little effect on soil unit weight. The major concern is the static water pressure exerted by groundwater on the hole-wall during construction. According to basic principles of hydrostatics, the higher the groundwater level, the greater the pressure on the hole-wall soil and, consequently, the greater the collapse-driving force. Therefore, shallower groundwater levels lead to more unstable hole-walls. Before constructing cast-in-place bored piles in water-rich foundations, dewatering measures should be taken to lower groundwater levels within the construction area; that is, increasing groundwater depth improves hole-wall stability.

- (2)

- Human factors affecting the stability of the hole-wall

① Stable liquid.

In the construction of cast-in-place bored piles, especially in the construction of soft soil foundation, the use of stable liquid wall protection is an important means to ensure the stability of the hole-wall. The radial liquid pressure is generated to the soil of the hole-wall pointing out of the borehole in the hole-wall, which supports the soil in the hole-wall to maintain the stability of the hole-wall. With the decrease in the specific gravity of the stabilizing liquid, the radial liquid pressure on the hole-wall decreases, that is, the supporting effect on the soil of the hole-wall decreases, which leads to a decrease in the stability of the hole-wall. In the process of cast-in-place bored pile construction, the balance of soil force can be maintained by adjusting the specific gravity of stabilizing liquid, so as to maintain the stability of hole-wall. In the construction of cast-in-place bored pile, the stratum encountered is mostly quaternary stratum, which is loose and easy to collapse. Increasing the specific gravity of the stabilizing liquid in the hole-wall during drilling is a technical measure to increase the stability of the hole-wall in the actual construction. However, the retaining wall of the stabilizing liquid will produce a layer of paste-like sheath in the foundation soil, what we usually call the mud skin. The increase in the specific gravity of the stabilizing liquid means that the content of the solid phase will increase, which will cause the mud skin attached to the hole-wall to be relatively thick; moreover, the mud crust is loose and low in toughness and will cause the hole-wall to collapse by hydration. In addition, the mud layer will exist permanently after the concrete pouring, which further changes the exertion of the soil side friction around the pile, so it is necessary to select and adjust the proportion of the stabilizing liquid reasonably within the scope of the code in the actual construction.

② Relative height of the liquid level in the hole.

The effect of the stable liquid on the stability of the hole-wall is often determined by the relative height of the stable liquid level and the buried depth of the underground water level, in addition to the performance index of the stable liquid. The head height difference between inside and outside of the hole-wall is the decisive mechanical factor for the stability of the hole-wall. In the study area, the relative height of stable liquid level is relatively small when the hole-wall is unstable. The constructors often increase the relative height of the stable liquid level according to the design depth of different strata and boreholes, so as to increase the static pressure on the hole-wall. In coastal areas, due to the high groundwater level, it is often necessary to stabilize the liquid level higher than the horizontal surface, so the increase in the relative height of the stable liquid level is generally achieved by burying protective tubes.

③ Stagnation time after hole formation.

The stagnation time after hole formation refers to the entire period from the start of drilling to completion of concrete pouring. As time passes after drilling, creep deformation of the formation toward the hole and the damage due to water absorption by soils near the hole-wall gradually become more significant. Environmental vibrations also accumulate, increasing the likelihood of hole-wall instability and failure. According to on-site construction records, drilling in the study area was sometimes suspended for relatively long periods or completion of concrete pouring was delayed after drilling. Such uncertain factors often result in hole-wall collapse or have strong negative impacts on stability.

④ Orifice overloading.

Orifice overloading generally can be divided into two categories, hole additional static load and additional dynamic load. The deposits and structures near the drilling site will produce additional static pressure on the rock and soil layer. The additional dynamic load refers to the additional dynamic load generated by the cross operation of other large machines, such as bulldozers and hoisting machines, during the drilling process, if there are sensitive strata, such as silty soil, silty sand and so on, under the external dynamic load, the soil will be in the state of fluid or accelerate its creep, and the stability of the hole-wall will be adversely affected.

⑤ Drilling depth.

The cast-in-place bored piles in the study area are end-bearing piles, the drilling depth must meet the requirements of the bearing capacity of the cast-in-place bored piles, and the stability of the hole-wall is obviously affected by the drilling depth under the same geological conditions. With the increase in the drilling depth, the unloading of the soil increases, and the redistribution stress of the soil on the hole-wall increases. And the deeper the hole is, the more the soil in the hole is brought out repeatedly and the more the cast-in-place bored pipe and the stable liquid movement in the hole cause more frequent disturbance to the soil around the hole, which is disadvantageous to the stability of the soil in the hole-wall.

4. Quantitative Theoretical Evaluation Model of Collapse Factors of Cast-in-Place Bored Piles in Guangdong

4.1. Selection of Items and Categories

- (1)

- Quantitative factors:

① The specific gravity of the stabilizing liquid x1, the unit is 1, which reflects the influence of the performance index of the stabilizing liquid on the stability of the hole-wall.

② The liquid level x2, the unit is m, which reflects the influence of the static water pressure produced by the height of the stabilizing liquid head on the stability of the hole-wall.

③ The depth of the borehole x3, the unit is m, which reflects the influence of the depth of the borehole on the stability of the hole-wall.

④ The depth of groundwater level x4, the unit is m, which reflects the influence of groundwater change on the stability of hole-wall.

⑤ The time of borehole formation x5, the unit is hours, which reflects the influence of formation creep property on the stability of hole-wall.

⑥ The ratio of sand layer thickness to hole depth x6, the unit is 1, which reflects the influence of sand layer thickness on hole-wall stability.

⑦ The average standard penetration test number of sand soil x7, the unit is 1, which reflects the influence of sand layer on the stability of hole-wall.

⑧ The average liquid index of clayey soil x8, the unit is 1, which reflects the influence of the state of clayey soil on the stability of hole-wall.

- (2)

- Qualitative factors:

① Drilling stratigraphic structure x91. Category 1: Drilling reveals that the sand layer is a single structure; Category 2: Other.

② Layers x92. Category 1: Soft silty layers; Category 2: None.

③ Orifice overload x93. Category 1: Static or dynamic overload; Category 2: None.

4.2. Field Test and Evaluation of Hole-Wall Collapse Rate of Cast-in-Place Bored Piles

- (1)

- Definition of the hole-wall collapse rate parameter.

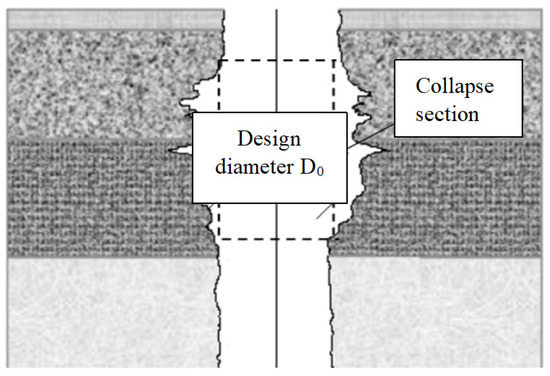

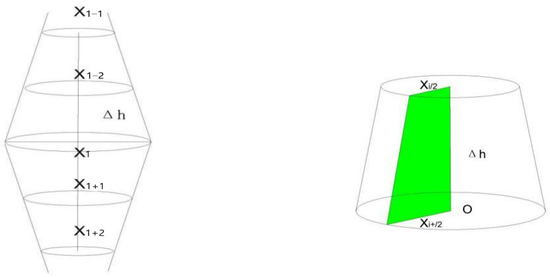

In order to describe and analyze quantitatively the stability degree of hole-wall or the degree of hole-wall collapse of cast-in-place bored piles, this paper explores and designs a hole-wall collapse parameter-hole-wall collapse rate, it is defined as the ratio of the collapse volume of the borehole section (Figure 3) to the design borehole volume corresponding to the collapse section.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of hole-wall collapse in the construction of the cast-in-place bored pile.

The equation for calculating the hole-wall collapse rate is as follows:

where —the collapse volume of the collapse section at drill hole ;

—the design diameter of the collapse section at drill hole corresponding to the drilling volume.

According to the definition of hole-wall collapse rate and its calculation equation (Equation (13)), it can be concluded that the parameter of the hole-wall collapse rate is the collapse volume of the hole-wall per unit depth. It is a non-dimensional evaluation parameter which can objectively reflect the stability degree and collapse strength of hole-wall in the cast-in-place bored pile construction and is generally applicable to the stability evaluation of the cast-in-place bored pile in the study area. Therefore, the parameter of hole-wall collapse rate can be used as the standard variable to quantitatively describe and evaluate the stability or degree of hole-wall collapse of cast-in-place bored pile, so as to further analyze and study the variation regulation and collapse mechanism of hole-wall stability in cast-in-place bored pile construction.

- (2)

- Field measurement and data analysis of hole-wall collapse rate parameters.

① Parameter detection of hole-wall collapse of cast-in-place bored pile in engineering area.

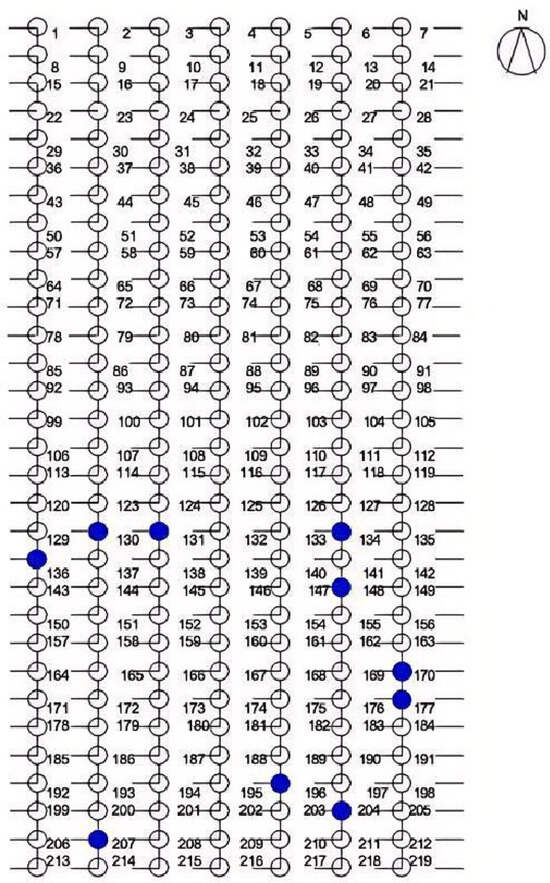

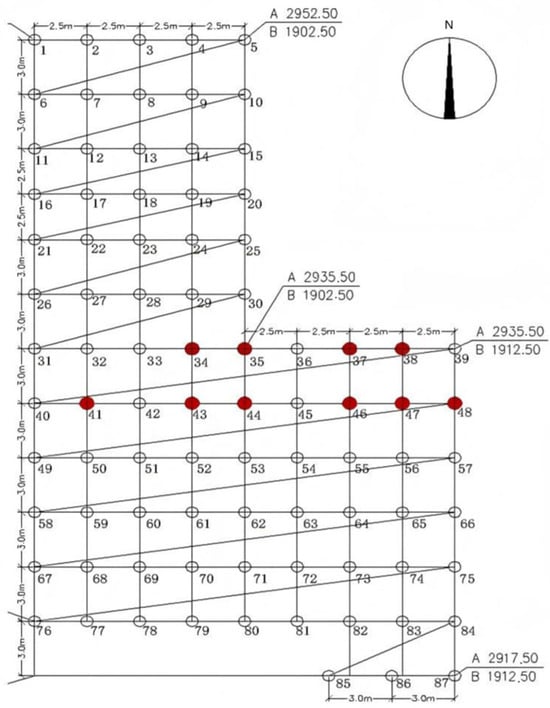

Because there are significant differences in drilling parameters and formation parameters between the two joint and the three joint areas of cast-in-place bored pile project, the data are sampled in the two joint and the three joint areas, respectively. It is beneficial to further study the influence regulation of the variation in different drilling parameters and stratum parameters on the stability of the hole-wall in the construction of cast-in-place bored pile and to accurately analyze and evaluate the influencing factors of the stability of the hole-wall in the construction of the cast-in-place bored pile. Therefore, the drilling parameters of the cast-in-place bored pile in the areas of the first bid section of the cast-in-place bored pile project in Guangdong are sampled and tested, respectively, and the distribution of detection boreholes in zone B and C are shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, respectively.

Figure 4.

The distribution of test drilling in zone B.

Figure 5.

The distribution of test drilling in zone C.

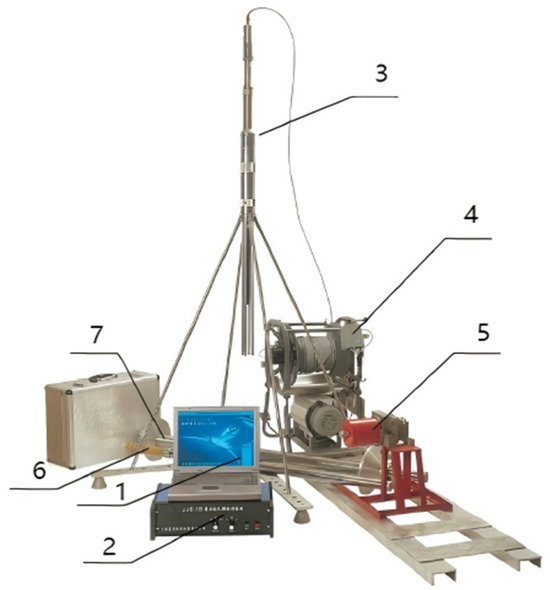

Given the highly concealed nature of borehole collapse in cast-in-place piles, it is generally impossible to directly observe or assess the process and outcome of wall collapse. Therefore, this study employs the JJC-1D borehole quality detection system (Figure 6), a specialized device for measuring the quality of cast-in-place pile boreholes, to conduct on-site systematic testing and data collection. The system was used to measure parameters related to borehole collapse, such as aperture, depth, verticality, and sediment thickness, in the construction boreholes of the second and third units of a cast-in-place pile project in Guangdong. The statistical parameters of the detected borehole collapse are presented in Table 1.

Figure 6.

The device appearance diagram of JJC-1D system. 1. Computer; 2. Ground controller; 3. Caliper tool; 4. Winch; 5. Wellhead sheave frame; 6. Sediment analyzer; 7. Centralizer.

Table 1.

Statistical data of the tested parameters of the drillings in the second and third joint zones.

② Determination of hole-wall collapse rate parameter of cast-in-place bored piles

The measured data of drill hole diameter is 25 mm apart along the drill hole depth. According to the measured data of drill hole diameter, the drill hole is divided into N round tables with thickness of 25 mm, as shown in Figure 7. The model can be used to calculate the volume of each layer, and the design diameter is a known parameter. Therefore, the collapse volume of the hole-wall in the collapse section can be further analyzed and the collapse rate can be calculated.

Figure 7.

The analysis and calculation model of borehole volume.

The equation for calculating the collapse volume of the layer hole-wall is as follows:

Total volume of hole-wall collapse from a single hole:

where —Thickness of stage , ;

—The bottom surface diameter on layer platform (mm);

—The bottom surface diameter under layer platform (mm);

D—The designed diameter for drilling (mm).

Based on the sampling test data of the hole diameter in the research area of the pored pile construction site in Guangdong Petrochemical Company, the hole-wall collapse rate of a single borehole is calculated according to the definition of the hole-wall collapse rate and the equation (Equation (11)). The statistical data of collapse rate in the study area are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The calculation result of the collapse rate of the tested hole.

4.3. Evaluation Model and Accuracy Analysis of Collapse Factors of Cast-in-Place Bored Piles

According to the basic principle of quantitative theory, the parameters of the hole-wall collapse rate are taken as the standard variables of collapse rate, the factors affecting the collapse and stability and the factors affecting the hole-wall collapse are as follows: the specific gravity of the stabilizing liquid, the situation of the soft stratum exposed by the borehole, the average number of standard penetration of the sand soil, the buried depth of the groundwater, the level of the liquid in the hole, the time of the hole forming, the depth of the borehole, the average liquid index of the cohesive soil, the structure of the borehole, the ratio of the thickness of the sand layer, the orifice overloading, and the factors affecting the hole-wall collapse. A quantitative theoretical evaluation model of collapse factors of cast-in-place bored piles was established by using the Matlab R2025a multi-element regression analysis program to assist calculation and modeling. The data are transferred into the Matlab program, the multiple linear regression coefficients are calculated, and then the quantitative theoretical evaluation model of the collapse factors of the hole-wall of the cast-in-place bored pile is determined as follows:

Using the Matlab computing platform, the accuracy of the prediction model is analyzed and the complex correlation coefficient R = 0.93, and the complex correlation coefficient is greater than 0.9, which shows that the prediction model is more accurate, and the linear correlation between the reference variable and each category is a high correlation.

At the same time, 11 factors, such as the depth of drilling hole and the time of drilling hole, are taken as explanatory variable x, and the response table of the stability impact factors and the reference variables, and the quantitative variables and categories is listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Reaction matrix table of the hole-wall collapse samples in Guangdong petrochemical engineering area.

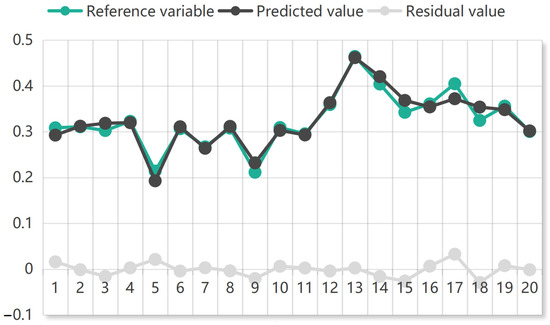

Using the quantitative theoretical evaluation model and prediction equation of hole-wall collapse factors of the cast-in-place bored pile established in this paper, each index is brought into the prediction evaluation model, the prediction values of each reference variable are calculated, and, according to the actual value and the forecast value difference, the residual values are calculated. The actual value, the forecast value, and the residual concrete value are shown in Table 4 and Figure 8.

Table 4.

The reference variable, predicted value, and residual value of the sample.

Figure 8.

Comparison chart of reference variable, predicted value, and residual value.

4.4. Quantitative Analysis and Evaluation of Factors Affecting Hole-Wall Collapse and Stability of Cast-in-Place Bored Pile

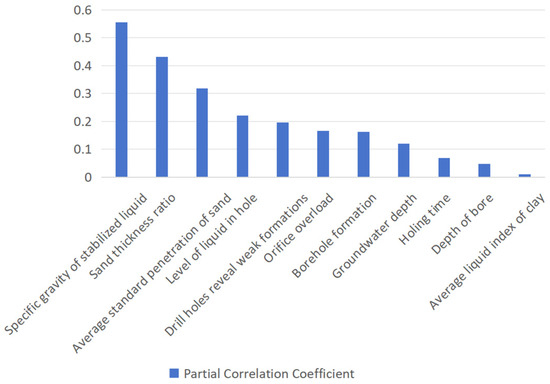

The stability and collapse of hole-wall of large-scale cast-in-place bored piles are the result of various factors, but the influence and control of each factor is different. According to the basic principle of the quantitative theory, the partial correlation coefficient between the model and the prediction equation is used to determine the influence of each factor on the stability of the hole-wall, the effect of factors affecting hole-wall collapse and stability of cast-in-place bored piles are quantitatively analyzed and evaluated, and on this basis, the stability of hole-wall and the optimal prevention measures are studied and determined.

According to the theory of quantification, the partial correlation coefficient is the same as the simple correlation coefficient, and there is a positive correlation between the absolute value and the degree of linear correlation between the variables. That is, the higher the linear correlation degree between variables, the higher the absolute value of correlation coefficient; the lower the linear correlation degree is, the smaller the absolute value of the correlation coefficient is. Therefore, according to the partial correlation coefficient between the hole-wall collapse rate of the cast-in-place bored pile and the influencing factors, we can reflect and evaluate the degree of influence of the influencing factors on the hole-wall stability of the cast-in-place bored pile. Then, we can distinguish the main factors and the secondary factors which affect the hole-wall collapse of the cast-in-place bored pile. To this end, the use of large-scale data statistical analysis software MATLAB platform for programming, the final calculation of the impact of the partial correlation coefficient, and the partial correlation coefficient are used to rank the contributions of each factor to the stability and collapse of the hole-wall (Table 5, Figure 9).

Table 5.

Comparison and analysis of weight and effect of each influence factor.

Figure 9.

The partial correlation coefficient of each influence factors.

The results of the quantitative analysis and evaluation of the effects of the aforementioned factors on hole-wall collapse and stability in cast-in-place bored piles indicate that the specific gravity of the stabilizing fluid has the greatest influence among all contributing factors. This is followed, in descending order of influence, by the ratio of sand layer thickness to hole depth, the relative density of sandy soil, the stabilizing fluid level in the hole, the exposure of soft strata during drilling, the degree of orifice overloading, the hole structure, and the average liquidity index of cohesive soil. According to the evaluation outcomes, the impact of stabilizing fluid density on the hole-wall stability of cast-in-place bored piles is particularly pronounced, and increasing the stabilizing fluid density can significantly enhance hole-wall stability. The ratio of sand layer thickness to hole depth, the relative density of sand, and the distribution of underlying soft strata also exert substantial influence. In the study area, the effects of sand layer thickness and soft strata on hole-wall stability are especially considerable. As indicated in the detailed geotechnical investigation report for the 20-million-ton/year heavy oil processing plant and wharf reservoir area of Guangdong Petrochemical Company, weak strata are locally present and concentrated in the second joint layer, which is the primary reason for frequent localized hole-wall collapse during construction of the second joint. The aim of quantitatively analyzing and evaluating the factors affecting hole-wall stability in cast-in-place bored piles is to establish a basis for determining stability and optimizing collapse prevention and control measures. Therefore, during construction and drilling, greater emphasis should be placed on controllable engineering parameters, and appropriate corresponding measures should be implemented.

Based on the above results, it can be seen that among the artificially controllable factors, the major contributors to hole-wall stability are stabilizing fluid density, pore-forming time, stabilizing fluid level in the hole, orifice overloading, and groundwater level. For cast-in-place bored pile construction in this area, the following measures are recommended: (1) during construction, conduct real-time monitoring of formation changes exposed during drilling (particularly sand layer thickness, the presence of weak interlayers, and sand density). Adjust the stabilizing fluid density promptly based on monitoring data. For example, before entering thick sand layers, loose sand layers, or weak formations, the stabilizing fluid density should be significantly increased in advance (e.g., to 1.25–1.35 or higher, with specific values determined by formation testing) to ensure sufficient liquid column pressure and wall-supporting capacity for collapse prevention. Simultaneously, strictly monitor key performance indicators of the stabilizing fluid—such as viscosity and sand content—to ensure effective wall protection, and to maintain adequate reserves of high-quality bentonite and additives for timely density adjustments. Density adjustments should be guided by on-site slurry testing and geological feedback, with mandatory inspection and adjustment at specified depths (e.g., every 2–5 m) or when significant formation changes occur. (2) Optimize construction organization to ensure seamless coordination among drilling, hole cleaning, steel cage installation, and concrete pouring, thereby minimizing exposure time after borehole formation. Prepare detailed operational schedules for individual piles and enforce strict adherence, specifying maximum allowable durations from drilling commencement to initial concrete placement (e.g., 4–8 h depending on depth and geological complexity). In the event of equipment malfunction or abnormal geological conditions requiring interruption, risks should be assessed immediately, and drilling tools should be raised to a safe position or withdrawn from the hole. (3) Enhance in-hole liquid level monitoring and groundwater/precipitation management. Continuous monitoring of stabilizing fluid levels must be implemented (using automatic alarm systems or designated personnel), ensuring that the liquid level remains consistently 1.5–2.0 m above the groundwater level or confining head, and at least 0.5 m below the top of the casing. Special consideration should be given to rainfall effects: avoid critical drilling operations during moderate to heavy rainfall. If drilling must proceed under such conditions, install robust rain shelters covering the entire pile location and slurry circulation system, and reinforce drainage facilities (open ditches, collection wells, pumps) to ensure rapid removal of surface water. (4) Implement scientific site layout and strict load control. Heavy construction machinery (e.g., cranes, excavators, concrete mixer trucks, earthmoving vehicles) must not pass, park, or operate intensively near active drilling areas (safe distance ≥ twice the pile diameter and not less than 5 m). Plan clear access routes and material storage zones to keep heavy equipment movement away from drilling sites and establish visible isolation barriers around boreholes. When adjacent operations are unavoidable, assess the potential effects of additional loads (static, dynamic, and vibrational) on borehole stability. If necessary, employ mitigation measures such as distributing loads with steel plates, controlling vehicle speed, and preventing sudden stops. Optimize the construction sequence to avoid activities that may induce substantial stress or vibration near boreholes in sensitive formations (thick sand layers, weak layers), such as deep foundation pit excavation, dynamic compaction, or large-equipment foundation construction.

5. Conclusions

From the above analysis and research, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- (1)

- Based on the characteristics and distribution patterns of hole-wall collapse in cast-in-place bored pile foundations in the typical coastal area of Guangdong Petrochemical Company, hole-wall deformation and collapse behavior were systematically monitored and measured using the JJC-1D pore diameter detection system. The hole-wall collapse rate was proposed and defined as an evaluation parameter for hole-wall stability and collapse in cast-in-place bored piles. The interactions among qualitative and quantitative collapse-inducing factors and hole-wall stability were comprehensively analyzed and evaluated.

- (2)

- Based on quantitative and qualitative analyses of factors, including stabilizing fluid properties, fluid level, orifice overloading, groundwater conditions, and hole formation time, the principles of Quantification Theory I were applied to evaluate the effects of all these factors on borehole collapse. A correlation evaluation model for qualitative and quantitative collapse factors, as well as a quantitative theoretical evaluation model of borehole wall collapse factors, was established. These results provide a sound analytical basis for quantitatively evaluating the factors and mechanisms governing pile wall collapse in the project area.

- (3)

- The quantitative evaluation model was used to analyze and assess the main factors contributing to pile wall collapse in the project area. The results show that the specific gravity of the stabilizing fluid contributes the most among all influencing factors. This is followed, in descending order, by the ratio of sand layer thickness to hole depth, relative density of sandy soil, fluid level in the hole, presence of weak layers, orifice overloading, borehole structure, and the average liquid index of cohesive soil. The study provides a theoretical foundation for developing optimized prevention and control measures against borehole collapse during cast-in-place bored pile construction in this region.

6. Limitations and Future Prospects

(1) The monitoring dataset used in this study includes only 20 boreholes, and additional engineering cases and monitoring data are needed in future research to supplement and validate the results. Moreover, the generalizability of the model to other sites has not yet been evaluated due to the absence of cross-validation or external test datasets. This issue will be the focus of future work.

(2) This study focuses on weak cohesive soil layers. By comparing research from domestic and international scholars on stability factors affecting bored cast in situ piles in various regional strata [26,27,28], it is found that the specific gravity of the stabilizing fluid is the primary factor influencing borehole wall stability under most stratum conditions. Future research could establish a quantitative relationship model integrating laboratory tests and field monitoring, considering soil physical-mechanical properties (e.g., liquid-plastic limit, cohesion, internal friction angle) with specific gravity of the stabilizing fluid. This approach would clarify the optimal density range corresponding to different burial depths and soil layers.

(3) In future research, modern methods such as neural networks and artificial intelligence will be considered for detection and stability evaluation of cast-in-place bored piles, with the aim of further improving prediction accuracy and robustness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G.; Methodology, L.G.; Validation, H.Y.; Formal analysis, K.H.; Investigation, L.G.; Resources, J.Z.; Data curation, L.G. and K.H.; Writing—review & editing, K.H.; Project administration, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the Youth Project of Suqian Science and Technology Plan (K202418), the Youth Project of the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20241099), the Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (23KJB410002), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42577210), Jiangsu Provincial Young Science and Technology Talent Support Program (JSTJ-2025-1001) and the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions’ Qinglan Project Training Program.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bradley, W.B. Mathematical concept Stress cloud can Predict borehole failure. Oil Gas J. 1979, 79, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.H.; Liu, J.; Zhu, W.; Tang, C.; Yang, T. Simulation of Borehole Failure with Impact of Mud Permeation at Multilateral Junction. In Proceedings of the SPE Asia Pacific Oil and Gas Conference and Exhibition, Perth, Australia, 20 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Am, A.A.; Zimmerman, R.W. Stability analysis of vertical boreholes using the Mogi–Coulomb failure criterion. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2006, 43, 1200–1211. [Google Scholar]

- Gnirk, P.F. The mechanical behavior of unease wellbore situated in elastic/plastic media under hydrostatic stress. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 1972, 24, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roegiers, J.C. Well Modeling: An overview. Oil Gas Sci. Technol. 2002, 57, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.M.; Li, Z.D. Hole forming mechanics analysis of the bored filling pile on the bridges in alluviation overburden area. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. (Transp. Sci. Eng.) 2007, 31, 734–737. [Google Scholar]

- Papamichos, E. Analysis of borehole failure modes and pore pressure effects. Comput. Geotechnics 2010, 37, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.G.; Zhang, G. Analysis of stability of bored pile hole-wall. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. S 2011, 1, 3281–3287. [Google Scholar]

- Alkroosh, I.S.; Bahadori, M.; Nikraz, H.; Bahadori, A. Regressive approach for predicting bearing capacity of bored piles from cone penetration test data. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2015, 7, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Wen, Z.; Ming, F.; Liu, J.K.; Zhang, M.L.; Wei, Y.J. Applicability evaluation of cast-in-place bored pile in permafrost regions based on a temperature-tracking concrete hydration model. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 149, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Song, J.U.; Hong, W.T.; Yu, J.D. Application of time domain reflectometer for detecting necking defects in bored piles. Ndt E Int. 2018, 100, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Wang, K.Y.; Chen, L. Influence of Benoto bored pile construction on nearby existing tunnel: A case study. Soils Found 2019, 59, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.Q.; Wang, Z.Q.; Liu, B.L.; Lv, J.G. Borehole stability analysis: A new model considering the effects of anisotropic permeability in bedding formation based on poroelastic theory. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2019, 69, 102932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Wen, Z.; Brouchkov, A.; Zhang, M.L.; Feng, W.J.; Zhirkov, A. Effect of a ventilated open structure on the stability of bored piles in permafrost regions of the Tibetan Plateau. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2020, 178, 103116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Kang, W.H.; Oh, J.; Canbulat, I.; Hebblewhite, B. Numerical simulation on borehole breakout and borehole size effect using discrete element method. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2020, 30, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.C.; Yang, W.J. Study on bearing behavior of super-long bored pile in sand area. J. China Foreign Highw. 2020, 40, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, L.L. Auxiliary Grouting Technology for Anti-collapse Hole of Pre-stressed Anchor Cable Construction in Water-rich Sand Stratum. Subgrade Eng. 2022, 5, 172–176. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.C.; Xu, H.H.; Wang, B.L.; Zhou, J.P.; Liu, H.C. Accurate detection technology of super long bored cast-in-place pile concrete pouring thickness based on ultrasonic inclined plane reflection measurement. Measurement 2022, 198, 111314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, X.L.; Shang, B.M.; Yu, Y.L.; Zhao, J.J.; Wang, H.; Jin, Y.T. Research on borehole wall stability and construction process optimization of non-homogeneous sand layer bored piles. Munic. Eng. Technol. 2023, 41, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.D. Research Progress on Factors Influencing the Stability of Borehole Walls in Drilled Piles. Heilongjiang Sci. 2024, 15, 136–139+142. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.C.; Liu, H.C. Defect detection method of underwater bored cast--in--place pile based on optical image in borehole. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2024, 14, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.J. Analysis and treatment measures of hole collapse of bored cast—in—place pile on super large bridge. Saf. Qual. 2024, 3, 223–225. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.W. Study on the sensitive factors of collapse of caisson wall in mega bridge based on grey correlation—Taking a bridge on Yangtze River as an example. Sichuan Archit. 2025, 45, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.J.; Gong, L.F.; Huang, R.Q. Application of quantification theory to engineering geology. J. Eng. Geol. 2014, 19, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar]

- GB 50021-2009; Code for Investigation of Geotechnical Engineering. Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Xun, B.; Liu, C.J.; Yang, X.C.; Meng, F.C. Study on high pressure rotary grouting assisted hole forming technology for pile foundation in deep pebble layer. Build. Struct. 2022, 52, 2933–2936. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, G.J.; Wang, J.H.; Chen, J.J. Stability analysis and support suggestions of pile hole based on mud pressure balance earth pressure. J. Shanghaijiaotong Univ. 2021, 55, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Li, J.P.; Yue, Z.W.; Tang, J.H. Mechanical mechanism of hole-wall stability of bored pile in saturated clay. Rock Soil Mech. 2016, 37, 2496–2504. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).