Model Test Study on the Mechanical Characteristics of Boltless Hexagonal Segments in TBM Tunnels

Abstract

1. Introduction

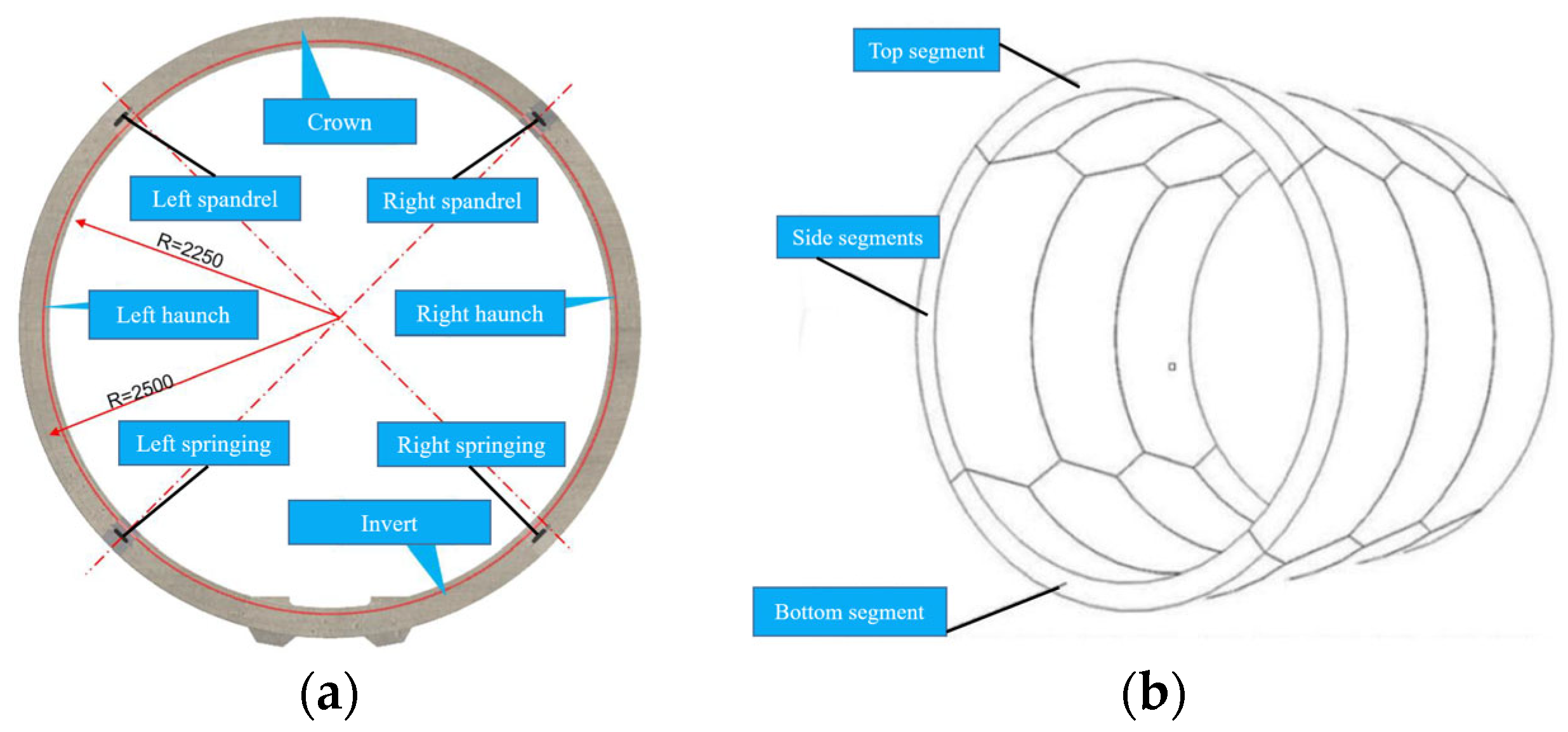

2. Similarity Model Test

2.1. Test Principle

2.2. Similarity Constants

2.3. Similarity Material Proportion Test

2.4. Establishment of the Similarity Model Test System

2.5. Measurement Points and Loading Conditions

3. Analysis of Test Results

3.1. Stress Characteristics of Hexagonal Segments at Different Burial Depths

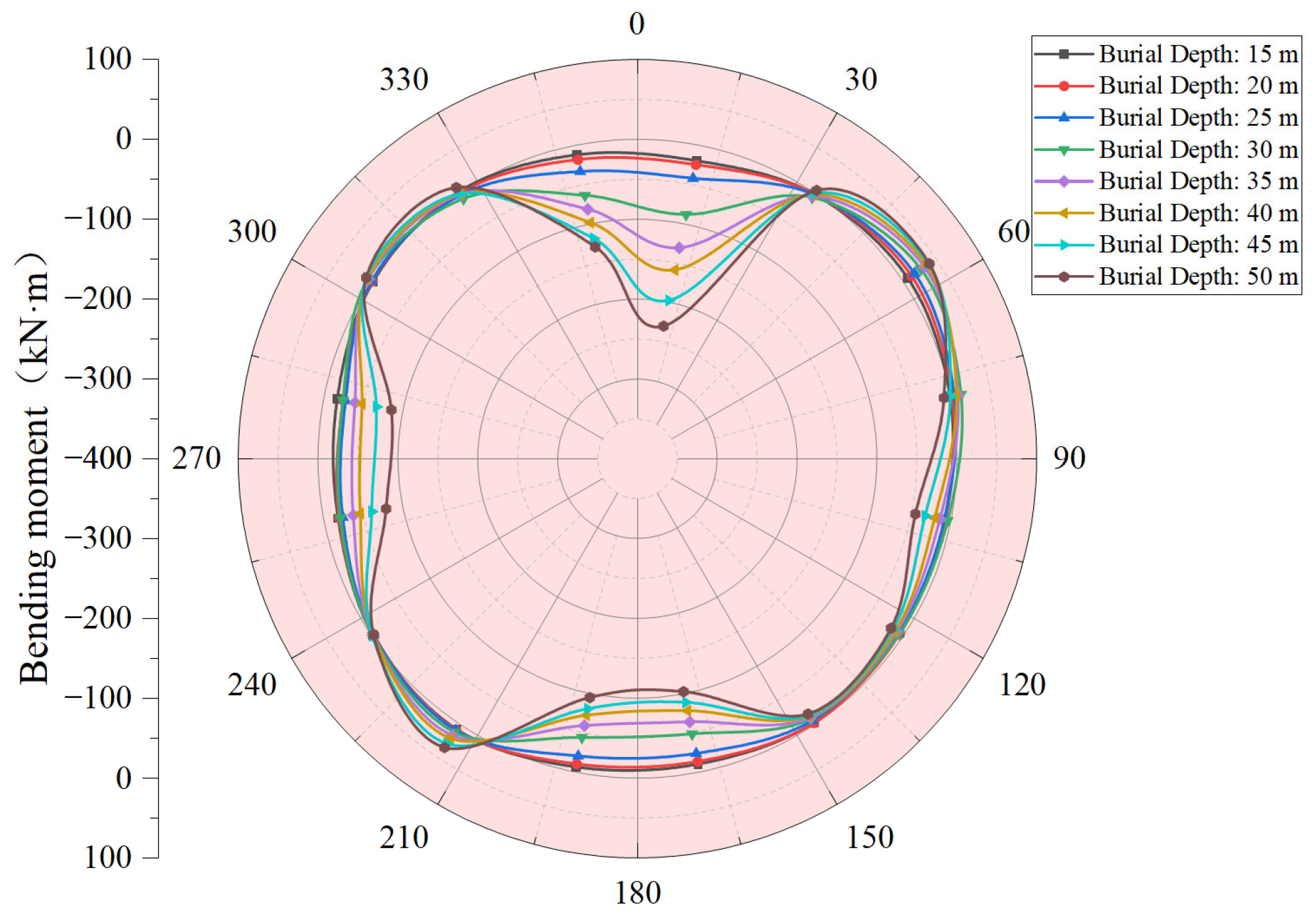

3.1.1. Variation in Bending Moment

3.1.2. Variation in Axial Force

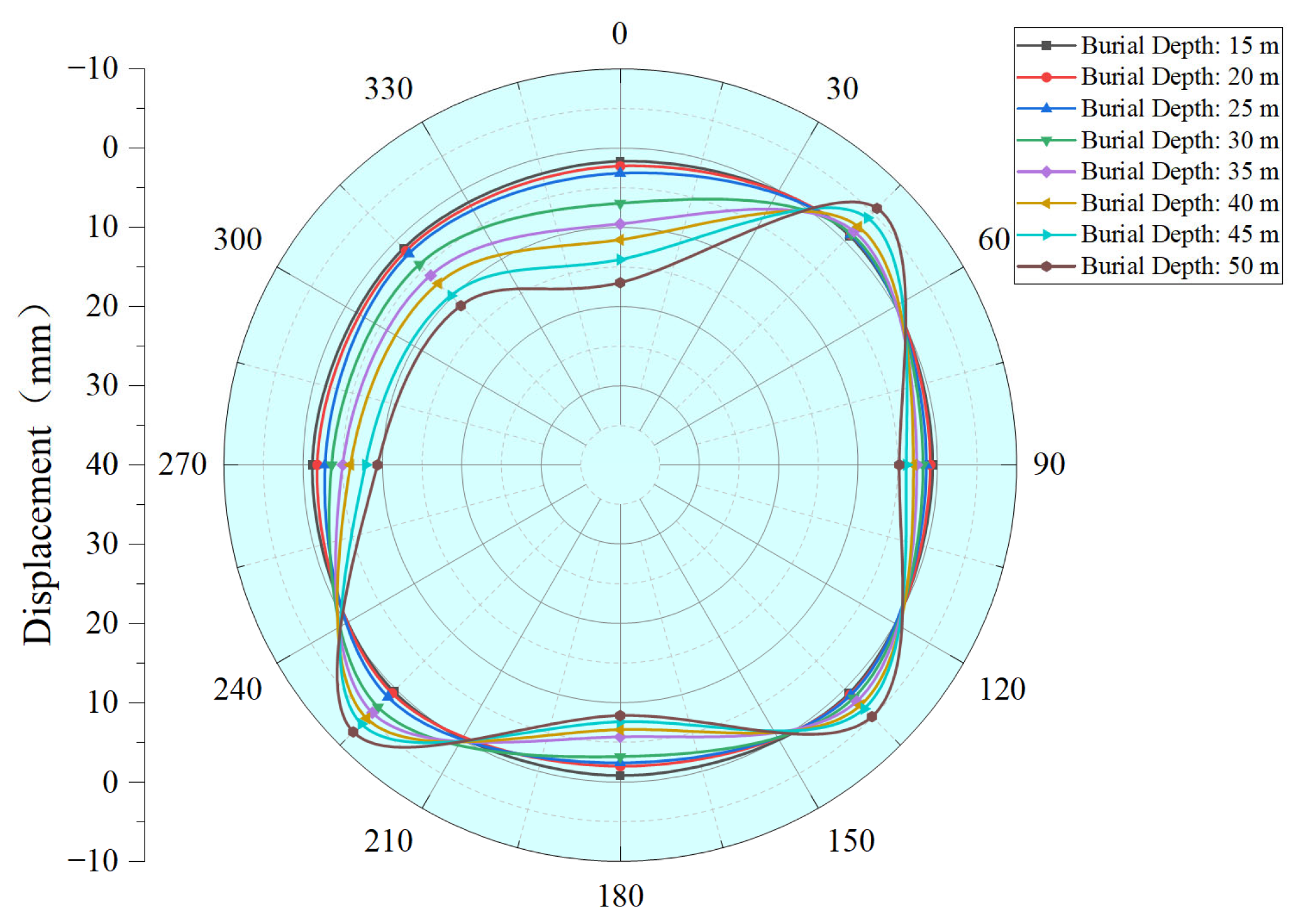

3.1.3. Variation in Displacement

3.2. Stress Characteristics of Hexagonal Segments at Different Lateral Pressure Coefficients

3.2.1. Variation in Bending Moment

3.2.2. Variation in Axial Force

3.2.3. Variation in Displacement

3.3. Failure Characteristics of Hexagonal Segments

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Q.; Liu, S.; Lv, Y.; Ji, D.; Li, P. Modification of Segment Structure Calculation Theory and Development and Application of Integrated Software for a Shield Tunnel. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Wen, Z.; You, G.; Wang, S.; Liu, W. Study on the Calculation of the Surrounding Rock Stress on Shield Tunnels in Rock Strata. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2023, 41, 4383–4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Miao, S.; Wang, H.; Yang, P.; Xia, D. A prediction model for surface settlement during the construction of variable cross-section tunnels under existing structures based on stochastic medium theory. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 155, 106177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, J. Experimental Research on the Floating Amount of Shield Tunnel Based on the Innovative Cumulative Floating Amount Calculation Method. Buildings 2024, 14, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dai, F.; Ding, B.; Zhong, M.; Zhang, H. Study on the effect of excavation sequence of three-hole shield tunnel on surface settlement and segment deformation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-Z.; Dai, X.-Y.; Sun, K.; Ai, G.-P.; Lei, T. Calculation method of longitudinal deformation of metro shield tunnel overpassing existing line at short distance. Rock Soil Mech. 2022, 43, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, H.; Xie, D.; Sun, J.; Shi, X. Mining Hazards to the Safety of Segment Lining for Tunnel Boring Machine Inclined Tunnels. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 9, 814672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Zhang, D.; Huang, H.; Thewes, M.; Liu, X. Surrogate numerical prediction method of TBM position via FEM simulation and machine learning. In Proceedings of the 5th GeoShanghai International Conference, Shanghai, China, 26–29 May 2024; Tongji University, College of Civil Engineering: Shanghai, China. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Hu, H.; Huang, X.; Luo, H.; Si, G.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, J. Response characteristics of surrounding rock and segment structure of large longitudinal slope tunnel. Electron. J. Struct. Eng. 2024, 24, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Yan, B.; Ding, B. Dynamic response of single pile induced by the vibration of tunnel boring machine in hard rock strata. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, P.; Li, Y.; Tang, X.; Lu, S.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, Z. Influence of double-line large-slope shield tunneling on settlement of ground surface and mechanical properties of surrounding rock and segment. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 63, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Shen, J.; Chen, X.; Dang, P.; Cui, H. Mechanical behaviours of concrete segmented tunnel considering the effects of grouting voids—A 3D numerical simulation. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, P.; Li, Y.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, S. Influence of Small Radius Curve Shield Tunneling on Settlement of Ground Surface and Mechanical Properties of Surrounding Rock and Segment. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, R.; Li, Y.; He, C.; Zhu, D.; Li, Y.; Yao, C.; Liu, Y.; Xu, P.; Zhao, Z. Study on Deformation Characteristics of the Segment in the Underwater Shield Tunnel with Varying Earth Pressure. Buildings 2024, 14, 2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.-G.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, H.-H.; Lu, Y. A multilayer thermo-elastic damage model for the bending deflection of the tunnel lining segment exposed to high temperatures. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 95, 103142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Ye, F.; Han, X.; Wang, P.; Chen, Z.; Liang, X. Displacement and pressure of surrounding rock during shield tunnelling and supporting in low water content loess. Eng. Geol. 2024, 338, 107612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jin, X.; Sun, G.; He, J. A Study on Seismic Dynamic Response of Pile-Supported Tunnels in Deep Backfill Area of Soil-Rock Mixture Based on a Model Test. Buildings 2024, 14, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, B.; Hofsterter, G.; Lehar, H. Application of a constitutive model for concrete to the analysis of a precast segmental tunnel lining. In Proceedings of the EURO-C 2003 Conference, St Johann Im Pongau, Austria, 17–20 March 2003; pp. 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koneshwaran, S.; Thambiratnam, D.P.; Gallage, C. Response of segmented bored transit tunnels to surface blast. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2015, 89, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, K.; Subramanian, S.N.S.; Sekar, A.; Ravichandran, P.T. Energy consumption analysis of different geometries of precast tunnel lining segment numerically. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 46475–46488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, K.; He, C.; Zhou, J.; Su, Z. A Loading Test Method of Prototype Structure for Nanjing Changjiang Tunnel. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Civil Engineering, Architecture and Building Materials (CEABM 2011), Haikou, China, 18–20 June 2011; p. 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; He, X.; Peng, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Song, Z. Influence of secondary lining thickness on mechanical behaviours of double-layer lining in large-diameter shield tunnels. Undergr. Space 2024, 18, 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, B.; Fu, Y.; Jian, Y.; Lu, X. Critical state analysis of instability of shield tunnel segment lining. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 96, 103180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, S.; Guo, W.; Chen, F.; Zhang, J.; He, C. Investigation of the Deformation Characteristics and Bearing Capacity of a Segment Structure of a Shield Tunnel with Cracks. Ksce J. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Yao, C. The progressive failure features of shield tunnel lining with large section. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 164, 108687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, Y.; Yuan, Y. Simulation Method of Scale Reduction Tests for Shield Tunnel Segment Joints. Tunn. Constr. 2022, 42, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Physical Quantity | Symbol | Unit | Similarity Relationship | Similarity Constant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| length | l | m | basic quantity | Cl = 10 |

| bulk density | γ | N/m3 | basic quantity | Cγ = 1 |

| strain | ε | - | Cε | Cε = 1 |

| stress | σ | N/m2 | CγCl | Cσ = 10 |

| force | F | N | CγCl3 | CF = 103 |

| bending moment | M | N∙m | CγCl4 | CM = 104 |

| elastic modulus | E | MPa | CγCl | CE = 10 |

| tensile stiffness | EA | N | CγCl3 | CEA = 103 |

| flexural stiffness | EI | N∙m2 | CγCl5 | CEI = 105 |

| Group Number | Water: Gypsum: Diatomite | Specimen Number | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Mean Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Converted Cube Compressive Strength (MPa) | Mean Compressive Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1:1.4:0.2 | 1-1 | 3.11 | 3.18 | 4.21 | 4.37 |

| 1-2 | 3.19 | 4.47 | ||||

| 1-3 | 3.25 | 4.43 | ||||

| 2 | 1:1.4:0.25 | 2-1 | 3.42 | 3.50 | 4.96 | 5.05 |

| 2-2 | 3.55 | 5.24 | ||||

| 2-3 | 3.53 | 4.94 | ||||

| 3 | 1:1.4:0.3 | 3-1 | 3.44 | 3.55 | 5.49 | 5.50 |

| 3-2 | 3.59 | 5.55 | ||||

| 3-3 | 3.62 | 5.46 | ||||

| 4 | 1:1.4:0.35 | 4-1 | 3.58 | 3.61 | 6.44 | 6.51 |

| 4-2 | 3.66 | 6.73 | ||||

| 4-3 | 3.58 | 6.38 | ||||

| 5 | 1:1.4:0.4 | 5-1 | 3.73 | 3.74 | 7.48 | 7.31 |

| 5-2 | 3.69 | 7.18 | ||||

| 5-3 | 3.79 | 7.26 |

| Condition Number | Burial Depth (m) | Water Head Height (m) | Lateral Pressure Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| A-1 | 15 | 15 | 0.5 |

| A-2 | 20 | 15 | 0.5 |

| A-3 | 25 | 15 | 0.5 |

| A-4 | 30 | 15 | 0.5 |

| A-5 | 35 | 15 | 0.5 |

| A-6 | 40 | 15 | 0.5 |

| A-7 | 45 | 15 | 0.5 |

| A-8 | 50 | 15 | 0.5 |

| B-1 | 30 | 15 | 0.35 |

| B-2 | 30 | 15 | 0.4 |

| B-3 | 30 | 15 | 0.45 |

| B-4 | 30 | 15 | 0.5 |

| B-5 | 30 | 15 | 0.55 |

| B-6 | 30 | 15 | 0.6 |

| B-7 | 30 | 15 | 0.65 |

| B-8 | 30 | 15 | 0.7 |

| Prototype Value | Model Value | Converted Prototype Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cube Compressive Strength (MPa) | 50 | 5.05 | 50.5 |

| Elastic Modulus (GPa) | 34.5 | 3.50 | 35.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Jin, X.; Li, Z.; Zheng, S.; Yao, F. Model Test Study on the Mechanical Characteristics of Boltless Hexagonal Segments in TBM Tunnels. Buildings 2025, 15, 4482. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244482

Wang X, Jin X, Li Z, Zheng S, Yao F. Model Test Study on the Mechanical Characteristics of Boltless Hexagonal Segments in TBM Tunnels. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4482. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244482

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xinyu, Xiaoguang Jin, Zhuang Li, Sanlang Zheng, and Fan Yao. 2025. "Model Test Study on the Mechanical Characteristics of Boltless Hexagonal Segments in TBM Tunnels" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4482. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244482

APA StyleWang, X., Jin, X., Li, Z., Zheng, S., & Yao, F. (2025). Model Test Study on the Mechanical Characteristics of Boltless Hexagonal Segments in TBM Tunnels. Buildings, 15(24), 4482. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244482