Abstract

This study investigates the interfaces of ultra-high-performance fibre-reinforced concrete (UHPFRC). The interfaces of UHPFRC-to-UHPFRC were studied using two techniques: (i) slant shear test and (ii) shear key test. Moreover, the glass fibre-reinforced polymer (GFRP) rebars were also used in the shear plane to optimise durability. Six UHPFRC push-off specimens with different GFRP reinforcement ratios and changing shear plane angles were investigated and compared to existing models and codes. The results showed that the slant shear and shear test performed better without adding the epoxy agents due to the presence of steel fibres, which provided the excellent benefit of bridging the cracks and increasing the friction resistance. Furthermore, the shear strength increased substantially with inclined shear planes, rising from 607 kN in the vertical case to 1837 kN at a 60° inclination. However, the existing equations for predicting the shear strength overpredict the shear strength with a vertical shear plane and underpredict the shear strength of the angled shear plane. The test results also confirm that steel fibres enhance shear transfer through crack bridging, while epoxy weakens the interface by limiting mechanical interlock. The linear elastic behaviour of GFRP rebars also influences the shear transfer mechanism by contributing dowel action without yielding.

Keywords:

shear-friction; concrete interfaces; bond strength; push-off test; shear strength; UHPC; FRP 1. Introduction

Ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPFRC) is a cement-based material and it possesses outstanding mechanical, ductile, and durability characteristics [1,2]. It has excellent features associated with strain-hardening behaviour provided by the steel fibres in the post-cracking phase. Mainly, UHPFRC is utilised in the elements of bridges, such as in precast deck panels and joint connections. UHPFRC can stand alone as a sole material or as an overlay material with another type of concrete, such as in repairing the bridge’s elements [3]. Moreover, UHPFRC accelerates bridge construction as it can achieve very high strength in a short period [4].

One of the major applications of UHPFRC is to repair damage. UHPFRC is widely used for bridge deck overlays and repairing girder ends. Ensuring a longitudinal shear transfer across concrete interfaces is critical for successful composite behaviour between old and new concrete interfaces. This mechanism is explained by means of shear-friction theory (SFT) for shear prediction across the shear plane. Most of the specifications in various codes and practices are based on this theory [5,6,7]. Zilch and Reinecke [8] explained that the shear transfer across interfaces occurs mostly due to (a) cohesion, which includes the adhesion of bond materials and mechanical interlocking of aggregate, and (b) the dowel action across the interfaces provided by the reinforcement.

Based on SFT, cohesion is affected by many factors, including the smoothness and roughness of the substrate surface, curing conditions, use of additional bonding due to the application of adhesive materials, mechanical properties of the concrete, and the age of the concrete [9]. However, Momayes et al. [10] found that the roughness of the substrate surface has a significant effect on bond strength under compression. Furthermore, He et al. [11] stated that the adhesion’s effectiveness depends on the agent’s material. In addition, Tayeh et al. [12] found that the UHPFRC overlay provides greater bond strength when the original normal strength concrete (NSC) layer is sand-blasted.

However, the applied shear load after cracking the shear plane is carried by the effect of the dowel action of the shear reinforcement. The truss-like action could be prevented by cracking the specimens before applying the shear load, allowing for a complete transfer of shear strength to the reinforcement [13]. Birkeland and Birkeland [13] produced the first equation for predicting the shear transfer capacity:

where is the ultimate shear strength, is the reinforcement ratio, is the yield strength of reinforcement crossing the cracks, and α is the coefficient of friction.

Subsequently, Equation (1) was modified by other investigators by incorporating the normal stress according to [14,15]. Hermansen and Cowan [16] proposed a modified theory that included the shear transfer occurring in the uncracked shear plane by testing uncracked specimens and they proposed the following equation:

However, to incorporate the effect of cohesion, the influence of compressive strength has been extensively investigated [15,16,17,18,19]. The first researcher who included compressive strength in assessing shear transfer was Loov [20]. The proposed equation has been modified by adding a factor for uncracked interfaces as well:

where k = 0.5, and is the compressive strength of concrete.

Mau and Hsu [21] commented on Walraven et al.’s [15] paper. The results were used to fit the data into a curve. Accordingly, the curve was evaluated, and then an equation was proposed. They changed the value of the parameter k in Equation (3) to 0.66. Additionally, the suggestion has been made to use this equation for uncracked and cracked interfaces. They also stated that the reinforcement index () is a vital parameter in this equation. Furthermore, the equation value should not exceed the steel yield point, and the excess shear stress could be neglected due to the excessive reinforcement. The proposed expression is as follows:

Further improvements to the above-outlined empirical equations were proposed by other researchers, such as Mansur et al. [19], in whose work the range of the compressive strength was increased up to 100 MPa. The following equation for estimating the shear transfer in high-strength concrete up to 100 MPa without fibre was proposed:

In another variation, Nanni et al. [22] developed the following analytical model to estimate the shear transfer strength. Based on extensive experimental data from previous research and the experimental programme, the proposed equation successfully predicted the shear strength of push-off specimens of earlier studies with uniform scattering. It depends on the clamping action provided by the transverse reinforcement. The expression proposed is as follows:

It is worth noting that Equations (1)–(6) were developed for concrete with conventional steel reinforcement, and their applicability can change when using fibre-reinforced polymer (FRP) bars. Recent studies have shown that the behaviour of FRP-reinforced UHPC and UHPFRC differs significantly from normal strength concrete, particularly in terms of confinement response, crack development, and stress–strain behaviour [23,24]. These findings highlight the need to examine the bond characteristics of concrete–FRP interfaces. Glass fibre-reinforced polymer (GFRP) bars are increasingly used for their corrosion resistance, but their brittle behaviour and lower elastic modulus compared to steel directly affect the bond strength.

Recent studies have also highlighted the importance of understanding the bond behaviour of GFRP in different environmental and loading conditions. Work on sea sand concrete has shown that immersion, temperature, and fatigue loading can significantly influence the static and cyclic bond performance of GFRP bars [25]. In addition, research on glass fibre-reinforced composites exposed to alkaline environments has demonstrated how fibre resin interaction, defect propagation, and durability can affect anchorage performance and long-term mechanical behaviour [26]. These findings further reinforce the need to investigate the bond behaviour of UHPFRC with GFRP reinforcement to ensure reliable performance under different interface conditions.

Therefore, this study investigates the bond behaviour of UHPFRC to UHPFRC and UHPFRC to FRP interfaces through slant shear tests, shear key tests, and push-off tests. The work examines UHPFRC interfaces both with and without adhesion material to understand the role of fibre bridging in shear transfer. In addition, push-off specimens reinforced with GFRP bars are tested to assess the bond behaviour of UHPFRC with FRP reinforcement while varying the shear reinforcement ratio and the angle of the shear plane. This combined experimental programme provides a new understanding of how interface conditions and GFRP reinforcement influence shear transfer in UHPFRC systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Mix Ratio

This study used a unified mix design of UHPFRC, which was developed at the University of Adelaide by Sobuz et al. [27]. The materials used in this mix are sulphate-resisting cement, locally acquired washed river sand with a fineness modulus of 2.34, silica fume, high range water reducer (ViscoCrete-10 supplied by Sika), tap water, and steel fibre (D = 0.2 mm, L = 13 mm), and the mix design consists of a 1:1:0.266:0.045:0.19:0.082 ratio by the weight of the sulphate-resisting cement, respectively.

2.1.2. Mixing Procedure

The mixing procedure of the ingredients involved mixing the dry constituents for up to three minutes, followed by adding the water and the superplasticizer. The mixing process took about 7–10 min to produce a consistent mix with acceptable workability. Finally, the steel fibre was added, and mixing was continued for three more minutes to ensure a homogeneous distribution of the fibres. The specimens were then cast into the moulds and then demoulded and stored in ambient curing conditions for 28 days.

2.1.3. Material Properties

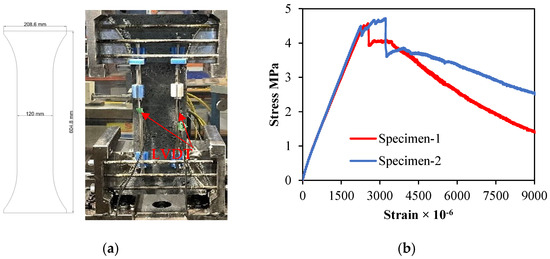

Material properties were extracted by conducting appropriate tests on UHPFRC and GFRP rebar specimens. The mentioned mix achieved an average compressive strength of 110 MPa when tested on the day of testing according to ASTM C39-20 [28], and a modulus of elasticity of 34 GPa according to ASTM 469-22 [29]. Dog bone specimens and their results, as shown in Figure 1, were tested to estimate the axial tensile strength of UHPFRC [30]. These dog bones have a height of 604 mm and a cross-section of 120 mm × 120 mm. GFRP rebars exhibited a linear-elastic behaviour up to fracture, and were estimated to have an ultimate strength of 1162 MPa with an elastic modulus of 26.3 GPa and a strain at failure of 44 × 10−3 µɛ.

Figure 1.

(a) Uniaxial tension test specimen and its setup and (b) stress–strain of direct tension.

2.2. Test Setup and Instrumentation

These tests were conducted under two major categories. The first one was to study the bond characteristics of the plain UHPFRC/UHPFRC interface. The effect of smoothness and adding an adhesion material to the bonding surfaces was investigated by conducting slant shear and shear key tests. The second major tests were conducted on the UHPFRC interface reinforced with GFRP shear stirrups. The details of these tests and instrumentation are described as follows.

2.2.1. Slant Shear Test

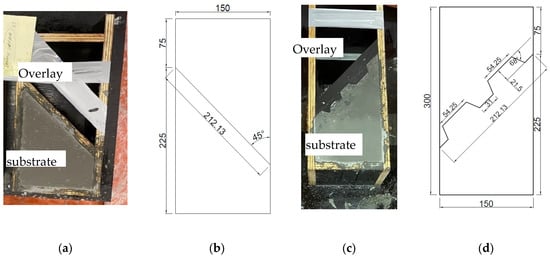

The slant shear test originally developed by Momayes et al. [31] was adopted in this study to evaluate the bond characteristics of UHPFRC, as illustrated in Figure 2a,b. There were two arrangements for bonding the shear joints. The first one was to cast the first segment of UHPFRC (substrate), followed by a curing period of six days. The second segment (overlay) was poured directly on the first segment to be mechanically bonded. The second arrangement was to cast the segments (substrate and overlay) separately, then, after six days of curing, the segments were connected by adding an adhesive material (epoxy resin). Subsequently, specimens were put in an ambient curing condition for 28 days. In the following sections, the results of the slant shear test will be shortened to SL for the smooth interface and SLX for the epoxy interface.

Figure 2.

(a) Picture of one part cast of shear slant. (b) Diagram of shear slant specimen. (c) Picture of one part cast of shear key. (d) Diagram of a shear key specimen. (Dimensions in mm).

2.2.2. Shear Key Test

Figure 2c,d shows the configuration of the shear key surface joints. There were also two arrangements for the shear key specimens. The first arrangement was to assemble the smooth surface segments of the specimens (substrate and overlay) mechanically at a 45° angle. Initially, the substrate of UHPFRC was cast and cured for six days. Then, a 3D-printed formwork was removed and the overlay was cast directly at a 45° angle to be assembled with the substrate. Similarly to the shear slant arrangement, the second arrangement was configured to assemble the joints with an adhesive material. The substrate and overlay of UHFRC were cast, followed by curing for 6 days. The formworks were removed and the overlay was assembled with the substrate at an angle of 45° using epoxy resin. The specimens were then stored and cured for 28 days under an ambient curing condition.

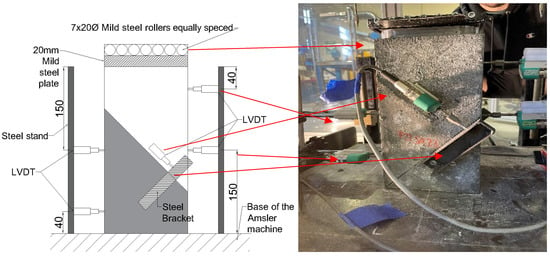

2.2.3. Instrumentation for Slant Shear and Shear Key Test

Figure 3 illustrates the setup of both slant shear and shear key tests. Nine linear variable differential transformers (LVDTs) per specimen were utilised for measuring the lateral and axial displacement. The lateral displacement was measured by two LVDTs, while the other two were attached to record any substrate movement during the tests. Also, another LVDT was attached at the mid-height of the specimen to precisely measure the slip along the interface of the joint. The remaining four LVDTs were attached to the corners of the load platen to measure the vertical displacement of the specimens under the load.

Figure 3.

Setup of slant shear and key shear tests (dimensions in mm).

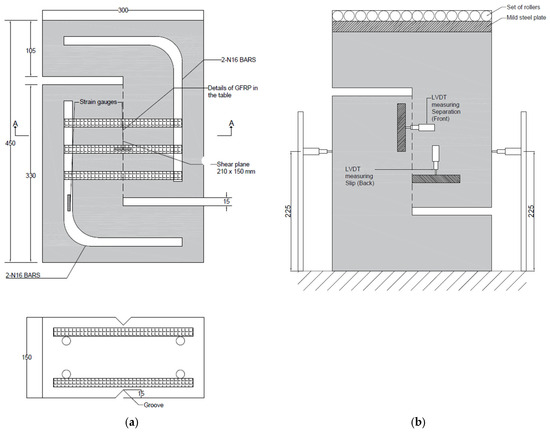

2.2.4. Push-Off Test

The second major category of tests performed in this study was the push-off tests to investigate the bond characteristics of the UHPFRC-GFRP rebars–UHPFRC interface. A test procedure originally developed by Hofbeck et al. [32] was utilised, as shown in Figure 4a. A total of six specimens were tested, wherein three specimens were fabricated to have a straight shear plane with different reinforcement ratios of transverse GFRP rebars. The shear plane was grooved in all specimens at a depth of 15 mm and a width of 30 mm. The only difference in the remaining three specimens was the angle of the shear plane. The dimensions and reinforcement details of the specimens are presented in Table 1.

Figure 4.

(a) Push-off specimens’ details and (b) the setup of the test (dimensions in mm).

Table 1.

Push-off specimens’ details.

2.2.5. Instrumentation for the Push-Off Test

Figure 4b shows the setup for all push-off tests. Two LVDTs were placed horizontally from both sides to measure the lateral displacement. Another LVDT was fixed on the specimen horizontally to measure the separation along the shear plane, and one more LVDT was attached vertically to measure the slip. The remaining LVDTs were attached to the load platen to measure the vertical displacement of the specimens under the load. For the GFRP rebars, a strain gauge was glued onto the rebars to measure the strain, and another strain gauge was attached to the deformed bar to ensure there was no premature failure or excessive load on this side of the specimen. The universal testing machine (Amsler) with an axial load capacity of 5000 kN was used to test the shear slant, shear key, and push-off specimens. A monotonically increasing load was gradually applied at a 100 kN/min load rate.

3. Results

3.1. Slant Shear and Shear Key Tests Results

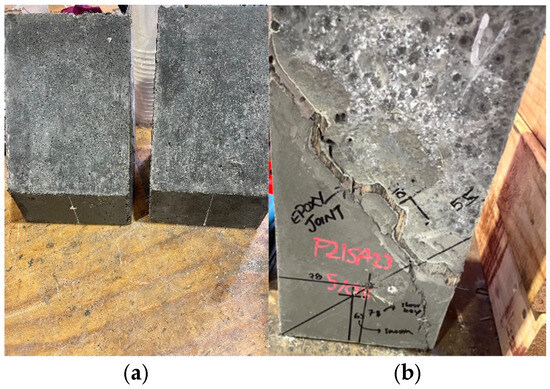

Figure 5a shows a typical failure mode of the slant shear specimens with and without an epoxy adhesive layer. The failure occurred suddenly after a marginal slip of about 0.17 mm, followed by complete sliding along the UHPFRC–UHPFRC interface. No cracking or damage was observed in either the substrate or the overlay, indicating that the interface was responsible for the failure and that the bond strength was lower than the material capacity of both layers.

Figure 5.

General failure (a) for slant shear and (b) for the shear key.

Figure 5b illustrates the typical failure pattern of the shear key specimens. Localised cracking developed in the substrate near the edges, but full separation between the layers did not occur. The shear keys effectively restricted sliding and enhanced the mechanical interlock at the interface, resulting in improved bond performance compared with the slant shear specimens.

In both test configurations, the development of a crack, opening along the interface, was monitored through the separation recorded by the LVDT positioned perpendicular to the shear plane. This measurement provided a direct indication of crack initiation, widening, and progression during loading, allowing the crack propagation behaviour to be evaluated consistently throughout the test.

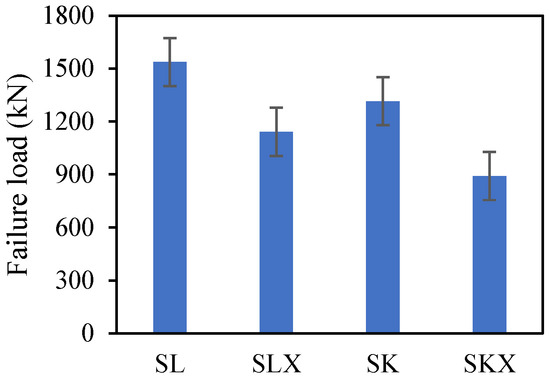

Figure 6 shows the failure load for both slant shear and shear key specimens, where the bond strength is obtained by dividing the maximum load by the surface area of the inclined interface. The shear slant specimens with a smooth surface achieved higher ultimate loads, and there was an unexpected premature failure in slant shear specimens bonded with adhesive and shear key specimens. It is worth noting that the interfaces in the specimens with the adhesive layers (SLX and SKX) failed at a lower load than the corresponding plain interfaces (SL and SK). Overall, the slant shear yielded higher ultimate loads due to fibre bridging the cracks across the interfaces, whereas in the specimens with an adhesive layer, this process was disrupted due to the adhesive layer; this phenomenon was also observed by Htut and Foster [33] and Peng et al. [34] for specimens with NSC. Moreover, the shear key prevented the failure from happening at the interface by increasing the contact surface area.

Figure 6.

Failure load of bond strength specimens.

3.2. Push-Off Results (Shear Transfer)

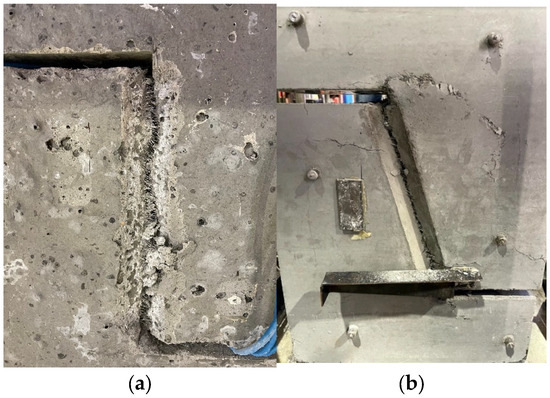

Typical failure modes in push-off shear specimens with shear reinforcements are shown in Figure 7a,b. The failure modes in the push-off specimens can be subdivided into two categories. In the first one, with the straight shear plane specimens (P-1, P-2, and P-3), the failure occurred after the rupturing of the GFRP rebars. The full separation of the interfaces happened before the load was transferred to the transverse reinforcement, pulling the GFRP rebars out, thus causing tension in the rebars. On the contrary, in the second case of push-off specimens with inclined shear plane interfaces, the failure occurred due to the crushing of the concrete along and around the interfaces, as can be seen in Figure 7b. In summary, the friction mechanism of the UHPFRC interfaces is caused by the slip along the interfaces that causes friction associated with the separation across the interfaces, which induces the dowel action in the GFRP rebars.

Figure 7.

Failure modes (a) of straight shear plane specimens and (b) of angled shear plane specimens.

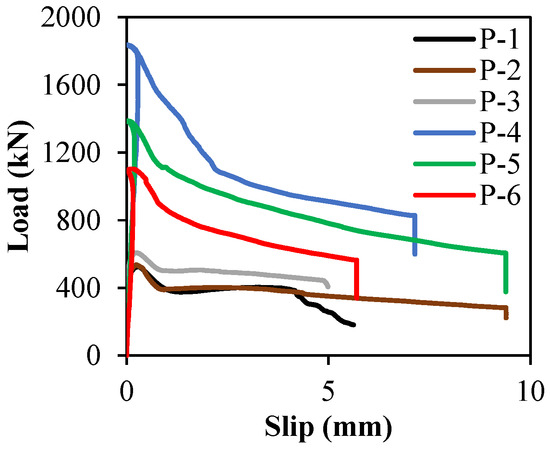

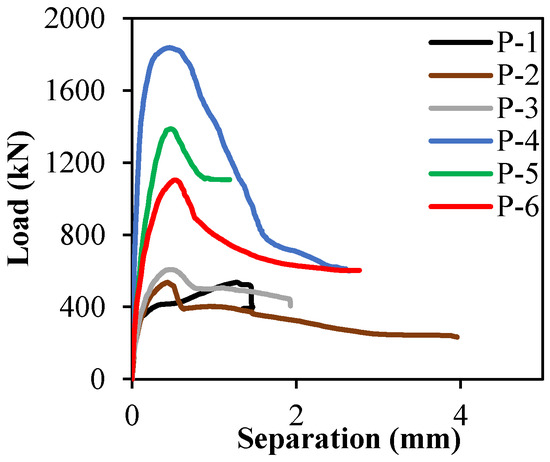

The load–slip relationship observed in all push-off specimens is shown in Figure 8. Note that the failure load increases by decreasing the angle of the shear plane, which proves that the angle of inclination of the shear plane is a critical parameter controlling the shear strength of the concrete interfaces. Also note that the failure occurred along the interfaces, as desired. Previous investigations on push-off specimens were conducted with conventional steel reinforcement that exhibits strain-hardening behaviour, and hence, in these cases, the failure along the interface is more commonly ductile failure after the maximum load is attained [13,17,18,19,21,32,34,35]. This behaviour was not observed in this study with GFRP rebars, as FRP rebars exhibit brittle behaviour and hence, there was a sudden drop in the load, as can be observed in Figure 8 and Table 2. However, the ductility of the specimens was much higher than in previous research [36,37] due to the presence of steel fibres and the higher capacity in the elongation of GFRP rebars.

Figure 8.

Load vs. slip.

Table 2.

Summary of the push-off key results.

Figure 9 shows the crack propagation along the shear plane. For all specimens, as shown in Table 2, the crack opening value at the maximum load ranges between 0.4 mm and 0.6 mm. As the separation along the interfaces widened, dowel action was induced by transverse reinforcement; additionally, the steel fibres across the interfaces provided a substantial amount of interfacial shear strength, as there is no aggregate interlock mechanism developed due to the absence of the coarse aggregate in the UHPFRC matrix [33]. Concisely, the shear transfer mechanism is initiated by the concrete cohesion, followed by the crack-bridging effect of the steel fibres, and finally due to the dowel action of the transverse reinforcement.

Figure 9.

Load vs. separation.

Figure 9 and Table 2 summarise the key outcomes of the push-off tests and highlight several design-relevant trends. The shear capacity increased slightly with higher reinforcement ratios in the vertical shear plane, whereas a substantial increase was observed when the shear plane was inclined, confirming that interface geometry plays a far more dominant role than reinforcement ratio alone. For instance, specimen P-4, with a 60° shear plane, achieved the highest shear strength despite having the same reinforcement ratio as specimen P-3, with a vertical plane, demonstrating that inclined interfaces can mobilise significantly higher frictional and fibre-bridging resistance. The measured slip perpendicular to the shear plane was also considerably lower in the inclined specimens, indicating improved interlock and reduced displacement demand in service conditions. The GFRP strain remained within 4 to 5 percent of its ultimate fracture strain at peak load, confirming that the bars did not reach their tensile capacity and that the shear transfer mechanism was largely governed by the interface behaviour rather than GFRP yielding. These findings suggest important design implications; inclined shear planes can be used to enhance shear transfer efficiency in UHPFRC connections without increasing reinforcement ratio, and detailing strategies for precast joints and repair interfaces may benefit from incorporating inclined geometries to minimise slip and improve load transfer. This also reinforces the need for future studies to establish quantifiable limits for reinforcement ratios and optimal shear plane angles to support design-oriented recommendations for UHPFRC–GFRP interfaces.

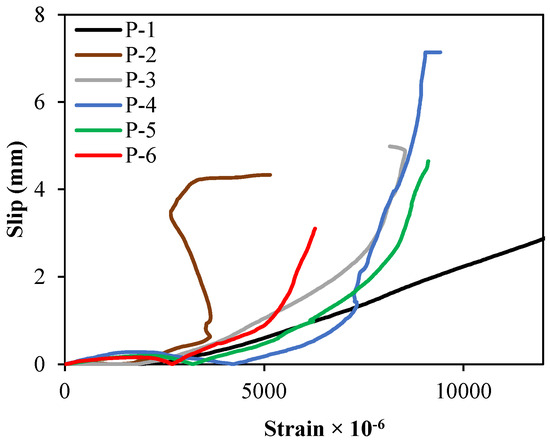

3.2.1. Effect of GFRP

Figure 10 illustrates the relationship between slip along the shear plane and the strain in the transverse GFRP bars. For the vertical shear plane specimens (P-1, P-2, and P-3), the strain in the GFRP rebars increases steadily as slip develops, indicating the progressive engagement of dowel action. These specimens also show noticeably larger slip values compared with the inclined shear plane specimens. In contrast, the inclined specimens (P-4, P-5, and P-6), which share the same reinforcement ratio as P-3, exhibit rapid increases in slip, while the GFRP strain remains relatively low, around 10 to 20 percent of the fracture strain. This behaviour confirms that the inclined shear plane mobilises higher frictional resistance and delays the transition to dowel action. As a result, the inclined specimens experience much less slip and more effective interface engagement compared with the vertical shear plane specimens, despite having the same reinforcement ratio.

Figure 10.

Slip vs. GFRP strain values of the transverse rebars.

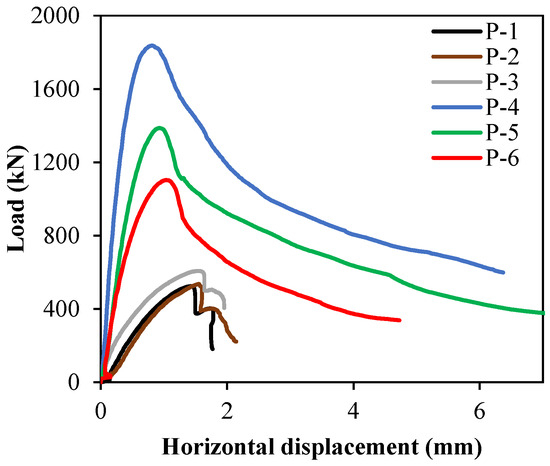

3.2.2. Horizontal Displacement

Figure 11 illustrates the lateral displacement response of the push-off specimens. In this study, slip and lateral displacement are measured independently using two different LVDTs. Slip is recorded at the 15 mm groove provided in the specimen, which captures the relative movement between the two concrete blocks at the shear interface, as shown in Figure 8. A separate LVDT is placed horizontally to measure the global lateral displacement of the upper block under loading. It can be seen that the specimens without an angled shear plane have limited lateral displacement to 2 mm. A linear increase in the curve for all specimens can be observed until the ultimate load. In P-1, P-2, and P-3 specimens, which do not have an angled shear plane, the displacement stopped immediately after the failure load. However, the ribbed GFRP could efficiently contribute to this limitation of lateral displacement, as reported in [34]. Meanwhile, in the other specimens where there is an inclination in the shear plane, the angle between the GFRP rebars and the concrete could affect the bond strength, resulting in this rapid and continuous increase after the ultimate load.

Figure 11.

Load vs. horizontal displacement.

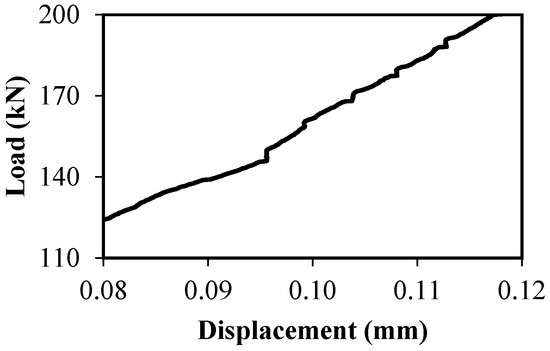

3.2.3. Fibre Influence

The steel fibre ratio is constant in this set of specimens. It has been investigated earlier by Peng et al. and Khaloo et al. [34,38], who found that increasing the fibre ratio increases the ultimate shear strength. It can be noticed that the fibre orientation indicates the effect of the steel fibres on increasing the bond in the shear plane. In the tensile state, where the separation happens, the steel fibres can significantly increase the bond strength, improving the ultimate shear strength. Figure 12 shows a portion of the load and displacement curve as a general indication for all specimens. The sudden increase in the load in the curve appeared during the increase in the load process, which showed that the full separation between the concrete interfaces happened due to the influence of the steel fibres in bridging this separation. Therefore, the cracks in the separation process across the shear plane were slightly closed by the effect of the steel fibres. Another mechanism here is the achievement of a transfer between the concrete bond and steel fibres. However, the impact of the fibres has been noticed for all specimens.

Figure 12.

Indication of the effect of the steel fibres.

3.2.4. Effect of the Angled Shear Plane

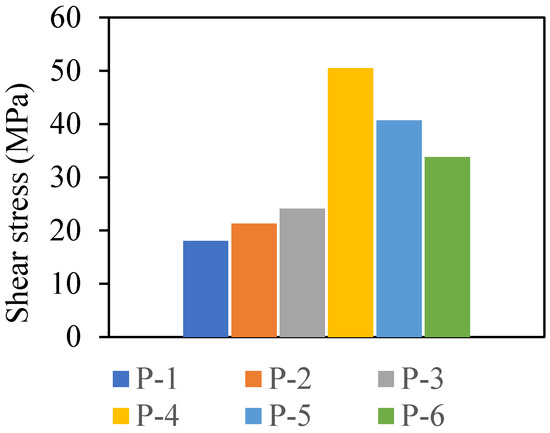

The shear strength of the specimens is shown in Figure 13. With an identical reinforcement ratio from P-3 to P-6, the shear strength is varied by changing the angle of the shear plane. The shear plane has been increased by changing the angle, and the longest shear plane is P-4, which has the highest shear strength. Similar trends were observed in the study by Mattock and Hawkins in [19], except that the rebars in their study were perpendicular to the shear plane, whereas the rebars were fixed horizontally for all specimens in this study. The shear transfer mechanism occurred with full separation along the shear plane, which means that the shear transfer mechanism happened in these specimens. In P-4, P-5, and P-6, the shear strengths exceeded the value of 0.3 f’c, which has been set in recent research and codes [6,19,21,37].

Figure 13.

Shear stress of the push-off specimens.

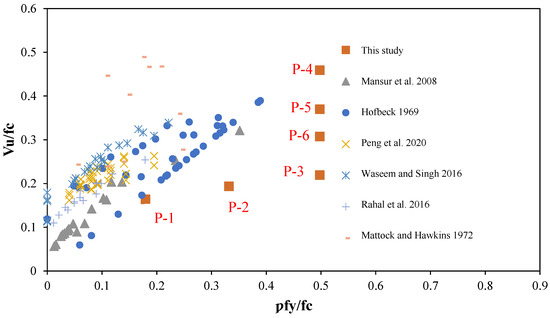

3.2.5. Comparison with Previous Experiments

The relationship between the normalised experimental shear transfer strength and reinforcement index obtained from the present study is plotted in Figure 14 and Figure 15, wherein Figure 14 presents the test results from six different investigations [18,19,32,34,35,39], where the transverse reinforcement is the conventional steel rebars, and Figure 15 shows the test results from two studies by [40] and Alkatan [41], where the GFRP rebars are the transverse reinforcement across the shear plane. These test results capture a wide spectrum of test variables. Firstly, Hofbeck et al. [32] mainly investigated the uncracked and cracked shear plane. Secondly, Mattock and Hawkins [18] varied the reinforcement ratio, with a concrete strength of around 27–44 MPa, and initially uncracked and cracked specimens. Thirdly, Mansur et al. [19] studied the effect of high-strength concrete up to 87 MPa. Then, Rahal et al. [39] added a new set of data related to self-compacting concrete and non-pre-cracked specimens, with the addition of data from [35], where the recycled aggregate was used. Lastly, Peng et al. [34] investigated the effect of incorporating steel fibres into the concrete matrix. Whereas the reinforcement index in this study ranges between 0.2 and 0.5, which is higher than the other studies’ ranges (0 to 0.4), the normalised shear strength of P-1 makes it the only specimen to lie near the scatter. Therefore, results plotted for specimens P-2 and P-3 indicate that doubling the reinforcement index does not improve the shear capacity. This behaviour is attributed to the clamping forces or dowel action effect where the shear transfer happened. Changing the angle of the shear plane resulted in a higher shear transfer. Hence, P-4 has the highest normalised value, nearly in the same line as the results from [32]. However, the shear strength in this case and in P-5 and P-6 exceeds the recommendation made by many authors to limit the normalised shear strength to 0.3 or less. This upper limit has been set to ensure that the steel yields at failure.

Figure 14.

Normalised experimental shear transfer strength vs. reinforcement index [18,19,32,34,35,39].

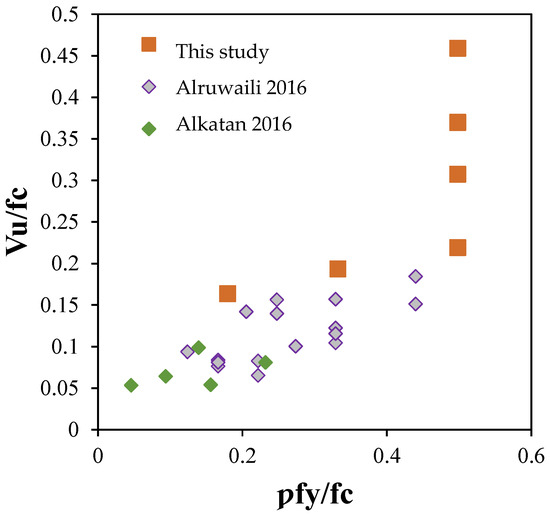

Figure 15.

Normalised experimental shear transfer strength vs. reinforcement index (GFRP rebars) [40,41].

However, in Figure 15, the data of specimens with GFRP rebars as shear transverse reinforcement from studies conducted by Alruwaili [40], where the compressive strength of the concrete is 41 MPa, and Alkatan [41], with the compressive strength of the concrete between 30 MPa and 50 MPa, are plotted along with the data from this study. The effect of the compressive strength is pronounced with the same GFRP rebar ratio for specimens P-1 to P-3, which increases the ultimate shear strength. However, as mentioned earlier, the angled shear plane has significantly affected the results, increasing the shear strength. For the GFRP rebars, more data is needed to better explain the behaviour of GFRP rebars as a reinforcement across the shear plane.

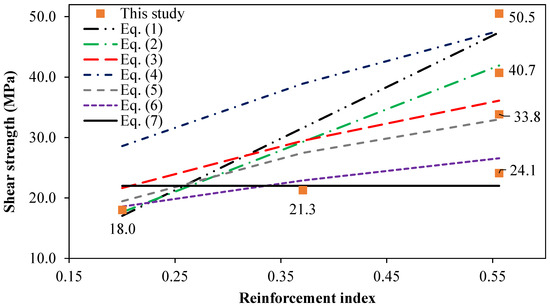

3.2.6. Comparison with Existing Methods

The experimental results will be compared with the equations in the literature review and the ACI code [6]. These equations do not precisely predict the shear strength of the push of specimens but conservatively predict it. Starting from the ACI [6], the limitation of the upper shear strength has been reduced for more safety requirements. The expression is as follows:

where µ is the coefficient of friction equal to 1.4.

Figure 16 presents this study’s experimental shear strength results and the predicted shear strength according to Equations (1)–(7). Generally, the equations do not predict the experimental results for two reasons: the angle of the shear plane and the upper limit in Equations (4)–(7), which is equal to 0.3. However, all equations have a linear relationship. Equation (1) has predicted P-1 conservatively, as well as Equations (2) and (6). However, other equations have overpredicted the vertical shear plane, which should not happen in the prediction process to prevent unexpected failures. For the angled shear plane, all equations have under-predicted P-4. Nevertheless, the prediction must be adjusted to suit the GFRP transverse rebars.

Figure 16.

Experimental and predicted shear strength.

Additionally, predictions for angled shear planes must be developed to achieve an acceptable range of predictions. Overall, Equation (6), presented by Ahmed et al. [37], has the best fit for the vertical shear plane, and it could be used as an approximation, with a slight alteration of the shear coefficient value to 2.6. This approximation value is just a start for this kind of experimentation, and it could be improved as more experimental data become available. These findings reinforce the broader trend reported in recent studies, where traditional shear prediction equations often fail to capture the behaviour of FRP-reinforced systems due to the linear elastic response and lower stiffness of FRP bars. This has motivated the development of enhanced prediction approaches, including data-driven and machine learning models [42], which further support the need to adjust existing equations for GFRP reinforced UHPFRC interfaces.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

In this study, the shear-friction mechanism of UHPFRC–UHPFRC interfaces with different characteristics has been investigated. Slant shear and shear key specimens were tested to obtain the shear strength of the UHPFRC–UHPFRC interfaces. The shear transfer across uncracked specimens, called push-off specimens, with GFRP rebars as a transverse reinforcement was also studied. Furthermore, vertical shear planes with different reinforcement and angled shear planes with constant reinforcement ratios were studied. The following conclusion can be drawn:

- The effect of using steel fibre to bridge the cracks and maximise the shear strength of slant shear and the shear key was observed, where the shear strength of the mechanical bond is higher than the shear strength with an epoxy adhesive layer. This is due to the interference of the epoxy layer, which prevents the bridging of the steel fibre.

- The provision of shear keys is beneficial in preventing sudden failure because the interlocking action increases mechanical engagement along the interface. This enhances frictional resistance, delays slip development, and provides a more gradual load-transfer mechanism during shear.

- All the push-off test specimens failed after considerable separation of the interface in the grooved plane. The presence of steel fibre affects the friction behaviour of the specimens. After transferring from the shear to the transverse GFRP rebars due to dowel action, the strain increased dramatically without any increase in the shear strength.

- Push-off specimens with angled shear planes failed at higher shear loads due to the increased contribution of friction and fibre bridging along the inclined surface. The inclined geometry mobilises more interfacial resistance before dowel action becomes dominant, resulting in significantly higher shear capacity.

- None of the above-outlined equations, e.g., Equations (1)–(7), have provided a close prediction of the shear strength with GFRP rebars, especially for the angled shear plane. Most of them have over-predicted the ultimate shear strength.

This study aimed to discover a new way for more information to be gained about the use of GFRP rebars, which have benefits in terms of the effect of corrosion on steel. The presence of cracks is inevitable and anti-corrosion reinforcement could help provide the structures with greater protection. However, the closed-tie GFRP transverse reinforcement could be carefully used without hindering its strength. It is known that GFRP rebars are brittle, and improper bending could significantly affect their strength. Finally, more experimental data on the use of GFRP rebars as transverse reinforcement and angled shear plane are needed to approximately establish a pattern for the behaviour of this kind of specimen.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings15244472/s1.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges Mohamed Mohamed Sadakkathulla for his valuable insights and constructive feedback on this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abbas, S.; Nehdi, M.L.; Saleem, M.A. Ultra-High Performance Concrete: Mechanical Performance, Durability, Sustainability and Implementation Challenges. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2016, 10, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.-Y.; Yoon, Y.-S. A Review on Structural Behavior, Design, and Application of Ultra-High-Performance Fiber-Reinforced Concrete. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2016, 10, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, B.; Chen, W.; Liu, H.; Li, H. Multi-Scale Study on Interfacial Bond Failure between Normal Concrete (NC) and Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC). J. Build. Eng. 2022, 57, 104808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzad, M. Retrofitting of Bridge Elements Subjected to Predominantly Axial Load Using UHPC Shell. Ph.D. Thesis, Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- AASHTO. AASHTO LRFD Bridge Design Specifications, 4th ed.; American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; ISBN 9781560514510. [Google Scholar]

- ACI Committee 318. Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2014; pp. 1–524. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, P.M.D.; Júlio, E.N.B.S. A State-of-the-Art Review on Shear-Friction. Eng. Struct. 2012, 45, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilch, K.; Reinecke, R. Capacity of Shear Joints between High-Strength Precast Elements and Normal-Strength Cast-in-Place Decks. In Proceedings of the PCI/FHWA/FIB International Symposium on High Performance Concrete, Orlando, FL, USA, 25–27 September 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Beushausen, H. The Influence of Concrete Substrate Preparation on Overlay Bond Strength. Mag. Concr. Res. 2010, 62, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momayez, A.; Ehsani, M.R.; Ramezanianpour, A.A.; Rajaie, H. Comparison of Methods for Evaluating Bond Strength between Concrete Substrate and Repair Materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hooton, R.D.; Zhang, X. Effects of Interface Roughness and Interface Adhesion on New-to-Old Concrete Bonding. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 151, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayeh, B.A.; Abu Bakar, B.H.; Megat Johari, M.A.; Voo, Y.L. Mechanical and Permeability Properties of the Interface between Normal Concrete Substrate and Ultra High Performance Fiber Concrete Overlay. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 36, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkeland, P.W.; Birkeland, H.W. Connections in Precast Concrete Construction. ACI J. Proc. 1966, 63, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattock, A.H. Shear Transfer in Concrete Having Reinforcement at an Angle to the Shear Plane. ACI Symp. Publ. 1974, 42, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walraven, J.; Frenay, J.; Pruijssers, A. Influence of Concrete Strength and Load History on the Shear Friction Capacity of Concrete Members. PCI J. 1987, 32, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermansen, B.R.; Cowan, J. Modified Shear-Friction Theory for Bracket Design. ACI J. Proc. 1974, 71, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoff, G.C. High Strength Lightweight Aggregate Concrete for Arctic Applications--Part 3: Structural Parameters. Spec. Publ. 1993, 136, 175–246. [Google Scholar]

- Mattock, A.H.; Hawkins, N.M. Shear Transfer in Reinforced Concrete—Recent Research. PCI J. 1972, 17, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, M.A.; Vinayagam, T.; Tan, K.-H. Shear Transfer across a Crack in Reinforced High-Strength Concrete. J. Mater. Civil. Eng. 2008, 20, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loov, R.E. Design of Precast Connections. In Proceedings of the Seminar Organized by Compa International Pte, Ltd., Singapore, 25–27 September 1978; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Mau, S.T.; Hsu, T.T.C. Influence of Concrete Strength and Load History on The Shear Friction Capacity of Concrete Members-Comment. J. Prestress. Concr. Inst. 1988, 33, 166–168. [Google Scholar]

- Nanni, A.; De Luca, A.; Zadeh, H. Reinforced Concrete with FRP Bars: Mechanics and Design; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; pp. 970–978. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Li, W.; Lu, Y.; Hu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, P.; Ke, L.; Yu, J. Axial Compressive Behavior and Failure Mechanism of CFRP Partially Confined Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 426, 136104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lu, Y.; Wang, P.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, L.; Shi, T.; Zheng, K. Comparative Study of Compressive Behavior of Confined NSC and UHPC/UHPFRC Cylinders Externally Wrapped with CFRP Jacket. Eng. Struct. 2023, 292, 116513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Yu, J.; Lu, Z.; Chen, Y. Effects of Simulated Seawater on Static and Fatigue Performance of GFRP Bar–Concrete Bond. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 68, 105985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Tian, J.; Li, C.; Guo, R.; Bai, Y.; Ji, Q.; Peng, Z.; He, T.; et al. Design of Novel Glass Fiber Reinforced Polypropylene Cable-Anchor Component and Its Long-Term Properties Exposed in Alkaline Solution. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobuz, H.R.; Visintin, P.; Ali, M.S.M.; Singh, M.; Griffith, M.C.; Sheikh, A.H. Manufacturing Ultra-High Performance Concrete Utilising Conventional Materials and Production Methods. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 111, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C39/C39M-20; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM C469/C469M-22; Standard Test Method for Static Modulus of Elasticity and Poisson’s Ratio of Concrete in Compression. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Singh, M.; Sheikh, A.H.; Mohamed Ali, M.S.; Visintin, P.; Griffith, M.C. Experimental and Numerical Study of the Flexural Behaviour of Ultra-High Performance Fibre Reinforced Concrete Beams. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 138, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momayez, A.; Ramezanianpour, A.A.; Rajaie, H.; Ehsani, M.R. Bi-Surface Shear Test for Evaluating Bond between Existing and New Concrete. ACI Mater. J. 2004, 101, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofbeck, J.A.; Ibrahim, I.O.; Mattock, A.H. Shear Transfer in Reinforced Concrete. ACI J. Proc. 1969, 66, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htut, T.N.S.; Foster, S.J. Unified Model for Mixed Mode Fracture of Steel Fibre Reinforced Concrete. In Proceedings of the Fracture Mechanics of Concrete and Concrete Structures–High Performance, Fiber Reinforced Concrete, Special Loadings and Structural Applications, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 23–28 May 2010; pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Zhao, P.-Z.; Wang, S.; Lee, S.W.; Kang, S.-B. Interface Shear Transfer in Reinforced Engineered Cementitious Composites under Push-off Loads. Eng. Struct. 2020, 206, 110013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, S.A.; Singh, B. Shear Transfer Strength of Normal and High-Strength Recycled Aggregate Concrete—An Experimental Investigation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 125, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, W.; Amin, A.; Beck, A.; Lee, M. Shear Transfer across Cracks in Steel Fibre Reinforced Concrete. Eng. Struct. 2019, 186, 508–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Bhargava, P.; Chourasia, A. Shear Transfer Strength of Uncracked Interfaces: A Simple Analytical Model. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 192, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaloo, A.R.; Kim, N. Influence of Concrete and Fiber Characteristics on Behavior of Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete under Direct Shear. Mater. J. 1997, 94, 592–601. [Google Scholar]

- Rahal, K.N.; Khaleefi, A.L.; Al-Sanee, A. An Experimental Investigation of Shear-Transfer Strength of Normal and High Strength Self Compacting Concrete. Eng. Struct. 2016, 109, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alruwaili, M. Shear Transfer Mechanism in FRP Reinforced Composite Concrete Structures. Master’s Thesis, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alkatan, J. FRP Shear Transfer Reinforcement for Composite Concrete Construction. Master’s Thesis, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, A.; Shahmansouri, A.A.; Taslimi, A.; Naser, M.Z.; Zhou, Y. Shear Capacity of FRP-RC Beams: XML Modeling and Reliability Evaluation. Structures 2025, 81, 110150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).