Systematic Literature Review: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Paving Blocks

Abstract

1. Introduction

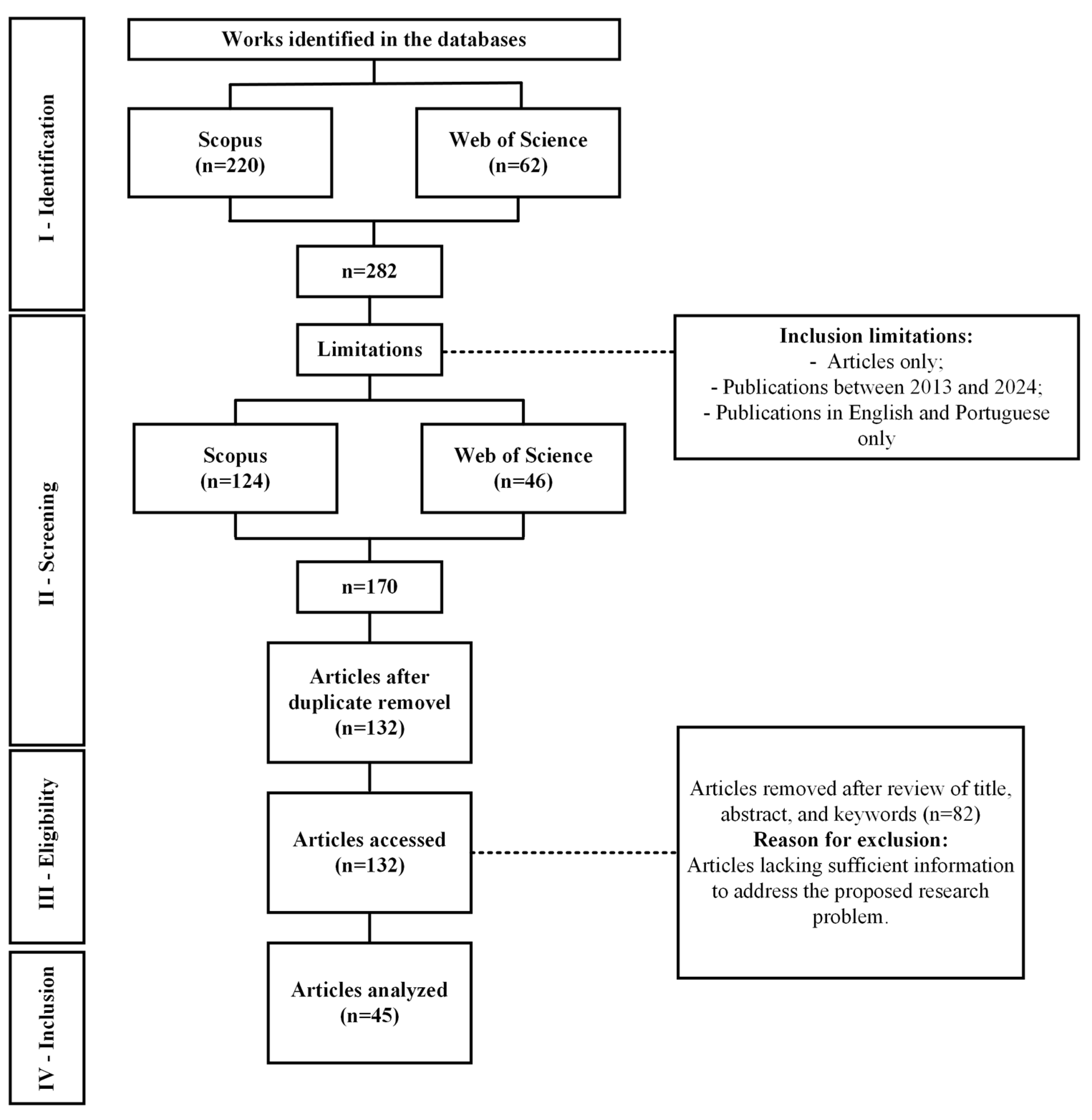

2. Research Method and Article Selection Process

3. Results

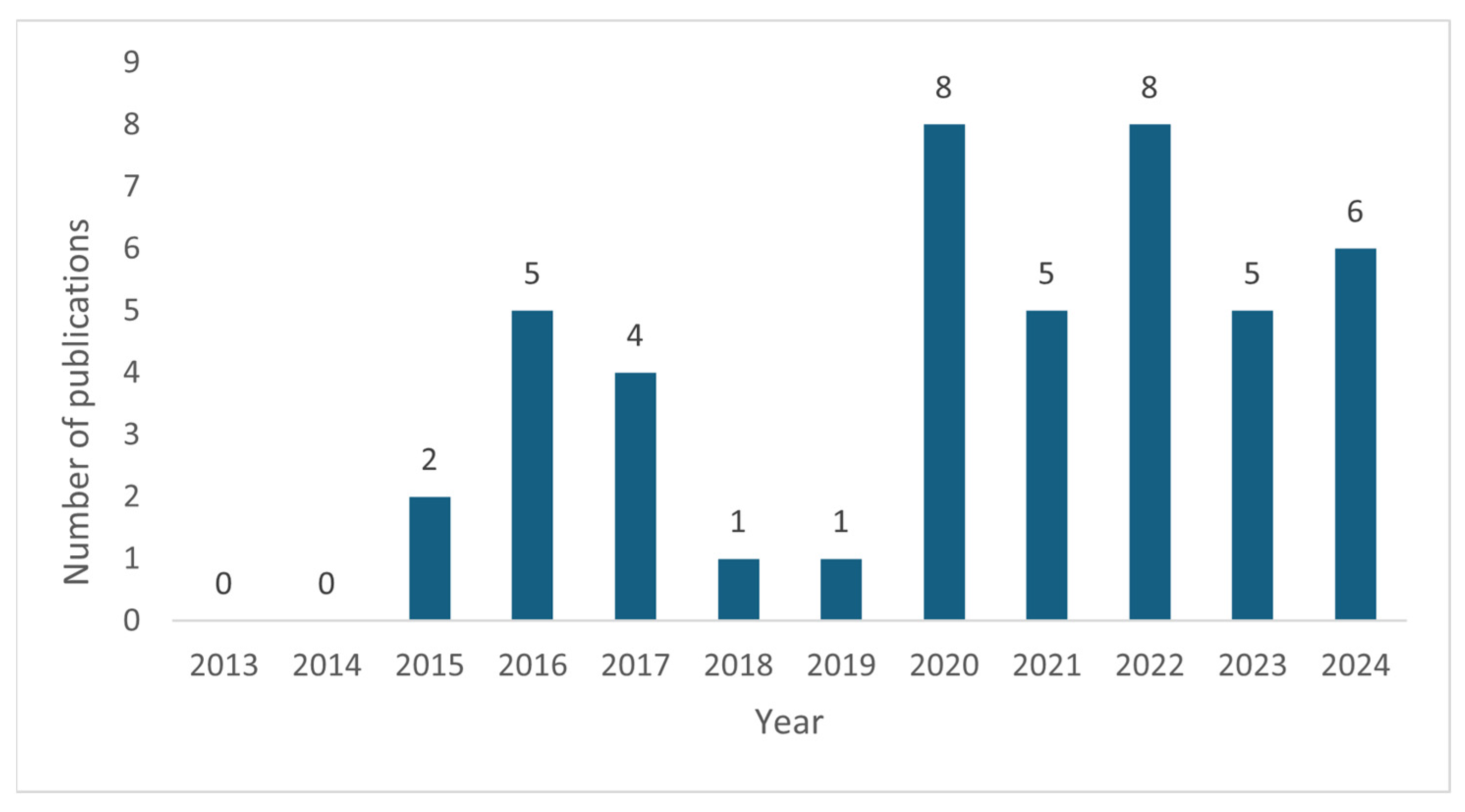

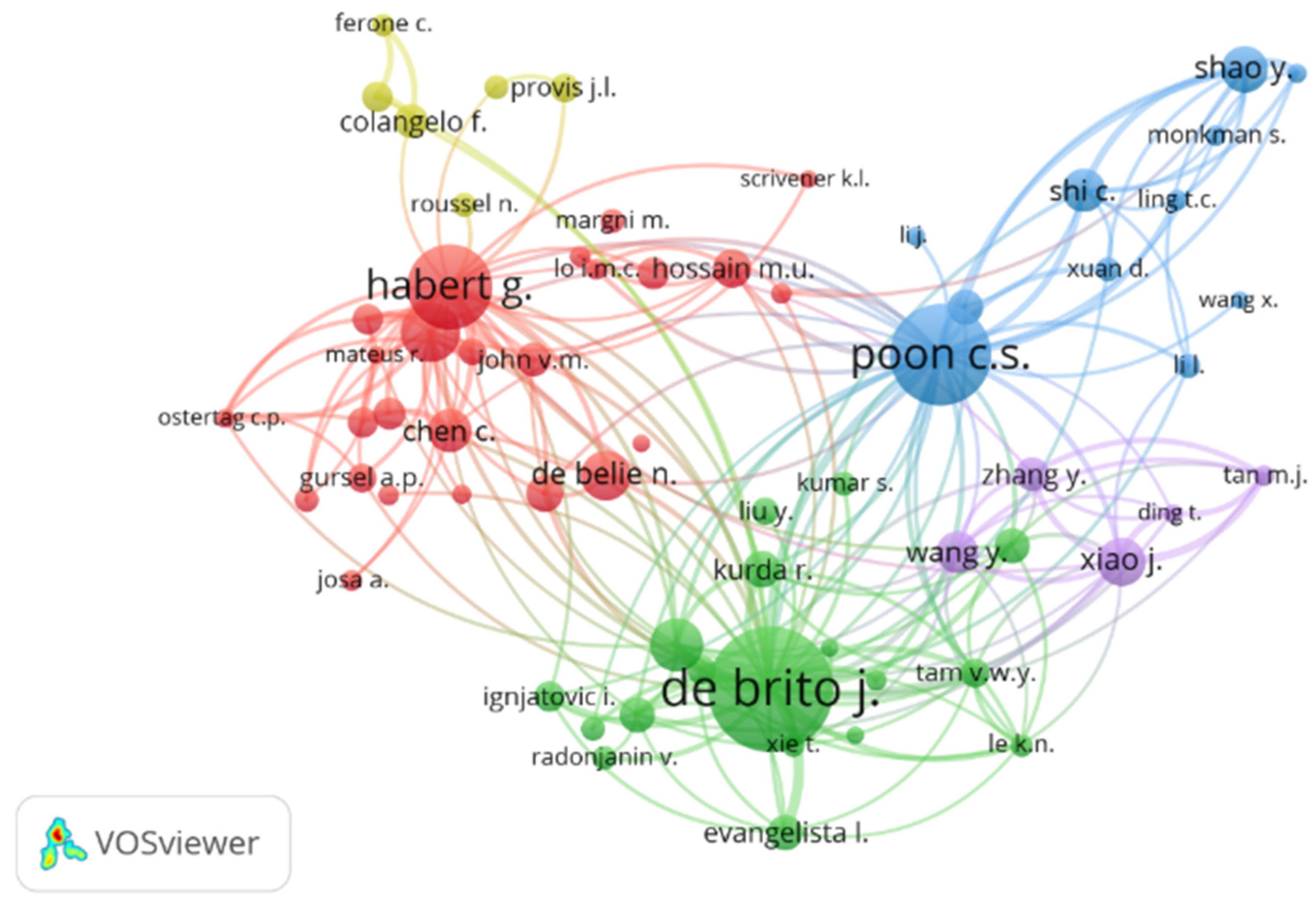

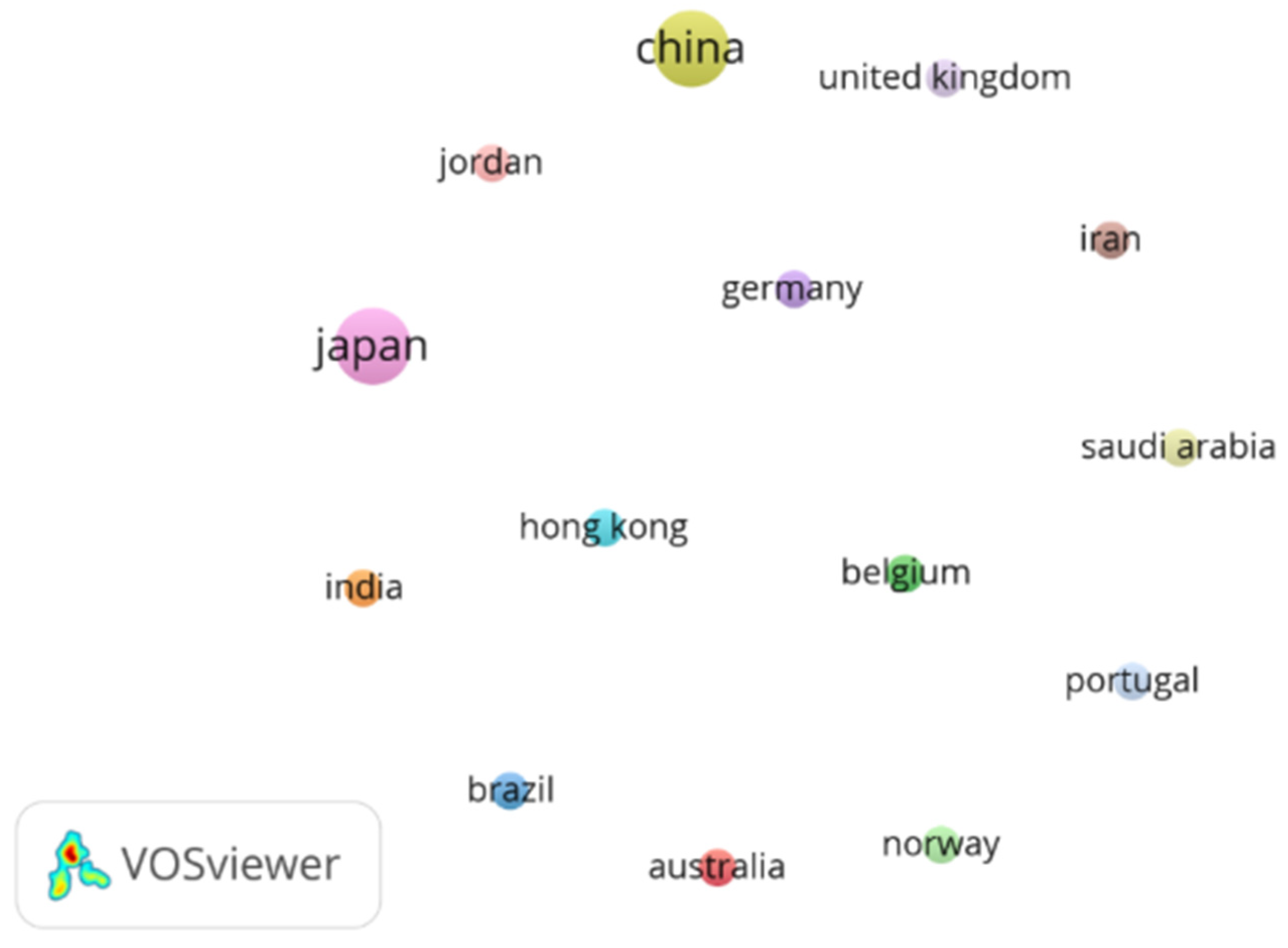

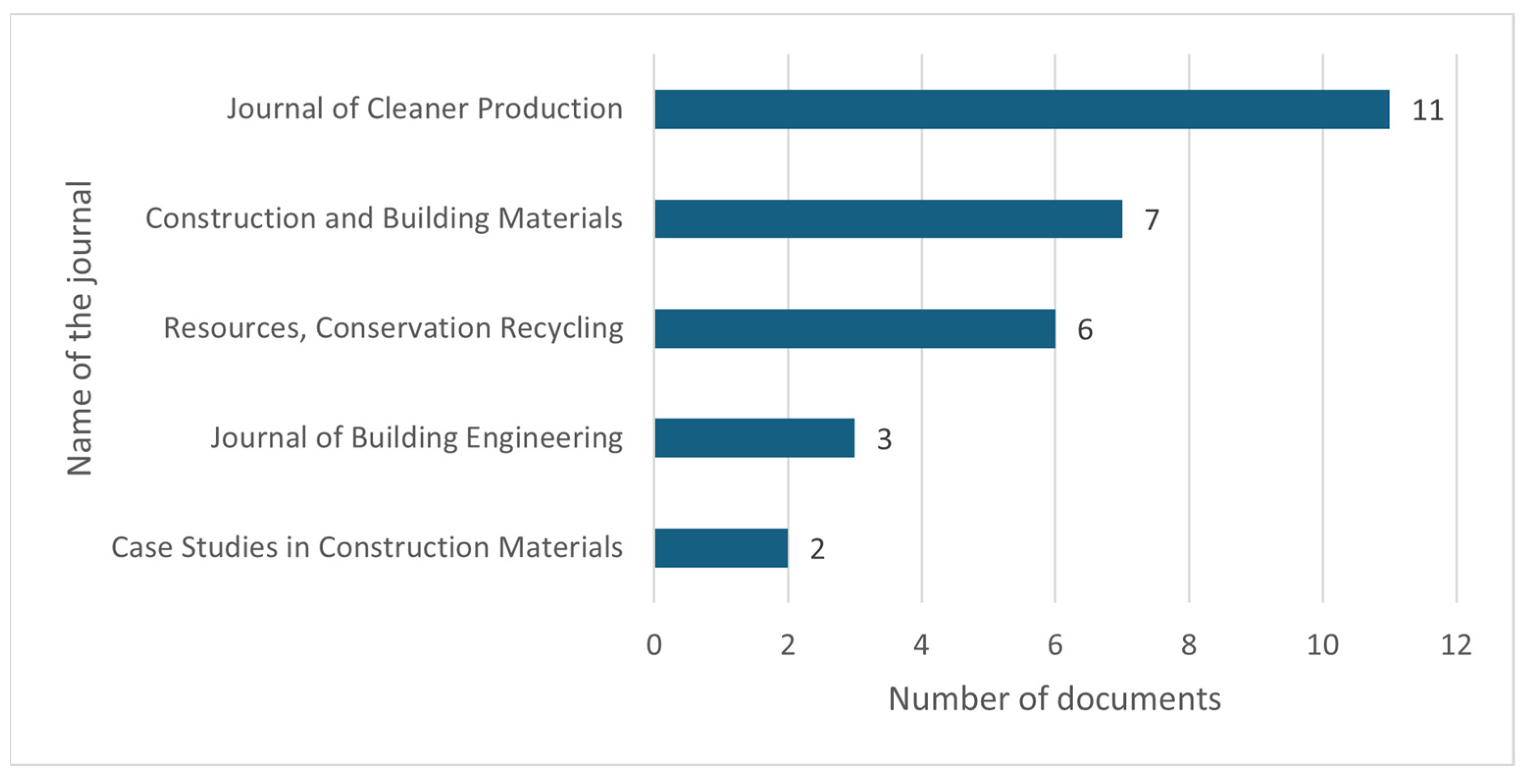

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

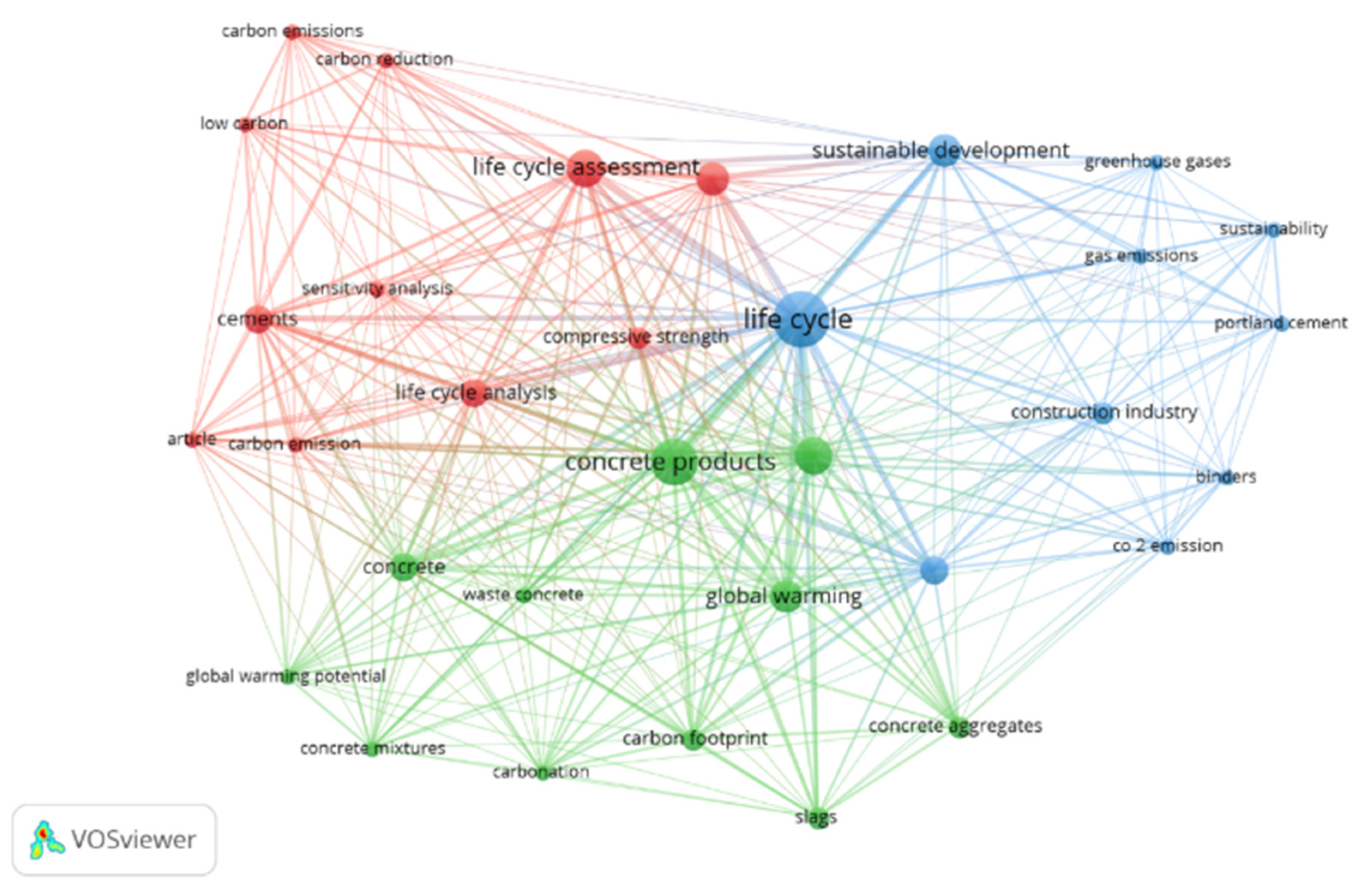

Content Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. PRISMA Checklist

| Section | Item | PRISMA-ScR Checklist Item | Reported on Page |

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | Page 1 |

| Abstract | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | Page 1 |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | Page 1 and 2 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | Page 2 |

| Methods | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | Page 2 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | Page 3 |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | Page 3 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | Page 3 |

| Selection of sources of evidence | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | Page 3 |

| Data charting process | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | Page 3 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | Page 3 |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | ----- |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | Page 4 |

| Results | |||

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | Page 3 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | Page 4 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | ---- |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | Page 7 |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | Page 7, 8 and 9 |

| Discussion | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | Page 10 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | Page 10 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | Page 11 |

| Funding | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | - |

Appendix B. List of Studies Included in the Review

| ID | (i) Which Environmental Impact Indicators Are Most Commonly Used in LCA Studies of Paving Blocks? | (ii) What Mix Proportions Are Most Commonly Used in the Production of Paving Blocks? | Reference |

| 1 | CO2 emissions, pH analysis. | - | [27] |

| 2 | CO2 emissions and global warming potential. | - | [28] |

| 3 | Global warming potential, abiotic depletion potential, and cumulative energy demand. | The mix of paving blocks for heavy traffic applications was 1:2:4 (cement, sand, coarse aggregate) by mass, with a water/cement ratio of 0.3. | [22] |

| 4 | Global warming potential and CO2 emissions. | Partial replacement of cement with fly ash, with the water/cement ratio ranging from 0.37 to 0.42 for the different mixes. | [29] |

| 5 | Global warming potential. | Mixes with 50% cement replacement by fly ash and use of slag as aggregate. | [30] |

| 6 | Global warming potential and cumulative energy demand. | - | [31] |

| 7 | Global warming potential, ozone depletion potential, acidification potential. | Partial replacement of Portland cement with blast furnace slag and micro silica. | [32] |

| 8 | Global warming potential and cumulative energy demand. | Partial replacement of Portland cement with fly ash, blast furnace slag, and silica fume. | [23] |

| 9 | Global warming potential, ozone depletion potential, and acidification potential. | Mix proportions used for concrete production: Sand: 340 kg; Aggregates: 441 kg; Water: 80 kg. | [33] |

| 10 | Global warming potential. | Mixes with 10%, 40%, 80%, and 100% recycled construction and demolition aggregates. | [34] |

| 11 | Global warming potential and cumulative energy demand. | - | [35] |

| 12 | CO2 emissions and cumulative energy demand. | - | [36] |

| 13 | Global warming potential, water depletion, and ecotoxicity. | Mixes ranged from 10% to 30% cement replacement with ceramic powder. | [37] |

| 14 | Global warming potential, chloride resistance, and carbonation resistance. | The concrete mix varied with 0%, 20%, and 50% replacement of natural aggregates with recycled aggregates. | [38] |

| 15 | Global warming potential and CO2 emissions. | Blast furnace slag (BFS) was used as a precursor, rice husk ash (RHA) as a silica source, and olive pit biomass ash as an alkaline source. | [39] |

| 16 | Global warming potential, eutrophication, acidification, and cumulative energy demand. | Proportions ranging from 0% to 100% replacement of natural aggregates with recycled aggregates. | [40] |

| 17 | CO2 and C2H4 emissions, and cumulative energy demand. | - | [41] |

| 18 | Global warming potential, fossil resource consumption, and eutrophication. | Replacement of 20% of natural aggregate with plastics. | [42] |

| 19 | Global warming potential, abiotic resource depletion, acidification, and eutrophication. | - | [43] |

| 20 | Global warming potential, acidification potential, and eutrophication potential. | The proportions used were cement, sand, and gravel in a 1:2:4 ratio, with a water/cement ratio of 0.62. | [12] |

| 21 | Global warming potential and cumulative energy demand. | Replacement of up to 25% of natural aggregates with recycled plastic. | [44] |

| 22 | Global warming potential and air pollutants such as CO, NOx, and SO2. | Mixes with up to 30% rice husk ash and 5% limestone powder. | [45] |

| 23 | Global warming potential and cumulative energy demand. | Mixes with 410 kg of cement, 650 kg of fine aggregates, 1207 kg of coarse aggregates, and 135 kg of water per m3. | [46] |

| 24 | Cumulative energy demand, greenhouse gas emissions, and acidification potential. | Mixes with 35–80% replacement of natural aggregates with recycled aggregates, and the use of fly ash. | [47] |

| 25 | Global warming potential, eutrophication potential, and acidification potential. | Varied mixes of recycled aggregates and demolished concrete blocks with 30% and 70% replacement. | [48] |

| 26 | Global warming potential and greenhouse gas emissions. | The proportions used were cement, sand, and gravel in a 1:3:6 ratio by mass, with a water/cement ratio of approximately 0.35 to 0.45. | [49] |

| 27 | Global warming potential and cumulative energy demand. | The proportions used were cement, sand, and gravel in a 1:3:6 ratio by mass, with a water/cement ratio of approximately 0.38. | [50] |

| 28 | Global warming potential, acidification potential, eutrophication potential, and cumulative energy demand. | The proportions used were cement, sand, and gravel in a 1:3:6 ratio by mass, with a water/cement ratio of 0.40. | [51] |

| 29 | Global warming potential and cumulative energy demand. | Proportions ranging from 20% to 80% recycled aggregates and 14% to 18% cement, with a water/cement ratio of 0.3. | [52] |

| 30 | Global warming potential, acidification potential, and cumulative energy demand. | The proportions used were cement, sand, and gravel in a 1:3:6 ratio by mass, with a water/cement ratio of approximately 0.40. | [20] |

| 31 | Global warming potential and greenhouse gas emissions. | Replacement of up to 10% of cement with recycled particles. | [53] |

| 32 | Global warming potential and greenhouse gas emissions. | 10% of natural aggregates replaced with recycled plastic. | [54] |

| 33 | Global warming potential and ozone depletion potential. | Mix with 280 kg of cement, 120 kg of water, 400 kg of recycled fine aggregates, and 1320 kg of recycled coarse aggregates. | [55] |

| 34 | Reduction in new aggregate extraction and CO2 emissions. | 100% of coarse aggregates replaced with recycled aggregates. | [56] |

| 35 | CO2 emissions. | - | [57] |

| 36 | CO2 emissions. | Mix with 380 kg of cement/m3 and a water/cement ratio of 0.53. | [58] |

| 37 | CO2 emissions and cumulative energy demand. | Cement replaced with fly ash in proportions of 20%, 40%, and 60%. | [59] |

| 38 | CO2 emissions and cumulative energy demand. | Partial replacement of natural aggregates with recycled aggregates. | [60] |

| 39 | Global warming potential, acidification, eutrophication, and ecotoxicity. | Mixes with different proportions of recycled aggregates and cement, with up to 100% replacement of natural aggregates by recycled aggregates. | [61] |

| 40 | Global warming potential, abiotic resource depletion, acidification, and eutrophication. | Replacement of 30% to 100% of natural aggregates with recycled aggregates. | [62] |

| 41 | Global warming potential, cumulative energy demand, and energy cost. | Partial replacement of natural aggregates with recycled aggregates. | [63] |

| 42 | Global warming potential and cumulative energy demand. | - | [21] |

| 43 | CO2 emissions and total cost. | - | [64] |

| 44 | Natural resources. | Replacement of 30% and 100% of natural aggregates with recycled concrete aggregate. | [5] |

| 45 | Global warming potential and cumulative energy demand. | - | [65] |

References

- George, T.E.; Karatu, K.; Edward, A. An evaluation of the environmental impact assessment practice in Uganda: Challenges and opportunities for achieving sustainable development. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.K. Environmental impact assessment: The state of the art. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2012, 30, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBoer, B.; Nguyen, N.; Diba, F.; Hosseini, A. Additive, subtractive, and formative manufacturing of metal components: A life cycle assessment comparison. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 115, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.P.; Callejas, I.J.A.; Durante, L.C. Blocos de concretos fabricados com incorporação de resíduos sólidos: Uma revisão sistemática. E&S Eng. Sci. 2020, 9, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengfeng, Z.; Courard, L.; Groslambert, S.; Jehin, T.; Léonard, A.; Jianzhuang, X. Use of recycled concrete aggregates from precast block for the production of new building blocks: An industrial scale study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 157, 104786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, G.; Marrocchino, E.; Tassinari, R.; Vaccaro, C. Recycling of construction and demolition waste materials: A chemical–mineralogical appraisal. Waste Manag. 2005, 25, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, C.R.B.; Zoldan, M.A.; Leite, M.L.G.; Oliveira, I.L. Sistemas Computacionais de Apoio a Ferramenta Análise de Ciclo de Vida do Produto (ACV). In Proceedings of the Enegep, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 13–16 October 2008; ABEPRO: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2008; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J.V.; Esteves, B.; Cruz-Lopes, L.; Domingos, I. Life cycle assessment—Historical review and future perspective. Millenium J. Educ. Technol. Health 2020, 6, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Pinzon, C.; Pravia, Z.M.C. Projetos desenvolvidos utilizando MEF e ACV na sustentabilidade de produtos: Uma revisão bibliométrica e sistemática da literatura. Contrib. Cienc. Soc. 2024, 17, 636–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Tu, A.; Chen, C.; Lehman, D.E. Mechanical properties, durability, and life-cycle assessment of concrete building blocks incorporating recycled concrete aggregates. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioriti, C.F.; Ino, A.; Akasaki, J.L. Avaliação de blocos de concreto para pavimentação intertravada com adição de resíduos de borracha provenientes da recauchutagem de pneus. Ambiente Constr. 2007, 7, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, H.; Kumar, R.; Mondal, P. Life cycle analysis of paver block production using waste plastics: Comparative assessment with concrete paver blocks. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402, 136857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresch, A.; Lacerda, D.P.; Antunes Júnior, J.A.V. Design Science Research: Método de Pesquisa para Avanço da Ciência e Tecnologia; Bookman: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2014; 204p. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Rev. Esp. Nutr. Hum. Diet. 2014, 18, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABNT—Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas. NBR 9781:2013—Peças de Concreto para Pavimentação—Especificação e Métodos de Ensaio, 2nd ed.; ABNT: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ABNT—Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas. NBR ISO 14040:2014—Gestão Ambiental—Avaliação do Ciclo de Vida—Princípios e Estrutura, 2nd ed.; ABNT: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- ABNT—Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas. NBR ISO 14044:2014—Gestão Ambiental—Avaliação do Ciclo de Vida—Requisitos e Orientações, 2nd ed.; ABNT: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A. How do scholars approach the circular economy? A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki-Suzuki, C.; Nishiyama, T.; Kato, M.; Lavtizar, V. Policies and Practice of Sound Material-Cycle Society in Japan: Transition Towards the Circular Economy; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 37–66. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, N.B.R.; Neto, J.M.M.; Da Silva, E.A. Environmental assessment in concrete industries. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 327, 129516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hu, M.; Dong, L.; Gebremariam, A.; Miranda-Xicotencatl, B.; Di Maio, F.; Tukker, A. Eco-efficiency assessment of technological innovations in high-grade concrete recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.; Ouni, M.H.E.; Kurda, R. Life cycle assessment (LCA) of precast concrete blocks utilizing ground granulated blast furnace slag. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 83580–83595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassiani, J.; Martinez-Arguelles, G.; Penabaena-Niebles, R.; Keßler, S.; Dugarte, M. Sustainable concrete formulations to mitigate Alkali-Silica reaction in recycled concrete aggregates (RCA) for concrete infrastructure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 307, 124919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, R. Estudo Aplicado da Solução de Projeto de Pavimentação para Pátio de Estacionamento de Ônibus. Undergraduate Thesis, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC), Joinville, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, C.R. Estudo da Utilização de Rejeitos de Carvão Mineral na Fabricação de Blocos de Concreto para Pavimentação em Substituição ao Agregado Miúdo Natural. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul—UFRGS, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, A.K. Influência do Resíduo de PVC Moído como Substituto Parcial do Agregado Miúdo no Concreto Dosado para Peças de Pavimento Intertravado. Master’s Thesis, Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina—UDESC, Florianopolis, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Adiguzel, D.; Tuylu, S.; Eker, H. Utilization of tailings in concrete products: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 360, 129574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, O.; Ahmad, S.; Adekunle, S.K. Carbon dioxide sequestration in cementitious materials: A review of techniques, material performance, and environmental impact. J. CO2 Util. 2024, 83, 102812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhawaldeh, A.A.; Judah, H.I.; Shammout, D.Z.; Almomani, O.A.; Alkhawaldeh, M.A. Sustainability evaluation and life cycle assessment of concretes including pozzolanic by-products and alkali-activated binders. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, E.K.; Liapis, A.; Papayianni, I. Comparative life cycle assessment of concrete road pavements using industrial by-products as alternative materials. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 101, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavaraj, A.S.; Gettu, R. Life cycle assessment as a tool in sustainability assessment of concrete systems: Why and how. Indian Concr. J. 2022, 96, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, W.K.; Alhorr, Y.; Lawania, K.K.; Sarker, P.K.; Elsarrag, E. Life cycle assessment for environmental product declaration of concrete in the Gulf States. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 35, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysostomou, C.; Kylili, A.; Nicolaides, D.; Fokaides, P.A. Life Cycle Assessment of concrete manufacturing in small isolated states: The case of Cyprus. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2017, 36, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colangelo, F.; Petrillo, A.; Cioffi, R.; Borrelli, C.; Forcina, A. Life cycle assessment of recycled concretes: A case study in southern Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 1506–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collivignarelli, M.C.; Abba, A.; Miino, M.C.; Cillari, G.; Ricciardi, P. A review on alternative binders, admixtures and water for the production of sustainable concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordoba, G.; Paulo, C.I.; Irassar, E.F. Towards an eco-efficient ready mix-concrete industry: Advances and opportunities. A study of the Metropolitan Region of Buenos Aires. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 63, 105449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, O.; Eslami, A.; Mahdavipour, M.A.; Mostofinejad, D.; Ghorbani Mooselu, M.; Pilakoutas, K. Ceramic waste powder as a cement replacement in concrete paving blocks: Mechanical properties and environmental assessment. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2024, 25, 2370563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etcheverry, J.M.; Laveglia, A.; Villagran-Zaccardi, Y.A.; De Belie, N. A technical-environmental comparison of hybrid and blended slag cement-based recycled aggregate concrete tailored for optimal field performance. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 17, 100370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, A.; Soriano, L.; Tashima, M.M.; Monzó, J.; Borrachero, M.V.; Payá, J. One-part eco-cellular concrete for the precast industry: Functional features and life cycle assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 269, 122203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Li, J.; Nishiwaki, T.; Ding, Y.; Wang, J.X. Structural implementation of recycled lump prepared from waste concrete after elevated temperatures: Mechanical and environmental performances. Structures 2024, 67, 106970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giama, E.; Papadopoulos, A.M. Assessment tools for the environmental evaluation of concrete, plaster and brick elements production. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 99, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, P.G.; Maghfouri, M.; Onn, C.C.; Loo, S.C. Life cycle assessment on recycled e-waste concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, R.; Silvestre, J.D.; De Brito, J. Environmental life cycle assessment of the manufacture of EPS granulates, lightweight concrete with EPS and high-density EPS boards. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 28, 101031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravina, R.J.; Xie, T.; Bennett, B.; Visintin, P. HDPE and PET as Aggregate Replacement in Concrete: Life-cycle assessment, Material Development and a case study. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 103329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursel, A.P.; Maryman, H.; Ostertag, C. A life-cycle approach to environmental, mechanical, and durability properties of “green” concrete mixes with rice husk ash. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursel, A.P.; Ostertag, C.P. Impact of Singapore’s importers on life-cycle assessment of concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 118, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.U.; Poon, C.S.; Lo, I.M.; Cheng, J.C. Evaluation of environmental friendliness of concrete paving eco-blocks using LCA approach. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, S.-M.; Wu, B.; Hu, N. Environmental impacts of three waste concrete recycling strategies for prefabricated components through comparative life cycle assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 328, 129463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Roh, S. The Embodied Life Cycle Global Warming Potential of Off-Site Prefabricated Concrete Products: Precast Concrete and Concrete Pile Production in Korea. Buildings 2023, 13, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleijer, A.L.; Lasvaux, S.; Citherlet, S.; Viviani, M. Product-specific Life Cycle Assessment of ready mix concrete: Comparison between a recycled and an ordinary concrete. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 122, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artelt, C.; Lukas, P. Sustainable product portfolio evaluation methodology for sustainability reporting in the cement and concrete industry. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 9, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Liu, S.; Hu, Y.; Hu, D.; Kow, K.W.; Pang, C.; Li, B. Sustainable reuse of excavated soil and recycled concrete aggregate in manufacturing concrete blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 342, 127917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Juez, J.; Vegas, I.J.; Gebremariam, A.T.; García-Cortés, V.; Di Maio, F. Treatment of end-of-life concrete in an innovative heating-air classification system for circular cement-based products. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naran, J.M.; Gonzalez, R.E.G.; del Rey Castillo, E.; Toma, C.L.; Almesfer, N.; van Vreden, P.; Saggi, O. Incorporating waste to develop environmentally-friendly concrete mixes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 314, 125599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrillo, A.; Cioffi, R.; De Felice, F.; Colangelo, F.; Borrelli, C. An environmental evaluation: A comparison between geopolymer and OPC concrete paving blocks manufacturing process in Italy. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2016, 35, 1699–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salesa, Á.; Pérez-Benedicto, J.Á.; Esteban, L.M.; Vicente-Vas, R.; Orna-Carmona, M. Physico-mechanical properties of multi-recycled self-compacting concrete prepared with precast concrete rejects. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 153, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, M.; Kim, R.; Hong, S.; Lee, S.; Roh, S. Development of a carbon emission evaluation system for precast concrete products in South Korea. Int. J. Sustain. Build. Technol. Urban Dev. 2023, 14, 543–551. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, B.; Wu, H.; Wu, Y.-F. Evaluation of the carbon reduction benefits of adopting the compression cast technology in concrete components production based on LCA. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 208, 107733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, E.R.; Mateus, R.; Camões, A.F.; Bragança, L.; Branco, F.G. Comparative environmental life-cycle analysis of concretes using biomass and coal fly ashes as partial cement replacement material. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2221–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visintin, P.; Xie, T.; Bennett, B. A large-scale life-cycle assessment of recycled aggregate concrete: The influence of functional unit, emissions allocation and carbon dioxide uptake. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Tam, V.W.; Le, K.N.; Butera, A.; Hao, J.L.; Wang, J. Effects of mix design and functional unit on life cycle assessment of recycled aggregate concrete: Evidence from CO2 concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 348, 128712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Tam, V.W.; Le, K.N.; Hao, J.L.; Wang, J. Life cycle assessment of sustainable concrete with recycled aggregate and supplementary cementitious materials. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 193, 106947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Xie, T.; Wang, X. Eco-, economic- and mechanical-efficiencies of using precast rejects as coarse aggregates in self-compacting concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hu, M.; Yang, X.; Amati, A.; Tukker, A. Life cycle greenhouse gas emission and cost analysis of prefabricated concrete building façade elements. J. Ind. Ecol. 2020, 24, 1016–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulcão, R.; Calmon, J.L.; Rebello, T.A.; Vieira, D.R. Life cycle assessment of the ornamental stone processing waste use in cement-based building materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 257, 119523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Keyword/Terms | Boolean Operator | Keyword/Terms |

|---|---|---|

| “Life cycle assessment” or “Life cycle analysis” or “LCA” | AND | Paver” or “Paver concrete” or “Paver blocks” or “Paver blocks concrete” or “Precast blocks” or “precast blocks concrete” or “Pavement blocks” or “Concrete paving blocks” |

| Environmental Impact Indicators | No. of Papers |

|---|---|

| Global warming potential | 34 |

| Accumulated energy consumption | 19 |

| CO2 Emissions | 12 |

| Acidification potential | 10 |

| Eutrophication potential | 8 |

| Greenhouse gas emissions | 4 |

| Ozone depletion potential | 3 |

| Total cost | 2 |

| Abiotic depletion potential | 2 |

| Ecotoxicity | 2 |

| Natural resources | 2 |

| Abiotic resource depletion | 1 |

| C2H4 Emissions | 1 |

| Air pollutants such as CO2, NOx, and SO2 | 1 |

| Water depletion | 1 |

| pH Analysis | 1 |

| Mixture Identification | Cement (kg) | Medium Sand (kg) | Fine Sand (kg) | Gravel (kg) | Total Aggregate (kg) | w/c Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [24] | 1 | 2.27 | 1.27 | 0.91 | 4.45 | 0.31 |

| [25] | 1 | 1.71 | 0.93 | 1.17 | 3.81 | 0.35 |

| [26] | 1 | 1.39 | 1.05 | 1.18 | - | 0.35 |

| Mixture Identification | Mixture | Waste (kg) | Cement (kg) | Sand (kg) | Gravel (kg) | Water (kg) | W/C Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [11] | A 0% | 0 | 346.61 | 1307.41 | 605.12 | 153.37 | 0.44 |

| B 8% | 48.83 | 323.06 | 1090.44 | 619.80 | 129.22 | 0.40 | |

| C 10% | 65.18 | 323.03 | 1247.64 | 573.39 | 129.22 | 0.40 | |

| D 12% | 74.67 | 323.06 | 1140.22 | 518.79 | 129.22 | 0.40 |

| Mixture Identification | Mixture | Cement (kg) | Sand (kg) | Gravel (kg) | Plastic (kg) | Water (kg) | Energy (MJ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [12] | Conventional | 15.42 | 30.78 | 61.8 | 0 | 45.6 | 2.4 |

| Plastic as aggregate | 21 | 53.76 | 47.88 | 20.52 | 10.5 | 2.1 | |

| Plastic binder | 0 | 67.5 | 0 | 22.5 | 20 | 2.9 |

| Mixture Identification | Mixture | Cement (kg) | GGBS (kg) | Sand (kg) | Gravel (kg) | Water (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [22] | Control | 351 | 0 | 705 | 1410 | 106 |

| A 5% | 333.5 | 17.6 | 705 | 1410 | 106 | |

| B 10% | 315.9 | 35.1 | 705 | 1410 | 106 | |

| C 15% | 298.4 | 52.7 | 705 | 1410 | 106 | |

| D 20% | 280.8 | 70.2 | 705 | 1410 | 106 | |

| E 25% | 263.3 | 87.8 | 705 | 1410 | 106 | |

| F 30% | 245.7 | 105.3 | 705 | 1410 | 106 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soares, V.A.; Effting, C.; Leite, L.R.; Schackow, A. Systematic Literature Review: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Paving Blocks. Buildings 2025, 15, 4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244471

Soares VA, Effting C, Leite LR, Schackow A. Systematic Literature Review: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Paving Blocks. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244471

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoares, Vitoria Alves, Carmeane Effting, Luciana Rosa Leite, and Adilson Schackow. 2025. "Systematic Literature Review: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Paving Blocks" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244471

APA StyleSoares, V. A., Effting, C., Leite, L. R., & Schackow, A. (2025). Systematic Literature Review: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Paving Blocks. Buildings, 15(24), 4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244471