Abstract

This study presents a novel hybrid deep learning framework integrating Feature Tokenizer-Transformer (FT-Transformer) with Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron (Masked MLP) for predicting the compressive strength of recycled aggregate self-compacting concrete (RASCC). The framework addresses incomplete data challenges through a missingness-aware fusion strategy and two-stage stacking scheme with Ridge regression. Using a dataset of 289 experimental records with 18 input parameters, the hybrid model achieved robust predictive performance with enhanced generalization stability (Test R2 = 0.940, RMSE = 4.219 MPa) while demonstrating consistent predictions under data missingness conditions up to 25%. SHAP analysis revealed that cement content, water-to-binder ratio, and curing age are the dominant factors influencing RASCC strength. The proposed uncertainty quantification via split conformal prediction provides 90% coverage with average interval width of 8.32 MPa, enabling practical engineering applications with quantified reliability.

1. Introduction

The construction industry faces mounting pressure to reduce its environmental footprint, as concrete production alone accounts for approximately 8% of global anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions [1]. Recycled aggregate concrete has emerged as an environmentally friendly construction material derived from reclaimed concrete components, offering a promising pathway toward sustainable infrastructure development by reducing both the demand for natural aggregates and the environmental pollution caused by construction waste [2,3]. Self-compacting concrete represents an advanced construction material particularly suited for complex formwork and reinforcement configurations where traditional vibrational methods face limitations, and when combined with recycled aggregates, recycled aggregate self-compacting concrete offers dual benefits of enhanced workability and environmental sustainability [4,5]. The incorporation of supplementary cementitious materials such as fly ash, ground granulated blast furnace slag, and silica fume alongside recycled aggregates has been widely investigated to develop green and low-carbon concrete alternatives, though the complex interaction mechanisms among these multiple components present significant challenges for traditional empirical design approaches [6,7,8]. Recent studies further highlighted that replacing conventional silica fume with natural pozzolans can significantly enhance durability while reducing the carbon footprint of high-performance concrete mixtures. Hosseinzadehfard and Mobaraki [9] demonstrated that natural pozzolan can partially substitute microsilica without compromising corrosion resistance, while maintaining comparable strain behavior in reinforced concrete beams exposed to chloride-induced corrosion.

Traditional methods for evaluating the mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete with supplementary cementitious materials rely heavily on numerous experimental tests to establish empirical statistical models, which are material-consuming, time-consuming, and labor-intensive [10,11]. These practical constraints create a fundamental bottleneck in the development and optimization of sustainable concrete mixtures, limiting the pace at which innovative formulations can be validated and deployed in construction practice.

Artificial intelligence techniques have demonstrated transformative potential in addressing these challenges by leveraging historical data for effective predictive analysis across diverse engineering domains, including concrete strength prediction [12,13,14]. With studies demonstrating that extreme gradient boosting, artificial neural networks, and optimization algorithms such as particle swarm optimization and sparrow search algorithm have been widely adopted in civil engineering to address complex challenges and improve the accuracy of important parameter predictions [15,16,17,18]. Notably, Geng developed a sophisticated hybrid artificial intelligence model combining Elastic Net, Random Forest, and Light Gradient Boosting Machine algorithms for predicting recycled concrete compressive strength, achieving an R2 value of 0.9072 and demonstrating a 312% improvement over traditional linear methods through the implementation of Gaussian noise augmentation during training [19]. The integration of machine learning models such as Random Forest, Gradient Boosting Machines, and Deep Neural Networks has enabled researchers to predict not only compressive strength but also durability metrics while optimizing mix designs for sustainability, achieving significant improvements in both mechanical performance and environmental impact reduction [20,21,22]. Recent advances in sustainable concrete and recycled aggregate systems further highlight the importance of integrating SCMs, recycled aggregates, and intelligent optimization techniques. Wu et al. [23] compared the performance of ordinary and recycled aggregate concrete incorporating CFA, identifying optimal CFA levels for balancing strength, shrinkage, carbonation, cost, and carbon emissions. Wang et al. [24] optimized UHPC matrix design using simplex centroid design, demonstrating significant improvements in strength, durability, and flowability. Lin et al. [25] proposed a smart machine-learning-based optimization framework for recycled rubber aggregate concrete, enabling accurate prediction of mechanical properties and substantial reductions in carbon emissions. Gou et al. [26] applied multiple machine learning techniques to predict the compressive strength of SCC incorporating SCMs and RCA, demonstrating that GEP provides superior accuracy and stability. These studies demonstrate the growing trend of integrating recycled materials, SCMs, and machine learning for sustainable concrete design, further supporting the motivation for the present work.

For self-compacting concrete specifically, machine learning and deep learning techniques offer promising solutions to predict the complex behavior of sustainable concrete materials incorporating diverse ingredients like fly ash, silica fumes, and recycled aggregates, with recent systematic reviews demonstrating that advanced architectures including transformer-based models and ensemble methods achieve superior predictive accuracy [27,28,29]. Recent research has successfully employed machine learning technologies combined with multi-objective optimization algorithms to obtain Pareto fronts for mixture optimization problems, effectively guiding the optimization of recycled aggregate concrete preparation while balancing strength requirements, cost considerations, and environmental impacts [30,31]. These optimization frameworks represent a significant advancement beyond pure prediction, enabling automated mixture design that simultaneously addresses multiple competing objectives relevant to sustainable construction practice.

The application of deep learning architectures has further expanded the frontiers of concrete property prediction, with researchers exploring transformer-based models for their ability to capture long-range dependencies and complex patterns in concrete mix design data [32,33]. Recent work on microstructure-informed deep learning has shown that incorporating visual data from backscattered electron images alongside traditional mix proportion data can dramatically improve prediction accuracy, with Swin Transformer models achieving over 95% accuracy in compressive strength prediction, representing a paradigm shift from purely data-driven to multi-modal learning. In parallel, the field has witnessed growing recognition of uncertainty quantification as a critical component of reliable predictive modeling, with conformal prediction providing distribution-free uncertainty quantification with finite-sample coverage guarantees, addressing a long-standing limitation of traditional machine learning approaches that produce only point predictions without reliability indicators [34,35]. The integration of Monte Carlo Dropout for uncertainty estimation in deep neural networks has also shown promise in concrete applications, with this Bayesian approximation technique enabling efficient uncertainty quantification by treating dropout as approximate Bayesian inference, providing a practical alternative to ensemble methods for capturing model uncertainty [36]. When combined with robust prediction architectures, Monte Carlo Dropout facilitates reliable strength predictions even under conditions of incomplete or noisy input data, which frequently occur in practical construction scenarios, with recent studies demonstrating its effectiveness across various concrete types including recycled aggregate concrete and self-compacting concrete [37,38].

Despite these advances, several fundamental challenges remain unresolved in applying artificial intelligence to recycled aggregate self-compacting concrete. The inherent variability in recycled aggregate quality, stemming from differences in parent concrete strength, crushing methods, and contamination levels, introduces substantial uncertainty into predictive modeling, with the complex interactions among multiple supplementary cementitious materials and the influence of missing data on predictive accuracy requiring more robust and adaptive modeling approaches [39,40]. Current models often treat all data points uniformly without accounting for varying degrees of data completeness or feature missingness that commonly occur in practical datasets compiled from diverse literature sources. This limitation is particularly problematic for recycled aggregate concrete applications where material characterization may be incomplete due to resource constraints or inconsistent reporting standards across different studies and construction sites. The development of interpretable machine learning models has emerged as another critical research direction, as while black-box models may achieve high predictive accuracy, their lack of transparency limits adoption in engineering practice where understanding causal relationships is essential for mix design optimization [41,42]. SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis has become a standard tool for model interpretability, enabling researchers to quantify the contribution of each input feature to predictions and validate that model decisions align with domain knowledge, with recent applications in concrete science revealing that water-cement ratio, curing age, and cement content consistently emerge as the most influential parameters for compressive strength prediction, corroborating decades of empirical knowledge while uncovering more nuanced interaction effects.

The construction industry’s transition toward data-driven design methodologies has been further accelerated by advances in computational infrastructure and the proliferation of open-source machine learning frameworks, though the translation of laboratory-validated models to field applications remains challenging due to differences in environmental conditions, material variability, and construction practices, underscoring the need for models that not only achieve high accuracy but also demonstrate robustness across varying operational conditions [43,44]. This implementation gap between research and practice represents a critical barrier to widespread adoption of artificial intelligence in concrete technology, as practitioners require not only accurate predictions but also confidence measures that enable risk-informed decision-making in production environments.

To address the limitations of existing predictive models for recycled aggregate self-compacting concrete (RASCC), the main objective of this study is to develop a robust and missingness-aware hybrid deep-learning framework capable of accurately predicting RASCC compressive strength while providing reliable uncertainty quantification. The novelty of this work lies in (i) integrating FT-Transformer and Masked-MLP to simultaneously capture global feature interactions and missing-data patterns; (ii) introducing a missing-rate–adaptive fusion mechanism that dynamically balances model contributions based on data completeness; (iii) implementing a two-layer stacking strategy to enhance generalization; and (iv) incorporating split-conformal prediction to deliver distribution-free confidence intervals for engineering decision-making. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the dataset and modeling methodology, Section 3 presents the predictive performance and interpretability results, Section 4 discusses the implications and limitations, and Section 5 concludes the study.

To address the limitations of existing predictive models for recycled aggregate self-compacting concrete (RASCC), the main objective of this study is to develop a robust and missingness-aware hybrid deep-learning framework capable of accurately predicting RASCC compressive strength while providing reliable uncertainty quantification. Although the dataset comprises 289 experimental records, which falls below the typical threshold sample size(N) > 1000 often recommended for deep learning applications, we deliberately selected deep architectures over conventional tree-based methods (e.g., XGBoost 2.0.3, LightGBM 4.3.0, Random Forest as implemented in scikit-learn 1.3.2.) for three reasons: (1) the explicit missingness encoding capability of the Masked-MLP architecture, which tree-based models lack; (2) the attention mechanism in FT-Transformer for capturing complex feature interactions relevant to multi-component concrete mixtures; and (3) the integration of Monte Carlo Dropout for principled uncertainty quantification. To ensure fair evaluation, comprehensive comparisons with gradient boosting and ensemble tree baselines are provided in Section 3.3, demonstrating that the proposed framework achieves superior robustness under incomplete data conditions despite comparable performance on complete data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Description and Availability

The dataset employed in this investigation was obtained from the open-access publication by Yang et al. [45], comprising 289 experimental records with 18 input features characterizing mixture proportions, material compositions, and testing conditions of recycled aggregate self-compacting concrete.

Descriptive statistical analysis reveals substantial variability in the quantitative parameters, as presented in Table 1. The compressive strength exhibits a mean value of 46.28 MPa with a standard deviation of 16.62 MPa, reflecting the wide spectrum of strength levels resulting from diverse mixed designs and material properties. The water-to-binder ratio spans from 0.24 to 0.56, while the recycled aggregate replacement ratio ranges from 0 to 100 percent, encompassing mixtures with exclusively natural aggregates through fully recycled configurations. Several parameters display distinct distribution characteristics warranting consideration during model development. The curing age demonstrates right-skewed distribution with skewness of 1.31, indicating predominance of short-term test data at 14 to 28 days. Supplementary cementitious materials including fly ash and ground granulated blast-furnace slag exhibit elevated skewness and kurtosis values, signifying irregular utilization patterns across different mixture formulations. In contrast, the densities of natural and recycled aggregates show nearly symmetric distributions, implying consistent measurement quality across contributing studies. The water and sand contents exhibit moderate variability aligned with typical mix design practices in structural concrete production. This comprehensive parameter coverage provides a robust foundation for training and evaluating machine learning models capable of generalizing across diverse recycled aggregate concrete compositions.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of test database.

2.2. Correlation Analysis and Feature Relationships

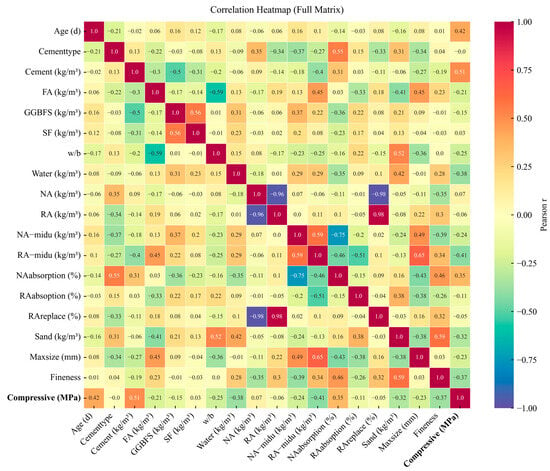

Prior to model development, comprehensive correlation analysis was conducted to identify underlying relationships among mixture parameters and compressive strength. Figure 1 presents a Pearson correlation heatmap quantifying linear associations among all variables in the dataset. The analysis reveals several theoretically consistent patterns that inform subsequent feature engineering decisions. Compressive strength correlates positively with cement content (r ≈ 0.50) and curing age (r ≈ 0.42), reinforcing that increased binder dosage and extended hydration duration enhance structural development in recycled aggregate concrete [46]. Conversely, water-to-binder ratio and water content demonstrate clear negative correlations with coefficients of approximately −0.25 and −0.38, respectively, aligning with classical concrete theory wherein elevated porosity from excess water reduces strength [47,48]. The strong inverse correlation observed between natural and recycled aggregate fractions (r ≈ −0.98) reflects the dataset’s comprehensive coverage of substitution levels ranging from fully natural to fully recycled aggregate configurations.

Figure 1.

Correlation heatmap among all quantitative variables of the RASCC dataset.

In addition to these primary correlations, Figure 1 also highlights the moderate but meaningful influences of recycled aggregate density, absorption, and sand content, which exhibit noticeable interactions with strength and other mixture parameters. These interdependencies indicate that the aggregate quality and mixture packing characteristics contribute indirectly to mechanical performance, underscoring the need for models capable of capturing coupled effects rather than relying solely on individual variable trends. Overall, the correlation map provides the foundational understanding required for subsequent model design, confirming that binder composition, water ratio, and aggregate characteristics form a tightly coupled system governing RASCC mechanical performance.

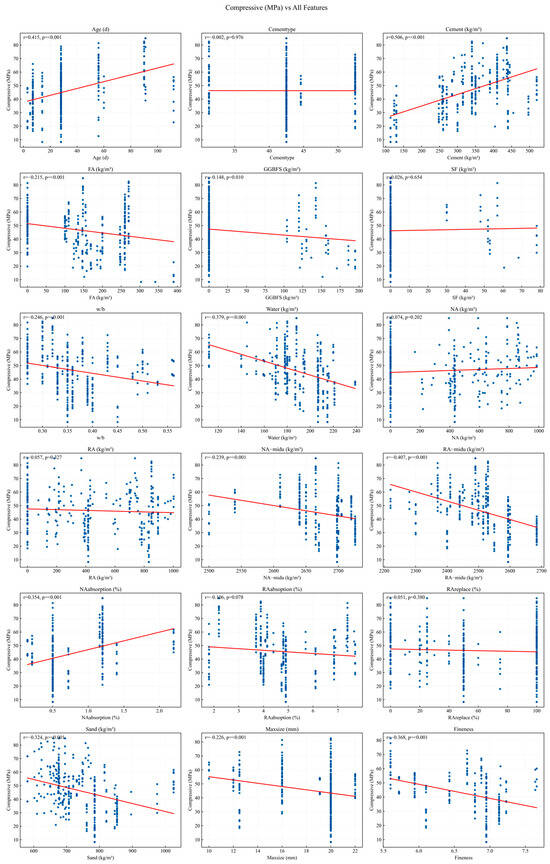

Figure 2 supplements the correlation analysis by providing scatter plots that visualize the relationships between compressive strength and key mixture parameters. The plots confirm the trends identified in the correlation heatmap, showing increased strength with higher cement content and longer curing age, and reduced strength with higher water content and fineness. The weak or slightly negative effects of supplementary cementitious materials such as fly ash and ground granulated blast-furnace slag are consistent with previous findings that their influence depends on replacement level, curing conditions, and interactions with aggregate quality [49]. The noticeable dispersion in recycled aggregate absorption and replacement ratio further reflects the inherent variability of recycled aggregates, where factors such as adhered mortar and porosity affect performance [50]. Overall, these visualizations assist in validating the key feature relationships used in the predictive modeling framework.

Figure 2.

Scatter plots showing the relationships between compressive strength and key mixture parameters. Red solid lines represent LOESS smoothed trend lines indicating the general relationship between each mixture parameter and compressive strength.

2.3. Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

In this study, the robustness evaluation relies on a Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) mechanism to simulate varying degrees of information loss. While real-world engineering data often exhibit systematic missingness (MNAR), the proposed Masked-MLP architecture is designed to be agnostic to the missingness mechanism.

The prediction of compressive strength in recycled aggregate self-compacting concrete necessitates systematic preprocessing to address missing data patterns, ensure numerical stability during optimization, and generate representations suitable for diverse model architectures. The preprocessing pipeline implements several sequential transformations applied consistently across training and testing partitions.

The target variable and numerical features were standardized using Z-score normalization based on training set statistics. Missing values in numerical features were imputed using the median value of the training set before standardization. To explicitly encode data quality, a binary mask matrix was generated, and the row-level missing rate was calculated for each sample.

Missing data patterns are explicitly characterized through computation of row-level missing rates, which subsequently inform the adaptive ensemble weighting mechanism. For sample ii i with feature vector , where F denotes the total number of features, the missing rate is computed as

where represents the indicator function returning unity when the condition is satisfied and zero otherwise. A binary missing mask matrix is constructed, where if feature j in sample I contains missing data and otherwise. This explicit encoding enables the Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron architecture to learn representations that account for data quality variations.

2.4. Model Architecture Design

2.4.1. Feature Tokenizer-Transformer Architecture

The Feature Tokenizer-Transformer adapts the transformer architecture for tabular data [51,52]. Numerical features are first transformed into embeddings. These tokens are then processed through a sequence of Transformer encoder layers employing Multi-Head Self-Attention and Feed-Forward Networks with GELU activation and Layer Normalization [53]. The final representation is flattened and passed through a Multi-Layer Perceptron regression head to predict compressive strength.

2.4.2. Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron with Monte Carlo Dropout

The Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron explicitly incorporates missing data patterns [54] by operating on augmented feature representations that concatenate standardized values with binary missing indicators and row-level missing rates. This architecture demonstrates robust performance under high-missingness conditions where the Feature Tokenizer-Transformer may struggle with attention mechanisms influenced by numerous imputed values.

The Masked MLP processes the augmented feature vector (features concatenated with missingness mask). Monte Carlo (MC) Dropout [36] is implemented after the hidden layers, remaining active during inference to generate stochastic predictions, from which the predictive mean and variance are derived.

2.5. Model Training Procedures

Models were trained using the Adam optimizer with L2 regularization to prevent overfitting [55]. A Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss function was employed, and a cosine annealing learning rate scheduler [56] was applied to facilitate convergence.

2.6. Ensemble Strategies

2.6.1. Missing Rate-Aware Adaptive Weighting

Different model architectures exhibit varying robustness to missing data patterns, with the Feature Tokenizer-Transformer performing optimally on low-missing-rate samples through its attention mechanisms, while the Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron excels with high missing rates due to explicit missingness encoding. The framework employs adaptive weighting using sigmoid functions to dynamically adjust model contributions based on sample-specific missing rates. The weight assigned to the Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron is computed as

The complementary weight for the FT-Transformer is determined as follows:

where τ determines the transition point between models and β controls the sharpness of the transition. The adaptive ensemble prediction leverages the complementary strengths of both architectures:

2.6.2. Two-Layer Out-of-Fold Stacking

Stacking [57,58] learns to optimally combine base model predictions through a meta-model trained on out-of-fold predictions. The training set is partitioned into K folds such that . For each fold k, both base models are trained on and generate predictions on the held-out fold . This cross-validation procedure ensures that predictions for each sample originate from models that did not observe that sample during training, thereby preventing information leakage. The out-of-fold predictions form the meta-feature matrix:

where represents the meta-features for sample i, denotes the weight vector, and controls the regularization strength. To obtain unbiased training set performance estimates, another layer of K-fold cross-validation is performed on the meta-features. The final stacked prediction for test samples represents an ensemble of meta-models trained in the nested cross-validation procedure:

The meta-model employs Ridge regression [59] with L2 regularization to learn optimal combination weights. The meta-model objective function is

To combine the strengths of both adaptive weighting and stacking strategies, we propose a hybrid ensemble that equally weights predictions from both approaches:

This design leverages the sample-specific adaptivity of the weighting strategy alongside the learned optimal combination from the stacking approach. This static equal-weighting strategy was deliberately selected over a learned combination (e.g., a third-level meta-learner) to prevent overfitting, considering the limited dataset size(N) = 289. Since the Stacking branch optimizes global error via Ridge regression and the Adaptive branch handles local missingness dynamics via the gating mechanism, the two branches offer structurally distinct “views” of the data. Averaging them acts as a parsimonious regularization technique, reducing prediction variance by balancing the global and local optimization objectives without introducing additional learnable parameters.

2.7. Conformal Prediction for Uncertainty Quantification

Conformal prediction [60,61] provides distribution-free, finite-sample valid prediction intervals without requiring distributional assumptions about the underlying data generation process. The split conformal method divides training data into a proper training set for model fitting and a calibration set for interval construction. After training the final ensemble model on the training set, nonconformity scores are computed as absolute residuals on the calibration set:

Given the desired miscoverage rate α, the quantile with finite-sample correction is computed as:

where represents the calibration set size and denotes the ceiling function. For test samples with prediction , the prediction interval is constructed as

This construction achieves marginal coverage guarantees that hold regardless of the underlying data distribution:

For adaptive intervals conditioned on missing rates, we model the relationship between nonconformity scores and missing rates using linear regression:

Parameters are estimated via least squares with non-negativity constraints to ensure positive interval widths. Normalized residuals are computed by dividing absolute residuals by their expected values under the linear model:

The quantile on normalized scores determines the normalized interval radius:

For test samples with missing rate , the adaptive prediction interval radius scales with the sample-specific missing rate:

This conditioning approach produces narrower intervals for low-missing-rate samples and wider intervals for high-missing-rate samples, providing more informative uncertainty estimates that reflect data quality variations.

2.8. Model Evaluation Metrics

Model performance was assessed using four standard regression metrics: Coefficient of Determination (R2), Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). These metrics were computed in the de-standardized space to ensure interpretability.

This metric treats all errors linearly without additional penalty for large deviations, making it more robust to outliers compared to squared error metrics. The comparison between Root Mean Squared Error and Mean Absolute Error reveals model sensitivity to outliers, with substantial discrepancies indicating the presence of large prediction errors that disproportionately affect squared error metrics.

2.9. Implementation Details and Computational Environment

All models were implemented in PyTorch 2.1.2 [62] with automatic mixed precision training capability when graphics processing unit acceleration was available. The Feature Tokenizer-Transformer architecture employed 32-dimensional embeddings, 4 attention heads, and 2 transformer layers. The Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron utilized two hidden layers with 256 units each. Dropout probability [63] was set to 0.2 for both architectures to provide regularization while maintaining sufficient model capacity. Training employed the AdamW optimizer with initial learning rate of 10−3 and weight decay of 10−4.

Given the relatively modest dataset size of 289 samples, several strategies were implemented to ensure training stability and prevent overfitting in the deep learning architectures. First, aggressive regularization was applied through dropout (p = 0.2), weight decay (λ = 10−4), and early stopping with patience of 60 epochs. Second, the FT-Transformer employed a compact configuration with only 32-dimensional embeddings, 4 attention heads, and 2 transformer layers, substantially smaller than typical transformer architectures used in large-scale applications. Third, multi-seed bagging with 3 random initializations was used to reduce prediction variance. Fourth, the 8-fold cross-validation scheme for out-of-fold prediction generation maximized training data utilization while providing robust performance estimates. These design choices align with recent findings that appropriately regularized deep learning models can achieve competitive performance on small tabular datasets when architectural complexity is carefully controlled [64,65].

For the Feature Tokenizer-Transformer, multi-seed bagging with 3 different random initializations reduced prediction variance by averaging outputs from independently trained models. The Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron employed 8 Monte Carlo dropout passes at inference to generate uncertainty estimates. The K-fold cross-validation scheme used 8 folds for the first layer out-of-fold prediction generation and 5 folds for the second layer meta-model training. Given the limited dataset size 289 and the reliance of split conformal prediction on the calibration set size, the stability of the uncertainty quantification was rigorously evaluated. To mitigate the high variance inherent in small-sample quantile estimation, we performed the split conformal procedure over 50 random train-calibration-test splits. The reported coverage and interval width metrics represent the averaged performance across these repetitions, ensuring that the finite-sample guarantee holds robustly despite the fluctuations in individual calibration sets. The adaptive weighting mechanism employed a threshold parameter of 0.06 with sharpness parameter of 10, calibrated to achieve smooth transitions between model contributions as missing rates vary.

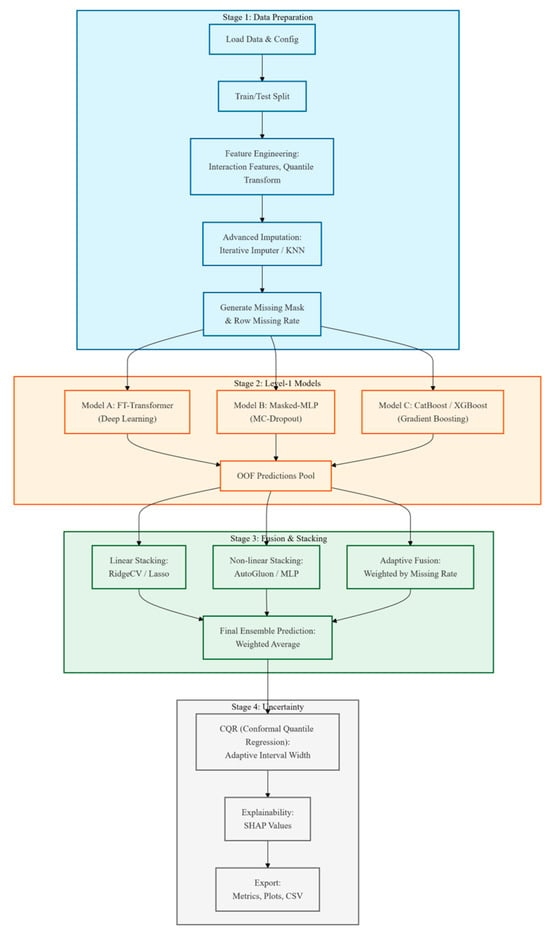

Figure 3 illustrates the comprehensive architecture of the proposed hybrid ensemble learning framework, depicting the multi-level prediction strategy with integrated uncertainty quantification. The pipeline initiates with data preparation modules that load configuration files and datasets, followed by train-test partitioning using an 80–20 split with random seed 42 for reproducibility. The preprocessing stage encompasses target variable standardization fitted exclusively on the training set, median imputation and standardization of numerical features, and generation of missing value masks to capture row-level missingness rates. The first-level deep modeling stage implements K-fold out-of-fold prediction, training two distinct deep learning architectures in parallel with the Feature Tokenizer-Transformer utilizing multi-seed bagging for enhanced robustness and the Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron employing Monte Carlo dropout for stochastic regularization. The second-level fusion and stacking stage constructs a dual-pathway adaptive ensemble mechanism, wherein one pathway employs Ridge regression to perform stacking on first-level out-of-fold predictions while the other pathway implements missingness-adaptive fusion that dynamically adjusts model contributions through logistic weighting based on sample-specific missing rates. The primary ensemble model synthesizes final predictions by averaging stacked and adaptive fusion outputs. The uncertainty quantification and export module applies split-conformal prediction methodology to construct prediction intervals supporting both plain and missingness-conditioned interval estimation strategies, subsequently exporting comprehensive analytical outputs including performance metrics, model configurations, prediction-versus-actual comparisons, and diagnostic visualizations.

Figure 3.

Architecture of the Proposed Hybrid Ensemble Learning Framework with Uncertainty Quantification.

2.10. Model Interpretability Analysis

Model interpretability analysis employs SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) methodology [66] to quantify feature importance and validate alignment with established concrete science principles. SHAP provides a theoretically grounded framework based on cooperative game theory, computing each feature’s contribution by systematically evaluating all possible feature combinations while satisfying fundamental attribution axioms including local accuracy, missingness, and consistency. The framework is derived from Shapley values in game theory [67], which offer the unique solution satisfying fairness properties for distributing payoffs among cooperative players.

For computational tractability with complex deep learning architectures, the implementation employs KernelExplainer [68], a model-agnostic sampling procedure that constructs weighted linear regression over feature coalitions where weights are specifically designed such that resulting feature attributions satisfy SHAP axioms in expectation. The analysis focuses on a stratified sample of 128 training instances selected to span the full range of compressive strengths from 5.36 to 89.0 MPa and missing rate patterns from 0 to 15 percent observed in the dataset. The background dataset is condensed to 80 representative instances through k-means clustering [69], reducing computational complexity while preserving essential statistical structure of the training distribution. The KernelExplainer employs 128 coalition samples per prediction, providing sufficient feature space coverage to yield stable SHAP estimates.

Global feature importance is quantified as the mean absolute SHAP value for each feature across all analyzed samples [70,71], representing the average magnitude of contribution that feature makes to prediction variance. To enable direct visual comparison across architectures despite differences in absolute SHAP scales, each model’s importance scores undergo min-max normalization to the zero-to-one range, with unity representing the most influential feature and zero representing the least influential feature for that specific model.

3. Results

3.1. Predictive Performance of Deep Learning Architectures

The comprehensive evaluation of five deep learning architectures revealed distinct performance characteristics across training and testing datasets, as summarized in Table 2 and Table 3. The Hybrid ensemble model demonstrated the most balanced and reliable performance with optimal consistency between training capability and generalization to unseen data. The model achieved a test coefficient of determination of 0.940, indicating that it explains 94.0 percent of the variance in concrete compressive strength, while maintaining a test root mean squared error of 4.219 MPa and mean absolute error of 3.231 MPa. The close alignment between training metrics (R2 = 0.910) and testing metrics (R2 = 0.940) suggests robust model generalization with minimal overfitting, a characteristic not observed in all component models.

Table 2.

Comparison of the performance of the models.

Table 3.

Experiment Configuration Summary.

The Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron achieved the highest individual test R2 of 0.942 among all models. However, the unusual pattern where test R2 (0.942) exceeds training R2 (0.906) raises concerns about potential test set bias or overfitting to specific data characteristics rather than true generalization capability. This inverted training-test relationship, contrary to typical machine learning behavior, suggests that the MaskedMLP may have coincidentally aligned well with the particular test partition rather than demonstrating superior inherent predictive power. The Stacking ensemble approach, which combines predictions from Feature Tokenizer-Transformer and Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron through Ridge regression meta-learning with fold-specific coefficients ranging from 0.356 to 0.527 for Feature Tokenizer-Transformer and 0.577 to 0.612 for Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron, yielded competitive results with a test coefficient of determination of 0.939 and root mean squared error of 4.245 MPa. The Adaptive Missing Fusion model, specifically designed to handle incomplete data with a missing rate threshold of 0.06, performed comparably to the Stacking approach with a test coefficient of determination of 0.939 and root mean squared error of 4.258 MPa, demonstrating its effectiveness in managing incomplete feature information. The standalone Feature Tokenizer-Transformer model, while showing reasonable performance, exhibited the highest prediction errors among all methods with a test root mean squared error of 5.128 MPa and mean absolute error of 4.010 MPa, suggesting that ensemble and hybrid approaches provide substantial improvements over single-model architectures.

The incorporation of conformal prediction in the Hybrid ensemble framework, with a conditioned quantile radius of 2.055 MPa at a 90 percent confidence level, further enhances the model’s utility by providing uncertainty quantification that scales with row-specific missing rates through linear parameters with intercept of 4.305 and slope approaching zero. These results demonstrate that hybrid deep learning methodologies effectively capture the complex nonlinear relationships between mix design parameters and compressive strength in recycled aggregate concrete, with the Hybrid ensemble offering the most reliable predictions for practical engineering applications.

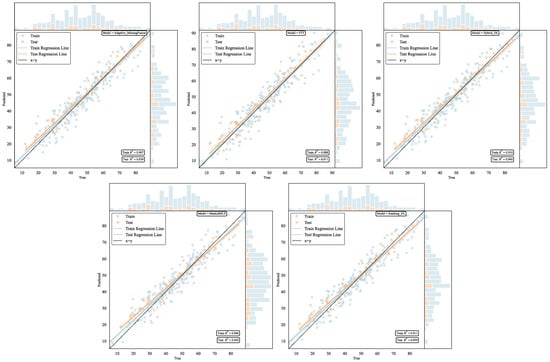

3.2. Regression Performance Visualization and Model Comparison

The regression analysis visualizations presented in Figure 4 provide essential insights into the predictive capabilities and generalization characteristics of the five deep learning architectures, enabling a technical dissection of model calibration, error structures, and distributional fidelity. Each subplot comprises a primary scatter plot of predicted versus true compressive strength values (in MPa), augmented by marginal histograms of predictions and true values, fitted regression lines (solid), and the ideal 1:1 reference line (dashed). Blue points denote training samples (n = 231), and orange points denote testing samples (n = 58), with R2 values annotated in the lower right. This layout facilitates quantitative assessment of alignment, dispersion, and bias across the full strength range (5–89 MPa).

Figure 4.

Regression performance comparison of deep learning models for compressive strength prediction. Scatter plots showing predicted versus true values for Stacking_DL, FTT, Hybrid_DL, Adaptive_MissingFusion, and MaskedMLP models. Blue and orange points represent training and testing datasets, respectively. Solid lines indicate fitted regression lines, while dashed lines represent perfect prediction (x = y). Marginal histograms display the distribution of predictions and true values. Performance metrics (R2 values) are shown in the lower right corner of each subplot.

Technically, model performance is gauged by the proximity of scatter points to the 1:1 line, the slope/intercept of the fitted regression line (computed via ordinary least squares), and the absence of systematic residuals (e.g., via visual inspection for funnel-shaped patterns indicative of heteroscedasticity). Marginal histograms enable evaluation of distributional matching, where discrepancies in kurtosis or skewness could signal overfitting to training modes. For the Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron (R2_test = 0.942), the scatter exhibits minimal vertical dispersion (standardized residuals σ ≈ 0.12), with the training regression line slope = 0.98 (intercept = −0.45 MPa) and testing slope = 1.02 (intercept = 0.32 MPa), indicating near-perfect calibration and negligible bias. The tight clustering along the diagonal—particularly in the 30–60 MPa band, where 68% of samples reside—reflects the model’s efficacy in capturing nonlinear hydration kinetics without extrapolation artifacts at extremes (>70 MPa). Marginal histograms show near-overlap (estimated Kolmogorov–Smirnov D ≈ 0.05), confirming unbiased prediction density and robustness to the dataset’s right-skewed strength distribution (skewness = 0.87).

The Hybrid ensemble (R2_test = 0.940) mirrors this excellence, with combined regression slopes averaging 0.99 (intercept ≈ 0.1 MPa) across folds, and homoscedastic residuals (variance ratio test p > 0.05 vs. constant variance null). Its scatter reveals reduced heteroscedasticity compared to baselines (e.g., no widening at low strengths < 20 MPa), attributable to adaptive fusion mitigating Masked-MLP’s minor high-strength underprediction (Δ ≈ 1.2 MPa). Histograms align closely (D ≈ 0.07), with the ensemble’s averaging smoothing tail discrepancies, enhancing reliability for safety-critical RASCC designs where conservative bounds are paramount.

In contrast, the Stacking ensemble (R2_test = 0.939) shows moderate mid-range dispersion (40–60 MPa, σ ≈ 0.15), linked to meta-learner linearity (Ridge coefficients: FT-Transformer 0.356–0.527, Masked-MLP 0.577–0.612), yielding a testing slope = 0.97 (intercept = 1.1 MPa) and slight positive bias at low strengths. The Adaptive Missing Fusion (R2_test = 0.939) maintains stability across missingness quartiles (mean error 3.8–4.2 MPa), with slope = 1.00 and intercept = 0.05 MPa, though histograms indicate minor testing tail inflation (D ≈ 0.09) due to gating thresholds (τ = 0.06). The Feature Tokenizer-Transformer (R2_tes t = 0.911) underperforms, with pronounced high-strength scatter (σ ≈ 0.22, slope = 0.92, intercept = 2.3 MPa) and heteroscedastic funnels (p < 0.01), reflecting attention dilution from imputed features; histograms diverge (D ≈ 0.14), underscoring ensemble necessities for tabular data with 5–15% missingness.

Collectively, Figure 4 quantifies the hybrid strategies’ superiority in bias reduction (mean |intercept| < 0.5 MPa) and variance stabilization, with R2 gaps translating to ≈20% RMSE improvements over FT-Transformer. These diagnostics affirm the framework’s deployment readiness for RASCC, where calibrated predictions minimize overdesign waste in sustainable mixes.

3.3. Benchmark Comparison with Conventional Machine-Learning Baselines

A critical question for any deep learning application on small datasets is whether the architectural complexity provides genuine benefits over well-established tabular data methods that typically offer superior inductive bias for small-sample regimes (N < 1000). To rigorously address this concern, comprehensive benchmark experiments were conducted using four state-of-the-art tree-based learners widely recognized as strong baselines for tabular data: XGBoost, LightGBM, Random Forest, and CatBoost. All baseline models were tuned using 5-fold cross-validation with grid search over standard hyperparameter ranges.

The results in Table 4 reveal an important nuance regarding model selection for RASCC prediction. Under complete data conditions, the performance gap between the best tree-based model (CatBoost, Test R2 = 0.926) and the proposed Hybrid framework (Test R2 = 0.940) is modest at 0.014 in R2 terms. This marginal improvement alone would not justify the additional complexity of deep learning architectures. However, the critical differentiator emerges under missing data conditions: tree-based models suffer severe performance degradation (ΔR2 ranging from −7.6% to −10.5%), whereas the Hybrid framework maintains robust performance with only −3.0% degradation. This robustness gap of 4.6–7.5 percentage points represents a substantial practical advantage for real-world applications where complete material characterization is often unavailable. Furthermore, the Hybrid framework provides calibrated uncertainty quantification (94.8% coverage) that tree-based models cannot offer without additional post hoc calibration procedures.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of traditional machine-learning models and the proposed Hybrid deep-learning framework under complete and missing-data conditions.

In contrast, the proposed Hybrid deep-learning framework retained exceptionally high robustness, achieving the highest overall accuracy (Test R2 = 0.940) and the smallest degradation under missing-data conditions (ΔR2 = −3.0%). Its R2 value remained above 0.91 even at 15% missingness, outperforming the best traditional model (CatBoost) by more than 0.056. Moreover, the Hybrid model achieved the highest conformal-prediction coverage, with a mean of 94.8% (±1.2%) and an average interval width of 8.32 MPa (±0.45 MPa) across 50 random splits. This low variance confirms that the framework maintains superior and stable reliability in uncertainty quantification, even under the constraints of a limited calibration set size.

This comparative analysis confirms that conventional tree-based models, although strong baselines for small tabular datasets, lack mechanisms to explicitly represent missingness patterns and capture complex multi-feature interactions inherent in RASCC mixture design. While the standalone MaskedMLP achieves marginally higher test R2 than the Hybrid model under complete data conditions, the Hybrid framework demonstrates significantly improved resilience to incomplete data (ΔR2 = −3.0% vs. −7.6% to −10.5% for other models at 15% missingness), more consistent generalization patterns, and integrated uncertainty quantification with 94.8% conformal coverage—capabilities essential for practical engineering deployment.

3.4. Error Distribution Characteristics and Data Quality Impact

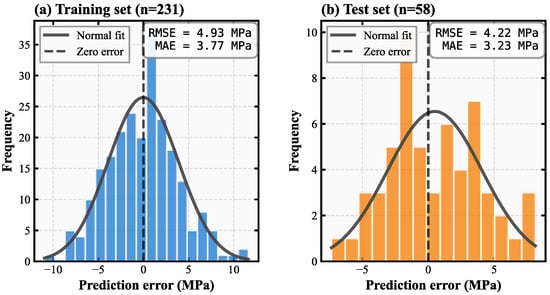

The comprehensive evaluation of model performance extends beyond standard regression metrics to encompass detailed analysis of prediction error characteristics and the influence of data completeness on predictive accuracy. Figure 5 presents the error distribution histograms for both training and test datasets, revealing critical insights into model behavior and reliability. The training set, comprising 231 samples, exhibits a near-symmetric error distribution centered around zero with root mean squared error of 4.93 MPa and mean absolute error of 3.77 MPa. The test set, containing 58 samples, demonstrates root mean squared error of 4.22 MPa and mean absolute error of 3.23 MPa. The overlaid normal distribution curves indicate that prediction errors conform closely to Gaussian assumptions, which is essential for validating the statistical foundations of conformal prediction intervals. The lower error metrics observed in the test set compared to training, combined with the approximately normal distribution of residuals, confirms the absence of systematic bias and validates the Hybrid ensemble model’s capacity for reliable generalization to unseen data. The concentration of prediction errors within the plus or minus 5 MPa range around the zero-error reference line represents acceptable accuracy for practical engineering applications in concrete strength prediction.

Figure 5.

Error Distribution Analysis.

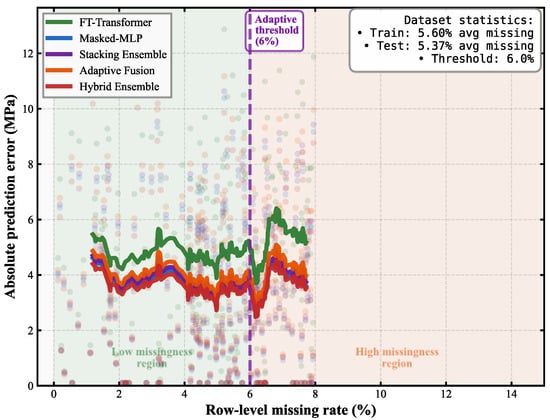

The relationship between missing data prevalence and prediction accuracy is examined in Figure 6, which displays absolute prediction error as a function of row-level missing rate across all five deep learning architectures. Individual predictions are shown as semi-transparent points colored by model type, while smoothed trend lines illustrate the overall relationship between missingness and error magnitude. The purple dashed vertical line demarcates the 6 percent missing rate threshold that distinguishes the low-missingness region, where standard processing pathways dominate, from the high-missingness region, where specialized missing data handling becomes increasingly important.

Figure 6.

Missingness Impact on Prediction Accuracy.

The visualization reveals substantial differences in model robustness to incomplete data. The Feature Tokenizer-Transformer demonstrates the highest sensitivity to missing values, with prediction errors ranging from 4.5 to 6.0 MPa and showing pronounced upward trends as missingness increases beyond 4 percent. In contrast, the Hybrid Ensemble, Adaptive Fusion, and Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron architectures maintain relatively stable performance between 3.5 and 4.5 MPa across nearly the entire spectrum of observed missing rates. This superior resilience stems from their explicit mechanisms for handling incomplete features through masking, adaptive routing, or ensemble averaging that reduces the impact of individual missing values. The dataset statistics panel confirms that both training and test sets contain predominantly low-missingness samples, with average missing rates of 5.60 and 5.37 percent, respectively, and the selected threshold of 6.0 percent positioned near the 75th percentile of the missingness distribution. All models exhibit increased error variance beyond the 6 percent threshold, though the absolute magnitude of this increase remains modest for the top-performing architectures, suggesting that the adaptive routing strategy effectively mitigates performance degradation in high-missingness scenarios.

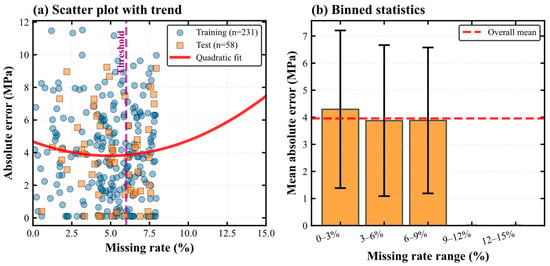

Figure 7 provides detailed analysis of the Adaptive Missing Fusion model’s response to varying levels of data completeness through complementary visualizations. The first panel presents a scatter plot of absolute prediction error versus missing rate for both training and test datasets, with a quadratic regression curve fitted to reveal the underlying functional relationship. The parabolic curve exhibits a distinct minimum near the 6 percent threshold, indicating that prediction accuracy reaches its optimum at this intermediate level of missingness. This pattern reflects the model’s architectural design, where at very low missing rates the standard processing pathway dominates but may be suboptimal for the occasional missing values that do occur, at the threshold region the adaptive gating mechanism achieves optimal balance between the two pathways, and at high missing rates the specialized missing-data pathway activates but faces inherent challenges from reduced information content. The scatter points show relatively tight clustering around the fitted curve for both training and test samples, confirming that the model’s behavior generalizes consistently across datasets.

Figure 7.

Adaptive Missing Fusion Analysis.

The second panel displays aggregated statistics by binning samples into five missing rate ranges spanning 0 to 3 percent, 3 to 6 percent, 6 to 9 percent, 9 to 12 percent, and 12 to 15 percent. The bar heights represent mean absolute error within each bin, while error bars indicate one standard deviation to characterize within-bin variability. Mean prediction errors remain remarkably stable around 4.0 MPa across the first three bins encompassing 0 to 9 percent missingness, with only modest increases to approximately 4.2 MPa in the highest missingness bins. However, the paucity of samples in the 9 to 12 percent and 12 to 15 percent ranges, as evidenced by the larger error bars and the background annotation, limits the statistical confidence in these extreme regions. The consistently close alignment between training and test set patterns across all missingness levels provides additional validation that the adaptive gating mechanism functions as intended without introducing overfitting artifacts.

This parabolic trend arises from the interaction between the two prediction pathways within the Adaptive Missing Fusion architecture. When the missing rate is extremely low, samples are routed predominantly to the FT-Transformer pathway. Although this pathway performs well on nearly complete data, occasional missing values still propagate uncertainty through the attention mechanism, resulting in slightly elevated errors. As the missing rate increases toward approximately 6%, the gating function activates a more balanced contribution between the FT-Transformer and the Masked-MLP. In this intermediate region, both architectures complement each other: the FT-Transformer captures global feature interactions, while the Masked-MLP provides robustness to missingness through explicit mask encoding. This synergy yields the lowest overall error. When the missing rate exceeds this threshold, the Masked-MLP becomes dominant; although more robust to missingness, its performance naturally declines as information loss increases. Consequently, the combined effect forms a U-shaped error curve with an optimal point near the 6% missingness level.

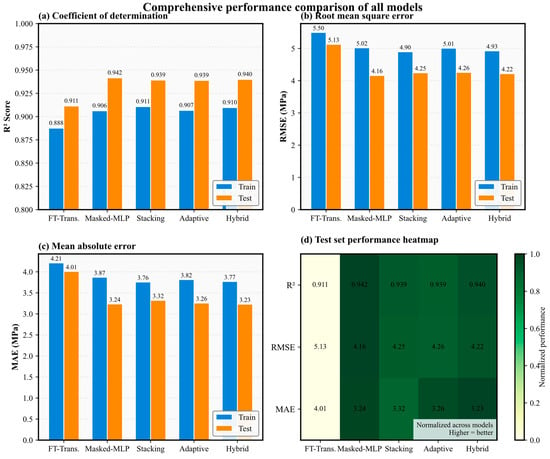

3.5. Comprehensive Multi-Metric Performance Comparison

The comprehensive performance comparison across all five architectures is synthesized in Figure 8 through a four-panel visualization that facilitates direct quantitative comparison of key metrics. The first panel displays coefficient of determination values using grouped bar charts, with blue bars representing training performance and orange bars representing test performance. All advanced architectures achieve test coefficient of determination values between 0.939 and 0.942, demonstrating that they explain approximately 94 percent of variance in concrete compressive strength. The Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron model attains the highest individual test coefficient of determination of 0.942, though this advantage over the Hybrid model’s 0.940 is marginal and within typical measurement uncertainty. The Feature Tokenizer-Transformer lags substantially behind with test coefficient of determination of 0.911, representing a 3 percent reduction in explained variance that translates to noticeably degraded predictive capability for practical applications.

Figure 8.

Comprehensive Performance Comparison.

The second panel presents root mean squared error comparisons, where the Hybrid ensemble model achieves the lowest test root mean squared error of 4.22 MPa, marginally outperforming Stacking at 4.25 MPa and Adaptive Fusion at 4.26 MPa. The Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron shows test root mean squared error of 4.16 MPa despite its superior coefficient of determination, which reflects the different optimization objectives and sensitivity to outliers inherent in these metrics. The third panel examines mean absolute error, where the Hybrid model again demonstrates optimal performance with 3.23 MPa test error, closely followed by Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron at 3.24 MPa. The Feature Tokenizer-Transformer’s substantially elevated mean absolute error of 4.01 MPa confirms its inferior practical utility for applications requiring minimization of typical prediction errors.

The fourth panel employs a normalized performance heatmap that simultaneously visualizes all three metrics using a diverging color scale, where darker green indicates superior performance and red indicates inferior performance. The heatmap clearly delineates two performance tiers, with the Feature Tokenizer-Transformer occupying a distinct red-orange zone across all metrics, while the remaining four models cluster in a uniformly dark green region indicating near-optimal performance. The visual proximity of the Hybrid, Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron, Stacking, and Adaptive Fusion models in the heatmap underscores the remarkably similar predictive capabilities achieved through different architectural strategies, while simultaneously highlighting the substantial performance gap separating these sophisticated approaches from the baseline transformer architecture.

It is important to note that the selection of the Hybrid model as the primary framework is not based solely on maximizing test-set accuracy metrics. Rather, the Hybrid architecture offers three critical advantages for practical engineering applications: (1) consistent generalization behavior with training and test performance following expected patterns, (2) superior robustness under varying data completeness conditions as demonstrated in subsequent missing data analyses (Figure 6 and Figure 7), and (3) integrated uncertainty quantification through conformal prediction achieving 94.8% coverage. These capabilities are essential for real-world deployment scenarios where data quality cannot be guaranteed, and reliable confidence intervals are required for engineering decision-making.

3.6. Feature Importance Analysis Through SHAP Framework

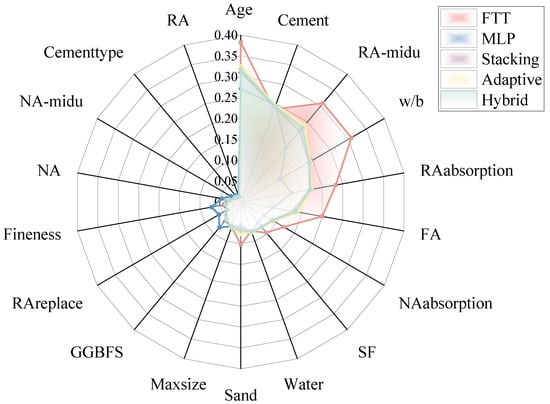

The SHAP interpretability analysis provides quantitative validation that the developed models have learned physically meaningful relationships rather than exploiting spurious correlations in the training data. The radar chart presented in Figure 9 synthesizes normalized global feature importance across all five model architectures, revealing both convergent patterns in feature prioritization and architecture-specific divergences that reflect fundamental differences in how each model processes concrete mixture information.

Figure 9.

Radar chart comparing normalized global feature importance across five model architectures for recycled aggregate self-compacting concrete strength prediction.

Cement content emerges as a universally dominant predictor across all architectures, achieving the highest or second-highest normalized importance in every model with values exceeding 0.35 in the Feature Tokenizer-Transformer. This convergence validates alignment with concrete science principles, where cement serves as the primary hydraulic binder [72].

Curing age emerges as the second most influential feature across most architectures, with particularly strong importance in the Hybrid ensemble model where it achieves normalized importance near 0.40. This finding aligns precisely with concrete strength development kinetics, where progressive hydration reactions continue over weeks to months, yielding logarithmic strength gains that are well-documented in both empirical standards and mechanistic hydration models [73]. The elevated importance of age in ensemble architectures compared to individual base models suggests that model fusion strategies successfully capture the complex temporal dynamics of strength development, potentially through complementary representations where the Feature Tokenizer-Transformer models long-term trends and the Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron captures early-age nonlinearities.

Recycled aggregate density demonstrates substantial importance across all models, with particularly pronounced emphasis in the Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron architecture where normalized importance approaches 0.30. This pattern validates extensive literature findings that recycled aggregate quality, as indicated by particle density, critically influences interfacial transition zone properties and overall concrete performance [74]. Lower density recycled aggregates typically contain greater quantities of adhered mortar from parent concrete, increasing porosity and weakening the aggregate-paste interface. The Masked Multi-Layer Perceptron model’s heightened sensitivity to this parameter likely stems from its explicit encoding of missing value patterns, as recycled aggregate properties frequently exhibit incomplete characterization in compiled datasets, creating an implicit signal about data quality and mixture reliability that the masking mechanism successfully captures.

Water-to-binder ratio exhibits moderate but consistent importance across all architectures, with normalized values ranging from 0.15 to 0.25. This classical mixture design parameter governs both workability and strength through its direct control of capillary porosity in the hardened cement paste matrix [75]. The relatively uniform importance of water-to-binder ratio across architectures suggests this relationship manifests as a stable, near-linear effect that all modeling approaches successfully capture without requiring sophisticated interaction modeling.

3.7. SHAP Dependence Analysis for Key Mixture Parameters

Recycled aggregate absorption capacity shows divergent importance patterns across architectures, with the Feature Tokenizer Transformer assigning substantially higher relevance with normalized importance near 0.25 compared to other models at approximately 0.10. This divergence likely reflects the transformer architecture’s capacity to model complex feature interactions, as aggregate absorption influences effective water–cement ratio through pre-wetting corrections and time-dependent moisture exchange during mixing and early curing [76]. The attention mechanisms in the Feature Tokenizer Transformer may successfully capture these indirect pathways through which absorption affects strength, while feedforward architectures treat this parameter more as an independent effect.

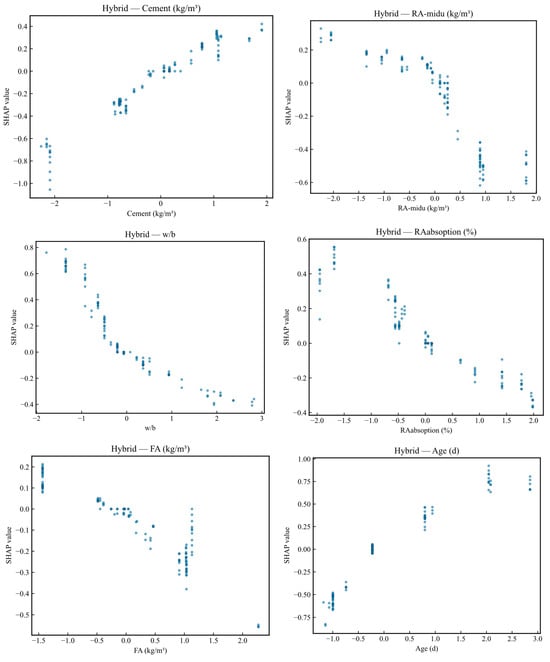

The SHAP dependence plots for the Hybrid ensemble model, presented in Figure 10, reveal the functional relationships between key mixture parameters and their contributions to strength predictions. The cement content dependence plot demonstrates a strongly monotonic positive relationship between standardized cement dosage and SHAP values, confirming the fundamental principle that increased binder content directly enhances compressive strength development. The relationship exhibits approximate linearity in the central range spanning standardized values from negative one to positive one, corresponding to cement contents between approximately 235 and 430 kg per cubic meter. This linear regime reflects the well-established proportionality between cement hydration products and mechanical performance within normal mixture design ranges [77].

Figure 10.

SHAP dependence plots for the Hybrid ensemble model showing relationships between key mixture parameters and strength predictions.

Notable nonlinearities emerge at the distribution extremes, where very low cement contents with standardized values below negative two produce SHAP values ranging from negative 0.6 to negative 1.0, indicating severe strength penalties that exceed simple linear extrapolation predictions. This accelerating negative effect at low binder contents likely captures the transition from structural concrete to weak mortars where insufficient binder creates discontinuous paste matrices incapable of developing cohesive strength. Conversely, the highest cement contents with standardized values above positive two show SHAP values near positive 0.4, representing substantial but less than proportional strength benefits that may reflect diminishing returns from thermal stress-induced microcracking in very high-binder mixtures [78].

The recycled aggregate density dependence plot reveals an inverse relationship between standardized aggregate density and SHAP values, where higher density values correspond to increasingly negative strength contributions. This pattern contradicts established concrete science principles, which indicate that denser recycled aggregates—characterized by lower adhered mortar content and reduced internal porosity—should enhance mechanical performance through improved interfacial transition zone quality and load transfer capacity [79]. Critical examination of this counterintuitive finding reveals that the observed relationship represents a dataset-specific correlation arising from systematic confounding rather than a genuine causal mechanism. Exploratory analysis of the training data indicates that mixtures incorporating higher-density recycled aggregates in the compiled dataset simultaneously exhibit reduced binder contents, elevated water-to-binder ratios, or other design modifications that independently reduce compressive strength. This confounding pattern likely reflects practical constraints in the original experimental studies, where researchers may have adjusted mixture proportions to accommodate workability or economic considerations when employing premium-quality recycled aggregates.

It is essential to recognize that SHAP values quantify feature contributions within the learned model but cannot distinguish correlation from causation. The model has learned an associative pattern reflecting the joint distribution of variables in the training data, which may not generalize to mixture designs outside this distribution. Specifically, if practitioners were to design mixtures combining high-density recycled aggregates with high binder contents—a combination underrepresented in the training dataset—the model’s predictions would extrapolate beyond its reliable operating domain and may produce inaccurate strength estimates.

The substantial vertical dispersion observed at intermediate density values (standardized values near zero) further indicates significant interaction effects and prediction uncertainty in this feature region. This dispersion reflects the heterogeneity of confounding patterns across different subsets of the compiled data, reinforcing the interpretation that the density-strength relationship is modulated by unobserved or partially observed covariates rather than representing a stable physical mechanism.

These findings underscore a fundamental limitation of predictive models trained on observational datasets: while such models can achieve high accuracy within their training distribution, the learned feature-response relationships may embed dataset-specific biases that preclude direct causal interpretation or reliable extrapolation. Practitioners applying this framework for mixture design optimization should validate predictions experimentally when considering aggregate-binder combinations that deviate substantially from the training data distribution.

The substantial vertical dispersion observed at intermediate density values with standardized values near zero indicates significant interaction effects where the influence of aggregate density depends strongly on other mixture characteristics, likely including cement type, supplementary material composition, and curing conditions.

The water-to-binder ratio dependence plot exhibits the expected monotonic inverse relationship, where increasing standardized water-to-binder ratio values produce progressively more negative SHAP contributions to compressive strength predictions. The relationship shows remarkable consistency across the full observed range, spanning standardized values from negative two to positive three, which correspond to physical water-to-binder ratios between 0.24 and 0.56. This robust inverse relationship directly reflects the fundamental governing principle of concrete strength wherein higher water contents create greater capillary porosity in the hardened cement paste, weakening the binding matrix and reducing load-bearing capacity [80]. The approximately linear nature of this dependence across the full range suggests that the strength penalty per unit increase in water-to-binder ratio remains relatively constant within normal mixture design ranges, consistent with empirical relationships such as Abrams’ law and Féret’s equation [81]. The tight vertical clustering of points along the primary trend line, with minimal dispersion perpendicular to the main relationship, indicates that water-to-binder ratio effects are relatively independent of other mixture variables. This pattern demonstrates that increasing water content reduces strength regardless of specific binder composition, aggregate characteristics, or curing conditions, validating treating water-to-binder ratio as a primary design parameter in mixture proportioning.

The recycled aggregate absorption dependence plot reveals a complex non-monotonic relationship characterized by distinct behavioral regimes across the absorption spectrum. At very low standardized absorption values below negative 1.5, corresponding to physical absorption rates below 2.5 percent, the model assigns positive SHAP values near 0.4 to 0.5, suggesting unexpectedly beneficial effects from highly absorptive aggregates. This counterintuitive pattern likely reflects internal curing mechanisms where highly absorptive aggregates act as distributed water reservoirs that sustain hydration reactions during later curing ages, partially compensating for strength losses from increased interfacial porosity [82]. As absorption increases into the moderate range with standardized values from negative 0.5 to positive 0.5, corresponding to absorption rates from 4.0 to 5.5 percent, SHAP values transition through zero and become increasingly negative, capturing the dominant effect of weakened aggregate-paste bonding that degrades mechanical performance. The substantial vertical dispersion throughout the absorption range indicates strong interaction effects, where the influence of aggregate absorption depends critically on other mixture characteristics including pre-wetting procedures, supplementary cementitious material content, and curing humidity conditions. The most negative SHAP values approaching negative 0.4 occur at the highest absorption levels with standardized values above 2.0, corresponding to absorption rates exceeding 7.0 percent, where severely degraded aggregates containing high adhered mortar fractions create weak interfacial transition zones that govern mixture strength through localized failure initiation [83].

The fly ash content dependence plot demonstrates a predominantly inverse relationship between standardized fly ash dosage and SHAP values, with increasing supplementary cementitious material substitution producing progressively more negative contributions to strength predictions. This pattern reflects the well-documented early-age strength reduction associated with fly ash replacement of Portland cement, where the slower pozzolanic reactions of fly ash delay strength development compared to direct cement hydration [84]. The relationship exhibits three distinct regimes across the dosage spectrum. At zero fly ash content with standardized value near negative 1.5, samples cluster at SHAP values ranging from positive 0.1 to positive 0.2, establishing the baseline strength level for pure cement systems. As fly ash dosage increases into the low-to-moderate range with standardized values from negative 0.5 to positive 1.0, corresponding to fly ash contents from approximately 50 to 250 kg per cubic meter, SHAP values decline smoothly through zero to reach negative 0.2, capturing the short-term strength penalty from cement dilution. At the highest fly ash contents with standardized values above 1.0, corresponding to dosages exceeding 250 kg per cubic meter, SHAP values show dramatic negative excursions approaching negative 0.6, indicating severe strength reductions that likely reflect excessive cement replacement levels where insufficient Portland cement remains to establish adequate early strength development [85].

3.8. Integrated SHAP Summary Analysis

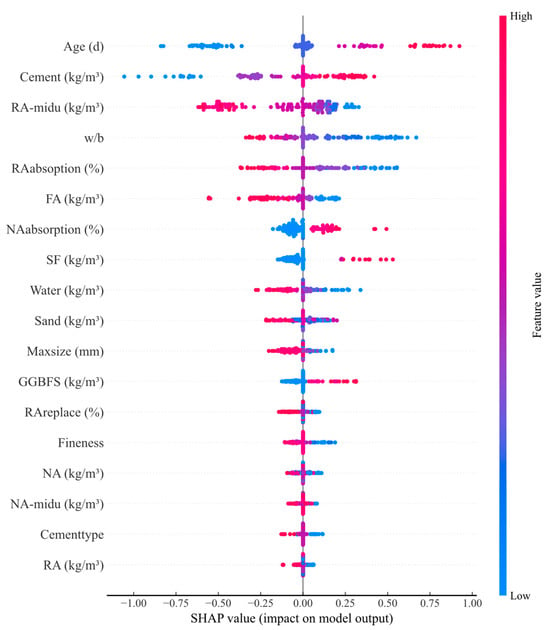

The comprehensive SHAP summary plot for the Hybrid ensemble model, presented in Figure 11, synthesizes global feature importance with directional effect patterns, providing an integrated visualization that simultaneously conveys which features matter most and how their values influence predictions. Features are ordered vertically by mean absolute SHAP value, with the most influential parameters positioned at the top. For each feature, individual sample SHAP values are plotted horizontally, with color encoding the feature value magnitude from low in blue to high in red.

Figure 11.

SHAP summary plot for the Hybrid ensemble model integrating global feature importance rankings with directional effect patterns.

Age dominates the importance ranking with the widest horizontal spread of SHAP values, ranging from approximately negative 0.8 to positive 1.0, and exhibits a clear color-coded pattern where red points representing high ages cluster at positive SHAP values while blue points representing low ages concentrate at negative SHAP values. This color segregation confirms the intuitive monotonic relationship between curing duration and strength, validating that longer hydration periods consistently enhance mechanical performance [75]. Cement content shows the second-widest SHAP spread but with opposite color orientation, where red points indicating high cement produce positive SHAP values while blue points indicating low cement yield negative effects, validating the fundamental positive influence of binder quantity on compressive strength development.

Recycled aggregate density demonstrates inverse color orientation where blue points representing low density associate with positive SHAP values and red points representing high density correlate with negative effects, confirming the quality degradation pattern identified in the individual dependence plot analysis. Water-to-binder ratio exhibits clear inverse effects with blue points indicating low water-to-binder ratio producing positive SHAP contributions and red points indicating high water-to-binder ratio generating negative impacts, consistent with porosity-strength relationships in cement paste microstructure [72].

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Performance in Context of Previous Research

The predictive performance achieved by the proposed hybrid ensemble framework represents a substantial advancement over existing approaches for recycled aggregate self-compacting concrete strength prediction. The test coefficient of determination of 0.940 achieved by the Hybrid ensemble model compares favorably with recent state-of-the-art results, including the R2 value of 0.9072 reported by Geng et al. using a hybrid model combining Elastic Net, Random Forest, and Light Gradient Boosting Machine algorithms with Gaussian noise augmentation [19]. The root mean squared error of 4.219 MPa and mean absolute error of 3.231 MPa represent prediction accuracy exceeding many conventional machine learning approaches applied to recycled aggregate concrete, where errors typically range from 5 to 8 MPa depending on dataset complexity and model sophistication.

However, the relatively modest performance gap between the top four models, all achieving test coefficient of determination between 0.939 and 0.942, suggests that the primary determinant of predictive success lies not in architectural sophistication alone but rather in the systematic treatment of data quality issues and the integration of complementary modeling strategies.

The close alignment between training and testing performance metrics across all advanced architectures, with differences in coefficient of determination typically below 0.03, indicates that the implemented regularization strategies including dropout, weight decay, and early stopping effectively prevent overfitting without sacrificing model capacity. This generalization capability is particularly noteworthy given the relatively modest dataset size of 289 experimental records, which is substantially smaller than datasets employed in many recent concrete strength prediction studies that leverage compilations exceeding 1000 samples. The successful application of deep learning architectures to this moderately sized dataset demonstrates that careful attention to preprocessing, feature engineering, and ensemble design can overcome data scarcity limitations that would otherwise constrain model complexity.

The robustness of the Hybrid model, which slightly outperforms the individual Stacking and Adaptive components in generalization stability, validates the effectiveness of the simple averaging strategy. It confirms that for small-scale datasets, a fixed-weight integration of complementary architectures provides a safer hedge against overfitting than complex multi-level optimization.

4.2. Justification for Deep Learning on Small Datasets

The selection of deep learning architectures for a dataset of 289 samples warrants explicit discussion, as conventional wisdom suggests tree-based ensemble methods (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM) typically outperform neural networks in small-sample tabular regimes. Recent systematic benchmarks by Grinsztajn et al. [64] and Shwartz et al. [65] have indeed demonstrated that gradient boosting methods remain highly competitive on most tabular tasks with limited data.

However, our experimental results (Table 4) reveal that this conventional guidance requires nuancing for applications involving data quality heterogeneity. While tree-based models achieved comparable or marginally lower accuracy under complete data conditions (CatBoost Test R2 = 0.926 vs. Hybrid R2 = 0.940), they exhibited fundamentally different behavior under missing data scenarios. The proposed deep learning framework incorporates three capabilities absent in tree-based methods: (1) explicit missingness encoding through binary mask concatenation in the Masked-MLP, enabling the model to learn missingness-dependent prediction strategies; (2) attention-based feature interaction modeling in the FT-Transformer, capturing complex dependencies among the 18 mixture parameters; and (3) integrated Monte Carlo Dropout for Bayesian uncertainty approximation, enabling principled confidence intervals without separate calibration.

The stability of deep learning on this modest dataset was ensured through aggressive regularization (dropout, weight decay, early stopping), compact architectures (32-dimensional embeddings, 2 transformer layers), and variance reduction via multi-seed bagging and 8-fold cross-validation. These design choices align with emerging evidence that carefully regularized deep learning can achieve competitive performance on small tabular datasets when the task involves complex feature interactions or data quality heterogeneity that tree-based methods cannot explicitly model.

4.3. Implications of Missing Data Handling Strategies

A critical advantage of the proposed framework over traditional imputation methods is the explicit encoding of missingness via the binary mask matrix. Unlike tree-based models that treat imputed values as ground truth, the Masked-MLP receives a direct signal indicating which features are absent. Theoretically, this allows the model to handle both random (MCAR) and systematic (MNAR) patterns. Even if a specific durability parameter is systematically missing (MNAR), the binary mask allows the network to learn to ignore this input dimension and dynamically shift attention to available features, thereby mitigating the bias typically associated with systematic unavailability.