Abstract

Expansive soils undergo significant volumetric changes during wetting and drying, often leading to structural deterioration and engineering difficulties. Alkali-activated binders have been widely utilized to improve the mechanical performance and durability of such soils. This study examines the performance of γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (KH-550)-modified alkali-activated binder-stabilized expansive soils (AABS). As a result, the addition of KH-550 extended the setting times by up to 89% and enhanced fluidity by 6–27%, thereby improving the workability of AABS. The additive delayed early hydration while accelerating later-stage gel formation via hydrolysis and Si–O–Si bond generation, promoting the development of C-(A)-S-H. Microstructural observations indicated a refinement of pores and a reduction in capillary porosity, yielding a denser and more homogeneous matrix. Autogenous shrinkage was reduced by as much as 32.5%, and the unconfined compressive strength of 7 d AABS increased by 58.1% at an optimal KH-550 dosage of 1.0 wt.%, with mechanical performance remaining stable under wet–dry cycling. Overall, these results suggest that KH-550 serves as an effective organic–inorganic bridging agent, offering a viable strategy for the stabilization of expansive soils.

1. Introduction

Expansive soils are highly active clays that exhibit pronounced swell–shrink behavior and a strong propensity for fissure formation [1,2]. Their mineralogical composition is dominated by hydrophilic minerals, including montmorillonite and illite, with montmorillonite showing particularly high swelling potential and sensitivity to moisture fluctuations. These characteristics result in substantial volume changes, high compressibility, and low shear strength [3,4,5]. As a result, subgrades constructed on expansive soils frequently experience settlement, surface cracking, and mud pumping, making the control of deformation and cracking a critical concern in geotechnical engineering.

Traditional stabilization methods using lime or cement have proven effective in mitigating swell–shrink behavior while improving soil strength and stability. For instance, Woldesenbet [6] reported that treatment of expansive soils with kilned soil and glass waste increased unconfined compressive strength from 216 kPa to 910 kPa, decreased the plasticity index from 58.79% to 19.91%, and elevated the California bearing ratio from 0.95% to 12.08% after 14 d. Similarly, Kamei et al. [7] demonstrated that soft clay stabilized with recycled Bassanite and furnace cement showed enhanced strength and dry density with increasing Bassanite content, while maintaining durability under wetting–drying cycles. However, the production of lime and cement is energy-intensive and generates significant emissions of CO2, SO2, and particulate matter, with CO2 alone accounting for 8–10% of global emissions. Therefore, the development of alternative stabilizers that improve soil performance while minimizing environmental impact is of great importance.

Alkali-activated binders, also known as alkaline cements, offer a sustainable replacement for lime and cement, potentially reducing greenhouse-gas emissions by up to 80% compared with Portland cement [8,9]. In high-calcium systems, alkali activation of amorphous SiO2- and Al2O3-rich materials results in C–(A)–S–H gels, analogous to the C–S–H hydration products found in Portland cement. These products provide strong bonding, fill soil pores and improve overall strength and durability [10]. Accordingly, alkali-activated industrial wastes have gained attention as promising materials for stabilizing expansive and other problematic soils. For example, Miraki et al. [11] demonstrated that mixtures of alkali-activated ground-granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS) and volcanic ash can effectively stabilize clayey soil by forming N–A–S–H and C–(A)–S–H gels, which enhance compressive strength, improve durability against wet-dry and freeze-thaw cycles, and reduce carbon emissions. Yi et al. [12] evaluated marine soft clay stabilized with alkali-activated GGBS using various activators, showing that Na2SO4–carbide slag–GGBS achieved the highest strength, at least twice that of Portland cement–stabilized clay. Bruschi et al. [13] investigated an alkali-activated hybrid binder composed of sugar cane bagasse ash and carbide lime for bauxite tailings stabilization, finding that a mixture of 70% sugar cane bagasse ash and 30% carbide lime with 1 M NaOH significantly improved strength, stiffness, and durability. Although alkali-activated binders can improve expansive soils via C–(A)–S–H gel formation, the high surface activity and hydrophilicity of expansive-soil particles may still lead to sub-optimal bonding between particles and hydration products. Therefore, a multifunctional additive is required to enhance the performance of alkali-activated binder-stabilized expansive soils (AABS).

Recently, silane coupling agents (SCAs) have attracted considerable attention in inorganic cementitious systems. Studies have demonstrated that the hydrolysis products of SCAs can react with hydroxyl groups in C–S–H gels via condensation to form siloxane covalent bonds, thereby modifying the cementitious matrix and significantly improving fresh properties, water resistance, and mechanical performance [14,15,16,17,18,19]. In addition, SCAs are free of heavy metal ions and effective at ambient temperature, making them highly promising as green chemical admixtures. For instance, Feng et al. [20] reported that the addition of 0.5% SCA enhanced the microstructure of C–S–H gels and increased the 28-day compressive strength of mortar by 9.5%. Similarly, Švegl et al. [21] found that incorporating 1.2% SCA improved the workability of ordinary Portland cement mortar by 29% and increased the 28-day compressive strength by 5.7%. However, most conventional SCAs—primarily alkyl-, epoxy-, or vinyl-functional silanes—act mainly as surface modifiers and exhibit limited chemical interaction with inorganic surfaces. Their contribution to interfacial bonding between expansive soil particles and hydration products is therefore limited. In contrast, γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (KH-550) contains amino functional groups with substantially higher chemical reactivity. The electron-rich nitrogen enables rapid hydrogen bonding with hydroxyl-rich slag and expansive soil surfaces, while the silanol groups participate in condensation reactions to form siloxane bridges. This dual mechanism allows KH-550 to actively engage in the hydration–gelation process, rather than functioning merely as a surface coating, providing distinct advantages over conventional silane-based additives. Yu et al. [22] investigated KH-550 as a multifunctional admixture for alkali-activated slag and reported that 2.5% KH-550 improved slump, refined pore structure, reduced capillary water absorption by 1.7–11.5%, and increased the 28-day compressive strength by 4.8–34.3%. Nevertheless, their study focused exclusively on binder systems and did not address the more complex soil–binder interface in expansive soils, where high surface activity, strong hydrophilicity, and heterogeneous mineralogy limit gel bonding. The behavior of KH-550 in such systems—including its role in modifying soil particle surfaces, enhancing gel–soil interfacial strength, mitigating autogenous shrinkage, and improving macroscopic mechanical performance—remains unexplored.

Therefore, the novelty of this study lies in extending KH-550 from binder-only systems to the stabilization of expansive soils using alkali-activated binders (AABS). This work clarifies the interfacial mechanisms unique to soil environments, quantifies the multifunctional improvements in workability, shrinkage and strength, and demonstrates that KH-550 offers advantages not achievable by conventional SCAs or by its previously reported applications in alkali-activated slag alone.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

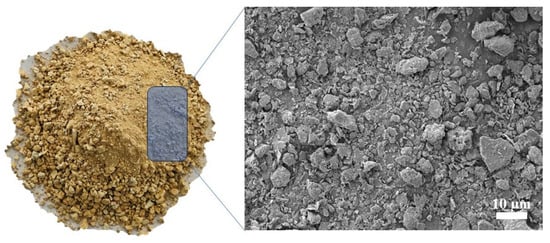

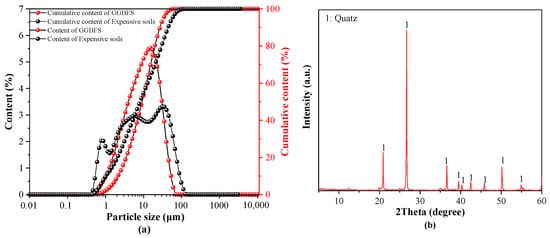

Expansive soils were collected from the excavation site of the Guangxi Hengyang–Nanning Highway. The soil exhibited a specific surface area of 10.25 m2/g, measured using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method. Figure 1 shows the photograph and microscopic morphology of the expansive soils. In addition, the expansive soil has a liquid limit of 33.6%, a plasticity index of 16%, a specific gravity of 2.7, and a free swell potential of 42.3%. Ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS), with an apparent density of 2800 kg/m3, was provided by Blast Furnace (Fuyang Xinyuan Building Materials Co., Ltd., Fuyang, China). The chemical compositions of the expansive soils and GGBFS were determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis, and the results are listed in Table 1. Figure 2 presents the particle size distribution of GGBFS and expansive soils, along with the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the expansive soils. A CP-1200 water-reducing agent was supplied by Water-Reducing Agent Production Equipment (Nanjing Xinyi Synthetic Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China). Quartz powder (80 mesh) was used as filler. Sodium hydroxide and sodium silicate nonahydrate were purchased from Sodium Hydroxide and Sodium Silicate Nonahydrate Preparation Equipment (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Beijing, China.

Figure 1.

Photograph and morphology of expansive soils.

Table 1.

Chemical compositions of GGBFS and Expansive soils (%).

Figure 2.

GGBFS and expansive soils: (a) particle size distribution, (b) XRD analysis of expansive soils.

2.2. Mix Proportion and Samples

The activator was prepared in advance according to the proportions listed in Table 2, with a solid-to-liquid ratio of 0.4 and an alkali concentration of 3.0 mol/L, stirred until fully dissolved, and allowed to cool to room temperature. All powders were weighed according to the specified mix ratios listed in Table 3 and stirred for 2 min to ensure homogeneity. CP-1200 was dissolved in the activator prior to mixing and added to the well-blended powder at a dosage of 0.5 wt.% of the total powder mass. The mixture was then stirred for an additional 2 min to achieve uniform distribution.

Table 2.

Proportion of activator (100 g).

Table 3.

Proportion of pastes (100 g).

2.3. Testing Methods of Samples

2.3.1. Workability

The Vicat needle method, according to ASTM C191 [23], was used to measure AABS setting times. Samples were cast in 40 mm-high containers with 75 mm bottom and 65 mm top diameters and cured at 20 ± 3 °C and over 95% relative humidity.

Fluidity of AABS samples was measured with an STNLD-3 tester (Beijing Zhongke Jianyi Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) per ASTM C1437 [24], recording the average spread in two perpendicular directions after 25 vibrations.

2.3.2. Autogenous Shrinkage of the AABS

The autogenous shrinkage of the AABS samples was evaluated using the corrugated-tube method in accordance with ASTM C1698 [25]. Fresh samples were injected into corrugated tubes and placed under standard curing conditions at 20 ± 2 °C and relative humidity of 95 ± 5%. After the samples reached the final setting, the specimens were mounted on a dedicated measurement frame equipped with a displacement transducer with a resolution of one micrometer. The deformation of each specimen was continuously recorded for 7 days from the time corresponding to the final setting.

2.3.3. Hydration Properties

Isothermal calorimetry according to ASTM C1702 [26] was used to study the hydration kinetics of AABS. A 50 g sample was placed in a glass container and monitored at 25 °C for 72 h to record heat evolution.

Hydration products of AABS were examined by high-resolution XRD using Cu-Kα radiation at 40 kV and 30 mA. To halt hydration, samples of the same age were soaked in anhydrous ethanol for seven days, vacuum-dried, and ground below 75 μm before scanning from 5° to 50° 2θ at 3°/min.

The composition of AABS hydration products was determined by thermogravimetric analysis using an STA 449 F3 Jupiter (NETZSCH-Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany). About 5 mg of powder, prepared as for XRD, was heated from room temperature to 900 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min.

2.3.4. Pore Structure

The pore structure of 7 d AABS samples was analyzed using a MicroActive AutoPore V 9600 mercury intrusion porosimeter (MIP) (Micromeritics Instrument Corporation, Norcross, GA, USA). The maximum intrusion pressure (Pmax) was set at 200 MPa, with mercury surface tension of 0.48 N/m and a contact angle of 130°.

2.3.5. Microstructure

SEM analysis of AABS hydration products was conducted using a ZEISS Gemini 300 (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen/Jena, Germany) at 5 kV. Soybean-sized specimens were prepared as described in Section 2.3.3, then cleaned with nitrogen, gold-coated, and mounted with conductive adhesive before imaging.

2.3.6. Mechanical and Durability Properties

The unconfined compressive strength of AABS samples was determined using specimens prepared and cured following ASTM C192 [27]. Freshly mixed AABS was cast into cylindrical molds with a base diameter of 50 mm and a height of 100 mm, then cured under controlled conditions at 20 ± 2 °C and 95 ± 5% relative humidity. After 7 days, six specimens were tested to obtain the average compressive strength and standard error.

Subsequently, the specimens were immersed in water at 20 ± 2 °C for 3 days, and unconfined compressive strength was re-measured. After a 28-day standard curing period under the same temperature and humidity conditions, specimen durability was evaluated via wet–dry cycling, following methodologies from prior studies [28,29]. Each cycle involved 24 h immersion in room-temperature water followed by 24 h oven-drying at 45 °C, for a total duration of 48 h. Four full cycles were performed (totaling 8 days), with mass and unconfined compressive strength measured at the end of cycles 0 through 4. The detailed procedure is outlined in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of the experimental program for wet–dry cycling.

3. Results

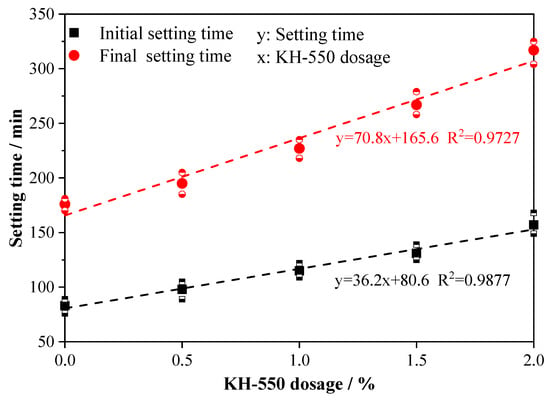

3.1. Setting Time

Figure 3 presents the setting times of AABS samples containing different dosages of KH-550. As shown, the addition of KH-550 significantly retarded the setting process. Both the initial and final setting times increased almost linearly with the dosage of KH-550. Compared with the control sample (ASK0), the addition of 0.5–2.0% wt.% KH-550 significantly extended the initial and final setting times by 18.1–89.2% and 10.8–80.1%, respectively. This retardation effect is attributed to the adsorption of hydrolyzed KH-550 silane molecules onto the surfaces of slag and soil particles, which hinders early ion dissolution and delays the setting process [21]. The prolonged setting time provided by KH-550 also enhances workability and promotes a more uniform distribution of binders within the stabilized expansive soils. In summary, KH-550 significantly retards both the initial and final setting of AABS in a dosage-dependent manner. This extended workable time is beneficial for practical mixing and placement operations.

Figure 3.

Setting times of AABS samples.

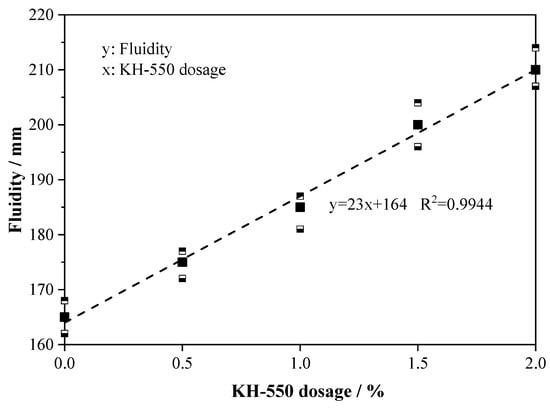

3.2. Fluidity

Figure 4 illustrates the fluidity of fresh AABS samples with varying KH-550 dosages. The results show that adding 0.5–2.0 wt.% KH-550 significantly improved fluidity, with increases of 6.1–27.2% compared to ASK0. Fluidity exhibited an approximately linear relationship with KH-550 content, suggesting a predictable influence of dosage on paste workability. This enhancement is attributed to the organic silane structure of KH-550, whose hydrophobic groups reduce interparticle friction and facilitate more uniform dispersion of slag and expansive soil particles [22]. Furthermore, the partial retardation of early hydration limits the formation of flocculated products in the fresh paste, further promoting flowability. These combined effects are particularly advantageous for stabilizing expansive soils, ensuring even binder distribution and enhanced workability within the solidified matrix.

Figure 4.

Fluidity of AABS samples.

3.3. Hydration Kinetics

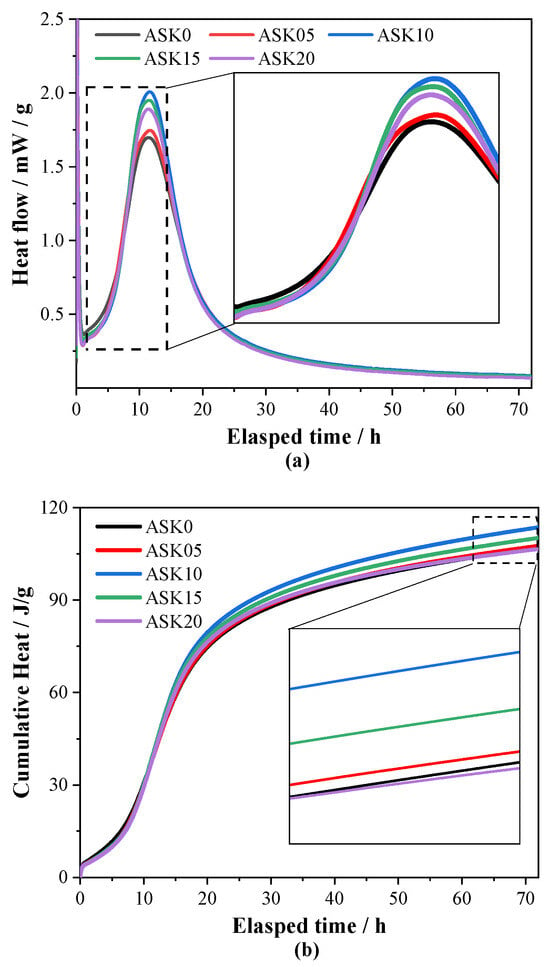

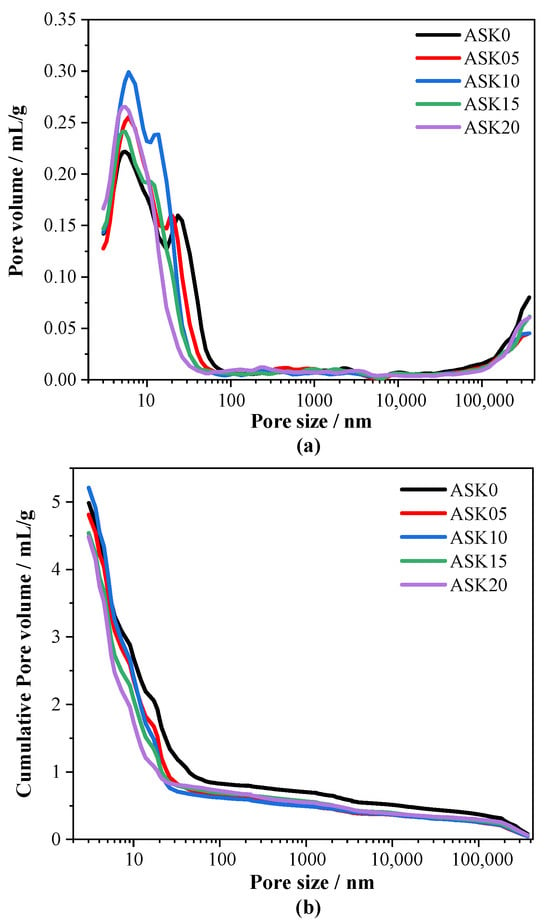

Figure 5a presents the heat flow of AABS samples. Two distinct exothermic peaks can be observed. Isothermal calorimetry was employed to investigate the impact of KH-550 on the temporal evolution of the hydration reactions in AABS. The first peak occurs within minutes after mixing, corresponding to the wetting and initial dissolution of slag particles, while the second, more pronounced peak is associated with the rapid formation of hydration products [30,31,32]. Addition of KH-550 shifted the heat flow curves to the right, particularly during the induction period, indicating effective retardation of early hydration and setting, consistent with the observed setting-time results. Interestingly, the intensity of the main exothermic peak was influenced by KH-550 dosage; for instance, 2.0 wt.% KH-550 reduced the peak height by 18% compared with ASK0, suggesting a more prolonged and sustained hydration process. This effect is attributed to the hydrolysis of KH-550 into silanol groups, which condense to form Si–O–Si linkages or silane oligomers that serve as additional nucleation sites, facilitating the polymerization of and C–A–S–H gels. Moreover, interactions between hydrolyzed KH-550 and soil minerals such as montmorillonite may enhance particle dispersion and generate more reactive interfaces, further promoting gel formation at later stages. Overall, KH-550 delays early hydration while supporting the continuous development of hydration products in AABS and improving interaction with expansive soil components.

Figure 5.

Hydration kinetics of AABS samples: (a) heat flow; (b) cumulative heat flow.

Figure 5b shows the cumulative hydration heat of AABS samples. In the early stage, all KH-550-containing pastes exhibited lower cumulative heat compared with ASK0, indicating retardation of initial hydration. As hydration progressed, the cumulative heat of the KH-550-modified pastes gradually exceeded that of ASK0 after about 10 h and remained slightly higher at 72 h, suggesting that KH-550 facilitates sustained hydration during later stages. The enhanced later-stage hydration can be partially attributed to the improved reactivity at the soil–binder interface due to interactions between hydrolyzed KH-550 and clay minerals, which facilitate further gel growth. However, an excessive KH-550 dosage (e.g., 2.0 wt.%) did not further increase cumulative heat, suggesting the existence of an optimal KH-550 content for maximizing the hydration degree of AABS. These results demonstrate that KH-550 retards early-stage hydration but promotes a more sustained reaction at later stages. This modified hydration profile supports the observed changes in setting behavior and microstructure development.

3.4. XRD

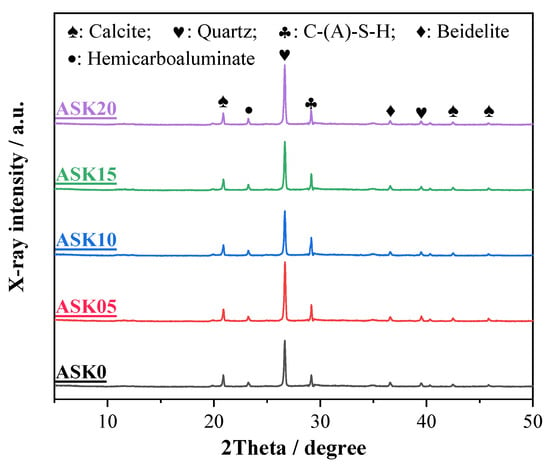

Figure 6 shows the XRD patterns of 7 d AABS samples. The main crystalline phases identified include calcite, hemicarboaluminate, quartz, C–(A)–S–H, and beidellite [33]. Quartz originates from the expanded soil, while calcite, mainly composed of calcium carbonate, is produced by the reaction of calcium oxide in slag during hydration. Beidellite ((Na, Ca)Al2Si4O10(OH)2) forms during alkali activation in the presence of Ca2+ and Na+ cations [34]. Hemicarboaluminate is a partial carbonate AFm phase formed from C3A hydration in the presence of limited [35]. With increasing KH-550 dosage, the intensity of the quartz peak at 2θ = 26.7° and the C–(A)–S–H peak at 2θ = 29.2° gradually increased, indicating that KH-550 promotes the formation of hydration products in AABS. This enhancement is likely due to the hydrolysis of KH-550, which generates silanol groups (–Si–OH) that facilitate nucleation and growth of C–(A)–S–H gels. In contrast, the characteristic peaks of montmorillonite and illite were not detected, suggesting that these clay minerals were altered during alkali activation, contributing to reduced swelling and improved stability of the solidified expansive soils.

Figure 6.

XRD patterns of 7 d AABS samples.

3.5. TG-DTG

Figure 7 presents the TG-DTG analysis of 7 d AABS samples. Three major endothermic peaks appear in the DTG curves, corresponding to the dehydration of C–A–S–H gels (50–130 °C), the decomposition of AFm phases (150–200 °C), and the decomposition of calcite (810–860 °C) [36,37]. The AFm-related peak can be attributed to the presence of hemicarboaluminate, as confirmed by the XRD patterns of 7 d AABS samples. Among all samples, ASK10 exhibited the highest mass loss in the C–(A)–S–H region, indicating the formation of more C–(A)–S–H gels. The AFm peak also increased with KH-550 addition, suggesting enhanced formation of AFm phases. Compared with ASK0, the mass loss of AABS samples increased with KH-550 dosage up to 1.0 wt.%, reflecting the promoting effect of KH-550 on hydration. This enhancement can be attributed to the hydrolysis of KH-550, which generates silanol groups that facilitate nucleation and growth of C–(A)–S–H gels and AFm phases. However, further increasing the KH-550 content beyond 1.0 wt.% did not significantly increase the mass loss, implying that excessive KH-550 is less effective in stimulating additional hydration product formation. The TGA curves also show that ASK10 exhibited the highest mass loss, indicating that 1.0 wt.% KH-550 is the optimal dosage.

Figure 7.

TG-DTG results of the 7 d AABS samples.

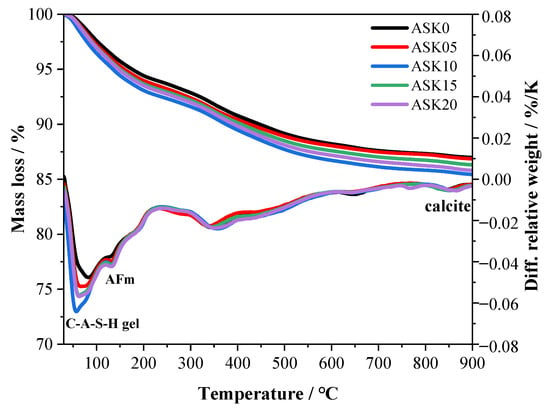

3.6. MIP

Figure 8a depicts the pore structure of AABS samples. The pore structure of the cured AABS, which critically influences its strength and durability, was quantitatively analyzed using MIP. The pore size distribution curves of all samples display two primary peaks, corresponding to gel pores (<10 nm) and capillary pores (10–100 nm). The addition of KH-550 caused a pronounced upward shift in the first peak, with the maximum increase observed for ASK10 at 35.7%, indicating that KH-550 refines the pore structure and increases the proportion of gel pores. A higher fraction of gel pores implies enhanced formation of hydration gels during alkali activation of slag and expansive soils. Meanwhile, increasing the KH-550 dosage led to a shift of the second peak, around 23 nm, toward smaller pore sizes and a gradual decrease in intensity. At 2.0 wt.% KH-550, the second peak nearly disappeared, suggesting substantial refinement of the capillary pore structure. This effect can be attributed to the silanol groups (Si–OH) generated by KH-550 hydrolysis, which react with Si–OH groups formed during AABS hydration to create Si–O–Si networks, thereby reducing capillary porosity [38,39]. Additionally, KH-550 promotes slag hydration and activates clay minerals, such as montmorillonite, in expansive soils. The hydrolyzed silane molecules form interfacial Si–O–Si bonds with soil particles, enhancing the bonding between gel products and soil and facilitating the filling of internal pores with hydration gels. Figure 8b presents the cumulative pore volume curves, showing that all KH-550-modified samples have lower cumulative pore volumes above 10 nm compared with the control, demonstrating that KH-550 effectively reduces harmful pores and total porosity, thereby improving the compactness and densification of AABS. The MIP analysis confirms that an optimal dosage of KH-550 (1.0 wt.%) effectively refines the pore structure of AABS by increasing the proportion of small gel pores and reducing harmful capillary porosity, leading to a denser matrix.

Figure 8.

Pore size distribution curves of 7 d AABS: (a) pore size distribution, (b) cumulative pore volume.

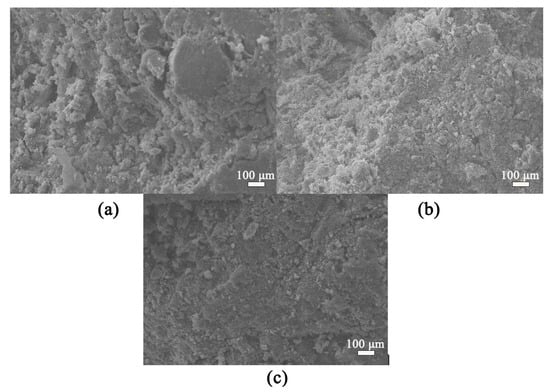

3.7. SEM

Figure 9 presents the SEM micrographs of AABS samples. Figure 9a shows ASK0, which exhibits a loose and porous structure with expansive soil particles partially coated by hydration products, indicating weak interfacial bonding [40,41,42]. Figure 9b,c shows KH-550-modified samples ASK10 and ASK20, respectively, which display a denser and more homogeneous microstructure, with expansive soil particles well encapsulated by hydration gels. This interaction mechanism, where organosilanes enhance the organic-inorganic interface in cementitious systems, is well-documented in prior studies [16,18]. The hydrolyzed Si–OH groups from KH-550 react with hydroxyl groups on clay mineral surfaces, forming Si–O–Si linkages. This reaction enhances microstructural compactness. Consequently, samples with higher KH-550 content show fewer unreacted slag particles and microcracks. This visual observation aligns well with the pore structure refinement quantified by MIP analysis (Section 3.6). These observations indicate that KH-550 effectively improves the interfacial bonding and promotes the formation of a continuous gel network in stabilized expansive soils.

Figure 9.

SEM images of AABS samples: (a) ASK0; (b) ASK10; (c) ASK20.

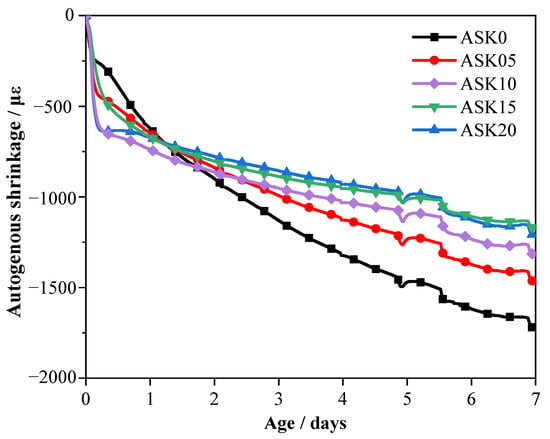

3.8. Autogenous Shrinkage

Figure 10 shows the development of autogenous shrinkage in AABS samples. The sample without KH-550 exhibited a rapid and nearly linear increase during the early stage, reaching 1795 με at 7 d without stabilization. This pronounced shrinkage is mainly attributed to the rapid internal water consumption during early hydration and the high water absorption and swelling behavior of expansive soil minerals, which together lead to increased capillary stress within the matrix. In contrast, addition of KH-550 significantly reduced the autogenous shrinkage of AABS. As the KH-550 content increased from 0.5 wt.% to 2.0 wt.%, shrinkage decreased by approximately 14.9–32.5% relative to ASK0. This improvement is primarily attributed to the hydrolysis of KH-550, which generates silanol groups (–Si–OH) that react with hydroxyl groups on the clay surfaces of expansive soils to form Si–O–Si linkages. These linkages enhance interfacial bonding and establish a denser organic–inorganic network, refining the pore structure and reducing capillary pressure. Furthermore, the accelerated formation of C–(A)–S–H gels fills microvoids, restrains the swelling of expansive soil particles, and increases matrix compactness [40]. Overall, KH-550 effectively mitigates autogenous shrinkage in AABS by strengthening interfacial bonding, refining pores, and promoting hydration gel development.

Figure 10.

Autogenous shrinkage of AABS samples over 7 d.

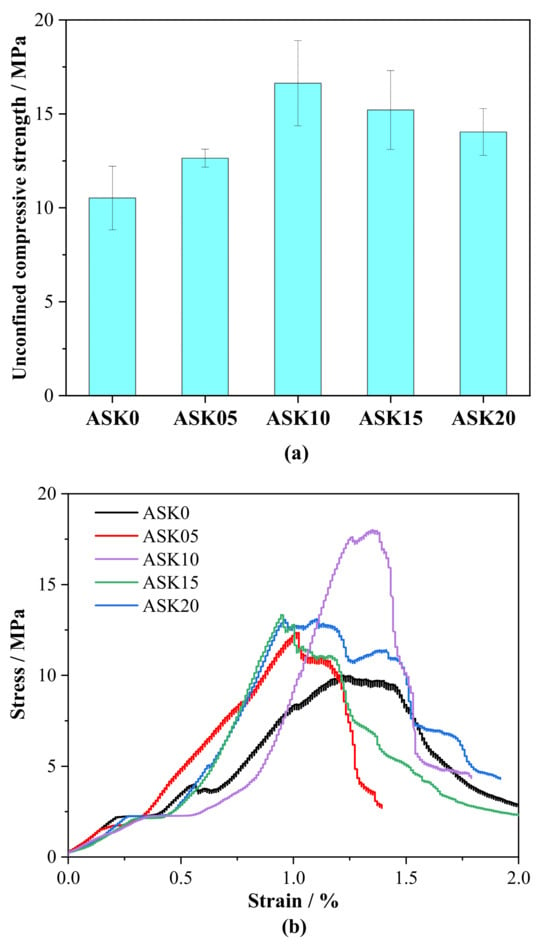

3.9. Unconfined Compressive Strength

3.9.1. Unconfined Compressive Strength for 7 Days

Figure 11a shows the 7 d unconfined compressive strength (UCS) of AABS samples. The addition of KH-550 significantly influenced the UCS, which correlates directly with the observed pore structure changes from MIP analysis. Specifically, 0.5–1.0 wt.% KH-550 increased UCS by 20.2–58.1% compared with the control. This improvement is consistent with the pore structure refinement: the proportion of gel pores (<10 nm) increased by up to 35.7% for ASK10, while the capillary pores (10–100 nm) were substantially reduced, with the second peak around 23 nm shifting toward smaller sizes and nearly disappearing at 2.0 wt.% KH-550. The cumulative pore volume above 10 nm also decreased notably, indicating a reduction in total porosity and harmful pores. These changes enhance the matrix densification, reduce weak points, and promote stronger interparticle bonding, collectively contributing to the observed increase in UCS. At 2.0 wt.% KH-550, a slight decrease in UCS was observed. This may be attributed not only to excessive organic molecules hindering early hydration and C–(A)–S–H gel formation, but also to other mechanisms associated with high KH-550 dosage. These include self-condensation of silanol groups, which can reduce the availability of reactive sites for bonding with slag and soil particles; reduced ion mobility in the pore solution, which may slow down hydration reactions; and surface saturation of particles, limiting further interaction between KH-550 and the matrix. Despite these effects, the quantified pore refinement and porosity reduction still largely explain the overall UCS trends with KH-550 addition, highlighting that moderate dosages (0.5–1.0 wt.%) are most effective for enhancing mechanical performance.

Figure 11.

Unconfined compressive strength of 7 d AABS samples: (a) strength, (b) stress–strain curves.

Figure 11b presents the stress–strain behavior of the AABS samples. The sample with the optimal KH-550 content of 1.0 wt.% exhibited higher peak stress, a steeper elastic slope, and improved post-peak ductility. These results indicate that KH-550 not only enhances UCS and elastic modulus but also increases the material’s ability to accommodate deformation before failure. In contrast, samples with 2.0 wt.% KH-550 showed a slight reduction in peak stress and post-peak ductility, consistent with the observed decline in UCS. This emphasizes the need to optimize KH-550 dosage to balance strength and structural performance.

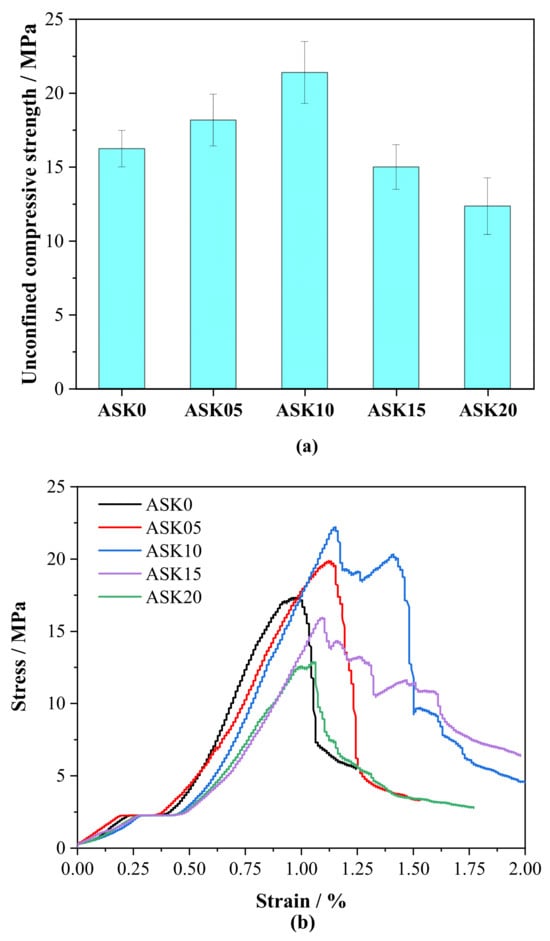

3.9.2. Unconfined Compressive Strength for 10 Days

Figure 12a shows the 7 d UCS of AABS samples after 3 d of water immersion. Moderate addition of KH-550 increased UCS by 11.9–31.8%, which corresponds to the refined pore structure observed in MIP analysis: the proportion of gel pores (<10 nm) increased and capillary pores (10–100 nm) were reduced, leading to lower total porosity and fewer weak points in the matrix. These structural improvements enhance interparticle bonding and matrix cohesion, even under short-term water exposure. At higher dosages (>1.0 wt.%), UCS decreased slightly, likely due not only to excessive organic molecules hindering hydration and partially offsetting the densification effect, but also to self-condensation of silanol groups, reduced ion mobility in the pore solution, and surface saturation of particles, which collectively limit further interaction between KH-550 and the matrix. Figure 12b presents the corresponding stress–strain curves, which further confirm these trends. Samples with optimal KH-550 content exhibited higher peak stress and more ductile post-peak behavior, reflecting improvements in elastic modulus and the ability of the material to accommodate deformation prior to failure. Samples with 0.5–1.0 wt.% KH-550 exhibited higher peak stress and a more ductile post-peak response, indicating that moderate KH-550 improves both the material’s load-bearing capacity and its ability to accommodate deformation. In contrast, samples with KH-550 content above 1.0 wt.% showed a lower peak stress and reduced post-peak ductility, consistent with the observed decrease in unconfined compressive strength.

Figure 12.

Unconfined compressive strength of 7 d AABS samples after 3 d water immersion: (a) strength, (b) stress–strain curves.

3.9.3. Unconfined Compressive Strength for Wet–Dry Cycles

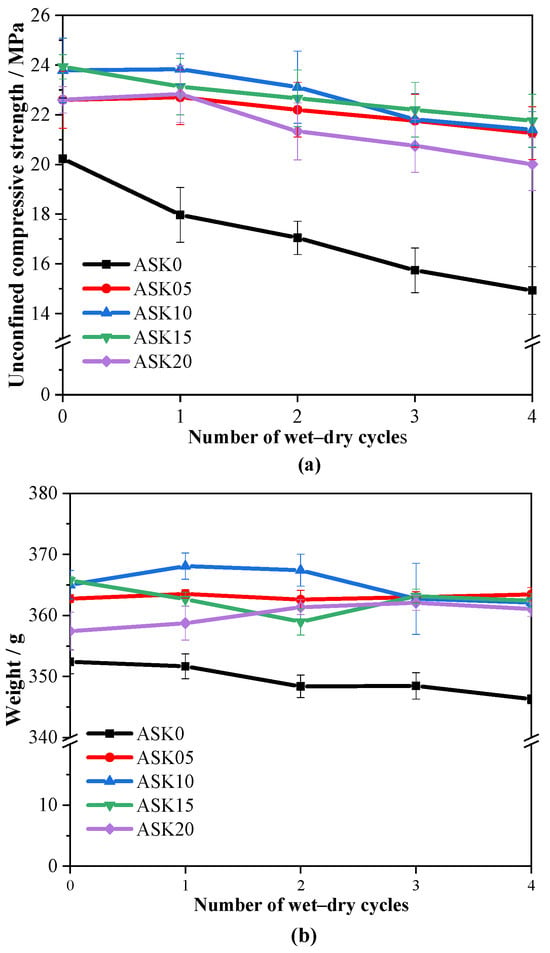

Figure 13a presents the UCS of 28 d AABS samples after four wet–dry cycles. The control sample without KH-550 exhibited a decrease in UCS from 20.23 MPa to 14.93 MPa after the cycles, showing an approximately linear reduction, indicating that unmodified AABS is prone to strength loss under wet–dry cycling. In contrast, KH-550-modified AABS samples demonstrated a UCS increase of 11.7–18.3% compared with ASK0. This improvement is consistent with the refined pore structure observed in MIP analysis, where an increased proportion of gel pores (<10 nm) and reduced capillary pores (10–100 nm) lower the total porosity and reduce weak points, resulting in a denser and more cohesive microstructure. The trend aligns with that observed for the 7 d UCS, suggesting that KH-550 continuously reinforces interparticle bonding and optimizes pore structure throughout curing and cyclic exposure. After four wet-dry cycles, the UCS of KH-550-modified AABS remained largely stable. In contrast, the unmodified sample (ASK0) suffered a significant strength loss of 2.59 MPa. This contrast clearly demonstrates that KH-550 modification enhances the durability of AABS under cyclic environmental stress. These findings indicate that KH-550-modified AABS can effectively stabilize expansive soils, preserving structural integrity and mechanical performance under long-term environmental stress, offering a reliable approach for sustainable soil improvement.

Figure 13.

Effects of four wet–dry cycles on 28 d AABS samples: (a) unconfined compressive strength, (b) Weight.

Figure 13b shows the mass of 28 d AABS samples after four wet–dry cycles. All samples exhibited gradual mass loss with increasing cycles, reflecting microstructural damage and partial surface scaling during repeated wetting and drying. The control sample without KH-550 showed the most significant reduction, with mass decreasing from 352.4 g to 346.3 g after four cycles, corresponding to a cumulative loss of approximately 1.7%. In contrast, KH-550-modified samples retained a more stable mass, with total losses below 1.0 wt.%, indicating that the silane treatment enhances structural integrity and water resistance.

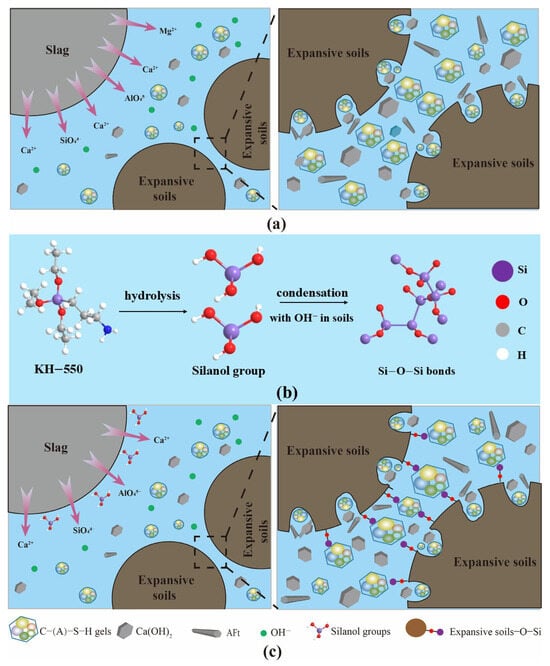

3.10. Mechanism Analysis of KH550 Modified AABS Samples

Figure 14a illustrates the mechanism of AABS. The solidification process can be divided into three stages: dissolution, gel formation, and soil consolidation. Under alkaline conditions, layered silicate minerals, such as montmorillonite in expansive soils, partially dissolve, releasing active Si and Al species. Simultaneously, Ca2+, , and ions are released from the slag and re-polymerize to form C–(A)–S–H gel. Slag and soil particles primarily form a skeleton through physical contact and filling, resulting in a relatively loose structure with limited early hydration products and mechanical improvement. Figure 14b shows the reaction process of KH-550 under alkaline conditions. The ethoxy groups of KH-550 hydrolyze to form silanol groups (Si–OH), which can condense to form Si–O–Si networks and chemically bond to hydroxyl groups on mineral surfaces, thereby enhancing interfacial adhesion and dispersion. These reactive sites facilitate further interactions with expansive soil and alkali-activated slag.

Figure 14.

Mechanistic illustration of KH-550-modified AABS samples: (a) AABS mechanism; (b) Hydrolysis of KH-550; (c) KH-550 modification mechanism in AABS.

Figure 14c illustrates the mechanism of KH-550 modification in AABS. After modification, the solidification mechanism shifts from being primarily governed by physical filling to a synergistic combination of chemical crosslinking and physical filling. The hydrolyzed silanol molecules adsorb onto soil and slag surfaces, forming a thin film that regulates the hydration rate and delays early gel formation. Simultaneously, silanol groups condense with dissolved Si and Al species, generating additional Si–O–Si networks that integrate with C–A–S–H gel. The silanol groups chemically bond with surface hydroxyls of soil particles, while the amino groups interact with hydration products, establishing chemical crosslinks between soil particles. Physical filling remains active but now works synergistically with chemical crosslinking, producing a denser structure, a more uniform gel distribution, and more complete pore filling, ultimately forming an organic–inorganic hybrid network. As a result, AABS exhibits improved workability, prolonged setting times, and enhanced unconfined compressive strength and durability. At higher KH-550 dosages (>1 wt.%), the modification effect is slightly diminished. This reduction may be attributed to self-condensation of silanol groups, which decreases their availability for bonding with soil and slag; reduced ion mobility in the pore solution, which can slow hydration reactions; and surface saturation of particles, which limits further interaction between KH-550 and the matrix. These factors partially offset the densification and crosslinking effects, explaining the modest decrease in mechanical performance observed at higher dosages.

4. Conclusions

The effects of γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (KH-550) on alkali-activated binder stabilized expansive soils (AABS) are mainly related to its regulation of early hydration through interactions with both slag and expansive soil particles. KH-550 forms chemical bonds with surface hydroxyl groups on clay minerals and promotes the formation of Si–O–Si linkages, which delay early hydration, extend initial and final setting times by up to 89%, and enhance fluidity by 6–27%, thereby improving workability and ensuring uniform binder distribution. These interactions also promote the nucleation and growth of C–(A)–S–H gels, refine the pore structure by increasing gel pores and reducing capillary porosity, and densify the matrix, effectively mitigating the swelling and shrinkage of expansive soils. Consequently, the mechanical performance of AABS are significantly enhanced, with autogenous shrinkage reduced by up to 32.5%, 7 d unconfined compressive strength increased by 58.1% at an optimal dosage of 1.0 wt.%, short-term water resistance improved with an 11.9–31.8% unconfined compressive strength increase after 3 d of water immersion, and long-term durability under wet–dry cycling enhanced, showing an 11.7–18.3% higher 28 d unconfined compressive strength compared with unmodified samples.

5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

This study confirms the effectiveness of KH-550 in improving AABS-treated expansive soil, yet several limitations remain.

- Soil Specificity: The tested expansive soil was sourced from Guangxi, China, and was mainly composed of montmorillonite and illite. The applicability of KH-550 to soils with different clay mineralogy (e.g., kaolinite, chlorite) or cation exchange capacities requires further verification.

- Dosage Range: The KH-550 content explored (0–2.0% of total solids) identified 1.0% as optimal. However, extending the dosage range may uncover additional thresholds or adverse effects such as excessive retardation or weak interfacial layers.

- Environmental Conditions: All tests were performed under controlled laboratory conditions. The long-term behavior of KH-550-modified AABS under realistic environmental stresses (freeze–thaw, carbonation, wetting–drying cycles, UV exposure) remains uncertain.

Future studies should therefore:

- (i)

- assess the method on a wider range of expansive soils;

- (ii)

- investigate long-term durability and microstructural evolution under field-like conditions; and

- (iii)

- perform life-cycle assessments to evaluate environmental and economic feasibility at scale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F. and Y.W.; methodology, S.F. and P.C.; software, Q.W.; validation, C.Z., Y.W. and Q.W.; formal analysis, C.Z.; investigation, C.W.; resources, C.W.; data curation, C.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.F. and Y.W.; visualization, P.C.; supervision, Q.W.; project administration, P.C.; funding acquisition, S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Guangxi Key Research and Development Project, grant number 2021AB17097, and the Guangxi Key Research and Development Program, grant number 2024AB24040.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yongke Wei was employed by the company Guangxi Transportation Design Group Co., Ltd. Author Shouzhong Feng was employed by the company Anhui Zhongyi New Materials Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Huang, K.; Xu, G.; Yan, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, D.; Cai, G.; Sun, Y.; Chen, R.; Pu, S.; Shi, X. Study on the optimization and performance of expansive soil stabilized by alkali-activated fly ash-phosphogypsum using response surface methodology. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 113, 114032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Vanapalli, S.K. Predicting the compression index of expansive soils with hybrid machine learning approaches. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 162, 112579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Gu, L.; Liu, S. Microstructural and mechanical properties of marine soft clay stabilized by lime-activated ground granulated blastfurnace slag. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 103, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manigniavy, S.A.; Bouassida, M. Expansive soil characterization: CC/CS ratio method. Geodata AI 2025, 25, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, W.; Wang, B.; Zhan, X.; Zuo, J.; Shan, Y.; Han, S.; Wang, T. Synergistic Effects of Cement–Silica Fume Composite on Expansive Soil Stabilization: Mechanisms, Microstructure, and Durability. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsegaye Woldesenbet, T.; Vieira, C.S. Experimental Study on Stabilized Expansive Soil by Blending Parts of the Soil Kilned and Powdered Glass Wastes. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 12, 9645589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamei, T.; Ahmed, A.; Ugai, K. Durability of soft clay soil stabilized with recycled Bassanite and furnace cement mixtures. Soils Found. 2013, 53, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhendro, B. Toward Green Concrete for Better Sustainable Environment. Procedia Eng. 2014, 95, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Wang, L.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z. Autogenous shrinkage mitigation effect of superabsorbent polymers on alkali-activated GGBFS-FA binary binder without additional water: Performance, microstructure and mechanism. Cem. Concr. Res. 2026, 199, 108058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, P.; Chan, H.-K.; Han, Z.; Liu, B.; Lei, L. Design of a novel starch-modified MPEG PCE for enhanced slump retention in alkali-activated slag binder. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2026, 165, 106358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraki, H.; Shariatmadari, N.; Ghadir, P.; Jahandari, S.; Tao, Z.; Siddique, R. Clayey soil stabilization using alkali-activated volcanic ash and slag. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2022, 14, 576–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Li, C.; Liu, S. Alkali-Activated Ground-Granulated Blast Furnace Slag for Stabilization of Marine Soft Clay. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2015, 27, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruschi, G.J.; dos Santos, C.P.; de Araújo, M.T.; Tonatto Ferrazzo, S.; Veloso Marques, S.F.; Consoli, N.C. Green Stabilization of Bauxite Tailings: Mechanical Study on Alkali-Activated Materials. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-G.; Kou, S.-C.; Poon, C.-S.; Dai, J.-G.; Li, Q.-Y. Influence of silane-based water repellent on the durability properties of recycled aggregate concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013, 35, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Zhong, Y.; Li, Z.; Lei, F.; Jiang, Z. Study on alkylsilane-incorporated cement composites: Hydration mechanism and mechanical properties effects. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 122, 104161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.-M.; Liu, H.; Lu, Z.-B.; Wang, D.-M. The influence of silanes on hydration and strength development of cementitious systems. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 67, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Shao, H.; Li, B.; Li, Z. Influence of silane on hydration characteristics and mechanical properties of cement paste. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 113, 103743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, L.; Liu, K.; Zheng, A.; Liu, J. Investigation on waterproof mechanism and micro-structure of cement mortar incorporated with silicane. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 239, 117865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, J. An experimental investigation of hydration mechanism of cement with silicane. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 166, 684–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Le, H.T.N.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M.-H. Effects of silanes and silane derivatives on cement hydration and mechanical properties of mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 129, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Švegl, F.; Šuput-Strupi, J.; Škrlep, L.; Kalcher, K. The influence of aminosilanes on macroscopic properties of cement paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 2008, 38, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Li, J.; Zhao, C.; Tan, W.; Li, X.; Chen, P. Enhancing the performance of alkali-activated slag using KH-550 as a multi-functional admixture. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 2, e03434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C191; Standard Test Methods for Time of Setting of Hydraulic Cement by Vicat Needle. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- ASTM C1437; Standard Test Method for Flow of Hydraulic Cement Mortar. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2007.

- ASTM C1698; Standard Test Method for Autogenous Strain of Cement Paste and Mortar. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2009.

- ASTM C1702; Standard Test Method for Measurement of Heat of Hydration of Hydraulic Cementitious Materials Using Isothermal Conduction Calorimetry. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM C192; Standard Practice for Making and Curing Concrete Test Specimens in The Laboratory. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- Chang, J.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Wang, L.; Jiang, J.-Q.; Guo, J.-X. Influence of acid rain climate environment on deterioration of shear strength parameters of natural residual expansive soil. Transp. Geotech. 2023, 42, 101017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Wang, L.; Jiang, J.-Q. Water–soil chemical mechanism and soil structural stability of expansive soil under the action of acid rain infiltration. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Tao, Y.; Van Tittelboom, K.; De Schutter, G. Rheological and mechanical properties of 3D printable alkali-activated slag mixtures with addition of nano clay. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 139, 104995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Yu, Q.L.; Dainese, E.; Brouwers, H.J.H. Autogenous and drying shrinkage of sodium carbonate activated slag altered by limestone powder incorporation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 153, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xin, C.; Li, J.-s.; Wang, P.; Liao, S.; Poon, C.S.; Xue, Q. Using hazardous barium slag as a novel admixture for alkali activated slag cement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 125, 104332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, T.; Yan, C.; Wang, J. Expansive Soil Stabilization Using Alkali-Activated Fly Ash. Processes 2023, 11, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, A.; Ray, I.; Halabe, U.B.; Unnikrishnan, A.; Dawson-Andoh, B. Characterizations and Quantitative Estimation of Alkali-Activated Binder Paste from Microstructures. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2014, 8, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Gao, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhuang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z. Sulphate resistance of one-part geopolymer synthesized by calcium carbide residue-sodium carbonate-activation of slag. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 242, 110024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Fu, C.; Yang, G. Influence of dolomite on the properties and microstructure of alkali-activated slag with and without pulverized fly ash. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 103, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobasher, N.; Bernal, S.A.; Provis, J.L. Structural evolution of an alkali sulfate activated slag cement. J. Nucl. Mater. 2016, 468, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Tan, X.; Zhang, M.; Sun, Z. Properties and microstructure of self-waterproof metakaolin geopolymer with silane coupling agents. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 342, 128045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, H.; Wang, X.; Gao, J. Effects of silane on reaction process and microstructure of metakaolin-based geopolymer composites. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fan, C.; Wang, B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z. Workability, rheology, and geopolymerization of fly ash geopolymer: Role of alkali content, modulus, and water–binder ratio. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 367, 130357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, B.; Feng, J. Relationship between fractal feature and compressive strength of concrete based on MIP. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 322, 126504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, B.; Chang, J. Adsorption behavior and solidification mechanism of Pb(II) on synthetic C-A-S-H gels with different Ca/Si and Al/Si ratios in high alkaline conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 493, 152344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).