Abstract

Indoor environmental quality (IEQ), influenced by ventilation and acoustic conditions, directly affects human health and comfort. Existing studies often concern either ventilation or sound insulation alone, neglecting the impact of the trickle ventilator's internal structure and its combination with windows on overall performance. This study introduced a double-chamber model to quantify the ventilation performance of three trickle ventilators using tracer-gas-decay and pressure-difference methods. We calculated the flow coefficient () and flow exponent () to reveal differences in pressure sensitivity, with trickle ventilator TV2 showing the highest-pressure sensitivity ( = 1.34, = 0.89). The weighted sound reduction index () and weighted sound insulation index for traffic-noise correction () were measured, showing trickle ventilators TV1-1 and TV1-2, and TV2 were 29 dB, 30 dB, and 34 dB, respectively. And the sound insulation and ventilation performance of window-trickle ventilator combinations were analyzed. Trickle ventilators could enhance acoustic performance for low-insulation windows but reduce it for high-insulation windows. The study also quantitatively balanced ventilation and acoustics. This research provides data support and theoretical guidance for the synergistic optimization of ventilation and sound insulation in building environments and provides guidance on ventilation and noise control strategies suited to different floor levels and outdoor noise environments.

1. Introduction

Indoor environmental quality (IEQ) is a key determinant of occupant health, living comfort, and work performance [1]. Both acoustic and indoor ventilation markedly influence IEQ, and poor IEQ can lead to sick building syndrome (SBS) [2].

Long-term exposure to noise can lead to hearing loss, cardiovascular disease (CVD), depression and anxiety, sleep disorders, and other health problems [3,4]. For every 10 dB increase in road traffic noise, the risk of CVD increases by 3.2% [5], depression by 4%, and anxiety by 12% [6]. To address the issue of noise pollution, the World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that the noise level in bedrooms at night should be controlled below 30 dB to protect the sleep quality of residents [7]. The indoor noise limits of residential buildings at night in European countries are not uniform. Zaporozhets generally suggested that the indoor noise of residential buildings at night should be controlled at around 30 dB or refer to the recommendations of the WHO [8]. The ‘Code for Design of Sound Insulation in Buildings’ of China stipulates that the design index of noise for residential buildings at night is 37 dB, and the limit value for some high-standard residential buildings or buildings with special purposes can be even lower [9]. It can be seen that compared with the limits set by the WHO and Europe, the noise limit for residential buildings at night in China is relatively high. This also reflects the relatively high level of environmental noise in Chinese cities, thereby highlighting the necessity of evaluating and optimizing the sound insulation performance of buildings.

The building envelope, including exterior walls, windows, and doors, serves as a key element of sound insulation [10]. Among these, windows are often the weakest part [11], making their sound insulation performance critical.

In addition to providing sound insulation, windows can enable natural ventilation, regulate indoor airflow, and improve indoor air quality [12,13]. The WHO, Europe and China have all established relevant standards for IAQ. For example, according to the WHO’s ‘Housing and Health Guidelines’ [14], the indoor CO2 concentration should be kept below 1000 ppm. Exceeding this level usually indicates insufficient ventilation. The EN 16798-1 standard in Europe recommends setting the increment of CO2 between 400 and 1000 ppm [15] to maintain good indoor air quality. The ‘Indoor Air Quality Standard’ of China [16] stipulates that the limit value of CO2 is 1000 ppm. Appropriate ventilation is crucial for meeting these IAQ limits, but opening windows for ventilation inevitably brings noise input. To avoid external noise, people often keep windows closed, sacrificing ventilation. Therefore, how to balance sound insulation and ventilation remains an urgent challenge.

Trickle ventilators, also known as background ventilators [17], are often used to balance ventilation and acoustic comfort. A trickle ventilator is defined as a small openings that allow controllable indoor-outdoor air exchange [18,19]. Unlike wall-mounted ventilation systems, which typically require damaging the wall structure, trickle ventilators can be fitted directly into the window frame [20]. They are easy to install, cost-effective, and balance ventilation and sound insulation.

Trickle ventilators can provide effective ventilation [21,22], reduce ventilation heat losses [18], and simultaneously meet indoor sound insulation requirements [23]. The tracer gas decay method is widely used to quantify the ventilation efficiency of trickle ventilators [21,24]. However, these findings are often influenced by climate conditions and building types, which may also result in poor reproducibility of experimental outcomes. Trickle ventilators play a crucial role in maintaining indoor air quality and acoustic comfort, two key components of indoor environmental quality (IEQ) that directly influence occupants’ health and wellbeing.

Several studies have investigated trickle ventilators. In terms of ventilation, computational simulations have examined the effect of opening size on ventilation performance [25], predicted ventilation performance in dwellings with varying airtightness [18], and assessed ventilation when trickle ventilators are coupled with exhaust fans [26]. However, these studies have not considered how the internal structures of trickle ventilators influence the ventilation rate. Regarding sound insulation, the acoustic characteristics of trickle ventilators and their performance when combined with wooden frames were measured [23]. In practice, window frames are more commonly made of aluminum or polymers such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and unplasticized polyvinyl chloride (UPVC) [27], and the proposed integrated prediction models cannot accurately estimate the sound insulation performance of PVC frames. Moreover, since 70–80% of the visible window area is glass, and glass contributes more significantly to sound insulation [28], it is crucial to consider changes in the sound insulation performance of trickle ventilators when combined with different glass types of windows. Nevertheless, research on the combined sound insulation performance of trickle ventilators with various glass types of windows remains limited. Given their dual capability to provide both ventilation and noise control, trickle ventilators hold considerable potential, making a quantitative evaluation of their ventilation and sound insulation performance particularly important.

To address the above limitations, this study introduced the double-chamber method, applying a background pressure difference and quantifying the ventilation rate of trickle ventilators using the tracer gas method. The flow coefficient was measured and interpreted to reflect how internal structures influence ventilation rate. In addition, the sound insulation performance of trickle ventilators was quantitatively assessed through both the weighted sound reduction index and the sound insulation spectrum performance. By focusing on different glass types of windows, the study calculated the sound insulation under the combination of windows and trickle ventilators, while also quantifying changes in ventilation rate and analyzing the relationship between ventilation and sound insulation. These findings provide scientific support for establishing selection criteria for trickle ventilators and for optimizing their ventilation and sound insulation performance in practical building applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Environment

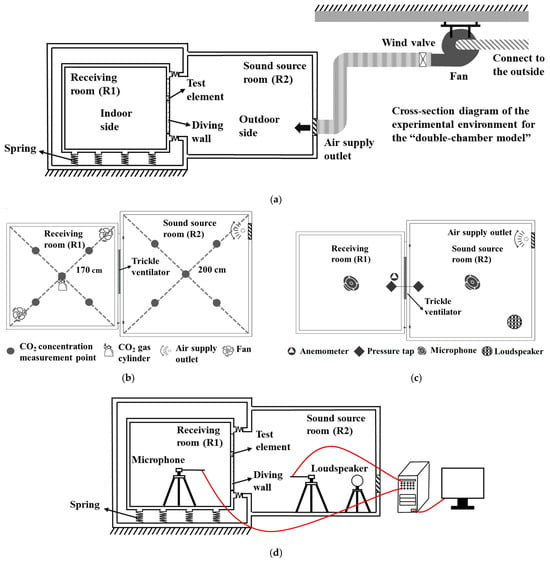

2.1.1. Ventilation Performance Test

In this study, we introduced the double-chamber method (Figure 1a) to effectively isolate uncontrollable external factors, such as wind speed and temperature difference. The experimental procedure was as follows: the trickle ventilator was installed in the sound insulation room, where the receiving room is a “room-in-room” structure. Where the sound source room (R1) served to simulate the outdoor environment, and the receiving room (R2) acted as the tracer gas source room. Both rooms were isolated from the external environment to eliminate the influence of outdoor wind and temperature differences, ensuring that any differences in ventilation rate measured by the tracer gas decay method were solely due to the characteristics of the trickle ventilator. According to the standard ‘Ventilators for windows and doors of building’ [19], the ventilation measurement of natural ventilators requires maintaining a pressure difference of 10 Pa, which was achieved using a fan connected to the sound source room. The layout [24,29] of the sound-insulated rooms and the distribution of measurement points are shown in Figure 1b. During testing, the trickle ventilator was installed in the wall between R1 and R2, with the indoor side facing R2 and the outdoor side facing R1. During the experiment, the fan continuously supplied air to R1, maintaining a stable pressure difference of 10 Pa across the ventilator. CO2 tracer gas was then released in R2, and when the concentration reached above 3000 ppm, the release was stopped. A fan was used to mix the CO2 evenly in the room for 3–5 min, after which the fan was turned off. The CO2 concentration, temperature, and humidity were recorded until the CO2 concentration decayed to a stable level. After one measurement cycle (from turning off the fan to reaching stable decay), the measurement was completed.

Figure 1.

Experimental test layout diagram. (a) Cross-sectional diagram of laboratory; (b) “double-chamber model” equipment layout diagram; (c) layout plan of equipment for measuring and sound insulation; (d) cross-sectional diagram of sound insulation (The red line indicates that the sound data collected by the loudspeaker will be transmitted to the computer in real time.).

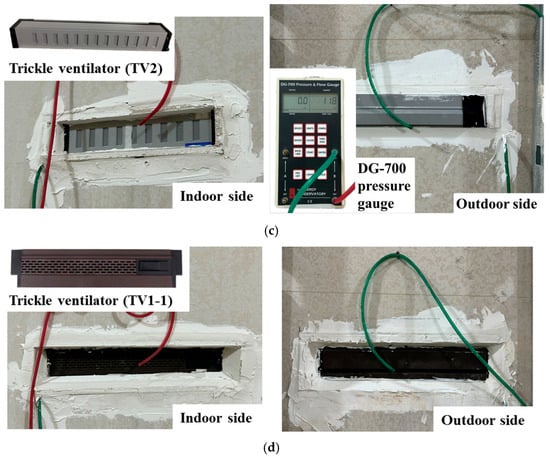

To further analyze the factors causing differences in the ventilation rates of trickle ventilators, it is necessary to measure the intrinsic flow coefficient () of the trickle ventilators. The flow coefficient () was measured in accordance with the standard ‘Technical requirements for ventilated sound insulating windows’ [30]. For each trickle ventilator, five different pressure differences (10 Pa, 20 Pa, 30 Pa, 40 Pa, and 50 Pa) were selected, and the average air velocity was measured under each pressure difference. The specific procedure is as follows (Figure 1c): the supply air device in R1 was turned on, and by adjusting the frequency of the fan, the supply speed of the fan can be changed to establish and maintain the target pressure difference across the trickle ventilator. Once the pressure difference stabilized, a DG-700 pressure gauge [31] was used to record the pressure difference across the trickle ventilator, and an anemometer [32] was used to measure the air velocity at the indoor inlet side of the trickle ventilator. Each measurement was repeated six times to obtain an average value, and the ventilation rate was subsequently calculated to evaluate the trickle ventilator’s performance.

2.1.2. Sound Insulation Performance Testing Experiment

The airborne sound insulation performance tests of the trickle ventilators (TV1-1, TV1-2, and TV2) (Figure 1d) were conducted at the Acoustics Laboratory of the School of Architecture of Tsinghua University (It has been recognized by the China National Accreditation Service for Conformity Assessment). The experimental process was strictly in accordance with ‘Acoustics—Laboratory measurement of sound insulation of building elements—Part 2: Measurement of airborne sound insulation’ [33]. We independently tested the trickle ventilator in a standardized heavy-duty test wall to obtain its inherent sound insulation. This test was carried out strictly in accordance with the standardized measurement specifications of the element-normalized sound pressure level difference and for sound insulation in ISO 10140-2:2021 [33], including the installation of walls around and the sealing requirements. The laboratory consists of two adjacent reverberation chambers without rigid connections between them, in order to prevent flanking transmission. It is noted that zero flanking transmission can be achieved when no rigid connections exist between the two rooms. Since the dimensions of the trickle ventilator were much smaller than the opening size of the test opening, a diving wall with sufficiently high sound insulation was constructed at the opening, the construction of the wall adopts an air sound weighting sound insulation value of ≥50 dB, and strictly complies with the relevant provisions in the ISO10140 standard [33], and the trickle ventilators were installed on it for testing. Measurements were carried out at the 1/3-octave bands covering the frequency range from 100 Hz to 5000 Hz.

The main purpose of this study is to obtain the inherent sound insulation performance of the trickle ventilator as an independent component. Therefore, the window ventilator was not combined with the specific window frame or sash for installation and testing. If a combined test is conducted, the obtained results will inevitably be affected by factors such as window type, frame stiffness, glass structure and sealing method, and it is impossible to accurately distinguish the acoustic performance of the trickle ventilator. Therefore, in accordance with ‘Acoustics—Laboratory measurement of sound insulation of building elements—Part 2: Measurement of airborne sound insulation’, we independently tested the ventilator in a standardized heavy-duty test wall to obtain its inherent sound insulation [33]. This test was carried out strictly in accordance with the standardized measurement specifications of the element-normalized sound pressure level difference. and for sound insulation in ISO 10140-2:2021, including the installation of walls around and the sealing requirements. To further discuss the combined sound insulation effect of ventilators in practical application scenarios, this study subsequently adopted a combined calculation method based on the transmission coefficient, coupling the independently tested sound insulation performance of trickle ventilators with those of windows with different glass configurations, thereby evaluating the overall sound insulation performance of the combined components. This process not only ensures the independence and comparability of the sound insulation performance of the ventilator body, but also allows for performance prediction of the real combined components.

2.2. Description of Trickle Ventilator Samples

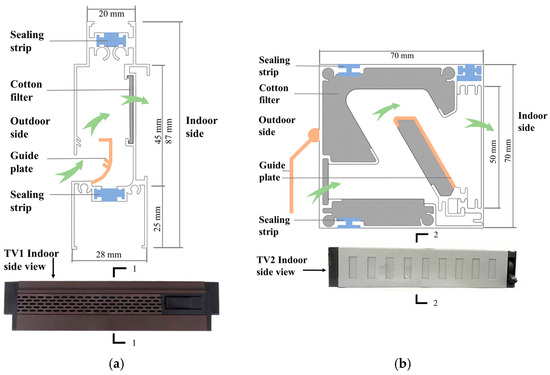

The trickle ventilators tested in this study are commercially available products commonly used in residential buildings in mainland China, particularly in newly installed or renovated windows. The selection of samples was based on the two major internal structural categories found in the market: the ‘straight-channel’ type and the ‘labyrinth’ type. The straight-channel type features a relatively short and linear airflow path, whereas the labyrinth type has a longer, folded, and more tortuous airflow pathway. To help readers evaluate the representativeness of the selected samples, commonly used trickle ventilator configurations under these two structural categories are summarized in Table A1.

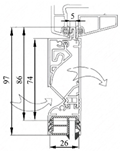

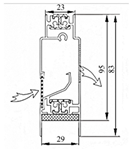

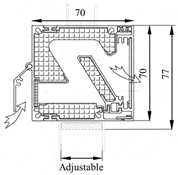

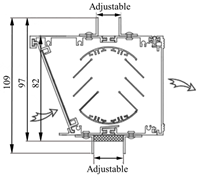

For each of the two structural types, one representative model was chosen, and for one type, products from two different manufacturers were included in the tests. Three samples selected for this research were tested and classified into two types based on their internal structure: TV1 and TV2. Among them, the two TV1 samples have the same internal structures but originate from different manufacturers, denoted as TV1-1 and TV1-2. TV1 has dimensions of 37.8 × 8.7 × 2.8 cm, with a geometric free opening area of 23.4 cm2 [17]. A guide plate is installed at the inlet, and a cotton filter is embedded before the outlet for filtration and sound absorption (Figure 2a). TV2 has dimensions of 34.3 × 7.0 × 7.0 cm, with a geometric free opening area of 42.6 cm2. Its internal structure features a “Z”-shaped cross-section, and a cotton filter is installed around the perimeter for air filtration, sound absorption, and thermal insulation (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Vertical-sectional view of the tickle ventilator structure and schematic diagram of the indoor side. (a) TV1; (b) TV2. (The green arrow in the picture indicates the direction of the airflow. The attached picture shows the outside of the ventilator, and it is the side facing the room. The schematic diagram shown in the figure indicates the horizontal installation status of the trickle ventilator).

2.3. Quantification of Sound Insulation and Ventilation Performance

2.3.1. Tracer Gas Decay Method

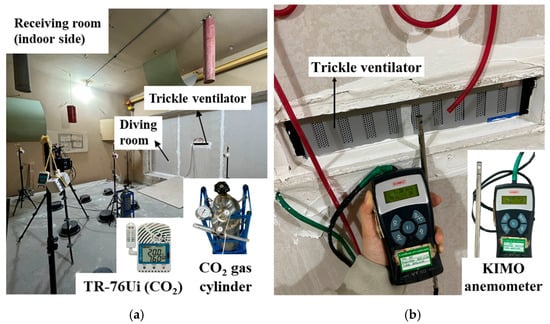

The ventilation rate of the trickle ventilators was measured using the tracer gas decay [29] method (Figure 3a). The specific operational steps of the experiment mainly refer to the Chinese standard for public place hygiene inspection, whose methodological principle is consistent with the tracer gas decay approach described in the international standard ISO 12569 [34]. The calculation formula of the tracer gas decay method for measuring ventilation rate is based on the mass conservation equation [35]:

where denotes the room volume (m3), denotes the time (h), denotes the tracer gas concentration in R2 at time (ppm), denotes the ventilation rate measured using the tracer gas method (m3·h−1), denotes the background tracer gas concentration in R2 (ppm), denotes the initial tracer gas concentration in R2 at = 0 (ppm), and denotes the emission rate of the tracer gas (m3·h−1). When using the tracer gas decay method, the gas emission rate is zero ( = 0), and the nonlinear regression equation can be obtained from Equation (1):

where denotes the air change rate (h−1), i.e., . Taking the logarithm of Equation (2):

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of testing and equipment installation. (a) Tracer gas decay method setup in the receiving room; (b) wind speed measurement; (c) wind pressure measurement; (d) trickle ventilator installation.

CO2 was selected as the tracer gas in this study. Measurements were conducted using a TR-76Ui [36], which can simultaneously record CO2 concentration, temperature, and humidity.

To evaluate the distribution of CO2 within the room, the non-uniformity coefficient () was introduced. It is defined as the ratio of the standard deviation of concentrations at all sampling points to the mean concentration at the same time. When < 2%, the CO2 distribution in the room is considered uniform [37].

In this study, a multi-point decay method was employed [35], in which multiple points within the measurement period were used, and the was determined using the least-squares method:

In the double-chamber method tests, each trickle ventilator was tested in three repeated experiments. The starting point of the decay curve was selected at a CO2 concentration of 3000 ppm [35], with a measurement interval of 1 min and a measurement period of 35 min [24,35]. Data points within the decay period were substituted into Equation (5) to calculate the air change rate ().

2.3.2. Determination of the Flow Coefficient (Cd)

The following (orifice outlet velocity) equation can be derived using the indoor-outdoor or windward-leeward pressure difference (Figure 3b,c) to determine the air velocity on the indoor side of the trickle ventilator [24]:

where denotes the air velocity (m·s−1), denotes the discharge coefficient of the opening, denotes the indoor-outdoor pressure difference (Pa) and denotes the air density (kg·m−3). depends on the geometry and the Reynolds number of the flow, and is dimensionless.

The ventilation rate can be calculated using the following equation:

where denotes the ventilation rate of the trickle ventilator (m3·h−1), denotes the geometric free opening area of the window ventilator (cm2), and denotes the average air velocity at the outlet of the trickle ventilator (m·s−1).

Through pressure difference experiments, the power-law equation was obtained by performing linear regression using the least-squares method [21,30], from which the flow coefficient was determined:

where denotes the flow coefficient (m3·(s Pa)−1), reflecting the deviation between the actual airflow and the theoretical airflow, and denotes the flow exponent of the opening, representing the sensitivity of the ventilation rate of the trickle ventilator to pressure difference.

Equation (8) can intuitively describe the resistance characteristics of the trickle ventilator [38], as well as the airflow behavior at its opening. From extensive experimental studies, the flow exponent for typical building leakage paths ranges between 0.6 and 0.7 [39].

The mean absolute percentage error () was selected to evaluate the differences in the results between the pressure difference and the tracer gas method [24].

When 10% ≤ < 20%, it indicates that the predictive performance of the two methods is good, and the error is within an acceptable range.

2.3.3. The Element-Normalized Sound Pressure Level Difference ()

Based on the measured average sound pressure levels in the sound source room (R1) and the receiving room (R2) (; unit: dB) (Figure 3d), the element-normalized sound pressure level difference of the trickle ventilator over the full frequency range can be calculated [40]:

where denotes the reference absorption area, set to 10 m2 for laboratory measurements, and is the measured absorption area of R2 (m2).

To accurately assess the sound insulation performance of the element, the weighted normalized sound pressure level difference of the trickle ventilator needs to be calculated according to ISO10140-2 [33]. The standard reference curve and the spectrum adaptation terms for pink noise () and traffic noise () [40] are determined by the following formula:

where denotes the spectrum index ( = 1 or 2; 1 corresponds to spectrum 1 used for the calculation of , and 2 corresponds to spectrum 2 used for the calculation of ); (dB) denotes the weighted normalized sound pressure level difference of the trickle ventilator; denotes the index of 1/3-octave bands covering the frequency range from 100 Hz to 5000 Hz; denotes the sound pressure level of the -th frequency band of the -th reference spectrum as given in the standard, and denotes the element normalized sound pressure level difference at the -th frequency band, reported to 0.1 dB precision.

The values provide a good indication of the performance of the test element and allow for comparison between different components. The values reflect the sound insulation performance of the trickle ventilator under different scenarios, where the adaptation term is applicable to indoor noise environments dominated by mid-to-high frequencies, and the adaptation term is suitable for traffic noise-dominated environments, which typically have a significant low-frequency component. Users can select trickle ventilators based on the type of ambient noise they are exposed to, using as a reference for comparison. Since trickle ventilators are mostly installed on the exterior façades of buildings and road traffic noise exposure in Chinese cities is relatively serious [41], the Section 3 therefore focus only on the sound insulation ratings of the trickle ventilators combined with the adaptation term.

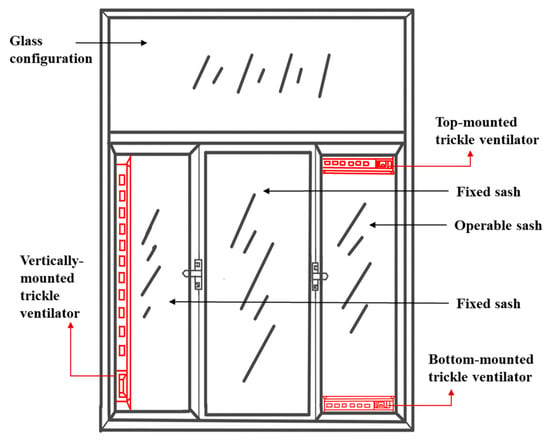

2.3.4. Sound Insulation by Combination of Trickle Ventilator and Windows

In practice, trickle ventilators are rarely used as stand-alone elements; they are typically integrated with windows (Figure A1). Because different elements exhibit varying sound insulation performance across frequencies, and since the calculation of the weighted sound reduction index is based on specific assumptions, the weighted sound reduction index of the “window + trickle ventilator” assembly cannot simply be obtained by adding or subtracting the individual values. Instead, the selection of windows and trickle ventilators should be made based on the optimized overall sound insulation performance across the entire frequency range. In this article, the transmission coefficient τ is defined as the ratio of the radiated by the test element to the other side to the incident on the test element to the sound power. The standardized term used in ISO 10140 to describe the frequency-dependent sound insulation is [33]:

where (dB) denotes the sound reduction index of the test element at different frequencies, denotes the incident on the test element to the sound power, and denotes the radiation by the test element to the other side. The combined sound insulation can then be calculated as:

where (dB) denotes the sound insulation by the combination of trickle ventilator and windows (hereafter referred to as combined sound insulation), denotes the average transmission coefficient, (cm2) denotes the area of the window, denotes the transmission coefficient of the window, (cm2) denotes the area of the trickle ventilator, and denotes the transmission coefficient of the trickle ventilator.

A total of 21 typical window configurations were selected for this experiment, covering the most basic glazing types of windows in modern buildings: single glazing, double glazing, triple glazing, and laminated glazing [42,43]. The selected samples span a sound insulation range of approximately 28–39 dB, which corresponds well to the requirements for exterior windows in residential, office, and public buildings [44]. The window types are listed in Table A2.

In this study, the combined sound insulation of the “window + trickle ventilator” was calculated based on third-octave bands, and the corresponding weighted sound reduction index value was also derived. To facilitate a clearer comparison of the combined sound insulation of different trickle ventilators paired with different window configurations, only the weighted sound reduction index results are presented in the Section 3.

3. Results

3.1. Influencing Factors of the Tracer Gas Method

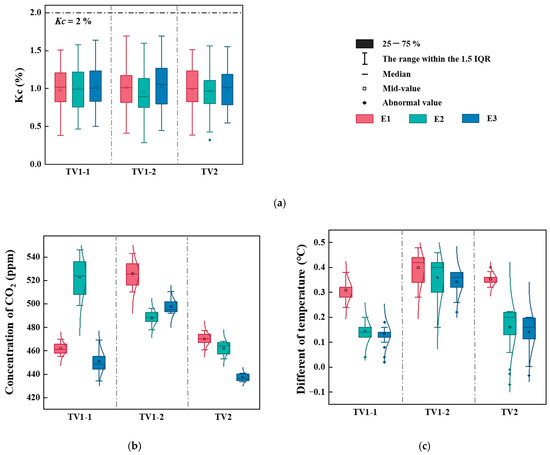

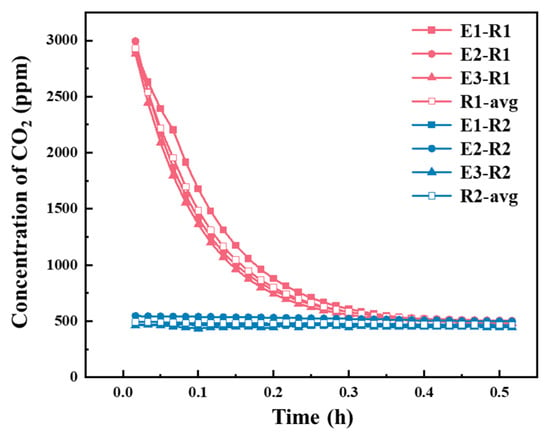

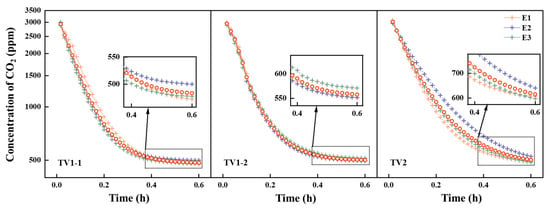

The average of the three trickle ventilators during three repeated experiments ranged from 0.95% to 1.04% (Figure 4a), indicating that the CO2 concentration in the room was uniform throughout the experiments and ruling out the influence of CO2 concentration non-uniformity on the measurement results.

Figure 4.

Statistical analysis of influencing factors of the tracer gas experiment. (a) Non-uniformity coefficient ; (b) CO2 concentration distribution in the source room (R1); (c) temperature difference distribution between the source room (R1) and the receiving room (R2) (E1-3 represent three repeated measurements, respectively).

We also quantified the effects of the ‘indoor–outdoor’ temperature difference (i.e., the temperature difference between R1 and R2) (Figure A2) and the ‘outdoor’ (i.e., R2) CO2 concentration on the measurement results. During the experiments, the concentration of CO2 in R1 was 497 ppm, 487 ppm, and 449 ppm when using TV1-1, TV1-2, and TV2, respectively (Figure 4b). The lowest CO2 concentration in R1 was observed with TV2, but overall concentrations remained above 420 ppm. When using TV1-1 and TV2, the temperature differences between the two rooms fluctuated more than with TV1-2 (Figure 4c), but the overall variation ranged only from −0.1 °C to 0.5 °C, indicating minor fluctuations. This suggests that the temperature difference (thermal pressure) was not a major factor affecting the experimental results. Correlation analyses between the CO2 concentration distribution in R1, the double-chamber temperature difference, and ventilation rates are presented in Table A3. Under the experimental conditions, the ventilation rates measured by the tracer gas decay method showed no significant correlation with the ‘outdoor’ CO2 concentration (r = 0.36, p = 0.34) or the ‘indoor–outdoor’ temperature difference (r = 0.31, p = 0.42).

3.2. Ventilation Performance by Tracer Gas Method

Table A4 presents the and of the three trickle ventilators under a pressure difference of 10 Pa. The ventilation performance of TV1-1 and TV1-2 is relatively stable, whereas the of TV2 shows noticeable fluctuations, likely due to its internal structure being significantly different from that of TV1 (Figure A3). On average, the ventilation rates of TV1-1, TV1-2, and TV2 are 11.8 m3·h−1, 12.4 m3·h−1, and 11.8 m3·h−1, respectively. Assuming a per-person bedroom area of 15 m2 [45] and a room volume of 39 m3 [9], according to the ‘Design code for heating, ventilation, and air conditioning of civil buildings’ [46], when the per-person living area ranges from 10 to 20 m2, the required is 0.6, corresponding to a ventilation rate of 23.4 m3·h−1. Therefore, installing only two trickle ventilators in the bedroom is sufficient to meet the requirement.

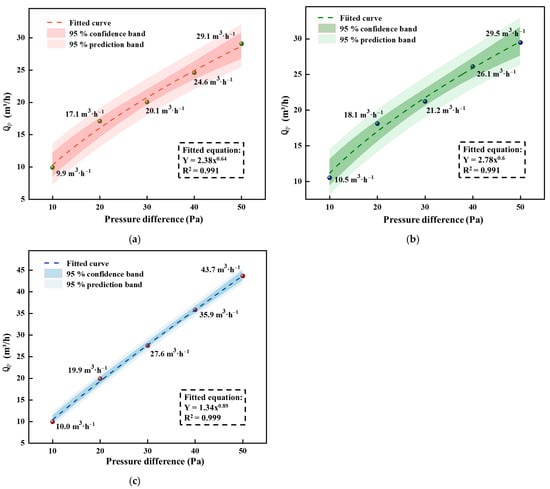

3.3. Flow Coefficient ()

Although the three trickle ventilators differ in structure and ventilation rate, all can achieve satisfactory ventilation, and their ventilation characteristics are closely related to their structural features. The ventilation rate of all three ventilators increases exponentially with the pressure difference (Table A5). Measured by the pressure difference method, at 10 Pa, the ventilation rates of TV1-1, TV1-2, and TV2 are 10.0 m3·h−1, 10.5 m3·h−1, and 10.0 m3·h−1, respectively, indicating similar performance at low pressure differences. As the pressure difference increases, the ventilation rates of all three rise further. At 50 Pa, the ventilation rates are 29.1 m3·h−1, 29.5 m3·h−1, and 43.7 m3·h−1, respectively, showing that TV2 is much more sensitive to changes in pressure difference.

The flow coefficients () of the three trickle ventilators were 2.38, 2.78, and 1.34, and the flow components () were 0.64, 0.6, and 0.89, respectively (Figure 5). TV1-1 (Figure 5a) and TV1-2 (Figure 5b) exhibited relatively high (2.38 and 2.78) but relatively low (0.64 and 0.6). This indicates that the deviation between the actual and theoretical airflow of TV1 is relatively large, and the low values suggest low sensitivity to pressure difference, resulting in a slower increase in ventilation rate at higher pressure differences. In contrast, TV2 (Figure 5c) had a lower (1.34), indicating that its airflow is closer to the ideal, and a higher (0.89) suggests a more rapid increase in ventilation rate under higher pressure differences.

Figure 5.

Ventilation performance of trickle ventilators under varying pressure differences. (a) TV1-1; (b) TV1-2; (c) TV2.

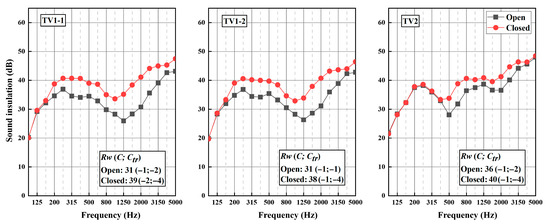

3.4. Sound Insulation Performance

Under the open condition, the weighted sound reduction index of TV2 (i.e., the weighted normalized sound pressure level difference ) is 36 dB, 5 dB higher than that of TV1 (Table A6). The of TV2 is 34 dB, which is 5 dB and 4 dB higher than those of TV1-1 and TV1-2, respectively. It can be seen that TV2 performs best in terms of both and . Therefore, under the open condition, TV2 exhibits the optimal sound insulation performance (Table A7). When closed, the of the trickle ventilator is 4–8 dB higher than in the open condition (Table A6).

In the low-frequency range (below 315 Hz), all three ventilators exhibit similar sound insulation spectra under both open and closed conditions, with relatively poor performance (Figure 6). This is because the sound wave in the low-frequency band is much larger than the opening size of the ventilator, causing the opening to have almost no attenuation effect in this frequency band. In addition, the sound insulation performance is more determined by the entire component rather than just the opening size. At low frequencies, the housing of the trickle ventilator is more prone to overall vibration.

Figure 6.

Sound insulation spectrum of the trickle ventilator under open and closed conditions.

In the mid-frequency and high-frequency ranges, closing the trickle ventilator increases its sound insulation by approximately 1–10 dB compared with the open condition. In the mid-frequency range (315–2000 Hz), the trickle ventilators show relatively strong sound insulation. TV1 exhibits a coincidence effect near 1250 Hz, resulting in a dip in sound insulation due to the matching of the sound wavelength and the structural bending wavelength. TV2 shows a coincidence effect at 500 Hz, indicating that its sound insulation performance in the mid-frequency range needs improvement. In the high-frequency range (above 2000 Hz), the sound spectra of TV1-1 and TV1-2 are similar, while TV2 shows a decrease in sound insulation at 2 kHz, suggesting minor structural deficiencies in its high-frequency design.

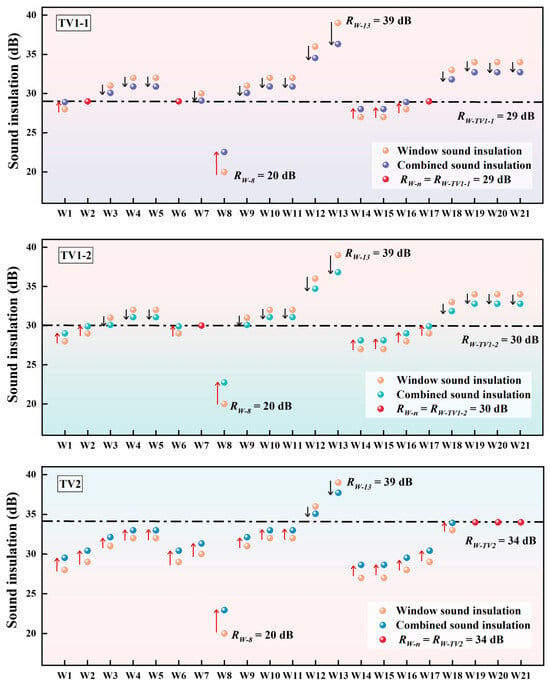

3.5. Analysis of Combined Sound Insulation

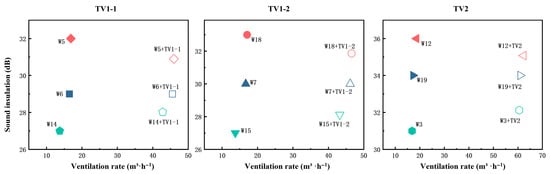

The variation patterns of combined sound insulation can be classified into three scenarios (Figure 7). When the sound insulation of the window configuration is lower than that of the trickle ventilator (red arrows), the combined sound insulation increases. For example, the sound insulation of configuration 8 (W8) is 20 dB; when combined with TV1 and TV2, the combined sound insulation increases by approximately 3 dB. When the sound insulation of the window configuration is higher than that of the trickle ventilator (black arrows), the combined sound insulation decreases. For instance, configuration 13 (W13) has a sound insulation of 39 dB; when combined with TV1 and TV2, the combined sound insulation decreases by 1–3 dB. When the sound insulation of the window is equal to or close to that of the trickle ventilator, the variation in combined sound insulation is minimal. In this case, the combined sound insulation depends on installation sealing or material characteristics, such as resonance effects.

Figure 7.

Combined sound insulation of trickle ventilators with different window configurations (in the figure, denotes of the n-th window configuration; , , and denote of the three trickle ventilators; the direction of the arrows denotes an increase or decrease in combined sound insulation, and the longer the arrow, the greater the change in sound insulation after combination).

Sound insulation and ventilation often exhibit a trade-off. When trickle ventilators are combined with different window configurations, the ventilation rate inevitably increases, while the sound insulation performance of the window shows three types of variation (Figure 8), consistent with the trends presented in Figure 7. When low-soundproof windows are paired with high-performance trickle ventilators, both sound insulation and ventilation may improve simultaneously, as observed for W14, W15, and W3. While TV1-1 enhances performance with low-soundproof windows, it compromises the sound insulation of high-soundproof windows. TV1-2 shows similar behavior, slightly inferior to TV1-1. TV2, owing to its superior intrinsic sound insulation, demonstrates strong combined sound insulation performance and is suitable for windows with sound insulation levels of 30–36 dB, achieving a balance between ventilation and sound insulation.

Figure 8.

Relationship between sound insulation and ventilation of combinations of window and trickle ventilator.

4. Discussion

In this study, a double-chamber model was employed to quantify the ventilation rate of trickle ventilators, and their resistance characteristics were analyzed using the flow coefficient (), providing an intuitive demonstration of the ventilation performance and sensitivity to pressure differences of the trickle ventilator. Simultaneously, the weighted sound reduction index () and sound insulation spectrum performance of the trickle ventilators were measured in the double-chamber model to classify their sound insulation levels and examine their spectral characteristics. The combined sound insulation of trickle ventilators with 21 different window configurations was also calculated. Finally, the relationship between sound insulation and ventilation was quantitatively analyzed, providing data support for the façade design strategy that balances acoustic comfort and ventilation requirements.

In this study, trickle ventilators were installed in a standardized heavy-duty test wall to evaluate their own sound insulation performance and ventilation performance. Several factors of the wall structure might affect the measured sound insulation effect: wall quality, the joints between the wall and the trickle ventilator, and the materials used to fix the trickle ventilator might influence the transmission of low-frequency sounds, change mid-frequency resonance, and possibly introduce additional vibration paths [47,48,49]. These structural factors mainly affect the mid-low frequency range, while the characteristics of the window ventilator itself still dominate the sound insulation performance throughout the entire frequency band [50], that is, the weighted sound insulation index. In contrast, the measured ventilation effect (flow coefficient , flow index , and air volume is mainly determined by the geometric structure and resistance of the ventilator [51], and the influence of wall quality and stiffness can be ignored, but gaps or poor sealing around the opening of the trickle ventilator may affect the measurement of air flow. Overall, the measurement results still reliably reflect the performance of the window ventilator itself, providing a solid foundation for the analysis of different window type combinations.

The temperature difference measured in the double-chamber model was 0.25 °C. Analysis of the correlation between this temperature difference and indicated that the effect of temperature difference on ventilation rate is negligible, consistent with previous studies showing that small indoor-outdoor temperature differences have little impact on natural ventilation [24]. Additionally, monitoring of the concentration of CO2 in R1 excluded any influence of CO2 variation on the measurement results.

The ventilation performance of the trickle ventilators was measured using the tracer gas decay method, yielding reliable and stable results [16]. In this study, under the double-chamber model, the between the ventilation rate measured by the tracer gas decay and pressure difference methods was below 20% (Table A8), significantly lower than the 36.9% reported in previous studies under varying seasonal and environmental conditions [24], demonstrating the stability of the experimental environment. Overall, the double-chamber model effectively minimizes interference caused by climate variations.

At a pressure difference of 10 Pa, the three trickle ventilators exhibited similar ventilation performance as measured by the tracer gas decay method. To further investigate their ventilation characteristics, this study analyzed differences in the flow coefficient () and flow exponent () between TV1 and TV2. These differences may be related to their internal structures [52], airflow paths [26], and sensitivity to pressure differences [53]. Previous studies indicated that the shape and internal design of ventilation elements significantly affect airflow velocity distribution and patterns [54]. Although TV1 and TV2 differ substantially in internal structures, their ventilation difference at 10 Pa is only 1.0–2.9 m3·h−1, confirming that at low pressure differences, internal guide variations have minimal effect on ventilation performance [55]. Notably, all three trickle ventilators can achieve a higher ventilation rate at larger pressure differences, but their sensitivity to pressure variations differs; TV2’s lower and higher indicate a more responsive behavior to external pressure changes compared to TV1. This implies that TV2 may facilitate more effective air exchange under variable wind or pressure conditions, which could contribute to improved indoor air quality stability. However, this trend requires validation under a real building façade environment.

Based on the values under the open condition, TV2 exhibits the best sound insulation performance (34 dB). This difference may be attributed to TV2 containing more fibrous materials. Previous studies have shown that lining ventilation ducts with sound-absorbing materials can significantly improve acoustic attenuation. For instance, installing 5.0 cm thick absorptive material in a 121.9 cm diameter intake duct increased sound insulation by 1–13 dB [56]. These findings indicate that appropriately increasing the amount of absorptive material and optimizing its placement can effectively enhance the sound insulation performance of trickle ventilators, particularly for mid-to-high frequency noise.

In this study, all three trickle ventilators exhibited pronounced fluctuations in their mid-frequency sound insulation curves. Rauscher [57] demonstrated that spectral-level sound insulation data can also explain the impact on subjective noise and practical applications. Based on our results, enhancing the sound insulation of trickle ventilators requires targeted measures considering their sound insulation spectrum performance. For example, TV1 shows poor sound insulation at mid-frequency (1250 Hz), whereas TV2 suffers greater insulation loss in the low-mid frequency range (around 500 Hz). Mitigating the coincidence effect can be achieved by adjusting materials and structures, such as using multilayer composites or varying material thickness. Increasing the thickness of rubber damping layers in medium-density fiberboard can reduce the depth of coincidence dips and improve the weighted sound reduction index [58]. Additionally, low-frequency insulation deficiencies can be addressed by adding damping materials; for instance, attaching damping mats to hollow ash panels can simultaneously improve low-frequency resonance and high-frequency coincidence [59].

The overall sound insulation loss between the source and receiver is determined by the combined sound insulation performance of all elements along the propagation path [60]. The total insulation performance is not the average of individual element performances but is constrained by the weakest link [61]. In this study, trickle ventilators enhanced the overall insulation performance in low-soundproof windows but reduced it in high-soundproof windows. Among the three ventilators, TV2 performed best, closely related to its high sound insulation (34 dB).

Furthermore, there is an inherent interaction between ventilation and energy efficiency. Ridley found that humidity-controlled ventilators can reduce excessive humidity without significantly increasing ventilation heat loss [62]. The continuous airflow provided by trickle ventilators helps maintain indoor air quality, but it sometimes also introduces heat loss, affecting building energy consumption. This trade-off is particularly crucial in cold regions with high heating demands. In contrast, in temperate or warm-humid climate zones, the energy efficiency cost is usually less significant [63]. Therefore, the application of trickle ventilators requires a comprehensive assessment in combination with local climate conditions and energy regulations. Future research should focus on achieving an overall evaluation of ventilator performance, integrating acoustic performance, ventilation characteristics, and energy consumption impact, to provide a more comprehensive technical basis for sustainable building design.

This study still has certain limitations. Firstly, the trickle ventilators were installed in a standardized heavy-duty test wall within the laboratory rather than in an actual window frame. Although this approach helps to achieve stable boundary conditions, differences between the wall and a window frame in terms of mass, stiffness, sealing details, and potential flanking transmission paths may affect the measurements of sound insulation. Secondly, this study only tested three products with two internal structure types, which does not cover the range of different sizes, materials, and construction forms available on the market, thus limiting the representativeness of the findings. Furthermore, the sound insulation of the window–trickle ventilator assembly was estimated using a theoretical model and has not yet been experimentally validated. Additionally, practical factors such as device aging, dust accumulation, degradation of sealing performance, and localized airflow organization were not considered. Future research should expand the sample range, conduct experimental validation of window–trickle ventilator assemblies, and assess the impact of long-term use and different installation methods on performance to enhance the reliability and applicability of the conclusions.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the ventilation and sound insulation performance of trickle ventilators using both the tracer gas decay method and the pressure difference method. The good consistency between the two methods ( < 20%) confirms the reliability of the double-chamber method for assessing trickle ventilator performance. The flow coefficient () and flow exponent () effectively describe how ventilation responds to pressure differences, and devices with higher show stronger pressure sensitivity. The acoustic tests indicate that the three devices provide moderate sound insulation ( = 29–34 dB), and that internal material resonance contributes to a noticeable coincidence dip at mid-high frequencies. When combined with different window systems, a clear interaction between ventilation and sound insulation emerges. In low-sound-insulation windows, trickle ventilators can even improve both airflow and acoustic performance simultaneously, whereas in high-performance windows, they tend to reduce overall sound insulation. This demonstrates the practical trade-off between ventilation and noise control: improving one aspect often restricts the other. From a theoretical perspective, differences in wind-pressure environments could influence the performance of pressure-sensitive versus stable models; however, practical suggestions need to be verified in a real building façade environment. However, because only three products were tested, the numerical results should not be generalized to all trickle ventilators. In contrast, the main contribution of this study lies in establishing a systematic methodological framework for evaluating trickle ventilators and identifying representative patterns in their ventilation and sound insulation performance, thereby providing a solid foundation for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.Z.; methodology, S.W., N.Z. and X.Y.; formal analysis, S.W. and H.L.; investigation, S.W., H.L., Z.C. and Z.Z.; resources, N.Z.; data curation, S.W. and X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.; writing—review and editing, S.W., H.L. and N.Z.; visualization, S.W. and N.Z.; supervision, N.Z. and X.Y.; project administration, N.Z.; funding acquisition, N.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52478074.

Data Availability Statement

The original details of the data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author affirms that all individuals who contributed significantly to this work are listed as authors. No additional contributors need to be acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IEQ | Indoor Environment Quality |

| TV | Trickle Ventilator |

| SBS | Sick Building Syndrome |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| IAQ | Indoor Air Quality |

| PVC | Polyvinyl Chloride |

| UPVC | Unplasticized Polyvinyl Chloride |

| ACH | Air Change Rate |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

Appendix A

Trickle ventilators are typically installed together with windows. Below are the typical installation configurations of trickle ventilators (Figure A1).

Figure A1.

Typical installation configurations of trickle ventilators.

Table A1 provides a supplementary table showing four common structural configurations of ‘straight-channel’ type and ‘labyrinth’ type trickle ventilators. These examples illustrate the scope of commercially available designs corresponding to the two structural categories discussed in the main text.

Table A1.

Trickle ventilators with different internal structures.

Table A1.

Trickle ventilators with different internal structures.

| Straight-Channel Type: A Relatively Short and Linear Airflow Pathway (‘Straight-Channel’ Type Examples) | |||

|  |  |  |

| Labyrinth type: a longer, folded, and more tortuous airflow pathway (‘labyrinth’ type examples) | |||

|  |  |  |

The article selects windows with different glass configurations, including: single glazing, double glazing, triple glazing, and laminated glazing. Different thicknesses are chosen for each type of glass. The sound insulation range of the 21 selected glass configurations is between 28 and 39 dB. The window types are listed in Table A2.

Table A2.

Different types of window configurations (taking a 1.5 × 1.5 m window as an example).

Table A2.

Different types of window configurations (taking a 1.5 × 1.5 m window as an example).

| Type | Window Configuration 1 | 2 (dB) | Thickness 3 (mm) | Window Thickness (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | G5 | 28 | 5 | 5 |

| W2 | G6 | 29 | 6 | 6 |

| W3 | G8 | 31 | 8 | 8 |

| W4 | G10 | 32 | 10 | 10 |

| W5 | G12 | 32 | 12 | 12 |

| W6 | G5+A6+G5 | 29 | 16 | 10 |

| W7 | G5+A12+G5 | 30 | 22 | 10 |

| W8 | G5+A18+G5 | 20 | 28 | 10 |

| W9 | G5+A24+G5 | 31 | 34 | 10 |

| W10 | G5+A36+G5 | 32 | 46 | 10 |

| W11 | G5+A72+G5 | 32 | 82 | 10 |

| W12 | G5+A108+G5 | 36 | 118 | 10 |

| W13 | G5+A144+G5 | 39 | 154 | 10 |

| W14 | G5+A6+G5+A6+G5 | 27 | 27 | 15 |

| W15 | G5+A12+G5+A12+G5 | 27 | 39 | 15 |

| W16 | G5+A18+G5+A18+G5 | 28 | 51 | 15 |

| W17 | G5+A24+G5+A24+G5 | 29 | 63 | 15 |

| W18 | G5+P0.38+G5 | 33 | 11 | 10 |

| W19 | G5+P0.76+G5 | 34 | 11 | 10 |

| W20 | G5+P1.14+G5 | 34 | 12 | 10 |

| W21 | G5+P1.52+G5 | 34 | 12 | 10 |

1 The thickness, quantity, and sequence of glass, cavities, and PVB interlayers. Here, G denotes the glass thickness (mm); A denotes the air cavity thickness (mm); and P denotes the thickness of polyvinyl butyral (PVB) interlayer (mm). 2 The sum of the weighted sound reduction index of the window and the traffic noise spectrum adaptation term. 3 The thickness of the glass structure.

Taking TV1-1 as an example, we present the CO2 decay in R2 and the CO2 concentration distribution in R1 during the experiment (Figure A2). Across the three repeated experiments, the CO2 concentration in R1 remained approximately 500 ppm, showing no significant upward trend. This indicates that releasing over 3000 ppm of CO2 in R2 did not affect the CO2 concentration in R1. This observation is consistent with real-world environment, where outdoor CO2 concentrations do not necessarily change in parallel with the increase or decay of indoor CO2. These results further demonstrate that operating the supply air equipment in the source room can effectively simulate outdoor environmental conditions.

Figure A2.

CO2 concentration decay curve during the TV1-1 experiment and the CO2 concentration distribution in R1 (E1-3-R1 and E1-3-R2 denote three repeated measurements of TV1-1 in R1 and R2, respectively; R1-avg and R2-avg denote the average CO2 concentrations in R1 and R2, respectively).

We also analyzed the correlations between CO2 concentration distribution in R1, the temperature difference between the two rooms, and the ventilation rate during the experiment (Table A3). Under the experimental conditions, the ventilation rate measured by the tracer gas decay method showed no significant correlation with the outdoor CO2 concentration (r = 0.36, p = 0.34) or the indoor–outdoor temperature difference (r = 0.31, p = 0.42).

Table A3.

Table of Pearson correlation analysis.

Table A3.

Table of Pearson correlation analysis.

| Influencing Factors | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation Analysis | Sig. (Two-Tailed) | |

| Outdoor CO2 concentration | 0.364 | 0.336 |

| Indoor–outdoor temperature difference | 0.309 | 0.419 |

p < 0.05. p < 0.01. p < 0.001.

The ventilation performance of three types of trickle ventilators were measured at an environmental pressure difference of 10 Pa. Each type of trickle ventilator was measured three times. The measurement results are shown in Table A4.

Table A4.

and of trickle ventilator ( = 10 Pa, = 98.1 m3).

Table A4.

and of trickle ventilator ( = 10 Pa, = 98.1 m3).

| Type | (h−1) | (m3·h−1) | (m3·h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TV1-1 | 0.12 | 11.8 | 11.8 |

| 0.11 | 10.8 | ||

| 0.13 | 12.8 | ||

| TV1-2 | 0.13 | 12.8 | 12.4 |

| 0.12 | 11.8 | ||

| 0.13 | 12.8 | ||

| TV2 | 0.14 | 13.7 | 11.8 |

| 0.1 | 9.8 | ||

| 0.12 | 11.8 |

The CO2 decay rates of TV1-1 and TV1-2 were consistent (Figure A3). The CO2 decay rate of TV2 was relatively slower, and the three repeated curves were more widely distributed, which is consistent with the variation in ACH. Under steady conditions, the relatively consistent results among the three ventilators further validate the repeatability of the double-chamber model experiments.

Figure A3.

CO2 tracer gas decay curve (average of three experiments) (The curve in the figure represents the attenuation status of CO2 concentration. The small boxes in the figure represent the concentration distribution of three types of trickle ventilators in the later stage of CO2 attenuation).

This section presents the results of ventilation performance measured by the pressure difference method. The wind speed under five groups of pressure differences was measured for each type of trickle ventilator, and the measurement results are shown in Table A5.

Table A5.

Ventilation rate under different pressure differences ().

Table A5.

Ventilation rate under different pressure differences ().

| Type | (Pa) | (m·s−1) | (cm2) | (m3·h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TV1-1 | 10 | 1.2 | 23.4 | 9.9 |

| 20 | 2.0 | 17.1 | ||

| 30 | 2.4 | 20.1 | ||

| 40 | 2.9 | 24.6 | ||

| 50 | 3.5 | 29.1 | ||

| TV1-2 | 10 | 1.3 | 23.4 | 10.5 |

| 20 | 2.2 | 18.1 | ||

| 30 | 2.5 | 21.2 | ||

| 40 | 3.1 | 26.1 | ||

| 50 | 3.5 | 29.5 | ||

| TV2 | 10 | 0.7 | 42.6 | 10.0 |

| 20 | 1.3 | 19.9 | ||

| 30 | 1.8 | 27.6 | ||

| 40 | 2.3 | 35.9 | ||

| 50 | 2.9 | 43.7 |

This study tested the sound insulation performance of trickle ventilators at different frequencies in echo chamber. Measurements were conducted in both the open and closed conditions. The measurement results are shown in Table A6.

Table A6.

Sound insulation of the trickle ventilator under open and closed conditions.

Table A6.

Sound insulation of the trickle ventilator under open and closed conditions.

| (dB) | TV1-1 | TV1-2 | TV2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (Hz) | Open | Closed | Open | Closed | Open | Closed | |

| 100 | 20.2 | 20.1 | 19.8 | 19.7 | 21.8 | 21.5 | |

| 125 | 29.2 | 29.6 | 28.3 | 28.6 | 29.3 | 28.1 | |

| 160 | 32.2 | 33.0 | 31.9 | 33.3 | 32.3 | 32.3 | |

| 200 | 34.6 | 38.3 | 34.8 | 39.1 | 37.5 | 37.8 | |

| 250 | 36.9 | 40.7 | 36.9 | 40.6 | 38.2 | 38.6 | |

| 315 | 34.9 | 40.7 | 34.4 | 40.2 | 35.9 | 36.3 | |

| 400 | 34.1 | 40.7 | 34.2 | 40.0 | 32.9 | 33.3 | |

| 500 | 34.5 | 39.0 | 35.4 | 39.7 | 28.0 | 33.8 | |

| 630 | 32.8 | 38.6 | 33.2 | 38.4 | 31.8 | 38.8 | |

| 800 | 29.8 | 35.0 | 30.5 | 34.6 | 36.4 | 40.6 | |

| 1000 | 28.3 | 33.6 | 28.2 | 32.9 | 37.5 | 40.2 | |

| 1250 | 26.0 | 35.2 | 26.3 | 33.8 | 38.6 | 40.9 | |

| 1600 | 28.3 | 38.4 | 28.6 | 37.9 | 36.6 | 39.6 | |

| 2000 | 30.7 | 41.1 | 31.1 | 40.7 | 36.6 | 41.3 | |

| 2500 | 35.6 | 44.1 | 36.0 | 43.2 | 40.1 | 44.7 | |

| 3150 | 39.1 | 45.0 | 38.9 | 43.7 | 44.2 | 46.4 | |

| 4000 | 42.7 | 45.3 | 42.3 | 44.0 | 45.6 | 46.3 | |

| 5000 | 43.1 | 47.5 | 42.8 | 46.4 | 48.0 | 48.5 | |

| 31 (−1; −2) | 39 (−2; −4) | 31 (−1; −1) | 38 (−1; −4) | 36 (−1; −2) | 40 (−1; −4) | ||

The sound insulation levels of trickle ventilators are classified based on in the open state (Table A7). Higher values denote higher sound insulation levels, and TV2 exhibits the highest level among the tested ventilators.

Table A7.

Sound insulation level classification of trickle ventilators [31].

Table A7.

Sound insulation level classification of trickle ventilators [31].

| TV | Sound Insulation Level 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-1 | Open | 31 | 29 | 3 |

| 1-2 | Open | 31 | 30 | 4 |

| 2 | Open | 36 | 34 | 5 |

1: The higher the level, the better the sound insulation performance.

In this experiment, the pressure difference method was used not only to measure the of the trickle ventilators, but also to compare the correlation between the results obtained from the pressure difference method and the double-chamber model. The average MAPE between the measurements from the pressure difference method and those from the tracer gas decay method was below 20% (Table A8). This further confirms that under an environmental pressure difference of 10 Pa, the measurements obtained by the tracer gas decay method in the double-chamber model are reasonable.

Table A8.

MAPE between the pressure difference method and the two-room tracer gas method.

Table A8.

MAPE between the pressure difference method and the two-room tracer gas method.

| Type | Ventilation Rate (m3·h−1) | MAPE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TV1-1 | 9.9 | 11.8 | 18.4% |

| 10.8 | |||

| 12.8 | |||

| TV1-2 | 10.5 | 12.8 | 18.0% |

| 11.8 | |||

| 12.8 | |||

| TV2 | 10.0 | 13.7 | 19.2% |

| 9.8 | |||

| 11.8 | |||

References

- Dai, H.K.; An, Y.; Huang, W.; Chen, C. Design optimization of floor plan for public housing buildings in Hong Kong with consideration of natural ventilation, noise, and daylighting. Build. Environ. 2024, 263, 111865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; He, Y.; Hao, X.; Li, N.; Su, Y.; Qu, H. Optimal temperature ranges considering gender differences in thermal comfort, work performance, and sick building syndrome: A winter field study in university classrooms. Energy Build. 2022, 254, 111554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón, J.; Giraldo, C.H.; Monyake, K.C.; Alagha, L.; Colorado, H.A. Experimental investigation on composites incorporating rice husk nanoparticles for environmental noise management. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, H.; Mao, H. An energy-based framework for predicting vehicle noise source intensity: From energy consumption to noise. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 369, 122334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T.; Sørensen, M.; Daiber, A. Transportation noise pollution and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.M.; Lercher, P. Road traffic noise exposure and depression/anxiety: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Burden of Disease from Environmental Noise; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011; ISBN 978-92-890-0229-5. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/326424 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Zaporozhets, O.; Fiks, B.; Jagniatinskis, A.; Tokarev, V.; Karpenko, S.; Mickaitis, M. Indoor noise A-level assessment related to the environmental noise spectrum on the building facade. Appl. Acoust. 2022, 185, 108380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50118-2010; Code for Design of Sound Insulation of Civil Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010. (In Chinese)

- Berardi, U.; Ivona, C.; Stasi, R. Sound insulation improvements in lift-and-slide window systems. Build. Environ. 2025, 282, 113258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baadache, K.; Guedouh, M.S.; Haddad, D. A multi-objective optimization of window surface and glass thickness determination for daylight factor, thermal resistance and acoustic insulation of a test room performances under an overcast sky. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 101, 111717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Lu, W.; Peng, Z. Enhancing natural ventilation in modular buildings: A reversible Wind Module graph generative design approach. Build. Environ. 2025, 285, 113593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, V.; Macinate, M.; Hassan, H.; Doherty, E.; Wemken, N.; Norton, D.; Foster, D.; Cowie, H.; Coggins, A.M. Deep energy renovations in Irish domestic dwellings; unlocking health benefits. Indoor Built Environ. 2025, 34, 1420326X251371323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Housing and Health Guidelines; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- EN 16798-1:2019; Energy Performance of Buildings—Ventilation for Buildings—Part 1: Indoor Environmental Input Parameters for Design and Assessment of Energy Performance of Buildings Addressing Indoor Air Quality, Thermal Environment, Lighting and Acoustics. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- GB/T 18883-2022; Standards for Indoor Air Quality. State Administration for Market Regulation and Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2022. (In Chinese)

- Biler, A.; Ünlü Tavil, A.; Su, Y.; Khan, N. A review of performance specifications and studies of trickle vents. Buildings 2018, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, I.; Fox, J.; Oreszczyn, T. Controllable background ventilation in dwellings—The equivalent opening area needed to achieve appropriate indoor air quality. Int. J. Vent. 2016, 3, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JG/T 233-2017; Ventilator for Windows and Doors of Building. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2017. (In Chinese)

- Coydon, F.; Herkel, S.; Kuber, T.; Pfafferott, J.; Himmelsbach, S. Energy performance of façade-integrated decentralised ventilation systems. Energy Build. 2015, 107, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolokotroni, M.; White, M.K.; Perera, M. Trickle ventilators: Field measurements in refurbished offices. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 1997, 18, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karava, P.; Stathopoulos, T.; Athienitis, A.K. Investigation of the performance of trickle ventilators. Build. Environ. 2003, 38, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurzyński, J. Acoustic performance of slot ventilators and their effect on the sound insulation of a window. In Proceedings of the INTER-NOISE and NOISE-CON Congress and Conference, Leuven, Belgium, 25–28 August 2003; pp. 890–899. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.; Song, D. How to quantify natural ventilation rate of single-sided ventilation with trickle ventilator? Build. Environ. 2020, 181, 107119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karava, P.; Athienitis, A.K.; Stathopoulos, T. Simulation of the performance of trickle ventilators. In Proceedings of the ESIM Conference, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–13 September 2002; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Boulic, M.; Bombardier, P.; Zaidi, Z.; Russell, A. Using trickle ventilators coupled to fan extractor to achieve a suitable airflow rate in an Australian apartment: A nodal network approach connected to a CFD approach. Energy Build. 2024, 304, 113828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yao, L.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, D.; Chen, T. Optimizing the performance of window frames: A comprehensive review of materials in China. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Y.D. Test and analysis of airborne sound insulating properties for building’s external windows and doors. Noise Vib. Control 2013, 33, 115–119. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 18204.1-2013; Examination Methods for Public Places—Part 1: Physical Parameters. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2013. (In Chinese)

- T/CAEPI 38-2021; Technical Requirements for Ventilation and Sound Insulation Windows. China Association of Environmental Protection Industry: Beijing, China, 2021. (In Chinese)

- The Energy Conservatory. US. Available online: https://www.energyconservatory.com/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- KIMO Instruments. France. Available online: https://sauermanngroup.com/fr-FR (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- ISO 10140-2:2021; Acoustics—Laboratory Measurement of Sound Insulation of Building Elements—Part 2: Measurement of Airborne Sound Insulation. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- ISO 12569:2017; Thermal Performance of Buildings and Materials—Determination of Specific Airflow Rate in Buildings—Tracer Gas Dilution Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Cui, S.; Cohen, M.; Stabat, P.; Marchio, D. CO2 tracer gas concentration decay method for measuring air change rate. Build. Environ. 2015, 84, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T&D Corporation. Japan. Available online: https://www.tandd.co.jp/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Shi, Y.P.; Zou, Z.J.; Huang, C. Test effect of different tracer gases on room ventilation. In Proceedings of the IEHB Conference, Hunan, China, 16–18 November 2012; pp. 267–275. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- ASHRAE. ASHRAE Handbook-Fundamentals-Airflow Around Buildings; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xuan, Z.Q. Study on Measurement and Calculation of Natural Ventilation in Typical Residential Buildings and Its Related Influencing Factors. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Jiangsu, China, 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- ISO 717-1:2020; Acoustics—Rating of sound insulation in buildings and of building elements—Part 1: Airborne sound Insulation. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Cai, C.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, L. Experimental Study on the Effect of Urban Road Traffic Noise on Heart Rate Variability of Noise-Sensitive People. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 749224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, D.; He, D.; Liu, Y.; Taib, N.; Heng Yii Sern, C. Seasonal thermal performance of double and triple glazed windows with effects of window opening area. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, S.; Liao, W. Time- and environment-dependent water content distribution in polyvinyl butyral (PVB) laminated glass: Interlayer and interface contributions. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 112, 113659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 55016-2021; General Code for Building Environment. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021. (In Chinese)

- Kang, M.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Guo, C.; Fan, X.; Sekhar, C.; Lian, Z.; Wargocki, P.; Li, L. Associations between bedroom environment and sleep quality when sleeping less or more than 6 h: A cross-sectional study during summer. Build. Environ. 2024, 257, 111531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50736-2012; Design Code for Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning of Civil Buildings. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2012. (In Chinese)

- Løvholt, F.; Norèn-Cosgriff, K.; Madshus, C.; Ellingsen, S.E. Simulating low frequency sound transmission through walls and windows by a two-way coupled fluid structure interaction model. J. Sound Vib. 2017, 396, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Du, B.; Huang, Y. Experimental study on airborne sound insulation performance of lightweight double leaf panels. Appl. Acoust. 2022, 197, 108907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbán, D.; Roozen, N.B.; Zaťko, P.; Rychtarikova, M.; Tomašovič, P.; Glorieux, C. Assessment of sound insulation of naturally ventilated double skin facades. Build. Environ. 2016, 110, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orduña-Bustamante, F.; Velasco-Segura, R.; Quintero, G.; Pérez-Ruiz, S.J.; Pérez-López, A.; Dorantes-Escamilla, R.; Ponce-Patrón, D.R. Simplified vented acoustic window with broadband sound transmission loss. Appl. Acoust. 2024, 217, 109865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roostaee, A.; Khiadani, M.; Mohammed, H.A.; Shafieian, A. Harnessing the power of computational fluid dynamics for flow coefficient and rain resistance improvement of Type 1 Natural Ventilators. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 74, 106844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Shen, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X. Simulation analysis and experimental study of pipeline gas resistance modelling and series characteristics. Fluids 2025, 10, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzadi, M.; Mirzaei, P.A.; Naghashzadegan, M. Development of an adaptive discharge coefficient to improve the accuracy of cross-ventilation airflow calculation in building energy simulation tools. Build. Environ. 2018, 127, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, B.; Cui, H.; Huang, M. Improvement of airflow uniformity and noise reduction with optimized V-shape configuration of perforated plate in the air distributor. Indoor Built Environ. 2024, 33, 641–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemitis, J.; Bogdanovics, R.; Prozuments, A.; Borodinecs, A. Study of pressure-difference influence on airflow, heat-recovery efficiency and acoustic performance of a local decentralized ventilation device. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenchappa, B.; Shivakumar, K. Evaluation of a microporous acoustic liner using advanced noise-control fan engine. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauscher, T.; Neubauer, R.O.; Zaglauer, M.; Leistner, P. Single-number values versus subjective judgment of airborne sound insulation in dwellings. Build. Acoust. 2023, 30, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Peng, L.; Fan, Z.; Wang, D. Sound insulation and mechanical properties of wood damping composites. Wood Res. 2019, 64, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.Y.; Yu, J.J.; Wu, W. Study on sound insulation performance of several lightweight partition walls. Sichuan Arch. 2023, 43, 257–262. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Arjunan, A.; Baroutaji, A.; Robinson, J.; Vance, A.; Arafat, A. Acoustic metamaterials for sound absorption and insulation in buildings. Build. Environ. 2024, 251, 111250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, M.; Fediuk, R.; Murali, G.; Vatin, N.; Al-Fakih, A. Sound-absorbing acoustic concretes: A review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, I.; Davies, M.; Booth, W.; Judd, C.; Oreszczyn, T.; Mumovic, D. Automatic Ventilation Control of Trickle Ventilators. Int. J. Vent. 2016, 5, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoobi, A.W.; Ekimci, B.G.; Inceoğlu, M. A Comparative Study of Sustainable Cooling Approaches: Evaluating the Performance of Natural Ventilation Strategies in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions. Buildings 2024, 14, 3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).