Abstract

Coupled high temperature and dynamic loading often leads to the complicated degradation of performance in industrial kilns, enclosures, or other concrete structures, which constitutes a serious hazard to the safety of concrete structure. To bridge this research gap, this study investigates not only the mechanical response but also the damage mechanisms of normal concrete (NC), basalt fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRC), and steel fiber-reinforced concrete (SFRC) under the coupled effects of high temperature and dynamic loading. Test specimens were conditioned for ambient conditions, 200 °C, 400 °C, and 600 °C, and underwent quasi-static and dynamic splitting tensile tests using the Split Hopkinson Pressure Bar (SHPB) with strain rates varying between 24 and 91 s−1. Significantly, the high-temperature-induced degradation of all types of concrete is remarkably suppressed by fibers, especially steel fibers. The best thermal degradability resistance was displayed by the SFRC with the highest remaining residual dynamic strength, peak strain, and energy dissipation, especially in the most severe (600 °C, 0.15 MPa) circumstances among these three types of materials. All materials revealed a clear strain rate strengthening effect. An empirical model, integrating the coupling effect of strain rate, temperature, and fiber type in DIF, was also developed, yielding better prediction capability than those already available. This reveals that the comprehensive performance of SFRC can meet structure requests, so it is suitable for applications involving steel fiber in environments characterized by high temperature and high strain rates.

1. Introduction

Regarding a fundamental material in infrastructure projects, the in-service performance of concrete directly relates to the safety and durability of engineering structures. Concrete structures in applications such as industrial kilns, nuclear explosion-proof structures, and military protection structures and tunnels are often subjected to the composite action of high temperature (e.g., fire, high temperature environments) and dynamic loads (e.g., blast wave). This makes the study of the durability and damage response of concrete under temperature–impact actions indispensable. Therefore, the actual damage process and ultimate strength state of high-temperature concrete under dynamic loading can be investigated, and a high-temperature dynamic mechanical performance test device for concrete specimens should be established. In such extreme loading conditions, the mechanical behavior of concrete is very complicated and largely impaired; this might result in premature brittle failure, which represents an alarming threat to structural safety [1,2].

Thermal damage to concrete is a sequential process evolving from microstructural evolution to macroscopic performance deterioration. Studies indicate that when temperatures exceed 200 °C, the evaporation of free water generates capillary pore pressure. At temperatures between 400 °C and 600 °C, the thermal dissociation of calcium hydroxide as well as extensive dehydration of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel result in a loosened cement paste structure and severe weakening of the bonding performance at the aggregate–mortar interfacial transition zone (ITZ). Macroscopically, this is reflected as a significant reduction in strength and stiffness, along with rapid crack propagation [3,4]. Research by Cascardi et al. [5] indicates that strongly alkaline environments progressively weaken the interfacial bond between fibers and the cement matrix, leading to a decline in confinement effectiveness over time. This reflects the sensitivity of fiber–matrix synergy to external conditions such as chemical corrosion and high temperatures. Conversely, concrete is a rate-sensitive substance, as evidenced by its notable strain rate strengthening effect under dynamic loading, where its dynamic strength increases significantly with the loading rate. [6,7,8]. However, microstructural damage induced by high-temperature pretreatment is bound to alter the material’s dynamic mechanical response and energy absorption mechanisms. Until now, most research has centered on the dynamic behavior of concrete at normal temperatures or its static properties after high-temperature exposure. A critical gap exists in the systematic investigation of the progression of material properties through the combined condition of “high-temperature pretreatment followed by dynamic impact,” which hampers meeting the demands of engineering design and safety assessment under complex service conditions.

Fiber reinforcement is a viable strategy used to effectively increase the toughness, impact resistance, and crack resistance of concrete. Various fibers, especially steel fibers and basalt fibers, have attracted great attention because of their respective superiorities. Steel fibers, by virtue of their high tensile strength and favorable ductility, effectively suppress crack propagation within concrete and augment its energy dissipation capacity under ambient-temperature dynamic loading conditions [9,10]. In confined concrete columns, steel fibers have also been proven to effectively enhance the axial load-carrying capacity and ductility of the members [11]. Basalt fibers exhibit good corrosion resistance and dispersibility, and basalt fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRC) also exhibits enhanced strength and toughness under dynamic loading [12,13]. Research by Lai et al. [14] demonstrates that rational fiber–matrix combinations can significantly enhance structural performance under extreme loading conditions. Furthermore, the volume fraction, length, and hybridization methods have a significant influence on reinforcing effectiveness [15,16,17,18].

Nevertheless, the reinforcing performance of different fibers under the combined influence of high temperature and dynamic loading differs significantly. Wu et al. [19] summarized that basalt fibers were more susceptible to vitrification transformation at a temperature between 400 °C and 500 °C, and the performance of the interface properties between the fiber and mortar became worse. Although the melting point of steel fibers is higher than that of basalt, their post-high-temperature interfacial anchoring capacity and stress transfer efficiency still require systematic evaluation. Chen et al. [20] studied ultra-high-performance concrete under high-temperature exposure, finding that the performance evolution of different types of fibers under high temperature is a key factor influencing the material’s dynamic response. Tong et al. [21] investigated the dynamic mechanical properties of steel–polypropylene hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete at temperatures ranging from 20 to 800 °C and under varying strain rates. They concluded that the fiber reinforcement effect diminishes with increasing temperature at elevated conditions. There is currently a scarcity of experimental data and quantitative comparisons regarding the performance evolution and reinforcement mechanisms of concrete with these two fiber types under dynamic splitting tensile loads after exposure to different temperatures.

Furthermore, the Dynamic Increase Factor (DIF), a significant parameter characterizing the strain rate effect of materials, is crucial for the accurate design of structures under dynamic loads. Established models, such as those in CEB-FIP recommendations and by Malvar and Ross, are primarily based on experimental data from ordinary concrete at normal temperatures [22]. These models generally do not account for the coupled effects of thermal degradation and fiber reinforcement, leading to significant deviations when predicting the dynamic performance of fiber-reinforced concrete (FRC) after high-temperature exposure. In recent years, some scholars have conducted valuable explorations into the dynamic properties and DIF of FRC. For instance, Ganorkar et al. [23] analyzed the strain rate dependence of DIF in BFRC; Peng et al. [24] and Wang et al. [25] studied the suppressive effect of steel fiber content on DIF of steel fiber-reinforced concrete (SFRC) and its bilinear evolution law, respectively; and Chen et al. [26] compared the dynamic performance of concrete reinforced with carbon fibers versus carbon nanofibers. Factors such as fiber volume and fiber shape could affect SFRC’s DIF value [27]. However, most of these studies were confined to normal temperature conditions, and a DIF prediction model that comprehensively considers the interactive effects of temperature, strain rate, and fiber type has not yet been established.

Addressing the aforementioned research gaps, this paper investigates NC, BFRC (at a volume fraction of 0.1%), and SFRC (at a volume fraction of 1%). A systematic experimental program was conducted, including quasi-static splitting tensile tests, dynamic splitting tensile tests using the Split Hopkinson Pressure Bar (SHPB), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations, after exposure to high temperatures of ambient conditions, 200 °C, 400 °C, and 600 °C. This study seeks to (1) reveal the macroscopic failure patterns and microscopic damage mechanisms of the three types of concrete under coupled high temperature and dynamic loading; (2) quantify the synergistic effects of strain rate (24–91 s−1) and temperature on dynamic split tensile strength, peak strain, and dissipated energy; (3) elucidate the regulatory mechanisms of fiber type on the dynamic performance and high-temperature stability of concrete; and (4) establish an empirical DIF model that incorporates the influence of strain rate, temperature, and fiber type. The findings are intended to provide experimental evidence and theoretical support for the material selection and performance design of concrete structures serving in severe conditions, such as post-fire blast resistance and impact resistance in high-temperature industrial environments.

2. Experimental Design and Preparation

2.1. Mix Design and Constituent Materials for the Specimens

Three distinct concrete specimen categories were fabricated: SFRC, BFRC, and NC. Constituent materials comprised cement, coarse aggregates, fine aggregates, water, superplasticizers, and reinforcing fibers.

P·O 42.5 ordinary Portland cement supplied by Jidong Heidelberg Cement, Ltd., Xianyang, China, which denotes the “Ordinary Type” classification in Chinese cement standards, was used. This cement conforms to the clauses of Chinese standard GB/T 175-2007 [28]. Then, 5–10 mm crushed stone served as the coarse aggregate, while unprocessed river sand functioned as the fine aggregate. A polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer was incorporated to optimize the workability of fiber-reinforced mixtures and guarantee homogeneous fiber distribution throughout the concrete matrix.

Hooked-end steel fibers, with their improved anchoring strength, were supplied by Hengshui Shengying Metal Products Co., Ltd. (Hengshui, China) and employed in this study. Quality verification of these fibers was conducted following GB/T 39147-2020 [29], confirming that their tensile strength exceeded 1100 MPa. For comparative analysis, basalt fibers from Changsha Ningxiang Building Materials Co., Ltd. (Changsha, China) underwent testing as per GB/T 23265-2023 [30], with all specimens demonstrating tensile strength surpassing 1200 MPa. Detailed characteristics of both fiber types are comparatively presented in Table 1. All mixtures utilized potable water sourced from the laboratory’s supply system.

Table 1.

Physical attributes of steel fibers and basalt fiber.

The concrete formulations were developed in accordance with JGJ 55-2011 [31]. Drawing upon the technical guidelines CECS 38-2004 [32], along with industry standard JG/T 472-2015 [33] and supplementary research findings [34,35,36], the optimal fiber contents were established at 1% for steel fibers and 0.1% for basalt fibers. An NC reference group was concurrently prepared to enable the comparative analysis of the fiber-enhanced concrete’s dynamic performance under combined thermal and impact loading conditions. Table 2 summarizes the comprehensive mixture parameters.

Table 2.

Concrete mix proportions (kg/m3).

2.2. Specimen Fabrication and Curing

The NC, SFRC, and BFRC formulations were prepared individually following specific mixing protocols. To avoid fiber entanglement or uneven distribution, the operational procedures strictly adhered to the standardized mixing sequences outlined in JGJ/T 221-2010 [37]. During initial processing, reinforcement materials (steel fibers for SFRC and basalt fibers for BFRC) were introduced alongside coarse and fine aggregates into the mixing chamber for a preliminary dry blending phase lasting one minute. This critical step ensured thorough dispersion of fibrous materials within the aggregate matrix. Following this preparatory stage, binding agents, including cementitious materials, water, and rheology-modifying admixtures, were progressively incorporated. The complete mixture then underwent an extended mixing cycle of two minutes to achieve optimal component integration and guarantee uniform performance characteristics throughout the composite material.

The experimental samples consisted of cubic specimens with 100 mm side and cylindrical units with a 72 mm diameter × 40 mm height, designed, respectively, for static cube splitting tests and dynamic impact evaluations using an SHPB apparatus. The cylindrical specimens were prepared by casting newly mixed concrete into PVC molds with 75 mm external and 72 mm internal diameters. Following compaction using vibration tables, the samples underwent 24 h initial setting before demolding and identification marking. These specimens subsequently completed 28-day hydration maintenance in controlled humidity chambers. Post-curing processing involved precision cutting and surface grinding operations, ensuring the surface parallelism was within 0.05 mm. The complete manufacturing sequence for test specimens is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Specimen fabrication press.

2.3. Experimental Program

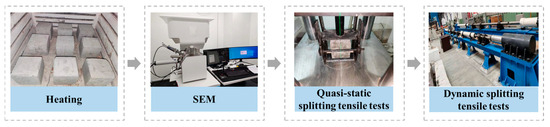

This study’s primary aim was to comprehensively examine the thermal behavior characteristics and phase transformation processes in FRC subjected to high-temperature exposure. The study framework incorporated four principal phases: thermal exposure protocols, scanning electron microscopy analysis, quasi-static tensile evaluations, and high-rate tensile assessments (detailed in Figure 2). All specimens were prepared in conformity with applicable standards and tested under strictly controlled environmental and loading conditions to ensure data reliability and comparability.

Figure 2.

Experimental program.

2.3.1. Heating Regime

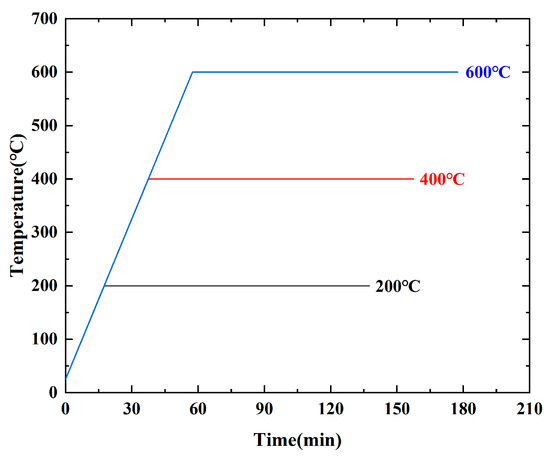

Before conducting mechanical evaluations, the experimental samples underwent thermal conditioning at predetermined high-temperature regimes. The thermal exposure was implemented using an LYL-17LBT chamber furnace (Luoyang Liyu Kiln Co., Ltd., Luoyang, China) capable of reaching a maximum of 1200 °C. Target thermal thresholds were selected at four distinct levels replicating various thermal exposure scenarios: ambient conditions, 200 °C, 400 °C, and 600 °C. A uniform thermal ramp rate of 10 °C per minute was maintained consistently throughout the heating phase. After achieving each predetermined thermal threshold, specimens were held isothermally for 120 min to guarantee homogeneous temperature distribution throughout the sample cross-sections. The heating program was ensured by adjusting the heating phase, set time, and temperature of the resistance furnace as shown in Figure 3. Monitoring the furnace temperature in real time on the control panel ensures that the heating program is followed. The post-heating protocol involved passive cooling within the sealed furnace until the specimens were equilibrated with room temperature conditions.

Figure 3.

The heating scheme.

2.3.2. SEM

To investigate thermal-induced alterations in the concrete’s microstructural properties, microstructural characterization was conducted utilizing a TESCAN MIRA4 field emission SEM, Tescan, Brno, Czech Republic. The specimen preparation methodology involved creating four distinct thermal exposure regimes (ambient conditions, 200 °C, 400 °C, and 600 °C) for each fiber variant, resulting in twelve specimens. Following standardized procedures, samples were cut into sections, meticulously polished, and coated with a thin gold layer using sputter deposition prior to being positioned within the SEM’s vacuum chamber. Comprehensive analysis encompassed microstructural features, void configurations, and interfacial adhesion between the fibers and cement-based matrix at multiple magnification levels. Through a systematic comparison of SEM micrographs across varying thermal conditions, this study elucidated thermal degradation effects on the concrete’s microarchitecture and the reinforcing efficiency of fibers under elevated temperatures.

2.3.3. Quasi-Static Splitting Tensile Test

The quasi-static splitting tensile strength test was performed in compliance with the specifications outlined in GB/T 50081-2019 [38]. Concrete cubes with a 100 mm side length were prepared for experimentation. The DY-3008DKD fully automated compression testing apparatus was utilized to ensure precise control during loading procedures. The specimen was subjected to axial loading at a steady stress rate of 0.05 MPa/s to failure. Detailed documentation included fracture patterns and peak load values, with subsequent data archiving. The splitting tensile resistance was determined through Equation (1):

where denotes the tensile splitting strength (MPa), F represents the failure load of the specimen (N), and A corresponds to the fractured surface area (mm2), determined by the cubic sample’s cross-section area of 100 mm by 100 mm. Triplicate measurements were performed for every fiber-temperature combination to ensure the statistical validity of the experimental data.

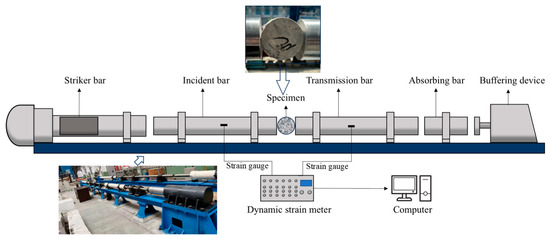

2.3.4. Dynamic Splitting Tensile Test

The dynamic mechanical performance was evaluated using an SHPB system. This system comprises three main components: bar assembly, a data acquisition unit, and processing systems. The bar assembly is composed of the following components: a striker bar, incident bar, transmission bar, and energy absorption bar, with lengths of 400 mm, 3200 mm, and 3200 mm, respectively. All bars were made of alloyed steel, and Young’s modulus was 700 GPa, and the longitudinal wave velocity was 5172 m/s. The data acquisition system incorporated dynamic strain gauges, and data processing was performed using a computer with dedicated software. A schematic of the dynamic splitting tensile loading configuration is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

SHPB test system.

Following the fundamental principles of one-dimensional stress wave propagation theory, the specimen’s dynamic tensile strength during split Hopkinson bar testing can be calculated using Equation (2):

In this equation, Fmax represents the peak force measured during loading, L denotes the specimen’s length dimension, D indicates its diameter, and Ae corresponds to the cross-sectional area of both the incident as well as transmission bars, with E signifying the elastic modulus of the bar material. The experimental setup utilized an SHPB system featuring 76 mm diameter bars. To examine strain rate sensitivity, dynamic splitting experiments were performed across three distinct strain rate conditions (achieved through impact gas pressures of 0.09 MPa, 0.12 MPa, and 0.15 MPa) for each fiber variety and temperature setting. Each strain rate condition underwent triplicate testing to ensure data reliability. Experimental observations included detailed recordings of dynamic stress–strain relationships and comprehensive documentation of specimen fracture patterns throughout the testing procedure.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Influence of High-Temperature Exposure on Crack Development in Concrete and the Inhibitory Effect of Fibers

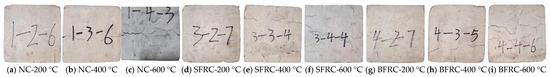

3.1.1. Macroscopic Damage Characteristics

Figure 5 presents the apparent changes in specimens after exposure to ambient conditions up to 600 °C and subsequent air cooling. The macroscopic damage morphology exhibited significant temperature dependence and fiber-induced effects on damage. At 200 °C, the surfaces of all specimens remained intact. Upon reaching elevated temperatures of 400 °C and 600 °C, the NC specimens developed long and wide penetrating cracks, demonstrating typical brittle failure characteristics. The incorporation of fibers markedly improved the crack morphology: SFRC exhibited cracks with relatively larger widths but shallower depths, whereas BFRC exhibited a fine and dense microcrack network. This indicates that fibers effectively restricted crack advancement and prevented defect coalescence, thereby preserving structural coherence under extreme thermal conditions. The color of the specimens changed to off-white to light gray after exposure to 600 °C, and the noticeable escape of water vapor observed at temperatures above 400 °C confirms both moisture evaporation and thermal decomposition of cementitious compounds.

Figure 5.

Apparent images of NC, SFRC and BFRC after elevated temperature.

3.1.2. Microscopic Mechanisms and Fiber Action

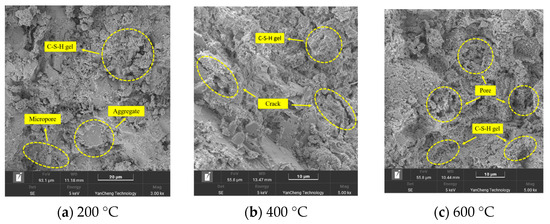

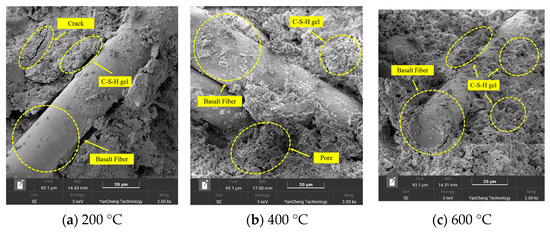

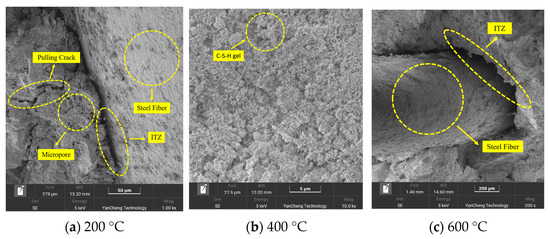

Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 display SEM analysis results for NC, SFRC, and BFRC specimens subjected to varying thermal exposure levels. Observations reveal the progressive degradation of NC’s microstructure, which became more pronounced as temperatures rose. Initial structural changes emerged at 200 °C with capillary pore formation due to free water evaporation. When exposed to 400 °C, calcium hydroxide decomposition produced vapor that generated internal pressure, exacerbating microcrack propagation and pore network expansion. The most severe deterioration occurred at 600 °C as C-S-H gel decomposition triggered structural disintegration and cohesion loss, directly correlating with mechanical property deterioration.

Figure 6.

SEM microstructures of NC.

Figure 7.

SEM microstructures of BFRC.

Figure 8.

SEM microstructures of SFRC.

The incorporation of fibers changed the mechanisms of failure. For SFRC, the failure mechanism was dominated by the fiber pull-out. The interfacial adhesion between steel fibers and the matrix was excellent at room temperature (25 °C). With increasing temperature, the microporosity in ITZ increased and the hydration products became loose and weakened. At 600 °C, the bonding strength between steel fibers and cement-based matrices was drastically destroyed and fiber pull-out was facilitated. The mechanical property enhancement of SFRC relies centrally on the bridging effect of the fibers on the cracks and the energy consumption during load transfer. The large amount of energy consumed by the steel fiber pull-out process is the reason why SFRC exhibits relatively superior mechanical properties. However, for BFRC, fiber rupture was the dominant failure mode, indicating that fiber–matrix interfacial bond strength at room temperature (25 °C) and at moderate temperature (200–400 °C) was superior to the tensile strength of basalt fibers. Even at 600 °C exposure, hydration products remained adhered to the basalt fiber surface, which indicates that some residual interfacial bond strength was still present, allowing the fibers to make contributions to a residual tensile strength even at high temperature.

Overall, fibers could inhibit the development of macroscopic cracks effectively by acting as bridges. Their high-temperature reinforcement performance was determined by the fiber–matrix interface and high-temperature stability of the fibers. The degradation of the fiber–matrix interfacial bonding strength was the essential cause of the decline in high-temperature performance in fiber-reinforced concrete.

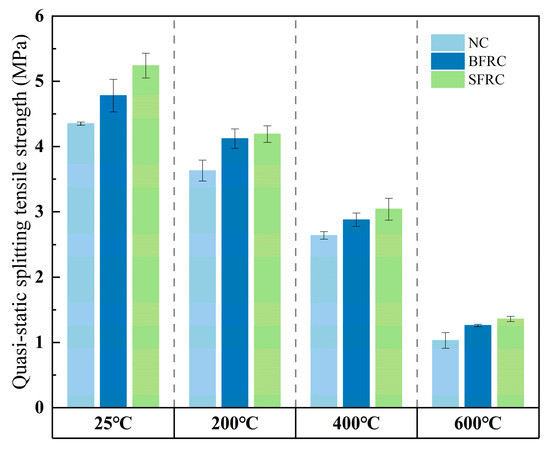

3.2. Quasi-Static Splitting Tensile Strength

Figure 9 displays the quasi-static splitting tensile strength tests of NC, BFRC, and SFRC after being subjected to four treatment temperatures: 25 °C, 200 °C, 400 °C, and 600 °C. All data are the average of three duplicates for reliability and statistical representation. Analysis indicates that when the treatment temperature is higher, the static splitting tensile strength of each of three kinds of specimens shows an evident and uniform decrease characteristic with respect to the corresponding deformation of the splitting tensile performance of the concrete matrix that is predominantly influenced by a high-temperature environment. For instance, NC specimens demonstrate a tensile strength drop from 4.35 MPa at 25 °C to 1.03 MPa at 600 °C, revealing a 76.3% decrease in load-bearing capacity. This strength degradation is primarily attributed to high-temperature-induced dehydration and the decomposition of C-S-H gel in the cement paste, the crystalline phase transformation of Ca(OH)2, the expansion of internal pores, and the propagation of microcracks. All of these factors collectively impair the matrix’s cohesion and interfacial bonding properties.

Figure 9.

Quasi-static splitting tensile strength.

Fiber-reinforced specimens (BFRC and SFRC) consistently outperform NC across all temperature ranges, with steel fibers showing greater reinforcement efficiency than basalt fibers in maintaining structural integrity. This indicates that the initiation and propagation of cracks in concrete can be successfully restrained by the “bridging effect” of fibers. Specifically, at 25 °C, the strength of SFRC (5.24 MPa) is 9.6% higher than that of BFRC (4.78 MPa) and 20.5% higher than that of NC (4.35 MPa). Even at 600 °C, SFRC maintains a residual strength of 1.36 MPa. Under the same conditions, this value is 32.0% higher than that of NC (1.03 MPa) and 7.9% higher than that of BFRC (1.26 MPa). These results demonstrate that steel fibers, owing to their superior high-temperature stability and superior interfacial bonding with the matrix, more effectively enhance the splitting tensile strength of concrete at both ambient temperature and elevated temperatures.

3.3. Dynamic Splitting Tensile Characteristics

3.3.1. Failure Pattern

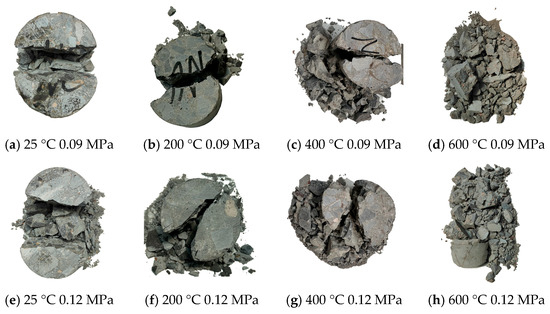

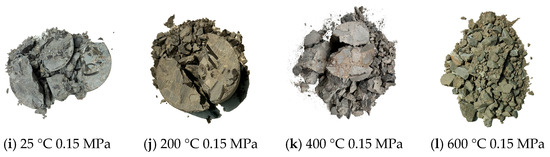

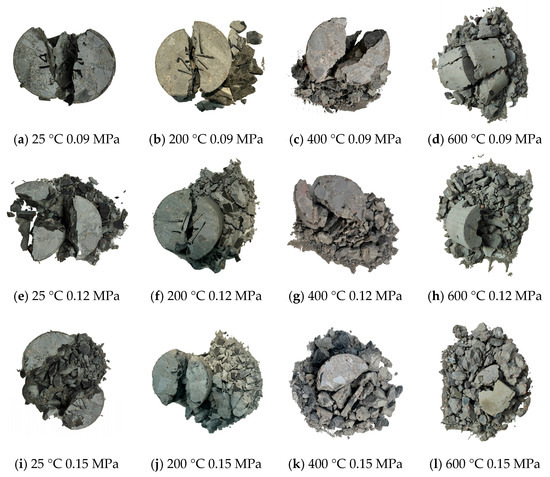

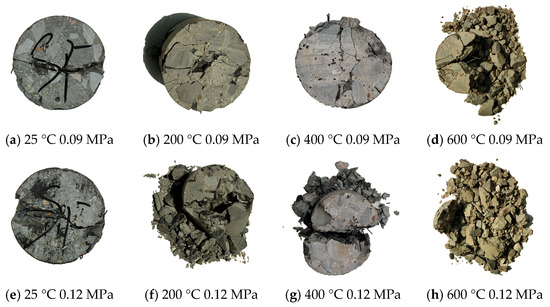

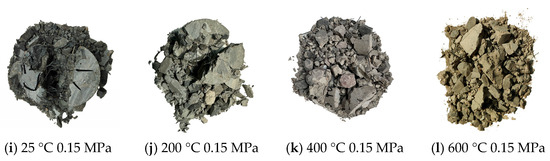

Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12 illustrate the failure morphologies of NC, SFRC, and BFRC after dynamic splitting tensile tests, respectively. The appearance of the specimens reveals that the failure modes of the three materials are notably influenced by both the treatment temperature and the impact air pressure, while material composition, particularly the type and presence of fibers, plays a dominant role in determining the failure morphology.

Figure 10.

Failure pattern of NC under different treatment temperatures and impact pressures.

Figure 11.

Failure pattern of BFRC under different treatment temperatures and impact pressures.

Figure 12.

Failure pattern of SFRC under different treatment temperatures and impact pressures.

At 25 °C, NC specimens exhibit typical brittle splitting failure, fracturing into 2–4 large blocks along the splitting surface. With rising impact air pressure, fine spalling at the edges of the fragments becomes more pronounced, which reflects the tendency of cracks to undergo rapid unstable propagation in concrete without fiber reinforcement under impact loading. In contrast, the fibrous reinforcement mechanisms efficiently restrain crack width and extension, with SFRC demonstrating a particularly notable performance. For example, under impact air pressures of 0.09 MPa and 0.12 MPa at 25 °C, SFRC specimens developed only 1–2 fine penetrating or non-penetrating microcracks, with no significant separation into large blocks. This highlights the superior interfacial anchorage and mechanical load transfer capability of steel fibers.

When the treatment temperature elevates to 400 °C and 600 °C, all three types of specimens exhibit high-temperature-induced deterioration, though the extent of degradation and failure modes vary with material type. NC shows the most pronounced response to elevated temperature; under 600 °C and 0.15 MPa impact, severe fragmentation occurs, with the specimen broken into multiple irregular small fragments and accompanied by a large amount of powdery debris. This behavior is mainly attributed to the high-temperature-induced dehydration of the cement paste, decomposition of Ca(OH)2, and loss of bonding at the aggregate–mortar interface. In BFRC, the softening of basalt fibers and degradation of the fiber–matrix interfacial bond at elevated temperatures (400–600 °C) limit our ability to restrain crack propagation, leading to fragmentation into medium and small fragments with minor spalling at the edges, though the amount of debris is noticeably less than that in NC. Under the same combined high-temperature and impact conditions, the fragment size of SFRC is markedly greater than that of BFRC and NC, suggesting that steel fibers can still maintain a certain degree of bridging and stress transfer capacity even at elevated temperatures, thus demonstrating superior high-temperature durability.

3.3.2. Dynamic Splitting Tensile Strength

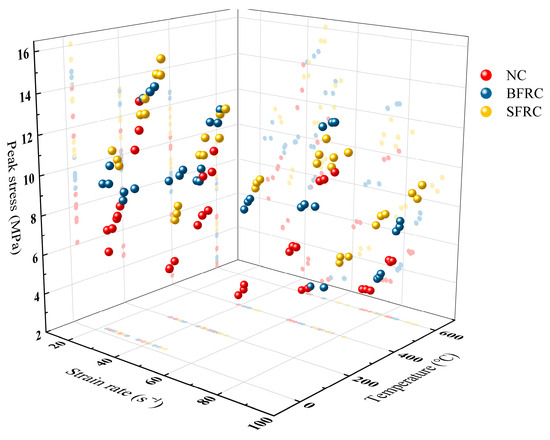

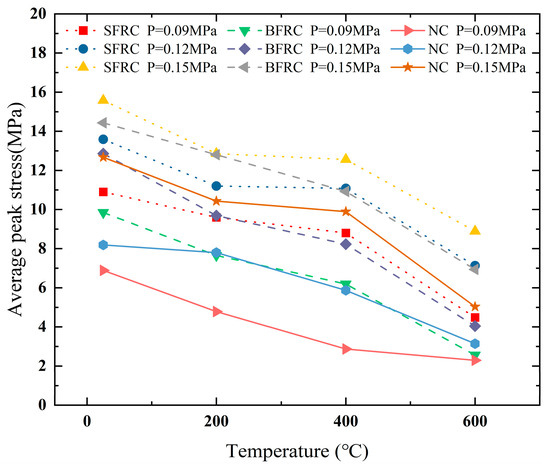

Based on the SHPB impact splitting tensile tests, a total of 108 valid datasets were obtained (as depicted in Table 3). The three-dimensional distribution of the strain rate, temperature, and peak stress is illustrated in Figure 13. The average peak stress variation trends for each of the three specimen types are depicted in Figure 14. The test results indicate that the dynamic splitting tensile strength (characterized by average peak stress) of all three specimen types is synergistically regulated by the strain rate and temperature effects. Furthermore, fiber type significantly affects both dynamic strength enhancement and resistance to the high-temperature degradation of materials.

Table 3.

Results of SHPB splitting tensile test.

Figure 13.

Distribution of data from SHPB splitting tensile test.

Figure 14.

Average peak stress of NC, BFRC, and SFRC under different conditions.

Overall, all specimens exhibited a notable enhancement in dynamic splitting tensile strength due to strain rate effects. In taking NC as an example, this effect remains pronounced even after exposure to 600 °C: as the impact air pressure increases from 0.09 MPa to 0.15 MPa, the average strain rate rises from 49.72 s−1 to 82.64 s−1, while the corresponding average peak stress increases from 2.29 MPa to 5.03 MPa, representing an increase of 120.0%. A similar trend is observed at 25 °C: when the strain rate increases from 24.42 s−1 to 37.46 s−1, the peak stress rises from 6.89 MPa to 12.67 MPa, which is an increase of 83.9%. In comparison, the strain rate effect is more stable in fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRC and SFRC). For instance, in SFRC treated at 400 °C, under 0.09 MPa impact air pressure, the average strain rate is 47.08 s−1 and the peak stress is 8.80 MPa; when the impact air pressure increases to 0.15 MPa and the strain rate rises to 77.91 s−1, the peak stress increases to 12.56 MPa, which is an increase of 42.7%. This strain rate-dependent strengthening behavior is consistent with findings reported in Refs. [39,40].

High-temperature treatment significantly degrades the dynamic strength of all three materials, but the extent of degradation varies considerably with fiber type—primarily due to differential damage mechanisms induced by high temperature on the cement matrix and fiber–matrix interface. NC exhibits the most severe high-temperature degradation: under 0.12 MPa impact air pressure, its peak stress decreases from 8.19 MPa at 25 °C to 3.14 MPa at 600 °C, which is a reduction of 61.7%. Even under a high impact air pressure of 0.15 MPa, the peak stress at 600 °C (5.03 MPa) is 60.3% lower than that at 25 °C (12.67 MPa). BFRC experiences high-temperature softening due to the glass transition of basalt fibers occurring between 400 °C and 500 °C, resulting in strength degradation intermediate between that of NC and SFRC: under 0.12 MPa impact air pressure, the peak stress decreases from 12.86 MPa at 25 °C to 4.04 MPa at 600 °C, where the degradation rate is 68.6%, with accelerated degradation above 400 °C, reflecting significant deterioration in fiber–matrix interfacial bond properties. SFRC demonstrates the best resistance to high-temperature degradation: under 0.12 MPa impact, the peak stress at 600 °C (7.13 MPa) is only 47.5% lower than that at 25 °C (13.59 MPa), with a degradation rate approximately 14.2% lower than that of NC and 21.1% lower than that of BFRC. Under the extreme condition of 600 °C and 0.15 MPa, the peak stress of SFRC (8.89 MPa) is 1.77 times and 1.28 times that of NC and BFRC under the same conditions, respectively, highlighting the effective constraining effect of steel fibers on crack propagation under high-temperature impact loading. Similar observations regarding the differential high-temperature degradation of fiber-reinforced concrete have been documented in Ref. [41].

The type of fiber emerges as a key determinant in maintaining the material’s high-temperature performance. Notably, at room temperature (25 °C), the reinforcing effect of fibers is already evident: under 0.09 MPa impact, the peak stress of SFRC (10.90 MPa) is approximately 10.7% higher than that of BFRC (9.85 MPa), indicating the superior interfacial bond and stress transfer efficiency of steel fibers. Under 0.15 MPa impact, the peak stresses of BFRC and SFRC are 14.43 MPa and 15.58 MPa, respectively—13.9% and 23.0% higher than that of NC (12.67 MPa)—further confirming the superior reinforcing advantage of steel fiber-reinforced concrete under impact loading. The underlying reason is that basalt fibers can effectively bridge cracks at room temperature. However, when the temperature exceeds 400 °C, fiber stiffness and strength plummeted, which is a common phenomenon. Therefore, its performance is better than that of NC, but inferior to that of SFRC. Steel fiber has a higher melting point and stability. The higher melting point and stability of steel fibers allow the fibers to consume a large amount of energy through the pull-out process even after the matrix has cracked.

In summary, the dynamic splitting tensile strength of NC, BFRC, and SFRC is synergistically regulated by the strain rate and temperature: the strain rate strengthening effect dominates strength enhancement, while high temperature induces strength degradation. Reinforcing materials with fibers effectively improves dynamic strength while significantly mitigating high-temperature degradation. Moreover, due to their excellent high-temperature stability and interfacial anchoring capability, steel fibers demonstrate significantly superior performance in both reinforcing effect and environmental adaptability compared to basalt fibers.

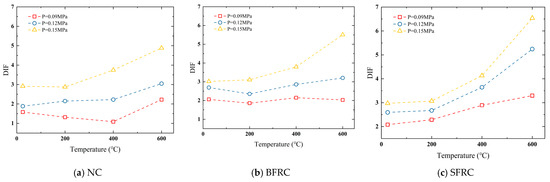

3.3.3. Dynamic Tensile Increase Factor

The Dynamic Increase Factor (DIF) serves as a critical metric quantifying the increase in material strength under dynamic loading compared to static conditions. This parameter is mathematically expressed through Equation (3):

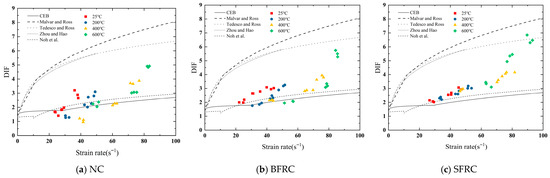

where denotes the dynamic tensile capacity, and represents the static tensile strength. As illustrated in Figure 15, the combined influence mechanism of the loading rate (controlled by impact pressure) and thermal conditions on the dynamic performance of NC, BFRC, and SFRC becomes evident. The DIF values are derived from the mean peak stresses documented in Table 3 and the baseline static strength measurements presented in Figure 9. Experimental findings indicate that adding fibers not only boosts the absolute magnitude of high-strain-rate resistance but also substantially improves the consistency of temperature-dependent strengthening effects across varying thermal environments.

Figure 15.

The average DIF of NC, BFRC, and SFRC.

Regarding the strain rate effect on DIF, at a given temperature, the DIF values for all three types of specimens increase monotonically as the impact air pressure rises from 0.09 MPa to 0.15 MPa. This increasing trend is more pronounced at elevated temperatures. Taking NC as an example, at 25 °C, the DIF increases from 1.58 at 0.09 MPa to 2.91 at 0.15 MPa, which is an increase of 84.2%. In contrast, at 600 °C, the DIF increases from 2.22 to 4.88, representing a significant rise of 119.8%. This indicates the increased brittleness of the thermally degraded concrete matrix and a relatively enhanced rate sensitivity under impact loading. BFRC and SFRC exhibit a similar trend of increasing DIF, but their DIF values are significantly higher than those of NC under identical temperature and pressure conditions. For instance, at 25 °C and 0.09 MPa, the DIF values for BFRC and SFRC are 2.06 and 2.08, respectively—approximately 30.4% and 31.6% higher than that of NC (1.58). This confirms that the stress-bridging and stress-dispersing effects of fibers effectively amplify the dynamic enhancement effect.

The DIF for each case in this study is greater than 1, indicating that for the same type of time, the strain rate effect still dominates over the range of temperatures and strain rates studied in this paper. The influence of temperature on DIF exhibits a complex characteristic of “suppression at medium temperatures (25–400 °C) and anomalous enhancement at high temperatures (above 400 °C),” with this behavior distinctly differentiated by fiber type. In the temperature range from 25 °C to 400 °C, the DIF values of NC generally show a fluctuating decrease. Particularly under 400 °C and 0.09 MPa, its DIF drops to 1.09, indicating that the dynamic strength is nearly equal to the static strength and the strain rate strengthening effect is essentially lost. In contrast, BFRC and SFRC maintain considerably higher DIF values of 2.15 and 2.89, respectively, at 400 °C, which are 1.97 and 2.65 times that of NC under the same conditions. This underscores the effectiveness of fibers in sustaining the dynamic enhancement effect at high temperatures. When the temperature rises beyond 400 °C to 600 °C, the DIF values for all three materials show significant recovery, with SFRC exhibiting the most superior potential for dynamic enhancement. Under 600 °C and 0.15 MPa, its DIF reaches as high as 6.54, which is 1.19 times that of BFRC (5.51) and 1.34 times that of NC (4.88). This phenomenon is due to two main reasons: firstly, SFRC retains a relatively higher residual static strength ratio at 600 °C (26.0% of its 25 °C value), compared to NC (23.7% of its 25 °C static strength) and BFRC (26.4% of its 25 °C static strength); secondly, steel fibers, due to effective interfacial anchoring and pull-out energy dissipation mechanisms, continue to facilitate dynamic stress transfer even under extreme temperatures, thereby enabling a greater relative increase in dynamic strength. This highlights the exceptional dynamic performance advantage of SFRC under high-temperature–impact coupled loading.

Numerous studies have explored the dynamic amplification patterns in cementitious composites, resulting in multiple predictive formulations. For concrete’s tensile dynamic strength enhancement factor (DIFt), the CEB-FIP Model Code proposes the following empirical relationship [42]:

where indicates the strain rate, and denotes the reference strain rate, taken as 3 × 10−6 s−1. , and indicates the static compressive strength, .

Malvar and Ross [43] argued that the CEB model underestimates the DIF at strain rates exceeding 10 s−1 and proposed that the strain rate transition point of the DIF formula should be at 1 s−1. They modified the aforementioned model with reference to their experimental data, proposing the following formula:

where , , and is the static compressive strength, .

Tedesco and Ross [44] summarized the following empirical relationship between DIF and the strain rate according to experimental data:

Based on numerical simulation results, Zhou and Hao [45] proposed the following DIF–strain rate relationship:

Noh et al. [46] systematically reviewed existing DIF models and further proposed a DIF prediction formula suitable for fiber-reinforced concrete based on the review:

Figure 16 compares the prediction curves of the aforementioned empirical formulas with the experimental results in this research. It is observed that the predictions from the models by Malvar [43], Tedesco [44], and Zhou et al. [45] are relatively close to each other, while the trends predicted by Noh et al. [46] and CEB models are comparatively conservative. However, none of the existing models satisfactorily match the test results obtained in this research. The reason lies in the fact that existing DIF prediction models primarily target the dynamic tensile behavior of ordinary concrete at room temperature, considering only the influence of the strain rate effect, and do not account for the combined effects of fiber type and high-temperature-induced strength degradation of concrete.

Figure 16.

The comparison of DIF empirical curve and test data in this study [43,44,45,46].

To address this limitation, derived from the experimental data of this study, an empirical expression for DIF is established that comprehensively accounts for the strain rate effects, temperature, and fiber type:

where parameters a, b, and c are fitting coefficients. The specific values of these coefficients and the determination coefficient (goodness of fit, R2) are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Fitting parameters and corresponding coefficient of determination for the DIF model proposed in this study.

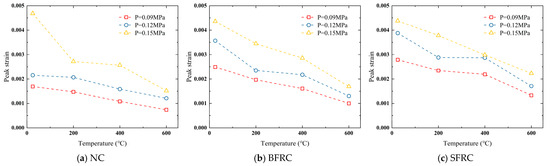

3.3.4. Peak Strain

Peak strain is a critical parameter characterizing the deformation capacity of a material when it reaches peak stress under impact loading. Figure 17 shows the average peak strains of NC, BFRC, and SFRC under different treatment temperatures and impact air pressures. The experimental data reveal that the average peak strains of NC, BFRC, and SFRC are synergistically regulated by both impact air pressure (strain rate) and treatment temperature. Furthermore, the incorporation of fibers notably improves the deformation capacity of concrete under combined high-temperature and impact conditions.

Figure 17.

The average peak strain of NC, BFRC, and SFRC.

At a given temperature, the average peak strain of all three types of specimens exhibits a monotonic increasing trend with rising impact air pressure, demonstrating a significant positive strain rate dependency. Taking the 25 °C condition as an example, when the impact air pressure increases from 0.09 MPa to 0.15 MPa, the peak strain of NC increases dramatically by 176.9%, while the growth rates for BFRC and SFRC are 74.8% and 57.1%, respectively. NC exhibits the most pronounced strain rate sensitivity, with its peak strain growth rate being substantially higher than that of fiber-reinforced concretes. This reflects that the bridging effect of fibers effectively constrains the deformation process and suppresses the unstable propagation of cracks under high-speed loading, thereby resulting in more stable deformation behavior.

In terms of the influence of treatment temperature, the peak strain of all specimens shows a significant decreasing trend as temperature increases. Under a constant impact air pressure, all three materials exhibit a reduction rate exceeding 50% when temperature increases from 25 °C to 600 °C (relative to their values at 25 °C), indicating that high temperature severely degrades the deformation capacity of the materials. However, under the extreme condition of combining elevated temperatures and intense impact air pressure, SFRC demonstrates the lowest reduction rate in peak strain. Its residual deformation capacity at elevated temperatures is significantly superior to that of BFRC and NC. The measured values exceed approximately those of BFRC by 31.8% and NC by 46.6%. This indicates that steel fibers, due to their excellent high-temperature stability and effective interfacial anchoring and pull-out energy dissipation mechanisms, can maintain better toughness in harsh environments. In contrast, the enhancing effect of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete diminishes noticeably with increasing temperature, primarily owing to the softening of basalt fibers at high temperatures.

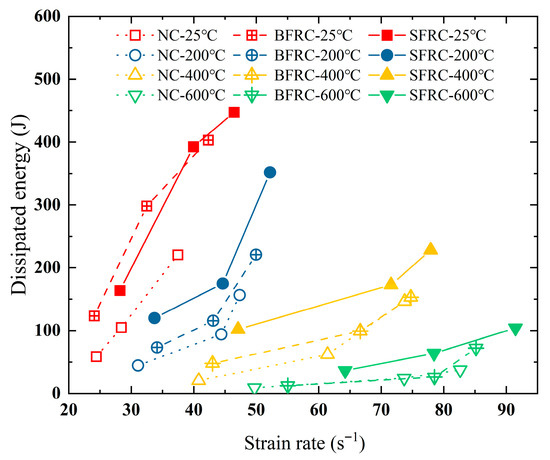

3.3.5. Energy Dissipation Capacity

Although energy dissipation is often used in structural engineering to evaluate the seismic performance of a monolithic structure or member under cyclic loading; it is also a key intrinsic parameter in the field of material impact dynamics used to characterize the dynamic impact toughness of the material itself. This parameter can comprehensively reflect the damage resistance and energy absorption potential of materials under high strain rates and has been widely used to evaluate the dynamic toughness of concrete-like materials [47,48]. In accordance with the principle of energy conservation and in adapting the analytical framework established by Hou et al. [49], the energy dissipation characteristics of concrete specimens subjected to dynamic loads can be determined through the analysis of pulse energy measurements obtained from SHPB experiments. The dissipated energy Wd is defined as the difference between the incident energy Wi and the sum of the reflected energy Wr and transmitted energy Wt. The dissipated energy Wd is mathematically formulated through the following fundamental energy balance equation:

The constituent energy components are computed using these relationships:

Here, , , and denote the elastic modulus, cross-sectional area, and elastic wave velocity of the SHPB, respectively; , , and correspond to the incident, reflected, and transmitted strain signals; and t indicates the time integration interval covering the entire pulse duration. This energy reflects the total energy consumed by the specimen during dynamic loading through mechanisms such as internal damage, crack propagation, and plastic deformation, serving as a critical indicator for evaluating the dynamic impact resistance of the material.

Utilizing the established energy quantification approach, the analysis results of the dissipated energy for NC, BFRC, and SFRC under different thermal treatments and impact pressures (strain rates) are illustrated in Figure 18. These results reveal the energy dissipation behavior and underlying failure mechanisms of the specimens during dynamic failure. The experimental results indicate that all three types of specimens exhibit a marked strain rate strengthening effect in terms of dynamic dissipated energy. Under the same temperature, the dissipated energy increases markedly with rising strain rate. For example, at 25 °C, when the average strain rate increases from approximately 24.42 s−1 to 37.46 s−1, the dissipated energy of NC increases from 58.61 J to 220.35 J, representing a 276% increase. The corresponding increases for BFRC and SFRC are 227% and 173%, respectively. It is noteworthy that although fiber-reinforced concretes exhibit higher absolute energy dissipation values, their growth rates are lower than that of NC. This reflects the role of fibers in suppressing brittle failure and moderating the energy absorption process, thereby rendering energy dissipation more stable and controllable [50].

Figure 18.

The dissipated energy of NC, BFRC, and SFRC.

High-temperature treatment significantly degrades the dynamic energy dissipation capacity of concrete. As the temperature increases from 25 °C to 600 °C, the dissipated energy of all specimens shows a decreasing trend, with NC experiencing the most severe degradation. For instance, at a strain rate of 73.75 s−1 (impact pressure of 0.15 MPa), the dissipated energy of NC at 400 °C is 146.39 J; however, at 600 °C and a strain rate of 82.64 s−1 (impact pressure of 0.15 MPa), its dissipated energy drops to 37.50 J, which is a reduction of 83.0%. This indicates that thermal degradation severely impairs the material’s ability to convert the strain rate effect into energy dissipation. By contrast, SFRC exhibits the best energy dissipation stability. Under the extreme condition of 600 °C and a high strain rate of 91.47 s−1, its dissipated energy reaches 104.12 J, which is 1.45 times and 2.78 times that of BFRC and NC, respectively, under the same temperature and impact air pressure. This highlights the ability of steel fibers to maintain efficient stress transfer and energy dissipation paths even under coupled high-temperature and high-strain-rate conditions [51].

4. Conclusions

This research comprehensively presents the mechanical performance and fracture characteristics of NC, BFRC, and SFRC materials exposed to coupled thermal (25–600 °C) and dynamic loading conditions. Principal findings include the following:

- (1)

- This study clarifies the evolution of the damage mode under the coupling of high temperature and dynamic loading. High temperature leads to microstructural deterioration of the concrete matrix, which is the fundamental cause of the macroscopic property degradation. The incorporation of fibers effectively inhibited crack development through the bridging effect, in which the steel fibers had the most significant inhibition effect due to their excellent thermal stability and interfacial properties, which could still maintain a good bonding and pull-out energy dissipation mechanism at high temperatures.

- (2)

- The experimental data quantified the synergistic effects of the strain rate (24–91 s−1) and temperature (25–600 °C) on the dynamic splitting strength and dissipated energy. All specimens showed a significant strain rate strengthening effect, while high temperatures triggered a deterioration in performance. Under extreme conditions (600 °C, 0.15 MPa), the dynamic splitting strength and dissipated energy of SFRC reached 1.77 and 2.78 times that of NC, respectively, highlighting the excellent ability of fibers, especially steel fibers, to maintain their properties in the high-temperature–high-strain-rate coupling field.

- (3)

- This study elucidated the differential regulation mechanism of fiber types on the dynamic properties and high-temperature stability of concrete. Steel fibers exhibited superior stress transfer and crack control at both room and high temperatures. In contrast, the performance decay of basalt fiber concrete increased above 400 °C, which was attributed to the glass transition of basalt fibers and the significant degradation of fiber–matrix interface properties. This provides a clear basis for fiber selection under different temperature conditions.

- (4)

- Regarding the existing DIF model that does not consider the coupling effect of high temperature and fiber, this study establishes an empirical DIF model based on the experimental data, which comprehensively considers the effects of strain rate, temperature, and fiber type. The goodness of fit (R2) of this model is higher than 0.85, meaning it can predict the dynamic reinforcement factor of fiber concrete after high temperature more accurately compared with the classical model and improve the performance prediction accuracy of this kind of material under complex working conditions.

In summary, this study systematically reveals the mechanical property evolution law and micro-mechanism of fiber concrete in the high-temperature–dynamic coupling field, and clarifies the performance advantage of steel fiber concrete under such extreme conditions. Based on the results of this study, future research can further focus on the systematic optimization of fiber dosage and the dynamic mechanical properties and synergistic enhancement mechanism of steel–basalt and other hybrid fiber concretes after high temperatures so as to provide a more comprehensive theoretical basis for the development of higher-performance high-temperature impact-resistant concrete materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D. (Jing Dong); methodology, J.D. (Juan Du) and G.C.; formal analysis, X.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D. (Jing Dong); writing—review and editing, S.Y.; funding acquisition—J.D. (Jing Dong) and S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Youth Fund of Rocket Force University of Engineering (grant no. 2022QN-B007) and Shaanxi Province Natural Science Basic Research Program Projects (grant no. 2025JC-YBQN-583).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, L.; Fang, Q.; Jiang, X.Q.; Ruan, Z.; Hong, J. Combined effects of high temperature and high strain rate on normal weight concrete. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2015, 86, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.K.; Wu, C.Q.; Liu, Z.X.; Liang, X.; Xu, S. Experimental investigation on the dynamic behaviors of UHPFRC after exposure to high temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 227, 116679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.R.; Xu, Q.J. Effect of elevated temperatures on compressive strength of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 229, 116846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, B.; Kelestemur, O. Effect of elevated temperature on the mechanical properties of concrete produced with finely ground pumice and silica fume. Fire Saf. J. 2010, 45, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascardi, A.; Verre, S.; Micelli, F.; Aiello, M.A. Durability-aimed performance of glass FRCM-confined concrete cylinders: Experimental insights into alkali environmental effects. Mater. Struct. 2025, 58, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watstein, D. Effect of straining rate on the compressive strength and elastic properties of concrete. ACI J. Proc. 1953, 49, 729–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff, P.H.; Perry, S.H. Compressive behaviour of concrete at high strain rates. Mater. Struct. 1991, 24, 425–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asprone, D.; Cadoni, E.; Prota, A. Experimental analysis on tensile dynamic behavior of existing concrete under high strain rates. ACI Struct. J. 2009, 106, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.J.; Geng, P.; Yang, Q.C.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, W.; He, C.; Zhang, J. Dynamic constitutive modeling of steel fiber reinforced concrete considering damage evolution under high strain rate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 440, 137433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Z.C.; Wu, J.; Du, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, W. Comparative analysis of dynamic mechanical properties of steel fiber reinforced concrete under ambient temperature and after exposure to high temperatures. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateshwaran, A.; Lai, B.L.; Liew, J.Y.R. Buckling resistance of steel fibre-reinforced concrete encased steel composite columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2022, 190, 107140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jin, C.J.; Wang, L.; Pan, L.; Liu, X.; Ji, S. Research on dynamic splitting damage characteristics and constitutive model of basalt fiber reinforced concrete based on acoustic emission. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 319, 126018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.B.; Wang, S.Y.; Lv, X.; Li, Y. Dynamic mechanical properties and damage constitutive model of frozen–thawed basalt fiber-reinforced concrete under wide strain rate range. Materials 2025, 18, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, B.L.; Li, Y.R.; Becque, J.; Zheng, Y.-Y.; Fan, S.-G. Axial compressive behavior of circular stainless steel tube confined UHPC stub columns under monotonic and cyclic loading. Thin Wall. Struct. 2025, 208, 112830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Shi, C.; Chen, X. Experimental and numerical study on tensile strength and failure pattern of high performance steel fiber reinforced concrete under dynamic splitting tension. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 259, 119796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Huo, Y.F.; Wang, N.; Sun, Z.; Bian, L.; Huang, R. Experimental study of dynamic tensile strength of steel-fiber-reinforced self-compacting concrete using modified Hopkinson bar. Materials 2023, 16, 5707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Pham, T.M.; Hao, H. Mechanical properties of high-strength concrete reinforced with hybrid basalt-polypropylene fibers under dynamic compression and split tension. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2024, 36, 04024210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Sun, X.J.; Yu, Z.P.; Lian, H. Study on the tensile properties of basalt fiber reinforced concrete under impact: Experimental and theoretical analysis. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2024, 24, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.Y.; Lin, X.S.; Zhou, A.N. A review of mechanical properties of fibre reinforced concrete at elevated temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 135, 106117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yang, F.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, L. Effect of elevated temperatures on behaviour of recycled steel and polypropylene fibre reinforced ultra-high performance concrete under dynamic splitting tension. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, G.J.; Pang, J.Y.; Tang, B.; Huang, J.; Sun, J. Experimental study on dynamic mechanical properties of hybrid fiber reinforced concrete at different temperatures. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.T.; Yu, H.F.; Ma, H.Y. Dynamic increase factor(DIF) of concrete with SHPB tests: Review and systematic analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 79, 107666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganorkar, K.; Goel, M.D.; Chakraborty, T. Specimen size effect and dynamic increase factor for basalt fiber-reinforced concrete using split Hopkinson pressure bar. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 04021364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Wu, B.; Du, X.Q.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, Z. Study on dynamic splitting tensile mechanical properties and microscopic mechanism analysis of steel fiber reinforced concrete. Structures 2023, 58, 105502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Liu, G.J.; Wang, J.H.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. Dynamic splitting performance and energy dissipation of steel fiber reinforced concrete. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 29, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wang, Z.H.; Wang, A.; Bai, E.; Zhu, X. Comparative study on the static and dynamic mechanical properties and micro-mechanism of carbon fiber and carbon nanofiber reinforced concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e01827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Lin, X.S.; Gravina, R.J. Evaluation of dynamic increase factor models for steel fibre reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 190, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 175-2007; Common Portland Cement. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- GB/T 39147-2020; Steel Fiber for Concrete. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- GB/T 23265-2023; Chopped Basalt Fiber for Cement Concrete and Mortar. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2023.

- JGJ 55-2011; Specification for Mix Proportion Design of Ordinary Concrete. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

- CECS 38-2004; Technical Specification for Fiber Reinforced Concrete Structures. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2004.

- JG/T 472-2015; Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Anandan, S.; Islam, S.; Khan, R.A. Effect of steel fibre profile on the fracture characteristics of steel fibre reinforced concrete beams. J. Eng. Res. 2019, 7, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Sun, Y.K.; Xu, J.G.; Wang, B. The effect of vibration mixing on the mechanical properties of steel fiber concrete with different mix ratios. Materials 2021, 14, 3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateshwaran, A.; Lai, B.L.; Liew, J.Y.R. Design of steel fiber-reinforced high strength concrete-encased steel short columns and beams. ACI Struct. J. 2021, 118, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JGJ/T 221-2010; Technical Specification for Application of Fiber Reinforced Concrete. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010.

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Concrete Physical and Mechanical Properties. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Ji, S.S.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.Y.; Li, X.; Ren, Y.; Zhen, S.; Cao, Z. Effect of steel fiber coupled with recycled aggregate concrete on splitting tensile strength and microstructure characteristics of concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2024, 36, 04024243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Zaland, S.; Tang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Hou, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. Strain rate effect on splitting tensile behavior and failure mechanisms of geopolymeric recycled aggregate concrete: Insights from acoustic emission characterization. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 102, 111970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.Q.; Gao, P.W.; Sun, X.W.; Li, G.; Li, F.; Shen, L.; Zhang, J. Research on the splitting tensile dynamic mechanics performance of post-high-temperature high-performance concrete. Structures 2024, 69, 107313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comite Euro-International Du Beton. CEB-FIP Model Code; Redwood Books: Pompano Beach, FL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Malvar, L.J.; Ross, C.A. Review of strain rate effects for concrete in tension. ACI Mater. J. 1998, 95, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, J.W.; Ross, C.A. Experimental and numerical analysis of high strain rates splitting tensile tests. ACI Mater. J. 1993, 90, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.Q.; Hao, H. Modeling of compressive behaviour of concrete-like materials at high strain rates. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2008, 45, 4648–4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, H.W.; Truong, V.D.; Cho, J.Y.; Kim, D.J. Dynamic increase factors for fiber-reinforced cement composites: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 56, 104769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Y.; Deng, Y.J.; Liu, L.B.; Zhang, L.; Yao, Y. Dynamic mechanical properties and energy dissipation analysis of rubber-modified aggregate concrete based on SHPB tests. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 445, 137920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.L.; Ning, J.G.; Xu, X.Z. Analysis of fragmentation failure behavior and energy dissipation characteristics of negative-temperature curing concrete under impact loading. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 175, 109572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.M.; Cao, S.J.; Zhang, W.Z.; Rong, Q.; Li, G. Experimental study on dynamic compressive properties of fiber-reinforced reactive powder concrete at high strain rates. Eng. Struct. 2018, 169, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.Y.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.H. Self-sensing capability of ultra-high-performance concrete containing steel fibers and carbon nanotubes under tension. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2018, 276, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhong, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M. Behaviour of recycled tyre polymer fibre reinforced concrete under dynamic splitting tension. Cem. Concr. Comp. 2020, 114, 103764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).