Time-Based Fire Resistance Performance of Axially Loaded, Circular, Long CFST Columns: Developing Analytical Design Models Using ANN and GEP Techniques

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fire Performance of CFST Columns and Literature Review

2.1. Behavior of CFST Columns Under Fire

- −

- First stage: Steel expands faster than concrete because it is a material with a higher thermal expansion coefficient and heats up more quickly. Therefore, the longitudinally expanding steel tube carries most of the load. Subsequently, a gap forms between the transversely expanding steel and the concrete, and heat transfer to the concrete slows down.

- −

- Second stage: Steel rapidly shortens due to the load it bears and the increase in temperature, which causes its yield strength to decrease, and at a certain point, it can no longer bear the load. The rapid shortening and shrinkage of steel within approximately 20–30 min causes the load to be transferred to the concrete core.

- −

- Third stage: Due to the low thermal conductivity of concrete, the temperature increase in the element begins to slow down. In this stage, the concrete core begins to carry more load. The concrete core continues to carry the load until the deterioration of the concrete reaches a certain level.

- −

2.2. Fire Test Method

2.3. Effect of Parameters on Fire Resistance

- Effect of cross-section area: Yin et al. [2] examined the effect of cross-section area on fire resistance in their study comparing the fire resistance of square and circular CFST columns. In general, it has been reported that fire resistance decreases as the cross-sectional area decreases. Similarly, in Lie and Chabot’s study [10], one of the parameters used in investigating the fire resistance of plain square- and circular-section CFST columns was the cross-sectional area. The study reported that increasing cross-sectional dimensions resulted in higher fire resistance. Han et al. [27] investigated the behavior of axially loaded square- and circular-section CFST columns under standard fire test conditions. Their study reported that section size had a significant effect on fire resistance and that fire resistance increased significantly with increasing section size. As the section size increased from 300 mm to 1200 mm, the fire resistance increased from 83 min to 188 min for the circular section. This was attributed to faster heat transfer and quicker deterioration in columns with smaller cross-sectional areas.

- Effect of steel tube wall thickness (ts): Lie and Chabot [10] conducted experimental studies to determine the fire resistance of square and circular CFST columns. One of the parameters in this study was the steel tube wall thickness. It was reported that increasing the steel tube thickness from 4.78 mm to 6.35 mm for columns tested under the same load increased the fire resistance from 76 min to 81 min. However, two different sample tests yielded opposite results, reporting that increasing the steel tube thickness decreased the fire resistance. Within the scope of this study, it was stated that the thickness of the steel tube had very little effect on fire resistance.

- Effect of concrete compressive strength (fc): The literature presents varying results regarding concrete compressive strength. Mao et al. [11] investigated the effect of concrete strength on the fire resistance of CFST columns. The study was conducted on steel-reinforced CFST columns and reported that increasing concrete strength from 30 MPa to 60 MPa resulted in an 11% decrease in fire resistance. They attributed this result to the gradual decrease in concrete strength with increasing temperature and the greater loss in strength at high temperatures. In their experimental studies, Wang and Young [12] reached a conclusion contrary to the findings of Mao et al. [11]. It was reported that in CFST columns with the same material and dimensional properties, increasing the concrete strength from 30 MPa to 50 MPa increased fire resistance from 151 min to 227 min. Han et al. [27] investigated the effect of concrete strength on the fire resistance of CFST columns. They concluded that when columns have relatively small cross-sectional dimensions, concrete strength has a moderate effect on fire resistance, while in columns with larger cross-sectional dimensions, fire resistance generally increases significantly with increasing concrete strength.

- Effect of steel yield strength (fsy): Wang and Young [12] also examined the effect of steel strength in the same study. They reported a fire resistance of 151 min when the steel strength was 275 MPa, 73 min when it was 460 MPa, and 46 min when it was 690 MPa. Xiong and Liew [28] conducted experimental and analytical studies on the fire resistance of CFST columns. They reported that fire resistance decreased by up to 21% with increasing steel strength.

- Effect of load ratio (μ): Lie and Chabot [10] conducted an experimental study examining the effect of load level on the fire resistance of square and circular CFST columns. As a result of the study, it was reported that fire resistance decreased as the load level increased. It was reported that increasing the load level of a sample from 74% to 141% reduced the fire resistance from 133 min to 70 min. Wang and Young [12] reported that the fire resistance of columns decreased as the load level increased. They reported that the fire resistance of two columns of the same dimensions and materials decreased from 151 min to 54 min when the load level was increased from 0.3 to 0.5. The studies concluded that the load level has a significant effect on the fire resistance of columns, and this effect is observed relatively more in columns with larger diameters.

3. Previous Approaches

4. Description of the Dataset

5. Overview of Soft Computing Techniques

5.1. Genetic Expression Programming (GEP)

5.2. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)

6. Development of GEP and ANN Models

6.1. GEP Model

- −

- d0: Diameter of the circular steel tube (D);

- −

- d1: Wall thickness of the steel tube (ts);

- −

- d2: Twenty-eight-day concrete cylinder strength (fc);

- −

- d3: Yield strength of the steel tube (fsy);

- −

- d4: Slenderness ratio (L/D);

- −

- d5: Load ratio (μ).

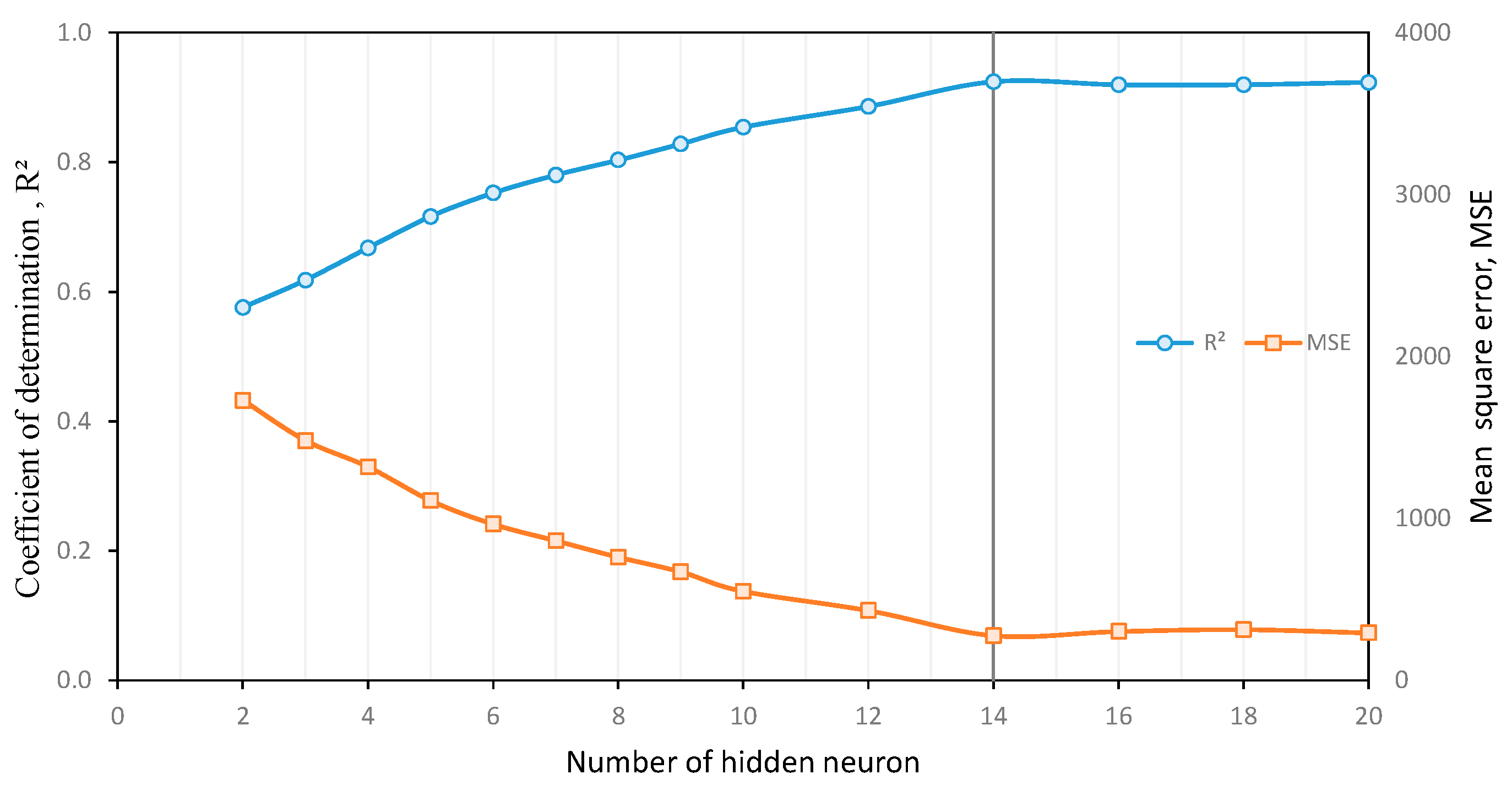

6.2. ANN Model

7. Results and Discussion

7.1. Independent Validation with Synthetic Data

- -

- Circular steel tube diameter (D): Between 141.3 mm and 390.5 mm (ave: 272.4 mm).

- -

- Steel tube wall thickness (ts): Between 2.95 mm and 10.55 mm (ave: 6.35 mm).

- -

- Twenty-eight-day concrete cylinder strength (fc): Between 23.5 MPa and 48.4 MPa (ave: 34.6 MPa).

- -

- Steel tube yield strength (fsy): Between 267.7 MPa and 451.0 MPa (ave: 338.5 MPa).

- -

- Slenderness ratio (L/D): Between 9.6 and 27.0 (ave: 14.9).

- -

- Load ratio (μ): Between 0.12 and 0.59 (ave: 0.30).

- -

- Time-dependent fire performance (t): Between 39.3 min and 230.7 min (ave: 103 min).

- -

- GEP Model: MSE value of 496 min2 and MAE value 18.3 min.

- -

- ANN Model: MSE value of 569 min2 and MAE value of 17.8 min.

7.2. Graphical and R2 Assessment

Model Comparison

7.3. Assessment of Statistical Parameters

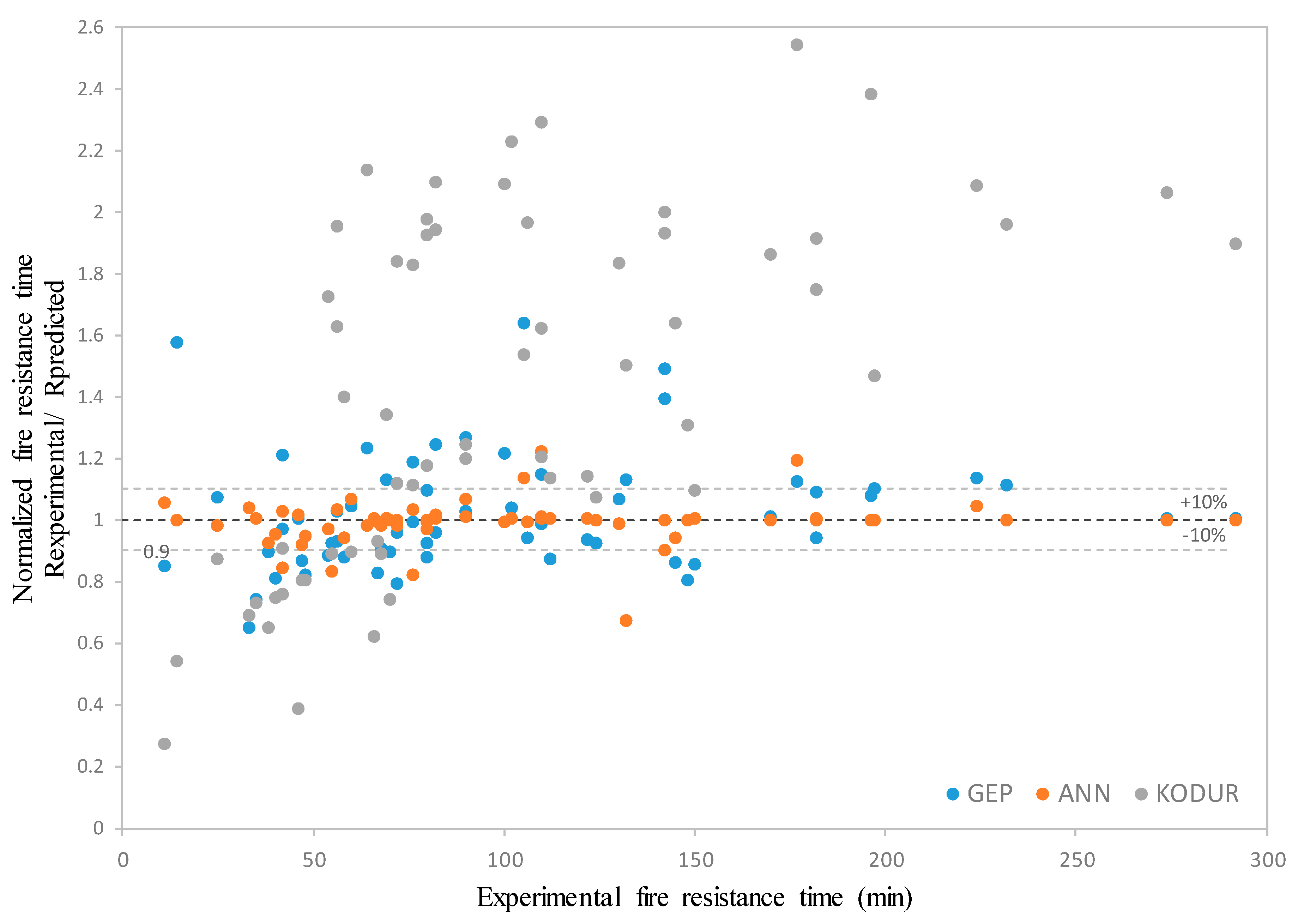

7.4. Comparison of Normalized Results

7.5. Sensitivity Analysis Based on Input Parameters

8. Conclusions

- The prediction performance of the developed GEP and ANN design models was compared with that of the existing Kodur model (R2 = 0.549), and it was found that the new models demonstrated significantly superior prediction accuracy.

- As a result of the statistical evaluations performed, it was determined that the ANN-based design model had the highest prediction performance. The ANN model stood out with a coefficient of determination (R2) value of 0.972 and the lowest MAPE = 4.41.

- According to the nRMSE classification, the ANN model fell into the excellent performance category with a value of 0.10 (between 0 and 0.1), while the GEP-based model was observed to fall into the good performance category with an R2 value of 0.937 and an nRMSE value of 0.15.

- The reliability and generalization ability of the models were examined in terms of fitness function (f) and performance index (PI) values; the ANN (f = 1.13; PI = 0.05) and GEP (f = 1.19; PI = 0.08) models proved to be statistically convincing and reliable by providing values suitable for the expected targets (f ≈ 1; PI ≈ 0).

- The study revealed that existing design formulas can generally only estimate residual axial load-carrying capacity and cannot predict time-dependent fire performance. However, it was concluded that by developing GEP and ANN models using a wide range of data, the fire resistance duration can be reliably estimated even in situations where the Kodur model has limitations.

Limitation of the Developed Models

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- İpek, S.; Güneyisi, E.M. Nonlinear finite element analysis of double skin composite columns subjected to axial loading. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2020, 20, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Zha, X.; Li, L. Fire resistance of axially loaded concrete filled steel tube columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2006, 62, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, D.; Bisby, L.; Jowsey, A.; Melandinos, A.; Lane, B. Structural performance of unprotected concrete-filled steel hollow sections in fire: A review and meta-analysis of available test data. Steel Compos. Struct. 2012, 12, 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moradi, M.J.; Daneshvar, K.; Ghazi-nader, D.; Hajiloo, H. The prediction of fire performance of concrete-filled steel tubes (CFST) using artificial neural network. Thin-Walled Struct. 2021, 161, 107499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, X.; Du, Y.; Chen, Z.; Xiong, Q. Axial compression behavior of high-strength CFST column with localized accelerated corrosion defects. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 495, 143645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneyisi, E.M.; Gültekin, A.; Mermerdaş, K. Ultimate capacity prediction of axially loaded CFST short columns. Int. J. Steel Struct. 2016, 16, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhatmey, I.A.H. Residual Strength Capacity of Fire-Exposed Concrete-Filled Steel Tube Columns. Ph.D. Dissertation, Gaziantep University, Gaziantep, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Song, T.-Y.; Han, L.-H.; Yu, H.-X. Concrete filled steel tube stub columns under combined temperature and loading. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2010, 66, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; He, J.; Xiao, Y. Fire behavior and performance of concrete-filled steel tubular columns: Review and discussion. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2019, 157, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, T.T.; Chabot, M. Experimental Studies on the Fire Resistance of Hollow Steel Columns Filled with Plain Concrete; Research Report No. 611 (NRC Publications Archive, Institute for Research in Construction); National Research Council of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1992.

- Mao, W.-J.; Wang, W.-D.; Xian, W. Numerical analysis on fire performance of steel-reinforced concrete-filled steel tubular columns with square cross-section. Structures 2020, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Young, B. Fire resistance of concrete-filled high strength steel tubular columns. Thin-Walled Struct. 2013, 71, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1994-1-2; Eurocode 4: Design of Composite Steel and Concrete Structures—Part 1.2: General Rules—Structural Fire Design. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- Kodur, V. Guidelines for fire resistant design of concrete-filled steel HSS columns—State-of-the-art and research needs. Int. J. Steel Struct. 2007, 7, 173–182. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285739797_Guidelines_for_fire_resistant_design_of_concrete-filled_steel_HSS_columns_-_State-of-the-art_and_research_needs (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Moore, D.; Bailey, C.; Lennon, T.; Wang, Y. Designers Guide to EN 1991-1-2, EN 1992-1-2, EN 1993-1-2 and EN 1994-1-2; Thomas Telford Publishing: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aribert, J.M.; Renaud, C.; Zhao, B. Simplified fire design for composite hollow-section columns. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Struct. Build. 2008, 161, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Orton, A. Fire resistant design of concrete filled tubular steel columns. Struct. Eng. 2008, 86, 40–45. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/251422066_Fire_resistant_design_of_concrete_filled_tubular_steel_columns (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Espinós, A.; Romero, M.; Hospitaler, A. Simple calculation model for evaluating the fire resistance of unreinforced concrete filled tubular columns. Eng. Struct. 2012, 42, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANUHT. Fire Resistance Design of Non-Insulated CFT Columns—Guidelines, Technical Explanations and Design Examples; Association of New Urban Housing Technology: Tokyo, Japan, 2004. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kodur, V.K.R. Performance-based fire resistance design of concrete-filled steel columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 1999, 51, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Soft computing and fuzzy logic. IEEE Softw. 1994, 11, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İpek, S.; Güneyisi, E.M. Application of Eurocode 4 design provisions and development of new predictive models for eccentrically loaded CFST elliptical columns. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 48, 103945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 834; Fire-Resistance Tests—Elements of Building Construction. International Organization for Standardization: Cham, Switzerland, 1975.

- Lu, H.; Zhao, X.-L.; Han, L.-H. Fire behaviour of high strength self-consolidating concrete filled steel tubular stub columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2009, 65, 1995–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukanwa, K.U.; Lim, J.B.P.; Sharma, U.K.; Hicks, S.J.; Abu, A.; Charles Clifton, G. Behaviour of continuous concrete filled steel tubular columns loaded eccentrically in fire. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2017, 139, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özelmacı Durmaz, Ç.Ö.; İpek, S.; Nassani, D.E.; Mete Güneyisi, E. Beton dolgulu çelik tüp kolonların yangın performansının araştırılması. Kahramanmaraş Sütçü İmam Üniversitesi Mühendislik Bilim. Derg. 2023, 26, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.-H.; Chen, F.; Liao, F.-Y.; Tao, Z.; Uy, B. Fire performance of concrete filled stainless steel tubular columns. Eng. Struct. 2013, 56, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.X.; Liew, J.Y.R. Fire Resistance of High-Strength Steel Tubes Infilled with Ultra-High-Strength Concrete Under Compression. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2021, 176, 106410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50936; Technical Code for Concrete Filled Steel Tubular Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2014.

- GB 51249; Code for Fire Safety of Steel Structures in Building. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Li, Z.; Ding, F.; Cheng, S.; Lyu, F. Mechanical behavior of steel-concrete interface and composite column for circular CFST in fire. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2022, 196, 107424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, M.L.; Moliner, V.; Espinos, A.; Ibañez, C.; Hospitaler, A. Fire behavior of axially loaded slender high strength concrete-filled tubular columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2011, 67, 1953–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Ghannam, M.; Song, T.-Y.; Han, L.-H. Experimental and numerical investigation of concrete-filled stainless steel columns exposed to fire. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2016, 118, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodur, V.K.R.; Lie, T. Experimental Studies on the Fire Resistance of Circular Hollow Steel Columns Filled with Steel-Fibre-Reinforced Concrete; Research Report No. 691 (NRC Publications Archive, Institute for Research in Construction); National Research Council: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1995.

- Harmathy, T.Z.; Sultan, M.A.; MacLaurin, J.W. Comparison of severity of exposure in ASTM E 119 and ISO 834 fire resistance tests. J. Test. Eval. 1987, 15, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, I.E.; Todeschini, R. The Data Analysis Handbook; Elseiver: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gandomi, A.H.; Roke, D.A. Assessment of artificial neural network and genetic programming as predictive tools. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2015, 88, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, F.E.; Xu, Y.; Iqbal, M.; Javed, M.F.; Jamhiri, B. Predictive modeling of swell-strength of expansive soils using artificial intelligence approaches: ANN, ANFIS and GEP. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 289, 112420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandomi, M.; Soltanpour, M.; Zolfaghari, M.R.; Gandomi, A.H. Prediction of peak ground acceleration of Iran’s tectonic regions using a hybrid soft computing technique. Geosci. Front. 2016, 7, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamian, S.A.; Eskandari-Naddaf, H. Effect of porosity on predicting compressive and flexural strength of cement mortar containing micro and nano-silica by ANN and GEP. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 218, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khan, M.; Khan, W.A.; Afridi, M.A.; Naseem, K.A.; Noreen, A. Predicting pile bearing capacity using gene expression programming with SHapley Additive exPlanation interpretation. Discov. Civ. Eng. 2025, 2, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, M.Z. A Look into How Machine Learning is Reshaping Engineering Models: The Rise of Analysis Paralysis, Optimal yet Infeasible Solutions, and the Inevitable Rashomon Paradox. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.04894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, M.Z. A step-by-step tutorial on machine learning for engineers unfamiliar with programming. AI Civ. Eng. 2025, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, L.; Du, G.; Hou, Q. Prediction of the Compressive Strength of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Based on Artificial Neural Network. Materials 2021, 14, 3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğan, A.; İpek, S.; Mermerdaş, K.; Güneyisi, E.M.; Güneyisi, E. Analytical design models in construction engineering: Artificial neural network and gene expression programming practices. In Digital Transformation in the Construction Industry: Sustainability, Resilience, and Data-Centric Engineering; Farsangi, E.N., Noori, M., Yang, T.Y., Sarhosis, V., Mirjalili, S., Skibniewski, M.J., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ersoy, U.; Özcebe, G.; Tankut, T. Reinforced Concrete; METU Press: Ankara, Türkiye, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mindess, S. Developments in the Formulation and Reinforcement of Concrete; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Falcone, R.; Lima, C.; Martinelli, E. Soft computing techniques in structural and earthquake engineering: A literature review. Eng. Struct. 2020, 207, 110269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, D. An overview of soft computing. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 102, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İpek, S.; Güneyisi, E.M. Ultimate axial strength of concrete-filled double skin steel tubular column sections. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 6493037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems: An Introductory Analysis with Applications to Biology, Control, and Artificial Intelligence; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, N.L. A representation for the adaptive generation of simple sequential programs. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Genetic Algorithms and Their Applications; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Koza, J. On the Programming of Computers by Means of Natural Selection, Genetic Programming; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, C. Gene expression programming: A new adaptive algorithm for solving problems. Complex Syst. 2001, 13, 87–129. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/cs/0102027 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- İpek, S.; Güneyisi, E.; Güneyisi, E.M. Data-driven models for prediction of peak strength of R-CFST circular columns subjected to axial loading. Structures 2022, 46, 1863–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İpek, S.; Güneyisi, E.M.; Mermerdaş, K.; Algın, Z. Optimization and modeling of axial strength of concrete-filled double skin steel tubular columns using response surface and neural-network methods. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 103128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zekić-Sušac, M.; Šarlija, N.; Benšić, M. Selecting neural network architecture for investment profitability predictions. J. Inf. Organ. Sci. 2012, 29, 83–95. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291967814_Selecting_neural_network_architecture_for_investment_profitability_predictions (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- İpek, S.; Erdoğan, A.; Güneyisi, E.M. An artificial intelligence-based design model for circular CFST stub columns under axial load. Steel Compos. Structures 2022, 44, 119–139. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362231045_An_artificial_intelligence-based_design_model_for_circular_CFST_stub_columns_under_axial_load (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- GeneXproTools 5.0. GepSoft. 2018. Available online: http://www.gepsoft.com/ (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- MatlabV.R2018. MathWorks. 2018. Available online: http://www.mathworks.com/help/ (accessed on 13 July 2023).

- Kazemi, F.; Asgarkhani, N.; Ghanbari-Ghazijahani, T.; Jankowski, R. Ensemble machine learning models for estimating mechanical curves of concrete-timber-filled steel tubes. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 156, 111234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poornamazian, H.A.; Izadinia, M. Prediction of compressive strength of brick columns confined with FRP, FRCM, and SRG system using GEP and ANN methods. J. Eng. Res. 2024, 12, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Fakharian, P.; Eidgahee, D.R.; Haji, M.; Alizadeh Arab, A.M.; Nouri, Y. Axial compressive strength predictive models for recycled aggregate concrete filled circular steel tube columns using ANN, GEP, and MLR. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 77, 107439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sources | # | D (mm) | ts (mm) | fc (MPa) | fsy (MPa) | L/D | µ | R (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lie and Chabot [10] | 37 | 141.3–406.4 | 4.78–12.70 | 23.5–90.5 | 300.0–350.0 | 9.4–27.0 | 0.09–0.45 | 46–292 |

| Kodur and Lie [34] | 5 | 323.9–406.4 | 6.35 | 41.2–43.2 | 300.0 | 9.4–11.8 | 0.35–0.67 | 66–224 |

| Romero et al. [32] | 5 | 159.0 | 6.00 | 28.6–71.1 | 337.8–341.4 | 20.0 | 0.20–0.60 | 11–14 |

| Han et al. [27] | 2 | 300.0 | 5.00 | 53.2 | 451.0 | 12.0 | 0.30–0.45 | 67–132 |

| Tao et al. [33] | 2 | 195.6–196.2 | 2.95 | 40.3 | 292.9 | 9.5–9.6 | 0.31–0.48 | 122–197 |

| Li et al. [31] | 11 | 230.6–314.5 | 4.81–7.81 | 30.0–50.0 | 235.0–420.0 | 12.1–16.5 | 0.30–0.40 | 33–80 |

| P1: Function set | +, −, *, /, Sqrt, ln, X2, 3Rt, tan |

| P2: Number of generations | 998,975 |

| P3: Chromosomes | 300 |

| P4: Head size | 15 |

| P5: Number of genes | 12 |

| P6: Linking function | Addition |

| P7: Mutation rate | 0.00138 |

| P8: Inversion rate | 0.00546 |

| P9: One-point recombination rate | 0.00277 |

| P10: Two-point recombination rate | 0.00277 |

| P11: Gene recombination rate | 0.00277 |

| P12: Gene transposition rate | 0.00277 |

| P13: Constants per gene | - |

| Input and Output Variables | Normalization Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| βmax | βmin | a | b | |

| D (mm) | 406.4 | 141.3 | 0.007544 | −2.06601 |

| ts (mm) | 12.7 | 2.95 | 0.205128 | −1.60513 |

| fc (MPa) | 90.5 | 23.5 | 0.029851 | −1.70149 |

| fsy (MPa) | 451 | 235 | 0.009259 | −3.17593 |

| L/D | 27 | 9.4 | 0.113636 | −2.06818 |

| µ | 0.67 | 0.09 | 3.448276 | −1.31034 |

| t (min) | 292 | 11 | 0.007117 | −1.07829 |

| Design Models | Statistical Parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAPE | nRMSE | f | PI | R2 | |

| Kodur | 41.81 | 0.52 | 2.35 | 0.30 | 0.549 |

| GEP | 12.96 | 0.15 | 1.22 | 0.08 | 0.937 |

| ANN | 4.41 | 0.10 | 1.13 | 0.05 | 0.972 |

| Parameter | Description | Unit | Reliable Application Range (Minimum–Maximum) | Data Density/Preferred Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | Circular steel tube diameter | mm | 141.3–406.4 | The entire dataset |

| ts | Steel tube wall thickness | mm | 2.95–12.7 | The range of 4.00–8.50 mm has significantly denser data |

| fc | 28-day concrete cylinder strength | MPa | 23.5–90.5 | The range of 23.5–55.0 MPa has significantly denser data |

| fsy | Steel tube yield strength | MPa | 235–451 | The range of 278–356 MPa has significantly denser data |

| L/D | Slenderness ratio | - | 9.4–27 | The entire dataset |

| μ | Load ratio | - | 0.09–0.67 | The range of 0.09–0.48 has significantly denser data |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Özelmacı Durmaz, Ç.Ö.; İpek, S.; Nassani, D.E.; Mete Güneyisi, E. Time-Based Fire Resistance Performance of Axially Loaded, Circular, Long CFST Columns: Developing Analytical Design Models Using ANN and GEP Techniques. Buildings 2025, 15, 4415. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244415

Özelmacı Durmaz ÇÖ, İpek S, Nassani DE, Mete Güneyisi E. Time-Based Fire Resistance Performance of Axially Loaded, Circular, Long CFST Columns: Developing Analytical Design Models Using ANN and GEP Techniques. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4415. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244415

Chicago/Turabian StyleÖzelmacı Durmaz, Ç. Özge, Süleyman İpek, Dia Eddin Nassani, and Esra Mete Güneyisi. 2025. "Time-Based Fire Resistance Performance of Axially Loaded, Circular, Long CFST Columns: Developing Analytical Design Models Using ANN and GEP Techniques" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4415. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244415

APA StyleÖzelmacı Durmaz, Ç. Ö., İpek, S., Nassani, D. E., & Mete Güneyisi, E. (2025). Time-Based Fire Resistance Performance of Axially Loaded, Circular, Long CFST Columns: Developing Analytical Design Models Using ANN and GEP Techniques. Buildings, 15(24), 4415. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244415