Abstract

Ensuring the sufficient strength of concrete structures and buildings exposed to constant humidity is of great importance in hydraulic engineering, as increased humidity reduces the strength of concrete and ultimately destroys it. Although the static strength of concrete has been thoroughly studied, its impact strength, including that in a wet state, remains unexplored. This is especially relevant for modified concretes, for which there are no experimental data on the effect of moisture on their strength characteristics. This article presents the results of an experimental quantitative assessment of the static and impact strength of polymer–cement fiber-reinforced concrete under water saturation conditions. The aim of this study was to determine the influence of polymer components and fiber reinforcement on changes in concrete strength under increased and prolonged exposure to moisture. A comparative assessment of the static and impact strength of concrete samples in dry and water-saturated conditions was conducted. It was found that the addition of polymeric materials reduces water absorption and increases the impact strength of concrete. Their combined use with fibers ensures the preservation of strength properties in conditions of high concrete humidity. The results can be used in the development of moisture-resistant concrete compositions for hydraulic structures and other facilities operating in aquatic environments.

1. Introduction

Research into improving the performance and durability of concrete is relevant in construction. It is known that adding polymeric materials to concrete as modifying agents significantly improves the technological characteristics of the concrete mix and enhances its physical and mechanical properties after hardening [1,2,3]. Therefore, the active use of polymers for the production of concrete has led to the formation of new types of composite materials such as polymer concrete, polymer–cement concrete, and polymer-modified concrete. In polymer concrete, fibers are used as reinforcing elements, increasing the plastic strength of concrete [4,5,6]. Composite concretes have found widespread use in the construction industry due to their improved adhesion, workability, high strength, and increased resistance to external influences. However, despite the recognized advantages of these materials, the potential for further modification remains high.

A review of published studies on composite concrete revealed that most of them are focused on ways to increase the compressive, tensile, splitting, and flexural strengths of such concrete. Various types of natural and synthetic polymer materials in varying dosages are proposed as modifying additives. A number of studies describe increased strength in polymer concrete with additional reinforcement using various mineral, synthetic, and metallic fibers. A unifying feature of these studies is that they all focus on studying the strength properties of polymer concrete under static loads.

Thus, article [7] presents the results of studies of concrete samples with different contents of two types of polymers (2.5%, 5%, and 10% of the cement mass)–high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and polypropylene (PP). The experiments revealed positive changes in the strength of such concrete under compression, tension, splitting, and bending. Moreover, with the highest content of polymer additives, equal to 10%, an increase of up to 26% in the compressive strength, up to 20% in the tensile strength, and up to 31% in the bending strength of concrete was observed compared to similar indicators of ordinary cement concrete.

Compressive, flexural, and splitting tensile tests of carbon fiber polymer concrete (CFRPC) prototypes revealed a consistent increase in the strength properties of concrete with a polymer-to-cement ratio of up to 12% [8]. The greatest increase in strength was observed in the splitting strength of the specimens (up to 61%) and their flexural strength (up to 36%), while the increase in compressive strength was insignificant. A polymer-to-cement ratio (by weight) of 8% proved optimal, achieving the best combination of strength and deformation properties of concrete. Increasing the polymer content (to 12% and higher) leads to a decrease in the strength properties of polymer concrete.

The positive effect of adding a polymer (Rheomix 141 styrene–butadiene copolymer) on the physical and mechanical properties of cement concrete was noted in [9]. The experimental results showed that adding 5–10% of the polymer to the cement mass improved the workability of the concrete mix, increased the compressive, splitting, and flexural strength of the concrete, and increased its elastic modulus. The maximum increase in compressive strength of the samples was 33.4%, while the decrease in the water permeability coefficient was 32.4%. The elastic modulus of concrete increased to 11%. These data apply to concrete with a polymer content of 10%.

Partial replacement of cement with Master Emaco SBR2 latex polymer resin (styrene–butadiene copolymer) in quantities of 2.5, 5, 10, and 12.5 L per 50 kg of cement showed changes in the mechanical properties of polymer concrete, including compressive strength, tensile splitting, and flexural strength [10]. Thus, with an increase in the amount of polymer in concrete to 10 L, an increase in its strength properties was observed. However, with an increase in the amount of polymer in concrete above 10 L (up to 12.5 L), the strength of the test samples decreased. Additionally, it was found that the concrete mixture with the addition of the polymer acquires good workability.

The addition of Cement Mix Plus polymers and styrene–butadiene rubber-based latex in amounts of 1%, 3%, and 5% of the cementing agent weight (cement + slag) significantly improved the workability of the concrete mix [11]. Cement was partially replaced by blast-furnace slag in amounts of 50% and 70%. The dry density values of all polymer-containing mixtures exceeded the standard value (2400 kg/m3), with the highest density values observed for mixtures with 70% slag content. After 28 days of sample curing, it was established that, compared to the control compositions, concrete mixes with slag and polymer were characterized by higher compressive strength values. Thus, the strength of the mixture with 50% slag and 5% Cement Mix Plus was 17.67% higher than the strength of the control mixture, and the strength of the mixture with 70% slag and 1% latex was 9.39% higher.

According to many researchers, the mechanical properties of concrete can be improved by using reinforcing materials added to the concrete during its production. Metallic (steel and composite), mineral (basalt and vitreous), and synthetic (polypropylene, nylon, etc.) fibers are commonly used as reinforcing elements. The use of reinforcing elements imparts better adhesion, high crack resistance, and ductility to concrete components.

Thus, it was found that the flexural strength of polymer concrete reinforced with a 3D-printed glass fiber composite is 90% higher than the strength of the same, but non-reinforced, polymer concrete [12]. At the same time, the flexural strength of cement concrete reinforced with the same composite exceeded the strength of non-reinforced cement concrete by only 16.8%.

A significant increase in the mechanical properties of polymer concrete was achieved in compression and flexural testing of polymer concrete specimens reinforced with hook-shaped steel fibers with the addition of polymer latex (SBR) [13]. In the studies, the fiber content in the concrete varied from 1% to 7% by weight of cement (in 1% increments), and the proportion of latex was 15%. After curing the specimens (after 28 days), an increase in their compressive and flexural strength, a decrease in the crack width in them, and a change in the nature of concrete failure were observed. The resistance of beam specimens with a polymer additive exceeded the loads typical of the crack formation phase, even at large deflections.

An increase in the mechanical properties of concrete made using steel fibers and acrylic polymer was observed in experiments using fibers in quantities of 0.5%, 1%, and 1.5% of the concrete volume [14]. The amount of polymer in concrete was taken in quantities of 3%, 7%, and 10% of the cement mass. It was found that the compressive strength of fiber-reinforced concrete increased to 29.2%, and the strength of fiber–polymer concrete to 86.64%. For these concretes, the splitting strength increased to 91% and 124.7%, respectively, and the flexural strength to 48.3% and 78%. It was also found in the experiments that a decrease in the strength of concrete occurred when the amount of polymer in it was more than 7%. The highest strength indicators of concrete in the experiments were obtained when the amount of steel fibers in them was 1% and the amount of polymer was 7%.

The test results presented in [15] indicate the increased strength, high modulus of elasticity, and resistance to sulfate corrosion of hybrid fiber–polymer concrete. Microstructural analysis of concrete samples revealed a denser and more uniform structure of the material with fewer microvoids and cracks compared to conventional concrete. The combination of polymers and reinforcing fibers (steel and polypropylene) resulted in concrete with improved performance characteristics.

The adding of polypropylene fibers into polymer concrete made from styrene–butadiene rubber in the range of 0.1–0.3% of the cement mass revealed its ambiguous behavior under loads [16]. Increases in the compressive and shear strength of polymer concrete were noted in tests, while its shear strength (under dry curing conditions) decreased significantly compared to the strength of conventional concrete. It was also established that increasing the fiber content reduces the workability of the concrete mixture and its density, but at the same time contributes to a decrease in crack width and an increase in the modulus of elasticity at late stages of polymer concrete curing.

As can be seen from the presented brief analysis of scientific papers, the development and study of the properties of high-strength concrete modified with polymers and reinforcing elements are pressing issues. This is dictated by the diversity of the types and properties of these components, as well as the distinctive characteristics of their interaction with cement, water, and concrete aggregates. Undoubtedly, it is also important in this research to establish the optimal content of components used to modify concrete based on the required strength, durability, and reliability characteristics. Thus, analysis of the above research results shows that the optimal amount of added polymer, contributing to increased strength in polymer concrete, ranges from 5 to 12% of the concrete volume [7,8,9,10,11]. Moreover, the greatest increase in strength occurs at 5–10%. Further increases in the amount of polymer materials do not provide a significant increase in concrete strength. In fact, with higher amounts of polymers (over 12%), a decrease in the strength of polymer concrete is observed.

Analysis of the described experiments with reinforcing materials allows us to identify the optimal range of additives that increases concrete strength in the range of 0.5–1.5% of the concrete volume [13,14]. As can be seen, within this range, a significant increase in the mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced polymer concrete is achieved. Although the positive effect of fiber volume fractions up to 7% on concrete is mentioned, no quantitative data is provided, complicating comparison.

Overall, experiments confirm the effectiveness of using polymer resin in the concrete mix to increase its strength, provided that the optimal ratio of the constituent components is maintained.

As can be seen from the analysis of the cited studies, their authors note an increase in the “static” strength of polymer concrete [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16], but the effect of polymers and fibers on the strength of concrete under impact loads is not considered. There are also no experimental data on the effect of humidity on the mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced polymer concrete. However, the operating conditions of polymer concrete suggest its use in natural environments, where humidity is one of the main factors significantly influencing the properties of concrete. Moreover, impact loads occur under certain conditions of polymer concrete application, for example, in the composition of driven reinforced concrete piles with shaft widenings [17,18] and pyramidal-prismatic piles [19,20]. These designs are intended for the construction of foundations for hydraulic structures (chutes, aqueducts, mudflow pipelines, etc.), operated in unfavorable water-soil conditions.

Therefore, conducting experimental research in this area is highly valuable from a scientific perspective and is in demand in construction practice. This suggests that, given the operating conditions of hydraulic structures, assessing the impact of the presence of an aqueous medium on the strength properties of modified concrete is relevant. Despite the importance of this issue, as already noted, no research in this area has been conducted. Nevertheless, there is some evidence that modification of Portland cement with polymers leads to a change in the hydration mechanism [21]. This is due to a decrease in the water–cement ratio, the formation of a three-dimensional polymer network, and a decrease in the porosity of concrete due to the filling of its pores with polymer [14]. Consequently, polymer concrete has a lower density, low water absorption, and high resistance to moisture diffusion [9,21,22]. The reason for this is likely the manifestation of the encapsulating effect of the polymer, which hinders the contact of cement particles with water, and a change in the structure of bonds between water and the components of cement stone in the presence of the polymer.

As noted above, previous studies have shown that polymer- and fiber-modified concrete exhibits significantly improved strength under static loads. Therefore, the hypothesis for this study is that fiber-reinforced polymer concrete exhibits increased tensile strength under static and impact loads, including at elevated humidity levels.

Based on the above arguments, the aim of the present research is to improve the strength properties of Portland cement concrete by adding polymer additives and reinforcing synthetic fibers, as well as to assess the effect of concrete moisture on its static and impact resistance. The scientific novelty of this study lies in the experimental evaluation of the effect of polymer additives and reinforcing materials on the strength of modified concrete in a wet state under static and impact loads.

The research results are intended for use in the manufacture of building elements and structures used in the construction of hydraulic engineering buildings and structures, and other objects in constant contact with aquatic environments.

2. Materials and Methods

The studies were carried out in the A.S. Akhmetov Nanoengineering Research Methods Engineering Research Laboratory of the M.Kh. Dulaty Taraz University using experimental samples with dimensions of 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm, corresponding to the requirements of GOST 10180-2012 [23]. The objects of the study were samples of unreinforced Portland cement concrete, samples of fiber-reinforced concrete with dispersed reinforcement of synthetic fibers, and samples with polymer additives, as well as samples with a combination of fibers and polymer additives. The studies included water saturation of test specimens, static testing of moistened specimens under compressive loads, and repeated impact testing with constant impact energy to determine their strength and assess the effect of moisture on changes in the durability of the modified concretes tested. The type, composition, and procedure for conducting experimental tests of concrete were adopted in accordance with the requirements of interstate standards (GOST), unified for use in the construction industry of the CIS countries.

2.1. Characteristics of Source Materials

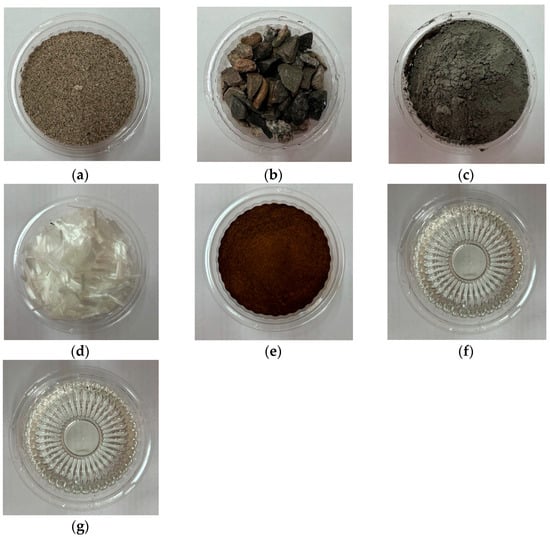

To produce concrete samples, granite sand, which complies with the requirements of GOST 8736–2014 [24], was used as fine aggregate, and crushed granite with a grain size of 5 mm–20 mm, which complies with GOST 8267–93 [25], was used as coarse aggregate. Portland cement grade M400, which complies with the requirements of GOST 30515-2013 [26], was used as a binder for concrete. Three types of material were used as polymer modifiers: MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 superplasticizer and PN-609-21M resin (in liquid form), and Polyplast SP-1 plasticizer (in dry powder form). FIBERQAZAQSTAN polypropylene fibers served as reinforcing materials. The choice and use of these materials were determined by their availability, relative affordability, and comparatively superior properties (high chemical inertness, resistance to the alkaline environment of cement stone, low density, and the ability to be uniformly distributed within the concrete matrix). The need to evaluate the effect of liquid and dry polymers on the studied parameters of polymer concrete was also taken into account. The main physical and mechanical properties of the materials adopted for the manufacture of test samples are presented in Table 1. The general appearance of the source materials is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Physical and mechanical properties of materials.

Figure 1.

Initial components of concrete: (а) Sand; (b) Crushed stone; (c) Cement; (d) FIBERQAZAQSTAN polypropylene fiber; (e) Polyplast SP-1; (f) MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 concrete superplasticizer; (g) PN-609-21M resin (unsaturated polyester).

2.2. Composition and Consumption of Concrete Components

Testing of the experimental specimens was conducted in two stages, each consisting of seven series of experiments, repeated three times to ensure statistical reliability of the results. For each series of experiments, a separate batch of specimens was prepared from the same concrete mix. A total of 168 specimens were tested in the study; information on the specimens is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Information on samples prepared for testing.

The volume fractions of polypropylene fibers (1%) and polymer concentrations (3.5% MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 and 7% Polyplast SP-1) were selected based on the recommendations of their manufacturers and the results of the analysis presented in the introduction of this article. In addition, the results of the authors’ own previous research, described in detail in [4], were also taken into account.

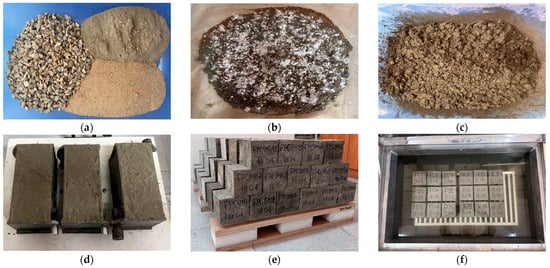

Fragments of concrete components, the fiber-reinforced concrete mixture, and the samples in molds are shown in Figure 2. Fiber-reinforced concrete and concrete samples were tested using laboratory equipment after 28 days of air-drying under natural conditions.

Figure 2.

(a) Constituent components of concrete; (b) mixture with fiber additives; (c) fiber-reinforced concrete mixture; (d) specimens in molds; (e) finished concrete specimens; (f) concrete specimens immersed in water.

2.3. Equipment for Testing Samples

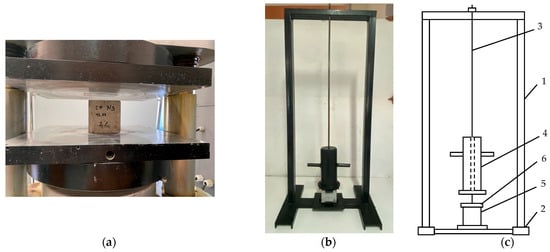

Static tests of vertical compression samples were carried out using a P-125 hydraulic press (Armavir, Moscow, Russia) with a maximum load capacity of up to 1250 kN (Figure 3a). This equipment enables uniaxial loading of test specimens with high accuracy and controlled load increments, ensuring a reliable assessment of the test characteristics.

Figure 3.

Equipment for testing samples: (a) hydraulic press P-125 for compression; (b) laboratory facility for impact testing; (c) schematic diagram of the impact facility.

To test prototypes under repeated dynamic (impact) loads, a special laboratory mechanical impact-type facility was developed and constructed (Figure 3b). The main functional elements of this facility (Figure 3c) are listed below.

The U-shaped supporting frame (1) is made from sections of hollow square metal tubing measuring 60 mm × 30 mm, welded together. The frame provides spatial rigidity to the entire system and serves as the base for securing all other components.

The support structure (2) consists of two longitudinal beams and one cross beam, made of a channel with a 100 mm web width and a 40 mm shelf height. Frame uprights are welded to the longitudinal beams, and a 200 mm × 200 mm, 10 mm thick platform is attached to the cross beam. A 5 mm high locking pin is installed in the center of the platform, designed to position the removable lower support plate. The latter is equipped with a central hole and symmetrical protrusions, ensuring rigid fixation of the lower part of the specimen during testing.

A guide rod (3), made of smooth reinforcement with a diameter of 10 mm, is designed to stabilize the impactor’s trajectory. Its upper end is secured to the frame’s crossbar with a bolt, and its lower end is inserted into a hole in the upper removable support plate (10 mm thick), which is placed on the upper surface of the specimen. The plate is also equipped with locking tabs to hold the specimen in place. To protect the contact zone and reduce localized stresses, a damping element made of 3 mm thick plywood is additionally installed between the upper plate and the specimen.

The hammer (4) is a steel tube, 300 mm high and 160 mm in outer diameter, weighing 15 kg. A through hole with a diameter of 12 mm is made in the central axis of the striker, allowing it to move freely along the guide rod. It is lifted manually using two symmetrically located handles on the outer side surface. The striker is dropped from a fixed height of 1.0 m, providing a repetitive pulse load on the test specimen (5) clamped between the support plates (6).

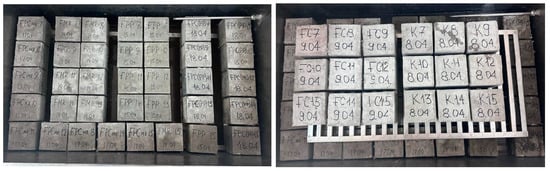

A KUP-1 steam chamber filled with water was used to saturate the test specimens (Figure 4). The specimens were saturated for 20, 40, and 60 days to determine the effect of moisture on their strength.

Figure 4.

Placing concrete samples in a steam chamber for water saturation.

The moisture content of the concrete specimens was determined using the following formula:

where is the mass of the water-saturated sample, g; is the mass of the sample in an air-dried state, g.

2.4. Testing Methods and Indicators for Comparative Evaluation of Results

Static tests of samples were carried out in accordance with the requirements of GOST 10180-2012 [23], which regulate methods for determining the strength of concrete under compression, tension, and bending.

Dynamic (impact) tests of the samples were carried out with the recording of the total number of impacts on them until their complete destruction, as well as the number of impacts corresponding to the moment of the appearance of the first visible defects on their surface and their active development, including microcracks, delamination, chips, and other forms of local deformations.

A three-stage failure model was used for impact testing. This model included

- -

- Damage initiation stage—the moment at which defects begin to form, characterizing the material’s resistance to initial loads;

- -

- Progressive failure stage—the interval from the appearance of the first defects to the active development of structural damage to the specimen;

- -

- Complete failure stage—the interval from the active progression of defects to the complete structural failure of the specimen.

Each stage was accompanied by visual and instrumental recording of defects, including photographic documentation, description of the nature of the damage, and, if necessary, the use of magnifying equipment or digital image analysis to precisely map the damaged area.

This comprehensive approach allowed for a reliable assessment of the impact strength of the test samples.

For a quantitative comparative evaluation of the research results, the following criteria for their relative effectiveness were adopted.

- For static tests.

For samples 1–3 and 7–15 in all 7 batches (Table 2), the relative concrete strength coefficient was adopted:

where —destructive load for the test sample, kN; —destructive load for the control sample, kN; n—type of sample.

- 2.

- During impact testing.

For samples 4–6 and 16–24 in all 7 batches (Table 2), relative energy efficiency indices were adopted, corresponding to three stages of sample damage under impact.

The relative energy capacity coefficient at the stage of first defect appearance is as follows:

where —impact energy for the test sample, kJ; —impact energy for the control sample, kJ; n—sample type.

The relative energy intensity coefficient at the stage of progressive destruction is as follows:

where is the total impact energy for the test sample, kJ; is the total impact energy for the control sample, kJ; n is the type of sample.

The relative energy intensity coefficient at the stage of complete destruction is as follows:

where is the total impact energy for the test sample, kJ; is the total impact energy for the control sample, kJ; n is the sample type.

Coefficients , , and enable the implementation of an energy-based approach to assessing the impact resistance of the test samples.

- 3.

- When samples are saturated with water.

For samples 7–24 in all 7 batches (Table 2), the relative water capacity coefficient is defined as

where is the average moisture content of the test sample, %; is the average moisture content of the control sample, %; n is the sample type.

The coefficient values are established for samples with water saturation periods of 20, 40, and 60 days.

- 4.

- Specimen Deformation Criteria.

The following failure criteria were adopted for three-stage specimen failure during impact testing:

- -

- At the initial defect formation stage: the appearance of hairline cracks with an opening width of up to 0.1 mm and a length of no more than 20 mm; localized chipping in the corners and ends of the specimen, covering a total area of up to 10%.

- -

- At the progressive failure stage: the formation of developed inclined and/or vertical cracks with a width of 2 to 5 mm; chipping covering up to 30% of the surface; fiber exposure, localized structural destruction.

- -

- At the complete failure stage: massive chipping covering up to 60% of the surface; fiber exposure, complete structural destruction, loss of integrity and dimensional stability.

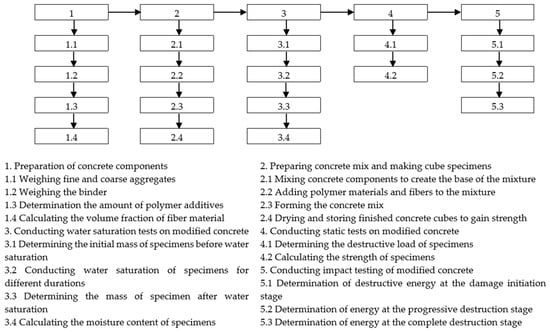

The experimental procedures and research flow are presented in the form of a simplified flow chart in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Description of procedures and order in which research was conducted.

3. Results and Discussion

Tests to determine the degree of water saturation of concrete samples were carried out in accordance with the requirements of GOST 12730.2-2020 [27]. The results of determining the moisture content of the samples based on Formula (1) are presented in Table 3. It follows that the average moisture content of concrete samples increases with the duration of their water saturation. Thus, with 20 days of water saturation, the average moisture content of the samples was 4.17–7.39%, with 40 days 4.57–7.56%, and with 60 days 4.80–7.75%.

Table 3.

Information on the moisture content of concrete samples.

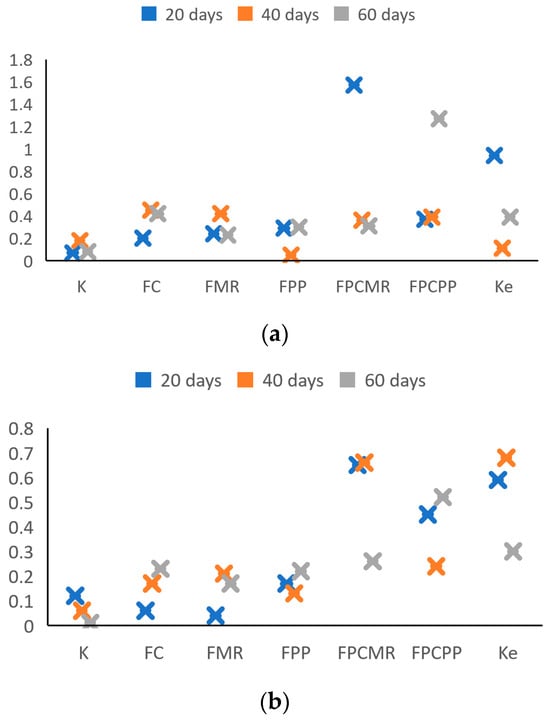

To confirm the reliability of the obtained average values, standard deviations of the average moisture content of the samples were calculated for different periods of water saturation. The calculation results, obtained separately for the samples used in static and impact tests, are presented in Figure 6. As can be seen from the graph, the standard deviations of the data at their maximum do not exceed 1.57%.

Figure 6.

Standard deviations of the average moisture content of samples for different periods of water saturation: (a) for static tests; (b) for impact tests.

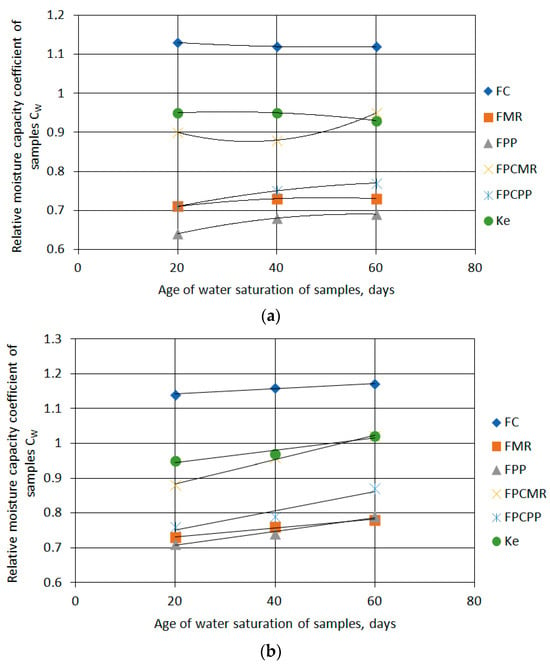

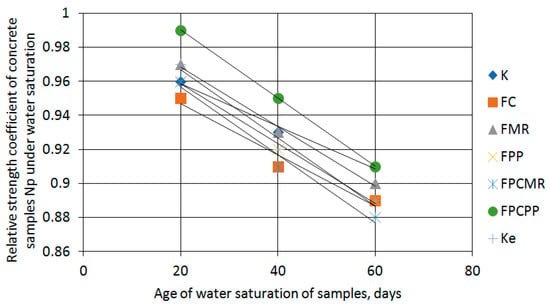

The relative water capacity coefficients (CW) determined for the samples using Formula (6) are presented in Table 4. Graphs of the dependence of this coefficient on the duration of saturation are shown in Figure 7.

Table 4.

Values of the relative moisture capacity coefficient of concrete samples.

Figure 7.

Dependence of the relative moisture capacity coefficient of samples on the duration of water saturation: (a) for static tests; (b) for impact effects.

The graphs shown in Figure 7a are described by a second-order polynomial function

where h, q, and w—parameters taken from Table 5; t—duration of concrete water saturation, days.

Table 5.

Values of parameters h, q, and w in Formula (7).

The graphs shown in Figure 7b is described by a linear function

where u and z—parameters taken from Table 6; t—duration of concrete water saturation, days.

Table 6.

Values of parameters u and z in Formula (8).

From the data in Table 5 and Table 6, it is evident that the obtained correlation dependencies, described by linear and polynomial functions, are characterized by high values of reliability of data approximation.

The results of the studies revealed the following characteristics of moisture content changes in samples saturated with water for 20 to 60 days:

- -

- Compared to control concrete samples, the moisture content of polymer concrete is 5–36% lower;

- -

- The lowest average moisture content values are observed for polymer–cement concrete samples with the additive Polyplast SP-1 (FPP), which are 31–36% lower than for control samples (K);

- -

- The highest average moisture content is typical for polypropylene fiber-reinforced concrete (FC) samples, with values 1.09–1.13 times higher than those of the control samples (K);

- -

- Relatively low moisture content is typical for polymer–cement concrete with MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 additive (FMR) and polymer–cement fiber-reinforced concrete with Polyplast SP-1 additive (FPCPP), with average values 27–29% and 23–29% lower, respectively, than those of the control samples;

- -

- The average moisture content of polymer–cement fiber-reinforced concrete samples with the addition of MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 (FPCMR) and polymer concrete treated with polyester resin PN-609-21M (Ke) is 5–10% and 5–7% lower, respectively, than that of the control samples.

The presented analysis shows that the average moisture content of concrete samples produced with the addition of MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 and Polyplast SP-1 superplasticizers is significantly lower than that of other types of concrete. These data suggest that the use of polymer additives in concrete production leads to a decrease in its water absorption properties, which is consistent with the results of [9]. In our opinion, this is due to the specific intermolecular interactions of polymer substances with concrete aggregate particles, which lead to structural changes that reduce moisture diffusion into the polymer material. The increase in the moisture capacity of polypropylene fiber-reinforced concrete is likely due to the adsorption processes of polypropylene fibers, leading to increased moisture absorption and its structural binding within the concrete.

The results of concrete specimen static load tests are presented in Table 7. Figure 8 shows fragments of the specimen tests. The standard deviation of the average static strength data for specimens at different water saturation periods is presented in Figure 9. As can be seen from the graph, the maximum standard deviation of the data does not exceed 0.77 MPa, confirming the reliability of the average values obtained.

Table 7.

Test results of concrete samples under static loads.

Figure 8.

Fragments of sample tests.

Figure 9.

Standard deviation of the average static strength data of samples at different periods of water saturation (from Table 7).

The results of determining the values of the relative strength coefficient of concrete using Formula (2) are presented in Table 8 and Figure 10.

Table 8.

Values of the relative strength coefficient of samples.

Figure 10.

Dependence of the relative strength coefficient of samples on the duration of water saturation.

The graphs shown in Figure 10 are described by the following linear function:

where a and y are the parameters taken from Table 9 depending on the type of concrete; t is the duration of water saturation of concrete, days.

Table 9.

Values of parameters a and y in Formula (9).

As can be seen from the data in Table 9, the correlation dependence according to the linear function has a fairly high reliability of data approximation.

An analysis of the static test results for the samples allows us to draw the following key conclusions:

- -

- The ultimate strength of concrete samples made with polymer additives is 1.03–1.53 times higher than that of control samples (without additives).

- -

- The greatest strength increases of 1.53 and 1.48 times are characteristic of polymer–cement fiber-reinforced concrete samples with MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 (FPCMR) and Polyplast SP-1 (FPCPP) additives, respectively.

- -

- The lowest excess strength of 1.03 and 1.05 times is typical for concrete-polymer samples treated with polyester resin PN-609-21M (Ke) and polypropylene fiber-reinforced concrete (FC) samples, respectively.

- -

- Intermediate positions in excess strength of 1.35 and 1.33 times are typical for polymer–cement concrete with additives MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 (FMR) and Polyplast SP-1 (FPP), respectively.

- -

- With an increase in water saturation time from 20 to 60 days, a decrease in the ultimate strength of samples by 1.03–1.14 times is observed.

- -

- Compared to the control samples (K), the maximum excess strength was established for samples of polymer–cement fiber-reinforced concrete with additives Polyplast SP-1 (FPCPP) and MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 (FPCMR) with the duration of water saturation: in 20 days, by 1.53 and 1.52 times, respectively; in 40 days, by 1.51 and 1.49 times, respectively; in 60 days, by 1.48 times for both samples.

- -

- Compared to the control samples (K), the minimum increase in strength was found for samples of polypropylene fiber-reinforced concrete (FC) and concrete-polymer samples treated with polyester resin PN-609-21M (Ke), with the duration of their water saturation: in 20 days, by 1.04 and 1.03 times, respectively; in 40 days, by 1.03 and 1.02 times, respectively; in 60 days, by 1.03 times (only for samples made of polypropylene fiber-reinforced concrete).

These data show that adding polypropylene fibers to concrete mixtures increases the strength of concrete, while their combination with modifying polymers increases its strength by approximately 50% compared to the strength of concrete without additives. Furthermore, as can be seen, increasing the water saturation time of polymer concretes leads to a decrease in their static strength.

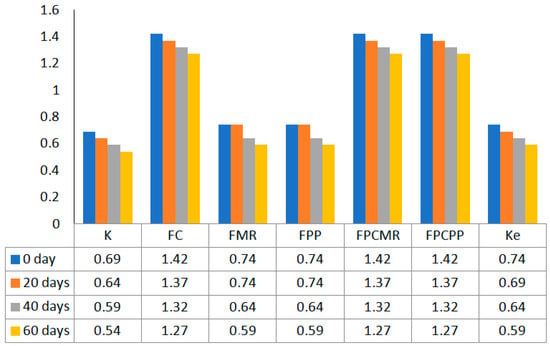

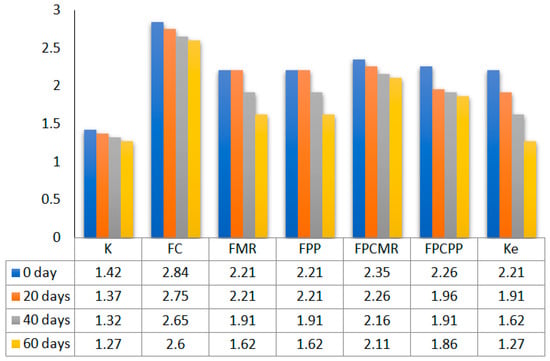

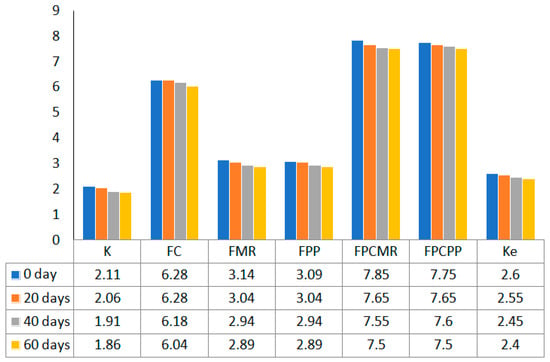

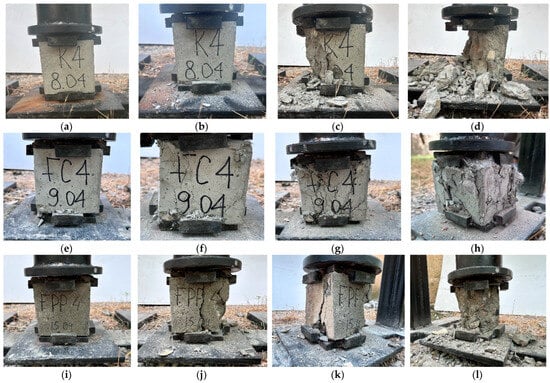

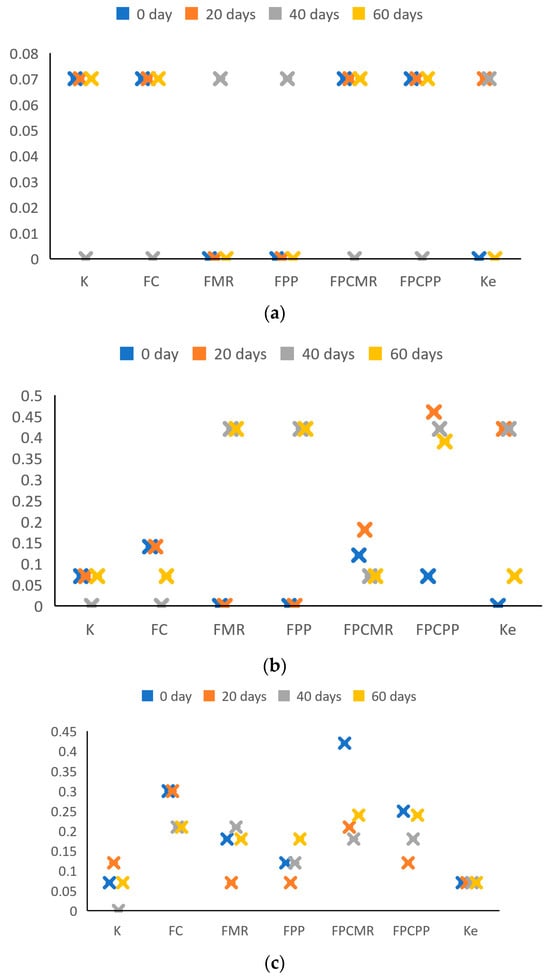

The results of concrete specimen impact tests are presented in Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13. Standard deviations of the average impact strength data for specimens with different water saturation periods, calculated at each stage of failure (damage initiation, progressive failure, and complete failure), are shown in Figure 14. Their maximum values are no higher than 0.45 kJ, demonstrating the reliability of the average energy consumption for failure. Excerpts from the tests and specimen failures are shown in Figure 15.

Figure 11.

Average total energy for initiation of damage to the sample, kJ.

Figure 12.

Average total energy of progressive destruction of the sample, kJ.

Figure 13.

Average total energy of complete destruction of the sample, kJ.

Figure 14.

Fragments of tests and destruction of concrete specimens under impact loads: (a,e,i) initial state; (b,f,j) damage initiation stage; (c,g,k) progressive destruction stage; (d,h,l) complete destruction stage.

Figure 15.

Standard deviations of the average impact strength data of specimens at different periods of water saturation: (a) damage initiation stage; (b) progressive destruction stage; (c) complete destruction stage.

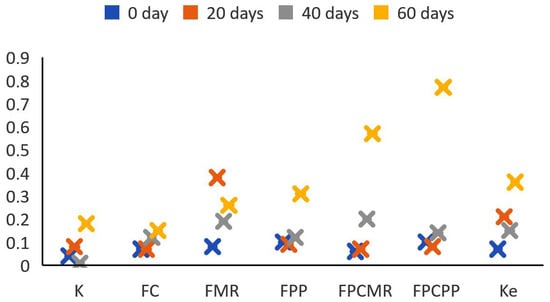

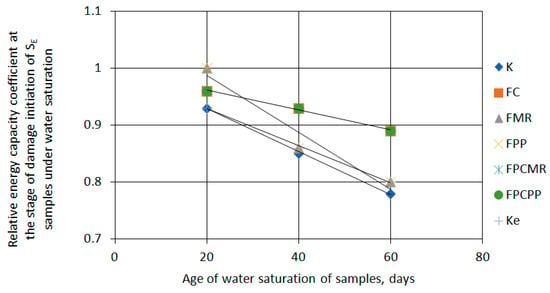

The results of determining the values of the relative energy intensity coefficient at the stage of damage initiation of concrete samples according to Formula (3) are presented in Table 10 and Figure 16.

Table 10.

Values of the relative energy intensity coefficient at the stage of damage initiation of concrete samples .

Figure 16.

Dependence of the coefficient of relative energy intensity at the stage of damage initiation of concrete samples on the duration of water saturation.

The graphs shown in Figure 16 are described by the following linear function:

where k and o are the parameters taken from Table 11 and depend on the type of concrete; t is the duration of water saturation of concrete, days.

Table 11.

Values of parameters k and o in Formula (10).

The analysis of the test results at the stage of damage initiation of concrete samples, presented in Figure 11 and Table 10, allows us to draw the following conclusions:

- -

- The resistance to destruction under impact loads of polymer concrete is, on average, 1.07–2.35 times higher than that of the control concrete.

- -

- The impact resistance of polymer concrete treated with polyester resin PN-609-21M (Ke), as well as polymer–cement concrete with additives Polyplast SP-1 (FPP) and MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 (FMR), is 1.07–1.09 times higher compared to control concrete (K).

- -

- Polymer–cement fiber-reinforced concretes with additives MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 (FPCMR) and Polyplast SP-1 (FPCPP), as well as polypropylene fiber-reinforced concretes (FC), are characterized by a 2.06–2.35 times higher impact resistance compared to control concrete samples (K).

- -

- With an increase in the water saturation period of the samples to 20, 40, and 60 days, a decrease in the impact resistance of the samples by 4–7%, 7–15%, and 11–22%, respectively, is observed.

- -

- With a water saturation period of 20, 40, and 60 days, the impact strength decreased: for samples FC, FPCMR, and FPCPP, by 4, 7, and 11%, respectively; for Ke samples, by 7, 14, and 20%; and for samples FMR and FPP, a decrease in the desired characteristic of 14 and 20% was observed at 40 and 60 days of water saturation of the samples.

The results of determining the values of the relative energy intensity coefficient at the stage of progressive destruction of concrete samples according to Formula (4) are presented in Table 12 and Figure 17.

Table 12.

Values of the relative energy intensity coefficient at the stage of progressive destruction of concrete samples .

Figure 17.

Dependence of the coefficient of relative energy intensity of complete destruction of concrete samples on the duration of water saturation.

The graphs shown in Figure 17 are described by the following linear function:

where d and n are the parameters taken from Table 13 and depend on the type of concrete; t is the duration of water saturation of concrete, in days.

Table 13.

Values of parameters d and n in Formula (11).

An analysis of the test results at the stage of progressive destruction of concrete samples, presented in Figure 12 and Table 12, allows us to draw the following conclusions:

- -

- Polymer concretes are, on average, 1.28–2.05 times more resistant to impact loads than control concretes.

- -

- Polymer concrete treated with polyester resin PN-609-21M (Ke) and polymer–cement concrete with additives Polyplast SP-1 (FPP) and MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 (FMR) are 1.28–1.56 times more impact-resistant than control concrete (K).

- -

- The impact resistance of polymer–cement fiber-reinforced concrete with Polyplast SP-1 (FPCPP) additive is 1.46–1.59 times higher, and that of polymer–cement fiber-reinforced concrete with MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 (FPCMR) additive is 1.65–1.66 times higher than that of control concrete (K).

- -

- Polypropylene fiber-reinforced concrete (FC) proved to be the most impact-resistant, with impact resistance 2.0–2.05 times higher than that of control concrete (K).

- -

- As the water saturation period of the samples increased to 20, 40, and up to 60 days, the impact resistance limit of the samples decreased by 3–14%, 7–17%, and 9–43%, respectively.

- -

- At water saturation periods of 20, 40 and 60 days, the ultimate impact strength decreased: for FC samples, by 3, 7, and 9%, respectively; for FPCMR samples, by 4, 8, and 10%; for FPCPP samples, by 13, 16, and 18%; for Ke samples, by 14, 27, and 43%. Finally, for FMR and FPP samples, a decrease of 14 and 27% was found at 40 and 60 days of water saturation.

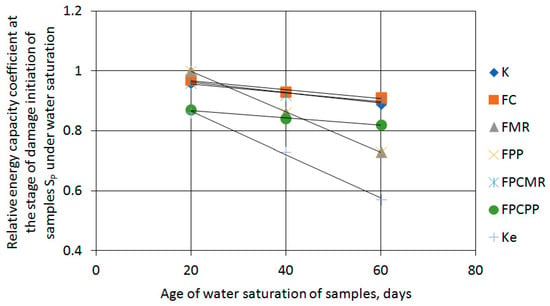

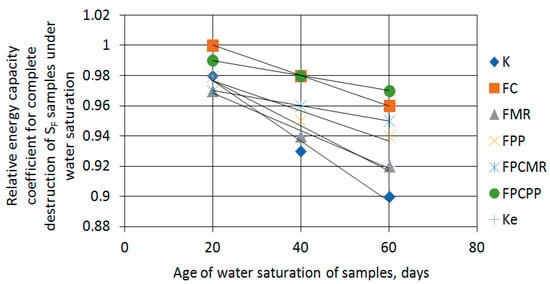

The results of determining the values of the relative energy intensity coefficient of complete destruction of concrete samples SF using Formula (5) are presented in Table 14 and Figure 18.

Table 14.

Values of the coefficient of relative energy intensity of complete destruction of concrete samples .

Figure 18.

Dependence of the coefficient of relative energy intensity of complete destruction of concrete samples on the duration of water saturation.

The graphs shown in Figure 18 are described by the following linear function:

where m and r are the parameters taken from Table 15 and depend on the type of concrete; t is the duration of water saturation of concrete, days.

Table 15.

Values of parameters m and r in Formula (12).

The data in Table 11, Table 13 and Table 15 show a fairly high degree of reliability of the approximation of the correlation data obtained by the linear function.

Analysis of the test results at the stage of complete destruction, presented in Figure 13 and Table 14, allows us to draw the following conclusions:

- -

- The impact resistance of polymer concretes is, on average, 1.23–4.03 times higher than that of the control concretes.

- -

- The lowest impact resistance is observed in polymer concretes treated with PN-609-21M polyester resin (Ke), which is 1.23–1.29 times higher than that of the control concretes (K).

- -

- Compared to control concretes (K), the impact resistance of polymer–cement concretes with Polyplast SP-1 (FPP) and MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 (FMR) additives is 1.49–1.55 times higher.

- -

- Polypropylene fiber-reinforced concretes (FC), compared to control concrete samples (K), are characterized by a 2.98–3.25 times higher resistance to impact loads.

- -

- The highest impact resistance indicators, exceeding by 3.72–4.03 times similar parameters of control concretes (K), were established for polymer–cement fiber-reinforced concretes with additives MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 (FPCMR) and Polyplast SP-1 (FPCPP).

- -

- With an increase in the period of water saturation of the samples to 20, 40, and up to 60 days, the resistance of the samples to impact loads decreased by 1–3%, 2–7%, and 3–10%, respectively.

- -

- At water saturation periods of 20, 40, and 60 days, the impact strength limit decreased: for FC samples, by 2 and 4% (at 40 and 60 days); for FPCPP samples, by 1, 2, and 3%, respectively; for FPP samples, by 2, 5, and 6%; for Ke samples, by 2, 6, and 8%; for FPCMR samples, by 3, 4, and 5%; for FMR samples, by 3, 6, and 8%.

An analysis of defect formation and development in the specimens with increasing number (energy intensity) of impacts revealed that the deformation process of polymer concrete specimens proceeds more slowly than that of the control specimens. Thus, the onset of the damage initiation stage (the appearance of thin hairline cracks up to 2 cm long; chips in the upper and lower corners) of the polymer concrete specimens was recorded at a total impact energy within the range of 1.47–2.21 kJ, whereas for the control specimens similar deformations developed at an impact energy expenditure of 0.74–1.03 kJ. The stage of progressive failure (the development of vertical and inclined cracks up to 5 mm wide and 2–3.5 cm deep, as well as the loss of concrete fragments amounting to no more than 30% of the total volume of this section) of the polymer concrete specimens occurred at a total impact energy of 2.22–2.94 kJ. This corresponded to the stage of complete destruction of the control samples.

Furthermore, it was established that the failure of control specimens (K) occurs in the form of spalling and loss of individual concrete fragments, whereas the failure of polymer–cement concrete specimens (FC, FMR, and FPP) has a somewhat different nature. The failure characteristics of these concrete specimens include vertical compression of deformed specimen fragments, weakening of the adhesion between aggregate grains and cement stone, and loosening of the concrete structure, accompanied by a loss of their monolithicity. In addition to these characteristics, complete failure of polymer–cement fiber-reinforced concrete (FPCMR and FPCPP) also results in the preservation of bonds between individual concrete fragments due to the adhesive effect and reinforcing action of the fibers, in contrast to the complete spalling and loss of concrete in the control specimens. The use of a polymer coating applied to the surface of the specimens in the case of polymer concrete (Ke) does not significantly improve the impact resistance of the concrete.

Relatively long-term and constant exposure of polymer–cement concrete to moisture adversely affects its strength parameters, reducing them by 20–27%. This may be due to decreased adhesion and increased mobility of binder particles due to the plasticizing effect of moisture. Water diffusion into the polymer matrix likely accelerates the weakening of the interfacial bond between the polymer matrix and mineral filler, leading to the development of microcracks at the interface. The increase in concrete volume due to swelling also contributes to the development of internal stresses. Moisture disrupts the equilibrium between the cement and polymer phases, causing swelling and weakening adhesion. The combined effect of these factors explains the gradual decline in the strength parameters of polymer-modified concrete. However, the obtained values are, on average, only 5% lower than the similar decrease (up to 15–22%) in the strength of control concrete when saturated with water. This slight decrease in the strength of polymer–cement concrete is offset by an overall increase in its ultimate strength under operational loads.

4. Conclusions

Based on the results of our experimental studies, the following key conclusions can be drawn:

(1) A quantitative assessment of the effect of moisture on the static and impact strength of Portland cement concrete modified with polymer additives and synthetic fiber reinforcement was performed. It was found that modifying concrete with polymer additives in combination with fiber reinforcement increases its strength (by 1.03–1.53 times).

(2) The introduction of polymeric materials promotes the formation of a dense and homogeneous structure of cement stone, reducing its capillary porosity and water absorption by 5–36%. Additional fiber reinforcement prevents the formation and development of microcracks, ensuring their strength in conditions of high humidity.

(3) Water saturation of polymer–cement fiber-reinforced concrete reduces its strength limits (by 1.03–1.14 times) under static compressive loads. Nevertheless, even in a water-saturated state, the strength of polymer-modified concrete is comparable to or significantly higher than the strength of conventional concrete.

(4) The use of polymer additives in combination with fiber reinforcement increases the impact strength of concrete (by 1.07–3.72 times) due to the redistribution of the impact load, the absorption of impact energy, and an increase in fracture toughness.

(5) Long-term exposure to moisture on polymer–cement fiber concrete reduces its impact strength by 20–27%, which is a consequence of reduced adhesion at the boundary between the concrete matrix and the fiber due to the influence of moisture and reduced friction between grains and fibers.

(6) The results obtained can be used in the development of compositions of moisture-resistant concretes for special purposes, used in hydraulic engineering and operated in conditions of high humidity and water saturation.

Despite the obtained results, questions regarding the study of the microstructure, chemical resistance, abrasion resistance, dosage optimization, and other parameters of polymer-modified concretes subject to increased and constant water saturation remain open and require further research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.A. and I.B.; methodology, Y.A. and I.B.; software, Y.A. and N.S.; validation, Y.A., I.B. and N.S.; formal analysis, Y.A.; investigation, Y.A., I.B. and N.S.; resources, Y.A. and N.S.; data curation, Y.A. and N.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.A. and N.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.A. and I.B.; visualization, Y.A. and N.S.; supervision, I.B.; project administration, I.B.; funding acquisition, Y.A., I.B. and N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and High Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan, grant number BR24992867.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Orynbaev S. and Baizhumanov M. for their support in conducting experimental studies and preparing publication materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HDPE | High-density polyethylene |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| CFRPC | Carbon fiber polymer concrete |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| SBR | Polymer latex |

| GGBS | Granulated blast-furnace slag |

| PC | Polymer concrete |

| PCC | Portland cement concrete |

| GOST | State standard |

| KUP-1 | Universal steam chamber |

| K | Control concrete |

| FC | Polypropylene fiber concrete |

| FMR | Polymer–cement concrete with MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 additive |

| FPP | Polymer–cement concrete with the additive Polyplast SP-1 |

| FPCMR | Polymer–cement fiber-reinforced concrete with MasterRHEOBUILD 1033 additive |

| FPCPP | Polymer–cement fiber concrete with the additive Polyplast SP-1 |

| Ke | Concrete polymer treated with polyester resin PN-609-21M |

References

- Czarnecki, L. Polymer-Concrete Composites for the repair of concrete structures. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 199, 01006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, B. Effects of Polymers on Cement Hydration and Properties of Concrete: A Review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 2014–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engert, M.; Frankenbach, K.; Werkle, K.T.; Möhring, H.-C. Simulation of the flexural behavior of prestressed fiber-reinforced polymer concrete. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 138, 2591–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isabai, B.; Nurzhan, S.; Yerlan, A. Strength Properties of Various Types of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete for Production of Driven Piles. Buildings 2023, 13, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabdushev, A.; Delikesheva, D.; Korgasbekov, D.; Manapbayev, B.; Kalmakhanova, M. Identifying the influence of basalt fiber reinforcement on the deformation and strength characteristics of cement stone. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2023, 5, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekbasarov, I.; Shanshabayev, N.; Atenov, Y. Impact-Driven Penetration of Multi-Strength Fiber Concrete Pyramid-Prismatic Piles. Buildings 2024, 14, 3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumaran, S.; Muralimohan, N.; Sudha, P. An Investigation on Strength and Durability Properties of Polymer Modified Cement Concrete. Int. J. Adv. Res. Basic Eng. Sci. Technol. (IJARBEST) 2017, 3, 12. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343650850_An_investigation_on_strength_and_durability_properties_of_polymer_modified_cement_concrete’ (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Liu, G.-J.; Bai, E.-L.; Xu, J.-Y.; Yang, N. Mechanical Properties of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Concrete with Different Polymer-Cement Ratios. Materials 2019, 12, 3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhikshma, V.; Jagannadha Rao, K.; Balajia, B. An Experimental Study on Behavior of Polymer Cement Concrete. Asian J. Civ. Eng. (Build. Hous.) 2010, 11, 563–573. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259934037_An_experimental_study_on_behavior_of_polymer_cement_concrete (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Babur, D.V.; Mukesh, P.; Pandey, M.; Harikaran, M.; Balaji, G.; Monisha, K.M. Experimental study of concrete by replacement of cement with polymer resin. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1125, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naga Rajesh, K.; Markandaya Raju, P.; Mishra, K.; Rao, P.S. Performance of cement mix plus and styrene butadiene rubber polymers in slag-based concrete. Int. J. Mech. Prod. Eng. Res. Dev. (IJMPERD) 2020, 10, 1527–1538. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342643421_Performance_of_cement_mix_plus_and_styrene_butadiene_rubber_polymers_in_slag_based_concrete (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Haibe, A.A.; Vemuganti, S. Flexural Response Comparison of Nylon-Based 3D-Printed Glass Fiber Composites and Epoxy-Based Conventional Glass Fiber Composites in Cementitious and Polymer Concretes. Polymers 2025, 17, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalwane, U.B.; Dahake, A.G. Effect of Polymer Modified Fibers on Strength of Concrete. J. Polym. Compos. 2015, 3, 15–24. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281774771_Effect_of_Polymer_Modified_Fibers_on_Strength_of_Concrete (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Al-Hadithi, A.I.; Jameel, G.S. Mechanical Properties of Fiber Concrete Containing Acrylic Polymer. Iraqi J. Mech. Mater. Eng. 2010, 46–61. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249011234_Mechanical_Properties_of_Fiber_Concrete_Containing_Acrylic_Polyme (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Zhao, C.; Yi, Z.; Wu, W.; Zhu, Z.; Peng, Y.; Liu, J. Experimental Study on the Mechanical Properties and Durability of High-Content Hybrid Fiber–Polymer Concrete. Materials 2021, 14, 6234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuwaraj, M. Ghugal. Performance of polymer modified polypropylene fiber reinforced concrete with low fiber volume fractions. Indian Concr. J. 2016, 90, 1–9. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297386698_Performance_of_polymer_modified_polypropylene_fiber_reinforced_concrete_with_low_fiber_volume_fractions (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Isabai, B.; Yerlan, A.; Nurzhan, S. The Influence of Backfill on the Driving Energy Intensity and Axial Load Resistance of Piles with Shaft Widenings: Modeling Research. Buildings 2023, 13, 3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atenov, Y.; Bekbasarov, I.; Shanshabayev, N. Energy Intensity and Uplift Load Resistance of Novel Hybrid Pile, Driven with Additional Compaction: Comparative Field Study. Buildings 2025, 15, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekbasaov, I.; Shanshabayev, N. Impact Dipping Pyramidal-Prismatic Piles and their Resistance to Pressure and Horizontal Load. Period. Polytech. Civ. Eng. 2021, 65, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekbasarov, I.; Shanshabayev, N. Driving Features of Tapered-Prismatic Piles and Their Resistance to Static Loads. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2022, 4, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocco, J.A.F.F.; Gonçalves, R.F.B.; Domingues, M.G. Physicochemical Behavior of Concretes Admixed with Water-Based Polymers (PMC: Polymer-Modified Concrete). In Reinforced Concrete Structure—Innovations in Materials, Design and Analysis; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, M.T.; Hameed, A.M. Manufacturing Polymer Concrete by Using Reused Aggregates. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Technology, Singapore, 2019; 126p. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350214000_Manufacturing_Polymer_Concrete_by_Using_Reused_Aggregates (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- GOST 10180-2012; Concrete. Methods for Determining Strength Using Control Samples. Federal State Statistics Service: Moscow, Russia, 2018; 36p.

- GOST 8736-2014; Sand for Construction Work. Technical Conditions. Federal State Statistics Service: Moscow, Russia, 2019; 11p.

- GOST 8267-93; Crushed Stone and Gravel from Dense Rocks for Construction Work. Federal State Statistics Service: Moscow, Russia, 2018; 14p.

- GOST 30515-2013; Cements. General Specifications. Federal State Statistics Service: Moscow, Russia, 2019; 42p.

- GOST 12730.2-2020; Concrete. Method for Determining Moisture Content. Federal State Statistics Service: Moscow, Russia, 2021; 15p.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).