Abstract

This study investigates the use of digital twin technology, machine learning (ML), and artificial intelligence (AI) to improve energy efficiency. It focuses on the heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems in hotel buildings which rely on central air-conditioning 24/7 throughout the year for ensuring thermal comfort and air ventilation. We develop a three-phase digital twin framework illustrating the progression from monitoring to autonomous control. Using data from real-world deployment in a Hong Kong hotel since 2013, we evaluated the evolution of digital twin applications from the Fixed Mode, to the Energy Optimisation Solution (EOS) Mode, finally to an AI-driven autonomous system. Leveraging 17,520 hourly data points from 1416 Internet of Things sensors, we relate digital twin features to environmental benefits based on energy consumption and Energy Efficiency Ratio (EER). For energy consumption, the AI Mode achieves the lowest daily energy consumption, averaging 841.94 kWh, which was 21.91% lower than Fixed mode and 50.42% lower than EOS mode. Under real-world conditions, the AI-driven autonomous digital twin improved EER by 6.2% over EOS and 2.9% over the Fixed Mode, confirming its superior thermal efficiency. The results demonstrate the benefits of combining digital twins with AI to enable intelligent, scalable, and energy-efficient buildings.

1. Introduction

Building management has experienced significant transformations in recent years, driven by rapid technological advancements and innovative practices. This transformation is particularly evident in the Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) system, which affects a building’s sustainability and operational efficiency [1]. In intensively used buildings like hotels, efficient energy management is particularly important. HVAC systems are major users of electricity. Optimising energy consumption not only reduces costs but also minimises building carbon footprint, aligning with sustainability goals [2,3]. Moreover, in the indoor air-conditioned environment of buildings, water quality of cooling towers of air conditioners needs to be closely monitored [4]. Poor water quality can lead to health risks, damage to plumbing and HVAC systems, and negative occupant experiences. Notably, the risk of Legionella’s disease transmitted via water-borne droplets from contaminated cooling towers is deadly and regulated by health authorities.

However, maintaining proper HVAC systems often requires energy-intensive treatment processes to ensure the water quality of cooling towers of air conditioners to protect participants’ health [4,5,6,7]. In this Century, the digital twin technology has emerged as a powerful tool to address these challenges by creating virtual replicas of physical assets, processes and systems [8,9,10,11,12]. However, the integration of digital twins with other supporting technologies like building information models (BIM), the Internet of Things (IoT), and building management systems (BMS) is critical for smart construction [10].

In this study, we define a digital twin as the virtual representation of a building, where the digital environment serves as a “platform to link physical, cyber and social infrastructure systems and to provide a data-driven decision-making platform through a variety of models and methods” [13]. Digital twins, therefore, enable the simulation, monitoring and optimisation of various aspects of building operations, potentially leading to enhanced sustainability outcomes. Recent studies have shown that digital twins can significantly improve energy efficiency and water management in buildings [14,15,16]. Generally, these benefits stem from the ability of digital twins to improve energy efficiency through predictive maintenance and real-time adjustments based on building occupancy and weather conditions.

Yet, despite the potential benefits of digital twin applications in promoting sustainability, specifically in monitoring and optimising energy and HVAC systems, the underlying mechanisms and outcomes over time remain underexplored. Even after a digital replica is built, issues pertaining to “data and model semantics, missing data, data quality and modelling” mean that it is difficult to make full use of its full capability in operation and achieve its promise in delivering potential environmental sustainability benefits [17]. In other words, urban digital twin challenges are mainly related to implementation and monitoring. Studies that tracked the empirical sustainability performances of digital twin applications over time are lacking. Hence, this research aims to address this gap with four major objectives:

- To develop a conceptual framework that illustrates the evolution of digital twin technology for HVAC energy management—from descriptive to predictive to autonomous capabilities.

- To document and analyse the implementation of distinct digital twin strategies within a case study hotel, highlighting their technical characteristics and approaches to energy optimisation.

- To quantify and compare HVAC energy consumption and performance metrics across different stages of digital twins using high-resolution sensor data.

- To examine the relationship between the level of digital twin sophistication and measurable improvements in HVAC energy efficiency through statistical and performance-based analysis.

Overall, this study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on sustainable practices in buildings and provides practical insights for applying smart technologies in HVAC systems to optimise thermal comfort while maintaining energy efficiency.

2. Background: Innovations and Technology in Building Management

2.1. Global Trends

Building management has experienced significant transformations in recent years. The digital twin technology, which creates a virtual replica of physical systems for real-time monitoring, simulation and optimisation, offers a transformative approach to building management [12] and smart city development [18]. Notably, Fuller et al. [8] demonstrated that digital twins can enhance the efficiency of energy systems by providing detailed insights and predictive analytics. Shahat et al. [19] proposed a framework for integrating digital twins with BIM and IoT for smart building applications, highlighting potentials for significant energy savings and improved occupant comfort. Petri et al. [20] integrated BIM and IoT devices to conduct a dynamic analysis of building performance. Buhalis and Leung [21] highlighted how digital twins can be used to create detailed models of hotel buildings and their energy systems, allowing for more precise management and optimisation of resource use. They found that digital twins can significantly enhance energy efficiency by enabling predictive maintenance and real-time adjustments to building systems based on occupancy and weather conditions.

Tahmasebinia et al. [16] examined the use of digital twins for sustainable building management. Their study demonstrated how digital twins can integrate data from various sources, including IoT sensors, BMS, and weather forecasts, to create a comprehensive view of a building’s energy and water consumption patterns. This integration allows for more accurate forecasting and optimisation of resource use, leading to substantial energy and water savings. Khajavi et al. [22] presented a case study of digital twin implementation in a commercial building, demonstrating energy savings of up to 20% through optimised HVAC operations.

2.2. The Case of Hong Kong

The application of digital twins in the building sector in Hong Kong’s complex urban environment is an emerging field with significant potential for improving energy efficiency. Hong Kong, characterised by its dense population, large number of visitors and subtropical climate, presents distinctive challenges and opportunities for implementing the digital twin technology in buildings. Recent advancements are exemplified by Lee et al. [23], who explored the integration of IoT sensors and smart energy meters in a living-lab-based case study. Their work defined the fundamental elements of a digital twin system, providing the groundwork for more sophisticated digital twin applications. Li et al. [24] further developed a novel approach using real-time big data analytics to improve HVAC energy efficiency in commercial offices. Their method, which involves estimating optimal setpoint temperatures and implementing occupancy-based controls using low-cost IoT sensors, shows promise for optimising HVAC systems, which account for a significant portion of energy use in Hong Kong’s buildings.

Despite these advancements, several critical research gaps persist in the applications of digital twins in buildings. While existing studies suggest potential benefits of the digital twin technology, there is a need for a more rigorous quantification of these benefits, particularly in terms of energy efficiency and savings. There is a notable lack of focused studies on HVAC systems, which are heavy users of electricity and need regular maintenance in hotels or other commercial buildings relying on central air-conditioning 24/7 in tropical and subtropical regions throughout the year. Moreover, the integration of digital twins with existing BMS presents both opportunities and challenges that require further investigation [25].

Over time, there is a lack of longitudinal studies evaluating the performance of different digital twin applications. Wong and Loo [26] is an exception but their study focused on different types of sustainable building features generally and feedback loops. To date, the long-term impact of digital twin applications on building operations remains underexplored. To address these gaps, this study aims to provide a detailed assessment of energy consumption and efficiency of various HVAC digital twin modes in a case study hotel in Hong Kong. By comparing and quantifying the influence of digital twin applications on HAVC energy consumption, this research contributes to the growing body of knowledge on sustainable practices in the building sector and provides practical insights for building managers and policymakers.

3. Methodology

3.1. The Conceptual Framework

This section proposes a conceptual framework for implementing digital twin technology in hotel HVAC systems, with a specific focus on energy efficiency. This framework guides the methodological approach and contextualises the subsequent analysis of empirical findings from the case study hotel. It conceptualises digital twin implementation as a progressive development across distinct stages of increasing sophistication and capability. Each stage represents a specific approach of utilising digital twin technology for managing hotel HVAC systems, with distinct technical requirements, operational characteristics, and potential benefits.

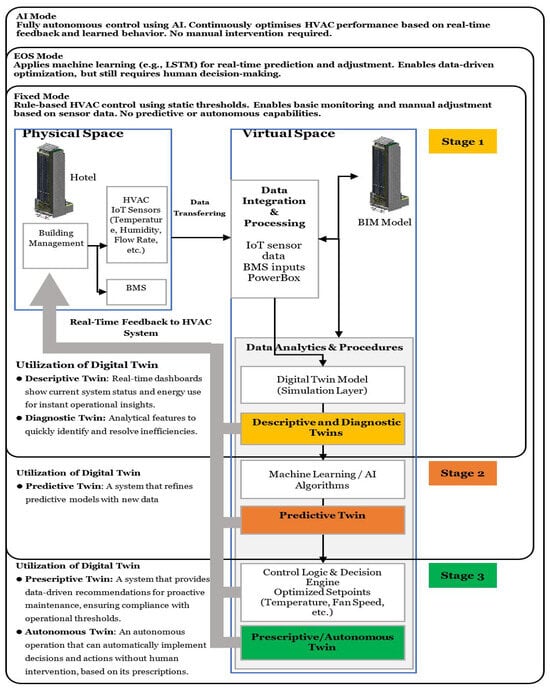

At the core of this framework is the bidirectional relationship between the physical (hotel building and HVAC systems) and virtual space (digital representation). In the physical space, the hotel’s HVAC system comprises the central chiller plant, cooling towers, and associated pumps and equipment. The virtual space contains the digital representation of the physical system, providing precise geometric and parametric information about the HVAC components. The data integration layer, implemented on cloud infrastructure, serves as the nexus connecting physical and virtual spaces. Data analytics procedures process this integrated information to enable increasingly sophisticated capabilities specific to each stage of digital twin implementation. Theoretically, we propose three stages of digital twin development, each focusing on different capabilities of digital twins in applications [13,27,28,29]. All real-time sensor data are converted to a unified set of units (SI units) within the data integration layer of the digital twin. This standardisation creates a single information space for measured values, ensuring that disparate inputs (temperature in °C, energy in kW, flow in L/s, etc.) are compatible. Additionally, prior to modelling, we apply appropriate normalisation so that variables with different scales can be integrated into machine learning algorithms in a comparable manner.

Stage 1, designated as Descriptive and Diagnostic Twins, forms the foundation of digital twin implementation. This stage focuses on establishing an accurate real-time representation of a hotel’s HVAC system and creating baseline visualisation capabilities. The primary objective at this stage is to develop a comprehensive digital model that mirrors the physical system’s current state and operational characteristics. This includes mapping the physical components in a BIM environment, establishing data connections through IoT sensors and BMS integration, and implementing real-time monitoring dashboards. At this stage, the digital twin component enables visualisation of current operational states. It serves primarily monitoring rather than control purposes, providing operators with enhanced visibility into system performance through integrated dashboards [30].

Stage 2 introduces Predictive Twins, which build upon the foundation established at Stage 1 by incorporating forecasting capabilities. The methodological emphasis in this stage shifts towards implementing machine learning (ML) and advanced analytics to anticipate future states of the HVAC system. This predictive capacity enables operators to foresee potential energy consumption patterns and water quality issues before they occur. Predictive Twins utilise historical operational data to train mathematical models that can forecast system behaviour under various conditions, allowing for proactive management of resources. This stage represents a significant advancement over traditional reactive approaches to HVAC management, introducing the capacity for preventive action based on data-driven predictions.

Stage 3, comprising Prescriptive and Autonomous Twins, represents the most advanced implementation of digital twin technology. Prescriptive Twins extend predictive capabilities by not only forecasting future states but also generating specific recommendations for system optimisation. Autonomous Twins further elevate this capability by implementing automated decision-making processes that can execute control actions without human intervention. This stage incorporates sophisticated artificial intelligence algorithms that continuously learn from system performance and environmental conditions to optimise operations for both energy efficiency and water quality management. The focus at this stage involves developing robust control algorithms that can safely and effectively manage complex HVAC systems while meeting multiple operational objectives simultaneously. Security and multi-party engagement are further supported by blockchain [25].

The progression across these three stages represents increasing levels of digital twin intelligence and automation, from passive monitoring to active control. Each stage builds upon capabilities of the previous stage, creating a cumulative advancement in digital twin functionality. This staged approach allows for incremental implementation, where organisations can begin with foundational elements before progressing to more advanced capabilities as technical capacity and organisational readiness evolve.

In the subsequent sections, we describe how this framework is applied to analyse the specific digital twin implementations in the case study, detailing the methods used to collect and analyse data on energy consumption and water quality across different operational modes.

3.2. The Case Study Hotel

The case study hotel is located in Hong Kong. It first opened in 2013 and temporarily ceased operations in early 2020 due to the COVID-19 situation. The hotel has used digital twin applications for HVAC systems since its first operation. Major upgrades were conducted starting from 2018, including the implementation of an Artificial Intelligence (AI) mode. This study has obtained the relevant databases from January 2013 to December 2019 to achieve the four research objectives. Due to issues like incomplete data, the subsequent analysis has been based on selected periods during the entire study period.

The digital twin platform implemented in the case study hotel was built upon the BIM system originally developed during the hotel’s construction phase using Autodesk Revit. This Autodesk Revit-based BIM with Level of Detail (LOD) 400 provides a comprehensive digital representation of the physical building, encompassing detailed geometric and parametric information related to structural elements, mechanical systems, and HVAC components. Its continued use throughout the building’s operational lifecycle has enabled a seamless transition from design and construction to facility management. The BIM environment plays a central role in the digital twin architecture by supplying accurate spatial and equipment metadata necessary for integrating real-time operational data from IoT sensors and BMS.

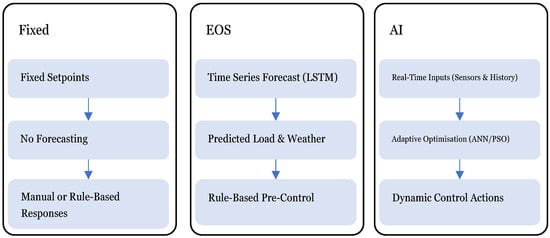

Digital twin implementation followed a phased approach aligned with the conceptual framework, moving progressively from descriptive and diagnostic capabilities to predictive and prescriptive functionalities. This study focuses specifically on the HVAC implementation and its evolution over time. The main differences of the HVAC control strategy at different stages of the digital twin application are listed in Figure 1. In brief, the initial Fixed Mode corresponds to a Descriptive and Diagnostic Twin, wherein the HVAC system is digitally mirrored through integration of the BIM model with real-time data from IoT sensors and the BMS. Essentially, HVAC control parameters are maintained at constant setpoints, without dynamic adjustments to external environmental conditions. The next stage, the Energy Optimisation Solution (EOS) Mode, constitutes a Predictive Digital Twin. The implementation layer incorporates forecasting capabilities and introduces rule-based optimisation logic that adjusts HVAC operating parameters in response to changing environmental conditions. A key component of the predictive architecture is a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural network that forecasts HVAC energy consumption. The most advanced implementation, the AI Mode, corresponds to the Prescriptive and Autonomous Digital Twin stage. Introduced in 2018, this mode integrates AI algorithms to not only predict but also optimise and autonomously control the HVAC system. The AI-controlled engine combines an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) for system behaviour modelling with a Particle Swarm Optimisation (PSO) algorithm for determining optimal control setpoints. These characteristics will be further elaborated and analysed later.

Figure 1.

Strategy comparisons of three stages of digital twin applications in HVAC.

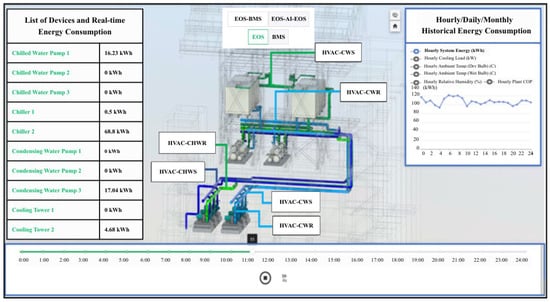

The digital twin dashboard (e.g., Figure 3) is not a stock BIM module but rather a custom extension built on the BIM model. We linked the BIM’s 3D environment with the hotel’s BMS using our proprietary PowerBox platform. This integration allows real-time sensor data from the BMS (temperatures, flows, equipment statuses, etc.) to stream into the BIM-based dashboard, updating the visualised operating state live. Additionally, the platform incorporates AI-driven forecasting and control: for instance, predicted values from the LSTM model (Stage 2) and optimal control setpoints from the ANN+PSO system (Stage 3) are fed into the dashboard and the BMS. In practice, this means the system does not just display current conditions—it also shows forecasted trends (like predicted energy efficiency or temperature) and can adjust HVAC settings automatically via the BMS interface. In summary, the BIM model provides geometric context, while the forecasting and autonomous control behaviours are implemented through custom software (PowerBox) connected to the BMS and IoT data streams.

Real-time data integration was accomplished via the hotel’s BMS and IoT network. The chiller plant and major HVAC equipment were monitored through the BMS, using standard protocols (BACnet/IP for HVAC controls and Modbus for energy meters) to expose their data. These BMS data points were connected to the cloud-based PowerBox platform through a gateway that publishes updates in real time. In parallel, dedicated IoT sensors (e.g., water quality probes and environmental sensors) were linked via IoT gateways over the building’s network, streaming data (using MQTT) to the cloud. The PowerBox platform aggregates all incoming data into a unified cloud database, effectively acting as a bridge between on-site hardware (sensors, PLCs, and BMS controllers) and the digital twin software.

The integration of these three digital twin stages into a unified platform is enabled by the PowerBox Platform, which serves as the central hub for data ingestion, processing, and application. This platform aggregates data from 1416 IoT sensor points distributed throughout the HVAC system. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sensors, ranging from energy meters, flow sensors, temperature probes, to equipment status indicators. These sensors measure energy consumption at 15-min intervals using kWh meters installed on chillers and pumps. This comprehensive sensor network provides high-resolution data necessary for accurate digital twin operation. A detailed diagram is shown in Appendix A.

Table 1.

Collected parameters from 1416 IoT sensor points used in the HVAC system.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

To evaluate the impact of digital twin implementation on HVAC energy performance, a comprehensive dataset was collected from the case study hotel when all three modes of digital twins were in operation from January 2018 to December 2019. This dataset includes hourly records from IoT sensors integrated into the HVAC system, as well as data aggregated via the PowerBox platform and BMS. The observation period captures all three operational modes—Fixed, EOS, and AI—implemented at different times as the hotel progressed through the descriptive, predictive, and prescriptive digital twin stages. A total of 17,520 hourly records were collected over the two-year period. Each record includes time-stamped values for energy consumption, cooling load, system temperature metrics, ambient conditions, and the active control mode. Table 2 shows the parameters collected in the HVAC system. After merging date and time fields into a unified date-time feature, the data was sorted chronologically and checked for temporal consistency. No significant time gaps longer than one hour were detected, and short gaps were minimal, eliminating the need for interpolation. However, because the three modes were deployed in different time periods, external factors (seasonal weather, occupancy fluctuations, etc.) could influence their performance. To mitigate this, we adopted two strategies. First, we stratified the data into five operational groups (Table 3) by ranges of cooling load and ambient conditions, ensuring that we compare modes under similar environmental stresses. Second, we created a “balanced” comparison dataset by randomly sampling an equal number of hourly records (n = 1922) for each mode, drawn from across the full period of each mode’s operation. This balanced dataset distributes each mode’s data across various times of year, roughly aligning the seasonal conditions represented for each mode. While these steps cannot eliminate all external variability, they improve the fairness of comparisons and reproducibility of our analysis.

Table 2.

Collected parameters used in the HVAC system.

Table 3.

Five groups of cooling load and wet bulb ambient temperature ranges.

Next, we turn to the technical evaluation of three HVAC operation modes—Fixed, EOS, and AI. These modes represent a progression in control sophistication. The performance of each strategy is assessed based on energy consumption, cooling load response, and Energy Efficiency Ratio (EER). While total energy consumption provides insight into overall usage, it does not account for the amount of cooling delivered per unit of energy consumed. Therefore, this study uses EER as a more meaningful metric for comparing operational performance across different control modes. EER normalises energy input against cooling output, allowing for a fair comparison of system efficiency under varying load conditions. This is particularly important in HVAC systems where cooling demand fluctuates throughout the day [31]. By evaluating EER, the study captures both energy use and thermal performance, providing a more accurate assessment of control strategy effectiveness. EER is a widely used metric for evaluating HVAC cooling efficiency, defined as the ratio of cooling output to electrical input. In this study, we calculate EER on an hourly basis as:

This definition is equivalent to the coefficient of performance (COP) expressed in mixed units (BTU/Wh). For reference, 1 W of power input equals 3.412 BTU/h of cooling; therefore, an EER of 3.9 BTU/Wh corresponds to a COP of about 3.9, which is typical for an efficient central chiller system. All EER values reported in this study use this formula, ensuring consistency across modes and analyses. Unlike raw energy consumption, which only captures usage, EER measures how efficiently that energy is used, making it a more suitable metric for comparing control strategies under varying thermal loads. In this study, EER is used to evaluate the real-time performance and energy optimisation of different digital twin modes, including Fixed, EOS, and AI controls.

Data cleaning involved removing records with invalid or missing values in key fields such as system energy consumption and cooling load. Specifically, over 1500 records with zero or negative values were excluded, as these are physically implausible in HVAC operation. Outlier detection was performed using both statistical and domain-specific approaches. Records with a Z-score greater than 3 in EER were flagged as statistical outliers, while domain knowledge identified 53 records with EER values exceeding 100 as unrealistic. These outliers were removed from the dataset to ensure robustness. Moreover, prior to modelling, all continuous features (e.g., temperatures, loads, humidity) were normalised to a 0–1 range based on min-max scaling derived from the training subset, to ensure stable model training. Categorical features, where applicable, were appropriately encoded (though the majority of our inputs were continuous sensor readings).

Feature engineering was conducted to support more granular analysis. This included creating normalised EER values (adjusted for ambient temperature and cooling load), as well as binning features for temperature and load ranges. These transformations enabled consistent comparisons across different operational and environmental conditions. The final cleaned dataset revealed an imbalance in the number of records per mode: the EOS Mode accounted for 11,866 records, the AI Mode for 2156, and the Fixed Mode for 1922. To enable fair statistical comparisons between the modes, the dataset was down-sampled to include an equal number of records (1922) per mode. For within-mode analysis, the original unbalanced dataset was retained to preserve the natural distribution and frequency of each control strategy in practice.

Then, descriptive statistics are computed to characterise the distribution of each performance metric, including mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum values per mode. To assess statistical differences in EER between modes, the distribution of EER values is first tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. If the normality assumption is violated, a non-parametric statistical approach is adopted. The Kruskal–Wallis H test is then used to determine whether there are statistically significant differences in EER distributions among the three control modes based on the balanced dataset. Where the Kruskal–Wallis test indicates significant differences, Dunn’s post-hoc tests are conducted with Bonferroni corrections to identify which specific pairs of modes differ significantly. These methods are selected for their robustness in handling non-normally distributed data and unequal variances.

4. Results

4.1. Visualisation and Applications of the Conceptual Framework

Building upon the conceptual framework, this section illustrates practical applications of the digital twin technology across three levels of sophistication. The Descriptive and Diagnostic, Predictive, and Prescriptive and Autonomous stages correspond to three implemented control strategies within the case study hotel: Fixed, EOS, and AI Modes, respectively.

The evolutionary digital twin model is visualised in Figure 2, which captures both the physical and virtual components of the system. We discuss the characteristics in detail below.

Figure 2.

Digital twin architecture and maturity progression in hotel HVAC systems. Notes: Physical components and IoT sensors transfer real-time data to a virtual space, where simulation, machine learning, and control logic are applied. The three stages—Descriptive (Fixed), Predictive (EOS), and Prescriptive/Autonomous (AI)—illustrate the evolving sophistication of digital twin implementations.

4.1.1. Stage 1: Fixed Mode

The Fixed Mode represents a conventional, rule-based HVAC control strategy commonly found in legacy building energy systems. In this mode, key equipment such as chillers, pumps, and cooling towers operate based on static schedules and predefined temperature setpoints, without consideration for real-time feedback from environmental sensors or internal system loads. For instance, chillers may be activated or deactivated strictly according to time-of-day or fixed temperature thresholds, with no dynamic adjustment to fluctuating cooling demand or external weather conditions.

Within the digital twin framework, the Fixed Mode was modelled by enforcing deterministic control logic derived from historical operational patterns. This approach assumes no predictive capability or adaptive behaviour: equipment operation remains fixed regardless of short-term variations in ambient temperature or internal load. As a baseline strategy, the Fixed Mode serves as a reference point for evaluating the potential improvements introduced by more intelligent, data-driven control modes such as EOS and AI. However, due to its rigid nature, the Fixed Mode often results in operational inefficiencies—particularly under part-load conditions or during mild weather—where equipment may run unnecessarily or spaces may be overcooled to maintain conservative safety margins.

The fixed temperature setpoints used in this mode were determined through a grid search approach, which systematically evaluated various setpoint combinations across three daily periods: night (22:00–09:59), day (10:00–16:59), and evening (17:00–21:59). The best-performing combination was selected based on its ability to minimise RMSE between modelled and actual energy consumption. The final setpoints applied in the Fixed Mode were: Night: 22.0 °C, Day: 24.0 °C, and Evening: 23.0 °C, resulting in an RMSE of 24.27 kWh. To enhance the evaluation of this mode, a Random Forest regression model was trained to predict EER using ambient temperature, cooling load, and hour of day as input features. The Random Forest regression model was implemented with 100 estimators (trees) using the scikit-learn library. We found that increasing the number of trees beyond 100 yielded diminishing returns; other hyperparameters were left at defaults after confirming they were adequate via a brief grid search on tree count and max_features. The model was trained on 70% of the dataset and tested on the remaining 30%, enabling accurate estimation of EER values across the full dataset. These predicted EER values were then used to estimate energy consumption under fixed operation. This combination of fixed scheduling and data-driven efficiency modelling provides a robust baseline for comparison with more advanced control strategies [32].

4.1.2. Stage 2: EOS Mode

The EOS Mode introduces a predictive control layer using ML, specifically a LSTM neural network. The LSTM model was trained to forecast short-term cooling load and ambient temperature conditions based on historical data. Input features included lagged values of cooling load, ambient dry-bulb and wet-bulb temperatures, hour of day, and day of week—capturing both temporal dynamics and cyclical patterns. The LSTM architecture (two layers of 64 units each) was determined through experimentation: 1 to 3 LSTM layers (with 32–128 units) were tested, and a 2-layer 64-unit configuration offered the best validation performance without overfitting. We applied dropout (20%) between LSTM layers to further curb overfitting. Early stopping with patience = 5 was used, and the final model was selected after ~50 epochs when validation loss ceased improving. Training was conducted using MSE as the loss function and the Adam optimiser with a learning rate of 0.001. A 70/15/15 data split was used for training, validation, and testing, respectively, and early stopping was applied to prevent overfitting. The forecasting horizon spanned one to three hours, providing sufficient lead time for proactive control.

Forecasted values were fed into a rule-based logic layer, which adjusted chiller staging, supply water temperature setpoints, condenser water temperatures, and pump sequencing based on predicted demand. The EOS Mode was implemented in the HVAC digital twin by integrating the LSTM-based forecast engine with a dynamic rule set that simulates real-time control decisions driven by short-term predictions. While this study reports the EOS Mode used in the case study hotel, it is recognised that other ML approaches, such as broad learning system, may be implemented elsewhere [33].

4.1.3. Stage 3: AI Mode

The AI Mode represents the most advanced control strategy in this study, combining predictive modelling with real-time optimisation. The ANN architecture and PSO hyperparameters were initially chosen based on literature guidelines and then refined through trial runs. We started with a relatively large ANN architecture to capture complex nonlinear relationships, then trimmed it to balance model complexity with predictive accuracy (avoiding overfitting). The final four-layer ANN (256 → 128 → 64 → 32 neurons) was the best-performing model on validation data—adding more layers or neurons beyond this yielded only marginal improvements. Similarly, for the PSO component, we experimented with different swarm sizes and iteration limits. We found that a swarm of 50 particles and up to 100 iterations per optimisation cycle provided near-optimal results; larger swarms or more iterations did not significantly improve outcomes but would increase computation time. Key training hyperparameters (learning rate 0.001, batch size 32, etc.) and PSO settings (swarm size 50, inertia weight 0.7, cognitive/social coefficients 1.5, etc.) are detailed in Appendix B for transparency.

4.2. Mode-Specific Performance Analysis

This section presents the results of digital twin simulations for three HVAC operation modes over a full but imbalanced operational dataset. The analysis focuses on a key performance metric: EER, representing the cooling output per unit of energy consumed. To capture how performance varies under different environmental and thermal stress conditions, the dataset was stratified into five operational groups (G1–G5) based on cooling load and ambient temperature ranges. These groups reflect a spectrum of real-world scenarios, from low-demand conditions to high thermal stress. Table 3 shows that the five groups based on cooling load intensity and ambient wet-bulb and dry-bulb temperatures. Group 1 includes low-load, cool-temperature conditions, progressing through to Group 5 based on 20-percent quartiles, which captures peak-load, high-temperature conditions.

These groupings allow for a fair and detailed comparison of how each control strategy performs under different levels of thermal stress. A central element of the analysis is the use of digital twin technology, which serves as a data-driven replica of the physical HVAC system.

The descriptive statistics values for each mode across these groups are presented in Table 4. Overall, the AI Mode consistently achieved the lowest average daily energy consumption and the highest energy efficiency, recording the top or similar EER in most groups. For instance, in Group 3, which represents moderate cooling load conditions, the AI Mode reached an EER of 4.21 BTU/Wh, outperforming the EOS Mode (3.90) and the Fixed Mode (3.87). The AI Mode also maintained high EER values above 4.0 in Groups 2, 3, and 4, demonstrating strong adaptability to changing load conditions. The EOS Mode, while slightly less efficient than the AI Mode in most groups, offered greater consistency than the Fixed mode. For example, in Group 1, the Fixed mode’s EER has a standard deviation of 4.00, indicating extreme variability and a lack of robustness under low-load conditions. In contrast, the EOS and AI Modes showed lower standard deviations, reflecting more stable and reliable performance across all scenarios. From a total energy perspective, AI Mode delivered the best balance between efficiency and consumption. It achieved an average EER of 3.79 BTU/Wh with the lowest daily energy use at 841.94 kWh, compared to 1078.28 kWh for the Fixed Mode and 1698.13 kWh for the EOS Mode. Although the Fixed and EOS Modes achieved slightly higher average EER (3.82), their higher energy consumption suggests a trade-off between stability and total energy savings. These findings highlight the value of intelligent, self-optimizing control strategies in improving both energy performance and operational robustness. The following subsections provide detailed analysis of each control mode, including their simulation setups, group-specific performance, and the behaviour of their predictive models.

Table 4.

Average EER (BTU/Wh) per group.

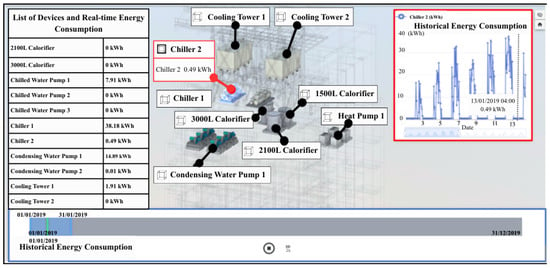

4.2.1. Fixed Mode

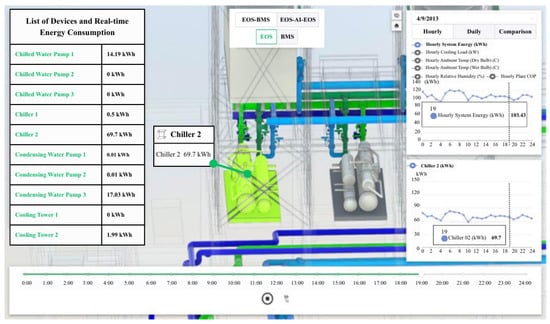

Under the Fixed Mode (Stage 1), the digital twin typically operates at a descriptive maturity level, providing real-time visibility into HVAC energy usage. As exemplified in Figure 3, the interface features a 3D layout of the system, displaying real-time energy consumption values for each major component. Historical energy trends are also accessible for diagnostic analysis; however, the system lacks forecasting capabilities or automated recommendations. Control is entirely manual and rule-based, with no adaptive logic or predictive analytics in place. This configuration reflects a traditional static control logic, where predefined temperature setpoints remain fixed regardless of ambient conditions or system demand. Serving as a baseline for comparison with more advanced strategies, the Fixed Mode offers insight into system behaviour, energy consumption, and performance trends without leveraging any predictive models or real-time optimisation techniques.

Figure 3.

Digital twin dashboard at Stage 1 (Fixed Mode). Notes: The interface displays real-time and historical energy consumption of HVAC equipment without predictive modelling or AI control. Operators manually monitor and adjust systems based on static thresholds and past behaviour.

The energy efficiency of the mode can be assessed using the EER, calculated across five operational groups (G1–G5) stratified by cooling load and ambient temperature. Refer to Table 4, the Fixed Mode achieved its highest average EER in Group 2 at 4.16 BTU/Wh, corresponding to moderate thermal load conditions. Similarly, Groups 3, 4, and 5 all demonstrated strong performance, with mean EER values of 3.87, 3.69, and 3.81 BTU/Wh, respectively, indicating consistent efficiency under increasing thermal stress. However, in Group 1, which represents low-load, mild environmental conditions, the average EER dropped to 3.55 BTU/Wh, accompanied by a notably high standard deviation of 4.00. This suggests that while the Fixed Mode may occasionally perform well under low demand, its performance is less predictable.

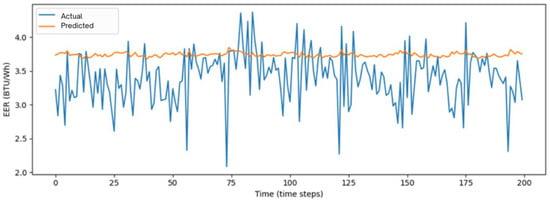

Across all five operational groups, the corresponding average daily energy consumption was 1078.28 kWh, providing a representative benchmark for evaluating energy use under the static control logic. To estimate EER values in the digital twin simulation, a Random Forest regression model was employed, using ambient temperature, cooling load, and time features as inputs. The model’s predictive accuracy is visualised in Figure 4, which shows a close alignment between true and predicted EER values over time. The model achieves an RMSE of 1.18, MSE of 1.39, and a MAE of 0.3865. These results confirm the reliability of the Fixed Mode simulation and establish a consistent baseline against which the EOS and AI Modes can be compared.

Figure 4.

Predicted versus actual EER values in Fixed Mode using Random Forest regression.

4.2.2. EOS Mode

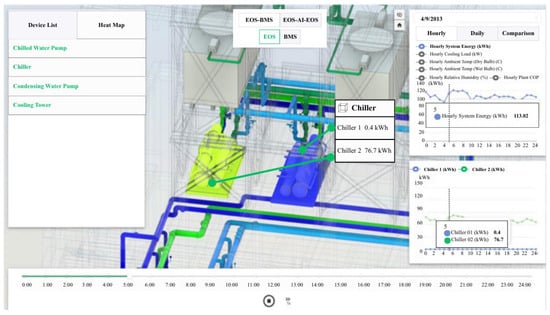

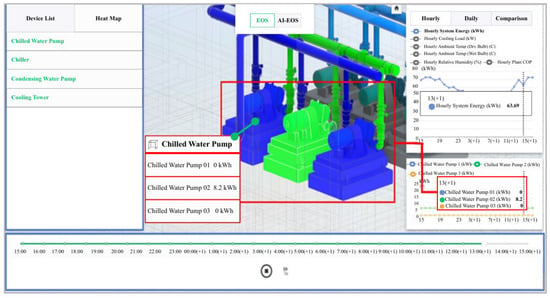

At Stage 2 (EOS Mode), the digital twin evolves into a Predictive Twin, integrating real-time sensor data with machine learning models to forecast system behaviour. It typically integrates adaptive control logic and real-time predictive analytics, representing a significant advancement over the static behaviour of the previous stage. This stage leverages ML to forecast system dynamics and optimise HVAC performance. As illustrated in Figure 5, the interface provides predictions for indoor temperature, chiller load, and EER using an LSTM-based model. Operators are supported with data-driven insights, such as advisory messages for off-peak fan adjustments. This mode still requires human intervention but is a significant step toward optimisation, enabling proactive energy management based on projected conditions.

Figure 5.

Digital twin interface at Stage 2 Predictive Twin (EOS Mode). Notes: The system integrates real-time data with machine learning–based forecasts (e.g., cooling load and EER), enabling operators to make informed adjustments. While still under manual control, the twin now supports predictive decision-making.

Across the five operational groups, the EOS Mode demonstrates improved energy efficiency and stability compared to the Fixed Mode. Refer to Table 4, the EOS Mode achieves its highest average EER in Group 3 at 3.90 BTU/Wh, followed closely by Groups 2 and 5, with EERs of 3.96 and 3.87 BTU/Wh, respectively. While Group 1 exhibits a lower mean EER of 2.94 BTU/Wh, it still outperforms the AI Mode in that group and shows better consistency than the Fixed Mode, which has significantly higher variability. Overall, the EOS Mode maintains strong performance under moderate to high-load conditions, with EER values consistently above 3.80 in Groups 2 through 5.

The total average EER for EOS Mode across all groups is 3.82 BTU/Wh, matching the average reported for the Fixed Mode but with greater consistency and lower variability. However, this improved performance comes with a higher average daily energy consumption of 1698.13 kWh, reflecting the more responsive and dynamic control behaviour of the system under EOS logic.

In Stage 2 (EOS Mode), we integrated a predictive LSTM model to estimate EER in real time. The LSTM captured the underlying efficiency trends without overreacting to short-term fluctuations (predicted EER remained around 3.9–4.1 BTU/Wh while measurements varied, see Figure 6) and achieved high forecast accuracy (e.g., RMSE ≈ 1.63). This confirms that the EOS Mode effectively leverages predictive analytics to sustain high efficiency (see Appendix B for LSTM architecture and training details). Interestingly, the EOS Mode’s predictive control did not reduce overall energy usage relative to the Fixed Mode; in fact, total daily energy consumption was higher. One likely reason is that the EOS strategy tended to be conservative—i.e., it would bring equipment online preemptively based on forecasted demand. If the forecast was higher than the actual requirement or if conditions changed slowly, the EOS controls may have over-conditioned the building (leading to energy use that the fixed schedule would have avoided). For instance, the EOS rules might start an additional chiller in anticipation of afternoon heat that turned out less severe than expected. Additionally, the rule-based nature of EOS optimised individual setpoints but did not perform a holistic energy optimisation. This could lead to inefficiencies such as running pumps and cooling towers at near-maximum when not strictly needed. The net effect is that EOS prioritised maintaining comfort with a buffer, whereas Fixed mode, despite its crudeness, sometimes left systems off during mild conditions. These factors help explain why EOS, despite being “smarter” in a predictive sense, consumed more energy in aggregate than the Fixed mode.

Figure 6.

Predicted versus actual EER values in EOS Mode using LSTM.

4.2.3. AI Mode

At Stage 3, the digital twin becomes a Prescriptive and Autonomous Twin, capable of making real-time decisions and executing control actions without human intervention. By integrating real-time data, predictive models, and closed-loop optimisation, the system shifts from decision support to autonomous control. As illustrated in Figure 7, the AI governs chiller operations by staging equipment, adjusting setpoints, and optimizing pump speeds based on forecasted loads. In the example, Chiller 01 remains off while Chiller 02 operates at an optimised setpoint of 7.2 °C, minimizing energy use while maintaining a high COP. The system also responds proactively to demand trends through pre-cooling and load scheduling. This Mode uses an ANN model combined with a PSO algorithm to dynamically adjust parameters every 15 min. The ANN, trained on 25 system features across six time steps, achieved strong accuracy (RMSE: 1.39, MAE: 0.71), outperforming the LSTM model used at Stage 2.

Figure 7.

Digital twin interface in Stage 3 (AI Mode). Notes: Prescriptive/Autonomous Twin (AI mode). The system autonomously optimises chiller operations by staging only Chiller 02 while deactivating Chiller 01. AI-driven logic adjusts setpoints and system behaviour based on forecasts and real-time inputs, with no manual intervention.

Performance results across all five operational groups confirm the AI Mode’s overall superiority in energy efficiency and control optimisation. Refer to Table 4, the AI Mode achieves the highest average EER in most groups, exceeding 4.0 BTU/Wh in Groups 2, 3, and 4. Group 3 records the peak value at 4.21 BTU/Wh, indicating high efficiency under moderate cooling loads. Even under high thermal stress in Group 5, the AI mode maintains a strong average EER of 3.98 BTU/Wh, outperforming both EOS and Fixed Modes in group-specific comparisons. While Group 1 shows a relatively lower EER of 2.85 BTU/Wh, the AI system demonstrates consistent performance across varying conditions with minimal variability. On an overall basis, the AI Mode achieves an average EER of 3.79 BTU/Wh, which is marginally lower (by approximately 0.79%) than both the Fixed and EOS modes (each at 3.82 BTU/Wh). However, this slight difference in EER is offset by a substantial reduction in energy use.

Overall, the AI Mode achieves the lowest daily energy consumption, averaging 841.94 kWh, which is 21.91% lower than Fixed mode (1078.28 kWh) and 50.42% lower than EOS mode (1698.13 kWh). These results highlight the AI system’s ability to optimise energy use dynamically, delivering significant savings while maintaining comparable—if not superior—cooling efficiency. This demonstrates the practical value of AI-driven autonomous control, especially in large, load-variable HVAC systems. However, it is important to note that these comparisons use the full, unbalanced dataset. In this dataset, the AI Mode achieved the lowest overall daily energy use (841.94 kWh), but its average EER (3.79 BTU/Wh) was similar to those of the Fixed and EOS modes (~3.82 BTU/Wh; see Table 4). This outcome is influenced by the fact that each mode’s data comes from different periods with varying levels of thermal stress. To eliminate this bias and ensure a fair comparison, we also analysed a balanced dataset in which each mode’s data covers similar ambient conditions. The results of this balanced analysis are presented in Section 4.3.

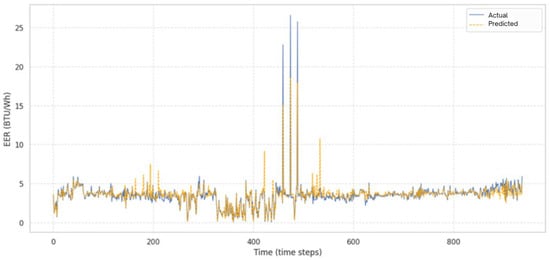

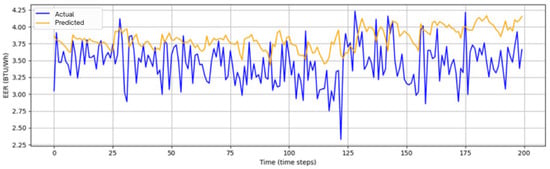

To support real-time predictions and optimisation, the ANN model was trained on 25 system parameters over six time steps. It achieved strong forecasting accuracy, with an RMSE of 1.39, MSE of 1.92, and MAE of 0.71—an improvement over the LSTM model used under the EOS Mode. As visualised in Figure 8, the predicted EER (orange line) closely follows the trend of the true EER values (blue line), despite the latter’s frequent short-term variability. The ANN model effectively captures the system’s typical behaviour, filtering out noise and enabling the PSO algorithm to make energy-efficient control decisions that remain robust under dynamic operating conditions.

Figure 8.

Predicted versus actual EER values in AI mode using an ANN model with PSO.

4.3. Statistical Evaluation and Mode Comparisons

Finally, a comprehensive performance evaluation is conducted across the three HVAC control modes using a balanced dataset comprising 1922 samples per mode. This ensures an equitable basis for comparison in terms of energy efficiency and energy consumption. Descriptive statistics reveal that the AI Mode achieves the highest mean EER at 3.93 BTU/Wh (≈3.93 COP), followed by the Fixed Mode at 3.82 and the EOS Mode at 3.70. All three modes exhibit high variability, with maximum EER values exceeding 25 BTU/Wh. Notably, the AI Mode also showed the highest variability in efficiency outcomes (EER standard deviation = 2.10, greater than in Fixed or EOS Modes). This higher variance is a direct result of the AI system’s flexible operation. Under AI control, the chiller plant operated over a wide range of loading conditions—achieving very high EER values when conditions allowed (e.g., running a chiller near its optimal load) and lower EER values during other times (e.g., light-load or rapid cycling periods when the AI was trimming energy use). In contrast, the Fixed Mode’s static setpoints led to a much narrower range of operating conditions and thus a lower EER variance. In essence, the AI Mode’s continuous adjustments caused the HVAC system to experience both extremely efficient and less efficient moments, which is reflected in the broader spread of its EER distribution.

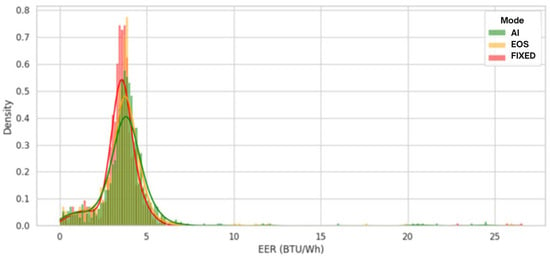

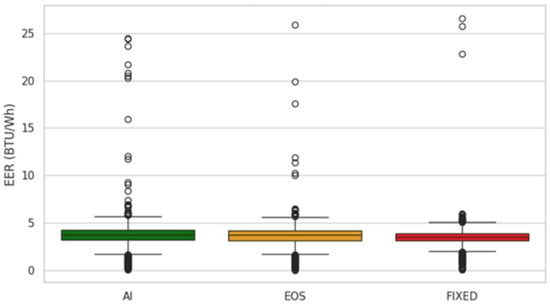

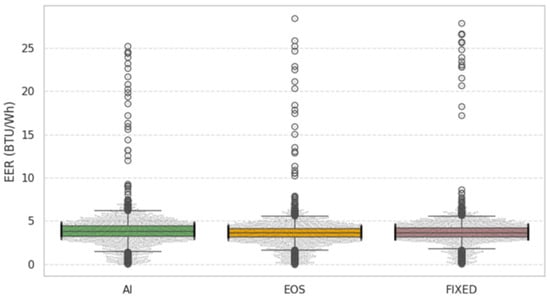

Figure 9 shows the distribution of EER for each mode using the balanced dataset (equal samples per mode). Here, the AI Mode’s density is shifted to the right of the others, indicating higher efficiency occurrences—a contrast to the unbalanced full dataset where the AI’s average EER was diluted by its operation during peak summer loads. The balanced comparison confirms that under comparable conditions, the AI Mode achieves the highest median EER. Figure 10 further supports these observations; the AI Mode shows a higher median EER, a wider interquartile range, and a greater number of upper outliers, reinforcing its ability to perform optimally across diverse conditions.

Figure 9.

Distribution of EER by control mode.

Figure 10.

Boxplots of EER across control modes.

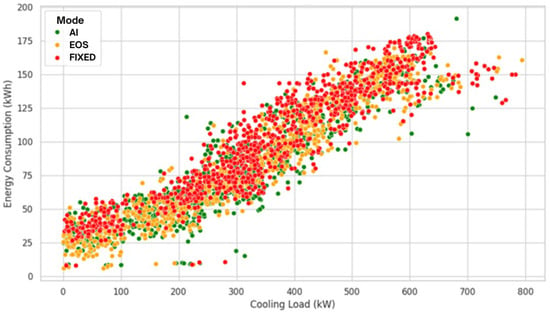

In terms of energy consumption, Figure 11 plots cooling load against energy consumption. While all modes show the expected positive trend, the AI Mode consistently tracks below the EOS and Fixed Modes, particularly at higher load levels. This suggests that the AI Mode more effectively manages energy use during periods of high demand, maintaining efficiency without excessive energy consumption.

Figure 11.

Cooling load versus energy consumption by control mode.

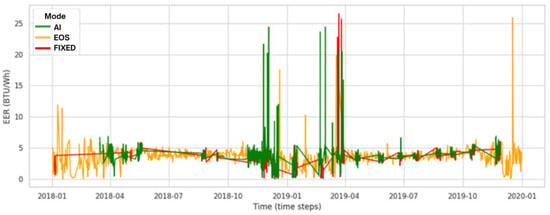

Figure 12 presents a time series of EER across the study period. The AI Mode maintains a higher and more stable EER baseline over time, while the Fixed and EOS Modes exhibit more frequent dips and prolonged periods of lower efficiency. These temporal patterns suggest that the AI Mode is better equipped to adapt to changing environmental and operational conditions. This conclusion is further supported by Figure 13, which overlays a stripplot on a boxplot of EER. The AI Mode displays a denser cluster of high-efficiency instances, reinforcing its consistent ability to deliver superior performance.

Figure 12.

Temporal trends in EER by control mode.

Figure 13.

Combined boxplots and stripplots of EER by control mode.

4.4. Model Validation and Reliability Assessment

To ensure the credibility and robustness of the digital twin simulation framework, a comprehensive model validation and statistical performance assessment are conducted using the full cleaned dataset. This dataset preserves the real-world distribution of thermal and environmental conditions, allowing for a realistic evaluation of system behaviour under each control mode, with the Fixed Mode serving as the baseline.

To statistically validate these observations, the Shapiro–Wilk test is first applied to assess normality of the EER distributions. The results rejected the assumption of normality for all three control modes, indicating that the data are not normally distributed and necessitating the use of non-parametric methods. A Kruskal–Wallis H test is therefore conducted, yielding a highly significant result (H = 48.51, p < 0.0001), which confirms that at least one mode differs significantly from the others in terms of EER. To identify specific differences between modes, Dunn’s post-hoc test with Bonferroni corrections is applied. The results show that the AI Mode significantly outperforms both the Fixed and EOS Modes, with adjusted p-values of 8.22 × 10−8 and 4.25 × 10−10, respectively. However, the difference between the EOS and Fixed Modes is not statistically significant (p = 1.0), indicating that the EOS Mode does not consistently deliver improvements over the baseline strategy.

5. Discussion

This study seeks to explore how digital twins can be progressively developed and applied to HVAC energy management in a commercial hotel environment, with the aim of moving from passive monitoring to predictive analytics and autonomous control. The phased implementation—comprising the Fixed, EOS, and AI Modes—directly reflects the conceptual framework established in Objective 1, and provides a practical demonstration of how digital twin maturity can be operationalised within a real-world setting (Objective 2).

The comparative performance analysis reveals a clear correlation between system intelligence and energy efficiency, fulfilling Objective 3 and Objective 4. Two datasets are analysed to ensure robustness: a full dataset segmented into five operational groups reflecting real-world thermal conditions, and a balanced dataset for controlled comparisons. Notably, when examining raw operational data, the AI Mode’s average EER was roughly on par with the Fixed and EOS modes (as it was tested under more demanding conditions overall). However, it still achieved considerably lower total energy consumption—reducing daily usage by 21.9% compared to the Fixed Mode and by 50.4% compared to the EOS Mode. When controlling for external factors via a balanced dataset, the AI Mode clearly outperformed the others in efficiency metrics as well, delivering an average 6.2% improvement in EER over the EOS Mode and 2.9% over the Fixed Mode. This two-pronged analysis underscores that the AI-driven twin not only reduces absolute energy use under real-world conditions but also operates more efficiently when compared on equal footing. These findings are statistically validated using the Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn’s post hoc tests (p < 0.001). The results underscore the importance of adaptive, real-time optimisation—a capability unique to the AI system. It should be noted that the three operational modes were enacted in sequence rather than concurrently, which introduces potential confounding factors (e.g., one mode’s data may come predominantly from cooler months or different occupancy levels). We addressed this by stratifying the analysis by condition group and by constructing a balanced dataset for head-to-head comparisons. Despite these measures, some caution is warranted in directly attributing performance differences solely to control strategy, as opposed to unmeasured external influences. Future studies or deployments could improve on this by testing different strategies in parallel or under more controlled conditions.

Notably, the average EER under EOS control (~3.82) was essentially identical to that of the Fixed Mode. This indicates that the rule-based EOS optimizations did not significantly enhance the inherent efficiency of the cooling system. In EOS mode, we mainly reduced equipment runtime during low-demand periods; but when the chillers were active, they often operated at similar loads and efficiencies as in Fixed mode. Consequently, total energy use in EOS mode remained high and its EER showed no improvement over the Fixed strategy—highlighting the limited impact of EOS on equipment performance. This underscores that prediction alone is insufficient unless coupled with an optimal control strategy. In our case, the EOS’s predictive control logic appears to have erred on the side of caution—ensuring thermal comfort by running equipment proactively, but in doing so, sometimes expending more energy. This finding suggests that any predictive BMS strategy should be carefully calibrated or augmented with optimisation algorithms to truly realise energy efficiency gains. Interestingly, the AI Mode exhibited a lower average EER (~3.8) than both the Fixed and EOS modes (~4.0), despite delivering the highest energy savings. This apparent paradox can be explained by the AI’s control strategy. By minimising operating hours and often running equipment at partial load to avoid excess cooling, the AI sometimes operated the chillers outside their peak efficiency zone—which reduced instantaneous EER. However, because the AI Mode only ran the equipment when necessary and for shorter durations, the total daily energy consumption was still the lowest of all modes. In essence, the AI control traded a bit of efficiency (lower EER at certain times) for large energy savings overall.

Another key insight lies in the implementation of ML models at different digital twin stages. In the Fixed Mode, a Random Forest model was used diagnostically to understand energy patterns under constant setpoints. The EOS Mode introduced a predictive LSTM-based model, but its static optimisation logic limited its effectiveness. In contrast, the AI Mode integrated an ANN with a PSO algorithm, enabling multi-variable, real-time control across 14 operational parameters. This progression from prediction to prescriptive/autonomous control underscores the conceptual and technical leap required to realise autonomous digital twins. The PowerBox platform has played a critical role in enabling this evolution. Its layered architecture—comprising data ingestion, processing, and application layers—ensures scalable and secure integration of over 1400 IoT data points. This infrastructure not only supports real-time control but also simplifies historical analysis, fault detection, and performance visualisation, making it a robust foundation for future digital twin enhancements.

Practically speaking, the AI-controlled system represents a major advancement in autonomous building operations. It reduces reliance on manual intervention, adapts to environmental variability, and achieves energy savings without compromising occupant comfort. Such capabilities are highly relevant for hotel operators seeking to optimise energy use while maintaining service quality. However, the study also acknowledges limitations. The AI model was trained on site-specific data and may require retraining for deployment in different climates or building typologies. Additionally, while the system optimises for energy efficiency, it does not yet incorporate cost-based or carbon-aware objectives. Expanding the control logic to include economic and environmental trade-offs represents a promising direction for future work.

In summary, this study highlights how increasing levels of digital twin intelligence (from descriptive and diagnostics, predictive to prescriptive and autonomous) can yield measurable improvements in HVAC energy efficiency. The empirical case study validates the conceptual framework, meets the outlined objectives, and demonstrates a practical and scalable pathway for implementing intelligent building systems.

For practical recommendations, our findings translate into a clear roadmap for facility managers aiming to improve HVAC efficiency. First, adopt a phased implementation of digital twins: begin with a descriptive twin for real-time monitoring and diagnostics, then introduce predictive analytics for proactive maintenance, and finally deploy an AI-driven autonomous control as the system matures. This stepwise approach allows teams to build expertise and trust in the technology at each stage. Second, leverage existing IoT and BMS data for quick wins—for instance, analyzing sensor data can reveal inefficiencies like equipment running during low-demand periods, which can be corrected with simple schedule or setpoint adjustments. Even these early interventions can yield immediate energy savings. Finally, as demonstrated by our AI Mode achieving ~22% daily energy reduction compared to baseline, an advanced digital twin can significantly cut energy use without sacrificing occupant comfort. In practice, this means hotel operators can meet sustainability and cost-saving goals while maintaining guest satisfaction.

For integration with existing control loops, our digital twin framework is designed as an overlay to the building’s current HVAC controls, integrating in stages. In the Descriptive Twin stage, data from chillers, pumps, and sensors are aggregated in the cloud platform, but day-to-day control remains with the existing BMS (no changes to local PID loops). The twin serves purely as a monitoring and diagnostic layer. In the Predictive (EOS) stage, the twin provides supervisory inputs: it forecasts conditions and suggests adjustments to setpoints, which can be applied via the BMS’s standard control loops—essentially adding a predictive layer on top of traditional control. By the Autonomous AI stage, the integration becomes a closed-loop: the digital twin actively sends optimised setpoints to BMS controllers (e.g., via BACnet commands), thereby taking on a high-level control role. Importantly, this phased integration means our solution can be retrofitted into existing systems gradually—starting with passive monitoring, then guided adjustments, and finally autonomous control—all through the BMS interfaces without replacing the underlying HVAC control hardware.

6. Limitations and Future Work

This study has several limitations that suggest avenues for future research. First, the dataset used was proprietary and drawn from a single hotel in a subtropical climate. This exclusivity limits reproducibility and generalizability, as results may differ in other building types or climate zones. Future studies should validate our digital twin framework in more diverse settings—for example, applying it to office buildings or hotels in colder regions—and ideally use open-access data to facilitate broader analysis and replication.

Second, the three operational modes (Fixed, EOS, AI) were implemented sequentially over different time periods rather than tested concurrently. This staggered deployment introduces potential confounding factors (e.g., seasonal weather variations or occupancy changes unique to each mode’s timeframe) that complicate direct comparisons. We mitigated this issue by segmenting the data into comparable condition groups and constructing a balanced dataset for analysis; however, caution is still warranted when attributing performance differences solely to the control strategy. Future work could address this by conducting parallel experiments or employing advanced statistical controls to better isolate each strategy’s impact under equivalent conditions.

Third, the generalizability of our approach to other climates and regions requires adaptation. Our training data and results are specific to a subtropical environment (Hong Kong), where cooling dominates year-round. Deploying this digital twin framework in hotels with harsher or different climates (e.g., cold continental winters or hot, arid conditions) is feasible, but the models must be tailored to local conditions. In practice, this means retraining the predictive models with site-specific data and possibly introducing additional variables. For example, a hotel in a cold climate would need to integrate heating system parameters and frost-protection controls into the twin’s dataset and logic, since those factors were not relevant in our original case. The three-stage methodology is general in concept, but its implementation should be climate-sensitive. We advise practitioners and researchers to incorporate all relevant environmental and operational parameters—such as extreme outdoor temperature ranges, humidity control requirements, or seasonal occupancy fluctuations—when adopting this framework in a new region. This will help ensure that the digital twin’s predictions and AI-driven controls remain effective and robust under different climatic conditions.

Fourth, our study did not include a formal economic analysis of implementing the digital twin, and we relied on EER as the primary efficiency metric. We focused on technical performance improvements (energy reduction and efficiency gains) and did not quantify costs such as sensor installation, software development, training, or maintenance. While the AI-driven mode demonstrated significant energy savings (~21.9% less daily HVAC energy use than the fixed baseline), we did not assess the corresponding monetary savings or payback period. To illustrate the potential impact, if a hotel spends around $1 million annually on electricity for cooling, a ~22% energy reduction could save roughly $220,000 per year. Such savings could offset the initial investment in IoT sensors, cloud infrastructure, and integration efforts over a reasonable period. We also anticipate secondary economic benefits: optimised operations may prolong equipment lifespan and reduce maintenance or downtime costs through early fault detection. Nonetheless, a rigorous cost–benefit analysis was beyond our scope. We recommend that future work include a detailed economic evaluation, examining installation and operational costs against achieved savings to confirm the business case for this digital twin approach. In addition, future implementations should complement technical metrics like EER (equivalent to COP in our analysis) with seasonal performance metrics (e.g., SEER) and cost-based indicators (e.g., cooling cost per kWh, return on investment) to fully assess the system’s benefits and financial viability.

Fifth, another limitation lies in the scope of our optimization objectives. The digital twin’s control logic was designed to maximise energy efficiency and maintain thermal comfort, but we did not explicitly account for other factors such as indoor air quality or direct carbon emissions in the optimization process. In real-world applications, facility managers might have to balance energy savings with air quality standards or sustainability goals. Future enhancements could incorporate multi-objective optimization to address these additional considerations—for instance, simultaneously optimizing for energy use, occupant comfort, air quality, and greenhouse gas emissions. Broadening the objectives in this way would make the digital twin’s recommendations more holistic and aligned with comprehensive building performance goals.

Finally, the machine learning models employed (the LSTM for forecasting and the ANN for control optimization) were trained on historical data reflecting typical operations at our study site. These models assume relatively stable usage patterns and relationships. If building operating conditions change drastically—for example, due to an atypical event like a pandemic-related occupancy drop or an extreme weather anomaly—the models’ accuracy may degrade. In such cases, the digital twin’s predictive and control performance could suffer unless the models are retrained or adapted to the new conditions. Developing more adaptive or robust learning approaches (such as online learning or transfer learning techniques that can adjust to shifting data patterns) would further improve the twin’s resilience and reliability over time.

Despite these limitations, our case study’s progressive development from a descriptive to an autonomous digital twin demonstrates a practical and scalable pathway for intelligent HVAC energy management. Each stage provided valuable learnings and incremental benefits, culminating in a substantial improvement in efficiency without compromising occupant comfort. Future research is encouraged to build on this framework, addressing the noted limitations—by broadening data sources, testing in parallel conditions, adapting to new climates, including economic analyses, expanding optimization criteria, and enhancing model adaptability—to fully realise the potential of digital twin technology across a wider range of real-world building scenarios.

7. Conclusions

This study explores the development and implementation of a multi-stage digital twin framework for HVAC energy optimisation in a commercial hotel setting. Guided by the conceptual evolution from descriptive to predictive and prescriptive intelligence, the research addresses four core objectives.

First, a conceptual framework is developed to map the progression of digital twin technologies from basic monitoring to autonomous control. This framework serves as the foundation for system design, aligning digital twin maturity with increasing levels of data integration, modelling complexity, and control intelligence (Objective 1). Second, the implementation of three digital twin strategies—Fixed, EOS, and AI Modes —was documented in detail, each representing a distinct stage of digital twin sophistication. These modes have been deployed on a unified BIM-IoT platform, and their technical characteristics, control logic, and data processing workflows are analysed and compared (Objective 2). Third, high-resolution IoT sensor data from over 1400 sensor points have been used to quantify and compare HVAC energy performance across three levels of digital twin intelligence. Performance metrics such as daily energy consumption and EER are calculated, and control strategies have been evaluated under both balanced and full operational datasets (Objective 3). Finally, the results demonstrate a clear relationship between digital twin maturity and energy efficiency. Analysis of the full operational dataset, segmented into five groups, shows that the AI Mode achieved substantial energy savings—reducing daily energy consumption by 21.9% compared to the Fixed Mode and by 50.4% compared to the EOS Mode. These findings underscore the value of adaptive, real-time optimisation in managing complex, variable thermal conditions. Complementing this, results from the balanced dataset—used for controlled EER comparisons—showed that the AI Mode delivered a 6.2% improvement in EER over the EOS Mode and 2.9% over the Fixed Mode. Statistical analysis confirms the significance of these improvements (Objective 4), reinforcing the effectiveness of advanced, data-driven control strategies in enhancing energy efficiency while maintaining thermal comfort.

For practical recommendations, the findings translate into several actionable insights for hotel and facility managers. First, managers should adopt a phased approach to digital twin implementation: start with descriptive monitoring to establish baseline performance and data infrastructure, then introduce predictive analytics (e.g., load forecasting) for improved scheduling, and finally deploy AI-driven optimisation for autonomous control. Second, leveraging IoT sensor data can yield quick wins (such as identifying and correcting suboptimal equipment schedules or setpoints) even before advanced AI is in place. Third, significant energy savings (on the order of 20–50% reduction in HVAC energy use in our case) are achievable without compromising occupant comfort, meaning such initiatives can simultaneously reduce costs and improve sustainability metrics. Finally, it is recommended that facility managers integrate digital twin platforms with existing BMS gradually, ensuring staff are trained alongside the technology so that human oversight complements the automated controls. Overall, this study contributes a replicable methodology for digital twin implementation in hotels. It demonstrates that the evolution from passive monitoring to autonomous control is not only technically feasible but also operationally and economically beneficial as electricity consumption is a major cost for hotel operations. The study offers practical insights for hotel or facility managers and digital twin developers, while laying the groundwork for future research into multi-objective control, fault diagnostics, and cross-domain digital twin integration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.W.M.W. and B.P.Y.L.; methodology, R.W.M.W. and B.P.Y.L.; software, R.W.M.W.; validation, R.W.M.W.; formal analysis, R.W.M.W.; data curation, R.W.M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, R.W.M.W. and B.P.Y.L.; writing—review and editing, R.W.M.W. and B.P.Y.L.; visualization, R.W.M.W. and B.P.Y.L.; supervision, B.P.Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The proprietary data of the hotel is not publicly available due to commercial sensitivity.

Acknowledgments

This research is part of the initiative of the University of Hong Kong Joint Laboratory on Future Cities but does not receive dedicated financial funding. The authors would like to acknowledge the non-financial support of Million Wealth Enterprises Limited in sharing the operational data of the hotel used in this research paper. The authors are solely responsible for the research design, data analysis, interpretation of findings and writing of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Rosana W. M. Wong is employed by Yau Lee Holdings Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| BIM | Building information models |

| BMS | Building Management Systems |

| COP | Coefficient of performance |

| EER | Energy Efficiency Ratio |

| EOS | Energy Optimisation Solution |

| HVAC | Heating, ventilation and air conditioning |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LOD | Level of Detail |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| ML | Machine learning |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimisation |

Appendix A. Illustrations of the Digital Twin of the HVAC System

Figure A1 illustrates the interconnection between the chilled water loop and the condensing water loop in the chiller plant. The chilled water loop circulates chilled water supply (HVAC-CHWS) from the chiller to air handling units (AHUs) and fan coil units (FCUs) to cool the building spaces. The warmer water then returns to the chiller as chilled water return (HVAC-CHWR). Simultaneously, the condensing water loop circulates condensing water supply (HVAC-CWS) from the chiller’s condenser to the cooling tower (CT) to reject heat. The cooled water then returns to the chiller as condensing water return (HVAC-CWR). The chiller acts as the link between the two loops, cooling the HVAC-CHWS by transferring heat to the HVAC-CWS. The CT then cools the HVAC-CWS before it returns to the chiller as HVAC-CWR. This continuous cycle ensures efficient cooling throughout the building.

Figure A1.

A detailed digital twin of the HVAC system.

The digital twin enables facility managers to easily identify specific components of the HVAC system which are active at any given time. Figure A2 provides a detailed digital twin visualisation of the real-time energy consumption of the chilled water pumps and other components using a heatmap. The heatmap utilises a color gradient ranging from blue to green, with blue indicating lower energy consumption and green representing higher energy consumption. This visual representation facilitates the identification of pumps consuming more energy compared to others. By leveraging this heatmap, facility managers can swiftly evaluate the energy efficiency of individual chilled water pumps and pinpoint potential areas for optimisation or maintenance to enhance overall system performance. In Figure A2, chilled water Pump 2 consumes 8.2 kWh, while the other two pumps consume no energy. This information allows facility managers to focus their attention on the active components and make informed decisions regarding energy management and system optimisation.

Figure A2.

Digital twin visualisation of real-time energy consumption for chilled water pumps using a heatmap. Notes: Blue indicates lower energy consumption and green represents higher energy consumption.

Appendix B. Model Architecture and Hyperparameters

Appendix B.1. ANN Architecture and PSO Algorithm Settings (AI Mode)

In the AI Mode, we employed a feedforward ANN in conjunction with a PSO algorithm to autonomously manage HVAC system performance. The ANN model used a four-layer architecture with 256, 128, 64, and 32 neurons in the hidden layers, applying ReLU activations in those layers and a linear activation at the output. It processed 25 system parameters over the six most recent time steps, capturing the current state and recent trends. The ANN was trained to predict multiple outputs (including upcoming energy consumption, cooling load, water temperatures, and overall system efficiency) so that the PSO could evaluate each potential control action’s outcomes. We trained the ANN using mean squared error (MSE) loss and optimised it via the Adam algorithm (learning rate = 0.001). Training ran for a maximum of 500 epochs with early stopping (patience = 10 epochs) to prevent overfitting; this architecture was chosen after preliminary tests showed that larger networks or longer training yielded diminishing returns on validation accuracy.