Abstract

In response to the non-reusable nature and prolonged construction period of traditional foundations for temporary and transitional towers, this paper designs a fully reusable all-metal prefabricated foundation for 35 kV–110 kV transmission lines. The uplift bearing capacity of the fully metallic prefabricated foundation was investigated through a series of eight reduced-scale model tests (scale 1:3). Weathered sand and silty clay were selected as backfill materials, with relative density and foundation embedment depth as test variables. The load–displacement curves were plotted, and the ultimate uplift capacity was determined based on the load corresponding to the onset of a sharp transition in these curves. The test results demonstrated that the ultimate uplift capacity of foundations with weathered sand backfill was significantly superior to that of counterparts with silty clay under comparable conditions. Specifically, at an embedment depth of 1.2 m and high relative density, the ultimate load of the weathered sand backfill was 33.3% higher than that of the silty clay backfill. The ultimate uplift capacity increased markedly with higher relative density. When the degree of compaction increased from 0.7 to 0.9, the ultimate capacity of the weathered sand backfill increased by 100.0%, substantially exceeding the 30.4% increase observed for the silty clay backfill. Furthermore, the ultimate capacity exhibited greater sensitivity to the embedment depth in weathered sand. As the embedment depth increased from 0.5 m to 1.2 m, the ultimate capacity of the weathered sand backfill increased by 191%, far surpassing the 114% increase for the silty clay backfill. This study provides experimental evidence and theoretical references for the design and construction of assembled foundations for temporary tower structures. The conclusions of this study are based on model test conditions and require further verification through prototype tests and numerical simulation.

Keywords:

prefabricated foundation; silty clay; weathered sand; density; uplift capacity; model test 1. Introduction

China’s 14th Five-Year Plan explicitly outlines the development of a modern energy system, accelerating the construction of new-type power systems such as high-voltage transmission lines. This context places heightened demands on the timeliness of power grid construction. When transmission lines traverse complex terrain or face natural disasters, employing temporary transition towers becomes a critical technical measure for rapid power restoration and energy security assurance [1,2]. Compared to conventional cast-in-place foundations, fully metallic assembled foundations offer distinct advantages, including factory prefabrication, rapid on-site installation, reusability, and minimal environmental impact. These merits make them particularly suitable for temporary transition tower projects, aligning with the development philosophy of green construction and a circular economy [3,4,5,6].

The uplift capacity of prefabricated foundations serves as a critical performance indicator when they are used as tower foundations, and this performance is predominantly governed by the interaction between the foundation and the surrounding backfill soil. Engineering properties of the backfill, such as soil type, relative density, and foundation embedment depth, serve as pivotal factors controlling the uplift bearing mechanism [7,8,9]. Extensive research has been conducted by scholars worldwide on the bearing behavior of prefabricated foundations. Dickin et al. [10] through centrifuge testing and PLAXIS finite element analysis, confirmed that the uplift capacity of strip anchors in sand increases with the embedment ratio and density. The Hardening Soil model was able to adequately simulate the pre-peak response; however, modeling the post-peak softening behavior of deeply embedded anchors requires more sophisticated constitutive models. Choudhary et al. [11] employing model tests and numerical simulation, demonstrated that using geocell reinforcement in sand significantly enhances the uplift performance of horizontal anchor plates. The bearing capacity was increased by approximately 4.5 times, with a permissible displacement exceeding 60%. An optimal reinforcement width of 5.4 times the anchor width was identified to achieve effective load distribution. Niroumand et al. [12] via model testing and numerical simulation, validated that a new technique—Geogrid Fixed with FRP anchors (GFR)—can increase the uplift capacity of symmetrical anchor plates by 29%. This method, which involves a single layer of reinforcement directly covering the anchor plate to enhance soil anchorage, was shown to be significantly more effective than traditional geogrid reinforcement, which only provided a 19% improvement. Zhao et al. [13] systematically investigated the effects of foundation dimensions and pile inclination on the bearing performance of precast inclined pile foundations for electric poles under combined vertical and horizontal loading. Zhang et al. [14], through field tests and finite element analysis, revealed the anti-overturning mechanism of prefabricated foundations for distribution line poles under the influence of embedment depth, foundation size, load direction, and soil parameters, and proposed a practical calculation method for anti-overturning capacity based on limit equilibrium theory. Guo et al. [15] introduced a novel prefabricated multi-column Concrete-Filled Steel Tube (CFST) internal bracing system via experimental and numerical studies, demonstrating that their modified constitutive model accurately predicts the mechanical response. Wang et al. [16] proposed a new type of prefabricated multi-rib foundation for onshore wind turbines and validated its stability through scaled model tests. Considerable achievements have also been made by domestic scholars. For instance, Liu et al. [17] examined the compressive performance of metal-assembled foundations in aeolian sand areas and proposed a corresponding method for calculating the ultimate bearing capacity. Dong et al. [18], for the first time, combined model tests, full-scale tests, and numerical simulations to reveal the shape of the uplift failure surface of metal-assembled foundations in desert sandy soil foundations, thereby providing recommended values of the uplift angle critical for calculating the uplift capacity using the gravity method.

However, existing research predominantly focuses on traditional cast-in-place concrete foundations or pile foundations, while studies addressing the uplift performance of assembled foundations, particularly for temporary transition towers, remain relatively limited [19]. Assembled foundations, typically constructed with steel sections, exhibit significant differences from conventional foundations in terms of soil-structure interaction mechanisms and load transfer paths [20]. More importantly, the nature of temporary engineering projects often entails distinct quality control standards for backfill soil compared to permanent structures, and local materials are frequently adopted for backfilling [21,22]. The widespread distribution of silty clay and weathered sand in Northeast China presents two typical backfill materials with contrasting engineering properties—the former being primarily cohesion-dependent and the latter dominated by frictional characteristics [23,24,25]. Although previous studies have touched upon the various aspects mentioned above, a systematic investigation specifically targeting full-metal, reusable, modularly assembled foundations for temporary transmission towers remains lacking. This is particularly evident in the systematic comparison of different backfill soils—especially those with distinct mechanical properties such as weathered sand and silty clay—and the precise quantification of the influence of flange plate parameters. Consequently, engineering design lacks sufficient theoretical and experimental basis for guidance.

In light of this, this paper presents, for the first time, a systematic study on the uplift performance of full-metal prefabricated temporary foundations. This research aims to conduct an in-depth investigation through model tests to evaluate the relative influence of backfill soil type (silty clay vs. weathered sand), degree of compaction (0.7 and 0.9), and foundation embedment depth (0.5 m, 0.85 m, 1.2 m) on the uplift bearing capacity of a fully metallic prefabricated foundation for temporary and transitional transmission towers. By analyzing the foundation’s load–displacement curves, ultimate bearing capacity, component stress distribution, and variations in earth pressure, the study seeks to elucidate its bearing and failure mechanisms. The outcomes are intended to provide data support and a theoretical reference for the scientific design and safe construction of this category of foundations.

2. Uplift Capacity Testing of Scaled Models of Assembled Foundations

2.1. Scaled Model Design

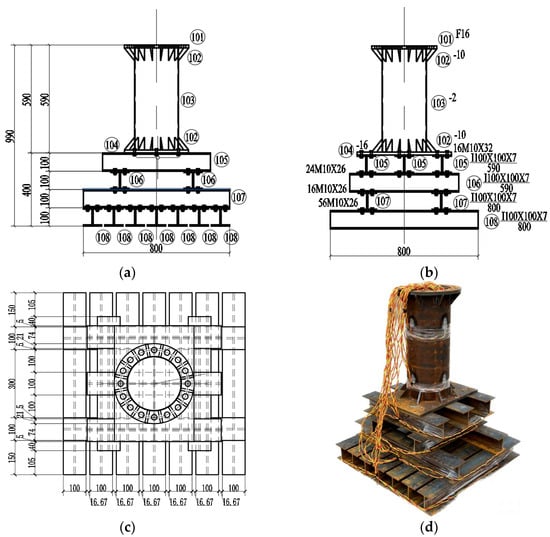

Taking into account the available testing site, loading and measurement equipment, a 1:3 scaled foundation model was selected for the bearing capacity tests. The scaled prefabricated foundation dimensions are applicable to temporary and transitional towers for 35 kV transmission lines. The assembled foundation model, as shown in Figure 1, consists of 14 I-beams and steel tube columns. The model, from top to bottom, consists of a positioning flange, a steel tube column, and connection plates. These components are connected by welding, with stiffeners installed at both ends of the steel tube column. Below the connecting plates, four layers of I-beams were fixed to the connecting plates using Chinese made grade 4.8 M10 bolts. The foundation model has base dimensions of 0.8 m × 0.8 m and a total height of 0.99 m.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the Test Foundation: (a) Front View; (b) Left View; (c) Plan View; (d) Foundation overall diagram.

To minimize the influence of model scaling on experimental results, the minimum dimension of the model foundation (e.g., a base plate of 0.8 m × 0.8 m) was designed to be significantly larger than the maximum particle size of the soil (<20 mm). This approach effectively eliminates the potential inaccuracies in soil failure mechanisms caused by foundation scaling. All structural components of the model foundation were fabricated from Q355 steel, the same material used in the prototype. Consequently, the elastic modulus E—the key parameter governing stiffness—remains identical between the model and the prototype. This ensures that the effects of scaling on stress transfer mechanisms and deformation magnitude are negligible.

2.2. Test Program Design

To investigate the influence of backfill soil type, degree of compaction, and embedment depth on the uplift bearing capacity of the fully metallic prefabricated foundation for temporary transmission towers, a total of eight test scenarios were designed for this experimental program, as specified in Table 1.

Table 1.

Test Configuration.

The degree of compaction served as the core indicator for controlling the compaction quality of both the silty clay and weathered sand. It is defined as the ratio of the dry density of the soil after field compaction to the maximum dry density obtained from a standard laboratory compaction test, which was conducted using the light compaction method stipulated in the Standard for Geotechnical Testing Methods (GB/T 50123-2019) [26].

All test foundations were constructed using an identical procedure to simulate the on-site installation of the prefabricated foundation. The process began with the excavation of a 1.2 m × 1.2 m pit, which was dug to the designated embedment depth. The model foundation was then positioned at the center of the pit. High-precision spirit levels and a laser rangefinder were employed to ensure the reaction beam was horizontal, the foundation was vertical, and the entire setup was aligned with the center of the loading system.

Backfilling and compaction were carried out manually in layers according to the Code for Design of Building Foundations [27]. The soil was compacted to the design elevation using a layered compaction technique, with each layer having a controlled thickness of 200 mm. Immediately after the placement of each layer, its dry density was measured using the ring knife method. A minimum of two measurements were taken per layer to ensure the density variability was controlled within ±10% of the target value. The placement of a subsequent layer was only permitted after the compaction quality of the current layer had met the specified acceptance criteria.

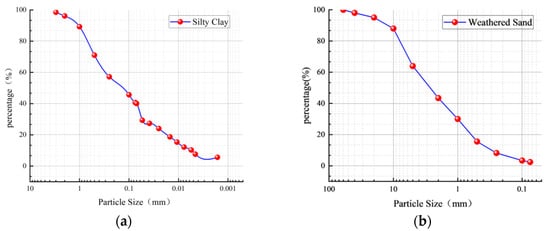

The experimental site was located at the Pile Testing Facility of the College of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Northeast Electric Power University. Backfill materials selected for this study included silty clay and weathered sand, both commonly found in the Northeast China region. The grain size distribution curves of these materials, obtained through laboratory particle size analysis, are presented in Figure 2. Furthermore, standard geotechnical tests were conducted to determine the physico-mechanical properties of the silty clay and weathered sand, with the detailed results summarized in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Grain Size Distribution Curve of Backfill Soil: (a) Silty Clay; (b) Weathered Sand.

Table 2.

Basic Physical Properties of Test Soils.

2.3. Experimental Loading Protocol

This ensured that all tests were conducted under fully drained conditions. This guarantees that the measured uplift capacity reflects the soil’s strength based on effective stress parameters, thereby avoiding the overestimation or underestimation of bearing capacity that can result from undrained effects. The uplift tests were conducted in accordance with the Chinese industry standard “Design Code for Foundation of Overhead Transmission Line” (DL/T 5219-2023) [28], employing the slow maintained load method. Prior to testing, the load was incrementally applied in stages, with each stage equivalent to approximately one-tenth of the estimated ultimate uplift capacity, to establish the loading sequence for each test case. The initial load application was twice the standard incremental load, followed by subsequent applications of equal incremental loads. The loading rate was strictly controlled not to exceed 1 kN/min. Real-time loading, supplemental loading, and constant load maintenance were implemented throughout the test. During unloading, the load was reduced in steps equivalent to twice the standard incremental load, with the final stage reducing the load to zero.

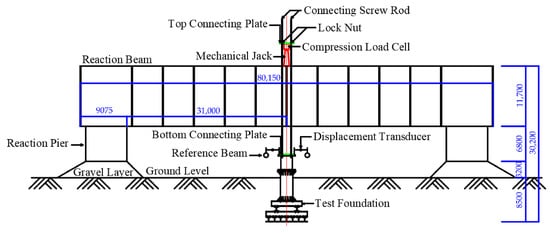

The loading system, with a maximum uplift capacity of 100 kN as shown in Figure 3, consisted of a loading connection plate, screw jack, hydraulic actuator, and reaction steel beams.

Figure 3.

Test Loading System.

2.4. Instrumentation and Measurement Scheme

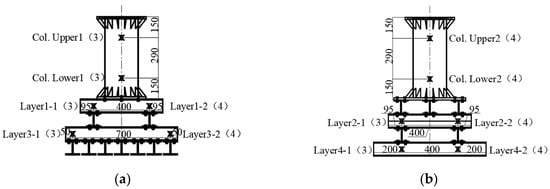

To investigate member deformation and bearing performance, strain measurement points were installed on the steel tube columns and I-beams prior to testing, as illustrated in Figure 4. On the steel tube columns, four strain gauges were arranged circumferentially at both the upper and lower sections. For each of the eight outermost I-beams in the assembly, two strain gauges were mounted at the center of the bolted connections. The strain gauges used were model BX120-5AA produced in Huangyan, Zhejiang, China, with a grid length × width of 5 mm × 3 mm. To ensure waterproofing and protection during testing, the strain gauges were coated with multiple layers of epoxy resin. During the experiment, all data were automatically collected and recorded using the DH3818Y static strain tester from Zhejiang Donghua Test in China.

Figure 4.

Strain Monitoring of Test Foundation: (a) Front View; (b) Left View.

To investigate the pressure variation between the base plate of the prefabricated assembled foundation and the overlying subsoil under uplift loading, earth pressure cells were installed at the interface between the base plate and the foundation soil, with their distribution illustrated in Figure 5. The earth pressure cells used were model BW27R resistance strain-type sensors manufactured by Changzhou Jintan Mingyang Geotechnical Engineering Instrument Co., Ltd. in Changzhou, Jiangsu Province, China. These sensors have a side-exit cable configuration, with dimensions of 27 mm in diameter and 10 mm in height, and a rated capacity of 200 kPa.

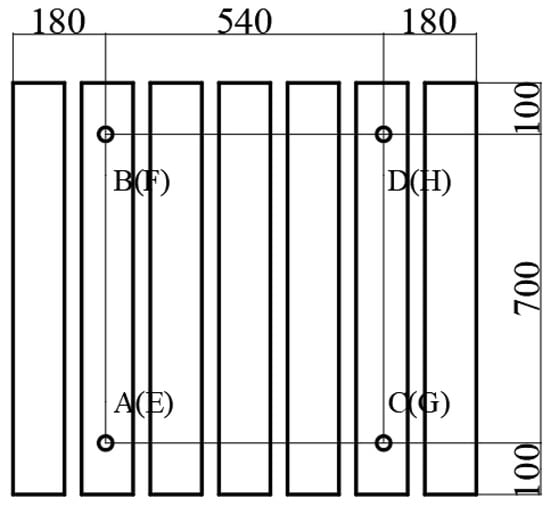

Figure 5.

Plan View of Earth Pressure Cell Layout at Base Plate.

To measure the vertical displacement at the top of the foundation under loading, two linear displacement transducers (manufactured by Donghua Test) were symmetrically mounted on the top flange plate of the foundation.

To monitor and control the applied load during testing, a YLR-3L compression load cell with a rated capacity of 100 kN, manufactured by Shanghai Zhendan Sensor Instrument Factory, Shanghai, China. was installed between the connection plate and the hydraulic jack.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Experimental Observations and Behavior

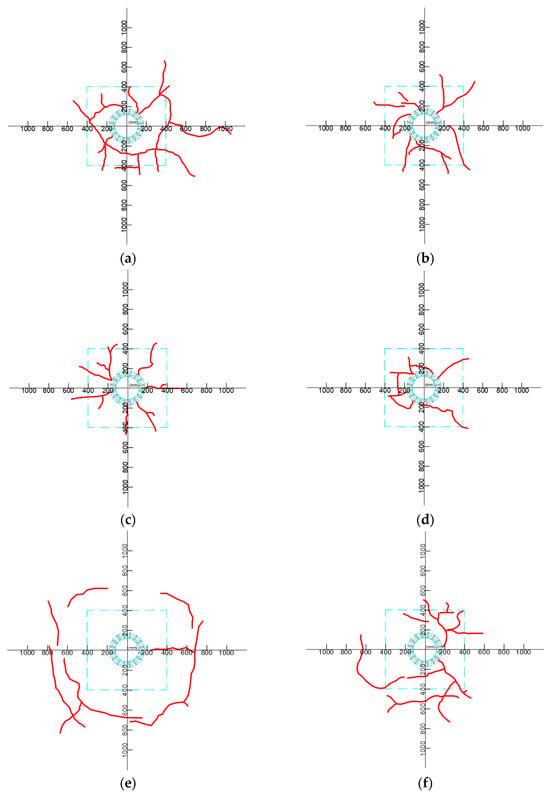

Figure 6 illustrates the crack patterns developed in the soil surrounding the foundation. In the figure, the blue lines represent the outline of the test foundation, while the red lines indicate the soil cracks. During the initial and intermediate stages of loading under all test conditions, radial cracks emanating from the foundation center were observed.

Figure 6.

Crack Pattern in Soil Surrounding Foundation: (a) UWC1; (b) UWC2; (c) UWC3; (d) UWC4; (e) UWC5; (f) UWC6; (g) UWC7; (h) UWC8.

As the uplift load increased, these cracks progressively propagated outward with increasing width. As the strength of silty clay primarily derives from interparticle cohesion, its tensile capacity is relatively low. Under uplift load, tensile stress concentration first occurs beneath the edge of the foundation base. When this stress exceeds the soil’s tensile strength, radial cracks initiate. These cracks predominantly propagate along tension zones, forming the observed pattern of radial cracking. The failure process is characterized by a coupling of tensile failure and localized shear failure. This radial cracking-dominated failure mode indicates that the load could not be effectively transferred to deeper soil layers through extensive shear planes. The failure zone is relatively shallow and localized, aligning with its characteristics of local shear or punching shear failure, which explains its relatively low ultimate bearing capacity.

The strength of weathered sand relies almost entirely on interparticle friction and interlocking. The uplift load induces shear displacement within the soil mass, thereby mobilizing its dilatancy effect. In this case, not only are radial shear cracks generated, but more importantly, circumferential tensile cracks form around the periphery of the shear zone due to soil arching and constrained dilatancy. The emergence of circumferential cracks signifies the development of a complete, highly developed inverted conical shear failure mass around the foundation. The volume of this failure mass is significantly larger than the failure zone in silty clay, meaning a greater mass of soil is mobilized to resist the uplift load. This directly explains why foundations in weathered sand exhibit higher ultimate bearing capacity and are characterized by a general shear failure mode.

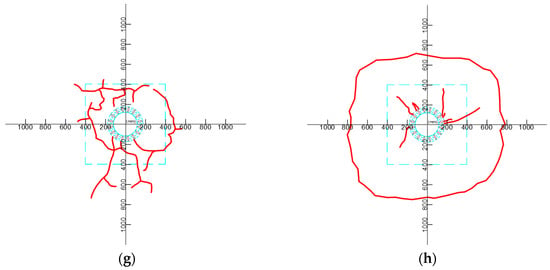

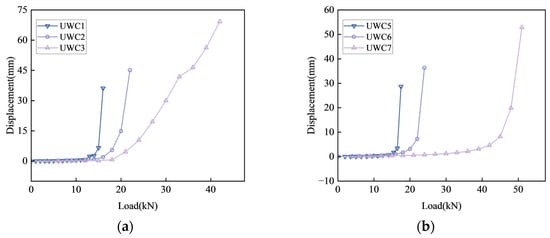

3.2. Load–Displacement Curve

Figure 7 presents the load–displacement curves of the test foundation under different backfill types and relative densities. The results clearly demonstrate that the ultimate uplift capacity and elastic stiffness under weathered sand conditions are significantly superior to those under silty clay conditions. Specifically, test case UWC7 with weathered sand backfill reached its failure stage at a load of 48 kN, whereas case UWC3 with silty clay backfill failed at 30 kN. During the elastic stage, the displacement increase in UWC7 was more gradual, indicating higher stiffness of the weathered sand backfill.

Figure 7.

Load–displacement Curves of Foundation under Different Backfill Types and Relative Densities.

When the relative density decreased from 0.9 to 0.7, the ultimate uplift capacity of the foundation in weathered sand dropped dramatically from 48 kN to 24 kN, representing a 50% reduction. The elastic stage nearly vanished, with an extremely short elastoplastic transition phase prior to failure, indicating a tendency toward brittle failure. This behavior occurs because the frictional interlocking in weathered sand relies entirely on dense particle contacts. At lower densities, larger inter-particle voids facilitate particle sliding and rearrangement under load, preventing the formation of a stable load-bearing skeleton and resulting in a sharp decline in capacity and increased deformation sensitivity.

For the silty clay backfill, the ultimate capacity decreased from 30 kN to 23 kN (a 23% reduction) as relative density dropped. The elastic stiffness substantially decreased, and the proportional limit load reduced from 15 kN to 10 kN, indicating an earlier transition to plastic deformation in the lower-density material. Mechanistically, the looser structure of the less compacted silty clay impedes effective transmission of cohesive forces between particles due to increased porosity. Under loading, this leads to localized shearing and pore expansion, causing simultaneous deterioration in both bearing capacity and stiffness.

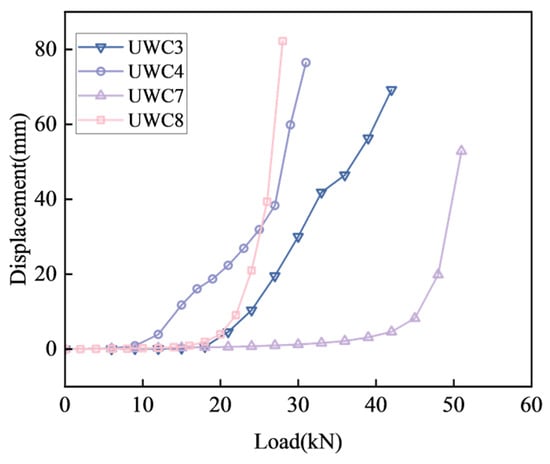

Figure 8 presents the load–displacement curves under different foundation embedment depths. As shown in Figure 8a, for silty clay backfill where cohesive-frictional synergy constitutes the primary load-bearing mechanism, the embedment depth influences the bearing performance through overburden confinement and the effective zone of side friction. During the elastic deformation stage, the initial segment of the curve exhibits an approximately linear increase, indicating that both the foundation and soil undergo elastic deformation, with the load being jointly resisted by their elastic responses. Beyond the proportional limit load, the curve slope gradually decreases, marking the transition to the elastoplastic stage. The characteristics of this stage vary significantly with embedment depth: test case UWC3 demonstrates ductile deformation features; UWC2 shows accelerated plastic development; while UWC1 exhibits a sharp reduction in curve slope, indicating an earlier transition to plasticity-dominated behavior. The ultimate uplift capacity reaches approximately 30 kN for UWC3, where post-peak displacement displays a gradual-to-abrupt increase trend, reflecting progressive failure from localized plasticity to general shear failure with deformation warning. In contrast, UWC2 achieves 20 kN ultimate capacity followed by rapid displacement escalation, demonstrating more sudden failure characteristics. UWC1 exhibits only 14 kN capacity with abrupt displacement development after peak load, indicating premature bearing capacity loss due to shear failure in shallow soil. When embedment depth increases from 0.5 m to 1.2 m, the ultimate uplift capacity of foundations in silty clay improves by approximately 114%, confirming that increasing embedment depth is an effective measure for enhancing the bearing capacity of foundations in cohesive soils.

Figure 8.

Load–displacement Curves of Foundation under Different Embedment Depths: (a) Silty Clay; (b) Weathered Sand.

Figure 8b reveals that for weathered sand backfill where particle interlocking and dilatancy effects dominate the load-bearing mechanism, the embedment depth governs the bearing performance by regulating overburden confinement intensity and the effective range of side friction. The initial linear segment of the curve during elastic deformation stage indicates elastic response of the foundation–sand system, where the load is resisted by interparticle frictional resistance and foundation elastic deformation. After exceeding the proportional limit load, the gradually decreasing slope signifies entry into the elastoplastic stage. The stage characteristics show remarkable variation with embedment depth: UWC7 displays pronounced ductile deformation; UWC6 exhibits accelerated plastic development, while UWC5 demonstrates rapid transition to failure stage. The ultimate capacity of UWC7 reaches 48 kN with progressive displacement development (gradual-to-abrupt increase) before failure, characteristic of ductile failure with clear deformation warning. UWC6 achieves about 22 kN capacity followed by steep displacement increase, showing shorter warning period. UWC5 attains merely 16.5 kN capacity with near-vertical displacement surge after peak load, approaching brittle failure with minimal warning. The 191% improvement in ultimate capacity when embedment depth increases from 0.5 m to 1.2 m demonstrates that increased embedment depth is a highly effective technical measure for enhancing bearing capacity in granular backfill.

Three key quantitative parameters extracted from the raw load–displacement curves are defined as follows: Initial Stiffness (Ki) is the slope (kN/mm) of the initial linear segment of the load–displacement curve. It characterizes the ability of the foundation-soil system to resist deformation in the elastic stage. Proportional Limit Load (Py) is determined using the double-tangent method. It corresponds to the load (kN) at the intersection point of the two tangents: one drawn to the initial straight-line segment and the other to the subsequent significantly curved portion of the curve. This parameter marks the critical point at which the soil begins to exhibit significant plastic deformation. Ductility Coefficient (μ) is the ratio of the ultimate displacement (δu, corresponding to the ultimate capacity) to the yield displacement (δy, corresponding to the proportional limit load), expressed as μ = δu/ δy. It provides a quantitative measure of the foundation’s ability to undergo plastic deformation before failure.

The average initial stiffness (Ki) of the foundation with weathered sand backfill was approximately 1.8 times that of the foundation with silty clay backfill. This is directly attributable to the dense interparticle friction and interlocking in the weathered sand, which provides higher initial resistance, whereas the cohesive-plastic nature of the silty clay results in greater compliance even during the initial loading stage.

When the relative density/degree of compaction increased from 0.7 to 0.9, the proportional limit load (δy) of the weathered sand foundation increased by approximately 90%, compared to an increase of only about 40% for the silty clay foundation. This indicates that increasing the density not only enhances the ultimate bearing capacity but also more significantly delays the onset of plastic deformation, with this effect being more pronounced in granular soils.

Our analysis revealed that as the embedment depth increased from 0.5 m to 1.2 m, the ductility coefficient (μ) of the weathered sand foundation increased from 2.5 to 4.1, while that of the silty clay foundation increased from 3.1 to 3.8. This quantitative result confirms that increasing the embedment depth, by enhancing lateral confinement, not only improves the bearing capacity but also significantly enhances the ductile performance of the foundation. This provides a longer warning period before failure, with the improvement in ductility being notably more significant for the foundation in weathered sand.

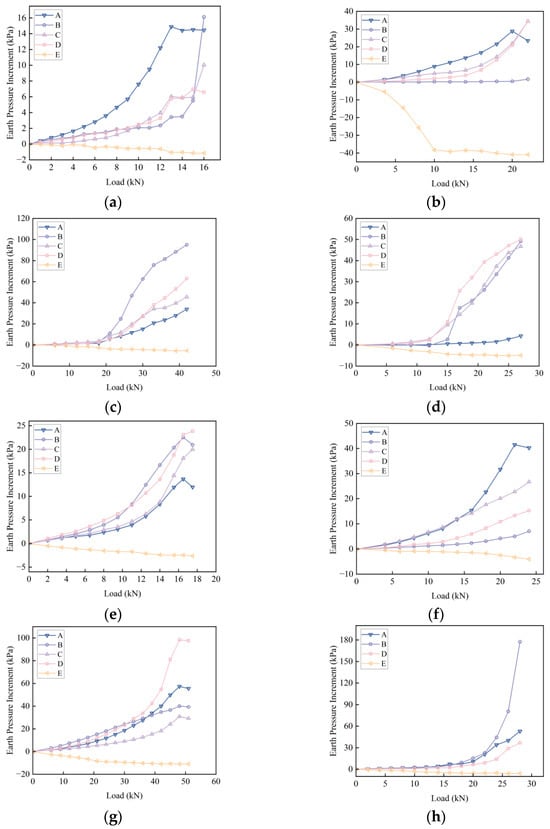

3.3. Contact Pressure Between the Base Plate and Subsoil

Figure 9 illustrates the variation patterns of earth pressure increments at different measurement points on the test foundation base plate during the loading process. As shown in Figure 9, under identical loading conditions, the magnitude of earth pressure increments may vary among different measurement points due to foundation placement position, backfill soil heterogeneity, and minor deviations in load application. Nevertheless, all measurement points exhibit identical trends, showing progressive increase with external load. Since the E# earth pressure cell is positioned beneath the foundation base plate, it primarily sustains the self-weight of the overlying foundation and soil mass under uplift loading. Consequently, the earth pressure at the E# measurement point initially demonstrates a minor decrease before stabilizing throughout the test.

Figure 9.

Load-Dependent Earth Pressure Increment Curves at Base Plate: (a) UWC1; (b) UWC2; (c) UWC3; (d) UWC4; (e) UWC5; (f) UWC6; (g) UWC7; (h) UWC8.

3.4. Analysis of Ultimate Uplift Capacity

The ultimate vertical uplift capacity of the foundation can be determined in accordance with the method specified in Article F.2.9, Appendix F of the standard*DL/T 5219-2023: Design Code for Foundations of Overhead Transmission Lines* [28]. The specific determination methods are described as follows: Based on the characteristics of uplift displacement versus load: For a load–displacement (T-δ) curve exhibiting a sharp transition, the load corresponding to the onset of the sharp transition may be taken as the ultimate value; Based on the characteristics of uplift displacement versus time: The load value immediately preceding the point where the slope of the displacement-log time (δ-lg t) curve significantly steepens, or where the tail of the curve shows distinct curvature, may be taken as the ultimate value; For a gradual T-δ curve: A comprehensive determination shall be made using a combination of methods, such as the mathematical model method, the specified displacement method, and the graphical method; For cases not conforming to the above: The load value immediately preceding the maximum applied load may be taken as the ultimate value. The characteristic value of the vertical uplift capacity is taken as half of the ultimate value (i.e., multiplied by a factor of 0.5),with reference to the uplift capacity formula for spread foundations specified in the industry standard “Design Code for Foundation of Overhead Transmission Line” (DL/T 5219-2023) [28].

In Equation (1):

Tk is the characteristic value of the uplift force acting on the foundation (kN);

γE is the horizontal force influence factor;

γs is the weighted average unit weight of the soil above the foundation base (kN/m3);

γθ1 is the influence factor for the slope angle at the top plane of the foundation base;

Vt is the volume of soil and foundation within the depth ht (m3);

ht is the uplift embedment depth of the foundation base (m);

hc is the critical embedment depth for foundation uplift (m);

ΔVt is the incremental volume accounting for the influence of adjacent foundations (m3);

V0 is the volume of the foundation itself within the depth ht (m3);

K1, K2are safety factors for foundation uplift;

Gf is the self-weight of the foundation (kN).

The calculated uplift capacity of the assembled foundation was obtained using Equation (1). The back-calculated uplift angle is derived from the ultimate uplift capacity based on the limit equilibrium theory, representing the inclination angle of the shear failure surface between the foundation and the surrounding soil. Its physical significance lies in characterizing the inclination of the shear failure surface under uplift loading, reflecting the load transfer efficiency and failure mode within the soil. The uplift angles were determined by back-calculation using the ultimate bearing capacity data, as summarized in Table 3. It can be observed that the code’s bearing capacity formula yields conservative results for backfill with a high degree of compaction. For backfill with a low degree of compaction, the calculated value from the formula necessitates the application of a reduction factor.

Table 3.

Calculated Ultimate Uplift Capacity and Back-Calculated Uplift Angle of Test Foundation.

For the silty clay backfill, the uplift angle decreases significantly and continuously with increasing embedment depth, with the rate of reduction slowing at greater depths. This behavior occurs because deeper embedment enhances the overburden confinement, causing the uplift load to transfer more vertically and compressing the inclination of the shear failure surface. In contrast, shallow embedment provides insufficient confinement, allowing the failure surface to extend at a wider angle. In the weathered sand backfill, the uplift angle decreases sharply as the embedment depth increases from 0.5 m to 0.85 m, consistent with the trend observed in silty clay. However, when the embedment depth further increases to 1.2 m, the uplift angle slightly recovers. This phenomenon is attributed to the dilatancy effect of the weathered sand. Under deep embedment, the combined effect of overburden pressure and side resistance promotes tighter particle packing. During uplift, dilatancy induces a significant increase in normal stress between particles, indirectly expanding the inclination of the failure surface and reflecting the coupled effect of embedment depth, dilatancy, and uplift angle.

In the silty clay backfill, the uplift angle is slightly larger under higher relative density. This is because increased density enhances particle contact, improving the synergistic effect of cohesion and internal friction, which allows the failure surface to propagate over a wider area during uplift. For the weathered sand backfill, the uplift angle is significantly larger at higher relative density, and its reduction with decreasing density is much more pronounced than in silty clay. This is attributed to the fact that the bearing capacity of weathered sand primarily relies on particle interlocking and friction. A decrease in density leads to a substantial increase in interparticle voids and a sharp reduction in interlocking effect, hindering load diffusion and significantly compressing the failure surface angle. In contrast, the presence of cohesion in silty clay mitigates the influence of density on the failure of surface morphology, resulting in a relatively moderate effect.

Under identical embedment depth and relative density conditions, the uplift angle of weathered sand is slightly larger than that of silty clay. This difference stems from their distinct unit weights and mechanical mechanisms: weathered sand has a higher unit weight and relies primarily on particle interlocking and friction, while silty clay, with its lower unit weight, depends on the synergy between cohesion and friction. The limited contribution of cohesion to the propagation of the failure surface results in a relatively smaller uplift angle.

The uplift angle is essentially a macroscopic representation of the inclination of the soil shear failure surface. Its magnitude is directly governed by the soil’s peak strength and dilatancy/contractancy characteristics, which are, in turn, strictly controlled by the degree of compaction and confining pressure (embedment depth).

In weathered sand, a high degree of compaction significantly enhances interparticle interlocking and generates a strong dilatancy effect during shear. This dilation consumes more energy and requires greater shear displacement to develop a continuous failure surface, resulting in a flatter (lower angle) failure plane.

In silty clay, whose strength is primarily controlled by cohesion, shearing predominantly exhibits contractancy. Although increasing the degree of compaction improves particle-to-particle contact and mobilizes greater cohesion, it cannot induce dilatancy akin to that in sandy soils. The slight increase in the uplift angle of silty clay with higher degree of compaction stems from the limited improvement in cohesion and internal friction angle. The fundamental deformation mechanism, dominated by contractancy, remains unchanged.

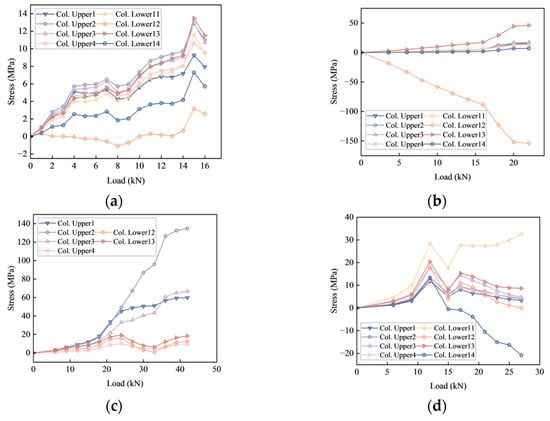

3.5. Stress Analysis of the Foundation

During loading, the test foundation interacts with the surrounding soil, resulting in complex stress conditions within its structural components. Experimental observations confirmed that all components remained in the linear elastic range under the applied loads. The stress in each member was calculated from the measured strain values using Equation (2):

In Equation (2):

σ denotes the stress in Q355 steel (MPa);

E represents the modulus of elasticity of Q355 steel, taken as E = 210 GPa;

ε is the measured strain value of Q355 steel.

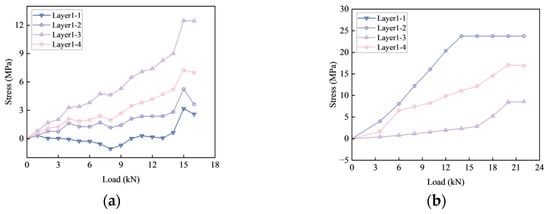

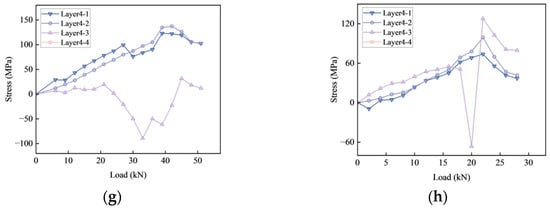

As shown in Figure 10, the steel tube columns predominantly remain in a state of linear elastic tension under uplift loading. In most subplots, the stress at the upper measurement points exhibits more pronounced increase with loading, reaching a maximum of 160 MPa, while the stress growth at lower measurement points remains relatively gradual. Some test conditions even show negative stress variations, potentially indicative of compressive stress dominance. The upward movement tendency of the foundation generates side friction between the steel tube columns and surrounding soil, resulting in reduced tensile stress with increasing depth. At each measurement point, the stress increases with applied load until sudden stress reduction occurs upon soil failure. The progressive mobilization of side friction leads to a slightly increasing stress gradient along the depth.

Figure 10.

Load-Stress Curve of Steel Tube Column: (a) UWC1; (b) UWC2; (c) UWC3; (d) UWC4; (e) UWC5; (f) UWC6; (g) UWC7; (h) UWC8.

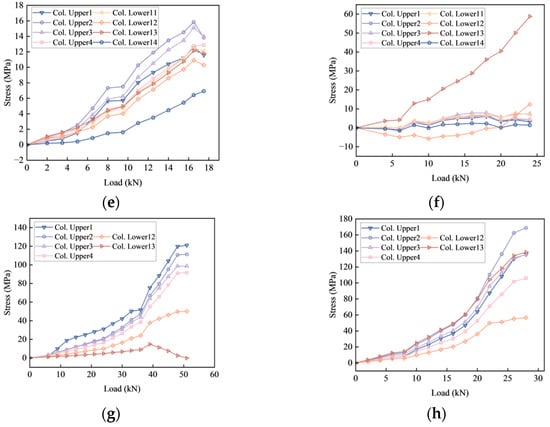

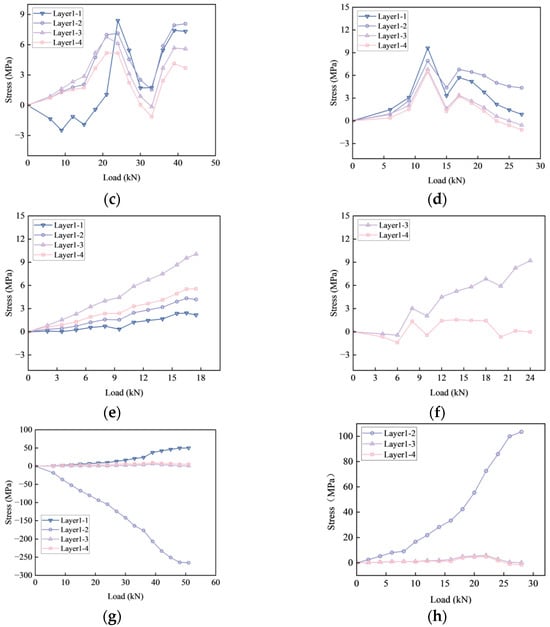

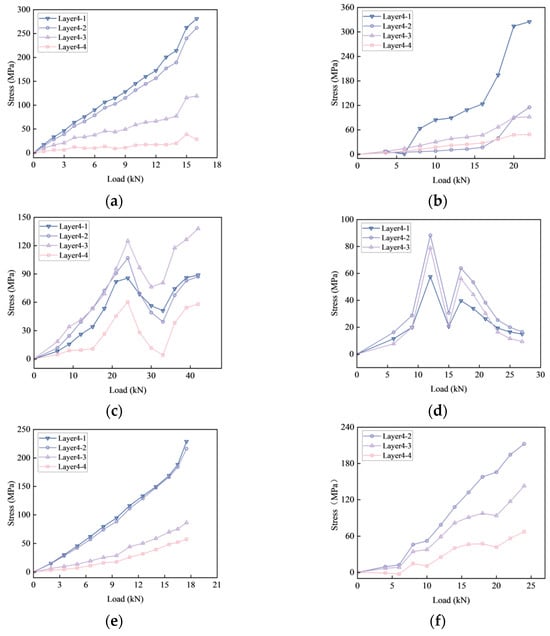

Figure 11 shows the stress variation curves at different measurement points on the first-layer I-beams during loading. The stresses at all measurement points increased nearly linearly with the applied load, indicating a stable positive correlation between the structural response and loading, and demonstrating that the first-layer I-beams remained primarily in a state of linear elastic tension under uplift conditions. These I-beams were arranged in a three-beam configuration, with the maximum recorded stress reaching 50 MPa, indicating relatively low stress levels. The stress at each measurement point consistently increased with the applied load.

Figure 11.

Load-Stress Curve of First-Layer I-Beam: (a) UWC1; (b) UWC2; (c) UWC3; (d) UWC4; (e) UWC5; (f) UWC6; (g) UWC7; (h) UWC8.

In test cases UWC3 and UWC4, certain stress values peaked within specific load ranges before decreasing, reflecting stress redistribution in these components during loading, possibly indicating a transition in load-bearing mechanism. In most test configurations, the stress increase at measurement point Layer1-1 was substantially greater than at other locations, suggesting potential eccentric loading during force application, which made the I-beam at Layer1-1 the primary load-bearing member carrying disproportionately higher stresses. Stress growth at other measurement points was generally gradual, with virtually no significant stress increase observed at points Layer1-2 to Layer1-4 in UWC8, confirming that these regions carried minimal load.

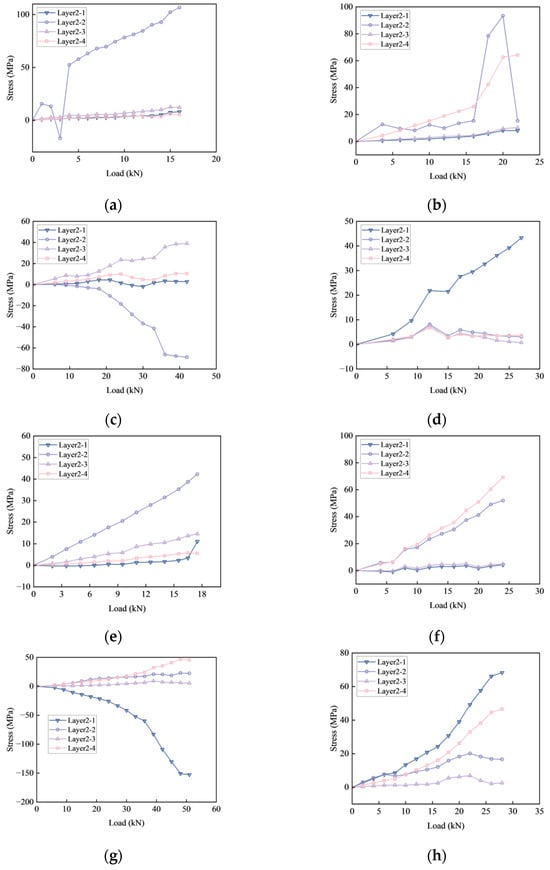

Figure 12 presents the stress variation curves at different measurement points on the second-layer I-beams during the loading process. The stress at all measurement points increased nearly linearly with the applied load, indicating a stable positive correlation between the structural response and the loading. The stress at each measurement point progressively increased with the applied load. Under uplift loading, the second-layer I-beams, arranged in a two-beam configuration, remained primarily in a state of linear elastic tension, with the maximum recorded stress reaching 100 MPa, indicating relatively high stress levels.

Figure 12.

Load-Stress Curve of Second-Layer I-Beam: (a) UWC1; (b) UWC2; (c) UWC3; (d) UWC4; (e) UWC5; (f) UWC6; (g) UWC7; (h) UWC8.

Negative stress values were observed in test cases UWC3 and UWC7, demonstrating that the corresponding measurement points were subjected to compression, with the compressive stress following specific patterns during loading. In most cases, the stress increase at measurement point Layer2-1 substantially exceeded that at other points, while other measurement points maintained low stress levels. This pattern confirms that the I-beam at location Layer2-1 served as the primary load-bearing component under specific test conditions. Analysis suggests potential eccentricity issues during the load application process.

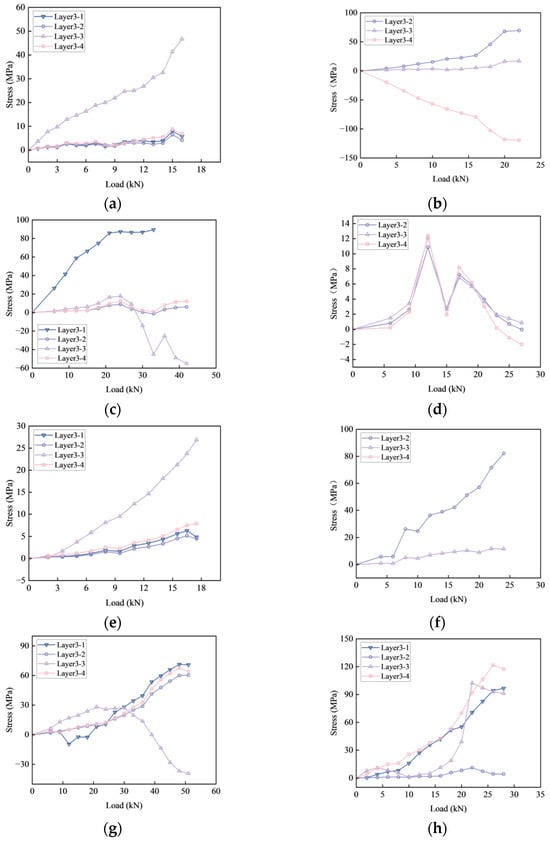

Figure 13 shows the stress variation curves at different measurement points on the third-layer I-beams during the loading process. The stress at all measurement points increased almost linearly with the applied load, indicating a stable positive correlation between the structural response and loading. The stress at each measurement point progressively increased with the applied load. Under uplift loading conditions, the third-layer I-beams, arranged in a two-beam configuration, remained primarily in a state of linear elastic tension, with the maximum recorded stress reaching 120 MPa, indicating relatively high stress levels.

Figure 13.

Load-Stress Curve of Third-Layer I-Beam: (a) UWC1; (b) UWC2; (c) UWC3; (d) UWC4; (e) UWC5; (f) UWC6; (g) UWC7; (h) UWC8.

In test case UWC3 at measurement point Layer3-1 and test case UWC4, the stress curves reached peak values followed by subsequent decrease, reflecting stress redistribution in these components during loading, potentially resulting from plastic failure development in the foundation soil. Negative stress values were observed at measurement points Layer3-2 and Layer3-4 in test case UWC2, indicating that these locations were subjected to compressive stress. In most test conditions, the stress increase at measurement point Layer3-1 substantially exceeded the stress growth at other measurement points, demonstrating that the I-beam at location Layer3-1 served as the primary load-bearing member under specific test conditions. Analysis suggests potential eccentric loading issues during the load application process.

Figure 14 presents the stress variation curves at different measurement points on the fourth-layer I-beams during the loading process. The stress at all measurement points increased either nearly linearly or with accelerated growth with the applied load, demonstrating a stable positive correlation between the structural response and loading. The stress at each measurement point progressively increased with the applied load. Under uplift loading, the fourth-layer I-beams, arranged in a seven-beam configuration, remained entirely in a state of linear elastic tension. These beams primarily resisted the backfill soil pressure during loading, with the maximum recorded stress reaching 250 MPa, representing the highest stress level observed in the test program.

Figure 14.

Load-Stress Curve of Fourth-Layer I-Beam: (a) UWC1; (b) UWC2; (c) UWC3; (d) UWC4; (e) UWC5; (f) UWC6; (g) UWC7; (h) UWC8.

In test cases UWC3, UWC4, UWC7, and UWC8, certain stress curves reached peak values followed by subsequent decrease, indicating stress redistribution in these components during loading, potentially attributable to the development of plastic failure in the foundation soil. Negative stress values were observed in test case UWC8, indicating the presence of compressive stresses. In most test conditions, the stress increase at measurement point Layer4-1 substantially exceeded the stress growth at other measurement points, confirming that the I-beam at location Layer4-1 served as the primary load-bearing member under specific test conditions. Analysis suggests potential eccentric loading issues during the load application process.

Based on a comprehensive analysis of strain gauge data, structural configuration, and the installation process, the causes of load eccentricity were systematically analyzed and are primarily attributed to the following two aspects.

Initial Eccentricity—Originating from inevitable minor imperfections in construction and installation. Although the foundation is macroscopically symmetrical, the arrangement of members that are not perfectly axisymmetric leads to a slight deviation between the actual structural stiffness center and the geometric center. We candidly acknowledge that during the complex process of field assembly, despite numerous measures taken to ensure accuracy, the final positioning of the foundation, the degree of compaction of the backfill soil, and minor variations in the bolt tightening sequence and preload force between the I-beams and connection plates at various levels inevitably introduce initial installation eccentricity.

Eccentricity Amplification under Load—Originating from the non-uniformity of soil-structure interaction, which is the more critical factor causing certain members to become the primary load-bearing components. The degree of compaction of the backfill soil around the foundation is not absolutely uniform at the micro-scale, resulting in an inherently uneven distribution of soil reaction forces beneath the foundation base and along its sides. This non-uniform soil constraint dynamically guides the load path during loading, causing it to concentrate more on the members on the side opposite to the stronger soil constraint, thereby amplifying the imbalance caused by the initial eccentricity. Data from earth pressure cells confirm that under certain working conditions, observable differences indeed exist in the increments of earth pressure at different locations under the foundation base, providing direct evidence for the uneven soil reaction.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

4.1. Conclusions

Through model testing, this study presents a comparative analysis of the bearing characteristics, deformation behavior, and failure mechanisms of silty clay and weathered sand under different relative densities and embedment depths. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The silty clay backfill primarily exhibited shear failure mode characterized by radial crack propagation, while the weathered sand backfill showed overall tensile failure mode, manifested by noticeable circumferential cracks in addition to radial cracks. The uplift angle of weathered sand demonstrated higher sensitivity to variations in relative density, whereas that of silty clay decreased continuously with increasing embedment depth.

(2) Under identical conditions, the foundation with weathered sand backfill demonstrated significantly superior performance in ultimate uplift capacity, initial stiffness, and ductility compared to that with silty clay backfill. At an embedment depth of 1.2 m with high relative density, the ultimate load of the foundation in weathered sand was 33.3% higher than that in silty clay. This is primarily attributed to the mechanical mechanism of weathered sand, which is dominated by particle interlocking friction and dilatancy effects, enabling the formation of an efficient rigid granular skeleton for load transfer. In contrast, the bearing performance of silty clay is governed by the synergistic interaction between cohesion and internal friction angle.

(3) The uplift capacity of the foundation increased significantly with higher backfill density, with this enhancement being more pronounced in weathered sand. When the relative density increased from 0.7 to 0.9, the ultimate capacity of the foundation in weathered sand increased by 100.0%, while that in silty clay increased by 30.4%.

(4) Under deep embedment conditions, the strong confinement provided by the overlying soil not only enhanced the side friction resistance but also effectively suppressed the dilatancy-induced failure tendency in weathered sand, resulting in higher stiffness and favorable ductile failure characteristics. When the embedment depth increased from 0.5 m to 1.2 m, the bearing capacity of the foundation in weathered sand increased by 191%, compared to a 114% increase in silty clay.

4.2. Future Work

This study has several main limitations, which also outline directions for future research.

(1) The conclusions of this study are derived from laboratory reduced-scale model tests (1:3). Although the reliability of the models has been verified through various means, caution is still required when extrapolating the results directly to full-scale engineering applications. The potential influences of full-scale factors, such as thein-situ stress level of the soil, scale effects, and construction techniques, must be considered. To establish universal design formulas, future work necessitates full-scale prototype testing and numerical simulation to further validate the reliability of the findings.

(2) The calibration accuracy of sensors, the microscopic spatial variability of soil parameters, and the interpretive discretion involved in determining characteristic points from load–displacement curves and earth pressure data can all impact the experimental results. The uplift angle is a derived parameter back-calculated from the ultimate bearing capacity, making it cumulatively sensitive to all the aforementioned sources of uncertainty. The uplift angle values provided in this paper should therefore be regarded as characteristic values with a reasonable range of variation, rather than as absolute, precise constants. Further determination of the uplift angle requires extensive full-scale prototype testing and numerical simulation.

(3) The tests primarily focused on the behavior of weathered sand and silty clay under short-term static loading. The applicability of the research findings to other soil types requires further validation. Furthermore, this study did not consider the effects of cyclic loading, long-term creep, wet-dry cycles, or freeze–thaw cycles on the long-term performance of the foundation, all of which can be critically important in actual temporary engineering projects. Future research will be extended to investigate the bearing behavior and design methods of the foundation under combined vertical and horizontal loading. This includes examining the accumulation of deformation and the degradation of stiffness under cyclic loads (e.g., wind loads), and exploring the impact of environmental actions (e.g., groundwater fluctuations, freeze–thaw cycles, and soil salinity) on the interface characteristics between the foundation and backfill, as well as on the long-term bearing capacity.

Author Contributions

Q.M.: Methodology, Project administration, Writing—review and editing; H.N.: Formal analysis, Data curation; K.Y.: Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft; S.L.: Investigation; M.K.: Supervision, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Heilongjiang Beixing Electric Power Co., Ltd.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Qingyu Meng and Shufeng Long were employed by the company State Grid Heilongjiang Electric Power Co., Ltd., Daqing Power Supply Company. Author Hanyu Ning was employed by the company Materials Company of State Grid Heilongjiang Electric Power Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Prasad Rao, N.; Bala Gopal, R.; Rokade, R.; Mohan, S. Analytical and experimental studies on 400 and 132 kV steel transmission poles. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 18, 1018–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Energy Engineering Group Tianjin Electric Power Design Institute Co., Ltd.; Tianjin Jindian Power Supply Design Institute Co., Ltd. A Reusable Temporary Transition Steel Tube Tower. Patent CN202311236584.8, 19 December 2023. Available online: https://cprs.patentstar.com.cn/Search/Detail?ANE=5ADA7BGA9ICD8CDA9HGF9FDA7AFA9FCBEHIA9EDDEGHA9CGD (accessed on 1 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Hu, X.; Xi, X.; Zheng, Y.; Xiang, Z.; Zhang, H. Study on bearing capacity of Mortise-tenon and joint-flange concrete assembled foundation of transmission line under combined load. PLoS ONE 2023, 6, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, W.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Hu, T.; Kolos, A. Frost jacking characteristics of prefabricated cone cylindrical tower foundation in cold regions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2023, 211, 103847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Miao, X.; Chen, Z. Research on grouting connection technology in PHC pipe piles and bearing platform integration. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 106, 112633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Gao, F.L.; Liu, G.S.; Gao, B.; Xiao, F.; Zeng, E.X. Full-scale test study on metal assembled foundations in aeolian sand foundation. Rock Soil Mech. 2021, 42, 3328–3334. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sui, W. Determination of mechanical and microstructure properties of paste backfills to avoid to overburden failure. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 388, 135926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Vanapalli, S.K. Failure envelops for foundation subjected to inclined and eccentric loading considering steady state and transient flow conditions in unsaturated soils. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 157, 105315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Tho, K.; Leung, C.; Chow, Y. Influence of overburden pressure and soil rigidity on uplift behavior of square plate anchor in uniform clay. Comput. Geotech. 2013, 52, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickin, E.; Laman, M. Uplift response of strip anchors in cohesionless soil. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2006, 38, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Pandit, B.; Babu, G. Uplift capacity of horizontal anchor plate in geocell reinforced sand. Geotext. Geomembr. 2019, 47, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niroumand, H.; Kassim, K.; Nazir, R. The influence of soil reinforcement on the uplift response of symmetrical anchor plate embedded in sand. Measurement 2013, 46, 2608–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Song, W.; Hao, W.; Guo, F.; Yang, Y.; Kang, M.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y. Study on the Bearing Performance of Pole-Assembled Inclined Pile Foundation Under Downward Pressure-Horizontal Loads. Buildings 2025, 15, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, C.; Yang, Y.; Niu, K.; Xu, W.; Wang, D. Anti-Overturning Performance of Prefabricated Foundations for Distribution Line Poles. Buildings 2025, 15, 2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Gao, Q.; Duan, Y. Mechanical performance and design theory of a novel prefabricated internal support fixed end for foundation pits. Structures 2025, 76, 108972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Guo, Y.; Hao, H.; Zhang, L. Experimental study on the mechanical characteristics of prefabricated dense ribs foundation for onshore wind turbines. Structures 2025, 73, 108273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.S.; Zhang, C.C.; Zhao, Q.S.; Xu, G.F.; Chen, C.; Tian, S.K. Study on compressive bearing characteristics of metal assembled foundations in aeolian sand area. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2022, 44, 85–91. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.Y.; Feng, H.; Zeng, E.X.; Li, Q.; Xiao, F.; Zhang, C.C. Study on uplift bearing capacity of metal assembled foundations for transmission lines in desert area. Build. Struct. 2021, 51, 1598–1603. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=dzw7IdLhHkGyzkQ5cHXExCsWKuIZfDNxVZcBUDYEI3mO46trCzjUvEOi3ZtpTnMbk5EkBBKkYXTr0KC7qrSfhbBIlFfCYP9nvujxRo7Xn1qqfCBPXSUSRQLst5HdE-cdeJHzSp1L6uyDvUTjAzUZQzPySTAopeKju2Lg3tXIHj4AUheCpfjz3Q==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Qian, Z.; Lu, X.; Ding, S. Experimental study of assembly foundation for transmission line tower in Taklimakan desert. Yantu Lixue Rock Soil Mech. 2011, 32, 2359–2364. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J. Numerical Analysis of Pile-Soil Interaction of Tower Platform of Transmission Line Engineering. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Wireless Communications and Smart Grid (ICWCSG), Hangzhou, China, 13–15 August 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Huang, C.Q. Common engineering problems and treatment methods for backfill soil in fat trenches. Geotech. Eng. Tech. 2019, 33, 84–88. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.; Lin, T.; Molla, A.; Lin, C. Advanced risk management strategies for safety enhancement in temporary building construction works. J. Saf. Res. 2025, 95, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Kong, G.; Qin, H.; Sun, G.; Xu, X. Field Tests on the Installation Effect and Bearing Capacity of Inclined Helical Piles in Silty Clay. Int. J. Geomech. 2025, 25, 04025248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Zhou, J. Shear failure performance and evolutionary process of cemented deposit material within matrix scale under cementation-friction interaction view. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 494, 143366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, H.; Mohamed, Z.; Abdul Kudus, S. Deformation behaviour, crack initiation and crack damage of weathered composite sandstone-shale by using the ultrasonic wave and the acoustic emission under uniaxial compressive stress. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2023, 107, 105497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50123-2019; The Ministry of Housing and Urban Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China Standard for Geotechnical Testing Methods. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

- GB 50007-2011; Code for Design of Building Foundation. Code of China: Beijing, China, 2011. (In Chinese)

- DL/T 5219-2023; Design Code for Foundation of Overhead Transmission Line. National Energy Administration: Beijing, China, 2023. (In Chinese)

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).