Abstract

Settlements are the fundamental structural components of the Northwest and Southwest Routes, which were important defensive sectors of the Jin Dynasty’s Great Wall defense system. Under the Jurchen rule, these settlements function as special conduits for investigating border defense tactics. However, historical document analysis is the main method used in present study on the Northwest and Southwest Roads, and comprehensive quantitative empirical data about the geographical organization of settlements are absent. As a result, research on the unique defense tactics of the Jin Dynasty is still not fully understood. This study establishes a dual “historical-spatial” analytical paradigm by examining settlement remnants from the Northwest and Southwest Roads in modern-day Inner Mongolia. In order to thoroughly examine defensive tactics within their distinct historical and geographical settings, it clarifies the building procedures, spatial distribution, and site selection features of these settlements using a combination of qualitative and quantitative methodologies. The results show: (1) The Southwest Road defense zone was continuously reinforced, whereas the Northwest Road defense zone steadily shrank inward from the standpoint of settlement construction. This illustrates how the Jin Dynasty’s macro-level defensive strategy changed from “military deterrence” to “tactical defense”. (2) In terms of military administration systems, ethnic composition differences and settlement defense functions were the main factors influencing the settlement patterns formed in the Northwest and Southwest Roads. (3) In terms of spatial distribution and site selection features, the Zhaotaosi settlements functioned as the core settlements integrating “command-troop garrison-combat operations,” in contrast to the conventional method of using the highest-level settlement as the rear command center.

1. Introduction

To maintain stability in the northern frontier, the Jin rulers established the Jin Great Wall defense system. They retained the Liao Dynasty’s Zhaotaosi system (an institution used by the Jin Dynasty to manage the northern frontier) and divided the Jin Great Wall into three regions for governance: the Northeast Route, the Northwest Route, and the Southwest Route. Geographically, the Northwest and Southwest Routes, as former Liao territories, held critical strategic positions bordering Mongol tribes to the north and the Western Xia to the west. Beyond their unique ethnic composition, their management and defensive deployments were vital for safeguarding northern territories. Chronologically, these routes were constructed later than the Northeast Route. Their fortifications, construction models, and spatial planning were more refined, better reflecting the overarching philosophy of the Jin Dynasty’s border defense system.

Settlements, which represent the cultural traits of human society, are an inevitable byproduct of human adaptation to natural conditions and the lengthy process of social development. Settlements developed defensive features, such as “integrated habitation and defense,” which combines residential and defensive functions, as civilizations became more sophisticated and impacted by humanity’s innate protective impulses [1]. The Jin Dynasty, an ethnic minority government founded by the Jurchen people, was characterized by a way of life that involved “hunting with bows during peacetime and serving as troops during wartime”. As a result, the main defense units were settlements.

From discrete historical studies [2,3,4,5] to systematic studies [6] covering “settlement characteristics [7,8], spatial distribution [9,10], garrison locations [11], and the macro-level site selection logic of military outposts [12]”, research on the defense system of the Jin Dynasty Great Wall has progressed. The majority of study treats towns along the Northwest and Southwest Routes of the Jin Dynasty as parts of the defensive system, and specialized studies on these settlements are still rare.

Overviews of their topographical surroundings [13,14], morphological traits [15,16], and spatial distribution [17,18] are available in the literature. In contrast to previous studies on the external environment and spatial arrangement of settlements during the Tang [19], Song [20], Ming [21,22,23,24,25,26] and Qing [27] dynasties, the use of multiple approaches and multifaceted viewpoints has become a common practice in academic circles.

However, thorough quantitative empirical information about settlement spatial arrangements is lacking in studies on the Northwest and Southwest Frontiers. Additionally, they do not thoroughly examine the special features of these two frontier defense zones that support their settlements, which leads to an inadequate understanding of the unique defensive tactics of the Jin Dynasty.

Therefore, the main research topic of this paper is settlements along the Northwest and Southwest Roads. It creates a dual-perspective research framework incorporating “historical–spatial” dimensions by utilizing a mixed qualitative and quantitative research approach. It provides contextual assistance for spatial settlement studies by elucidating the management systems and distinctive features of the defense zones along these routes. It is based on historical study. Concurrently, it explores the development of military defense tactics throughout the Jin Dynasty via the perspective of settlement building procedures. By contrasting the spatial distribution and site selection characteristics of settlements in both circuits, the spatial perspective clarifies the hierarchical aspects of settlements limited by historical contexts. Ultimately, it shows that the Jin Dynasty’s general defense strategy, settlement hierarchy and defensive functions, and settlement spatial and site selection features all had a major impact on the defense methods of the Northwest and Southwest Circuits. As a result, defense plans adapted to local circumstances were developed. By offering a theoretical underpinning for the successful preservation, display, and application of Jin-era frontier defenses, this study complements fundamental research on the Northwest and Southwest Frontiers of the Jin Dynasty.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

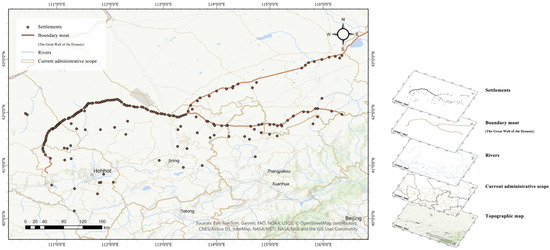

Two vital defensive sectors of the Jin Dynasty’s border defense system were the Northwest Road and the Southwest Road, which were vital routes for invaders aiming to reach the Jin heartland. The Jin Great Wall defense system mostly focused on settlements as its primary combat units, in contrast to the Ming Great Wall defense system, which used hilly terrain and constructed walls to establish complete barriers. However, some communities lack both written descriptions and physical archeological remains because of time and the lack of historical records, which makes fair evaluation hard. Thus, this study compares physical remains, gathers pertinent historical documents, and carries out field research using archaeological data from the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology. In total, 62 settlements along the Northwest Road and 139 along the Southwest Road were selected as the main subjects of analysis, based on the archaeological data supplied by the Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, by comparing tangible relics, historical records, and on-the-spot investigation. For a thorough analysis, combined with the northwest and southwest road boundary moat. (The Great Wall of the Jin Dynasty is referred to as “The Boundary Moat of the Jin Dynasty” in academic circles since early academics ignored the ground wall in favor of moats [2] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Northwest Road and Southwest Road Defense Zones and Fortifications.

The Northwest and Southwest Defense Zones were mainly situated within the administrative jurisdiction of the Jin Dynasty’s Xijing Road, as may be seen by consulting ‘The Jin Dynasty map in the Historical Atlas of China’ [28]. These regions mostly included what is now northern Hebei Province, northern Shanxi Province, and the southwest portion of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. The topography, which had an average elevation of more than 1000 m, was mainly moderate and consisted of grassland plateaus, low ranges and hills, and sandy landforms. There were no natural impediments in the shape of high slopes or towering mountains.

2.2. Data Sources

In order to examine the hierarchical structure and spatial distribution features of settlements, this study mainly uses the geospatial data and attributes of settlement sites. Field survey data from the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology is the source of settlement traits and geospatial data, which are then augmented by pertinent documents and discoveries from the body of existent ancient literature.

Administrative boundary data for the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and Hebei Province were obtained from the National Geomatics Center of China (http://www.ngcc.cn/). GDEMV2 30M resolution digital elevation data and river data originate from the Geospatial Data Cloud (https://www.gscloud.cn/), while river-related vector data comes from the National Earth System Science Data Center (https://www.geodata.cn/).

2.3. Research Methods

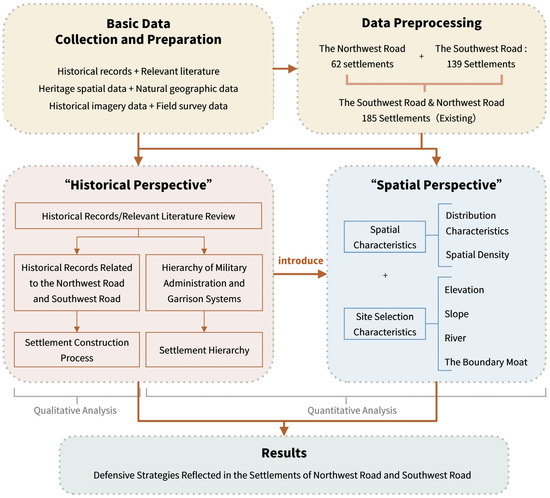

Both qualitative and quantitative research methods are used in this study. While quantitative analysis of settlement spatial distribution and site selection features is carried out using ArcGIS Pro 3.3.2 software, a qualitative analysis of settlement development processes based on historical documents is also conducted. The study thoroughly examines the defense tactics used by communities along the Jin Dynasty’s Northwestern and Southwestern Roads (Figure 2). The specific analysis methods are as follows:

Figure 2.

Technology road-map.

2.3.1. Nearest Neighbor Index

The nearest neighbor index is a geographic metric that quantifies the spatial proximity of point features within a geographic space. It effectively reflects the spatial distribution characteristics of point elements and is used to identify the spatial distribution patterns of settlements at various levels along the Northwest Road and Southwest Road.

The calculation formula is as follows:

where is the number of points; A is the area of the region; D is the density of points; R is the nearest neighbor index; is the average of the distance between the closest points; and is the theoretical nearest neighbor distance. When R < 1, the NIH sites tend to be clustered; when R > 1, the NIH sites are uniformly distributed; and when R = 1, the NIH sites are randomly distributed [29].

2.3.2. Kernel Density Estimation Method

The Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) is a non-parametric estimation method for analyzing spatial points, used to estimate the density of settlement points. It reflects the concentration level and spatial clustering of feature points [30,31]. This study employs kernel density analysis to visualize settlement concentration.

The calculation formula is as follows:

The formula, the kernel density was estimated as the probability that the density function is valid at point , where is the kernel function, is the search radius, which must be greater than 0, and the distance (km) between the estimated point and the point of interest is considered [32].

2.3.3. Spatial Overlay Analysis

The method is performed on the selected elevation and slope data, river information, and the distribution map of CHS. Through the overlay analysis, the specific elevation and slope values of each point are obtained, and the number of points within the river buffer zone is counted.

2.3.4. Voronoi Diagram Analysis

The Voronoi diagram, also known as Thiessen polygons, is a method used for plane partitioning, which was proposed by Dutch meteorologist A.H. Thiessen [33]. Each polygon contains only a single control point, and the distance from any given point to the control point forming that polygon is less than the distance to the control points of other polygons [34]. This study utilizes Voronoi diagrams to delineate the control ranges of settlements at the same hierarchical level.

3. Analysis and Results

3.1. Settlement Construction Process

The Jin army’s primary military force in the early years of the Jin Dynasty was cavalry, and they employed the tactic of “encircling and annihilating the enemy from both flanks.” After the Song-Jin conflicts began, the infantry-heavy Northern Song army was hard to penetrate even after protracted attacks. The Jin emperors eventually realized the value of strong city defenses as a result of this. The Jin army created the Jin Great Wall defense system, which was based on towns, by implementing a “fortify cities to repel enemies” strategy in the northern frontier, which was influenced by Song defensive tactics.

In conjunction with changes in defensive tactics, communities along the Northwest and Southwest Roads had three main stages of evolution, according to historical records that included descriptions of the building of defensive structures along these roads (Table 1): Existing tribal communities were first impacted by the nomadic way of life of fishing and hunting peoples, and in order to preserve border stability, they evolved into defensive towns. As the institutional structure of the Jin dynasty developed and the social landscape of the northern border changed throughout Emperor Shizong’s reign, Jin emperors methodically planned the size, purposes, and general design of these settlements. By the time of Emperor Zhangzong, these communities had developed into important defensive structures that, along with border moat fortifications along the northern frontier, formed a vast Great Wall defense system.

Table 1.

Construction Status of Defensive Works on the Northwest and Southwest Roads.

3.2. Military Administrative System

As the highest military administrative structure for the northern frontier, the Zhaotaosi system was created by the Jin emperors to exercise unified jurisdiction over the zone. The emperor personally nominated the top official in the Zhaotaosi system, who was known as the “Zhaotaoshi”. In order to serve as central management centers, the seat of government was set up in each defense sector. While the Northwest Road seat of government, under the impact of historical events, moved from Yanzi City to Huanzhou in the tenth year of the Dading dynasty (1170), the Southwest Road seat of government remained permanently positioned in Fengzhou. Later, in the sixth year of the Mingchang era (1195), it was restored at Fuzhou.

Although Zhaotaosi’s duties are not specifically described in the Jinshi, an examination of biographical documents suggests that his main responsibilities were to build border defenses, lead military operations, pacify and deploy armies, and garrison frontier areas—all of which are components of military defense. The Deputy-Zhaotaoshi’s responsibilities, which included handling surrendered soldiers and quelling rebellious elements, were more focused on personnel management than those of the Zhaotaosi. Notably, Zhaotaoshi of the Jin Dynasty often personally led armies into battle, in contrast to the top commanders of previous defense systems who were mainly rear commanders. According to the Jinshi, “Shortly thereafter, the Jiedushi of the northwest road, Wanyan Anguo and others, proceeded towards Duoquanzi, and a secret imperial edict was issued to advance and suppress. The army was then ordered to move out via the Eastern and Western roads” [35]. This indicates that the Jin Dynasty’s Zhaotoushi were not just administrative officials in charge of the coordinated leadership of different military units along the northern boundary, but also important executive commanders who could personally lead armies into combat.

The Northwest and Southwest Roads have a wide variety of ethnic tribes because they were once governed by the Liao Dynasty. Three different kinds of border defense military units—the Mengan-Mouke armies, tribal armies, and Jiu armies—emerged under the Zhaotaosi system. Among these, the Mengan-Mouke served as the military emblem for the Jurchen. Although the Mengan commander was still under the Zhaotaoshi’s authority, he held the position of Deputy-Zhaotaoshi. This amply illustrates the Jurchen people’s position under the Jin Dynasty’s ethnic prejudice. Regulating military affairs, training military personnel, and promoting and overseeing agricultural production are the main military administration duties of the Mengan. They also handle civil affairs management responsibilities. In contrast to the Mengan, the Muoke’s duties are more targeted and mostly involve managing military-related issues, such supervising soldiers’ mounted archery training.

At the same time, the Jin rulers kept the Liao system of tribal armies and Jiu armies to govern the ethnic groups that had surrendered and were initially ruled by the Liao. The tribal military governorship, which held the second-highest position behind the Zhaotaoshi, oversaw tribal forces. These posts were set up to guard and manage different tribes, garrison, and appease various military groups. Despite belonging to separate military units, Mengan, Xiangwen, and the deputy tribal military governorship all had the same rank classification. This analysis indicates that the deputy military governorship of the tribal troop is also responsible for overseeing the daily military operations of the army. The highest-ranking administrative officer in the Jiu troop was the Xiangwen. They were in charge of garrisoning and protecting frontier communities in addition to managing day-to-day military activities. In order to support the Xiangwen in overseeing military matters, Mohu was created.

3.3. Hierarchical Classification of Settlements

3.3.1. Settlement Hierarchy Classification Basis

A hierarchical military administration structure was established to enable the central government to have direct control over the Great Wall of the Jin Dynasty’s defense system. Settlements also showed certain gradations of rank as the main defense vehicles. Among these, the rank of military administrators served as the concrete expression of settlement hierarchy.

Compared to the Northeast Road, the Northwest and Southwest Roads more thoroughly embraced the Zhaotousi system because they were the previous Liao-controlled areas.

According to the JinShi [36], “The Zhaotaosi was divided into three jurisdictions: the Northwestern Route, the Southwestern Route, and the Northeastern Route. One Zhaotaoshi was appointed, holding the rank of Principal Third Rank. Two Detupy Zhaotaoshi were assigned, each of the Subordinate Fourth Rank, responsible for persuading rebels to surrender and suppressing those who defected. One Judge, of the Subordinate Sixth Rank, was in charge of maintaining administrative order and endorsing the bureau’s documents.One Case officer, of the Subordinate Seventh Rank; One Clerk, of the Principal Eighth Rank; and two Legal officers, each of the Subordinate Eighth Rank—one Jurchen and one Han Chinese.” From a functional standpoint, the judge, case officer, clerk, and legal officers were auxiliary posts to assist the Zhaotaoshi and deputy Zhaotaoshi, notwithstanding the Zhaotaosi system’s six-level management structure. At the same time, according to the JinShi, “The seat of government of the Zhaotaosi of the Northeast Road was still located in Taizhou, where it also served as the military governorship, with the deputy Zhaotaoshi remaining stationed at the frontier” [37]. “Two deputy Zhaotaoshi were appointed, each responsible for governing Taizhou and Yichun” [38]. This suggests that the authority to oversee the settlement rests with both the Zhaotoushi and the deputy Zhaotoushi.

The Jin Dynasty’s policies of ethnic discrimination and military defense requirements both had an impact on the military administration system’s hierarchical structure. A number of ethnic groups, including the Khitan, Wanggu, and Tatars, bowed to the Jin Dynasty following their victory against the Liao. The Jin Dynasty, a minority government founded by the Jurchens, was marked by strong ethnic prejudice that produced clear divisions in the hierarchy of different ethnic groups. The military management system’s hierarchical structure mirrored this racial stratification as well. According to Volume 3 of the Jinshi [36], it is recorded that, “All Mengan and Mouke were under this administration. Each Mengan, of the Subordinate Fourth Rank, was responsible for overseeing military affairs, training martial skills, and encouraging agriculture and sericulture. Each Mouke, of the Subordinate Fifth Rank, was charged with supervising military households and training troops in martial arts, differing only in that they did not administer the Changping granary; in all other respects their functions were equivalent to those of a county magistrat.”,”Tribal military governorship. One tribal military governorship of the Subordinate Third Rank, overseeing various tribes, maintaining order in the military, with duties similar to those of a prefect. The deputy tribal military governorship of the Subordinate Fifth Rank. The judge was an official responsible for legal matters.”,” Each Jiu Army was headed by one Xiangwen, of the Subordinate Fifth Rank, in charge of guarding the frontier forts, with duties equivalent to those of a Mouke.…One Meohu, of the Subordinate Eighth Rank, assisted the Xiangwen in his duties.”

3.3.2. Settlement Hierarchy Classification Results

Five levels can be distinguished in the ranks of military management officials based on historical records (Table 2). Thus, settlements can also be categorized into five levels according to the management hierarchy. Research on traditional settlements [39,40] and prehistoric settlements [41] generally indicates that the size of a settlement is proportionate to its level.

Table 2.

Military Settlement Hierarchy Under Official Ranks.

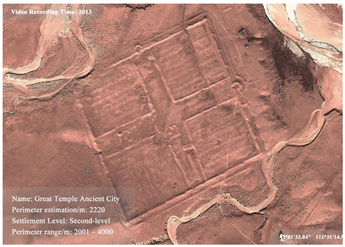

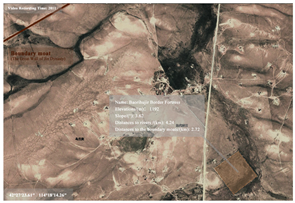

The settlement classification approach employed in archaeology for prehistoric settlements was used because there are few direct documents about the Northwest Road and Southwest Road settlements, and the extant ruins have been severely weathered. The settlements along the Northwest Road and Southwest Road were categorized based on the perimeter of the settlement sites, which was chosen as the basis for establishing settlement grades. Except for the 16 settlements that have completely disappeared, using the natural breaks classification method in ArcGIS Pro, the settlements with measurable perimeter data were ultimately classified into 7 first-level settlements, 20 second-level settlements, 24 third-level settlements, 25 fourth-level settlements, and 109 fifth-level settlements (Table 3).

Table 3.

Settlement Sizes at Different Levels and Typical Settlements.

3.4. Spatial Distribution and Site Selection Characteristics of Settlements

3.4.1. Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Settlements

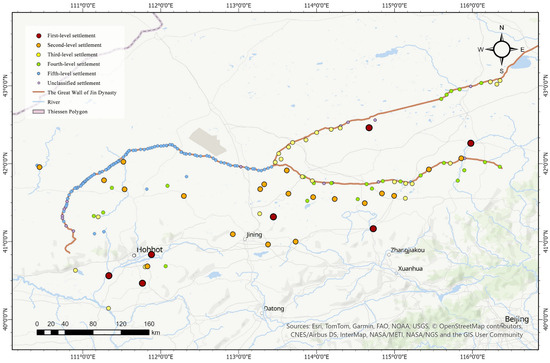

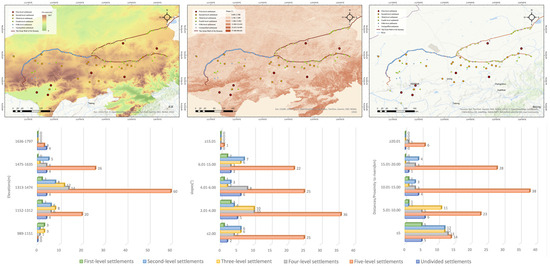

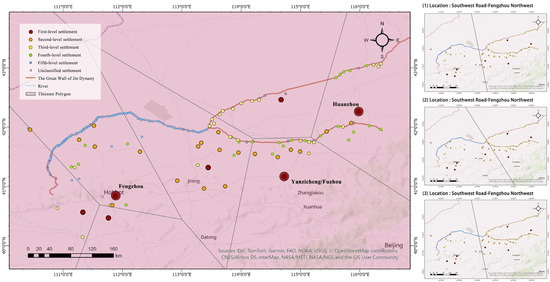

There is no discernible pattern in the general spatial distribution of communities in the northwest and southwest. The settlement density falls in proportion to the spatial position as it approaches the Jin Dynasty’s interior. Settlement size, as the main criterion for classifying settlements into different levels, directly reflects the distribution of settlement sizes (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Spatial Distribution Map of Settlements on Northwest Road and Southwest Road.

The nearest neighbor index R for these road networks is 0.550 (R < 1), with a Z-value of −12.19, according to an analysis of the overall and hierarchical nearest neighbor indices for settlements along Northwest Road and Southwest Road (Table 4). This suggests that settlements exhibit clustering patterns influenced by geographic space, rather than being randomly dispersed. Third-level, fourth-level, and fifth-level settlements exhibit varying levels of clustering, whereas first-level and second-level settlements display clear dispersion characteristics.

Table 4.

Nearest Neighbor Indexes for Settlements Along Northwest Road and Southwest Road Statistical Table.

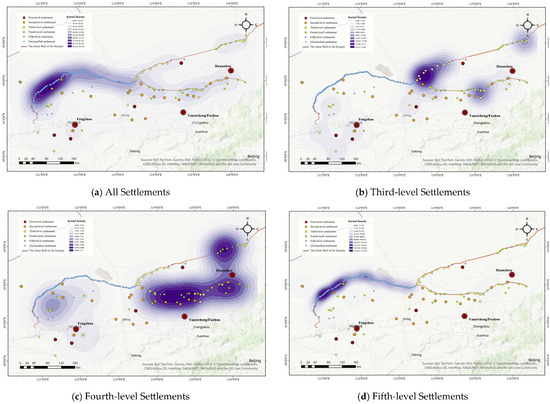

Settlements along the northwest and southwest roads exhibit a single high-density cluster center, with generally weak strip-like clustering along the boundary moat, according to kernel density analysis (Figure 4). In particular, there is a considerable spatial complementarity between the densely populated third-level and fourth-level settlements in the northwest route defense zone. While fourth-level settlements in the dense zone of the southwest route link administrative centers with boundary ditches, fifth-level settlements show clear clustering along the southwest route boundary moat.

Figure 4.

Kernel density map of Settlements in Northwest Road and Southwest Road.

3.4.2. Macroscopic Site Selection Characteristics

ArcGIS Pro software was utilized to spatially overlay settlement data with elevation, slope, and water data to investigate the distinctiveness of settlement site selection in the northwest and southwest defense zones. The elevation and slope of each settlement were then extracted. The distance between the settlements and the river was measured using the closest neighbor analysis approach.

The elevation classification scheme from the 1:1,000,000 Digital Morphological Classification of China (Table 5) and the five-level slope classification from the Third National Land Survey Technical Regulations (TD/T1055−2019) [42] (Table 6) were used to classify the elevation, slope, and distance to water systems of settlements in the northwest and southwest defense zones to perform a more scientific analysis of settlement site selection.

Table 5.

Slope Grading Standards Table.

Table 6.

Elevation Grading Standards Table.

As the northwest and southwest defense zones are located in the Inner Mongolia Plateau (Figure 5), and since 99% of the settlements are located in the third-level mid-elevation zone above 1000 m. The elevation was divided into five levels using equal interval segmentation based on the settlements’ elevation data. Furthermore, according to war geography, the optimal location for settlements is within 10 km of water. This study uses 5 km intervals to similarly categorize the distance to water systems into five levels, since the northwest and southwest zones have the furthest separations between settlements and water, which is approximately 26 km. The slope is mainly concentrated in the range of 2° to 6°. Based on China’s slope classification standards, the second-level slope was further refined, forming five observable slope intervals to reveal the site selection characteristics of different types of settlements.

Figure 5.

Spatial Distribution of Settlements Along Northwest Road and Southwest Road by Elevation, Slope, and Distance from the River.

75% of the settlements in the northwest and southwest zones are located within the relatively low elevation range of 990–1314 m, according to Figure 5, which depicts the settlements’ natural geographical environment. Furthermore, 56.6% of the settlements are located on moderate slopes that are appropriate for large-scale construction projects, whilst 22.2% are built on flat areas with slopes of less than 2°. At the same time, referencing the Wujing Zongyao, which states, “The military should travel no more than thirty li a day, to guard against unforeseen events” [43]. 82.8% of the settlements would be within a day’s trip from a water source if the Jin Dynasty army could travel 30 Li (In ancient China, the unit of measurement for distance was Li. Thirty miles is fifteen kilometers, and one mile is 500 m.) per day, as the Song Dynasty army did.

Overall, the site selection pattern for the settlements in the northwest and southwest defense zones is defined by “low elevation, flat areas, and proximity to water sources.”

3.4.3. Site Selection Characteristics at Different Settlement Levels

An additional hierarchical study of the locations of settlements at various levels was carried out in order to elucidate the site selection variations of each settlement level:

- (1)

- First-level Settlements

First-level settlements are all found in low-slope zones with average altitudes that are relatively low and slopes of less than 10°. The three settlements that formerly housed the Zhaotaosi seat of governments are located within 4 km of a river, further demonstrating their obvious proximity to water. Because of the influence of the three first-level settlements facing the Xixia in the southwest zone, the average elevation of these settlements is marginally higher than that of the northwest defense zone. Protected to the north by the Yinshan Mountains and to the west by the Yellow River, these three first-level settlements are situated at the lowest point in the southwest defense zone.

The military management system’s hierarchical features dictate that there should only be one Zhaotaoshi serving as the central command location in each defense zone. On the basis of settlement size, seven first-level settlements were identified. First-level settlements should all have certain settlement management capabilities, according to an analysis of the military functions corresponding to settlement levels, with the exception of the three settlements that formerly served as the Zhaotaoshi in the northwest and southwest defense zones. Voronoi polygons were utilized to define the first-level settlements’ geographical jurisdiction in order to make the settlements’ spatial management scope clear (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Voronoi diagram of First-level Settlements.

The findings show that the remaining four settlements created three separate control zones oriented in various directions, with the exception of the three settlements where the Zhaotaosi seat of government was constructed. Between Fengzhou and Fuzhou, a central area under the control of a major settlement developed. A major settlement control zone formed between Fengzhou and Fuzhou. Historical context and spatial distribution study indicate that the relocation of its headquarters undermined the Northwest road zones across the boundary moats zone. Consequently, this hamlet served as a key hub for enhancing information exchange between the two highways as well as a vital reinforcement center.

Furthermore, with the exception of the Zhaotaosi seat of government, the First-level settlement along the Northwest Road were located close to the outer boundary moats. Between the outer and inter boundary moats, there were no dispersed settlements. In terms of geographical location, these settlements mainly improved regional settlement management and control by quickly mobilizing settlements along the main boundary moats. The two first-level settlements next to the Southwest Road seat of government relied on the Yellow River as their advance defense rather than boundary moats as exterior intercept lines. According to historical records, “The city walls were built for defense. The country’s security relied on the capital and several nearby prefectures. The northern frontier was not defended; the Yellow River could hardly be relied upon” [44]. This suggests that in the northern frontier, the Jin emperors built a coordinated defense line that included both the Yellow River and settlements. The main goal of the two first-level settlements to the left of Fengzhou was to put an end to XiXia rebellion.

- (2)

- Second-level Settlements

Second-level settlements are more widely dispersed over the elevation range of 1152–1635 m, and their average elevation (1385 m) is marginally greater than that of first-level settlements (1208 m). Nonetheless, 65% of the settlements are situated in zones with slopes of less than 6°, suggesting that they are typically found in places with mild slopes. Furthermore, 60% of the settlements are located within 5 km of a river, demonstrating their obvious closeness to water.

Four of these settlements, with elevations above 1475 m, slopes above 2 degrees, and separations from rivers exceeding 14 km, lack clear natural geographical benefits for construction. However, these four settlements are all located within a 10–60 km range from the boundary moat.

In conclusion, the position of the boundary moat and management requirements have an impact on the choice of second-level settlement sites in addition to natural environmental considerations. To enable prompt information transfer, these settlements are scattered between the command settlements and the boundary moat rather than all being situated in gently sloping terrain.

- (3)

- Third-level Settlement

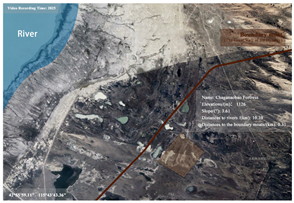

With an average elevation of 1317 m, which is lower than that of second-level settlements, third-level settlements are mostly found in the elevation ranges of 1152–1312 m and 1313–1474 m. Although there is no obvious predilection for low elevation or moderate slopes, the settlements are spread out over zones with slopes of less than 15°. With a very balanced distribution between ≤5 km and 5.01–10 km, 96% of the settlements are within 10 km of a river.

Third-level settlements in the Southwest Road defense zone are clearly close to water sources, according to spatial location research. On the other hand, settlements that are not near water tend to be situated nearer to higher-level settlements. According to functional analysis, these settlements mainly function as auxiliary outposts, offering first-level settlements troop garrisons and material reserves to facilitate prompt reinforcements. Third-level settlements in the northwest defense zone are primarily found within 10 km of a river, indicating a definite preference for areas close to the boundary moat. About 13 km separate the “Luotuoshan” settlement from the river; however, this distance is less than 0.5 km from the boundary moat.

In general, the location of the boundary moat has the biggest impact on the choice of sites for third-level settlements. Additionally, places near water were emphasized.

- (4)

- Fourth-level Garrison Settlements

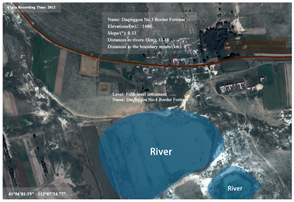

When it comes to slope and elevation, fourth-level settlements do not offer many advantages. With an average elevation of 1389 m, 88% of the settlements are reasonably evenly spread among zones with slopes of less than 6°, primarily within the 1313–1474 m range. With 52% of the settlements situated within 5 km of a river, they do, however, exhibit certain preferences for proximity to water.

Fourth-level settlements are primarily found along the northwest defense zone’s the main boundary moat and branch boundary moat in terms of spatial distribution. Regarding height, slope, and distance from rivers, there are no notable construction advantages. There are only five fourth-level communities in the southwest defense zone, and they are mostly situated between first-level settlements and the boundary moat.

Overall, defense purposes are considered in addition to natural geographic variables when choosing locations for fourth-level settlements. Fourth-level settlements in the northwest defense zone are mainly responsible for territorial defense, however in the southwest defense zone, they serve as key centers for vertical information transmission.

- (5)

- Fifth-level Settlements

Fifth-level settlements have an average elevation of 1411 m, with their slopes and distances from rivers distributed fairly evenly across Levels 1 to 4. Spatially, these settlements are predominantly located along the southwest boundary most. There are just two fifth-level settlements in the northwest defense zone, both of which are situated along the boundary most.

In order to solve the problem of wind and sand filling the trenches, making them useless for defense, the Jin emperors suggested a construction method that involved “first building settlements, then having garrisoned armies construct the boundary moats”. Fifth-level settlements were mostly constructed for the purpose of building the boundary most defense line, as evidenced by their spatial distribution, which is mainly along the southwest boundary most. With little impact from natural geographic factors, fifth-level settlements generally show distinct site selection features centered on protecting the boundary most.

The site selection characteristics of typical settlements at various levels are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Comparison of spatial siting characteristics of clusters at various levels Schematic diagrams.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Evolution of Defense Strategies Reflected in the Construction History of Settlements

Scholars have examined settlements as a component of the Jin Great Wall defense system, influenced by the extant archaeological relics from the Jin Dynasty. With varying distribution patterns throughout time, it is clear from the construction history of these settlements that they were the principal defensive force for preserving the Jin Dynasty’s northern frontier. The varying decisions made by Jin rulers at different eras, which reflected the development of defense tactics throughout time, were the primary cause of the variations in settlement distribution patterns.

- (1)

- “Offensive Defense” Strategy Supported by Military Combat Power

In the early Jin Dynasty, the construction of fortified cities was neglected, and even the emperor lacked a fixed capital. “Initially, there were no settlements, and people lived scattered, calling it the Emperor’s Camp” [45]. At that time, the Jin rulers, as a hunting and fishing people, possessed formidable combat strength. According to the Jinshi, “the Jin’s military campaigns were carried out with divine precision when they rose to power.” [46] Victorious in battle and conquering lands, they met no equivalent in their period. Boundary ditches were built in the southern Mongolian region during the reigns of Emperor Taizong and Emperor Xizong, but their design remained primitive and provided little useful defensive value. Within ten years, they had created their vast enterprise. Moreover, there are no reports of border incursions at this time. The boundary moats probably functioned more as demarcation lines than as active defenses, given the Jin soldiers’ battle ability. According to historical study, the early Jin military did not establish extensive defensive measures; instead, it relied mainly on its fearsome combat strength to prevent northern boundaries. Rather, they mostly used “offense as defense” as a tactic.

- (2)

- “Reserve Defense” Strategy Using Settlements as Garrison Bases

The Jin Dynasty invaded the Song Dynasty to the south after conquering the Liao Dynasty, but despite persistent attacks, they were unable to overcome the Song Dynasty’s defenses. Jin monarchs eventually realized the value of walled cities for defense as a result of this experience. “The Saba Rebellion” in the Northwest Frontier Region during Emperor Shizong’s reign increased his worry about the stability of the northern boundary. The Jin used pre-existing tribal ties in the area to build a network of fortified settlements along the northern border after moving the Northwest border administrative base. Standardized building techniques, such as “linear alignment” and “establishing settlements before constructing moats,” later appeared. The settlement defensive systems on the Northwest and Southwest frontiers had begun to take shape by the middle of the Jin dynasty, according to a historical analysis. The Jin military started depending on settlements and other fortifications for defense as a result of this strategic change.

- (3)

- “Cooperative Defense” Strategy Formed by the Addition of Boundary Moats and Settlements

In the latter years of Emperor Shizong’s reign, the construction of boundary moats was suggested as a way to lower the cost of garrisoning as the Mongol tribes gained prominence and the Jin army’s combat capabilities declined. But because of the intense sandstorms and the filling of the trenches in the northwest and southwest, a construction strategy was chosen in which the garrisoned armies built the boundary moats together after settling in. However, whether boundary moats were dug during this time in the northwest and southwest is not directly supported by historical records. By the reign of Emperor Zhangzong, the problem of northern incursions intensified, prompting him to reconstruct the Jin Great Wall defense system. Large-scale construction of boundary moats during the Mingchang and Cheng’an years. Once the boundary moat construction was finished, a coordinated defense system consisting of both boundary moats and settlements began to take shape along the southwest and northwest roads.

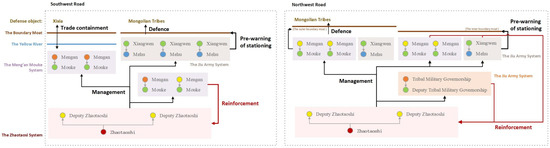

4.2. The Defensive Strategies Reflected by the Military Functions of Settlements at Different Levels

Settlements’ defensive capacities were directly impacted by the military administration system, which was the fundamental organizational force that made the settlement system effective. The defensive roles and strategic significance of these settlements were directly reflected in the duties of administrative authorities at different levels. A specific mapping link between the ethnic characteristics of settlements and their hierarchical levels developed concurrently, influenced by the distinct ethnic makeup of the Northwest and Southwest defense zones. This study investigates the defensive tactics used by the Jin monarchs within their territorial domains by examining the functional and ethnic composition differences across settlement tiers.

- (1)

- The Zhaotaosi’s duties mainly represent the settlements’ three defensive functions: regulating the general design of the border defense, guaranteeing the concentration of military might, and facilitating the prompt mobilization of armies in times of conflict. As material representations of the defensive functions of the Zhaotaosi, first-level settlements include not only the location of the Zhaotaosi seat of governments but also management settlements that house sizable garrisons or act as hubs for rapidly assembling nearby military forces. These settlements also have unique regional administrative features.

- (2)

- The tribal army played a significant role in the early Great Wall defense system of the Jin Dynasty, despite not being largely made up of members of the Jurchen ethnic group. The tribal military governorship held a position even higher than the Mengan from the standpoint of the administrative hierarchy. Tribal military governors’ level were even higher in the hierarchical administrative structure than the Mengan, serving as regional administrators under the jurisdiction of first-level settlement. Large second-level towns south of the boundary moat were the main location for the tribe military ruler. As a lower-level administrator, the deputy tribal military governorship helped the tribal military governorship manage the day-to-day military operations of the northwest defense zone’s fourth-level settlements. However, the northwest road defense area has eight tribal armies, according to the records in the historical materials that are currently available, whereas the southwest road defense area has no tribal armies mentioned in the pertinent historical sources. The second-level and fourth-level settlements of Southwest Road should be under the jurisdiction of the Mengan-Mouke system with the ethnic distribution analysis.

- (3)

- From the early Jurchen production organization, the Mengan-Mouke system developed into a regional military government. Its duties went beyond military leadership to include some administrative responsibilities for domestic endeavors like farming. Mengan mostly controlled second-level and third-level settlements in the defense zone of the southwest road, and third-level settlements along the boundary moats of the northwest road. In contrast, Mouke mostly oversaw fourth-level settlements, which were dispersed throughout second and third-level settlements. This further suggests that Mouke and deputy tribal military governorship were essentially auxiliary administrators who oversaw daily defensive operations in smaller settlements, including border warnings and military training, with a particular emphasis on military administration.

- (4)

- The management of fourth and fifth-level settlements was managed by the Jiu army management system. The Jiu army’s commanding officers, Meihu and Xiangwen, were principally in charge of overseeing military operations within their respective regions and defending the frontier.

In conclusion, the way the border defense administration system operated during the Jin Dynasty clearly reflected the defensive functions of settlements at all levels. Under the Zhaotaosi system, the Zhaotaosi had overall control over strategic deployments, and set up large-scale first-level settlements as hubs for to realized centralized management, which reduced the difficulty of garrisoning the linear defense line. Different nationalities are categorized, integrated, and incorporated by the Jiu army system, the Mengan-Mouke system, and the tribal army system in order to accomplish defense responsibilities including garrison, logistics support, and core operations.

However, because of differences in ethnic makeup, the Northwest Road and Southwest Road had slightly different defensive tactics. Among them, in order to ensnare the original tribes, the Northwest Route depended on tribal armies as a vital core reinforcement. Lower-level ethnic garrison troops were positioned along the boundary moats as part of this tiered defense structure (Figure 7 (right)). On the other hand, tribal forces along the Southwest Route are not mentioned in historical accounts. The Jiu armies were the main force occupying the boundary moats, while the Meng’an-Muke armies constituted the core military strength under the Zhaotaosi. Two significant coordinated defense zones also developed as a result of spatial location (Figure 7 (left)). This overall organization provides a clear and defined defense strategy with military units organized according to ethnic distinctions, defense functions established according to ethnic hierarchy, and unified management under the Zhaotaosi system. However, due to differences in ethnic composition between the Northwest and Southwest Road, each defense sector adopted slightly different defensive strategies.

Figure 7.

Schematic Diagram of Settlement Defense Functions Based on Management Functions.

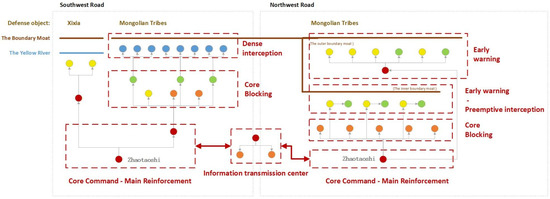

4.3. Defensive Strategies Reflected in the Distribution Patterns of Settlements at Different Level

Despite being impacted by the passage of time, the Jin Dynasty’s settlement defense strategy consistently adhered to the defensive principle of “macro management, partition defense”. Different micro-defense techniques have also developed in the northwest and southwest road defense areas as a result of the natural physical context and external ethnic threats. The Northwest Road was used to defend the Mongolian tribes and was impacted by the migration of the seat of government and the distribution of the boundary moats, forming two main defense areas. The southwest road primarily faces Mongolia and Xixia for two-way defense, forming two main defense areas. Between the two defense zones, a crucial link center was created concurrently.

Third and fourth-level settlements were positioned along the border moats for regular garrisoning in the Northwest Road defense zone. To strengthen troop reserves, larger second-level settlements were built between the inner boundary moat and first-level settlements. In order to improve early warning capabilities and fortify defenses, the inner boundary ditch’s settlement density and elevation were noticeably higher than those along the outer boundary ditch, according to the settlement site selection features. All things considered, this demonstrated a two-pronged early warning approach along the inner and outer boundary moats, which mirrored a military tactic of “luring the enemy deep into territory for decisive interception” (Figure 8 (right)).

Figure 8.

Defensive Strategies for the Northwest and Southwest Road Based on Settlement Distribution Patterns at Various Levels.

The distribution pattern of spatial site selection in the Southwest Road defense zone is determined by strategic necessity. To the west, facing the XiXia, the Yellow River acted as a natural barrier because the Jin Dynasty and the XiXia had comparatively cordial relations. Only first-level and third-level settlements were put up for military early warning and daily contacts. However, the Jin Dynasty’s main security challenge to the south was the Mongol tribes. First-level settlements are crucial to the defense line since they are the main command centers and have the best military might and resources. Between the first-level settlements and the boundary moats, second- to fourth-level settlements create supplementary defense lines that impede enemy advances and bolster the core defense. Fifth-level settlements are smaller-scale and closely dispersed along the boundary moats, acting as frontline barriers that successfully impede the enemy’s advance.

Collectively, the southwest road forms a tiered battle strategy of “blockade-delay-defense” (Figure 8 (left)) with a more varied defense structure and more clearly defined functions than the northwest road.

5. Conclusions

The current settlements in the Jin Dynasty’s Northwest and Southwest Regions are examined in this study. It makes clear the defensive tactics present in these settlements by using combined quantitative and qualitative methods from a dual “historical–spatial” perspective. The following are the main conclusions:

- (1)

- The Jin army’s fighting effectiveness progressively decreased due to the regime’s evolution and external socioeconomic conditions. As a result, Jin leaders started using pre-existing tribe towns to build a defensive settlement line. The Northwest and Southwest Routes’ building procedures most closely mirror the Jin Dynasty’s general change in defensive strategy—from “military deterrence” to “tactical defense”—since these areas were the main targets of Mongol invasions in the late Jin Dynasty.

- (2)

- Settlements had a tiered structure due to the military administration system’s hierarchical character. Settlements developed unique hierarchical characteristics as a result of the varying responsibilities of administrators at different levels, which were influenced by a variety of factors, including administrative needs, defensive requirements, and ethnic composition, which set the Northwest and Southwest Frontiers apart from other regions under Jin rule. In the Northwest and Southwest Regions, a defense strategy that was defined by “establishing different military formations based on ethnic differences, assigning different defensive functions according to ethnic hierarchy, and implementing unified management through the system of military command offices” was formed by the military administration system and the duties of administrators, which were direct reflections of settlement defense strategies.

- (3)

- Based on pre-existing tribal settlements, the Jin Dynasty progressively built the Jin Great Wall defense system, which was made up of settlements and border ditches, in response to external influences. However, the Northwest Route adopted a fighting strategy of “luring the enemy deep into territory for decisive resistance” and established a dual early warning system along both sides of the boundary ditches due to the geographical disparities between the Northwest and Southwest Routes. When battling Western Xia, the Southwest Route avoided high-density settlements and used a commerce containment strategy; when facing the Mongols, it used small-scale settlements to create high-density intercept lines, creating a defense tactic known as “interception-delay-engagement.”

In conclusion, a structured defensive settlement network was not initially established by the Jin Dynasty. Rather, it developed as a result of a variety of complex elements, including the entry of Central Plains culture and external socioeconomic conditions. There were noticeable ethnic variations between the Northwestern and Southwestern Frontiers. Different defensive techniques across the two frontiers resulted from the emergence of distinct functional divisions under the influence of administrative and garrison systems.

In order to identify the unique regional features of the Northwest and Southwest defensive zones, this study uses settlements as its material starting point. It reveals the distinctive character of the Jin Dynasty’s border governance by elucidating the defensive tactics used in these areas through the integration of several aspects including as social environment, administrative systems, and ethnic composition. This study develops a multifaceted comprehensive evaluation framework to promote the holistic preservation of the Jin Great Wall defense system, offering theoretical justification for the shift from the protection of individual sites to the integrated conservation of the defensive corridor system as a whole.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.X. and Y.W.; methodology, Y.W.; validation, D.X. and Y.W.; investigation, Y.W.; resources, Y.W.; data curation, Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.W.; visualization, Y.W.; supervision, D.X.; funding acquisition, D.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China General Program: Research on Correlation Identification and Conservation Strategies for the Jin Dynasty Great Wall Heritage Based on Network Analysis and Simulation (52278017), Hebei Provincial Social Science Foundation Project: Research on Pre-Ming Great Wall Heritage in Hebei Province from a Historical Geography Perspective (HB24WH031), Hebei Provincial Higher Education Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project: Research on Holistic Conservation of Pre-Ming Great Wall in Hebei Province (JCZX2025034).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yan, W.; Wang, S.J.; Zhe, J.R.; Liu, P. Defensive wisdom in the construction of traditional coastal settlements in Eastern Fujian: The case of Shilan Village, Fuding. Archit. J. China 2022, 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.B. The Jin Dynasty’s boundary moat and the Great Wall. Chin. Front. Hist. Geogr. Res. 2008, 1–9+148. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.Z. A study on the evolution of administrative structures for the Jin Dynasty Great Wall (II): The Northwest and Southwest Routes of the Jin Dynasty. J. Hebei Univ. Geosci. 2018, 41, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. A discussion on the commandant of Xijing in the Jin Dynasty. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2017, 37, 158–167. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y. Research on border defense and ethnic governance in the Western Capital Circuit of the Jin Dynasty. J. Lanzhou Educ. Inst. 2020, 36, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, D.; Zhang, Y.K.; Li, Y. The Jin Dynasty Great Wall Defense System and Military Settlements; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Zhou, X.Q. City sites from the Jin and Yuan Dynasties North of the Yin Mountains. Inn. Mong. Soc. Sci. 2019, 40, 89–93+2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.G.; Deng, H.W. Jin Dynasty frontier fortifications and boundary ditches in Damang Banner. Inn. Mong. Cult. Relics Archaeol. 2000, 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, D.; Zhang, B.Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, W. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of military settlements along the Jin Dynasty Great Wall. J. Hebei Univ. Geosci. 2022, 45, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Liu, K.X.; Wang, Y.W. Preliminary exploration of factors influencing the planning and layout of the Jin Dynasty Great Wall defense system. Anc. Archit. Gard. Technol. 2025, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, F. A study on the location of the headquarters of the Northwestern Route Commandery during the Jin Dynasty. Chin. Front. Hist. Geogr. Res. 2024, 34, 63–74+222–223. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, D.; Wang, M. Spatial logic of site selection for garrison forts along the Great Wall of the Jin Dynasty. Anc. Archit. Gard. Technol. 2024, 73–76+87. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, G.; Han, G.-S.; Lang, X.X. Cultural heritage site selection characteristics and the impact of the natural environment in Jinan city, China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.Y.; Ma, L.H.; Xu, J.Y.; Peng, Y. Spatial-temporal distribution characteristics and influencing factors of immovable cultural heritage in Hubei, China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.L.; Huang, Y.H.; Chen, Y.L.; Lu, J.; Yang, T. The distribution pattern and spatial morphological characteristics of military settlements along the Ming Great Wall in the Hexi Corridor Region. Buildings 2025, 15, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Liu, H.T.; Zhang, L. Research on the spatial–temporal distribution and morphological characteristics of ancient settlements in the Sichuan Basin. Land 2024, 13, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.M.; Guo, Q.L.; Wu, M.Y.; Wang, Y.; Cui, K.; Sun, M.; Li, J. GIS-based spatial-temporal analysis of castle-based military settlements in the Ming Great Wall defense system of Yulin Zhen, Shaanxi Province, China. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2025, 18, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.X.; Xiang, H.W.; Huang, Z.S. Architectural spatial distribution and network connectivity characteristics of ancient military towns in Southwest China: A case study of Qingyan Ancient Town in Guiyang. NPJ Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, S.H.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.Q. Systematic layout of Tang Dynasty military settlements in Aksu region, Xinjiang. Landsc. Archit. 2024, 31, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, X.L.; Li, Z. Spatial distribution characteristics of the fortified settlement system in Northwest China during the Northern Song Dynasty. Archit. Herit. 2024, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Wang, Y.B.; Song, F. Space optimization of historical landscape of the Great Wall villages based on landscape ecology: A case study of Chicheng area in Zhangjiakou. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2023, 22, 1057–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.L.; Li, Z. Spatial pattern analysis of military river defenses in the Ming Great Wall: A case study of the Shanxi section of the Yellow River. Landsc. Archit. 2025, 32, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wang, K.X.; Huang, C.L.; Lin, Q. Layout and site selection of military settlements in Ming Dynasty Guizhou. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 38, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.C.; Zhang, Y.K. The fractal structure of the Ming Great Wall Military Defense System: A revised horizon over the relationship between the Great Wall and the military defense settlements. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 33, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yang, M.; Ding, F.; Sheng, G. Analysis of the site selection and defense layout of Ming Dynasty Western Fan Guards from the perspective of GIS. Sci. Discov. 2023, 11, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.N.; Bian, L.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, S.; Mu, N.; Xiao, T. Resource supply and demand model of military settlements in the cold weapon era: Case of Zhenbao Town, Ming Great Wall. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Li, B.H. A similar ecological development historical city: The study on the spatial distribution and pattern evolution of the planning history of the Manchu city in the Ch’ing Dynasty of Ancient China. Ecol. Inform. 2021, 64, 101394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.X. (Ed.) Historical Atlas of China, Vol. 6: Song, Liao, and Jin Dynasties; China Map Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, P.J.; Evans, F.C. Distance to nearest neighbor as a measure of spatial relationships in populations. Ecology 1954, 35, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Lang, X.; Han, G. Research on the protection of and renewal strategies for historic buildings in the ancient city of Liaocheng based on multisource data. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2024, 21, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cui, Z.; Fan, T.; Ruan, S.; Wu, J. Spatial distribution of intangible cultural heritage resources in China and its influencing factors. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Determination of the temporal–spatial distribution patterns of ancient heritage sites in China and their influencing factors via GIS. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiessen, A.H. A machine for trisecting angles. Sch. Sci. Math. 1914, 14, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.R.; Chen, Z.R.; Liu, Y.M.; Li, Y.L.; Guo, W.; Tang, X.M.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.T. Spatial distribution model of municipal solid waste based on GIS remote sensing data analysis. Environ. Eng. 2023, 41, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toqto’a; et al. History of the Jin Dynasty; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1975; Volume 94. [Google Scholar]

- Toqto’a; et al. History of the Jin Dynasty; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1975; Volume 57. [Google Scholar]

- Tetuo; et al. History of the Jin; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1975; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Tetuo; et al. History of the Jin; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1975; Volume 122. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Lu, P.; Mao, L.; Chen, P.; Yan, L.; Guo, L. Mapping spatiotemporal variations of Neolithic and Bronze Age settlements in the Gansu-Qinghai region, China: Scale grade, chronological development, and social organization. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2021, 129, 105357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.G.; Li, X.J. Research on the evolutionary characteristics of hierarchical scale in rural settlements of traditional agricultural areas: A case study of Zhoukou City, Henan Province. Reg. Res. Dev. 2020, 39, 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.J.; Zhang, Y.W.; Lu, P.; Chen, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. Research on the hierarchy of early settlement sizes based on the K-means clustering method. Reg. Res. Dev. 2020, 39, 176–180. [Google Scholar]

- TD/T1055−2019; Technical Regulation of the Third Nationwide Land and Resources Survey. Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Zeng, G.L.; Chen, J.Z.; Huang, M.Z. (Eds.) Military Manual: General Principles; Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2017; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Toqto’a; et al. History of the Jin Dynasty; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1975; Volume 106. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.M.; Cui, W.Y. The Annotated History of the Great Jin; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1986; Volume 33. [Google Scholar]

- Toqto’a; et al. History of the Jin Dynasty; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1975; Volume 44. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).