Abstract

Heritage conservation and environmental protection have similarities, both aiming at conserving structures and systems in their original state. While environmental protection prioritizes intact ecosystems, heritage conservation values past cultural achievements, thus reflecting the difference between nature and culture. Our research purpose is to analyze the interaction of these two disciplines for historic windows, which can be renovated, technically upgraded, or replaced by a new window. As the methodology, an LCA model was applied, where, after defining a model window material and energy flows in three scenarios, the related environmental impacts were investigated. The results show that the considerably lower loss of energy with a new window by far outweighs the impacts from the production of the new window. This becomes apparent for nearly all impact categories. The sensitivity analysis reveals that the energy source for heating has a major impact. Changing from fossil to renewable energy in the future will reduce the advantage of new windows markedly. Such novel approaches should support the integration of environmental considerations into heritage conservation.

1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Interdisciplinary Relevance

Heritage conservation and environmental protection, though traditionally distinct, share a fundamental goal: the preservation of existing systems—whether natural ecosystems or cultural heritage structures. This convergence is increasingly relevant in the context of sustainable development, where the reuse of existing resources plays a critical role in reducing environmental impact. Built heritage, particularly architectural structures, represents a significant reservoir of embodied energy and materials [1]. Recognizing this, the concept of “gray energy” has evolved into “golden energy,” emphasizing the ecological value embedded in historic buildings [2].

The evolutionary nature of both natural and cultural systems underscores the selective endurance of structures that are functionally and economically viable. This parallels Darwinian principles and highlights the importance of adaptive reuse [3]. In times of scarcity, conservation is often driven by necessity, while periods of prosperity tend to favor demolition and new construction [4]. Today, the prestige associated with energy-efficient buildings aligns ecological and economic incentives, creating new challenges and opportunities for heritage conservation [5].

1.2. Focus on Historic Windows

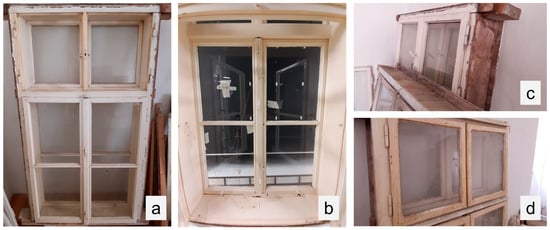

Windows in historic buildings are a critical yet often overlooked component in environmental assessments. Box-type windows are double sash constructions commonly found in historic buildings across Central Europe, especially Germany and Austria. Over 100 million box-type windows are still in use on building façades in Germany and Austria [6]. The latter alone has an estimated 2.0 to 3.5 million historic windows, primarily box-type (Figure 1), across protected and non-protected buildings [7,8]. Decisions regarding their renovation or replacement carry substantial environmental implications due to their material composition, energy performance, and heritage value [9].

Figure 1.

Old Viennese box-type window from the collection of the Information and Training Center for Monument Preservation—Kartause Mauerbach of the Federal Monuments Office Austria: (a) whole window, (b) outer sash, (c) solid post frame, (d) sash detail.

This paper focuses on the environmental impact of interventions on historic box-type windows, using life cycle assessment (LCA) as the primary analytical tool. While LCA studies often emphasize Global Warming Potential (GWP), recent research shows that assumptions about lifespan and end-of-life scenarios significantly influence the outcomes [10,11]. For example, restoring windows can reduce heating energy by 4–22%, depending on the intervention, while full replacement may lower life cycle energy consumption by around 23% [12,13,14]. The case study shown in this paper demonstrated how LCA can be applied as an analytic tool, which opens the way to further integration of LCA into heritage conservation. Life cycle assessment (LCA) and its complementary methods are essential tools for enabling a green transformation in heritage science. They provide a structured, evidence-based approach to evaluate environmental, economic, and social impacts of conservation practices, guiding sustainable decision-making [15].

1.3. Prior Research

Existing studies have explored various aspects of box-type window performance, including air exchange rates, thermal insulation, and material impacts. Restoration measures such as sealing and glazing upgrades have demonstrated substantial improvements in energy efficiency [16,17]. The heat transfer coefficient (U-value) of a historic box-type window in the Old Viennese style (Figure 1) is 2.5 W/m2 in poor condition (Figure 2) and can be improved by around 25% through restoration measures alone, without any structural modifications [18]. Window ventilation and leakage play a significant role in a building’s overall energy performance [19]. Studies on historic buildings with box-type windows have shown that these windows can allow for considerable air exchange even without user interaction. Renovation efforts can significantly reduce this unintended airflow, improving energy efficiency [20]. Further research into the hygrothermal behavior of box-type windows revealed that the level of air exchange varies depending on whether the inner or outer sashes are sealed, highlighting the complexity of managing ventilation in heritage window systems [21]. However, such measures could result in lower indoor air quality depending on a building’s ventilation system [17].

Figure 2.

Common damage to historic windows: (a) peeling oil paint, (b) broken glass pane, (c) slanted wings, (d) drafty inner wing.

Nevertheless, these interventions also introduce new environmental burdens due to the embodied energy in modern materials. It is essential to evaluate whether this impact can be offset by reducing heating, cooling, and electrical energy consumption [22]. Citherlet et al. [23] demonstrated that complex window and glazing systems contain more embodied energy than simpler systems, but their superior thermal insulation properties during use compensate for this disadvantage. As the use of sustainable materials and energy efficiency of buildings is increasing, the environmental impacts beyond the operational stage gain importance [24].

The recyclability of window components varies widely. While aluminum frames achieve high recycling rates [25], materials like PVC and laminated glass often end up in landfills [22,26,27,28,29]. With wooden frames, while recyclable or usable for energy recovery, surface treatments make recycling difficult [30]. Advanced window technologies further complicate recycling due to the presence of rare metals and coatings [31]. Despite these insights, comprehensive evaluations of historic window interventions—balancing heritage value, energy performance, and environmental impact [32]—remain limited. The reuse of entire windows is rare, mainly due to technical obsolescence, physical damage during disassembly and transport, and design and assembly techniques that hinder disassembly [22]. Box-type windows are complex physical systems that require a gradual decrease in air and diffusion tightness from the interior to the exterior [32], which can sometimes hinder their reuse.

1.4. Research Gap and Objectives

There is a clear need for a systematic analysis of historic box-type window interventions that integrates both ecological and heritage conservation perspectives. This study addresses that gap by applying LCA to assess the environmental consequences of renovating versus replacing historic windows. It aims to provide evidence-based guidance for decision-making in heritage building renovations.

1.5. Contributions and Structure

This paper fosters interdisciplinary dialogue between heritage conservation and environmental science by quantifying the impacts on the environment of interventions for historic box-type windows—restoration, new glazing, and replacement—and examining the trade-offs between operational energy savings and embodied energy. Based on the findings, it offers recommendations for sustainable approaches to the treatment of historic windows. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 outlines the methodology and LCA framework. Section 3 presents the results and analysis. Section 4 discusses implications for policy and practice, and Section 5 concludes with key findings and future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

To analyze the consequences of the intervention, the following steps were taken:

- Definition of a model window;

- Energy flow through the model window;

- Life cycle assessment of defined scenarios.

2.1. Model Window

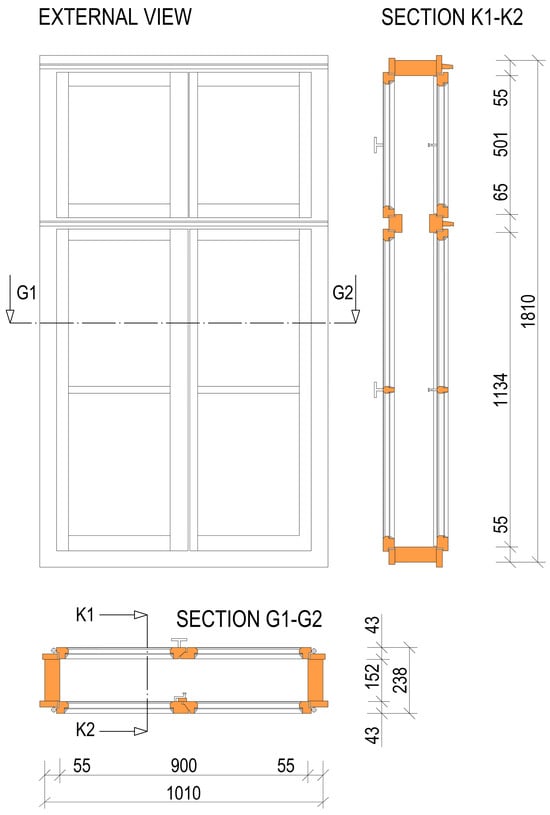

For this study, a window construction from the collection of the Information and Training Center for Monument Preservation at the Austrian Federal Monuments Office (located at Kartause Mauerbach, Mauerbach, Austria) was selected as a reference object (see Figure 3). Typologically, the window represents a double window of the “Old Viennese Style”, with outward-opening exterior sashes. The fittings, including turn fasteners, operating rods, and simple pivot hinges, indicate a late-19th-century origin. This assumption is further supported by details of the carpentry work, the condition of the wooden elements, and the window glass. The outer frame dimensions are 101 cm × 183 cm (Figure 4). To obtain representative findings, a window typical of Vienna’s historic building stock was deliberately chosen. Many ongoing projects assess whether such windows should be preserved, and their allegedly poor energy performance is often cited as a reason for replacement.

Figure 3.

Studied box-type window mounted in a window test rig for U-value determination.

Figure 4.

Plan of the examined box-type window construction.

A study by Kain et al. [18] found that a window of this type, without any improvements, has a U-value of 2.55 W/m2K. Adjusting the fittings and adding adhesive seals to the inner sash reduced the U-value to 2.2 W/m2K. Fully sealing the window system (by taping the sashes and eliminating convection within the structure) improved the U-value to 1.9 W/m2K. The measurements were carried out at the window testing facility of MA 39, Vienna. The results are comparable to an earlier work from Kain et al. [33] and confirm the default value of the Austrian standard for the calculation of heat transfer coefficients for historic windows [34].

2.2. Energy Demand

The lifespan for the renovated and newly installed windows was set at 30 years, following the approach of Citherlet [23]. To estimate heat losses, the climatic conditions of Vienna were used, with 2821 Kelvin × days (Kd) and 193 heating days per year, based on an average temperature difference of 14.6 K [35]. During the use phase of the windows, the energy demand for space heating was considered. The heating mix used is based on the average share of different energy sources for space heating in Austrian households [36]. The heating mix consists of 41% biomass, 26% natural gas, 19% oil, and 14% electricity [36]. The Austrian electricity mix consists of 53% waterpower, 27% imports, 14% photovoltaic, 2% wind and biomass each, and 2% others [37].

2.3. Life Cycle Assessment

A standardized LCA according to ISO 14040 [38] was conducted. The system boundary extends to the outer edge of the window frame to ensure comparability. One of the reasons for this choice is to exclude potential interaction of the window and the surrounding construction, which may vary from case to case, and instead to focus on the window itself.

2.3.1. Goal and Scope

The goal of the LCA is to compare the environmental impacts of three scenarios for managing historic box-type windows.

2.3.2. Functional Unit

The functional unit of this study is the lighting and ventilation of a room through a window (frame exterior dimensions: 101 cm × 183 cm) over a life span of 30 years. The system boundaries of this LCA include the manufacturing and construction phases (production of all materials used, energy demand with heat loss over the window included, transport), and the usage phase (energy demand for space heating) but not the disposal phase of the renovated or replaced window in the future. Figure 4 provides a graphical representation of the system boundaries for the three scenarios under investigation.

2.3.3. Impact Categories

The Environmental Footprint Method (EF 3.1) was applied for impact assessment. The following impact categories (midterm indicators) were selected: climate change, acidification, ecotoxicity, human toxicity, land use, ozone depletion, photochemical ozone formation, and resource consumption. The selected impact categories cover the relevant environmental impacts such as resource consumption, climate change, and toxicity.

2.3.4. Data Sources and Modelling Software

Background data (e.g., for electricity supply, thermal energy, float glass, etc.) were sourced from processes in the Ecoinvent database [39]. The emission factors for linseed oil were approximated using the Ecoinvent process for rapeseed oil. For linseed oil paint, emission factors from an Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) were used [40], considering only the manufacturing phase (A1–A3). Due to a lack of available data, the same emission factors for linseed oil paint were applied to linseed putty. The modeling was undertaken with the Sphera software (former Gabi, Sphera Solutions, Inc., 130 E Randolph St. 2900, Chicago, IL, US), version 2024.1.

2.3.5. Scenarios

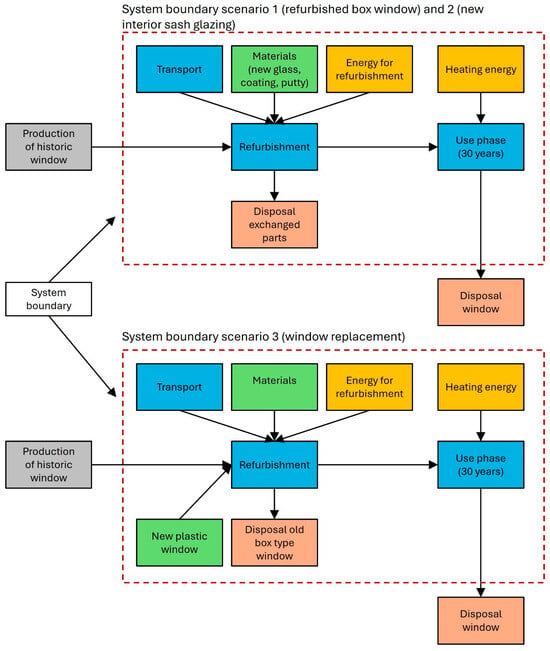

Three scenarios were analyzed (Figure 5):

Figure 5.

System boundaries (red box) of scenarios studied.

- Scenario 1, Refurbished box-type window—Minor repairs, glass replacement of a broken pane, and oil-based paint restoration.

- Scenario 2, New interior glazing—Upgrading inner glazing with low-emissivity glass (low-e glass) and sealing improvements.

- Scenario 3, full window replacement—Installing a modern plastic window with triple glazing.

Details of the life cycle phases are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Life cycle phases.

Scenario 1—Restoration of a long-unmaintained window without structural modification. This scenario assumes that the existing window (shown in Figure 3) will be reused without major interventions. To create realistic conditions, it is assumed that one glass pane (one sash field) is damaged and must be replaced. Additionally, it is assumed that the existing oil-based coating of the window can be preserved and restored through manual oil sanding, pre-oiling of the surface, and a maintenance coat. The fittings are repaired to restore full functionality, and the window structure is expected to remain in use for another 30 years.

Scenario 2—Comprehensive renovation and new interior glazing for an existing window. In this scenario, thin 3 mm low-emissivity insulating glass (k-glass) with a U-value of 3.7 W/m2K [41,42,43] is installed in the inner sash. The U-value of this window construction was calculated according to ÖNORM EN ISO 10077-1 [34]. Since the actual U-value of this window type is known from Kain et al. [18], only the U-value of the k-glass was integrated into the model as an adjusted material property. This results in a U-value of 1.80 W/m2K for the renovated window construction. In addition to replacing the inner glazing, a light wooden frame with embedded seals is installed within the window frame to improve the sealing of the inner sash layer. It is also assumed that a potentially existing synthetic resin coating over an older oil-based coating is removed using an infrared heater and manual scraping, and it is replaced with a new linseed oil coating. The fittings are professionally adjusted, and the window is assumed to remain in use for another 30 years.

Scenario 3—Installation of a new window. This scenario involves the removal of the existing window structure and the installation of a modern plastic window made from PVC with triple glazing. Unlike standard replacements, this scenario retains the original sash division (two lower casement sashes and two upper transom sashes), which increases the frame-to-glass ratio. Additionally, plastic window profiles are significantly thicker than those in historic wooden constructions. To account for this, the frame-to-glass ratio was increased by 20% compared to the original wooden window.

The U-value was again calculated according to ÖNORM EN ISO 10077-1 [34], with the following input values: frame U-value: 0.95 W/m2K, glazing U-value: 0.6 W/m2K (3-layer glass), edge seal thermal transmittance: 0.06 W/mK. This results in an overall U-value of 1.1 W/m2K for the new plastic window.

Measurements on existing insulating glass indicate that the noble gas filling dissipates over time [44]. In modern insulating glass, the positive effect of low-emissivity coatings outweighs the gas filling effect. Even when the noble gas completely escapes, the U-value of modern glazing remains at least 1.5 W/m2K [44]. For this study, the U-value of the plastic window was linearly adjusted from 1.1 to 1.5 W/m2K, resulting in an average U-value of 1.33 W/m2K over its lifetime (degradation may not be perfectly linear). A 30-year usage period was again assumed.

Additional action options, not evaluated in this study, include the installation of insulating glass (thermal or vacuum glazing) into existing or newly crafted inner sashes. The key factor for material selection is the thickness and weight of the glass, as it must fit within the existing rebate of the inner sash without increasing the rebate depth or placing excessive stress on the construction.

2.3.6. End-of-Life Modeling

In this model-based analysis, it is assumed that after 30 years, all three window options will need replacement. The old windows, including the frame structure, will be removed and disposed of. The future disposal of the window after 30 years is outside the system boundaries of this LCA, as it will take place in the future, when probably other or better treatment technologies will be available. However, the end-of-life of the replaced window or components is considered. It is worth noting that options 1 and 2 (reuse of the historic wooden double-window constructions) allow for future restoration and an additional use cycle. In contrast, modern plastic windows are rarely suitable for restoration, as brittle PVC profiles cannot be repaired [11]. Additionally, the chlorine and lead contents in plastic profiles require special waste disposal measures [45].

Regarding the end-of-life of wooden components generated during renovation, it is assumed that the wooden parts of the window are incinerated, whereby energy is recovered. The window glass from historic box-type windows is not recycled due to its unknown composition, as even minor impurities can significantly affect the quality of recycled glass [46]. Instead, the glass is landfilled. For the metal components (steel fittings), it is assumed that they end in an incineration facility together with the wooden parts; however, no energy is recovered.

2.3.7. Life Cycle Inventory

Regarding the described scenarios, input and output flows were considered according to Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 2.

Life cycle inventory for Scenario 1 (refurbished sash window).

Table 3.

Life cycle inventory for Scenario 2 (new inner sash).

Table 4.

Life cycle inventory for Scenario 3 (window change).

In the first scenario, the historical sash window is refurbished. The fittings are adjusted, and a linseed oil protective coat is applied. Additionally, a historical glass pane is replaced with a new one. The life cycle inventory (LCI) for this scenario is presented in Table 2.

In the second scenario, the glass panes in the interior sash of the historical sash window are replaced with low-e glass panes. Additionally, the interior sash receives weatherstripping. Furthermore, the old paint is removed, and a new linseed oil coating is applied. The LCI for this scenario is presented in Table 3.

In the third scenario, the historical sash window is replaced with a new plastic window. The emission factors for the plastic window were taken from an EPD [47]. Manufacturing, transportation, the use phase, and the disposal of the replaced window were considered. The LCI for this scenario is presented in Table 4.

2.3.8. Life Cycle Impact Assessment

In the life cycle impact assessment (LCIA) stage, the outcomes of the LCI are translated into different impact categories to reflect the environmental impacts of the objects studied.

3. Results

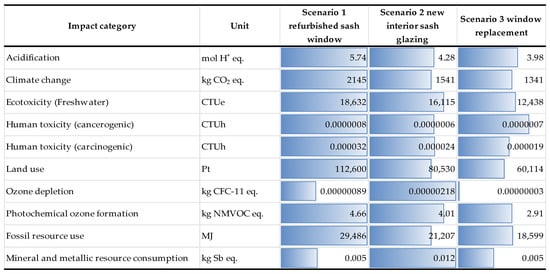

3.1. Life Cycle Impact Assessment

The results of the life cycle impact assessment for all three scenarios are presented in Figure 6. The highest values in each impact category are represented by a full bar, while the remaining values are shown with bars scaled relative to the maximum. The refurbished sash window scenario results in the highest environmental impacts in all impact categories, except for ozone depletion and mineral and metal resource consumption. For these two impact categories, the scenario with new glazing on the interior sashes achieves the worst impact assessment results. The window replacement scenario results in the lowest environmental impacts in all impact categories, with the exception of human toxicity (carcinogenic). The new glazing scenario has the lowest environmental impacts in this category. However, the results highly depend on the source of energy used for heating, which is further analyzed in the sensitivity analysis (see Section 3.2).

Figure 6.

Results of the life cycle impact assessment (EF 3.1).

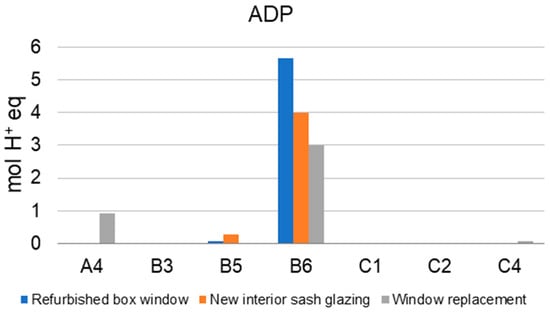

3.1.1. Acidification and Climate Change

The majority of the environmental impacts in the impact category of acidification are caused by the energy demand for space heating (B6), particularly the energy production from biomass (Figure 7). Since this is the highest in the scenario of the refurbished sash window, this scenario performs the worst in comparison. In the window replacement scenario, the energy consumption for space heating is the lowest, which is why this scenario achieves the best results for acidification. In the manufacturing phase (A4), the window replacement scenario results in the highest environmental impacts. This is due to the environmental impacts associated with the production and transport of the new plastic window. In the life cycle phase of renovation/renewal (B5), the environmental impacts of the renewed interior sash glazing are the highest. This is due to the energy and material inputs (including glass panes, linseed oil paint, putty, and seals).

Figure 7.

Life cycle impact assessment results for the impact category acidification compared by scenario and life cycle phase.

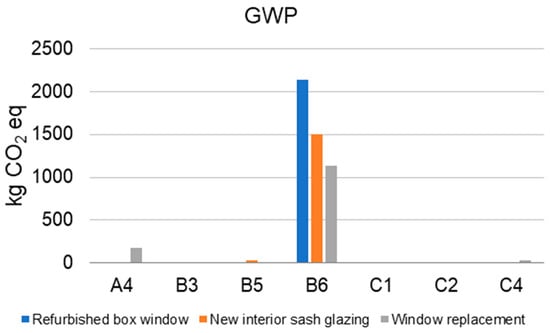

Similarly, for climate change, the majority of impacts are caused by the energy demand for space heating (B6). Among these, the highest share results from energy production using oil and gas. Since the energy consumption is highest in the scenario of the refurbished box-type window, this scenario performs the worst in comparison. In the window replacement scenario, the energy demand for space heating is the lowest, which is why this scenario achieves the best results in this impact category. The manufacturing and transportation of the new plastic window (A4) for the window replacement result in the highest impacts for this life cycle phase in the scenario comparison. The other life cycle phases contribute only minimally to the overall climate change result (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Life cycle impact assessment results for the impact category climate change compared by scenario and life cycle phase.

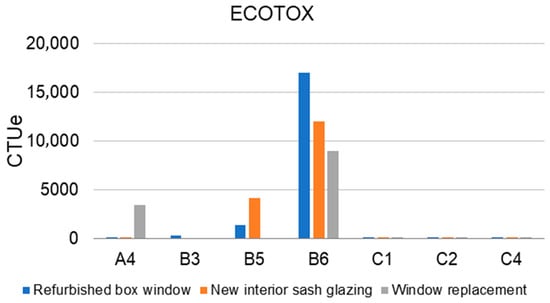

3.1.2. Ecotoxicity and Human Toxicity

Across all three scenarios, the energy demand associated with space heating (B6) represents the primary contributor to freshwater ecotoxicity (Figure 9). The predominant share of this impact stems from energy production based on fossil oil. As the scenario involving the refurbished box-type window exhibits the highest energy consumption for space heating, it consequently results in the most adverse ecotoxicity outcomes. In contrast, the window replacement scenario demonstrates the most favourable performance in this regard.

Figure 9.

Life cycle impact assessment results for the impact category freshwater ecotoxicity by scenario and life cycle phase.

During the production phase (A4), the window replacement scenario incurs the greatest environmental burdens, primarily due to the manufacturing and transportation processes of the new PVC window unit. Furthermore, owing to the material and energy inputs required for the renovation activities, the scenario involving the installation of new interior sashes registers the highest environmental impacts when compared across scenarios. The end-of-life phase contributes negligibly to the overall environmental impact within this specific impact category.

The results for the impact category human toxicity, carcinogenic, follow a similar pattern to those observed in ecotoxicity. The majority of environmental impacts originate from the energy demand for space heating (B6), particularly due to energy generation from oil. The manufacturing and transportation of the new PVC window result in the highest impacts within this category for the window replacement scenario (A4). Due to the energy and material requirements, the scenario involving new interior glazing performs worst during the life cycle stage B5. Other life cycle stages contribute only marginally to the overall environmental impacts in this category. The same coherence can be observed with regard to non-carcinogenic human toxicity, with the only difference that energy generation from biomass accounts for the majority of associated environmental impacts. The results for the impact category human toxicity, non-carcinogenic, show a very similar pattern to the impact category human toxicity, carcinogenic.

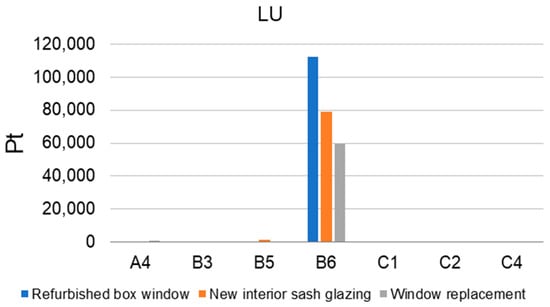

3.1.3. Land Use

In all three scenarios, the majority of land use is attributed to the energy demand for space heating (Figure 10). Biomass-based energy generation is the primary contributor in this context. Other life cycle stages contribute only marginally to the overall land use impact.

Figure 10.

Life cycle impact assessment results for land use by scenario and life cycle stage.

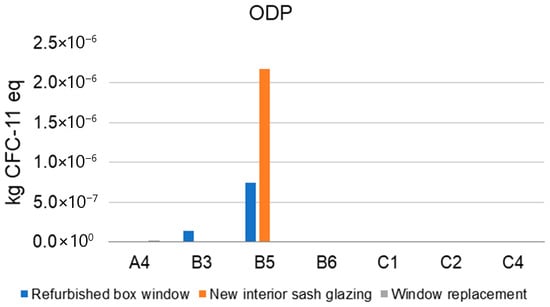

3.1.4. Ozone Depletion

The results for the impact category ozone depletion mostly originate from the life cycle phase conversion or renovation (B5). Materials used, such as linseed oil paint or linseed oil putty, are responsible for this (Figure 11). The worst performance in terms of ozone depletion is shown by the scenario involving the renovation of the inner pane glazing, while the best performance is achieved by the window replacement scenario.

Figure 11.

Life cycle impact assessment results for the impact category ozone depletion by scenario and life cycle phase.

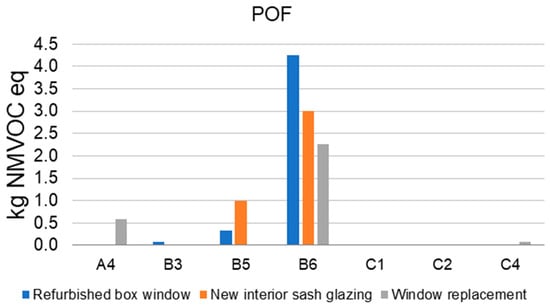

3.1.5. Photochemical Ozone Formation

The majority of photochemical ozone formation also results from the energy demand for space heating (B6), with energy generation from biomass being the main contributor (Figure 12). In the life cycle phase conversion or renovation (B5), the environmental impacts of the scenarios involving the refurbished box-type window and the renewed inner sashes are caused by the use and production of linseed oil putty and linseed oil paint. The production and transport of the new plastic window lead to the highest environmental impacts in this category for the window replacement scenario (A4). The other life cycle phases contribute only marginally to photochemical ozone formation.

Figure 12.

Life cycle impact assessment results for the impact category photochemical ozone formation by scenario and life cycle phase.

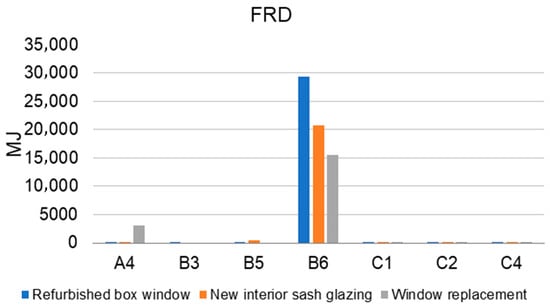

3.1.6. Fossil Resource Consumption

Fossil resource consumption mainly results from the energy demand for space heating (B6), with energy generation from gas and oil being the primary contributors (Figure 13). Due to the production and transport of the new plastic window, the window replacement scenario performs the worst in the construction phase (A4). The other life cycle phases contribute only minimally to fossil resource consumption. Overall, the refurbished box-type window scenario has the highest and the window replacement scenario the lowest fossil resource consumption.

Figure 13.

Life cycle impact assessment results for the impact category fossil resource consumption by scenario and life cycle phase.

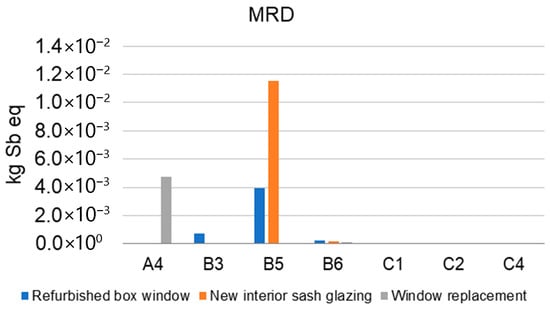

3.1.7. Mineral and Metal Resource Consumption

The majority of mineral and metal resource consumption results from the life cycle phase conversion or renovation (B5), mainly due to the use of linseed oil paint and linseed oil putty. The production and transport of the new plastic window cause the highest impacts during the construction phase (A4). The other life cycle phases contribute only minimally to mineral and metal resource consumption. The scenario involving the renewal of the inner pane glazing results in the highest, while the window replacement scenario shows the lowest mineral and metal resource consumption (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Life cycle impact assessment results for the impact category mineral and metal resource consumption by scenario and life cycle phase.

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis

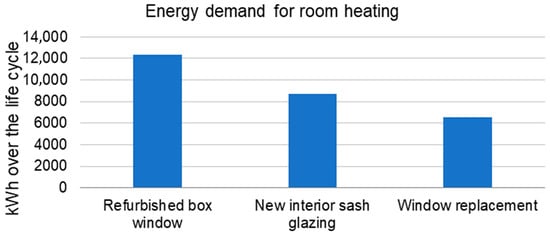

The energy demand for space heating is the main contributor to environmental impacts in all impact categories, except for ozone depletion and mineral and metal resource consumption. The refurbished box-type window scenario shows the worst results in all categories, except for ozone depletion and mineral and metal resource consumption. In all impact categories except human toxicity (carcinogenic), the window replacement scenario performs best. This is due to the significantly lower energy demand for space heating in the window replacement scenario compared to the refurbished box-type window (see Figure 15). Therefore, energy demand is a key factor influencing the environmental impacts of the three scenarios.

Figure 15.

Comparison of the energy demand for space heating over the entire life cycle (30 years) for the different scenarios.

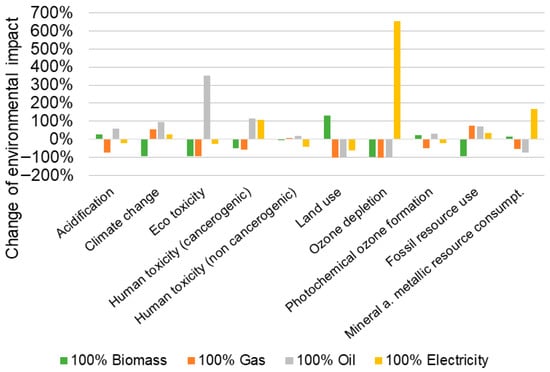

The heating mix used to provide space heating consists of 41% biomass, 26% gas, 19% oil, and 14% electricity [22]. The energy required for space heating causes the majority of environmental impacts in most impact categories. Therefore, space heating represents a key lever for reducing environmental impacts. The following subsections explain the influence of different energy sources on environmental impacts. Figure 16 shows the relative change in the environmental impacts of space heating when energy is sourced from 100% biomass, 100% gas, 100% oil, or 100% electricity (Austrian electricity mix [27]), compared to the heating mix described above and used for the modelling.

Figure 16.

Relative change in the environmental impact of room heating considering energy use from 100% biomass, gas, oil, or electricity.

A higher share of biomass in the heating mix reduces environmental impacts in the categories of climate change, ecotoxicity, human toxicity (carcinogenic), ozone depletion, and fossil resource consumption. Mahmoud et al. [48] came to similar conclusions. In terms of decarbonization and reducing fossil resource use, energy generation from biomass has advantages. However, this comes with increased land use.

A higher gas share reduces the impacts in the categories of acidification, ecotoxicity, human toxicity (carcinogenic), land use, ozone depletion, and mineral and metallic resource consumption. However, it also leads to higher environmental impacts in the categories of climate change and fossil resource use.

If more heating energy is generated from oil, the results for acidification, climate change, human toxicity (carcinogenic), and fossil resource consumption increase. Additionally, there is a particularly strong rise in ecotoxicity values. In contrast, land use, ozone depletion, and mineral and metallic resource consumption are reduced.

A higher electricity share (Austrian electricity mix) increases the results in the categories of climate change, human toxicity (carcinogenic), and fossil resource consumption, as well as mineral and metallic resource consumption. The impact category of ozone depletion shows a particularly strong increase due to the higher electricity share. However, the effects of acidification, ecotoxicity, human toxicity (non-carcinogenic), land use, and photochemical ozone formation are reduced.

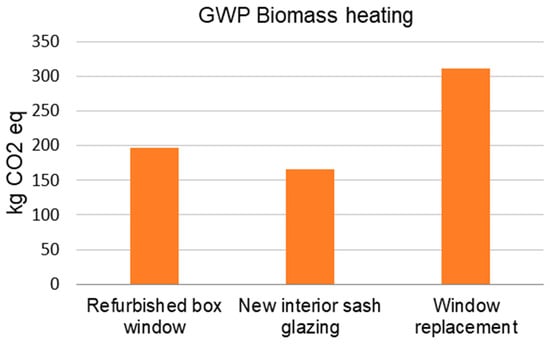

To illustrate the impact of energy sources, a hypothetical scenario was assumed in which 100% of the energy used for space heating is provided by biomass combustion. The resulting outcomes for Global Warming Potential (GWP) are shown in Figure 17. In this comparison, the manufacturing processes (A) gain importance, and under these assumptions, Scenario 2 (new inner glazing) shows the lowest environmental impact.

Figure 17.

Lowest GWP for refurbished window with low-e interior sash glazing and heating energy supplied entirely from biomass.

If the energy consumption for space heating were the same in all three scenarios, the scenario involving refurbished box-type windows would perform best in all impact categories except ozone depletion. The window replacement scenario, when excluding energy consumption for space heating, shows the worst results in all impact categories except for ecotoxicity, land use, photochemical ozone formation, and the consumption of mineral and metallic resources. In the impact category of ozone depletion, the window replacement would perform best when energy consumption is not considered. The scenario with new inner sash glazing would have the highest environmental impacts in the categories of ecotoxicity, land use, ozone depletion, photochemical ozone formation, and the consumption of mineral and metallic resources.

The environmental impacts of energy consumption can be influenced not only by the amount of energy used but also by the composition of the heating mix [49]. A higher share of biomass in the heating mix, for example, reduces environmental impacts related to climate change or the consumption of fossil resources. However, this also increases land use. A higher share of gas, oil, or electricity reduces land use but increases the environmental impacts in the categories of climate change and fossil resource consumption.

4. Discussion

The current study considers an operating time of 30 years. Life cycle assessment results are sensitive to building lifespan. It was shown that durability-based life span models improve the accuracy of LCA studies [50]. The historic box-type windows discussed in this study originate from the end of the 19th century. Maintaining them as described by Kain et al. [51] could extend their operating time by another 100 years, which would probably make the preservation of historic wooden windows compared to their exchange with PVC windows more favorable regarding life cycle costs and emissions [52]. For instance, for a whole building, it was shown that extending building life up to physical durability limits (e.g., 210 years) can cut annual CO2 emissions by up to 11% compared to typical 80-year assumptions [50].

The findings regarding the life cycle assessment of windows have to be integrated into the evaluation of whole buildings because façade insulation is more effective than glazing, although it was shown, consistent with [53], that in cold climates, the U-value of windows has a significant effect on the results of the LCA.

The finding that a window’s LCA is highly sensitive to the heating emission factor is consistent with Sällström et al. [52], who point out that higher values in this respect make window replacement more favorable. They conclude that periodically maintaining the existing windows has the lowest life cycle climate impact and cost in most scenarios, and replacement only becomes preferable under specific conditions, such as very high heating emission factors, poor thermal performance of existing windows, and very long building service life (>75 years).

Further studies will have to focus on life cycle cost analysis of the presented options regarding window renovation or replacement. While this analysis is highly affected by the intensity of renovation work with historic windows, the price for new windows, and energy prices, it has to be noted that the life cycle of historic windows can be extended to more than a century by relatively simple measures, making this option worth consideration.

Another aspect of the current study is the fact that a box-type window is a complex system, and its replacement by an insulated glazing window might result in disadvantageous building physical coherences. For instance, the comparatively large construction depth of a box-type window results in a stretched isotherm curve [51] beneficial for mold prevention. Also, the increased air tightness of retrofitted buildings could go along with reduced indoor air quality [17], especially in combination with faulty ventilation behaviour [54]. Additionally, especially in older buildings with higher moisture levels, a reduced air exchange rate could go along with air hygiene problems and mold [21]. Therefore, the current study has to be considered together with other quality parameters of building characteristics.

5. Conclusions

This study describes how the condition of historic windows can be systematically assessed and outlines the resulting options for window renovation. Well-preserved box-type window constructions can be renovated using traditional, minimally invasive methods and then achieve a U-value (depending on construction) in the range of 2.0–2.5 W/m2K. If higher insulation performance is required, replacing the inner glazing and using low-emissivity glass (K-glass) is an option, which can reduce the U-value to approximately 1.8 W/m2K. Alternatively, the historic construction can be removed and replaced with a modern, insulated single window, which, depending on execution quality, can achieve an average U-value around 1.3 W/m2K over the life cycle. However, this approach results in the loss of the cultural value of the historic appearance.

The environmental impact of the three selected scenarios shows relatively consistent results across most impact categories: the “window replacement” scenario, where a new, better-insulated window replaces a historic one, shows the lowest environmental impact. This is due to the lower energy demand for space heating with the new window. Over a 30-year evaluation period, the energy required for space heating has a greater impact than the manufacturing and disposal processes and, therefore, dominates the overall result. A sensitivity analysis was conducted by varying the energy sources used for space heating. Assuming the use of biomass heating, the ranking changes, and in this case, the “new inner glazing” scenario proves most advantageous in terms of environmental impact.

Although the refurbishment of the historic box-type window yields the least favorable results in this LCA compared to the other scenarios, it should be emphasized that historic windows possess significant cultural–historical value (Figure 18). Fractal patterns, often perceived as beautiful by most individuals [54], are particularly discernible in historical windows [55]. The large form of the window frame is reflected on the next fractal level in the window sashes, which are further subdivided into a smaller fractal structure through muntin divisions. In historical windows where glass panes are additionally segmented by lead cames, this fractal refinement extends one level further [56]. However, this cultural–historical value cannot be measured with the tools of an LCA and is, therefore, not accounted for in a life cycle analysis.

Figure 18.

Basement windows of a late 19th-century Viennese building: left, the original wooden box-type window with fine wing cross-sections; right, a plastic replacement lacking the elegance of the historic model.

The willingness to make substantial initial investments in energy-efficient buildings with the aim of reducing long-term operating costs is a recent phenomenon. However, the life cycle of modern building materials is often overestimated, casting doubt on the economic viability of such investments. In this context, the integration of heritage conservation and environmental protection offers a sustainable alternative: the reuse of existing buildings and building components, such as box-type windows, not only reduces the ecological footprint but also preserves cultural values.

Enhancing collaboration between researchers in heritage conservation and environmental protection presents a significant challenge. Nevertheless, interdisciplinary projects that unite both perspectives could foster innovative solutions that ensure both ecological and cultural sustainability.

The two fields are closely linked by their conservative foundations and shared objective of preserving existing structures. Built heritage, as the most resource- and energy-intensive component of cultural heritage, plays a key role in this regard. Evolutionary processes, economic conditions, and cultural notions of authenticity shape the strategies of both disciplines. Closer collaboration between heritage conservation and environmental protection offers the potential to develop sustainable solutions that safeguard both the natural and cultural environment. Projects that integrate the standards and principles of both fields may provide a pioneering contribution to the preservation of our heritage.

Based on the findings of the current paper, we recommend enhancing the thermal performance of historic box-type windows through heritage-compatible measures to reduce heat loss. The greener the energy used for space heating, the stronger the arguments become for conserving historic box-type windows—ecologically, and in terms of heritage protection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.K., F.I. and S.S.; methodology, S.S.; software, N.B.; validation, G.K., F.I. and S.S.; formal analysis, N.B.; investigation, G.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.K.; writing—review and editing, F.I. and S.S.; visualization, N.B.; supervision, S.S.; project administration, S.S.; funding acquisition, G.K. and F.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Austrian Federal Ministry for Housing, Arts, Culture, Media, and Sport and by ICOMOS Austria.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| PVC | Polyvinyl Chloride |

| LCI | Life Cycle Inventory |

| ADP | Acidification Potential |

| ECOTOX | Ecotoxicity |

| LU | Land Use |

| ODP | Ozone Depletion Potential |

| POF | Photochemical Ozone Formation |

| FRD | Fossil Resource Depletion |

| MRD | Mineral Resource Depletion |

References

- Guidetti, E.; Ferrara, M. Embodied energy in existing buildings as a tool for sustainable intervention on urban heritage. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 88, 104284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronin, S.C. Aligning Historic Preservation and Energy Efficiency: Legal Reforms to Support the Greenest Buildings; University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bullen, P.A.; Love, P.E. Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings. Struct. Surv. 2011, 29, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, A. Does demolition or refurbishment of old and inefficient homes help to increase our environmental, social and economic viability? Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4487–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouseki, K.; Cassar, M. Energy Efficiency in Heritage Buildings—Future Challenges and Research Needs. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2014, 5, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandl, D.; Mach, T.; Grobbauer, M.; Ruisinger, U.; Hochenauer, C. Analysis of the thermal behavior of historical box type windows for renovation concepts with CFD. In Sustainable Buildings-Construction Products & Technologies Proceedings of the Sustainable Building Conference 2013, Graz University of Technology, Austria, 25–28 September 2013; Höfler, K., Maydl, P., Passer, A., Eds.; Verlag der Technischen Universität Graz: Graz, Austria, 2013; ISBN 9783851252996. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesdenkmalamt. Rechtskräftig unter Denkmalschutz Stehende Unbewegliche Objekte im Jahr 2023—Auswertung aus der Denkmaldatenbank (HERIS). Available online: https://www.bda.gv.at/ueber-uns/zahlen-daten-fakten.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Statistik Austria. Gebäudebestand-Baualtersstruktur. Available online: https://www.statistik.at/statistiken/bevoelkerung-und-soziales/wohnen/gebaeudebestand (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Rexroth, S.; Mertes, A.; Thurow, K.; Rexroth, S.; Mertes, A.; Thurow, K. Verglasungssysteme Für Fenstersanierungen Im Berliner Gebäudebestand-Energie, CO2 Und Wirtschaftlichkeit Im Einklang—Teil 1: Zusammenfassung Der Energetischen Betrachtungen; Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft (HTW) Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolucci, B.; Frasca, F.; Flores-Colen, I.; Bertolin, C.; Siani, A.M. Key Performance Indicators: Their use in the energy efficiency retrofit for historic buildings. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2024, 55, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, S.; Friedlander, E. The influence of durability and recycling on life cycle impacts of window frame assemblies. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 1645–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litti, G.; Audenaert, A.; Lavagna, M. Life cycle operating energy saving from windows retrofitting in heritage buildings accounting for technical performance decay. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 17, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coillot, M.; El Mankibi, M.; Cantin, R. Heating, ventilating and cooling impacts of double windows on historic buildings in Mediterranean area. Energy Procedia 2017, 133, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuk, H.; Choi, J.Y.; Yang, S.; Kim, S. Balancing preservation and utilization: Window retrofit strategy for energy efficiency in historic modern building. Build. Environ. 2024, 259, 111648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnaggar, A. Nine principles of green heritage science: Life cycle assessment as a tool enabling green transformation. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.; Bordass, B.; Baker, P. Research into the Thermal Performance of Traditional Windows: Timber Sash Windows; Historic England: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pampuri, L.; Caputo, P.; Valsangiacomo, C. Effects of buildings’ refurbishment on indoor air quality. Results of a wide survey on radon concentrations before and after energy retrofit interventions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 42, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kain, G.; Idam, F.; Hunger, P.; Bonfert, S. Die Dämmwirkung von Kastenfenstern—Untersuchungen am Prüfstand und in der Praxis. Bauphysik 2024, 46, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuce, E. Role of airtightness in energy loss from windows: Experimental results from in-situ tests. Energy Build. 2017, 139, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehle, B.; Geyer, C.; Hernandez, A. Schall-und Luftdichtheit von Fenstern in der Renovation. In 10. HolzbauSpezial Bauphysik & Gebäudetechnik; Forum Holzbau: Frasdorf, Germany, 2019; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bichlmair, S.; Krus, M.; Milch, C. Energetische Fenstersanierung im Altbau und Denkmal—Hygrothermische Aspekte am Kastenfenster. In Denkmal und Energie 2021; Weller, B., Scheuring, L., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021; pp. 205–217. ISBN 978-3-658-32247-2. [Google Scholar]

- Souviron, J.; van Moeseke, G.; Khan, A.Z. Analysing the environmental impact of windows: A review. Build. Environ. 2019, 161, 106268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citherlet, S.; Di Guglielmo, F.; Gay, J.-B. Window and advanced glazing systems life cycle assessment. Energy Build. 2000, 32, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, S.O.; Oyedele, L.O.; Ilori, O.M. Changing significance of embodied energy: A comparative study of material specifications and building energy sources. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 23, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Aluminium. Circular Aluminium Action Plan: A Strategy for Achieving Aluminium’s Full Potential for Circular Economy by 2030. Available online: https://european-aluminium.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/european-aluminium-circular-aluminium-action-plan.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Asdrubali, F.; Roncone, M.; Grazieschi, G. Embodied Energy and Embodied GWP of Windows: A Critical Review. Energies 2021, 14, 3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sphera Solutions GmbH. PBP-GaBi Software System; University of Stuttgart: Leinfelden-Echterdingen, Gemany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Plastics Europe. Building and Construction. Available online: https://plasticseurope.org/plastics-explained/plastics-in-use/building-and-construction/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Stichnothe, H.; Azapagic, A. Life cycle assessment of recycling PVC window frames. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 71, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giovanni, G.; Laurini, E. Sustainable Procedures for the Recycling of Waste Building Materials: The Creative Recycling of Window Frames. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.W.; Eames, P.C.; Lo, S.N.; Norton, B. Energy and environmental life-cycle analysis of advanced windows. Renew. Energy 1996, 8, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzałka-Rogal, D. Historical windows and their impact on the energy balance of the building. Architectus 2024, 2, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kain, G.; Gschwandtner, F.; Idam, F. Der Wärmedurchgang bei Doppelfenstern—Konzept zur In-situ-Bewertung historischer Konstruktionen. Bauphysik 2017, 39, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ÖNORM EN ISO 10077-1; Wärmetechnisches Verhalten von Fenstern. Türen und Abschlüssen—Berechnung des Wärmedurchgangskoeffizienten—Teil 1: Allgemeines. Austrian Standards: Vienna, Austria, 2020.

- Formayer, H.; Leidinger, D.; Nadeem, I. Klimaszenarien für das 21. Jahrhundert in Oberösterreich. Available online: https://www.doris.at/themen/umwelt/pdf/clairisa/coin/Methodik_Klimaszenarien.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Statistik Austria. Energieeinsatz Der Haushalte. Available online: https://www.statistik.at/statistiken/energie-und-umwelt/energie/energieeinsatz-der-haushalte (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Austrian Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs, Energy and Tourism. Where Does Austrian’s Electricity Come From? Available online: https://energie.gv.at/versorgung/woher-kommt-oesterreichs-strom (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- ÖNORM EN ISO 14040; Environmental Management-Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. Austrian Standards International: Vienna, Austria, 2021.

- Wernet, G.; Bauer, C.; Steubing, B.; Reinhard, J.; Moreno-Ruiz, E.; Weidema, B. The ecoinvent database version 3 (part I): Overview and methodology. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPDDENMARK. EPD 1 Liter 84/Ordkløveri Outdoor Linseed Oil Paint. Available online: https://www.epddanmark.dk/media/0yedbvoa/md-23213-en.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Zach, S. Glasqualitäten für die Restaurierung historischer Kastenfenster [E-Mail]. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Eichendorf, M. Sanierung und Reparatur-4 mm K Glas. Available online: https://www.der-fenstersanierer.de/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Glaswelt. Denkmalschutz als Stufenlösung. Renovation von Verbund- und Kastenfenstern. Glaswelt 1997, 11, 62–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kain, G.; Idam, F. Report on Building Physics Issues in Historic Windows: Developed in cooperation with the Committee ‘Historic Buildings’ of the Chamber of Architects and Consulting Engineers for Vienna, Lower Austria, and Burgenland. 2023; (unpublished, available upon request from the authors). [Google Scholar]

- Miliute-Plepiene, J.; Fråne, A.; Almasi, A.M. Overview of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) waste management practices in the Nordic countries. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 4, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewello, R.; Kilian, R.; Bichlmair, S.; Milch, C.; Lenz, K.; Fischer, M. Leitfaden zur Energetischen Ertüchtigung von Bestandsfenstern und Gläsern in Historischer Bausubstanz als Beitrag zum Klimaschutz. Available online: https://www.denkmalpflege.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/ibp/denkmalpflege/de/4Wissensammelnundvermitteln/43_Mediathek/421_Informationsmaterial/2021-05-31_KlimaGlas_Leitfaden_final.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- BMWSB. ÖKOBAUDAT-Informationsportal Nachhaltiges Bauen. Available online: https://www.oekobaudat.de/ (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Mahmoud, M.; Ramadan, M.; Naher, S.; Pullen, K.; Olabi, A.-G. The impacts of different heating systems on the environment: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 766, 142625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, C.; Schalbart, P.; Assoumou, E.; Peuportier, B. Integrating climate change and energy mix scenarios in LCA of buildings and districts. Appl. Energy 2016, 184, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Munoz, B.; Peuportier, B.; Gracia-Villa, L.; López-Mesa, B. Sustainability assessment of refurbishment vs. new constructions by means of LCA and durability-based estimations of buildings lifespans: A new approach. Build. Environ. 2019, 160, 106203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kain, G.; Scheck, P.; Idam, F. Kastenfenster mit isolierverglastem Innenflügel-hygrothermische Zusammenhänge. Bauphysik 2025, 47, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sällström Eriksson, L.; Lidelöw, S. Maintaining or replacing a building’s windows: A comparative life cycle study. IJBPA 2024, 43, 766–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushar, Q.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Zhang, G. Energy simulation and modeling for window system: A comparative study of life cycle assessment and life cycle costing. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-S.; Kang, D.-H.; Choi, D.-H.; Yeo, M.-S.; Kim, K.-W. Comparison of strategies to improve indoor air quality at the pre-occupancy stage in new apartment buildings. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, W.E.; Andres, J.; Frank, G. Fractal Aesthetics in Architecture. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. 2017, 11, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space, 1st ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; ISBN 9781610910231. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).