Abstract

The tensile strength of stabilized clayey soil is a key indicator of its resistance to cracking and directly governs its performance when used as subgrade fill. In this study, ordinary Portland cement and polyacrylate-based super-absorbent polymers (SAP) were combined to stabilize four typical high-water content clayey soils sourced from Northern Bavaria. The optimal SAP content was determined based on absorption capacity by the tea-bag method. Subsequently, the effects of cement content and curing period on the Brazilian tensile strength (BTS) of clayey soils were investigated, and the correlation between Brazilian tensile strength and unconfined compressive strength (UCS) was discussed. The results indicated the following: the optimal SAP content was 0.3%; the BTS increased significantly with higher cement content and a longer curing period; the failure modes of BTS specimens were revealed, including multiple non-through fracture, non-central fracture, and central fracture; a strong linear correlation was established between BTS and UCS, with the proportional coefficient ranging from 0.129 to 0.233. The findings of this study can provide a valuable reference for the design and application of cement-SAP stabilized soils in practical engineering.

1. Introduction

The utilization of high-water content clayey soils in geotechnical engineering, such as in backfilling, embankment construction, and land reclamation, is often hindered by their inherently poor engineering properties [1,2]. These soils characteristically demonstrate low strength, high compressibility, and significant susceptibility to volume alteration upon desiccation or hydration. These characteristics present notable challenges to the safety and long-term stability of engineering structures, commonly requiring soil improvement or replacement [3,4,5].

Cement stabilization is a well-established technique to improve the mechanical characteristics of soft soils [2,6,7,8]. Cement enhances strength and stiffness, and reduces the compressibility of stabilized soil by inducing hydration and pozzolanic reactions [9,10]. However, soils with exceptionally high water content are hard to be stabilized. Excessive water dilutes the cement, diminishing reaction efficiency, weakening strength, and lowering matrix density [7,11,12]. This often necessitates increased cement consumption to satisfy design specifications, thereby raising project costs and exacerbating environmental concerns due to the high carbon footprint of cement production [13,14,15]. This is particularly critical given that cement production is a major source of anthropogenic CO2, with the global average emission ranging from 0.8 to 0.9 tons of CO2 per ton of cement produced [16,17]. Hence, additional materials should be added to supplement the cement in order to eliminate this adverse effect.

Super-absorbent polymers have been extensively utilized as safe and non-toxic materials in various fields, including hygiene, bio-medicine and agriculture [18]. Recently, super-absorbent polymers have emerged as a potential additive for soil improvement [19,20,21]. These hydrophilic polymers can absorb and retain hundreds of times their own mass in water [22,23], potentially mitigating the adverse effects of excess water in cement–soil mixtures. Scholars hypothesized that the incorporation of SAP serves two primary functions: firstly, by instantly absorbing free water, SAP reduces the effective water–cement ratio at the micro-scale, promoting more efficient cement hydration; secondly, SAP acts as an internal curing agent, slowly releasing water to support prolonged hydration, thereby reducing shrinkage cracks and potentially modifying the soil’s fabric for improved toughness [24,25,26,27,28].

Bian et al. [12,29] investigated the compression behavior of cement-stabilized dredged clay at high water content with SAP. It was concluded through microstructural analysis that the strength enhancement of cement–SAP stabilized clay is primarily due to a denser fabric with less interaggregate pores. Dai et al. found that SAP can effectively improve the strength and the compaction of cemented excavated soil with good durability [30]. Through a series of experiments, Luo et al. concluded that SAP incorporation did not alter the chemical functional groups or mineral composition of loess, but triggered water redistribution, thereby modifying its mechanical properties [31]. Despite these studies having provided some understanding of the compressibility and unconfined compressive strength of SAP stabilized soils, relatively little research has been conducted on its tensile strength, a key parameter governing cracking and failure.

In geotechnical applications such as embankment slopes, landfill cover layers, and seismic design, tensile cracking compromises structural integrity and leads to failure [32,33,34]. The Brazilian tensile strength test provides an indirect and reliable method for determining the tensile strength of brittle materials like rock, concrete, and stabilized soils [35,36,37,38]. Therefore, this study aims to systematically investigate the Brazilian tensile strength of high water content clayey soils stabilized with cement and superabsorbent polymers. It is attempted to evaluate the effects of cement content, SAP content, as well as curing periods, on the tensile properties of stabilized soils through comparative analysis of failure modes. Additionally, a correlation between Brazilian tensile strength and unconfined compressive strength is established to enable strength prediction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Program

This experimental program was divided into three stages. The first stage involved conducting characterization tests of clayey soils to obtain the specific gravity of clayey soils in accordance with ASTM D854-14 [39], Atterberg limits in agreement with ASTM D4318-17 [40], and grain size distribution curves in accordance with ASTM D7928-17 [41]. The mineral compositions of clayey soils were determined by X-ray diffraction analysis. The second stage employed the tea-bag method to determine the absorption capacity of super-absorbent polymers in the intended liquid. The third stage consisted of molding, curing, and rupture of the specimens subjected to Brazilian tensile tests as outlined in ASTM D3967-16 [42].

2.2. Materials

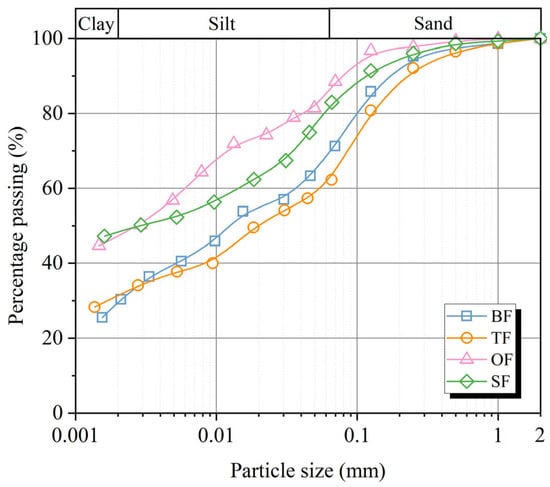

Four different types of clayey soils used in this study were collected from Upper Triassic to Middle Jurassic formations in Northern Bavaria of Germany. These formations are found to be the most problematic building sites. The basic physical properties of row clayey soils are summarized in Table 1. According to the Unified Soil Classification System, these clayey soils, designated as Benk-Formation Clay (BF), Trossingen-Formation Clay (TF), and Sengenthal-Formation Clay (SF), can be classified as low plasticity clay (CL), while Opalinuston-Formation Clay (OF) can be regarded as high plasticity clay (CH). The grain size distribution of clayey soils is illustrated in Figure 1. The clay fraction refers specifically to the percentage of particles finer than 0.002 mm, as determined by hydrometer analysis. It indicated that clay fraction of BF, TF, OF, and SF is 29.4%, 31.2%, 47.3%, and 48.4%, respectively. Furthermore, Table 2 shows the main mineral compositions of clayey soils, with kaolinite and musco/illite being the predominant clay minerals. The clay minerals fraction of BF, TF, OF, and SF is 44%, 43%, 74%, and 61%, respectively.

Table 1.

Basic physical properties of clayey soils.

Figure 1.

Grain size distribution of clayey soils.

Table 2.

Main mineral compositions of clayey soils.

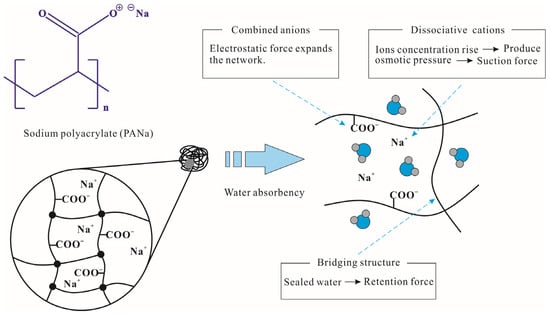

Two stabilizers, cement and super-absorbent polymers, were used in this study. The type of cement was ordinary Portland cement (CEM I 42.5N) produced by SCHWENK Building Materials Group in Ulm, Germany. The initial and final setting times of the cement were 15 min and 60 min, respectively. The compressive strength of the cement can reach 10 MPa in 2 days and can exceed 42.5 MPa after 28 days. Super-absorbent polymers used in this study was a type of absorbent gel produced by SCHAUCH group in Lauffen, Germany. Its main component was sodium polyacrylate with a dry-bulk density of about 0.8 g/cm3. In the dry state, a diameter of 0.1 mm to 0.2 mm was measured for the particles, while after water was absorbed, an expansion in volume of 3 to 5 times of their original size can be undergone by the particles. As shown in Figure 2, sodium polyacrylate achieves absorption through a triple action mechanism: combining anions, dissociating cations, and forming bridging structures. It absorbs water through osmotic pressure generated by its ions and locks water molecules within a three-dimensional cross-linked network. In this study, the dry sodium polyacrylate particles had the capacity to soak up about 850 times their own mass of distilled water.

Figure 2.

Absorption mechanism of sodium polyacrylate.

2.3. Specimen Preparation

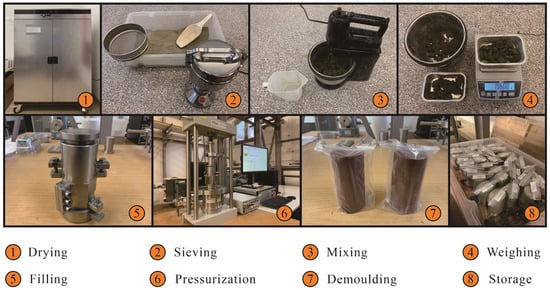

The process of specimen preparation can be described as follows, shown in Figure 3. Clayey soils were first dried in a heating chamber at a temperature of 60 ± 3 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, they were ground into powder using a mill and sieved through a 2 mm mesh. As listed in Table 3, the quantities of stabilizers were calculated and weighted by the mass of dry soil and mixed thoroughly in a domestic mixer. Water was then added and mixed with the dry material to produce a homogeneous mixture. By mixing the specimens at their liquid limit (LL), a uniform and high initial water content was achieved. The mixing process was restricted to 10 min to avoid hardening of the mixture. The specimens were made by compacting the mixture into two layers in a standard mold with 50 mm in inside diameter and 100 mm in length. After demolding, all cylindrical specimens were wrapped in plastic bags separately and placed in a curing chamber (20 ± 2 °C and 95% relative humidity) for 7, 28, and 90 days. To ensure reliability, three equivalent specimens were prepared for each test, and the average of the test output was documented with error bars.

Figure 3.

Specimen preparation process.

Table 3.

Mixture design of stabilized clayey soils.

2.4. Filter Pressing and Absorption Capacity Test

According to previous studies [43,44], free water can be obtained from the clayey soil sample by applying 8 to 10 atmospheres of pressure. In this study, a loading apparatus was used to apply a constant pressure of 1.0 MPa to soil samples at liquid limit state. Pore solutions were squeezed out of the soil samples, filtered and used for the absorption capacity test.

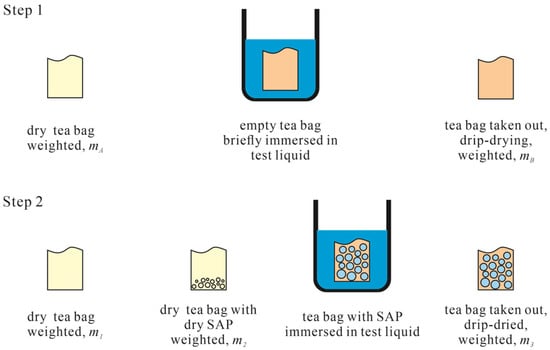

The function of super-absorbent polymers is to absorb a portion of free water, thereby ensuring that cement can effectively fulfill its binding role. Numerous studies [45,46,47] found that the tea-bag method was an effective experimental approach for quantifying the absorption properties of pore solutions in cementitious materials across various types of SAP. As shown in Figure 4, the tea-bag method is divided into two steps: calibrating the tea bags’ absorption capacity and measuring the SAP’s absorption capacity. The tea bags used were GRIRIW brand, dimensioned 55 mm (width) × 70 mm (length), and made of non-woven fabric. In the initial phase, each of the minimum ten (n ≥ 10) empty dry tea bags were weighted, and the mass was recorded as mA. The excess liquid was then gently wiped off the wet tea bags after brief immersion, and the mass was measured as mB. The mass of liquid absorbed by tea bags, m0, was calculated by Equation (1) to obtain the average value. In the latter phase, a dry tea bag was weighted as m1. Then, it was filled with approximately 0.1 g (with an accuracy of 0.0001 g) of dry SAP particles and the mass was measured as m2. The filled tea bag was suspended in a beaker containing about 200 mL of the target pore solution. The beaker was sealed with a plastic film to prevent carbonation and evaporation losses. The test was conducted at room temperature. After 60 min, equilibrium was reached. The tea bag with hydrogel was extracted and its mass measured as m3. The absorption capacity of SAP was calculated using Equation (2). To ensure accuracy, three independent tea bags should be prepared for each group of SAP samples and squeezing these samples should be avoided during testing.

where m0 is the average absorption of the tea bag in g, mA is the mass of a dry tea bag in g, mB is the mass of a wet tea-bag in g, m1 is the mass of a dry tea bag in g, m2 is the mass of a tea bag with dry SAP particles in g, m3 is the mass of a tea bag with hydrogel in g, and ASAP is the absorption capacity of SAP in g/g.

Figure 4.

Procedures for tea-bag method.

2.5. Brazilian Tensile Strength Test

In this study, the tensile strength of stabilized clayey soils was obtained through an indirect method, the Brazilian tensile strength test. It involved applying a radial load to a cylindrical specimen, which induces a uniform tensile stress vertical to the applied load. The specimen fractures when the internal tensile stress exceeds its own strength. The Brazilian tensile strength of stabilized clayey soils can be calculated as follows.

where σt is the Brazilian tensile strength of the stabilized clayey soil specimen in MPa; P is the failure load in kN; D is the diameter of the specimen in mm; and L is the length of the specimen in mm.

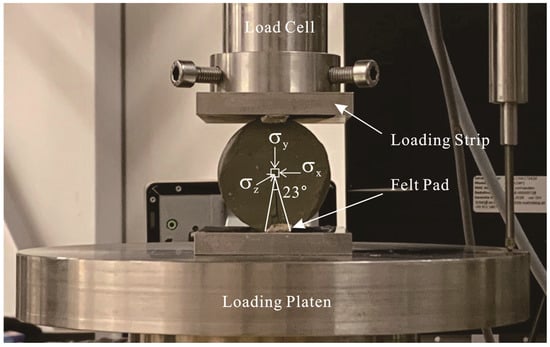

Compared to ASTM D3967-16, this study incorporated several modifications to the experimental apparatus and procedures. Figure 5 illustrates the overall view of the Brazilian tensile strength test. The stabilized specimen was placed at the center of the loading platen. A load cell was installed at the top of the experimental apparatus to measure the axial load applied to the specimen. Two felt pads were placed between the loading strips and the specimen to help distribute the load more evenly, prevent stress concentrations, and ensure a more valid, uniform tensile failure occurring at the center of the specimen. Based on extensive laboratory experiments and numerical simulations, scholars [48,49,50] recommended employing a loading angle (2α) of 20° to 30° to ensure the validity of tensile test results. Hence, the width of used felt pads was 10 mm, which gave a loading angle of 23°. The introduced error is less than 3%, which is considered acceptable in engineering applications, especially when compared to material variability. The Brazilian tensile strength was tested under a vertical load at a constant displacement rate of 1.0 mm/min.

Figure 5.

Detailed view of the specimen and experimental apparatus.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Determining Super-Absorbent Polymer Content

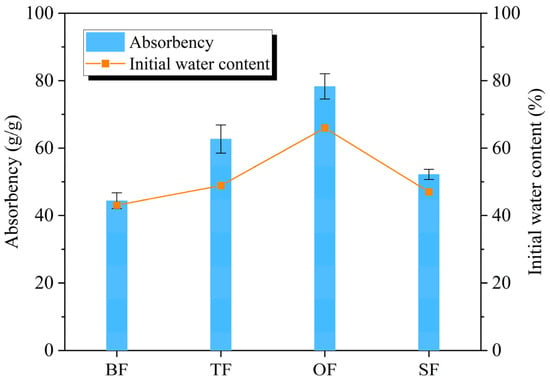

Due to the incorporation of SAP in clayey soils, a proportion of water is absorbed by SAP, while the residual portion partakes in the hydration reaction of cement. As shown in Figure 6, the absorption capacity of SAP for the filtrated pore solutions of four types of clayey soils, BF, TF, OF and SF, were 44.4 g/g, 62.7 g/g, 78.3 g/g and 52.2 g/g, respectively. Correspondingly, the initial water contents of these soils were 43.1%, 48.9%, 55.0% and 47.0%, respectively. Previous studies adopted water–cement ratios (as listed in Table 4) to stabilize high water content soils, aiming to minimize cement consumption while ensuring effective cement action. Accordingly, this study identified a 0.3% SAP content as optimal for stabilizing the clayey soils. In this case, SAP can theoretically absorb 13.3%, 18.8%, 23.5%, and 15.7% water for BF, TF, OF, and SF, respectively. This implies that the effective water–cement ratio for stabilized soils is reduced to a range of 1.0 to 4.3.

Figure 6.

Absorbency of super-absorbent polymers and variation in specimen water content.

Table 4.

Summary of studies on the water–cement ratio of cement-stabilized soils.

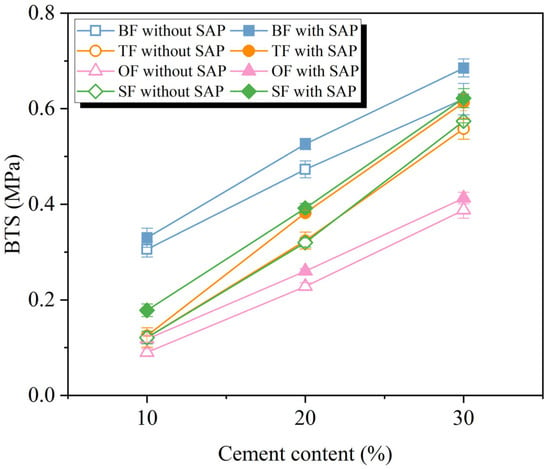

3.2. Effect of Cement Content on Brazilian Tensile Strength

Figure 7 shows the variation in 7-day Brazilian tensile strength of clayey soils with cement and super-absorbent polymers. The prominent trend for four types of clayey soils, with or without SAP, was the near-linear and substantial increase in BTS as the cement content rises from 10% to 30%. The curves for specimens containing SAP were higher than those for specimens without SAP at the same cement content. For the clayey soil named BF, the BTS increases from 0.31 MPa at 10% cement, to 0.47 MPa at 20%, and reached 0.62 MPa. On this basis, SAP can further enhance the strength. Compared to specimens without SAP admixture, under the same cement content, the BTS values of SAP-stabilized clayey soils increased by 0.05 MPa, 0.06 MPa, 0.03 MPa, and 0.06 MPa for BF, TF, OF, and SF, respectively. This demonstrates that the cementitious compounds formed during hydration are the primary contributors to strength development, and SAP can provide benefits to the performance of cement. However, the effectiveness of this enhancement is highly dependent on the soil type. The combination of cement and SAP is an effective strategy for BF, TF and SF, whereas for OF, the stabilization effect is not remarkable.

Figure 7.

BTS of clayey soils with different cement contents.

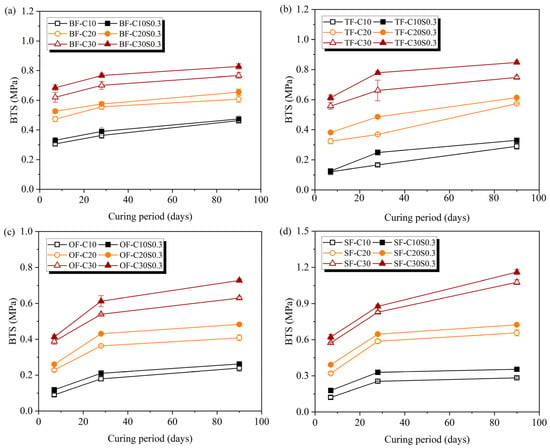

3.3. Effect of Curing Period on Brazilian Tensile Strength

Figure 8a–d illustrates the variation in BTS versus curing period for clayey soils, BF, TF, OF and SF, with different stabilizer additions. The Brazilian tensile strength of clayey soils exhibits a non-linear growth pattern, characterized by a rapid initial increase followed by a gradual deceleration in growth rate. For specimens with 0.3% SAP, polymers not only provide a one-time boost in the early stage but also make a sustained contribution to long-term strength. This effect is more significant in specimens with high cement content. Taking OF-C30 and OF-C30S0.3 as examples, stabilized soil with SAP improves its 7-day, 28-day, and 90-day BTS by 6.4%, 13.5%, and 15.6%, respectively, compared to stabilized soil without SAP. This is primarily due to the effectiveness of SAP’s “internal curing” mechanism. During the mixing stage, it absorbs free water, which is then gradually released as internal humidity decreases due to cement hydration. This promotes the continuous reactions of cement, particularly for cement particles tightly enclosed within the matrix. This mechanism enhances the early strength of the specimen and can achieve significant strength growth in the later stages, thereby preventing reaction stagnation caused by internal drying.

Figure 8.

BTS of stabilized clayey soils with different curing periods: (a) BF; (b) TF; (c) OF; (d) SF.

3.4. Failure Modes of Stabilized Clayey Soils

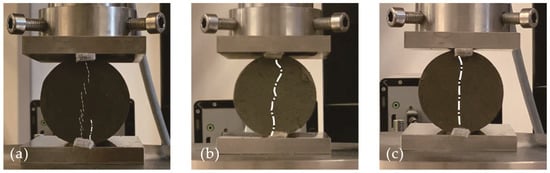

The various failure modes in the Brazilian tensile strength tests for rocks have been extensively documented [54]. The central fracture is recognized as the most classical and ideal failure mode, serving as an indicator of a valid test. However, due to the influence of inherent structural planes such as joints and fissures, as well as other internal defects within the rock mass, non-ideal failure modes, including non-central fracture and layer activation, also frequently occur. In contrast, studies on the failure modes and underlying mechanisms of cement-stabilized clayey soils in such tests remain notably underdeveloped. Figure 9a–c present three typical failure modes of stabilized clayey soils, namely multiple non-through fracture, non-central fracture and central fracture.

Figure 9.

Typical failure modes of stabilized clayey soil specimens: (a) multiple non-through fracture, (b) non-central fracture, (c) central fracture.

- Multiple non-through fracture: two or more macro-cracks appear on the specimen, but none of them fully penetrates its entire diameter. These cracks propagate between the upper and lower points, forming intersections and branches. Ultimately, the specimen remains intact, not separating completely into two pieces. The crack network may appear complex and disordered.

- Non-central fracture: the specimen splits into two halves by a primary through-crack, but the crack path deviated significantly from the specimen’s geometric center. The crack appears curved or inclined, yet its overall direction generally aligns with the loading direction. The two resulting fragments are unequal in size.

- Central fracture: the specimen splits into two symmetrical semicircular disks. A single, straight, and clearly visible macro-crack propagates along a path diametrically aligned with the loading direction, completely penetrating the entire thickness of the specimen. The crack’s origin and termination points typically correspond precisely to the contact points between the upper and lower felt pads and the specimen, or directly beneath them.

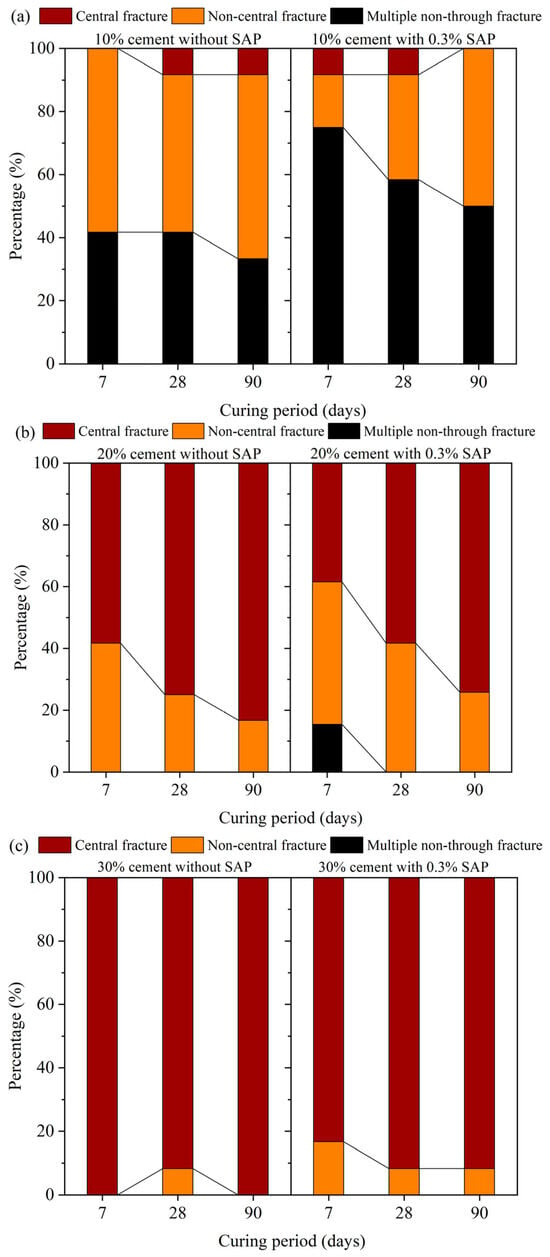

As shown in Figure 10a–c, the influence of cement content, SAP and curing period on the failure modes of stabilized clayey soils can be observed. The proportion of the central fracture rose significantly as the cement content increased. At 10% cement content, multiple non-through fracture and non-central fracture accounted for a considerable proportion, whereas at 30% cement content, central fractures became dominant. Additionally, the proportion of central fracture increased with an extended curing period (from 7 to 90 days), while the percentages of multiple non-through fracture and non-central fracture decreased. Compared to specimens without SAP, specimens with SAP actually have an increased proportion of multiple non-through cracks at low cement content (10%). However, as cement content increased, the proportion of central fracture in both types of specimens became similar.

Figure 10.

Percentage of different failure modes of stabilized clayey soil specimens: (a) 10% cement content, (b) 20% cement content, (c) 30% cement content.

The results demonstrate that the amount of cement determines the structure strength and failure mode of stabilized clayey soils, and the curing period enables the cement hydration process, which continuously enhances the structure. For the function of SAP, at low cement content (e.g., 10%), the soil–cement matrix is inherently weaker and more porous. After the SAP particles release their water and shrink, they leave behind well-defined, distributed macro-pores. These pores act as stress concentration points and pre-existing flaws, which facilitate the initiation of multiple micro-cracks under tensile loading. However, due to the overall low brittleness of the matrix, these cracks often do not have enough energy to coalesce into a single, through-going central fracture, resulting in the observed increase in “multiple non-through fractures”. At high cement content, the matrix becomes much stronger and more homogeneous. The influence of individual SAP-induced pores is diminished, and the material’s behavior is dominated by the brittle cementitious binder. This promotes a clean, single fracture propagating from the point of highest tensile stress at the center of the disk, which is the classic Brazilian test failure mode for brittle materials.

3.5. Correlation of Brazilian Tensile Strength vs. Unconfined Compressive Strength

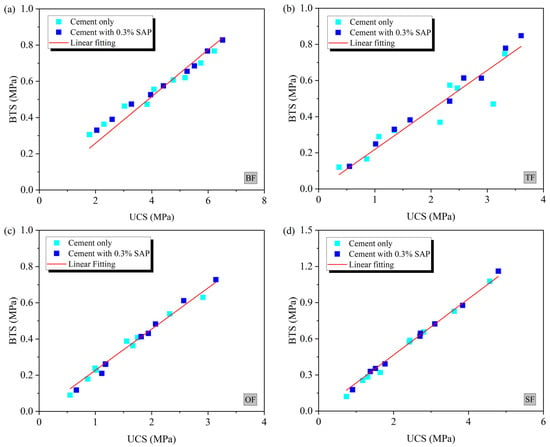

The accurate prediction of tensile strength, which is difficult to determine directly, using a simple and conventional unconfined compressive strength test holds significant practical implications for engineering practice. The significance of establishing a relationship between BTS and UCS lies in characterizing the intrinsic mechanical behavior of the composite material, which provides a fundamental basis for future model development. Numerous studies [55,56,57] have found that the compressive strength and tensile strength of cement–soil exhibit a linear relationship, which can be expressed by the following equation.

where σt is the tensile strength in MPa, σc is the unconfined compressive strength in MPa, and k is the proportionality coefficient.

This study investigated the correlation between the unconfined compressive strength and Brazilian tensile strength for four types of stabilized clayey soils under 18 different stabilizer admixture and curing period conditions. Figure 11a–d display a highly consistent linear proportional relationship between UCS and BTS for four different types of stabilized clayey soils. As listed in Table 5, all linear fittings yield coefficients of determination, R2, exceeding 0.98, with the proportionality coefficients ranging between 0.129 and 0.233.

Figure 11.

Relationship between BTS and UCS of stabilized clayey soils: (a) BF; (b) TF; (c) OF; (d) SF.

Table 5.

Correlation results for stabilized clayey soils.

For cement stabilized clayey soils, the macroscopic strength originates from the same microscopic structural framework, a composite formed by the bonding of cement hydration products with clay particles. Consequently, UCS and BTS exhibit a highly linear positive correlation. The classical Griffith’s criterion posits that the σt/σc ratio for ideal brittle materials is 1/8 (i.e., 0.125). However, the BTS/UCS ratios of stabilized clayey soils in this study are significantly higher than this theoretical value. This is primarily attributed to the presence of internal friction and variations in defect morphology. Stabilized clayey soil is not an ideal brittle material but rather a quasi-brittle material. Its failure mechanism is a complex outcome of the combined effects of brittle fracture and frictional slip. Additionally, the inability of SAP to significantly alter the BTS/UCS ratio indicates that it enhances the material’s absolute strength while preserving the inherent tensile-to-compressive strength relationship characteristic of a quasi-brittle geomaterial.

4. Conclusions

The absorption capacity of super-absorbent polymers for pore solutions in clayey soils was determined using the tea-bag method. A series of Brazilian tensile strength tests on stabilized clayey soils were conducted considering varying cement contents and curing periods. Based on the experimental results and subsequent analysis, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- The incorporation of cement is the primary factor governing the strength development of stabilized clayey soils. The BTS increases significantly and near-linearly with rising cement content and with an extending curing period, which is attributed to the progressive formation of cementitious hydrates that enhance the soil’s matrix integrity.

- The addition of SAP (Superabsorbent Polymer) acts as an effective performance optimizer, with its efficacy being highly dependent on both cement content and curing period. At lower cement contents, the effect of SAP is limited or slightly adverse, as its water absorption may introduce structural discontinuities within the weakly cemented matrix. At higher cement contents and with an extended curing period, SAP consistently enhances BTS. This underscores the role of SAP’s internal curing in facilitating long-term, uniform hydration and microstructural optimization.

- Failure mode evolution is a direct indicator of internal structural improvement. As the cement content increases, the curing period extends, and upon the SAP addition (when cement is sufficient), the failure mode shifts systematically from multiple non-through fracture to central fracture. The transformation is directly related to enhanced internal homogeneity and reduced internal defects within the stabilized clayey soils.

- A strong linear correlation exists between BTS and UCS for all investigated clayey soils. The proportionality coefficient, k, falls within a range of 0.129 to 0.233. This empirically validated relationship allows for reliable BTS estimation from UCS, and the specific ratio confirms the material’s quasi-brittle nature, governed by both cohesion and internal friction rather than pure brittle fracture.

This study has established the foundational macro-mechanical properties of SAP–cement stabilized clayey soils; future work should pursue a multi-scale investigation to unravel the underlying mechanisms. A comprehensive series of micro-scale experiments, utilizing techniques such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP), and X-ray diffraction (XRD), are proposed to quantitatively link key controlling factors, including clay fraction, initial water content, and evolving pore structure, to the observed macroscopic strength. This will be crucial for definitively elucidating the role of SAP at the particle level. Furthermore, evaluating the long-term stability of SAP itself and its sustained effectiveness under repeated environmental stresses is essential to validate the durable performance of this stabilization technique for permanent geotechnical structures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W. and J.R.; methodology, Z.W.; validation, Z.W. and J.W.; formal analysis, Z.W.; investigation, Z.W. and J.W.; resources, Z.W. and J.W.; data curation, Z.W. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W.; writing—review and editing, Z.W. and J.R.; visualization, Z.W.; supervision, J.R. and W.X.; project administration, J.R.; funding acquisition, J.R. and W.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors express their appreciation for the financial support from the China Scholarship Council (CSC) (Grant No. 201906410083) and experimental support from the GeoZentrum Nordbayern, Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Miura, N.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Nagaraj, T.S. Engineering Behavior of Cement Stabilized Clay at High Water Content. Soils Found. 2001, 41, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.J.; Santoso, A.M.; Tan, T.S.; Phoon, K.K. Strength of High Water-Content Marine Clay Stabilized by Low Amount of Cement. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2013, 139, 2170–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Kang, G.-C.; Chang, K.-T.; Ge, L. Chemically Stabilized Soft Clays for Road-Base Construction. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2015, 27, 04014199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horpibulsuk, S.; Miura, N.; Nagaraj, T.S. Clay–Water∕Cement Ratio Identity for Cement Admixed Soft Clays. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2005, 131, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, E.; Lau, C.C.; Anggraini, V.; Pasbakhsh, P. Stabilization of a soft marine clay using halloysite nanotubes: A multi-scale approach. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 173, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, S.H.; Kamruzzaman, A.H.M.; Lee, F.H. Physicochemical and Engineering Behavior of Cement Treated Clays. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2004, 130, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadir, P.; Ranjbar, N. Clayey soil stabilization using geopolymer and Portland cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 188, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, L.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, A.; Xiao, H. Use of recycled gypsum in the cement-based stabilization of very soft clays and its micro-mechanism. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2022, 14, 909–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, R.; Martirena, F.; Scrivener, K.L. The origin of the pozzolanic activity of calcined clay minerals: A comparison between kaolinite, illite and montmorillonite. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Farsakh, M.; Dhakal, S.; Chen, Q. Laboratory characterization of cementitiously treated/stabilized very weak subgrade soil under cyclic loading. Soils Found. 2015, 55, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, T.; Tang, Y.X. Estimation of compressive strength of cement-treated marine clays with different initial water contents. Soils Found. 2015, 55, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Wang, Z.-f.; Ding, G.-q.; Cao, Y.-P. Compressibility of cemented dredged clay at high water content with super-absorbent polymer. Eng. Geol. 2016, 208, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxman Kudva, P.; Nayak, G.; Shetty, K.K.; Sugandhini, H.K. A sustainable approach to designing high volume fly ash concretes. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 65, 1138–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, N.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Meehan Christopher, L.; Abd Majid Muhd, Z.; Tahir Mahmood, M.; Mohamad Edy, T. Improvement of Problematic Soils with Biopolymer—An Environmentally Friendly Soil Stabilizer. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2017, 29, 04016204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, N.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Meehan, C.L.; Majid, M.Z.A.; Rashid, A.S.A. Xanthan gum biopolymer: An eco-friendly additive for stabilization of tropical organic peat. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhelal, E.; Zahedi, G.; Shamsaei, E.; Bahadori, A. Global strategies and potentials to curb CO2 emissions in cement industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 51, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, R.M. Global CO2 emissions from cement production, 1928–2018. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1675–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabiri, K.; Omidian, H.; Zohuriaan-Mehr, M.J.; Doroudiani, S. Superabsorbent hydrogel composites and nanocomposites: A review. Polym. Compos. 2011, 32, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnopeeva, E.L.; Panova, G.G.; Yakimansky, A.V. Agricultural Applications of Superabsorbent Polymer Hydrogels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, X.; Chen, M.; Lu, L.; Cheng, X. Effects of super absorbent polymer on scouring resistance and water retention performance of soil for growing plants in ecological concrete. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 138, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Zhao, F.; Zeng, L.; Ren, Z.; Li, X. Role of superabsorbent polymer in compression behavior of high water content slurries. Acta Geotech. 2024, 19, 6163–6178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignon, A.; De Belie, N.; Dubruel, P.; Van Vlierberghe, S. Superabsorbent polymers: A review on the characteristics and applications of synthetic, polysaccharide-based, semi-synthetic and ‘smart’ derivatives. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 117, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Kim, M.; Oh, S.; Min, J.H.; Kang, D.; Han, C.; Ahn, T.; Koh, W.-G.; Lee, H. Multi-scale characterization of surface-crosslinked superabsorbent polymer hydrogel spheres. Polymer 2018, 145, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Wang, T.; Chen, Y.; Wang, M.; Jiang, G. Effect of internal curing with super absorbent polymers on the relative humidity of early-age concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 99, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Belie, N.; Gruyaert, E.; Al-Tabbaa, A.; Antonaci, P.; Baera, C.; Bajare, D.; Darquennes, A.; Davies, R.; Ferrara, L.; Jefferson, T.; et al. A Review of Self-Healing Concrete for Damage Management of Structures. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 5, 1800074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fořt, J.; Migas, P.; Černý, R. Effect of Absorptivity of Superabsorbent Polymers on Design of Cement Mortars. Materials 2020, 13, 5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.-S.; Choi, S.-Y.; Choi, Y.-S.; Yang, E.-I. Effect of Internal Pores Formed by a Superabsorbent Polymer on Durability and Drying Shrinkage of Concrete Specimens. Materials 2021, 14, 5199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, P.; Hu, Z.; Griffa, M.; Wyrzykowski, M.; Liu, J.; Lura, P. Mechanisms of internal curing water release from retentive and non-retentive superabsorbent polymers in cement paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 147, 106494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Zeng, L.; Li, X.; Shi, X.; Zhou, S.; Li, F. Fabric changes induced by super-absorbent polymer on cement–lime stabilized excavated clayey soil. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 13, 1124–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Peng, J.; Zhao, X.; Li, G.; Bai, L. Strength and Road Performance of Superabsorbent Polymer Combined with Cement for Reinforcement of Excavated Soil. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 9170431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Lan, X. Mechanical properties of loess subgrade treated by superabsorbent polymer. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e01741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; He, Y.; Han, C.; Shen, Y.; Tan, G. Stability Analysis of Soil Embankment Slope Reinforced with Polypropylene Fiber under Freeze-Thaw Cycles. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 5725708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortellazzo, G.; Russo, L.E.; Busana, S.; Carbone, L.; Favaretti, M.; Hangen, H. Field trial of a reinforced landfill cover system: Performance and failure. Geotext. Geomembr. 2022, 50, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hazarika, H.; Yuan, R. Stability analysis of seismic slopes with tensile strength cut-off. Comput. Geotech. 2019, 112, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Martin, C.D. Application of Flattened Brazilian Test to Investigate Rocks Under Confined Extension. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2018, 51, 3719–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wong, L.N.Y. The Brazilian Disc Test for Rock Mechanics Applications: Review and New Insights. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2013, 46, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diambra, A.; Festugato, L.; Ibraim, E.; Peccin da Silva, A.; Consoli, N.C. Modelling tensile/compressive strength ratio of artificially cemented clean sand. Soils Found. 2018, 58, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tao, J. Determination of Tensile Strength at Crack Initiation in Dynamic Brazilian Disc Test for Concrete-like Materials. Buildings 2022, 12, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D854-14; Standard Test Methods for Specific Gravity of Soil Solids by Water Pycnometer. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- ASTM D4318-17; Standard Test Methods for Liquid Limit, Plastic Limit, and Plasticity Index of Soils. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D7928-17; Standard Test Method for Particle-Size Distribution (Gradation) of Fine-Grained Soils Using the Sedimentation (Hydrometer) Analysis. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D3967-16; Standard Test Method for Splitting Tensile Strength of Intact Rock Core Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- Chilingar, G.V.; Knight, L. Relationship Between Pressure and Moisture Content of Kaolinite, Illite, and Montmorillonite Clays1. AAPG Bull. 1960, 44, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, S.; Tadza, M.Y.M.; Thomas, H.R. Soil-water characteristic curves of clays. Can. Geotech. J. 2014, 51, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröfl, C.; Snoeck, D.; Mechtcherine, V. A review of characterisation methods for superabsorbent polymer (SAP) samples to be used in cement-based construction materials: Report of the RILEM TC 260-RSC. Mater. Struct. 2017, 50, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoeck, D.; Schröfl, C.; Mechtcherine, V. Recommendation of RILEM TC 260-RSC: Testing sorption by superabsorbent polymers (SAP) prior to implementation in cement-based materials. Mater. Struct. 2018, 51, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, A.; Kiran, R. Quantifying the water donation potential of commercial and corn starch hydrogels in a cementitious matrix. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 4336–4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.Z.; Jia, X.M.; Kou, S.Q.; Zhang, Z.X.; Lindqvist, P.A. The flattened Brazilian disc specimen used for testing elastic modulus, tensile strength and fracture toughness of brittle rocks: Analytical and numerical results. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2004, 41, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wu, S.; Jin, A.; Gao, Y. Review of the Relationships between Crack Initiation Stress, Mode I Fracture Toughness and Tensile Strength of Geo-Materials. Int. J. Geomech. 2018, 18, 04018136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Moizant, R.; Ramírez-Berasategui, M.; Sánchez-Sanz, S.; Santos-Cuadros, S. Experimental verification of the boundary conditions in the success of the Brazilian test with loading arcs. An uncertainty approach using concrete disks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2020, 132, 104380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, F.-H.; Lee, Y.; Chew, S.-H.; Yong, K.-Y. Strength and Modulus of Marine Clay-Cement Mixes. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2005, 131, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis, A.; Deng, L.; Shao, L.; Li, H. Triaxial behaviour and image analysis of Edmonton clay treated with cement and fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 197, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganya, K.; Sivapullaiah, P.V. Compressibility of remoulded and cement-treated Kuttanad soil. Soils Found. 2020, 60, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavallali, A.; Vervoort, A. Effect of layer orientation on the failure of layered sandstone under Brazilian test conditions. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2010, 47, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, K.; Gurpersaud, N. Tensile Strength of Cement-Treated Champlain Sea Clay. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2022, 40, 5467–5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldovino, J.A.; Moreira, E.B.; Izzo, R.L.d.S.; Rose, J.L. Empirical Relationships with Unconfined Compressive Strength and Split Tensile Strength for the Long Term of a Lime-Treated Silty Soil. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 06018008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, N.C.; Bellaver Corte, M.; Festugato, L. Key parameter for tensile and compressive strength of fibre-reinforced soil–lime mixtures. Geosynth. Int. 2012, 19, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).