Abstract

The asphalt–aggregate interface is the weakest yet most critical component in asphalt mixtures, directly governing the pavement performance. In this study, the interfacial adhesion behavior between asphalt binder and aggregates with different chemical compositions (Al2O3, CaCO3, and SiO2) was investigated under varying conditions using molecular dynamics simulations. The effects of aggregate composition, environmental temperature, and asphalt aging were quantitatively assessed using key metrics, specifically interfacial adhesion energy and molecular concentration profiles near the interface. Results demonstrated that the chemical composition of aggregates fundamentally governed the asphalt–aggregate interfacial adhesion strength. Al2O3 exhibited the highest interfacial adhesion strength with asphalt binder, followed by CaCO3, with SiO2 showing the lowest strength. In terms of asphalt fractions, resins and aromatics were found to dominate the interfacial adhesion behavior due to their high molecular concentrations at the interface, with the contribution ranking as: resin > aromatic > saturate > asphaltene. The interfacial adhesion strength exhibited a non-monotonic temperature dependence. It increased with rising temperature and reached a peak value at 25–45 °C, and therefore declined because of excessive softening of asphalt binder. Furthermore, oxidative aging enhanced interfacial adhesion through strengthened electrostatic interactions. These molecular-level insights provide a fundamental understanding crucial for optimizing asphalt mixture design and enhancing pavement durability.

1. Introduction

Asphalt mixtures, a multiphase composite primarily composed of asphalt binder, mineral fillers, and aggregates, are widely used in pavement engineering due to their excellent road performance, efficient construction process, and recyclability [1,2]. However, repeated vehicle loading and environmental exposure can induce progressive deterioration in asphalt pavements, including cracking, rutting, and moisture damage [3,4]. Research has shown that the deterioration of interfacial adhesion is a critical mechanism, as the failure of asphalt mixtures commonly begins at the binder–aggregate interface before propagating to structural failure [5,6,7]. Therefore, investigating the adhesion properties at the asphalt–aggregate interfacial zone is crucial for addressing interfacial debonding failure and the resulting pavement distress.

Significant research efforts have been directed toward the characterization of the asphalt–aggregate interface using a variety of techniques, including macro-performance-based testing and micro/nanoscale analytical methods. At the macroscopic level, the evaluation primarily focuses on the direct assessment of mechanical behavior and durability under simulated service conditions. Shear tests and pull-off tests are routinely employed to quantify interfacial bond strength under varying temperature and moisture conditions [8,9]. The boiling test offers a classical method for qualitatively comparing the moisture resistance of asphalt binder coating on different aggregates [10,11]. The combined bubble pressure and bonding test provides parameters such as interfacial fracture energy [12]. Furthermore, environmental scanning electron microscopy enables in situ observation of the failure mechanisms at the interface. At the micro/nanoscale level, the fundamental mechanisms underlying these macroscopic behaviors are revealed by precise techniques. Surface free energy measurements offer a thermodynamic perspective for predicting work of adhesion and moisture susceptibility [13,14]. Atomic force microscopy allows for the direct quantification of nanoscale adhesive forces and surface topography [15,16,17,18,19]. Additionally, environmental scanning electron microscopy is applied for in situ failure observation. Advanced imaging technologies, including X-ray computed tomography and laser scanning, facilitate the precise three-dimensional reconstruction of aggregate morphology, providing a critical link between surface geometry and performance [20]. Despite these advancements, persistent challenges such as measurement reproducibility and the inherent chemical and topographical complexity of aggregate surfaces continue to hinder a complete elucidation of the intrinsic adhesion laws. Consequently, further investigation at the molecular scale is imperative to achieve a more profound and mechanistic understanding, which will ultimately guide the design of high-performance asphalt mixtures.

Molecular dynamics simulation has emerged as an indispensable computational methodology in interfacial research, attracting considerable scholarly attention in recent years [21,22,23]. Zhang et al. [24] evaluated the interfacial energy of SiO2 with different fractions of asphalt binder across a range of temperatures. The influence of oxidative aging on adhesive characteristics was investigated by Xu et al. [25,26] through three key parameters: work of adhesion, debonding work, and energy ratio. Shishehbor et al. [27] monitored the formation and breaking of chemical bonds at the asphalt–aggregate interface using the molecular dynamics simulation method. Gao et al. [28,29] systematically evaluated the adhesive performance between virgin/aged asphalt binders and mineral aggregates through molecular simulations. Sun et al. [30] analyzed the contribution of asphalt fractions to the total energy of the binder in dry and wet environments. Zhang et al. [31] evaluated the effectiveness of an eco-friendly anti-stripping agent in enhancing the cohesive and adhesive properties of asphalt mixtures. Ma et al. [32] revealed that asphalt polar molecules and mineral surface characteristics jointly governed interface adhesion behavior, and proposed key simulation parameters for optimizing surface treatment and energy calculation. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that molecular dynamics simulation serves as a robust and reliable tool for probing the interfacial behavior between asphalt binder and aggregates.

However, a systematic understanding of how the fundamental chemical nature of aggregates and asphalt fractions regulates the interfacial adhesion remains insufficiently explored. This study employed molecular dynamics simulations to analyze the interface adhesion behavior between asphalt binder and aggregates with distinct chemical properties. Molecular interaction models of asphalt binder and aggregates with different chemical compositions were constructed and subjected to molecular dynamics simulations under varied conditions, respectively, to elucidate interfacial adhesion strength and underlying molecular interactions. Quantitative analysis based on critical metrics was performed to assess the impacts of aggregate composition, environmental temperature, and asphalt aging, thereby revealing the intrinsic adhesion mechanisms.

2. Simulation Models and Methods

2.1. Molecular Models of Asphalt Binder

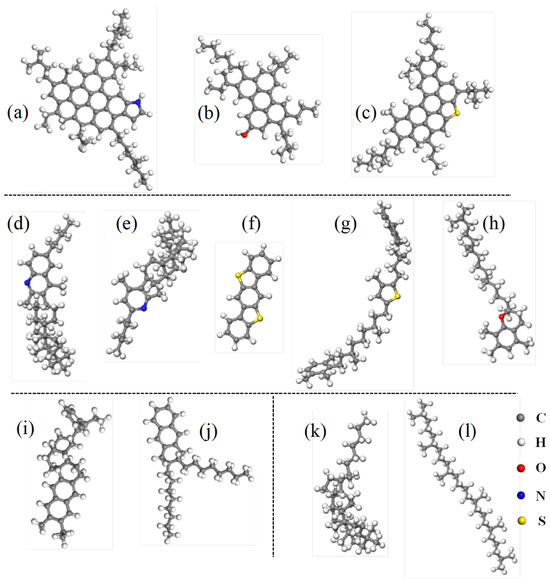

In this study, the asphalt binder was modeled using the classical four-component (saturates, aromatics, resins, and asphaltenes, SARA) twelve-molecule model established by Li and Greenfield [33], as depicted in Figure 1. The molecular model specifically represents the AAA-1 benchmark asphalt binder from the strategic highway research program in the United States, which is a paving-grade petroleum binder derived from a defined Wyoming crude oil source. By selecting the most representative molecular structures for each component, the molecular assembly was constructed according to experimentally determined mass ratios of the components [34]. This model system has been validated against key parameters such as density and cohesive energy density, and has been widely demonstrated to accurately replicate the physicochemical properties of real asphalt binder, thereby providing a reliable computational foundation for the molecular dynamics simulations conducted in this study.

Figure 1.

Representative molecular structures of asphalt binder: (a–c) asphaltene; (d–h) resin; (i,j) aromatic; (k,l) saturate.

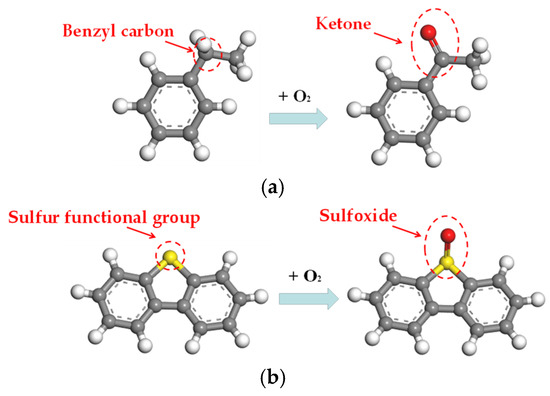

To model the oxidative aging process that is the predominant degradation mechanism in asphalt binders, oxygen atoms were incorporated at vulnerable functional groups, specifically targeting sulfur and carbon atoms. This approach successfully simulated the formation of ketones and sulfoxides as the primary oxidation products, as evidenced in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Oxidative aging process: (a) formation of ketone; (b) formation of sulfoxide.

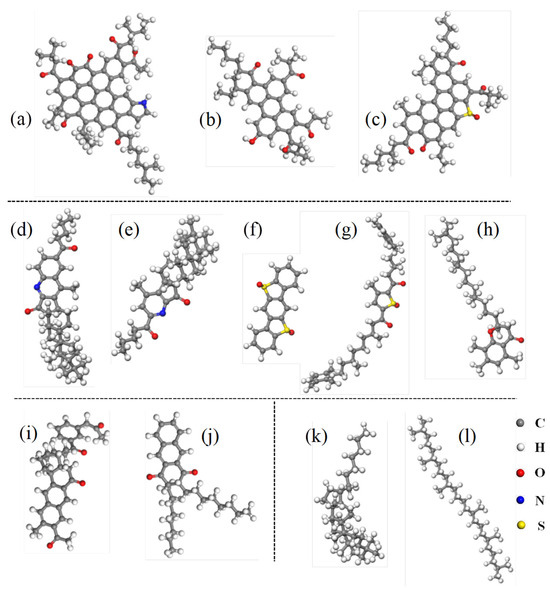

Based on the oxidation reactions shown in Figure 2, molecular models of aged asphalt binder components were constructed, as presented in Figure 3. Since saturates are nonpolar and chemically inert, lacking functional groups susceptible to oxidation, their molecular structure remains unchanged after aging [35].

Figure 3.

Representative molecular structures of aged asphalt binder: (a–c) aged asphaltene; (d–h) aged resin; (i,j) aged aromatic; (k,l) aged saturate.

Table 1 shows the detailed information on representative asphalt components under unaged and aged conditions. These molecular structures were then imported into the Materials Studio 7.0 software and assembled within an amorphous cell. The aged asphalt binder is classified as mild or short-term aging, based primarily on the minimal redistribution among SARA fractions. The mass proportion changes for all components remain below 1%, with asphaltenes increasing by 0.42%, aromatics by 0.51%, while resins and saturates decreased by 0.14% and 0.79%, respectively. This limited compositional stability is a hallmark of short-term aging, where the initial oxidation reactions have not yet progressed sufficiently to drive large-scale molecular recombination and significant changes in the constituent mass balance [35,36,37].

Table 1.

Details of representative molecules in unaged and aged asphalt binders.

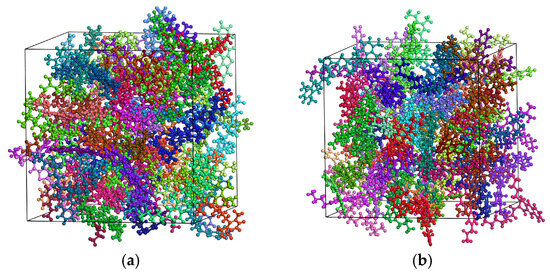

The asphalt binder molecular model was first subjected to a 5000-step energy minimization to reach its minimum-energy state. Dynamic simulations were then performed under the NVT (canonical) ensemble for 100 ps, followed by an additional 100 ps under the NPT (isothermal-isobaric) ensemble to achieve full thermodynamic equilibrium. The resulting equilibrated molecular models are depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Molecular models of (a) unaged and (b) aged asphalt binder at equilibrium (blue for resins, green for asphaltenes, red for saturates, purple for aromatics).

2.2. Molecular Models of Aggregates

Aggregates typically consist of rock-forming minerals such as silica, calcite, feldspar, and mica [30]. The diverse mineralogical composition of aggregates results in substantial variations in their physical and chemical properties. To capture this chemical diversity, aggregate models were constructed using three representative mineral compositions: SiO2 (common in quartzite, granite, and sandstone), Al2O3 (from feldspar minerals within basalt and granite, and CaCO3 (the main component of limestone and marble).

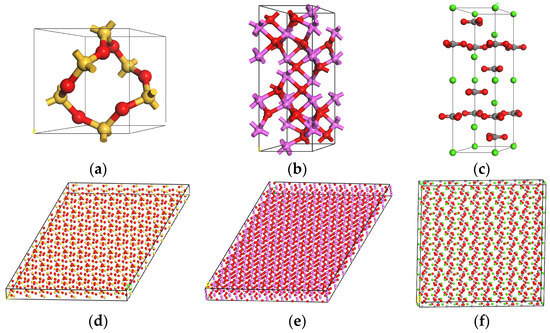

Crystal structure models of aggregates were sourced from the Materials Studio 7.0 software database. Cleaving was performed along the (0 0 1) plane of SiO2, the (0 0 −1) plane of Al2O3, and the (1 0 4) plane of CaCO3. Subsequently, the structure underwent energy minimization, and a supercell was constructed to expand the interfacial contact area. A vacuum layer of 0 Å was then applied to the surface to transform the system into a periodic three-dimensional model. The molecular models of aggregates are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Molecular models of aggregates: (a) crystal structure of SiO2; (b) crystal structure of Al2O3; (c) crystal structure of CaCO3; (d) supercell model of SiO2; (e) supercell model of Al2O3; (f) supercell model of CaCO3.

2.3. Molecular Models of Asphalt-Aggregate Interface

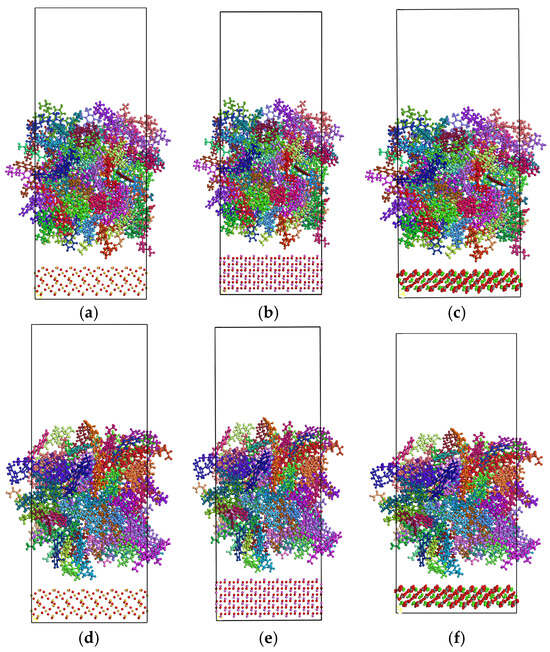

Molecular models of the asphalt–aggregate interface were constructed by superimposing energy-minimized asphalt molecules onto the mineral substrates, as shown in Figure 6 and Table 2. The atoms in mineral aggregates were constrained to enhance computational efficiency. This approximation is physically justified by their highly rigid crystalline lattices, wherein atomic vibration amplitudes are significantly smaller than their radii. Consequently, the mobility of these atoms is negligible at the simulated temperatures compared to asphalt binder.

Figure 6.

Molecular models of asphalt–aggregate interface: (a) SiO2 and unaged asphalt binder; (b) Al2O3 and unaged asphalt binder; (c) CaCO3 and unaged asphalt binder; (d) SiO2 and aged asphalt binder; (e) Al2O3 and aged asphalt binder; (f) CaCO3 and aged asphalt binder.

Table 2.

Detailed information on asphalt–aggregate interfacial model.

2.4. Simulation Details

All molecular dynamics simulations in this work were executed in the Materials Studio 7.0 software. The COMPASS II (Condensed-Phase Optimized Molecular Potentials for Atomistic Simulation Studies) forcefield was employed to describe molecular interactions. Atomic charges were assigned using the bond charge correction method embedded in the COMPASS II forcefield. This forcefield is well-suited for simulating the asphalt–aggregate interface due to its broad parameter coverage encompassing organic hydrocarbons (representing asphalt binder) and metal oxides (representing aggregate) [38]. Temperature and pressure were controlled using Nosé-Hoover thermostat and barostat, respectively. Van der Waals interactions were treated with a cutoff distance of 15.5 Å, while electrostatic interactions were handled by the Ewald summation method. A time step of 1 fs was employed to integrate the equations of motion. These settings align with well-established computational protocols for asphalt molecular simulations documented in prior literature [26,39].

2.5. Simulation of the Interfacial Molecular Interaction

The interfacial adhesion models were subjected to molecular dynamics simulations, consisting of 5000 steps of geometry optimization followed by a 100 ps simulation in the NVT ensemble. Simulations were performed at 5 °C, 25 °C, 45 °C, and 65 °C. The initial atomic velocities were randomly assigned according to the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution.

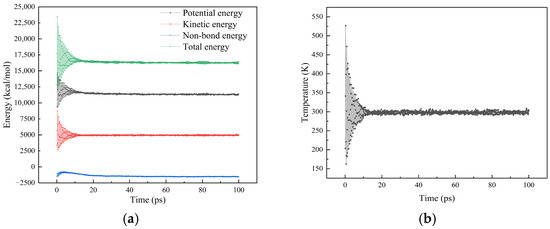

Temporal variations in energy and temperature of the interfacial adhesion model were recorded during the simulation. According to established criteria, thermodynamic equilibrium is achieved when fluctuation amplitudes remain below 10% [26]. Using the SiO2 asphalt binder interface model at 25 °C as an example, energy and temperature stabilized around the target values after 30 ps, exhibiting only minor oscillations thereafter. As depicted in Figure 7, the energy fluctuation amplitude was 4.26%, while that of temperature was merely 1.42%. These results confirm that a simulation duration of 100 ps was sufficient for the system to attain thermodynamic equilibrium.

Figure 7.

The fluctuation of energy and temperature during the dynamics simulation process: (a) energy; (b) temperature.

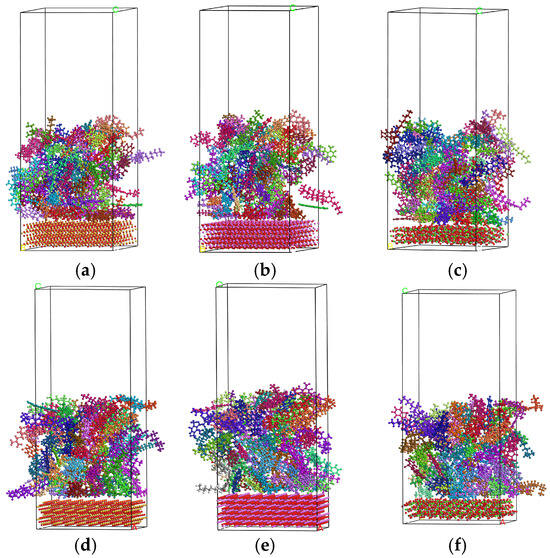

As illustrated in Figure 8, the interfacial model reached thermodynamic equilibrium at 25 °C. During the 100 ps dynamic simulation, asphalt binder molecules progressively approached the aggregate and ultimately adhered firmly to its surface. This behavior is indicative of a strong interfacial affinity between the asphalt binder and each of the tested aggregates (SiO2, Al2O3, and CaCO3).

Figure 8.

Thermodynamic equilibrium of asphalt–aggregate interfacial models: (a) SiO2 and unaged asphalt binder; (b) Al2O3 and unaged asphalt binder; (c) CaCO3 and unaged asphalt binder; (d) SiO2 and aged asphalt binder; (e) Al2O3 and aged asphalt binder; (f) CaCO3 and aged asphalt binder.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Validation of the Asphalt Binder Molecular Model

It is essential to establish the rationality and applicability of the asphalt molecular model to ensure accurate simulation results. The thermodynamic parameters, including density and solubility, were employed to validate the molecular model. Density simulations were conducted using the Forcite module under the NPT ensemble for 100 ps at various temperatures. Solubility parameters were derived from the cohesive energy density calculations performed in the Forcite module to assess the stability of the asphalt molecular model.

The simulated values of density and solubility are summarized in Table 3. The calculated density shows good agreement with values reported in previous studies. As expected, the density of the aged asphalt binder is slightly higher than that of the neat asphalt binder. The simulated solubility parameters are also consistent with the range of 15.3–23.0 (J/cm3)0·5 reported in the literature [39,40]. Although the solubility parameter of the aged asphalt binder increases to some extent, it remains within an acceptable range.

Table 3.

Thermodynamic parameters of the asphalt binder molecular model.

In summary, the simulated density and solubility parameters for both neat and aged asphalt binders fall within reasonable ranges. Therefore, the developed molecular model is capable of reflecting the macroscopic properties of conventional asphalt and can provide reliable results in subsequent simulations.

3.2. Analysis of the Interfacial Molecular Interaction

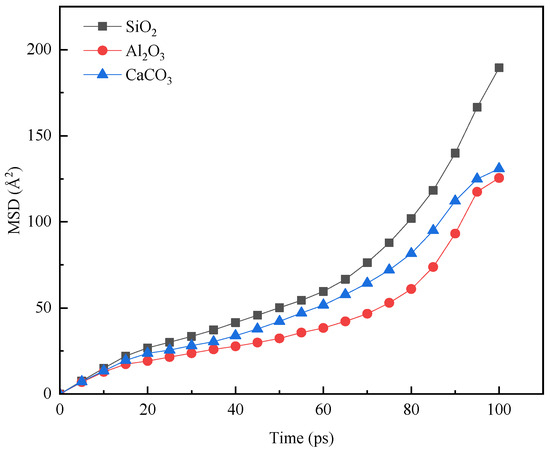

The interfacial molecular interaction can be characterized by the diffusion behavior of four asphalt constituents on mineral substrates. The molecular mobility is tracked over time, and the diffusion coefficient, a key metric of atomic motion, is derived from the mean square displacement (MSD). The MSD, defined as the squared deviation of a particle’s position from a reference position over time, is calculated using Formula (1). The diffusion coefficient (D) is subsequently obtained from the slope of the MSD versus time plot, as defined in Formula (2).

where MSD is the mean square displacement; ri (0) is the initial position of molecule i; ri(t) is the position of molecule i at time t; D is the diffusion coefficient.

As shown in Figure 9, the diffusion capacity of asphalt molecules varied significantly across the three aggregate surfaces. The strongest molecular mobility was observed on the silicon dioxide surface. Calcium carbonate ranked second in diffusion capacity, while the aluminum oxide surface significantly suppressed asphalt molecular diffusion. These variations primarily originate from differences in the strength of interfacial interactions between asphalt molecules and the aggregates. The strongest adsorption, which significantly restricted molecular movement, occurred on the Al2O3 surface. Interactions with the calcium carbonate surface were moderately strong, whereas the weakest interactions occurred with the silicon dioxide surface, resulting in greater molecular mobility.

Figure 9.

MSD of asphalt molecules on the surface of aggregates with different compositions.

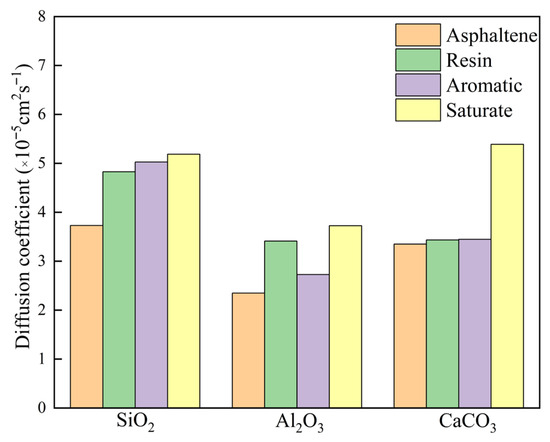

As illustrated in Figure 10, significant differences were observed in the diffusion coefficients of asphalt binder fractions across three mineral surfaces. Overall, the highest diffusion coefficient was detected on SiO2, followed by CaCO3, while Al2O3 exhibited the lowest value. This trend aligns with the aforementioned MSD data. Among the four fractions, saturate demonstrated the largest diffusion coefficient, with aromatic and resin showing comparable values, whereas asphaltenes consistently displayed the lowest diffusion capacity. This hierarchical pattern is attributed to molecular weight variations: components with lower molecular weight typically possess enhanced molecular mobility, thereby facilitating higher diffusion coefficients.

Figure 10.

Diffusion coefficients of the SARA fractions on different aggregate compositions.

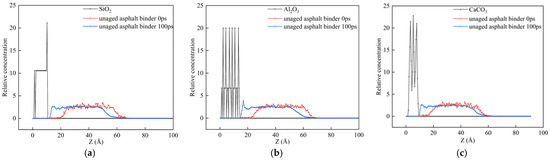

Analysis of asphalt molecular diffusion at the asphalt–aggregate interface requires combined characterization of directional motion. While the diffusion coefficient derived from MSD reflects overall molecular activity [41], it cannot resolve directional behavior. To investigate the orientation of asphalt fractions at mineral surfaces, their relative concentration profiles along the surface normal direction (Z-axis) were calculated. These profiles, which quantify atomic density along the coordinate axes, enable the quantitative characterization of spatial heterogeneity in component enrichment near the interface. Here, relative concentration is defined as the ratio of atomic count on a specific plane to the total atoms in the system, with its three-dimensional profile revealing orientation-dependent dispersion patterns of asphalt binder components at the aggregate interface. Figure 11 presents the concentration distribution of unaged asphalt binder at 25 °C. In the initial configuration of the interfacial adhesion model of SiO2, Al2O3, CaCO3, and asphalt binder, there are three main regions: the left region filled with aggregate, the middle region filled with asphalt molecules, and the right vacuum region. After the 100 ps dynamics simulation, the asphalt molecules moved left along the z axis, reaching the maximum relative concentration on the interface. On the Al2O3 surface, significantly higher molecular concentrations were observed compared to SiO2 and CaCO3, indicating a stronger work of adhesion between Al2O3 and asphalt binder than that of the other two aggregate compositions.

Figure 11.

Relative concentration distribution of asphalt molecules along the z-axis in the interfacial model between asphalt binder and aggregate with different compositions: (a) SiO2; (b) Al2O3; (c) CaCO3.

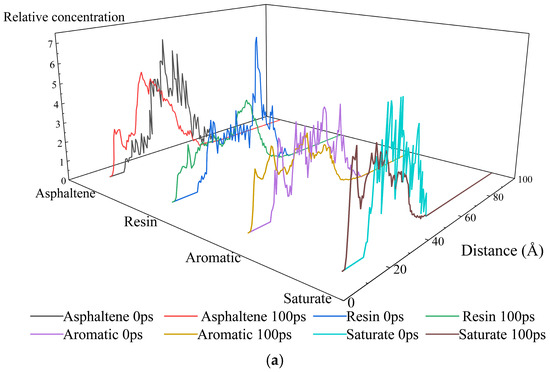

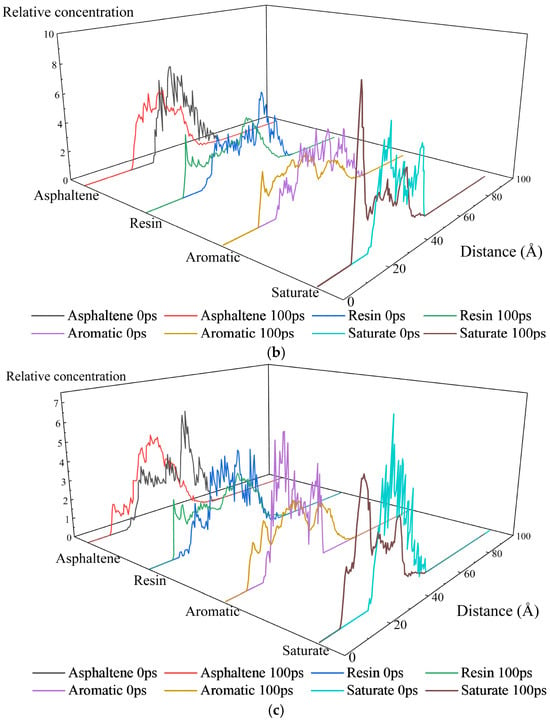

As shown in Figure 12, distinct concentration profiles of asphalt binder fractions at aggregate interfaces were observed across three systems. Significant differences existed between 0 ps and 100 ps, reflecting synergistic effects of molecular thermal motion and inter-component interactions. Molecular thermal motion provides energy for component diffusion and aggregate dissociation reorganization, driving the evolution from initial static distribution toward dynamic equilibrium during simulation. This manifests as displacement, splitting, or fusion of concentration peaks. Inter-component interactions govern spatial rearrangements: asphaltenes aggregate via π-π stacking and hydrogen bonding due to polycyclic aromatic structure; resin adsorbs onto asphaltene aggregates, exerting dispersive effects; aromatics dissolve polar components as solvents; saturates exhibit poor compatibility with others owing to weak polarity. This dynamic “aggregation–dispersion–dissolution–separation” network continuously adjusts component spatial distribution throughout the simulation. Before simulation, the concentration profiles of four fractions spanned 20–70 Å. After kinetic evolution, distributions shifted to 10–70 Å, demonstrating overall migration toward aggregate layers—consistent with the MSD results. Notably, saturates exhibited significantly higher peak concentrations than other components on all three aggregate compositions. This phenomenon arises from their higher diffusion coefficients coupled with a lower mass fraction in the asphalt binder, where fewer atoms generate sharp concentration peaks.

Figure 12.

Relative concentration distribution of asphalt fractions along the z-axis in the interfacial models between asphalt binder and aggregates with different compositions: (a) SiO2; (b) Al2O3; (c) CaCO3.

The adsorption at the SiO2 interface is primarily governed by hydrogen bonding, exhibiting slower component migration and lower adsorption strength than the surface polarity-driven interactions with CaCO3. Polar groups in asphaltenes form hydrogen bonds and dipole interactions with SiO2, constraining asphaltene aggregates near the interface. After 100 ps simulation, the sharp initial peak underwent broadening into flattened oscillations, indicating weakened interfacial confinement. Resin weakly adsorbed via van der Waals and dipole interactions, showing disrupted dispersive capacity. This led to localized asphaltene aggregate recoalescence, while resin concentration profiles developed a gradient from the “interface adsorption zone” to the “bulk dispersion zone”. In contrast, aromatics, functioning as a solvent and experiencing minimal interfacial disruption, maintained a stable dissolution-diffusion equilibrium, with their concentration curves remaining similar to the initial (0 ps) state.

The Al2O3 surface possesses Al-O polar bonds and weak acidic/basic sites, exhibiting a “balanced adsorption” characteristic towards both polar and non-polar components. Polar functional groups in asphaltenes interact with the Al-O dipoles, while resins undergo weak interactions with the acidic/basic sites at the interface. This leads to a more uniform distribution of both components between the interface and the bulk phase. After 100 ps of simulation, the asphaltene aggregates exhibit a moderate degree of dissociation, while the dispersing function of the resins is less affected by interfacial interference. The asphaltenes peak positions show minimal shift between 0 ps and 100 ps, with symmetric concentration profile peaks. Meanwhile, the concentration fluctuations of aromatic fractions become more uniform, attributed to the moderate adsorption of polar components at the interface.

The CaCO3 surface features primarily ionic bonding and, though exhibiting some polarity, possesses a surface polarity weaker than that of Al2O3. Consequently, the evolution of asphaltene aggregates is less affected by interfacial adsorption and relies primarily on their own thermal motion and the dispersing action of resin. Following the simulation, dissociation-recombination of asphaltene aggregates occurs predominantly within the bulk phase, while resins continually and efficiently disperse the asphaltenes. The peak positions of their concentration profiles migrate due to thermal motion, with peak heights decreasing as a result of the dispersing action. Concurrently, due to the dynamic changes in the asphaltene aggregates, dissolved components are released near the interface, causing the aromatic fraction concentration peak to decrease and become more uniformly distributed.

3.3. Quantification of Interfacial Adhesion Strength

3.3.1. Calculation Method of Work of Adhesion

The interfacial adhesion strength between asphalt binder and aggregate is quantified using the work of adhesion, defined as the minimum work required to separate the bonded interface per unit area [42]. This parameter is determined using the following procedure. First, the asphalt–aggregate composite system was equilibrated through molecular dynamics simulation to achieve a stable configuration, from which the total potential energy of the composite system (Etotal) was extracted. Using a decomposition approach, the pure asphalt binder system energy (Ebinder) was calculated by digitally removing the aggregate atoms from the equilibrated composite system. Conversely, the pure aggregate system energy (Eaggregate) was obtained by removing the asphalt binder atoms. Both calculations preserved the original simulation cell dimensions to maintain consistency. The interfacial interaction energy (ΔE), calculated as shown in Formula (3), is inherently negative since it represents the energy released upon interface formation. The work of adhesion (Wadhesion) is subsequently obtained as the absolute value of the interfacial interaction energy per unit area, following the fundamental relationship expressed in Formula (4).

where Wadhesion represents the work of adhesion (mJ/m2); ΔE represents the interfacial interaction energy (kcal/mol); Etotal represents the total potential energy of the entire asphalt–aggregate composite system after equilibration (kcal/mol); Ebinder represents the total potential energy of the pure asphalt binder system, obtained by removing the aggregate portion while maintaining the simulation box of identical dimensions (kcal/mol); Eaggregate represents the total potential energy of the pure aggregate system, obtained by removing the asphalt portion while maintaining the simulation box of identical dimensions (kcal/mol); A represents the interfacial contact area between asphalt binder and aggregate (Å2); and K represents the unit conversion coefficient, K = 695.

Work of adhesion serves as a key indicator of interfacial stability. A higher value corresponds to a more stable interface, as it signifies that greater energy input is required for separation. This strong interfacial bonding enhances the composite’s resistance to moisture damage and mechanical stress, thereby improving overall pavement durability. Conversely, a lower work of adhesion indicates inferior interfacial compatibility and weaker bonding. Such compromised interfaces are more susceptible to failure under environmental and mechanical loads, ultimately leading to pavement distress such as raveling and potholing.

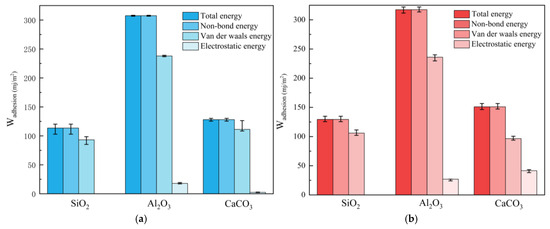

3.3.2. Effect of Aggregate Composition and Asphalt Aging

Energy analysis of the asphalt–aggregate interface model at 25 °C reveals that the interaction potential energies between asphalt binder and aggregate are negative, indicating attractive interactions. As displayed in Figure 13, the work of adhesion calculated using Formula (4) follows the order: Al2O3 > CaCO3 > SiO2, demonstrating its strong dependence on the chemical composition of the aggregate. The high adhesion work for Al2O3 is attributed to the polar Al–O bonds, which enable strong dipole interactions with resin and aromatic phenol molecules [43]. Although CaCO3 also contains polar bonds, it forms fewer effective interactions with asphalt molecules than Al2O3. Conversely, the nature of Si–O bonds in SiO2 results in the weakest interactions. In these interface models, the non-bonded energy equals the total energy of the system, demonstrating that the work of adhesion primarily originates from non-bonded interactions dominated by electrostatic and van der Waals forces. Van der Waals forces play a dominant role in the adhesion at the asphalt–aggregate interface, whereas the contribution of electrostatic energy is minor. Electrostatic interactions play a more pronounced role in the adhesion energy at the CaCO3 and Al2O3 interfaces compared to the SiO2 interface. This is attributed to the easy protonation of the Al3+ surface, which strongly attracts negatively charged polar groups in asphalt binder, and the positively charged Ca2+ ions, which form strong ionic bonds with carboxylates in asphalt binder, resulting in more pronounced charge characteristics.

Figure 13.

Work of adhesion at: (a) unaged asphalt–aggregate interface; (b) aged asphalt–aggregate interface.

The work of adhesion between the aged asphalt binder and mineral aggregate after simulation exceeds that between the unaged asphalt binder and mineral aggregate. The enhanced interfacial adhesion arises from the strengthened electrostatic interactions between the polar oxygen-containing functional groups generated during oxidative aging and the charged surface sites of the mineral substrate. This simulation result reasonably explains how short-term or mild asphalt aging improves asphalt–aggregate interfacial adhesion performance. It is crucial to note that the findings of this study are specific to the particular aging conditions under investigation and may not be universally applicable to all aged asphalt binders. Specifically, long-term aging has the potential to trigger excessive hardening in asphalt binder, which can significantly undermine its adhesion performance [36]. Consequently, it is imperative to conduct a systematic exploration of the impacts of various aging conditions on adhesion performance.

Analysis of the asphalt fractions, as presented in Table 4, indicates that resins and aromatics play a critical role in aggregate adhesion, accounting for the majority of the adhesion capacity, while the contributions from asphaltenes and saturates are relatively minor. This implies that the adhesion between asphalt binder and aggregate is primarily governed by resins and aromatics. Due to their relatively high concentration in asphalt binder, resins and aromatics are able to form strong adsorption with the aggregate. In contrast, despite their strong polarity, asphaltenes exhibit relatively weak adhesion to the aggregate due to their low concentration in the asphalt binder. Saturates, which are essentially non-polar and predominantly consist of low-molecular-weight compounds, consequently possess limited adhesive characteristics.

Table 4.

Work of adhesion between asphalt fractions and different aggregate compositions.

3.3.3. Effect of Environmental Temperature

Temperature exerts a significant influence on the work of adhesion at the asphalt–aggregate interface, as presented in Table 5. As the temperature increases, the input of thermal energy enhances the molecular mobility at the interface. This promotes more thorough contact and interdiffusion, thereby increasing the work of adhesion. A peak work of adhesion is observed within the temperature range of 25–45 °C, where chemical adsorption proceeds effectively, and the asphalt binder in an ideal viscoelastic balance possesses sufficient fluidity to wet the aggregate while retaining adequate cohesion to sustain strong interfacial bonds. However, beyond this temperature range, asphalt binder forms relatively thicker films on the aggregate surface and may even undergo excessive flow. This weakens van der Waals forces and chemical bonding at the asphalt–aggregate interface, leading to a decrease in adhesion strength.

Table 5.

Work of adhesion at the asphalt–aggregate interface under varying temperatures.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the interfacial adhesion behavior between asphalt binder and mineral aggregates using molecular dynamics simulations. The key findings are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- The chemical composition of aggregates fundamentally governed the asphalt–aggregate interfacial adhesion strength. Al2O3 exhibited the highest interfacial adhesion strength with asphalt binder, followed by CaCO3, with SiO2 showing the lowest strength.

- (2)

- In terms of asphalt fractions, resin and aromatics were the primary contributors to interfacial adhesion strength due to their notably high concentration and functional groups capable of interacting with aggregate surfaces. Although asphaltenes possessed strong polarity, their contribution remained limited owing to their low concentration and strong aggregation tendency.

- (3)

- The interfacial adhesion strength was enhanced by oxidative aging due to the strengthened electrostatic interactions between the polar oxygen-containing functional groups generated during oxidative aging and the charged surface sites of the mineral substrate.

- (4)

- The interfacial adhesion strength exhibited significant temperature dependence. It increased with rising temperature and reached a peak value at 25–45 °C due to improved molecular mobility and enhanced spreading of the asphalt binder. The interfacial adhesion strength declined thereafter because of excessive softening of the asphalt binder.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; methodology, S.L.; software, S.L. and X.S.; validation, X.W.; formal analysis, Y.W. and X.S.; investigation, Y.L. and S.L.; resources, Y.L. and Y.W.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. and S.L.; writing—review and editing, S.L.; visualization, S.L.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, Y.L.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by “Key Scientific Research Project of Colleges and Universities in Henan Province (grant number 24A580003)”, “Key Technologies Research and Development Program of Henan Province (grant number 242102241011)”, and “Student Practical Curriculum Project of Nanyang Normal University (grant number SPCP2025565)”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SARA | Saturates, aromatics, resins, and asphaltenes |

| NVT | Canonical ensemble |

| NPT | Isothermal-isobaric ensemble |

| MSD | Mean square displacement |

References

- Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ago, C.; Oeser, M. Investigation on mechanical performance of porous asphalt mixtures treated with laboratory aging and moisture actions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 238, 117694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, Q.; Yang, S.; Oeser, M.; Ago, C. Study of migration and aiffusion during the mixing process of asphalt mixtures with RAP. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2021, 22, 1578–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yao, Z.; Wang, K.; Wang, F.; Jiang, H.; Liang, M.; Wei, J.; Airey, G. Sustainable utilization of bauxite residue (red mud) as a road material in pavements: A critical review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 270, 121419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Liu, X.; Erkens, S. Insight into the critical evaluation indicators for fatigue performance recovery of rejuvenated bitumen under different rejuvenation conditions. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 175, 107753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Oeser, M.; Mohd Hasan, M.R. Investigation on the morphological and mineralogical properties of coarse aggregates under VSI crushing operation. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2021, 22, 1611–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, X.; Luo, R.; Lytton, R.L. Crack initiation in asphalt mixtures under external compressive loads. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 72, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, X.; Ren, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Role of surface roughness in surface energy calculation of aggregate minerals. Transp. Res. Rec. 2024, 2678, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Redelius, P.; Kringos, N. Evaluation of adhesive properties of mineral-bitumen interfaces in cold asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 125, 1005–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canestrari, F.; Cardone, F.; Graziani, A.; Santagata, F.A.; Bahia, H.U. Adhesive and cohesive properties of asphalt-aggregate systems subjected to moisture damage. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2010, 11, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xie, J.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, S. Characteristics of bonding behavior between basic oxygen furnace slag and asphalt binder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 64, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, J.; Guo, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Z.; Ren, J. Evaluation of the adhesion between aggregate and asphalt binder based on image processing techniques considering aggregate characteristics. Materials 2023, 16, 5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fini, E.H.; Al-Qadi, I.L. Development of a pressurized blister test for interface characterization of aggregate highly polymerized bituminous materials. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2011, 23, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Guo, M. Using surface free energy method to study the cohesion and adhesion of asphalt mastic. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Guo, M. Interfacial thickness and interaction between asphalt and mineral fillers. Mater. Struct. 2014, 47, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Burnham, N.A.; Mallick, R.B.; Tao, M. A systematic AFM-based method to measure adhesion differences between micron-sized domains in asphalt binders. Fuel 2013, 113, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Tan, Y.; Yu, J.; Hou, Y.; Wang, L. A Direct characterization of interfacial interaction between asphalt binder and mineral fillers by atomic force microscopy. Mater. Struct. 2017, 50, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyne, Å.L.; Wallqvist, V.; Birgisson, B. Adhesive surface characteristics of bitumen binders investigated by atomic force microscopy. Fuel 2013, 113, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Cui, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Li, X. Effect of material composition on nano-adhesive characteristics of styrene-butadiene-styrene copolymer-modified bitumen using atomic force microscope technology. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2019, 89, 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, P.; Gong, X. Nanostructure characterization of asphalt-aggregate Interface through molecular dynamics simulation and atomic force microscopy. Fuel 2017, 189, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, G.; Kang, H.; Zhang, J.; Rui, L.; Lyu, L.; Pei, J. Asphalt-aggregates interface interaction: Correlating oxide composition and morphology with adhesion. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 457, 139317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Poot, M.; Liu, X.; Erkens, S. Developing a multi-scale framework to predict and evaluate cohesion and adhesion of rejuvenated bitumen: Insights from molecular dynamics simulations and experiments. Mater. Des. 2025, 252, 113791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Liu, X.; Erkens, S.; Lin, P.; Gao, Y. Multi-component analysis, molecular model construction, and thermodynamics performance prediction on various rejuvenators of aged bitumen. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 360, 119463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Fu, Z.; Raos, G.; Ma, F.; Zhao, P.; Hou, Y. Molecular dynamics simulation of adhesion at the asphalt-aggregate interface: A review. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 44, 103706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Greenfield, M.L. Analyzing properties of model asphalts using molecular simulation. Energy Fuels 2007, 21, 1712–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Wang, H. Study of cohesion and adhesion properties of asphalt concrete with molecular dynamics simulation. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2016, 112, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Wang, H. Molecular dynamics study of oxidative aging effect on asphalt binder properties. Fuel 2017, 188, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishehbor, M.; Pouranian, M.R.; Imaninasab, R. Evaluating the adhesion properties of crude oil fractions on mineral aggregates at different temperatures through reactive molecular dynamics. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2018, 36, 2084–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gu, F. Molecular dynamics investigation of interfacial adhesion between oxidised bitumen and mineral surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 479, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, F.; Xu, T.; Wang, H. Impact of minerals and water on bitumen-mineral adhesion and debonding behaviours using molecular dynamics simulations. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 171, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Wang, H. Moisture effect on nanostructure and adhesion energy of asphalt on aggregate surface: A molecular dynamics study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 510, 145435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, M.; Hong, J.; Lai, F.; Gao, Y. Molecular dynamics study on improvement effect of bis(2-Hydroxyethyl) terephthalate on adhesive properties of asphalt-aggregate interface. Fuel 2021, 285, 119175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wu, J.; Liu, Q.; Ren, W.; Oeser, M. Molecular dynamics simulation of the bitumen-aggregate system and the effect of simulation details. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 285, 122886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.D.; Greenfield, M.L. Chemical compositions of improved model asphalt systems for molecular simulations. Fuel 2014, 115, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Sun, G.; Zhu, X.; Ye, F.; Xu, J. Intrinsic temperature sensitive self-healing character of asphalt binders based on molecular dynamics simulations. Fuel 2018, 211, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cao, J.; Chai, J.; Cao, C.; Si, Z.; Li, Y. Adhesion between asphalt molecules and acid aggregates under extreme temperature: A reaxff reactive molecular dynamics study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 285, 122882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Yin, L.; Li, M.; You, Z.; Jin, D.; Xin, K. A state-of-the-art review of asphalt aging behavior at macro, micro, and molecular scales. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 460, 139738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Gu, X.; Wang, H.; Hu, D. Numerical and experimental evaluation of adhesion properties of asphalt-aggregate interfaces using molecular dynamics simulation and atomic force microscopy. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2022, 23, 1564–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Jin, Z.; Yang, C.; Akkermans, R.L.C.; Robertson, S.H.; Spenley, N.A.; Miller, S.; Todd, S.M. COMPASS II: Extended coverage for polymer and drug-like molecule databases. J. Mol. Model. 2016, 22, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Multi-gradient analysis of temperature self-healing of asphalt nano-cracks based on molecular simulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 250, 118859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Z.; Sun, B. Influencing Factors and Evaluation of the Self-Healing Behavior of Asphalt Binder Using Molecular Dynamics Simulation Method. Molecules 2023, 28, 2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Tarefder, R.A. Investigation of asphalt aging behaviour due to oxidation using molecular dynamics simulation. Mol. Simul. 2016, 42, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; He, L.; Chen, D. Sorption and distribution of asphaltene, resin, aromatic and saturate fractions of heavy crude oil on quartz surface: Molecular dynamic simulation. Chemosphere 2013, 92, 1465–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nian, T.; Li, P.; Huang, X. Evaluation of highland barley straw fiber reinforced asphalt-aggregate interface. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 53, 150–157, 165. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).