Effect of Horizontal Stiffeners on the Efficiency of Steel Beams in Resisting Bending and Torsional Moments: Finite Element Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Finite Element Model Study

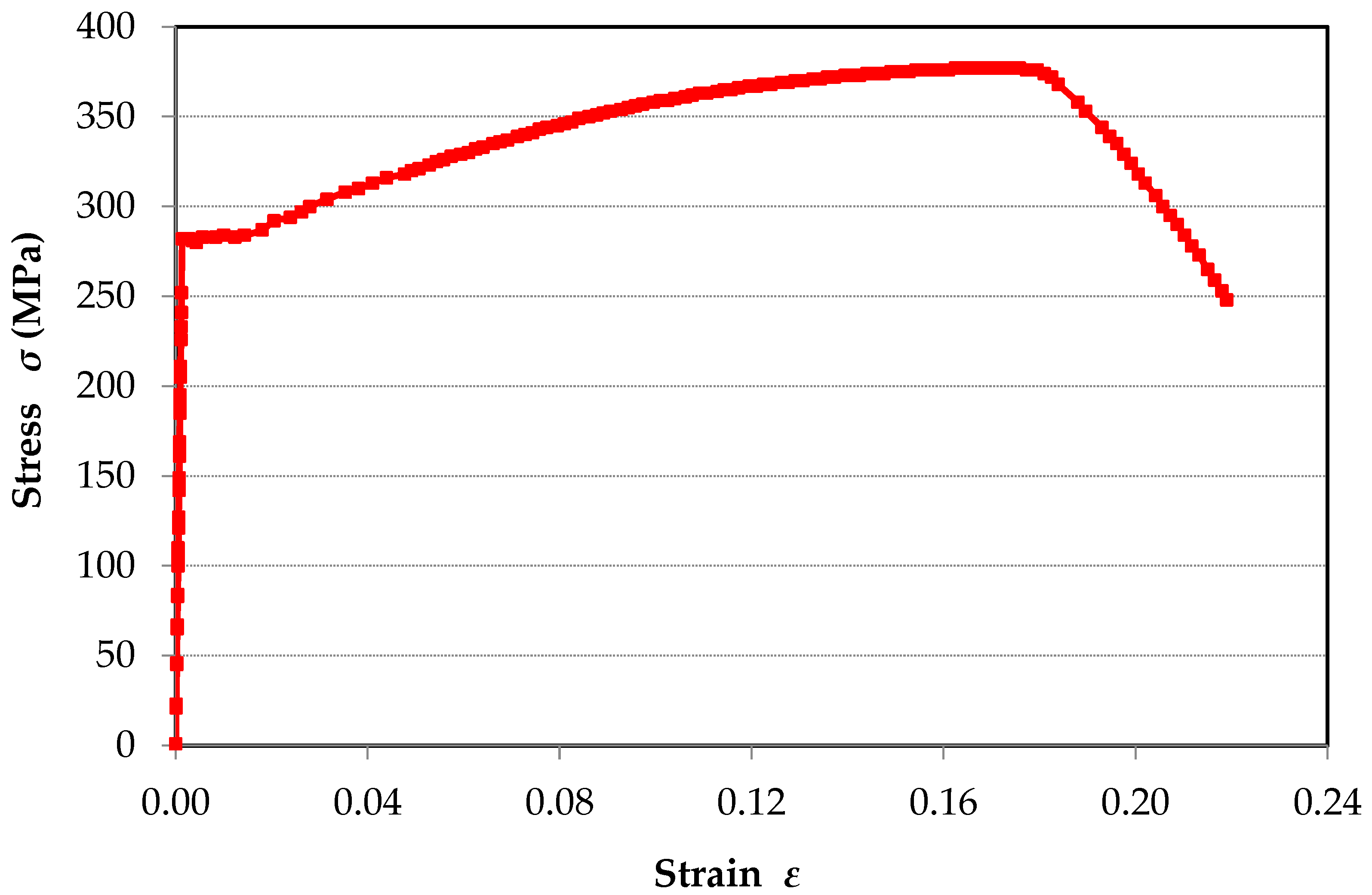

2.1. Modeling and Characteristics of Steel Materials

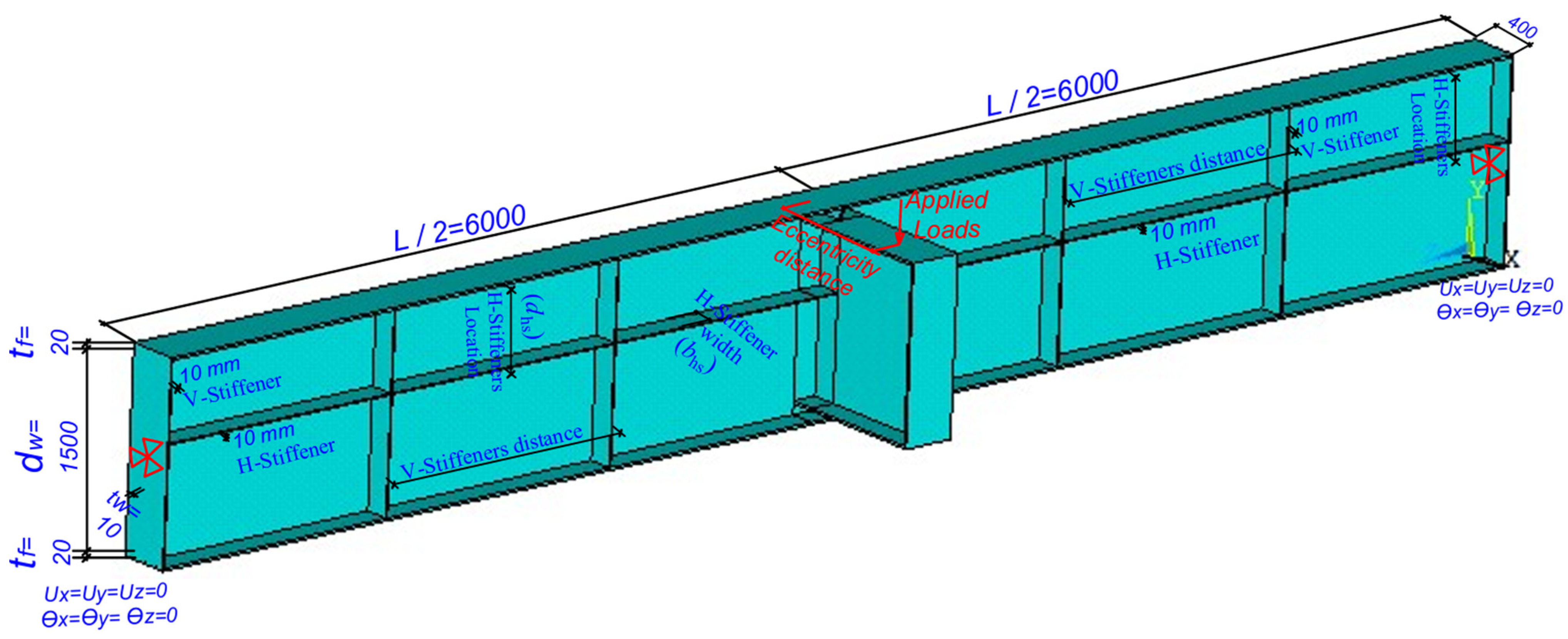

2.2. Structural Model Studies

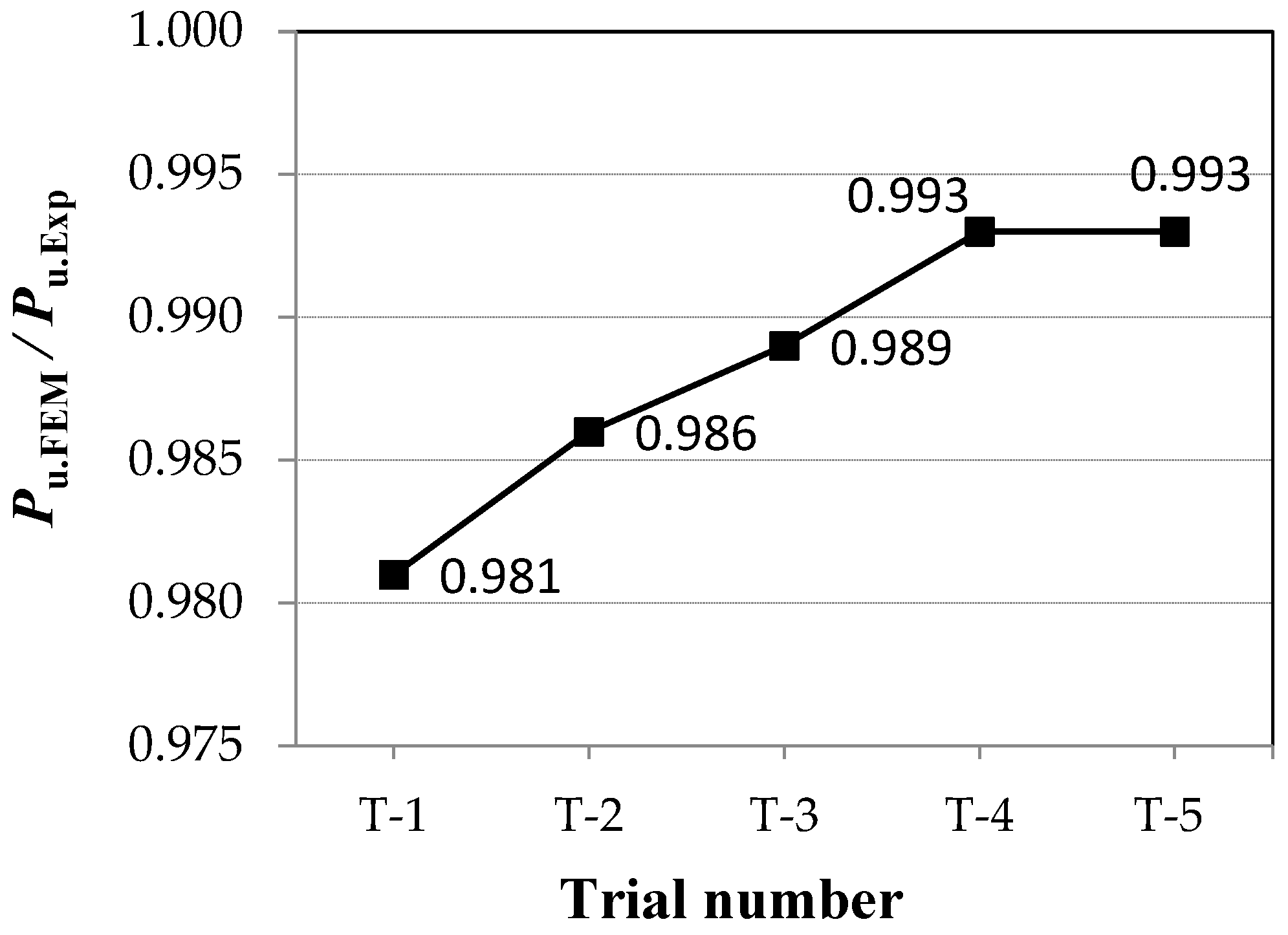

2.3. Choosing the Optimal Mesh Size for Element Convergence

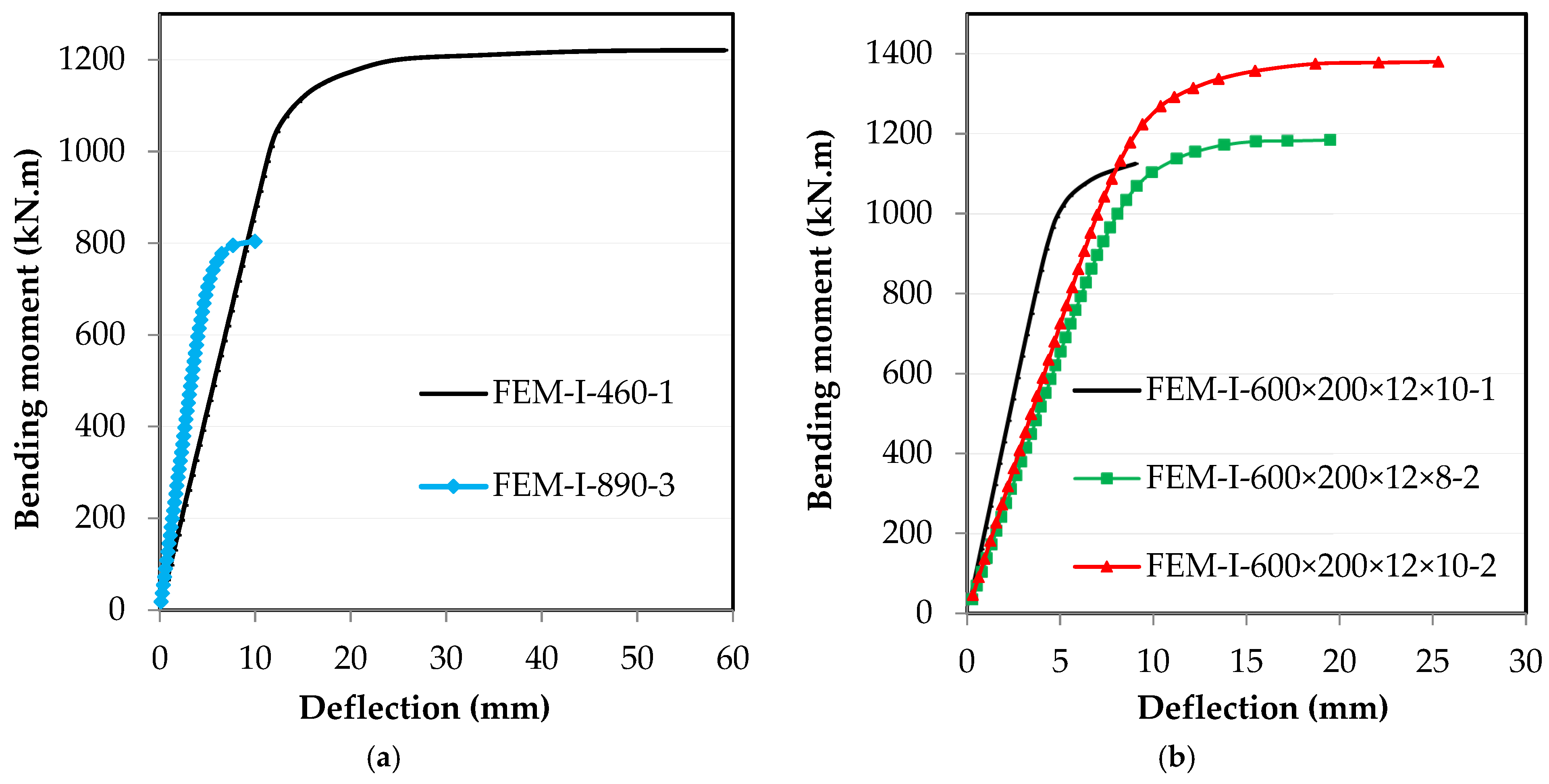

3. Verify Results from FEM

4. Results and Discussion

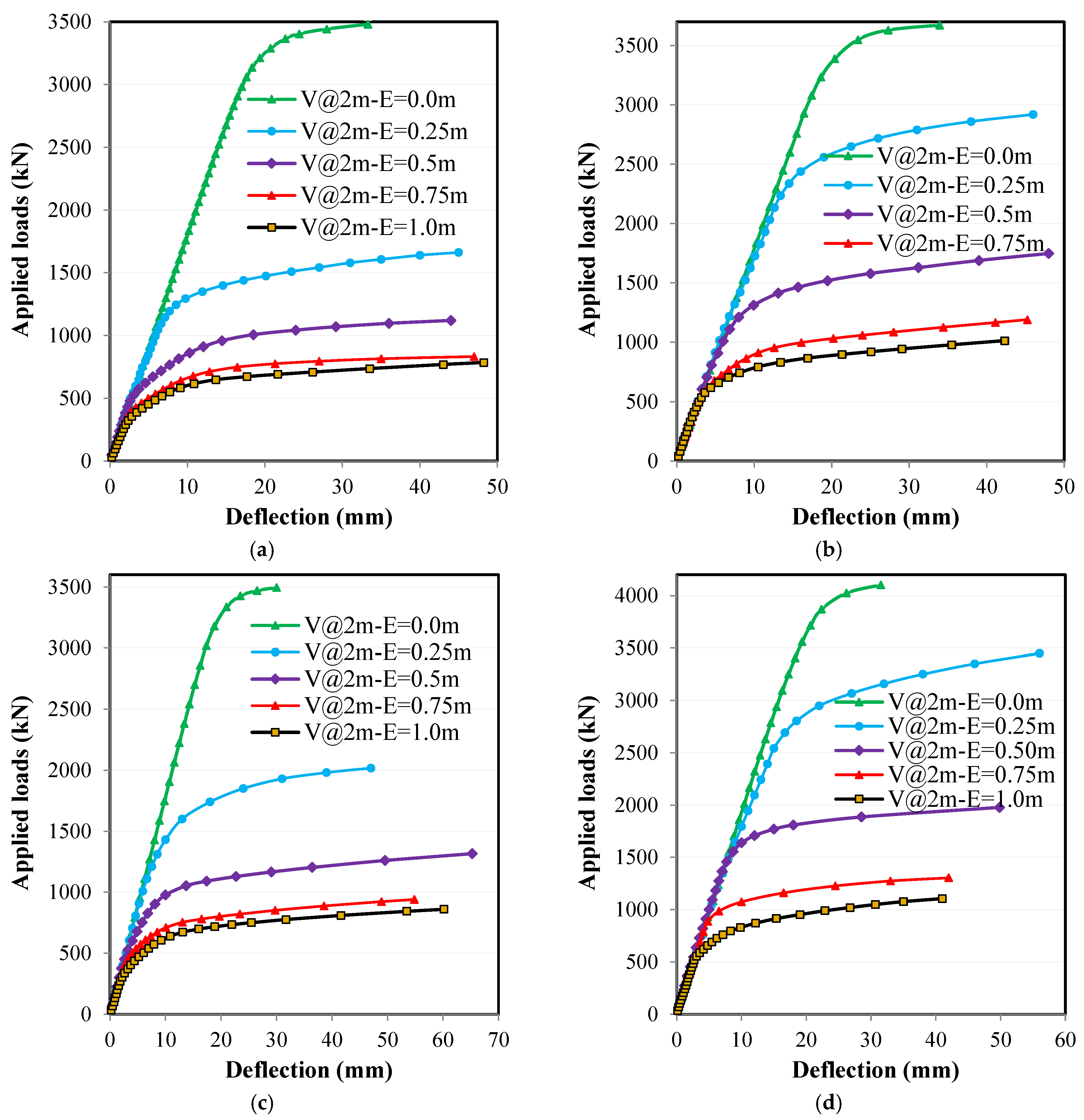

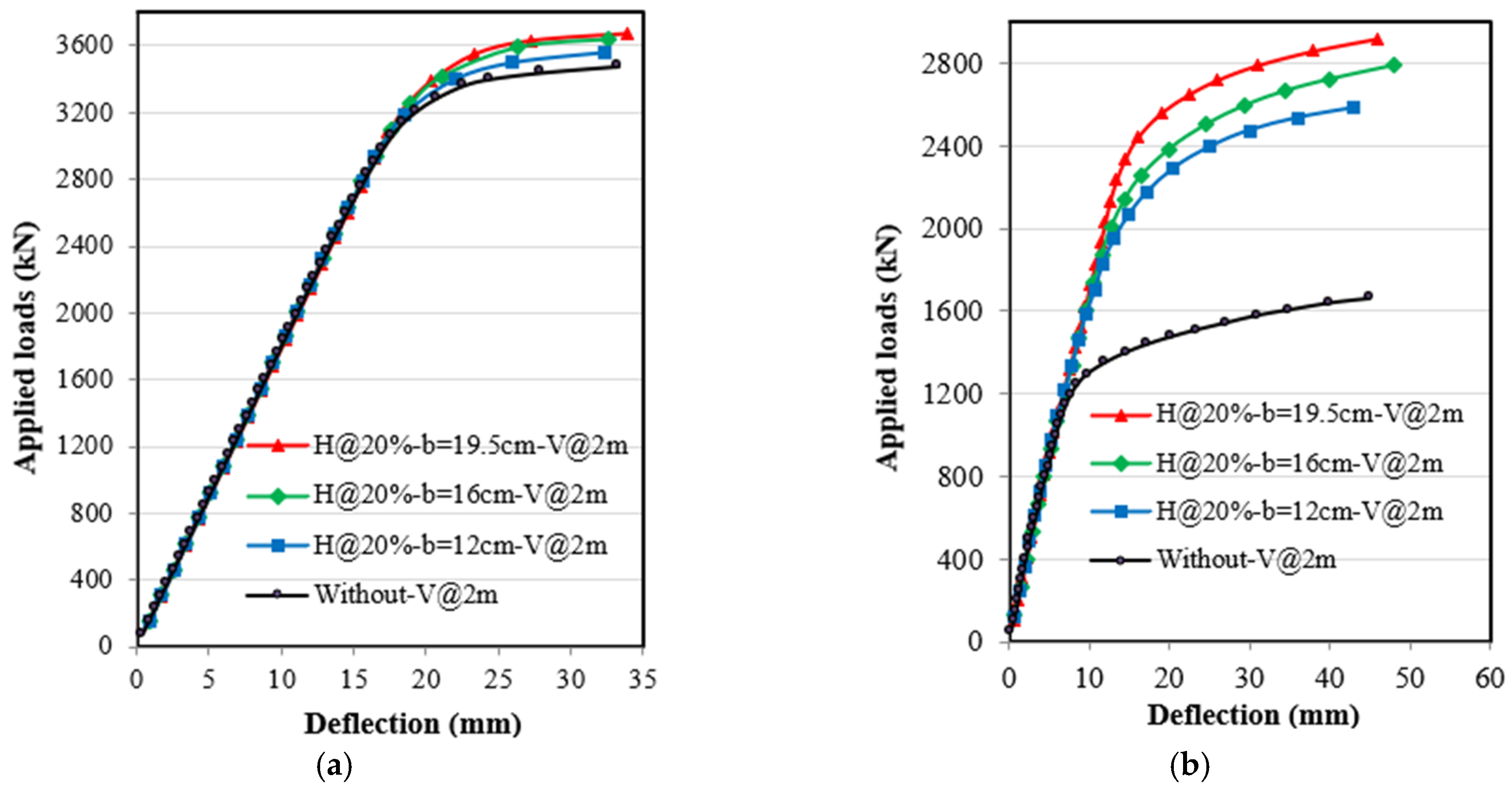

4.1. Applied Loads and Deflection Relationships

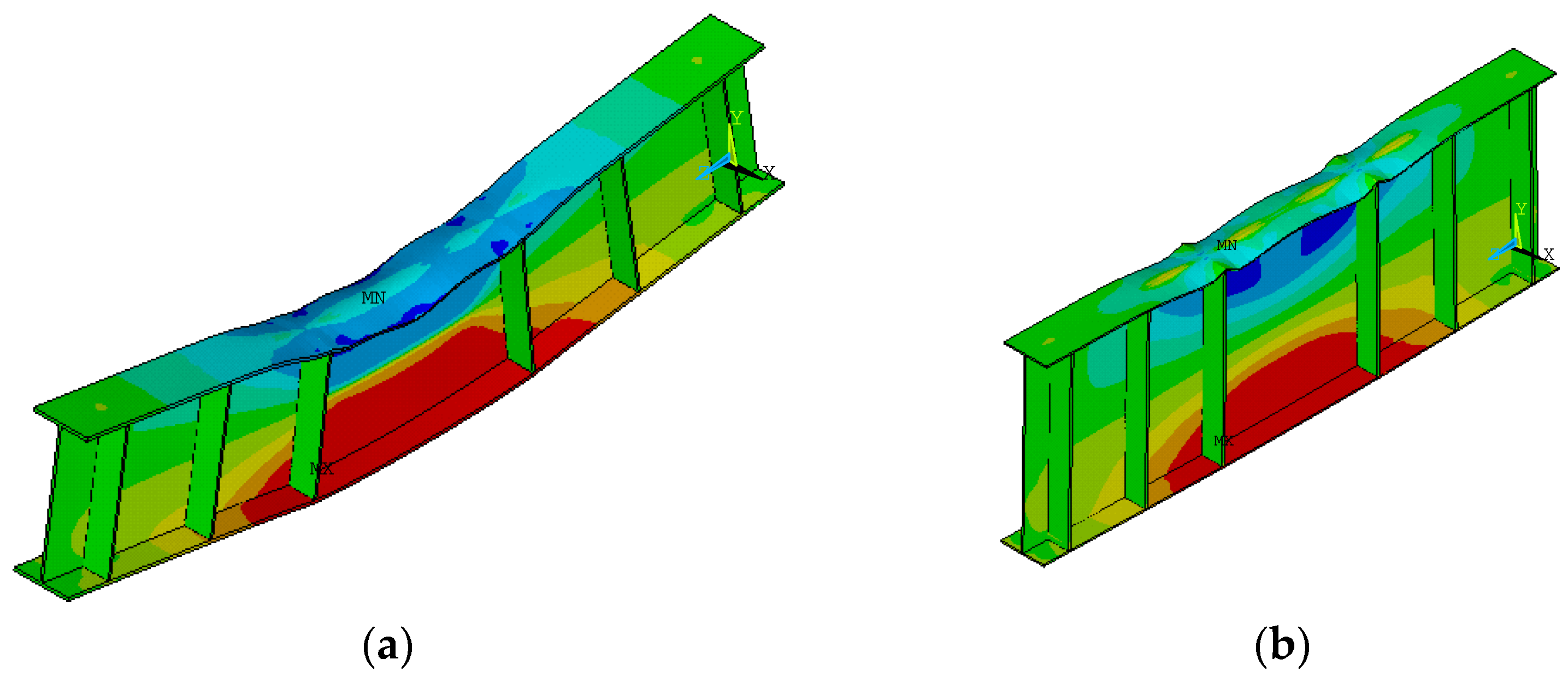

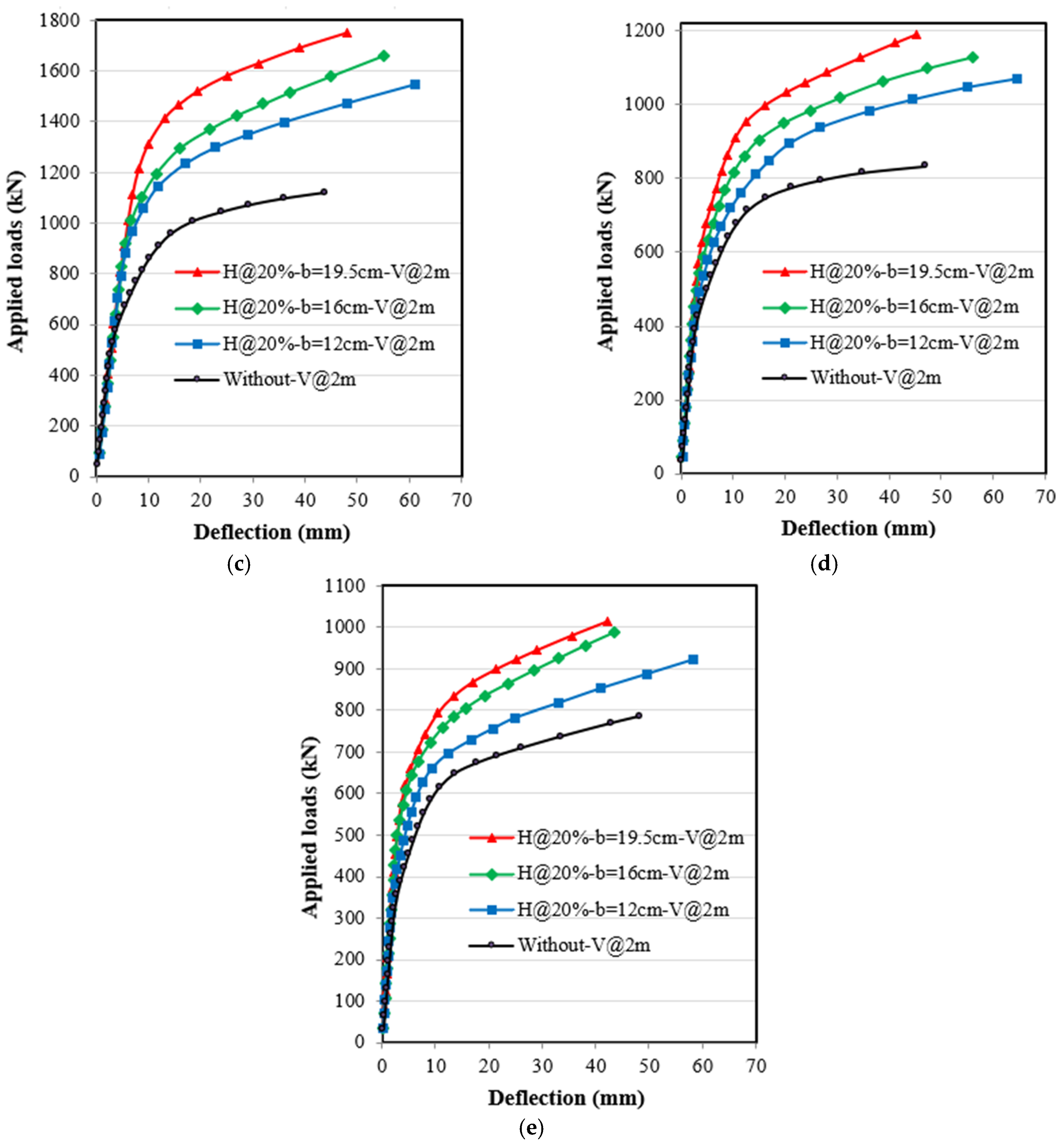

4.2. Effect of Horizontal Stiffeners on Deformation Patterns and Stress Distributions

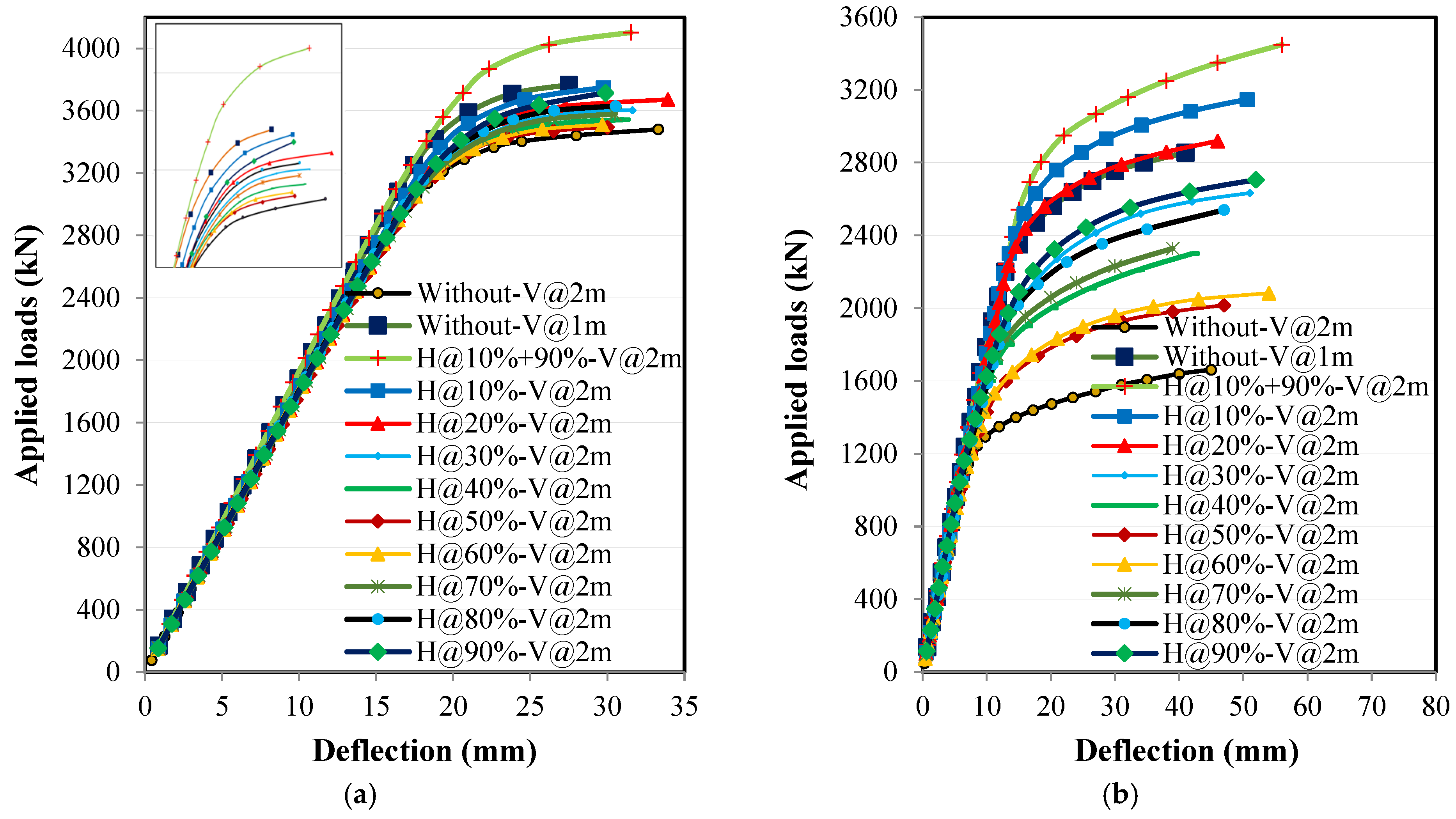

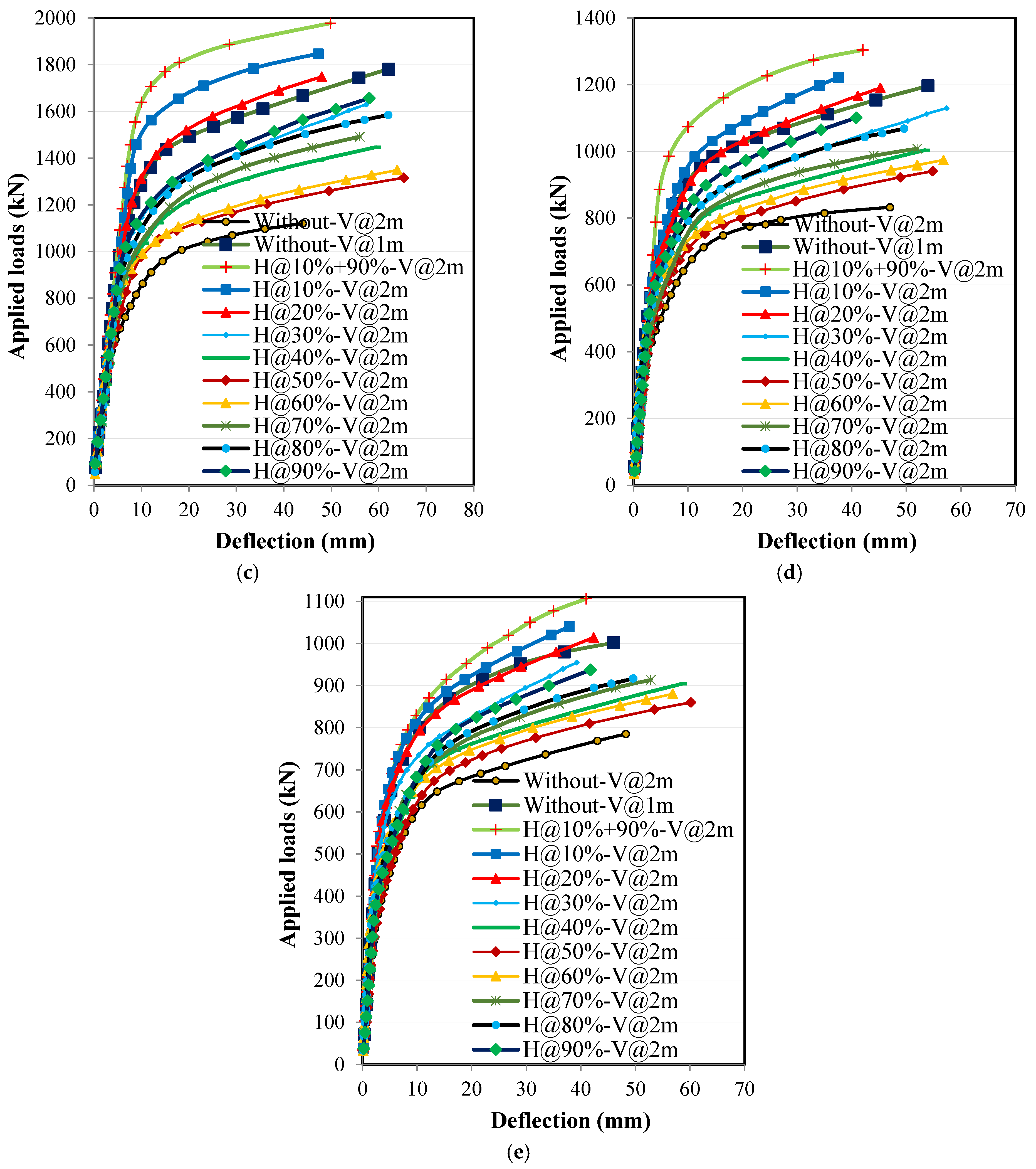

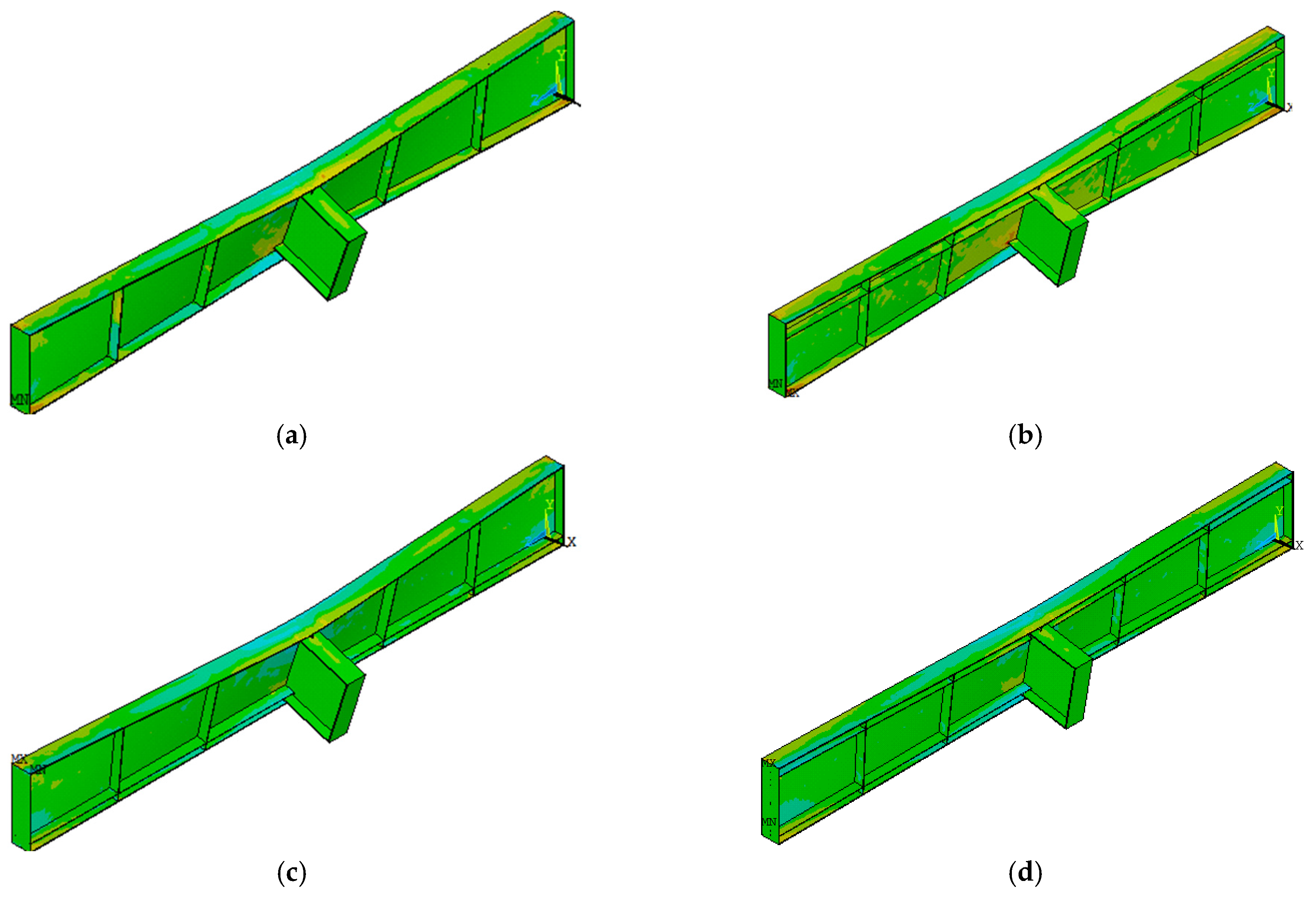

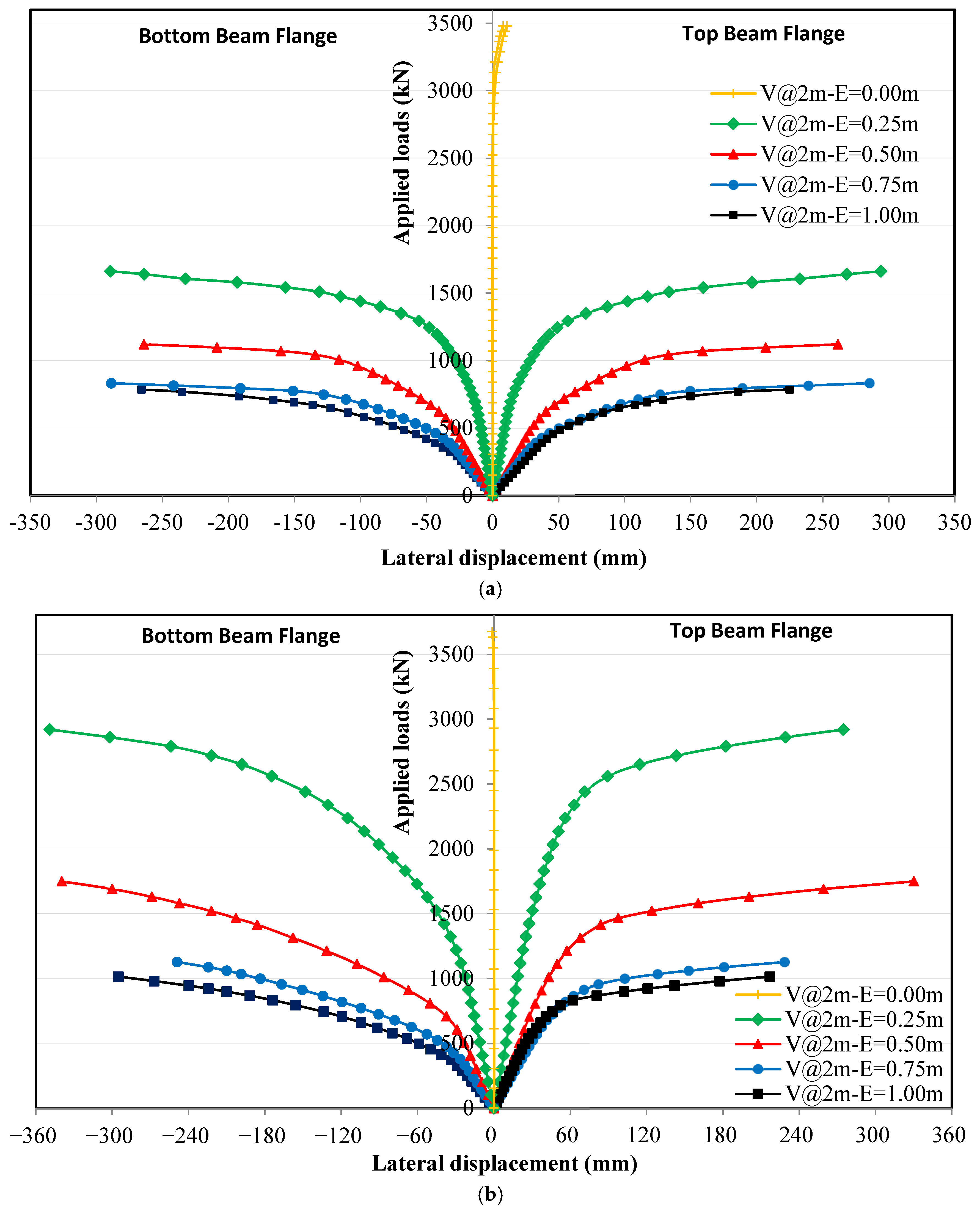

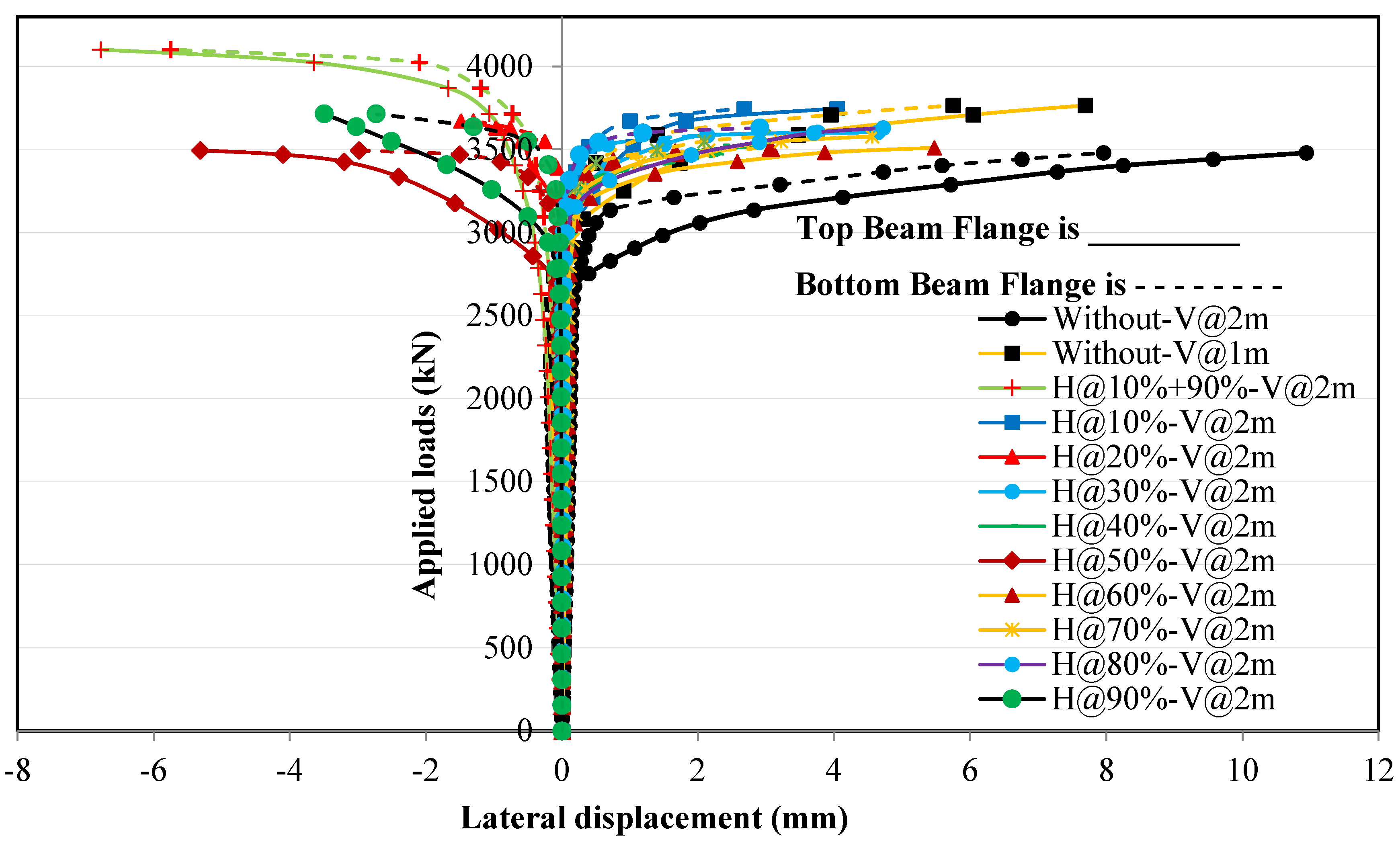

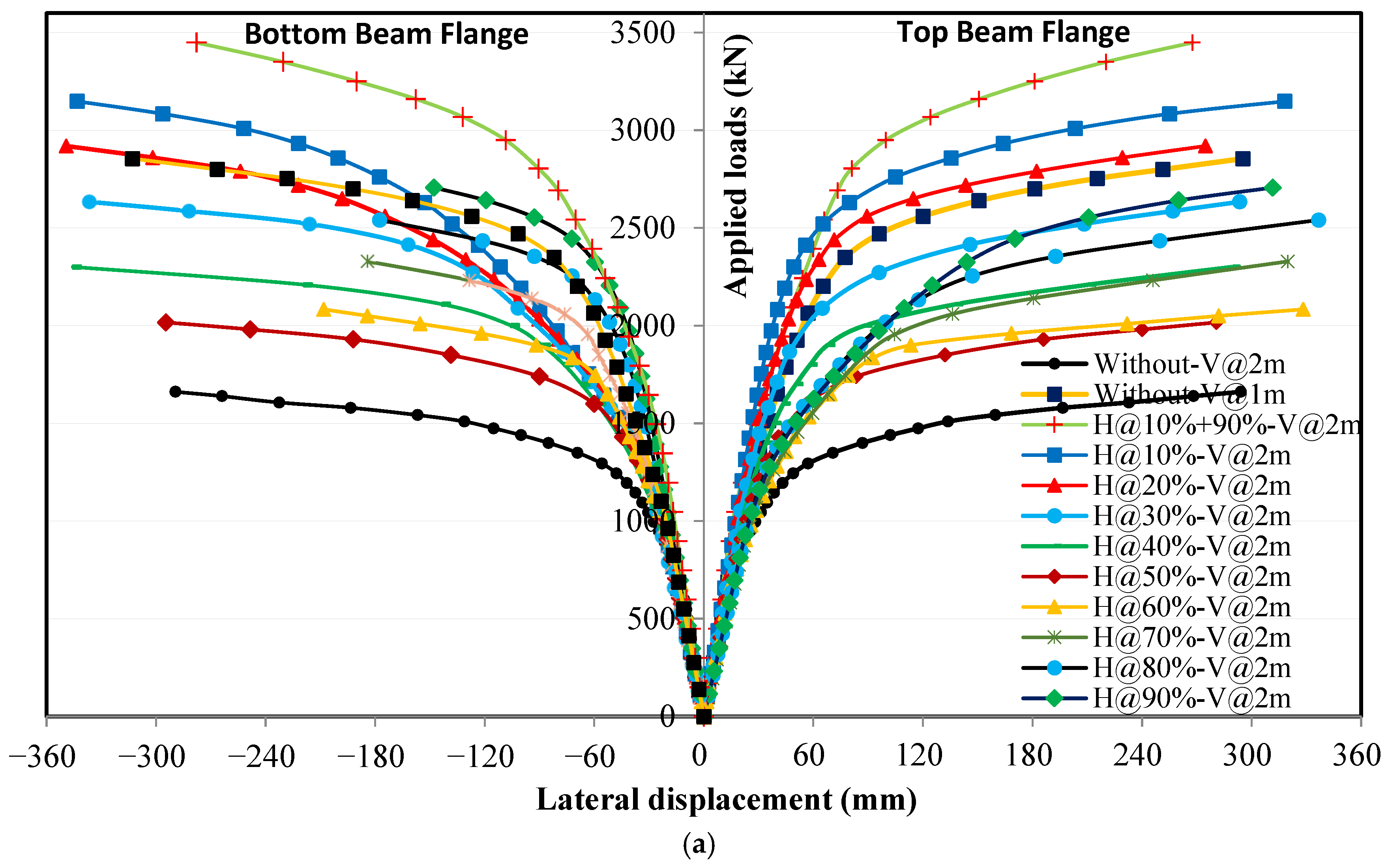

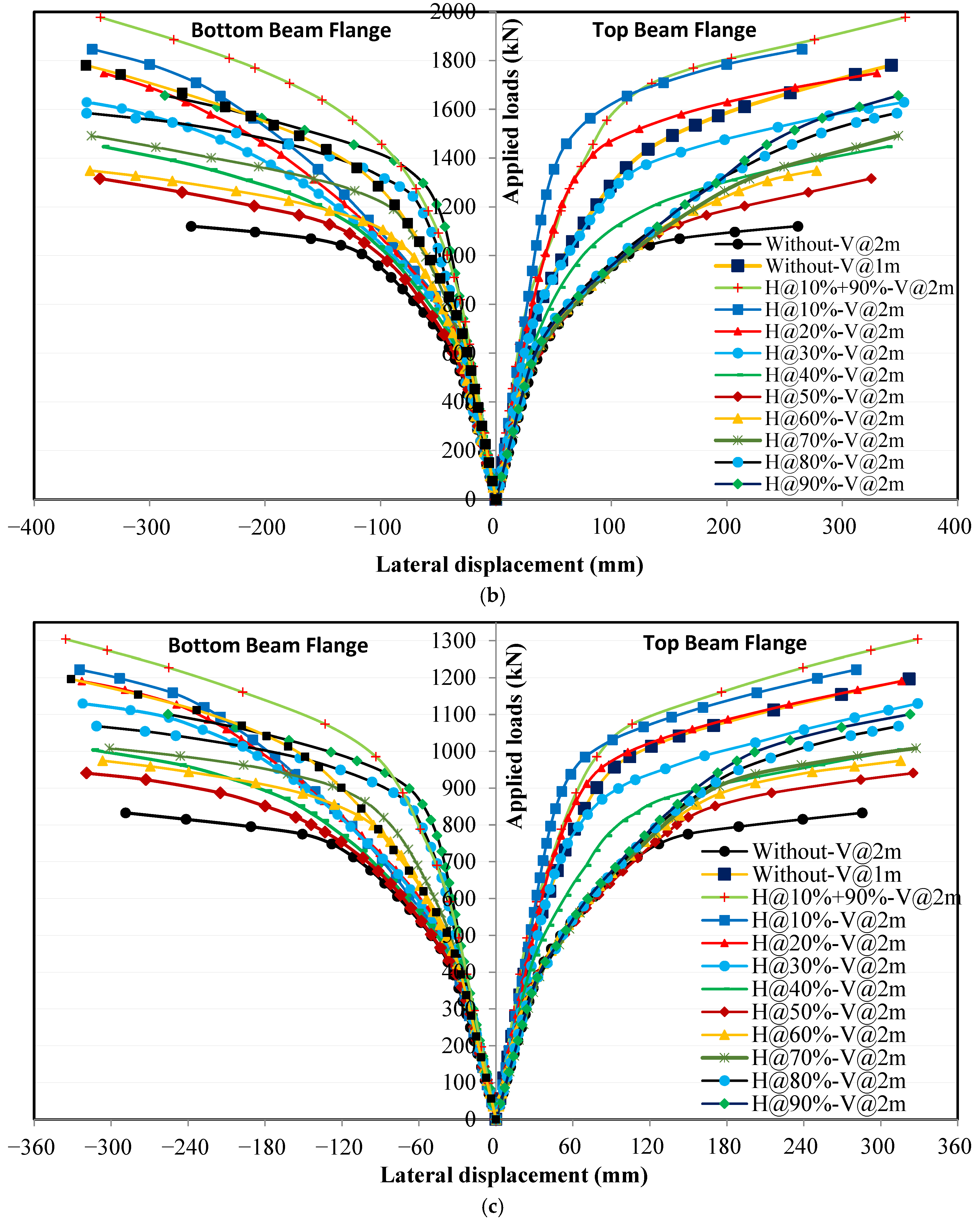

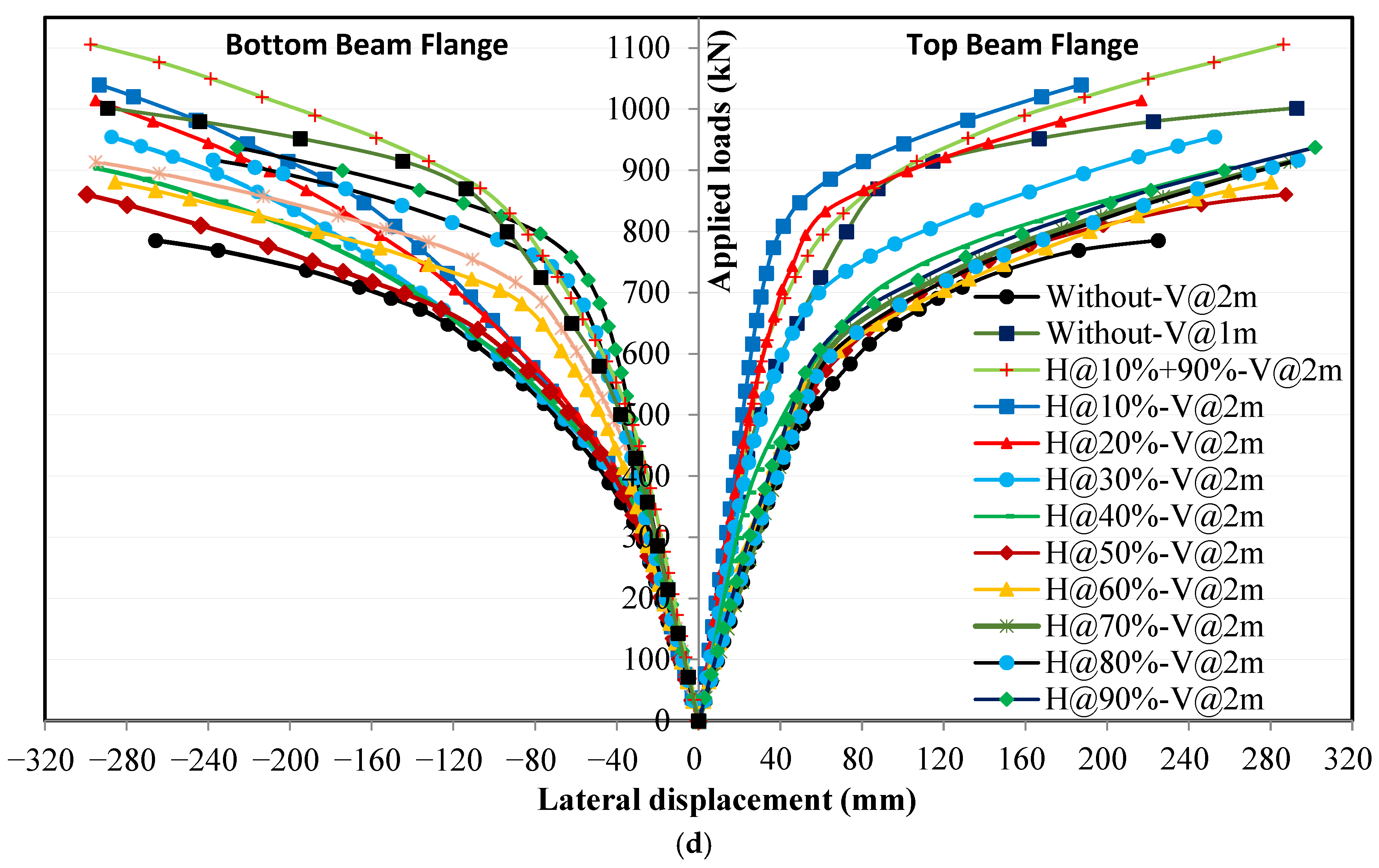

4.3. Effect of Horizontal Stiffeners on Applied Loads and Lateral Displacement Relationships

4.3.1. Loading Without Eccentricity

4.3.2. Loading with Eccentricity

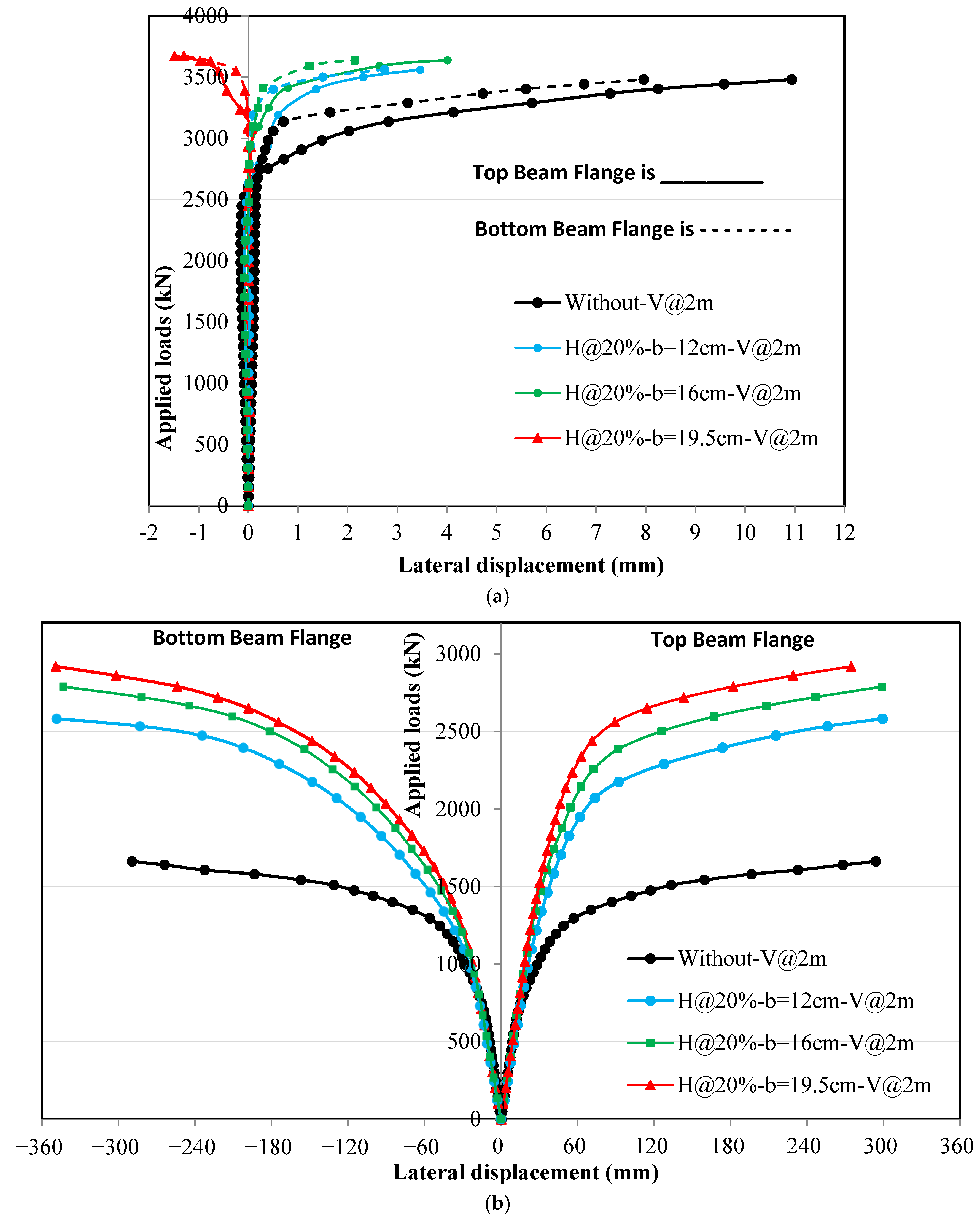

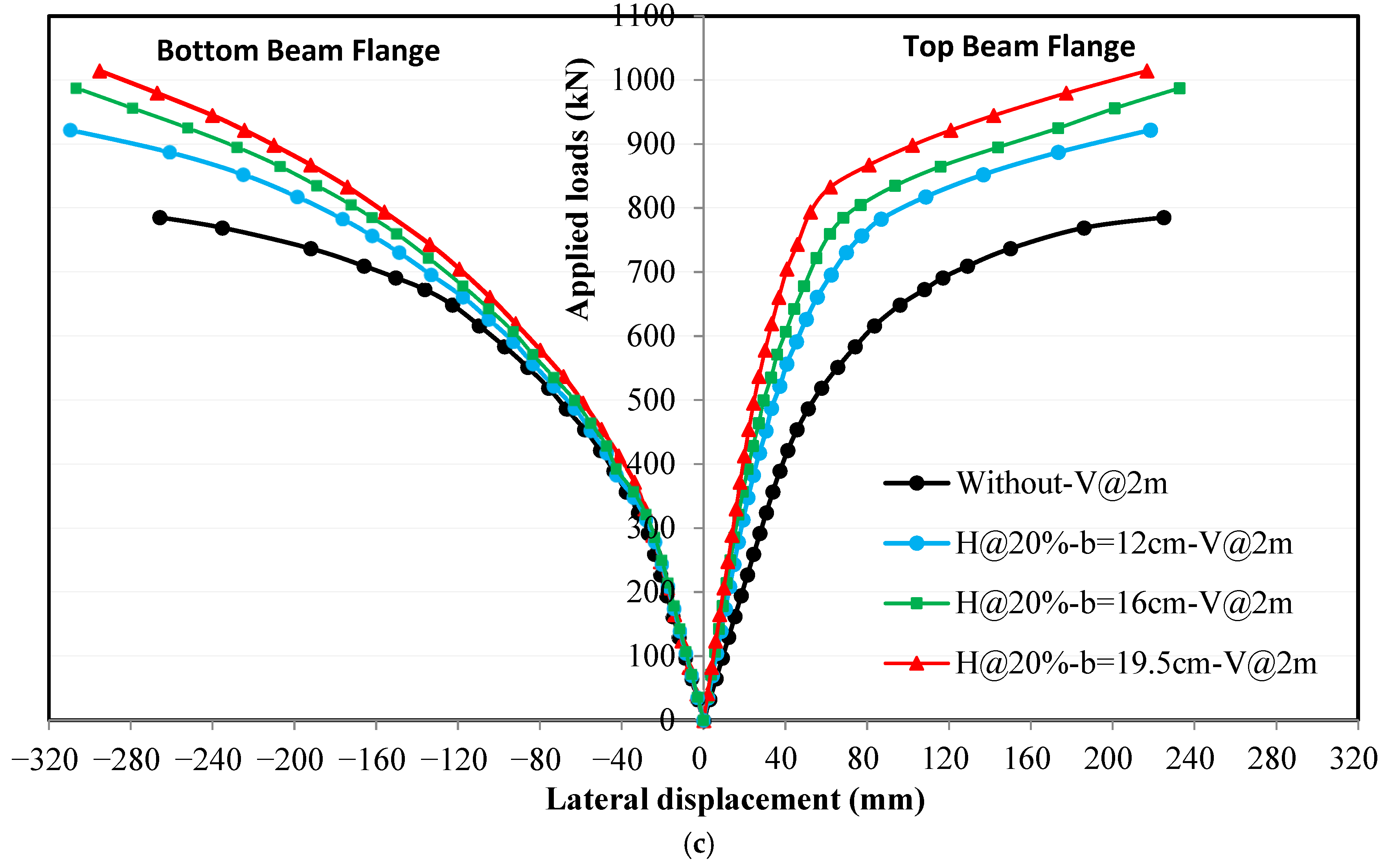

4.3.3. Effect of Horizontal Stiffeners Width

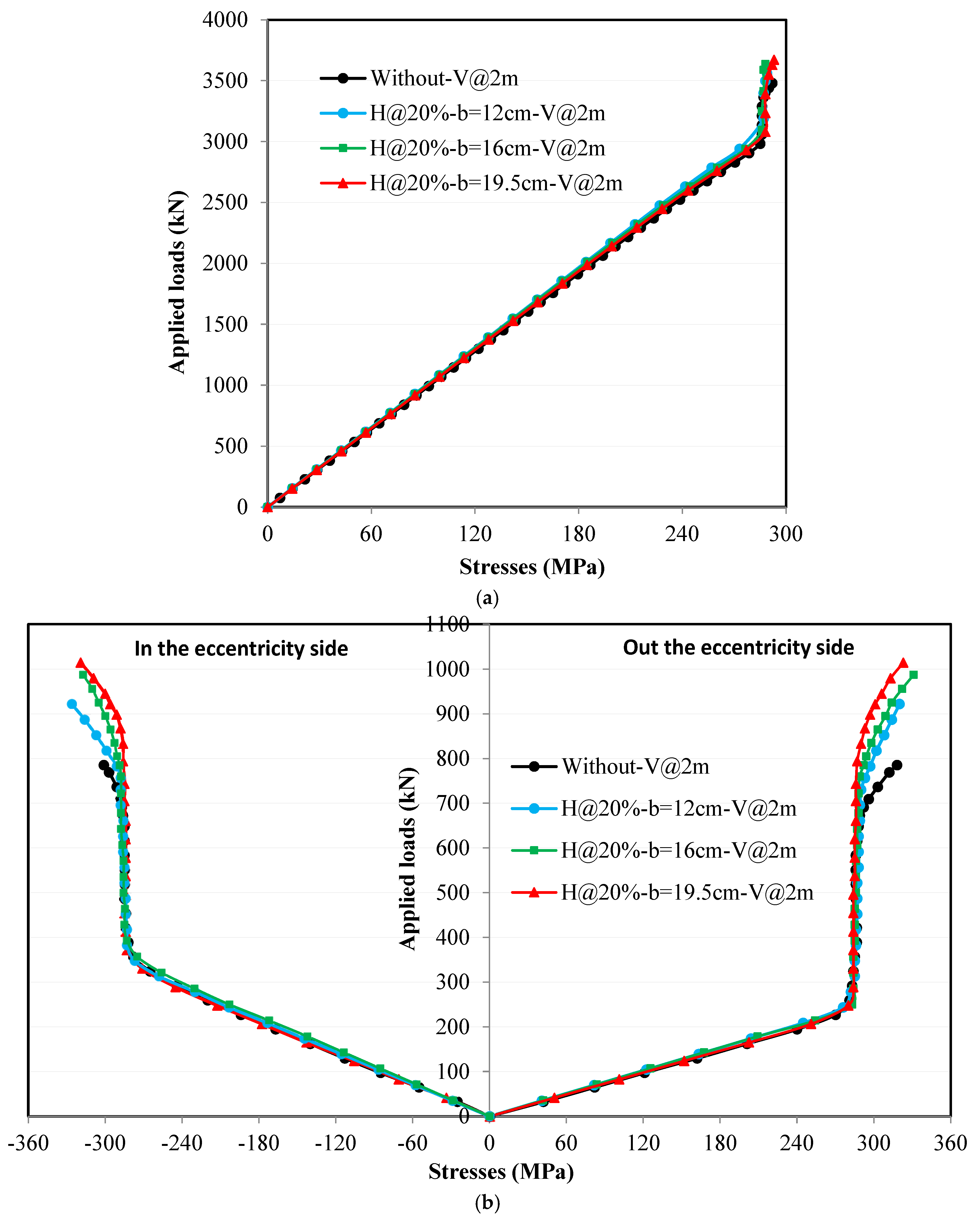

4.4. Effect of Horizontal Stiffeners on Stress Distribution in the Upper Flanges

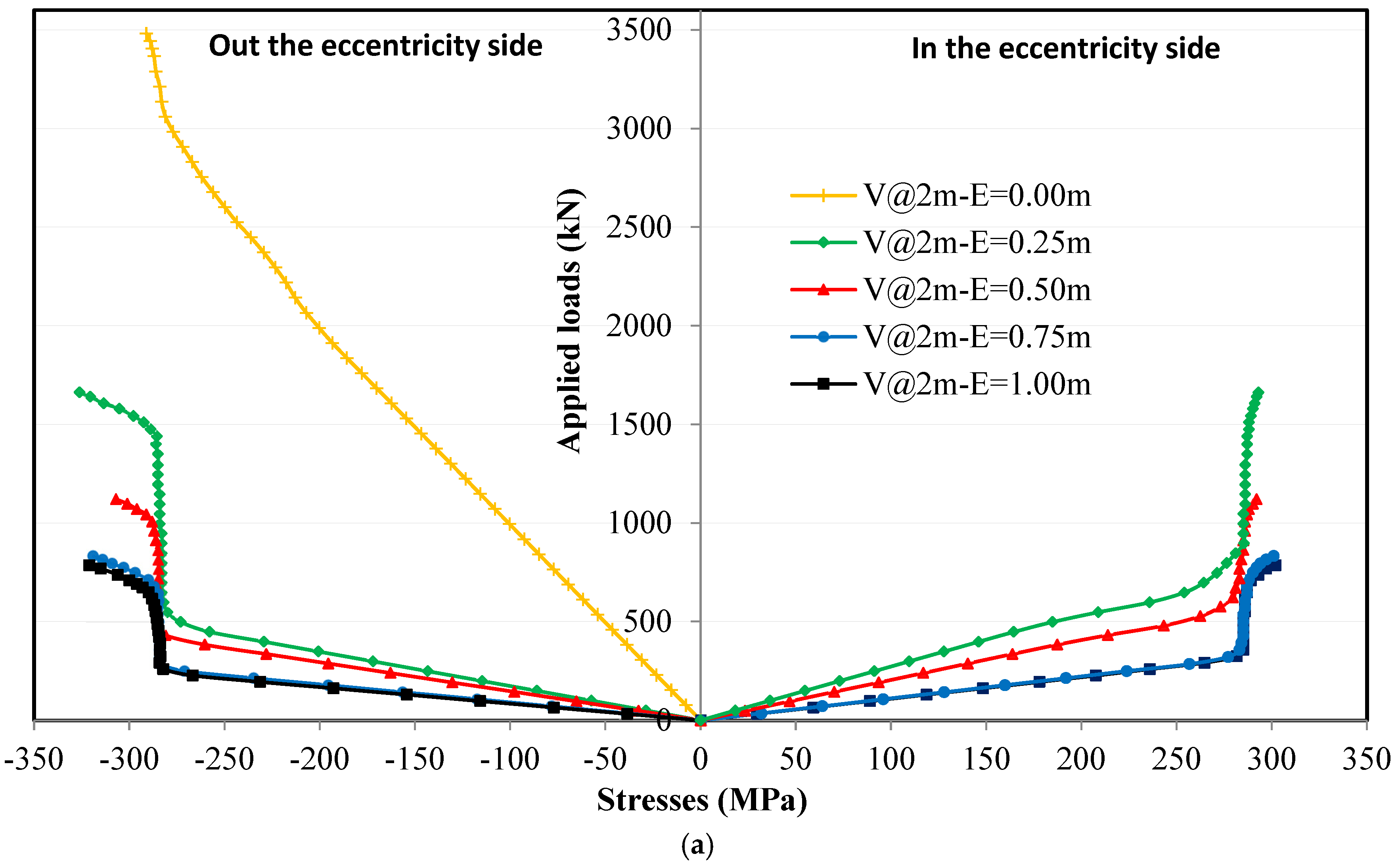

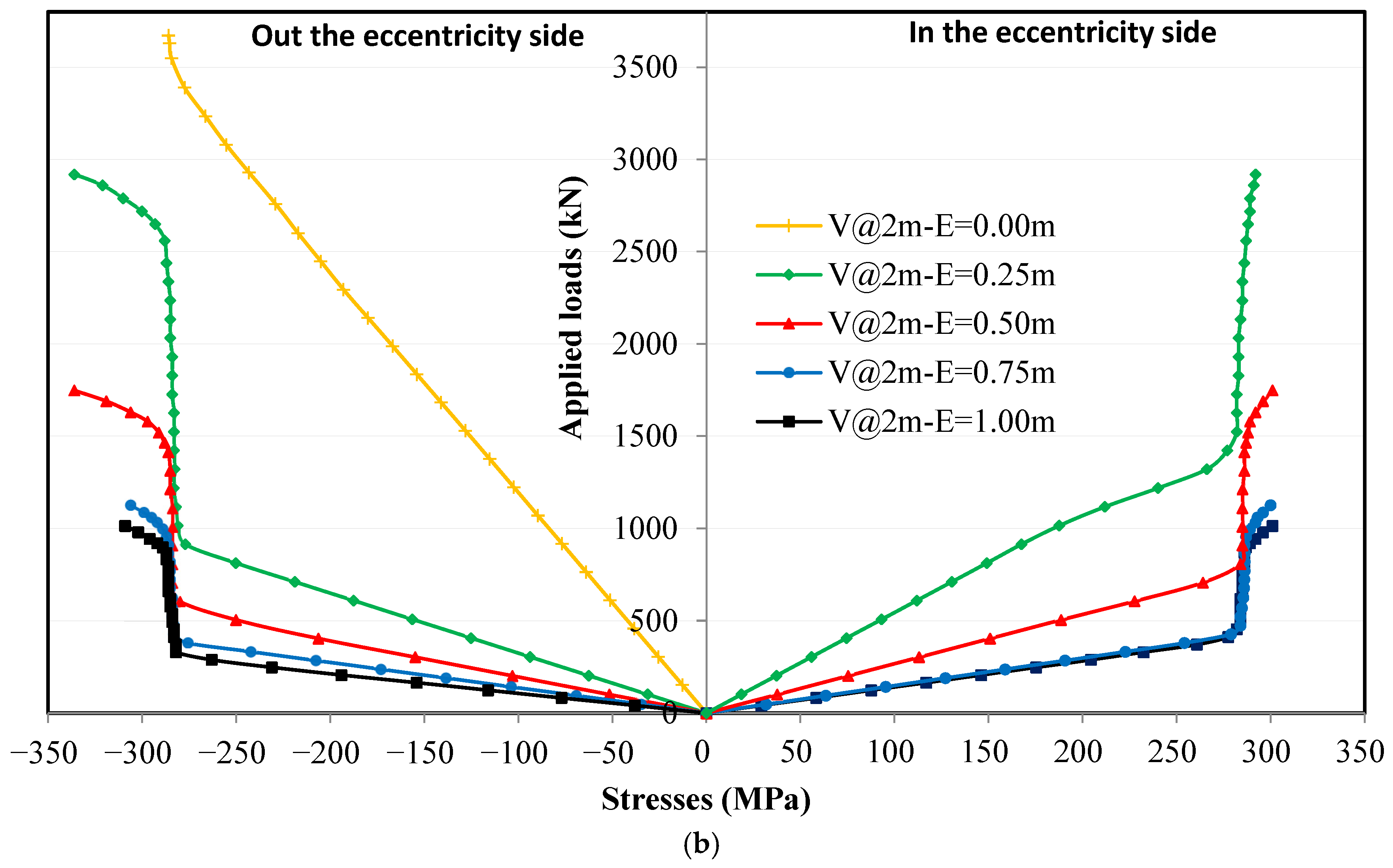

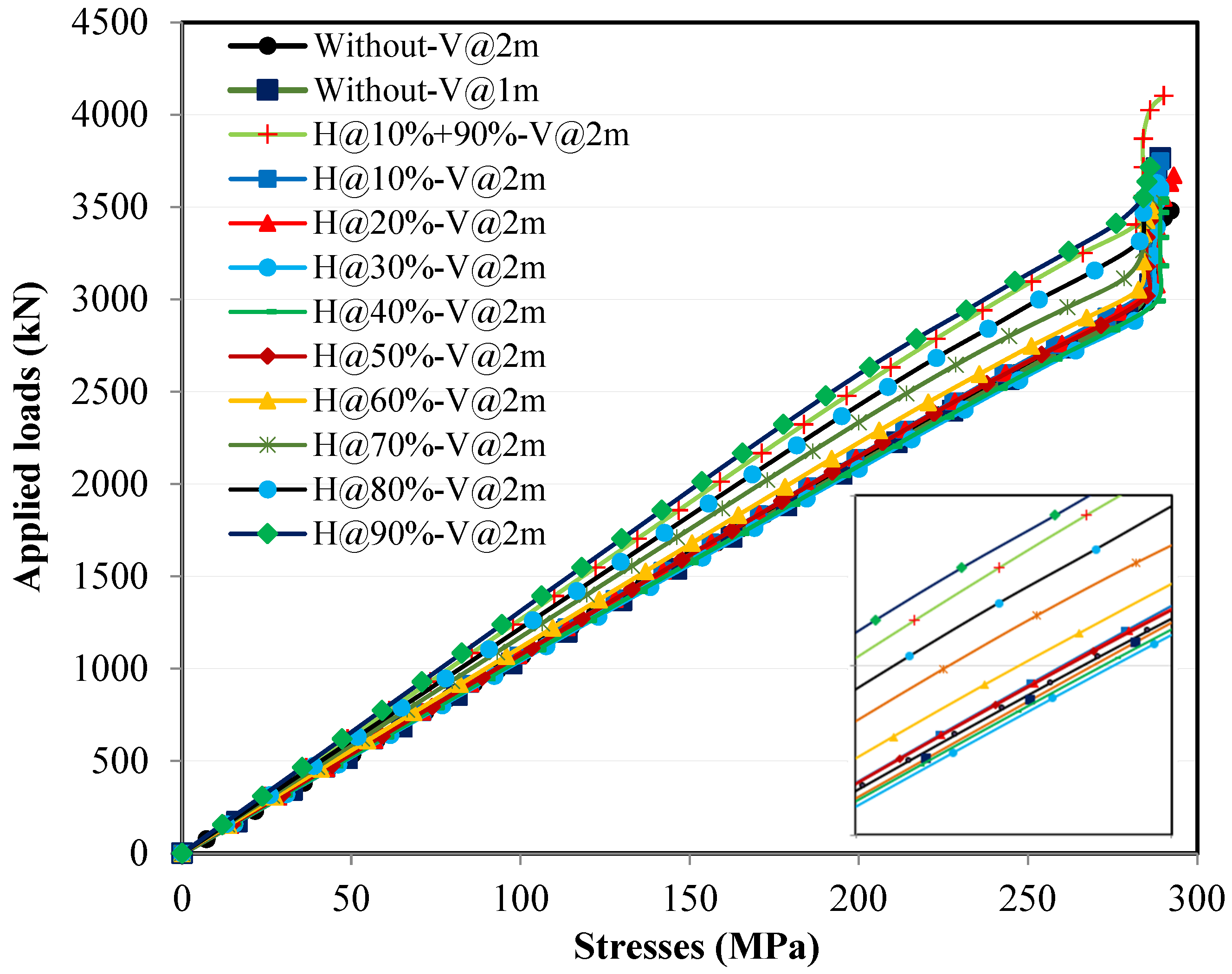

4.4.1. Loading Without Eccentricity

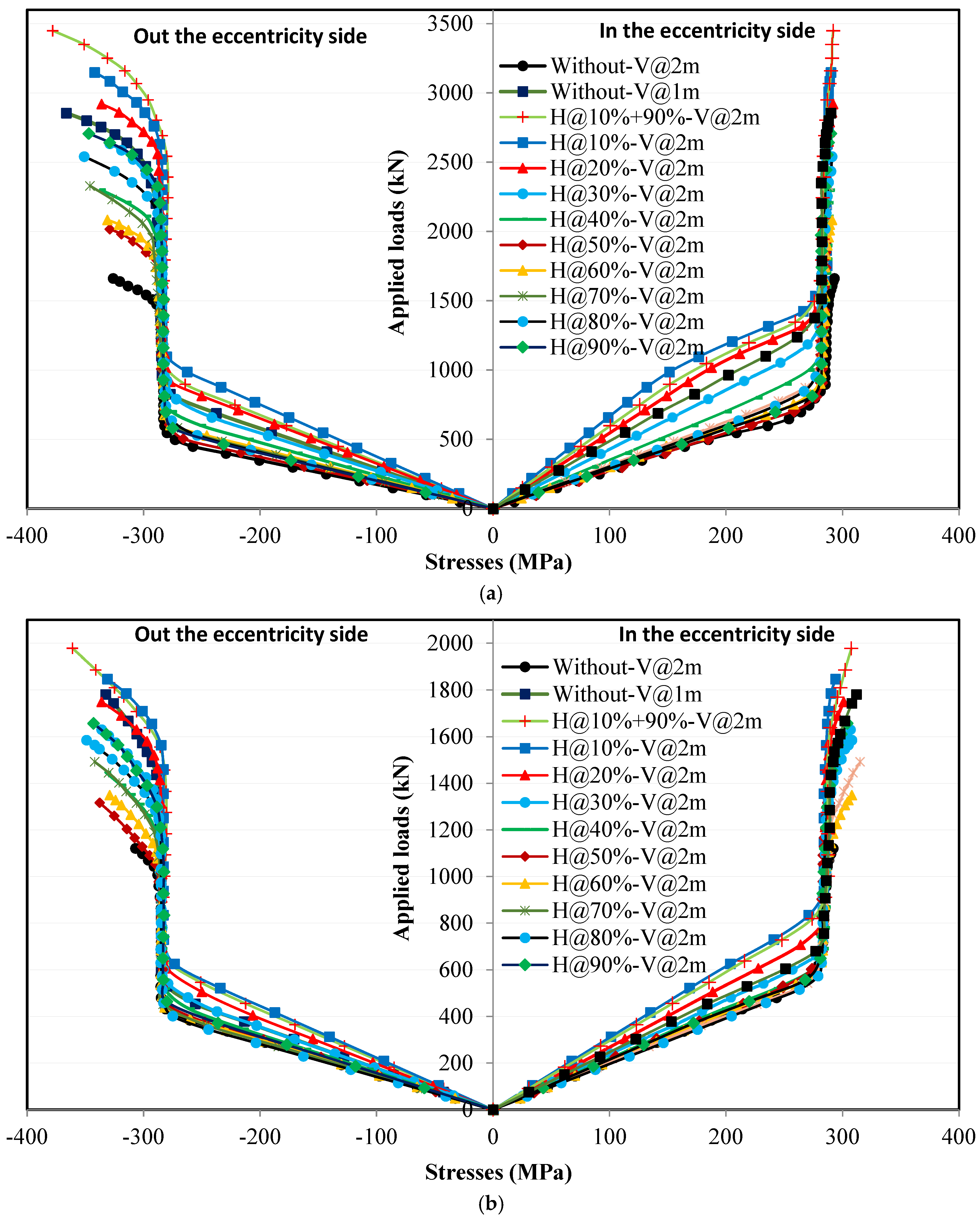

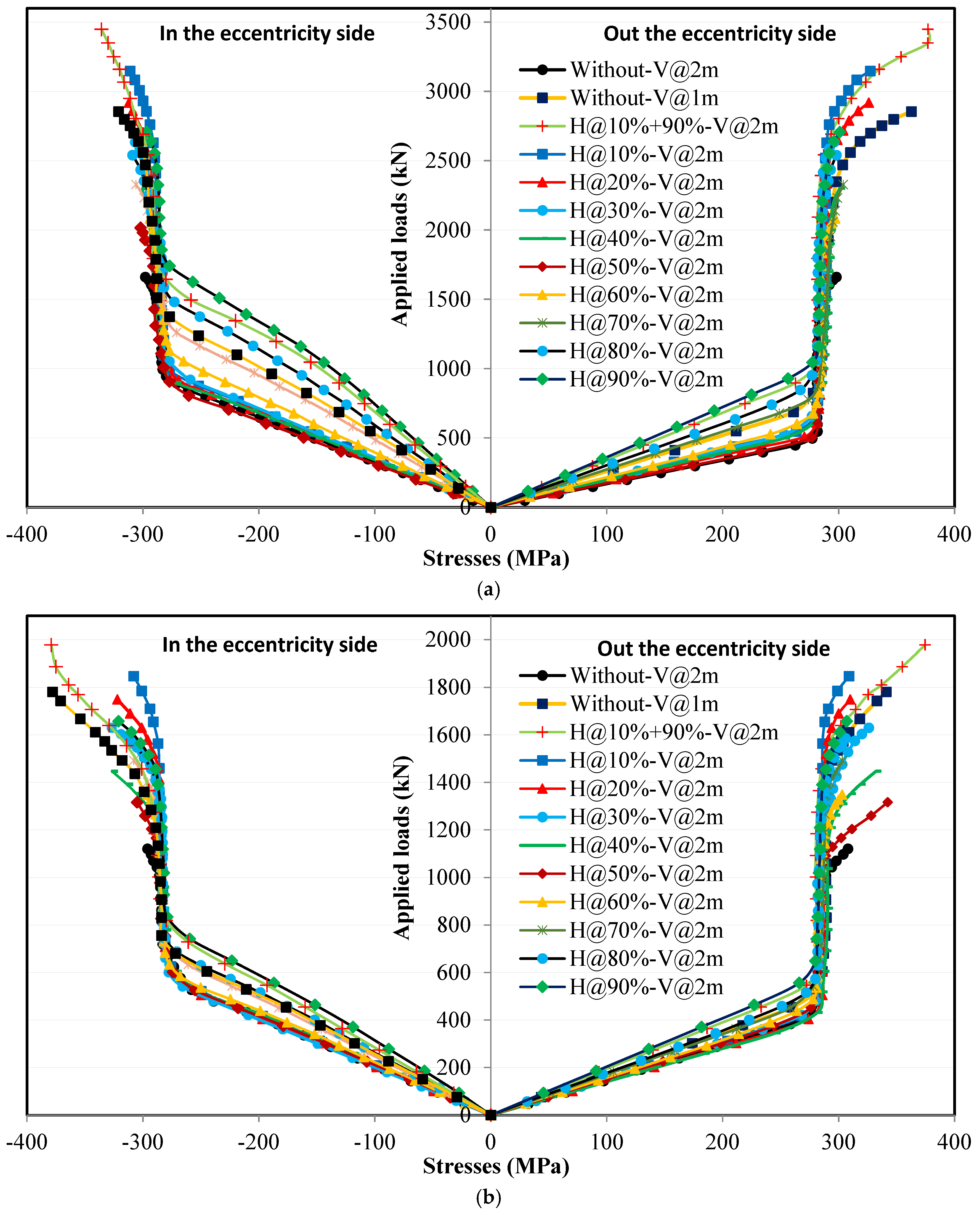

4.4.2. Loading with Eccentricity

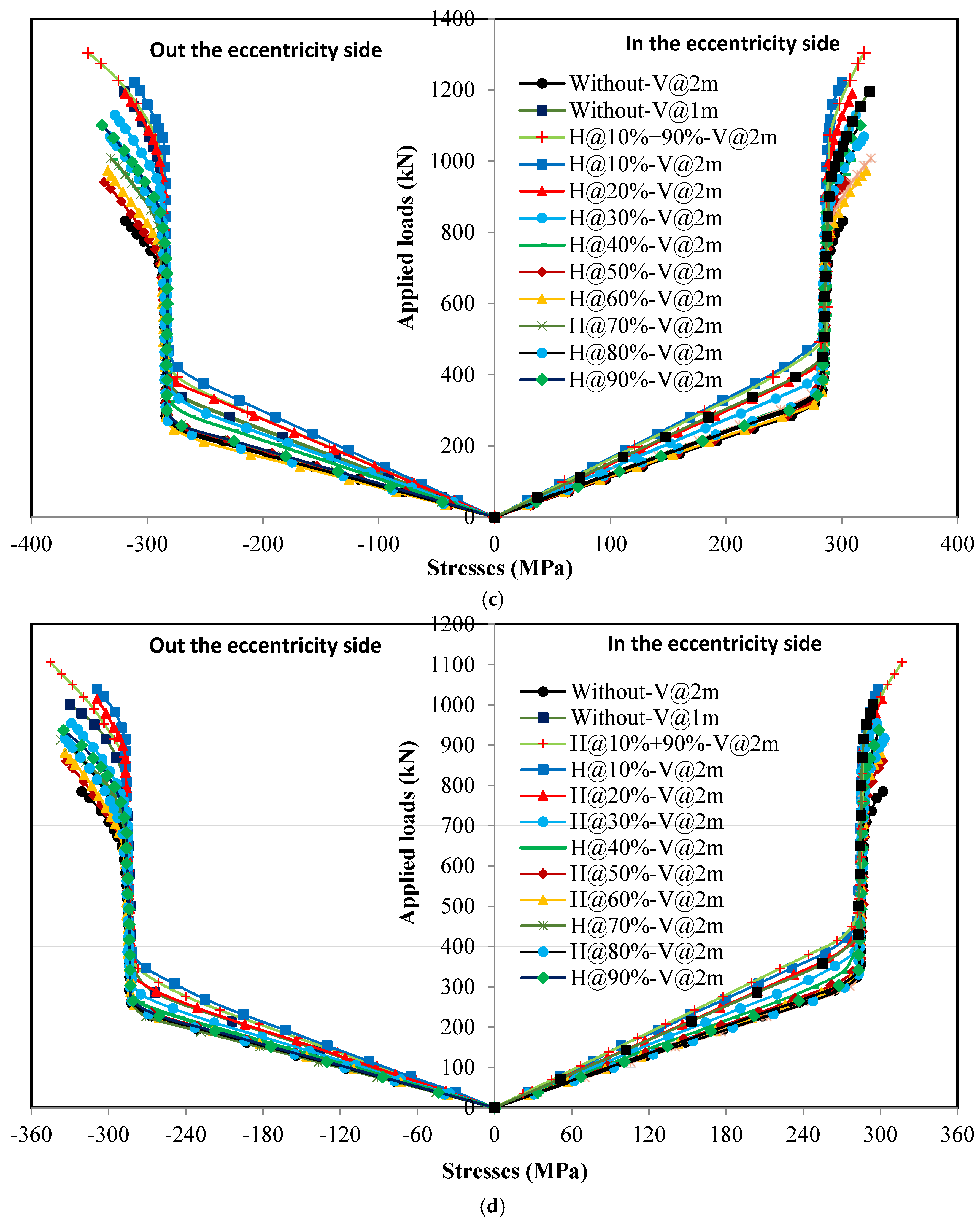

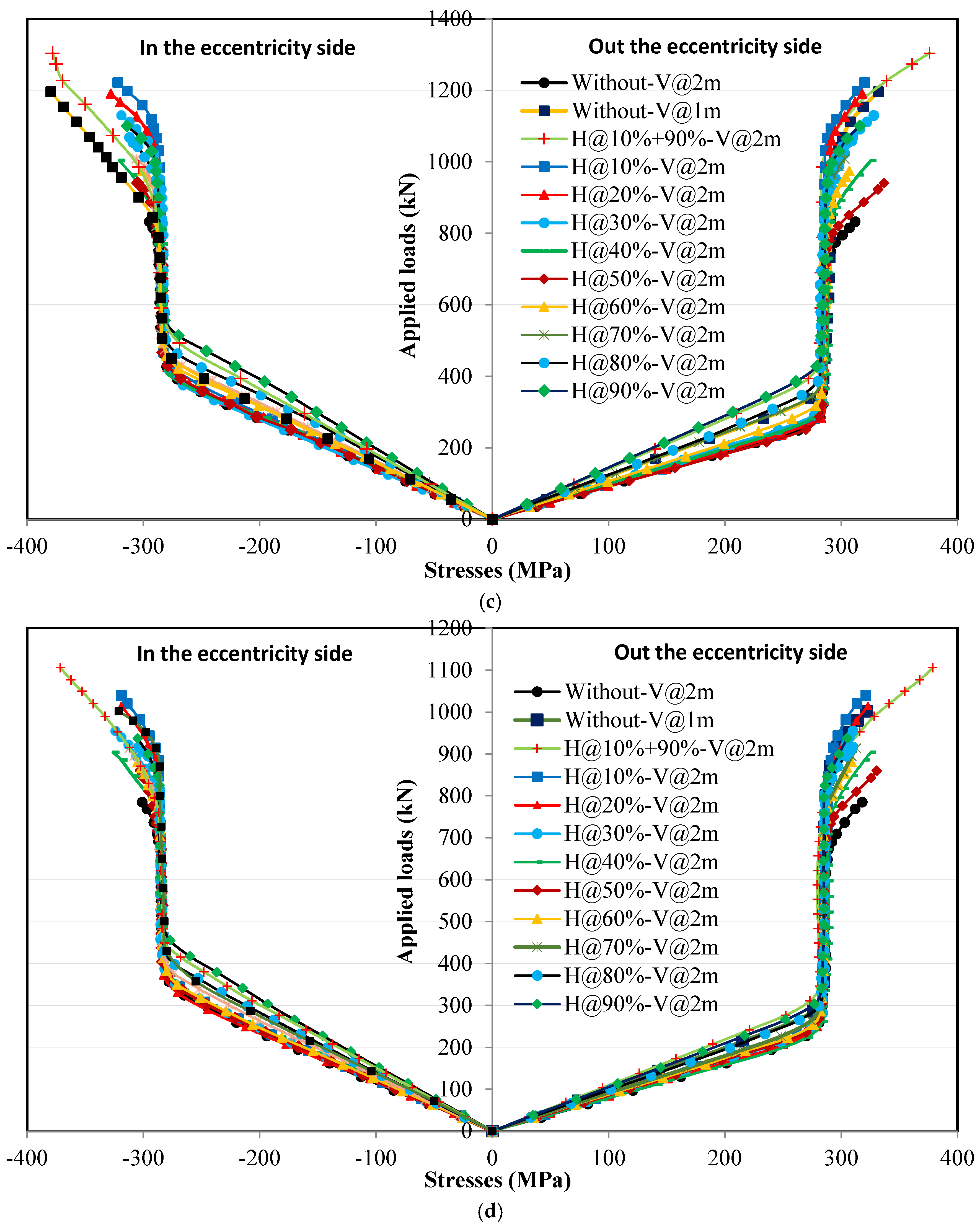

4.4.3. Effect of Horizontal Stiffeners Width

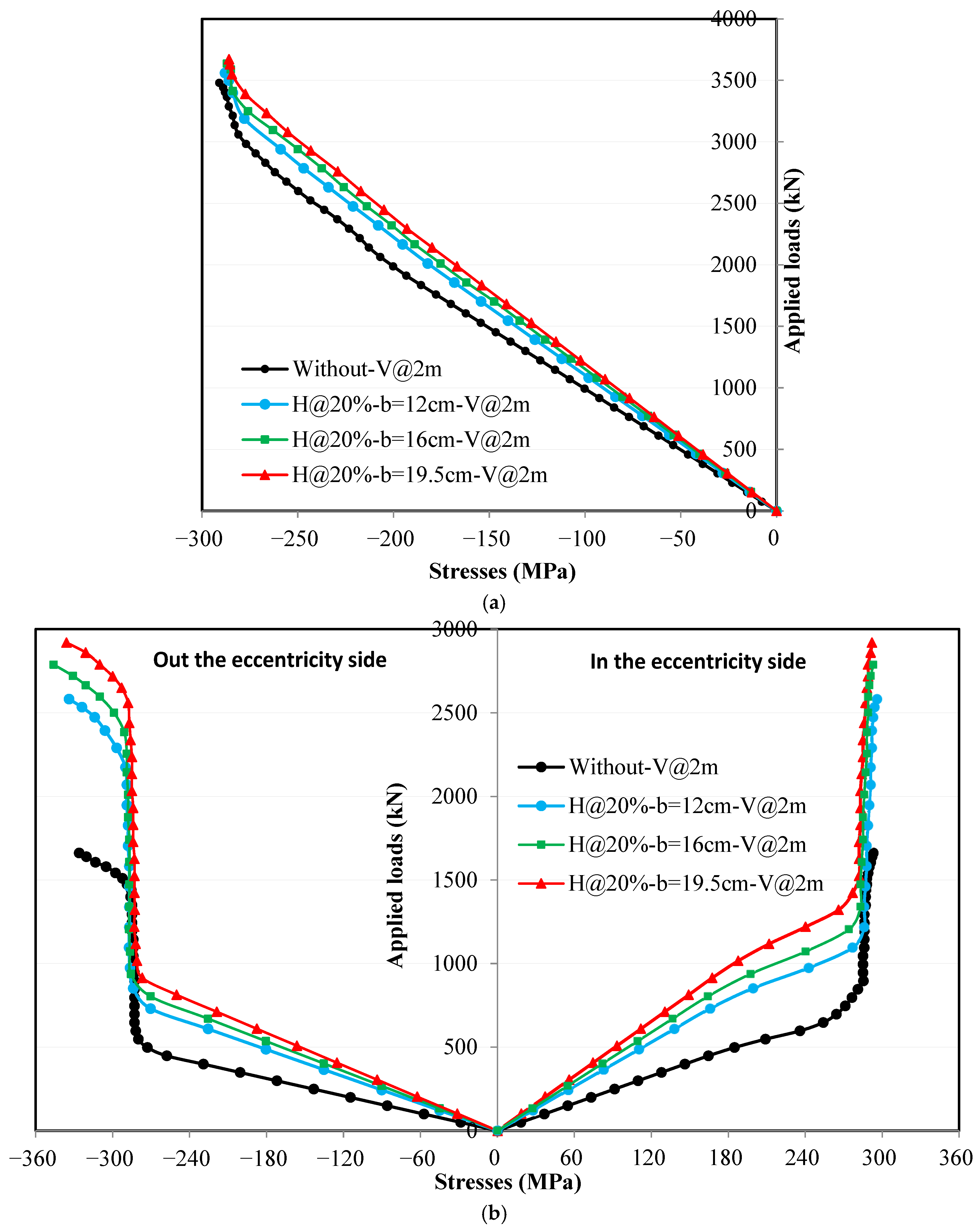

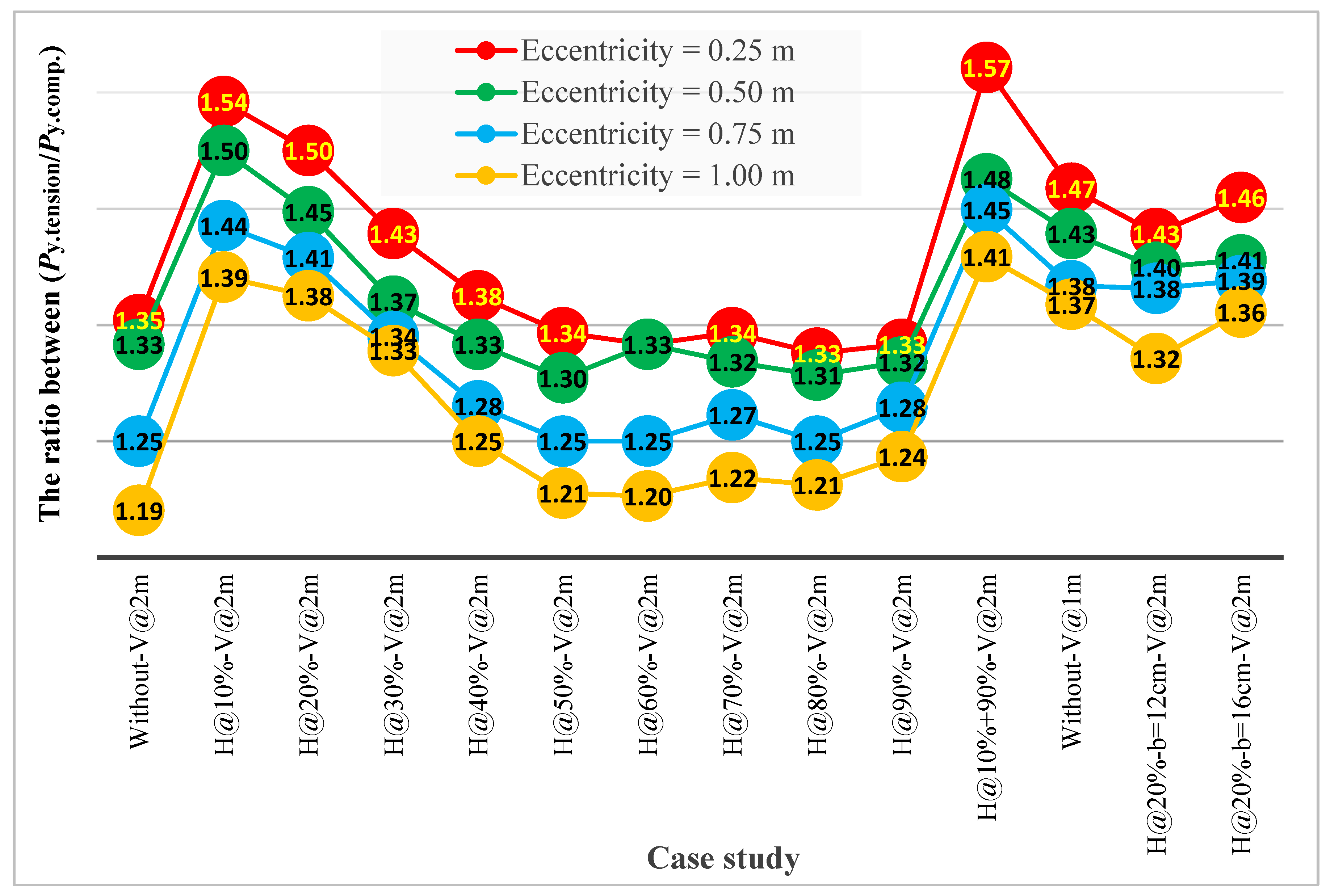

4.4.4. Effect of Eccentricity and Horizontal Stiffeners on the Onset of Yield Stresses at the Edges of the Upper Flange

4.5. Effect of Horizontal Stiffeners on Stress Distribution in the Lower Flanges

4.5.1. Loading Without Eccentricity

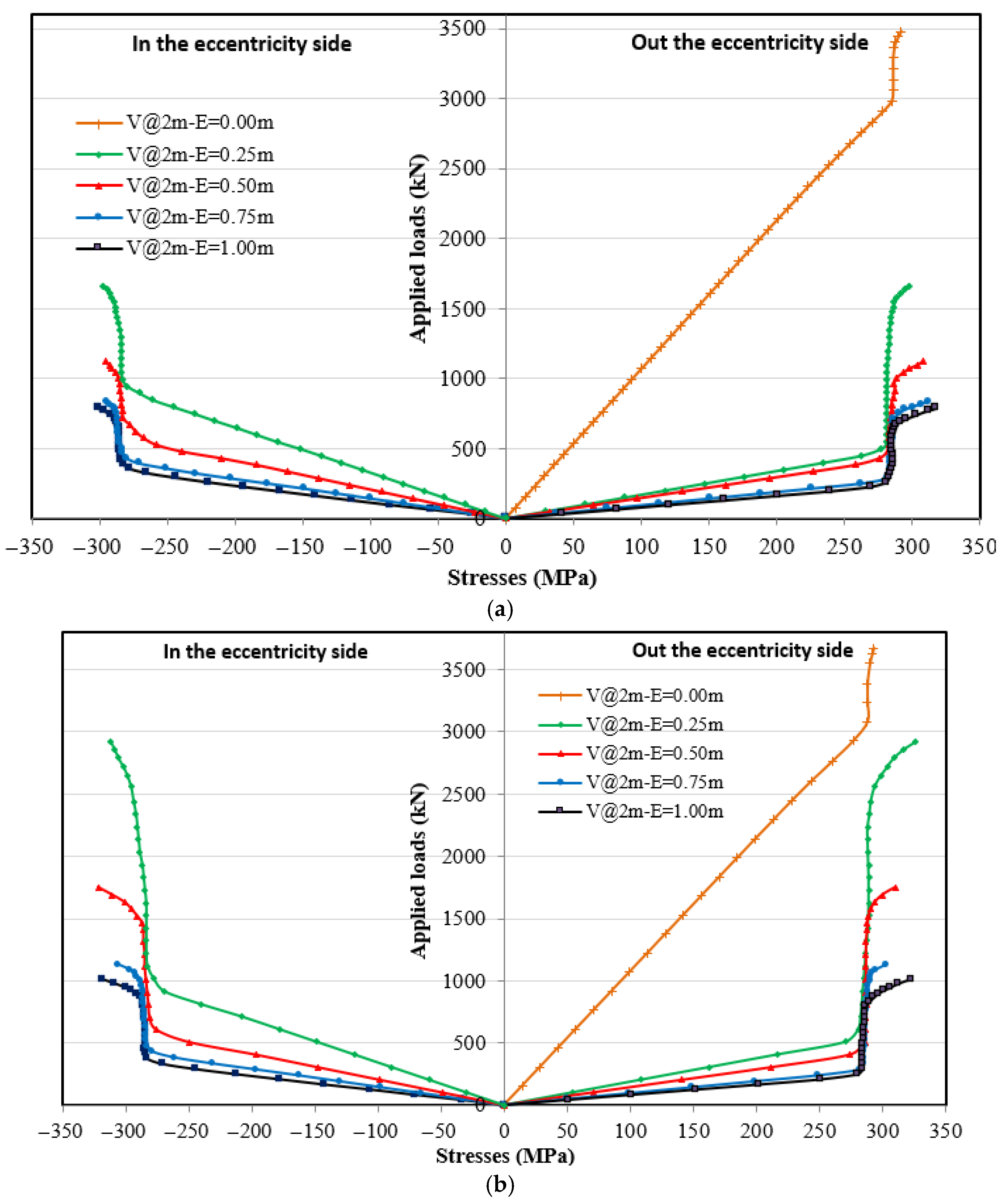

4.5.2. Loading with Eccentricity

4.5.3. Effect of Horizontal Stiffeners Width

4.5.4. Effect of Eccentricity and Horizontal Stiffeners on the Onset of Yield Stresses at the Edges of the Lower Flange

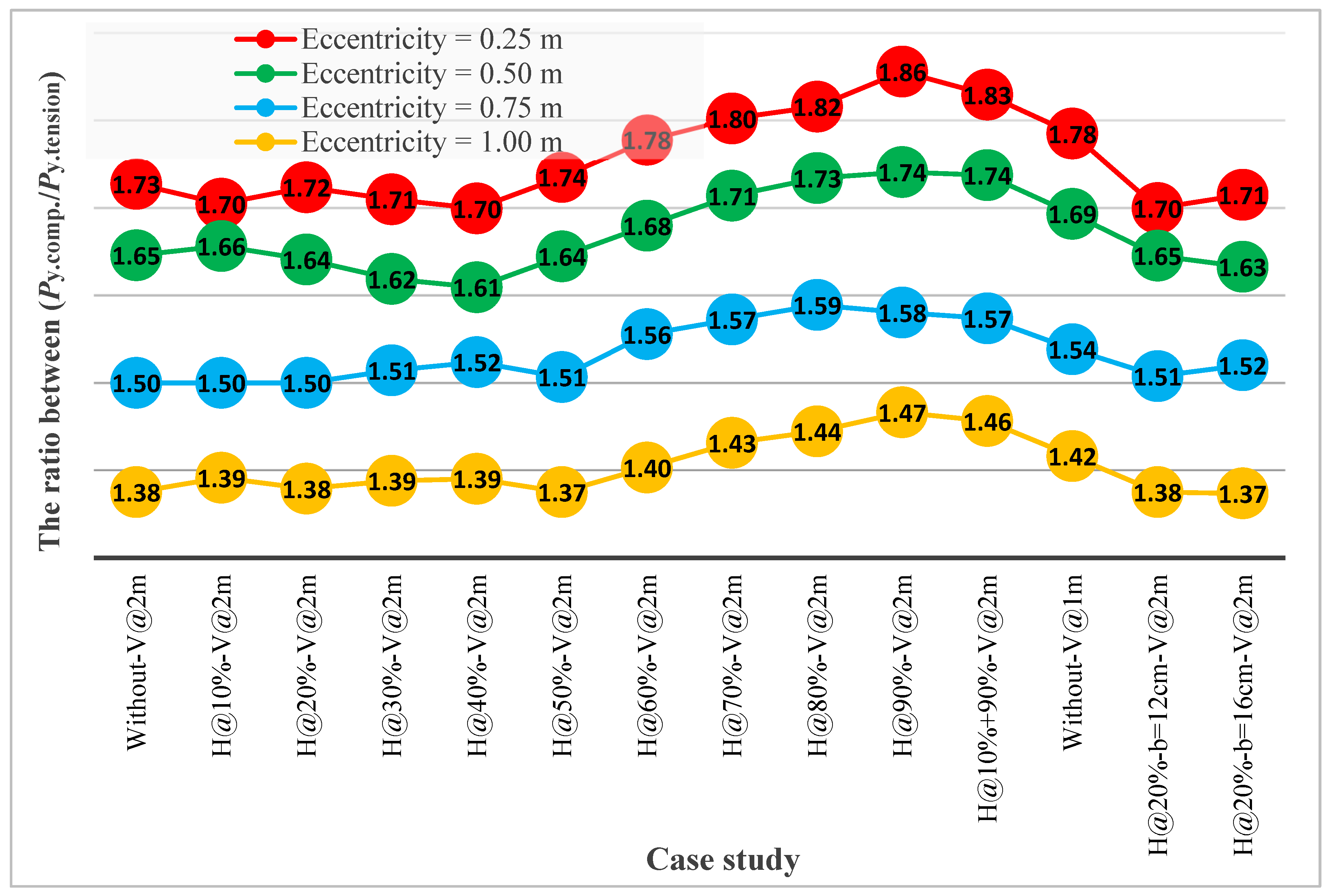

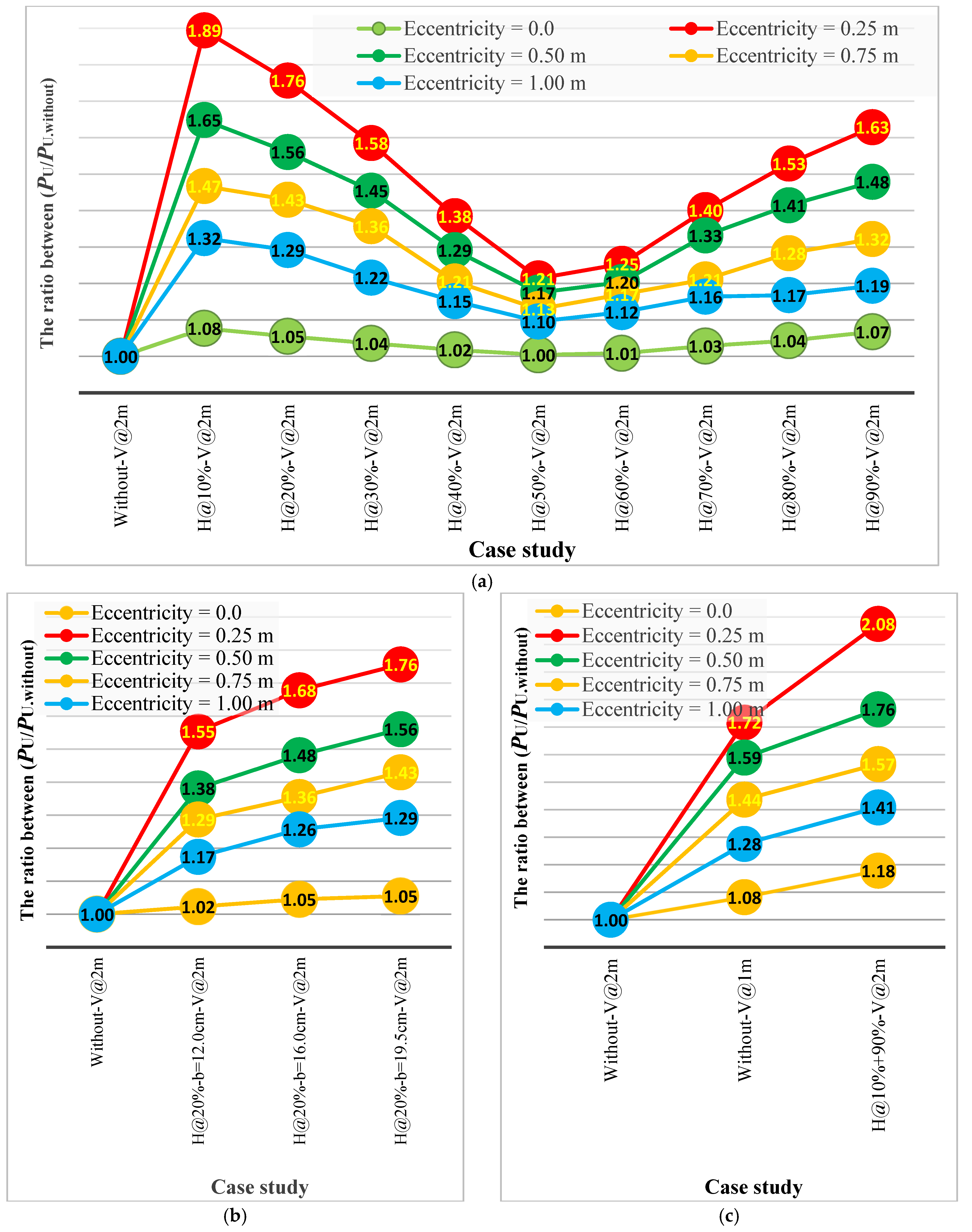

5. Effect of Horizontal Stiffeners on the Ultimate Load Capacity of Beam Under Eccentric Loads

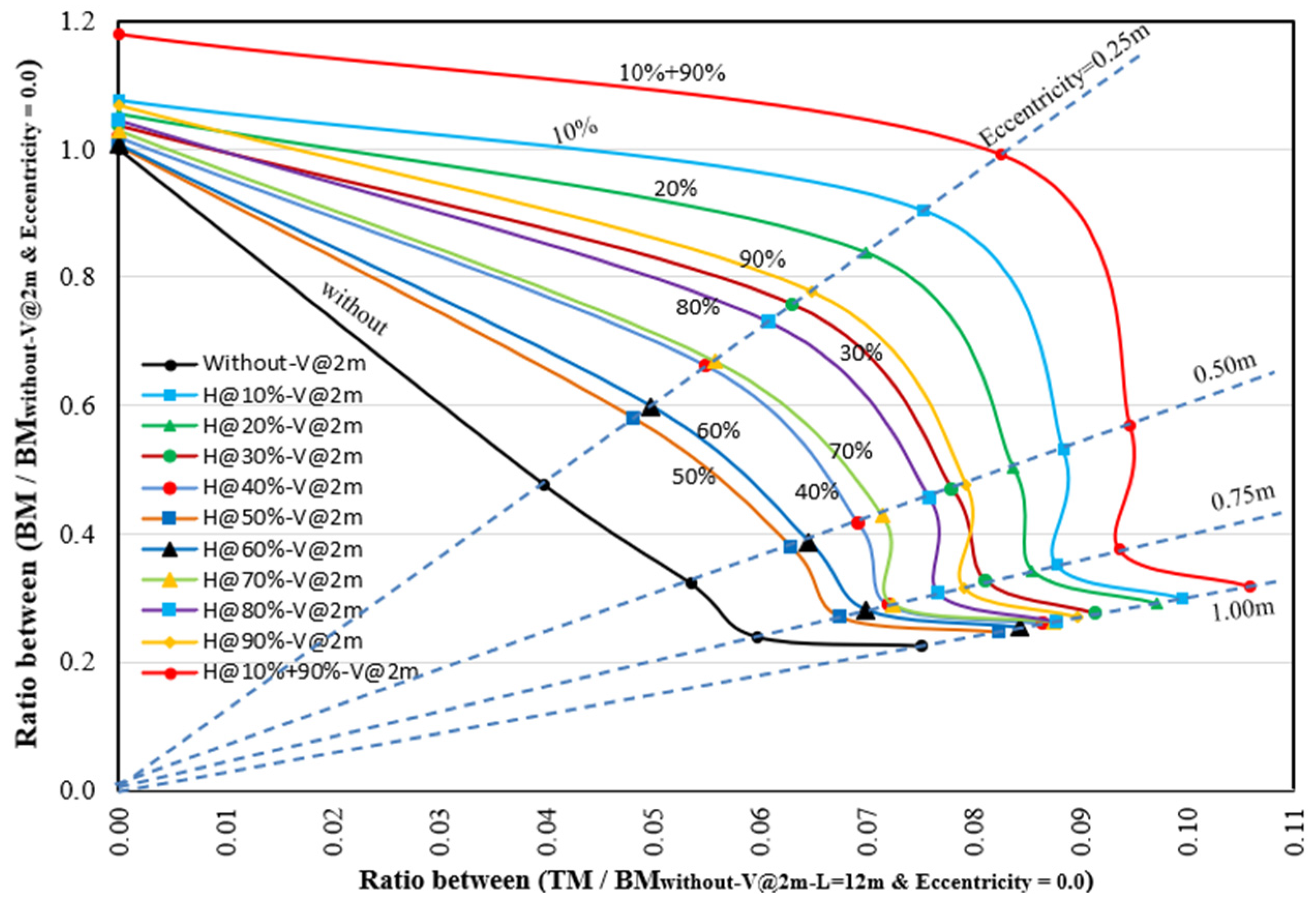

6. Predicting the Beam Capacity to Resist Combined Bending and Torsional Moments

7. Conclusions

- -

- The closer the horizontal stiffeners are to the flange, whether the upper, lower, or both, the better the efficiency and behavior of the steel beams in resisting eccentric loads.

- -

- Based on the ultimate load capacity of the steel beams for eccentric loads, the order of preference for the proposed locations of the horizontal stiffeners was as follows: 10%, 20%, 90%, 30%, 80%, 70%, 40%, and 50% of the beam’s web height.

- -

- Using horizontal stiffeners in the upper half of the web height (from 10% to 40%) contributes to improving the behavior and stresses distribution values in the upper flange edges. However, having them at a distance greater than or equal to 50% does not improve their effectiveness.

- -

- Using horizontal stiffeners in the lower half of the web height (from 60% to 90%) contributes to improving the behavior and stress distribution values in the edges of the lower flange. However, having them at less than or equal to 50% does not provide any improvement.

- -

- Using horizontal stiffeners with a small width at low ratios of web height provides efficiency in the behavior of beams and their resistance to eccentric loads, similar to using full-width stiffeners located at large ratios of web height. That is, the amount of material used in horizontal stiffeners can be reduced by choosing the appropriate location for the web height.

- -

- When horizontal stiffeners are used that combine two locations of web height, the percentage increase in capacity gives a greater improvement than the percentages for the two locations separately, but less than the sum of their values.

- -

- Using beams with only vertical stiffeners and reducing the distances between them by half improves their behavior in resisting combined bending and torsional moments, similar to using steel beams with horizontal stiffeners at 20% or 90% of the web height. In addition, there is a noticeable improvement in the behavior and distribution of stresses along both the upper and lower flange edges.

- -

- The proposed interaction diagram can predict the ultimate load capacity of combined bending and torsional moments resulting from eccentric loads using horizontal stiffeners at different locations along the web height.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, C.H.; Han, K.H.; Uang, C.M.; Kim, D.-K.; Park, C.-H.; Kim, J.-H. Flexural strength and rotation capacity of I-shaped beams fabricated from 800 MPa steel. J. Struct. Eng. 2013, 139, 1043–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.J.; Earls, C.J. Cross-sectional compactness and bracing requirements for HPS483W girders. J. Struct. Eng. 2003, 129, 1569–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Tong, G.; Zhang, L. Design of horizontal stiffeners for stiffened steel plate walls in compression. Thin-Walled Struct. 2018, 132, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dafafea, T.; Durif, S.; Bouchaïr, A.; Fournely, E. Experimental study of beams with stiffened large web openings. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2019, 154, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamoda, A.; Yehia, S.A.; Ahmed, M.; Sennah, K.; Abadel, A.A.; Shahin, R.I. Experimental and numerical investigation of shear strengthening of simply supported deep beams incorporating stainless steel plates. Buildings 2024, 14, 3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamary, A.S.; Mohamed, M.A.; Sharaky, I.A.; Mohamed, A.K.; Alharthi, Y.M.; Ali, M.A.M. Utilizing artificial intelligence approaches to determine the shear strength of steel beams with flat webs. Metals 2023, 13, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoomanesh, M.R.; Goudarzi, M.A. Experimental and numerical evaluation of shear load capacity for sinusoidal corrugated web girders. Thin-Walled Struct. 2020, 153, 106798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jáger, B.; Kövesdi, B.; Dunai, L. Numerical investigations on bending and shear buckling interaction of I-Girders with slender WEB. Thin-Walled Struct. 2019, 143, 106199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.S.; Sause, R.; Ricles, J.M. Strength and ductility of HPS flexural members. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2002, 58, 907–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earls, C.J. Uniform moment behavior of high performance steel I-shaped beams. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2001, 57, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Ma, S.; Chen, X.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Akbar, M.; Yang, N. Experimental investigation and design of novel hollow flange beams under bending. Buildings 2024, 14, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mahdy, G.M.; El-Saadaway, M.M. Ultimate strength of singly symmetric I-section steel beams with variable flange ratio. Thin-Walled Struct. 2015, 87, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, S.; Pedro, J.J.O.; Kuhlmann, U. Axial forces in transverse web stiffeners of steel plate girders—A numerical investigation. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 217, 113778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, J.J.O.; Biscaya, A.; Nascimento, S.; Kuhlmann, U. Buckling resistance of transversally stiffened steel plate girders considering M-V interaction with high compression forces. Structures 2024, 70, 107714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Zhou, Y.; Kong, H.; Yue, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, L. Dynamic monitoring of steel beam stress based on PMN-PT sensor. Buildings 2024, 14, 2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasery, M.M. Investigation on behaviours along weak axes of steel beam under low velocity impact loading: Experimental and numerical. Buildings 2023, 13, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narendra, P.V.R.; Singh, K.D. Elliptical hollow section steel cantilever beams under extremely low cycle fatigue flexural load—A finite element study. Thin-Walled Struct. 2017, 119, 126–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Kang, Y.-J.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, K. Experimental and analytical study of horizontally curved i-girders subjected to equal end moments. Metals 2021, 11, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.; Camotim, D. Lateral-torsional buckling of singly symmetric web-tapered beams: Theory and application. J. Eng. Mech. ASCE 2005, 131, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.; Camotim, D.; Dinis, P.B. Lateral-torsional buckling of singly symmetric web-tapered thin-walled I-beams: 1D model vs. shell FEA. Comput. Struct. 2007, 85, 1343–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascolo, I.; Modano, M.; Fiorillo, A.; Fulgione, M.; Pasquino, V.; Fraternali, F. Experimental and numerical study on the lateral-torsional buckling of steel c-beams with variable cross-section. Metals 2018, 8, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgarian, B.; Soltani, M.; Mohri, F. Lateral-torsional buckling of tapered thin-walled beams with arbitrary cross-sections. Thin-Walled Struct. 2013, 62, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kövesdi, B. Patch loading resistance of slender plate girders with longitudinal stiffeners. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2018, 140, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graciano, C.; Mendes, J. Elastic buckling of longitudinally stiffened patch loaded plate girders using factorial design. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2014, 100, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, R.; Mirambell, E.; Real, E. Transversally stiffened plate girders subjected to patch loading: Part 2. Additional numerical study and design proposal. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2013, 80, 492–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, G.B.; Gardner, L. Design recommendations for stainless steel I-sections under concentrated transverse loading. Eng. Struct. 2020, 204, 109810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graciano, C.; Johansson, B. Resistance of longitudinally stiffened I-girders subjected to concentrated loads. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2003, 59, 561–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Liu, S.; Wang, F. Temperature effect of composite girders with corrugated steel webs considering local longitudinal stiffness of webs. Buildings 2024, 14, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, F.; Abdul-Latif, A.; Yehia, A. Experimental study on the mechanical behavior of en08 steel at different temperatures and strain rates. Metals 2018, 8, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Feng, Q. Refined analysis of spatial three-curved steel box girder bridge and temperature stress prediction based on WOA-BPNN. Buildings 2024, 14, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, N.; Real, E.; Gardner, L. Shear design recommendations for stainless steel plate girders. Eng. Struct. 2014, 59, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabaharan, V.; Akhas, P.K. Evaluating the influence of stiffener in the bending capacity of cold formed steel C-section. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2025, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, N.; Mahendran, M. Section moment capacity tests of hollow flange steel plate girders. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2018, 148, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, B.; Ellobody, E.; He, J. Web crippling tests on cold-formed high strength steel channel sections having different stiffened flanges and stiffened web. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 190, 110995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, B.; Ellobody, E. Experimental investigation on cold-formed steel Z-sections having different stiffened flanges undergoing web crippling. Eng. Struct. 2023, 286, 116144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.; Yoo, C.H.; Yoon, D.Y. Behavior of intermediate transverse stiffeners attached on web panels. J. Struct. Eng. 2002, 128, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.; Lee, D.S.; Yoo, C.H. Design of intermediate transverse stiffeners for shear web panels. Eng. Struct. 2014, 75, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughlan, J.; Hussain, N. The in-plane shear failure of transversely stiffened thin plates. Thin-Walled Struct. 2014, 81, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, P.; Nascimento, S.; Pedro, J.J.O. Shear buckling resistance and intermediate transverse stiffeners internal forces of full-scale steel plate girders—Experimental tests and numerical investigation. Eng. Struct. 2024, 314, 118303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.D.; White, D.W. Transverse stiffener requirements to develop shear-buckling and postbuckling resistance of steel i-girders. J. Struct. Eng. 2013, 140, 04013098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graciano, C. Strength of longitudinally stiffened webs subjected to concentrated loading. J. Struct. Eng. 2005, 131, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinur, F.; Beg, D. Intermediate transverse stiffeners in plate girders. Steel Constr. 2012, 5, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudsari, M.T.; Abdollahi, F.; Salimi, H.; Azizi, S.; Khosravi, A.R. The effect of stiffener on behavior of reduced beam section connections in steel moment-resisting frames. Int. J. Steel Struct. 2015, 15, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Wang, L.; Shi, D. Flexural behaviour of strengthened damaged steel beams using carbon fibre-reinforced polymer sheets. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, A.M.; Ali, N.M.; Aljarbou, M.H.; Alzlfawi, A.; Aldhobaib, S.; Alanazi, H.; Altuwayjiri, A.H. Numerical study of the effect of out-of-plane distance in the lateral direction at the mid-span of a steel beam on the sectional moment capacity. Buildings 2025, 15, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfarazi, S.; Saffari, H.; Fakhraddini, A. Shear behavior of panel zone considering axial force for flanged cruciform columns. Civ. Eng. Infrastruct. J. 2020, 53, 359–377. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Gupta, P.K.; Iqbal, M.A. Experimental and numerical study on self-compacting alkali-activated slag concrete-filled steel tubes. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2024, 214, 108453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-B.; Li, G.-Q.; Chen, S.-W.; Sun, F.-F. Experimental and numerical study on the behavior of axially compressed high strength steel box-columns. Eng. Struct. 2014, 58, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabi, M.; Ferreira, F.P.V.; Abarkan, I.; Limbachiya, V.; Shamass, R. Prediction of the cross-sectional capacity of cold-formed CHS using numerical modelling and machine learning. Results Eng. 2023, 17, 100902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Chen, Y. Experimental study and finite element analysis of square stub columns with straight ribs of concrete-filled thin-walled steel tube. J. Build. Struct. 2006, 27, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C.L.; Khalid, Y.A.; Sahari, B.B.; Hamouda, A.M.S. Finite element analysis of corrugated web beams under bending. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2002, 58, 1391–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.B.; Mohamed, H.S.; Wang, L.; Wu, C.S. Experimental and numerical investigation on stiffened rectangular hollow flange beam. Int. J. Steel Struct. 2020, 20, 1564–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdal, F.; Tunca, O.; Tas, S.; Ozcelik, R. Experimental and finite element study of optimal designed steel corrugated web beams. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2021, 24, 1814–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Ma, S.; Chen, X.; Wu, Q.; Akbar, M. Finite element modeling of assembling rivet-fastened rectangular hollow flange beams in bending. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2023, 211, 108177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, S.; Sangle, K.K. Nonlinear static analysis of cold-formed steel frame with rigid connections. Results Eng. 2022, 15, 100503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kaseasbeh, Q. Analysis of hydrocarbon fire-exposed cold-formed steel columns. Results Eng. 2023, 20, 101400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzaman, A.; Lim, J.B.P.; Nash, D.; Rhodes, J.; Young, B. Cold-formed steel sections with web openings subjected to web crippling under two-flange loading conditions—Part I: Tests and finite element analysis. Thin-Walled Struct. 2012, 56, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isleem, H.F.; Chukka, N.D.K.R.; Bahrami, A.; Oyebisi, S.; Kumar, R.; Qiong, T. Nonlinear finite element and analytical modelling of reinforced concrete filled steel tube columns under axial compression loading. Results Eng. 2023, 19, 101341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Wang, Z.-B.; Yu, Q. Finite element modelling of concrete-filled steel stub columns under axial compression. J. Construct. Steel Res. 2013, 89, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, A.M. Numerical study of the effects of flange damage on the steel beam capacity under static and fatigue flexural loads. Results Eng. 2023, 17, 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, N.; Mahendran, M. Finite element analysis and design for section moment capacities of hollow flange steel plate girders. Thin-Walled Struct. 2019, 135, 356–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSYS. ANSYS Help User’s Manual, Version 22; Swanson Analysis Systems, Inc.: Technology Drive Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sayed, A.M.; Alanazi, H. Performance of steel metal prepared using different welding cooling methods. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e00953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Kang, S.-B.; Yang, B.; Wang, S.; Bai, J.; Nie, S.; Hu, Y.; Dai, G. Experimental and numerical studies on lateral torsional buckling of welded Q460GJ structural steel beams. Eng. Struct. 2016, 126, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, N.; Gardner, L. Experimental study of the shear response of lean duplex stainless steel plate girders. Eng. Struct. 2013, 46, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Dong, M.; Han, Q.; Elchalakani, M.; Xiong, G. Flexural behavior and rotation capacity of welded i-beams made from 690-mpa high-strength steel. J. Struct. Eng. 2021, 147, 04020320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokouhian, M.; Shi, Y.J. Flexural strength of hybrid steel I-beams based on slenderness. Eng. Struct. 2015, 93, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, D.; Hladnik, L. Slenderness limit of class 3 I cross-sections made of high strength steel. J. Constr. Steel Res. 1996, 38, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Xu, K.; Shi, G.; Li, Y. Local buckling behavior of high strength steel welded I-section flexural members under uniform moment. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2018, 21, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanien, M.; Bahaa, M.; Sobhy, H.; Hassan, A.; Inoue, J. Effect of vertical web stiffeners on lateral torsional buckling behavior of cantilever steel I-beams. J. Appl. Mech. 2004, 7, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Takabatake, H. Lateral buckling of I beams with web stiffeners and batten plates. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1988, 24, 1003–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Tong, G.; Zhang, L. Stiffness demand on stiffeners of vertically stiffened steel plate shear wall. J. Struct. Eng. 2020, 146, 06020005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.H.; Kang, Y.J.; Yoo, C.H. Stiffness requirements for transverse stiffeners of compression panels. Eng. Struct. 2007, 29, 2087–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stress (MPa) | 282 | 301 | 347 | 369 | 377 | 339 | 299 |

| Strain | 0.00134 | 0.0279 | 0.0825 | 0.1262 | 0.1795 | 0.1946 | 0.2057 |

| FE Model Based on | Beam Specimens | Steel Beam Dimensions | fyw (MPa) | fyf (MPa) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L (mm) | a (mm) | dw (mm) | tw (mm) | bf (mm) | tf (mm) | ||||

| Xiong et al. [64] | C1 | 5000 | 2500 | 249.26 | 9.01 | 180.17 | 10.48 | 541.0 | 525.0 |

| C2 | 6000 | 3000 | 247.74 | 9.00 | 179.19 | 10.49 | 541.0 | 525.0 | |

| C3 | 5000 | 2500 | 431.03 | 8.79 | 179.15 | 10.47 | 541.0 | 525.0 | |

| Saliba and Gardner [65] | I-600×200×12×10-1 | 1360 | 600 | 599.2 | 10.2 | 200.1 | 12.4 | 433.0 | 484.0 |

| I-600×200×12×8-2 | 2560 | 1200 | 600.0 | 8.4 | 199.8 | 12.3 | 431.0 | 484.0 | |

| I-600×200×12×10-2 | 2560 | 1200 | 600.1 | 10.6 | 200.4 | 12.6 | 433.0 | 484.0 | |

| I-600×200×12×15-2 | 2560 | 1200 | 599.0 | 15.0 | 200.1 | 15.3 | 564.0 | 484.0 | |

| Yang et al. [66] | Y1-3 | 3500 | 1500 | 373.26 | 9.57 | 178.98 | 13.59 | 781.0 | 769.0 |

| Y2-3 | 3500 | 1500 | 372.44 | 9.63 | 197.47 | 13.63 | 781.0 | 769.0 | |

| Y6-3 | 3500 | 1500 | 323.94 | 9.65 | 201.46 | 13.50 | 781.0 | 769.0 | |

| Y8-3 | 3500 | 1500 | 319.15 | 9.64 | 159.95 | 16.10 | 781.0 | 754.0 | |

| Y9-3 | 3500 | 1500 | 370.11 | 9.90 | 159.15 | 16.26 | 781.0 | 754.0 | |

| Y10-3 | 3500 | 1500 | 369.95 | 9.81 | 177.81 | 16.03 | 781.0 | 754.0 | |

| Y12-4 | 4000 | 1200 | 320.19 | 9.50 | 177.40 | 16.38 | 781.0 | 754.0 | |

| Y13-4 | 4000 | 1200 | 368.8 | 9.68 | 159.34 | 16.35 | 781.0 | 754.0 | |

| Y14-4 | 4000 | 1200 | 368.32 | 9.51 | 182.36 | 16.11 | 781.0 | 754.0 | |

| Shokouhian and Shi [67] | C1 | 3399 | 1000 | 357.4 | 7.87 | 169.0 | 11.91 | 442.8 | 408.2 |

| C2 | 3401 | 1000 | 358.48 | 7.82 | 263.6 | 11.85 | 442.8 | 408.2 | |

| Beg and Hladnik [68] | B1 | 5000 | 1800 | 222.70 | 10.40 | 271.00 | 12.40 | 775 | 797.0 |

| C1 | 5000 | 1800 | 221.30 | 10.40 | 251.00 | 12.60 | 775 | 776.0 | |

| D1 | 5000 | 1800 | 220.90 | 10.40 | 220.80 | 12.40 | 830 | 873.0 | |

| E1 | 5000 | 1800 | 220.70 | 10.40 | 198.80 | 12.60 | 830 | 797.0 | |

| Shi et al. [69] | I-460-1 | 3400 | 1000 | 520.9 | 11.96 | 167.8 | 13.87 | 510.5 | 557.0 |

| I-460-2 | 3400 | 1000 | 610.8 | 12.08 | 260.1 | 13.94 | 510.5 | 557.0 | |

| I-890-3 | 2000 | 600 | 661.0 | 6.17 | 166.5 | 6.35 | 886.0 | 886.0 | |

| Beam Specimens | Horizontal Stiffeners | Vertical Stiffeners at Distance, (mm) | Cases of Eccentricity Distance, (mm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Width bhs (mm) | Location dhs (mm) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Without-V@2m | - | - | 2000 | 0.00 | 250 | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| H@10%-V@2m | 195 | 10% = 150 | 2000 | 0.00 | 250 | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| H@20%-V@2m | 195 | 20% = 300 | 2000 | 0.00 | 250 | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| H@30%-V@2m | 195 | 30% = 450 | 2000 | 0.00 | 250 | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| H@40%-V@2m | 195 | 40% = 600 | 2000 | 0.00 | 250 | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| H@50%-V@2m | 195 | 50% = 750 | 2000 | 0.00 | 250 | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| H@60%-V@2m | 195 | 60% = 900 | 2000 | 0.00 | 250 | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| H@70%-V@2m | 195 | 70% = 1050 | 2000 | 0.00 | 250 | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| H@80%-V@2m | 195 | 80% = 1200 | 2000 | 0.00 | 250 | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| H@90%-V@2m | 195 | 90% = 1350 | 2000 | 0.00 | 250 | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| H@10%+90%-V@2m | 195 | 10% = 150 and 90% = 1350 | 2000 | 0.00 | 250 | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| H@20%-b=16cm-V@2m | 160 | 20% = 300 | 2000 | 0.00 | 250 | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| H@20%-b=12cm-V@2m | 120 | 20% = 300 | 2000 | 0.00 | 250 | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| Without-V@1m | - | - | 1000 | 0.00 | 250 | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

| FE Model Based on | Beam Specimens | Mu.Exp (kN.m) | FEM Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mu.FEM (kN.m) | Mu.FEM /Mu.Exp | |||

| Xiong et al. [64] | C1 | 335.30 | 344.88 | 1.029 |

| C2 | 326.39 | 324.12 | 0.993 | |

| C5 | 634.68 | 631.40 | 0.995 | |

| Saliba and Gardner [65] | I-600×200×12×10-1 | 1102.80 | 1126.05 | 1.021 |

| I-600×200×12×8-2 | 1172.00 | 1184.33 | 1.011 | |

| I-600×200×12×10-2 | 1395.00 | 1380.12 | 0.989 | |

| I-600×200×12×15-2 | 2162.00 | 2139.76 | 0.990 | |

| Yang et al. [66] | Y1-3 | 1012.23 | 1037.91 | 1.025 |

| Y2-3 | 1117.22 | 1149.06 | 1.028 | |

| Y6-3 | 962.23 | 957.55 | 0.995 | |

| Y8-3 | 955.01 | 964.44 | 1.010 | |

| Y9-3 | 1158.33 | 1191.08 | 1.028 | |

| Y10-3 | 1230.55 | 1251.79 | 1.017 | |

| Y12-4 | 1065.00 | 1034.81 | 0.972 | |

| Y13-4 | 1184.36 | 1179.61 | 0.996 | |

| Y14-4 | 1274.40 | 1290.05 | 1.012 | |

| Shokouhian and Shi [67] | C1 | 447.91 | 455.66 | 1.017 |

| C2 | 616.70 | 613.08 | 0.994 | |

| Beg and Hladnik [68] | B1 | 703.80 | 724.61 | 1.030 |

| C1 | 646.20 | 640.70 | 0.991 | |

| D1 | 644.40 | 638.66 | 0.991 | |

| E1 | 559.80 | 567.00 | 1.013 | |

| Shi et al. [69] | I-460-1 | 1225.40 | 1220.71 | 0.996 |

| I-460-2 | 1999.70 | 2029.06 | 1.015 | |

| I-890-3 | 797.10 | 804.00 | 1.009 | |

| Beam Specimens | The Case Study of the Eccentricity Measured from the Center Line of the Beam | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eccentricity = 0.00 | Eccentricity = 0.25 m | Eccentricity = 0.50 m | Eccentricity = 0.75 m | Eccentricity = 1.00 m | ||||||

| Pu (kN) | Pu/Pu.wo | Pu (kN) | Pu/Pu.wo | Pu (kN) | Pu/Pu.wo | Pu (kN) | Pu/Pu.wo | Pu (kN) | Pu/Pu.wo | |

| Without-V@2m | 3480.75 | 1.00 | 1662.08 | 1.00 | 1120.68 | 1.00 | 832.88 | 1.00 | 785.42 | 1.00 |

| H@10%-V@2m | 3748.50 | 1.08 | 3148.50 | 1.89 | 1847.11 | 1.65 | 1221.96 | 1.47 | 1040.02 | 1.32 |

| H@20%-V@2m | 3672.00 | 1.05 | 2919.55 | 1.76 | 1748.76 | 1.56 | 1190.80 | 1.43 | 1014.43 | 1.29 |

| H@30%-V@2m | 3604.30 | 1.04 | 2634.22 | 1.58 | 1629.88 | 1.45 | 1130.08 | 1.36 | 955.00 | 1.22 |

| H@40%-V@2m | 3542.50 | 1.02 | 2300.91 | 1.38 | 1447.01 | 1.29 | 1003.95 | 1.21 | 904.27 | 1.15 |

| H@50%-V@2m | 3495.02 | 1.00 | 2017.00 | 1.21 | 1316.40 | 1.17 | 940.88 | 1.13 | 860.37 | 1.10 |

| H@60%-V@2m | 3510.33 | 1.01 | 2083.44 | 1.25 | 1349.04 | 1.20 | 974.64 | 1.17 | 880.71 | 1.12 |

| H@70%-V@2m | 3579.00 | 1.03 | 2328.99 | 1.40 | 1492.32 | 1.33 | 1008.45 | 1.21 | 913.93 | 1.16 |

| H@80%-V@2m | 3630.61 | 1.04 | 2541.05 | 1.53 | 1584.98 | 1.41 | 1068.55 | 1.28 | 917.08 | 1.17 |

| H@90%-V@2m | 3715.02 | 1.07 | 2706.82 | 1.63 | 1657.00 | 1.48 | 1100.89 | 1.32 | 937.52 | 1.19 |

| H@10%+90%-V@2m | 4102.20 | 1.18 | 3449.33 | 2.08 | 1977.65 | 1.76 | 1304.08 | 1.57 | 1106.17 | 1.41 |

| H@20%-b=16cm-V@2m | 3637.80 | 1.05 | 2789.26 | 1.68 | 1660.56 | 1.48 | 1128.63 | 1.36 | 987.45 | 1.26 |

| H@20%-b=12cm-V@2m | 3560.40 | 1.02 | 2582.74 | 1.55 | 1547.63 | 1.38 | 1071.91 | 1.29 | 921.94 | 1.17 |

| Without-V@1m | 3766.00 | 1.08 | 2855.20 | 1.72 | 1781.10 | 1.59 | 1196.50 | 1.44 | 1001.88 | 1.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aljarbou, M.H.; Sayed, A.M. Effect of Horizontal Stiffeners on the Efficiency of Steel Beams in Resisting Bending and Torsional Moments: Finite Element Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 4385. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234385

Aljarbou MH, Sayed AM. Effect of Horizontal Stiffeners on the Efficiency of Steel Beams in Resisting Bending and Torsional Moments: Finite Element Analysis. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4385. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234385

Chicago/Turabian StyleAljarbou, Mishal H., and Ahmed M. Sayed. 2025. "Effect of Horizontal Stiffeners on the Efficiency of Steel Beams in Resisting Bending and Torsional Moments: Finite Element Analysis" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4385. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234385

APA StyleAljarbou, M. H., & Sayed, A. M. (2025). Effect of Horizontal Stiffeners on the Efficiency of Steel Beams in Resisting Bending and Torsional Moments: Finite Element Analysis. Buildings, 15(23), 4385. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234385