Abstract

The non-fixed location and intermittent emission of pollution sources are posing significant challenges for industrial ventilation and dust removal. Owing to its energy-saving and emission-reduction advantages, recirculating ventilation has emerged as a critical solution in industrial ventilation. However, the introduction of recirculated air leads to the accumulation of both pollutants and temperature in controlled environments. However, the accumulation situation and control methods within the recirculation air system are still not fully understood, especially for discrete pollution sources. Theoretical models were developed in this paper to quantitatively calculate these issues. Then, the spatiotemporal distributions of air temperature and pollutant concentrations were investigated within the controlled environment by numerical simulation. The result shows that upper limits exist for both pollutant and heat accumulation. Controlling the recirculation air ratio between 0% and 60% resulted in a corresponding increase in pollutant concentration ranging up to 28.58% and a temperature rise of up to 6.16%. At a 27.8% recirculation ratio, fresh air consumption decreased by 27.8%, mean pollutant concentration increased by 5.50%, and mean air temperature rose by 3.78%. In addition, the dynamic characteristics of pollutant concentration and temperature variation at different circulating air ratios were analyzed. The recirculating air system effectively conserves energy and reduces emissions. The quantitative calculation models can facilitate the adoption and promotion of such systems, thereby contributing to industrial green development.

1. Introduction

In 2021, China implemented the Foundry Industry Air Pollutant Emission Standard (GB 39726-2020), which imposes stricter emission controls compared to previous industrial standards. For instance, the particulate matter (PM) emission limit for melting furnaces was significantly reduced from 150 mg/m3 [1] to 40 mg/m3 [2]. Consequently, the manufacturing sector faces mounting challenges stemming from increasingly stringent emission regulations and the growing demands of sustainable production practices [3,4]. Additionally, some foundry operations involve intermittent emission and high-temperature heat sources. Currently, general dilution ventilation [5] and local exhaust hoods [6] remain the primary methods for improving indoor air quality in industrial buildings. While local exhaust systems have been extensively studied and optimized for pollutant capture [7,8,9], they exhibit limited pollutant capture efficiency due to fugitive emissions. Traditional ventilation approaches often fail to fully mitigate dust dispersion and entail high economic and energy costs.

Litomisky [10] pointed out that most industrial emission processes are intermittent (usually less than 50% of the time) and proposed an on-demand centralized ventilation system to reduce exhaust air volume. But currently, there is little research on intermittent pollution sources. Leszczynski and Grybos [11], aware of the complexity and overscale of industrial pneumatic systems, proposed a framework for optimizing system energy efficiency through the accumulation and reuse of exhaust gases. The circulating ventilation system recycles part of the exhaust air transport capacity, reducing real-time emissions of pollutants. Therefore, the initial investment in the dust removal system is reduced, and the energy consumption of fans and fresh air is reduced. Santarpi, L. et al. studied the flux reduction, gas and particulate pollutant control, and human exposure time generated by air curtain ventilation systems through theoretical and CFD analysis [12]. Stathopoulou OI used PHOENICS to simulate the airflow vortex, temperature stratification, and dynamic migration of pollutants in a large sports arena, verifying the consistency between the model and experimental data [13]. By implementing controlled circulating ventilation technology on-site, Pan Yang [14] greatly reduced the dust concentration of the mining roadway, especially the roadway with a relatively large concentration of workers within 30 m of the working face. They confirmed the effectiveness of the circulating air system. Taking a foundry cleaning workshop as the research object, Chenchao Lan et al. [15] found that the energy consumption of the non-circulating ventilation system was 8 times that of the circulating ventilation system by CFD numerical calculation. These studies demonstrated the potential of circulating ventilation technology to improve indoor air quality and reduce ventilation energy consumption in industrial buildings but did not address the issues of pollutant and temperature accumulation in controlled environments. Liu G. et al. [16] proposed a new method for calculating the dynamic exhaust demand of multi-terminal exhaust ventilation systems and discussed the influence of factors such as exhaust time, cycle time, number of machines, number of workers, and operation time on the process. However, only the characteristics of the process and exhaust cycle time are discussed, and the characteristics of the circulating ventilation system and control methods are not mentioned. Baiquan Ding et al. [17] studied the influence of different parameters such as air supply speed and angle on the dust removal effect and proposed the optimal scheme through CFD simulation. He only focuses on the effect of airflow organization on the circulating ventilation system and does not involve the study of precise control of the circulating air rate. Lingjie Zeng et al. [18] proposed a new type of circulating ventilation system based on the characteristics of pollutant discharge in the rubber mixing process. They optimized the circulating air volume, recirculating air jet angle, and exhaust air volume of the circulating ventilation system to improve the pollutant capture efficiency of the circulating system. However, the applicability of the research to other processes needs to be verified, and there is no quantitative evaluation of the accumulation of pollutants and heat in the circulating air system, as well as the circulating air ratio.

The high-temperature pollution source of the casting workshop is mainly the hot metal ladle and its associated dust [19]. The pollution source in the foundry workshop is usually still high temperature. The air on the surface of the hot metal is heated, forming a high-temperature hot plume, carrying pollutants in an upward movement, and constantly enrolling the surrounding air, aggravating the air pollution of the casting workshop. Xi Zhang et al. [20] simulated the plume temperature field and velocity field of the upper receiving hood of the high-temperature heat source. They proposed reasonable measures to set the location and air volume of the exhaust hood from the two perspectives of waste heat removal and dust control, not involving circulating air. Yi Wang et al. [21] determined the distribution characteristics of heat and pollutants in space under the interference of the floating jet. They found the key factors for the control of high-temperature dust and proposed the optimal design approach and carried out engineering verification. Yang Y. et al. [22] used numerical analysis to study the variation law of the flow field of the floating jet under the spatially confined condition. Their research on high-temperature particles was mainly related to jets and gave the law of the influence of the baffle on the trapping efficiency under the suction effect of the exhaust hood. Aiming at the problem that the size of the exhaust hood cannot be too large due to limitations such as process flow, Chao Chen [23] proposed an optimization scheme of a local ventilation system combined with the jet pilot. He analyzed the influence of jet pilots with different characteristics on the flow field. Yibo Shu [24] analyzed the influencing factors of the floating jet axial velocity and section flow. He studied the velocity field rule of the floating jet under the action of the side suction hood and the variation rule of trapping air speed at different trapping efficiencies. He mainly conducted research on the organization of airflow inside the hood. Ping He [19] conducted theoretical research of high-temperature heat sources in the workshop and studied the flow field properties of high-temperature hot plumes. He simulated the effect of the Aaberg exhaust hood on plume and dust control, so as to provide a reference for the optimization of such exhaust hoods. None of the above scholars involved quantitative calculation of high-temperature pollutants. Baoning Guo et al. [25] proposed the solution method for the thermal process by numerical simulation. However, the problem of thermal accumulation of pollutants from high-temperature heat sources has not been mentioned and there is also no quantitative calculation of the accumulation effect.

The use of the circulating ventilation system may result in the pollutant and thermal accumulation in a controlled environment over time, which restricts the safe operation and extended application of the circulating ventilation system. Yajing Zhang et al. [26] noted that the accumulation of pollutants may be caused by the circulating ventilation system, which has a negative impact on the long-term operation of the system and the dust removal effect. However, this study did not propose a specific calculation method for the accumulated concentration of pollutants in the circulating ventilation system. Jifa Zhang et al. [27] paid attention to the adjustment of the circulating air rate in the process of optimizing the circulating ventilation system at different ratios of circulating air volume through CFD simulations to ensure that the system was operating at its best. Despite the determination of an optimum rate, no established method for its calculation was given. Chenchao Lan [15] proposed a new circulating ventilation system and studied the air flow characteristics of the casting shop under the coupling of circulating air and high-temperature heat source to determine the particle trajectory and particle diffusion distribution under different conditions. However, the temperature increase remains unquantified, and the control method for circulating air has not been clarified.

In summary, most studies on the existing circulation control system focus on improving the dust removal efficiency of the existing circulation air. However, pollutant accumulation and thermal buildup persist in the controlled environment of circulating air systems, with insufficient research on their quantitative control methods. In this paper, we (i) develop a theoretical model to quantify pollutant accumulation and thermal accumulation; (ii) derive a control method of the proportion of circulating air; (iii) validate using CFD; (iv) analyze spatiotemporal distribution of pollutants and temperature. It is expected to provide a basis for the design and calculation of the circulating ventilation system.

2. Theoretical Calculation Model

2.1. Pollutant Accumulation

The theoretical derivation adopts the principle of pollutant mass balance and assumes that there is no deposition, resuspension, or chemical transformation of particulate matter inside the controlled environment. The pollutant concentration is assumed to be uniformly distributed in the controlled environment due to the assumption of instantaneous and complete mixing between the supply airflow and the indoor air. In connection with the actual application of circulating air, the intermittent nature of pollutant release is considered, and the emission percentage k is introduced; the unevenness of pollutant emanation is considered, and since the pollutant concentration in the exhaust air and the average concentration of pollutants in the controlled environment are not equal, it is assumed that the pollutant concentration at the arrival of the exhaust air is n times the average indoor concentration and the value of pollutant concentration inhomogeneity coefficient n is supplemented. n is determined by the controlled environment’s geometry size, exhaust hood characteristics, and the organization of the airflow.

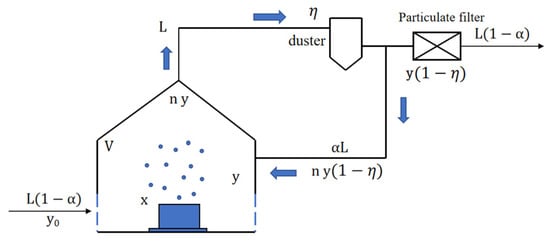

The schematic diagram of the circulating ventilation system for the calculation of pollutant concentration in the controlled environment is shown in Figure 1, where L is the air volume of the local exhaust hood, m3/s; α is the proportion of circulating air; y0 is the concentration of pollutant outside the controlled environment, mg/m3; τ is the time, s, for the operation of the circulating ventilation system; x is the source intensity of the pollutant source, mg/s; k is the emission proportion, i.e., the proportion coefficient of the pollutant source’s intermittent emission time to the total time, and the total time is the total time of emission and non-emission time; n is the unevenness coefficient of pollutant concentration, i.e., the proportion coefficient of pollutant concentration at the exhaust air outlet to the average concentration of the controlled environment body; y is the pollutant concentration in the controlled environment, mg/m3; η is the dust-removing efficiency of the dust collector, which is obtained by the manufacturer of the dust collector purchased and used in the plant; V is the volume of the controlled environment space, m3; L (1 − α) is the volume of air make-up of the controlled environment, m3/s; and αL is the circulating air volume, m3/s. The blue arrow in the figure represents the direction of air flow.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of a recirculating ventilation system with an open exhaust hood for calculating pollutant concentration in a controlled environment.

The current circulating ventilation system lacks a quantitative calculation method for circulating air volume. Based on the principle of pollutant mass conservation within the controlled environment and neglecting air density differences, this study establishes a calculation formula for pollutant accumulation in the circulating ventilation system, incorporating the local exhaust hood as presented below.

- (a)

- Differential Equations for mass conservation of controlled environmental pollutants:

- (b)

- The mass conservation equation is based on the concentration of pollutants outside the controlled environment and the concentration of pollutants in the controlled environment at the initial moment to solve the real-time calculation model of pollutants over time.

Assuming that the concentration of pollutants outside the controlled environment is 0 mg/m3 and the concentration of pollutants in the controlled environment at the initial moment is 0 mg/m3, the solution is obtained as follows:

- (c)

- Calculate the upper concentration limit for the accumulation of the controlled environmental pollutant when the time tends to infinity.

That is, the upper limit of pollutant concentration in the controlled environment is governed by the source strength, local exhaust hood’s airflow rate, circulating air proportion, filtration efficiency of the dust collector for the pollutant, emission proportion k, and the unevenness coefficient of pollutant concentration n.

2.2. Calculation of Circulating Air Proportion

The emission intensity of pollutants varies by process, as do the controlled environmental concentration limits. Accordingly, the proportion of recirculated air should also be adjusted based on the specific process. Casting contains processes such as crushing, melting, molding and core making, casting, and sand dropping. The concentration of particulate matter produced by each typical process can be affected by a variety of factors, including but not limited to the casting process, metal type, fuel type, furnace temperature, combustion efficiency, etc. Therefore, the circulating air proportion should be calculated based on the specific process and source emission characteristics.

When the release time from the source is long enough to calculate real-time pollutant concentration values in the controlled environment and the pollutant concentration reaches the upper accumulation limit,

Given the known conditions—such as the exhaust air volume (L) of the local exhaust hood, the pollutant source strength (x), the dust collector’s removal efficiency (η), the non-uniformity coefficient of pollutant concentration (n), and the upper limit of the maximum accumulation concentration ()—the proportion of recirculated air () can be calculated using this formula:

For example, the pollution source during the melting process continuously releases about 120 mg of particulate matter per second. That is, a source strength () of 120 mg/s and an emission proportion () of 1. Combined with the requirements of the workshop pollutant concentration exposure limits and the relevant provisions of the national occupational health standards, in the casting process, the average exposure concentration () of dust in the air within a day is allowed to be 8 mg/m3. n is the proportionality coefficient of the exhaust air outlet pollutant concentration to the average concentration of the controlled environment. In the actual calculations, at the casting workshop site, pollutant concentrations at the exhaust vent and multiple indoor measurement points were measured at equal time intervals to obtain average values. It is assumed that the concentration of particles at the site exhaust vents is 3 times the average concentration of the whole workshop, the efficiency () of the dust collector is 80%, and the air volume of the local exhaust hood () is 6 m3/s.

By substituting calculation formula (3) for the upper limit of pollutant concentration and the continuous emission condition, the proportion of circulating air can be solved as follows:

The solution α is 83.33%, meaning the recirculated air ratio must be maintained at or below 83.33% to ensure particulate matter concentrations remain within exposure limits. In practical applications of recirculating ventilation systems for industrial facilities with existing pollution sources, this methodology can be applied across different processes. This enables precise control of the recirculated air ratio to meet specific environmental requirements at the worksite, thereby establishing an appropriate regulatory range for the recirculated air proportion.

2.3. Calculation of Thermal Accumulation

Due to the complex layout of equipment in the workshop, the volume of the mobile exhaust hood is limited. So, it is assumed that the controlled environment in the hood has uniform air temperature distribution; air supply mixes with indoor air instantaneously; and air density changes are negligible. Since the air temperature in the exhaust differs from the average air temperature in the controlled environment, we assume the exhaust air temperature is n times the average indoor air temperature. For local ventilation applications involving circulating air, the intermittent nature of pollutant release is considered through emission percentage α and the non-uniformity of indoor temperature distribution is accounted for by coefficient n. The value of n depends on the geometrical shape and dimensions of the controlled environment, the characteristics of local exhaust hoods, and the organization of airflow.

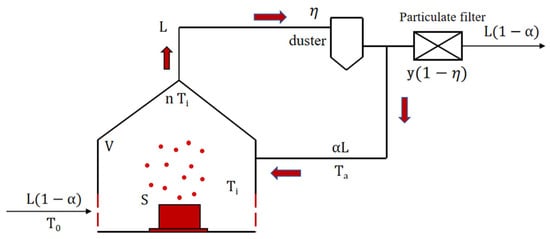

The schematic diagram of the circulating ventilation system for controlled environment air temperature calculation is shown in Figure 2, where L is the air volume of local exhaust hood, m3/s; α is the proportion of circulating air; To is the temperature outside the controlled environment, K; t is the time, s; S is the intensity of the heat source, W; is the emission proportion (the ratio of the intermittent emission time of the pollution source to the total time, which includes both emission and non-emission periods); Ta is the return air temperature of the circulating ventilation system, K; Ti is the temperature within the controlled environment, K; n is the unevenness coefficient of air temperature (the ratio of the temperature at the exhaust outlet to the average temperature of the controlled environment); and V is the volume of the controlled environment space, m3. The red arrow in Figure 1 represents the direction of high-temperature air flow.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the circulating ventilation system for air temperature calculation.

- (a)

- The energy conservation equation for the controlled environment based on energy conservation (assuming little change in air density) is

- (b) Based on the controlled environment energy conservation differential equation, the controlled environment air temperature calculation model can be developed as

- (c) When time approaches infinity, the temperature limit for controlled environment thermal accumulation can be derived from Equation (8). For cases where n + α > 1, the source air real-time temperature calculation model exhibits a lower thermal accumulation limit; when n + α < 1, the model demonstrates an upper thermal accumulation limit. Alternatively, for a more formal academic style, the asymptotic temperature limit of controlled environment thermal accumulation (as t → ∞) is obtained from Equation (8). Two distinct cases emerge: when n + α > 1, the source air real-time temperature model converges to a lower bound of thermal accumulation; when n + α < 1, the model approaches an upper bound of thermal accumulation.

That is, the temperature limit within the controlled environment is fundamentally governed by seven key parameters: the ambient external temperature To, heat source intensity S, local exhaust hood airflow rate L, recirculation air ratio, return air temperature of the ventilation system Ta, emission factor k, and air temperature non-uniformity coefficient n.

Equations (4), (5) and (9) can be used to obtain the accumulation upper limits of pollutant concentration and air temperature, as well as the proportion of circulating air in the design of the circulating air system.

3. Numerical Simulation

3.1. Physical Model

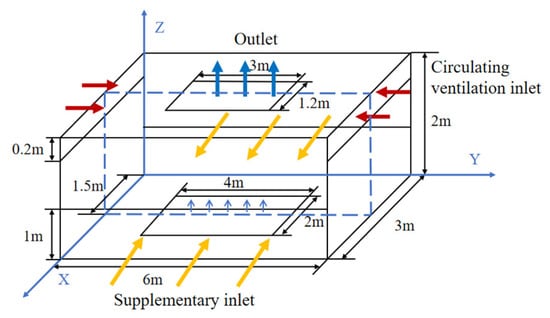

In this study, the real-scale physical model established in the numerical simulation of the controlled environment with a circulating ventilation system is shown in Figure 3. This geometric model is derived from a semi-enclosed exhaust hood at the pollution source of an industrial workshop. With reference to a foundry site’s pollution sources and the size of the capture hood, the calculation domain size for the hood model is length (X) × width (Y) × height (Z) = 6 × 3 × 2 m3.

Figure 3.

Physical model of the exhaust hood.

A rectangular exhaust port is located in the middle of the hood’s upper side, with an area of 3 × 1.2 = 3.6 m2. The exhaust air volume is 3 m3/s, corresponding to an exhaust air velocity of 0.833 m/s.

To improve the capture efficiency of the hood when using the circulating ventilation system, air supply is designed on both sides to create synergistic airflow. This design features two return air outlets, one on each side. Each return air outlet has an area of 0.2 × 3 = 0.6 m2, resulting in a total air supply area of 1.2 m2. With an air supply velocity of 1 m/s, the total circulating air proportion is 40%. Additionally, two natural make-up air outlets are located in the lower part of the hood, each measuring 1 m × 6 m. Particles are released from a rectangular outlet with dimensions of 4 m × 2 m (8 m2 area). The density of the particles is 1550 kg/m3, specific thermal capacity CP is 1680 J/(kg·K), and thermal conductivity λ is 0.33 W/(m·K). The mass flow rate of the particles was set for the study in two cases, 5 mg/s and 35 mg/s, and the release velocity was 0.005 m/s.

In this study, ICEM was employed for physical model construction using hexahedral structured meshing. To assess the influence of mesh quality on simulation results, velocity values were compared at three monitoring points—X1 (1.5,3,0.8), X2 (1.5,3,1), and X3 (1.5,3,1.5)—located along a test line directed toward the pollutant emission center. The comparison was conducted across five mesh densities: 302,621; 493,200; 852,040; 1,324,431; and 2,347,462 elements. The analysis revealed that at 852,040 elements, the velocity values at point X showed minimal variation (within 5%) when compared to the results obtained with 1,324,431 and 2,347,462 elements. Consequently, the 852,040-element mesh was selected for subsequent analyses and the selected mesh configuration maintained quality scores above 0.95.

3.2. Numerical Model and Boundary Conditions

Boundary conditions for the controlled environment were established according to emission characteristics. The ambient temperature was 300 K. The temperature of the pollution source was 673 K and the mass flow rate of released particles from the resource surface was 5 mg/s. The circulating air speed was 0–0.18 m/s, calculated based on the proportion of circulating air and the opening size. The outlet velocity of the exhaust hood was 0.18 m/s. The supplementary inlet boundary condition was set as the pressure inlet and other boundaries were set as the no-slip wall. Particles escape at the inlets, are trapped at the exhaust hood vent, and reflect at the wall surfaces.

For the simulation of fluid flow indoors, the commonly used mathematical models include the standard k-ε model and RNG k-ε turbulence model [28]. L. Ben Ramoul [29] compared the numerical calculation results of three RANS turbulence models (Standard k-ε model, Realizable k-ε model, and RNG k-ε model) with wind tunnel experiments and proved that the RNG k-ε turbulence model had the best performance. Therefore, the RNG k-ε model was used in this study, and the interphase-coupled random walk model was employed to predict the particle diffusion behavior caused by fluid turbulence [30]. Through calculation, the ratio of particle volume under any working condition was less than 10−6. According to the classification of two-phase flow, the simulated fluid was regarded as a sparse two-phase flow, and the interaction between particles was ignored [31]. Additionally, considering the transfer of momentum and heat between particles and air flow, the bidirectional coupling method was selected to solve the momentum and thermal exchange between the discrete phase and continuous phase at each time step [32].

The coupled algorithm was adopted for the pressure–velocity coupling with the time step set to 0.1 s. Given that air density, specific heat capacity, thermal conductivity, and viscosity are dependent on temperature, a linear differential method was employed to account for their variations. A UDF (user define function) was used to implement coarse filtering and redirect the air to the controlled environment. This approach reduced numerical simulation complexity by eliminating the need to simulate particulate filtration processes in the filter.

3.3. Validation of Particle Transport Model

To validate the particle transport model used in this study, numerical simulations were performed under the experimental conditions described by Chen [33], with results compared against experimental data. The test line was positioned at y = 0.2 m on the xz section in the middle of the room, specifically at x = 0.2 m, x = 0.4 m, and x = 0.6 m. The comparison between simulated and experimental velocity values along the x-coordinate axis at different positions is presented in Figure 4. The simulation results show good agreement with experimental measurements, demonstrating an average error of 13.7%. Particle concentrations were normalized using the inlet concentration as reference. The comparison of dimensionless particle concentrations (c*) between simulations and experiments is also shown in Figure 4. The simulation results near the top wall and the height of the inlet have a relatively large error with the experimental measurements, and the horizontal jet velocity is large near the inlet at the top and the gradient of the particle concentration is large and the spatial variation is significant compared with the other places of the model room. The calculation error has been reduced by 30% compared to the error in the original literature.

Figure 4.

Comparison of experimental and simulated results: velocity values and dimensionless concentration c* at positions x = 0.2 m, 0.4 m, and 0.6 m on the surface of y = 0.2 m.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Comparison of Theoretical Calculations and Simulated Results

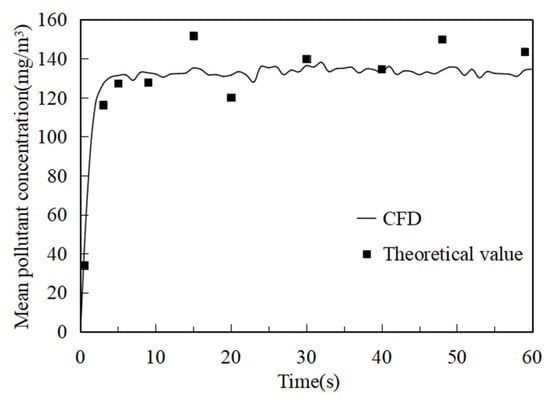

4.1.1. Pollutant Concentration Accumulation

In numerical simulation, the average pollutant concentration in the environment controlled by the circulating ventilation system shown in Figure 1 is calculated with circulating air ratio α = 27.8%. The theoretical value of the mean pollutant concentration was calculated by substituting α = 27.8% into Equation (2). The comparison between numerical simulation and theoretical calculation results is shown in Figure 5. It can be seen from the figure that as the release time of particulate matter increases, the mean pollutant concentration in the controlled environment gradually increases and ultimately plateaus. In other words, there is a defined ceiling for pollutant accumulation. Specifically, within four seconds of particle release, the mean pollutant concentration in the controlled environment attains a relatively stable level of 130.44 mg/m3. The average error between the simulation and the theoretical values at different times is less than 15%. Therefore, the numerical simulation results agree well with the theoretical calculation results of pollutant accumulation.

Figure 5.

Comparison of simulated and theoretical particulate concentrations at α = 27.8%.

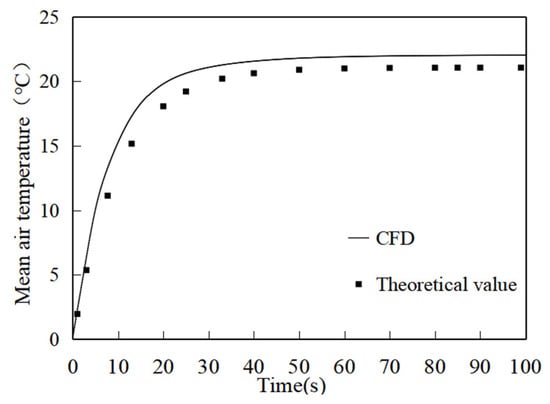

4.1.2. Thermal Accumulation

In numerical simulation, the mean air temperature in the environment controlled by the circulating ventilation system shown in Figure 2 is calculated with a circulating air ratio α = 15%. The heat source had an emission intensity of 500 W/m2, and the theoretical value of the mean air temperature was calculated by substituting α = 15% into Equation (8). The comparison between theoretical and simulated values is shown in Figure 6. As can be seen from Figure 6, as the release time of particulate matter increases, the mean air temperature in the controlled environment gradually increases and ultimately plateaus. Similarly to the accumulation of pollutants, there is also an upper limit for temperature accumulation. Specifically, the mean air temperature in the controlled environment reached a relatively stable level within 30 s of particle release, and the limit value was 20.75 °C.

Figure 6.

Comparison of simulated and theoretical values of mean air temperature at different times with α = 27.8%.

The average error between the simulation and the theoretical values at different times remained under 10%. Therefore, the numerical simulation of thermal accumulation demonstrates a strong concordance with the theoretical calculation.

4.2. Characteristic Analysis of Pollutant Concentration and Thermal Accumulation

4.2.1. Pollutant Concentration and Thermal Accumulation

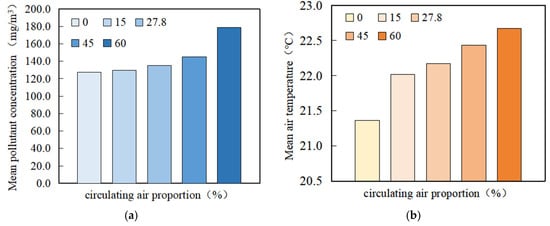

Figure 7a shows the mean pollutant concentration in the controlled environment under different circulating air proportions during the 60 s particle release period. As the proportion of circulating air increases, the amount of fresh air saved increases correspondingly. It is worth mentioning that the total real-time pollutant emissions are reduced, and both the fresh air volume saved and the total real-time emission reduction equal the circulating air volume entering the controlled environment. Figure 7b shows the mean air temperature in the controlled environment under different circulating air proportions during the 90 s particle release period. With the increase in the proportion of circulating air, the mean air temperature increases gradually, but the overall increase ranges from 0.5 °C to 1 °C. This shows that the increase in the proportion of circulating air has minimal effect on the mean air temperature in the controlled environment.

Figure 7.

Comparisons of (a) the mean pollutant concentration and (b) mean air temperature under different circulating air proportions.

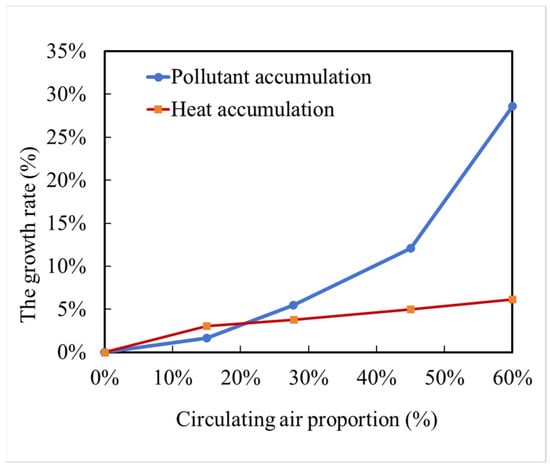

The growth rates of pollutant concentration and thermal accumulation under different proportions of circulating air are shown in Figure 8. As the proportion of circulating air grows, it leads to progressively higher levels of pollutant accumulation and air temperature simultaneously. When using a circulating ventilation system at α = 15%, it results in a 15% reduction in both pollutant emissions and fresh air volume, as opposed to not utilizing such a system. Nevertheless, this advantage is accompanied by a minor increase of 1.66% in the average pollutant concentration and a 3.07% rise in the average air temperature. When α = 27.8%, the system saves 27.8% of pollutant emissions and fresh air volume, with the mean pollutant concentration increasing by 5.5% and the mean air temperature increasing by 3.78%. When α = 45%, the average concentration of pollutants in the controlled environment increases by 12.08%, and the average air temperature increases by 5.01%. As the proportion of circulating air increases, the accumulation of pollutants becomes more severe. When α = 60%, the mean pollutant concentration increases by 28.58%. However, the degree of temperature accumulation is relatively small and the mean air temperature increases by 6.16%. It is concluded that the mean air temperature in the controlled environment is basically not affected by the proportion of circulating air. However, it has a great influence on the mean pollutant concentration in the controlled environment. But, both pollutant and thermal accumulation have upper limits, which can be calculated through Equations (3) and (9).

Figure 8.

The growth rates of pollutant and thermal accumulation under different circulating air proportions.

4.2.2. Real-Time Values of Pollutants and Air Temperature

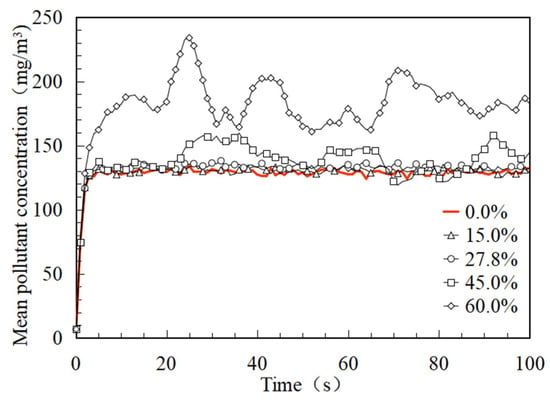

Figure 9 shows the real-time change in the mean pollutant concentration in the controlled environment over time under different circulating air proportions. With the increase in the proportion of circulating air, the real-time mean pollutant concentration also increases. Under a constant circulating air proportion, the mean pollutant concentration rises with extended release time and finally equilibrates. That is to say, there is an upper concentration limit for pollutant accumulation. There is no significant difference between the mean pollutant concentration with α = 0% and that with α = 15% and α = 27.8%. This shows that the proportion of circulating air is within a certain range and does not lead to substantial pollutant accumulation. At the same time, the real-time emissions of pollutants are effectively reduced and the amount of fresh air is reduced.

Figure 9.

Real-time values of the mean pollutant concentration under different circulating air proportions.

When the particulate matter was released for 60 s, the mean pollutant concentration increased by 1.66% compared with α = 15% and α = 0%. The mean pollutant concentration in α = 27.8% increased by 3.91% compared with α = 15%. The mean pollutant concentration in α = 45% increased by 6.95% compared with α = 27.8%. The mean pollutant concentration in α = 60% increased by 18.78% compared with α = 45%. That is, with the increase in the circulating air proportion, the accumulation rate of pollutants is intensified. Therefore, reasonable control of the circulating air proportion is very important for the ventilation effect in the controlled environment.

Figure 10 displays the temporal variation in mean air temperature in the controlled environment for different circulating air proportions. With the increase in the proportion of circulating air, the mean air temperature in the controlled environment also increases. With a constant circulating air proportion, the mean air temperature also progressively increases as release time continues, ultimately plateauing. In other words, there is an upper temperature for thermal accumulation. When the particle is released over 90 s, the mean air temperature increased by 3.07% for α = 15% compared to α = 0%. The mean air temperature of α = 27.8% increased by 0.70% compared to α = 15%. The mean air temperature of α = 45% increased by 1.18% compared to α = 27.8%. The mean temperature of polluted air increased by 1.09% when α = 60% was compared to α = 45%. This demonstrates that as the circulating air proportion increases, the heat accumulation rate shows a slight increase.

Figure 10.

Real-time values of the mean air temperature under different circulating air proportions.

4.3. Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Air Temperature and Pollutants

4.3.1. Velocity Distribution

This section presents numerical simulations of the velocity field distribution in the central cross-section (X = 1.5 m) of the local exhaust hood’s controlled environment under high-temperature heat source radiation. The analysis compares configurations with versus without horizontal air supply from the circulating ventilation system, evaluating various air supply velocities and pollutant source intensities. This study employed circulating air proportions of 0%, 20%, 30%, 50%, 60%, 80%, 90%, and 100%, with a constant pollutant mass flow rate of 35 mg/s. This setup was designed to qualitatively analyze the influence of circulating air on the flow field within the controlled environment.

Figure 11 shows the distribution of Y = 3 m cross-sectional velocities after 100 s of pollutant release within the controlled environment for a pollutant-emanating source strength of 35 mg/s and a heat source temperature of 473.15 K. Figure 11a–d illustrate the velocity contours and streamlines on the cross-section at Y = 3 m, under different circulating air proportions and with horizontal air supply velocities of 0, 0.5, 0.75, 1.25, 1.5, 2, 2.25, and 2.5 m/s.

Figure 11.

Velocity and flow line distribution at X = 1.5 m for various circulating air proportions (source strength: 35 mg/s).

When the circulating ventilation system is not used, 0% circulating air proportion, the flow velocity is larger in the center of the flow field and lower near the wall on both sides, below 0.2 m/s. When employing the circulating ventilation system, the velocity distribution at 20% and 30% circulating air proportion exhibits a ‘T’ shape pattern, with the velocity gradient around the ‘T’ shape increasing from bottom to top. The central section exhibits higher flow velocities (0.8–1 m/s) due to inlet momentum, while the bottom region maintains lower velocities (0–0.2 m/s). These central velocities are significantly greater than those observed without circulating air. With increasing circulating air velocity, vortex formation initiates when the circulating air proportion reaches 50%, the corresponding air velocity attains 1.25 m/s, and the vortex emerges at 1 m height near the wall within the local exhaust hood. When the circulating air proportion reaches 80% (corresponding to a circulating air velocity of 2 m/s), the vortex near the wall disappears, the flow line begins to spread around, and the air is rolled upwards, forming a vortex in the direction of upward dispersion of the source of pollution. Concurrently, increasing circulating air proportion leads to a progressive rise in circulating air velocity and enhanced airflow entrainment effects.

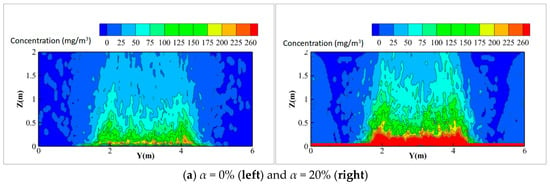

4.3.2. Pollutant Concentration Distribution

The DPM concentration of pollutants at the same cross-section X = 1.5 m under different circulating air proportions is shown in Figure 12a–d. Comparison shows that the pollutant emanation primarily concentrates around the source, exhibiting upward smoke-like dispersion. Pollutant concentration demonstrates an inverse distance relationship—highest near the source and decreasing with distance. Without circulating ventilation, pollutants remain localized and complete spatial dispersion occurs at 20% circulating air proportion. As shown in Figure 12, under ventilation without the circulating system (α = 0%), pollutant dispersion is more concentrated in the middle of the room, and high-temperature particulate matter migrate towards the local exhaust hood vent. The concentration gradient of pollutants decreases with increasing height, with the maximum value located near the pollution source.

Figure 12.

Distribution of pollutant concentration at X = 1.5 m under different circulating air proportions at source strength 35 mg/s.

When the circulating ventilation system was activated, particles began re-entering the local exhaust hood at a height of Z = 1.8 m, with pollutants gradually diffusing throughout the hood. The study found that pollutant concentration distribution varied with different circulating air proportions. At circulating air proportions below 30%, pollutant concentrations were primarily confined to regions below Z = 1.5 m within the exhaust hood. As the circulating air proportion increases, the airspeed on both sides rises, enhancing the suction effect and transporting pollutants away from the source. At 50% circulating air proportion, pollutants begin diffusing toward both end walls. When the proportion reaches 80%, most of the cross-section maintains concentrations below 25 mg/m3, and at 100% proportion, the pollutant distribution achieves full uniformity across the plane.

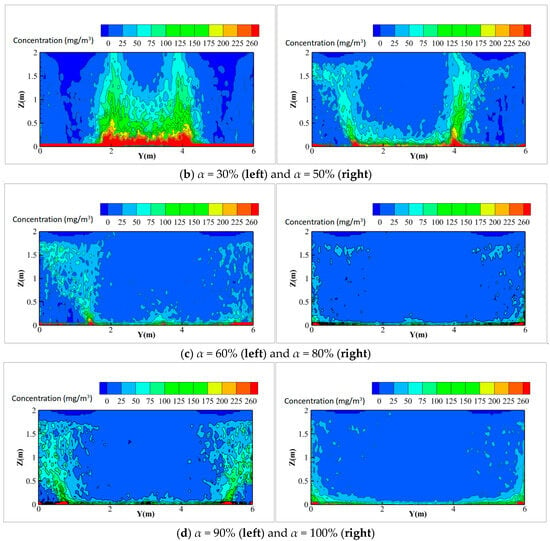

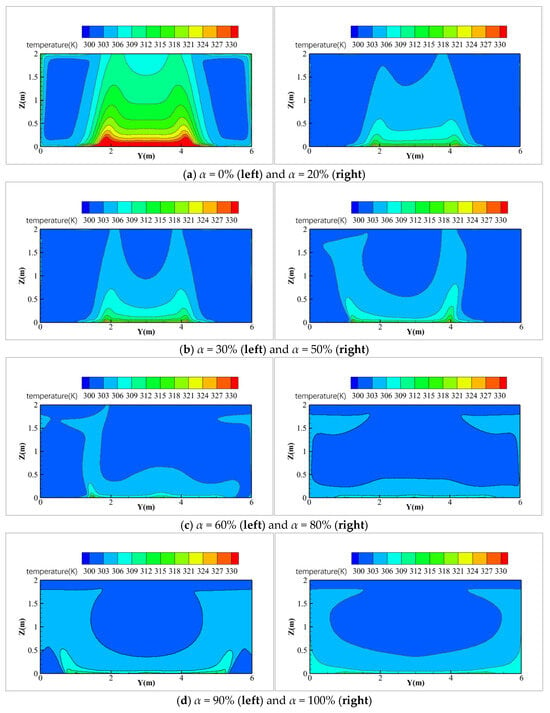

4.3.3. Air Temperature Distribution

Figure 13 displays the temperature distribution at plane X = 1.5 m (source strength: 35 mg/s, heat source temperature: 473.15 K). When the circulating air proportion reaches 60% or higher, the temperature decay in the airflow field accelerates due to enhanced air recirculation. At lower proportions, air temperature outside the pollution source remains stable at 300–303 K. When the circulating air proportion increases to 80%, the temperature gradient around the pollution source begins to basically disappear, and when the proportion of the circulating air proportion is increased to 100%, the temperatures at the bottom reach 306–309 K.

Figure 13.

Distribution of air temperature at X = 1.5 m under different circulating air proportions.

The circulating air proportion significantly impacts airflow field distribution in the controlled environment and temperature decay rate. Therefore, the determination of the circulating air proportion is crucial for the design of circulating air systems.

5. Conclusions

The circulating ventilation system has the advantage of energy conservation and emission reduction, but relevant quantitative research remains limited. This study (i) develops a theoretical model to quantify pollutant accumulation and thermal accumulation; (ii) derives a control method of the proportion of circulating air; (iii) validates using CFD; (iv) analyzes spatiotemporal distribution of pollutants and temperature. The conclusion drawn is as follows:

- (1)

- A real-time calculation model of pollutant concentration and air temperature for discrete pollutant sources in a controlled environment with circulating ventilation system was developed, as shown in Equations (2) and (8). There is an upper limit pollutant concentration, determined by source strength, local exhaust hood air volume, circulating air proportion, dust collector filtration efficiency, emission proportion, and pollutant concentration unevenness coefficient. There is also an upper limit for air temperature, determined by ambient temperature, heat source strength, local exhaust hood air volume, circulating air proportion, return air temperature, emission ratio, and air temperature unevenness coefficient.

- (2)

- Controlling the recirculation air ratio between 0% and 60% resulted in a corresponding increase in pollutant concentration ranging up to 28.58% and a temperature rise of up to 6.16%. For example, when the proportion of circulating air is 27.8%, the concentration of pollutants increases by 5.50%. The air temperature increase is relatively slow, with a 3.78% increase in air temperature. The accumulation of pollutants in the controlled environment was significantly more pronounced than the accumulation of heat. Compared to the condition with a non-circulating ventilation system, the air temperature increased by 1.19 °C and the pollutant concentration increased by 7.43 mg/m3 at α = 27.8%.

- (3)

- The spatial–temporal distribution of pollutants, temperature, and flow field characteristics of discrete sources was investigated by numerical simulation. The results indicated that at a low circulating air proportion (<60%), the low velocity zone at the bottom of the local exhaust hood extended over a large area, and the pollutants mainly accumulated in the bottom region. The temperature gradient was significant, with temperatures increasing closer to the source. When the circulating air proportion is high (≥80%), the dominant vortex formed in the flow field, and the pollutant distribution became more uniform, though this may increase escape risk due to make-up air return.

By selecting an appropriate circulating air proportion, both pollutant and heat accumulation in the controlled environment can be reduced while maintaining effective ventilation, thereby providing theoretical and data support for the efficient and safe operation of semi-enclosed exhaust hoods with the circulating ventilation system. However, the theoretical model of this study is based on assumptions and does not consider the sedimentation, resuspension, and chemical reactions of particulate matter. Although the circulating air control system has been put into use, it has not yet undergone strict quantitative verification in actual factories. We will further explore the impact of assumptions, how the parameters in the model are selected, and the promotion and application of the model in different production processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S., C.S. and W.P.; methodology, W.P. and G.S.; software, H.Z.; validation, H.Z., H.J. and Y.W.; formal analysis, H.Z.; investigation, H.Z.; resources, W.P. and G.S.; data curation, H.Z. and C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z. and W.P.; writing—review and editing, C.S., H.J. and W.P.; visualization, H.Z.; supervision, G.S.; project administration, G.S. and W.P.; funding acquisition, W.P., Y.L. and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (No. 202203021212246), the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (No. 202203021212200), and the special fund for Science and Technology Innovation Teams of Shanxi Province (No. 202304051001011).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the postdoctoral platform provided by the SIPPR Engineering Group Co., Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Gaoju Song and Wuxuan Pan are employed by the company SIPPR Engineering Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

The following symbols are used in this manuscript:

| Symbol | Name | Unit |

| L | air volume of the local exhaust hood | m3/s |

| α | proportion of circulating air | |

| y0 | concentration of pollutants outside the controlled environment | mg/m3 |

| τ | operating time of the circulating air system | s |

| x | source intensity of the pollutant source | mg/s |

| y | pollutant concentration in the controlled environment | mg/m3 |

| η | removing efficiency of dust collector | |

| V | volume of the controlled environment space | m3 |

| k | emission proportion | |

| n | unevenness coefficient of pollutant concentration | |

| T0 | temperature outside the controlled environment | K |

| S | intensity of the heat source | W |

| Ti | temperature within the controlled environment | K |

| Ta | return air temperature of the circulating ventilation system | K |

| c* | dimensionless concentration |

References

- GB 9078-1996; Emission Standard of Air Pollutants for Industrial Kiln and Furnace. MEE (Ministry of Ecology and Environment): Beijing, China, 1996.

- GB 39726-2020; Emission Standard of Air Pollutants for Foundry Industry. MEE (Ministry of Ecology and Environment): Beijing, China, 2020.

- Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Guo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Han, G. Research on current situation and countermeasures of air pollution control of foundry industry in China. Environ. Protect. Sci. 2021, 47, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Zhou, E.; Fang, Y.; Liu, H.; Xu, P. Breakthroughs in China’s foundry industry under the new normal: Energy conservation, emission reduction. In Proceedings of the 27th Chongqing Foundry Annual Conference and 11th National Casting Salvage Engineering Technology Exchange Conference, Chongqing, China, 23 May 2017; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G. Research on Ventilation for Machining Factory with High Oil Mist Concentration; Tianjin University: Tianjin, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, W. Exhaust hood performance and its improvement technologies in industrial buildings: A literature review. Build. Simul. 2024, 17, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Study on Flow Field Characteristics and Contaminant Capture Effect of Vortex Side Suction Exhaust Hood. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C.; Quan, M.; Cao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, X. Improvement of fume capture efficiency of side suction hood with parallel-flow supply air. Environ. Eng. 2021, 39, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y. Study on Performance Optimization and Evaluation Index of Local Exhaust Hood at Welding Station. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Institute of Technology, Shanghai, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Litomisky, A. Exhaust ventilation energy saving in car manufacturing and other industries. Energy Eng. 2007, 104, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczynski, J.S.; Grybos, D. Compensation for the complexity and over-scaling in industrial pneumatic systems by the accumulation and reuse of exhaust air. Appl. Energy 2019, 239, 1130–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarpia, L.; Gugliermetti, F.; Zori, G. Air pollution control for occupational health improvement. WIT Trans. Biomed. Health 2005, 9, 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulou, O.I.; Assimakopoulos, V.D. Indoor environmental conditions of athletic halls: Experimental and numerical investigation. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2006, 86, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P. Application of Controllable Circulation Ventilation and Safety of Local Ventilation. Shandong Coal Sci. Technol. 2019, 2, 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, C. Study on Heat Transfer Characteristics of Industrial Building Inner Surface Under the Coupling Effect of Purified Circulating Air and High Temperature Heat Source. Master’s Thesis, Donghua University, Shanghai, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Gao, J.; Zeng, L.; Hou, Y.; Cao, C.; Tong, L.; Wang, Y. On-demand ventilation and energy conservation of industrial exhaust systems based on stochastic modeling. Energy Build. 2020, 223, 110158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B. Design and Analysis of Casting Cleaning Environment Purification and Dust Removal Engineering. Master’s Thesis, Donghua University, Shanghai, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.; Liu, G.; Gao, J.; Du, B.; Lv, L.; Cao, C.; Ye, W.; Tong, L.; Wang, Y. A circulating ventilation system to concentrate pollutants and reduce exhaust volumes: Case studies with experiments and numerical simulation for the rubber refining process. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 5, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P. Aaberg Exhaust Hood Geometry Optimization and Its Control of High Temperature Heat Source Plumes and Associated Dust. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J. High-temperature Heat Source Plume Field&Associated Powder Dust Control Feature. J. Xi’an Aerotech. Coll. 2011, 29, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.Q.; Liu, J.P.; Xiao, P.; Wen, F. Flow field of high-temperature gases and exhaust hood optimization in iron plant. J. Civ. Archit. Environ. Eng. 2013, 35 (Suppl. S1), 162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.B. Flow Field Characteristics of Exhaust Flow Assisted with a Jet. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 2015, 50, 347–353. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. Thermal Stratification Characteristics of industrial plant with Strong Heat Source and Ventilation System Optimization Strategy. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Y. The Research on Prediction Model of Buoyant Jet in Industrial Building and Optimization of Ventilation System. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, B. Dynamic Thermal Environment Simulation of Industrial Buildings Base on Zone Model. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Study on the Purification Mechanism to Reduce the Accumulation of Harmful Gases in Circulated Ventilation of Foundry. Master’s Thesis, Donghua University, Shanghai, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Study on the Technology of Controlled Circulating Air Purification and Dust Removal Based on Sand Blasting Process. Master’s Thesis, Donghua University, Shanghai, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheed, R.; Mohammadian, A.; Gildeh, H.K. A comparison of standard k–ε and realizable k–ε turbulence models in curved and confluent channels. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2019, 19, 543–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramoul, L.B.; Korichi, A.; Popa, C.; Zaidi, H.; Polidori, G. Numerical study of flow characteristics and pollutant dispersion using three RANS turbulence closure models. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2019, 19, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Zhuang, J.; Diao, Y.; Ren, M.; Zhang, L. Numerical simulation of diffusion characteristics of high-temperature particles generated by multiple pollution sources in welding process. China Environ. Sci. 2022, 42, 2552–2560. [Google Scholar]

- Karadimou, D.P.; Markatos, N.C. Modelling of two-phase, transient airflow and particles distribution in the indoor environment by Large Eddy Simulation. J. Turbul. 2016, 17, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Fan, J.; Cao, Y.; Duan, M. Transport and control of droplets: A comparison between two types of local ventilation airflows. Powder Technol. 2019, 345, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Yu, S.C.M.; Lai, A.C.K. Modeling particle distribution and deposition in indoor environments with a new drift-flux model. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).