1. Introduction

Acceleration-sensitive nonstructural components (NSCs), such as suspended ceilings, medical equipment, HVAC systems, and architectural elements, play a crucial role in the post-earthquake functionality of buildings. Currently, damage acceptance criteria following seismic events have become more stringent, particularly in highly seismic countries such as Chile. Due to the intense tectonic activity associated with the subduction of the Nazca plate, it is expected that a moderate-intensity earthquake should not compromise building functionality, which is especially relevant in critical service structures such as hospitals, power plants, fire stations, and telecommunication facilities [

1].

To ensure such functionality, two fundamental requirements must be met: first, the primary structural system must preserve its integrity, and second, the NSCs must remain operational, since their failure can cause personal injury and compromise the immediate usability of the facility. Recent studies have shown that the costs associated with the repair or replacement of NSCs may even exceed those of the load-bearing structure [

2,

3]. Consequently, the accurate estimation of floor acceleration (PFA) and floor response spectra (FRS) is essential for a reliable performance-based seismic design.

Several studies [

4,

5,

6] have revealed that code-based estimations of PFA and FRS—parameters that are fundamental in NSC seismic design—do not adequately capture the effects of structural irregularities, higher vibration modes, and the nonlinear behavior of both NSCs and the supporting structure. Most international codes, including ASCE 7-16 [

7], Eurocode 8 [

8], and NZS 1170.5 [

9], limit the amplification factor for NSCs to a value of 2.5. However, field observations and numerical simulations have shown that this value can be significantly exceeded when the component’s period approaches the building’s dominant period [

10,

11,

12]. Moreover, linear modeling of NSCs may lead to either underestimation or overestimation of demands, depending on their relative stiffness and location within the structure [

13].

The literature has also emphasized the relevance of factors such as diaphragm flexibility, structural torsion, and the presence of vertical irregularities (e.g., soft stories), which strongly influence the vertical distribution of accelerations [

14,

15]. For this reason, several authors have proposed replacing the exclusive use of PFA with more representative engineering demand parameters, such as averaged spectral acceleration (

) or intensity measures that incorporate the inelastic behavior of the component (e.g., INP) [

16,

17].

Despite the growing interest in analyzing frame systems, a gap still exists in the characterization of floor accelerations in reinforced concrete (RC) shear wall buildings, particularly under severe earthquakes [

18]. These types of structures, common in countries such as Chile, may exhibit concentrated modal responses and significant amplification effects at upper stories.

In this context, it is recognized that the seismic demands imposed on NSCs differ in both magnitude and frequency content from those experienced by the main structure. These differences arise from the dynamic properties of the building, the nonlinear structural behavior, and the NSC’s location within the facility. The same NSC configuration may exhibit distinct responses if placed on a lower or upper floor, or if subjected to seismic excitations with varying spectral content [

1].

Although some modern codes include criteria for estimating acceleration demands on NSCs, these are mostly based on empirical relationships and simplified assumptions. In particular, the Chilean standard NTM 001 adopts linear methods to estimate such demands, which may lead to significant errors when the structure enters the nonlinear range during moderate or severe earthquakes [

19]. Several studies have demonstrated that assuming purely elastic behavior may result in either overestimation or underestimation of acceleration demands, negatively affecting design reliability [

19,

20]. For example, it has been identified that nonlinear behavior can reduce acceleration demands on NSCs whose natural period is close to the fundamental period of the structure. However, in lower floors or when the frequency content of the earthquake is narrow and aligns with the structural period, a more detailed nonlinear analysis is required [

20].

A comparative examination of international seismic provisions highlights important differences in the estimation of acceleration demands on NSCs. While the Chilean Technical Standard NTM 001 adopts a simplified linear framework and prescribes upper and lower bounds calibrated specifically for Chilean seismic conditions, international codes such as ASCE 7-16 [

7] and Eurocode 8 [

8] introduce empirical amplification factors and alternative dynamic procedures that account more explicitly for modal participation and higher mode effects. This comparison underscores both the strengths of NTM 001—namely its alignment with local seismic hazard and construction practices—and its limitations when contrasted with the more generalized and empirically supported formulations of international standards.

Two particularly relevant studies in the field have served as benchmarks for the present research. The first, by Vukobratović and Ruggieri [

21], employs nonlinear response history analysis (RHA) as a reference tool to evaluate acceleration demands on the floors of RC shear wall buildings. This study focuses on a twelve-story building designed according to Eurocode 8, composed of uncoupled cantilever walls, and aims to validate a semi-empirical “direct method” for determining maximum floor accelerations and response spectra. The second study, by Magliulo and D’Angela [

13], develops a general methodological framework based on incremental dynamic analysis (IDA) of inelastic SDOF systems modeled in OpenSees, in order to establish statistical criteria and fragility curves applicable to different frequencies and types of components. This work provides a theoretical and generalizable perspective, employing floor motions obtained from the CESMD database.

In contrast to the Eurocode-based parametric approach of Vukobratović and Ruggieri, which assumes concentrated plastic behavior and neglects torsional effects, the present study explicitly incorporates both material and geometric nonlinearities through fiber-based finite elements, uses real seismic records from Chilean earthquakes, and analyzes the amplification of accelerations along the building height. Regarding the study by Magliulo and D’Angela, the present work adopts a more contextualized approach, analyzing in SeismoStruct a typical Chilean reinforced concrete shear wall building subjected to real national earthquake records, with the purpose of evaluating the validity of the amplification factors defined in the Chilean standard NTM 001.

Recent advances in machine-learning (ML) techniques have shown promising potential for enhancing seismic structural response analysis, particularly by identifying complex correlations between intensity measures and structural demands. For example, Wang and Luo [

22] propose a low-rank matrix-guided least squares support vector machine regression to efficiently correlate seismic intensity measures with structural response metrics for RC frame buildings, thereby reducing computational cost. Meanwhile, Lazaridis et al. [

23] evaluate the ability of multiple ML algorithms to predict damage in an 8-storey RC frame under single and multiple seismic events, demonstrating the value of data-driven models in performance assessment. These studies support our work by highlighting how data-driven approaches can complement nonlinear dynamic simulation and model-based analyses, particularly when deriving amplification factors and response spectra for nonstructural components (NSCs) in high-seismic contexts.

The present study aims to characterize the magnitude and distribution of seismic acceleration demands experienced by NSCs in RC shear wall structures. To this end, a three-dimensional model developed in SeismoStruct [

24,

25] is employed, incorporating the nonlinear behavior of the structural system. NSCs are not modeled explicitly, under the assumption that their mass is negligible compared to that of the main structure, which is valid when the weight ratio is lower than 0.01 [

26]. Finally, the simulation results are analyzed, evaluating the influence of the NSCs’ location within the structure on PFA, pseudo-acceleration, and the resulting dynamic amplification factors.

2. Methodology

The primary objective of this study is to quantify the seismic demand affecting nonstructural components and systems (NSCs) in Chilean buildings typically structured with RC shear walls, in order to assess their compatibility with the performance requirements established in the current national code.

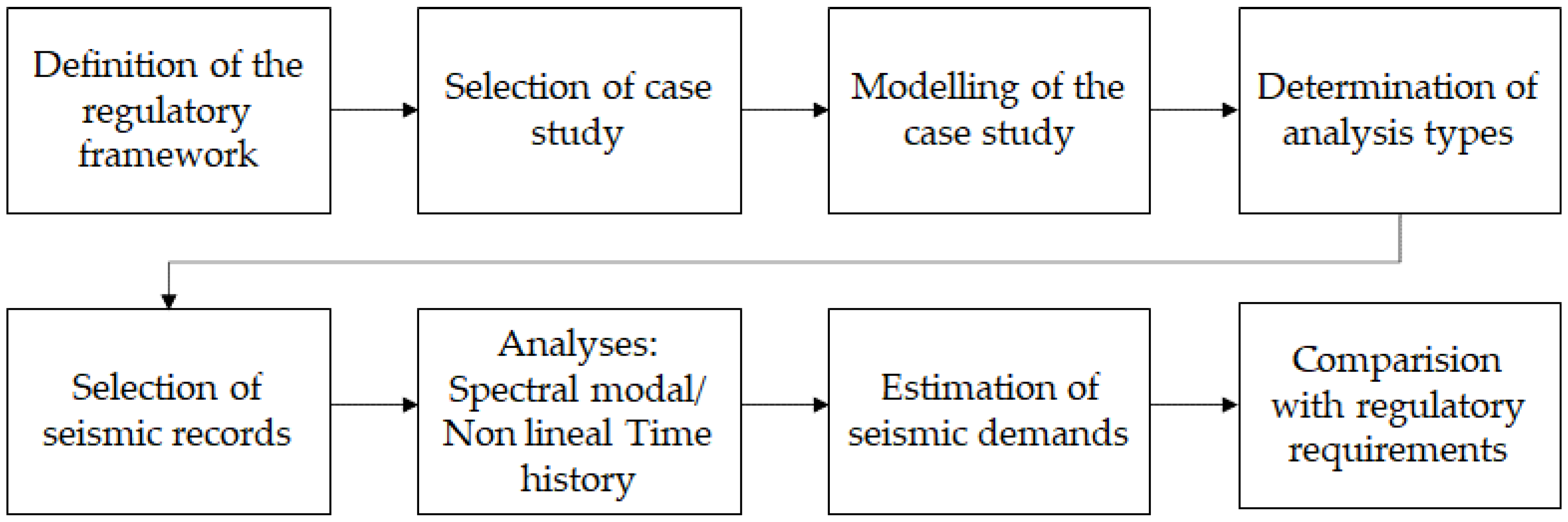

Figure 1 graphically summarizes the adopted methodological approach.

The evaluation was carried out in accordance with the Technical Standard MINVU NTM 001 “Seismic Design of Nonstructural Components and Systems” [

27], which establishes the minimum design criteria to ensure the adequate performance of these elements under seismic events. This standard is applied jointly with the Chilean structural code NCh433.Of96 and Supreme Decrees No. 60 and No. 61 [

28], enabling a coherent regulatory integration in the seismic design of buildings.

For the development of the study, a seven-story prototype building structured with RC shear walls was selected as the case study, a typology widely used in Chile’s residential building stock. The structural model was developed following the guidelines of NCh433.Of96 Mod.2009, considering both gravitational loads (dead and live) and the geometric and strength characteristics of the system.

The structural analysis was addressed through the generation of two computational models of the building: one linear and one nonlinear. Both were subjected to different analysis procedures to estimate the dynamic response induced by seismic excitations. In particular, two analytical approaches were employed: modal response spectrum analysis, in accordance with the procedures of NCh433.Of96 Mod.2009, and nonlinear dynamic time history analysis, in order to capture relevant inelastic effects.

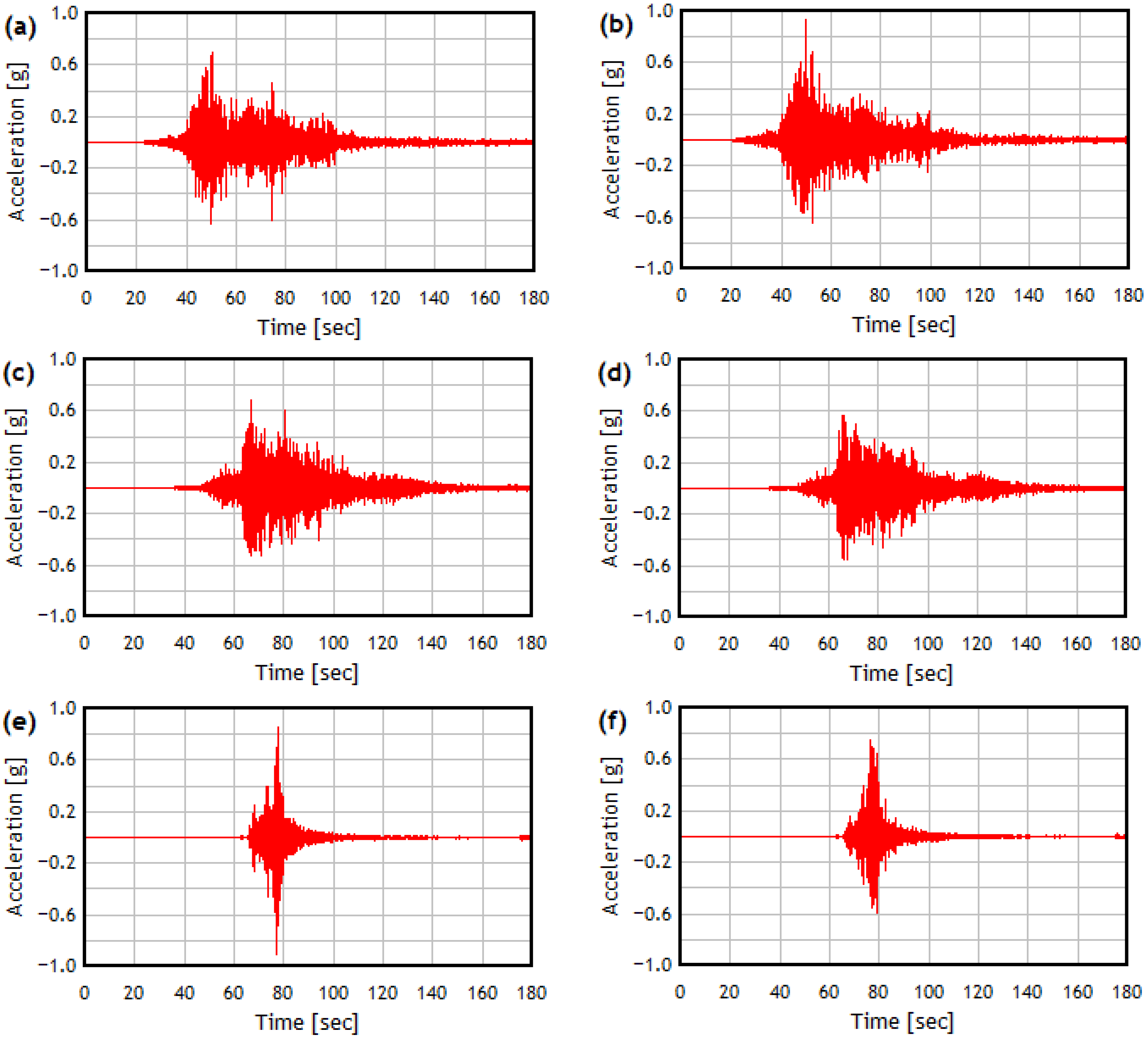

The seismic excitations used consisted of real records representative of the national seismic hazard, selected for their suitability in terms of intensity and frequency content. Accelerograms from events that occurred in Chile in 2010, 2015, and 2017 were used, obtained from official databases.

From the dynamic analyses, maximum absolute accelerations per story were obtained and normalized with respect to the peak ground acceleration of each record, allowing the derivation of floor amplification factors. Likewise, spectral pseudo-accelerations and their corresponding amplification factors were calculated, providing a detailed view of the dynamic behavior affecting NSCs along the building height.

Finally, the results obtained from the linear and nonlinear models were compared with the demand limits defined in Technical Standard MINVU NTM 001, enabling the assessment of the compliance of the observed behavior with the performance criteria required for NSCs. This comparison constitutes a key input for the conclusions of the study.

3. Description of the Building Under Study

The structural model corresponds to a seven-story residential building, including one basement level, located in the city of Quillota, Valparaíso Region, Chile—an area of high seismic exposure. The selected typology represents a typical configuration of Chilean RC buildings, characterized by the predominant use of shear walls arranged orthogonally in both directions, placed in the central core as well as in perimeter zones, ensuring the lateral stiffness required to resist seismic loads.

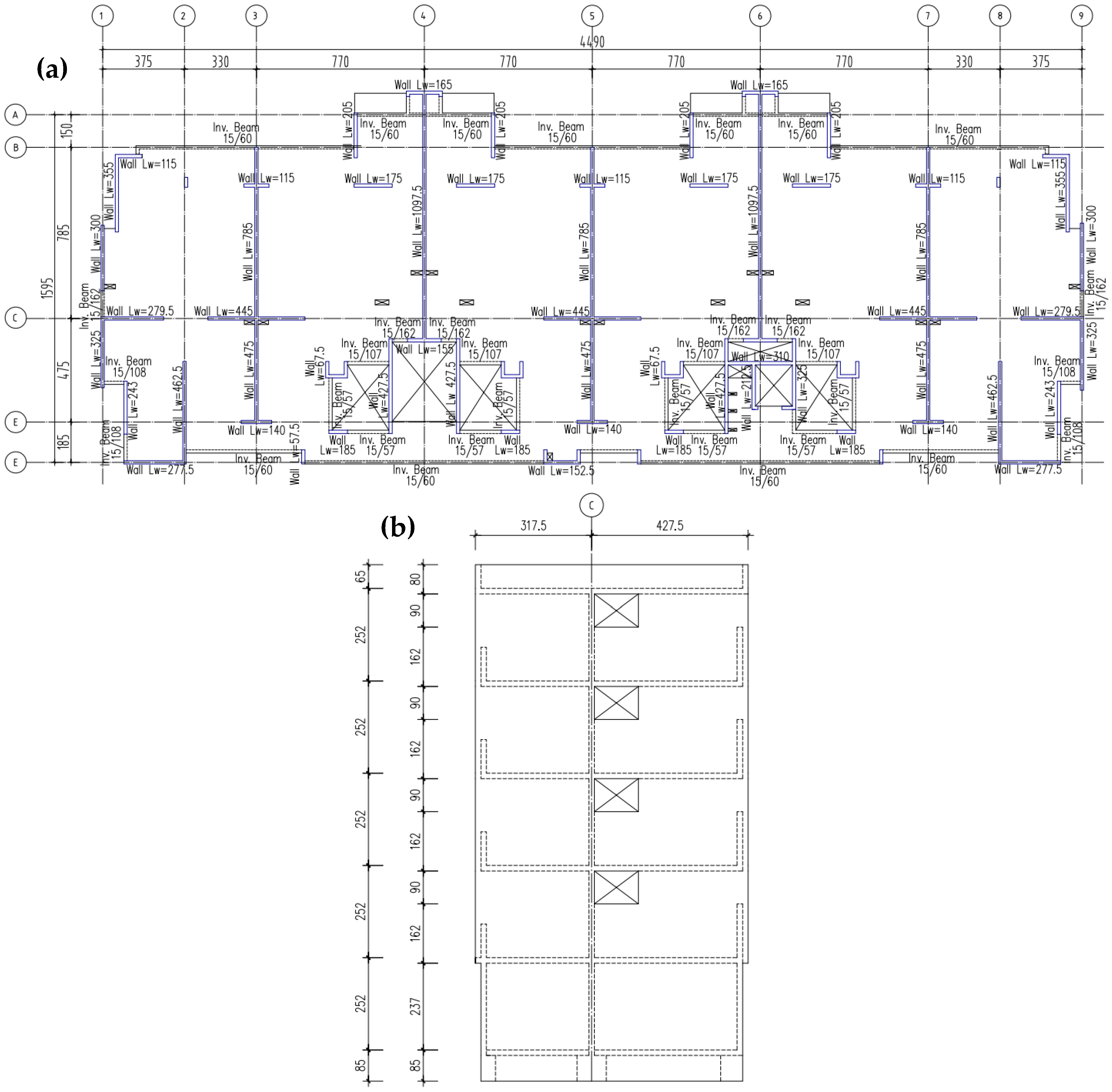

The building was designed in accordance with current Chilean regulations, following a prescriptive approach. The shear walls have a thickness of 0.15 m, the same as the floor slabs, while an additional structural element characteristic of this type of construction is the use of inverted beams, whose main function is to provide a stiffer connection between walls. The properties of the concrete and reinforcing steel used in the project are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2. This model has been employed in previous studies to characterize the dynamic response of the structural typology under consideration [

29,

30]. In the analyzed building, these beams run along the entire perimeter of the structure, also meeting architectural requirements in the main façade, where they allow for the placement of windows without compromising structural performance (see

Figure 2). For a more comprehensive review of the Chilean design practice and building characterization, the interested readers can refer to the following article [

31].

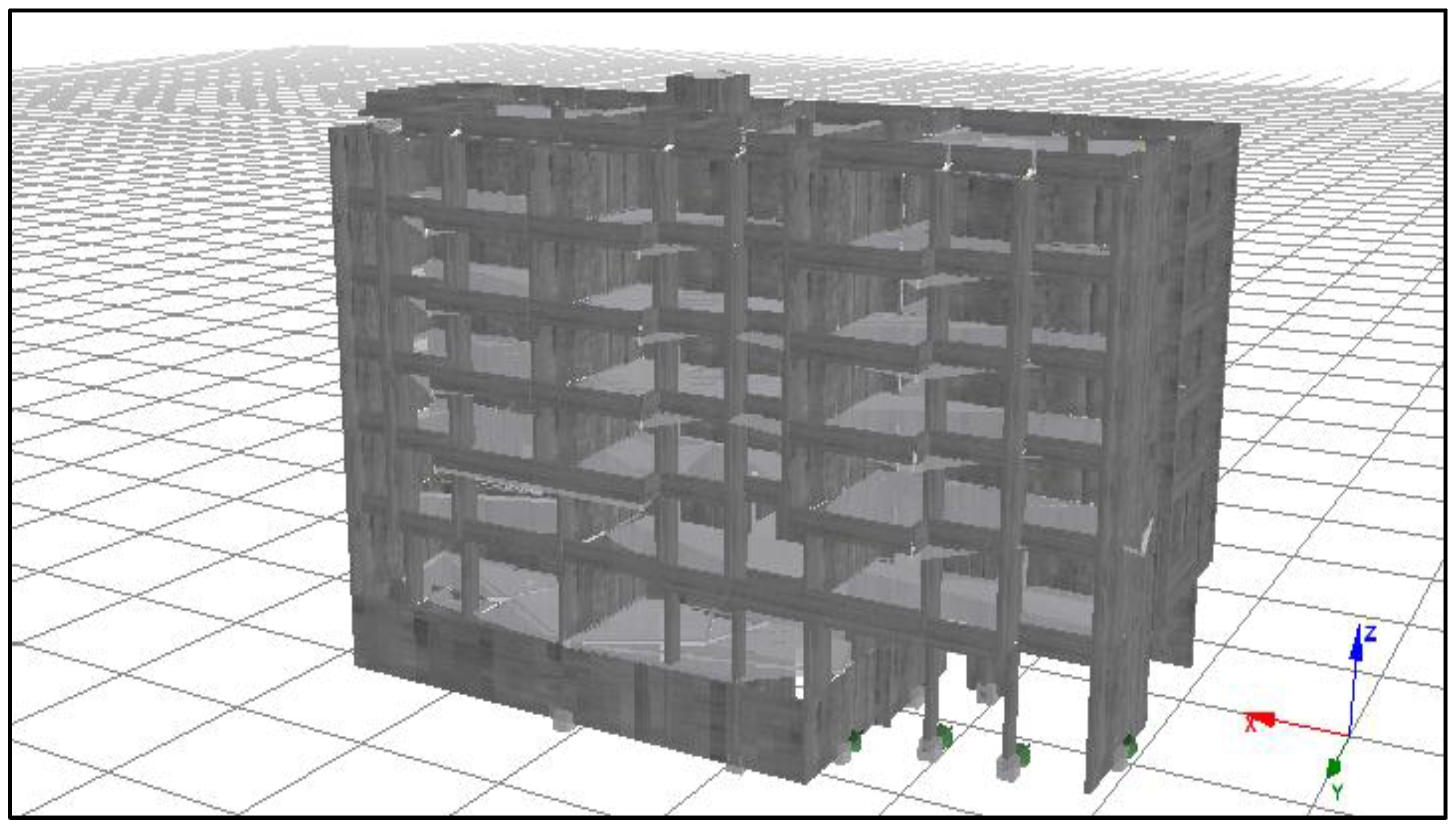

Based on its geometric characteristics and mechanical properties, a representative mathematical model was developed using the SeismoStruct program [

32], which was employed for the dynamic analyses forming the basis of this study. The analytical model of the case study is shown in

Figure 3. Readers interested in the dynamic response of this structural typology may refer to [

33].

In this analytical model, the walls and beams elements were defined using a fiber section model determines the state of an element by integrating the responses of the individual fibers that make up the wall cross-section. By incorporating the material stress–strain relationships and incorporating the fiber-level responses, this model inherently captures both axial and flexural behaviors of the element, with stiffness updated at each analysis step. As for the plasticity definition, the inelastic force-based plastic hinge frame element type infrmFBPH is used, which incorporates a displacement and force-based formulation with distributed inelasticity. This approach concentrates inelastic behavior within a predefined segment of the element. Within the region where plastic hinges are expected to form, fiber-distributed plasticity is applied. Thus, the model effectively combines concentrated and distributed plasticity strategies, resulting in a refined plastic hinge-based representation.

For material behavior, the nonlinear constitutive models proposed by Mander et al. [

34] and Menegotto and Pinto [

35] were employed to characterize concrete and reinforcing steel, respectively. The effects of transverse confinement in the concrete core and the presence of longitudinal steel bars in both walls and beams were accounted for by enhancing the concrete strength, in accordance with the Mander model. Regarding geometric nonlinearities, P–Δ effects were activated in all simulations Furthermore, a 5% of the critical damping is applied to the first and third fundamental modes.

The horizontal force transfer system in the model comprises the concrete slab of the structure, which is considered as a rigid diaphragm constraint, consistent with the design of typical Chilean RC buildings.

However, the analytical model presents limitations, as it does not consider the interaction of steel and concrete elements, such as bond slip and steel reinforcement buckling, besides the deformation compatibility, as its application is not considered in the scope of this article.

Furthermore, the time integration scheme was carried out using the Newmark-beta method with γ = 0.5 and β = 0.25, and convergence was verified at each time step through force and displacement tolerances of 1 × 10−3.

To verify the accuracy and reliability of the numerical model, a two-step validation process was conducted. First, the fundamental vibration periods and corresponding mode shapes obtained from the finite element model were compared with those estimated using the empirical expressions of the Chilean seismic code NCh433 Mod.2009 [

28], showing good agreement. Second, the dynamic characteristics and response trends were contrasted with results reported for similar RC shear wall buildings experimentally and numerically studied in previous research [

29,

30]. The observed consistency confirmed the adequacy of the modeling approach for representing the global behavior of the structural typology under consideration.

The vibration periods of the structural model, as well as their associated masses, are presented in

Table 3.

3.1. Description of the Seismic Excitation

As mentioned earlier, representative seismic records from three events in Chile were considered: Maule 2010, Coquimbo 2015, and Valparaíso 2017, obtained from the CESMD database [

36]. For each of these events, the horizontal components (x and y directions) were used to compute pseudo-acceleration spectra by means of the SeismoSignal software [

37].

In order to represent different levels of seismic demand in the analysis, the records were scaled according to the guidelines of the Achisina manual [

38]. This procedure defines two design scenarios: Design Earthquake (DE), in which the accelerograms are adjusted to the elastic displacement spectrum with a 17% increase. The main characteristics of the records employed in this study are summarized in

Table 4, while the acceleration records of each of their components are illustrated in

Figure 4.

A summary of the characteristics of the seismic records employed is presented below: the acceleration records were matched following the procedure described in the Achisina Manual [

38], which defines seismic hazard in Chile based on the elastic displacement spectrum derived from the Mw 8.8 earthquake that occurred on 27 February 2010. The software used requires the definition of the design spectrum in terms of spectral acceleration

. This spectrum can be obtained by applying the following conversion equation:

In the above equation, and represent the structural frequency and period, respectively. The spectral displacement ordinates () are increased by 17%, as established in the aforementioned Achisina manual, to define the design-level spectrum (SD). The matching process was carried out using this target spectrum, considering periods ranging from to , which adequately cover the vibration periods that may develop in the archetypes, especially under the elongation effects caused by damage progression during nonlinear analysis.

3.2. Time History Analyses

Time history simulations were performed using the SeismoStruct software, enabling the capture of the nonlinear dynamic response of the structure under the previously defined seismic excitations. In each simulation, absolute acceleration time histories were recorded at all building levels. From these responses, the maximum PFA per floor and the FRS were calculated, which are key parameters in assessing the seismic demand acting on NSCs. Once the PFAs and FRS were obtained for each floor and for the excitation scenario (DE), a comparative analysis was conducted to evaluate the sensitivity of these demands to different levels of seismic intensity and how they influence the design of NSCs. Furthermore, the results obtained from nonlinear time history analyses were contrasted with those derived from alternative methods permitted by the national code, providing a cross-validation framework between approaches.

3.3. Seismic Design Demand for NSCs According to NTM 001 [27]

The estimation of seismic demand on NSCs was based on the guidelines established by Technical Standard MINVU NTM 001, which sets minimum design criteria for components permanently attached to structures, including their anchorage. According to

Section 6 of this standard, the horizontal design seismic force,

, can be determined using three methods, the most widely employed being that described by Equation (1)

.

where

is a parameter dependent on the soil type, defined in

Table 5 (according to D.S. 61 of 2011);

is the dynamic amplification factor (ranging from 1.0 to 2.5);

is the component importance factor (ranging from 1.0 to 1.5);

is the component weight;

is the response modification factor (ranging from 1 to 8);

is the height of the component’s attachment point in the structure relative to the base;

is the average height of the structure’s roof level relative to the base; and

is the acceleration of gravity in cm/s

2. The standard also establishes upper and lower bounds for this force, given by Equations (2) and (3), respectively:

Table 5.

values according to soil type [

7].

Table 5.

values according to soil type [

7].

| Soil Type | |

|---|

| A | 977 Z |

| B | 1101 Z |

| C | 1144 Z |

| D | 1455 Z |

| E | 1576 Z |

Table 6.

Z values according to seismic zone [

23].

Table 6.

Z values according to seismic zone [

23].

As mentioned earlier, instead of determining the force

according to Equation (1), it is permitted to obtain the accelerations at any level using the response spectrum analysis procedure specified in NCh433.Of96 Mod.2009 or in NCh 2745 [

39]. The seismic demand must be determined according to Equation (4).

where

is the acceleration at the component’s attachment level (in units of

), obtained through response spectrum analysis considering that the reduction factor (

in NCh433.Of96 Mod.2009 and

in NCh 2745) is taken equal to unity, and

is a torsional amplification factor determined according to Equation (5):

where

is the maximum seismic lateral displacement at the component’s attachment level, obtained through response spectrum analysis, and

is the average value of the seismic lateral displacements at the end points of the component’s attachment level, also obtained through response spectrum analysis.

Notwithstanding the above, it is permitted to determine the demand

according to Equation (6):

where

is the acceleration at the component’s attachment level (in units of g), obtained through time-history analysis.

4. Results

The results obtained from the time history analyses are presented below, from which the maximum floor acceleration and the corresponding spectral pseudo-acceleration for each floor’s acceleration history were derived. The maximum absolute floor acceleration was normalized with respect to the peak ground acceleration (PGA), yielding the amplification factor. Following the same approach, an amplification factor behavior was sought in terms of spectral pseudo-accelerations, by matching the spectral pseudo-acceleration obtained from the accelerogram with the floor pseudo-acceleration, thus obtaining a dynamic amplification spectrum for each floor. In parallel, the demand in terms of forces acting on NSCs was calculated in accordance with Standard NTM 001.

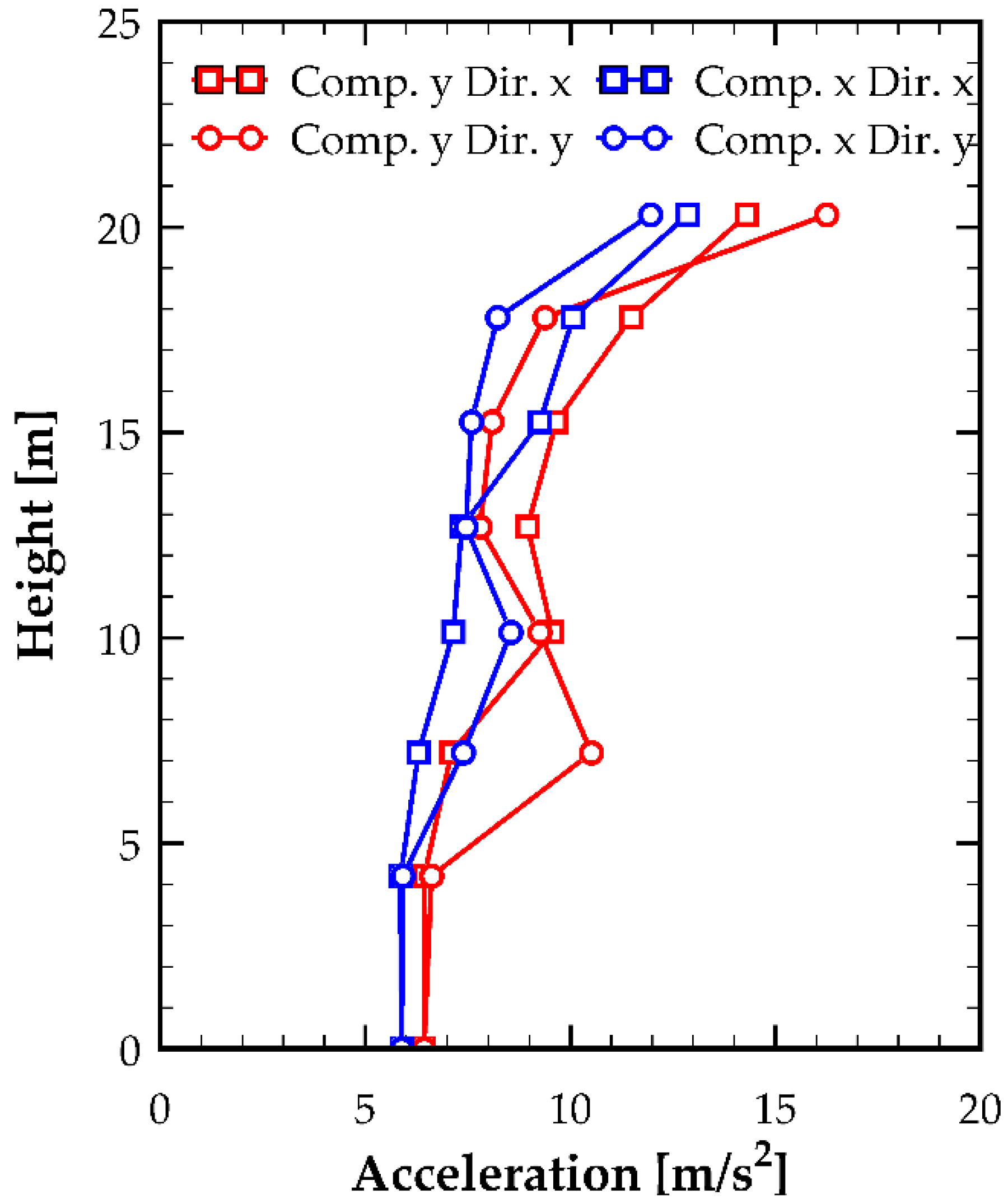

For clarity, the presentation of results is organized according to the type of seismic excitation applied to the model. From the time history analysis of the Coquimbo 2015 earthquake, acceleration time histories were obtained, and from these, the maximum PFA values were determined from floor −1 to the roof. These results were summarized by earthquake component and analysis direction, as shown in

Figure 5 and

Table 7.

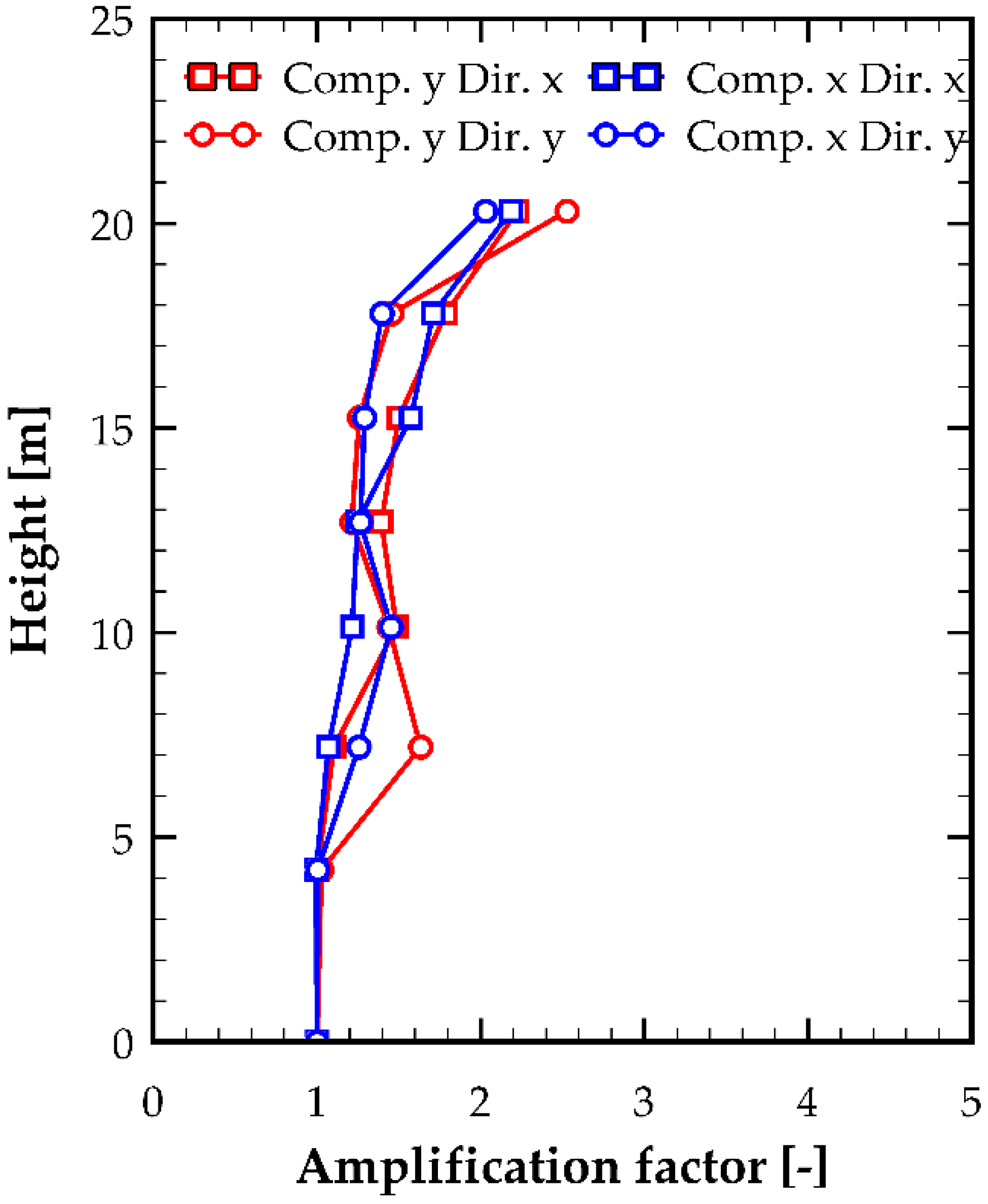

To quantify the increase in floor acceleration, the amplification factor was calculated, defined as the ratio between the floor PFA and the PGA of the seismic record, as shown in

Figure 6.

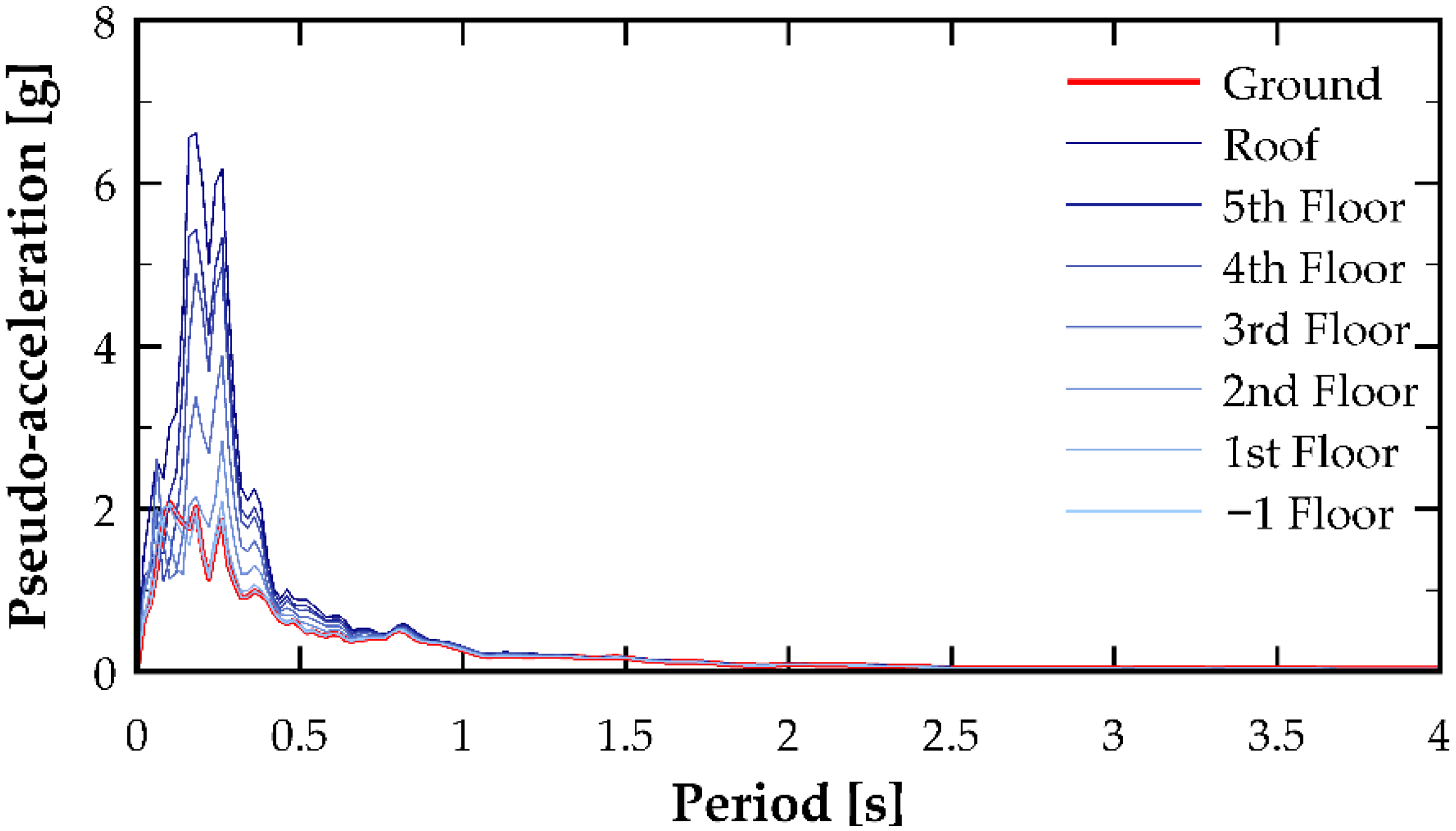

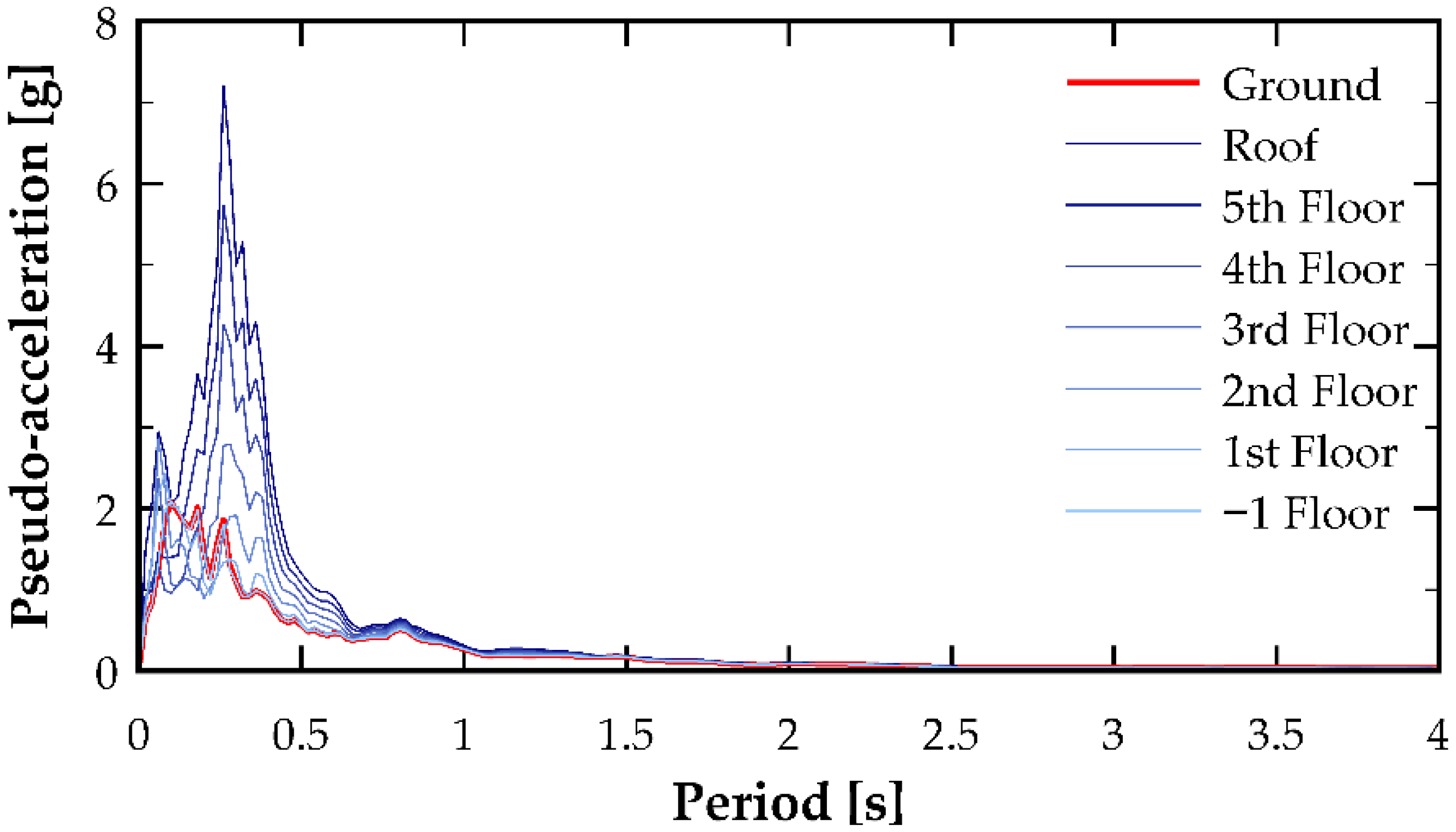

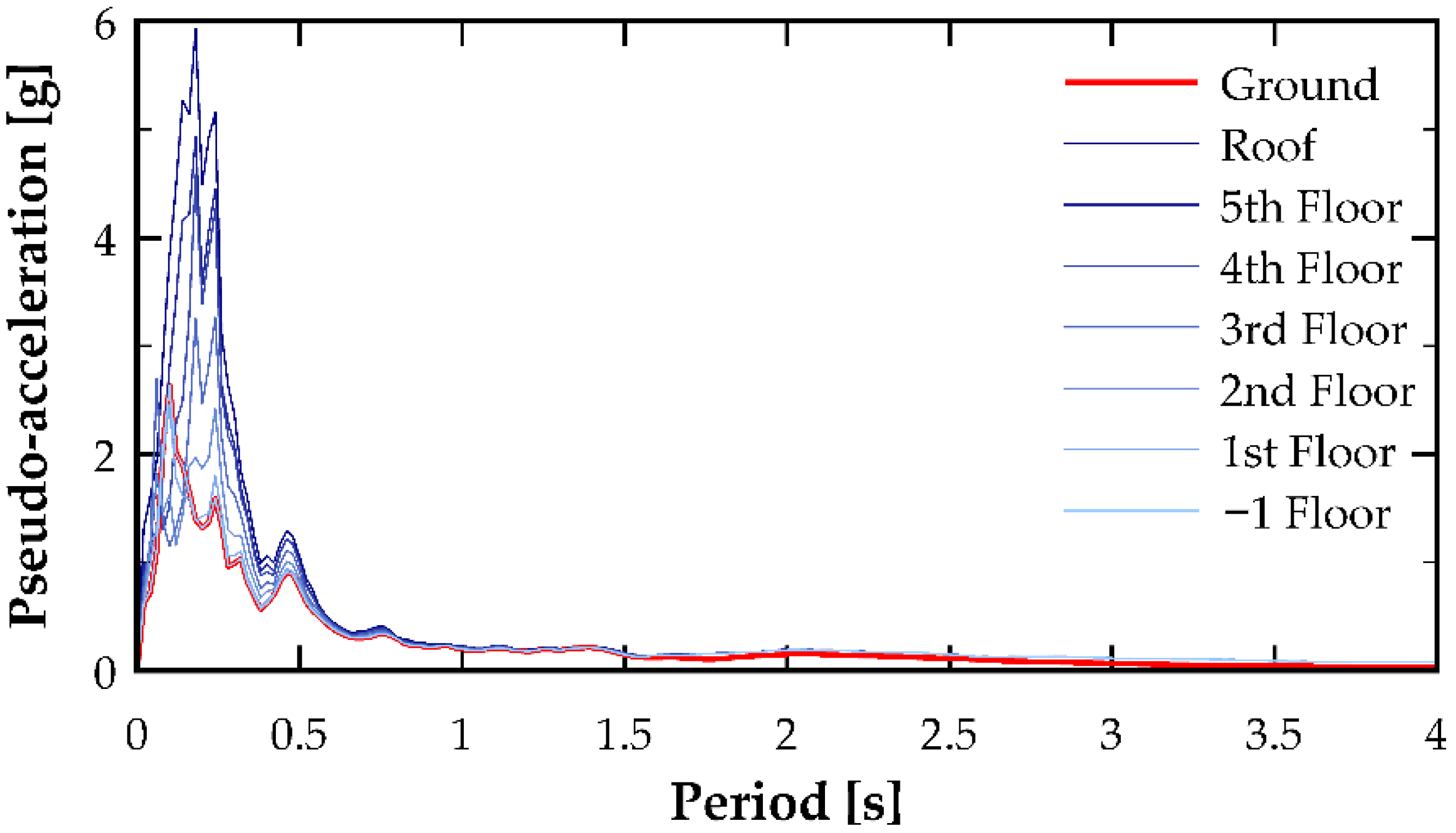

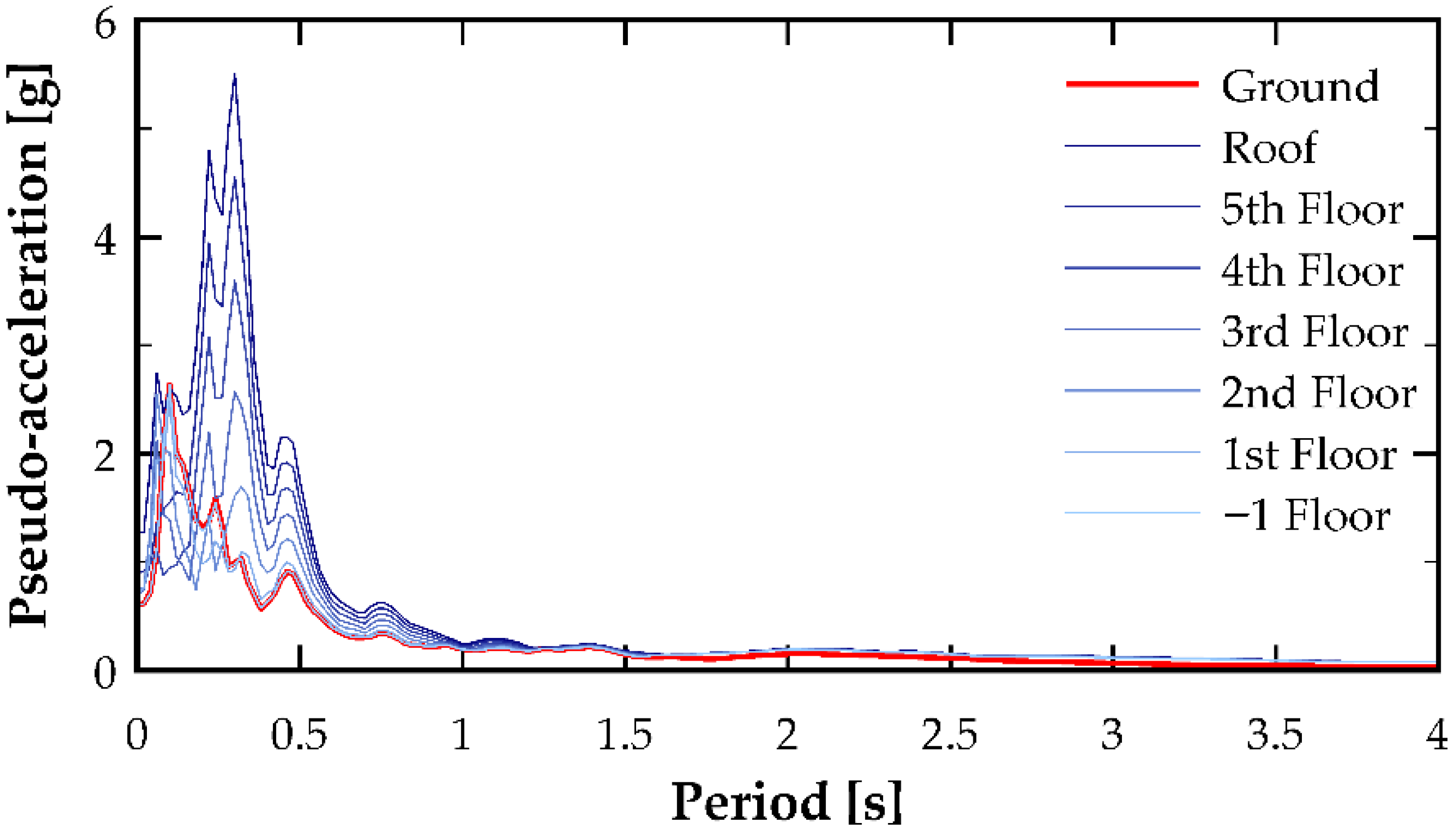

The

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 show the floor pseudo-accelerations obtained after processing the floor acceleration time histories in the SeismoSignal software, organized by earthquake component and analysis direction. Subsequently, a figure is presented that summarizes the peaks for each floor. Although the fundamental period of the analyzed building is relatively short (0.1697 s), the spectral range in the figures was intentionally extended up to 4.0 s in order to capture potential higher-mode contributions and period-elongation effects associated with nonlinear structural response. Under strong shaking, stiffness degradation may shift the effective dynamic properties of the system, resulting in increased participation of longer-period components. Including this extended spectral range therefore allows a more complete visualization of possible amplification mechanisms and ensures that the analysis does not overlook response features that emerge beyond the elastic period of the structure.

From

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, the maximum values of the ratio between the floor pseudo-acceleration and the spectral pseudo-acceleration of the accelerogram were extracted for each floor over time, in order to observe the trend of the amplification factor in a linear manner.

The high pseudo-spectral acceleration values observed at very short vibration periods in

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 reflect not only characteristics of the seismic input but, more importantly, the influence of the building’s nonlinear dynamic response. Under strong ground shaking, stiffness degradation and transient period elongation modify the distribution of modal participation, enabling higher-mode effects to contribute more significantly to the acceleration demands transmitted to upper floors. These mechanisms can result in substantial short-period amplification, which directly affects the seismic forces experienced by NSCs and building contents. Consequently, the interaction between nonlinear structural behavior and floor acceleration demands must be explicitly recognized, as neglecting these effects could lead to significant underestimation of the demands relevant for the design and protection of acceleration-sensitive systems.

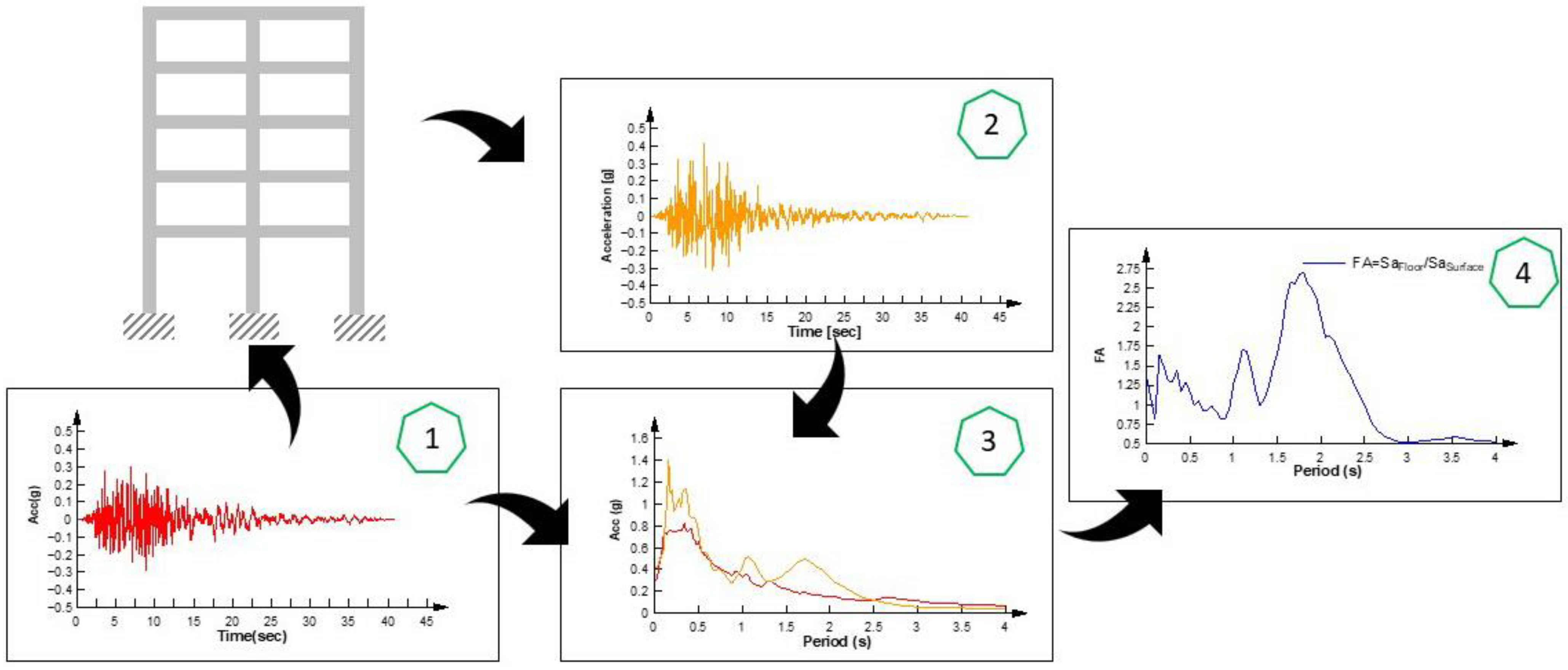

In order to obtain the floor acceleration amplification factor, the following methodology, illustrated in

Figure 11, is proposed and applied. The procedure begins with the accelerogram applied to the structure for conducting the time history analysis (Step 1). The time history analysis is then carried out, yielding the acceleration histories at each floor of the structure, which are subsequently used to determine a response spectrum for each floor (Step 2). With this accelerogram, the ground surface response spectrum is determined and combined with the response spectrum of each floor (Step 3). The floor acceleration amplification factor is calculated by dividing the ordinates of the corresponding floor acceleration spectrum by the ordinates of the ground surface acceleration spectrum (Step 4).

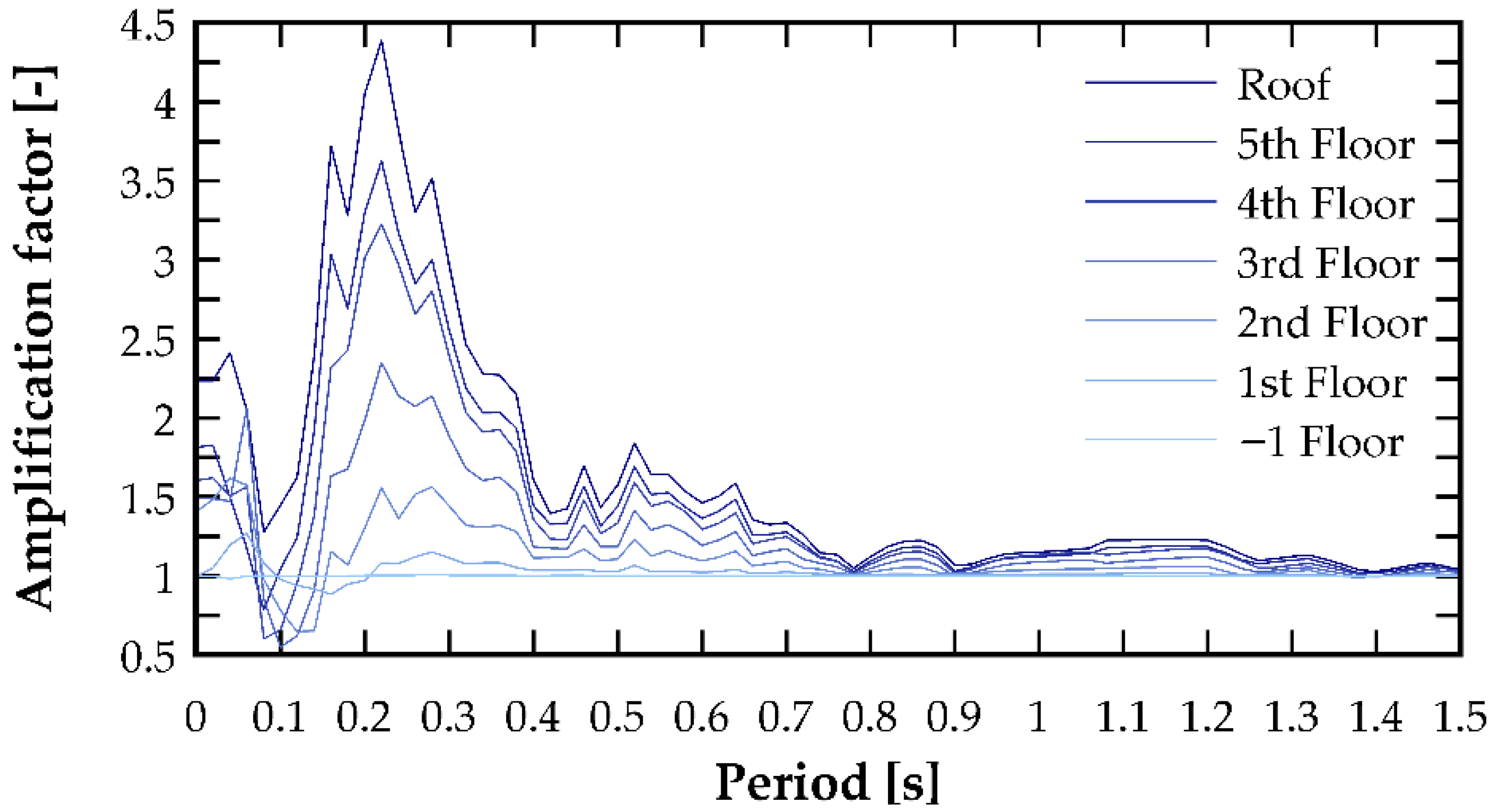

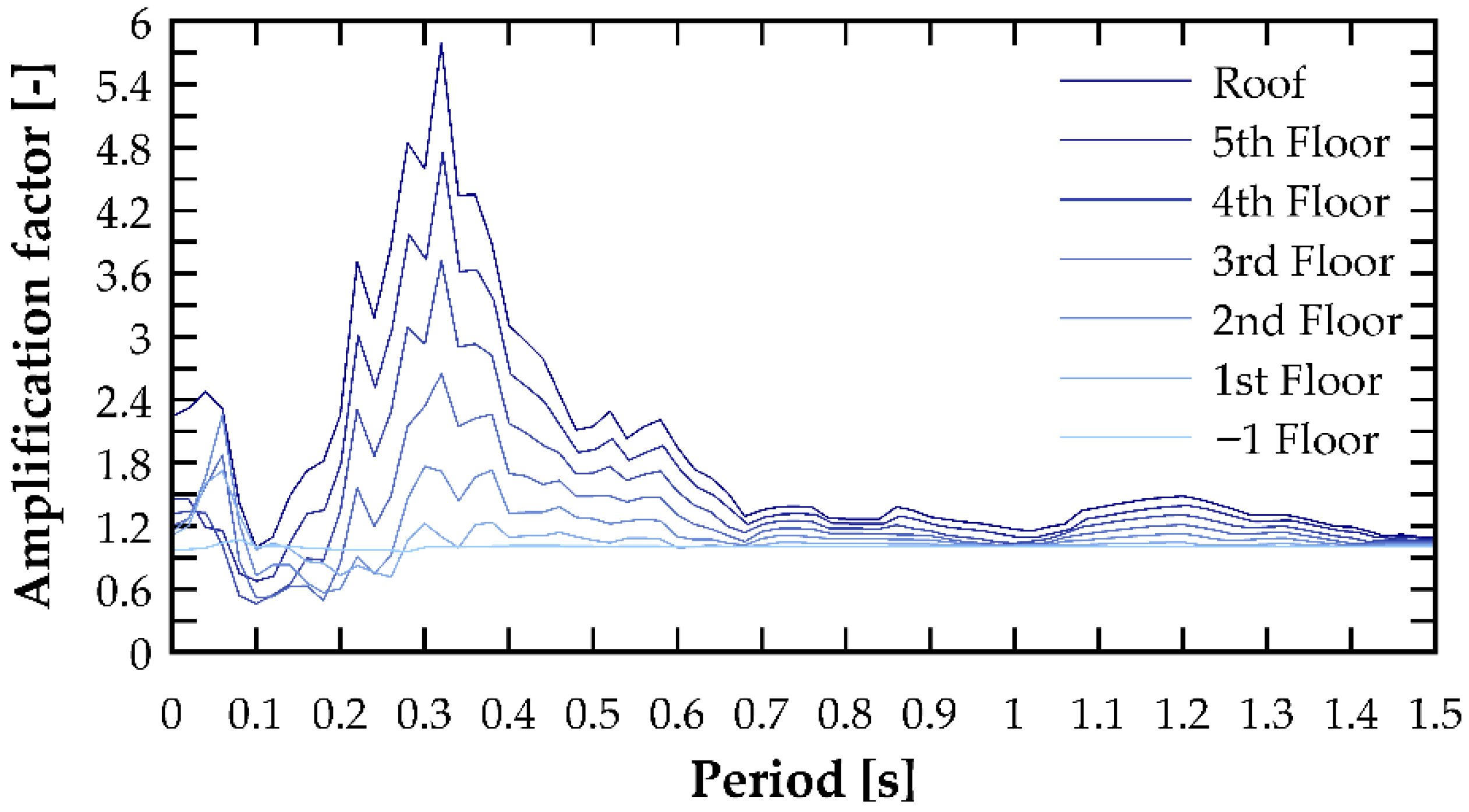

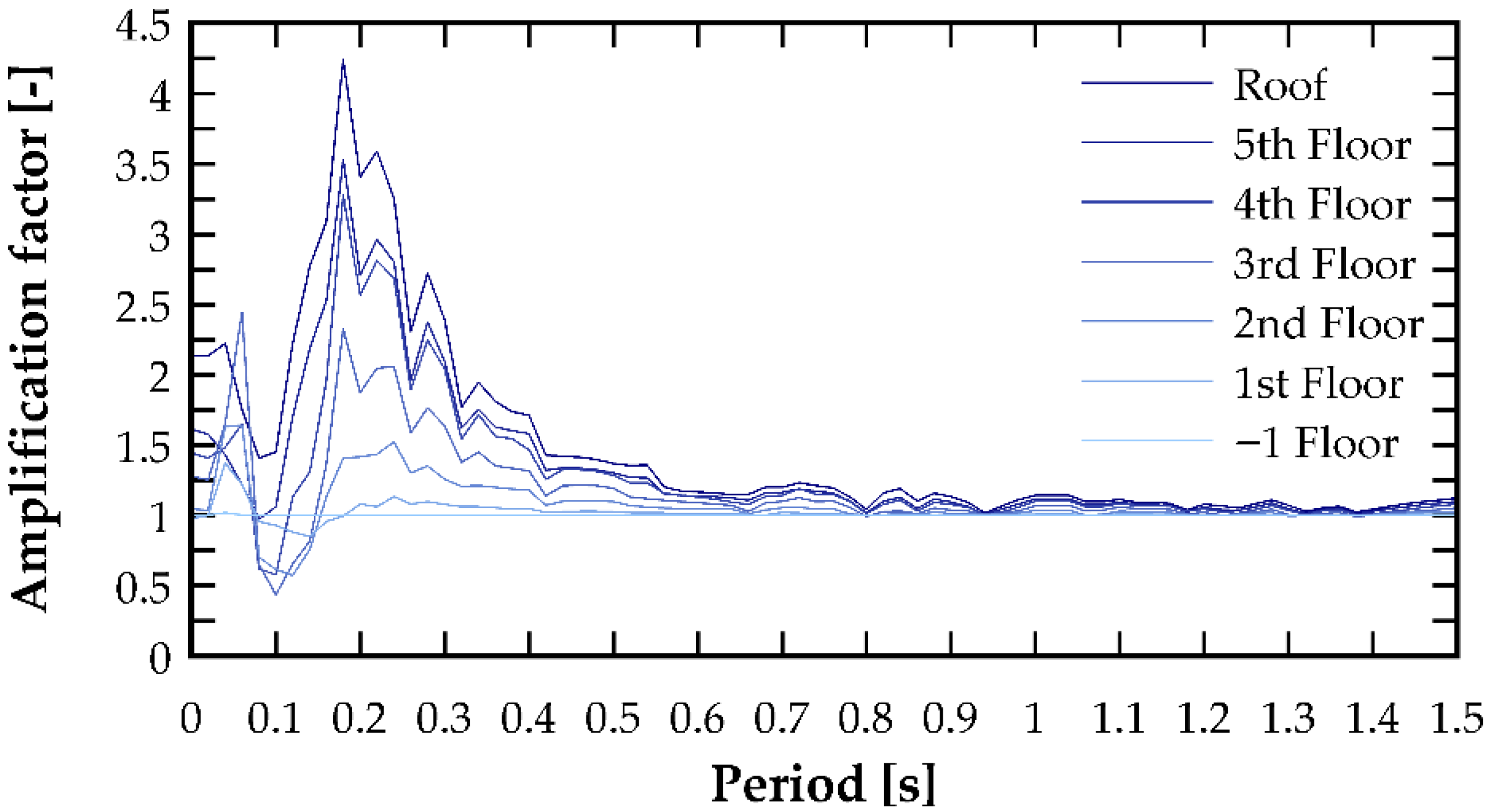

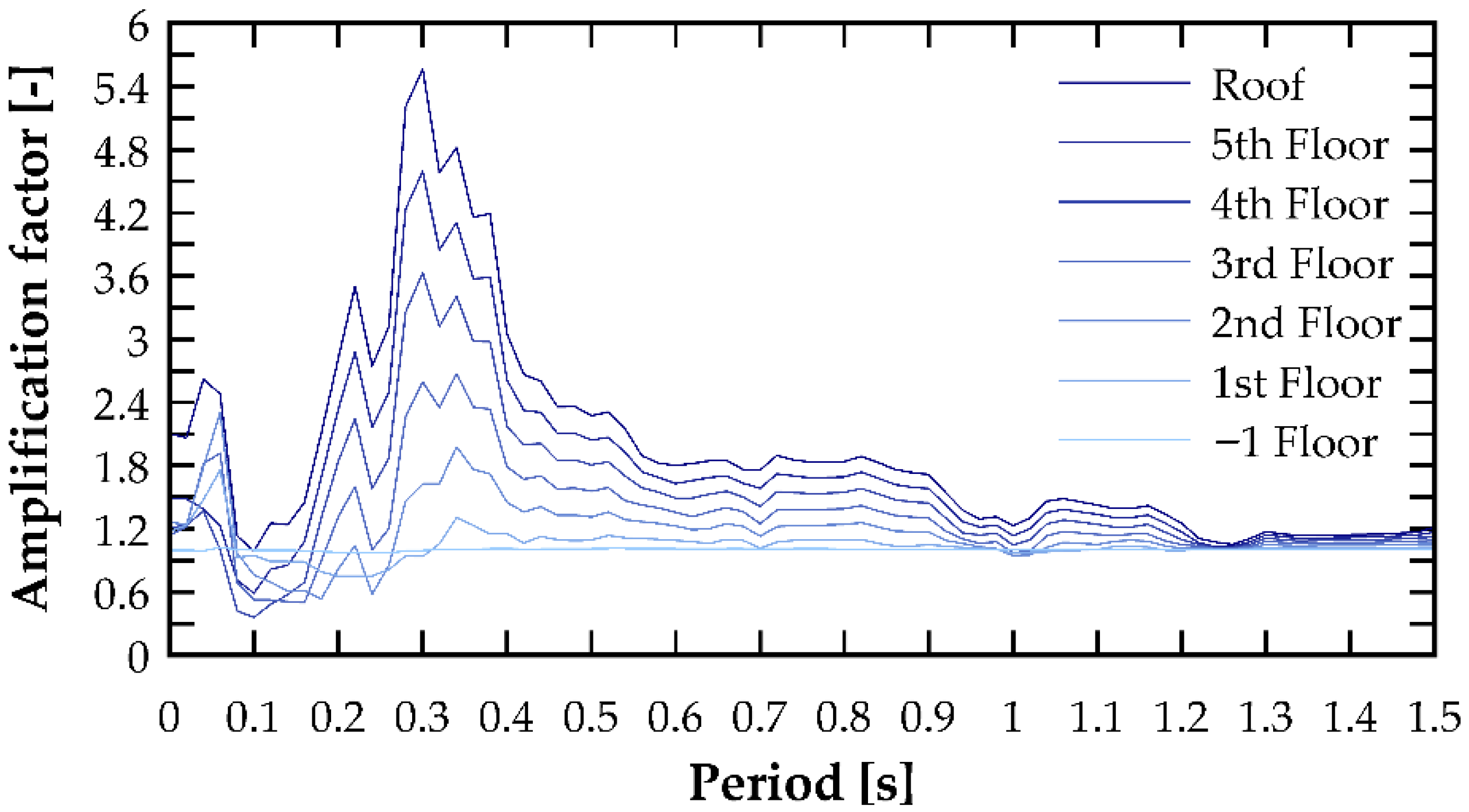

The results of the amplification factor obtained for the Coquimbo earthquake record are shown in

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15. These figures clearly indicate that the amplification factor is period-sensitive, reaching pronounced peaks around specific periods corresponding to approximately twice the fundamental vibration periods in the analyzed directions. The figures also show that for very short periods (below 0.1 s), accelerations experience moderate amplifications, in some cases approaching a value of 2.5, followed by a sharp reduction that even exhibits de-amplifications. Similarly, it can be observed that for long periods (above 1 s), the acceleration amplification tends to stabilize around unity. The resulting amplification spectra provide a refined characterization of floor acceleration demands along the building height and constitute a basis for improving the estimation of seismic forces acting on NSCs.

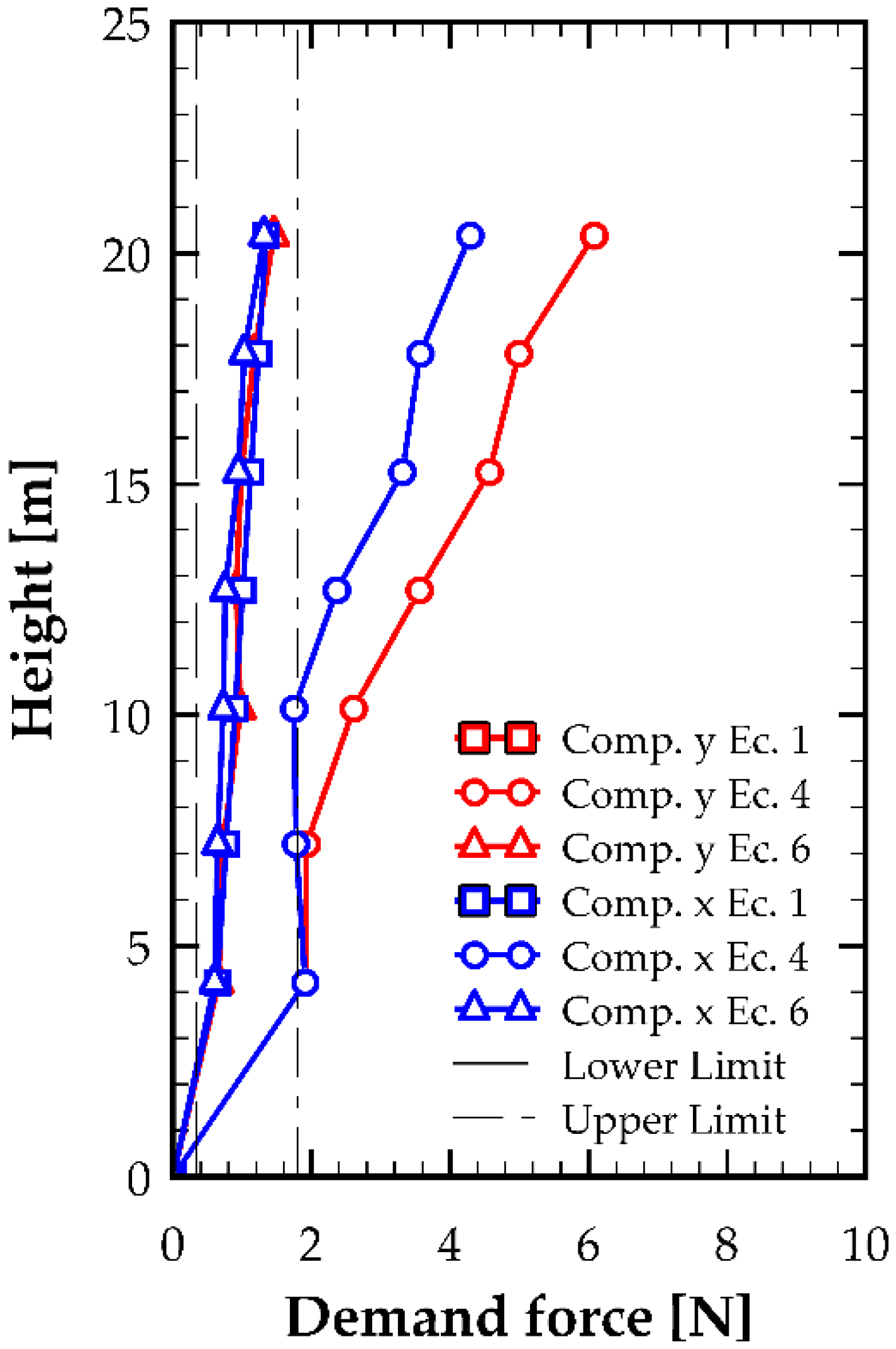

Once the acceleration time histories and the spectral modal acceleration for each floor were obtained, the seismic demand (

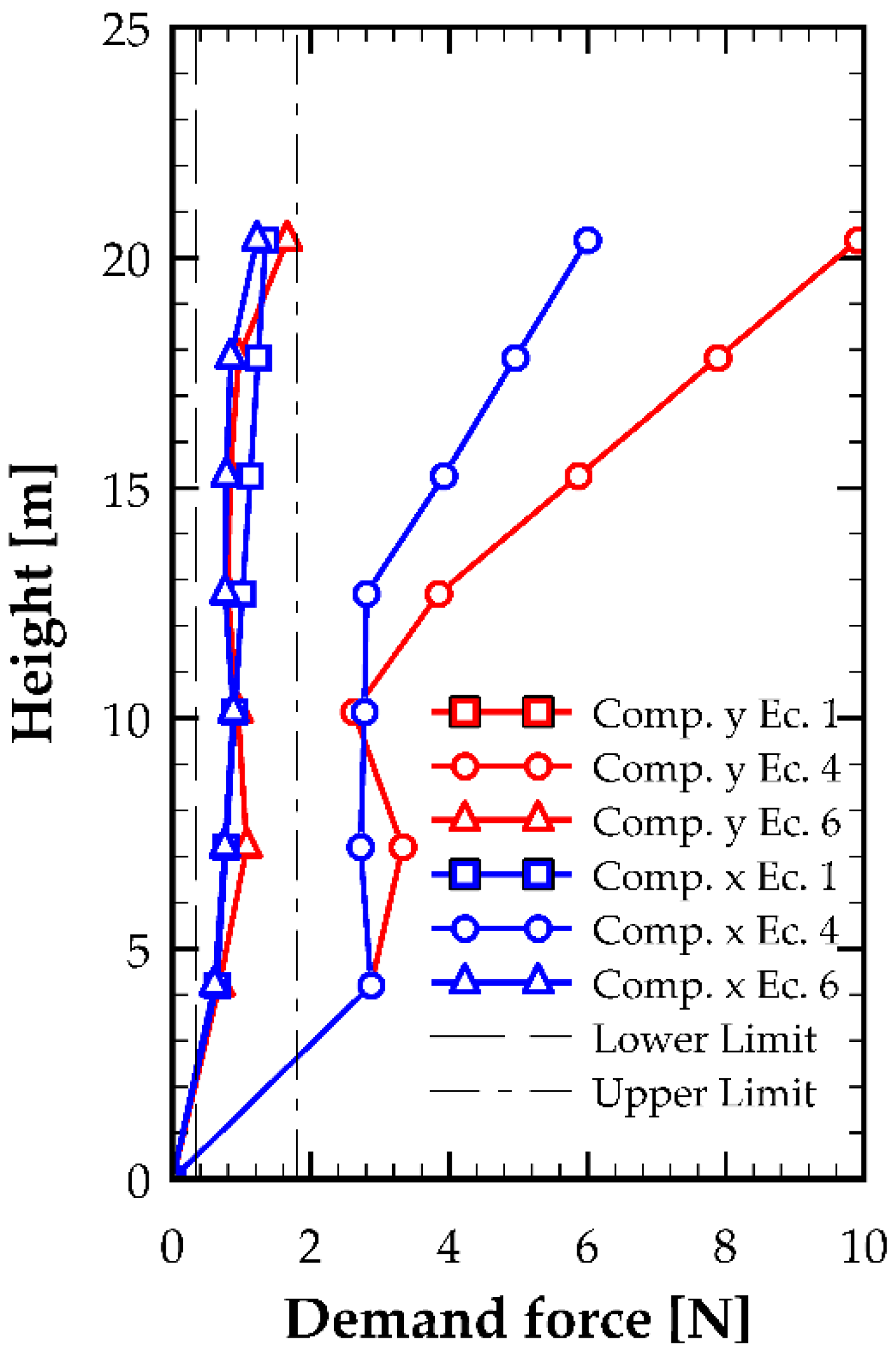

for the NSCs was defined according to the recommendations of NTM 001, as shown in

Figure 16 and

Figure 17, using Equations (1) and (6). Likewise, the graphs include the upper and lower bounds defined in Equations (2) and (3), respectively.

In terms of floor accelerations, a consistent characteristic can be observed throughout the study: a peak in spectral pseudo-acceleration around the fundamental period, as shown in

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 for the remaining excitations. This information becomes more relevant when taking the ratio with the pseudo-acceleration of the accelerogram, as illustrated in

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15. These figures provide a design spectrum indicating that around the first fundamental period, acceleration amplifications occur, whereas around the second fundamental period, smaller amplifications—or even de-amplifications—are obtained.

5. Discussion

The current main approach to designing NSCs is to estimate the maximum floor acceleration, which has led to the development of various simplified methodologies as alternatives to nonlinear time history analysis. Among these are the concept of transient inelastic vibration modes proposed by [

40], and the approach based on empirical modal reduction factors proposed by [

41] for RC walls and steel moment-resisting frames (MRFs). Both methods were tested by [

42], yielding satisfactory results. Another alternative under development is the estimation of maximum floor acceleration through deformation limits or performance levels of the supporting structure, as proposed by [

43].

As observed, there is no doubt that acceleration amplification occurs, with height being one of the contributing factors to this amplification. As demonstrated, greater heights result in increased maximum absolute floor accelerations, regardless of the seismic excitation applied. It should be noted, however, that although the maximum absolute acceleration is generally greater for an upper floor compared to the one immediately below, the opposite may also occur, as demonstrated by the results obtained.

The influence of the degree of nonlinearity, which primarily affected the lower floors of the supporting structure, on the maximum absolute floor acceleration is not the same for the upper floors as for the lower ones. It was observed that, regardless of the seismic excitation applied, the amplification factor—that is, the PFA/PGA ratio—is essentially equal to unity, meaning that the maximum floor acceleration is, in essence, the same as the peak ground acceleration for the lower floors. This becomes clearer when analyzing the floor pseudo-acceleration spectra normalized by the pseudo-acceleration of the accelerogram, where a nearly horizontal line equal to unity can be observed.

It is well known that a practical way to estimate the demand on NSCs is through the FRS spectrum. For all cases, it can be seen that the FRS are qualitatively similar to each other (for the same excitation), but exhibit appreciable quantitative differences in the ordinates depending on the floor considered, with the largest values occurring in the upper stories.

From a practical standpoint, NSCs will be subjected to acceleration amplification when their period coincides with one of the modal periods of the structure. Conversely, if their period does not coincide, amplification will still occur, though to a lesser extent compared to the case in which it matches the fundamental period, for instance. From this, it follows that the properties of NSCs have a direct relationship with the dynamic properties of the supporting structure.

6. Conclusions

The results obtained allow several relevant observations to be made regarding the behavior of seismic demand on NSCs in shear wall buildings. It was observed that the floor response spectra (FRS) at the lower levels, particularly at floor −1 (located at 20% of the total building height), exhibit a shape similar to the base accelerogram response spectrum. This suggests that, at these levels, the demand is primarily governed by the characteristics of the seismic excitation, in contrast to the upper levels, where the FRS mainly reflects the dynamic properties of the supporting structure.

The analyses carried out in this study demonstrated that maximum floor accelerations in RC shear wall buildings exhibit a clear amplification trend with increasing height, reaching their peak values near the fundamental vibration period of the structure. For the examined building, representative of mid-rise Chilean residential typologies, the computed amplification factors (PFA/PGA) ranged between 1.0 and 3.5, depending on the direction of excitation and floor level. These results confirm that local dynamic properties strongly influence the vertical distribution of acceleration demands and highlight the need for explicit consideration of such effects in the design of acceleration-sensitive NSCs.

The findings of this study indicate that the Chilean Technical Standard MINVU NTM 001 provides an adequate and reliable framework for estimating seismic demand on NSCs, with the simplified formulation of Equation (1) yielding results that fall within the code’s prescribed bounds and showing good agreement with time history analyses. However, response spectrum analysis tends to overestimate demands—particularly at upper stories—due to its limited ability to capture dynamic amplification effects, suggesting that method selection should be approached with caution. From a design standpoint, the results confirm that maximum NSC acceleration amplification typically occurs near the fundamental period of the structure; therefore, NSCs should ideally be designed with natural periods exceeding the building’s fundamental period, or, when this is not feasible, located at floors with lower modal participation to reduce their expected seismic demand. It should be noted that the conclusions presented here are valid within the context of the assumptions and characteristics of the analyzed case study, which corresponds to a representative mid-rise Chilean RC shear wall building. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as indicative of typical acceleration patterns rather than as universally applicable values. As demonstrated, the floor response spectra (FRS) depend not only on the dynamic properties of the structure but also on the frequency content and intensity of the seismic excitation. Consequently, generalization to other structural typologies should be approached with caution. Future research will extend this work by incorporating buildings of different heights, aspect ratios, and plan configurations to evaluate the influence of these parameters on the amplification of acceleration demands. Additionally, it is recommended to include the explicit modeling of NSCs to assess their interaction with the supporting structure and to explore the effects of nonlinear behavior across broader deformation ranges. These efforts will contribute to establishing parametric relationships useful for refining the provisions of the Chilean Technical Standard NTM 001 and improving the seismic design of acceleration-sensitive components.