Abstract

Scaffolds, as temporary structural support systems in civil engineering, play an essential role during construction. Independent steel scaffold systems, typically composed of assembled steel tubes, can be erected and function as standalone supports without mutual interference. This feature offers notable advantages over conventional scaffolding, including easier dismantling and higher reusability efficiency. However, the absence of specific design and construction codes for this type of scaffolding has hindered its broader application, underscoring the need for further research into its structural reliability. This study investigates the stability of basic load-bearing units in independent scaffolding through vertical loading tests on three specimens with varying heights and end conditions. The failure modes of the specimens are systematically compared, and the load-transfer mechanism and mechanical behavior of the scaffold units are analyzed. Experimental results, validated against ABAQUS finite element simulations, reveal that the critical region under axial compression lies at the junction between the inner and outer tubes. As specimen height increases, a plastic hinge develops in this region under load. In shorter specimens, the inner and outer tubes interact in a nearly fixed-end condition, without failure of the connecting pins. All three specimens failed by instability, and reducing the specimen height significantly enhanced the load-bearing capacity. When the top of the specimen is pin-supported, the material’s compressive strength is not fully utilized. To improve the axial stability of independent scaffolding, several structural improvements are proposed: replacing the pinned top with a plate-supported end to enhance compressive stability; integrating transverse bracing at the ends to connect individual units into an integrated system, thereby improving overall stability without compromising spatial flexibility; and applying mechanical reinforcement with external collars at the inner–outer tube interface to increase local bending stiffness and reduce initial imperfection, thus strengthening the global buckling resistance of the independent scaffolding system.

1. Introduction

In civil engineering construction, scaffold structures serve as temporary support systems, fulfilling the critical functions of concrete formwork support and the erection of working platforms for construction operations. In practice, instability of scaffold structures is often triggered by loosening of member connections or local buckling, which can lead to progressive collapse. Such instability may cause the failure of newly cast concrete elements, resulting not only in significant economic losses but also posing serious threats to the safety of construction personnel. Therefore, to ensure the stability of cast-in-place concrete structures during construction, in-depth research into the mechanical response and failure modes of scaffold support systems is of considerable engineering significance.

In recent years, researchers have proposed various structural forms of scaffolding. Systems commonly used in current engineering practice include coupler-type, cup-lock-type, and plug-and-play disk-lock-type support systems. The academic community continues to focus on key factors affecting the buckling stability performance of scaffolds, such as material constitutive relationships [1,2], initial geometric imperfections [3,4], joint mechanical behavior [5,6,7], and construction process characteristics [8]. Traditional scaffold systems typically require dense arrangements of horizontal and diagonal bracings at the middle and bottom sections of uprights to form spatially rigid connections. However, such systems offer limited internal working space, which hinders the execution of other construction trades during concrete curing. Moreover, the dense arrangement of members not only increases material consumption but also introduces numerous connection joints, leading to increased construction complexity and project costs.

The independent scaffold support system uses a single composite steel tube as the basic load-bearing unit, featuring independent installation and load-carrying capabilities. This grants it significant advantages in terms of ease of assembly/disassembly and spatial efficiency. However, it should be noted that the elimination of horizontal and diagonal bracing significantly increases the effective length of compression uprights, consequently markedly reducing their buckling stability capacity. Thus, conducting accurate buckling stability analysis becomes a critical issue in the design of such independent support systems.

In response to the aforementioned issues, numerous scholars have conducted relevant research. Chen et al. [9] pointed out that local buckling of steel tube sections leads to rapid degradation of their bending capacity, with this effect becoming more pronounced as the diameter-to-thickness ratio increases. When the diameter-to-thickness ratio is 250, the section cannot achieve the full plastic moment; whereas with ratios between 36 and 50, the section can still attain the full plastic moment. Studies by Jiao et al. [10] and Martin et al. [11] indicated that high-strength circular steel tubes with large diameter-to-thickness ratios are prone to local buckling failure, and adding internal constraints can effectively enhance their ultimate bearing capacity. Huang Bingsheng et al. [12] found that reinforcing axially compressed circular steel tubes with sleeves significantly improves member stiffness, yield load-bearing capacity, and stability capacity. Hu Changming et al. [13] systematically analyzed the stability capacity correction factors for coupler-type steel tube formwork supports. Regarding upright stability, Zhang Zhichao et al. [14] conducted axial compression tests and parametric analysis on sleeve-spliced uprights, noting that initial imperfections significantly affect the stability capacity of spliced uprights.

Research by Bjorhovde [15] and Jones [16] showed that most beam-column connections in steel frames actually exhibit semi-rigid behavior. Idealizing them as perfectly rigid or pinned connections can lead to deviations in calculated buckling loads. Zheng et al. [17] also emphasized that scaffold support systems are essentially spatial steel frames with semi-rigid characteristics. Numerous scholars have investigated the mechanical performance of such systems considering semi-rigid connections [18,19,20,21,22]. Zhang et al. [23] employed three different second-order inelastic analysis methods to design typical semi-rigid scaffold cases, aiming to develop systematic design methods based on second-order inelastic analysis. Chandrangsu et al. [24] proposed modeling approaches accounting for sleeve connections, semi-rigid vertical beam connections, and base plate eccentricity, incorporating material nonlinearity using the Ramberg–Osgood model. Furthermore, focusing on joint stiffness parameters, existing research has developed numerical simulation methods for estimating the critical buckling load of scaffolding systems [17,25,26].

This study investigates the ultimate bearing capacity and failure modes of independent steel support scaffolds under axial compression through experimental tests and finite element simulations using ABAQUS, analyzing members with varying heights and end constraints. Its primary innovation lies in developing a modified Shanley theoretical model that incorporates, for the first time, variable hinge height and initial curvature. By introducing quantitative parameters for hinge position and initial imperfections, the proposed model overcomes the limitations of traditional theories in characterizing non-ideal connections in scaffold joints. It more accurately captures the effects of inner–outer tube clearance and geometric defects on stability, establishing a new theoretical framework for temporary support systems. This advancement not only refines stability analysis for independent scaffolding but also provides valuable insights for the mechanical design of similar adjustable structures, supported further by parametric studies that explore key factors influencing ultimate capacity.

2. Test Preparation

2.1. Test Device

2.1.1. Composition of Independent Supporting Scaffolding

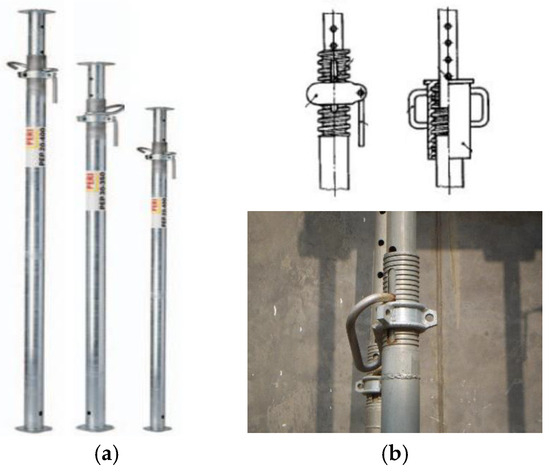

The independent steel support scaffolding consists of two parts: the vertical pole and the end support. Figure 1 shows the independent steel support scaffolding specimen. Among them, the independent steel support scaffolding pole is composed of two inner and outer casings. The first casing is the outer pipe of the pole, Φ60 × 3.0 high-frequency welded pipe with a height of 1660 mm; the second casing is the inner pipe of the pole, Φ48 × 3.0 high-frequency welded pipe with a height of 2040 mm. There is a threaded casing made of Q235 welded on the first casing, which is used in conjunction with the fine-tuning nut to make the adjustment range 0~100 mm. The second casing has pin holes with a diameter of Φ18 distributed every 100 mm. The independent adjustment is performed by inserting steel pins. Support scaffolding height. The end supports at both ends of the independent support scaffolding are 5 mm-thick Q235 steel plates, and the size of the vertical pole head is Φ60 × 3.0. The adjustable height range of the independent support scaffolding is 1.9~3.5 m, and the fine-tuning accuracy is 1 mm.

Figure 1.

Specimen structure: (a) test piece; (b) length adjuster.

2.1.2. Test Specimen

The specimen specifications used in this test are: inner tube Φ48 × 3.0, outer tube Φ60 × 3.0, pin hole Φ18, pin Φ16, all materials are Q235. The average values of the mechanical properties for the steel used are as follows: tensile strength 329.59 MPa, yield strength 263.95 MPa, elastic modulus 181.74 GPa, and Poisson’s ratio 0.31. The outer tube height is 1600 mm, but two different inner tube insertion heights of 200 mm and 930 mm are used, and the specimen heights are 2770 mm and 3500 mm, respectively.

The specimens are designated as follows: DLZ-1 represents a 3500 mm high scaffold with a pinned upper end; DLZ-2 denotes a 3500 mm high scaffold with a plate-supported upper end; and DLZ-3 corresponds to a 2770 mm high scaffold also with a plate-supported upper end. Detailed parameters of each specimen are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Dimensions of each specimen in mm.

2.2. Loading Device Subsection

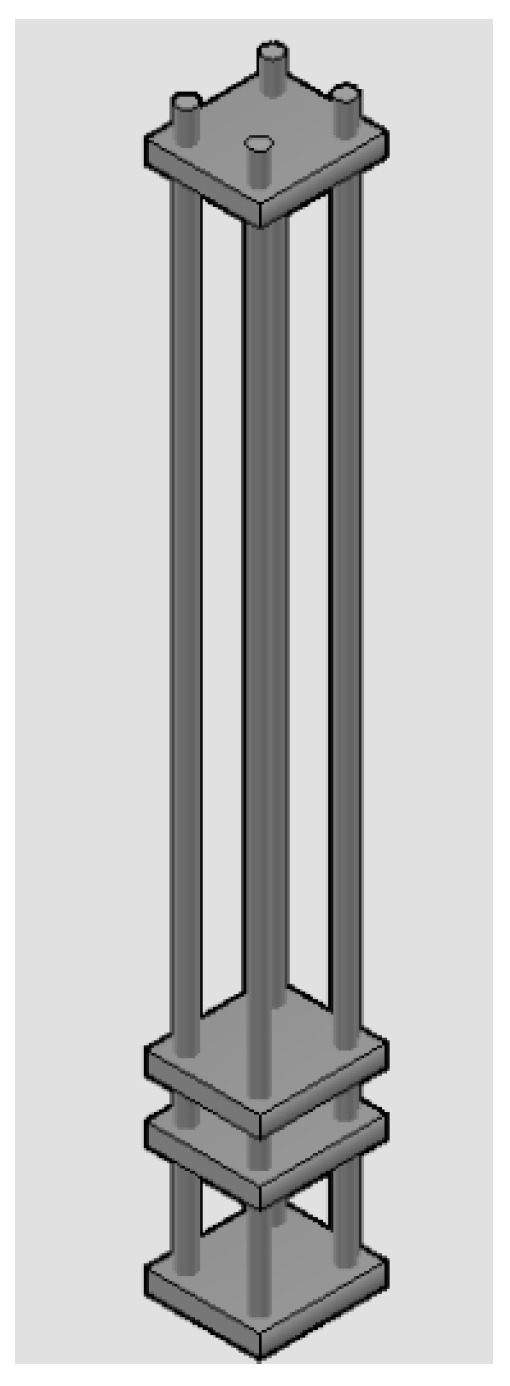

The loading device is shown in Figure 2. Assume that the test load is N and the tension of each tension round bar is N/4. According to the “Steel Structure Design Standard” (GB50017-2017) [27], the tensile strength design value of the corresponding steel grade is found, and the required tension circle is designed. Rod diameter.

Figure 2.

Loading device.

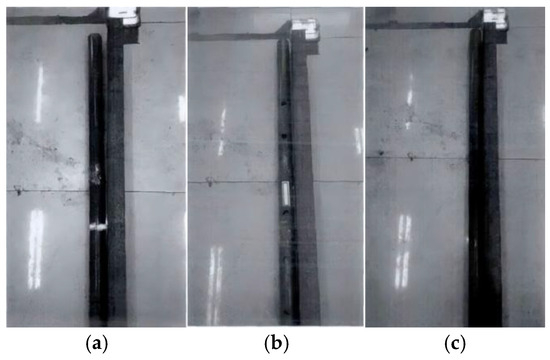

This test loading device uses four tensioned round rods with a diameter of Φ25 mm and a length of 5000 mm, and their ends are threaded. The cross-section size of the middle steel plate is 350 mm × 350 mm, and the thickness is 25 mm. The cross-section size of the end steel plate is 200 mm × 200 mm, and the thickness is 25 mm. The material is Q235. During the test, the upper end of the specimen approximated a plastic hinge. In order to further understand the instability load and failure mode of independent steel support scaffolding under different upper connection methods, a test ball hinge device with hinged ends was designed for this experiment. This device consists of a hemisphere with a diameter of 100 mm and a 25 mm thick steel plate. Holes and slots are drilled at the corresponding positions of the steel plate and connected by bolts, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Spherical hinge device.

3. Test

3.1. Test Methods

In this test, a self-balancing loading device was used to achieve static loading of the independent support scaffold through the static force provided by the hydraulic jack, and a pressure sensor was used to control the loading force. Strain gauges are attached to the scaffolding rods in parallel directions, and five strain gauges are arranged at both ends of the upper and lower rods and at the midpoint of the entire rod. By measuring the compressive resistance strain value of the strain gauges, to measure the compressive strain of the rod. Two mutually orthogonal displacement sensors are arranged at both ends and the midpoint of the entire rod to measure the lateral deflection of the rod. The maximum deflection is obtained by combining the data of the two sensors. By comparing the yield conditions of the scaffold under different working conditions and combining with theoretical calculations, graded loading was carried out.

3.2. Test Phenomena

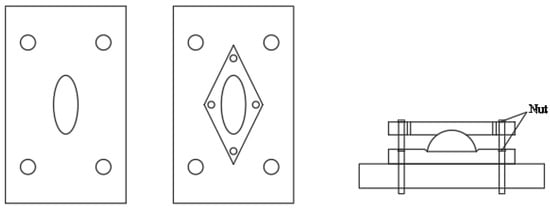

During the initial loading stages, the strain and deflection at the measuring points increased gradually in all specimens. For DLZ-1, significant deformation at the inner and outer tube nodes became visually apparent at the fourth load level, accompanied by pronounced lateral deformation. The specimen ultimately failed completely under the sixth load level. Post-test examination revealed that the inner tube buckled first, with the maximum bending occurring along its length, while the pin remained undamaged.

In the case of DLZ-2, noticeable deformation at the inner and outer tube joints occurred at the sixth load level. With further loading, the deformation rate accelerated rapidly. The specimen reached complete failure at the ninth load level. After testing, it was observed that the inner tube initially buckled at the junction between the inner and outer tubes, and the maximum bending was located at the tip of the inner tube; the pin again sustained no damage.

For DLZ-3, deformation became clearly evident by the seventh load level. The specimen experienced instability failure at the tenth load level. The maximum bending was identified at the junction of the inner and outer tubes; however, no localized damage was observed in that region. The damage and deformation conditions of DLZ-1, DLZ-2, and DLZ-3 are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Failure form of test piece: (a) The inner and outer tubes of DLZ-1 are damaged; (b) The inner and outer tubes of DLZ-2 are damaged; (c) The inner and outer tubes of DLZ-3 are damaged.

4. Result Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Load-Strain Curve Analysis

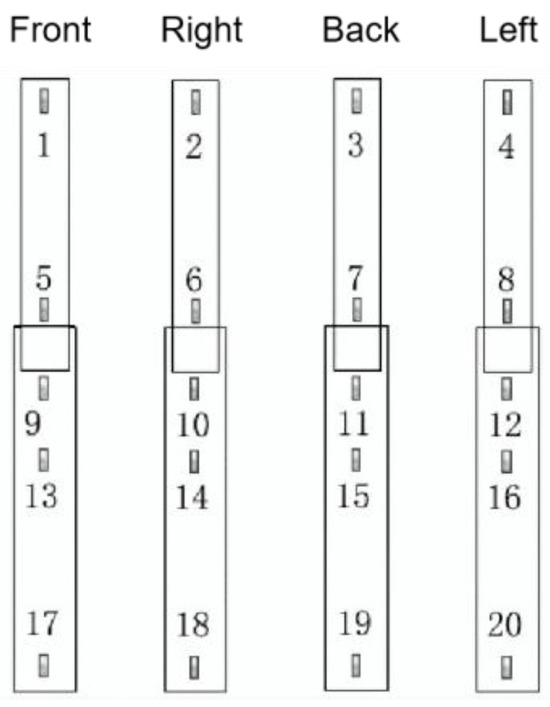

This test was loaded by a hydraulic jack, and the pressure sensor controlled the loading force. The compressive strain parallel to the direction of the specimen is measured through resistance strain gauges arranged at five cross-sections at the ends and midpoints of the inner and outer tubes and the midpoint of the entire specimen. Figure 5 shows the strain gauge arrangement of DLZ-1, DLZ-2, and DLZ-3. Measurement points 1 to 20 are arranged on each specimen. The load-strain change relationship is shown in Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Figure 5.

DLZ-1, DLZ-2, and DLZ-3 strain measuring points.

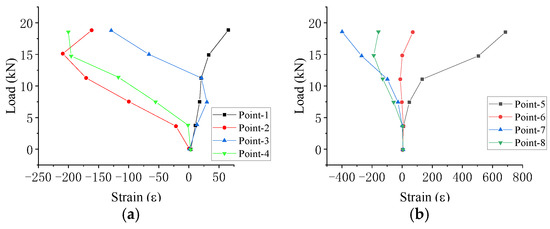

Figure 6.

DLZ-1 load-strain curve: (a) point 1–4; (b) point 5–8; (c) point 9–12; (d) point 13–16; (e) points 17–20.

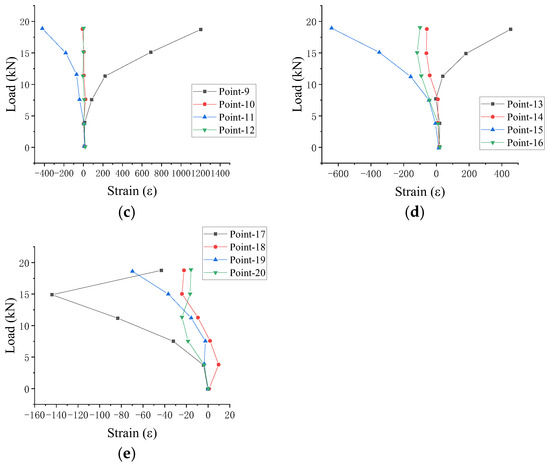

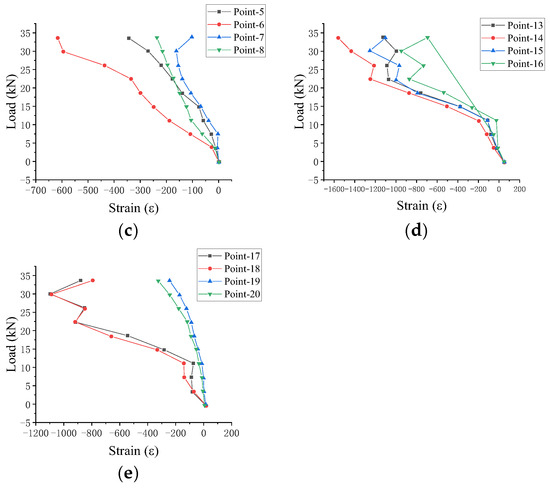

Figure 7.

DLZ-2 load strain curve: (a) point 1–4; (b) point 5–8; (c) point 9–12; (d) point 13–16; (e) point 17–20.

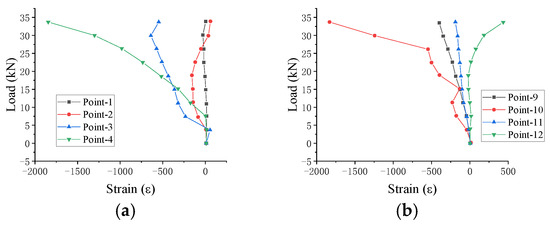

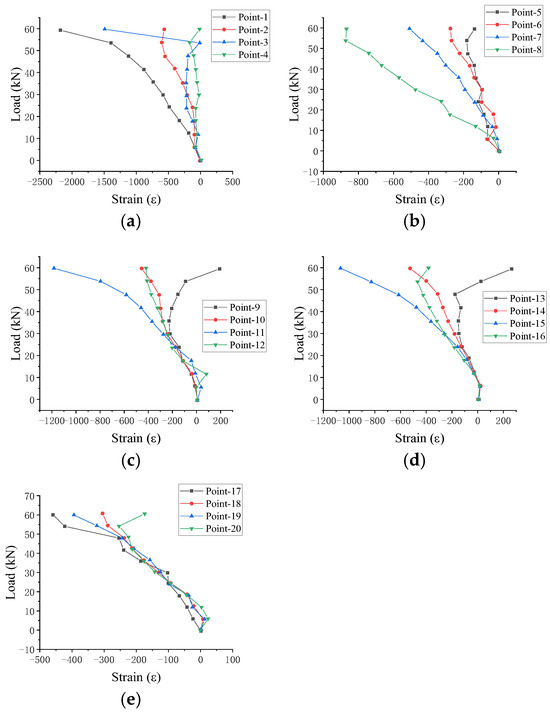

Figure 8.

DLZ-3 load strain curve: (a) point 1–4; (b) point 5–8; (c) point 9–12; (d) point 13–16; (e) point 17–20.

It can be found from the load-strain curve of specimen DLZ-1 in Figure 6:

- (1)

- During initial loading, stresses and strains increased progressively at all measuring points. The presence of initial gaps between components initially induced bending deformation, followed by hinged-end rotation upon further loading, resulting in combined tensile and compressive behavior in the specimen.

- (2)

- As loading continued, the load–strain relationship remained largely linear. Due to the random rotation of the spherical hinge, Measuring Point 3 exhibited a clear tension-to-compression transition, indicating variable force distribution at the hinged end. In contrast, the outer tube at the specimen base experienced predominantly linear compression, owing to its higher bending stiffness and stable contact. Strain comparisons revealed a significantly greater increase in the inner tube, suggesting that the weak regions of the scaffold system extend beyond the inner–outer tube nodes to include the inner tube itself.

- (3)

- During later loading stages, the load–strain curves demonstrated near-uniform linearity. A pronounced slope change occurred in the tension zone at the inner–outer tube junction, where stiffness substantially exceeded that in compression, while other areas remained below yield. The inner tube’s deformation at this location markedly surpassed that of the outer tube, undermining structural integrity. Inner tube failure is thus identified as the primary cause of the specimen’s loss of bearing capacity.

Based on the load–strain curve of specimen DLZ-2 (Figure 7), the following behavior was observed:

During initial loading, stress and strain increased progressively at all measuring points. The upper end exhibited relatively stable strain, attributable to a transition from hinged to plate restraint, which improved overall structural stability.

- (1)

- With increasing load, the load–strain relationship remained approximately linear. Due to initial bending and the gap between inner and outer tubes, strain trends diverged between the upper and lower ends. The connection at the inner–outer tube junction behaved intermediately—neither as a plastic hinge nor as a fully fixed connection—while DLZ-2, with its modified upper restraint, demonstrated significantly higher bearing capacity than DLZ-1.

- (2)

- In later loading stages, the load–strain response continued linearly. As loading progressed, the joint between the inner and outer tubes increasingly resembled a plastic hinge, rotating about the bolt axis.

Based on the load–strain curve of specimen DLZ-3 (Figure 8), the mechanical behavior can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- In the initial loading phase, stress and strain increased gradually at all measuring points, with relatively stable strain throughout the specimen, indicating minimal initial bending.

- (2)

- As loading progressed, the load–strain relationship remained largely linear. Strain increments were closer to those in DLZ-1 and DLZ-2, indicating that the reduced specimen length effectively minimized initial bending and enabled the steel to utilize its full compressive capacity. With decreased specimen height and increased inner–outer tube contact length, the joint behavior approached that of a pin-supported fixed connection.

- (3)

- During the later loading stage, the load–strain curve maintained near-uniform linearity. Compared to DLZ-1 and DLZ-2, DLZ-3 exhibited significantly improved compressive stability.

4.2. Load–Deflection Curve Analysis

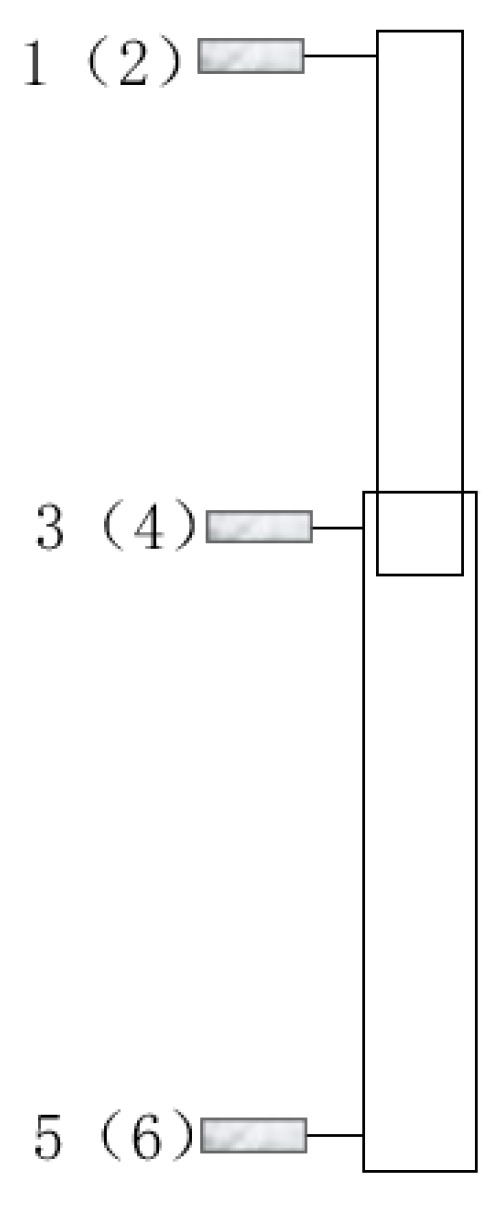

To measure the lateral deflection of the specimens during loading, displacement gauges 1–6 were installed at both ends of the specimens and at the junctions of the inner and outer tubes. Among them, three displacement gauges were arranged vertically from top to bottom in each of the two vertical directions, as shown in Figure 9. The load–load-displacement curves of the three specimens are presented in Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12.

Figure 9.

Measuring point arrangement 1–6.

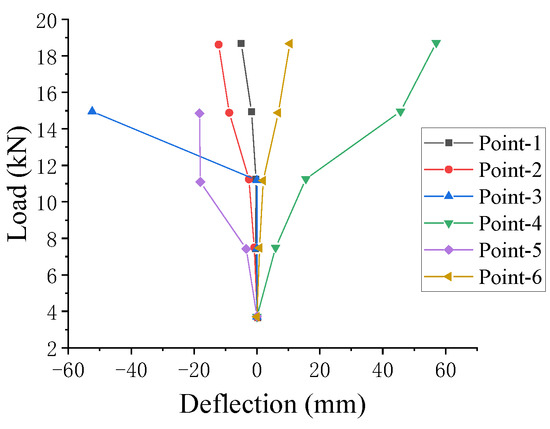

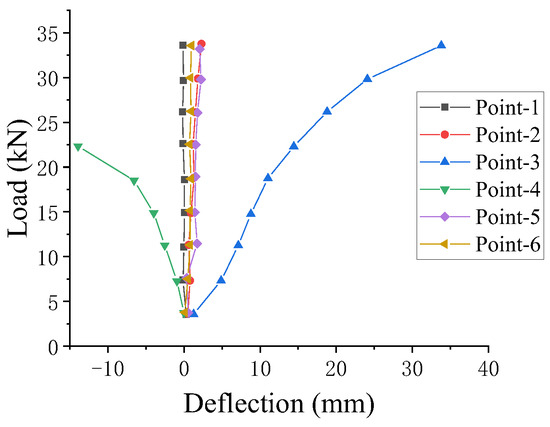

Figure 10.

DLZ-1 load displacement curve.

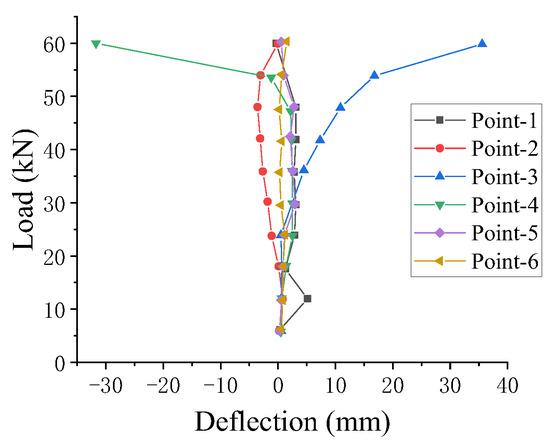

Figure 11.

DLZ-2 load displacement curve.

Figure 12.

DLZ-3 load displacement curve.

Based on the load–deflection curve of specimen DLZ-1 (Figure 10), its mechanical behavior evolved in three stages. Initially, deflection increased gradually at all points, with the maximum displacement at the inner–outer tube junction due to bending induced by the tubular gap. As loading progressed, the load–deflection response remained nearly linear, while the combined effect of the upper hinged connection and the tube junction hinging caused noticeable lateral distortion. In the final stage, a quasi-plastic hinge developed at the junction; its increasing prominence under continued loading ultimately led to instability failure at this location.

Based on the load–deflection response of specimen DLZ-2 (Figure 11), the structural behavior evolved as follows: during initial loading, negligible deflection occurred at the specimen ends due to enhanced lateral restraint from increasing frictional resistance with the steel plate, while clearance between the inner and outer tubes induced initial flexural deformation, concentrating displacement at their junction; with further loading, the ends remained nearly rigid, but a plastic hinge-like mechanism developed at the tube junction, with the plate restraint significantly improving compressive stability; in the advanced stage, rotation at the hinge became increasingly dominant, ultimately leading to buckling failure at that location.

The load–deflection behavior of specimen DLZ-3 (Figure 12) evolved as follows: during initial loading, deflections were minimal at all points, with the largest displacement occurring at the inner–outer tube junction due to the reduced specimen height and diminished influence of interconnection and initial imperfections; under continued loading, deflections remained generally stable, and the peak consistently localized at the tube junction, highlighting the role of specimen height in mitigating sensitivity to initial bending; in the later stage, the curve slope increased progressively until instability failure occurred, with DLZ-3 exhibiting substantially improved compressive stability over DLZ-2 and enabling full utilization of the steel’s compressive strength.

Through the above tests, the force transmission mechanism and force characteristics of the independent support scaffolding were clarified. Through the analysis of test phenomena and test results, it can be found that the weak point of the specimen is at the intersection of the inner and outer tubes, and as the load increases, the intersection of the inner and outer tubes evolves into a plastic hinge failure mode. Due to the high slenderness ratio design, all three specimens exhibited instability failure modes. Furthermore, it was observed that enhanced end restraints significantly improved the load-bearing capacity of the specimens.

5. Theoretical Calculation and Finite Element Model

The computational methodology for independently supported steel tube scaffolding has not yet been fully established. However, given its notable similarity to the Shanley model, this study adopts an improved Shanley model as the theoretical framework, which is subsequently validated through experimental testing and finite element analysis.

The elastic critical buckling load of an ideal axial compression bar is:

In the formula: Pcr is the critical buckling load (N)

E is the elastic modulus (N/mm2)

μ is calculated coefficients for length

Average stress in the member section:

In the formula: is the critical stress (N/mm2)

is the cross-sectional area of the member (mm2)

is the slenderness ratio of the member.

The above two formulas are the calculation formulas for the elastic critical buckling load and critical stress of the ideal axial compression bar. After the stress exceeds the steel stress proportion limit, the specimen will yield in the elastic-plastic stage, and this formula is no longer applicable.

5.1. Effect of Initial Bending on Axial Compression Specimens

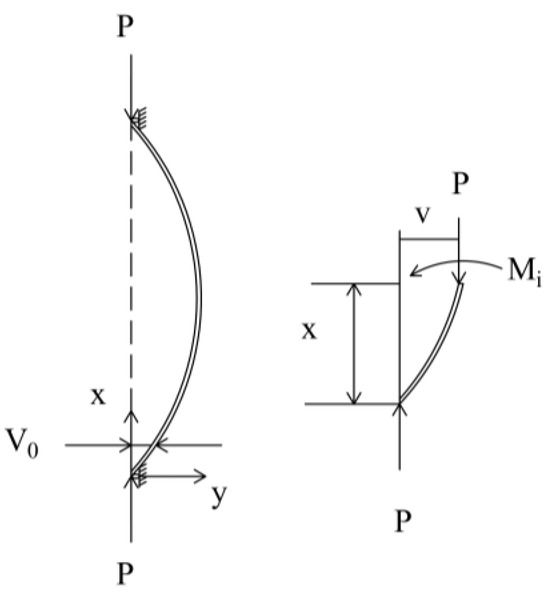

In the theoretical calculation model, the specimen is in an ideal upright state, and the specimen is also subjected to axial force. However, in actual engineering, the specimen does not exist in such an ideal state. Therefore, as shown in Figure 13, we need to consider the actual effects, such as initial bending defects in the specimen and eccentricity in the axial force. This test assumes that the initial eccentricity does not exist and only studies the impact of initial bending on the specimen.

Figure 13.

Initial bending of specimen.

5.2. Improvement of Shanley Model

The Shanley theoretical model primarily consists of two absolutely rigid segments connected by a central hinge. This hinge comprises two short deformable elements, each with a length and spacing of h, and a cross-sectional area of A/2. For variable-length independently supported scaffolding, the hinge location is variable, and clearances exist between the inner and outer tubes, as well as between the pins and pinholes. Consequently, the computational model under investigation differs from the classical Shanley model, necessitating modifications in terms of variable hinge height and initial curvature.

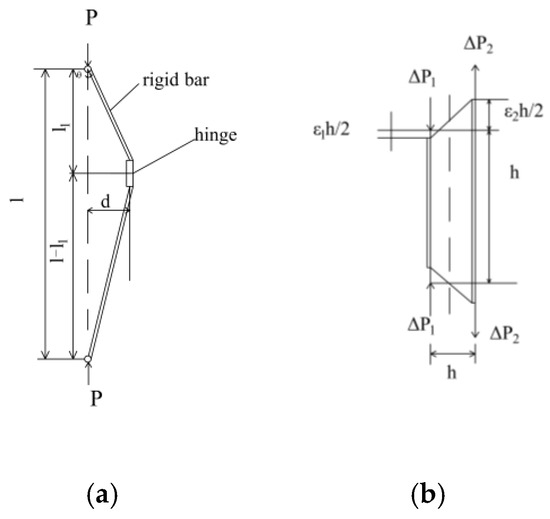

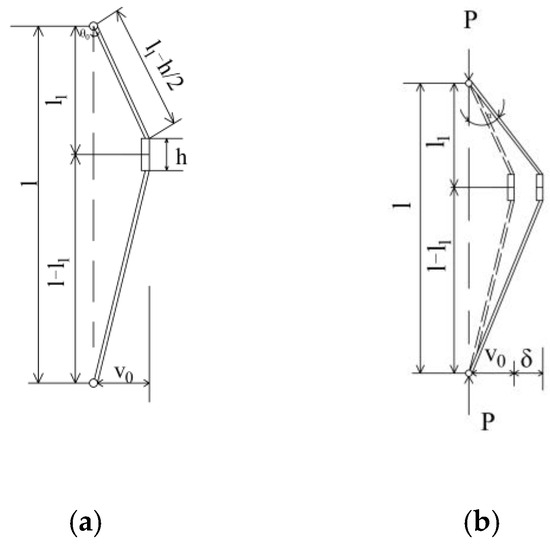

5.2.1. Model Variable Hinge Height Improvement

As illustrated in Figure 14a, two rigid bars with lengths l1 (upper) and l − l1 (lower) are connected by an elastoplastic hinge with an elastic modulus of E and a tangent modulus of Et. The hinge consists of two short limb elements of length h, as shown in Figure 14b, each with a cross-sectional area of A/2, where A corresponds to the cross-sectional area of the upper bar. Under axial compressive force P, all elastoplastic deformations of the specimen are concentrated within these short limb elements, while the remaining components align with the assumptions of the Shanley theoretical model.

Figure 14.

Schematic of the modified Shanley mechanical model with variable hinge height: (a) General Simplified Model; (b) Simplified Hinge Model.

When the load P reaches the critical state of the specimen, bending initiates. At this stage, the strains induced by bending in the left and right limbs of the hinge are ε1 and ε2, respectively. The deflection of the specimen is denoted as d, and the inclination angle at the top of the upper bar is θ. The geometric relationships among these parameters are given by:

Thus,

The external bending moment Me acting on the cross-section at the hinge is given by:

As illustrated in Figure 14b, the internal moment Mi can be expressed as

Given that the elastic moduli on the concave and convex sides of the bending moment are E1 and E2, respectively, the Mi is derived as follows:

From the equilibrium condition Me = Mi, the following relation can be derived:

When the specimen is in an elastic state, E1 = E2 = E, the elastic buckling load is

When the specimen buckles in the elastoplastic state and the tangent modulus theory is applied, E1 = E2 = E, the tangent modulus buckling load is obtained as:

When the specimen is in an elastic-plastic state and the dual-modulus theory is adopted, the dual-modulus buckling load is:

By setting , the following expression can be derived:

After comparison, it can be seen that , therefore

5.2.2. Model Initial Bending Improvement

There are gaps between the inner and outer tubes of the specimen and between the pins and the jacks, so the initial state of the specimen must be in the initial bending state. In order to facilitate theoretical analysis, as shown in Figure 15, The Initial deflection of the specimen is , and the angle between the upper rigid rod and the ideal axis is θ0.

Figure 15.

The Shanley theoretical model with an initial bending moment: (a) Zero-load state; (b) Loaded state.

Under zero load conditions, the specimen maintains an initially curved configuration free of strain. Upon loading, a finite deflection develops at the midspan of the specimen. The rigid bars after deformation form an angle with the ideal axis, as shown in Figure 15b. During bending, all deformations are concentrated in the two deformable elements at the central hinge, inducing longitudinal strains ε1 and ε2 in these elements, which result from changes in the axial force during bending. The corresponding relationships are expressed as follows:

Thus, the external bending moment Me and the internal resisting moment Mi at the hinge of the model can be, respectively, expressed as follows:

Given the small magnitudes of and , a simplifying assumption is made by setting . Here, and represent the variations in axial force within the two deformable elements at the central hinge due to the applied load, and they also correspond to the total axial forces. The terms E1 and E2 denote the elastic moduli of the deformable elements on the concave and convex sides of the model column, respectively.

From the equilibrium conditions we can obtain:

The buckling load considering the initial bending can be found as:

When the specimen is in the elastic state, the elastic buckling load is:

When the specimen is in the elastic-plastic state, the tangent modulus buckling load:

When the specimen is in an elastic-plastic state and the dual-modulus theory is adopted, the dual-modulus buckling load is:

In the formula: is the inclination angle of the upper end, is the initial inclination angle of the upper end.

5.2.3. Comparison Between Experimental and Numerical Results

In the theoretical analysis, the contact surfaces between the scaffold ends and the end plates, as well as the junction between the inner and outer tubes, are assumed to behave as plastic hinges. The modified Shanley model was employed for calculation according to Equation (21), with the following parameters: initial eccentricities of 30 mm for DLZ-1 and DLZ-2, 20 mm for DLZ-3, an elastic modulus of 2.06 × 105 MPa, and a tangent modulus of 6100 MPa. The corresponding calculation results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison between experimental and theoretical results kN.

As can be seen from Table 2, the calculated results show good agreement with the experimental data for specimens DLZ-2 and DLZ-3, with errors within 10%. However, a relatively large discrepancy is observed for specimen DLZ-1, where the theoretical value exceeds the experimental result. This overestimation is non-conservative and is primarily attributed to the pinned connection at the upper end of DLZ-1, which provides weaker restraint compared to the assumed plastic hinge condition.

5.3. Finite Element Model

A refined three-dimensional finite element (FE) model of the independent steel support scaffolding was developed using C3D8R solid elements for all components. A dense mesh with a maximum size of 3 mm was employed to capture geometric details, particularly the tube wall thickness. To accurately simulate the performance at the joint, contact pairs must be defined between the inner and outer tubes. The tangential behavior of these contact pairs follows the Coulomb friction law with a friction coefficient of 0.3 to account for frictional slip, while the normal direction is modeled using a hard contact formulation. The model was validated against experimental data, confirming the effectiveness of the FE analysis.

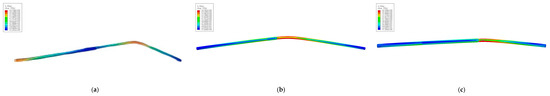

5.3.1. Finite Element Simulation Results

After completing the modeling and editing process, configure the relevant parameters for the analysis job in the JOB module, then submit the job for computation. Once the analysis is complete, proceed to the RESULTS module for post-processing. The stress contours of the three specimens at the onset of instability are shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

The stress contour after instability: (a) DLZ-1 stress distribution nephogram; (b) DLZ-2 stress distribution nephogram; (c) DLZ-3 stress distribution nephogram.

Through the results of finite element simulation, it can be found that the inner tube of the independent support scaffold is the weak point, and the intersection of the inner and outer tubes is also the starting point of bending instability. When DLZ-1 is compressed, the stress at both ends is very small, which is mainly due to instability failure in the column. The load on the column ends of DLZ-2 and DLZ-3 increased significantly, the stress at both ends changed greatly, and pressure damage occurred at the lower end of the outer tube. The simulation results are also very close to the experimental phenomena.

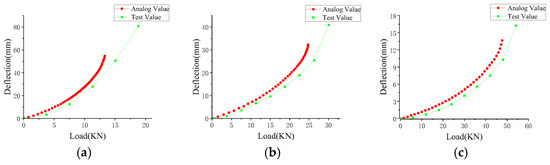

5.3.2. Analysis and Comparison

To account for the influence of initial curvature, initial deflection values were assigned to the three specimens accordingly. Considering the variation in specimen height, an initial deflection of 30 mm was adopted for DLZ-1 and DLZ-2, while 20 mm was applied to DLZ-3. Through computational analysis, load–deflection data at various locations of the independent steel scaffold support were obtained and plotted into curves. The load–deflection curve generated at the inner-outer tube junction was compared with experimental results, as shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Load–Deflection Curve at the Inner-outer Tube Interface: (a) DLZ-1; (b) DLZ-2; (c) DLZ-3.

A comparative analysis of finite element simulations and experimental results indicates that for specimens DLZ-1 and DLZ-2, both with a height of 3500 mm and an initial deflection of 30 mm, the simulated values are marginally higher than the experimental measurements. Nevertheless, the overall load–displacement curves exhibit close agreement and consistent variation trends. In the case of specimen DLZ-3, which features a reduced initial deflection of 20 mm, the simulation results align well with the experimental data. The maximum errors between the simulated and experimental results for the three specimens are 13.3%, 10.7%, and 8.1%, respectively. These deviations not only reflect a reasonably good agreement between the numerical predictions and test results but also confirm a direct correlation between the chosen initial deflection values and the specimen heights.

6. Conclusions

This study experimentally investigates the axial mechanical behavior of free-standing steel scaffold supports. By varying scaffold height, inner tube penetration length, and end connection conditions, and comparing ABAQUS finite element simulations with experimental results, the influence of these parameters on the axial performance and stability of the scaffolds is examined. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- Under vertical loading, the critical region is located at the junction of the inner and outer tubes. With increasing specimen height, a plastic hinge forms in this region under load. In shorter specimens, the inner tube fits tightly against the outer tube, resulting in a fixed-end condition, while the pin remains undamaged.

- (2)

- All specimens failed by instability. Reducing the specimen height significantly improves the load-carrying capacity. When the upper end is pin-connected, most specimens did not reach yield, indicating that the material’s compressive capacity was not fully utilized.

- (3)

- Replacing the upper pin connection with a plate restraint improves the compressive stability of the scaffold.

- (4)

- Adding an external sleeve at the inner–outer tube junction by mechanical fastening increases local stiffness, reduces initial curvature, and thereby enhances the compressive stability of the scaffold.

- (5)

- The derived formula based on the modified Shanley model, which accounts for variable hinge height and initial curvature, shows good agreement with the experimental results.

This study systematically reveals the mechanical behavior of the basic load-bearing unit in independent steel support scaffolding, while several aspects require further investigation: subsequent research will conduct sensitivity analyses on key parameters such as tube wall thickness and joint configuration, examine its dynamic response under cyclic loading, and further explore the overall stability of the spatial structural system composed of these units. These efforts aim to establish a complete analytical framework spanning from component to system and from static to dynamic behavior, thereby providing a more comprehensive theoretical basis for engineering applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; methodology, Y.L. and X.S.; validation, X.S. and I.L.H.; formal analysis, X.S. and J.H.; investigation, Y.L. and X.S.; resources, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.S.; writing—review and editing, X.S. and I.L.H.; supervision, Y.L.; funding acquisition, Y.L.; data curation and editing, X.H. and L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51878590).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xingyu Song was employed by the company Jiangsu Huajian Construction Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Pieńko, M.; Błazik-Borowa, E. Numerical analysis of load-bearing capacity of modular scaffolding nodes. Eng. Struct. 2013, 48, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Liu, H.; Lei, M.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Guo, L.; Gong, X.; Fang, Z. Effective length correction factor of disc-buckle type scaffolding by considering joint bending stiffness and geometrical size. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Peng, G.; Niu, D.; Fan, Y. Experimental study on mechanical properties of steel tube-coupler connections in corroded scaffolds. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2021, 176, 106383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chandrangsu, T.; Rasmussen, K. Probabilistic study of the strength of steel scaffold systems. Struct. Saf. 2010, 32, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Liu, H.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wen, S. Mechanical properties of right-angle couplers in steel tube–coupler scaffolds. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2016, 125, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.P.; Cai, X.F. Constitutive relation research on anti-slipping performance of right-angle fastener steel pipe joints. Constr. Technol. 2011, 40, 86–88. [Google Scholar]

- Weesner, L.; Jones, H. Experimental and analytical capacity of frame scaffolding. Eng. Struct. 2001, 23, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Rasmussen, K.J.; Ellingwood, B.R. Reliability assessment of steel scaffold shoring structures for concrete formwork. Eng. Struct. 2012, 36, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.F.; Ross, D.A. The axial strength and behavior of cylindrical columns. J. Pet. Technol. 1977, 29, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.; Zhao, X.-L. Imperfection, residual stress and yield slenderness limit of very high strength (VHS) circular steel tubes. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2003, 59, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’SHea, M.D.; Bridge, R.Q. Local buckling of thin-walled circular steel sections with or without internal restraint. J. Constr. Steel Res. 1997, 41, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Cui, H.; Yang, F.; Huang, T.; Zhang, R.; Hou, X. Experimental study on axial compressive behavior of circular steel tubes strengthened by sleeved pipe. J. Build. Struct. 2020, 41, 198–206. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.M.; Fan, X.Z.; Song, F.F.; Cheng, J.J. Study on stability capacity correction coefficient of coupler steel tube falsework. J. Saf. Environ. 2011, 11, 209–212. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, X.; Lin, B.; Cong, J.; Zhang, L. Study on stability of casting-extended scaffolding steel pipe under axial compression. J. Build. Struct. 2022, 43, 228–238. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorhovde, R.; Colson, A.; Brozzetti, J. Classification system for beam-to-column connections. J. Struct. Eng. 1990, 116, 3059–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Kirby, P.; Nethercort, D. The analysis of frames with semi-rigid connections—A state-of-the-art report. J. Constr. Steel Res. 1983, 3, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Guo, Z. Investigation of joint behavior of disk-lock and cuplok steel tubular scaffold. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2021, 177, 106415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.; Huang, H.; Fang, L. Advanced Analysis of Imperfect Portal Frames with Semirigid Base Connections. J. Eng. Mech. 2005, 131, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Liu, H. Buckling behavior of a wheel coupler high-formwork support system based on semi-rigid connection joints. Adv. Steel Constr. 2022, 18, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Tang, Q.; Liu, Z. A numerical study on rotational stiffness characteristics of the disk lock joint. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2023, 207, 107968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, A.; Arjomand, M.A.; Bagheri, M.; Ebadi-Jamkhaneh, M.; Mostafaei, Y. Assessment of Experimental Data and Analytical Method of Helical Pile Capacity Under Tension and Compressive Loading in Dense Sand. Buildings 2025, 15, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, M.; Malidarreh, N.R.; Ghaseminejad, V.; Asgari, A. Seismic resilience assessment of RC superstructures on long–short combined piled raft foundations: 3D SSI modeling with pounding effects. Structures 2025, 81, 110176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Rasmussen, K.J. System-based design for steel scaffold structures using advanced analysis. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2013, 89, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrangsu, T.; Rasmussen, K.J. Structural modelling of support scaffold systems. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2011, 67, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Chen, G.; Yin, L. Multi-parameter simulation method of semi-rigid node of steel tubular scaffold with couplers. J. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2019, 41, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.S.; Xu, Z.D.; Guo, Y.Q.; Jia, H.; Huang, X.; Wen, Y.W. Mathematical modeling and test verification of viscoelastic materials considering microstructures and ambient temperature influence. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2022, 29, 7063–7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB50017-2017; Standard for Design of Steel Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2017.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).