Abstract

With urbanization slowing, the world has entered a new phase focused on stock-based development, where urban renewal plays a key role in advancing sustainable urbanization. These projects involve multiple stakeholders—governments, enterprises, and residents—whose conflicting interests often hinder progress and affect policy outcomes, equity, and long-term sustainability. This study is conducted to address existing gaps in understanding the dynamic mechanisms and multi-dimensional relationships underlying stakeholder conflicts in urban renewal projects (URPs). A total of 28 key influencing factors are identified and categorized. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) is then applied to reduce data dimensionality, resulting in five core dimensions: economic, legal, implementation, managerial, and social factors. Building on these findings, a system dynamics (SD)-based model is developed to simulate the interactions and evolutionary pathways of these factors within urban renewal projects. Results show that all five factors contribute to conflict to varying degrees, with economic factors being the primary driver. Drawing on empirical data from Chinese URPs, this study provides both theoretical insights and practical implications for policy formulation and governance strategies aimed at promoting more harmonious and sustainable urban renewal processes.

1. Introduction

Global urbanization is accelerating, with cities expanding rapidly due to population growth and economic development. By 2050, nearly 70% of the world’s population is expected to live in urban areas. Recently, China has experienced a significant and rapid urbanization process, with the national urbanization rate reaching 66.16% by 2023. The rapid growth of urban areas poses challenges such as infrastructure strain, environmental issues, social inequalities, resource shortages, and unbalanced growth [1], driving the need for urban renewal (UR).

In China, the concept of UR gained prominence in 2019 when it was first strengthened at the Central Economic Working Conference of China. This concept emphasizes the renovation and upgrading of existing housing stock. In the latest government opinion on continuing the promotion of urban renewal in 2025, it is emphasized that the approach to urban development and construction should be transformed to foster livable, resilient, and smart cities. This signals that UR in China has reached a new stage characterized by institutionalization and sustainability.

Despite the critical role of stakeholder conflicts in UR, existing research exhibits significant shortcomings in analyzing conflict factors and their dynamic evolution. Especially, many studies focus on single conflict causes, such as inadequate legal and policy frameworks [2] and challenges in distributing land value appreciation [3], but fail to systematically explore the interrelations among conflict factors. For example, Atkinson (2019) examines the spatiotemporal characteristics of housing stock under Seoul’s UR policies, proposing sustainable growth management, yet does not delve into the mechanisms of multi-stakeholder conflicts [4]. Similarly, Agbiboa (2018) develops an analytical framework for Chinese UR policies, identifying policy types, but does not quantify the significance or interactions of conflict factors [5]. Furthermore, prior studies rarely integrate qualitative and quantitative methods to capture the dynamic evolution of conflicts, such as how conflicts escalate or subside over time in response to policy changes [6]. These limitations hinder a comprehensive understanding of conflict management mechanisms in UR, impeding the design of effective policies and coordination strategies. Consequently, there is an urgent need for systematic research that employs quantitative analysis and dynamic modeling to uncover the complex interrelations and evolutionary patterns of conflict factors, thereby supporting sustainable UR.

To fill this research gap, this study systematically investigates stakeholder conflict factors and their dynamic evolution in urban renewal projects (URPs). The research objectives (ROs) are as follows:

- RO1: To identify stakeholder conflict factors in URPs.

- RO2: To group the conflict factors from the list obtained in RO1.

- RO3: To reveal their correlation and dynamic evolution of conflict factors, building on the findings from RO1 and RO2.

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, integrating a systematic literature review (SLR) and a multi-case study to identify conflict factors, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to classify factors, and system dynamics (SD) to develop a dynamic evolution model. This approach can capture the complexity and dynamism of conflict factors, suitable for multi-stakeholder UR contexts [6]. This study extends stakeholder theory by introducing a dynamic conflict analysis framework in UR, providing new insights into conflict management. The findings provide a scientific basis for policymakers and project managers to optimize interest coordination, develop adaptive conflict management strategies, and improve public participation and policy.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Stakeholder Conflict in UR

Stakeholder theory, introduced by Freeman, is a framework that emphasizes the significance of managing relationships with various groups and individuals who have a stake in an organization [7]. It recognizes that organizations operate within a network of interconnected stakeholders, each with different interests, needs, and levels of influence. The theory argues that organizations should consider the interests of all stakeholders—beyond just shareholders—in decision-making processes to create long-term value and sustainable outcomes [8]. In URPs, stakeholders—such as government agencies, developers, residents, and community groups—often have competing objectives, creating complex dynamics that shape project outcomes [9,10,11,12]. The theory facilitates the analysis of power relationships, conflict sources, and collaboration potential among stakeholders, thus offering insights into the negotiation processes required to achieve balanced development [13,14,15,16].

Conflict is defined differently across various subjects and by different scholars. Conflict is a process where various stakeholders compete for limited resources, but also reflects differences regarding thoughts, interests, and other aspects among stakeholders [13]. Interest is a fundamental factor in the emergence of conflict; hence, disputes over interests are often an inevitable trigger. Stakeholders take measures to address their interests’ damage and effectively resolve conflicts while keeping them at a reasonable level [15]. The evolution of conflict is a process where individuals with differing values, interests, and methods argue and, at times, attack each other over time [17]. The progression from conflict to crisis involves various elements, including events, scenarios, role conflicts, stress levels, and potential crises [18]. Based on previous research on stakeholders’ conflict definition and characteristics, conflict in UR can be defined as a process where various stakeholders engage in actions against each other to achieve their own goals and demands [19,20,21]. This conflict stems from the differences among stakeholders in renewal goals and demands.

In the Chinese context, these conflicts are shaped by unique institutional factors, such as the hukou system influencing resident relocation and state-owned land policies differing from private property rights in Western cities, leading to heightened power imbalances between government and residents compared to more pluralistic urban governance in Europe or North America [4,22,23].

2.2. Conflict Factors of Stakeholders in UR

The factors contributing to stakeholder conflict in UR can be categorized into two types: qualitative indicators and quantitative indicators. Currently, numerous studies have been conducted to identify, quantify and mitigate stakeholder conflicts in URPs [16,20,22,23], and many scholars focus on qualitative research regarding conflicts between stakeholders in UR, approaching the topic from various perspectives [10,11].

Domestic research, primarily from Chinese scholars such as Liu and Wang, emphasizes government roles in benefit sharing and land system problems unique to China’s rapid urbanization and state-led development model. In contrast, international studies [24,25], like those by Atkinson in the UK and Agbiboa in Lagos, highlight market-driven conflicts and urban injustices in more decentralized institutional frameworks [4,5]. These differences underscore how China’s centralized legal and institutional structures amplify government-stakeholder tensions, while international contexts often feature stronger resident participation mechanisms.

Some scholars have examined the phenomenon of urban injustice in London’s “new urban renewal” and the resulting social conflicts between stakeholders, attributing these conflicts to the uneven distribution of benefits between developers and original property owners in the renewal area [26]. Others have taken a foreign URP as an example, identifying the lack of comprehensive legal regulations and policy systems as the main reason for large-scale conflict incidents [27]. Many scholars, using interviews with stakeholders and literature reviews, have highlighted the characteristics of UR and traffic demand in India. They argue that increased government investment in urban infrastructure and basic services for the urban poor is essential to effectively avoid conflicts between stakeholders [28]; Yildiz and others carried out a questionnaire survey, revealing that from the government’s perspective, the protection of natural resources is seen as a conflict with developers over nature conservation [29]; demolition and compensation continue to be challenges in UR, especially under the new normal, and high contract transaction costs have resulted in demolition conflicts, leading to stalled renewal projects [1]; conflicts in UR often arise due to a lack of mutual communication and negotiation mechanisms between parties [30]. In UR, the government plays multiple roles, including policy-maker, land expropriator, and supervisor; therefore, this can lead to unavoidable bias in its positioning and unclear boundaries in its responsibilities [31]. In some cases, local governments have caused conflicts in the practice of renewal by failing to provide compensation or making unreasonable administrative decisions, despite corresponding preferential policies [32]; through qualitative analysis, some scholars have identified factors such as unclear land property rights, untimely information disclosure, poor contract performance, and increased negative social opinions as significant inducements for conflicts between stakeholders in UR [24,33,34,35,36].

In summary, scholars from both domestic and international circles have explored the factors driving conflicts between stakeholders in UR from various perspectives, focusing primarily on areas such as benefit distribution, financing models, historic districts, resident participation, legal systems, property rights, demolition and compensation, communication mechanisms, and government responsibilities, etc. On the other hand, some researchers have explored the causes of conflicts between stakeholders in UR using quantitative methods. For instance, by analyzing stakeholder demands and conflicts, they developed game models to find balanced solutions [37]; econometric models have been used to analyze factors that induce conflicts among stakeholders in URPs [38]; utilizing a constructed social network model, they categorized stakeholders and highlighted that the collaboration intensity of core stakeholders is a crucial indicator for assessing conflict levels [39].

2.3. Gap in Knowledge

Existing research on stakeholder conflicts in UR primarily focuses on single factors such as inadequate legal frameworks [27], land value appreciation [3], or qualitative analyses, lacking empirical case studies and systematic integration of multi-dimensional factors [4]. The interrelations and dynamic evolution of conflict factors or quantifying their significance are unexplored, which is particularly pronounced in the Chinese context, where local specificities like the dual urban-rural land system and rapid policy shifts (e.g., from demolition-focused to resident-inclusive approaches post-2020) influence conflict evolution differently than in international settings, necessitating tailored dynamic models [6].

Given the complex demands of multiple stakeholders in UR, this gap hinders effective policy design and collaboration. This study addresses this by integrating SLR, EFA, and SD to develop a dynamic conflict evolution model. This model reveals the interrelation and evolution of stakeholder conflict factors in URPs, offering valuable insights for government departments to refine conflict management strategies among stakeholders.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Research Design

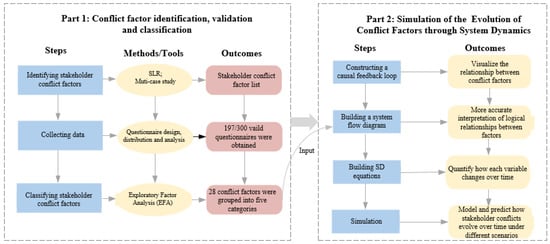

This study adopts a mixed-methods design, integrating SLR, multi-case study, EFA, and SD, to systematically analyze stakeholder conflict factors and their dynamic evolution in URPs. The mixed-methods approach combines qualitative and quantitative data to capture the complexity and dynamism of conflict factors, overcoming the limitations of single-method studies in multi-stakeholder contexts. The research design is structured into three phases, aligning with the research objectives (RO1–RO3), as shown in Figure 1:

- (1)

- Conflict Factor Identification (RO1): SLR and multi-case study are used to identify conflict factors in UR, integrating literature and empirical data to form a comprehensive factor list.

- (2)

- Conflict Factor Classification (RO2): EFA is applied to questionnaire data to classify conflict factors into distinct dimensions, revealing their underlying structure.

- (3)

- Dynamic Evolution Modeling (RO3): SD is employed to construct causal feedback models and stock-flow diagrams, simulating the interactions and evolution of conflict factors, validated through a case study.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Literature Analysis

The SLR, following PRISMA guidelines, screened 147 peer-reviewed articles from 2010–2023 related to urban renewal conflicts (see Section 2.3), extracting 22 preliminary conflict factors across economic, legal, management, and social dimensions, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Conflict factors derived from the literature review.

3.2.2. Multi-Case Study

To address the lack of case-based validation in the literature, a multi-case study employed grounded theory, analyzing five representative Chinese URPs, including Changsha’s historical preservation and Beijing’s affordable housing projects, covering diverse project types and stakeholders. Through 60 in-depth interviews (15 government officials, 10 developers, 25 residents, 10 experts) and three-level coding (open, axial, selective), 6 additional factors were identified, including “Inadequate environmental governance”, “Unclear responsibility boundaries for government”, “Inadequate financing capacity”, “Inadequate financing capacity”, “Inadequate laws and regulations”, “Imperfect conflict accountability mechanisms” and “Imperfect public participation platform”(see in the Supplementary Materials). As shown in Table 2, coding consistency was validated using NVivo 14, with a mean Cohen’s Kappa of 0.806 (range 0.773–0.829), indicating high reliability [56,57].

Table 2.

Consistency results of data coding.

3.3. Sample and Date Collection

Based on the factors extracted by SLR and multi-case study, this paper designed a questionnaire on the conflict factors faced by stakeholders in URPs. The questionnaire adopts the Likert 5-point scale, which is mainly divided into two components: the basic information of the respondents and the comparison of conflict factors (see in the Supplementary Materials). To ensure the questionnaire’s rigor, given the large number of stakeholders in UR, this study distributed it to residents of the renewal area, government officials, enterprise-related managers and scholars from universities. It was mainly carried out in two ways: (1) via the WeChat platform and (2) through field research.

A total of 300 questionnaires were distributed to the target population; 209 were returned, and 197 were deemed valid after excluding incomplete or inconsistent responses. The effective response rate was calculated at 94.26%. This sample size and response rate are considered sufficient to support the subsequent analysis [58]. The demographics of the 209 respondents are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Demographics of respondents.

4. Research Results

4.1. Identification of Stakeholder Conflict Factors

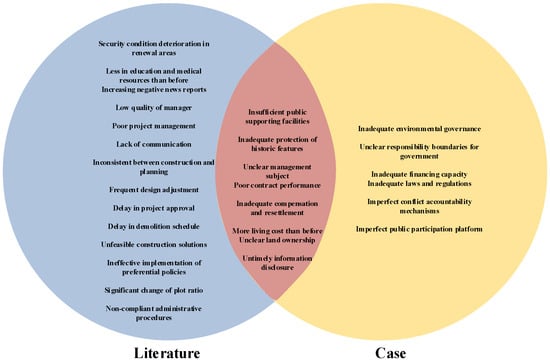

In total, 28 conflict factors were finally identified by using a systematic literature review (SLR) and a multi-case study, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Conflict factor identification.

The stakeholder–conflict factor matrix was created to clearly show the connections between stakeholders and conflict factors, with a value of 1 representing a direct link between a stakeholder and a conflict factor, and 0 indicating no direct connection, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Stakeholder–conflict factor matrix.

4.2. Classification of Stakeholder Conflict Factors

To identify the underlying groups, 28 critical factors are analyzed by EFA. The ratio between 197 cases and 28 items is 7.04 (>5.00), indicating the sample size is sufficient to conduct an EFA. Furthermore, the KMO value is 0.886, which indicates excellent sampling adequacy for factor analysis.

Bartlett’s test of sphericity produces an approximate chi-square of 5211.316 (df = 378, p < 0.000), which supports the normal distribution assumption. All these demonstrate the suitability of data on critical factors for conducting an EFA. Based on the results of the Scree plot and the interpretability of the factors, the optimal solution comprises five factors, in which the items loading on each factor have a conceptual meaning, and the items loading on different factors measure different constructs. As the maximum correlation coefficient between each construct is higher than 0.32, oblique rotation is conducted. The rotated pattern and structure matrix of the five groups of critical SCFs are presented in Table 5. The five categories—economic, legal, implementation, managerial, and social—emerged from EFA based on statistical criteria: eigenvalues greater than 1, scree plot inflection, and conceptual interpretability. For instance, economic factors loaded highly on items like ‘unfair distribution of benefits’ (loading 0.82), providing empirical support for their cohesion as a distinct dimension. All factor loadings were greater than 0.60, and the extracted five constructs explained 77% of the total variance of the results.

Table 5.

Rotated component matrix.

4.3. Construction of Conflict Factors Evolution Model Based on System Dynamics

4.3.1. Determination of Conflict Factor Weights Based on the Entropy Weight Method

Quantifying conflict factors can be challenging. Therefore, we employ the entropy weight method to calculate the weight of each conflict factor, which is then used as a coefficient in the SD equation.

Calculate the entropy value of each index:

where Xij is the value of the j-th evaluation object after standardization under the i-th evaluation index.

Calculate the weight of each index

To assess the weight of conflict factors in China’s URPs, we invited seven experts, including government practitioners, project managers, university researchers, and developers, to provide their ratings. The weight values for each factor were ultimately calculated and are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Weight of each conflict factor.

4.3.2. Dynamic Evolution of Conflict Factors

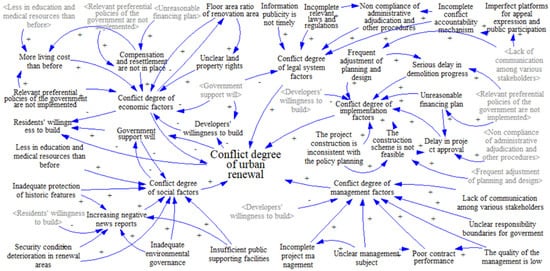

The conflict evolution process in URPs is a complex dynamic system influenced by the interaction of multiple internal variables. Based on the analysis of conflict factors in UR and the causal feedback relationships among these variables, an SD model of conflict influencing factors has been constructed [59]. This system comprises five subsystems, identified using the loop analysis method, which considers the system’s characteristics and functions. In this model, each conflict factor is represented as a positive indicator.

- (1)

- Conflict degree of economic factors ↑→ Residents’ willingness to build ↓→ Developers’ willingness to build ↓→ Conflict degree of management factors ↑→ Conflict degree of urban renewal ↑→ Conflict degree of economic factors ↑.

- (2)

- Conflict degree of legal system factors ↑→ Conflict degree of urban renewal ↑→ Willingness of government support ↓→ Conflict degree of legal system factors ↑.

- (3)

- Conflict degree of implementation factors ↑→ Conflict degree of urban renewal ↑→ Willingness of government support ↓→ Conflict degree of economic factors ↑→ Willingness of residents to build ↓→ Willingness of developers to build ↓→ Conflict Degree of implementation factors ↑.

- (4)

- Conflict degree of management factors ↑→ Conflict degree of urban renewal ↑→ Willingness of government support ↓→ Conflict degree of economic factors ↑→ Willingness of residents to build ↓→ Willingness of developers to build ↓→ Conflict Degree of management factors ↑.

- (5)

- Conflict degree of social factors ↑→ Conflict degree of urban renewal ↑→ Willingness of government support ↓→ Conflict degree of social factors ↑.

The causality diagram, including these loops, is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Cause and effect loop diagram of urban renewal conflict factors.

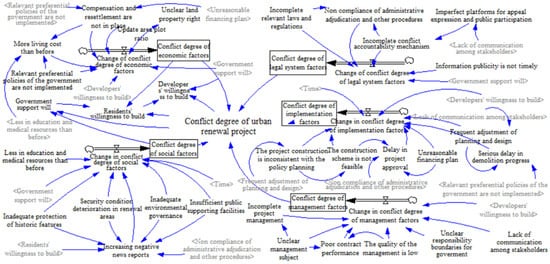

The causal feedback map represents the foundational feedback structure of the URP conflict factor system. While it reflects the causal relationships among various factors, it does not distinguish the different natures of the variables. A conflict stock map of URPs is necessary to define the types of variables. To accurately explain the logical relationships between factors, auxiliary variables such as developers’ construction willingness A1, government support willingness A2, and residents’ construction willingness A3 are introduced, representing the core interest subjects of the project. The feedback chart further clarifies the types of factors from the perspectives of the economy, the legal system, their implementation, their management, and society. Meanwhile, the state variables, rate variables, auxiliary variables, and constants within the model are identified. The Vensim PLE software version 10.0 is adopted to construct a stock flow diagram of urban renewal conflict factors, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Stock flow of urban renewal conflict factors.

The SD equation for URP conflicts is constructed based on the system dynamics flow chart and the weight values of conflict factors determined using the entropy weight method, as shown in Table 7. The conflict persists throughout the entire project life cycle, with varying impacts in different phases. The conflict persists throughout the entire project life cycle, with varying impacts in different phases. Given the presence of time nodes in both the decision-making and implementation stages, we denote a as the endpoint of the decision-making stage and b as the endpoint of the implementation stage. The employed functions encompass INTEG integral, IF THEN ELSE selection, and DELAY delay function.

Table 7.

Main SD functions of conflict factors in URPs.

5. Case Study

5.1. Case Overview

The renovation area houses a total population of 12,270 people, comprising nearly 3752 families, and hosts over 3000 commercial tenants. The first phase of the project spans over 70,000 square meters and accommodates a significant floating population. The project’s franchise period is set at 30 months, including an 18-month construction phase. Successful operation is anticipated through the collaborative efforts of the government, developers, original owners, and other stakeholders.

Due to the continuity of history, the inheritance of customs, the complexity of the architectural pattern, and the extended construction period, the substantial progress of the renewal has been limited. The renovation aims to integrate environmental resources and accentuate the community’s unique characteristics. However, the complexity of the land environment, coupled with challenges in financing, design, construction, and government measures, has hindered the full development of the approved renovation area.

5.2. Simulation Data Input

Taking the Neighborhood X renewal project as an example, constants were assigned based on the project’s relevant data. Relevant stakeholders and experts were invited to use the Delphi method, based on the constructed conflict factor indicators and simulation model, to score the boundary factors using the project’s relevant information according to Table 8. To maintain consistency among conflict factors, all boundary conflict factors were converted into scaled indicators with values ranging from 0 to 1. Experts 1–7 give (a, b, c) as (0.2, 0.3, 0.4), (0.1, 0.3, 0.2), (0.2, 0.3, 0.1), (0.2, 0.3, 0.3), (0.1, 0.4, 0.4), (0.2, 0.2, 0.5), and (0.1, 0.3, 0.5). According to Formula (3), the initial value of 0.27 is calculated for the “less in education and medical resources than before”, the same approach was used to obtain the initial values for other boundary conflict factors, as shown in Table 9. Set the model’s starting value (initial time) to 0, the termination value (final time) to 30, the time unit to months, and the step size DT = 1. The UR stakeholders’ conflict factor value and functional relationship are input into the model. The model can start running after the validity and stability test and debugging.

where a denotes the minimum impact value of this conflict factor on the stakeholder conflict system in urban renewal projects. b denotes the most likely impact value of this conflict factor on the stakeholder conflict system in urban renewal projects. c denotes the maximum impact value of this conflict factor on the stakeholder conflict system in urban renewal projects.

Table 8.

Assignment of conflict factors.

Table 9.

Initial value assignment of the boundary conflict factor of the municipal project.

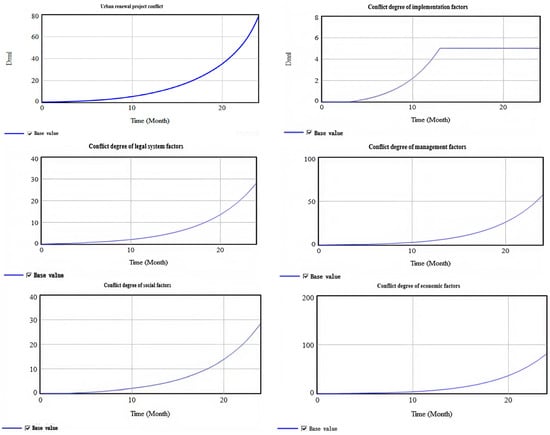

5.3. Analysis of Basic Simulation Results

As illustrated in Figure 5, under initial conditions, the conflict degree in URPs initially shows a slight increase, followed by a rapid escalation. This trend results from the combined impact of various factors within internal subsystems, including implementation, legal system, social, management, and economic factors. If these conflict factors remain uncontrolled, the probability of conflicts escalates to nearly 100% over time, making project disputes an inevitable occurrence.

Figure 5.

Conflict degree of URP and basic operation diagram of each subsystem.

In the initial state, the conflict of implementation factors arises solely during the implementation phase, leading to an upward trend in conflict degree during this stage. Social factor conflicts, as identified earlier, emerge only after implementation, highlighting a clear distinction between the decision-making and implementation stages. Initially, social factor conflicts are almost non-existent during the decision-making stage, but grow over time. Conflicts related to the legal system, management, and economic factors persist throughout the URP’s life cycle, leading to a continuous rise in conflict levels. The project conflict becomes intractable once it accumulates to a certain degree.

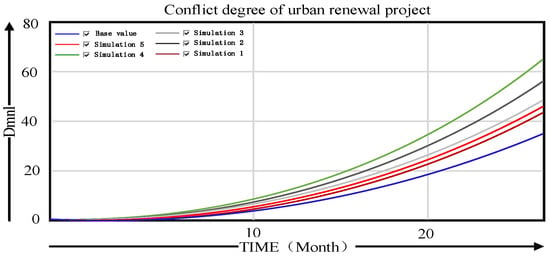

5.4. System Model Comparison and Analysis

The effects of various factors on the conflict degree in URPs are systematically compared and analyzed. Using the control variable method, the initial constant values of each dimension were doubled [60], yielding the simulation results depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Comparison and analysis of subsystems of the conflict degree of URP.

- (1)

- In Simulation 1, the assignment of management factors was changed based on initial values, enhancing their role in conflict within URPs. The results indicate that while the degree of project conflict increased, the effect was less pronounced compared to the initial state in this scheme.

- (2)

- In Simulation 2, the assignment within the implementation factors was changed based on the initial value, aiming to enhance their conflict effect on the project. The results demonstrate an obvious increase in the project’s conflict degree compared to the initial state.

- (3)

- In Simulation 3, only the assignment of legal system factors was altered based on the initial value, thereby enhancing their role in project conflict. The results indicate a significant increase in project conflict degree compared to the initial state.

- (4)

- In Simulation 4, the assignment of economic factors was solely changed based on the initial value, aiming to improve their conflict effect on the project. The results reveal that this approach led to the most significant increase in project conflict degree compared to the initial state.

- (5)

- In Simulation 5, the assignment of social factors was modified based on the initial value, enhancing their impact on project conflict. The results demonstrate that although there is an increase in the project conflict degree compared to the initial state, the effect is the least noticeable.

Consequently, the simulation results show that the impact of the five schemes on URP conflicts can be ranked in order of significance: economic factors, implementation factors, legal system factors, social factors, and management factors. Initially, the impact of conflict factors from each dimension on the project’s conflict degree is minimal. During the middle and late stages, economic factors’ conflict has the most significant impact, with a notably rapid improvement rate. The conflict in URPs, under various renewal modes, is largely influenced by the patterns and demands of different stakeholders’ interests during the renewal and transformation process. Furthermore, the implementation of URPs involves land redevelopment, which faces various constraints, including market and planning factors. Diverse stakeholders play varied roles in this process, and the interplay of their interests facilitates the implementation of URPs.

6. Discussion

6.1. Key Findings

Conflicts among stakeholders in URPs stem from a variety of factors, each influencing the outcomes of these processes. Notably, economic considerations emerge as the most critical and impactful factors in shaping the intensity of stakeholder conflicts throughout the process.

The economic aspect is central in the disputes that arise during UR. Stakeholders, including developers, residents, and government entities, often prioritize economic issues, leading to clashes over compensation rates, preferential policies, living costs, or unclear property rights during demolition [61,62]. When these expectations go unmet, stakeholders often adopt a self-serving stance, moving away from collaboration. This deviation can hinder the overall progress of UR efforts. In Beijing’s affordable housing renewal projects, economic conflicts manifest through disputes over compensation, where residents protest inadequate relocation payments, leading to project delays. To mitigate these conflicts, it is essential to establish a fair and effective mechanism for the distribution of benefits, one that bridges these gaps and promotes stakeholder cooperation, thereby enhancing the sustainability of UR [63].

Legal factors also significantly influence the dynamics of UR conflicts. In the context of China’s UR framework, the government takes the lead in the process, while market operations and resident participation are integral components [26]. A comprehensive legal framework, along with an effective conflict resolution mechanism and platforms for residents’ appeals, is vital for balancing the diverse interests of all parties involved [27]. The government’s role in policy guidance enables developers to effectively utilize market mechanisms for land allocation and encourages resident involvement, optimizing land use, enhancing environmental quality, and boosting economic growth [26]. Consequently, a well-structured legal system serves as a foundation for aligning economic objectives with broader societal goals, reducing conflicts through enhanced clarity and accountability.

The transition from a government-centric model to one that includes a wider array of stakeholder engagement has led to the emergence of new conflicts during the implementation of UR. The 2020 Urban Renewal Guidance issued by the General Office of the State Council emphasizes the importance of utilizing residents’ resources and promoting extensive participation [30]. However, this multi-stakeholder framework remains in a state of development, and disparities in construction plans, financial resources, and project progress frequently result in conflicts among participants [28]. These challenges highlight the vital importance of coordination and effective communication in preventing conflicts from obstructing the progress of URPs.

Management in UR aims to optimize sustainable urban development by balancing diverse stakeholder demands, reconciling competing spatial visions [31]. This process is fundamentally shaped by China’s centralized socio-political system, where institutional power asymmetries contrast sharply with decentralized Western models like the UK’s community-led approaches that mitigate resident-government tensions [4]. Such institutional dynamics manifest in intra-governmental conflicts, exemplified by Changsha’s historical preservation projects, where sustainability-oriented planning departments and cost-driven finance units experienced implementation delays due to bureaucratic fragmentation. Effective management must therefore ensure equitable benefit distribution that prioritizes vulnerable populations while maintaining procedural fairness [32]. As urbanization and industrialization continue to advance, the scope of URPs broadens, making differences in stakeholders’ management capabilities, contract implementation, and administrative quality key factors in resolving conflicts.

Moreover, social factors, although less direct, extend the scope of conflicts to groups such as the public, mass media, and communities that may not be directly engaged in the renewal or transformation of urban areas, the degradation of public spaces—evidenced by the loss of historical landmarks, diminished public safety, or incomplete infrastructure—can intensify conflicts [24,32]. Such social dynamics significantly influence public perceptions of UR and have the potential to heighten tensions if not adequately managed.

Numerous factors contribute to conflicts among stakeholders; however, economic concerns are particularly influential in determining the intensity of such conflicts within URPs. Although the scope of UR has expanded to include social and environmental considerations, the economic dimension remains a fundamental pillar for sustainable development [34]. Stakeholder expectations differ significantly: the government and public often prioritize overall economic growth, whereas residents tend to prioritize their immediate financial security. This disparity in priorities can compromise the notion of “public interest,” a core value in China’s UR model [9]. In response to these differences, the government’s strategy has focused on fostering economic growth through sustainable development, which in turn helps reduce conflicts among stakeholders [35]. Thus, managing the most sensitive sources of conflict, especially economic factors, is critical to the success of URPs.

In summary, although legal, management, and social factors contribute to conflicts in UR, economic factors are the predominant and most significant influences in these disputes. A comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of economic conflict, along with the recognition of the varying interests of stakeholders, is essential for achieving successful UR. By emphasizing equitable economic distribution and addressing the financial concerns of all parties, it is possible to mitigate tensions, encourage collaboration, and ultimately enhance the sustainability of UR outcomes.

6.2. Theoretical Contribution

The research conducted makes several contributions to existing theories in the urban renewal conflict field.

By exploring how these factors interconnect, the study moves beyond isolated issues and offers a fresh way of looking at the bigger picture. The three-stage framework—identifying the conflict factors, examining their interactions, and building a model—opens up new paths to understanding how conflicts develop and influence the dynamics of urban renewal. Unlike other studies that often focus on specific factors like inadequate laws [36], policy shortcomings [37], failures in compensation [38], or flawed administrative processes [39], this work takes a step back, calling for a more systematic exploration of the conflicts’ underlying nature. In addition, it brings forward an empirically grounded conflict model that stands apart from the usual qualitative approaches, adding depth to discussions around stakeholder conflicts. Instead of staying within theoretical confines, it proposes practical strategies for conflict coordination, aligning with the messy realities that urban renewal projects often face.

6.3. Practical Implication

The present study also offers valuable reference material and practical guidance for management practices.

- (1)

- Enhancing conflict anticipation

The dynamic model in this study can predict how conflicts evolve in URPs, where competing interests from stakeholders like local communities, private developers, and municipal governments often collide. This foresight helps streamline project execution, cutting conflict resolution costs and making outcomes more predictable.

Operational measures include implementing early conflict-detection systems, such as AI-driven sentiment analysis tools on public feedback platforms to monitor resident concerns in real-time, stakeholder communication models like regular town hall meetings facilitated by neutral mediators, and coordination protocols such as multi-party agreements with clear escalation procedures for aligning interests.

- (2)

- Informing policy design and governance structures

This study offers valuable insights into designing adaptive, inclusive policies and governance structures that address the complexities of URPs. It shows that conflicts in URPs are not isolated events but part of a larger, dynamic system with interconnected factors. Policymakers can use the system dynamics model to craft flexible governance frameworks that adjust to changing conditions.

These recommendations can be adapted to local circumstances by tailoring them to regional economic disparities—for instance, in wealthier cities like Beijing, emphasizing digital communication models, while in less developed areas, focusing on community-based protocols. Potential obstacles include resistance from entrenched interests or resource constraints, which can be mitigated through phased implementation and stakeholder buy-in.

- (3)

- Facilitating sustainability and long-term urban development

Sustainability is at the heart of successful UR, and the study’s dynamic model offers insights into how UR can achieve lasting social, economic, and environmental sustainability through an adaptive, systems-based approach. The interconnected nature of conflict factors shows that UR must go beyond economic growth, integrating social and environmental aspects to build long-term resilience and equity.

A key distinction lies between state-led regeneration projects, where the public sector dominates conflict management through regulatory enforcement and top-down protocols, and privately initiated ones, where market-driven mechanisms like incentive-based coordination prevail, potentially leading to faster resolutions but greater equity challenges without government oversight.

This study provides UR professionals with a clearer grasp of the underlying causes and shifting dynamics of stakeholder conflicts in urban development. Exploring the evolving nature of these conflicts offers the tools needed to move beyond reactive responses, guiding a more proactive, inclusive, and adaptable approach to urban development. These findings are crucial not only for refining the management of individual URPs but also for influencing the wider policies and practices that drive urban development across different contexts.

7. Conclusions

UR is primarily a social public project that engages a variety of stakeholders, and the complex interactions among these groups significantly influence the outcomes of renewal projects. This research aims to identify conflict factors from a multi-stakeholder perspective and develop a dynamic model to track their evolution in URPs. A comprehensive analytical model is proposed, integrating SLR, grounded theory, EFA, and SD. SLR and grounded theory are used to identify conflict factors in urban renewal projects, while EFA uncovers latent patterns. Based on the identified conflict factors, the interaction mechanisms are analyzed, and an SD-based causal feedback diagram, inventory flow diagram, and state equation are constructed. Simulation analysis reveals the order of influence of conflict factors on the degree of conflict: economic, implementation, legal system, social, and management factors, providing theoretical support for conflict coordination in URPs. In short, effective stakeholder conflict management in URPs depends on creating a fair benefit distribution scheme, balancing interests, and ensuring smooth implementation. Additionally, successful conflict management requires coordinating information exchange and building trust among core stakeholders, including the government, enterprises, and original property owners. Limitations of this study include its reliance on Chinese-specific data, potentially limiting generalizability to other contexts. While the findings on economic factors as primary drivers may transfer to European cities facing similar stakeholder conflicts, adaptations would be necessary, such as incorporating EU regulations on public participation and environmental impact assessments, which differ from China’s centralized system. This positions the research as a foundation for future comparative analyses between Asian and European urban renewal models.

Although this research has made certain contributions, there are still some research directions that are worth further exploration in the future. Firstly, this study focuses on Chinese URPs, which may restrict transferability; however, core insights like the dominance of economic factors could apply to European contexts with adaptations for decentralized governance and stronger legal protections for residents. Future studies could conduct comparative analyses to test these adaptations across diverse institutional systems.

Secondly, while the case study demonstrates the method via theoretical simulation, it is abstract in nature, with assumptions such as simplified causal relationships and fixed weights from the entropy method. Limitations include the model’s generalizability beyond the simulated Chinese context and potential underestimation of qualitative factors not captured in quantitative inputs. Further research could pay more attention to the mechanisms of conflict emergence among stakeholders in URPs and their governance in a wider range of scenarios. Future research could validate the model empirically with real-world data from varied global contexts, integrate qualitative factors using mixed-methods, and ease assumptions to boost generalizability and depth.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings15224181/s1, Supplementary Tables: Table S1. Basic information of the case projects; Table S2. Analysis of axial coding and selective coding of urban renewal project information. Supplementary Data: Interview for Research on Stakeholder Conflicts in Urban Renewal Projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Z.; methodology, X.S. and S.L.; software, X.S. and G.D.; validation, S.L.; formal analysis, X.S. and P.C.; investigation, B.Z., X.S. and Y.L.; resources, B.Z.; data curation, X.S.; writing—original draft preparation, X.S. and G.D.; writing—review and editing, S.L., S.L. and P.C.; supervision, B.Z. and Y.L.; project administration, B.Z.; funding acquisition, B.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Anhui Province Federation of Social Science (grant number 2022CX092) and Anhui Jianzhu University (grant number 2022XMK06).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the School of Economics and Management at Anhui Jianzhu University for providing technical support to conduct this research. The authors also acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yildiz, S.; Kivrak, S.; Arslan, G. Factors affecting environmental sustainability of urban renewal projects. Civ. Eng. Environ. Syst. 2017, 34, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Zhang, Q.; Chan, E.H.W. Underlying social factors for evaluating heritage conservation in urban renewal districts. Habitat Int. 2017, 66, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J. Partnership, Collaborative Planning and Urban Regeneration; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, R.; Tallon, A.; Williams, D. Governing urban regeneration in the UK: A case of ‘variegated neoliberalism’ in action? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 1083–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbiboa, D.E. Conflict Analysis in ‘World Class’ Cities: Urban Renewal, Informal Transport Workers, and Legal Disputes in Lagos. In Urban Forum; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 29, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lees, L. The urban injustices of new Labour’s “New Urban Renewal”: The case of the Aylesbury Estate in London. Antipode 2014, 46, 921–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C. Managing for Stakeholders: Reputation, Survival and Success; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, T.; Qian, Q.K.; Visscher, H.J.; Elsinga, M.G. Stakeholders’ Expectations in Urban Renewal Projects in China: A Key Step towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.; Asare, M.H. Fuzzy evaluation of comprehensive benefit in urban renewal based on the perspective of core stakeholders. Habitat Int. 2017, 66, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhu, J.; Duan, M.; Li, P.; Guo, X. Overcoming the Collaboration Barriers among Stakeholders in Urban Renewal Based on a Two-Mode Social Network Analysis. Land 2022, 11, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Mohabir, N.; Ma, R.; Wu, L.; Chen, M. Whose village? Stakeholder interests in the urban renewal of Hubei old village in Shenzhen. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, R. Stakeholder Analysis and Conflict Management; International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hörisch, J.; Schaltegger, S.; Freeman, R.E. Integrating stakeholder theory and sustainability accounting: A conceptual synthesis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 124097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, M.; Ferri, L.M. Stakeholder management: A systematic literature review. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2019, 19, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Y. Exploring the Key Factors Influencing Sustainable Urban Renewal from the Perspective of Multiple Stakeholders. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novais, P.; Carneiro, D. (Eds.) Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Contemporary Conflict Resolution; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Allred, C.B. The anatomy of conflict: Some thoughts on managing staff Conflict. Law Libr. J. 1987, 79, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.; Shen, G.Q.; Shi, Q.; Zheng, H.W.; Wang, G.; Xu, K. Evaluating social sustainability of urban housing demolition in Shanghai, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 153, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Liang, X.; Shen, G.Q.; Shi, Q.; Wang, G. An optimization model for managing stakeholder conflicts in urban redevelopment projects in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Liu, M. Critical barriers and countermeasures to urban regeneration from the stakeholder perspective: A literature review. Front. Sustain. Cities 2023, 5, 1115648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.; Qian, Q.K.; Visscher, H.J.; Elsinga, M.G.; Wu, W. The role of stakeholders and their participation network in decision-making of urban renewal in China: The case of Chongqing. Cities 2019, 92, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tao, Y.; Qian, Q.K.; Mlecnik, E.; Visscher, H.J. Critical factors for effective resident participation in neighborhood rehabilitation in Wuhan, China: From the perspectives of diverse stakeholders. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 244, 105000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. The role and action of the government in Shenzhen’s urban renewal—From benefit sharing to responsibility sharing. Int. Urban Plan. 2011, 26, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.L. Analysis of interest conflict and game in Shanghai urban renewal. City Obs. 2010, 6, 130–141. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, B.K.; Joo, Y.M. Innovation or episodes? Multi-scalar analysis of governance change in urban regeneration policy in South Korea. Cities 2019, 92, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Conejos, S.; Chan, E.H.W. Social needs of the elderly and active aging in public open spaces in urban renewal. Cities 2016, 52, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.; Davies-Slate, S.; Jones, E. The Entrepreneur Rail Model: Funding urban rail through majority private investment in urban regeneration. Res. Transp. Econ. 2018, 67, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Jang, Y. Lessons from good and bad practices in retail-led urban regeneration projects in the Republic of Korea. Cities 2017, 61, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruming, K. Post-political planning and community opposition: Asserting and challenging consensus in planning urban regeneration in Newcastle, New South Wales. Geogr. Res. 2018, 56, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogruyol, K.; Aziz, Z.; Arayici, Y. Eye of Sustainable Planning: A Conceptual Heritage-Led Urban Regeneration Planning Framework. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, S.; Rahimzad, R.; Parsa, A. ‘Smart’sustainable urban regeneration: Institutions, quality and financial innovation. Cities 2015, 48, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantal, B.; Josef, K.; Klusáček, P.; Martinat, S. Assessing success factors of brownfields regeneration: International and inter-stakeholder perspective. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2015, 11, 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.Y.; Bian, W.H. Research on the theory and method of urban renewal in the new era. Urban Archit. Space 2023, 30, 73–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Transformation and development of local government financing platforms in the perspective of urban renewal. China Real Estate 2023, 7, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, D.; Yau, Y.; Bao, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, T. Anatomizing the Institutional Arrangements of Urban Village Redevelopment: Case Studies in Guangzhou, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arch, A.F. Sustainable Urban Renewal: The Tel Aviv Dilemma. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2527–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, G. Key Variables for Decision-Making on Urban Renewal in China: A Case Study of Chongqing. Sustainability 2017, 9, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.F.; Sun, X.M.; Liu, Z. Exploration of consultative planning for development implementation: The case of Shanghai Jiuxing market renewal and redevelopment. J. Urban Plan. 2017, s2, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, D.; Pai, M.; Carrigan, A.; Bhatt, A. Toward people’s cities through land use and transport integration: A review of India’s national urban investment program. Transp. Res. Rec. 2013, 2394, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhou, Y. Fuzzy comprehensive evaluation of urban regeneration decision-making based on entropy weight method: Case study of yuzhong peninsula, China. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2015, 29, 2661–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Tang, B. Institutional barriers to redevelopment of urban villages in China: A transaction cost perspective. Land Use Policy 2016, 58, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, B.; Leng, J.; Ma, J. Investigating the intensive redevelopment of urban central blocks using data envelopment analysis and deep learning: A case study of Nanjing, China. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 109884–109898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yi, Z.; Zhang, X.; Shrestha, A.; Martek, I.; Wei, L. An Evaluation of Urban Renewal Policies of Shenzhen, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.W.; Shen, G.Q.; Wang, H. A review of recent studies on sustainable urban renewal. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooimeijer, F.L.; Maring, L. The significance of the subsurface in urban renewal. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2018, 11, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, G.W.; Liu, G.N.; Yang, Y. Land system problems in urban renewal. China Land. 2021, 4, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.B. Conflict of interest and planning coordination in urban renewal. Mod. City Res. 2011, 26, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, H.P.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Y. Land acquisition conflict and its resolution from the perspective of system adaptation theory-taking land acquisition and resettlement of Beijing New Airport as an example. China Adm. 2017, 12, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, C.M.; Yu, C.Y.; Shao, L.Y. Improving the local wind environment through urban design strategies in an urban renewal process to mitigate urban heat island effects. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2023, 149, 05023003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Shen, G.Q.; Liu, G.; Martek, I. Demolition of Existing Buildings in Urban Renewal Projects: A Decision Support System in the China Context. Sustainability 2019, 11, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, S.; Kivrak, S.; Arslan, G. Contribution of built environment design elements to the sustainability of urban renewal projects: Model proposal. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2019, 145, 04018045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berta, M.; Bottero, M.; Ferretti, V. A mixed methods approach for the integration of urban design and economic evaluation: Industrial heritage and urban regeneration in China. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2018, 45, 208–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trillo, C. Urban Regeneration and New Partnerships Among Public Institutions, Local Entrepreneurs and Communities. In Advanced Engineering Forum; Trans Tech Publications Ltd.: Bäch, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 11, pp. 303–313. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, G.Q. Research on the transformation of dilapidated houses and social governance strategies in the context of urban renewal. Soc. Constr. 2022, 9, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Sun, L.; Chang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Qi, P. How do digitalization capabilities enable open innovation in manufacturing enterprises? A multiple case study based on resource integration perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 184, 122019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintoye, A. Analysis of factors influencing project cost estimating practice. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2000, 18, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Kang, J. Comparison of ecological risk among different urban patterns based on system dynamics modeling of urban development. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2017, 143, 04016034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.J. Spatio-Temporal Changes of Housing Features in Response to Urban Renewal Initiatives: The Case of Seoul. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, M. Well-Being and Fair Distribution: Beyond Cost-Benefit Analysis; OUP USA: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.Y.R.; Chang, J.C. Financialising space through transferable development rights: Urban renewal, Taipei style. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1943–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidemann, V.; Kainer, K.A.; Staudhammer, C.L. Heterogeneity in NTFP quality, access and management shape benefit distribution in an Amazonian extractive reserve. Environ. Conserv. 2014, 41, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).