Developing Design Recommendations for Meditation Centres Through a Mixed-Method Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To identify recurring design practices in existing case studies;

- To synthesise findings into a set of design recommendations.

- To evaluate how the various indoor environmental qualities can affect meditation experiences;

- To establish a hierarchy of the various indoor environmental qualities based on their impact on meditation experiences.

2. Literature Review

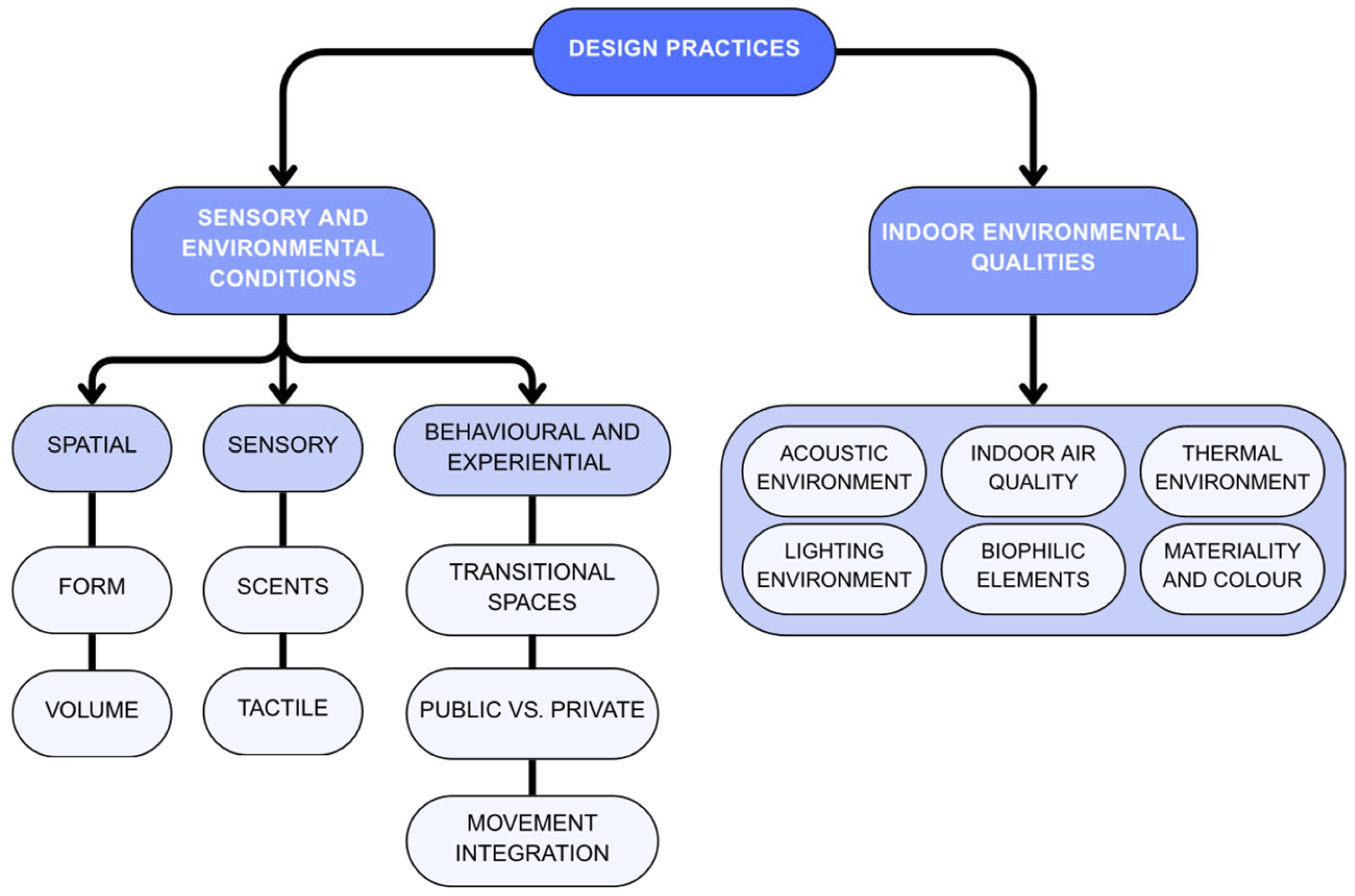

2.1. Sensory and Environmental Conditions

- Thermal environment: Existing research acknowledges the role of thermal comfort on meditation and sustained stillness through physiological parameters, such as skin temperature [27], distraction, and physical strain [28]. However, interaction of thermal comfort with other IEQs is not explored and there is a limited focus on control over thermal environments in response to individual preferences and surrounding climates.

- Acoustic environment: Silence, or non-intrusive and continuous sound, supports focus during meditation [29]. Controlled soundscapes support peaceful socialisation and community building, which is examined through the design of sacred spaces by Medina (2013) [30]. However, there is little empirical evidence comparing sound design strategies across different meditation traditions, especially those that practice chanting in comparison to those that require silence.

- Lighting environment: Natural light is a key element linking meditative spaces to emotional wellbeing. The contrast between light and shadow can generate rhythmic and spiritual atmospheres [31]. Low lighting creates a sense of inward focus [32], and warm lighting promotes a sense of relaxation and social collaboration [33]. Interactions between lighting and other IEQs, such as materiality, colour, and thermal comfort, remain underexplored. Furthermore, the inverse relationship between natural light levels and distraction levels, and individual preferences of darkness are rarely acknowledged.

- Indoor Air Quality (IAQ): Ventilation and odour control for centres that often host large groups of people sitting for several hours are acknowledged as essential [9]. However, the connection between ventilation and fenestration operation could create counterproductive lighting and/or thermal environments, which is underexplored in the context of meditation spaces.

- Materials and Colour: Natural materials can promote warmth and grounding, while creating a connection to nature [28]. Material selection should consider weathering over time and lifecycle analysis for longevity and sustainability [34]. Dematerialisation of the architecture using fenestration can further enhance the connection to the outdoors and bring in daylight [29]. The existing literature suggests that green and blue tones correlate with calmness and have biophilic associations, with an emphasis on intentional hue and saturation selected to avoid overstimulation [31,35]. Such studies are not in the context of meditation centres but can be applied to this research.

2.2. Broader Contexts and Applications

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

- Qualitative exploration: A scoping case study review of global meditation-based projects identified recurring spatial and environmental design practices, while semi-structured interviews with architects, lighting designers, and meditation instructors explored the rationale underpinning these approaches.

- Quantitative assessment: Insights from the qualitative phase directly informed the development of a user survey designed to evaluate perceptions of key IEQs (IAQ, lighting environment, acoustic environment, thermal environment, and biophilia) in meditation centres.

- Synthesis and recommendation formation: The qualitative and quantitative findings were integrated to generate evidence-based design recommendations that promote the creation of healthy, inclusive, and sustainable meditation centres.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3.2.1. Scoping Case Study Review

- Availability of sufficient architectural documentation, including drawings, photographs, and descriptive texts.

- Representation of diverse geographical and cultural contexts, ensuring that various perspectives, climates, traditions, and cultural settings are considered.

- Primary purpose of the project as a space to maintain a focus on spatial qualities rather than traditional or religious affiliations.

- Range of project scales, to examine design practices across different spatial typologies.

3.2.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

- Design decisions made during the project.

- Outcomes and challenges related to IEQs such as acoustics, lighting, air quality, ventilation, thermal comfort, and biophilia.

- Reflections on user feedback and post-occupancy evaluation.

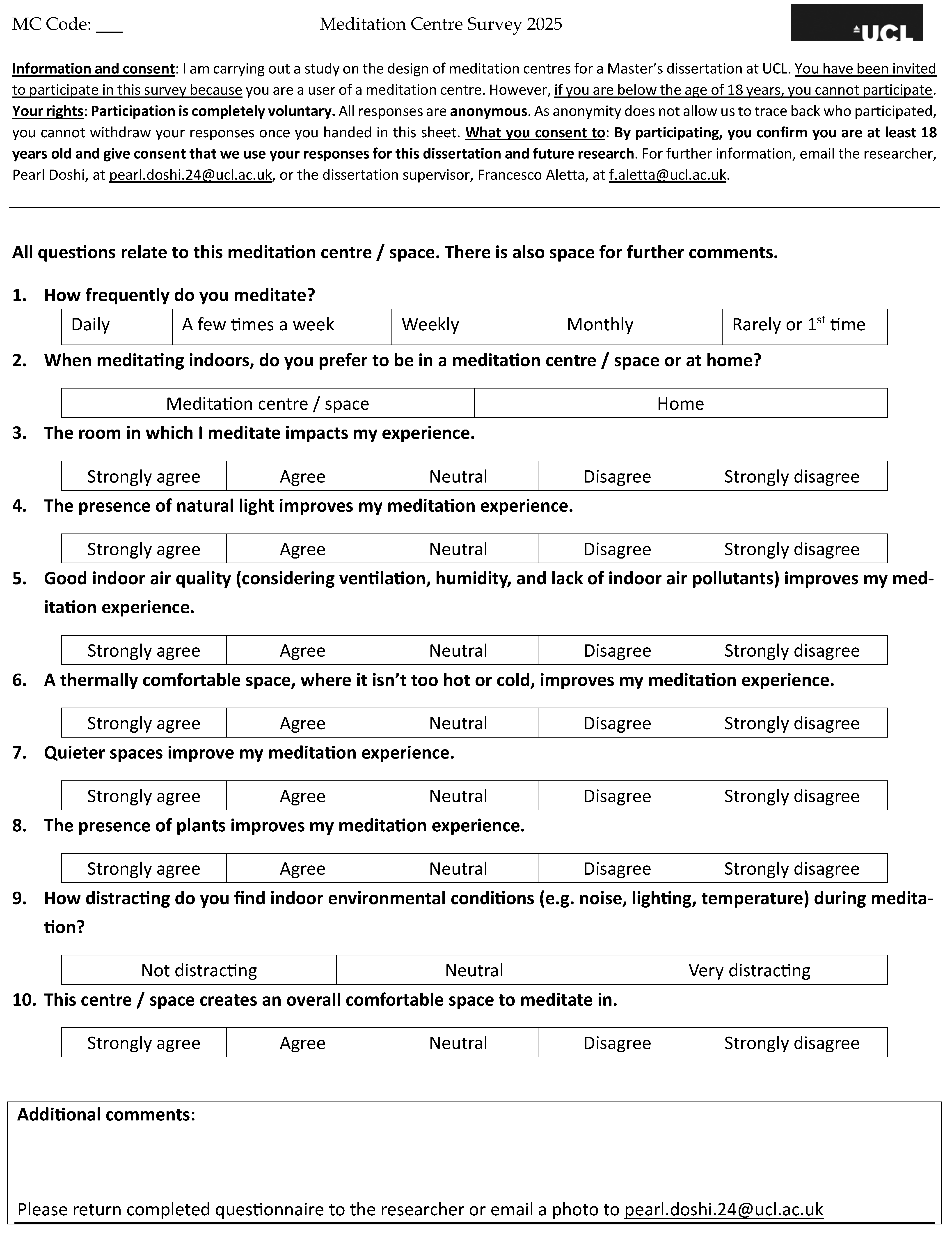

3.2.3. User Surveys

- Collaboration with meditation centres.

- Meditation communities on social media platforms.

- Snowball sampling through survey respondents, with information to ensure only meditation centre users were participating.

3.3. Ethical, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Considerations

4. Results

4.1. Scoping Case Study Results

4.1.1. Quantitative Patterns

4.1.2. Qualitative Patterns

- Geographic and Typological Diversity: Projects were spread across Asia, Europe, and North America, in urban (city-based), suburban (residential outskirts), and rural (countryside) settings. While focused on meditation, uses of the projects ranged from small, single-user pavilions to large, multi-functional retreat centres.

- Material Trends: Natural materials such as timber, bamboo, and stone were prioritised in rural contexts for their thermal and acoustic qualities, and biophilic appeal. Concrete is often used in urban or monumental contexts for durability and controlled acoustics.

- Natural Light: Skylights, roof openings, and glazing are the most common strategies for natural lighting. Rural projects favour open facades, while urban projects rely on controlled apertures for privacy and acoustic buffering. Dappled lighting that mimics a tree’s light filtration is often used for its biophilic appeal and ability to bring in light but limit visual distractions.

- Ventilation and Thermal Environment: Passive strategies, such as open facades, cross ventilation, and shaded courtyards, are favoured in rural settings. Urban or large-scale projects incorporate mechanical systems for consistent comfort, but they need to ensure the systems are quiet.

- Acoustic Environment: Nature-based quietude is a recurring feature in rural settings. Urban projects employ material-based acoustic absorption, sound zoning of sociable and meditative spaces, and landscape buffers.

- Biophilic Integration: Almost all projects demonstrate biophilic principles. Strategies include visual or physical connection to nature, water elements, natural materials, natural soundscapes, or landscaping.

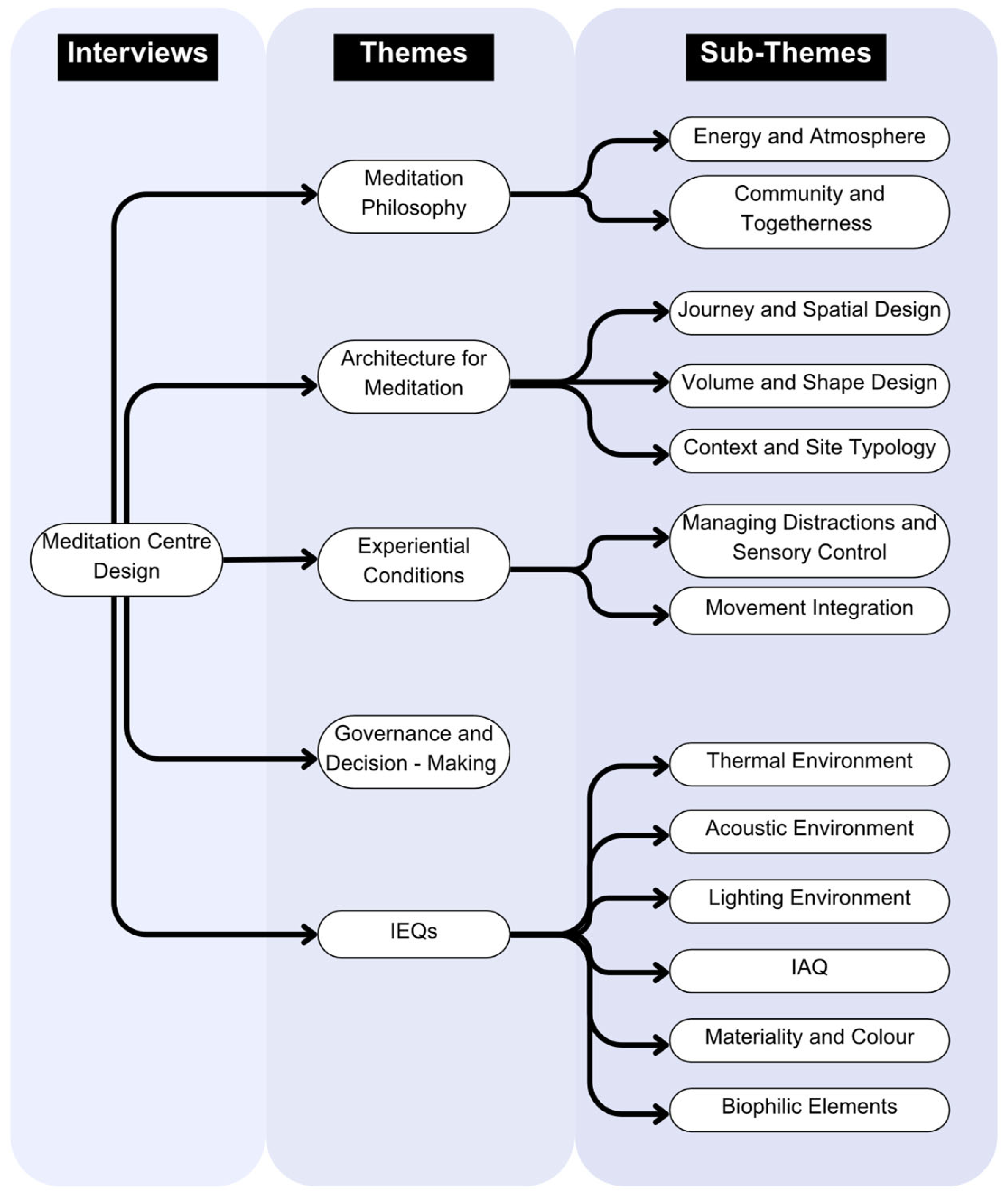

4.2. Interview Results

4.2.1. Theme 1: Meditation Philosophy

4.2.2. Theme 2: Architecture for Meditation

4.2.3. Theme 3: Experiential Considerations

4.2.4. Theme 4: Governance, Decision Making, and Funding

4.2.5. Theme 5: Indoor Environmental Qualities

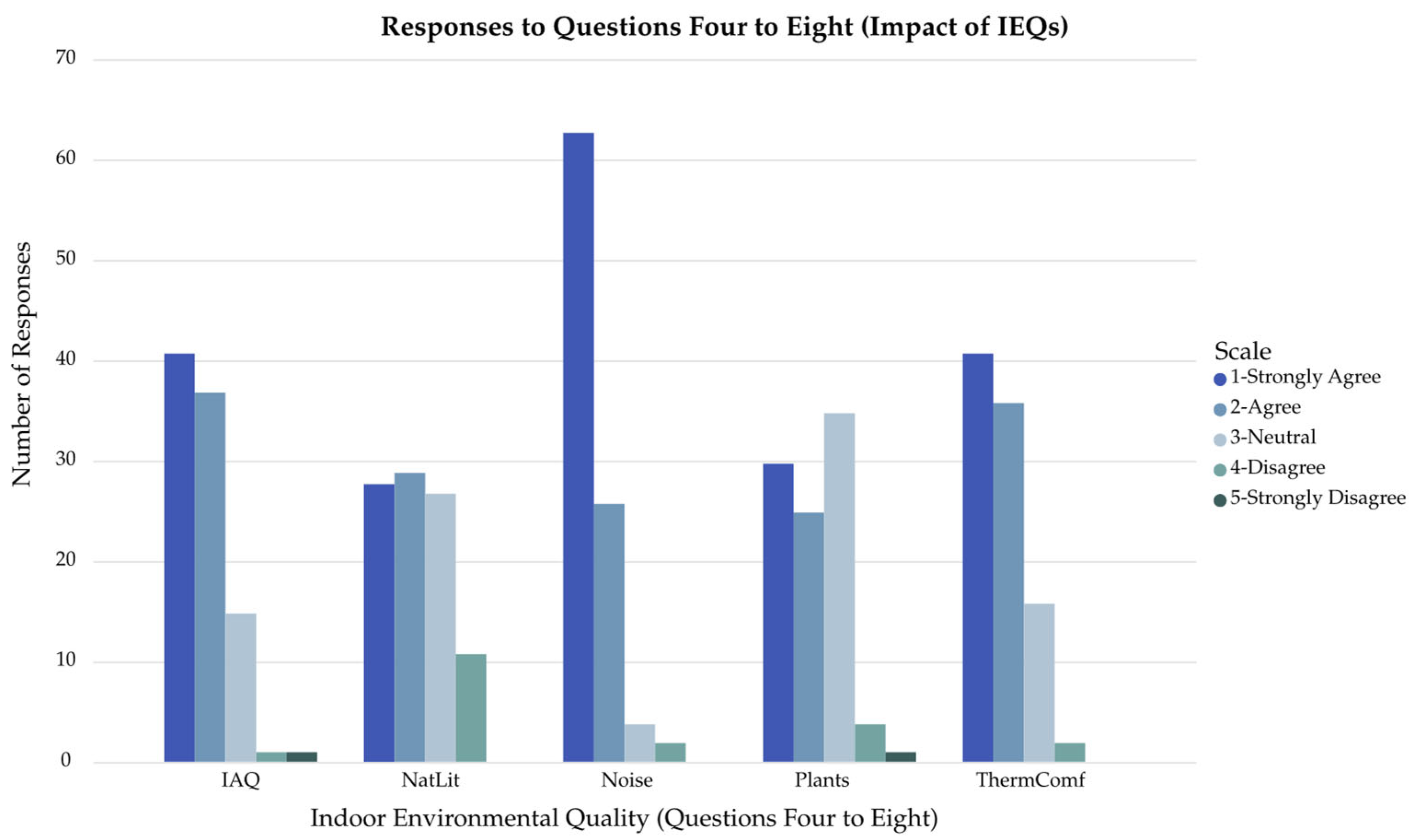

4.3. Survey Results

4.3.1. Descriptive Analysis

- Acoustic environment

- Indoor air quality and thermal environment

- Biophilic elements

- Lighting environment

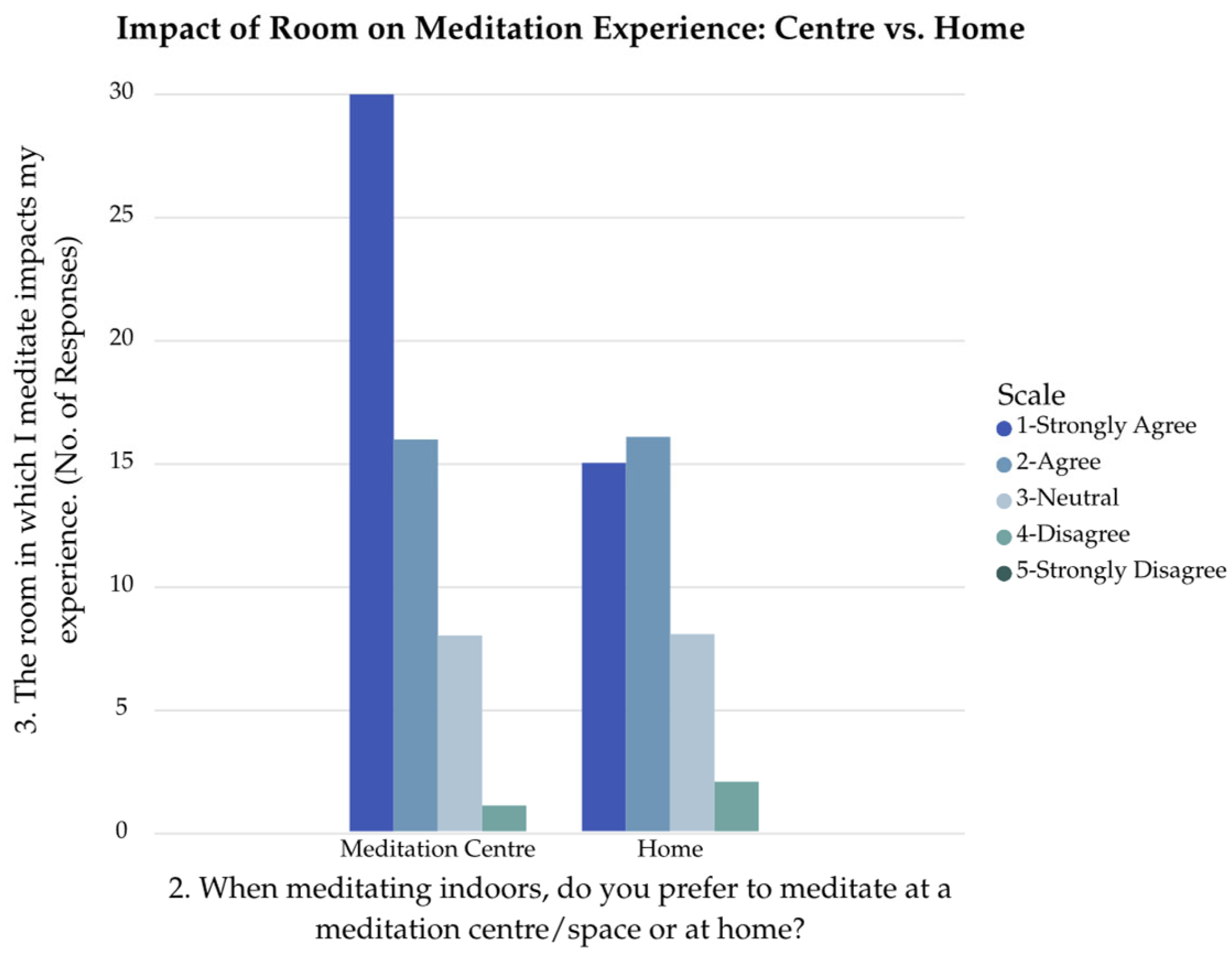

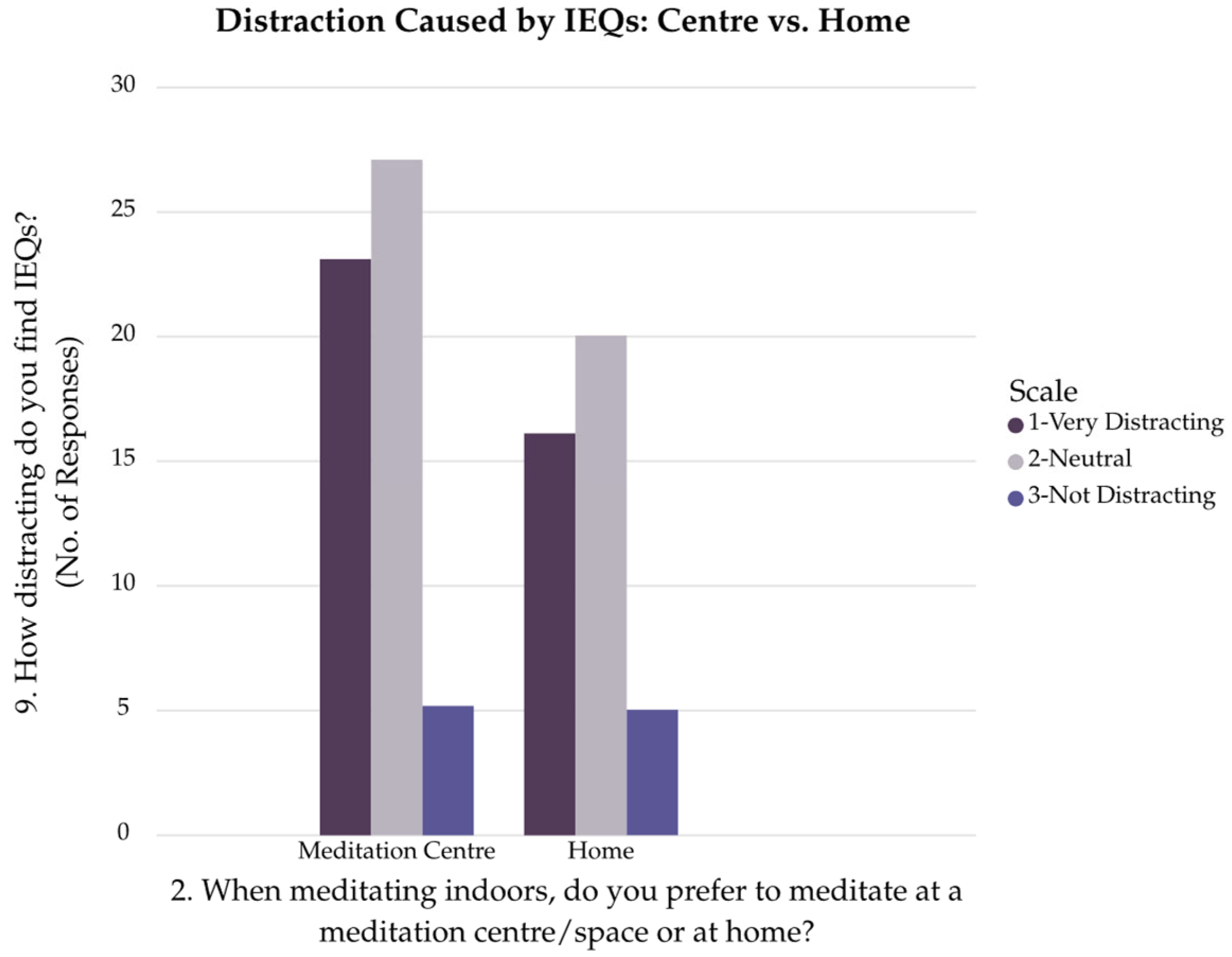

- Meditation Centre group: Most participants strongly agreed, and a smaller proportion agreed that the room impacts their meditation experience. Few participants selected ‘neutral’ or ‘disagree’, and none selected ‘strongly disagree’.

- Home group: Even though they were slightly more spread, the responses were still dominated by ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’. Fewer participants responded ‘strongly agree’ in comparison to the Meditation Centre group. Slightly more participants responded ‘disagree’ in comparison to the Meditation Centre group. No participant responded ‘strongly disagree’.

- Meditation Centre group: The largest share rated IEQ as ‘neutral’, followed closely by ‘very distracting’, with a small number of participants finding it ‘not distracting’.

- Home group: A similar pattern appears but with lower counts for both ‘neutral’ and ‘very distracting’. Few participants find it ‘not distracting’.

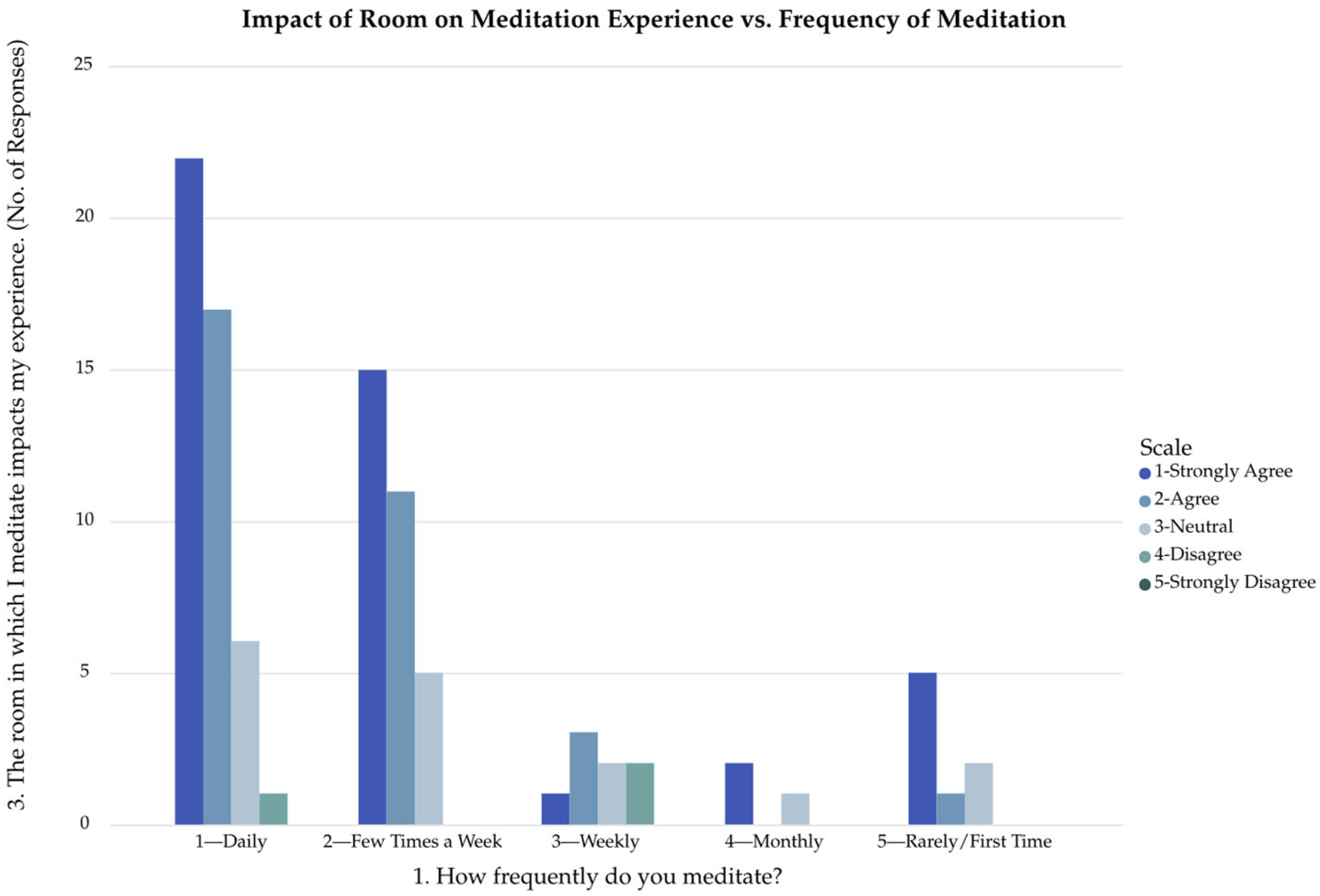

- Daily: Most participants ‘strongly agree’, followed by ‘agree’. Responses for ‘neutral’ and ‘disagree’ are minimal.

- Few times a week: Participants also show high agreement with the most responding ‘strongly agree’, followed by ‘agree’. No one disagreed.

- Weekly: Fewer responses were recorded but they were more evenly split between ‘agree’, ‘neutral’, and ‘disagree’. Fewer people ‘strongly agreed’, which contrasts the results from more frequent meditators.

- Monthly: Meditators are minimal in number. Responses only in ‘strongly agree’ and ‘neutral’.

- Rarely: Meditators lean towards ‘strongly agree’, with smaller numbers in ‘neutral’ and ‘agree’.

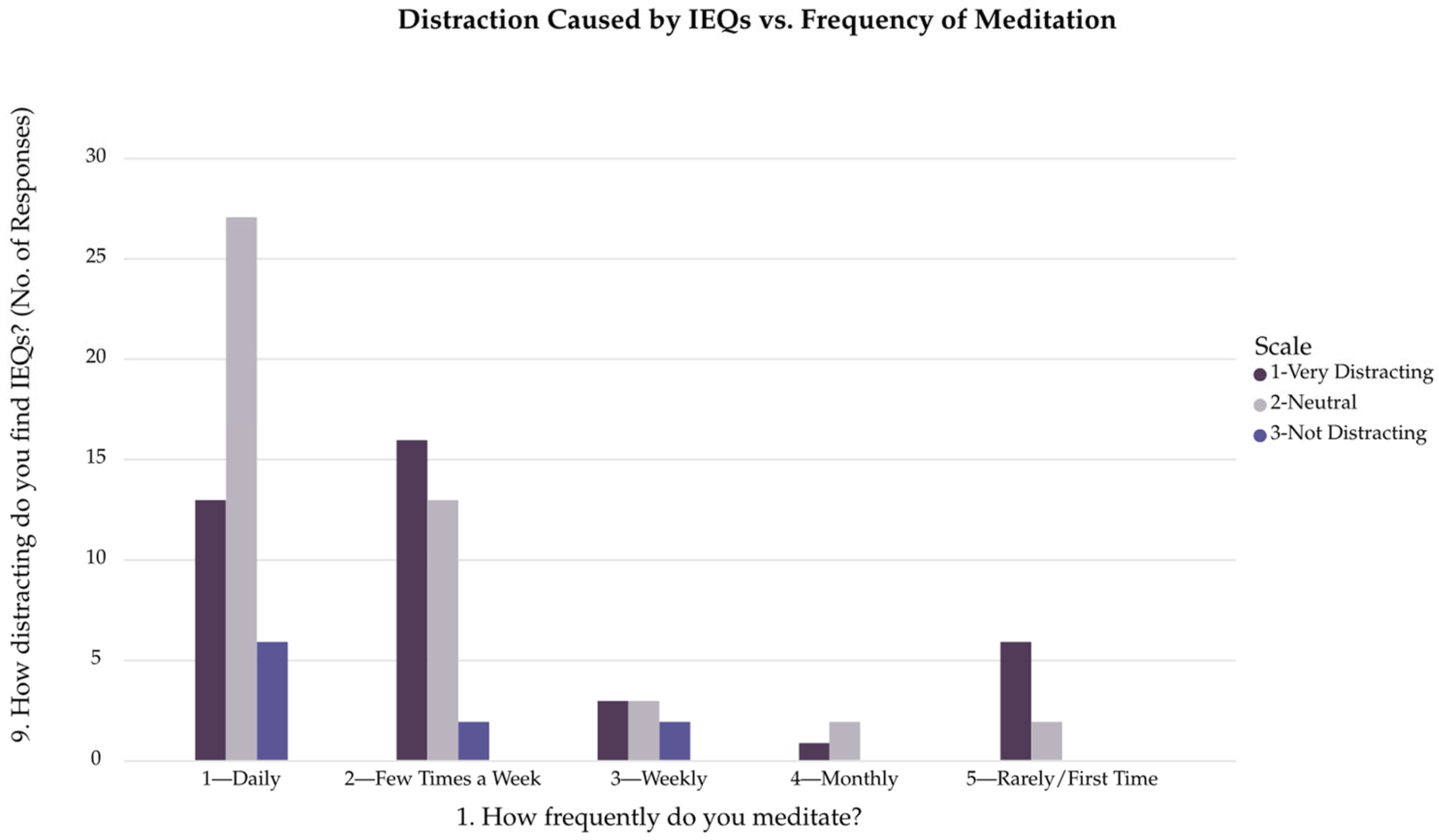

- Daily: Most meditators rated IEQs as ‘neutral’, with a smaller share finding them ‘very distracting’, and very few saying ‘not distracting’.

- Few times a week: Meditators have a more even split between ‘neutral’ and ‘very distracting’, though the latter is slightly higher. Comparatively fewer responses saying IEQs are ‘not distracting’.

- Weekly: There are few but balanced counts across all categories as seen through the more even distribution.

- Monthly: Minimal participants meditate monthly. More responded ‘neutral’ and none responded ‘not distracting’.

- Rarely: Meditators mostly rated IEQs as ‘very distracting’, followed by ‘neutral’. No one responded ‘not distracting’.

- In response to the impact of the room on meditation, daily meditators show the strongest conviction as most responses ‘strongly agree’.

- In response to the distraction caused by IEQs, daily meditators report more ‘neutral’ feelings than responding ‘very distracting’.

4.3.2. Inferential Analysis

4.3.3. Survey Word Mapping

- Noise is a dominant distraction.

- Meditating in a ‘good’ environment is important.

- Thermal comfort and IAQ are critical for crowded centres.

- Lighting needs to be adaptable.

- A natural and muted material and colour palette is preferred.

- Biophilia is most effective when implemented outside the meditation hall, while retaining connection.

- Atmosphere and social dynamics are important.

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Findings and Design Recommendations

- Acoustic environment

- Indoor air quality and thermal environment

- Biophilic elements

- Lighting environment

5.2. Applications of Findings

5.3. Limitations

6. Conclusions

- Acoustic environment

- Indoor air quality and thermal environment

- Biophilic elements

- Lighting environment

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Transcendental Meditation—chanting-based practice

- Mindfulness Meditation—attention to breath sensations

- Sahaja Yoga Meditation—‘thoughtless awareness’

- Religious or Spiritual Traditions—including but not limited to: Buddhist Zen meditation, Christian scripture-based, Hindu and Sufi breath meditation [68], Jain silent meditation [69], etc. For this research, meditation is framed as a secular mindfulness activity that aims to cultivate equilibrium, foster concentration, and promote peace in daily life.

Appendix B

| # | Project | Architect | Location and Year | Area and Capacity | Use | Site Typology | Materials | Natural Light | Electric Light | Ventilation | Thermal Comfort | Acoustic Strategy | Biophilic Elements | Height (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

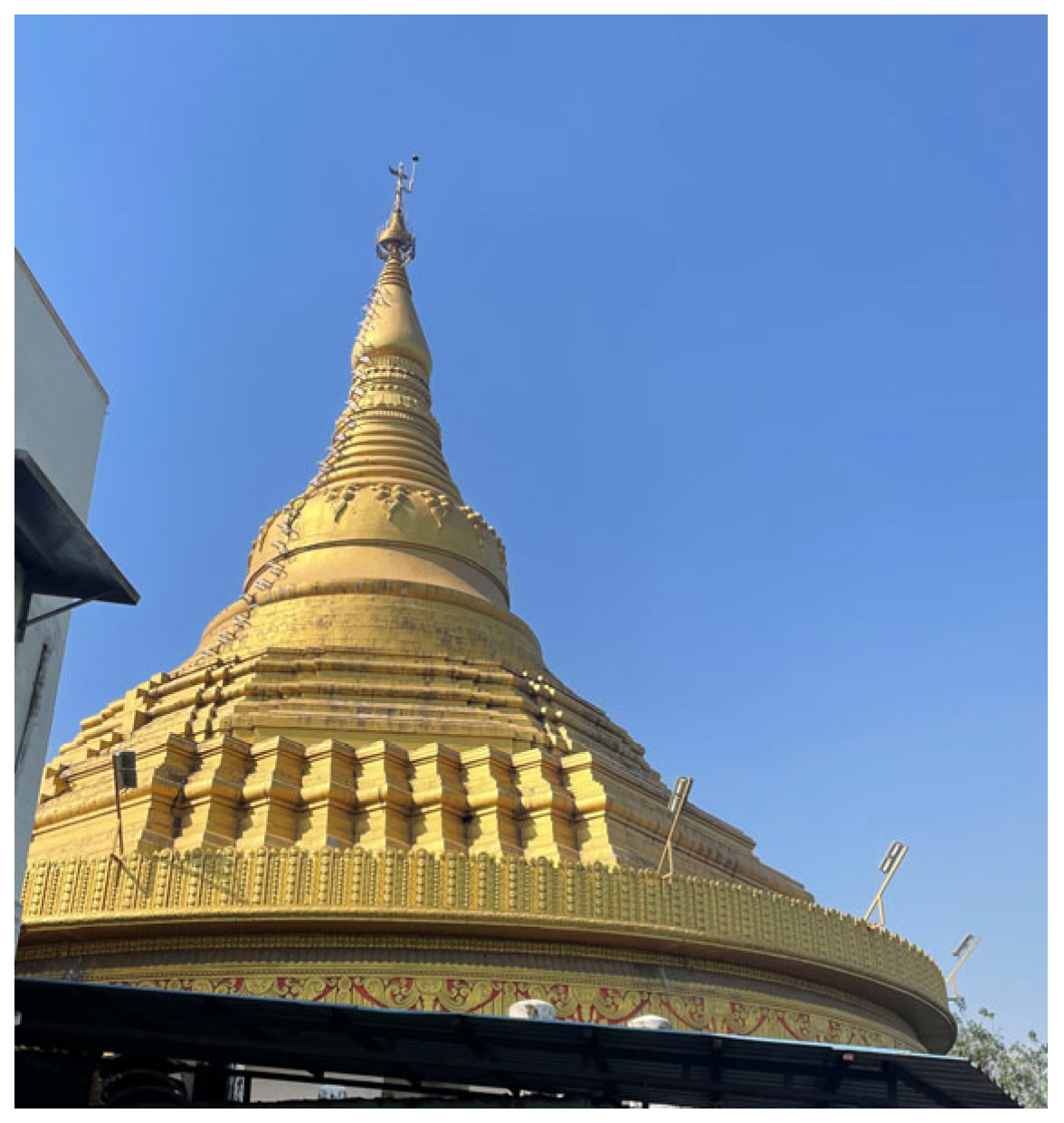

| 1 | Sunset Sala and Meditation Cathedral [71,72,73] | Chiangmai Life Architects | Chiang Mai, Thailand (2018) | 147 m2 | Spiritual practice, meditation | Rural—hillside | Bamboo | Skylights, open facade | Natural | Passive | Quiet by nature of site | Connected to landscape, views, natural materials | - | |

| 2 | Maitrimandir [74,75,76,77] | Roger Anger | Auroville, India (2008) | 1018 m2 | Spiritual practice, meditation | Suburban | White marble, white carpet | Central skylight, heliostat with mirror | Stimulates effect of natural light | Natural | Natural cooling system | Quiet by nature of site | Connected to gardens | 29.5 |

| 3 | Sattrapirom Meditation Centre (Vipassana) [78,79,80] | Ken Lim Architects | Rayong, Thailand (2017) | 1000 m2 | Meditation, accommodation | Rural—grove and orchards | Concrete, cement, brick | Glazing, dim light | - | - | - | Quiet by nature of site | Views to nature | |

| 4 | Bohyun Buddist Meditation Centre [81,82] | Design by 83 | Busan, South Korea (2023) | 270 m2 | Buddhist temple, meditation, education, accommodation | Urban | Wood-coloured metal, granite, timber cladding, paper lanterns, brick | Windows | - | - | - | - | Natural materials | - |

| 5 | Won Dharma [34,83,84] | HanrahanMeyers Architects | New York, United States (2007) | 280 m2, 80 people | Retreat, accommodation, meditation | Rural—hillside | Wood | Southern orientation, filtering screens | Low-voltage fluorescent/LED, solar-powered fluorescent low exterior lighting | Cross ventilation through courtyards | Passive cooling: courtyards, geo-thermal wells, PV, bio-mass boiler, radiant in-floor heating. Spray-foam insulation, low-e glass | Courtyards for silent walking meditation, sound zoning, soundproofed doors, triple glazed windows | Dappled sunlight, natural materials, views to nature, landscape architecture | 7.6 |

| 6 | UNESCO Meditation Space [85,86,87] | Tadao Ando | Paris, France (1995) | 452 m2 | Monument, memorial, meditation | Urban | Exposed concrete, irradiated granite | Opening in roof | - | - | - | - | - | 6 |

| 7 | Windhover, Stanford University [88,89,90,91,92] | Aidlin Darling Design | Stanford University Campus, CA, USA (2014) | 370 m2 | Contemplative centre, art gallery | Urban—university campus | Rammed, dark-stained oak, glazing, cedar slats | Glazing, louvres, skylights | Lutron lighting system, spotlights on art | Sustainable mechanical ventilation | Mechanically heated and cooled radiant flooring system | Ambient sound—fountains | Connected to oak grove, garden, bamboo plants, water acoustics, natural materials | 6.1 |

| 8 | Vajrasana Buddhist Retreat Centre [28,93,94,95] | Walters and Cohen Architects | Suffolk, England (2016) | 130 m2, 60 people | Meditation, accommodation, Buddhist Ordination | Rural—farm | Plywood, painted blockwork, dark brick, charred timber, resin | Perforation in walls | Flexible lighting control, variety of luminaires | - | Heated flooring system | Spray foam treatment on ceiling sound zoning | Dappled sunlight, connected to nature | 8 |

| 9 | Forest Pond House [96,97,98] | TDO Architecture | Hampshire, England (2012) | 6 m2, 1 person | Meditation, children’s den | Rural—forest | Plywood, glass, copper | Open facade | 1 luminaire | Open facade | Open—site responsive | Quiet by nature of site | Connected to landscape | - |

| 10 | Inscape Meditation Studio [99] | Architectonics | New York, United States (2016) | - | Meditation, lounge, retail | Urban | Bamboo | - | Colourful artificial lighting | - | - | - | - | - |

| 11 | Meditation Space for Creation [100] | Jun Murata | Beijing, China (2019) | 78 m2 | Meditation, art gallery | Suburban | Shipping container | Openings in wall | - | - | - | - | Views to nature | - |

| 12 | Yoga dojo [101,102] | MW Architects | Greater London (2019) | 60 m2 | Meditation, yoga (private residence) | Urban—residential | Engineering brick, metal roof grid, charred timber, sedum roof | Open pavilion | - | Open pavilion | - | - | Planted walkway, connected to garden | - |

| 13 | Buddhist Centre for Meditation (Ramagrama Stupa Masterplan) [103,104] | Stefano Boeri Architetti | Ramagrama Parasi District, Nepal (2024) | Masterplan, 1000 people | Meditation, prayer, pilgrimage | Rural—largescale masterplan | Brick | - | - | - | - | Quiet by nature of site | Plantations, connected to meadow, central tree | - |

| 14 | Space of Light (Museum SAN Pavilion) [105,106] | Tadao Ando | Wonju, South Korea (2023) | - | Meditation pavilion | Rural—mountain | Concrete | Opening in roof | - | Opening in roof | - | Quiet by nature of site | - | - |

| 15 | Self Revealing [107,108,109] | StudioX4 | Taipei, Taiwan | - | Urban | - | Mineral paint, laminate flooring, plywood, mirrors, dark colours | Windows | Linear lighting, oculus LED | - | - | Volumetric sound re-direction | Natural materials | Low ceiling |

| 16 | Zenbo Seinei Retreat [110,111] | Shigeru Ban | Awaji Island, Japan (2022) | 648 m2 | Meditation, accommodation, hospitality, restaurant | Rural—ridge | Timber, wood, steel | Openings facades | - | Open facades | Open—site responsive | Quiet by nature of site | Connected to landscape | - |

| 17 | Meditation Hall [112] | Hilarchitects | Cangzhou, China | - | Meditation | Rural | Timber cladding, slate tiles, shallow water walkways | Glazing, lamellas | - | - | - | Quiet by nature of site | Landscaping, views | - |

| 18 | Waterside Buddhist Shrine [113,114,115] | Archstudio | Tangshan, China (2017) | 169 m2 | Buddhist meditation, thinking, and contemplation | Rural—forest, riverside | Concrete, wood, terrazzo, stone, solid wood doors and windows | Large openings, skylights | - | - | - | Quiet by nature of site | Landscaping, courtyards, connected to landscape | - |

| 19 | Lai Yard Meditation Room [116,117] | Ming Gu | Nanjing, China (2017) | - | Meditation | Urban—residential | Glazing, wood | Glazing, blinds | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 20 | Riondolo [118,119] | Giovanni Wegher | Stelvio National Park, Italy (2014) | 7.3 m2, 1 person | Meditation pavilion | Suburban—park | Wood | Small openings | - | Open facades | - | Quiet by nature of site | Connected to landscape, natural materials | 5.2 |

| 21 | Meditation Pavilion and Garden [120,121] | GMAA | Geneva, Switzerland (2013) | - | Meditation pavilion | Suburban | Wood, steel, water body | Skylights | Spotlights | - | - | - | Landscaping, mist | - |

| 22 | Meditation Chambers [122,123] | Office of Things | Bay Area, California, USA (2017) | 9.3 m2 | Meditation | Urban—offices | Soft furniture, mirrors | None | Colourful lighting | - | - | Sensorial sounds | - | Low ceiling |

| 23 | Meditation house in the Forest [123] | Kengo Kuma and Associates and STUDiO LOiS | Krun, Germany (2018) | 141 m2 | Meditation, yoga | Rural—forest | Fir boards, zinc | Small openings | - | - | - | Quiet by nature of site | Dappled light, views to landscape | - |

Appendix C

- Could you outline your professional background and your experience with designing meditation centres?

- How many meditation projects have you worked on and could briefly describe their scales or any particular one that stuck with you?

- What were some of the driving factors for you during the design process for [the project]? Client requirements, site conditions, etc.?

- Did you refer to any design guidelines or requirements when working on [the project]?

- Are there any spatial or environmental features that you consistently incorporate in your design process or any that consistently arise across projects?

- How did you consider indoor environmental qualities such as IAQ, thermal comfort, acoustics, and lighting in the design?

- In your professional opinion, is there a hierarchy of importance between these indoor environmental qualities regarding their impact on meditation experiences?

- Have you engaged with end-users in your design of meditation spaces?

- Have you received feedback on this project post-occupancy? Are there any specific successes? Or areas that require improvement?

- Can you talk about some considerations for inclusivity and sustainability in design decisions?

- In your opinion, what design practices have you found to be supportive for meditation?

- Do you think it’s possible to create a general guideline for meditation spaces, or should they always be context-specific?

Appendix D

References

- Pykett, J.; Osborne, T.; Resch, B. From Urban Stress to Neurourbanism: How Should We Research City Well-Being? Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2020, 110, 1936–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teepe, G.W.; Glase, E.M.; Reips, U.-D. Increasing Digitalization Is Associated with Anxiety and Depression: A Google Ngram Analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Singh, S.; Sibinga, E.M.S.; Gould, N.F.; Rowland-Seymour, A.; Sharma, R.; Berger, Z.; Sleicher, D.; Maron, D.D.; Shihab, H.M.; et al. Meditation Programs for Psychological Stress and Well-Being: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.W.; Cohen, M. A Methodological Review of Meditation Research. Front. Psychiatry 2014, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punwasuponchat, N.; Srichan, P.W. A Study of Forest Dwelling and Meditation Practice. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 58, 10567–10571. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress Recovery During Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.W. The Built Environment and Mental Health. J. Urban Health Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2003, 80, 536–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paiva, A. Neuroscience for Architecture: How Building Design Can Influence Behaviors and Performance. J. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2018, 12, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Horr, Y.; Arif, M.; Katafygiotou, M.; Mazroei, A.; Kaushik, A.; Elsarrag, E. Impact of Indoor Environmental Quality on Occupant Well-Being and Comfort: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2016, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaraman, S. Meditation Research: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2013, 3, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Usen, K.B.; Etuk, A.P.; Sunday, J.R.; Abikoye, G.E. Improving Mental Health Through Meditation Therapy: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2025, 9, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, A.; Slagter, H.A.; Dunne, J.D.; Davidson, R.J. Attention Regulation and Monitoring in Meditation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2008, 12, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanley, A.W.; Dehili, V.; Krzanowski, D.; Barou, D.; Lecy, N.; Garland, E.L. Effects of Video-Guided Group vs. Solitary Meditation on Mindfulness and Social Connectivity: A Pilot Study. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2022, 50, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, D.G.; Teerawattananon, Y.; Anderson, R.; Richardson, G. Generalisability, Transferability, Complexity and Relevance. In Evidence-Based Decisions and Economics; Shemilt, I., Mugford, M., Vale, L., Marsh, K., Donaldson, C., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 56–66. ISBN 978-1-4051-9153-1. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, D.H., Jr.; Walsh, R.N. Meditation: Classic and Contemporary Perspectives; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Matko, K.; Ott, U.; Sedlmeier, P. What Do Meditators Do When They Meditate? Proposing a Novel Basis for Future Meditation Research. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 1791–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, S.; Hu, W.; Yadav, M. Editorial: Effects of Indoor Environmental Quality on Human Performance and Productivity. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 1095443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewomo, M.C.; Toyin, J.O.; Iyiola, C.O.; Aluko, O.R. Synthesis of Critical Factors Influencing Indoor Environmental Quality and Their Impacts on Building Occupants Health and Productivity. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2023, 21, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Essah, E.; Blanusa, T.; Beaman, C.P. The Appearance of Indoor Plants and Their Effect on People’s Perceptions of Indoor Air Quality and Subjective Well-Being. Build. Environ. 2022, 219, 109151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Xu, T. Biophilic Design as an Important Bridge for Sustainable Interaction Between Humans and the Environment: Based on Practice in Chinese Healthcare Space. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 8184534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, K.; Akalin-Baskaya, A.; Hidayetoglu, M.L. Effects of Indoor Color on Mood and Cognitive Performance. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 3233–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. The Interior Experience of Architecture: An Emotional Connection between Space and the Body. Buildings 2022, 12, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, F. The Sense of Place; CBI Publishing Company, Inc.: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Monzavi, F. Meditation Interiors: Exploring Spatial Qualities for Well-Being and Spirituality. Master’s Thesis, Eastern Mediterranean University, Famagusta, Cyprus, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, T.; Matthews, J.R.; Chambers, R.; Windt, J.; Hohwy, J. Changes in Multisensory Integration Following Brief State Induction and Longer-Term Training with Body Scan Meditation. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 1214–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, N. Sensory Meditation Center: Es-Sense-Tial Ab-Sense. Master’s Thesis, School of Design Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Manocha, R.; Black, D.; Spiro, D.; Ryan, J.; Stough, C. Changing Definitions of Meditation—Is There a Physiological Corollary? Skin Temperatures Changes of a Mental Silence Oriented Form of Meditation Compared to Rest. J. Int. Soc. Life Inf. Sci. 2010, 28, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, C. Rethinking the Pavilion: Shared Experience at the Vajrasana Buddhist Retreat Centre. Ph.D. Thesis, University College London, London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, A.M. Places of Contemporary Sacred Architecture: Light Media Versus Time of Meditation. EN BLANCO 2013, 11, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xu, Y. The Use of Natural Light and Color in Meditation Spaces—An Application in a Pavilion in China. Master’s Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tomassoni, R.; Galetta, G.; Treglia, E. Psychology of Light: How Light Influences the Health and Psyche. Psychology 2015, 06, 1216–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, G.C. The Effects of Lighting Design on Mood, Attention, and Stress. Ph.D. Thesis, Reed College, Portland, OR, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wing, S. Designing Sacred Spaces, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-315-79822-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, N.; Epps, H. Relationship Between Colour and Emotion: A Study of College Students. Coll. Stud. J. 2004, 38, 396–405. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. Architecture as Stress Relief: What Makes a Meditative Space? Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AE, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, G. Atmospheric Architectures; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.J. The Theory of Affordances; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Zumthor, P. Atmospheres: Architectural Environments—Surrounding Objects; Birkhauser: Basel, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rotondi, M.; Stevens, C.P. RoTo Works: Still Points; Rizzoli International Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-8478-2813-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, E. Healing Spaces: The Science of Place and Well-Being; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-674-05466-0. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A.S. Healing Architecture in Meditation Spaces. Integral Univ. Lucknow 2024, 10, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronel, N.; Frid, N.; Timor, U. The Practice of Positive Criminology: A Vipassana Course in Prison. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2013, 57, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Ugwudike, P.; Young, H.; Hurrell, C.; Raynor, P. A Pragmatic Study of the Impact of a Brief Mindfulness Intervention on Prisoners and Staff in a Category B Prison and Men Subject to Community-Based Probation Supervision. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2021, 65, 136–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.-N.; Gu, J.-W.; Huang, L.-J.; Shang, Z.-L.; Zhou, Y.-G.; Wu, L.-L.; Jia, Y.-P.; Liu, N.-Q.; Liu, W.-Z. Military-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Mindfulness Meditation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2021, 24, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisner, B.L.; Jones, B.; Gwin, D. School-Based Meditation Practices for Adolescents: A Resource for Strengthening Self-Regulation, Emotional Coping, and Self-Esteem. Child. Sch. 2010, 32, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McComas, A. The Rhetoric of Space and How It Applies to Yoga and Meditation. J. Undergrad. Res. Writ. Rhetor. Digit. Humanit. 2021, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Vohra-Gupta, S.; Russell, A.; Lo, E. Meditation: The Adoption of Eastern Thought to Western Social Practices. J. Relig. Spiritual. Soc. Work Soc. Thought 2007, 26, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; SAGE: London, UK, 2011; Volume 457. [Google Scholar]

- Gogo, S.; Musonda, I. The Use of the Exploratory Sequential Approach in Mixed-Method Research: A Case of Contextual Top Leadership Interventions in Construction H&S. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 7276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanto, P.C.; Arini, D.U.; Marlita, D.; Yuntina, L. Mixed Methods Research Design Concepts: Quantitative, Qualitative, Exploratory Sequential, Exploratory Sequential, Embedded and Parallel Convergent. Int. J. Adv. Multidiscip. 2024, 3, 471–485. [Google Scholar]

- ArchDaily. Broadcasting Architecture Worldwide. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Dezeen Magazine. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Designboom Magazine. Your First Source for Architecture, Design & Art News. Available online: https://www.designboom.com/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Architizer: Inspiration and Tools for Architects. Available online: https://architizer.com/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Cimadomo, G.; Rubio, R.G.; Aswani, V.S. Towards a (New) Architectural History for a Digital Age. Archdaily as a Dissemination Tool for Architectural Knowledge. 2018. Available online: https://riuma.uma.es/xmlui/handle/10630/15589 (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Knettig, S. Influential Keys to a Successful Architectural Office in the Euro American Context. Master’s Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2022. TU Delft Repository. Available online: https://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:7cc59e9a-5e67-4f52-8781-e2f0d79658e2 (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorussen, H.; Lenz, H.; Blavoukos, S. Assessing the Reliability and Validity of Expert Interviews. Eur. Union Polit. 2005, 6, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye-Olatunde, O.A.; Olenik, N.L. Research and Scholarly Methods: Semi-structured Interviews. JACCP J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 4, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruslin, R.; Mashuri, S.; Rasak, M.S.A.; Alhabsyi, F.; Syam, H. Semi-Structured Interview: A Methodological Reflection on the Development of a Qualitative Research Instrument in Educational Studies. IOSR J. Res. Method Educ. 2022, 12, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Nyanchoka, L.; Tudur-Smith, C.; Porcher, R.; Hren, D. Key Stakeholders’ Perspectives and Experiences with Defining, Identifying and Displaying Gaps in Health Research: A Qualitative Study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e039932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson-Lastad, A.; Hussein, S.N.; Harrison, J.M.; Zhang, X.J.; Ikeda, M.P.; Chao, M.T.; Adler, S.R.; Weng, H.Y. “May We Be the Bridge and Boat to Cross the Water”: Community-Engaged Research on Metta Meditation. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, L. Acoustic Information Masking Effects of Natural Sounds on Traffic Noise Based on Psychological Health in Open Urban Spaces. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1031501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradiezatpanah, T. The Affect of Architecture: Details for Meditation and Well-Being (Respite Time for the Ottawa Rehabilitation Centre). Ph.D. Thesis, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, J. Architecture: The Subject Is Matter; Psychology Press: Oxfordshire, UK, 2001; ISBN 978-0-415-23545-7. [Google Scholar]

- Sezer, M. Meditational Examination of the Concepts of Sufi Breath Practice Habs-I-Dam and Hindu Breath Practice Kevalakumbaka. Rev. J. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2022, 47, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, S. Bahubali, Watercolour on paper; Victoria and Albert Museum: London, UK, 2018.

- Matko, K.; Sedlmeier, P. What Is Meditation? Proposing an Empirically Derived Classification System. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamboo Meditation Cathedral & Sunset Sala by Chiangmai Life Architects in Thailand. Available online: https://architizer.com/projects/bamboo-meditation-cathedral-sunset-sala/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Abdel, H. Meditation Cathedral & Sunset Sala/Chiangmai Life Architects. ArchDaily, 12 December 2020. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/953123/meditation-cathedral-and-sunset-sala-chiangmai-life-architects (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Ranjit, J. The Sunset Sala & Meditation Cathedral by Chiangmai Life Architects. Parametric Architecture, 25 December 2020. Available online: https://parametric-architecture.com/the-sunset-sala-meditation-cathedral-created-in-bamboo-by-chiangmai-life-architects/?srsltid=AfmBOorNTp2WQ6O_vgzFr42kTe1mO2PZV-9MJ4cupD0TvqF5BU21AeN4 (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- AWARE The Matrimandir: A Symbol of Auroville’s Spiritual Aspirations and Inner Quest. Available online: https://awareauroville.com/the-matrimandir-a-symbol-of-aurovilles-spiritual-aspirations-and-inner-quest/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Aware Auroville. Architectural Marvel: The Design and Symbolism of the Matrimandir. 2023. Available online: https://awareauroville.com/architectural-marvel-the-design-and-symbolism-of-the-matrimandir/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Gilles, G. Brief History of Matrimandir’s Conception|Auroville. Available online: https://auroville.org/page/brief-history-of-matrimandir’s-conception (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Bahga, S. A Modern Temple For All Religions: Roger Anger-Designed Matrimandir in Auroville. World Architecture Community, 12 May 2017. Available online: https://worldarchitecture.org/articles/cvcep/a_modern_temple_for_all_religions_roger_angerdesigned_matrimandir_in_auroville.html (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Castro, F. Gallery of Sattrapirom Meditation Center / Ken Lim Architects—23. ArchDaily, 6 April 2018. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/891945/sattrapirom-meditation-center-ken-lim-architects/5ac520cbf197cca45f000534-sattrapirom-meditation-center-ken-lim-architects-2nd-floor-plan (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- ASACREW Sattrapirom Meditation Center สถานปฏิบัติธรรมศรัทธาภิรมย์. ASA Journal, 11 September 2019. Available online: https://asajournal.asa.or.th/sattrapirom/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Sattrapirom Meditation Center/Ken Lim Architects. ArchDaily, 6 April 2018. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/891945/sattrapirom-meditation-center-ken-lim-architects (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Griffiths, A. Design by 83 Creates “Simple and Contemporary” Busan Meditation Centre. Dezeen, 29 July 2024. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2024/07/29/design-by-83-buddhist-meditation-centre-busan/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- The Buddhist Temple, Gone Modern: A Busan Meditation Centre Appeals to Urbanites. Frame, 3 September 2024. Available online: https://frameweb.com/article/institutions/the-buddhist-temple-gone-modern-a-busan-meditation-centre-appeals-to-urbanites (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Hanrahan Meyers Architrcts Design Is a Frame to Nature. Available online: https://hanrahanmeyers.com/sacred_won.html (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Won Dharma/hanrahanMeyers Architects. ArchDaily, 13 May 2013. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/371099/won-dharma-hanrahan-meyers-architects (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- UNESCO Meditation Space. Architectuul, 15 August 2013. Available online: https://architectuul.com/architecture/unesco-meditation-space (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Frearson, A. Tadao Ando’s Meditation Space Captured in New Photographs by Simone Bossi. Dezeen, 27 April 2020. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2020/04/27/tadao-ando-meditation-space-photos-simone-bossi/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Sanyal, M. Meditation Space by Tadao Ando. RTF Rethink. Future, 2021. Available online: https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/designing-for-typologies/a4227-meditation-space-by-tadao-ando/#google_vignette (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Windhover Contemplative Center/Aidlin Darling Design. ArchDaily, 18 March 2015. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/608268/windhover-contemplative-center-aidlin-darlin-design (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Windhover Contemplative Center. Available online: https://www.rammedearthworks.com/windhover-contemplative-center (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Windhover Contemplative Center—Loisos + Ubbelohde. Available online: https://coolshadow.com/project/windhover-contemplative-center/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Stanford Windhover Contemplative Center. SC Build Inc. Available online: https://www.scbuildersinc.com/projects/stanford-windhover-contemplative-center/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- McKnight, J. Aidlin Darling Uses Rammed Earth for Stanford Meditation Centre. Dezeen, 23 May 2016. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2016/05/23/aidlin-darling-design-windhover-spiritual-meditation-centre-stanford-university-california-rammed-earth-walls/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Griffiths, A. Walters & Cohen Architects Create Buddhist Retreat in Rural England. Dezeen, 26 November 2016. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2016/11/26/walters-cohen-architects-buddhist-retreat-meditation-suffolk-england-farm/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Walters & Cohen Architects. Vajrasana Buddhist Retreat Centre—Projects. Available online: https://www.waltersandcohen.com/projects/vajrasana-buddhist-retreat-centre (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Spiers Major Light Architecture. Available online: https://smlightarchitecture.com/projects/1763/vajrasana-buddhist-retreat-centre-suffolk (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Forest Pond House / TDO Architecture. ArchDaily, 11 February 2013. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/330969/forest-pond-house-tdo-architecture (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Frearson, A. The Forest Pond House Folly by TDO. Dezeen, 5 February 2013. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2013/02/05/forest-pond-house-folly-tdo/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Forest Pond House. Available online: https://www.new-works.net/forest-pond-house (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Inscape Meditation Studio|Archi-Tectonics. Available online: https://archello.com/project/inscape-meditation-studio (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Abdel, H. Meditation Space for Creation/Jun Murata/JAM. ArchDaily, 14 March 2020. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/935462/meditation-space-for-creation-jam (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Yoga Dojo. Available online: https://www.mwarchitects.co.uk/yogadojo (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- ArchEyes Yoga Dojo: A Garden Pavilion Integrating Precision Engineering and Nature. ArchEyes, 21 January 2025. Available online: https://archeyes.com/yoga-dojo-a-garden-pavilion-integrating-precision-engineering-and-nature/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Ramagrama Stupa|Lumbini. Stefano Boeri Architetti. Available online: https://www.stefanoboeriarchitetti.net/en/project/ramagrama-stupa-lumbini/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Fakharany, N. Stefano Boeri Architetti Designs Buddhist Center for Meditation in Nepal. ArchDaily, 18 December 2023. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/1011237/stefano-boeri-architetti-designs-buddhist-center-for-meditation-in-nepal (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Petridou, C. Tadao Ando Inserts “a Space of Light” into Museum SAN’s Premises in South Korea. Design Boom, 1 August 2023. Available online: https://www.designboom.com/architecture/tadao-ando-space-of-light-museum-san-premises-south-korea-08-01-2023/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Crook, L. Tadao Ando Adds Space of Light to Museum SAN in South Korea. Dezeen, 18 August 2023. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2023/08/18/tadao-ando-space-of-light-museum-san/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Lee, Y.-H. StudioX4 Designs Cavernous Meditation Space in Downtown Taipei. Design Boom, 1 October 2024. Available online: https://www.designboom.com/architecture/circular-skylight-cave-like-meditation-space-studio-x4-taipei-10-01-2024/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Self Revealing | StudioX4. Available online: https://archello.com/project/self-revealing (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- StudioX4. Circular Skylight Illuminates Cave-like Meditation Space by Studio X4 in Taipei. AllCADBlocks, 1 October 2024. Available online: https://www.allcadblocks.com/circular-skylight-illuminates-cave-like-meditation-space-by-studio-x4-in-taipei/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Petridou, C. Shigeru Ban Completes Wooden Zenbo Seinei Retreat on Japanese Island. Design Boom, 14 July 2022. Available online: https://www.designboom.com/architecture/shigeru-ban-zenbo-seinei-wellness-retreat-awaji-island-07-14-2022/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Crook, L. Shigeru Ban Designs Meditation Retreat Overlooking Awaji Island Mountains. Dezeen, 4 March 2022. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2022/03/04/shigeru-ban-zenbo-seinei-awaji-island/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Levy, N. Hilarchitects Completes Contemplative Meditation Hall in Eastern China. Dezeen, 8 May 2019. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2019/05/08/hall-meditation-spaces-interiors-hilarchitects-china/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Waterside Buddhist Shrine by ARCHSTUDIO. Available online: https://architizer.com/projects/waterside-buddhist-shrine/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Han, W.-Q. Archstudio Embeds Buddhist Shrine within the Riparian Landscape of Hebei, China. Design Boom, 9 May 2017. Available online: https://www.designboom.com/architecture/archstudio-waterside-buddhist-shrine-china-05-09-2017/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Griffiths, A. Arch Studio Carves Concrete Buddhist Shrine into a Grassy Mound in Hebei. Dezeen, 10 May 2017. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2017/05/10/arch-studio-concrete-buddhist-shrine-subterranean-underground-grassy-mound-hebei-china/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- LAI Yard | Minggu Design. Available online: https://archello.com/project/lai-yard (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Fison, L. A Glazed Meditation Room Overlooks Traditional Courtyard in Nanjing Home. Dezeen, 8 June 2017. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2017/06/08/glass-meditation-room-house-extension-gabled-courtyard-nanjing-china/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Mairs, J. Mobile Meditation Pavilion by Giovanni Wegher Stands on a Lake Shore in Northern Italy. Dezeen, 25 September 2016. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2016/09/25/mobile-meditation-pavilion-riondolo-giovanni-wegher-stelvio-national-park/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Riondolo by Giovanni Wegher. Available online: https://architizer.com/projects/riondolo/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Buildner Large and Small Scale Meditation Spaces. Available online: https://architecturecompetitions.com/large-and-small-scale-meditation-spaces/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Howarth, D. GMAA’s Meditation Pavilion and Garden Creates a Contemplative Atmosphere at Swiss Home. Dezeen, 19 September 2016. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2016/09/19/gm-architectes-associes-meditation-pavilion-garden-architizer-2016-a-awards-geneva-switzerland/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Iype, J. Sublime Coves of Wellbeing Within Offices: Meditation Chambers by Office of Things. Stir World, 1 February 2021. Available online: https://www.stirworld.com/see-features-sublime-coves-of-wellbeing-within-offices-meditation-chambers-by-office-of-things (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Levy, N. Meditation Chambers by Office Of Things Wash Workers in Colourful Light. Dezeen, 13 December 2020. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2020/12/13/meditation-room-interiors-offices/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Ott, C. Meditation House in the Forest/Kengo Kuma & Associates + STUDiO LOiS 2025. ArchDaily, 19 April 2019. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/915445/wood-pile-kengo-kuma-and-associates (accessed on 23 August 2025).

| Participant Code | Region | Expertise and Relevance | Years of Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| P01 | Portugal | Meditation instructor | 15 |

| P02 | UK | Architect—design of meditation retreat centre and supporting research endeavors | 30 |

| P03 | UK | Lighting designer—lighting design for the retreat centre designed by P02. | 20 |

| P04 | India | Architect and urban planner | 35 |

| P05 | India | Architect—completed nine spiritual and meditation-based projects. | 20 |

| P06 | UK | Project management/Member of development committee for a meditation tradition | 10/5 |

| P07 | UK | Owner and manager of a meditation centre | 15 |

| Category | Quantitative Pattern | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean area (m2) | 299 | |||

| Average space per meditator (m2) | 4.7 | |||

| Site typology | 47.8% rural | Site typology | 47.8% Rural | |

| Common materials | 52.2% wood/timber | 17.4% brick | 17.4% concrete | 13% others |

| Natural light | 87% mention daylighting strategies | 13% do not mention natural light strategies | ||

| 34.8% glazing | 30.4% skylights/roof openings | 17.4% open facades | 17.4% filtered light | |

| Ventilation | 34.8% mention natural ventilation | 65.2% do not mention natural ventilation | ||

| Acoustics | 47.8% are quiet by nature of the site | 21.7% implement acoustic strategies | 30.5% do not mention acoustic strategies | |

| Biophilic elements | 78.2% mention biophilic elements such as connection to nature, natural materials, and landscaping | 21.8% do not mention biophilic elements | ||

| Theme, Subtheme | Excerpt from Interviews | Source |

|---|---|---|

| T01, ST01 | “Creating the right atmosphere is probably the most important part. When you walk in, you think, ‘okay, I can be in this place for the next six hours…and it’s going to support me in this practice.’” | P02 |

| T01, ST02 | “The moment you have a living guru and you’re in that room, you close your eyes to meditate, and you feel his energy all around. Which is why when people say they meditate in groups, it’s the group energy.” | P01 |

| Theme, Subtheme | Excerpt from Interviews | Source |

|---|---|---|

| T02, ST01 | Giving your eyes time to adapt to the lighting “helps create that setting and the anticipation of going into a room, allow you to slowly calm down before entering and when you’re leaving.” | P03 |

| T02, ST01 | “…the general signage around the centre and directional signage to get you from place to place. When you get those little details right, it just makes such a difference.” | P02 |

| T02, ST02 | “I think you want to be in a space that has a bit of height so that you don’t feel that there is an oppressively low ceiling… It’s quite nice to have a bit of volume and feel that you are in a space that’s got a bit of generosity.” | P02 |

| T02, ST03 | “One solution is not possible everywhere. It can’t be a prototype because every context is different.” | P05 |

| Theme, Subtheme | Excerpt from Interviews | Source |

|---|---|---|

| T03, ST01 | “Overdesigning is actually frowned upon a little bit… It’s distracted. This is quite an austere practice.” | P06 |

| T03, ST01 | “Your memory and senses are an important part when you close your eyes.” | P05 |

| T03, ST01 | “Any noise that has direct meaning, like music or talking, is more distracting than something like traffic noise.” | P07 |

| T03, ST02 | “The shrine room has a huge set of double doors that open to the courtyard and that courtyard’s got a stupa in it. You can circumambulate, as they call it, the stupa in a puja ceremony or in a walking meditation. So, the idea of being able to go from a seated, still form of practice to a walking, a moving kind of practice, whether it is yoga or walking, is important as well.” | P02 |

| Theme, Subtheme | Excerpt from Interviews | Source |

|---|---|---|

| T04 | “I believe that the reason it was a success is that it was a real collaboration, a really true collaboration between us and them.” | P02 |

| T04 | “We don’t have that much funding so the materials choices we make is the biggest thing, and how you exhaust your buildings.” | P04 |

| T04 | “So, we make decisions on the bases of the [development] committee, and we take it to the trust, and they make the fundamental decision.” | P06 |

| Theme, Subtheme | Excerpt from Interviews | Source |

|---|---|---|

| T05, ST01 | “Being distracted by things like being too cold or too hot or having air blowing on you are unnecessary…Being in a neutral environment that is where you are not overstimulated.” | P02 |

| T05, ST02 | When experiencing a space “you feel that there is a silence even though there is chaos or something is happening. That quality is very important.” | P05 |

| T05, ST02, ST03 | “…keeping [the light source] very concealed. So, there’s nothing in your peripheral vision…and as quiet as possible in terms of the lighting equipment.” | P03 |

| T05, ST03 | “Quite often, some people prefer not very much light at all…” | P03 |

| T05, ST03, ST06 | “A meditation centre needs to manage that access to sunlight and daylight aspects to…minimise the harshness of having solar gain from it.” | P03 |

| T05, ST04 | “Volumetrically, if you design and provide different levels of openings, for circulation, it gives you a benefit. When we are always sitting on the floor, if you can provide an opening 6–9 inches from the ground and at the same time, if you can provide ventilation openings in the upper level, it can be an exhaust.” | P04 |

| T05, ST04 | “We’ve had a lot of conversations about air quality and how fast air needs to be transmitted. It’s a very important factor when you put a large amount of people in a place.” | P06 |

| T05, ST01, ST05 | “What’s on the floor? Because you spend a lot of time on the floor, so we had a timber floor with underfloor heating.” | P02 |

| T05, ST05 | “I personally feel that if you can use locally available materials, it has more benefits and more thermal properties than [imported] materials.” | P04 |

| T05, ST06 | “We should design our indoor space to have the quality of the forest, of riverbanks, or outdoor feelings. All things, all senses are required more than just making it calm physically.” | P05 |

| T05, ST06 | “You want as little distraction as possible, in the case of noises… but you don’t want it to be any more artificial than it has to be… we want to be connected, not disconnected.” | P07 |

| Frequency of Meditation | % of Responses |

|---|---|

| Daily | 47.9% |

| A few times a week | 32.2% |

| Weekly | 8.3% |

| Monthly | 3.1% |

| Rarely or first time | 8.3% |

| Preference of Meditation Space | % of Responses |

|---|---|

| Meditation Centre/Space | 57.3% |

| Home | 42.7% |

| Natural Light | IAQ | Thermal Comfort | Noise | Plants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 2.24 | 1.79 | 1.79 | 1.42 | 2.17 |

| Media | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Mode | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.01 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.68 | 0.65 |

| Test | Variable (Survey Q) | Variable (Group) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| t-test 1 | Q3—Room impact | Q2—Meditation centre vs. Home | p = 0.99 |

| ANOVA test 1 | Q9—IEQ distraction | Q1—Frequency of meditation | F(4,91) = 2.23, p = 0.072 |

| t-test 2 | Q9—IEQ distraction | Q1—Frequency of meditation | p = 0.008 |

| ANOVA test 2 | Q3—Room impact | Q1—Frequency of meditation | F(4,91) = 2.45, p = 0.052 |

| t-test 3 | Q3—Room impact | Q1—Frequency of meditation | p = 0.841 |

| Design Practice | Strategy | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Site-specific environmental strategies | Contextual adaptation | Tailor design to urban, suburban, or rural settings. Rural sites should exploit open facades, landscape immersion, and passive environmental strategies, such as cross ventilation and shaded courtyards, to connect users with nature and maintain thermal comfort. Urban centres require controlled apertures, landscape buffers, and acoustic treatments to ensure privacy and manage external noise. |

| Environmental zoning | Separate sociable and meditative zones, using strategic placement, material buffers, and transitional spaces to modulate sound and energy. | |

| Journey and Spatial Transitions | Gradual sensory preparation | Model entry sequences on sacred or spiritual journey traditions, using gradual changes in lighting, acoustics, and volumes to prime users’ bodies and minds for meditation. |

| Transitional spaces | Incorporate thresholds, vestibules, or intermediate spaces that help occupants shift from communal to introspective modes. | |

| Public vs. private | Create a journey from public and social spaces to private and meditative spaces. | |

| Flexibility and Movement | Walkways | Accommodate for walking during or between meditation sessions by providing outdoor, contemplative pathways. Facilitate movement breaks to blur boundaries between contemplative and physical activity. |

| Accommodating for movement-based meditation | For those traditions that inherently require physical movement, such as yoga or walking meditation, as a part of the meditation tradition, provide open plan layouts and circulation routes. Space per meditator for such traditions should be generous enough to fit a yoga mat. | |

| Sensory Adaptability | User control | Provide mechanisms for occupants to adjust lighting, noise cancelling, airflow, temperature, and privacy according to their needs and preferences. Adaptability is especially important for beginners, who may be more sensitive to environmental distractions. |

| Managed distractions | Suppress visual and auditory distractions through careful placement of windows, perforated walls, and concealed fixtures. Design flexibility ensures comfort for diverse traditions and individual requirements. | |

| Provision for solitary meditation | Provide spaces for isolated, solitary meditation, such as dedicated cells or adaptable rooms. The emphasis on seclusion is inherent in certain meditation traditions, where isolation is regarded as integral to deepening practice. | |

| Community and Governance | Stakeholder engagement | Involve users, teachers, volunteers, community leaders, and donors early in the design process. The ideal design practice involves a deep understanding of the meditation tradition and its specific requirements. Align spatial solutions with tradition-specific goals, operational resources, and community aspirations. |

| Pragmatism | Recognise that consensus-based and donation-funded centres may require phased construction, flexible material selection, and strategic priorities to ensure completion and adaptability. | |

| Inclusivity and Tradition Alignment | Respond to tradition | Understand and respect the unique requirements of each meditation philosophy practiced in the centre. Adaptive design is critical for sustaining authenticity and supporting evolving needs. |

| Accessible design | Build to, or beyond, local inclusive design standards for a centre that is accessible by individuals of all abilities. | |

| Lighting Environment | Natural light emphasis | Incorporate strategies such as skylights, roof openings, and facades that maximise daylight. Ensure that these openings can be closed according to user preference and to limit solar heat gain when necessary. |

| Filtered and dappled light | Use perforated walls, angled windows, and landscaping to diffuse light, mimicking the biophilic filtration found in trees while minimising distractions. | |

| Artificial lighting | Supplement with dimmable, warm-toned fixtures for evening use. Conceal light sources to reduce glare and refocus attention inward. Adjust lighting to support circadian health and specific requirements. Provide intuitive and sufficient controls for flexibility in lighting scenes. | |

| Indoor Air Quality | Passive ventilation | Prioritise open facades, cross-ventilated plans, and shaded courtyards in suitable, non-polluted climates. |

| Air freshness | Ensure air freshness through filtration or direct connection to outdoor air depending on pollution levels, which is critical to accommodate for the multitude of users sitting in meditation sessions for extended periods of time. | |

| Mechanical systems | Where mechanical ventilation is required, select quiet systems and insulate against unwanted noise. | |

| Thermal Environment | Passive systems | Passive cooling is preferred for its quiet operation and energy efficiency. Passive heating through insulation and thermal mass can reduce energy consumption in the winter. |

| Mechanical systems | Where mechanical heating or cooling is required, select quiet systems and insulate against unwanted noise. | |

| Design at the floor level | Unlike most buildings, users of meditation centres spend a lot of time sitting on the floor. Underfloor heating/cooling systems can provide more direct effects for this purpose. | |

| Constant temperatures | Avoid sudden changes in temperature, which can cause distractions in meditative focus. For centres where sitting meditation takes place, design for thermally comfortable and constant temperatures at the floor level. | |

| Acoustic Environment | Sound management | Foster nature-based quietude in rural settings. In urban sites or large centres, deploy material-based acoustic absorption in walls and ceilings, and landscape buffers to insulate from external disturbances. |

| Sound zoning | Spatially separate communal and meditative spaces and buffer zones to minimise the transmission of noise. | |

| Positive acoustics | Where appropriate, introduce non-intrusive and constant ‘active sounds’, such as water features and white noise, to mask intermittent disturbances, creating a perceived silence. | |

| Materials and Colour | Natural materials | Prioritise locally sourced natural materials, such as timber, stone, bamboo, brick, or context-specific materials, for their biophilic appeal, acoustic properties, thermal performance, and low embodied carbon. This supports both sustainability and cultural resonance. |

| Adaptive reuse | In urban sites, employ durable materials such as concrete for longevity and efficient sound absorption. Layer with tactile surfaces such as wood panels or soft flooring to retain warmth and character. | |

| Impermanence philosophy | Consider the life cycle of the chosen materials. Experiment with materials that weather and evolve, grounding the space in contemplative themes of change and time. | |

| Subtle colour palette | Implement a subtle and calming colour palette for materials and finishes. | |

| Biophilic Elements | Connection to nature | Ensure visual, auditory, or physical connection to planted landscapes, water features, or outdoor courtyards. Use natural materials or anecdotal lighting qualities to reinforce a subtle connection to nature. |

| Indoor planting | Use live plants in transitional spaces or provide visual access to them to soften environments, reduce anxiety, and promote restoration. | |

| Sensory connection to nature | Natural scents and sounds can promote a calm environment and the benefits of biophilia. Olfactory considerations are important for spaces where large groups of people are sitting for long durations. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Doshi, P.; Aletta, F. Developing Design Recommendations for Meditation Centres Through a Mixed-Method Study. Buildings 2025, 15, 4182. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224182

Doshi P, Aletta F. Developing Design Recommendations for Meditation Centres Through a Mixed-Method Study. Buildings. 2025; 15(22):4182. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224182

Chicago/Turabian StyleDoshi, Pearl, and Francesco Aletta. 2025. "Developing Design Recommendations for Meditation Centres Through a Mixed-Method Study" Buildings 15, no. 22: 4182. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224182

APA StyleDoshi, P., & Aletta, F. (2025). Developing Design Recommendations for Meditation Centres Through a Mixed-Method Study. Buildings, 15(22), 4182. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224182