Abstract

The development of sustainable concrete capable of trading off the mechanical performance and cost remains a persistent scientific and engineering challenge. Although previous research has employed multi-objective optimization for binary and ternary cement blends, the simultaneous optimization of quaternary-blended systems, incorporating multiple supplementary cementitious materials, has received little systematic attention. This study addresses this gap by introducing an interpretable artificial intelligence (AI)-driven approach that integrates the Category Boosting (CatBoost) algorithm with the Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) to model and optimize the compressive strength (CS) and total cost of quaternary-blended concretes. A curated database of 810 experimentally documented mixtures was used to train and validate the model. CatBoost achieved superior predictive performance (R2 = 0.987, MAE = 1.574 MPa), while Shapley additive explanations identified curing age, water-to-binder ratio, and Portland cement content as the dominant parameters governing CS. Multi-objective optimization produced Pareto-optimal elite mixtures achieving CS of 51–80 MPa, with a representative 60 MPa mix requiring approximately 62% less cement than conventional designs. The findings establish a scientifically grounded, interpretable methodology for data-driven design of low-carbon, high-performance concretes and demonstrate, for the first time, the viability of AI-assisted multi-criteria optimization for complex quaternary-blended systems. This framework offers both methodological innovation and practical guidance for implementing sustainable construction materials.

1. Introduction

The global shift towards sustainable development has placed the construction sector under significant need for innovative solutions that balance environmental responsibility with industry demands. Concrete is the most extensively utilized construction material worldwide, with annual global cement production reaching approximately 4.10 billion metric tons [1,2,3]. This enormous demand highlights the critical role of cement as the key binding agent in concrete. Cement production alone contributes approximately 8% of global CO2 emissions [4,5], which highlights the urgent need for environmentally friendly alternatives to reduce the sector’s environmental impact. As the foundation of modern infrastructure, concrete’s widespread use highlights the need for sustainable innovations to address the environmental implications of cement manufacturing. One promising approach is using quaternary-blended cement concretes, which incorporate three different supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs, such as fly ash, silica fume, slag, and metakaolin, etc.) in addition to cement. These advanced blends enhance critical mechanical properties, including compressive strength (CS), and improve durability attributes (e.g., resistance to sulfate attack and freeze–thaw cycles) [6]. By reducing clinker content, the SCMs offer a direct and significant reduction in carbon emissions while contributing to developing greener construction practices.

Quaternary-blended cement concretes also demonstrate notable economic advantages, with studies showing potential cost reductions of up to 70% [7,8], alongside improvements in structural performance. Frameworks like the Economic and Ecological Assessment Framework provide valuable tools for evaluating these materials’ economic and environmental benefits, which facilitates their wider adoption. However, their use is not without challenges. The complex interaction of SCMs can lead to negative synergistic issues, and balancing performance metrics often requires trade-offs. For instance, enhanced durability may come at the expense of workability or increased costs. Therefore, achieving optimal material proportions is critical to maximizing benefits. The computational complexity of this task, driven by complicated material interactions, highlights the need for advanced optimization techniques and robust modeling approaches to streamline implementation and further accelerate the shift toward sustainable construction practices [9].

Recent advances in machine learning (ML) have revolutionized the field of concrete mix design by providing powerful tools to predict material properties and streamline the design process with remarkable efficiency. Advanced techniques, such as gradient-boosting ensembles and random forest regression, have demonstrated exceptional accuracy in forecasting key attributes (e.g., CS and durability) in quaternary cement blends [10,11]. These predictive capabilities enable rapid evaluations that promote iterative refinement of mix designs to achieve desired performance outcomes. Furthermore, integrating ML with optimization algorithms has significantly improved the precision and adaptability of concrete material design [4,12]. For instance, reliable ML models (via gradient boosting and support vector regression) have been successfully combined with multi-objective optimization approaches [e.g., Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II)], which offer a robust framework for addressing contradicting objectives (e.g., cost-efficiency, mechanical performance, and environmental sustainability) [6,13]. The strength of NSGA-II is the ability to generate Pareto fronts, which visually represent trade-offs among objectives, thereby empowering informed decision-making for optimal mix proportions. This synergy between predictive modeling and optimization represents a transformative advancement in sustainable concrete engineering.

Recent studies have extensively explored the cost–performance trade-offs in blended cement concretes, utilizing advanced computational approaches and optimization techniques. These works primarily focus on binary and ternary systems, analyzing specific SCMs (e.g., fly ash, slag, and silica fume). ML models, including random forest regression and gradient boosting, have proven effective in predicting mechanical and durability properties [14,15,16]. Similarly, optimization algorithms like NSGA-II have facilitated multi-objective evaluations, which balance economic and performance metrics. A summary of some of these studies is in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of previous literature in multi-objective optimization (MOO) for SCMs.

Existing studies, however, are often constrained by limited datasets and objectives, which leaves quaternary-blended systems underrepresented. Integrating multiple SCMs introduces additional complexities, which require advanced techniques to optimize these mixtures effectively. While prior research provides a foundation, the focus on binary and ternary systems highlights a critical gap in understanding and optimizing quaternary-blended cement concretes. Addressing this problem requires larger datasets and more robust computational frameworks. This study bridges this gap by employing a vigorous dataset of over 800 quaternary-blended cement mixtures, which provide a comprehensive basis for analyzing the intricate interactions among four SCMs. Unlike prior works focusing on binary or ternary blends, this research uniquely applies advanced ML models, including gradient boosting and support vector regression, alongside the NSGA-II to generate detailed Pareto fronts. These techniques achieve the trade-offs between cost efficiency and mechanical performance. By overcoming limitations in prior studies, this work contributes to advancing sustainable construction practices and adopts quaternary-blended cement concretes in diverse structural and environmental applications. The findings of this research are aimed at advancing the development of sustainable and high-performance concretes, which offer scalable solutions for diverse applications (e.g., infrastructure projects, buildings, marine and coastal structures, prefabricated concrete products, etc.).

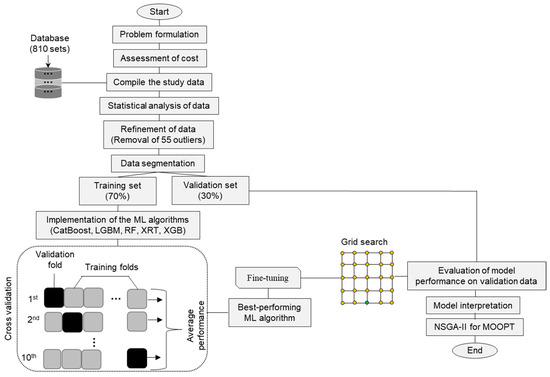

In this research, the decision variables are the components of concrete, which are constrained within realistic bounds derived from experimental data to ensure practical applicability. Through a dual-objective framework, this study aims to simultaneously minimize the total cost and maximize the CS of quaternary-blended cement concretes to translate these competing objectives into practical solutions that balance economic efficiency with mechanical performance. The NSGA-II algorithm effectively generates Pareto-optimal fronts, which offer a detailed understanding of the trade-offs between cost and strength. Figure 1 shows the workflow employed for MOO of concrete formulations used in this research. The research process began with the formulation of the optimization problem and the creation of a comprehensive, high-quality dataset. Rigorous statistical analyses were performed to ensure data integrity, followed by segmentation into training and validation sets to enable robust model development. Multiple ML algorithms were then implemented and evaluated to determine the most suitable model for predictive accuracy and generalization. The selected model underwent systematic hyperparameter optimization through grid search, after which its interpretability and predictive performance were carefully examined.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating the workflow for the ML optimization process.

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Data Acquisition and Processing Methods

2.1.1. Variables of the Model

ML models’ performance fundamentally depends on the quality and diversity of the training data used [23]. In predicting concrete CS, developing an accurate and generalizable model requires a comprehensive dataset. For this study, data on 810 concrete mixtures were systematically compiled from 31 peer-reviewed publications during 2008–2023 [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. These sources were rigorously selected based on their data completeness, consistency, and alignment with the research objectives to ensure the dataset’s robustness and relevance. The collected dataset includes concrete mixes containing key constituents (PC, BF, FA, SF, WA, SP, SA, and CA). The concrete mixes in this study are characterized by their standard curing conditions. The curated database comprises 10 input features and two target labels, CS and TC. A detailed definition of the study’s variables, units, and encoding is presented in Table 2. It is noteworthy that the selection of model input features was guided by both theoretical significance and statistical evaluation. These represent the principal physical and chemical factors controlling hydration, microstructure development, and mechanical performance in quaternary-blended concretes. To ensure their statistical validity, a Pearson correlation analysis was performed to identify potential multicollinearity among predictors, with no features exceeding a correlation threshold of more than 0.85. This confirmed that each variable contributed unique information to the predictive framework. Moreover, preliminary exploratory data analysis (See Section 2.1.2) confirmed consistent variance and distribution across all input variables. After model training, Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) were used to verify the importance ranking and the relative contribution of each feature to the predicted CS.

Table 2.

Characterization and analysis of variables used in this study.

In this study, the TC of each concrete mix proportion was determined using the equation: , where represents the unit price of component , and denotes the corresponding quantity in the mix. Table 3 comprehensively summarizes the average material unit costs () used in the analysis. These cost data were sourced from seven distinct experimental studies [9,55,56,57,58,59], which cover a range of geographic regions to capture market variability effectively. To ensure accuracy and consistency, the mean unit cost for each material was calculated by averaging the reported data from these sources. This methodological rigor supports the study’s goal to provide reliable cost assessments.

Table 3.

Average material costs for constituent components analyzed in this study.

2.1.2. Exploration of Statistical Data

Table 3 provides a detailed statistical analysis of the study dataset. The minimum and maximum values highlight the broad range of data collected, with notable variability in PC (45–650 kg/m3), WA (83.7–234 kg/m3), and CA (306–1328 kg/m3). The mean values reveal the central role of PC (323.5 kg/m3) and WA (169.9 kg/m3) in standard formulations, while the small mean for BF (64.4 kg/m3) and fly ash (FA, 41.4 kg/m3) reflects their selective use in sustainability-driven mixes. Standard deviation values further emphasize variability, particularly for BF (100.8) and CA (170), which show their heterogeneous inclusion across samples. The WB shows a relatively narrow range (0.23–0.70), with a mean of 0.40. CS and TC labels demonstrate significant ranges (CS: 2.01–93.20 MPa; TC: 42.32–141.61 $/m3), highlighting diverse performance and cost outcomes influenced by mix composition.

Table 4 lists the key statistical measures of the study data. Positive skewness in BF (1.47) and FA (1.39) indicates an overrepresentation of lower values, while higher kurtosis for SP (50.41) suggests the presence of outliers. These trends are further supported by quartile values (Q1, Q3), which identify the middle 50% of data points and demonstrate clustering around practical mix proportions for most variables. This analysis underlines the comprehensive nature of the studied quaternary-blended cement formulations.

Table 4.

Summary of descriptive statistical analysis for the study’s data.

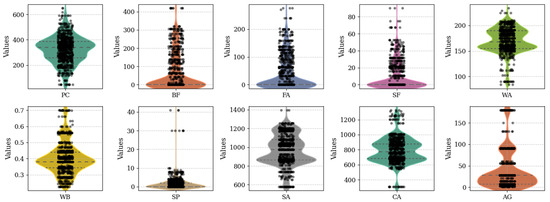

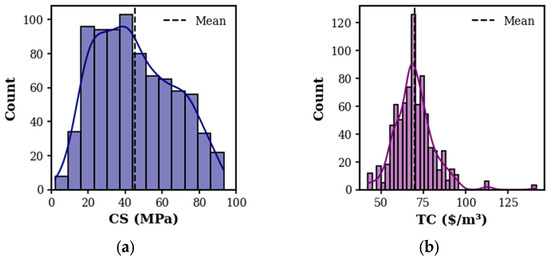

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of key variables influencing the quaternary-blended cement concretes via violin plots illustrating their density and spread. Here, PC demonstrates a symmetric distribution, which indicates its consistent use, while BF and FA show significant variability, which reflects their selective application. Similarly, SF exhibits clustering at lower ranges, which suggests its targeted use for optimizing long-term strength. WA shows a uniform distribution, while WB appears tightly controlled. SP usage peaks at low values, which indicates its selective role in controlling workability without escalating costs. SA and CA display standardized distributions, while AG shows a bimodal pattern corresponding to standard curing periods (e.g., 7, 28, or 90 days). Figure 3 displays the distribution of CS and TC for the investigated concrete mixes. The CS distribution (Figure 3a) exhibits a right-skewed pattern, with most values concentrated between 20 and 60 MPa. Conversely, the TC distribution (Figure 3b) shows a tighter clustering around its mean value (approximately $75/m3) with a sharp peak and narrower spread compared to CS.

Figure 2.

Distributional analysis of key features presented through violin plots.

Figure 3.

Histograms with overlaid kernel density estimates depicting the distribution of: (a) CS and (b) TC.

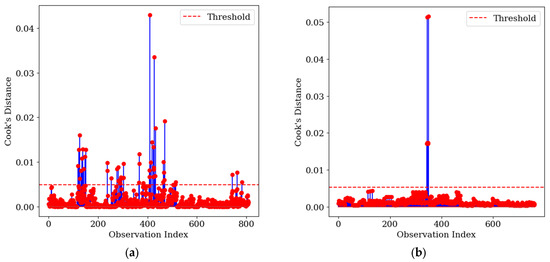

2.1.3. Handling Outliers

Before performing regression analyses, addressing outliers is crucial to minimize their potentially adverse effects on the model’s accuracy and reliability [60]. In this study, a robust statistical approach was employed to identify and manage outliers to accomplish integrity and reasonable distribution of data. For this purpose, a two-stage Cook’s distance (a well-established diagnostic measure) was utilized to pinpoint influential data points that could disproportionately affect regression coefficients. Readers seeking an in-depth understanding of Cook’s distance and its role in outlier detection may refer to [61,62,63]. Here, the first stage pertains to the CS data, while the second involves the TC data. This analysis evaluated the dataset for anomalies, including data entry errors, extreme values, and non-standard distribution patterns such as skewness. The results indicated the presence of several significant outliers. As illustrated in Figure 4a, the initial screening using Cook’s distance identified 49 datasets in the CS data as outliers, which were subsequently removed. The refined dataset, consisting of 761 observations, was retrained to ensure improved model performance. Similarly, Figure 4b demonstrates the detection and exclusion of 6 outlier datasets in the TC variable, leaving a final dataset of 755 observations for analysis. These data refining phases ensured that the regression study data were free from undue influence by anomalous points.

Figure 4.

Stem plots show the applied Cook’s distance methodology to identify outliers in (a) CS and (b) TC datasets.

2.2. Machine Learning Modeling

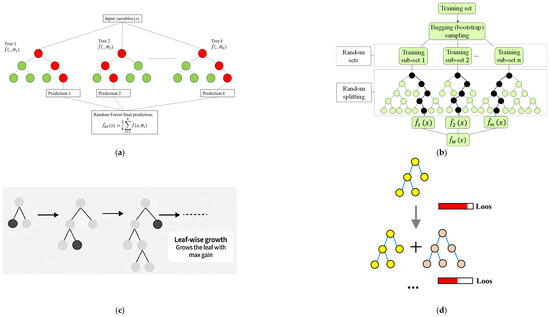

This study employed a rigorous framework to model the CS of the refined study data. Precisely, a diverse set of state-of-the-art ML algorithms (Figure 5) was used, including Random Forest (RF), Extreme Random Forest (XRF), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM), and Categorical Boosting (CatBoost). These algorithms were carefully selected for their demonstrated capacity to handle high-dimensional datasets and capture complex patterns. RF and XRF are ensemble-based techniques known for their robustness and ability to mitigate overfitting [64]; XGBoost and LGBM are gradient-boosting algorithms celebrated for their efficiency and accuracy in predictive modeling [10]; and CatBoost excels in handling categorical variables and minimizing bias [65]. The subsequent subsections provide a concise illustration of the implementation of each ML algorithm. It is noteworthy that the refined dataset (755 records) was randomly partitioned into two subsets: 70% for training, and 30% for testing before training. This stratified random splitting ensured a representative distribution across the entire range of mix compositions and CS values. To further enhance model reliability and reduce bias, 10-fold cross-validation was employed during both training and hyperparameter tuning phases, which allowed each data fold to serve once as a validation subset and ensured comprehensive exposure of the model to all data samples.

2.2.1. Random Forest and Extra Random Forest

The RF algorithm (Figure 5a) generates decision trees using bootstrapped subsets of the dataset. Notably, this approach deliberately excludes the direct inclusion of predictors and outcomes in the primary prediction process, as outlined in [66]. The final model prediction is achieved through an ensemble method that aggregates the outputs of individual trees, effectively minimizing inter-tree correlation and ensuring a comprehensive representation of the data [67]. Building on this foundation, the XRF introduces a novel ML technique designed to enhance predictive accuracy and mitigate the risk of overfitting [32]. In XRF, attribute selection is performed randomly to initiate predictions, which are then iteratively refined by optimizing node splits based on ideal feature values. Unlike RF, which relies on bootstrapped samples for tree construction, XRF utilizes the entire training dataset to build regression trees [68].

2.2.2. Extreme Gradient Boosting

Figure 5b illustrates that the XGB algorithm represents a sophisticated advancement over the traditional RF method, offering superior predictive capabilities through an optimized tree-based framework. Unlike the standard ensemble approach employed by RF, XGB adopts a sequential learning process where each tree is specifically designed to address the errors of its predecessor. This iterative refinement strategy, as described by Natekin et al. [69], enables XGB to systematically enhance its predictive accuracy by minimizing residual errors with each successive iteration.

2.2.3. Light Gradient-Boosting

Figure 5c showcases the performance of LGBM, an advanced ML algorithm renowned for its speed and efficiency in handling large datasets [70]. Built on a gradient-boosting framework, LGBM is designed to optimize both computational performance and memory utilization. Unlike traditional tree-based methods, it employs a leaf-wise growth strategy for constructing decision trees, enhancing predictive accuracy while minimizing computational resource requirements. This innovative approach makes LGBM particularly effective for large-scale, complex datasets.

2.2.4. Category Boosting

CatBoost (Figure 5d) emerges as a highly effective ML algorithm uniquely designed to tackle complex datasets that include diverse data types. Employing an innovative approach to handling categorical features enhances the processing of such variables, thereby achieving remarkable predictive performance in both regression and classification tasks. Its robustness in managing the complexities of real-world data, particularly those involving categorical variables, positions CatBoost as a cutting-edge solution within the ML landscape [71].

2.2.5. Evaluation Metrics and Performance Indicators

After establishing a well-defined model, rigorously evaluating its predictive performance is the next crucial step. This process involves a comprehensive analysis using a set of three statistical metrics [mean absolute error (MAE), root mean squared error (RMSE), and the coefficient of determination ()]. These metrics collectively provide a robust framework for assessing the model’s accuracy and reliability. MAE offers insights into the average magnitude of prediction errors, providing a straightforward interpretation of model precision. RMSE, on the other hand, penalizes larger errors more heavily, making it particularly useful for highlighting significant deviations between predicted and observed values. The coefficient of determination () quantifies the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the model, serving as a key indicator of overall model fit. The mathematical formulations for these metrics are detailed in Equations (1)–(3).

In this context, functions as a representation of the actual values ai denotes the mean of the actual values. In contrast, signifies the predictive value generated by the model, and is the number of observations.

Figure 5.

Structure of (a) RF/XRF [64], (b) XGB [72], (c) LGBM [73], and (d) CatBoost [74] algorithms.

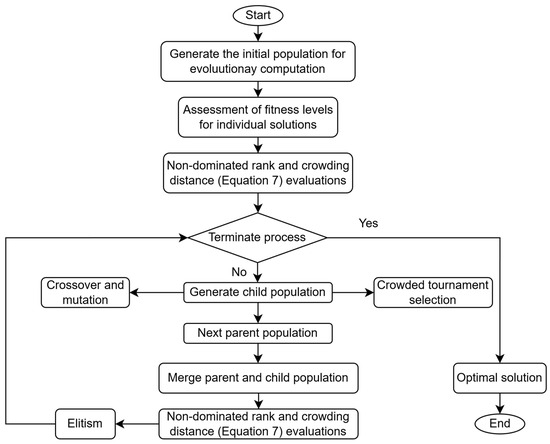

2.3. NSGA-II Optimization Methodology

2.3.1. Background

The NSGA-II is a highly regarded optimization technique originating from Genetic Algorithms (GAs) specifically designed to tackle MOO Problems. Renowned for its ability to balance exploration and exploitation in complex solution spaces, NSGA-II has become a foundational tool for addressing challenging real-world problems across diverse fields such as engineering, operations research, and data-driven decision-making [75]. Since its introduction by Deb et al. [76] in the early 2000s, the algorithm has gained significant recognition, amassing over 52,200 citations on Google Scholar, reflecting its profound influence and widespread use. Over the past two decades, NSGA-II has proven its adaptability in solving MOOPs involving continuous and discrete variables. This algorithm is an improvement over its original NSGA predecessor [76] faced criticism for limitations such as the absence of elitism, dependence on a predefined sharing parameter to maintain solution diversity, and high computational overhead. NSGA-II addresses these issues by integrating elitism, eliminating the need for a sharing parameter, and introducing a crowding distance mechanism to preserve diversity in the population. Furthermore, its enhanced computational efficiency, earning it the title of “Fast Elitist NSGA-II”, makes it a standout choice for MOO. The algorithm’s computational complexity, capped at , where is the number of objectives and is the population size, underscores its practicality for large-scale applications.

A MOOP is characterized by several components: decision variables, objective functions, and a set of constraints, which include inequality constraints and equality constraints. The primary aim of such optimization, whether it involves minimization, maximization, or a combination of both, is mathematically expressed in Equation (4) and is subject to the constraints outlined in Equations (5) and (6). Together, these equations define the complete space of feasible solutions, serving as the foundation for the optimization process.

In this framework, represents the -dimensional decision vector, denoted as (), which belongs to the set , where denotes the space of real-valued vectors of dimension . Similarly, is a -dimensional objective vector residing in . The terms and correspond to the th inequality and the th equality constraints, respectively.

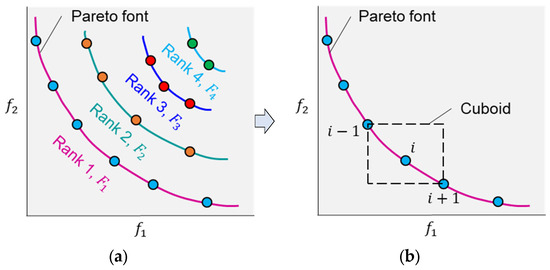

2.3.2. Operational Principles of NSGA-II

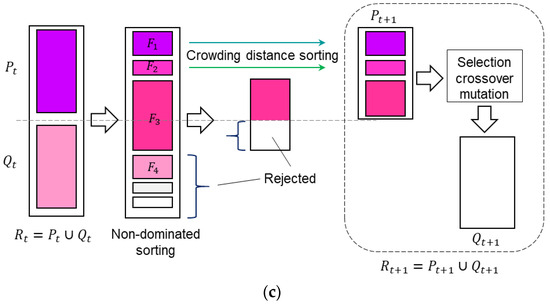

The NSGA-II algorithm operates through four fundamental components: (i) non-dominated sorting, (ii) elitism, (iii) crowding distance, and (iv) a selection strategy. In the sorting stage, individuals are ranked according to Pareto dominance. The non-dominated set, comprising solutions that are not outperformed by any others, is identified first and assigned to the leading front. After removing these individuals, the procedure is repeated to determine subsequent non-dominated groups, which are then allocated to the second, third, and later fronts. This iterative ranking continues until every individual is classified, as depicted in Figure 6a. Elitism serves to retain the highest-quality solutions from one generation to the next, thereby ensuring that superior results are not lost unless improved alternatives emerge. The measure of crowding distance provides an estimate of solution density by calculating the mean separation between neighboring individuals across all objectives. Larger crowding distances indicate sparser regions in the objective space, helping to preserve diversity within the population. Mathematically, for an individual iii with objective value , and where and denote the maximum and minimum values of objective , the crowding distance is expressed as in Equation (7) and can be visualized as the average edge length of the surrounding hyper-cuboid (Figure 6b). Finally, the selection stage employs a crowded tournament method that considers both rank and crowding distance: individuals with superior ranks are prioritized, and in cases of equal rank, those with larger crowding distances are chosen, thereby maintaining both quality and diversity of solutions across generations.

Figure 6.

(a) A depiction of the non-dominated sorting procedure, (b) the crowding distance computation method, and (c) A flowchart outlining the steps of NSGA-II.

2.3.3. Operational Workflow of the NSGA-II Algorithm

In the NSGA-II framework, optimization begins with the construction of an initial population of size . From this set, a new offspring population is generated through the application of crossover and mutation operators. The two populations are subsequently merged to produce , which is subjected to a non-dominated sorting procedure. This classification partitions the individuals of into hierarchical fronts according to their dominance rank. To establish the next generation, , exactly individuals must be chosen from . If the first front contains at least members, the algorithm selects the solutions with the lowest crowding distances within that front. Conversely, when the first front contains fewer than individuals, all of them are carried forward to , and the remaining positions are filled by progressively considering subsequent fronts, again giving preference to individuals with minimal crowding. This procedure ensures that diversity is preserved while maintaining the population size across generations. The procedure is repeated iteratively to create the following generations, such as , , …, etc., continuing until the stopping criterion is met. A visual summary of this process, including the formation and refinement of each generation, is provided in Figure 6c, which highlights how diversity is maintained while driving convergence toward the Pareto-optimal front. For more understanding, Figure 7 presents the conceptual model of the NSGA-II MOO system.

Figure 7.

The NSGA-II methodology flowchart.

2.3.4. Formulation of the Study’s Optimization Problem

This study employed the PyMOO library (version 0.6.1.3) to optimize the mechanical properties of cementitious composites by addressing a mixed-variable, MOOP. The primary goal of the optimization was to simultaneously minimize TC and maximize CS, as specified by the dual-objective formulation [i.e., in Equation (8)]. The decision vector {} consisted of eight variables, each constrained within continuous bounds derived from experimental data, as outlined in Table 2. The optimization problem was formally defined by two objective functions.

- Objective 1:

- Maximize the CS, which was transformed into a minimization task by applying a negative sign, (Min ).

- Objective 2:

- Minimize the predicted TC (Min )

The problem includes 16 inequality constraints, which are designed to ensure that the continuous variables stay within their specified ranges [Equations (9) and (10)]. The cost coefficients employed in Equation (8) were derived from the mean unit prices summarized in Table 3, ensuring consistency between the analytical model and the underlying economic data. Incorporating these verified cost parameters into the total cost (TC) equation enables a realistic estimation of material expenditure for each mix design. This approach not only strengthens the reliability of the economic evaluation but also provides a robust foundation for comparing the cost-effectiveness of different sustainable concrete mixtures under varying material compositions and performance requirements. Additionally, a single equality constraint is applied [Equation (11)] to ensure that the properties are assessed at the same curing age (28 days).

The NSGA-II algorithm was meticulously designed to efficiently navigate the solution space by utilizing a population size of 500 and running for 100 generations. Pre-trained ML models served as predictive tools to estimate CS and total TC, which formed the core metrics for assessing the objectives of each potential solution. These outputs were organized into an objective function matrix, denoted as , enabling systematic evaluation. To maintain feasibility, all relevant constraints were computed and consolidated into a constraint matrix, , ensuring adherence to the problem’s requirements. A key innovation of this implementation was incorporating a robust mechanism to detect and eliminate duplicate formulations, significantly improving both the algorithm’s computational efficiency and the diversity of its solutions.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Performance Evaluation Across Multiple Models

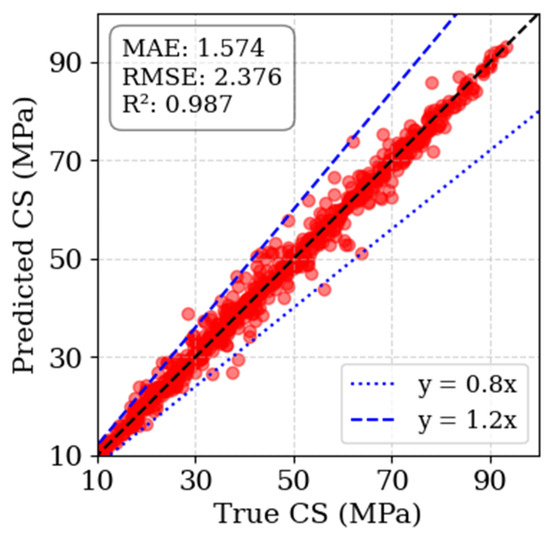

Table 5 compares the selected ML models, evaluated using and the associated standard deviation (StdDev). The initial performance analysis (with the default hyperparameters) revealed that all investigated algorithms exhibited strong predictive capabilities for CS, as indicated by high values and low StdDev. CatBoost emerged as the most effective model, achieving an R2 of 95.6% and a StdDev of 1.5%. The second-best performer (XRT) demonstrated comparable reliability, recording an R2 of 93.9% and a StdDev of 1.8%. CatBoost’s superior performance is attributed to its ordered boosting technique, which reduces prediction bias, and its efficient handling of categorical variables without extensive preprocessing. Moreover, its symmetric tree structure (Figure 5d) ensures stable gradient updates and enhances generalization compared to XGBoost, LightGBM, and RF, which may exhibit higher sensitivity to data imbalance and parameter initialization. To ensure optimal predictive performance, a rigorous hyperparameter tuning process was conducted for the CatBoost model using an extensive grid-search procedure comprising 500 iterations. The optimization simultaneously varied the learning rate, tree depth, and number of estimators to balance model accuracy and computational efficiency. The final configuration (maximum tree depth = 6, learning rate = 0.1, and random seed = 42) yielded the most stable results during cross-validation, minimizing the MAE and maximizing . Owing to its superior accuracy and stability, CatBoost was selected for further optimization through an iterative grid search aimed at hyperparameter tuning. As a result of this rigorous refinement, the optimized CatBoost model achieved a remarkable (98.7%) and MAE (1.574 MPa). Additionally, Figure 8 displays the model’s exceptional accuracy, as the predicted CS consistently falls within ±80% of the target values, with predictive errors rarely exceeding ±20%. This level of precision highlights the robustness of the model in capturing complex data patterns and interactions. Moreover, these findings suggest that the model excels at accurately predicting CS and serves as a valuable analytical tool for explaining the relative importance and interaction of various influencing features. The broader implications of this analysis are further explored in the subsequent section.

Table 5.

Comparative assessment of multiple ML models in predicting the CS.

Figure 8.

Predicted vs. actual values by the optimized CatBoost model.

3.2. Analysis and Interpretation of the Optimized Model

3.2.1. Feature Importance

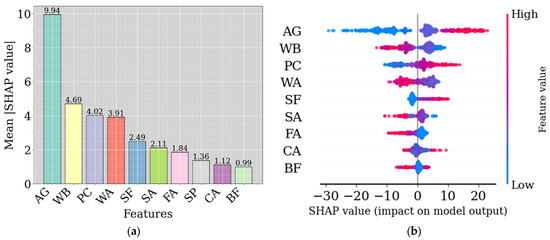

Evaluating the influence of input features is essential for understanding the predictive capacity of models and determining the relative significance of variables in forecasting outcomes [77,78]. Figure 9a provides a comprehensive ranking of input features influencing the prediction of CS based on the mean absolute SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) values derived from the fine-tuned CatBoost model. This analysis suggests that the highest-ranking feature is the AG, which exhibits a mean absolute SHAP value of 9.94. This dominance likely stems from the critical role curing age plays in determining concrete’s mechanical and microstructural properties. Following AG, WB, with a SHAP value of 4.69, emerges as the second most impactful feature. This result aligns with well-documented evidence that the WB ratio strongly governs the hydration process and the resultant pore structure, directly affecting CS. Similarly, PC and WA, with mean SHAP values of 4.02 and 3.91, further support the importance of material proportions in influencing CS. Moderate contributions to CS predictions are observed for SF, SA, and FA, with SHAP values ranging from 2.49 to 1.84. These intermediate contributions suggest that while SCM and fine aggregate proportions influence the composite’s mechanical behavior, their effects are secondary to the primary parameters highlighted earlier. On the other hand, features such as SP, CA, and BF demonstrate minimal influence, with mean SHAP values below 1.5. The negligible effect of these variables indicates that variations in their levels have a comparatively limited impact on CS predictions within the studied dataset, likely because their interactions are less noticeable [9,79]. These findings are consistent with recent studies [56,58,64], which similarly identified aggregate properties and binder proportions as the primary drivers of CS in cementitious systems. The implications of these results are twofold. First, they provide a clear pathway for optimizing the material design of cementitious composites by prioritizing critical features such as AG, WB, and PC. Second, the findings emphasize the importance of data-driven approaches in supplementing traditional material science knowledge, offering a robust framework for understanding feature importance and guiding targeted experimentation. In the broader context, this analysis contributes to the development of more reliable predictive models for CS, with potential applications in mix design optimization and performance-based quality control.

Figure 9.

Ranking of CS influential features (a) mean absolute SHAP, and (b) SHAP values.

The SHAP visualization for CS (Figure 9b) confirms AG as the most impactful variable, followed by WB and PC. The CS of concrete gradually increases over time due to the progressive formation of calcium-silicate-hydrate (C-S-H) gel. This strength typically peaks around 28 days post-casting, influenced by ambient temperature and humidity [80]. Moreover, a lower WB ratio enhances the density and reduces the porosity of the concrete, as excess water, when unreacted, leaves voids that compromise structural integrity. According to Abrams’ law [81,82], for a fixed mix design, the CS of concrete decreases as the water-to-binder ratio increases. Additionally, PC significantly contributes to the early and long-term strength of the concrete, which promotes the formation of a denser, stronger matrix through increased hydration product generation [83,84]. However, excessive PC content must be carefully managed, as it can lead to higher costs, negative environmental impacts, and increased heat of hydration [85,86]. While the WA content contributes to the WB ratio, its absolute value profoundly influences workability and setting time and indirectly affects the density of the hydrated paste [87]. Prior research [88] highlights that SF and FA enhance CS through pozzolanic reactions, which consume lime released during hydration and generate additional C-S-H gel. This process densifies the microstructure, potentially increasing strength over time, with the extent of improvement contingent on factors (e.g., the type and fineness of SCMs), replacement ratios, and curing conditions. Strength gains between 10–30% have been reported for SF and FA compared to conventional concrete [89]. Furthermore, incorporating clean, well-graded sand improves packing density and minimizes voids, indirectly boosting strength, whereas poorly graded or contaminated sand can adversely affect performance [64]. SA, however, is typically considered to contribute minimally to strength, whereas SP enhances workability by lowering the WB ratio, thereby reducing porosity and indirectly increasing strength. SP itself, however, does not directly strengthen the material. Similarly, BF plays a role similar to FA (promotes the pozzolanic reactions), particularly at later stages. BF’s influence on CS varies based on multiple factors, with reported improvements ranging from 5–25% [64].

3.2.2. Sensitivity Analysis

This research conducted an in-depth sensitivity analysis of CS on the most influential features identified through the feature ranking analysis (Section 3.2.1). To achieve this, Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) were employed, a widely recognized tool in ML for interpreting the influence of individual or combined features on model predictions. PDPs provide a model-agnostic framework that offers valuable insights into the average effect of each feature on the predicted outcomes [90]. The analysis particularly emphasized critical factors, including different cementitious materials (PC, BF, FA, and SF), variations in the water-to-binder ratio, and curing age. These variables were systematically examined to assess their contribution to the model’s performance and their implications for optimizing concrete CS. The subsequent section explains the findings of this comprehensive analysis.

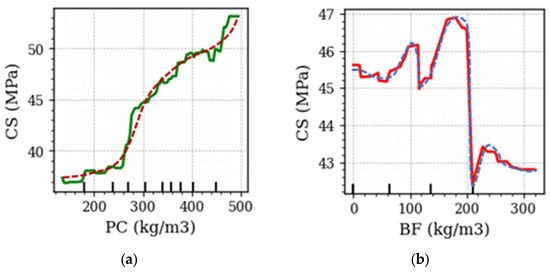

Impact of Various Types of Cement

The PDP presented in Figure 10a illustrates the relationship between PC and compressive CS in a concrete matrix. This figure shows a distinct trend of increasing CS with higher PC values. Statistically, this pattern aligns with prior studies demonstrating that the CS of concrete is positively correlated with PC due to the enhanced formation of hydration products and reduced porosity. For instance, ultra-high content steel fiber reinforced reactive powder concrete (RPC) studies reveal significant strength improvements, up to 355.0 MPa, with optimized cementitious material incorporation [91]. ML models have further underscored the importance of optimizing PC content to achieve target CS while balancing sustainability considerations, as seen in sustainable concrete designs for different curing periods, such as 28 and 90 days [92]. Conversely, findings on recycled powder substitutions for cement demonstrate reduced CS at higher substitution rates, reaffirming the necessity of adequate cement content to maintain mechanical properties [93]. The observed nonlinear yet generally upward trend in the plot reflects these intuitions, which are likely influenced by insignificant returns in CS gains at high cement levels due to saturation effects and possible cracking from autogenous shrinkage.

Figure 10.

Dependence of CS on various types of cement: (a) PC and (b) BF (Note. The solid line represents the predicted values obtained from the developed model, while the dashed line denotes the observed data trend).

Figure 10b shows the influence of BF content on the CS of concrete. The observed pattern indicates an initial increase in CS with increasing BF content, followed by a plateau and a sharp decline beyond approximately 200 kg/m3. Statistically, this trend reflects the nonlinear relationship between BF content and CS, which aligns with previous findings in the literature. Studies highlight that the replacement of PC with BF enhances CS at optimal replacement levels, typically within the range of 30% to 40% of total cementitious material [94,95]. This improvement is attributed to the secondary hydration reactions and the microstructure refinement, which enhances the mechanical properties of concrete. However, the observed decline at higher BF contents is consistent with findings that excessive slag content can increase water demand and reduce the strength due to insufficient hydration of PC and dilution effects [95,96]. The sudden drop in CS beyond the critical BF threshold may also reflect limitations in workability and the mix design’s inability to maintain an optimal particle packing density. Additionally, long-term strength development associated with BF hydration is not captured in the short-term analysis but is known to provide significant strength gains over extended curing periods [97].

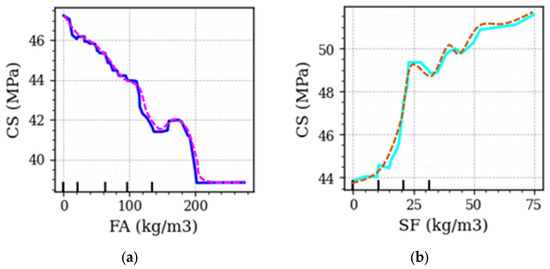

Figure 11a illustrates the PDP relationship between FA and CS of concrete, which reveals a steady decline in CS as FA content increases. This tendency agrees with previous research indicating that low to moderate FA content can improve mechanical properties, while higher FA proportions significantly reduce strength. Research shows that optimal FA levels (typically around 10–15%) enhance CS by facilitating secondary pozzolanic reactions and improving particle packing density [98,99]. For example, a 10% FA addition led to an 11.28% strength increase compared to a control mix without FA [98]. However, beyond this range, excessive FA, such as 50–60%, dilutes the cementitious matrix and reduces hydration activity, causing CS reductions of up to 30.49% in 28 days [100]. This is evident in the plot where higher FA contents (>150 kg/m3) correspond to significant CS reductions. Additionally, consistent findings highlight a trade-off: while increased FA enhances sustainability and reduces permeability, it compromises early strength, as observed in studies with incremental FA replacements of 10–20% [101].

Figure 11.

Dependence of CS on various types of cement: (a) FA and (b) SF (Note. The solid line represents the predicted values obtained from the developed model, while the dashed line denotes the observed data trend).

Moreover, the PDP (Figure 11b) illustrates the relationship between SF content and concrete CS, revealing a consistent increase in the CS with rising SF content up to approximately 60 kg/m3, after which the trend stabilizes. This pattern aligns with the well-established benefits of SF as a cement replacement, which enhances concrete microstructure through pozzolanic activity that forms additional calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H), leading to CS enhancement. Studies confirm that optimal SF concentrations (typically 5–15%) significantly enhance CS, particularly under low water-to-cement ratios, owing to improved particle packing and reduced porosity [102]. Additionally, SF contributes to strength retention at elevated temperatures, where up to 30% replacement proves beneficial due to the formation of thermally stable C-S-H phases [103]. The stabilization observed at higher SF levels may result from diminishing returns in reactivity, potential agglomeration, or workability issues that counteract further CS improvements.

Impact of Water-to-Binder Ratio and Curing Age

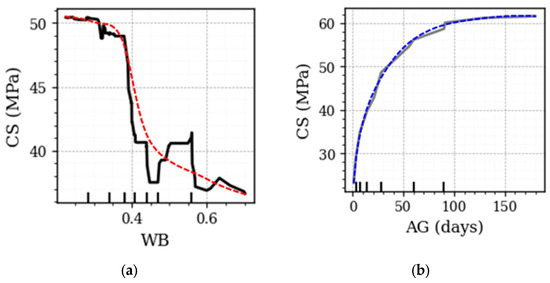

Figure 12a illustrates the impact of WB on the CS of concrete, showing a clear negative correlation as the WB ratio increases. The observed pattern aligns with existing knowledge that a lower WB ratio enhances the mechanical properties of concrete by reducing porosity and improving particle packing, which results in a denser matrix. Studies indicate that WB ratios around 0.18 significantly increase hydration degree, microhardness, and elastic modulus, particularly in the interfacial transition zone [104]. Conversely, as the WB ratio rises beyond 0.4, CS declines due to excess water-generating voids and air bubbles, as demonstrated in roller-compacted concrete and sulfoaluminate cement-based materials [105,106]. These voids compromise the structural integrity, which reduces density and mechanical performance. Moreover, microstructural analysis highlights that higher WB ratios negatively impact porosity, whereas adding FA at lower ratios enhances cementing efficiency, promoting long-term CS development [107].

Figure 12.

Dependence of CS on (a) WB and (b) AG (Note. The solid line represents the predicted values obtained from the developed model, while the dashed line denotes the observed data trend).

Figure 12b illustrates the PDP of the effect of AG on the CS of concrete, which reveals a positive correlation as curing age increases, particularly within the first 28 days. This trend aligns with established findings that prolonged curing enhances hydration processes and densifies concrete microstructure. Early-age curing, particularly under unmanaged or cold conditions, often results in suboptimal strength development due to incomplete hydration, whereas curing periods of 14–28 days under controlled conditions yield more consistent and substantial improvements [108]. Environmental conditions, particularly temperature, play a crucial role, as elevated temperatures accelerate hydration and strength development, while inadequate curing environments can severely hinder long-term performance [109]. Advanced curing methods, such as hydrothermal curing, may enhance early CS but pose risks of thermal damage to long-term properties [110].

3.3. Optimization Outcomes

3.3.1. Pareto Front Characterization

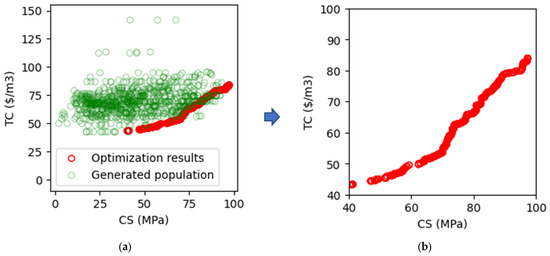

Figure 13 illustrates the optimization workflow for quaternary-blended cement concretes, emphasizing TC and CS trade-offs. The green circles in Figure 13a illustrate the initial population of generated solutions, representing a wide and diverse distribution of potential mixtures. Superimposed on some of these circles are the subset of optimal solutions (red points) identified through the employed MOO approach (NSGA-II) that strategically balance low TC and high CS. Figure 13b consolidates these optimal results, showcasing a distinct trend: as the target CS increases, the corresponding total cost also rises. However, the price is the lowest compared to the generated population, demonstrating an intrinsic trade-off inherent to mixture design. The high TC of high-strength concrete is intuitive because achieving higher CS typically requires using higher quantities of constituent materials. The precise alignment of the optimal points along the Pareto front in Figure 13b highlights the effectiveness of the MOO process in identifying cost-efficient mixtures that meet specified strength requirements. The distribution of data in Figure 13a further reveals that many generated solutions lie above the Pareto front, which indicates inefficiencies in their cost-to-strength ratios. These suboptimal mixtures suffer unnecessary expenses for achieving given strength levels, presenting opportunities for refinement. The optimization model successfully exploits these inefficiencies by focusing on solutions closer to the Pareto front, which minimizes TC without compromising CS.

Figure 13.

Optimization workflow for quaternary-blended cement concretes: (a) population of generated solutions, and (b) optimal solutions.

3.3.2. Optimized Formulations

The optimal mix proportions for 63 quaternary-blended cement concretes, as derived from the combined ML and NSGA-II algorithms, are summarized in Table 6. The results indicate that the TC increases by approximately 39.2% as CS rises from 51.3 MPa (TC = $51.1/m3) to 80.3 MPa. For a target CS of 60 MPa, Cheng et al. [79] proposed an optimal mix design (PC = 332.2, FA = 199.9; BF = 3.1, SF = 0 kg/m3) with an associated cost of about $51.6/m3. In contrast, this study achieved the same strength using significantly reduced PC content (PC = 126.1, FA = 18.4; BF = 10.2, SF = 4.5 kg/m3), while maintaining a comparable cost of $51.67/m3. However, Golafshani and Behood [111] reported an optimal mix for a CS of 50 MPa ± 5% (PC = 334.7, FA = BF = 0, and SF = 0.558 kg/m3), achieving a much lower cost of about $24.5/m3. Yeh [46] demonstrated that achieving a CS of 55 MPa ± 2% required a mix (PC = 331.6, FA = 13.3, BF = 239.8, and SF = 0 kg/m3) for around $57.4/m3. By comparison, the model developed in this study achieved equivalent strength with a mix containing significantly reduced material proportions (PC = 115.5, FA = 24.83, BF = 9.27, and SF = 2.18 kg/m3) at a much lower cost of $51.28/m3. This result highlights the effectiveness of the proposed optimization methodology in delivering cost-efficient solutions. It is noteworthy that Fan et al. [9], using the TOPSIS decision-making method, achieved a CS of 47.4 MPa with a mix (PC = 273.40, FA = 139.8, BF ≈ 0, and SF = 0.01 kg/m3) at a remarkably low cost ($20/m3). While this mix demonstrates the potential for further cost reduction, the optimization approach proposed in this study offers competitive mix designs that balance strength performance and cost-effectiveness more effectively, especially when broader constraints and practical applications are considered.

Table 6.

Optimal formulation for cement concrete with quaternary blends.

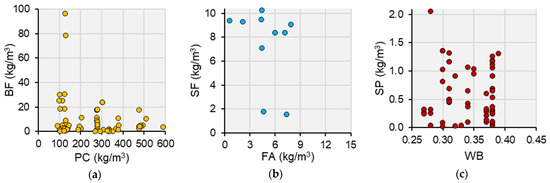

Figure 14 displays the optimized relationships between key mixture components for quaternary-blended cement concretes for PC and BF, FA and SF, and WB and SP. These relationships underscore the diversity of optimized mixtures obtained through the MOO approach. The PC-BF relationship (Figure 14a) indicates that mixtures with higher PC generally require lower BF quantities, which suggests a compensatory role of BF in enhancing mechanical properties when PC content is reduced. This trade-off reflects the model’s capacity to substitute BF for PC to optimize material use without compromising CS. Similarly, the FA-SF relationship (Figure 14b) shows that the inclusion of FA is often paired with higher SF contents that reflect the synergistic effect of these SCMs in enhancing microstructural densification and strength properties. In contrast, the WB-SP relationship (Figure 14c) highlights the role of SP in maintaining workability at varying water-to-binder ratios (WB). The clustering of points at specific WB values suggests that optimized mixes prioritize a balance between reduced water content and the use of SP to achieve desirable flowability without negatively affecting the CS. When compared to the broader population shown in Figure 13a, which encompasses a diverse set of generated solutions, these optimized mixes (Figure 13b) demonstrate clear elitism, aligning closely with the Pareto front. This indicates that the MOO process effectively narrows the solution space to cost-efficient and high-strength formulations.

Figure 14.

Optimized mixture feature relationship: (a) PC-BF, (b) FA-SF, and (c) WB-SP.

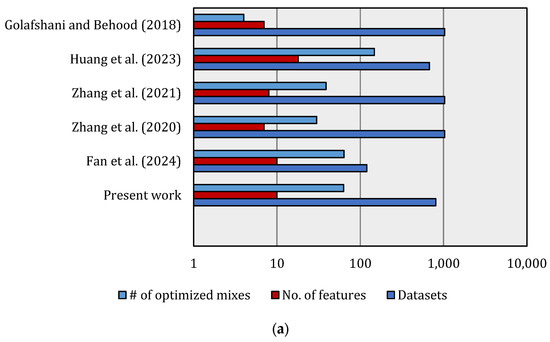

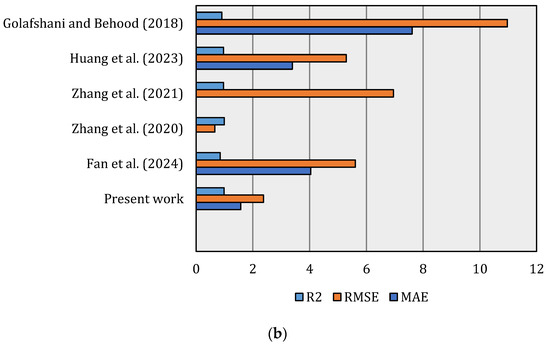

4. Novelty in Comparison with Related Research

This research distinguishes itself by achieving outstanding predictive accuracy for CS, evidenced by an R2 of 0.987, RMSE of 2.376, and MAE of 1.574 while producing 63 optimized concrete mixes. These mixes demonstrate reduced PC usage, enhanced diversity, and superior solution elitism. By utilizing the CatBoost model, this study surpasses the limitations of earlier methods (Table 7 and Figure 15), such as ANN, BPNN, and GB, which showed higher error rates. Focusing on quaternary-blended concretes, it effectively balances CS and TC through NSGA-II. Unlike previous work addressing broader environmental goals or simpler systems, this approach advances material efficiency and sustainable, high-performance concrete design.

Table 7.

Evaluation of the predictive accuracy of the proposed model in relation to previously established frameworks.

Figure 15.

Comparison of performance metrics for the developed and some existing models [9,56,57,58,111]: (a) model characteristics and (b) performance indicators.

Moreover, Figure 15 provides a comparative evaluation between the present study and previously published works in terms of dataset size, number of features, optimized mixes, and model performance metrics (R2, RMSE, and MAE). As shown in Figure 15a, the developed model demonstrates a substantially larger dataset size relative to prior studies, indicating a more comprehensive representation of input–output relationships and a higher statistical reliability. The inclusion of a balanced number of features, while avoiding overparameterization, contributed to enhanced generalizability and computational efficiency. Moreover, the number of optimized concrete mixes achieved in the present work surpasses those reported in earlier studies, underscoring the robustness of the adopted optimization strategy in exploring the design space effectively. In terms of model accuracy (Figure 15b), the proposed framework achieved the highest R2 values alongside notably lower RMSE and MAE values compared to existing models, confirming its superior predictive capability and reduced error margins. This improvement can be attributed to the integration of advanced machine learning methods and the systematic parameter optimization process, which jointly enhanced the model’s capacity to capture nonlinear interactions among mixture components. Furthermore, the improved performance highlights the strength of the dataset curation and preprocessing procedures implemented in this research, which ensured the model’s stability and predictive consistency.

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Implications

This research explores cost–performance optimization in quaternary-blended cement concretes using cutting-edge machine learning and NSGA-II. Analyzing 810 mix designs, it precisely predicts properties and applies multi-objective optimization to balance cost and strength. Constrained by experimental data for practicality, the approach generates Pareto fronts, offering actionable insights. Limitations include reliance on dataset size and scope, warranting broader validation for diverse applications. The results of this research support the following conclusions:

- (1)

- The CatBoost model (R2 of 98.7% and a low MAE of 1.574 MPa) demonstrates exceptional accuracy and stability. Predictive errors were minimal, rarely exceeding ±20%, and the model consistently captured complex patterns with precision.

- (2)

- AG (SHAP value: 9.94) dominates CS predictions, followed by WB (4.69) and PC (4.02), highlighting their critical roles in hydration and structural integrity. Features like SF, SA, and FA (SHAP values: 1.84–2.49) moderately affect CS through pozzolanic reactions and packing density improvements. Variables such as SP, CA, and BF showed limited influence (SHAP < 1.5) on CS predictions.

- (3)

- PC and BF positively impact CS, with optimal BF levels (30–40%) enhancing microstructure and secondary hydration. Excessive cementitious material may cause diminishing returns, reduced workability, and potential structural issues. SF and FA improve CS through pozzolanic reactions, with SF showing optimal benefits at 5–15%. Excess FA (>150 kg/m3) dilutes the cement matrix, significantly reducing strength. A lower WB ratio enhances CS by minimizing porosity and improving matrix density, with optimal performance observed at WB ratios near 0.18. Prolonged curing, particularly within the first 28 days, significantly increases CS by facilitating hydration and microstructural densification, with controlled environmental conditions proving critical.

- (4)

- The Pareto front analysis revealed a clear cost-strength trade-off, with TC increasing by ~39.2% as CS rose from 51.3 MPa to 80.3 MPa. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the MOO approach in balancing economic and mechanical performance. The proposed methodology achieved cost-efficient mix designs, reducing PC usage while maintaining target CS values. For instance, a mix achieving 60 MPa was designed with ~62% lower PC content compared to existing studies, achieving similar costs. Relationships between mix components (e.g., PC-BF, FA-SF) underscore effective substitutions and synergistic effects, optimizing material utilization without compromising strength or workability.

Beyond these conclusions, the present work establishes a scientific foundation for data-driven optimization in sustainable concrete engineering and opens several promising avenues for future development. Future research could explore integrating novel SCMs to further reduce costs and environmental impacts. Expanding datasets to include diverse environmental conditions and material sources would enhance the model’s generalizability. Additionally, subsequent studies will expand the optimization framework to incorporate durability-related metrics (e.g., chloride permeability, carbonation resistance, and freeze–thaw durability) and life-cycle environmental indicators (CO2 footprint and embodied energy). These additions will enable a comprehensive multi-criteria design approach that reflects both mechanical and environmental performance. Moreover, the integration of hybrid metaheuristics (e.g., multi-objective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition and strength Pareto evolutionary algorithm 2) will be explored to benchmark optimization efficiency and convergence performance against NSGA-II. Furthermore, the dataset will be extended to include region-specific materials, particularly locally produced SCMs and aggregates, to enhance generalizability and adapt the model to local construction conditions. In terms of practical implementation, the proposed framework is ready to be deployed in materials and structural laboratories, as well as through collaborative projects with industrial partners in the precast and ready-mix concrete sectors. These partnerships will facilitate pilot-scale validation and calibration of the optimized mix designs under real production environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M.A.; methodology, Y.M.A., A.B. and M.I.K.; software, Y.M.A.; validation, A.B., A.E. and M.I.K.; formal analysis, Y.M.A., A.B. and A.E.; investigation, Y.M.A. and A.B.; data curation, A.B. and A.E.; writing—original draft, Y.M.A. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B., A.E. and M.I.K.; visualization, Y.M.A.; supervision, M.I.K.; project administration, Y.M.A. and M.I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by King Saud University.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to their inclusion in an ongoing collaborative project containing pending intellectual property evaluations that restrict immediate open access.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORFFT-2025-025-5), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Abobakr Elwakeel was employed by the company ALTEN UK. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| ML | Machine Learning | RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| N | Artificial Neural Network | MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| AI | Artificial intelligence | MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| NSGA II | Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II | LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| RF | Random Forest | ICE | Individual Conditional Expectation |

| AdaBoost | Adaptive Boosting | MOWCA | Multi-objective Water Cycle Algorithm |

| GB | Gradient Boosting | CP | Chloride ion permeability |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting | CE | Carbon emissions |

| CatBoost | Categorial Boosting | PC | Portland cement content |

| LGBM | Light Gradient Boosting Machine | SF | Silica fume content |

| XRF | Extreme Random Forest | FA | Fly ash content |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine | BF | Blast Furnace Slag content |

| GA | Genetic algorithm | SP | Superplasticizer dosage |

| GBM | Gradient Boosting Machines | SA | Fine Aggregate content |

| DT | Decision Tree | CA | Coarse Aggregate content |

| DNN | Deep feedforward neural network | AG | Age of testing |

| DBN | Deep belief network | WB | Water-binder ratio |

| GBDT | Gradient Boosting Decision Tree | WA | Water content |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbour | CS | Compressive strength |

| BO | Bayesian optimization | TC | Total cost |

| IGA | Isogeometric analysis | StdDev | standard deviation |

| SCMs | supplementary cementitious materials | SHAP | Shapley Additive exPlanations |

| SMPSO | Speed-constrained multi-objective particle swarm optimization | C-S-H | calcium-silicate-hydrate |

| MOO | Multi-objective optimization | PDPs | Partial Dependence Plots |

References

- Khalil, E.A.; AbouZeid, M.N. Computation of the Environmental Performance of Ready-Mix Concrete for Reducing CO2 Emissions: A Case Study in Egypt. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Wahab, S.A.; Al-Dhamri, H.; Ram, G.; Chatterjee, V.P. An Overview of Alternative Raw Materials Used in Cement and Clinker Manufacturing. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2021, 14, 743–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, G.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; He, Z.; Li, K.; Ning, P.; Wang, X.; Sun, X. Development and Performance Evaluation of Translucent Concrete Incorporating Activated Copper Tailings as Cementitious Material. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; He, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, J. Mixture Optimization of Cementitious Materials Using Machine Learning and Metaheuristic Algorithms: State of the Art and Future Prospects. Materials 2022, 15, 7830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Tang, R.; Li, Q.; Wang, H.; Zou, Y.; Yuan, X. Improved Thermal Performance, Frost Resistance, and Pore Structure of Cement-Based Composites by Binary Modification with MPCMs/Nano–SiO2. Energy 2025, 332, 137166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Deng, T.; Du, T.; Chen, B.; Skibniewski, M.J.; Zhang, L. An RF and LSSVM–NSGA-II Method for the Multi-Objective Optimization of High-Performance Concrete Durability. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 129, 104446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, H.; Teirelbar, A.; Tošić, N.; Ikumi, T.; de la Fuente, A. Data-Driven Optimization Tool for the Functional, Economic, and Environmental Properties of Blended Cement Concrete Using Supplementary Cementitious Materials. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 67, 106022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, K.; Xu, W.; Liu, X.; Ye, J.; Luo, Y. Assessing Carbon Emissions and Reduction Potential in Ecological and Concrete Slope Protection: Case of Huama Lake Project. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Li, Y.; Shen, J.; Jin, K.; Shi, J. Multi-Objective Optimization Design of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Mixture Proportions Based on Machine Learning and NSGA-II Algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2024, 192, 103631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, I.B.; Abdulkareem, M.; Jassam, T.M.; AlAteah, A.H.; Al-Sodani, K.A.A.; Al-Tholaia, M.M.H.; Nabus, H.; Alih, S.C.; Abdulkareem, Z.; Ganiyu, A. Comparative Analysis of Gradient-Boosting Ensembles for Estimation of Compressive Strength of Quaternary Blend Concrete. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2024, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsdyke, J.C.; Zviazhynski, B.; Lees, J.M.; Conduit, G.J. Probabilistic Selection and Design of Concrete Using Machine Learning. Data-Centric Eng. 2023, 4, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Shiuly, A.; Sau, D.; Mondal, A.K.; Sarkar, K. Study on the Use of Different Machine Learning Techniques for Prediction of Concrete Properties from Their Mixture Proportions with Their Deterministic and Robust Optimisation. AI Civ. Eng. 2024, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wang, K.; Liu, Q.; Wang, P.; Pan, F. Machine-Learning-Based Comprehensive Properties Prediction and Mixture Design Optimization of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi Golafshani, E.; Kim, T.; Behnood, A.; Ngo, T.; Kashani, A. Sustainable Mix Design of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Using Artificial Intelligence. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442, 140994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandifaez, P.; Asadi Shamsabadi, E.; Akbar Nezhad, A.; Zhou, H.; Dias-da-Costa, D. AI-Assisted Optimisation of Green Concrete Mixes Incorporating Recycled Concrete Aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 391, 131851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungle, N.P.; Mate, D.M.; Mankar, S.H.; Tale, V.T.; Vairagade, V.S.; Shelare, S.D. Applications of Computational Intelligence for Predictive Modeling of Properties of Blended Cement Sustainable Concrete Incorporating Various Industrial Byproducts towards Sustainable Construction. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 25, 5939–5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkata Rao, R.; Taler, J. (Eds.) Advanced Engineering Optimization Through Intelligent Techniques; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; ISBN 978-981-19-9284-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tipu, R.K.; Panchal, V.R.; Pandya, K.S. Multi-Objective Optimized High-Strength Concrete Mix Design Using a Hybrid Machine Learning and Metaheuristic Algorithm. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 24, 849–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, A.I.; Londoño, J.M.; Vargas, J.F.; Zuluaga, C.; Gómez, A. Modeling and Optimization of Concrete Mixtures Using Machine Learning Estimators and Genetic Algorithms. Modelling 2024, 5, 642–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbaghi, F.; Tanhadoust, A.; Nehdi, M.L.; Nasrollahpour, S.; Dehestani, M.; Yousefpour, H. Life Cycle Assessment Multi-Objective Optimization and Deep Belief Network Model for Sustainable Lightweight Aggregate Concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 318, 128554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Su, F.; Antwi-Afari, M.F.; Lei, J.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y. Enhancing Mix Proportion Design of Low Carbon Concrete for Shield Segment Using a Combination of Bayesian Optimization-NGBoost and NSGA-III Algorithm. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 465, 142746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.T.; Lee, J.; Nguyen-Thoi, T. Multi-Objective Optimization of Multi-Directional Functionally Graded Beams Using an Effective Deep Feedforward Neural Network-SMPSO Algorithm. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2021, 63, 2889–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, R.; Aggarwal, P.; Aggarwal, Y. Prediction of Compressive Strength of Self-Compacting Concrete Containing Bottom Ash Using Artificial Neural Networks. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2011, 42, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F.U.A.; Supit, S.W.M.; Sarker, P.K. A Study on the Effect of Nano Silica on Compressive Strength of High Volume Fly Ash Mortars and Concretes. Mater. Des. 2014, 60, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.H.; Islam, J. Use of Nano-Silica to Reduce Setting Time and Increase Early Strength of Concretes with High Volumes of Fly Ash or Slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 29, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, M.; Mansouri, E.; Sharifipour, M.; Pouladkhan, A.R. Mechanical, rheological, durability and microstructural properties of high performance self-compacting concrete containing SiO2 micro and nanoparticles. Mater. Des. 2012, 34, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.Z.; Zhao, R.; Sadozai, S.; Zhu, F.; Ji, N.; Xu, L. Research on the Influence of Curing Strategies on the Compressive Strength and Hardening Behaviour of Concrete Prepared with Ordinary Portland Cement. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer Hussain, S.; Gopala Krishna Sastry, K.V.S. Study of Strength Properties of Concrete by Using Micro Silica and Nano Silica. Int. J. Res. Eng. Technol. 2014, 3, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Yan, J.B. Experimental Studies and Analysis on Compressive Strength of Normal-Weight Concrete at Low Temperatures. Struct. Concr. 2018, 19, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badarloo, B.; Kari, A.; Jafari, F. Experimental and Numerical Study to Determine the Relationship between Tensile Strength and Compressive Strength of Concrete. Civ. Eng. J. 2018, 4, 2787–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangestuti, E.; Pangestuti, E.K.; Handayani, S.; Purnomo, M.; Silitonga, D.C.; Fathoni, M.H. The Use of Fly Ash as Additive Material to High Strength Concrete. J. Tek. Sipil Perenc. 2018, 20, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipta, O.B.; Sobhan, S.K.F.; Shuvo, A.K. Assessment of the Combined Effect of Silica Fume, Fly Ash, and Steel Slag on the Mechanical Behavior of Concrete. J. Civ. Eng. Constr. 2023, 12, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.L.; Liu, X.Y.; Hu, Y.P. Study on the Influence of Fly Ash and Silica Fume with Different Dosage on Concrete Strength. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 237, 03038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalak, T.; Szypura, P.; Cierpiszewski, R.; Ulewicz, M. Modification of Concrete Composition Doped by Sewage Sludge Fly Ash and Its Effect on Compressive Strength. Materials 2023, 16, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, M.; Alsadey, S.; Johari, M. Effect of Superplasticizer Dosage on Workability and Strength Characteristics of Concrete. IOSR J. Mech. Civ. Eng. 2016, 13, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosan, A.; Shaikh, F.U.A. Influence of Nano Silica on Compressive Strength, Durability, and Microstructure of High-Volume Slag and High-Volume Slag–Fly Ash Blended Concretes. Struct. Concr. 2021, 22, E474–E487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadey, S.; Omran, A. Effect of Superplasticizers to Enhance the Properties of Concrete. Des. Constr. Maint. 2022, 2, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahani, A.K.; Samanta Amiya, K.; Singhroy, D.K. An Experimental Study on Strength Development of Concrete with Optimum Blending of Flyash and Granulated Blast Furnace Slag. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2018, 13, 5700–5710. [Google Scholar]

- Wahab, A.; Dean Kumar, B.; Bhaskar, M.; Kumar, S.V.; Swami, B.L.P. Concrete Composites with Nano Silica, Condensed Silica Fume and Fly Ash-Study of Strength Properties. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2013, 4, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Karaşin, A.; Doğruyol, M. An Experimental Study on Strength and Durability for Utilization of Fly Ash in Concrete Mix. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 2014, 417514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.S.; Yen, T.; Liu, Y.W.; Sheen, Y.N. Relation between Porosity and Compressive Strength of Slag Concrete. In Proceedings of the 2008 Structures Congress—Structures Congress 2008: Crossing the Borders, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–26 April 2008; Volume 314, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Park, W.S.; Cho, S.H.; Kim, D.G.; Noh, J.M. An Experimental Study on Mechanical Properties for Ternary High Performance Concrete with Fly-Ash, Blast Furnace Slag, Silica Fume. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 204–208, 3699–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesoǧlu, M.; Güneyisi, E.; Özbay, E. Properties of Self-Compacting Concretes Made with Binary, Ternary, and Quaternary Cementitious Blends of Fly Ash, Blast Furnace Slag, and Silica Fume. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nochaiya, T.; Wongkeo, W.; Chaipanich, A. Utilization of Fly Ash with Silica Fume and Properties of Portland Cement–Fly Ash–Silica Fume Concrete. Fuel 2010, 89, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, K.; Turgut, P.; Karatas, M.; Benli, A. Mechanical Properties of Self-Compacting Concrete with Silica Fume/Fly Ash. In Proceedings of the 9th International Congress on Advances in Civil Engineering, Trabzon, Turkey, 27–30 September 2010; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Chidiac, S.E.; Panesar, D.K. Evolution of Mechanical Properties of Concrete Containing Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag and Effects on the Scaling Resistance Test at 28 Days. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2008, 30, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, P.J.; Rey, N. The Influence of Ground Granulated Blastfurnace Slag (GGBS) Additions and Time Delay on the Bleeding of Concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2000, 22, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingöl, A.F.; Tohumcu, I. Effects of Different Curing Regimes on the Compressive Strength Properties of Self Compacting Concrete Incorporating Fly Ash and Silica Fume. Mater. Des. 2013, 51, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, A.R.; Zanganeh, H.; Moalemi, M.M. Mechanical and Durability Properties of Ternary Concretes Containing Silica Fume and Low Reactivity Blast Furnace Slag. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, A.; Zanganeh, H.; Alizadeh, H.; Shakerinia, M.; Marian, M.A.S. Comparing the Performance of Fine Fly Ash and Silica Fume in Enhancing the Properties of Concretes Containing Fly Ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 1402–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phul, A.A.; Memon, M.J.; Shah, S.N.R.; Sandhu, A.R. GGBS And Fly Ash Effects on Compressive Strength by Partial Replacement of Cement Concrete. Civ. Eng. J. 2019, 5, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, D.M.; Golewski, G.L. Potential of Siliceous Fly Ash and Silica Fume as a Substitute for Binder in Cementitious Concretes. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 49, 00030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Park, W.S.; Jang, Y., II; Kim, S.W.; Kim, S.W.; Nam, Y.H.; Kim, D.G.; Rokugo, K. Mechanical Properties of Energy Efficient Concretes Made with Binary, Ternary, and Quaternary Cementitious Blends of Fly Ash, Blast Furnace Slag, and Silica Fume. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2016, 10, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadrmomtazi, A.; Tahmouresi, B.; Khoshkbijari, R.K. Effect of Fly Ash and Silica Fume on Transition Zone, Pore Structure and Permeability of Concrete. Mag. Concr. Res. 2018, 70, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xia, P.; Gong, F.; Zeng, Q.; Chen, K.; Zhao, Y. Multi Objective Optimization of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Based on Explainable Machine Learning. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 445, 141045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Ma, G.; Nener, B. Mixture Optimization for Environmental, Economical and Mechanical Objectives in Silica Fume Concrete: A Novel Frame-Work Based on Machine Learning and a New Meta-Heuristic Algorithm. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 167, 105395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, G. Multi-Objective Optimization of Concrete Mixture Proportions Using Machine Learning and Metaheuristic Algorithms. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 253, 119208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Huo, Z.; Ma, G.; Zhang, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, J. Multi-Objective Optimization of Fly Ash-Slag Based Geopolymer Considering Strength, Cost and CO2 Emission: A New Framework Based on Tree-Based Ensemble Models and NSGA-II. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 68, 106070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, I.C. Computer-Aided Design for Optimum Concrete Mixtures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2007, 29, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riani, M.; Atkinson, A.C. Robust Diagnostic Data Analysis: Transformations in Regression. Technometrics 2000, 42, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Tsai, C.L. Outlier Detection. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2011, 1, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, D. Detecting Outliers and Influential and Sensitive Observations in Linear Regression. In Springer Handbook of Engineering Statistics; Springer: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Emenike, I.C. Outlier Detection in a Repeated Measure Design. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2023, 39, 2582–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiker, A.; Abbas, Y.M.; Khan, M.I.; Abdel-Magid, T. Optimizing Compressive Strength of Quaternary-Blended Cement Concrete through Ensemble-Instance-Based Machine Learning. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 109150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jánošík, D. Enhanced Short-Term Load Forecasting with Hybrid Machine Learning Models: CatBoost and XGBoost Approaches. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 241, 122686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. New Machine Learning Algorithm: Random Forest. In Information Computing and Applications; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7473, pp. 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C.; Gnasso, A. A Comparison among Interpretative Proposals for Random Forests. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2021, 6, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.W.; Reynolds, J.; Rezgui, Y. Predictive Modelling for Solar Thermal Energy Systems: A Comparison of Support Vector Regression, Random Forest, Extra Trees and Regression Trees. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natekin, A.; Knoll, A. Gradient Boosting Machines, a Tutorial. Front. Neurorobotics 2013, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Sandhu, J.K.; Kumar, Y. An Analysis of Detection and Diagnosis of Different Classes of Skin Diseases Using Artificial Intelligence-Based Learning Approaches with Hyper Parameters. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2023, 31, 1051–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. CatBoost for Big Data: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuken, A.; Abbas, Y.M.; Siddiqui, N.A. Efficient Prediction of the Load-Carrying Capacity of ECC-Strengthened RC Beams—An Extra-Gradient Boosting Machine Learning Method. Structures 2023, 56, 105053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]