Abstract

Expanded polystyrene (EPS) concrete has broad application potential in energy-efficient buildings due to its low density and excellent thermal insulation performance. However, a significant nonlinear trade-off exists between its compressive strength and thermal conductivity. Existing studies are mainly based on empirical mix design or single-objective optimization, and the employed modeling methods generally lack interpretability. To address this challenge, this study proposes a multi-objective optimization model (MOPIA-RA) based on physics-informed constraints and an intelligent evolutionary algorithm, aiming to solve the nonlinear contradiction among compressive strength, thermal conductivity, and production cost encountered in practical engineering. A comprehensive dataset covering different cementitious materials, EPS contents, and particle sizes was established based on experimental data, and a surrogate model (PIA-RA) was developed using this dataset. Finally, the Shapley additive explanation (SHAP) method was used to quantitatively evaluate the effects of key materials on compressive strength and thermal conductivity. The results show that the proposed PIA-RA model achieved coefficients of determination (R2) of 0.95 and 0.98 for predicting compressive strength and thermal conductivity, respectively; EPS particle size was the main factor affecting performance, with a contribution rate of 69%, while EPS content also played an important regulatory role, with a contribution rate of 29%. Based on the constructed MOPIA-RA model, it is possible to effectively resolve the multi-objective trade-offs among strength, thermal performance, and cost in EPS concrete and achieve precise mix design. The proposed MOPIA-RA model not only realizes multi-objective optimization among compressive strength, thermal performance, and cost, but also establishes a physics-informed and interpretable methodology for concrete material design. This model provides a scientific basis for the mix-design optimization of EPS concrete.

1. Introduction

Driven by the pursuit of green building and sustainable development, lightweight concrete has attracted widespread attention in the field of building energy conservation, because it can reduce the self-weight of structures and improve the thermal insulation performance of building structures. Among the various lightweight concretes, expanded polystyrene (EPS) concrete has broad application prospects due to its low density and excellent thermal insulation properties [1,2,3,4]. However, the large number of closed pores and interfacial defects inside EPS concrete significantly weaken the load-bearing capacity of the matrix, leading to a reduction in compressive strength, and create a difficult-to-coordinate trade-off among strength, thermal insulation, and cost, thus restricting its promotion and application in engineering practice [5,6,7]. How to maintain excellent thermal insulation performance while taking mechanical properties and economic feasibility into account has become a key issue that urgently needs to be addressed.

For multi-objective trade-offs in mix proportioning, traditional studies mainly adopt experimental design and statistical modeling methods. Li et al. [8] optimized the mix proportion of high-performance concrete by establishing regression models among the water-to-binder ratio, sand ratio, and fly ash content using the response surface methodology (RSM) and validated the models through analysis of variance and experimental verification, demonstrating the effectiveness of RSM in multi-parameter proportioning design. Feng et al. [9] applied an orthogonal experimental design to optimize multiple performance indices of hybrid fiber-reinforced recycled coarse aggregate concrete, and constructed regression models linking fiber dosages, recycled aggregate content, etc., to strength and durability indicators, thereby validating the utility of statistical regression techniques in multi-factor mix proportioning. Kadam et al. [10] predicted the mechanical performance of high-strength steel fiber-reinforced concrete using multiple regression techniques, relating steel fiber content and the water–cement ratio to compressive strength, split tensile strength, flexural strength, and modulus of elasticity, and verified that the regression models closely matched test results, illustrating the applicability of statistical regression in performance prediction. Liu et al. [11] used an orthogonal experimental design to study machine-made tuff sand concrete and identified key mix parameters affecting workability and strength, confirming the method’s effectiveness for mix optimization. Although these studies have provided preliminary methods for mix proportion optimization, they generally rely on low-order polynomial fitting and linear assumptions, making it difficult to fully characterize the complex interaction effects and nonlinear patterns among variables.

Traditional statistical methods are limited when handling high-dimensional nonlinear coupling relationships, which has prompted researchers to introduce more complex statistical optimization strategies to improve the predictive accuracy and applicability of their models. Lam et al. [12] investigated the reuse of clay brick and ceramic waste as aggregates in concrete and employed Taguchi and Box–Behnken design methods to model and optimize compressive strength and durability, demonstrating the feasibility of multi-factor statistical optimization for sustainable mix design. George et al. [13] assessed the performance of blended self-compacting concrete incorporating ferrochrome slag as fine aggregate and applied functional ANOVA to quantify the influence of mix parameters on its fresh and hardened properties, confirming the method’s effectiveness for multi-factor analysis. Pan et al. [14] developed optimized strength prediction models for foamed concrete by applying principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce input dimensionality and feeding the extracted features into regression models, improving predictive accuracy and interpretability. However, the core of these methods still remains within the traditional linear statistical framework, making it difficult to effectively address the highly nonlinear coupling among strength, thermal conductivity, and cost in EPS concrete, thus showing obvious limitations in engineering applications.

With the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies [15,16,17,18], researchers have gradually shifted from traditional statistical models to approaches that combine data-driven high-precision prediction with intelligent optimization. Models such as Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), due to their excellent nonlinear fitting capabilities, have been widely applied to predict concrete properties such as compressive strength, durability, and shrinkage [19,20,21,22,23,24]. Meanwhile, evolutionary algorithms such as the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II), Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization (MOPSO), and Simulated Annealing (SA) have been introduced to achieve multi-objective optimization among various performance indicators [25,26,27,28,29]. The combination of surrogate modeling and intelligent optimization has been validated across different concrete systems: Fan et al. [30] integrated a machine learning predictor with NSGA-II to obtain Pareto-optimal mix designs for recycled aggregate concrete that balance compressive strength, cost, and carbon emissions; Da Silva et al. [31] applied MOPSO to optimize steel–concrete composite slab design, achieving trade-offs among load-bearing capacity, economy, and carbon emissions; Tian et al. [32] employed particle swarm optimization for the multi-objective design of UHPC, considering both strength and workability; and Dai et al. [33] developed a machine learning framework to predict and optimize the frost resistance of low-carbon concrete. As intelligent optimization and machine learning have achieved remarkable progress in various concrete systems, several researchers have also attempted to apply data-driven and optimization approaches to EPS lightweight concrete. Zhang et al. [34] established an XGBoost-based prediction and optimization framework for EPS lightweight concrete through orthogonal experiments, enabling simultaneous prediction of its mechanical and thermal properties. Dabi et al. [35] adopted stochastic machine learning models to optimize the particle size and dosage of EPS, effectively capturing the nonlinear relationships between mix design parameters and performance indicators. Although research on the prediction and optimization of EPS concrete has advanced in recent years, limitations remain in terms of model interpretability and multi-objective optimization capability. Existing models, while capable of achieving high fitting accuracy, often rely on empirical fitting, lack physical consistency and interpretability, and are unable to simultaneously balance compressive strength, thermal conductivity, and material cost.

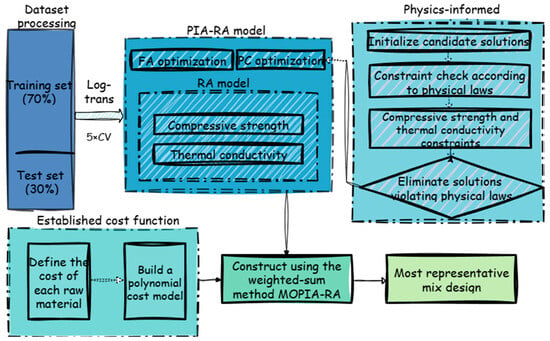

To address these challenges, this study develops a multi-objective design model (MOPIA-RA) that integrates physical constraints with intelligent optimization. First, a systematic performance database of EPS concrete was established to alleviate the problem of limited experimental data. Then, by introducing a physically guided directional derivative constraint into the Random Forest surrogate model, a physics-informed PIA-RA model was constructed, enhancing prediction accuracy, robustness, and generalization while maintaining consistency with material physical laws. To improve interpretability, the Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) method was employed to quantify the effects of key variables such as EPS content and particle size on compressive strength and thermal conductivity. Furthermore, the Pareto front was used to describe the trade-offs among compressive strength, thermal conductivity, and material cost, and the TOPSIS method was applied to identify representative mix designs with practical engineering feasibility. This model provides actionable decision support for engineering design and application.

2. Data Basis and Characterization Analysis for Model Establishment

2.1. Preparation of Specimens

This study focused on the balanced optimization of compressive strength and thermal performance in EPS lightweight concrete, systematically carrying out mix proportion design and experimental verification, and a total of 128 groups of concrete specimens were prepared. Each mix proportion used ordinary Portland cement (P.O 42.5 Tianshan Cement Co., Ltd., Urumqi, China) as the main cementitious material, and its performance indicators are shown in Table 1. The design ranges of the variables referred to the Technical Specification for Application of Foamed Concrete (JG/T 266-2011) [36] and were determined in combination with preliminary experimental results: the design lower limit of compressive strength was set to 3 MPa, and the upper limit of thermal conductivity was controlled at 0.30 W·m−1·K−1. The compressive strength test was conducted in accordance with the Standard for Test Methods of Physical and Mechanical Properties of Concrete (GB/T 50081-2019) [37], using 150 mm cubic specimens tested after 28 days of curing. The thermal conductivity test was performed using the steady-state heat flow meter method, following the Test Method for Steady-State Thermal Resistance and Related Properties of Thermal Insulation Materials (GB/T 10294-2008) [38].

Table 1.

Physical properties of p.o 42.5 cement.

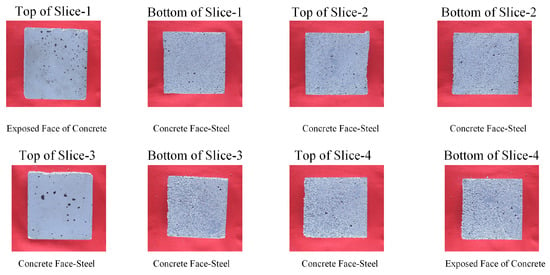

The lightweight aggregate adopted EPS particles, with a designed volume fraction range of 70–85% and stepwise adjustment in 5% gradients; the EPS particle size was divided into two categories, large particle size (6.3–4.75 mm) and small particle size (2.36–1.18 mm), to investigate interfacial bonding characteristics and changes in pore structure. Mineral admixtures selected included fly ash (Tianshan Cement Co., Ltd., Urumqi, China), silica fume (Tianshan Cement Co., Ltd., Urumqi, China), and slag powder (Tianshan Cement Co., Ltd., Urumqi, China), which partially replaced cement at mass substitution rates of 0–25%; the chemical composition and characteristic parameters of the selected different cementitious materials are shown in Table 2, and the detailed mix proportions are shown in Table 3. Compressive strength was tested on 150 mm cubes after 28 days, and thermal conductivity was measured using the steady-state heat flow meter method. Finally, systematic and complete compressive strength and thermal conductivity data were obtained, and a comprehensive experimental database covering key mix proportion parameters was constructed to provide the data foundation for subsequent PIA-RA performance prediction and multi-objective optimization. Representative photographs of the prepared EPS concrete slices are shown in Figure 1 to visually illustrate their typical surface morphology.

Table 2.

Major chemical components and characteristic parameters of various cementitious materials.

Table 3.

Mix proportion design for EPS concrete.

Figure 1.

Top and bottom surfaces of EPS concrete slices used in the experiments.

2.2. Distribution Characteristics and Preprocessing of EPS Concrete Experimental Data

Based on the mix proportions and experimental test results, this study constructed an experimental database of the compressive strength and thermal conductivity of EPS concrete. The input variables included the mass replacement rates of fly ash, slag powder, and silica fume, the EPS volume fraction, and the particle size; the output variables were compressive strength and thermal conductivity . This database can not only be used to reveal the effect patterns of single factors on material properties but also to analyze the combined effects of multiple factors on the performance of EPS concrete.

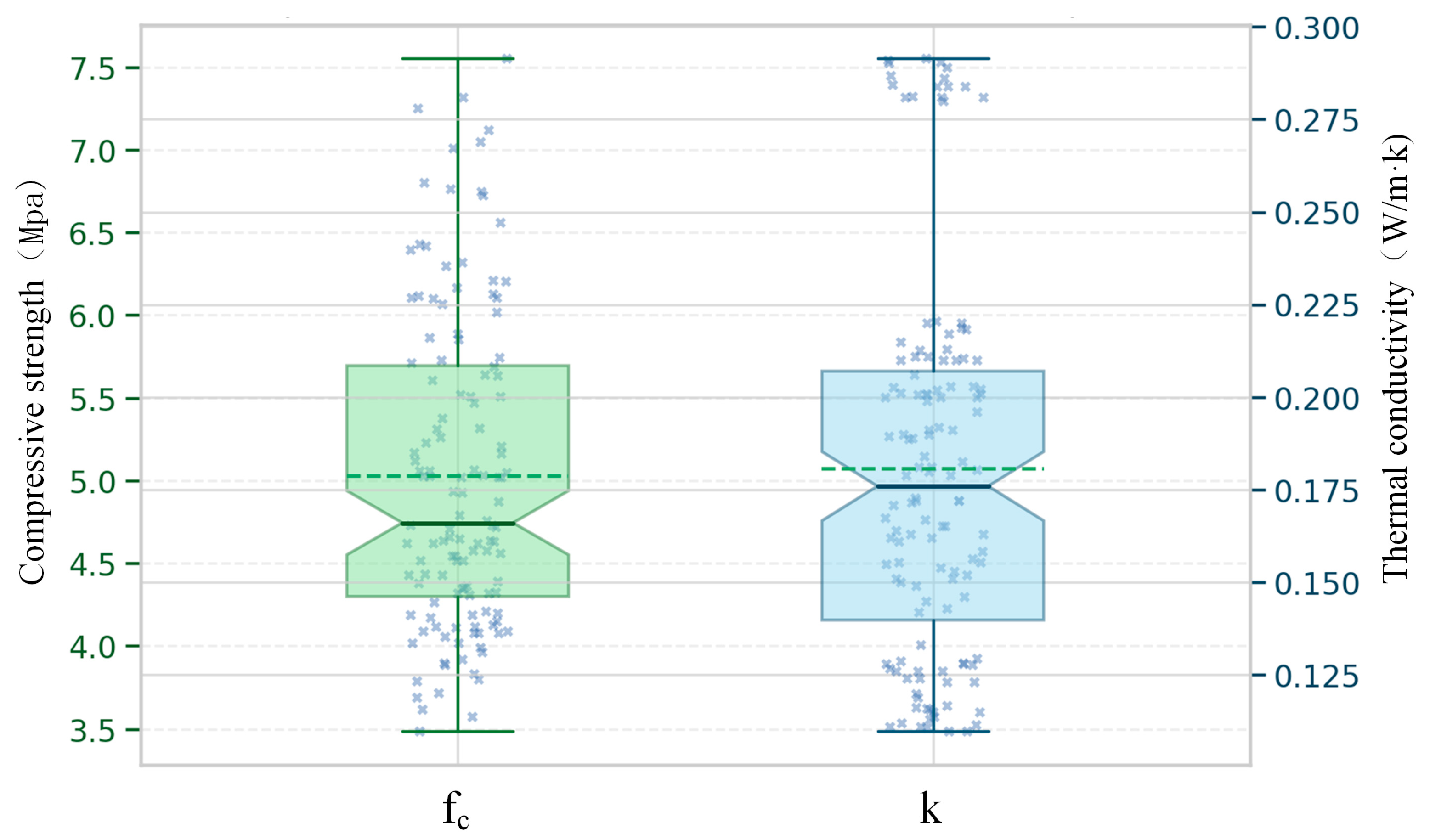

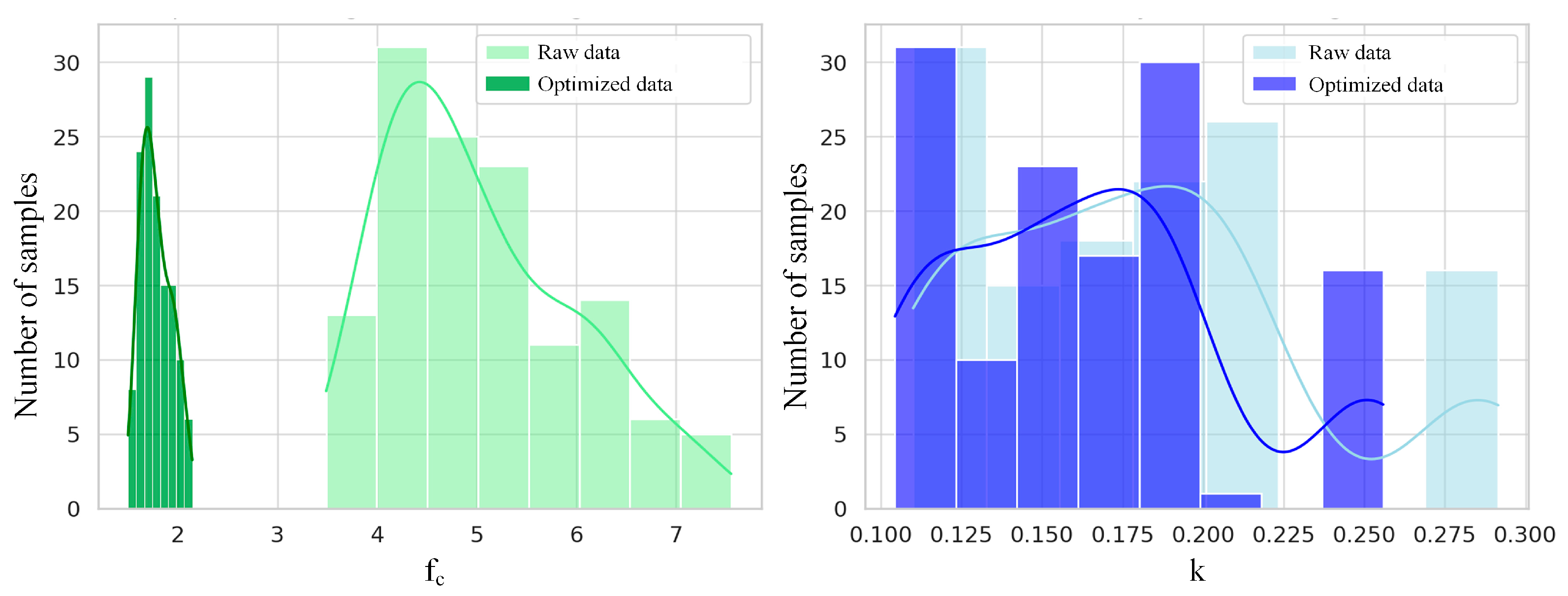

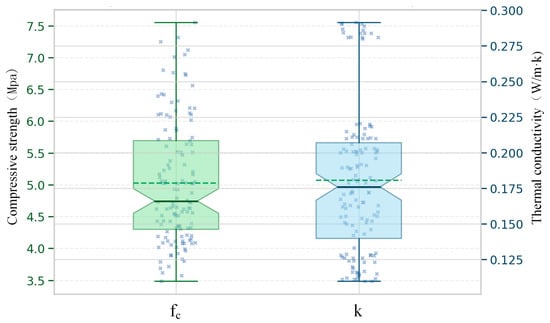

Figure 2 shows the box plots of compressive strength and thermal conductivity. From the perspective of statistical distribution characteristics, the overall values of are concentrated between 4.3 and 5.7 MPa, with a maximum reaching about 7.6 MPa, showing a certain right-skewed distribution; the median value of is about 0.18 W/m·K, mainly distributed in the range of 0.14–0.21 W/m·K, with a minimum reaching 0.11 W/m·K, presenting a slight skewness. This indicates that both indicators have different degrees of skew in their distribution patterns. If the data are fed directly into the model without processing, it will lead to an incomparability of scales and sensitivity to extreme values, thereby affecting the stability and generalization ability of the prediction.

Figure 2.

Boxplots of compressive strength and thermal conductivity of EPS concrete.

To mitigate the above problems, this study introduces log transformation [39] during the data preprocessing stage, and its mathematical form is as follows:

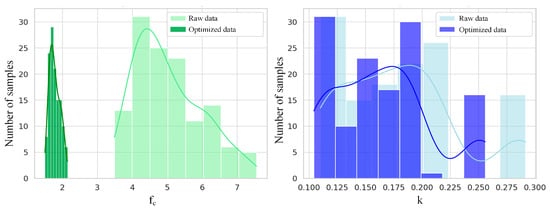

The constant term is used to avoid numerical problems caused by zero values. Log transformation can effectively compress extreme values and improve the symmetry of the distribution while maintaining the relative proportional relationships among variables. The comparative analysis results after log transformation are shown in Figure 3: the skewness of compressive strength decreased from 0.67 to 0.41, with the right-skewed trend significantly weakened and the data distribution becoming more concentrated; the skewness of thermal conductivity decreased from 0.66 to 0.57, and the distribution shape tended to flatten. Compared with the original data, the transformed distribution is closer to a normal distribution, and the impact of extreme values is significantly alleviated. This processing not only improves the numerical stability of the model training process but also reduces the risk of overfitting caused by skewness, thereby enhancing the robustness and reliability of the prediction results.

Figure 3.

Comparison of data distributions of compressive strength and thermal conductivity of EPS concrete before and after log optimization.

2.3. Influencing Factors and Correlation Analysis of EPS Concrete Performance

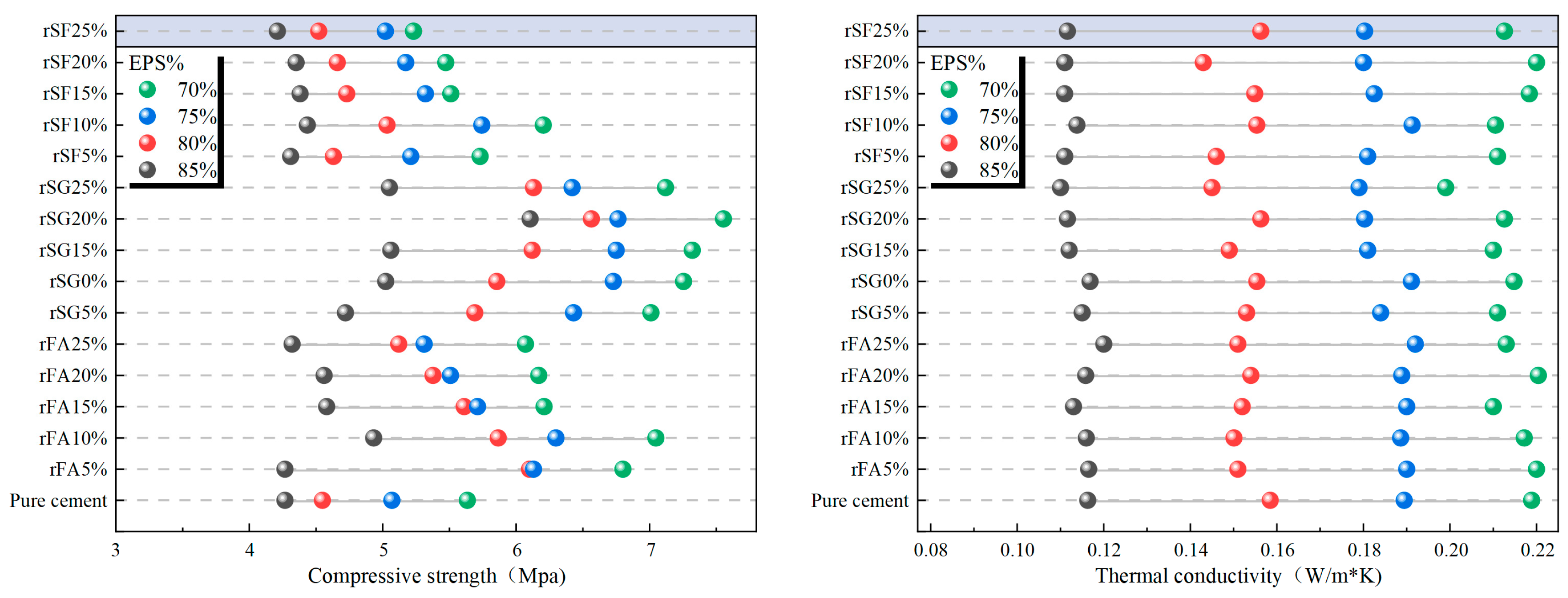

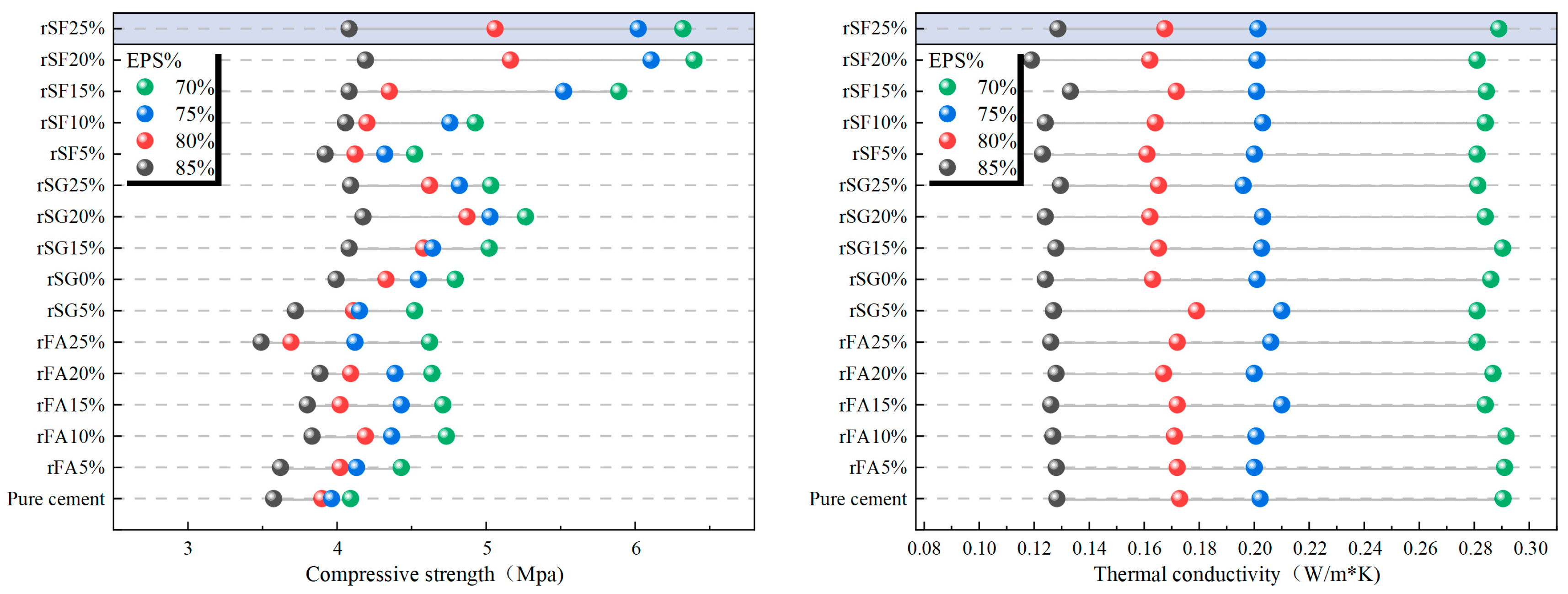

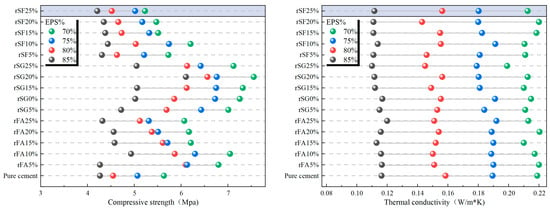

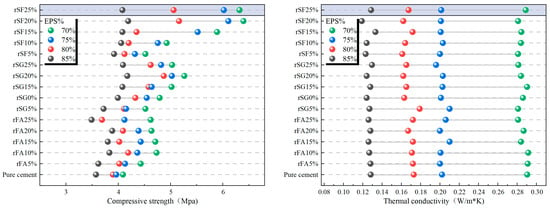

To visually reveal the effects of different mix proportion parameters on the mechanical and thermal properties of EPS concrete, the variations in compressive strength and thermal conductivity with the replacement rate of cementitious materials and EPS content were plotted based on experimental data, as shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5. From Figure 4 and Figure 5, with the increase in EPS volume fraction, the compressive strength of concrete decreases significantly, and the strength reduction becomes more pronounced when the content exceeds 80%. Reducing the EPS particle size alleviates the strength loss to some extent, indicating that fine particles help improve the bonding at the matrix–aggregate interface and increase compactness. The thermal conductivity decreases significantly with increasing EPS content, and the reduction in particle size makes the improvement in thermal insulation performance more pronounced. The replacement rate of cementitious materials has little effect on thermal performance but a great impact on mechanical performance.

Figure 4.

Variation in compressive strength and thermal conductivity of fine-particle EPS concrete with binder replacement ratio and EPS content.

Figure 5.

Variation in compressive strength and thermal conductivity of coarse-particle EPS concrete with binder replacement ratio and EPS content.

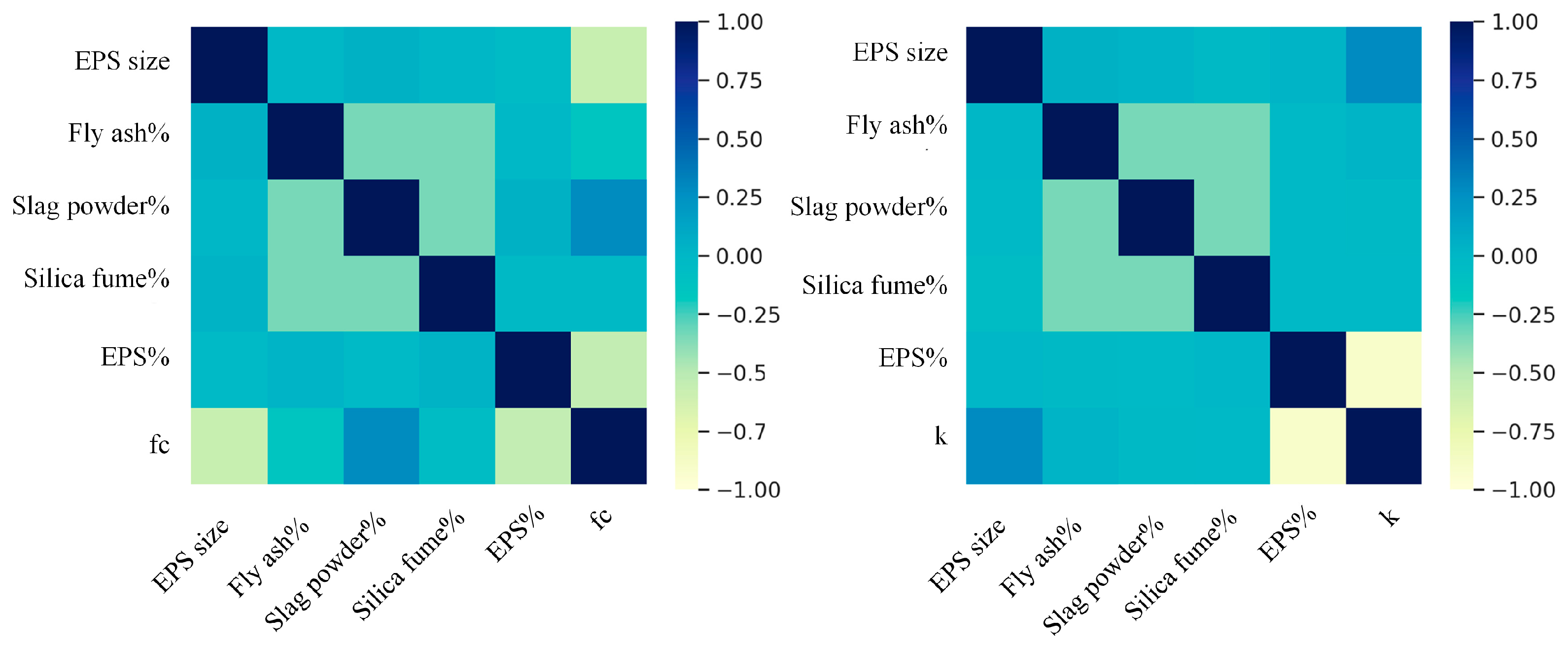

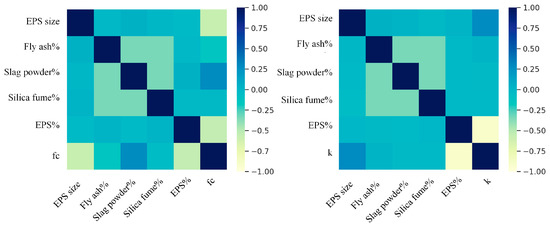

To further quantitatively analyze the influence of each factor on performance, the Pearson correlation coefficients between the main variables and compressive strength and thermal conductivity were calculated (see Figure 6) [40]. The results show that compressive strength has an extremely strong negative correlation with the EPS volume fraction, confirming the inhibitory effect of EPS’s inherent low thermal conductivity and high porosity on heat transfer. EPS particle size has a moderate positive correlation with thermal conductivity, indicating that larger particles are prone to forming thermal bridges due to insufficient compactness of the interfacial transition zone and uneven pore distribution, thereby weakening the insulation effect. The replacement rates of fly ash, silica fume, and slag powder show weak correlations with thermal conductivity, indicating that within the dosage range of this study, mineral admixtures have limited direct influence on thermal performance. To further investigate the statistical relationships between mix design parameters and performance indicators, a Pearson correlation analysis was conducted. The main mix parameters (EPS content, particle size, and mineral admixture ratio) and performance indicators (compressive strength and thermal conductivity) were analyzed. The results showed that EPS content exhibited significant negative correlations with both compressive strength and thermal conductivity (r = –0.54, –0.92; p < 0.001). EPS particle size showed a significant negative correlation with compressive strength (r = –0.58; p < 0.001) and a weak positive correlation with thermal conductivity (r = 0.28; p = 0.001). These findings indicate that the observed performance variations are statistically significant and consistent with the results of the physical mechanism analysis.

Figure 6.

Correlation analysis of factors with compressive strength and thermal conductivity.

In terms of compressive strength, both the EPS volume fraction and particle size show significant negative correlations, reflecting that the introduction of a large number of low-strength EPS particles and pores weakens the load-bearing capacity of the matrix. The slag powder replacement rate has a positive correlation with compressive strength, indicating that an appropriate amount of slag powder can improve the matrix structure and enhance strength through potential pozzolanic reactions and micro-filling effects; in contrast, the linear correlations of fly ash and silica fume replacement rates with compressive strength are not obvious, indicating their limited strength contribution under the experimental conditions of this study. In summary, the EPS volume fraction and particle size are the dominant factors affecting the mechanical and thermal properties of EPS concrete, and slag powder can provide a compensating effect on strength within a certain replacement range.

3. Machine Learning Algorithms and Model Optimization

3.1. Random Forest Baseline Model for Predicting EPS Concrete Performance

Random forest was proposed by Breiman [41] and is a nonparametric statistical model based on the idea of ensemble learning (Figure 1). Its core principle is to construct and integrate a large number of decision trees, introducing bootstrap sampling and random feature selection strategies during the training process, thereby effectively reducing the risk of overfitting, which occurs easily in a single decision tree, and improving the model’s adaptability and robustness to high-dimensional features. With this dual random mechanism, RF shows excellent nonlinear fitting and generalization ability when dealing with EPS concrete data with many variables and significant interaction effects. It can accurately capture the potential relationships between key performance indicators such as compressive strength, thermal conductivity, and material parameters, providing a reliable data-driven foundation for subsequent performance optimization and multi-objective design.

3.2. Physics-Informed Approach (PIA) and Its Application in the Prediction Model

In the EPS concrete system, there are clear monotonic relationships between some input variables and output performance. As the EPS content increases, the compressive strength shows a decreasing trend while the thermal conductivity decreases. If relying only on data-driven methods, the model may produce predictions in local intervals that do not conform to the mechanism, weakening extrapolation ability and interpretability. To ensure that the prediction results comply with known physical laws, this study introduces the physics-informed approach (PIA, Physics-Informed Framework) [42] training for the random forest surrogate model. The constraint is achieved by adding a directional penalty term to the objective function. Let denote the predicted value, when the input variable has a monotonically increasing relationship with the output:

If it is monotonically decreasing, the constraint condition is

where is the model prediction value. To reflect this constraint in the optimization process, a directional penalty term is defined as follows:

where , respectively represent the sets of variables with prior relationships of increasing and decreasing.

The final optimization objective function is

where is the basic prediction loss function, and is the balance coefficient used to trade off between prediction accuracy and physical consistency.

In this study, to avoid the loss of physical consistency caused by a completely unconstrained setting, the value range of is set to . Under small-sample conditions, is set to 0.2 to avoid underfitting caused by overly strong constraints; when the sample size is larger or the prior relationships are clear, can be appropriately increased to enhance the consistency of the prediction results with physical laws. To ensure reproducibility, the implementation process of the physics-informed penalty within the Random Forest framework is presented in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Physics-Informed Random Forest (PIA-RA), concise version |

| Input: dataset , monotonic priors , weight , step . |

| Output: trained RF , best hyperparams . |

| Split train 70%/test 30%; apply preprocessing fitted on train. |

| Use 5-fold CV on train; for each hyperparam set : |

| Fit RF with on CV-train; predict on CV-val → . |

| For each feature with prior, compute finite diff . |

| Penalty . |

| Fold loss ; pick . |

| Retrain RF on full train with ; evaluate on test (R2, RMSE) + violation rate. |

| Return , , metrics. |

3.3. Global Hyperparameter Optimization of Random Forest Based on the Firefly Algorithm

Random forest has good fitting ability and generalization performance when dealing with complex and highly nonlinear datasets of EPS concrete. However, the prediction performance of random forest is highly sensitive to hyperparameters, and relying only on empirical settings often makes it difficult to obtain the optimal combination. To solve this problem, this study introduces the Firefly Algorithm (FA). FA is a swarm intelligence optimization method proposed by Yang [43], which simulates the attraction behavior of fireflies based on light intensity to dynamically update individual positions, enabling it to escape local optima and achieve efficient global search. This study determined the algorithm parameter settings by combining the empirical parameter ranges reported in previous studies with preliminary sensitivity analysis [43]. The population size was set to 30, and the maximum number of iterations to 100. The initial attractiveness β0 and light absorption coefficient γ were set to 1.0 and 0.5, respectively. The random perturbation factor α was initialized at 0.2 and linearly decreased with iterations to maintain a balance between global exploration and local exploitation. The search ranges for the random forest hyperparameters were defined as n_estimators ∈ [100, 500], max_depth ∈ [3, 15], and min_samples_split ∈ [2, 10]. This parameter configuration demonstrated good convergence stability and global optimization capability in multiple tests. In this study, FA is used to automatically optimize the hyperparameters of RF, thereby obtaining more reasonable parameter configurations and improving the prediction accuracy and robustness of the model for compressive strength and thermal conductivity. In the -th iteration, assuming that the positions of the -th and -th fireflies are and , respectively, their movement rule can be expressed as follows:

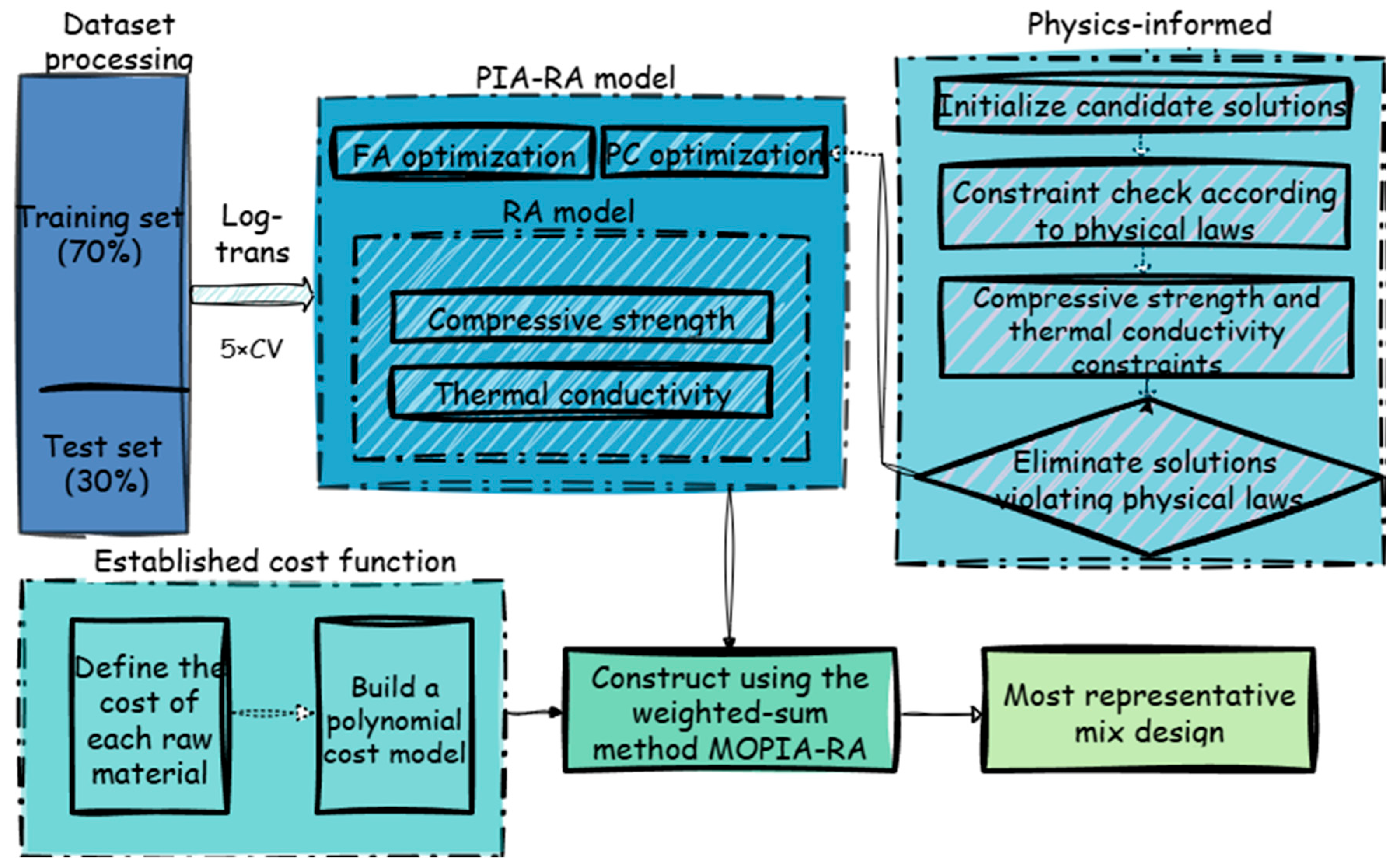

where represents the Euclidean distance between two fireflies; denotes the maximum attractiveness when gamma is the light absorption coefficient, reflecting the rate at which attractiveness decays with distance; is the random disturbance factor used to maintain the diversity of the population; and is a random vector following a Gaussian or uniform distribution within the range [0, 1]. To more intuitively present the positioning of the constructed prediction model within the overall study, Figure 7 shows the overall technical framework of this research.

Figure 7.

Framework of the proposed PIA-RA and MOPIA-RA based mix design methodology.

3.4. Evaluation Metrics for Compressive Strength and Thermal Performance of EPS Concrete Prediction Model

To ensure that the prediction model can accurately reflect the variation patterns of compressive strength and thermal performance, as well as quantify the error level and enable comparison, three evaluation metrics were comprehensively adopted: the coefficient of determination , root mean square error , and mean absolute error . These metrics can systematically evaluate the model’s performance from different perspectives, including overall trend, absolute deviation, and relative error, thereby avoiding one-sided conclusions caused by relying on a single metric [44,45,46]. Their mathematical expressions are as follows:

where is the measured value of the -th sample, is the model prediction value, represents the average of the measured values, and is the total number of samples. is used to measure the explanatory ability of the model for the variation trend of the experimental data and is the most commonly used goodness-of-fit indicator. Its value ranges from [0, 1], and the closer it is to 1, the higher the degree of fit between the prediction results and the measured data. measures the average deviation between the predicted values and the measured values, reflecting the overall fluctuation level of the prediction error. calculates the mean absolute value of the prediction errors, reflecting the overall deviation level and being less affected by extreme values.

4. Verification and Interpretability Analysis of the EPS Concrete Performance Prediction Model

4.1. Accuracy Evaluation and Stability Analysis of the EPS Concrete Performance Prediction Model

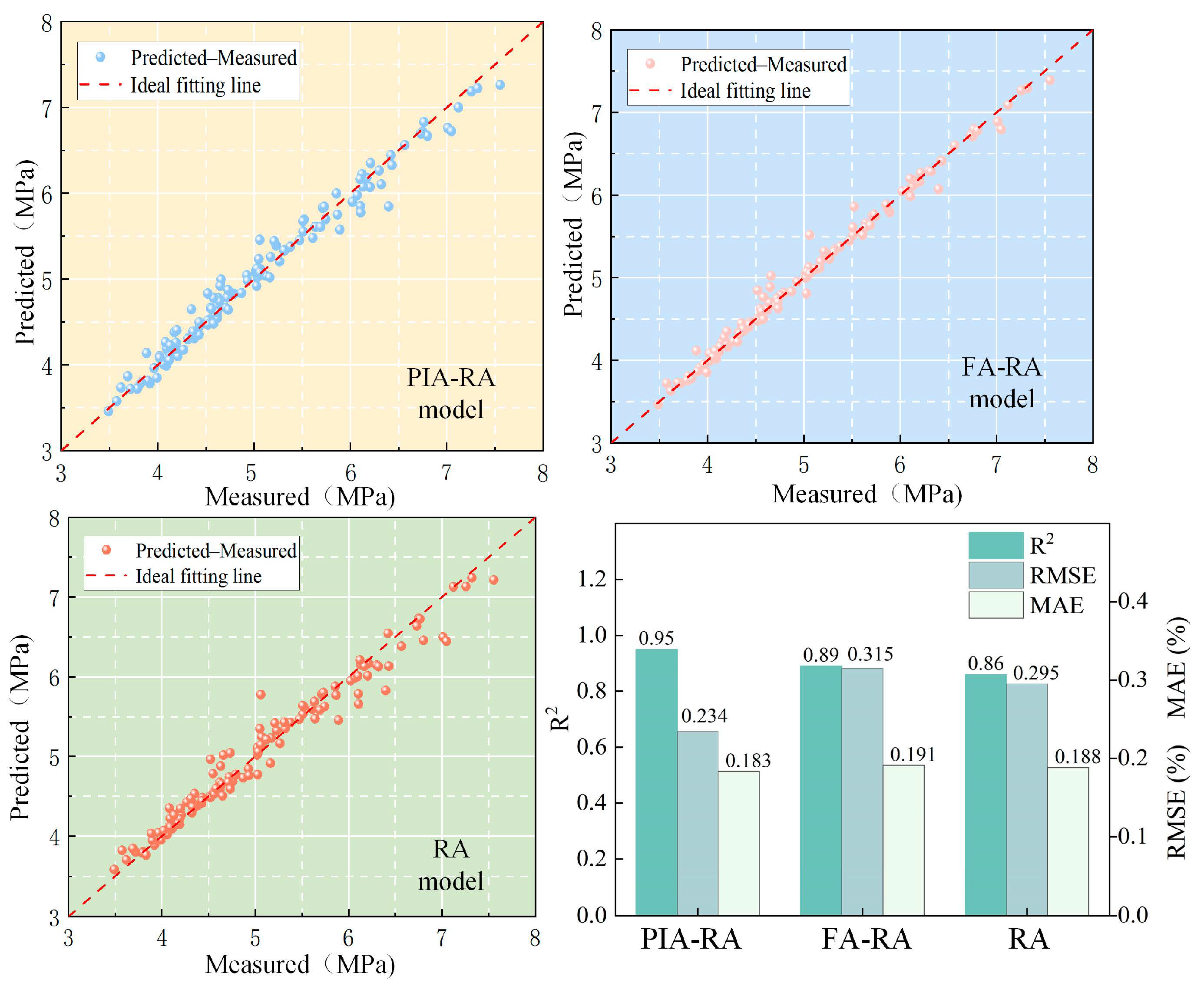

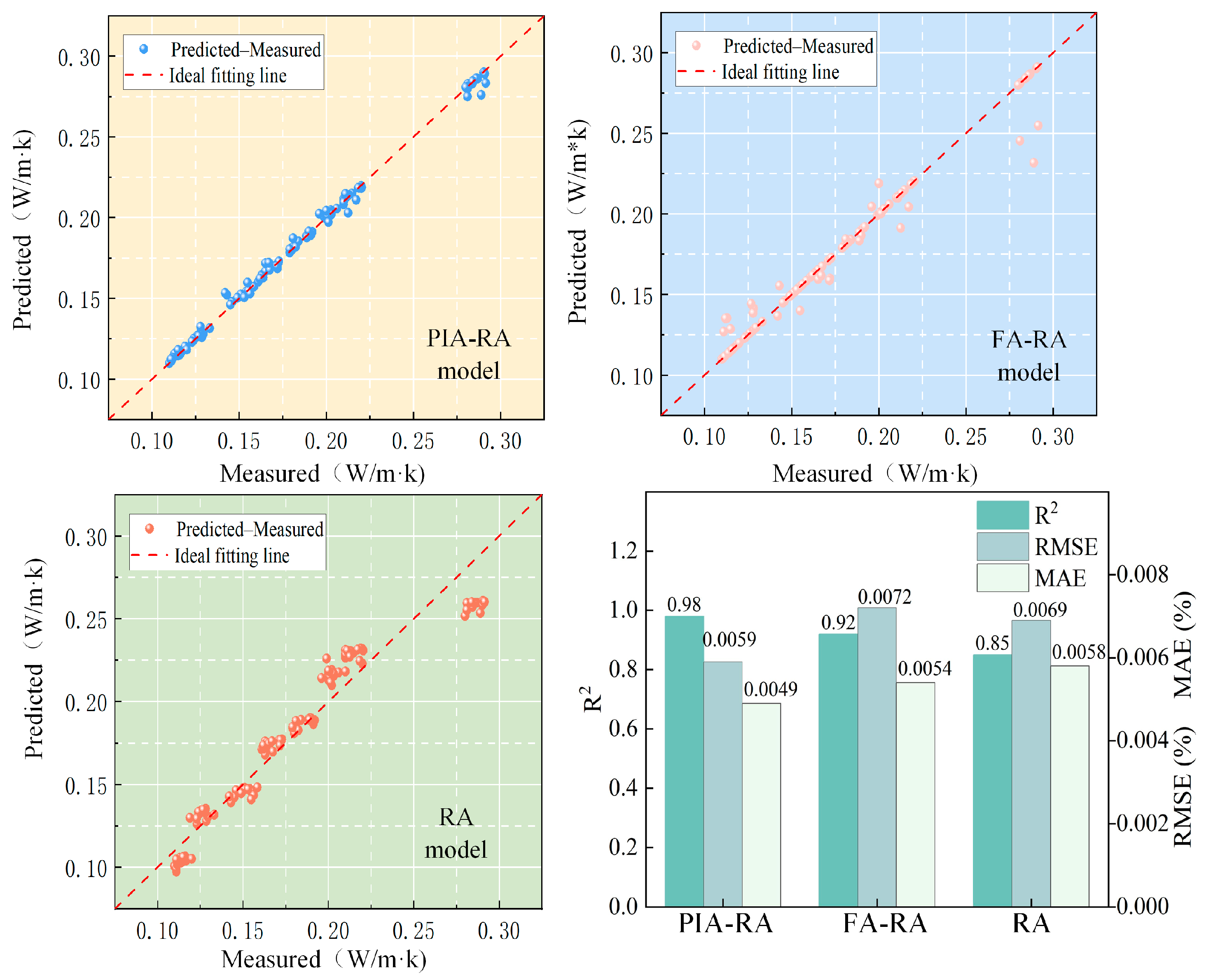

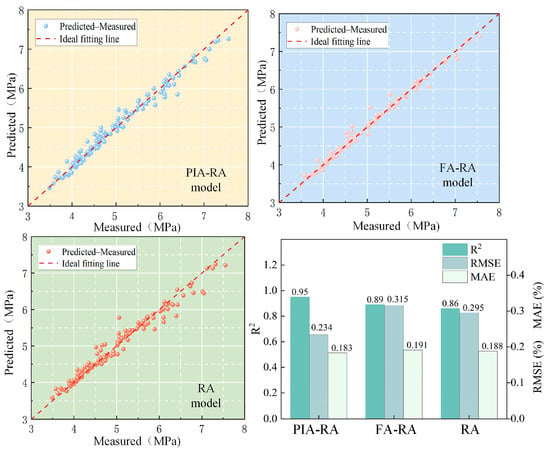

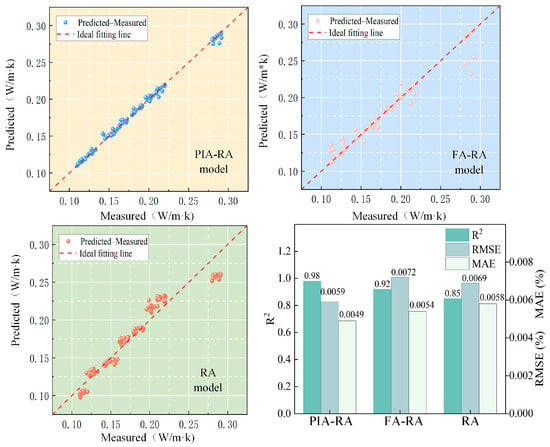

To ensure that the constructed EPS concrete prediction model can provide a reliable foundation for subsequent multi-objective optimization, this study compared three types of models: the basic random forest RA, the FA-RF optimized by the Firefly Algorithm, and the PIA-FA further combined with physics-informed constraints. By comparing the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE), the accuracy and robustness of each model in predicting compressive strength and thermal conductivity were systematically evaluated, and five-fold cross-validation was used to verify the generalization ability.

Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the comparison of prediction accuracy among different models. The results indicate that the PIA-RA model performs significantly better than FA-RA and the basic RA in both compressive strength and thermal conductivity indicators. Although FA-RA improves prediction accuracy through hyperparameter optimization, due to the lack of constraints from physical priors, it is still prone to systematic bias in regions with sparse data or extreme values; the basic RA relies entirely on data-driven learning and lacks constraints on complex variable interactions and nonlinear relationships, resulting in larger errors.

Figure 8.

R2, RMSE, and MAE values of different models for compressive strength prediction.

Figure 9.

R2, RMSE, and MAE values of different models for thermal conductivity prediction.

These differences mainly stem from the physical prior constraints explicitly embedding known material laws of EPS concrete into the model—such as the increase in EPS volume fraction reducing thermal conductivity and particle size variation affecting interfacial compactness—thereby limiting the learning range to a reasonable feasible domain and reducing ineffective fitting and abnormal extrapolation. In addition, the Firefly Algorithm globally optimizes the hyperparameters of the random forest, effectively balancing model bias and variance and further improving the robustness of predictions. In contrast, although FA-RA can automatically optimize parameters, it still tends to overfit and produce extrapolation bias in sparse or extreme data regions due to the lack of physical constraints; the non-optimized basic RA is even less capable of capturing complex variable-coupling relationships, leading to the lowest prediction accuracy.

To further verify the robustness and generalization ability of the optimal model, this study conducted five-fold cross-validation on the PIA-RA model [47]. The dataset in this study was divided into a training set and an independent test set at a ratio of 7:3. During the hyperparameter optimization process using the Firefly Algorithm (FA), only the training set was used for parameter updating. After optimization, the model’s generalization ability was evaluated on unseen test data. In addition, five-fold cross-validation (CV) was employed within the training set to further verify the robustness of the model. To prevent data leakage during cross-validation, the validation subset in each fold was strictly excluded from the corresponding training subset, and all normalization and logarithmic transformations were independently performed within each training fold to ensure the independence of the validation process. The results in Table 4 and Table 5 show that in compressive strength prediction, the R2 values remained stable in the range of 0.94–0.96, with an average of 0.95 ± 0.01, and the corresponding RMSE and MAE were 0.234 ± 0.006 and 0.183 ± 0.002, respectively. This indicates that the model can maintain high fitting accuracy and low error levels across different folds without significant overfitting or underfitting. In thermal conductivity prediction, the R2 values remained at 0.97–0.98, with an average of 0.98 ± 0.01, and the RMSE and MAE were 0.0059 ± 0.0002 and 0.0047 ± 0.0002, respectively. The error distribution was stable and extremely small in magnitude, indicating that the model can not only capture overall trends but also accurately depict subtle differences. In summary, the PIA-RA model demonstrated the highest correlation, the smallest errors, and the best robustness

Table 4.

Five-fold CV results of PIA-RA model for compressive strength.

Table 5.

Five-fold CV results of PIA-RA model for thermal conductivity.

To verify the predictive performance of the proposed model, three commonly used machine learning algorithms—Support Vector Regression (SVR), XGBoost, and CatBoost—were selected as baseline models for comparison using the same dataset and evaluation metrics. As shown in Table 6, the proposed PIA-RA model outperformed the baseline models in predicting both compressive strength and thermal conductivity (R2 = 0.89–0.94), with lower RMSE and MAE values. These results demonstrate that the Random Forest model enhanced with physical constraints and Firefly Algorithm optimization significantly improves prediction accuracy, generalization capability, and physical consistency.

Table 6.

Performance comparison of different machine learning models for predicting compressive strength and thermal conductivity of EPS concrete.

4.2. Interpretability Analysis of the EPS Concrete Performance Prediction Model

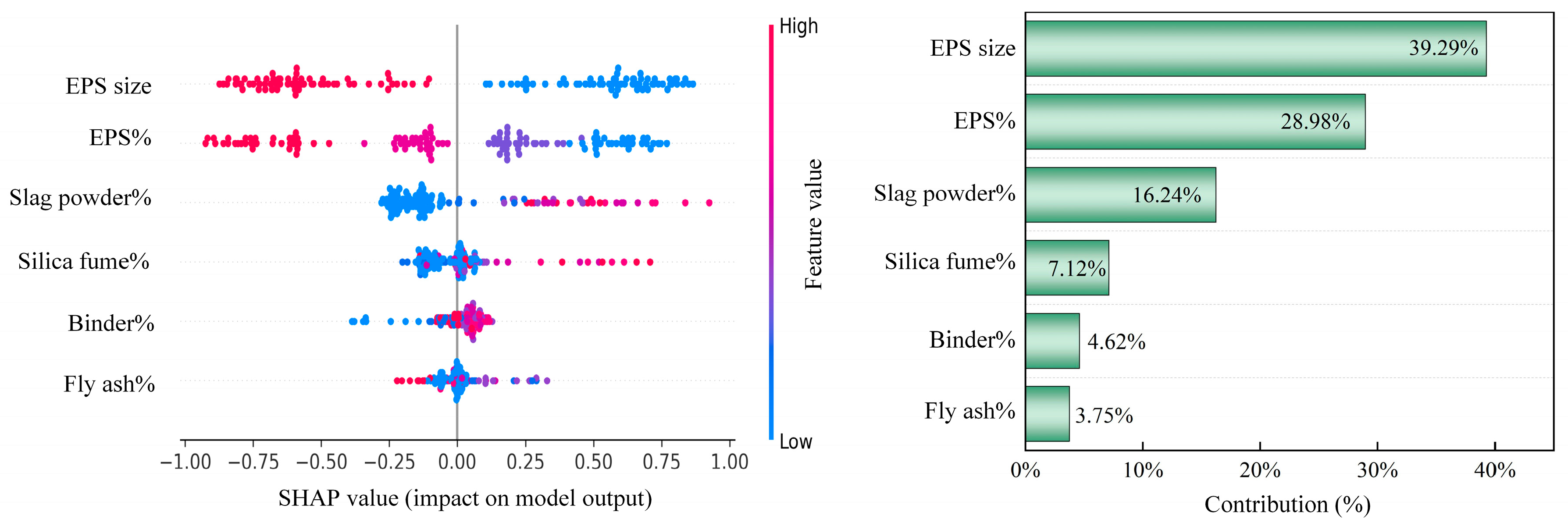

4.2.1. Feature Importance Analysis Based on SHAP

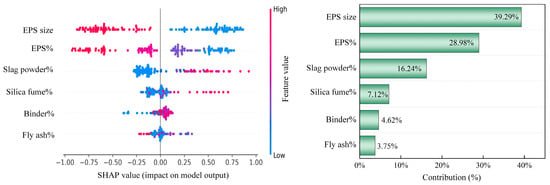

The PIA-RA model shows high accuracy and robustness in predicting the compressive strength and thermal performance of EPS concrete, but its internal decision-making process is still difficult to explain, which limits its guidance for material design. Therefore, the SHAP method was introduced to interpret prediction results, quantitatively evaluate the influence of each variable, and extract key design patterns [48].

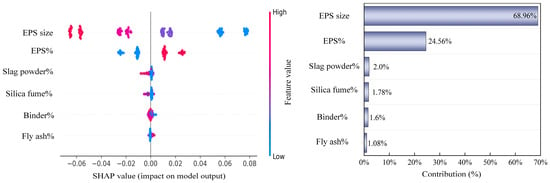

As shown in Figure 10, feature importance interpretation of the model’s compressive strength prediction results was conducted based on the SHAP method. The vertical axis represents design variables, the horizontal axis represents SHAP values, the zero point corresponds to the mean prediction of the model, and the color bar reflects the magnitude of variable values. The results show that EPS particle size and content are the dominant factors affecting compressive strength. When the particle size is small, the SHAP values are mostly positive, indicating that it can effectively improve compressive strength; when the particle size is large, the SHAP values turn negative, indicating a decrease in strength. Increasing EPS content leads to overall negative SHAP values, indicating that excessive EPS particles weaken mechanical performance. In contrast, the effects of slag powder, silica fume, fly ash, and the replacement rate of cementitious materials on compressive strength are relatively small. The contribution ranking further confirms this pattern: EPS particle size and content contributed 68.96% and 24.56%, respectively, far higher than the slag powder replacement rate (2.0%), silica fume replacement rate (1.78%), cementitious materials replacement rate (1.6%), and fly ash replacement rate (1.08%). In summary, the EPS particle content is the key factor determining compressive strength.

Figure 10.

Feature importance analysis of compressive strength prediction model (SHAP).

As shown in Figure 11, further SHAP analysis was conducted on the thermal conductivity prediction results. The results show that EPS content has the most significant influence on thermal conductivity. When the EPS content is high, the SHAP values are mainly negative, indicating reduced thermal conductivity and enhanced insulation performance; when the content is low, the SHAP values are positive, indicating increased thermal conductivity and weakened insulation performance. EPS particle size also plays an important role in thermal performance: smaller particle sizes correspond to negative SHAP values, indicating a decrease in thermal conductivity; larger particle sizes correspond to positive values, indicating an increase in thermal conductivity. The effects of slag powder, silica fume, fly ash, and cementitious material replacement rate on thermal conductivity are limited, with contribution proportions all less than 5%. Overall, EPS particle size and content not only determine the evolution patterns of mechanical properties but are also the core factors affecting thermal performance.

Figure 11.

Feature importance analysis of thermal conductivity prediction model (SHAP).

In summary, the SHAP method revealed the dominant role of EPS particle-related parameters in multi-objective performance. The results show that EPS particle size and content are the most important variables affecting compressive strength and thermal conductivity, while mineral admixtures and the replacement rate of cementitious materials only play a secondary regulatory role. This conclusion not only provides interpretability support for model predictions but also offers a basis for optimizing the mix design of EPS concrete.

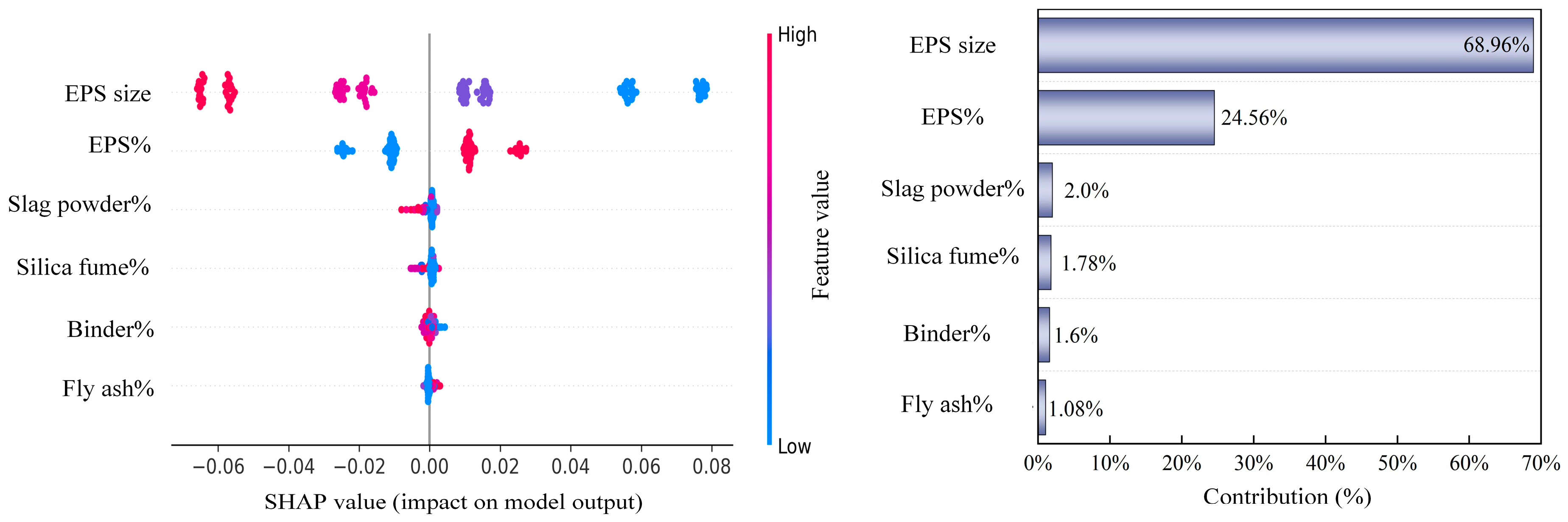

4.2.2. Feature Dependence Analysis Based on SHAP

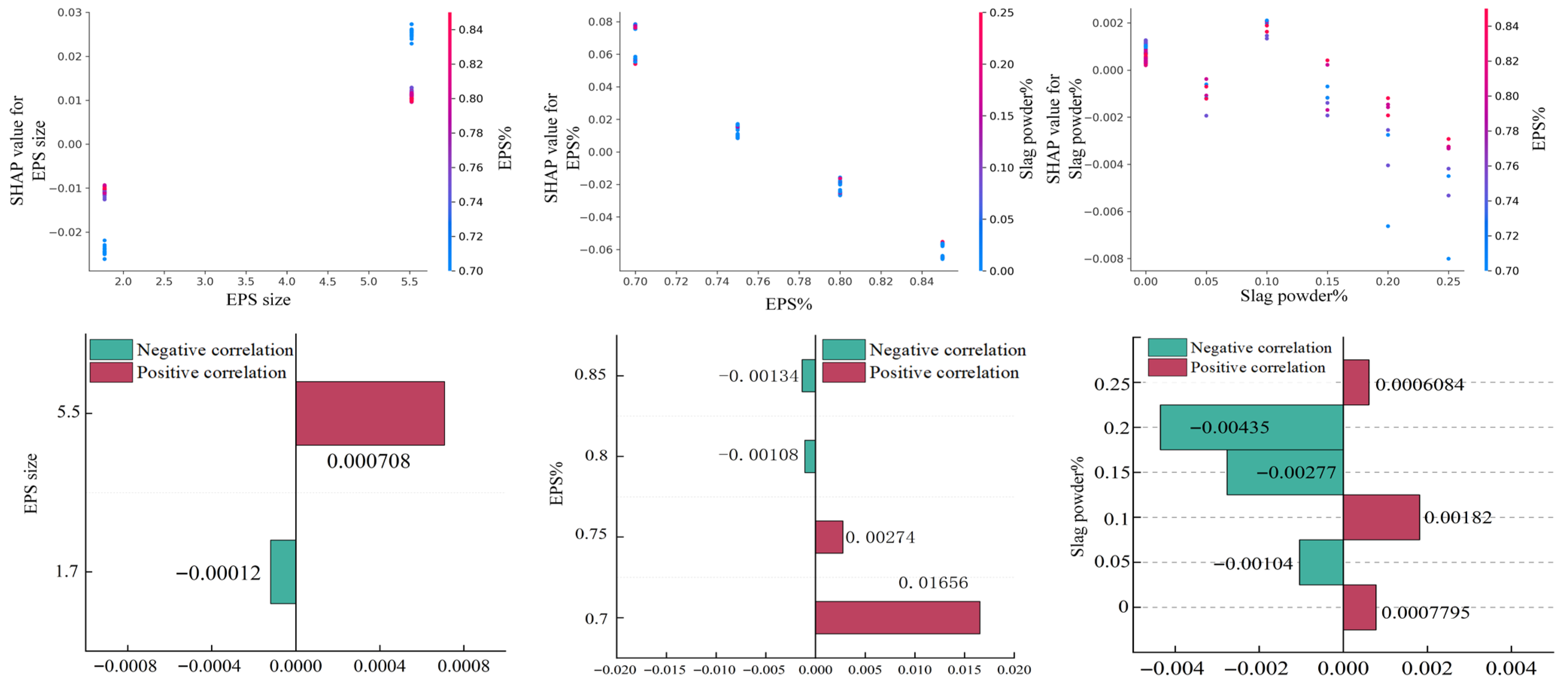

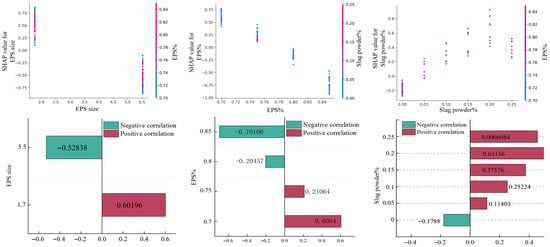

To further reveal the nonlinear effect patterns of each design variable on the performance of EPS concrete, SHAP feature dependence analysis was performed on the trained model. This method can simultaneously show the relationship between feature values and their marginal contributions to the output and use color mapping to reflect the interactions of other variables, thus providing more interpretable analysis results for the model.

As shown in Figure 12, the influence patterns of the main design variables on compressive strength are relatively clear. First, EPS particle size has the greatest impact on compressive strength. When the particle size is small, about 1.7 mm, the SHAP values are generally positive, indicating that the compressive strength is higher than the average level; when the particle size increases to 5.5 mm, the SHAP values turn negative, with a contribution value reaching −0.52, indicating that larger particle sizes reduce the load-bearing capacity of the concrete. Second, EPS content shows a bidirectional effect: in the low content range, compressive strength increases slightly, but as the content increases to above 0.8, the SHAP values become overall negative, indicating that excessive lightweight aggregate destroys the compactness of the structure, leading to strength reduction. The slag powder replacement rate shows a positive contribution to compressive strength; within the range of 0.1–0.25, the SHAP values gradually increase, with the maximum contribution reaching 0.63136, showing the potential of mineral admixtures to improve compressive strength.

Figure 12.

Feature interaction analysis of compressive strength prediction model (SHAP).

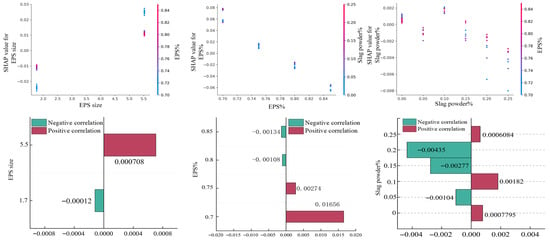

As shown in Figure 13, the variation pattern of thermal conductivity is different from that of compressive strength. EPS particle size and content are still the dominant variables, but their effect directions show differences. When the particle size is small (1.7 mm), the SHAP values are significantly negative, indicating reduced thermal conductivity; when the particle size increases to 5.5 mm, the SHAP values are significantly positive, with the contribution value reaching 0.000708, indicating that smaller particles can reduce heat transfer and improve insulation performance. The influence of EPS content is more prominent; as the content increases, the SHAP values gradually decrease, and near 0.85, the contribution value reaches −0.70106, indicating that increasing the volume fraction of lightweight aggregate significantly reduces thermal conductivity. Different from the compressive strength results, the influence of slag powder replacement rate is weak; the SHAP value distribution is concentrated and of limited magnitude, showing only a slight negative effect at higher replacement rates.

Figure 13.

Feature interaction and dependence analysis of thermal conductivity prediction model (SHAP).

In summary, the SHAP feature dependence analysis shows that EPS particle size and content are the key variables affecting compressive strength and thermal performance, and their variation patterns, respectively, determine the dominant trends of mechanics and thermal properties. Meanwhile, the slag powder replacement rate can play a certain optimizing role in compressive strength but has limited contribution to thermal conductivity. This result reveals the trade-off relationship between mechanical and thermal performance and also provides data support and theoretical basis for subsequent multi-objective optimization design.

5. Mix Proportion Design and Optimization of EPS Concrete

The mix proportion design of EPS concrete needs to not only meet excellent thermal performance but also to take into account mechanical performance and economic feasibility. This process is essentially a multi-objective optimization problem [30]. Therefore, in this study, the compressive strength, thermal conductivity, and direct material cost of EPS concrete were taken as the comprehensive optimization objectives, and the PIA-RA prediction model was used as a surrogate model to construct the multi-objective optimization MOPIA-RA model, achieving an overall balanced design of performance and cost.

5.1. Establishment of the MOPIA-RA Model

5.1.1. Definition of Objective Functions and Material Cost Modeling

To balance the mechanical performance, thermal performance, and economic feasibility of EPS concrete, this study takes the compressive strength , thermal conductivity , and direct material cost of EPS concrete as the optimization objectives. The predicted values of compressive strength and thermal conductivity are output by the surrogate model PIA-RA, which is based on RA and embedded with physical priors; the material cost is evaluated by establishing a direct cost equation. Therefore, the objective vector is expressed as follows:

where is the EPS volume fraction, is the EPS particle size, and are the single replacement rates of fly ash, slag powder, and silica fume, respectively. In the equation, both refer to the model’s predicted outputs. The material cost objective is expressed as follows:

Each item is composed of quantity × unit price: . Where are the unit prices of cement and each mineral admixture, and is the unit price per volume of EPS; the specific values are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Unit cost of each material.

5.1.2. Constraint Setting and Feasible Domain Definition

To ensure the physical feasibility of the mixed proportions and maintain consistency with the experiments, this study set three types of constraints in the optimization model: volume closure constraint, proportion and mutual exclusivity constraint, and value range constraint.

- (1)

- Volume closure constraint

Under a fixed mixing system, the sum of the volumes of each component per unit volume should be consistent with the target molded volume. Considering density fluctuations and measurement errors, a slight tolerance is allowed for volume closure:

where is the EPS volume fraction; are the amounts of cement and each mineral admixture per unit volume; and are their corresponding densities.

- (2)

- Proportion and Mutual Exclusivity Constraints

To avoid excessive use of a single component and to ensure the single replacement setting, restrictions are imposed on the replacement rates and mutual exclusivity relationships:

where is the upper limit of the replacement rate; denotes the indicator function, which equals 1 if the fly ash content is greater than 0, and 0 otherwise, used to express the mutual exclusivity constraint of having at most one non-zero value.

- (3)

- Value Range Constraints

Based on the data coverage domain, the range of EPS content is specified, and the EPS particle size is given discrete values, where = 0.70, = 0.85:

To ensure the reliability of interpolation, the variable values do not exceed the support domain of the training data, thereby avoiding the amplification of uncertainties introduced by extrapolation.

To define the optimization design space, Table 8 summarizes the main decision variables and their corresponding value ranges in the MOPIA-RA framework. All Pareto-optimal solutions satisfy the specified constraints for compressive strength (), thermal conductivity (), and material cost (), confirming that the proposed EPS concrete optimization design schemes are feasible in terms of both performance and economic efficiency.

Table 8.

Input variables and their variation ranges used in the EPS concrete modeling process.

5.1.3. Weighted-Sum-Based Multi-Objective Optimization

To find reasonable trade-off solutions among compressive strength, thermal conductivity, and material cost, this study used the Weighted-Sum Method (WSM) within the MOPIA-RA framework to solve the multi-objective optimization problem [49]. To ensure the rationality of weight allocation in the weighted sum method, the determination of and was based on a combination of model sensitivity analysis and engineering judgment. By analyzing the variance contribution of each objective (compressive strength, thermal conductivity, and cost) to the overall performance and incorporating the engineering priorities of structural safety, thermal insulation performance, and economic efficiency, a balanced weighting scheme was established. This approach allows the weighted sum method to maintain both data-driven rigor and engineering relevance. This method assigns weights to each objective function and converts the original three-objective problem into a series of solvable single-objective problems, thereby obtaining the Pareto optimal solution set with relatively low computational complexity, expressed as follows:

where , , and cost represent compressive strength, thermal conductivity, and cost, respectively, and is the corresponding weight factor. By systematically adjusting the weights, a series of optimized solutions can be obtained, which approximately form the Pareto frontier [50]. In the solving process, the weight space is first uniformly sampled; the trained PIA-RA surrogate model is then used to quickly calculate the three indicators under different mix proportions, and the Firefly Algorithm is employed to search for the optimal solution under each weight combination. Compared with the exhaustive search method, this strategy significantly reduces the number of searches while ensuring the diversity and accuracy of the solutions. The final Pareto frontier depicts the optimal balance between performance and cost.

5.2. Multi-Objective Decision-Making Method and Scheme Selection

To further screen and rank the Pareto solution set obtained from multi-objective optimization and determine the optimal EPS concrete mix design scheme, the TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution) method [51] was used. The optimal scheme should be simultaneously close to the scheme composed of the best values of each objective function and far from the scheme composed of the worst values of each objective function. Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation can be achieved by calculating the relative distances between each candidate scheme and the positive and negative ideal solutions. The specific calculation steps are as follows:

where represents the performance value of scheme under the -th objective; and represent the positive and negative ideal solutions of the -th objective, respectively; and represent the Euclidean distances between scheme iii and the positive and negative ideal solutions, respectively; and is the comprehensive evaluation score of scheme . Specifically, first, the objective matrix of candidate schemes is established based on the objective functions (maximizing compressive strength, minimizing thermal conductivity, and minimizing material cost); then, the optimal and worst values of each objective are determined; next, the distances between each candidate scheme and the ideal solutions are calculated; finally, the comprehensive evaluation index is obtained using Equation (18). The value of ranges between 0 and 1, and the larger the value, the closer the scheme is to the optimal solution and the better the overall performance. By ranking the values of all Pareto solutions, the trade-off effect of different mix schemes among multiple objectives can be objectively reflected, thereby identifying the optimal concrete mix design among multiple candidates. This process not only avoids the bias caused by relying solely on subjective weight allocation but also ensures that the selected scheme achieves a better balance among strength, thermal performance, and economic feasibility, which is of great significance for guiding practical engineering mix design.

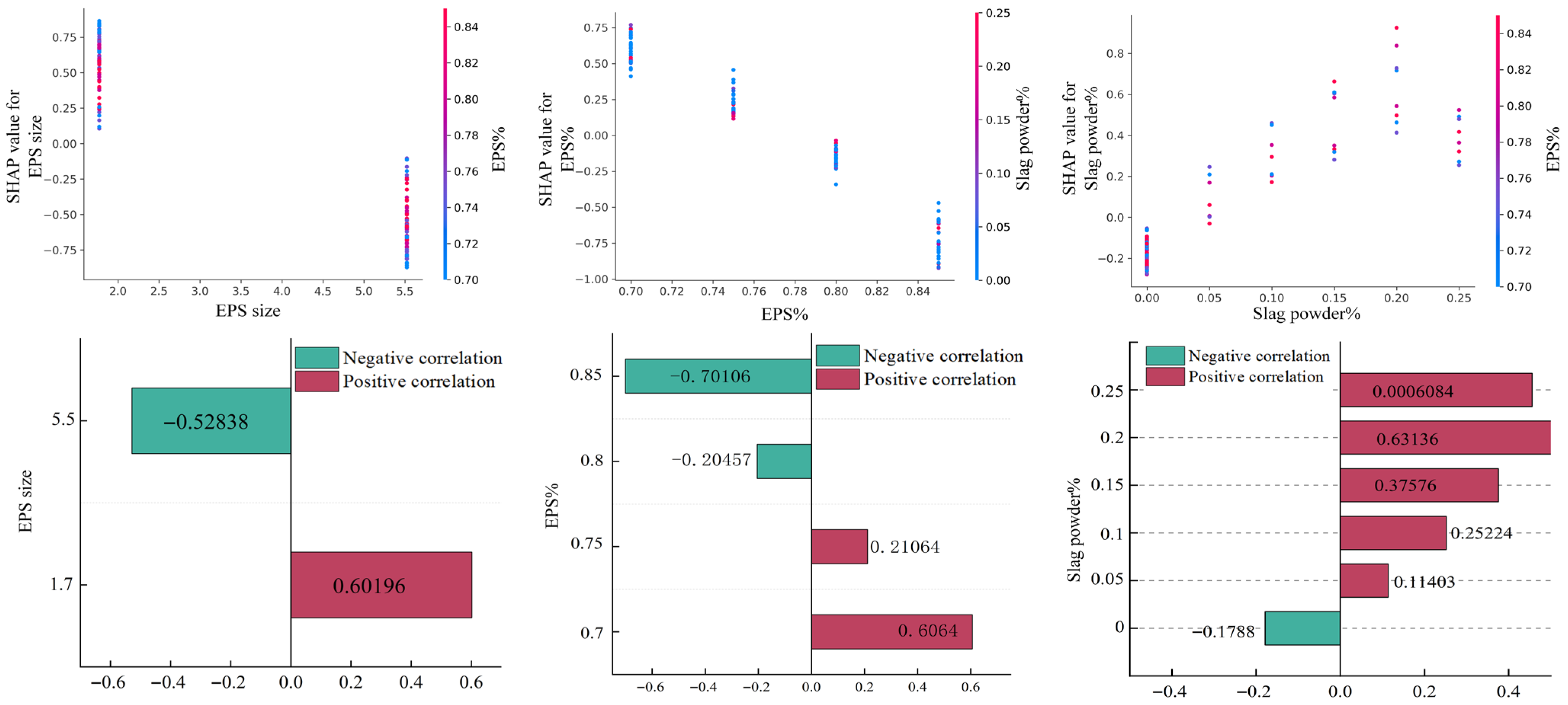

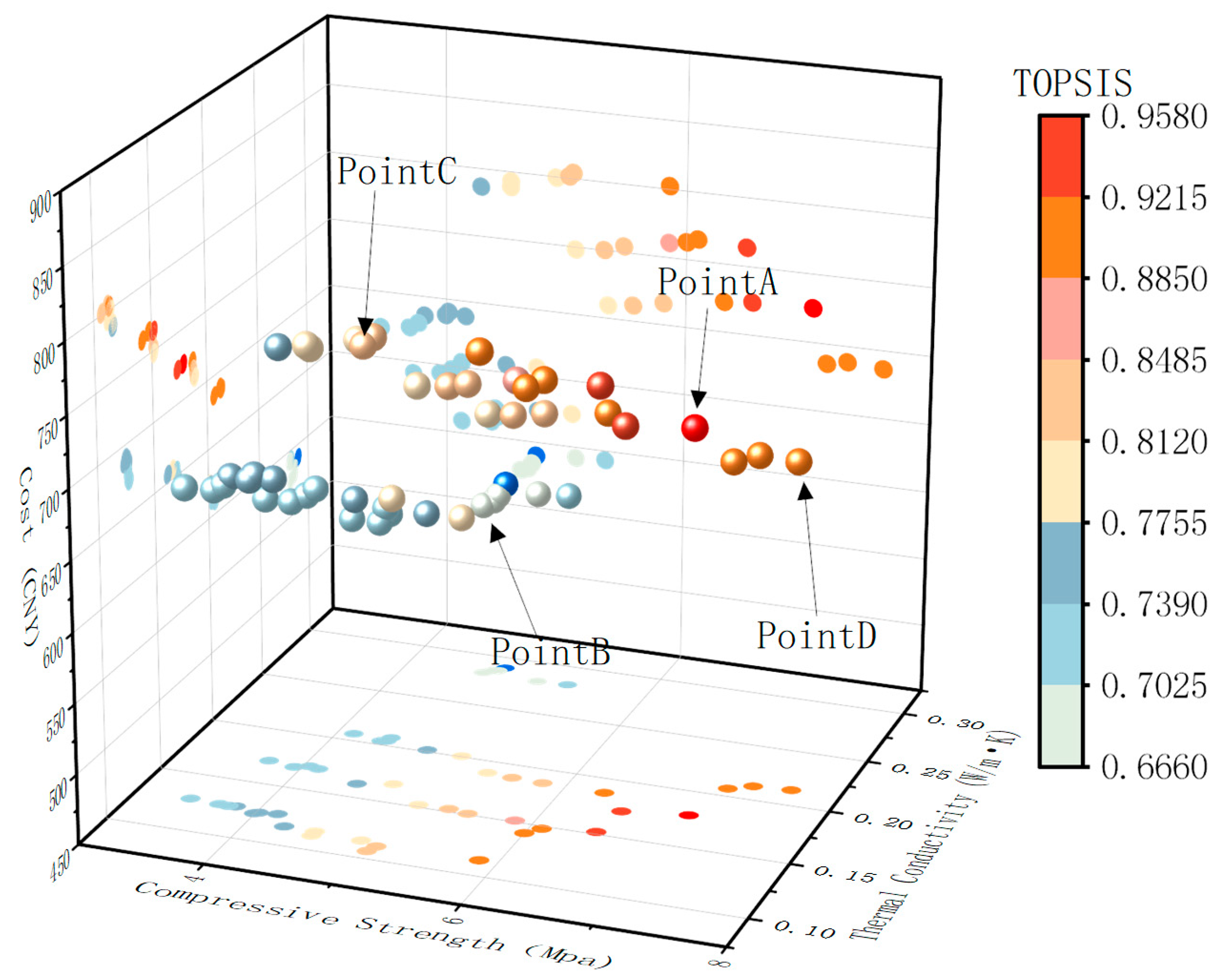

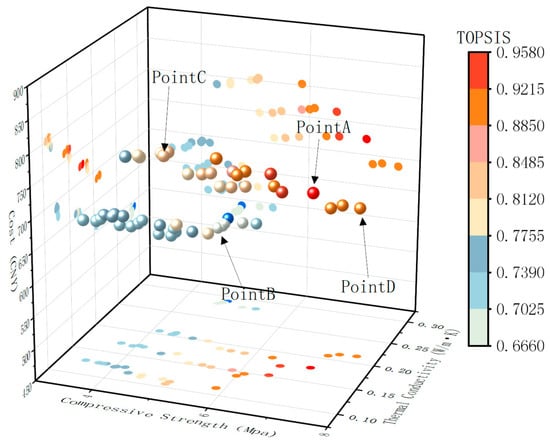

5.3. Analysis of Mix Proportion Optimization Results Based on the MOPIA-RA Model

Based on the high-accuracy prediction model PIA-RA, this study constructed a multi-objective optimization model aiming to minimize thermal conductivity , maximize compressive strength , and simultaneously minimize material cost . The obtained Pareto frontier clearly reveals the trade-off relationships among the three indicators, verifying the effectiveness and applicability of the MOPIA-RA model in multi-objective optimization. The results show a significant negative correlation between compressive strength and thermal performance: increasing strength is usually accompanied by an increase in thermal conductivity, thereby weakening the insulation effect. Meanwhile, the material cost is mainly affected by the types of admixtures and the EPS particle size; when slag powder is used to replace cement or fine EPS particles are selected, the concrete performance can be improved to some extent, but the cost increases significantly. Overall, the 52 non-dominated solutions generated by optimization are distributed along the Pareto frontier and present good nonlinear patterns, indicating that the model can effectively capture the complex characteristics among strength, thermal conductivity, and cost.

As shown in Figure 14, among the 52 Pareto non-dominated solutions obtained, four points A–D can be regarded as representative typical schemes. Point A is the optimal solution by TOPSIS comprehensive evaluation with = 7.03 MPa, = 0.178 W⋅m−1⋅K−1, and = 725 CNY/m3, achieving a favorable balance among strength, thermal performance, and cost, thus showing the best overall performance. Point B corresponds to the lowest-cost solution with = 577 CNY/m3, having an advantage in material economy, but its thermal conductivity is relatively high, and strength is somewhat reduced, weakening both energy-saving and load-bearing performance. Point C is the lowest thermal conductivity solution with = 0.106W⋅m−1⋅K−1, exhibiting the best insulation performance but accompanied by lower compressive strength and higher cost, limiting its engineering applicability. Point D represents the highest-strength solution with = 7.61 MPa, achieving peak mechanical performance, but both thermal conductivity and cost increase significantly, showing a typical conflict among strength, energy saving, and economy.

Figure 14.

Pareto fronts of compressive strength, thermal conductivity, and cost.

Overall, these results systematically reveal the relationships and trade-off patterns among strength, thermal performance, and cost for EPS concrete. Extreme optimization of a single property often comes at the expense of other indicators, whereas compromise solutions provide a more robust pathway to achieve a comprehensive balance of structural safety, energy-saving performance, and economic rationality.

5.4. Comparative Analysis and Advantages of the Proposed Framework

To further highlight the scientific value and engineering significance of the proposed framework, Table 9 provides a comparative summary of representative recent studies on EPS concrete prediction. The comparison covers modeling methods, prediction targets, physical consistency, interpretability, multi-objective optimization capability, and engineering applicability. As shown in Table 9, the studies by Kumar et al. [19] and Hussain et al. [20] mainly adopted traditional ANN or ANFIS models, focusing on single-objective prediction of compressive strength or density. Although these data-driven models achieve reasonable accuracy, they do not account for thermal properties or economic factors. Zhang et al. [34] combined orthogonal experiments with an XGBoost model to predict compressive strength and thermal conductivity, significantly improving modeling efficiency and reducing experimental workload; however, the method remains statistical in nature, without introducing physical constraints or multi-performance coupling analysis. Dabi et al. [35] applied stochastic optimization and machine learning to optimize EPS particle size and dosage, revealing the sensitivity of mix parameters and improving model stability, but the focus remained on pa-rameter optimization, with limited interpretability and cross-dataset generalization.

Table 9.

Comparative summary of existing EPS concrete prediction models and this study.

In contrast, the MOPIA-RA model proposed in this study achieves a coordinated balance among compressive strength, thermal performance, and material cost (R2 = 0.95), and demonstrates clear advantages in both scientific rationality and engineering scalability, providing a systematic methodology for performance prediction and mix design of EPS lightweight concrete.

6. Conclusions

This study proposes a systematic mix design method that integrates physical constraints and multi-objective optimization to achieve a balanced relationship among the compressive strength, thermal conductivity, and material cost of EPS concrete. Based on a comprehensive experimental database, a physics-consistent, interpretable, and high-accuracy predictive framework (MOPIA-RA) was developed. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- By introducing physical constraints (PIA) and firefly algorithm (FA)-based hyperparameter optimization, the predictive accuracy and robustness of the surrogate model were significantly improved. The enhanced PIA-RA model achieved coefficients of determination (R2) of 0.98 and 0.95 for predicting thermal conductivity and compressive strength, respectively, representing an improvement of approximately 8–12% compared with the baseline RA model.

- (2)

- According to the SHAP-based interpretability analysis, EPS particle size was identified as the key factor simultaneously governing both compressive strength and thermal performance, contributing over 40% to the overall model output. EPS content also played a significant regulatory role, contributing approximately 15–20%. Regarding cementitious material replacement, the use of slag powder and fly ash at appropriate replacement ratios improved compressive strength by about 5–10%, while their enhancement of thermal performance was limited (<3%).

- (3)

- The established MOPIA-RA multi-objective optimization model effectively characterized the trade-offs among strength, thermal conductivity, and cost. The Pareto front analysis indicated that pursuing high strength alone often leads to higher cost and poorer thermal performance. The representative optimal mix (Point A), selected using the TOPSIS method, achieved a reasonable balance among the three performance indicators.

In summary, this study developed a physics-consistent, interpretable, and high-accuracy framework for EPS concrete performance prediction and optimization, providing a scientific foundation and quantitative engineering guidance for the design and application of green and energy-efficient building materials.

Author Contributions

S.L.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Funding acquisition. Q.J.: Visualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition. D.H.: Resources, Data curation. F.Y.: Software. Z.L.: Visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52568040. The APC was funded by the project.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- El Gamal, S.; Al-Jardani, Y.; Meddah, M.S.; Sohel, K.A.; Al-Saidy, A. Mechanical and thermal properties of lightweight concrete with recycled expanded polystyrene beads. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2024, 28, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatief, M.; Ahmed, Y.M.; Taman, M.; Elfadaly, E.; Tang, Y.; Abadel, A.A. Physico-mechanical, thermal insulation properties, and microstructure of geopolymer foam concrete containing sawdust ash and eggshell. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 90, 109374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shree, V.; Dwivedi, A.; Saxena, A.; Pathak, S.K.; Agrawal, N.; Tripathi, B.M.; Shukla, S.K.; Kumar, R.; Goel, V. A comprehensive review of harnessing the potential of phase change materials (PCMs) in energy-efficient building envelopes. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 101, 111841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Wu, Z.; She, W. Lightweight EPS cementitious composites via hot-pressing strategy: Toward mechanical, thermal, and acoustic properties. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 112, 113794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.M.; Tayeh, B.A.; Majeed, S.S.; Aisheh, Y.I.A.; Salih, M.N.A. Ultra-light foamed concrete mechanical properties and thermal insulation perspective: A comprehensive review. J. CO2 Util. 2024, 83, 102827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasittisopin, L.; Termkhajornkit, P.; Kim, Y.H. Review of concrete with expanded polystyrene (EPS): Performance and environmental aspects. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 366, 132919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mir, A.; Fayad, E.; Assaad, J.J.; El-Hassan, H. Multi-Response Optimization of Semi-Lightweight Concrete Incorporating Expanded Polystyrene Beads. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lu, D.; Gao, X. Optimization of mixture proportions by statistical experimental design using response surface method—A review. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 36, 102101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Yin, G.; Tuo, H.; Niu, Z. Parameter optimization and regression analysis for multi-index of hybrid fiber-reinforced recycled coarse aggregate concrete using orthogonal experimental design. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 267, 121013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, S.S.; Karjinni, V.V. Prediction of mechanical properties of high strength steel fiber reinforced concrete with multiple regression technique. IOP Conf. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 814, 012043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, W.; Tang, Y.; Jian, Y.; Lai, Y. Orthogonal Experimental Study on Concrete Properties of Machine-Made Tuff Sand. Materials 2022, 15, 3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.N.-T.; Le, D.-H.; Nguyen, D.-L. Reuse of clay brick and ceramic waste in concrete: A study on compressive strength and durability using the Taguchi and Box–Behnken design method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 373, 130801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.S.; Hari, R.; Madhavan, M.K. Performance assessment of blended self-compacting concrete with ferrochrome slag as fine aggregate using functional ANOVA. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 89, 109390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P.-P. Optimized strength modelling of foamed concrete using principal component analysis featurized regressors. Structures 2023, 48, 1730–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H. Pavement crack instance segmentation using YOLOv7-WMF with connected feature fusion. Autom. Constr. 2024, 160, 105123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, W. Adaptive feature expansion and fusion model for precast component segmentation. Autom. Constr. 2024, 164, 105456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Ye, G.; Yuen, K.-V.; Yu, W.; Jin, Q. A graph attention reasoning model for prefabricated component detection. Comput. Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2025, 40, 1606–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyelowe, K.C.; Ibe, A.S.; Ezeokonkwo, F.C.; Brito, N.A.E.; Velasco, N.; Buñay, J.; Muhodir, S.H.; Imran, H.; Hanandeh, S. Estimating the compressive strength of lightweight foamed concrete using different machine-learning-based symbolic regression techniques. Front. Built Environ. 2024, 10, 1446597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, P.; Gupta, R. Artificial Neural Network predictions for properties of concrete with expanded polystyrene (EPS). SSRG Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 12, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, F.; Ali, M.; Ahmad, R.; Khan, A. Modeling compressive strength of EPS lightweight concrete using regression, neural network and ANFIS. Sustainability 2022, 15, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, S.; El-Sayed, M.; Abdel-Latif, T. Harnessing expanded polystyrene waste for sustainable self-compacting concrete: A hybrid ML technique for predicting strength and durability. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Xu, P.; Zaman, A.; Alomayri, T.; Houda, M.; Alaskar, A.; Javed, M.F. Compressive strength prediction of concrete blended with carbon nanotubes using gene expression programming and random forest: Hyper-tuning and optimization. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 7198–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, D.; Cao, K. Prediction of concrete compressive strength using support vector machine regression and non-destructive testing. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akber, M.Z.; Anwar, G.A.; Chan, W.-K.; Lee, H.-H. TPE-xgboost for explainable predictions of concrete compressive strength considering compositions, and mechanical and microstructure properties of testing samples. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 457, 139398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ren, W.; Lei, J.; Sun, L.; Mi, Y.; Chen, Y. Predicting the compressive strength of high-performance concrete via the DR-CatBoost model. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Wang, P.; Guo, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Tan, J. Intelligent mix design of steel fiber reinforced concrete using a particle swarm algorithm based on a multi-objective optimization model. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xu, X.; Ding, X.; Chen, T.; Deng, R.; Li, J.; Jiang, J. Multi objective optimization and evaluation approach of prefabricated component combination solutions using NSGA-II and simulated annealing optimized projection pursuit method. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Shui, Z.; Xu, Z.; Gao, X.; Zhang, S. Multi-objective optimization of concrete mix design based on machine learning. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wang, L.; Feng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Qin, Y.; Xia, L. Optimization of high-performance concrete mix ratio design using machine learning. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 122, 106047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Li, Y.; Shen, J.; Jin, K.; Shi, J. Multi-objective optimization design of recycled aggregate concrete mixture proportions based on machine learning and NSGA-II algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2024, 192, 103631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, I.M.; Alves, É.C.; Calenzani, A.F.G. Multiobjective optimization of steel and concrete composite slabs via MOPSO algorithm. Structures 2025, 80, 109722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. Intelligent optimisation of ultra-high-performance concrete mixture design based on particle swarm optimization. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2023, 24, 2130919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, X.; He, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, Q. Prediction of frost resistance and multiobjective optimisation of low-carbon concrete on the basis of machine learning. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 109525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X. Mix design and performance prediction of EPS lightweight structural concrete based on orthogonal experimentation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabi, G.M.; Kozhakhmetov, H.; Akmetov, M.; Nauryzbayev, A. Stochastic optimization of expanded polystyrene size and proportion in concrete using machine learning. Mech. Technol. Sci. J. 2025, 3, 286–295. [Google Scholar]

- JG/T 266-2011; Application of Foamed Concrete. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011. (In Chinese)

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Physical and Mechanical Properties of Concrete. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

- GB/T 10294-2008; Test Method for Steady-State Thermal Resistance and Related Properties of Thermal Insulation Materials. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2008. (In Chinese)

- Beyer, H. Tukey, John W.: Exploratory Data Analysis. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company Reading, Mass.—Menlo Park, Cal., London, Amsterdam, Don Mills, Ontario, Sydney 1977, XVI, 688 S. (n.d.). Biom. J. 1981, 23, 413–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. Notes on regression and inheritance in the case of two parents. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1895, 58, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.-S. Firefly algorithms for multimodal optimization, in: Stochastic Algorithms: Foundations and Applications. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; Volume 5792, pp. 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvålseth, T.O. Cautionary Note about R2. Am. Stat. 1985, 39, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Draxler, R. Root means square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE)–Arguments against avoiding RMSE in the literature. Geosci. Model Dev. 2014, 7, 1247–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, W.G. Some comments on the evaluation of model performance. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1982, 63, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohavi, R. A study of cross-validation and bootstrap for accuracy estimation and model selection. In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–25 August 1995; pp. 1137–1143. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Lee, S.-I. Explainable AI for trees: From local explanations to global understanding. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K. Multi-Objective Optimization Using Evolutionary Algorithms; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen, K. Nonlinear multiobjective optimization. In International Series in Operations Research & Management Science; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attribute Decision Making: Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).