Abstract

Portuguese society has evolved and transformed, and with it, social models: family structures have changed, with smaller households replacing the traditional nuclear family; labor models have shifted, with a significant increase in telecommuting and a surge of digital nomadism; and consumption patterns have altered, with some domestic activities being transferred from the home to the city. In light of these transformations, this article proposes a critical examination of housing models developed in Lisbon over recent decades, comparing them with dwellings built since the mid-20th century. Through selected case studies, it questions the adequacy of contemporary housing programs in addressing present-day social structures and living patterns. Methodologically, the paper firstly proposes an analysis of Portuguese social models and their transformation through census data and social sciences studies, followed by a critical review of contemporary urban housing models through spatial analysis of selected urban dwellings of the last 70 years, through the redrawing and visual comparison of the plans. The study adopts a spatial analysis of representative collective dwellings built in Lisbon since the 1950s, chosen for their prevalence, sectoral diversity, data availability, and the city’s central role in Portuguese housing development and research. The research concludes that there has been a perpetuation of anachronistic dwelling models in Lisbon, limiting adaptability to diverse living modes, and suggests a new approach to dwelling design, promoting undetermined and ambiguous spatial configurations that allow for greater adaptability to an evolving society, changing practices, and living arrangements.

1. Introduction

The spatial and functional definition of housing models and typologies is determined by social patterns and cultural characteristics. Social models are closely linked to housing models, dwelling layout and space use [1,2,3,4,5], and spatial form (morphology and configuration) perceived as a response to socio-cultural traits. Nonetheless, domestic practices and behavior are also impacted by the built environment and influenced by the spatial–functional characteristics of dwellings. When faced with the need to reconstruct the British Commons Chamber and decide on its formal definition, Churchill argued that “we shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us” [6], a statement used to demonstrate that spatial morphology, topology, and configuration is both cause and consequence of socio-cultural traits and practices, underscoring an interconnectedness and the perception of a relational system [7] between the characteristics of space and social behavior and practices. Being a relevant topic across different knowledge fields (sociology, anthropology, environmental psychology, architecture), the impact of spatial morphology on behavior has been discussed in several studies through the cause-and-effect relationship between housing typologies and household practices (and housing satisfaction), providing evidence on how housing design and spatial morphology influence household behaviors, practices, and attitudes [8,9,10,11,12]. The latter, however, are not only influenced and determined by spatial form, but also by meaning and socio-cultural constructs of functional–spatial properties. ‘Domestic space’ relates setting, use, and meaning [13], and recognizing this triadic relation, Peponis and Wineman [14] have argued that spatial configuration and space ‘labels’ (‘living room’, ‘dining room’, and others) embody and suggest behaviors, practices, and use patterns and, as a consequence, entail cultural meaning. Recently, Peponis [15] used the expression ‘situational codes’ for the same purpose and introduced the concept of ‘spatial culture’. This concept intends to represent how society or community members occupy space and define how people perceive it and arrange behaviors and activities therein accordingly. As consequence, Peponis argues that architects and their designs can influence patterns of use, defending that behavior is conditioned and constrained by spatial design.

Housing Studies in Portugal

Several researchers and scholars have delved into the study of housing, through different lenses and approaches. Nonetheless, the examination of socio-cultural factors and their relationship with housing form, needs or uses remains greatly underdeveloped. On the subject, Lawrence [16] identifies two main foci of previous research which the author argues have somewhat been independent and not interwoven: housing sociology and morphological studies, and studies of people and their surroundings. The presented study aims to bridge this gap, by addressing these categories in a more holistic view and examining housing issues, while drawing from previous scholarship on housing studies. This scholarship is categorized and presented in Table 1, in three essential areas of research—spatial properties, social context, spatial perception, and space use.

Table 1.

Overview of relevant housing studies.

The examination of spatial properties is essential in research that entails the assessment of dwellings’ spatial and functional adequacy. Although the works by Portas [17] and, more recently, Pedro [18] propose an understanding of household activities (in Portuguese society) with a correlation with domestic spaces and dimensional properties to ensure adequate functioning, allowing for an identification of generic household practices, they lack an understanding of the changing nature of families and households (social context and transformation) and people–environment relations that determine space use idiosyncrasies. On the subject of households’ transformation and social change, recent studies have examined the impact of social and demographic factors in housing ideals and characteristics, focusing on the Portuguese reality through the study of Lisbon’s population [19,20,21,23]. In spite of this corpus of knowledge, most research proposes a sociological approach and scope, not encompassing dwelling layout, spatial morphology, or spatial configuration analysis. Addressing people–environment relations in the Portuguese context, the assessment of living patterns and space use, needs, and aspirations and recognizing that an understanding of household and individual needs is paramount for the definition of housing policies and housing design, Valente Pereira and Gago [22], and more recently Moreira [19], have conducted household surveys to ascertain housing quality, space use, and perceptions (through user satisfaction). These studies proposed post-occupancy evaluation (POE) of built and lived-in units in the city of Lisbon and entailed an examination of spatial characteristics through user feedback and direct observation, allowing for an understanding of how spatial characteristics impact space use and modes of living or behavior.

Taking this background and context into consideration, this article proposes a critical review of Portuguese urban dwellings (collective housing) by analyzing one-bedroom, two-bedroom, and three-bedroom apartments built in Lisbon since the 1950s and throughout the following decades until present times. The critical review is founded on an examination of the evolution of Portuguese society, transformations in family structures, labor patterns, and consumption models, aspects which are integral to the definition of a society and its practices. Drawing from Churchill’s view, the paper proposes to understand the extent to which the residential buildings we have shaped have themselves the ability to shape (restrict or enable) living modes and space use. Hence, the aim of the paper is to (i) ascertain whether Portuguese urban dwellings have evolved along with the Portuguese society or remained stagnant, (ii) assess the adequacy of commonly built typologies in Portugal to socio-cultural practices, and (iii) shed light into how future housing can be developed bearing in mind 21st century households’ needs, demands, and modes of living. The importance of this work lies in these goals, which envision the creation of more adequate and responsive housing.

Addressing these goals, the following research questions are formulated: (i) are Portuguese dwellings in accordance with Portuguese society’s models and practices?; and (ii) which design principles should future housing be grounded in to achieve greater adequacy and user satisfaction? Underlying these questions is the hypothesis that commonly (and continuously) built housing models and typologies have perpetuated mid-20th century models, and are thus not consistent with Portuguese society’s contemporary and future practices.

The results show that even though Portuguese society and its models and patterns have transformed immensely, Portuguese urban housing models have not evolved in the last 70 years, depicting the same spatial–functional configuration. The paper concludes by proposing a discussion of emergent design principles and solutions that have successfully been being developed in other European countries, suggesting potential pathways for new housing models and responses to Portuguese contemporary urban living patterns.

2. Materials and Methods

To conduct the critical review of Portuguese urban dwellings, the study proposes a methodology based on spatial analysis of specific dwelling-types built in the city of Lisbon over 7 decades, since the 1950s. The collective housing building was introduced in Portugal in the late 1940s in a more generalized and almost hegemonic way in urban contexts, which accounts for our election of the decade of the 1950s as the starting point for the examination. The focus on Lisbon as a case study derives not only from the overview of housing studies in Portugal (the election of Lisbon allows for an alignment with previous research and greater relevance of past findings), but mainly from the fact that Lisbon is Portugal’s capital, the most populated and dense urban setting, and where collective housing is more predominant and expressive.

The criteria for the selection of the dwelling units was based on the following rationale: the study privileged the election of different collective housing dwelling typologies—one-bedroom, two-bedroom and three-bedroom units—which correspond to the most commonly built typologies in the city of Lisbon [20], therefore the most representative of Lisbon’s housing stock. The collection also sought to select case studies that represented different housing sectors, from public housing to private initiatives and from social housing to the luxury market, also encompassing middle-class housing. The availability of data, i.e., plans and drawings, was also a criterion.

Methodologically, the spatial analysis was based on an initial redrawing of the dwellings’ plans, to present the plans in the same graphic code and scale, and the identification of ‘spatial labels’ [13], either by information in the original plans, furniture placement, or written documents. Visual comparison of the plans, as well as spatial layout diagrams, were the chosen methods of analysis. The diagrams depict dwellings’ spaces (rooms and transition spaces) and allow for a more immediate representation of the dwellings’ spatial structure and morphology.

Prior to the spatial analysis, a description of the evolution of the Portuguese society, also focusing on the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, is presented, with the aim of understanding not only social patterns and examining their adequacy to housing models, but also to examine contemporary trends and assess contemporary and future housing through this lens. For this examination, statistical data collected and made available by the National Statistics Institute (INE) regarding households, labor practices, and time use were sourced. Studies on labor practices and time use were also relevant for this examination, complementing INE’s data, which are scarcer for both aspects.

3. Portuguese Society: Evolution and Transformation

Considering that the characteristics of a society constitute determining factors for the design of housing models and that a critical examination of current housing adequacy needs to be founded on an understanding of that society, it is crucial to understand contemporary social patterns, practices, and characteristics. To properly characterize Portuguese society and understand its evolution and transformations in the last seven decades, this article analyses several facets that influence the definition of social models: household dimension and composition, labor practices, technological advancements, and consumption patterns. All these aspects shape society and its traits, and directly impact household living modes and domestic functional/spatial demands. In this section, the evolution of the Portuguese society is presented through the analysis of the abovementioned facets. Statistical data from the National Statistics Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estatística—INE), and social sciences studies are the basis for the presented data and information. National data and Lisbon Metropolitan Area (AML) data are presented, using the statistical regional classification and subdivision NUTS II. AML data are presented to better convey an urban reality, where collective housing is predominant.

3.1. Household Models

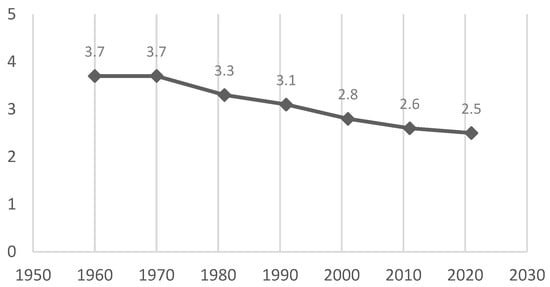

To understand the evolution of family models and characterize contemporary households, it is important to observe certain indicators. Particularly revealing of the population’s reality are the average family size, the predominant types of family composition, and the trends in their evolution, as well as the attitudes of households and individuals regarding gender roles within the family. Focusing firstly on the average family size in Portugal and its evolution over the decades, data from the National Statistics Institute (INE) show a consistent reduction in the number of people per household, a trend that has persisted since the 1970s (Figure 1). In 2021, according to the latest population census, the average family size was 2.5 people per household, continuing the downward trend of this indicator and suggesting further decline. In the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (AML), the average family size is even smaller, with a similar trend of decrease since the early 21st century (no statistical data are available for analysis prior to this date; Table 2).

Figure 1.

Evolution of family average dimension, Portugal (data source: INE).

Table 2.

Evolution of family average dimension, 2001–2021 (NUTS II; data source: INE).

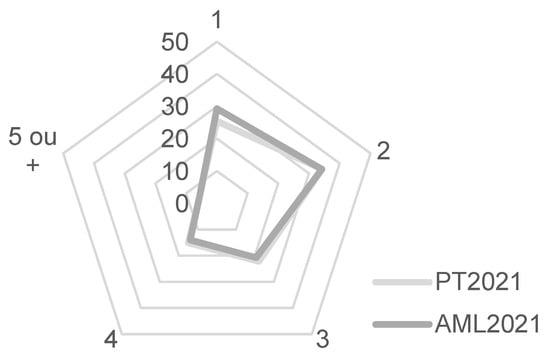

Although the average family size is above two people per household, data regarding household size show that two-person households are the most common arrangement, both nationwide and within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (AML), with an increase in their representativity over the last three census surveys (2001–2011–2021). The same data (Table 3 and Figure 2) show that larger families are less represented in Portuguese society, and that in recent years (2011–2021), single-person households have become the second most common type, demonstrating a tendency for a reduction in the number of people in private households.

Table 3.

Evolution of private household dimension, 2001–2021 (NUTS II with the most representative household dimension highlighted in grey; data source: INE).

Figure 2.

Private household dimension, Portugal and AML, 2021 (data source: INE).

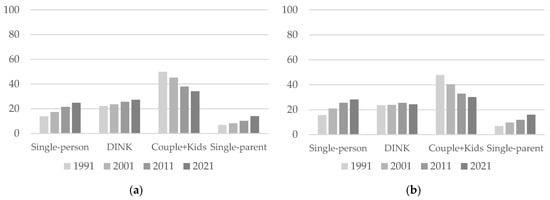

Looking at the composition of the household (single-person households, DINK—dual income no kids, couples with children, or single-parent families), it is apparent that the couple-with-children household composition remains predominant in Portuguese society, although its significance is declining. In opposition, a significant increase in the representation of less traditional family structures—particularly single-person households and single-parent families—is noticeable. DINK arrangement also shows a growing trend. The AML reflects this national trend, with a significant decline in the importance of the composition of couples with children. Although still predominant, their representation is almost negligible (a difference of less than 2% compared to single-person households), and again, there is a notable rise in single-person and single-parent households (Table 4; Figure 3).

Table 4.

Household composition, 2001–2021 (NUTS II; data source: INE).

Figure 3.

(a) Evolution of household composition, 1991–2021, Portugal; (b) evolution of household composition, 1991–2021, AML (NUTS II; data source: INE).

Analyzing the data, it can be concluded that in the denser urban context of the AML, a predominance of smaller households is identified, with single-person and single-parent households showing greater prevalence than in the rest of the country.

The presented data and analysis allow for the depiction of a portrait of Portuguese society, which is characterized by private households of reduced dimension, mostly consisting of one or two people (59.6% nationally, 63.5% in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area), with a growing prevalence of family structures other than the traditional couple-with-children model, whose relevance has been declining in contrast to the positive variation in single-person and single-parent households. The analysis shows that the Portuguese family has undergone significant changes, especially since the last decades of the 20th century, a period marked by shifts in marital models and the modernization of family life, marked by the following characteristics: the rise in cohabitation (de facto unions vs. legal unions), an increase in divorce, and consequently the emergence of single-parent families, as well as a decline in birth rates [25].

This modernization also entails the individualization of family life [26], not only in relation to the rise in childless couples (DINK), but also to the increase in single-person households. On the other hand, the trend of an aging population (greater life expectancy and lower birth rates) also helps explain the growth of single-person households. In addition to the processes of informalization and individualization in families, it is also important to highlight the transformations in the role of women in society (and in the household) in an increasingly equitable society, where gender differences are being blurred and the meanings of gender roles are being rethought, thus democratizing domestic spaces and household activities.

3.2. Labor Models and Practices

Labor models have been constantly evolving, with the most significant transformations usually associated with technological advancements. With the widespread use of personal computers and universal access to information technologies, it has become possible for many work activities to be carried out remotely, eliminating the need for the worker’s physical presence at the workplace. This trend of the emergence and growth of remote work was accentuated during the pandemic and has continued in the post-COVID-19 period.

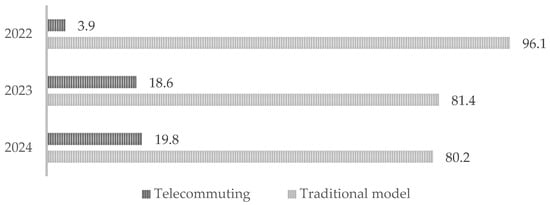

Data from the INE’s Employment Survey. Telecommuting [27] reveal that in 2023, 18.6% of the employed population in Portugal telecommuted, with approximately 26% doing so full-time (all work performed at home) and about 35% on a regular basis (several days a week, every week or on rotating weeks, or other work schedule systems). The average number of days in this labor model was 3 days, with an average of 35 h per week (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Evolution of the telecommuting trend, 2022–2024, Portugal (data source: INE).

Although data for 2024 is still limited to the third quarter, it can be stated that the remote work-from-home model has continued to grow, with the average of 3 days of work from home remaining consistent. The same survey clarifies that, among the population who worked from home in 2023, only 4.5% (3.5% in 2024) did not engage in telecommuting, defined as working from home using information and communication technologies (ICT) [27].

Another relevant aspect of remote work is the emergence of a new class of workers—digital nomads—whose labor model entails the use of ICT and is not location-bound, i.e., not tied to a physical and permanent workplace or workspace. According to the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in the first year of the creation of the remote worker visa (launched in October 2022), 2600 visas were issued [28]. For these individuals, the dwelling will tend to encompass labor functions and activities, taking on the dichotomic significance of both living and working space.

In addition to these new labor patterns and models, it is also important to address another transformation, not related to the workplace location but to the weekly work schedule. The recently introduced four-day workweek will likely bring changes to living patterns due to the increased time spent at home, although it is still not possible to assess the full consequences of adopting this model, which remains quite marginal in our society.

3.3. Consumption Models

Having already examined the transformations in family structure and labor models, two aspects of great relevance to the use of domestic space and the definition of living arrangements, it is also important to understand the transformation of consumption patterns, which have altered substantially since the 20th century. The latter represents a shift in how households interact with the domestic setting and which activities are performed therein, relating to the fourth dimension of housing—time [29].

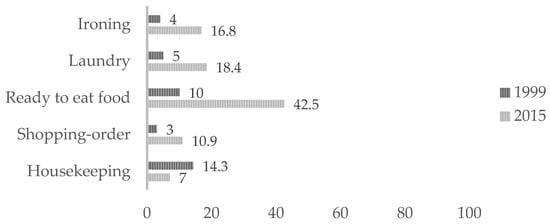

One of the first noteworthy changes stems from the already mentioned transformation of women’s roles in society and the family. From their mid-20th century role as housewife, devoted to family life and household work, the Portuguese woman’s role transformed and broke ties with the previous condition. In a current increasingly equitable society, gender differences or attributes cease to determine one’s role in the household, and men and women become equally responsible for domestic and family life [30], as well as for earning income. Partly a consequence of this social order, contemporary living modes engage in the transfer of activities and functions once carried out at home (primarily by women) to external providers or, in some cases, to individuals or companies specializing in domestic work. Particularly relevant are the changes in consumption patterns that have removed some functions previously performed at home, such as meal preparation and laundry care, outsourcing them to external services or providers. In the 21st century and mostly in urban contexts, other than the professional ironing and laundry services already available and sought in the 1990s, self-service laundries and drying facilities have proliferated in cities. These services address the lack of equipment in homes, and, in some cases, the lack of physical space for said equipment or such activities (e.g., drying racks or ironing areas). Although this is an apparently growing tendency in Portuguese urban living, there is a lack of studies addressing these practices. The few time use studies (TUS) carried out in Portugal [31,32] at a national level, although outdated, demonstrate that in approximately 15 years (1999–2015), the practice of outsourcing ironing and laundry, opting for ready-to-eat meals and ordering shopping items has grown substantially (Figure 5). It could also be argued that in a densified urban territory, such as the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, these outsourcing practices would show even greater percentages.

Figure 5.

Evolution of the practice of outsourcing domestic activities to external providers or services, 1999–2015, Portugal (data source [31,32]).

The comparison between these TUS show a very significant increase in the number of households who opt for ready-to-eat food, which is indicative of relevant changes in the living modes and practices in the domestic setting, i.e., the reduction of time allocated to food preparation, impacting space use and spatial–functional demands (kitchen). Also related to market substitutes for food preparation, another consumption pattern that has arisen and strengthened is the option for ready-meal home-delivery services, which further enable families to reduce household chores. These new consumption patterns and practices regarding food preparation, which Heathcote [29] refers to as “the age of takeaways, pizza deliveries and microwaves”, represent inevitable alterations to how kitchens are perceived and used, becoming less functional and more representational [29,33].

Another noteworthy transformation is the technological development and widespread use of personal devices with access to information technologies. Televisions or stereos are no longer the focal points for family leisure activities in the domestic space. Instead, each household member owns one or more electronic devices—including computers, tablets, or smartphones—through which they connect to the world. To this regard, Heathcote [29] defends that we have introduced a fifth dimension into the dwelling, that of cyberspace, where everyone is always connected everywhere. This new reality has impacted both the relationship of household members with residential spaces and their interactions with one another, as individuals increasingly use the home in a more isolated manner.

4. Portuguese Contemporary Housing Models

A necessary foundation for the conception of new urban dwellings for a changing society is a critical examination of current and past dwelling models. In this section, a critical review of selected dwelling types built in the city of Lisbon since 1950 until present times is presented, focusing on multistorey collective housing and the typologies most commonly built—one-bedroom (T1), two-bedroom (T2), and three-bedroom (T3) units. This review will enable a comparison between recently built housing developments and housing units designed and built throughout the 20th century, to better understand if contemporary models (21st century) are relevant and align with the characteristics of the Portuguese society described earlier. The selected examples aim for a broad representation of cases—ranging from social housing to standard housing and luxury housing; from renowned architects and firms to more “anonymous” architects or public institutions—to demonstrate that the conclusions drawn apply not only to specific situations, operations, or initiatives, but are broadly relevant. Additionally, given the extensive housing stock and to ensure the analysis is as impartial as possible, three housing complexes in Lisbon were chosen as representatives of contemporary housing models: the EPUL Entrecampos development (a public initiative), the Benfica Stadium development (a private initiative targeting the standard market, with a few exceptions), and the Nova Amoreiras development (also a private initiative but promoted as a luxury housing complex), all designed and built in the first two decades of the 21st century.

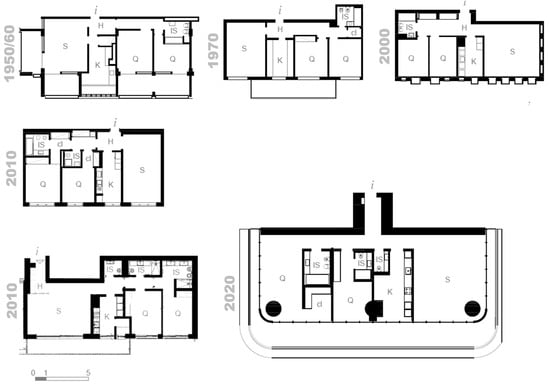

Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 depict the selected case-studies—one-bedroom (Figure 6), two-bedroom (Figure 7), and three-bedroom (Figure 8) correspondingly—and are placed in a chronologic order.

Figure 6.

T1 dwelling units—Lots 21 and 22, Av. Estados Unidos da América and Avenida de Roma intersection development, Block D (1952–1957, Filipe Figueiredo and José Segurado); Olaias Mall Complex (1970s and 1980s, Tomás Taveira); EPUL Entrecampos (2000s, Promontório); Benfica Stadium, Lot 6 (2010s, Bruno Leite); Nova Amoreiras (2010s, CHP Arquitectos). (legend: i—entrance, H—hall, IS—bathroom, Q—bedroom, K—kitchen, S—living room).

Figure 7.

T2 dwelling units—Lots 21 and 22, Av. Estados Unidos da América and Avenida de Roma intersection development, Block D (1952–1957, Filipe Figueiredo and José Segurado); Avenida Gomes Pereira 101–105 (1970s); EPUL Entrecampos (2000s, Promontório); Benfica Stadium, Lot 13 (2010s, Francisco Xavier Olazabal); Nova Amoreiras (2010s, CHP Arquitectos); Infinity Tower (década 2020, Saraiva & Associates). (legend: i—entrance, H—hall, IS—bathroom, Q—bedroom, K—kitchen, S—living room, cl—closet).

Figure 8.

Rua de Entrecampos 21 (1960s); Av. José dos Santos Pereira 6 (1970s); PER Bairro da Liberdade (1990s); EPUL Entrecampos (2000s, Promontório); Benfica Stadium, Lot 1 (2010s, Arquireal); Nova Amoreiras (2010s, CHP Arquitectos). (legend: i—entrance, H—hall, IS—bathroom, Q—bedroom, K—kitchen, S—living room, cl—closet).

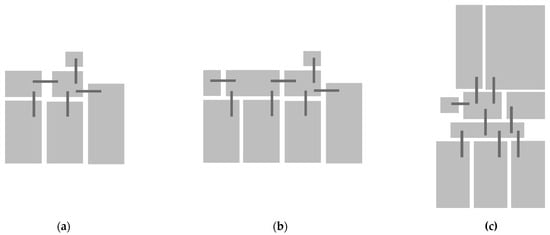

An observation of these plans reveals that since the 1950s, the same housing models have persisted in the Portuguese context, and that no significant variations in the spatial configuration and structure are noticeable between housing units from the 1950s and contemporary ones. In fact, it is observed that the same designs are repeated over the decades, despite Portuguese society having evolved and undergone notable and significant transformations. The simplified spatial diagrams of the selected case studies (Figure 9) confirm this visual observation, demonstrating that for seven decades, Lisbon households have inhabited and been offered the same layout.

Figure 9.

(a) T1 unit spatial layout diagram; (b) T2 unit spatial layout diagram; (c) T3 unit spatial layout diagram.

This examination allows for the conclusion that very little variation exists between the different housing units from the different decades, and these are generally limited to the number of bathrooms and the gross floor area (or compartment area). In the latter category (total or partial area), developments promoted as belonging to a luxury sector (e.g., the T2 unit in the Nova Amoreiras development—Figure 7—and the T3 unit in the Infinity Tower—Figure 8) stand out from the rest due to their larger size, though they retain the same basic structure as other units from the same typologies over the decades. The analysis further confirms that in the case of the T3 typology, the differences among the selected case-studies are practically non-existent. The case-studies’ floor plans, if overlapped, would produce a clear and legible drawing.

5. Discussion

The observation of the floor plans in the selected case-studies which represent the three most common typologies in Lisbon demonstrates the rigidity and immutability of the solutions and models of Lisbon’s housing stock. The dwellings’ structure and rooms configurations (Figure 9) allow for the inference of spatial labels, related to functions and uses, demonstrating the absence of flexibility to accommodate new or alternative uses or practices that arise from changes in family structures, labor models, and consumption patterns, as those that have been witnessed in the Portuguese society, as examined earlier. Considering that the presented case-studies are representative of contemporary housing models, it is crucial to question their relevance in today’s context and assess their adequacy to current social models and practices, characterized by smaller households, greater diversity in household composition and living arrangements, telecommuting, and an increasing importance of virtual sociability, leisure, and consumption. It becomes, therefore, essential to question these persisting structures and evaluate innovative design principles that are able to address contemporary social practices, needs, and living modes. Fuertes and Monteys [34] once posed a very significant and still relevant question: “How many [architects] will build the House the 21st century really needs? And more importantly, for whom?” The presented research demonstrates that, in the Portuguese context, both architects and developers (public or private) still lack awareness and knowledge of contemporary society’s needs and practices and, maybe more relevant, a lack of comprehension of contemporary living arrangements, living patterns, and household characteristics. The “man in the tram” that Edoardo Persico referred to as the typical individual and typical household of the early decades of the 20th century and which served as basis for the development and conception of modernist housing models has transformed greatly. Why then should the dwelling remain the same? The reproduction of modernist schemes is, however, not particular to Lisbon’s housing stock, but also a reality in other European contexts, as Porotto and Ledent have realized in their study of the city of Brussels [35], having also concluded that contemporary dwellings lack typological innovation and new design approaches.

Considering that contemporary design principles and housing models should reflect and be impacted by social and domestic practices it is vital to build onto Fuertes and Montey’s query, and ask the following question: what house does the 21st century need? Several authors [35,36,37] have, for long, advocated that flexibility and flexible solutions promote greater adequacy and adaptability, for a broader range of inhabitants and households, and through larger time spans. It also provides a direct response to contemporary domestic demands, when the dwelling is not only a residence, but a setting for work, leisure, and sociability, a juxtaposition that entails flexibility of use. Recent European housing developments have developed this design principle [38], either via the absence of functional pre-determination of the residential compartments (Bloque 6 × 6 in Girona, Spain, by Ramon Bosch and Bet Capdeferro, 2022 [39]; social housing in Cornellà de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain, Marta Peris and Jose Toral, 2022 [40]) or through typological variety, as a response to the diversity of family compositions, relationships, and lifestyles (Kalkbreite Cooperative Housing, Zurich, Switzerland, Müller Sigrist, 2014 [41]). In the latter, the way of inhabiting and using the space is not pre-defined or established by the architects or developers, allowing residents to appropriate the spaces in diverse ways. The lack of hierarchy and functional determination also allows for greater adaptability over time to the family’s evolving needs, as well as to the needs and lifestyles of different households, without requiring changes to the apartment’s structure. Solutions of passive flexibility (de-hierarchized and ambiguous layouts with multiple use possibilities) and active flexibility (physical alteration of the circulation system, opening or closing sliding elements, transforming the relationship between compartments and the functional matrix of the dwelling) [36] can be explored. In the former, flexibility is linked to the possibility to choose and change dwelling units according to household needs and add or use additional communal spaces to meet temporary or urgent demands. These qualities stem from innovative thinking in defining the housing program, which takes into account the diversity of social models and the need for housing to be appropriate and adaptable to an increasingly broad range of lifestyles, which are themselves variable and changing. Although still absent from the most commonly built Portuguese dwelling models, passible and active flexibility solutions have begun to be explored in recent submissions to design competitions promoted by the national Housing and Urban Rehabilitation Institute (IHRU), having demonstrated a willingness amongst some architects to break the cycle and propose new and innovative models, as is the case of FORA Architects’ proposal for municipal housing in Bairro do Armador, in Lisbon and Ana Luísa Afonso Soares’ proposal for the housing complex on Rua Conde Nova Goa, also in Lisbon, both awarded second-place in the correspondent competitions.

The persistence of rigid and pre-determined domestic spatial structures in Portugal, replicating modern models, is not only a consequence of lack of discussion of the housing program and spatial configuration in conjunction with a scientific gap in interconnecting and relating social practices and characteristics with housing conception, but also, and very significantly, a result of very strict and obsolete legislation [19,37]. The RGEU (Regulamento Geral das Edificações Urbanas—Urban Buildings General Regulation), recently revoked but whose latest overall redaction dated from 1975, dictated very strict and conservative norms regarding spatial configuration and morphology, not allowing for greater innovation and invention. And although some innovative proposals have been developed in neighboring Spain, legislative constraints have also been appointed as an obstacle to rethinking spatial structure due to a failure to understand social diversity and social practices [42]. In 2026, a new legal instrument is scheduled to take RGEU’s place. Studies such as the one presented in this paper, proposing greater integration and coordination between architecture and social sciences, housing models, and socio-cultural practices, can bring relevant scholarship and significant impact not only for the redaction of legal norms and regulations, but also for the implementation of new housing policies that reject rigid and pre-determined structures which do not favor adaptability and adequacy, but incorporate principles of flexibility and adequacy to diverse modes of living (either household practices, such as telecommuting or outsourcing domestic activities, or household composition—diverse compositions and living arrangements).

6. Conclusions

The paper aimed to conduct a critical review of housing models promoted and built in recent decades in comparison with dwellings of the last 70 years built in the city of Lisbon, questioning the adequacy of current housing programs to present social models and living patterns through an examination of selected case-studies. The critical analysis of their adequacy to Portuguese society’s practices (family structures, labor patterns, and consumption models) was based on an examination of the transformations occurred in Portuguese society. Bearing in mind these social transformations—private households’ dimension reduction and composition transformation; informality and modernization of the family unit and gender role evolution; labor practices transformation and technological advancements; and changes in consumption patterns—it becomes apparent that current housing models which replicate mid-20th century layouts (designed to address the needs and uses of family-types and stereotypes that no longer exist) are inadequate to cater to contemporary living modes; nor are they easily adaptable to diverse lifestyles, needs and demands—present or forthcoming. The research shows that rigid and deterministic housing models still prevail in Portuguese new builds, in collective housing buildings and developments, and that the 21st century Portuguese family still inhabits the same dwelling as the 1950s family, although society has changed and evolved greatly, as have individual and household needs, demands and living modes, living arrangements, and social practices. The research also shows that little innovation and experimentation has been promoted and developed over these seven decades with regard to the housing program and dwelling layout. Nonetheless, recent submissions to design competitions show a shift in the identified trend. Although these consist of a new way of thinking and conceiving the housing program and model by breaking with anachronistic and deterministic layouts, the fact is that there is still a lack of discussion about current housing models in Portugal and their obsolescence, further heightened by a strict legislative context. This paper’s contributions are intended to fill this gap and provide a basis for a new discussion of housing models and housing program, igniting the issue and proposing a critical examination of Lisbon’s present housing stock and future builds. To this end, the study also suggests a path for dwelling morphology and configuration where ‘spatial labels’ and ‘situational codes’ are not inferable, but undetermined and ambiguous instead, fostering adaptability and greater adequacy or appropriation to diverse modes of living and living arrangements. Despite these contributions, the paper’s limitations regard the lack of information and greater knowledge of spatial perception and space use which could be integrated in further research based on user feedback through POE studies and user/household inquiries to ascertain effective household practices and space use.

Author Contributions

Both authors have been equally engaged in the development of the present research and the preparation and conclusion of this article, collaborating in all stages and sections of this document. Formal analysis: A.M.; funding acquisition: H.F.; investigation: A.M. and H.F.; methodology: A.M. and H.F.; visualization: A.M. and H.F.; writing—original draft: A.M. and H.F.; writing—review and editing: A.M. and H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is financed by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the Strategic Project with the reference: UID/04008: Centro de Investigação em Arquitetura, Urbanismo e Design.

Data Availability Statement

The statistical data presented in this study are available in INE Portal and INE’s publications at https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_main (accessed on 10 July 2024). These data were derived from resources available in the public domain. No new data were created in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AML | Lisbon Metropolitan Area |

| IHRU | Portuguese Housing and Urban Rehabilitation Institute |

| INE | Portuguese National Statistics Institute |

| RGEU | Regulamento Geral das Edificações Urbanas (Urban Buildings General Regulation) |

References

- Leger, J.M. Modos de Habitar e Arquitectura. Cid. –Comunidades E Territ. 2001, 3, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. House Form and Culture; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, I.; Moura, D.; Pereira, S.M. Novas Necessidades de Habitação: Alterações Sócio-Demográficas e Oferta Habitacional. Relatório Final; ISCTE-CET: Lisboa, Portugal, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, J. Decoding Homes and Houses; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Muntañola, J. Compreender la Arquitectura; Editorial Teide: Barcelona, Spain, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- UK Parliament. Available online: https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/building/palace/architecture/palacestructure/churchill/ (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Edgu, E.; Unlu, A. ‘Relation of domestic space preferences with Space Syntax parameters. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Space Syntax Symposium, London, UK, 17–19 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Thornock, C.; Nelson, L.; Porter, C.; Evans-Stout, C. There’s no place like home: The associations between residential attributes and family functioning. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 64, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, S. The impact of the have-want discrepancy on residential satisfaction. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungur, Ç.; Çagdas, G. Effects of Housing morphology on user satisfaction. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Space Syntax Symposium, London, UK, 17–19 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ruivo, C.; Varoudis, T. Organising family life: An analysis of the spatial organization of people and activities in the household. In Proceedings of the 12th International Space Syntax Symposium, Beijing, China, 8–16 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nowzari, Z.; Armitage, R.; Maghsoodi Tilaki, M.J. How does the residential complex regulate resident’s behaviour? An empirical study to identify influential components of human territoriality on social interaction. Sustainability 2003, 15, 11276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieraad, I. Anthropology at Home. In At Home: An Anthropology of Domestic Space; Cieraad, I., Ed.; Syracuse University Press: Syracuse, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Peponis, J.; Wineman, J. Spatial Structure of Environment and Behaviour. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology; Bechtel, R., Churchman, A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 271–291. [Google Scholar]

- Peponis, J. Architecture and Spatial Culture; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, R. House Form and Culture: What have we learnt in thrity years? In Culture-Meaning-Architecture; Moore, K.D., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Portas, N. Funções e Exigências de Áreas da Habitação; LNEC: Lisboa, Portugal, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Pedro, J.B. Programa Habitacional. Espaços e Compartimentos. (Reprodução integral da 1ª edição de 1999); LNEC: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, A. Habitar em Lisboa no Século XXI. Adequação Funcional da Habitação Colectiva Urbana Contemporânea aos Novos Modos de Habitar e aos Novos Modelos Sociais. PhD Thesis, Faculdade de Arquitetura da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal, 5 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, A.; Farias, H. Analyzing Housing and Household Evolution and Actuality in Lisbon, 2000–2020. Curr. Urban Stud. 2022, 10, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garha, N.S.; Azevedo, A.B. ‘Demography and Housing: Challenges and opportunities for Lisbon’s housing prospects from 2022 to 2051’. Cities 2025, 159, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente-Pereira, L.; Gago, M.A. O Uso do Espaço na Habitação; LNEC: Lisboa, Portugal, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, S.M. Housing Ideals in Metropolitan Portugal: The case of Lisbon. In Proceedings of the The Housing Markets of Southern Europe in Face of the Crisis, Görlitz, Germany, 1–5 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrita, A.; Morgado, L. Tipos Emergentes de Habitação; Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil: Lisboa, Portugal, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, A.; Wall, K. (Eds.) Famílias nos Censos 2011: Diversidade e Mudança; Instituto Nacional de Estatística e Imprensa de Ciências Sociais: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aboim, S. Dinâmicas regionais de mudança nas famílias (2001–2011). In Famílias nos Censos 2011: Diversidade e Mudança; Delgado, A., Wall, K., Eds.; Instituto Nacional de Estatística e Imprensa de Ciências Sociais: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014; pp. 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- INE. Inquérito ao Emprego Trabalho a Partir de Casa. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_main (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Jornal Público. Available online: https://www.publico.pt/2023/11/03/p3/noticia/ano-2600-vistos-nomadas-digitais-gostam-viajar-vem-ficar-2068427 (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Heathcote, E. The Meaning of Home; Frances Lincoln: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, K.; Cunha, V.; Ramos, V. Evolução das estruturas domésticas em Portugal, 1960–2011. In Famílias nos Censos 2011: Diversidade e Mudança; Delgado, A., Wall, K., Eds.; Instituto Nacional de Estatística e Imprensa de Ciências Sociais: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014; pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- INE. Inquérito à Ocupação do Tempo. Principais Resultados; INE: Lisboa, Portugal, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Perista, H.; Cardoso, A.; Brázia, A.; Abrantes, M.; Perista, P.; Quintal, E. Os Usos do Tempo de Homens e de Mulheres em Portugal; CESIS and CITE: Lisboa, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, A.; Gameleira, R.; Canova, C.; Farias, H. The Kitchen revisited: Meanings of functional and physical metamorphosis within the western urban home. In Proceedings of the 9th International Multidisciplinary Congress PHI 2023: Creation, Transformation and Metamorphosis, Sevile, Spain, 5–7 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes, P.; Monteys, X. Casa Collage. Um Ensayo sobre la Arquitectura de la Casa; Gustavo Gilli SA: Barcelona, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Porotto, A.; Ledent, G. Crisis and Transition: Forms of Collective Housing in Brussels. Buildings 2021, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, H. A more versatile and adaptable dwelling, for a changing society. In Architectural Research Addressing Societal Challenges: Proceedings of the EAAE ARCC 10th International Conference (EAAE ARCC 2016); Costa, M.C., Roseta, F., Lages, J.P., Costa, S.C., Eds.; CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group: Lisboa, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, A. Habitação Flexível. Análise de Conceitos e Soluções. Master Thesis, Faculdade de Arquitectura, Lisboa, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, A.; Farias, H. Admirável Mundo Novo: Novos Modos e Novos Modelos De Habitar a Cidade. In Proceedings of the 5º CIHEL, Lisboa, Portugal, 2-4 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Arquitectura Viva. Available online: https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/bloque-6x6-en-gerona (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Arquitectura Viva. Available online: https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/85-viviendas-sociales-en-cornella-de-llobregat-barcelona (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Muller Sigrist Architects. Available online: https://www.muellersigrist.ch/arbeiten/bauten/wohn-und-gewerbesiedlung-kalkbreite-zuerich/ (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Avilla-Royo, R.; Jacoby, S.; Bilbao, I. The Building as a Home: Housing Cooperatives in Barcelona. Buildings 2021, 11, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).