Abstract

In this study, 3 wt.% Re/Inconel 718 composite was fabricated by laser powder bed fusion (LPBF), and the effects of aging treatments on the microstructure and properties of the Re/Inconel 718 composite were systematically investigated. This study aims to elucidate the synergistic optimization of microstructure and properties in LPBF Inconel 718, achieved through Re alloying and subsequent heat treatment. Results demonstrated that the samples undergo recrystallization and precipitate numerous fine strengthening phases after heat treatment. Concurrently, heat treatment promotes the diffusion of Re within the material, leading to a significant reduction in its concentration in locally enriched regions. The addition of Re improves the mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of the Inconel 718 alloy through synergistic strengthening mechanisms, including dispersion strengthening, solid solution strengthening, and dislocation strengthening. When the two-stage aging is 720 °C × 8 h (FC × 2 h) + 620 °C × 8 h (AC), the optimum mechanical properties are observed. The dissolution of Laves phases, simultaneous precipitation of both γ″ and γ′ phases, and homogenization of microstructure are responsible for the enhancement of the material’s mechanical properties. However, the extensive precipitation of strengthening phases also promotes the formation of numerous microscopic corrosion cells, which accelerates the corrosion rate and leads to a marked reduction in corrosion resistance of the material. This study provides new insights into the laser additive manufacturing of high-performance nickel-based composites.

1. Introduction

Due to its outstanding hot stability and exceptional susceptibility to stress corrosion cracking, Inconel 718 alloy has become an indispensable structural material for critical applications in aerospace and marine engineering [1,2,3,4,5]. During LPBF processing, extremely high cooling rates induce significant temperature gradients, leading to the generation of high residual stresses [6,7,8,9]. Simultaneously, the segregation of highly concentrated hard-melting elements such as niobium and molybdenum further leads to material microstructural inhomogeneity and defect formation, severely compromising the alloy’s mechanical properties. Employing appropriate heat treatments can effectively improve the precipitation behavior of strengthening phases in Inconel 718, thereby optimizing the microstructure and enhancing mechanical properties. Briones-Montemayor et al. conducted homogenization treatments at 1170 °C and 1210 °C, followed by a solution-aging process, ultimately obtaining an Inconel 718 alloy with a uniform microstructure and enhanced mechanical properties [10]. To investigate how solution treatment temperature influences the mechanical properties of the alloys, Li et al. conducted a standardized double aging treatment, using solution temperatures of 940 °C, 980 °C, 1020 °C, and 1060 °C as the sole variable [11]. The results indicated that the mean hardness of the LPBF-IN718 alloy increases to a maximum and then decreases with increasing solution treatment temperature. A peak microhardness of 502 HV0.2 was achieved at 980 °C, which represents a 17.56% increase over the as-deposited samples.

Rhenium (Re) is a rare refractory metal with an extremely elevated melt temperature, outstanding hot resistance, and high hardness, maintaining outstanding strength and stability even in high-temperature environments [12,13,14,15]. Owing to these properties, it has been widely investigated in recent years for its potential application as a reinforcing phase in metal matrix composites [16]. Zohrevand et al. investigate the strengthening mechanism of Re in the AlMo0.5NbTa0.5TiZr high-entropy alloy [17]. The results indicated that Re addition leads to the formation of a new HCP Zr-rich intermetallic compound. The enhanced performance was attributed to the formation of compounds and solid strengthening, which contributed to a 13% increase in hardness along with improved room-temperature corrosion resistance and high-temperature oxidation resistance. Majchrowicz et al. investigated the effect of Re addition on the corrosion resistance of LPBF-IN718 alloy. The results demonstrate that the addition of Re reduces the corrosion current density and consequently enhances the corrosion resistance of the alloy [18]. However, there is a scarcity of comprehensive research on the synergistic optimization of Re reinforcement and heat treatments on the microstructure and properties of the Inconel 718 superalloy fabricated by LPBF. This constraint significantly limits the innovative research and development and broader application of this material system in critical fields such as aerospace.

To address the aforementioned research gap, this study fabricated 3 wt.% Re/Inconel 718 composites via LPBF by integrating Re as a reinforcing phase into the Inconel 718 alloy matrix. This study systematically investigated the strengthening effect and mechanism of Re addition, as well as the effect of different aging treatments on the microstructure, mechanical properties, and corrosion resistance of Re/Inconel 718 composites. The findings aimed to provide novel research approaches for the preparation and performance regulation of nickel-based high-temperature alloy composites.

2. Experiment and Methodology

2.1. LPBF Fabrication

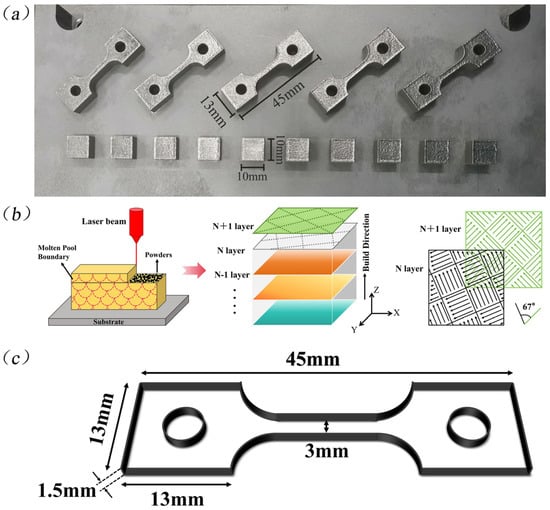

The Inconel 718 powder used in this study was supplied by Avimetal AM Tech Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China), with a particle size range of 15–53 μm. The composites of Inconel 718 containing 3 wt.% Re were produced using an EOS M290 LPBF system (EOS GmbH, Munich, Germany). Figure 1 illustrates the manufacturing workflow along with the resulting samples in their as-built state. Homogenization of the Re and Inconel 718 powder blend was achieved by mixing in a V-300 unit at 12 r/min in ambient air prior to the fabrication process. The total mixing time was 10 h, with a 30 min pause introduced after every 2 h of operation. The LPBF process is shown in Table 1. It is noteworthy that the optimal processing parameters for the Re/Inconel 718 composite material require further investigation and are yet to be established.

Figure 1.

(a) Experimental specimens fabricated by LPBF; (b) Illustration of scanning strategy; (c) Tensile specimen diagram.

Table 1.

LPBF parameters for the fabrication of the samples.

2.2. Heat Treatment

The Re/Inconel 718 composites underwent heat treatment in an SX-G04133 model electric furnace (Zhonghuan Furnace, Tianjin, China). Previous research indicates that Inconel 718 alloy exhibits excellent mechanical properties and corrosion resistance after solution treatment at 1020 °C [5,19,20]. Accordingly, this study adopts 1020 °C as the solution treatment temperature to investigate the effects of subsequent aging treatments on the materials. Detailed processing parameters, the choice of which is based on established practice, can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Heat treatment of Inconel 718 (H0) and Re/Inconel 718 (S0-S620) formed by LPBF.

2.3. Microstructural Characterization

Following etching with a solution composed of 8 mL H2O, 8 mL HCl, 2 mL HNO3, and 1 mL H2O2, the sample microstructures were characterized using multiple techniques. These included metallographic observation with a VHX-2000 microscope (KEYENCE, Osaka, Japan) and SEM performed on a Zeiss Sigma 300 instrument (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Jena, Germany). The SEM system was coupled with an energy dispersive spectroscopy detector for compositional analysis.

2.4. Performance Testing

Vickers microhardness testing was carried out on the samples using an HV-1000B hardness tester (SAACOO Instrument Co., Ltd., Chongqing, China). A standardized test protocol was adopted, which applied a load of 200 g and maintained it for a 15 s holding period. The reported microhardness value for each sample is the arithmetic mean of eight indentations, after discarding the highest and lowest values from a linear array of ten measurements spaced 0.9 mm apart. Tensile properties of the samples were evaluated using a universal testing machine (AG-X plus 100 KN, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) at a constant crosshead speed of 2 mm/min. Two replicates were tested for each tensile sample set to ensure data accuracy. The corresponding specimen geometry is detailed in Figure 1c. The test was conducted on the sample longitudinal section, which may introduce anisotropy as a limitation of this study. Electrochemical corrosion behavior was assessed at room temperature with an RST5000 workstation (Suzhou RST Electronics Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China). A 3.5 wt.% NaCl aqueous solution served as the electrolyte to simulate a marine environment. Corrosion resistance was quantitatively analyzed based on the obtained Tafel polarization curves. Electrochemical measurements were performed using a standard three-electrode system, comprising a platinum auxiliary electrode, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and the sample as the working electrode. Prior to testing, all sample surfaces were uniformly ground and polished to ensure accuracy. Subsequently, the open-circuit potential was stabilized for 10 min, followed by polarization scanning at a rate of 0.5 mV/s. Each sample was measured twice.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructural Analysis

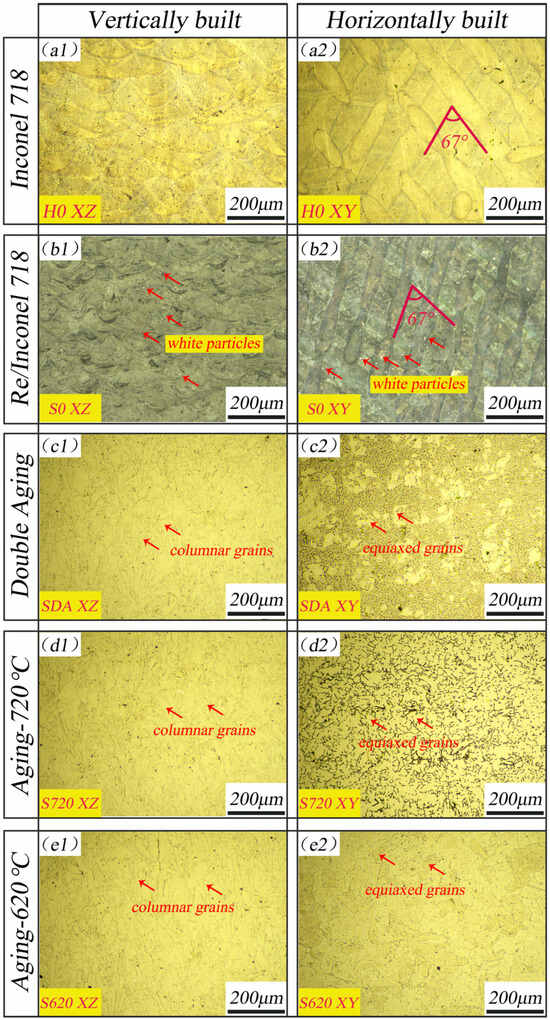

Figure 2(a1) shows the microstructural features of the longitudinal section of the H0 sample. The molten pool exhibits a continuously overlapping pattern resembling fish scales, with a width of approximately 200 μm. A multitude of columnar crystals exhibit continuous epitaxial growth oriented along the build direction. Their irregular morphology, characterized by a high aspect ratio, enables them to extend across multiple melt pool boundaries. Consequently, the grain boundaries appear indistinct. Additionally, the addition of Re did not markedly alter the microstructure of the Inconel 718 alloy (Figure 2(b1)). The uniformly distributed white particles within the structure are presumed to be added Re elements. The homogeneous distribution results from the combined action of the Marangoni effect in the melt pool and the agitation caused by laser-generated metal vapor, thereby promoting thorough particle mixing [21]. After heat treatment, the S0 sample underwent a microstructural transformation in which the characteristic fish-scale pattern of its melt pools was superseded by well-defined grain boundaries. The microstructure evolves into columnar grains aligned with the build direction (Figure 2(c1–e1)).

Figure 2.

Metallographic morphology of the H0-S620 samples: (a1–e1) longitudinal section; (a2–e2) transverse section.

The metallographic morphology of the H0 and S0 sample transverse sections exhibits typical intersecting columnar melt channels with an angle of 67° (Figure 2(a2,b2)). This characteristic geometry is a direct result of the laser scanning strategy. Furthermore, the grain boundaries are also obscured. After heat treatment, the columnar melt lines in the S0 sample have largely disappeared, and the grain boundaries have become clearly defined. Unlike the columnar grain morphology retained in the longitudinal section, the transverse section exhibits equiaxed grains with non-uniform sizes after heat treatment. It should be noted that these equiaxed grains are, in fact, the transverse sections of columnar crystals that have developed along the build direction, as shown in Figure 2(c2–e2).

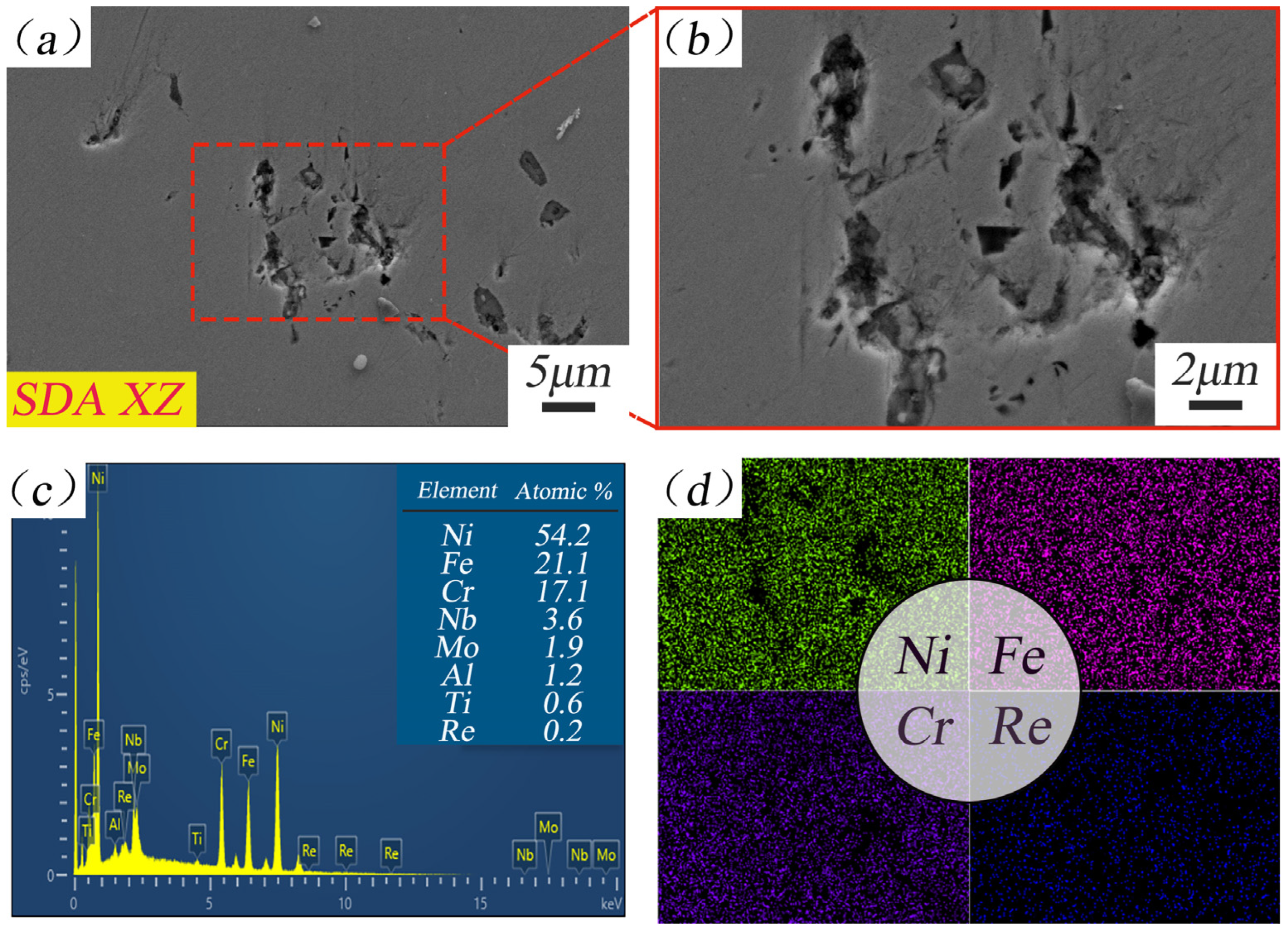

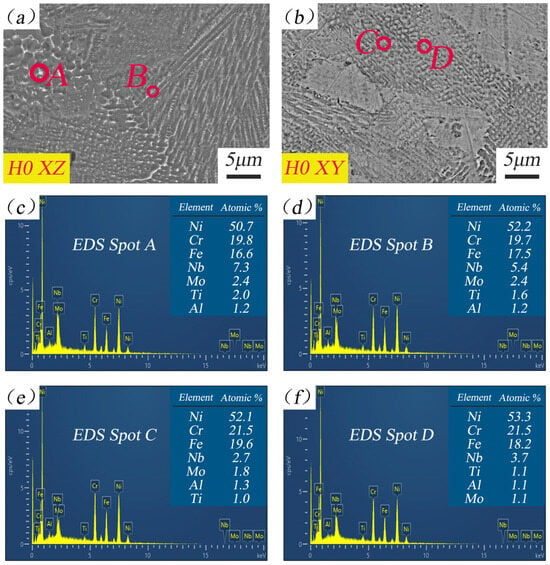

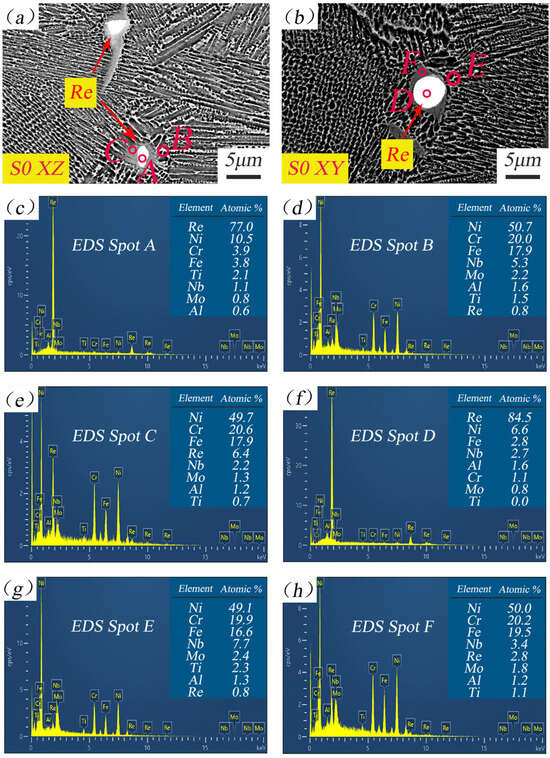

Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the microstructure of the H0 and S0 samples. During laser additive manufacturing, the metal powder undergoes rapid melting and solidification, leading to the formation of numerous columnar and cellular substructures that grow along the building direction in the longitudinal section of the deposited samples (Figure 3a and Figure 4a). Similarly, the transverse section exhibits an approximately equiaxed cellular crystal structure, with evident elemental segregation observed at its cell walls (Figure 3b and Figure 4b). Due to the epitaxial growth characteristics of LPBF, columnar grains grow preferentially along the building direction, thereby resulting in a cellular structure in the transverse section. The remelting of the underlying layer during laser scanning leads to coarser cellular and dendritic crystals at the melt pool bottom, whereas the higher cooling rate within the melt pool favors the formation of finer grains. Further microstructural analysis reveals finely dispersed white particles within the γ matrix (Figure 4a,b). EDS elemental analysis confirms these white particles to be the added Re element (Figure 4c,f). EDS analysis at points C and F indicates that the encapsulating material surrounding the Re particles constitutes a compositional gradient transition zone (Figure 4e,h). This zone is characterized by a nickel-based solid solution enriched in Re, which originates from the incomplete dissolution and subsequent diffusion of Re particles within the laser melt pool. Re is considered a reinforcing additive in nickel-based superalloys, with the added Re primarily enhancing alloy properties through mechanisms such as dispersion strengthening [22,23].

Figure 3.

Microstructure of the H0 sample: (a) longitudinal section; (b) transverse section; and (c–f) corresponding EDS spectra.

Figure 4.

Microstructure of the S0 sample: (a) longitudinal section; (b) transverse section; and (c–h) corresponding EDS spectra.

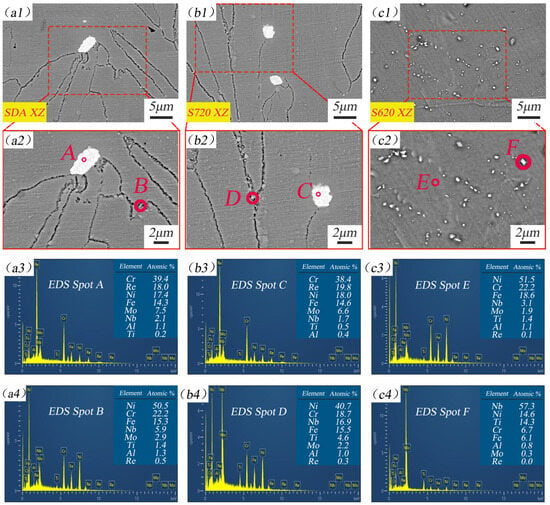

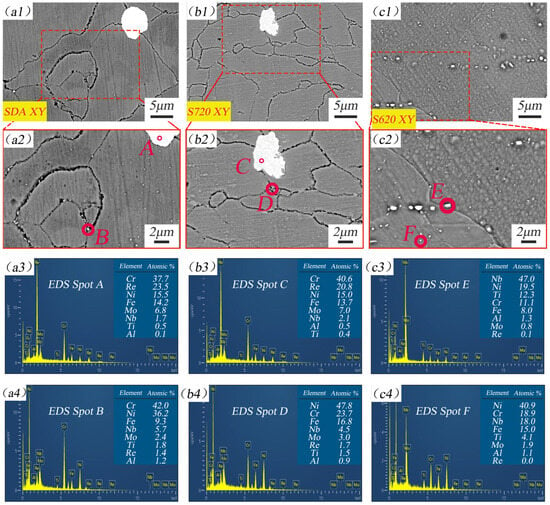

The cellular and columnar structures in the S0 sample were replaced by a grain boundary morphology exhibiting characteristic sawtooth features following heat treatment (Figure 5). The structural evolution indicates that the material undergoes significant recrystallization during heat treatment. Further observation reveals that numerous fine precipitation phases are distributed both within the grains and grain boundaries in the heat-treated samples, primarily in acicular, granular, and short rod-like morphologies. EDS analysis identifies that the predominant constituent elements of the precipitated phases are Ni, Cr, Fe, and Nb.

Figure 5.

Microstructure of the SDA, S720 and S620 samples in the longitudinal section: (a1,a2) SDA; (b1,b2) S720; (c1,c2) S620; and (a3–c3,a4–c4) corresponding EDS spectra.

Due to the relatively fine size of the precipitated phases in the H0-S620 samples, the hardness method is employed in this study to characterize the precipitation behavior of the γ′ and γ″ phases [24,25]. The average microhardness values are 552 HV0.2, 541 HV0.2, and 534 HV0.2 of the SDA, S720, and S620 samples in the longitudinal section, respectively. The differences in microhardness are strongly correlated with the types of precipitated phases present. The SDA sample, subjected to a double aging treatment at 720 °C × 8 h + 620 °C × 8 h, is tentatively identified as exhibiting the simultaneous precipitation of both the primary strengthening phase (γ″) and the secondary strengthening phase (γ′), which resulted in the highest average microhardness. The S720 sample, subjected to a single-stage aging treatment at 720 °C for 8 h, is tentatively identified as being predominantly strengthened by the γ″ phase, which corresponds to its second-highest average microhardness. The S620 sample, subjected to a single-stage aging treatment at 620 °C for 8 h, is tentatively identified as being primarily strengthened by the γ′ phase, which accounts for its lowest average microhardness.

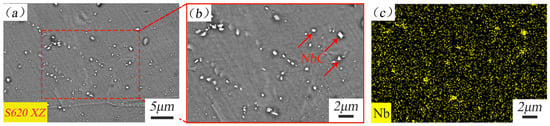

EDS point analysis at point F in Figure 5(c4) indicates a Nb content of 57.3% in the precipitate. Further analysis of the EDS surface scan maps of the S620 sample (Figure 6) reveals that certain particles are rich in Nb, tentatively identifying them as niobium carbides (NbC). This finding is consistent with reports in the existing literature [26]. NbC particles preferentially segregate at grain boundaries, exhibiting low solubility. These NbC particles frequently act as crack initiation sites, thereby reducing the material’s strength and hardness [27,28,29,30].

Figure 6.

(a,b) Longitudinal section of microstructures of the S620 sample; (c) corresponding EDS elemental mapping for niobium.

Figure 7 presents the SEM images of the transverse sections of the SDA, S720 and S620 samples. The transverse sectional analysis of the S620 sample revealed the presence of undissolved NbC particles within the grain interiors (Figure 7(c3)). It is noteworthy that no δ phase is observed in either the transverse section or longitudinal section of the heat-treated samples. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to the fact that the solution temperature of 1020 °C used in this study is significantly higher than the dissolution temperature of the δ phase (980 °C), making the δ phase unlikely to exist. Secondly, within the Re/Inconel 718 composite, the segregation of Re in the as-deposited state may further suppresses the segregation of Nb. Nb is the key element for forming the δ phase, which also inhibits the formation of the δ phase during heat treatment. Consequently, no δ phase is observed in any of the heat-treated samples.

Figure 7.

Microstructure of the SDA, S720 and S620 samples in the transverse section: (a1,a2) SDA; (b1,b2) S720; (c1,c2) S620; and (a3–c3,a4–c4) corresponding EDS spectra.

A comparison of Re content between the S0 (Figure 4c,f) and SDA (Figure 5(a3) and Figure 7(a3)) samples shows a significant decrease after heat treatment, from 77% (longitudinal section) and 84.5% (transverse section) to 18.0% (longitudinal section) and 23.5% (transverse section), respectively. This indicates that the Re content in the locally enriched regions decreases after heat treatment. This phenomenon can be attributed to an inferred mechanism whereby the heat treatment promoted Re diffusion, resulting in a sharp decrease in its content within the locally enriched regions.

3.2. Mechanical Performance and Electrochemical Behavior

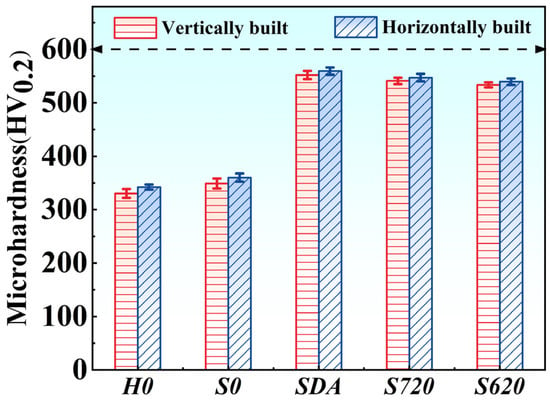

3.2.1. Microhardness

Figure 8 shows the microhardness values in the different cross-sections of the H0-S620 samples. The addition of Re led to a measurable increase in microhardness, from 330 HV0.2 (H0 sample) to 349 HV0.2 (S0 sample). This improvement is primarily due to the synergistic strengthening mechanisms provided by Re, including dispersion strengthening, solid solution strengthening, and dislocation strengthening [20].

Figure 8.

Vickers hardness of the H0-S620 samples.

After heat treatment, the SDA, S720, and S620 samples undergo recrystallization. The dissolution of the Laves phases and the concomitant precipitation of strengthening phases led to a significant increase in the microhardness. The significant increase in the microhardness after heat treatment is primarily attributed to precipitation strengthening of the γ″ and γ′ phases. Among these, the SDA sample exhibits the highest average microhardness (552 HV0.2), which is attributed to the simultaneous precipitation of substantial γ″ and γ′ phases during the double aging treatment at 720 °C + 620 °C. In contrast, the S720 sample exhibits a lower average microhardness (541 HV0.2) than the SDA sample, which is consistent with its predominant precipitation of the γ″ phase. The S620 sample, which is predominantly strengthened by the secondary γ′ phase, exhibits a corresponding further reduction in average microhardness (534 HV0.2) compared to the S720 sample. Notably, due to the rapid melting and solidification characteristics of LPBF, the alloy develops a columnar/cellular structure along the longitudinal section and a cellular structure on the transverse section. This microstructural anisotropy leads to significant variations in mechanical properties across different orientations.

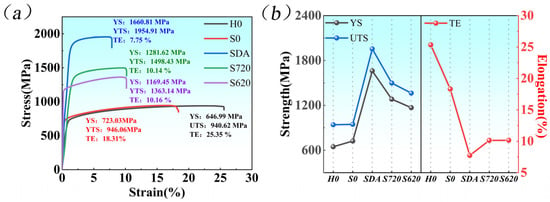

3.2.2. Tensile Properties

Comparing with the H0 sample, the Re addition to the S0 sample left its ultimate tensile strength essentially unchanged, while increasing the yield strength to 723.03 MPa (Figure 9). However, the elongation decreased from 25.35% (H0) to 18.31%. This strength-ductility trade-off is primarily attributed to the multiple strengthening effects induced by Re, such as dispersion and solid solution strengthening. These mechanisms, particularly through the pinning of dislocations by Re particles, effectively enhance strength but concurrently reduce ductility.

Figure 9.

(a) Tensile curves; (b) Strength and elongation variation curves.

The tensile strengths of the SDA-S620 samples were significantly improved after heat treatment. This is due to the combined effects of the dissolution of Laves phases, simultaneous precipitation of both γ″ and γ′ phases, and homogenization of microstructure. However, the abundant strengthening phases precipitated in the heat-treated samples increase the resistance to dislocation movement and hinder dislocation multiplication, thereby reducing the alloy’s plasticity. When the two-stage aging is 720 °C × 8 h (FC) + 620 °C × 8 h (AC), the SDA sample exhibited peak mechanical properties: a yield strength of 1660.81 MPa and an ultimate tensile strength of 1954.91 MPa. These values represent increases of 129.7% and 106.6%, respectively, compared to those of the S0 sample. Conversely, its elongation is reduced to 7.75%. When the aging temperature is 720 °C and 620 °C, the S720 and S620 samples exhibit lower ultimate tensile strengths than the SDA sample (1498.43 and 1363.14 MPa, respectively). This is attributed to the predominant precipitation of a single type of strengthening phase. However, their elongation recovered to 10.14% and 10.16%, respectively.

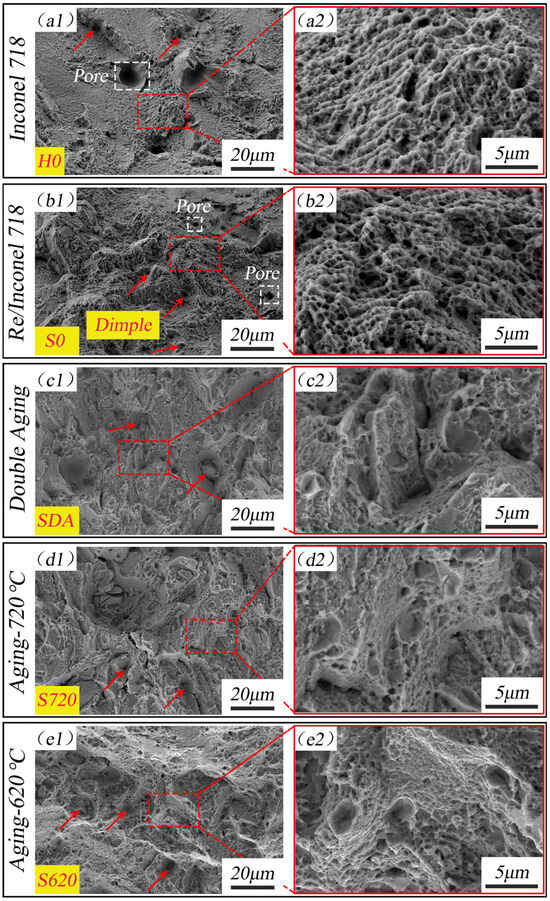

Figure 10 presents the fracture morphology of the H0-S620 samples. The fracture surfaces exhibit a typical ductile morphology, characterized by a high density of dimples. Large-sized pores were observed on the fracture surface of the H0 sample. The fracture surface of the S0 sample exhibits small pores and an absence of unmelted powder particles. After heat treatment, the porosity in the SDA-S620 samples is significantly reduced, with a notable decrease in pores. This demonstrates that the heat treatment effectively suppressed the formation and growth of gas pores in the LPBF-fabricated samples, enhancing the density of the samples and consequently improving the material’s strength.

Figure 10.

Fractured surfaces of the H0-S620 samples: (a1,a2) H0; (b1,b2) S0; (c1,c2) SDA; (d1,d2) S720; (e1,e2) S620.

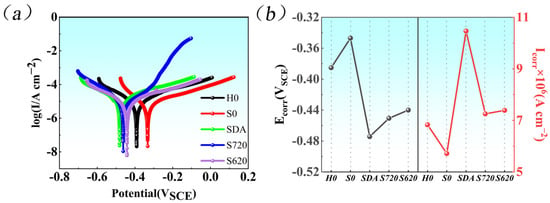

3.2.3. Corrosion Resistance

The polarization curves of all specimens exhibit a characteristic activation-passivation transition (Figure 11a). The anodic current density increases linearly with the potential, corresponding to the active dissolution region. A subsequent sharp rise in potential signifies the formation of a passive film on the alloy surface and the establishment of a stable passive state.

Figure 11.

(a) Polarization curves; (b) Ecorr and Icorr variation curves.

The Tafel extrapolation method was used to obtain the corrosion potential (Ecorr) and corrosion current density (Icorr) of the H0-S620 samples. A more positive Ecorr value indicates a lower tendency for corrosion, whereas a higher Icorr value corresponds to a faster corrosion rate. The addition of Re enhances the corrosion resistance of the S0 sample, demonstrated by a higher corrosion potential and a lower corrosion current density, which correspond to a reduced corrosion rate and susceptibility. It is mainly attributed to the segregation of Re at grain boundaries. This segregation contributes to microstructural refinement through mechanisms such as suppression of boundary diffusion, increased boundary density, and enhanced dislocation pinned effects, thereby decreasing the material’s susceptibility to corrosion.

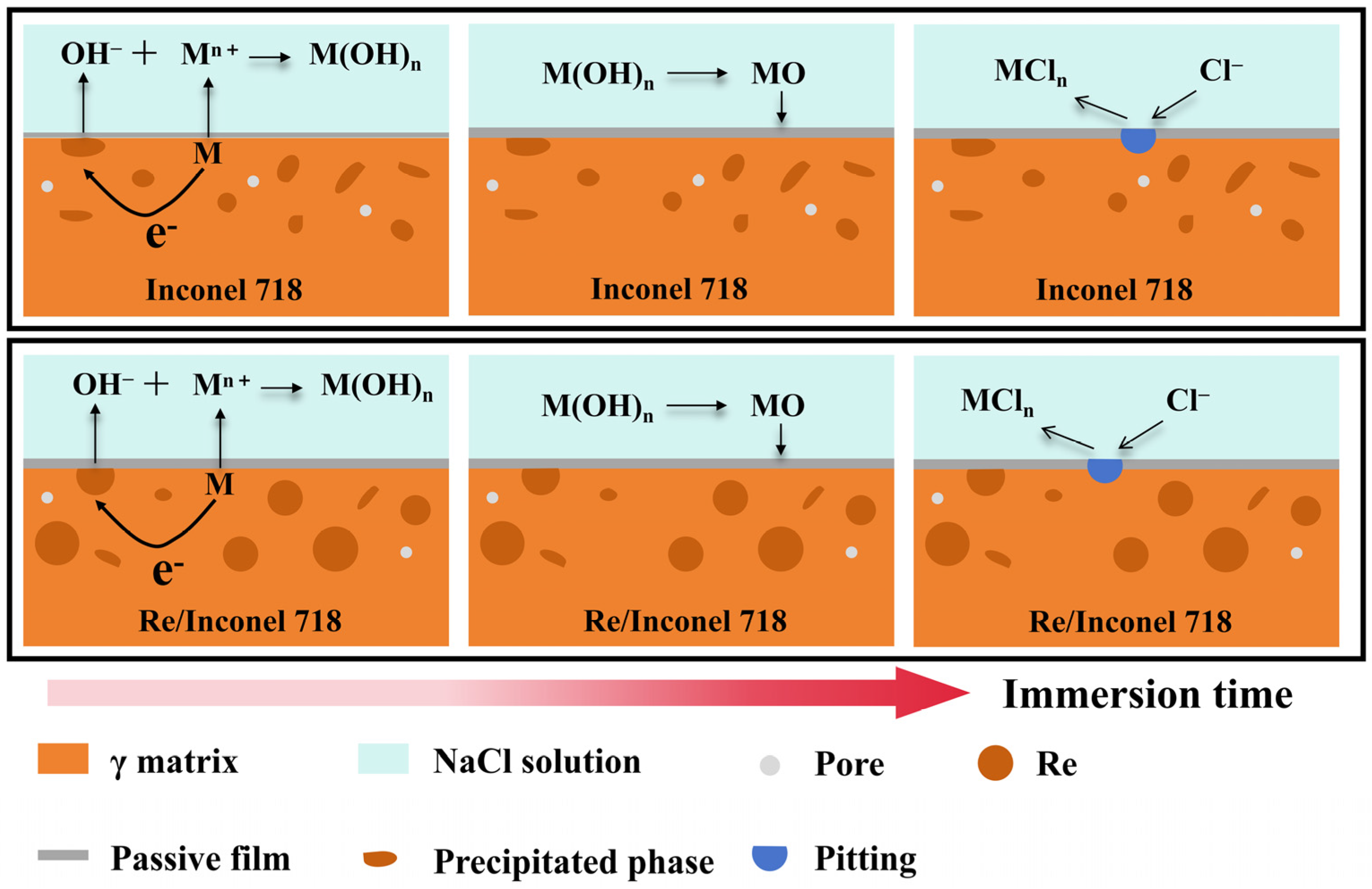

After heat treatment, the precipitation of numerous fine strengthening phases promotes the formation of micro-galvanic cells, which accelerate the corrosion process. This finding can be attributed to microscopic structural observations and previous research. Consequently, the heat-treated samples (SDA, S720, S620) exhibit a shift in the corrosion potential (Ecorr) towards a lower value and a significant increase in the corrosion current density (Icorr), indicating a marked degradation in corrosion resistance. Among them, the SDA sample after double aging at 720 °C + 620 °C exhibits the lowest corrosion resistance. The reason is the simultaneous precipitation of both abundant γ″ and γ′ phases after double aging at 720 °C + 620 °C. Although the sample’s mechanical properties are significantly enhanced, the abundant strengthening phases introduce numerous micro-galvanic cells during corrosion, which accelerate the corrosion rate and consequently degrade the corrosion resistance of the SDA sample.

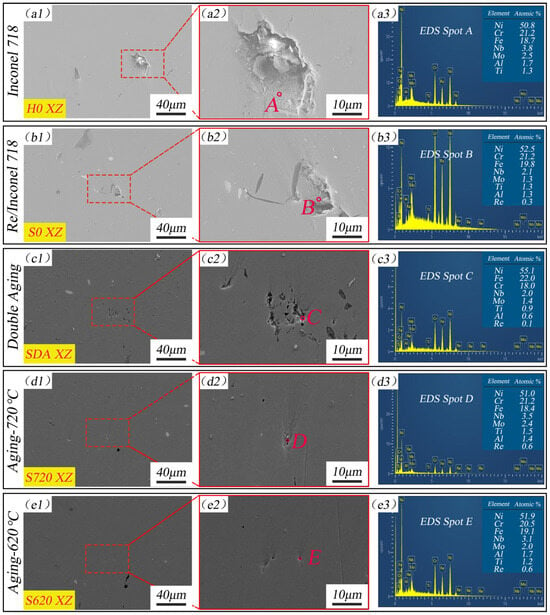

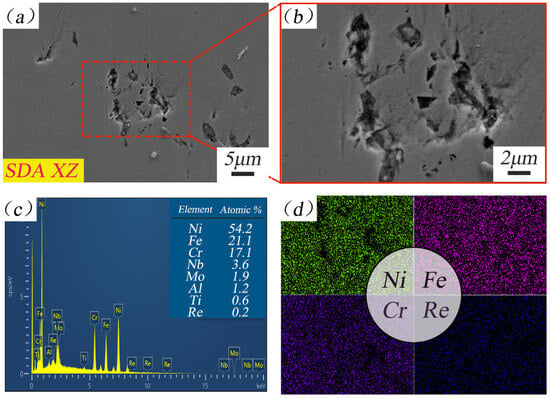

The corrosion morphology of the H0-S620 samples is shown in Figure 12. The H0 and S0 sample surfaces exhibit typical features of electrochemical corrosion, characterized by irregular pits 10–20 μm in width and the accumulation of corrosion products within them. EDS analysis indicates that the corrosion products consist primarily of Ni, Cr, and Fe (Figure 12(a3,b3)). Consistent with its improved corrosion resistance, the S0 sample developed notably smaller corrosion pits compared to the H0 sample. In contrast, the heat-treated samples (SDA, S720, S620) exhibit numerous irregular pitting corrosion craters with rough edges and internal corrosion products (Figure 12(c1–e1,c2–e2)). This indicates that the heat-treated samples (SDA, S720, S620) possess inferior corrosion resistance compared to the as-deposited sample (S0), consistent with Tafel curve analysis. Notably, higher concentrations of Re are not detected in the corrosion products by EDS analysis. To determine whether the Re participates in the corrosion process by forming a passivation film or corrosion products, an EDS surface scan analysis is performed on the SDA sample exhibiting the lowest corrosion resistance (Figure 13). Based on the results, it is inferred that Re does not participate in the corrosion reaction.

Figure 12.

Corrosion surface topography: (a1,a2) H0; (b1,b2) S0; (c1,c2) SDA; (d1,d2) S720; (e1,e2) S620; and (a3–e3) corresponding EDS spectra.

Figure 13.

(a,b) Corrosion surface topography of the SDA sample; (c) corresponding EDS spectra; (d) element distribution map.

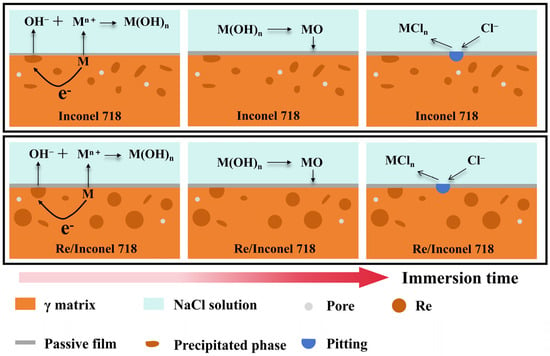

Electrochemical corrosion of the material occurs in a 3.5 wt.% NaCl aqueous solution (Figure 14). The representative electrode reactions involved are as follows:

Figure 14.

Schematic diagram of the corrosion.

Anode process:

Ni→Ni2+ + 2e−

Cr→Cr3+ + 3e−

Fe→Fe2+ + 2e−

2Fe2+ + 2H2O→2Fe3+ + 2OH− + H2

Cathode process:

2H2O + O2 + 4e−→4OH−

Overall process:

2Ni + 2H2O + O2 = 2Ni(OH)2

4Cr + 6H2O + 3O2 = 4Cr(OH)3

4Fe + 6H2O + 3O2 = 4Fe(OH)3

Due to their greater thermodynamic stability, oxides are preferentially formed over hydroxides. Consequently, hydroxides undergo transformation into oxides, followed by a dehydration process that yields a compact passive film:

Ni(OH)2→NiO + H2O

2Cr(OH)3→Cr2O3 + 3H2O

2Fe(OH)3→Fe2O3 + 3H2O

During corrosion, Cl− interact with metal cations such as Ni2+, Cr3+, and Fe3+ to form soluble chlorides, which compromise the integrity of the protective oxide layer. Following localized dissolution of this passive film, Cl− ingress into the underlying metal substrate, thereby initiating pitting corrosion:

NiO + 2Cl− + H2O→NiCl2 + 2OH−

Cr2O3 + 6Cl− + 3H2O→2CrCl3 + 6OH−

Fe2O3 + 6Cl− + 3H2O→2FeCl3 + 6OH−

4. Conclusions

This study examines the strengthening effects and mechanisms induced by the addition of Re to Inconel 718 alloy, and elucidates the microstructure-property relationships of Re/Inconel 718 composites subjected to various aging treatments. The conclusions are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- After heat treatment, the sample undergoes recrystallization, accompanied by the precipitation of numerous fine strengthening phases. Simultaneously, a small number of particles within the grains are tentatively identified as undissolved NbC. The absence of the δ phase in the microstructure of the samples is attributed to the high solution temperature and segregation of the Re element. Furthermore, heat treatment promotes Re diffusion from locally enriched zones, leading to a pronounced reduction in the local Re concentration.

- (2)

- The addition of Re improves the mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of the Inconel 718 alloy through synergistic strengthening mechanisms, including dispersion strengthening, solid solution strengthening, and dislocation strengthening. The aging treatment temperature of 720 °C × 8 h (FC × 2 h) + 620 °C × 8 h (AC) yields the optimum mechanical performance in the Re/Inconel 718 composites. The average microhardness (552 HV0.2), yield strength (1660.81 MPa), and ultimate tensile strength (1954.91 MPa) of the SDA sample increase simultaneously. The dissolution of Laves phases, simultaneous precipitation of both γ″ and γ′ phases and homogenization of the microstructure are responsible for the enhanced mechanical properties of the SDA sample.

- (3)

- The precipitation of abundant strengthening phases after heat treatment promotes the formation of numerous micro-galvanic cells, which accelerate the corrosion process and significantly degrade the material’s corrosion resistance. For the SDA sample, the double aging treatment at 720 °C × 8 h (FC × 2 h) + 620 °C × 8 h (AC) induces the simultaneous precipitation of γ″ and γ′ strengthening phases, leading to the highest micro-galvanic cell density. Consequently, the SDA sample exhibits the most rapid corrosion rate and the lowest corrosion resistance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B., M.W. and J.L.; methodology, J.L. and J.B.; validation, B.N., J.X. and Y.L.; formal analysis, J.L. and J.B.; investigation, B.N., J.X. and Y.L.; data curation, M.W., J.Z. and Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.W.; writing—review and editing, P.B. and J.L.; visualization, J.Z. and Z.W.; funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China for Young Scholars (52305400), Shanxi Natural Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (202403021223005), Fundamental mental Research Program of Shanxi Province (202303021222170), Taiyuan University of Science and Technology Scientific Research Initial Funding (20232007), Funding for Outstanding Doctoral Research in Jin (20242019), Process Development for 3D-Printed Parts Using High-Temperature Alloys and Corrosion-Resistant Alloys (2024132), and Special fund for Science and Technology Innovation Teams of Shanxi Province.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, S.; Guo, C.; Lin, X.; Zhao, H.; Yang, H.; Huang, W. Deformation behavior of selective laser-melted Inconel 718 superalloy. Mater. Charact. 2024, 216, 114180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, W.; Chen, Z.; Yan, K.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H. Hot deformation and microstructure evolution of selective laser melted 718 alloy pre-precipitated with δ phase. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 851, 143633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Li, J.; Gao, G.; Sun, J.; Yang, Z.; Yan, J.; Qian, G. Microstructural evolution and formation of fine grains during fatigue crack initiation process of laser powder bed fusion Ni-based superalloy. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 85, 104151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Ullah, R.; Lu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Insight into elongation and strength enhancement of heat-treated LPBF Ni-based superalloy 718 using in-situ SEM-EBSD. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 914, 147163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, P.; Huo, P.; Wang, J.; Yang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Du, W.; Qu, H. Microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of Inconel 718 alloy manufactured by selective laser melting after solution and double aging treatments. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 911, 164988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Zhao, Z.; Bai, P.; Du, W.; Zhang, L.; Qu, H. Effect of Heat Treatment on the Microstructure and Properties of Inconel 718 Alloy Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 31, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.G.; Li, B.; Wang, M.L.; Guo, S.Q.; Miao, G.L.; Shi, D.Q.; Fan, Y.S. Correlation between microstructures and mechanical properties of a SLM Ni-based superalloy after different post processes. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 32, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhuo, L.; Xie, Y.; Huang, S.; Wang, T.; Yan, T.; Gong, X.; Wang, Y. Comparative study on microstructure, mechanical and high temperature oxidation resistant behaviors of SLM IN718 superalloy before and after heat treatment. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, W.; Chen, Z.; Yan, K.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H. Anisotropy of flow behavior and microstructure evolution of selective laser melted 718 alloy during high temperature deformation. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 107674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones-Montemayor, M.J.; Guzman-Nogales, R.; Majari, P.; Estrada-Diaz, J.A.; Elias-Zuniga, A.; Olvera-Trejo, D.; Martinez-Romero, O.; Perales-Martinez, I.A. Enhanced Mechanical Performance of SLM-Printed Inconel 718 Lattice Structures Through Heat Treatments. Metals 2025, 15, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, Z.; Bai, P.; Qu, H.; Liu, B.; Li, L.; Wu, L.; Guan, R.; Liu, H.; Guo, Z. Microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of IN718 alloy fabricated by selective laser melting following different heat treatments. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 772, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Antonov, S.; Lu, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Feng, Q. Unveiling the Re effect on long-term coarsening behaviors of γ′ precipitates in Ni-based single crystal superalloys. Acta Mater. 2022, 233, 117979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.D.; Li, W. Inhibiting effect of Ni/Re diffusion barrier on the interdiffusion between Ni-based coating and titanium alloys. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 106192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Tan, Q.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Gorbatov, O.I.; Peng, P. First-principles study of Re-W interactions and their effects on the mechanical properties of γ/γ′ interface in Ni-based single-crystal alloys. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 36, 106662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Mao, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Han, X. Microstructural and compositional design of Ni-based single crystalline superalloysd—A review. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 743, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankiewicz, M.; Karoluk, M.; Dziedzic, R.; Gruber, K.; Stopyra, W. Static and Fatigue Properties of Rhenium-Alloyed Inconel 718 Produced by Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing. Materials 2025, 18, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohrevand, M.; Mokhtare, M.; Momeni, A.; Sadeghpour, S.; Somani, M. Effect of Re addition on microstructure, properties, and performance of AlMo0.5NbTa0.5TiZr refractory high entropy alloy. Intermetallics 2024, 168, 108257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrowicz, K.; Pakiela, Z.; Kaminski, J.; Plocinska, M.; Kurzynowski, T.; Chlebus, E. The Effect of Rhenium Addition on Microstructure and Corrosion Resistance of Inconel 718 Processed by Selective Laser Melting. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2018, 49, 6479–6489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Huang, W.; Yang, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, X. Microstructural evolution and corrosion behaviors of Inconel 718 alloy produced by selective laser melting following different heat treatments. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 30, 100875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, P.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Bai, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Niu, B.; Xing, J.; Liao, Y. Effects of heat treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of Re/Inconel 718 composites fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2026, 40, 1466–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Gu, D.; Ma, C.; Xi, L.; Zhang, H. Microstructure characteristics and its formation mechanism of selective laser melting SiC reinforced Al-based composites. Vacuum 2019, 160, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckl, A.; Neumeier, S.; Goeken, M.; Singer, R.F. The effect of Re and Ru on γ/γ′ microstructure, γ-solid solution strengthening and creep strength in nickel-base superalloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 3435–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, E.; Miller, M.K.; Affeldt, E.; Glatzel, U. Quantitative experimental determination of the solid solution hardening potential of rhenium, tungsten and molybdenum in single-crystal nickel-based superalloys. Acta Mater. 2015, 87, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wang, Z. Isothermal Solid-State Transformations of Inconel 718 Alloy Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2021, 23, 2000982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Yang, J.; Yang, H.; Jing, G.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, X. Heat treatment of Inconel 718 produced by selective laser melting: Microstructure and mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 750, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Lin, X.; Yang, H.; Huang, W. The formation and dissolution mechanisms of Laves phase in Inconel 718 fabricated by selective laser melting compared to directed energy deposition and cast. Compos. Part B-Eng. 2022, 239, 109994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Sahoo, D.; Amirthalingam, M.; Karagadde, S.; Mishra, S.K. Dissolution of the Laves phase and δ-precipitate formation mechanism in additively manufactured Inconel 718 during post printing heat treatments. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 81, 104021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Peng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Gao, Z. Effects of Heat Treatment and Carbon Element Invasion on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Inconel 718 Alloys Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 33, 8015–8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Guan, K.; Yang, Z.; Hu, Z.; Qian, Z.; Wang, H.; Ma, Z. The effect of subsequent heat treatment on the evolution behavior of second phase particles and mechanical properties of the Inconel 718 superalloy manufactured by selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 794, 139931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Pan, Y.; Hu, L.; Du, D.; Wang, S.; Wen, J.-F.; Song, M. Microstructure instability of additively manufactured alloy 718 fabricated by laser powder bed fusion during thermal exposure at 600–1000 °C. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.