Effect of Nb on the Microstructure and High-Cycle Fatigue Properties of the Coarse-Grained Heat-Affected Zone in Low-Carbon Microalloyed Steel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

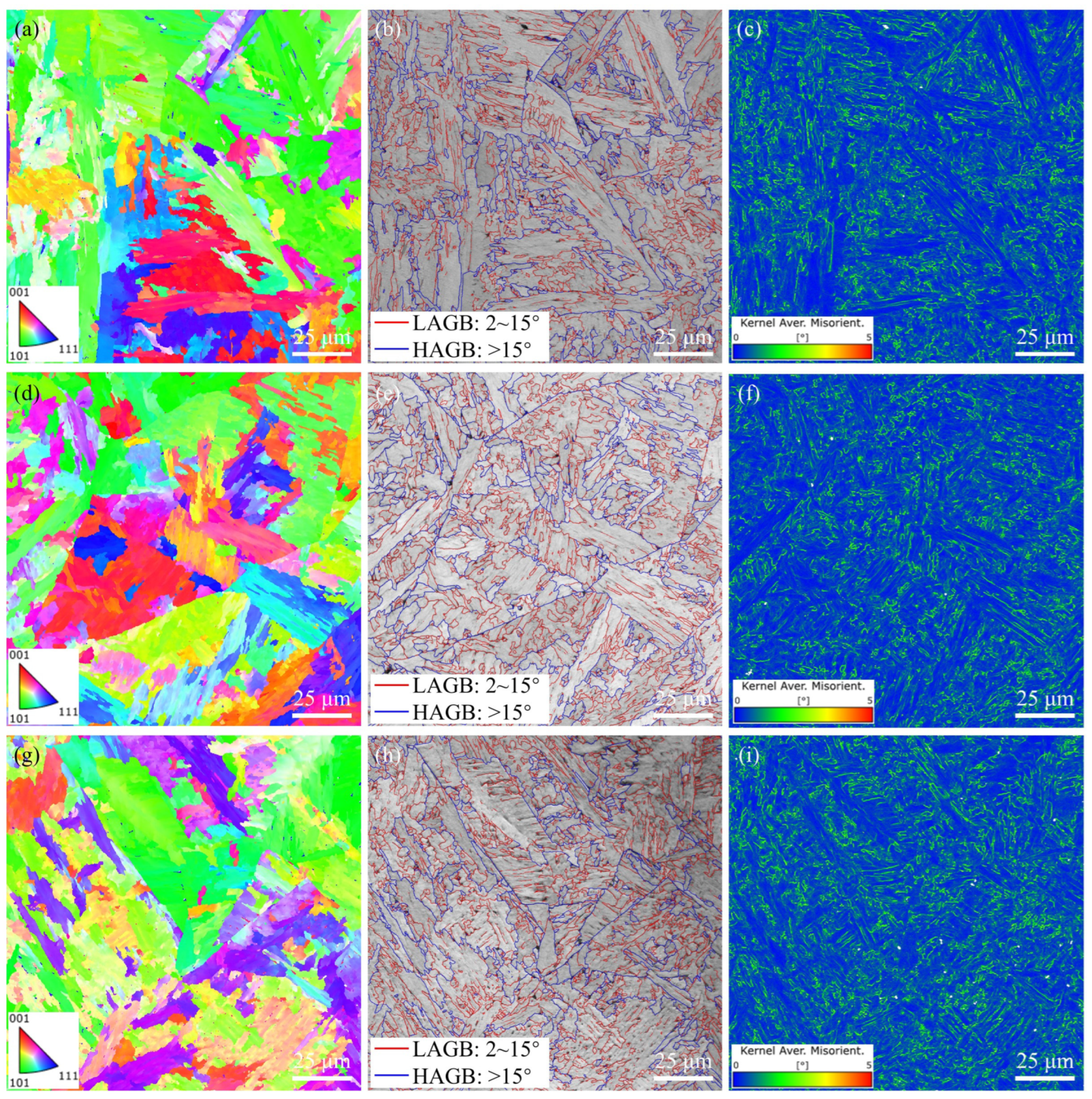

3.1. Microstructures

3.2. Mechanical Properties

3.3. Fatigue Fracture Characteristics

4. Discussion

4.1. Microstructure Evolutionary

4.2. Fatigue Damage Mechanism

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- As the Nb content increased, the area fractions of the GBF and M/A constituent increased in the CGHAZ, while those of the LBF and DP decreased. Concurrent with these alterations, the densities of both LAGBs and HAGBs increased, the MED from EBSD data decreased, and the PAGs refined.

- (2)

- The fatigue strength of the simulated CGHAZs exhibited an upward trend, increasing from 212.6 MPa to 231.9 MPa as the Nb content was augmented from 0.018 wt.% to 0.055 wt.%. In addition, the yield strength, tensile strength, and hardness of the CGHAZs exhibited a continuous increasing trend with increasing Nb content.

- (3)

- The fatigue crack initiation lifetime of the CGHAZs accounted for over 97% of the total failure lifetimes, and the fatigue crack initiation was identified as the dominant factor governing fatigue damage. The increase in Nb content promoted a synergistic effect, evidenced by an elevated density of LAGBs and a decreased MED, which collectively enhanced the resistance to fatigue crack initiation.

- (4)

- HAGBs can deflect and arrest the fatigue secondary microcracks effectively. The enhanced density of HAGBs, concomitant with elevated Nb contents, has been demonstrated to directly augment the inhibitory effect of fatigue crack propagation.

- (5)

- For the low-carbon microalloyed steels, the increase in Nb content resulted in enhanced fatigue crack initiation and propagation lifetimes, thereby increasing the high-cycle fatigue strength of the CGHAZ.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CGHAZ | Coarse-grained heat-affected zone |

| LAGBs | Low-angle grain boundaries |

| HAGBs | High-angle grain boundaries |

| MED | Mean equivalent diameter |

| PAGs | Prior austenite grains |

| TMCP | Thermomechanical control process |

| OM | Optical microscope |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| EBSD | Electron backscatter diffraction |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscope |

| EDS | Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| LBF | Lath bainitic ferrite |

| GBF | Granular bainitic ferrite |

| DPF | Degenerated pearlite ferrite |

| SAED | Selected area electron diffraction |

| BCC | Body-centered cubic |

| FCC | Face-centered cubic |

| IPFs | Inverse pole figures |

| MTAs | Misorientation angles |

| IQ | Image quality |

| KAM | Kernel average misorientation |

References

- Li, Y.L.; Huang, Y.J.; Sheng, J. Policy-driven energy transition: China’s low-carbon journey and global implications. Energy Econ. 2025, 150, 108888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.H.; Li, M.D.; Han, C.F.; Meng, L.P.; Shao, Z.G. From input to output: Unraveling the Spatio–temporal pattern and driving factors of the coupling coordination between wind power efficiency and installed capacity in China. Appl. Energy 2025, 396, 126320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.M.; Lv, K.F.; Han, C.F.; Liu, P.H. A tripartite stochastic evolutionary game for trading strategies under renewable portfolio standards in China’s electric power industry. Renew. Energy 2025, 240, 122193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.R.; Gong, B.M.; Liu, S.; Deng, C.Y.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, W.T. Low-cycle fatigue properties and fracture location transition mechanism of dissimilar steel welded joints in towers of wind turbines. Int. J. Fatigue 2025, 190, 108672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Qiao, G.Y.; Wang, J.S.; Zhang, S.Y.; Xiao, F.R. Research on the fatigue properties of sub-heat-affected zones in X80 pipe. Fatigue Fract. Eng. M. 2020, 43, 2915–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.; Wang, X.R. A review of fatigue test data on weld toe grinding and weld profiling. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 145, 106073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.S.; Chen, N.N.; Cai, Y.; Guo, W.; Wang, M. Effect of crystallographic features on low-temperature fatigue ductile-to-brittle transition for simulated coarse-grained heat-affected zone of bainite steel weld. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 170, 107523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, B.; Komenda, J.; Rohrer, G.S.; Beladi, H. Heat affected zone microstructure and their influence on toughness in two microalloyed HSLA steel. Acta Mater. 2015, 97, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; Furuya, Y.; Kasuya, T.; Enoki, M. Microstructurally small fatigue crack initiation behavior of fine and coarse grain simulated heat-affected zone microstructures in low carbon steel. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 832, 142363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.H.; Feng, Q.S.; Wang, B.F.; Zheng, W.Q.; Yu, Y.J. High-Cycle Fatigue Performance of the Heat-Affected Zone of Q370qENH Weathering Bridge Steel. J. Mater. Civil. Eng. 2024, 36, 04024018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Wang, X.L.; Xie, Z.J.; Shang, C.J.; Liu, Z.Z. Crystallographic study on microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of coarse grained heat affected zone of a 500 MPa grade wind power steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 3921–3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Guo, X.; Sun, X.J.; Liu, G.Y.; Xie, Z.J.; Wang, X.L.; Shang, C.J. Effect of heat input on microstructural characteristics and fatigue property of heat-affected zone in a FH690 heavy-gauge marine steel. Int. J. Fatigue 2025, 196, 108898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Gao, H.L.; Zhuang, C.J.; Ji, L.K. Effect of Welding Heat Input on Microstructure and Properties of Coarse Grain Zones in X100 Pipeline Steel. J. Weld. 2010, 31, 29–32+114. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Qi, K.; Liu, Z.; Yang, L.; Xue, Z.; Li, T.; Zhang, X.; Li, R. Microstructure and mechanical properties of submerged arc welded medium-thickness Q690qE high-strength steel plate joints. High Temp. Mater. Process. 2024, 43, 20240033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.M.; Guo, X.; Han, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Gan, H.; Song, C. Influence mechanism of heat input on low-temperature impact toughness of the coarse grain heat affected zone of ultra-strength steel. Trans. China Weld. Inst. 2024, 45, 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, R.; Yang, Z.; Chan, Z.; Lei, W. The determination of the weakest zone and the effects of the weakest zone on the impact toughness of the 12Cr2Mo1R welded joint. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 50, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Huang, C.X.; Liu, Y.J.; Wang, Q.Y. Fatigue damage evaluation of low-alloy steel welded joints in fusion zone and heat affected zone based on frequency response changes in gigacycle fatigue. Int. J. Fatigue 2014, 61, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.F.; Yang, D.D.; Ren, Z.H.; Zhao, R.C.; Huang, J.H. The proportion between the gear bending fatigue crack initiation and total life: A quantitative study. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 175, 109611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Chen, N.; Cai, Y.; Guo, W.; Wang, M. Effect of Microstructure on Impact Toughness and Fatigue Performance in Coarse-Grained Heat-Affected Zone of Bainitic Steel Welds. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2023, 32, 3678–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 24176-2009; Metallic Materials—Fatigue Testing—Statistical Planning and Analysis of Data. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Zhao, L.Y.; Wang, Q.F.; Shi, G.H.; Yang, X.Y.; Qiao, M.L.; Wu, J.P.; Zhang, F.C. In-depth understanding of the relationship between dislocation substructure and tensile properties in a low carbon microalloying steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 854, 143681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.M.; Liu, K.; Chen, H.; Xiao, X.P.; Wang, Q.F.; Zhang, F.C. Effect of increased N content on microstructure and tensile properties of low-C V-microalloyed steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 651, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.L.; Wang, Q.M.; Zhao, L.Y.; Hu, B.; Wang, Q.F. Competitive growth of martensite/austenite constituent and degenerated pearlite and the impact toughness in the coarse-grained heat-affected zone of a low carbon microalloying steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 789–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Kumar, P. Investigation on microstructural and mechanical integrity of GTAW dissimilar welded joint of IN 718/ASS 304L using Ni-based filler IN 625 using EBSD and DHD techniques. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2024, 209, 105213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.L.; Guo, W.; Zhang, Y.X.; Xia, M.S.; Jia, Q.; Chi, J.X.; Shi, J.X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.Q. Local microstructure and mechanical characteristics of HAZ and tensile behavior of laser welded QP980 joints. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 854, 143862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basquin, O.H. The exponential law of endurance tests. Am. Soc. Test. Mater. Proc. 1910, 10, 625–630. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, Y.; Takagi, T.; Wada, K.; Matsunaga, H. Essential structure of S-N curve: Prediction of fatigue life and fatigue limit of defective materials and nature of scatter. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 146, 106138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, W.C. Fatigue striation spacing analysis. Mater. Charact. 1994, 33, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.M.G.P.; de Matos, P.F.P.; de Castro, P.M.S.T. Fatigue striation spacing and equivalent initial flaw size in Al 2024-T3 riveted specimens. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mec. 2005, 43, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.L.; Jia, X.; Ma, Y.X.; Wang, P.; Zhu, F.X.; Yang, H.F.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.G. Effect of Nb on microstructure and mechanical properties between base metal and high heat input coarse-grain HAZ in a Ti-deoxidized low carbon high strength steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 2399–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X.; Li, X.C.; Wang, X.L.; Shang, C.J.; Zhang, Y.Q. Studies on the effect of Nb on microstructure refinement and impact toughness improvement in coarse-grained heat-affected zone of X80 pipeline steels. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 42, 111605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.M.; He, J.L.; Shi, G.H.; Wang, Q.F. Effect of Welding Heat Input on Microstructure and Impact Toughness of the Simulated CGHAZ in Q500qE Steel. Acta Met. Sin. 2022, 58, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar]

- Daigne, J.; Guttmann, M.; Naylor, J.P. The influence of lath boundaries and carbide distribution on the yield strength of 0.4% C tempered martensitic steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1982, 56, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Wang, Q.; Dou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xu, X.; Wang, Q. Comparison of Strengthening Mechanism of the Nb, V, and Nb-V Micro-Alloyed High-Strength Bolt Steels Investigated by Microstructural Evolution and Strength Modeling. Metals 2024, 14, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Jo, H.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, C.; Moon, J.; Chung, J.H.; Lee, B.H.; Lee, C.H. Distinct roles of Nb, Ti, and V microalloying elements on the fire resistance of low-Mo steels. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 37, 2144–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.C.; Li, J.W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.D.; Bai, Y.; He, T.; Yuan, G. Microstructural refinement by the formation of acicular ferrite on Ti–Mg oxide inclusion in low-carbon steel. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 824, 141795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.H.; Zhao, H.L.; Zhang, S.M.; Wang, Q.F.; Zhang, F.C. Microstructural characteristics and impact fracture behaviors of low-carbon vanadium-microalloyed steel with different nitrogen contents. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 769, 138501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zener, C. Theory of Growth of Spherical Precipitates from Solid Solution. J. Appl. Phys. 1949, 20, 950–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolovich, S.D.; Armstrong, R.W. Plastic strain localization in metals: Origins and consequences. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 59, 1–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, J.C.; Laird, C. Crack initiation mechanisms in copper polycrystals cycled under constant strain amplitudes and in step tests. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1983, 60, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Mura, T. A dislocation model for fatigue crack initiation. J. Appl. Mech. 1981, 48, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangid, M.D.; Maier, H.J.; Sehitoglu, H. The role of grain boundaries on fatigue crack initiation–An energy approach. Int. J. Plast. 2011, 27, 801–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essmann, U.; Gösele, U.; Mughrabi, H. A model of extrusions and intrusions in fatigued metals I. Point-defect production and the growth of extrusions. Philos. Mag. A 1981, 44, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Inomata, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Tsurekawa, S.; Watanabe, T. Effects of grain boundary- and triple junction-character on intergranular fatigue crack nucleation in polycrystalline aluminum. J. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 3792–3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Zhang, P.; Li, L.L.; Zhang, Z.F. Fatigue cracking at twin boundaries: Effects of crystallographic orientation and stacking fault energ. Acta Mater. 2012, 60, 3113–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Li, L.L.; Zhang, Z.J.; Zhang, Z.F. Effects of grain size and Schmid factor difference on fatigue cracking at twin boundaries in CrCoNi medium-entropy alloy. Acta Metall. Sin. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.L.; Zhang, Z.J.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Z.F. A review on the fatigue cracking of twin boundaries: Crystallographic orientation and stacking fault energy. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 131, 101011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cr | Nb | V | Ti | Alt | Fe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 Nb | 0.07 | 0.23 | 1.38 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.24 | 0.018 | 0.025 | 0.014 | 0.027 | Balance |

| 38 Nb | 0.07 | 0.23 | 1.42 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.24 | 0.038 | 0.025 | 0.015 | 0.031 | Balance |

| 55 Nb | 0.07 | 0.23 | 1.40 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.24 | 0.055 | 0.025 | 0.014 | 0.032 | Balance |

| LAGB | HAGB | MEDMTA ≥ 15° (μm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number Fraction | LLAGB (mm) | (1/μm) | Number Fraction | LHAGB (mm) | (1/μm) | ||

| 18 Nb | 59.2% | 8.69 | 2.32 × 10−4 | 40.8% | 5.99 | 1.60 × 10−4 | 7.73 |

| 38 Nb | 62.1% | 10.00 | 2.67 × 10−4 | 37.9% | 6.21 | 1.66 × 10−4 | 7.25 |

| 55 Nb | 66.9% | 11.20 | 2.99 × 10−4 | 33.1% | 6.54 | 1.74 × 10−4 | 6.73 |

| Specimen | Yield Strength (MPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Uniform Elongation (%) | Hardness (HV0.5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 Nb | 469 ± 4 | 600 ± 7 | 10.9 ± 0.1 | 198.8 ± 6.6 |

| 38 Nb | 490 ± 1 | 617 ± 2 | 10.0 ± 0.2 | 203.3 ± 5.6 |

| 55 Nb | 503 ± 4 | 637 ± 8 | 9.5 ± 0.2 | 211.7 ± 3.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, G.; He, J.; Zhu, L.; Kong, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Z. Effect of Nb on the Microstructure and High-Cycle Fatigue Properties of the Coarse-Grained Heat-Affected Zone in Low-Carbon Microalloyed Steel. Metals 2026, 16, 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020175

Zhang G, He J, Zhu L, Kong Y, Wang Q, Liu Z. Effect of Nb on the Microstructure and High-Cycle Fatigue Properties of the Coarse-Grained Heat-Affected Zone in Low-Carbon Microalloyed Steel. Metals. 2026; 16(2):175. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020175

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Guodong, Jiangli He, Liyuan Zhu, Yisen Kong, Qingfeng Wang, and Zhongzhu Liu. 2026. "Effect of Nb on the Microstructure and High-Cycle Fatigue Properties of the Coarse-Grained Heat-Affected Zone in Low-Carbon Microalloyed Steel" Metals 16, no. 2: 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020175

APA StyleZhang, G., He, J., Zhu, L., Kong, Y., Wang, Q., & Liu, Z. (2026). Effect of Nb on the Microstructure and High-Cycle Fatigue Properties of the Coarse-Grained Heat-Affected Zone in Low-Carbon Microalloyed Steel. Metals, 16(2), 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16020175